User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Spiral Plaque on the Left Ankle

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

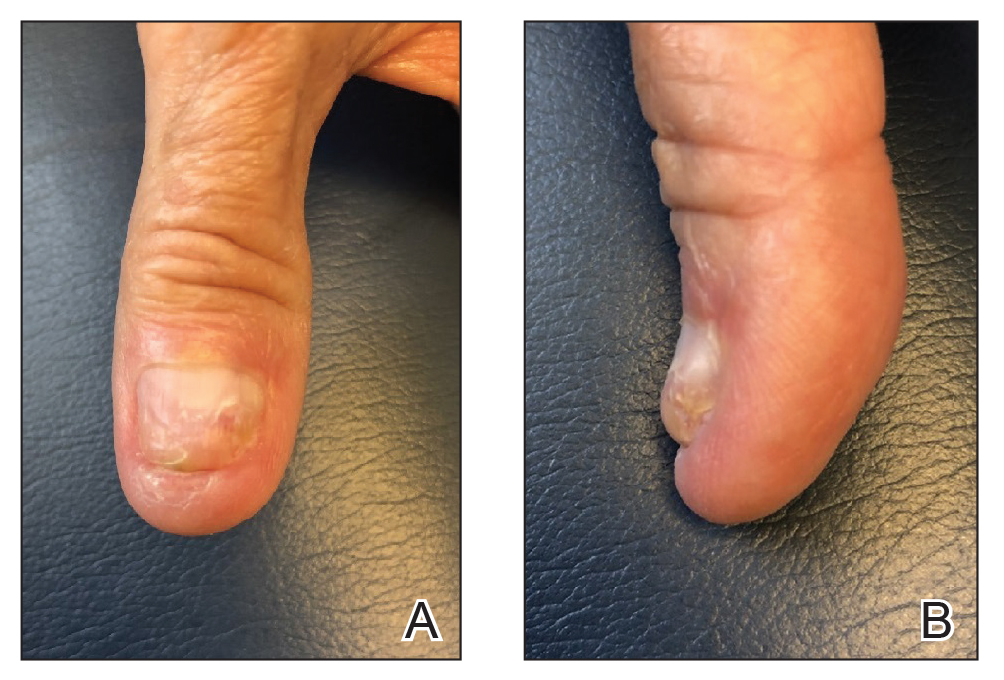

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

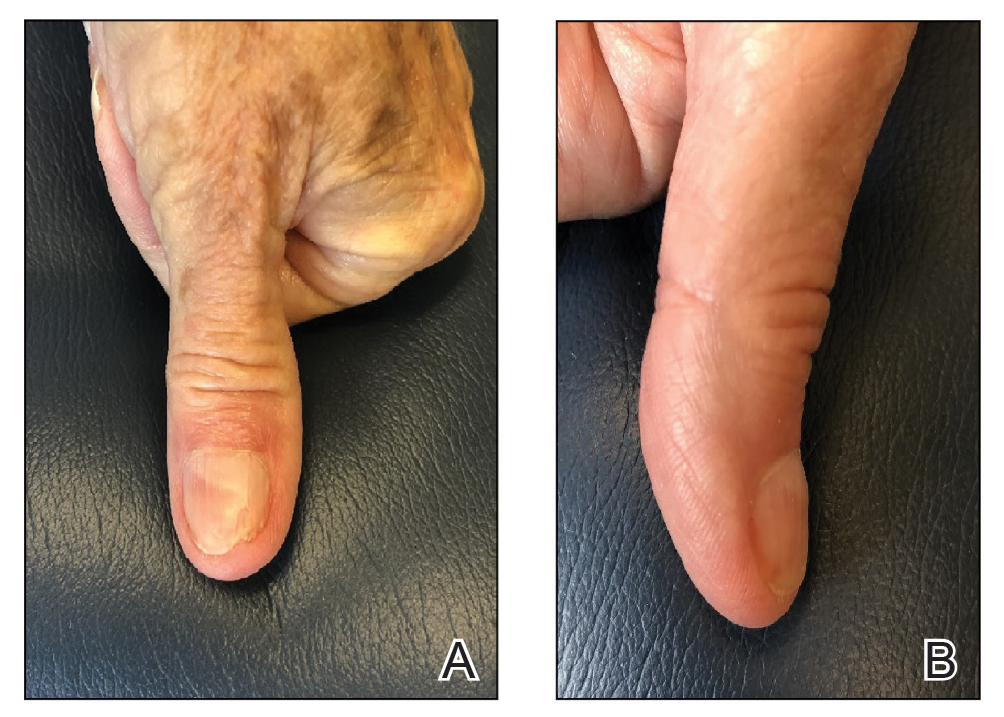

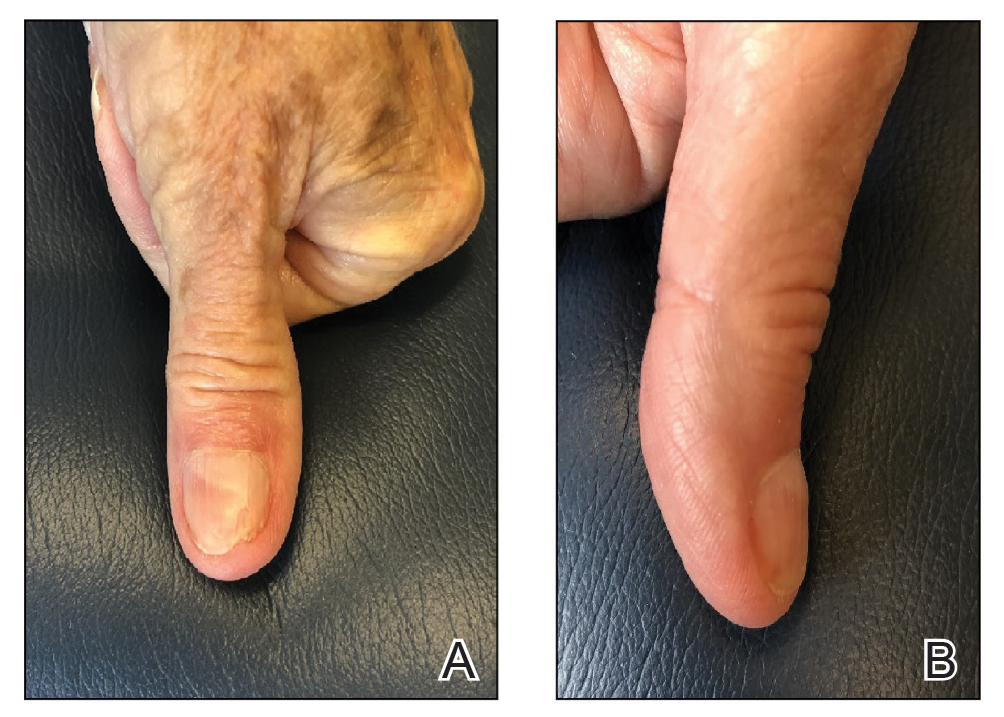

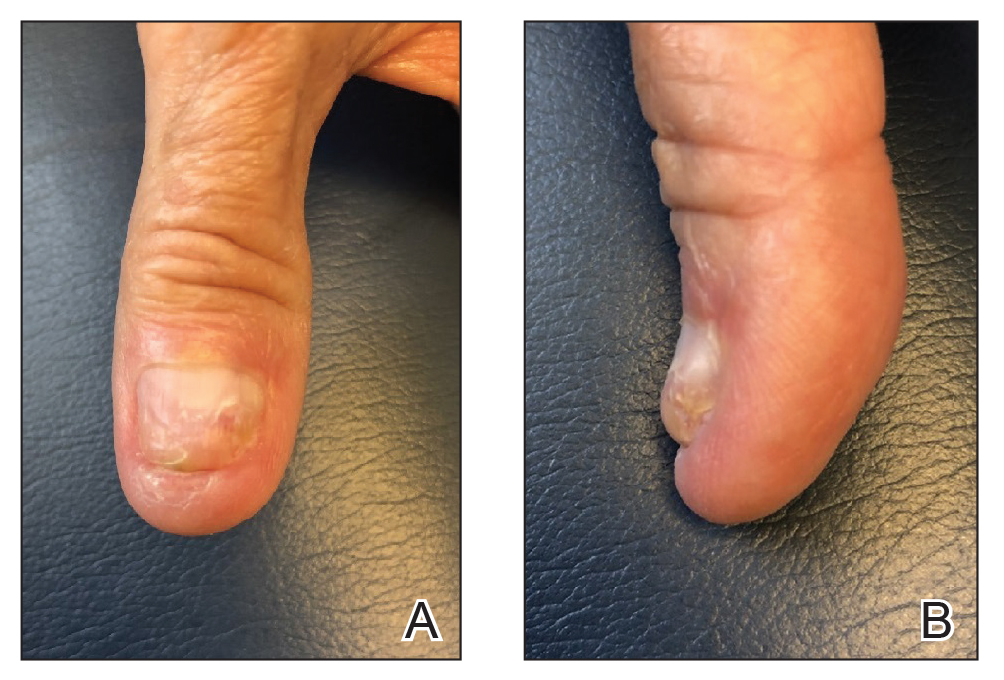

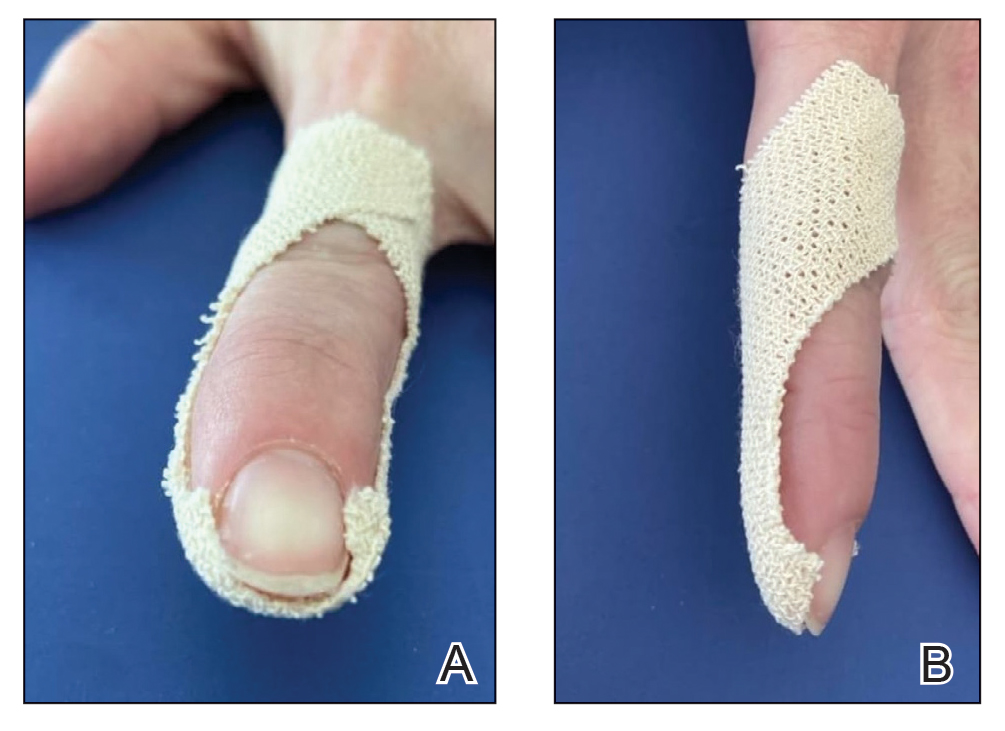

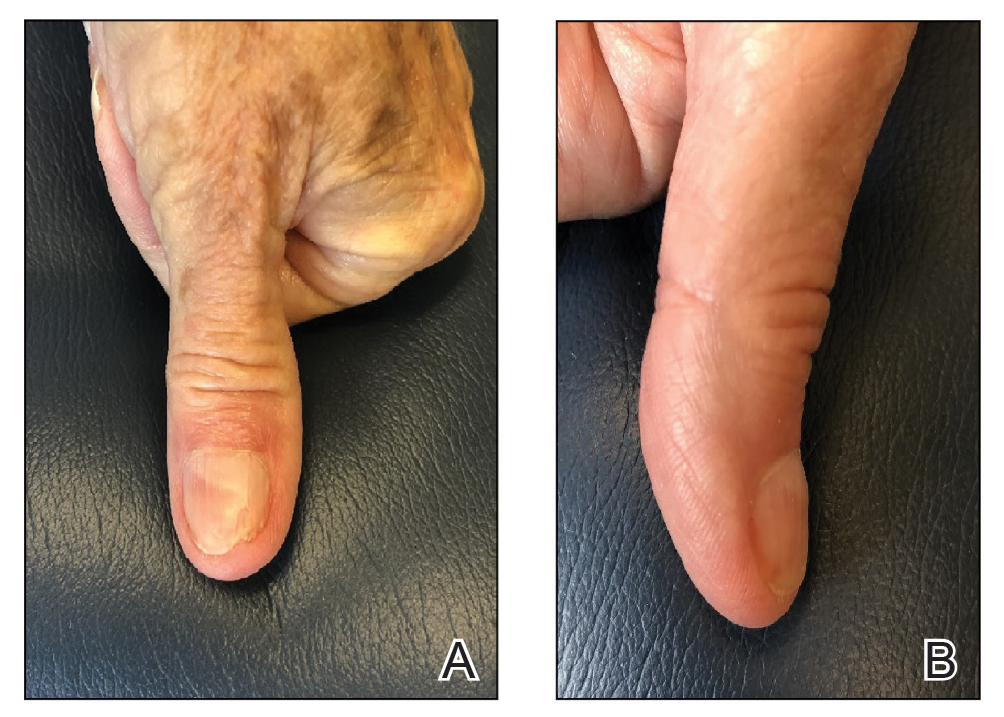

A 60-year-old man presented with a whorl-like plaque on the left ankle that he had noticed while undergoing treatment with narrowband UVB every other week and nitrogen mustard gel daily for stage IB cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides type. He denied pain, pruritus, and any other associated symptoms at the site. He denied recent illness, new medications, or changes in diet. His medical history included multiple sclerosis, vascular disease, and stroke. Physical examination revealed an 8×6-cm, welldemarcated, slightly scaly, erythematous plaque with a spiral appearance and peripheral hyperpigmentation involving the left ankle. The remainder of the examination was notable for well-controlled mycosis fungoides with several hyperpigmented patches at sites of prior involvement on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and sent for histopathologic examination.

Modifier -25 and the New 2021 E/M Codes: Documentation of Separate and Distinct Just Got Easier

Insurers Target Modifier -25

Modifier -25 allows reporting of both a minor procedure (ie, one with a 0- or 10-day global period) and a separate and distinct evaluation and management (E/M) service on the same date of service.1 Because of the multicomplaint nature of dermatology, the ability to report a same-day procedure and an E/M service is critical for efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centered dermatologic care. However, it is well known that the use of modifier -25 has been under notable insurer scrutiny and is a common reason for medical record audits.2,3 Some insurers have responded to increased utilization of modifier -25 by cutting reimbursement for claims that include both a procedure and an E/M service or by denying one of the services altogether.4-6 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also have expressed concern about this coding combination with proposed cuts to reimbursement.7 Moreover, the Office of Inspector General has announced a work plan to investigate the frequent utilization of E/M codes and minor procedures by dermatologists.8 Clearly, modifier -25 is a continued target by insurers and regulators; therefore, dermatologists will want to make sure their coding and documentation meet all requirements and are updated for the new E/M codes for 2021.

The American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology indicates that modifier -25 allows reporting of a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of a procedure or other service.”1 Given that dermatology patients typically present with multiple concerns, dermatologists commonly evaluate and treat numerous conditions during one visit. Understanding what constitutes a separately identifiable E/M service is critical to bill accurately and to pass insurer audits.

Global Surgical Package

To appropriately bill both a procedure and an E/M service, the physician must indicate that the patient’s condition required an E/M service above and beyond the usual work of the procedure. The compilation of evaluation and work included in the payment for a procedure is called the global surgical package.9 In general, the global surgical package includes local or topical anesthesia; the surgical service/procedure itself; immediate postoperative care, including dictating the operative note; meeting/discussing the patient’s procedure with family and other physicians; and writing orders for the patient. For minor procedures (ie, those with either 0- or 10-day global periods), the surgical package also includes same-day E/M services associated with the decision to perform surgery. An appropriate history and physical examination as well as a discussion of the differential diagnosis, treatment options, and risk and benefits of treatment are all included in the payment of a minor procedure itself. Therefore, an evaluation to discuss a patient’s condition or change in condition, alternatives to treatment, or next steps after a diagnosis related to a treatment or diagnostic procedure should not be separately reported. Moreover, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not in itself sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M service with these minor procedures. For major procedures (ie, those with 90-day postoperative periods), the decision for surgery is excluded from the global surgical package.

2021 E/M Codes Simplify Documentation

The biggest coding change of 2021 was the new E/M codes.10 Prior to this year, the descriptors of E/M services recognized 7 components to define the levels of E/M services11: history and nature of the presenting problem; physical examination; medical decision-making (MDM); counseling; coordination of care; and time. Furthermore, history, physical examination, and MDM were all broken down into more granular elements that were summed to determine the level for each component; for example, the history of the presenting problem was defined as a chronological description of the development of the patient’s present illness, including the following elements: location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms. Each of these categories would constitute bullet points to be summed to determine the level of history. Physical examination and MDM bullet points also would be summed to determine a proper coding level.11 Understandably, this coding scheme was complicated and burdensome to medical providers.

The redefinition of the E/M codes for 2021 substantially simplified the determination of coding level and documentation.10 The revisions to the E/M office visit code descriptors and documentation standards are now centered around how physicians think and take care of patients and not on mandatory standards and checking boxes. The main changes involve MDM as the prime determinant of the coding level. Elements of MDM affecting coding for an outpatient or office visit now include only 3 components: the number and complexity of problems addressed in the encounter, the amount or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and the risk of complications or morbidity of patient management. Gone are the requirements from the earlier criteria requiring so many bullet points for the history, physical examination, and MDM.

Dermatologists may ask, “How does the new E/M coding structure affect reporting and documenting an E/M and a procedure on the same day?” The answer is that the determination of separate and distinct is basically unchanged with the new E/M codes; however, the documentation requirements for modifier -25 using the new E/M codes are simplified.

As always, the key to determining whether a separate and distinct E/M service was provided and subsequently documented is to deconstruct the medical note. All evaluation services associated with the procedure—making a clinical diagnosis or differential diagnosis, decision to perform surgery, and discussion of alternative treatments—should be removed from one’s documentation as shown in the example below. If a complete E/M service still exists, then an E/M may be billed in addition to the procedure. Physical examination of the treatment area is included in the surgical package. With the prior E/M criteria, physical examination of the procedural area could not be used again as a bullet point to count for the E/M level. However, with the new 2021 coding requirements, the documentation of a separate MDM will be sufficient to meet criteria because documentation of physical examination is not a requirement.

Modifier -25 Examples

Let’s examine a typical dermatologist medical note. An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. The patient also complains of a growing tender lesion on the left elbow of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination reveals a linear vesicular eruption on the left wrist and a tender hyperkeratotic papule on the left elbow. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed. The decision is made to perform a tangential biopsy of the lesion on the left elbow because of the suspicion for malignancy. The biopsy is performed the same day.

This case clearly illustrates performance of an E/M service in the treatment of rhus dermatitis, which is separate and distinct from the biopsy procedure; however, in evaluating whether the case meets the documentation requirements for modifier -25, the information in the medical note inclusive to the procedure’s global surgical package, including history associated with establishing the diagnosis, physical examination of the procedure area(s), and discussion of treatment options, is eliminated, leaving the following notes: An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed.

Because the physical examination of the body part (left arm) is included in the procedure’s global surgical package, the examination of the left wrist cannot be used as coding support for the E/M service. This makes a difference for coding level in the prior E/M coding requirements, which required examination bullet points. However, with the 2021 E/M codes, documentation of physical examination bullet points is irrelevant to the coding level. Therefore, qualifying for a modifier -25 claim is more straightforward in this case with the new code set. Because bullet points are not integral to the 2021 E/M codes, qualifying and properly documenting for a higher level of service will likely be more common in dermatology.

Final Thoughts

Frequent use of modifier -25 is a critical part of a high-quality and cost-effective dermatology practice. Same-day performance of minor procedures and E/M services allows for more rapid and efficient diagnosis and treatment of various conditions as well as minimizing unnecessary office visits. The new E/M codes for 2021 actually make the documentation of a separate and distinct E/M service less complicated because the bullet point requirements associated with the old E/M codes have been eliminated. Understanding how the new E/M code descriptors affect modifier -25 reporting and clear documentation of separate, distinct, and medically necessary E/M services will be needed due to increased insurer scrutiny and audits.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2021, Professional Edition. American Medical Association; 2020.

- Rogers HW. Modifier −25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- Rogers HW. One diagnosis and modifier −25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Update regarding E/M with modifier −25—professional. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield website. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://providernews.anthem.com/ohio/article/update-regarding-em-with-modifier-25-professional

- Payment policies—surgery. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care website. Updated May 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/provider/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/07/H-6-Surgery-PM.pdf

- Modifier 25: frequently asked questions. Independence Blue Cross website. Updated September 25, 2017. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://provcomm.ibx.com/ibc/archive/pages/A86603B03881756B8525817E00768006.aspx

- Huang G. CMS 2019 fee schedule takes modifier 25 cuts, runs with them. Doctors Management website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.doctors-management.com/cms-2019-feeschedule-modifier25/

- Dermatologist claims for evaluation and management services on the same day as minor surgical procedures. US Department of Health and Humans Services Office of Inspector General website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000577.asp

- Global surgery booklet. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Updated September 2018. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/globallsurgery-icn907166.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M)—office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

- 1997 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf

Insurers Target Modifier -25

Modifier -25 allows reporting of both a minor procedure (ie, one with a 0- or 10-day global period) and a separate and distinct evaluation and management (E/M) service on the same date of service.1 Because of the multicomplaint nature of dermatology, the ability to report a same-day procedure and an E/M service is critical for efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centered dermatologic care. However, it is well known that the use of modifier -25 has been under notable insurer scrutiny and is a common reason for medical record audits.2,3 Some insurers have responded to increased utilization of modifier -25 by cutting reimbursement for claims that include both a procedure and an E/M service or by denying one of the services altogether.4-6 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also have expressed concern about this coding combination with proposed cuts to reimbursement.7 Moreover, the Office of Inspector General has announced a work plan to investigate the frequent utilization of E/M codes and minor procedures by dermatologists.8 Clearly, modifier -25 is a continued target by insurers and regulators; therefore, dermatologists will want to make sure their coding and documentation meet all requirements and are updated for the new E/M codes for 2021.

The American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology indicates that modifier -25 allows reporting of a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of a procedure or other service.”1 Given that dermatology patients typically present with multiple concerns, dermatologists commonly evaluate and treat numerous conditions during one visit. Understanding what constitutes a separately identifiable E/M service is critical to bill accurately and to pass insurer audits.

Global Surgical Package

To appropriately bill both a procedure and an E/M service, the physician must indicate that the patient’s condition required an E/M service above and beyond the usual work of the procedure. The compilation of evaluation and work included in the payment for a procedure is called the global surgical package.9 In general, the global surgical package includes local or topical anesthesia; the surgical service/procedure itself; immediate postoperative care, including dictating the operative note; meeting/discussing the patient’s procedure with family and other physicians; and writing orders for the patient. For minor procedures (ie, those with either 0- or 10-day global periods), the surgical package also includes same-day E/M services associated with the decision to perform surgery. An appropriate history and physical examination as well as a discussion of the differential diagnosis, treatment options, and risk and benefits of treatment are all included in the payment of a minor procedure itself. Therefore, an evaluation to discuss a patient’s condition or change in condition, alternatives to treatment, or next steps after a diagnosis related to a treatment or diagnostic procedure should not be separately reported. Moreover, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not in itself sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M service with these minor procedures. For major procedures (ie, those with 90-day postoperative periods), the decision for surgery is excluded from the global surgical package.

2021 E/M Codes Simplify Documentation

The biggest coding change of 2021 was the new E/M codes.10 Prior to this year, the descriptors of E/M services recognized 7 components to define the levels of E/M services11: history and nature of the presenting problem; physical examination; medical decision-making (MDM); counseling; coordination of care; and time. Furthermore, history, physical examination, and MDM were all broken down into more granular elements that were summed to determine the level for each component; for example, the history of the presenting problem was defined as a chronological description of the development of the patient’s present illness, including the following elements: location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms. Each of these categories would constitute bullet points to be summed to determine the level of history. Physical examination and MDM bullet points also would be summed to determine a proper coding level.11 Understandably, this coding scheme was complicated and burdensome to medical providers.

The redefinition of the E/M codes for 2021 substantially simplified the determination of coding level and documentation.10 The revisions to the E/M office visit code descriptors and documentation standards are now centered around how physicians think and take care of patients and not on mandatory standards and checking boxes. The main changes involve MDM as the prime determinant of the coding level. Elements of MDM affecting coding for an outpatient or office visit now include only 3 components: the number and complexity of problems addressed in the encounter, the amount or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and the risk of complications or morbidity of patient management. Gone are the requirements from the earlier criteria requiring so many bullet points for the history, physical examination, and MDM.

Dermatologists may ask, “How does the new E/M coding structure affect reporting and documenting an E/M and a procedure on the same day?” The answer is that the determination of separate and distinct is basically unchanged with the new E/M codes; however, the documentation requirements for modifier -25 using the new E/M codes are simplified.

As always, the key to determining whether a separate and distinct E/M service was provided and subsequently documented is to deconstruct the medical note. All evaluation services associated with the procedure—making a clinical diagnosis or differential diagnosis, decision to perform surgery, and discussion of alternative treatments—should be removed from one’s documentation as shown in the example below. If a complete E/M service still exists, then an E/M may be billed in addition to the procedure. Physical examination of the treatment area is included in the surgical package. With the prior E/M criteria, physical examination of the procedural area could not be used again as a bullet point to count for the E/M level. However, with the new 2021 coding requirements, the documentation of a separate MDM will be sufficient to meet criteria because documentation of physical examination is not a requirement.

Modifier -25 Examples

Let’s examine a typical dermatologist medical note. An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. The patient also complains of a growing tender lesion on the left elbow of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination reveals a linear vesicular eruption on the left wrist and a tender hyperkeratotic papule on the left elbow. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed. The decision is made to perform a tangential biopsy of the lesion on the left elbow because of the suspicion for malignancy. The biopsy is performed the same day.

This case clearly illustrates performance of an E/M service in the treatment of rhus dermatitis, which is separate and distinct from the biopsy procedure; however, in evaluating whether the case meets the documentation requirements for modifier -25, the information in the medical note inclusive to the procedure’s global surgical package, including history associated with establishing the diagnosis, physical examination of the procedure area(s), and discussion of treatment options, is eliminated, leaving the following notes: An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed.

Because the physical examination of the body part (left arm) is included in the procedure’s global surgical package, the examination of the left wrist cannot be used as coding support for the E/M service. This makes a difference for coding level in the prior E/M coding requirements, which required examination bullet points. However, with the 2021 E/M codes, documentation of physical examination bullet points is irrelevant to the coding level. Therefore, qualifying for a modifier -25 claim is more straightforward in this case with the new code set. Because bullet points are not integral to the 2021 E/M codes, qualifying and properly documenting for a higher level of service will likely be more common in dermatology.

Final Thoughts

Frequent use of modifier -25 is a critical part of a high-quality and cost-effective dermatology practice. Same-day performance of minor procedures and E/M services allows for more rapid and efficient diagnosis and treatment of various conditions as well as minimizing unnecessary office visits. The new E/M codes for 2021 actually make the documentation of a separate and distinct E/M service less complicated because the bullet point requirements associated with the old E/M codes have been eliminated. Understanding how the new E/M code descriptors affect modifier -25 reporting and clear documentation of separate, distinct, and medically necessary E/M services will be needed due to increased insurer scrutiny and audits.

Insurers Target Modifier -25

Modifier -25 allows reporting of both a minor procedure (ie, one with a 0- or 10-day global period) and a separate and distinct evaluation and management (E/M) service on the same date of service.1 Because of the multicomplaint nature of dermatology, the ability to report a same-day procedure and an E/M service is critical for efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centered dermatologic care. However, it is well known that the use of modifier -25 has been under notable insurer scrutiny and is a common reason for medical record audits.2,3 Some insurers have responded to increased utilization of modifier -25 by cutting reimbursement for claims that include both a procedure and an E/M service or by denying one of the services altogether.4-6 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also have expressed concern about this coding combination with proposed cuts to reimbursement.7 Moreover, the Office of Inspector General has announced a work plan to investigate the frequent utilization of E/M codes and minor procedures by dermatologists.8 Clearly, modifier -25 is a continued target by insurers and regulators; therefore, dermatologists will want to make sure their coding and documentation meet all requirements and are updated for the new E/M codes for 2021.

The American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology indicates that modifier -25 allows reporting of a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of a procedure or other service.”1 Given that dermatology patients typically present with multiple concerns, dermatologists commonly evaluate and treat numerous conditions during one visit. Understanding what constitutes a separately identifiable E/M service is critical to bill accurately and to pass insurer audits.

Global Surgical Package

To appropriately bill both a procedure and an E/M service, the physician must indicate that the patient’s condition required an E/M service above and beyond the usual work of the procedure. The compilation of evaluation and work included in the payment for a procedure is called the global surgical package.9 In general, the global surgical package includes local or topical anesthesia; the surgical service/procedure itself; immediate postoperative care, including dictating the operative note; meeting/discussing the patient’s procedure with family and other physicians; and writing orders for the patient. For minor procedures (ie, those with either 0- or 10-day global periods), the surgical package also includes same-day E/M services associated with the decision to perform surgery. An appropriate history and physical examination as well as a discussion of the differential diagnosis, treatment options, and risk and benefits of treatment are all included in the payment of a minor procedure itself. Therefore, an evaluation to discuss a patient’s condition or change in condition, alternatives to treatment, or next steps after a diagnosis related to a treatment or diagnostic procedure should not be separately reported. Moreover, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not in itself sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M service with these minor procedures. For major procedures (ie, those with 90-day postoperative periods), the decision for surgery is excluded from the global surgical package.

2021 E/M Codes Simplify Documentation

The biggest coding change of 2021 was the new E/M codes.10 Prior to this year, the descriptors of E/M services recognized 7 components to define the levels of E/M services11: history and nature of the presenting problem; physical examination; medical decision-making (MDM); counseling; coordination of care; and time. Furthermore, history, physical examination, and MDM were all broken down into more granular elements that were summed to determine the level for each component; for example, the history of the presenting problem was defined as a chronological description of the development of the patient’s present illness, including the following elements: location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms. Each of these categories would constitute bullet points to be summed to determine the level of history. Physical examination and MDM bullet points also would be summed to determine a proper coding level.11 Understandably, this coding scheme was complicated and burdensome to medical providers.

The redefinition of the E/M codes for 2021 substantially simplified the determination of coding level and documentation.10 The revisions to the E/M office visit code descriptors and documentation standards are now centered around how physicians think and take care of patients and not on mandatory standards and checking boxes. The main changes involve MDM as the prime determinant of the coding level. Elements of MDM affecting coding for an outpatient or office visit now include only 3 components: the number and complexity of problems addressed in the encounter, the amount or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and the risk of complications or morbidity of patient management. Gone are the requirements from the earlier criteria requiring so many bullet points for the history, physical examination, and MDM.

Dermatologists may ask, “How does the new E/M coding structure affect reporting and documenting an E/M and a procedure on the same day?” The answer is that the determination of separate and distinct is basically unchanged with the new E/M codes; however, the documentation requirements for modifier -25 using the new E/M codes are simplified.

As always, the key to determining whether a separate and distinct E/M service was provided and subsequently documented is to deconstruct the medical note. All evaluation services associated with the procedure—making a clinical diagnosis or differential diagnosis, decision to perform surgery, and discussion of alternative treatments—should be removed from one’s documentation as shown in the example below. If a complete E/M service still exists, then an E/M may be billed in addition to the procedure. Physical examination of the treatment area is included in the surgical package. With the prior E/M criteria, physical examination of the procedural area could not be used again as a bullet point to count for the E/M level. However, with the new 2021 coding requirements, the documentation of a separate MDM will be sufficient to meet criteria because documentation of physical examination is not a requirement.

Modifier -25 Examples

Let’s examine a typical dermatologist medical note. An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. The patient also complains of a growing tender lesion on the left elbow of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination reveals a linear vesicular eruption on the left wrist and a tender hyperkeratotic papule on the left elbow. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed. The decision is made to perform a tangential biopsy of the lesion on the left elbow because of the suspicion for malignancy. The biopsy is performed the same day.

This case clearly illustrates performance of an E/M service in the treatment of rhus dermatitis, which is separate and distinct from the biopsy procedure; however, in evaluating whether the case meets the documentation requirements for modifier -25, the information in the medical note inclusive to the procedure’s global surgical package, including history associated with establishing the diagnosis, physical examination of the procedure area(s), and discussion of treatment options, is eliminated, leaving the following notes: An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed.

Because the physical examination of the body part (left arm) is included in the procedure’s global surgical package, the examination of the left wrist cannot be used as coding support for the E/M service. This makes a difference for coding level in the prior E/M coding requirements, which required examination bullet points. However, with the 2021 E/M codes, documentation of physical examination bullet points is irrelevant to the coding level. Therefore, qualifying for a modifier -25 claim is more straightforward in this case with the new code set. Because bullet points are not integral to the 2021 E/M codes, qualifying and properly documenting for a higher level of service will likely be more common in dermatology.

Final Thoughts

Frequent use of modifier -25 is a critical part of a high-quality and cost-effective dermatology practice. Same-day performance of minor procedures and E/M services allows for more rapid and efficient diagnosis and treatment of various conditions as well as minimizing unnecessary office visits. The new E/M codes for 2021 actually make the documentation of a separate and distinct E/M service less complicated because the bullet point requirements associated with the old E/M codes have been eliminated. Understanding how the new E/M code descriptors affect modifier -25 reporting and clear documentation of separate, distinct, and medically necessary E/M services will be needed due to increased insurer scrutiny and audits.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2021, Professional Edition. American Medical Association; 2020.

- Rogers HW. Modifier −25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- Rogers HW. One diagnosis and modifier −25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Update regarding E/M with modifier −25—professional. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield website. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://providernews.anthem.com/ohio/article/update-regarding-em-with-modifier-25-professional

- Payment policies—surgery. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care website. Updated May 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/provider/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/07/H-6-Surgery-PM.pdf

- Modifier 25: frequently asked questions. Independence Blue Cross website. Updated September 25, 2017. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://provcomm.ibx.com/ibc/archive/pages/A86603B03881756B8525817E00768006.aspx

- Huang G. CMS 2019 fee schedule takes modifier 25 cuts, runs with them. Doctors Management website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.doctors-management.com/cms-2019-feeschedule-modifier25/

- Dermatologist claims for evaluation and management services on the same day as minor surgical procedures. US Department of Health and Humans Services Office of Inspector General website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000577.asp

- Global surgery booklet. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Updated September 2018. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/globallsurgery-icn907166.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M)—office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

- 1997 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf

- Current Procedural Terminology 2021, Professional Edition. American Medical Association; 2020.

- Rogers HW. Modifier −25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- Rogers HW. One diagnosis and modifier −25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Update regarding E/M with modifier −25—professional. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield website. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://providernews.anthem.com/ohio/article/update-regarding-em-with-modifier-25-professional

- Payment policies—surgery. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care website. Updated May 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/provider/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/07/H-6-Surgery-PM.pdf

- Modifier 25: frequently asked questions. Independence Blue Cross website. Updated September 25, 2017. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://provcomm.ibx.com/ibc/archive/pages/A86603B03881756B8525817E00768006.aspx

- Huang G. CMS 2019 fee schedule takes modifier 25 cuts, runs with them. Doctors Management website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.doctors-management.com/cms-2019-feeschedule-modifier25/

- Dermatologist claims for evaluation and management services on the same day as minor surgical procedures. US Department of Health and Humans Services Office of Inspector General website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000577.asp

- Global surgery booklet. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Updated September 2018. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/globallsurgery-icn907166.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M)—office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

- 1997 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf

Practice Points

- Insurer scrutiny of same-day evaluation and management (E/M) and procedure services has increased, and dermatologists should be prepared for more frequent medical record reviews and audits.

- The new 2021 E/M codes actually reduce the hurdles for reporting a separate and distinct E/M service by eliminating the history and physical examination bullet points of the previous code set.

Increasing Skin of Color Publications in the Dermatology Literature: A Call to Action

The US population is becoming more diverse. By 2044, it is predicted that there will be a majority minority population in the United States.1 Therefore, it is imperative to continue to develop educational mechanisms for all dermatologists to increase and maintain competency in skin of color dermatology, which will contribute to the achievement of health equity for patients with all skin tones and hair types.

Not only is clinical skin of color education necessary, but diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) education for dermatologists also is critical. Clinical examination,2 diagnosis, and treatment of skin and hair disorders across the skin of color spectrum with cultural humility is essential to achieve health equity. If trainees, dermatologists, other specialists, and primary care clinicians are not frequently exposed to patients with darker skin tones and coily hair, the nuances in diagnosing and treating these patients must be learned in alternate ways.

To ready the nation’s physicians and clinicians to care for the growing diverse population, exposure to more images of dermatologic diseases in those with darker skin tones in journal articles, textbooks, conference lectures, and online dermatology image libraries is necessary to help close the skin of color training and practice gap.3,4 The following initiatives demonstrate how Cutis has sought to address these educational gaps and remains committed to improving DEI education in dermatology.

Collaboration With the Skin of Color Society

The Skin of Color Society (SOCS), which was founded in 2004 by Dr. Susan C. Taylor, is a dermatologic organization with more than 800 members representing 32 countries. Its mission includes promoting awareness and excellence within skin of color dermatology through research, education, and mentorship. The SOCS has utilized strategic partnerships with national and international dermatologists, as well as professional medical organizations and community, industry, and corporate groups, to ultimately ensure that patients with skin of color receive the expert care they deserve.5 In 2017, Cutis published the inaugural article in its collaboration with the SOCS,6 and more articles, which undergo regular peer review, continue to be published quarterly (https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/skin-color).

Increase Number of Journal Articles on Skin of Color Topics

Increasing the number of journal articles on skin of color–related topics needs to be intentional, as it is a tool that has been identified as a necessary part of enhancing awareness and subsequently improving patient care. Wilson et al7 used stringent criteria to review all articles published from January 2018 to October 2020 in 52 dermatology journals for inclusion of topics on skin of color, hair in patients with skin of color, diversity and inclusion, and socioeconomic and health care disparities in the skin of color population. The journals they reviewed included publications based on continents with majority skin of color populations, such as Asia, as well as those with minority skin of color populations, such as Europe. During the study period, the percentage of articles covering skin of color ranged from 2.04% to 61.8%, with an average of 16.8%.7

The total number of Cutis articles published during the study period was 709, with 132 (18.62%) meeting the investigators’ criteria for articles on skin of color; these included case reports in which at least 1 patient with skin of color was featured.7 Overall, Cutis ranked 16th of the 52 journals for inclusion of skin of color content. Cutis was one of only a few journals based in North America, a non–skin-of-color–predominant continent, to make the top 16 in this study.7

Some of the 132 skin of color articles published in Cutis were the result of the journal’s collaboration with the SOCS. Through this collaboration, articles were published on a variety of skin of color topics, including DEI (6), alopecia and hair care (5), dermoscopy/optical coherence tomography imaging (1), atopic dermatitis (1), cosmetics (1), hidradenitis suppurativa (1), pigmentation (1), rosacea (1), and skin cancer (2). These articles also resulted in a number of podcast discussions (https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts/dermatology-weekly), including one on dealing with DEI, one on pigmentation, and one on dermoscopy/optical coherence tomography imaging. The latter featured the SOCS Scientific Symposium poster winners in 2020.

The number of articles published specifically through Cutis’s collaboration with the SOCS accounted for only a small part of the journal’s 132 skin of color articles identified in the study by Wilson et al.7 We speculate that Cutis’s display of intentional commitment to supporting the inclusion of skin of color articles in the journal may in turn encourage its broader readership to submit more skin of color–focused articles for peer review.

Wilson et al7 specifically remarked that “Cutis’s [Skin of Color] section in each issue is a promising idea.” They also highlighted Clinics in Dermatology for committing an entire issue to skin of color; however, despite this initiative, Clinics in Dermatology still ranked 35th of 52 journals with regard to the overall percentage of skin of color articles published.7 This suggests that a journal publishing one special issue on skin of color annually is a helpful addition to the literature, but increasing the number of articles related to skin of color in each journal issue, similar to Cutis, will ultimately result in a higher overall number of skin of color articles in the dermatology literature.

Both Amuzie et al4 and Wilson et al7 concluded that the higher a journal’s impact factor, the lower the number of skin of color articles published.However, skin of color articles published in high-impact journals received a higher number of citations than those in other lower-impact journals.4 High-impact journals may use Cutis as a model for increasing the number of skin of color articles they publish, which will have a notable impact on increasing skin of color knowledge and educating dermatologists.

Coverage of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

In another study, Bray et al8 conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from January 2008 to July 2019 to quantify the number of articles specifically focused on DEI in a variety of medical specialties. The field of dermatology had the highest number of articles published on DEI (25) compared to the other specialties, including family medicine (23), orthopedic surgery (12), internal medicine (9), general surgery (7), radiology (6), ophthalmology (2), and anesthesiology (2).8 However, Wilson et al7 found that, out of all the categories of skin of color articles published in dermatology journals during their study period, those focused on DEI made up less than 1% of the total number of articles. Dermatology is off to a great start compared to other specialties, but there is still more work to do in dermatology for DEI. Cutis’s collaboration with the SOCS has resulted in 6 DEI articles published since 2017.

Think Beyond Dermatology Education

The collaboration between Cutis and the SOCS was established to create a series of articles dedicated to increasing the skin of color dermatology knowledge base of the Cutis readership and beyond; however, increased readership and more citations are needed to amplify the reach of the articles published by these skin of color experts. Cutis’s collaboration with SOCS is one mechanism to increase the skin of color literature, but skin of color and DEI articles outside of this collaboration should continue to be published in each issue of Cutis.

The collaboration between SOCS and Cutis was and continues to be a forward-thinking step toward improving skin of color dermatology education, but there is still work to be done across the medical literature with regard to increasing intentional publication of skin of color articles. Nondermatologist clinicians in the Cutis readership benefit from knowledge of skin of color, as all specialties and primary care will see increased patient diversity in their examination rooms.

To further ensure that primary care is not left behind, Cutis has partnered with The Journal of Family Practice to produce a new column called Dx Across the Skin of Color Spectrum (https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/dx-across-skin-color-spectrum), which is co-published in both journals.9,10 These one-page fact sheets highlight images of dermatologic conditions in skin of color as well as images of the same condition in lighter skin, a concept suggested by Cutis Associate Editor, Dr. Candrice R. Heath. The goal of this new column is to increase the accurate diagnosis of dermatologic conditions in skin of color and to highlight health disparities related to a particular condition in an easy-to-understand format. Uniquely, Dr. Heath co-authors this content with family physician Dr. Richard P. Usatine.

Final Thoughts

The entire community of medical journals should continue to develop creative ways to educate their readership. Medical professionals stay up-to-date on best practices through journal articles, textbooks, conferences, and even podcasts. Therefore, it is best to incorporate skin of color knowledge throughout all educational programming, particularly through enduring materials such as journal articles. Wilson et al7 suggested that a minimum of 16.8% of a dermatology journal’s articles in each issue should focus on skin of color in addition to special focus issues, as this will work toward more equitable dermatologic care.

Knowledge is only part of the equation; compassionate care with cultural humility is the other part. Publishing scientific facts about biology and structure, diagnosis, and treatment selection in skin of color, as well as committing to lifelong learning about the differences in our patients despite the absence of shared life or cultural experiences, may be the key to truly impacting health equity.11 We believe that together we will get there one journal article and one citation at a time.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Published March 2015. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patient-physician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Alvarado SM, Feng H. Representation of dark skin images of common dermatologic conditions in educational resources: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1427-1431. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.041

- Amuzie AU, Jia JL, Taylor SC, et al. Skin-of-color article representation in dermatology literature 2009-2019: higher citation counts and opportunities for inclusion [published online March 24, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.063

- Learn more about SOCS. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/

- Subash J, Tull R, McMichael A. Diversity in dermatology: a society devoted to skin of color. Cutis. 2017;99:322-324.

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of colorand diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: an analysis and call to action [published online April 20, 2021]. Int J Womens Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.001

- Bray JK, McMichael AJ, Huang WW, et al. Publication rates on the topic of racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology versus other specialties. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt094243gp.

- Heath CR, Usatine R. Atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2021;107:332. doi:10.12788/cutis.0274

- Heath CR, Usatine R. Psoriasis. Cutis. 2021;108:56. doi:10.12788/cutis.0298

- Jones N, Heath CR. Hair at the intersection of dermatology and anthropology: a conversation on race and relationships [published online August 3, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14721

The US population is becoming more diverse. By 2044, it is predicted that there will be a majority minority population in the United States.1 Therefore, it is imperative to continue to develop educational mechanisms for all dermatologists to increase and maintain competency in skin of color dermatology, which will contribute to the achievement of health equity for patients with all skin tones and hair types.

Not only is clinical skin of color education necessary, but diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) education for dermatologists also is critical. Clinical examination,2 diagnosis, and treatment of skin and hair disorders across the skin of color spectrum with cultural humility is essential to achieve health equity. If trainees, dermatologists, other specialists, and primary care clinicians are not frequently exposed to patients with darker skin tones and coily hair, the nuances in diagnosing and treating these patients must be learned in alternate ways.

To ready the nation’s physicians and clinicians to care for the growing diverse population, exposure to more images of dermatologic diseases in those with darker skin tones in journal articles, textbooks, conference lectures, and online dermatology image libraries is necessary to help close the skin of color training and practice gap.3,4 The following initiatives demonstrate how Cutis has sought to address these educational gaps and remains committed to improving DEI education in dermatology.

Collaboration With the Skin of Color Society

The Skin of Color Society (SOCS), which was founded in 2004 by Dr. Susan C. Taylor, is a dermatologic organization with more than 800 members representing 32 countries. Its mission includes promoting awareness and excellence within skin of color dermatology through research, education, and mentorship. The SOCS has utilized strategic partnerships with national and international dermatologists, as well as professional medical organizations and community, industry, and corporate groups, to ultimately ensure that patients with skin of color receive the expert care they deserve.5 In 2017, Cutis published the inaugural article in its collaboration with the SOCS,6 and more articles, which undergo regular peer review, continue to be published quarterly (https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/skin-color).

Increase Number of Journal Articles on Skin of Color Topics

Increasing the number of journal articles on skin of color–related topics needs to be intentional, as it is a tool that has been identified as a necessary part of enhancing awareness and subsequently improving patient care. Wilson et al7 used stringent criteria to review all articles published from January 2018 to October 2020 in 52 dermatology journals for inclusion of topics on skin of color, hair in patients with skin of color, diversity and inclusion, and socioeconomic and health care disparities in the skin of color population. The journals they reviewed included publications based on continents with majority skin of color populations, such as Asia, as well as those with minority skin of color populations, such as Europe. During the study period, the percentage of articles covering skin of color ranged from 2.04% to 61.8%, with an average of 16.8%.7

The total number of Cutis articles published during the study period was 709, with 132 (18.62%) meeting the investigators’ criteria for articles on skin of color; these included case reports in which at least 1 patient with skin of color was featured.7 Overall, Cutis ranked 16th of the 52 journals for inclusion of skin of color content. Cutis was one of only a few journals based in North America, a non–skin-of-color–predominant continent, to make the top 16 in this study.7

Some of the 132 skin of color articles published in Cutis were the result of the journal’s collaboration with the SOCS. Through this collaboration, articles were published on a variety of skin of color topics, including DEI (6), alopecia and hair care (5), dermoscopy/optical coherence tomography imaging (1), atopic dermatitis (1), cosmetics (1), hidradenitis suppurativa (1), pigmentation (1), rosacea (1), and skin cancer (2). These articles also resulted in a number of podcast discussions (https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts/dermatology-weekly), including one on dealing with DEI, one on pigmentation, and one on dermoscopy/optical coherence tomography imaging. The latter featured the SOCS Scientific Symposium poster winners in 2020.

The number of articles published specifically through Cutis’s collaboration with the SOCS accounted for only a small part of the journal’s 132 skin of color articles identified in the study by Wilson et al.7 We speculate that Cutis’s display of intentional commitment to supporting the inclusion of skin of color articles in the journal may in turn encourage its broader readership to submit more skin of color–focused articles for peer review.

Wilson et al7 specifically remarked that “Cutis’s [Skin of Color] section in each issue is a promising idea.” They also highlighted Clinics in Dermatology for committing an entire issue to skin of color; however, despite this initiative, Clinics in Dermatology still ranked 35th of 52 journals with regard to the overall percentage of skin of color articles published.7 This suggests that a journal publishing one special issue on skin of color annually is a helpful addition to the literature, but increasing the number of articles related to skin of color in each journal issue, similar to Cutis, will ultimately result in a higher overall number of skin of color articles in the dermatology literature.

Both Amuzie et al4 and Wilson et al7 concluded that the higher a journal’s impact factor, the lower the number of skin of color articles published.However, skin of color articles published in high-impact journals received a higher number of citations than those in other lower-impact journals.4 High-impact journals may use Cutis as a model for increasing the number of skin of color articles they publish, which will have a notable impact on increasing skin of color knowledge and educating dermatologists.

Coverage of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

In another study, Bray et al8 conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from January 2008 to July 2019 to quantify the number of articles specifically focused on DEI in a variety of medical specialties. The field of dermatology had the highest number of articles published on DEI (25) compared to the other specialties, including family medicine (23), orthopedic surgery (12), internal medicine (9), general surgery (7), radiology (6), ophthalmology (2), and anesthesiology (2).8 However, Wilson et al7 found that, out of all the categories of skin of color articles published in dermatology journals during their study period, those focused on DEI made up less than 1% of the total number of articles. Dermatology is off to a great start compared to other specialties, but there is still more work to do in dermatology for DEI. Cutis’s collaboration with the SOCS has resulted in 6 DEI articles published since 2017.

Think Beyond Dermatology Education