User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Reddish Nodule on the Left Shoulder

Reddish Nodule on the Left Shoulder

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

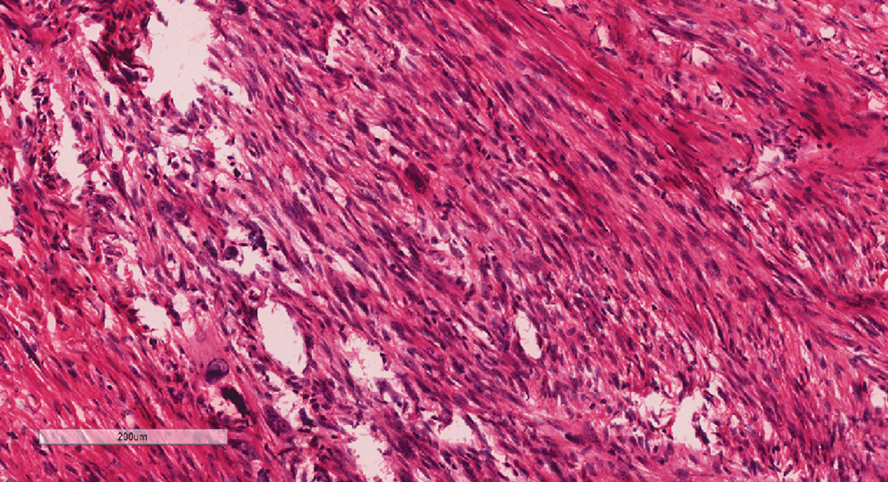

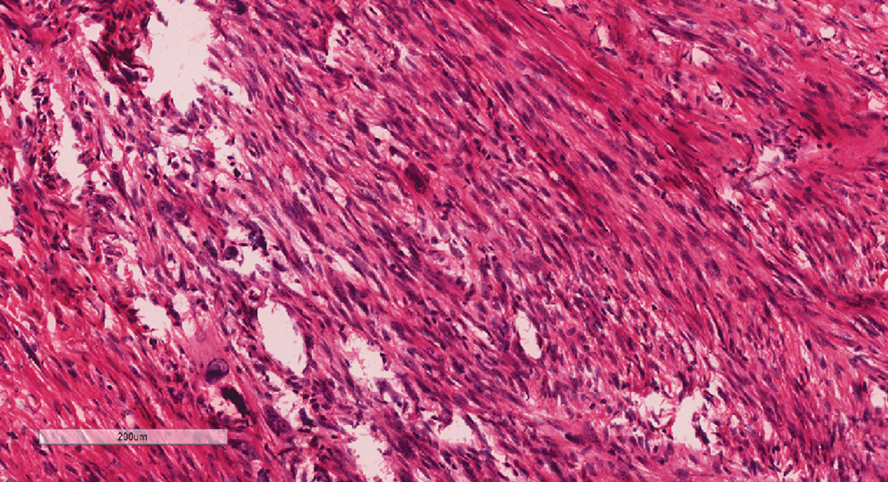

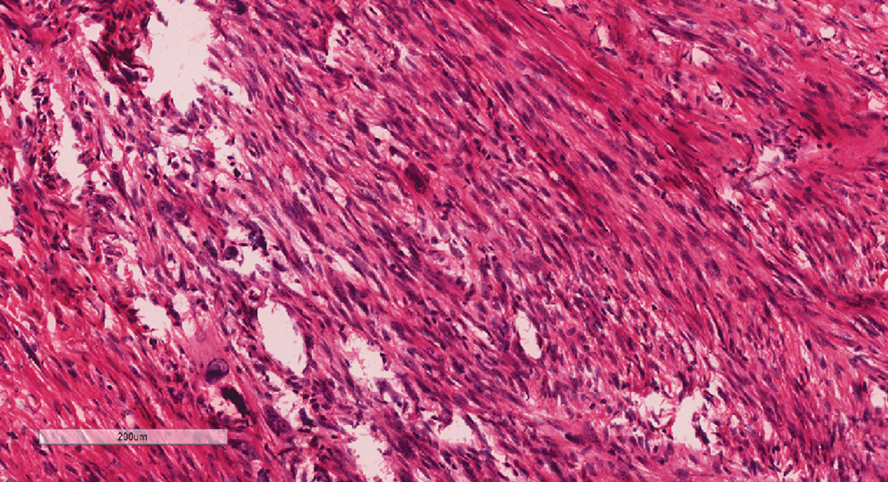

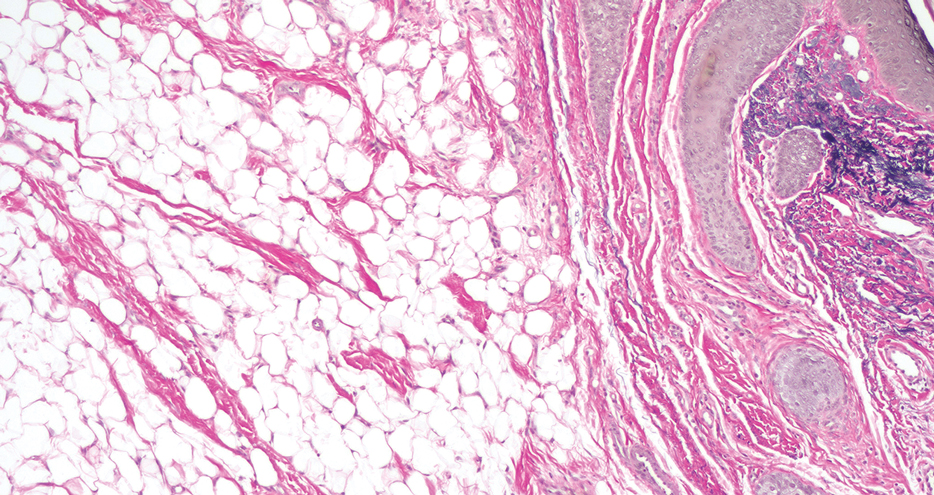

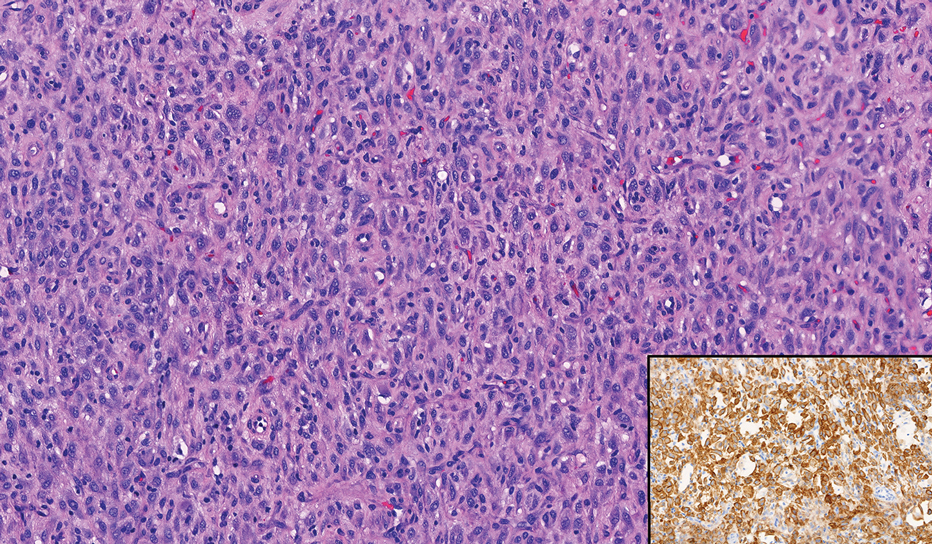

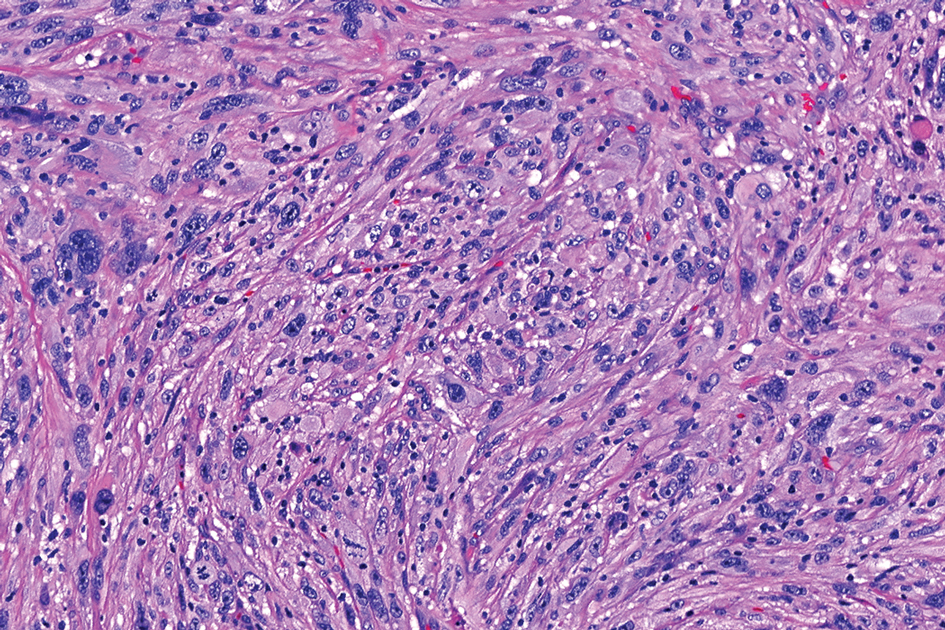

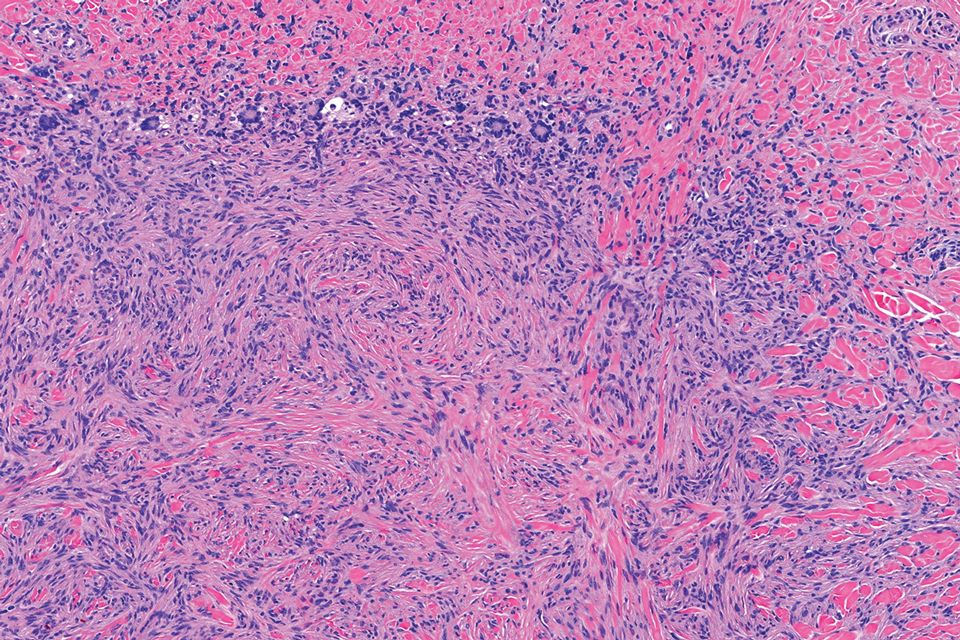

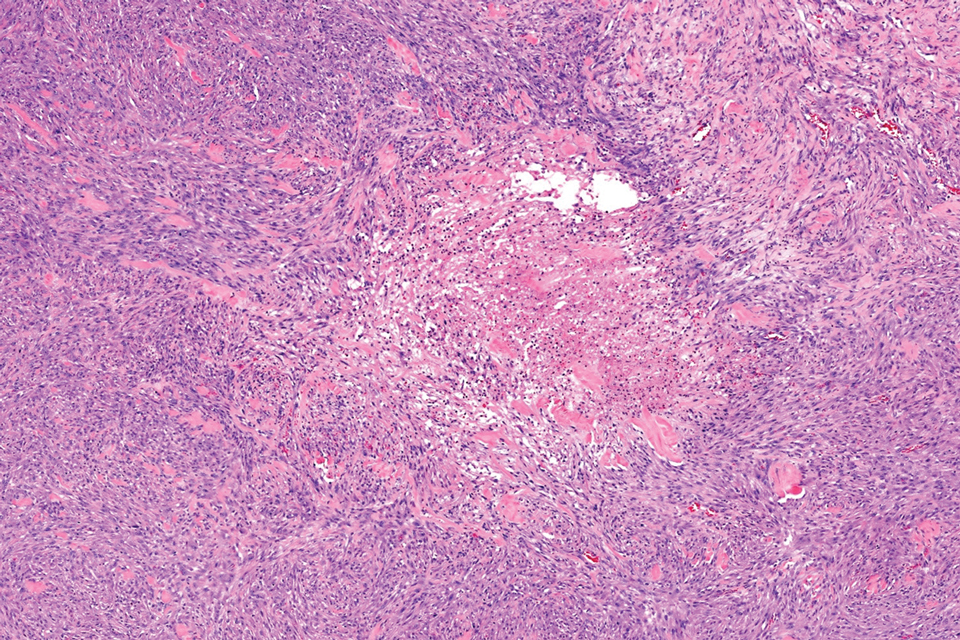

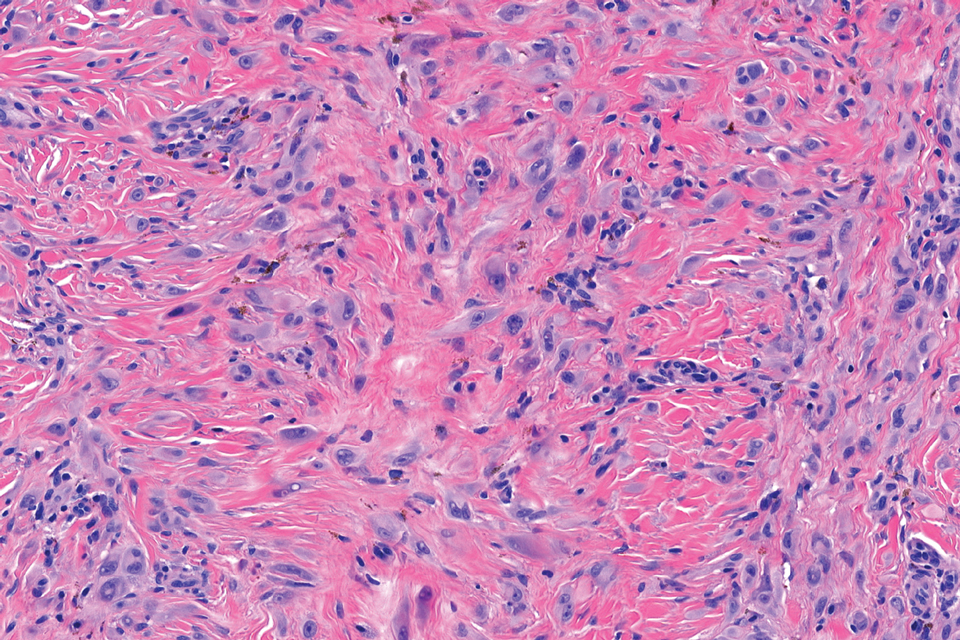

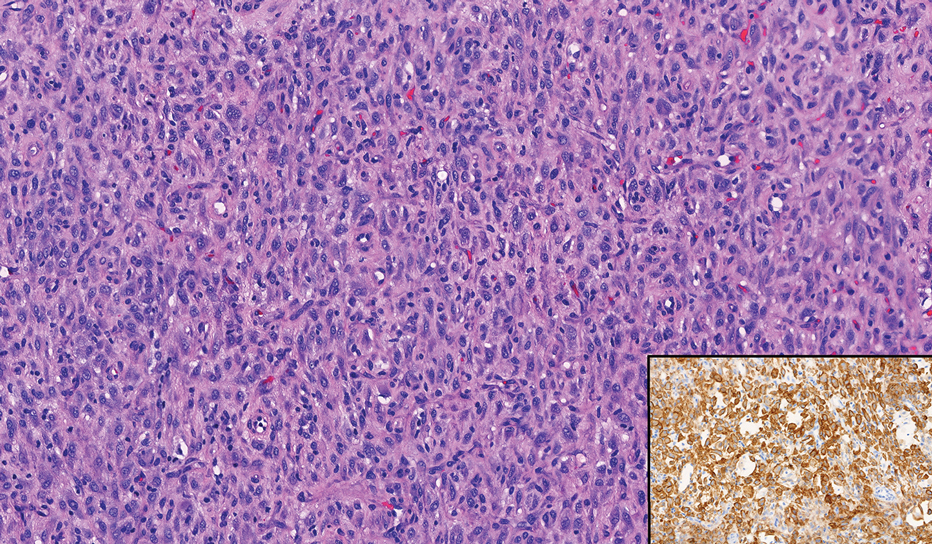

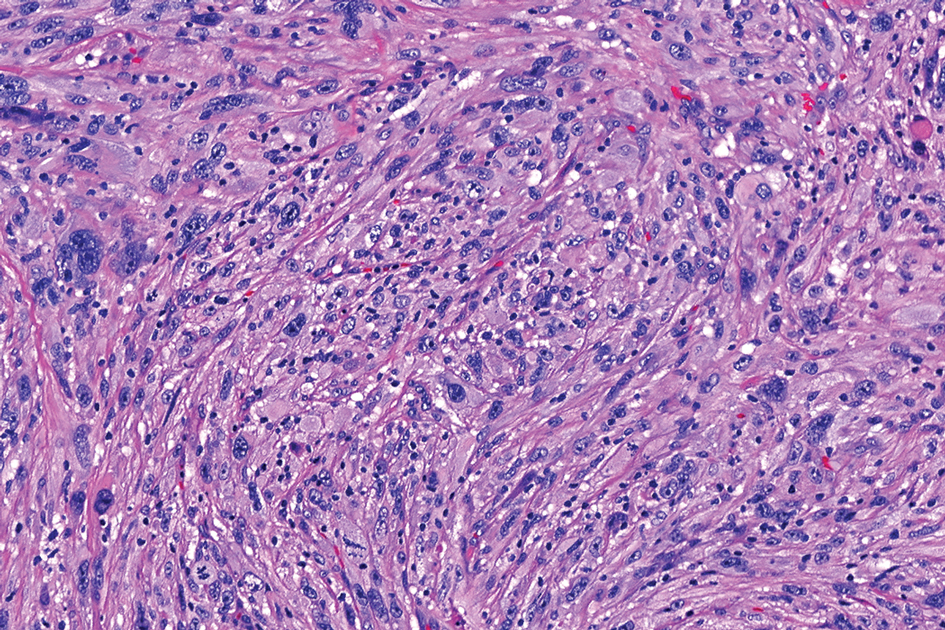

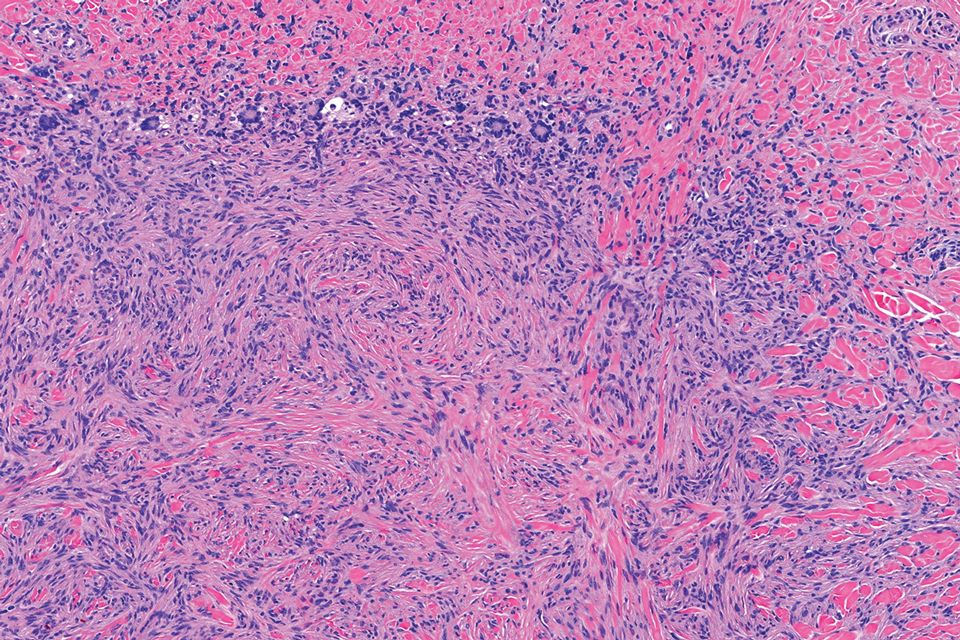

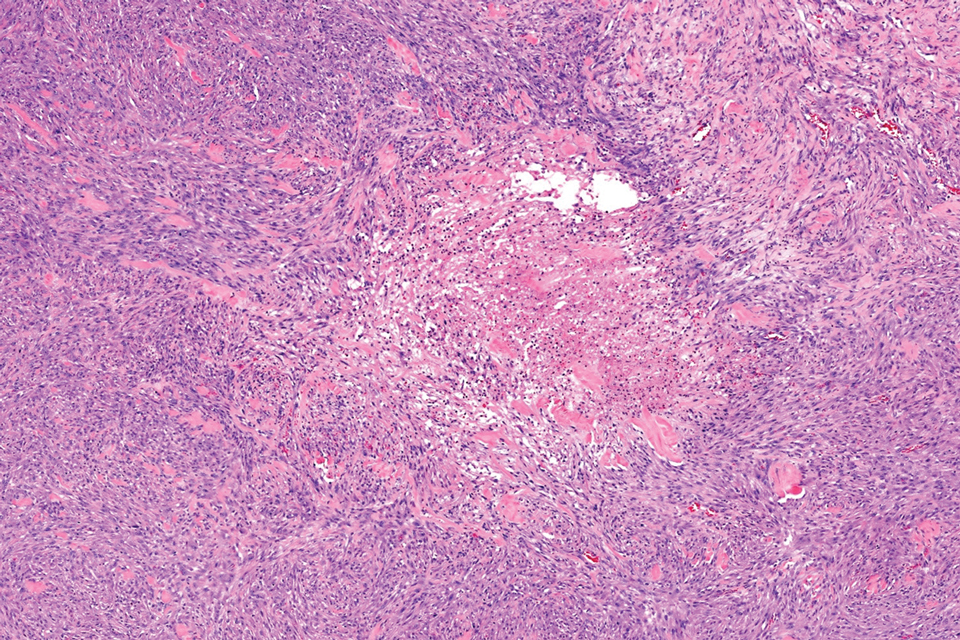

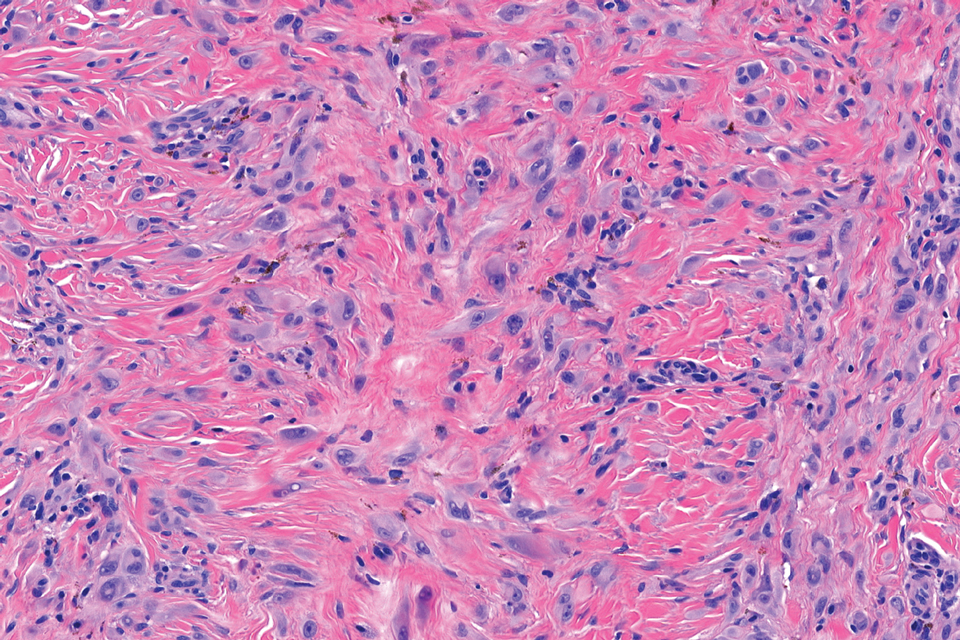

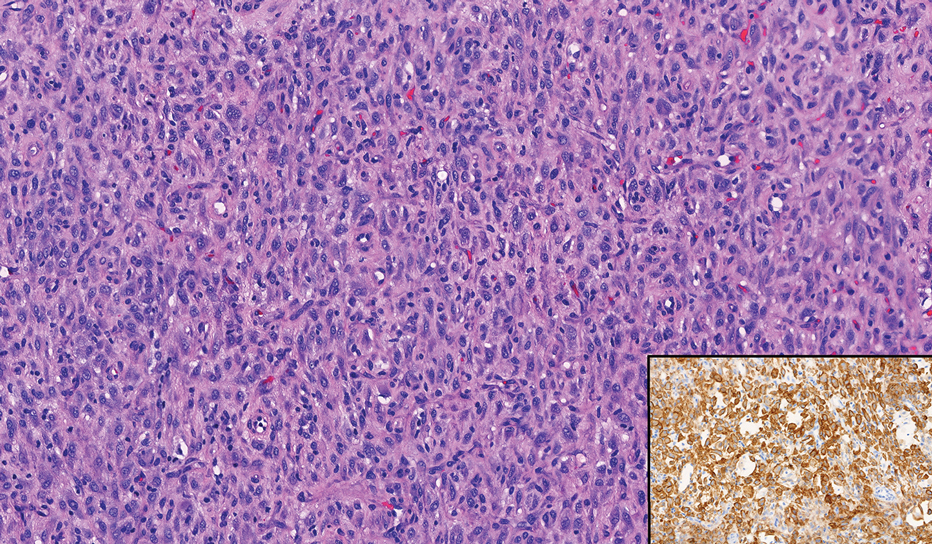

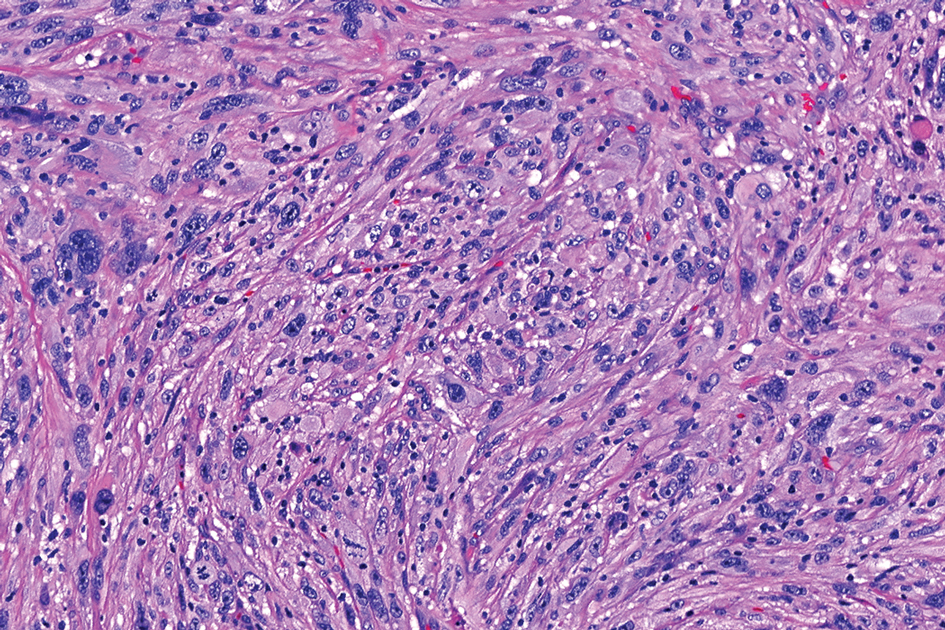

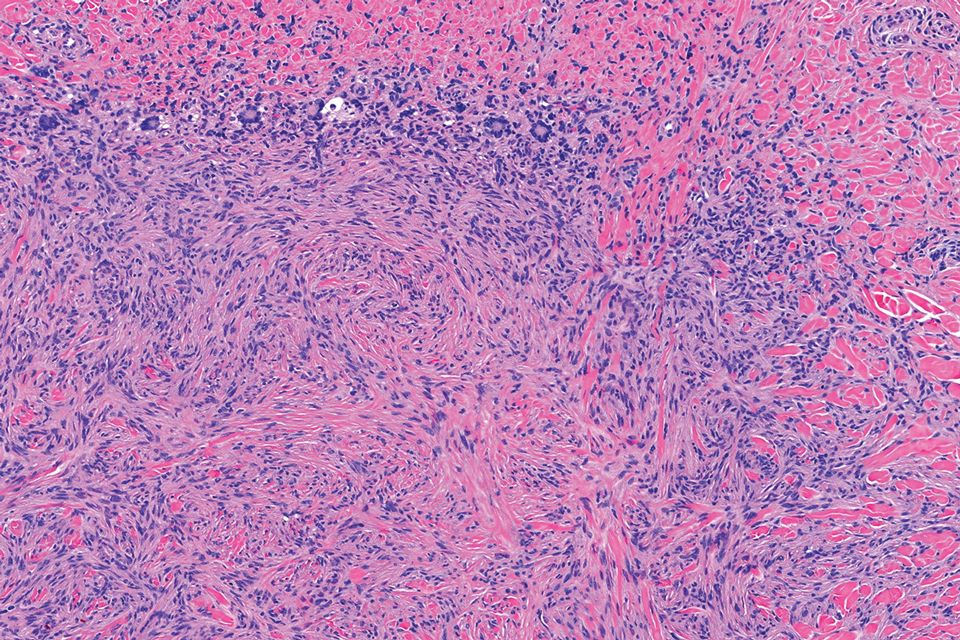

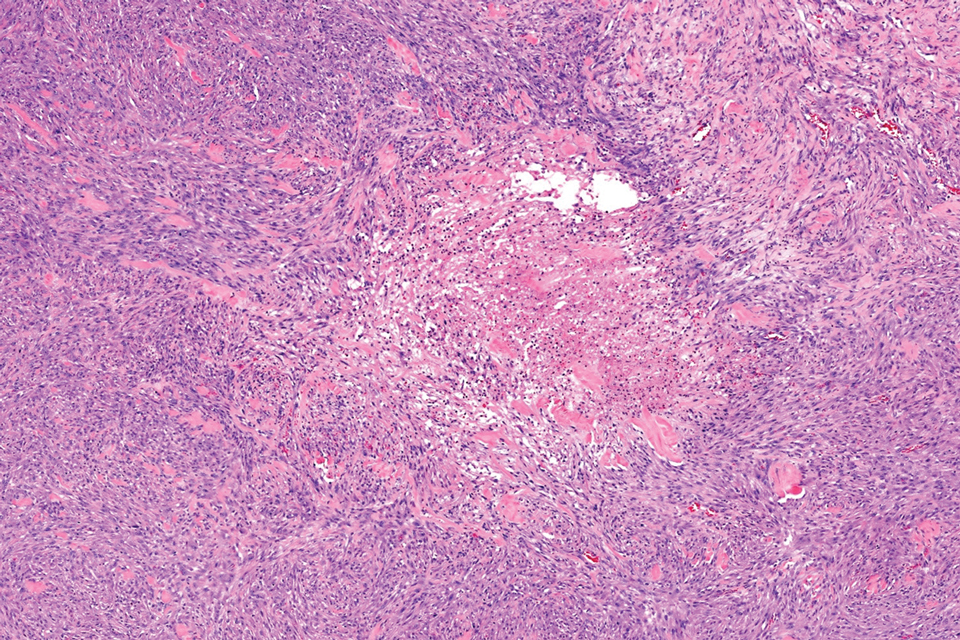

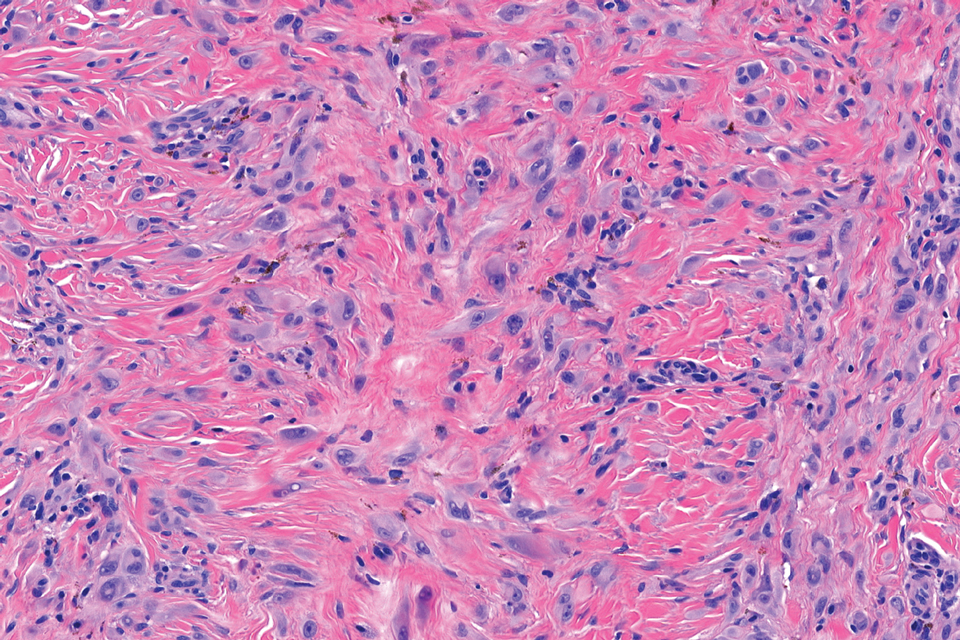

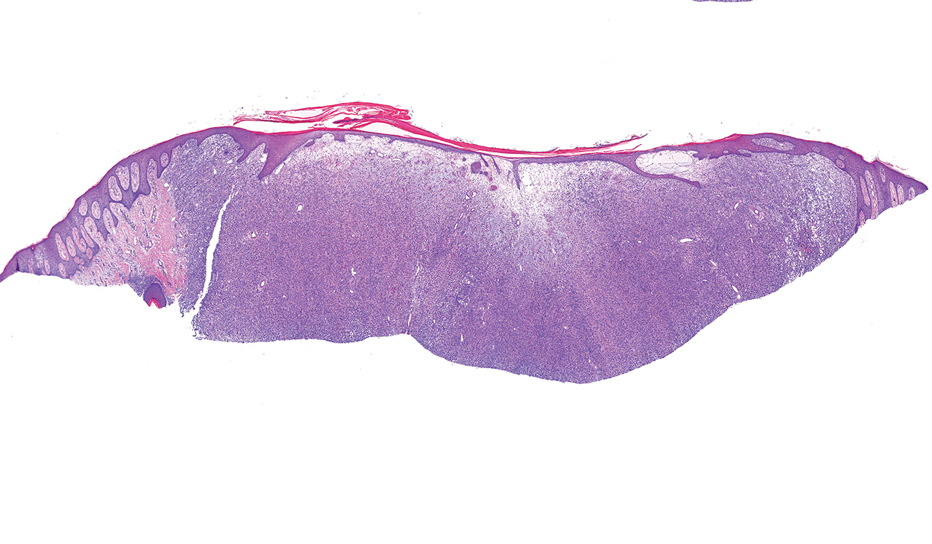

Given the appearance of the nodule and the absence of features of a keloid scar, a soft-tissue or adnexal tumor was suspected. Histology revealed a thin epidermis with loss of rete ridges and a Grenz zone. There was a nodular uncircumscribed dermal proliferation of spindle cells forming interweaving fascicles with elongated ovoid nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure). There was moderate cellular and nuclear atypia, and no necrosis was observed. The spindle cells stained positive for CD10 and negative for AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 5/6, S100, melanoma triple marker, Factor XIII 1, ERG, CD31, CD34, desmin, and smooth muscle actin; ERG, CD31, CD34, and SMA highlighted small vessels within the tumor. The histologic diagnosis was an atypical spindle cell tumor favoring atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). The excisional biopsy margins were clear.

The patient was referred to surgical oncology to consider re-excision of margins after the diagnosis was made. A chest radiograph was clear, and magnetic resonance imaging showed mild skin thickening and image enhancement at the left shoulder—possibly a postsurgical change—with no nodularity suggesting a residual or recurrent tumor. Surgical oncology determined that the patient did not require further excision and placed him on regular follow-up every 2 to 3 months for the next 2 years.

uncertain origin that is considered to be on a spectrum with the more aggressive pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS); it can be distinguished from PDS by histologic features such as nerve or vessel invasion.1 Both entities share oncogenes (eg, tumor protein 53 gene mutations) and are histologically and immunohistochemically similar. Atypical fibroxanthoma largely is viewed as an intermediate-risk tumor that is locally aggressive but rarely metastasizes, with a reported local recurrence rate of 5% to 11% and metastasis risk of 1% to 2%. Conversely, PDS is a more aggressive diagnosis with a high risk for local recurrence and metastasis (7%-69% and 4%-20%, respectively).1

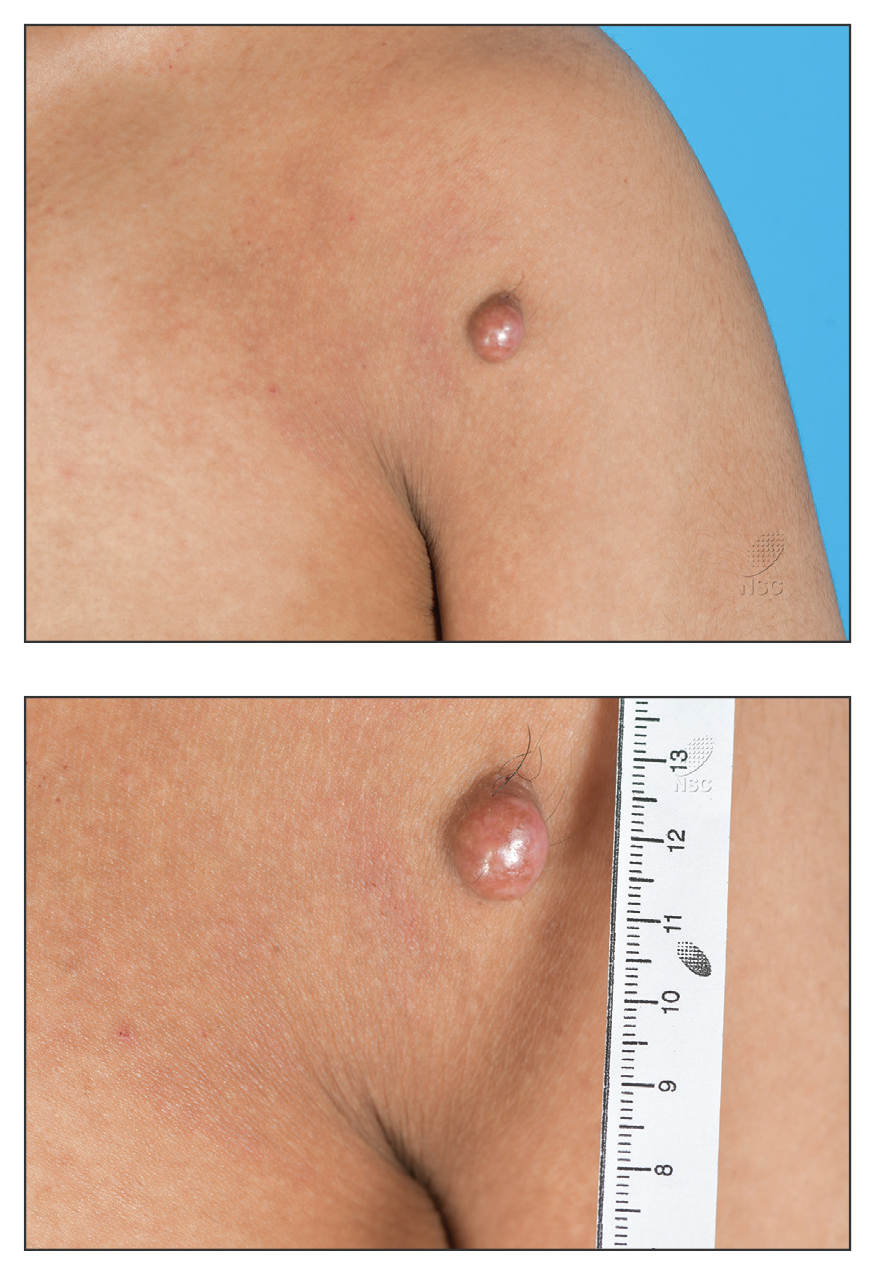

Atypical fibroxanthomas may mimic other entities, both clinically and histologically. It commonly manifests as a flesh-colored to erythematous, sometimes ulcerated nodule on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients, leading to a broad range of clinical differential diagnoses, including other primary cutaneous malignancies (eg, squamous cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma), cutaneous sarcomas (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), adnexal and other tumors (eg, pleomorphic fibroma, pilomatricoma), cutaneous metastases, and even keloid scars. As the differentials can look clinically similar, a skin biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Histologically, AFX tends to show an undifferentiated pleomorphic spindle cell morphology. Notably, histology can be highly variable, with other reported histologic patterns including keloidlike, pleomorphic, epithelioid, rhabdoid, clear-cell, foamy cell, granular cell, bizarre cell, pseudoangiomatous, inflammatory, and osteoclast-rich patterns.2 Thus, the histologic differential diagnosis also is broad, and AFX primarily is a diagnosis of exclusion without specific immunohistochemical markers that serve to exclude other diagnoses. For example, AFX tends to stain positive for CD10 and CD68, though these are not specific markers for AFX. Furthermore, although certain histologic markers may commonly be more positive in AFX than PDS (eg, CD74 stains positive in 20% of AFXs and only 1% of PDSs), this is not reliable enough to be diagnostic.3 As such, AFX is distinguished from PDS primarily by histologic features such as subcutaneous tissue invasion, vascular or perineural invasion, necrosis, or local invasion/ metastases.1 Given the rarity of both tumors, no established management guidelines exist, although excision (wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery) usually is recommended, with some authors suggesting margins of 1 cm for AFX and 2 cm to 3 cm for PDS.1

This atypical case of AFX arising in non–sun-exposed skin in a young man raises questions about whether unknown genetic factors or possibly prior immunosuppression could have contributed to the development of the tumor. A thorough history and physical examination can provide valuable clues for biopsy, including ongoing growth, absence of known prior trauma or acne at the site, and clinical appearance, such as the reddish, solitary, dome-shaped lesion in our patient.

- Ørholt M, Abebe K, Rasmussen LE, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: local recurrence and metastasis in a nationwide population-based cohort of 1118 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1177-1184. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.050

- Agaimy A. The many faces of atypical fibroxanthoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2023;40:306-312. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2023.06.001

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Given the appearance of the nodule and the absence of features of a keloid scar, a soft-tissue or adnexal tumor was suspected. Histology revealed a thin epidermis with loss of rete ridges and a Grenz zone. There was a nodular uncircumscribed dermal proliferation of spindle cells forming interweaving fascicles with elongated ovoid nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure). There was moderate cellular and nuclear atypia, and no necrosis was observed. The spindle cells stained positive for CD10 and negative for AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 5/6, S100, melanoma triple marker, Factor XIII 1, ERG, CD31, CD34, desmin, and smooth muscle actin; ERG, CD31, CD34, and SMA highlighted small vessels within the tumor. The histologic diagnosis was an atypical spindle cell tumor favoring atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). The excisional biopsy margins were clear.

The patient was referred to surgical oncology to consider re-excision of margins after the diagnosis was made. A chest radiograph was clear, and magnetic resonance imaging showed mild skin thickening and image enhancement at the left shoulder—possibly a postsurgical change—with no nodularity suggesting a residual or recurrent tumor. Surgical oncology determined that the patient did not require further excision and placed him on regular follow-up every 2 to 3 months for the next 2 years.

uncertain origin that is considered to be on a spectrum with the more aggressive pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS); it can be distinguished from PDS by histologic features such as nerve or vessel invasion.1 Both entities share oncogenes (eg, tumor protein 53 gene mutations) and are histologically and immunohistochemically similar. Atypical fibroxanthoma largely is viewed as an intermediate-risk tumor that is locally aggressive but rarely metastasizes, with a reported local recurrence rate of 5% to 11% and metastasis risk of 1% to 2%. Conversely, PDS is a more aggressive diagnosis with a high risk for local recurrence and metastasis (7%-69% and 4%-20%, respectively).1

Atypical fibroxanthomas may mimic other entities, both clinically and histologically. It commonly manifests as a flesh-colored to erythematous, sometimes ulcerated nodule on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients, leading to a broad range of clinical differential diagnoses, including other primary cutaneous malignancies (eg, squamous cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma), cutaneous sarcomas (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), adnexal and other tumors (eg, pleomorphic fibroma, pilomatricoma), cutaneous metastases, and even keloid scars. As the differentials can look clinically similar, a skin biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Histologically, AFX tends to show an undifferentiated pleomorphic spindle cell morphology. Notably, histology can be highly variable, with other reported histologic patterns including keloidlike, pleomorphic, epithelioid, rhabdoid, clear-cell, foamy cell, granular cell, bizarre cell, pseudoangiomatous, inflammatory, and osteoclast-rich patterns.2 Thus, the histologic differential diagnosis also is broad, and AFX primarily is a diagnosis of exclusion without specific immunohistochemical markers that serve to exclude other diagnoses. For example, AFX tends to stain positive for CD10 and CD68, though these are not specific markers for AFX. Furthermore, although certain histologic markers may commonly be more positive in AFX than PDS (eg, CD74 stains positive in 20% of AFXs and only 1% of PDSs), this is not reliable enough to be diagnostic.3 As such, AFX is distinguished from PDS primarily by histologic features such as subcutaneous tissue invasion, vascular or perineural invasion, necrosis, or local invasion/ metastases.1 Given the rarity of both tumors, no established management guidelines exist, although excision (wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery) usually is recommended, with some authors suggesting margins of 1 cm for AFX and 2 cm to 3 cm for PDS.1

This atypical case of AFX arising in non–sun-exposed skin in a young man raises questions about whether unknown genetic factors or possibly prior immunosuppression could have contributed to the development of the tumor. A thorough history and physical examination can provide valuable clues for biopsy, including ongoing growth, absence of known prior trauma or acne at the site, and clinical appearance, such as the reddish, solitary, dome-shaped lesion in our patient.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Given the appearance of the nodule and the absence of features of a keloid scar, a soft-tissue or adnexal tumor was suspected. Histology revealed a thin epidermis with loss of rete ridges and a Grenz zone. There was a nodular uncircumscribed dermal proliferation of spindle cells forming interweaving fascicles with elongated ovoid nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure). There was moderate cellular and nuclear atypia, and no necrosis was observed. The spindle cells stained positive for CD10 and negative for AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 5/6, S100, melanoma triple marker, Factor XIII 1, ERG, CD31, CD34, desmin, and smooth muscle actin; ERG, CD31, CD34, and SMA highlighted small vessels within the tumor. The histologic diagnosis was an atypical spindle cell tumor favoring atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). The excisional biopsy margins were clear.

The patient was referred to surgical oncology to consider re-excision of margins after the diagnosis was made. A chest radiograph was clear, and magnetic resonance imaging showed mild skin thickening and image enhancement at the left shoulder—possibly a postsurgical change—with no nodularity suggesting a residual or recurrent tumor. Surgical oncology determined that the patient did not require further excision and placed him on regular follow-up every 2 to 3 months for the next 2 years.

uncertain origin that is considered to be on a spectrum with the more aggressive pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS); it can be distinguished from PDS by histologic features such as nerve or vessel invasion.1 Both entities share oncogenes (eg, tumor protein 53 gene mutations) and are histologically and immunohistochemically similar. Atypical fibroxanthoma largely is viewed as an intermediate-risk tumor that is locally aggressive but rarely metastasizes, with a reported local recurrence rate of 5% to 11% and metastasis risk of 1% to 2%. Conversely, PDS is a more aggressive diagnosis with a high risk for local recurrence and metastasis (7%-69% and 4%-20%, respectively).1

Atypical fibroxanthomas may mimic other entities, both clinically and histologically. It commonly manifests as a flesh-colored to erythematous, sometimes ulcerated nodule on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients, leading to a broad range of clinical differential diagnoses, including other primary cutaneous malignancies (eg, squamous cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma), cutaneous sarcomas (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), adnexal and other tumors (eg, pleomorphic fibroma, pilomatricoma), cutaneous metastases, and even keloid scars. As the differentials can look clinically similar, a skin biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Histologically, AFX tends to show an undifferentiated pleomorphic spindle cell morphology. Notably, histology can be highly variable, with other reported histologic patterns including keloidlike, pleomorphic, epithelioid, rhabdoid, clear-cell, foamy cell, granular cell, bizarre cell, pseudoangiomatous, inflammatory, and osteoclast-rich patterns.2 Thus, the histologic differential diagnosis also is broad, and AFX primarily is a diagnosis of exclusion without specific immunohistochemical markers that serve to exclude other diagnoses. For example, AFX tends to stain positive for CD10 and CD68, though these are not specific markers for AFX. Furthermore, although certain histologic markers may commonly be more positive in AFX than PDS (eg, CD74 stains positive in 20% of AFXs and only 1% of PDSs), this is not reliable enough to be diagnostic.3 As such, AFX is distinguished from PDS primarily by histologic features such as subcutaneous tissue invasion, vascular or perineural invasion, necrosis, or local invasion/ metastases.1 Given the rarity of both tumors, no established management guidelines exist, although excision (wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery) usually is recommended, with some authors suggesting margins of 1 cm for AFX and 2 cm to 3 cm for PDS.1

This atypical case of AFX arising in non–sun-exposed skin in a young man raises questions about whether unknown genetic factors or possibly prior immunosuppression could have contributed to the development of the tumor. A thorough history and physical examination can provide valuable clues for biopsy, including ongoing growth, absence of known prior trauma or acne at the site, and clinical appearance, such as the reddish, solitary, dome-shaped lesion in our patient.

- Ørholt M, Abebe K, Rasmussen LE, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: local recurrence and metastasis in a nationwide population-based cohort of 1118 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1177-1184. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.050

- Agaimy A. The many faces of atypical fibroxanthoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2023;40:306-312. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2023.06.001

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

- Ørholt M, Abebe K, Rasmussen LE, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: local recurrence and metastasis in a nationwide population-based cohort of 1118 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1177-1184. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.050

- Agaimy A. The many faces of atypical fibroxanthoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2023;40:306-312. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2023.06.001

- Rapini RP. Practical Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

Reddish Nodule on the Left Shoulder

Reddish Nodule on the Left Shoulder

A 20-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a slow-growing nodule on the left shoulder of 1 year’s duration. The patient reported a history of eczema since childhood, which had been treated by an external physician with cyclosporine and methotrexate; however, exact treatment records were unavailable as the patient had been treated at another institution. The eczema had been well controlled over the past year on topical steroids alone. The nodule was asymptomatic, and the patient denied any history of trauma or acne at the affected site. He also denied any family history of similar nodules or other notable skin findings. Physical examination revealed a well circumscribed, 15×12-mm, firm, flesh-colored to reddish nodule on the left shoulder with a slightly whitish center. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 :2717-2744.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venererol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, et al. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:130-139.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I—systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1409-1431.

- Chu DK, Schneider L, Asiniwasis RN, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:274-312.

- Rick JW, Lio P, Atluri S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a guide to transitioning to janus kinase inhibitors. Dermatitis. 2023;34:297-300.

- Prado E, Pastorino AC, Harari DK, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis: a practical treatment guide from the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology and the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol. 2022;6:432-467.

- Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908-919.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397:2151-2168.

- Yu D, Ren Y. Upadacitinib for successful treatment of alopecia universalis in a child: a case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venererol. 2023;103:adv5578.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, et al. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, et al. Dual efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E85-E86.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 :2717-2744.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venererol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, et al. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:130-139.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I—systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1409-1431.

- Chu DK, Schneider L, Asiniwasis RN, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:274-312.

- Rick JW, Lio P, Atluri S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a guide to transitioning to janus kinase inhibitors. Dermatitis. 2023;34:297-300.

- Prado E, Pastorino AC, Harari DK, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis: a practical treatment guide from the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology and the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol. 2022;6:432-467.

- Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908-919.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397:2151-2168.

- Yu D, Ren Y. Upadacitinib for successful treatment of alopecia universalis in a child: a case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venererol. 2023;103:adv5578.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, et al. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, et al. Dual efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E85-E86.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 :2717-2744.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venererol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, et al. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:130-139.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I—systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1409-1431.

- Chu DK, Schneider L, Asiniwasis RN, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:274-312.

- Rick JW, Lio P, Atluri S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a guide to transitioning to janus kinase inhibitors. Dermatitis. 2023;34:297-300.

- Prado E, Pastorino AC, Harari DK, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis: a practical treatment guide from the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology and the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol. 2022;6:432-467.

- Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908-919.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397:2151-2168.

- Yu D, Ren Y. Upadacitinib for successful treatment of alopecia universalis in a child: a case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venererol. 2023;103:adv5578.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, et al. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, et al. Dual efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E85-E86.

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

PRACTICE POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases in pediatric patients.

- Dupilumab is the first-line treatment for severe AD in children and is approved for use in patients aged 6 months and older. Janus kinase inhibitors are approved only for patients aged 12 years and older.

- Upadacitinib may be a safe treatment option for severe AD in children, even those younger than 12 years.

Pedunculated Pink Papule on the Nose

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

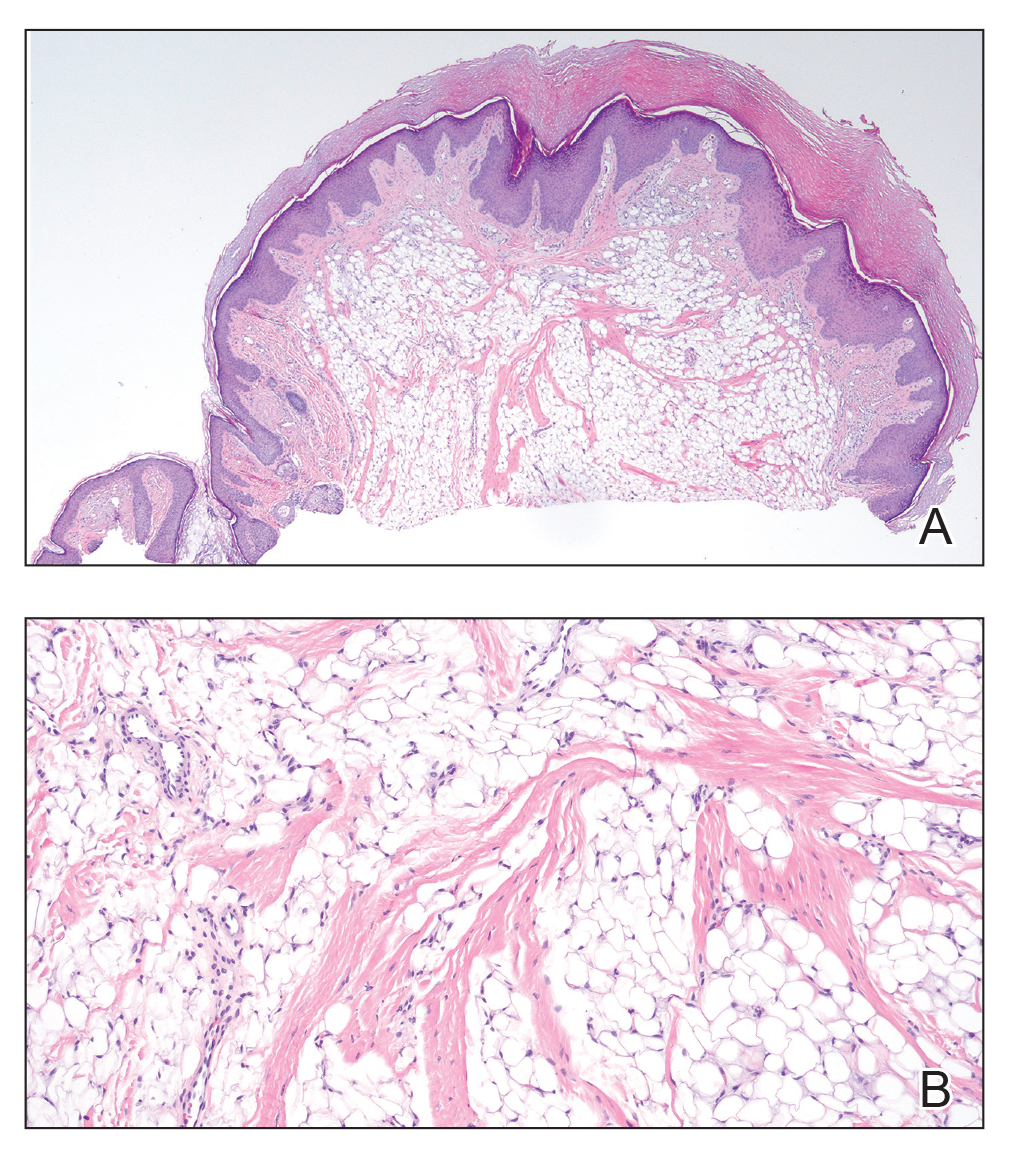

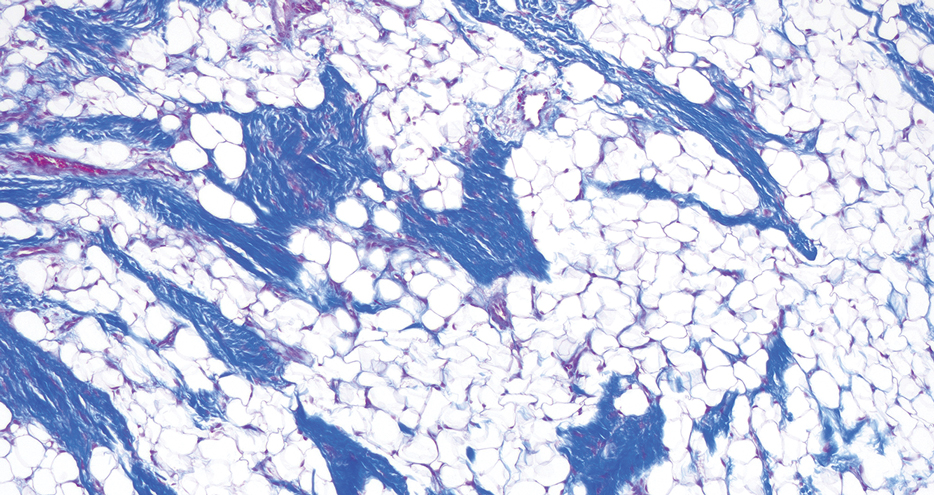

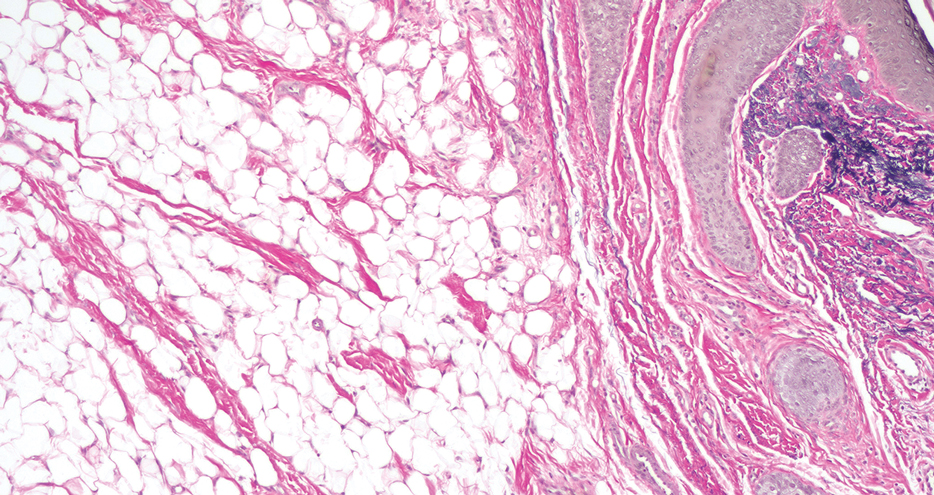

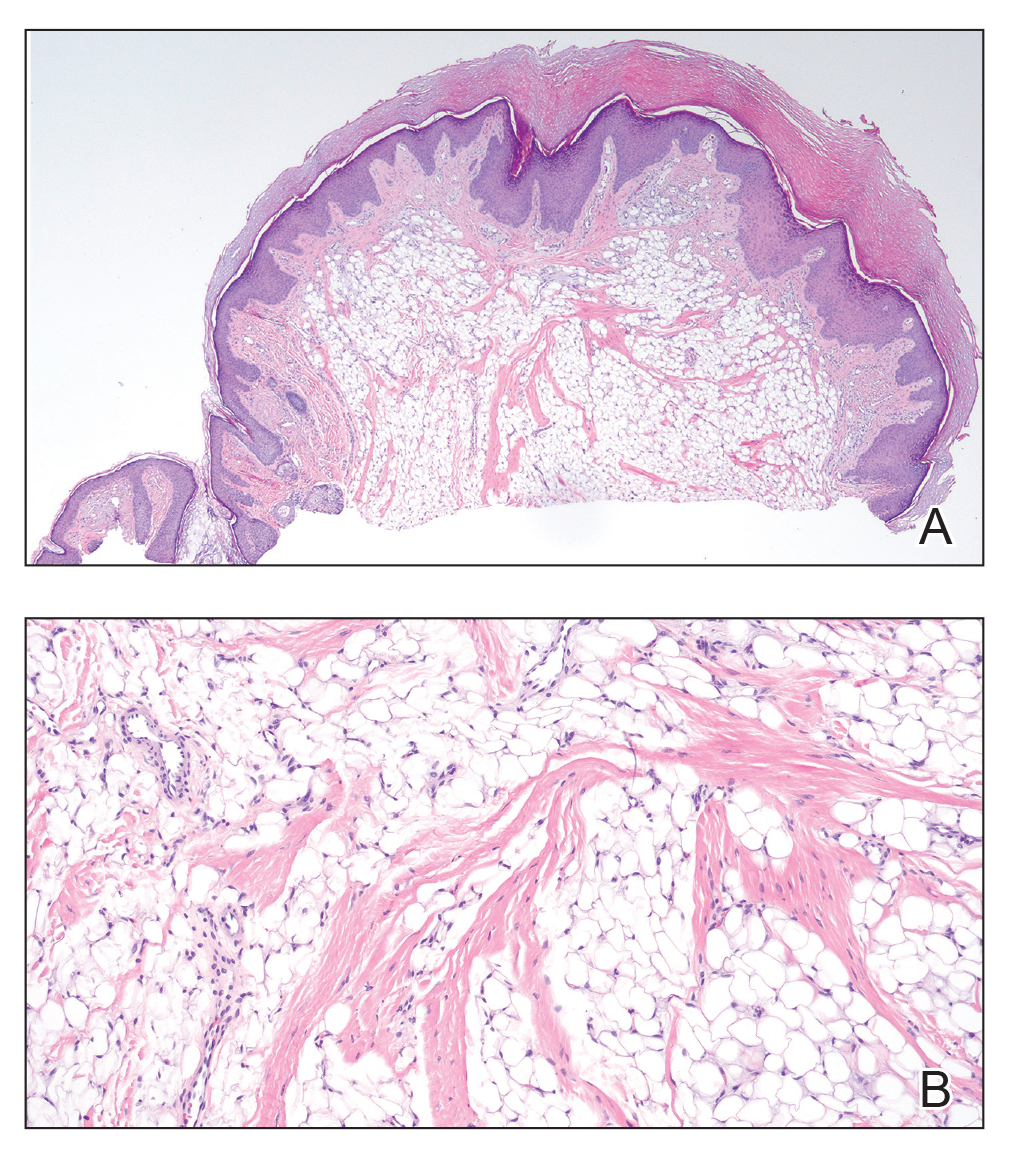

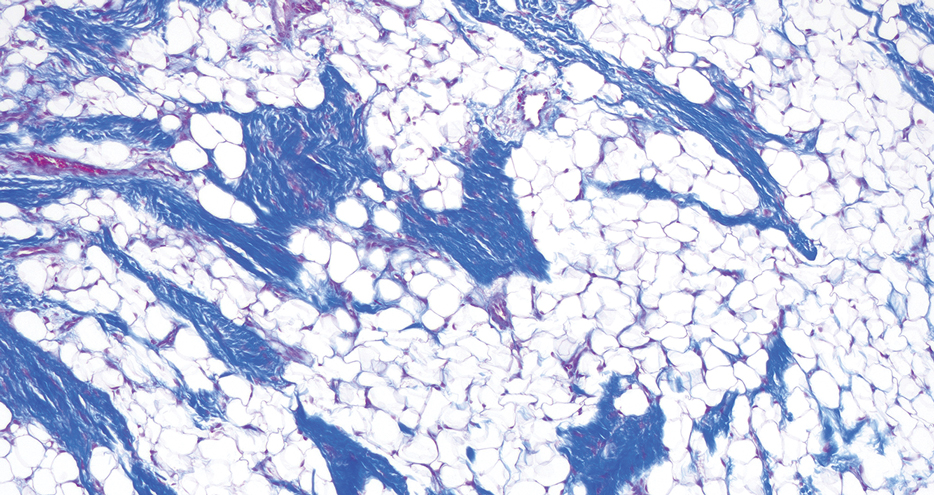

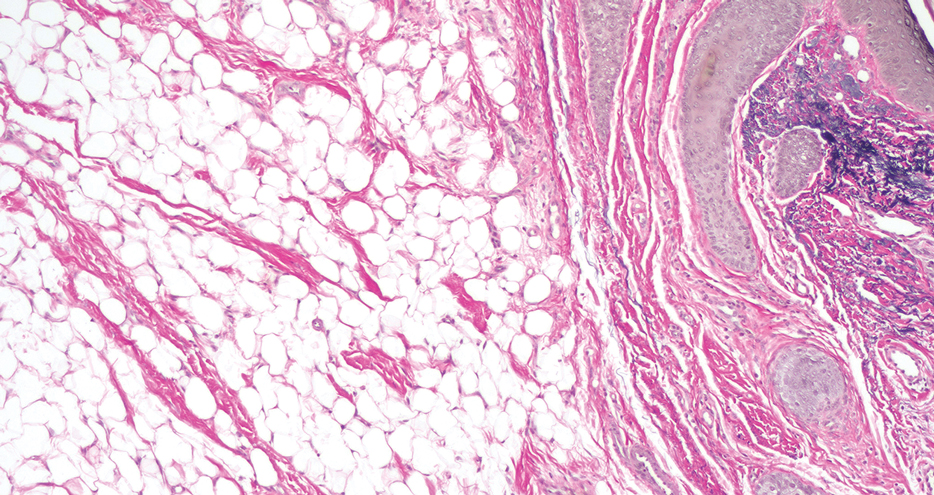

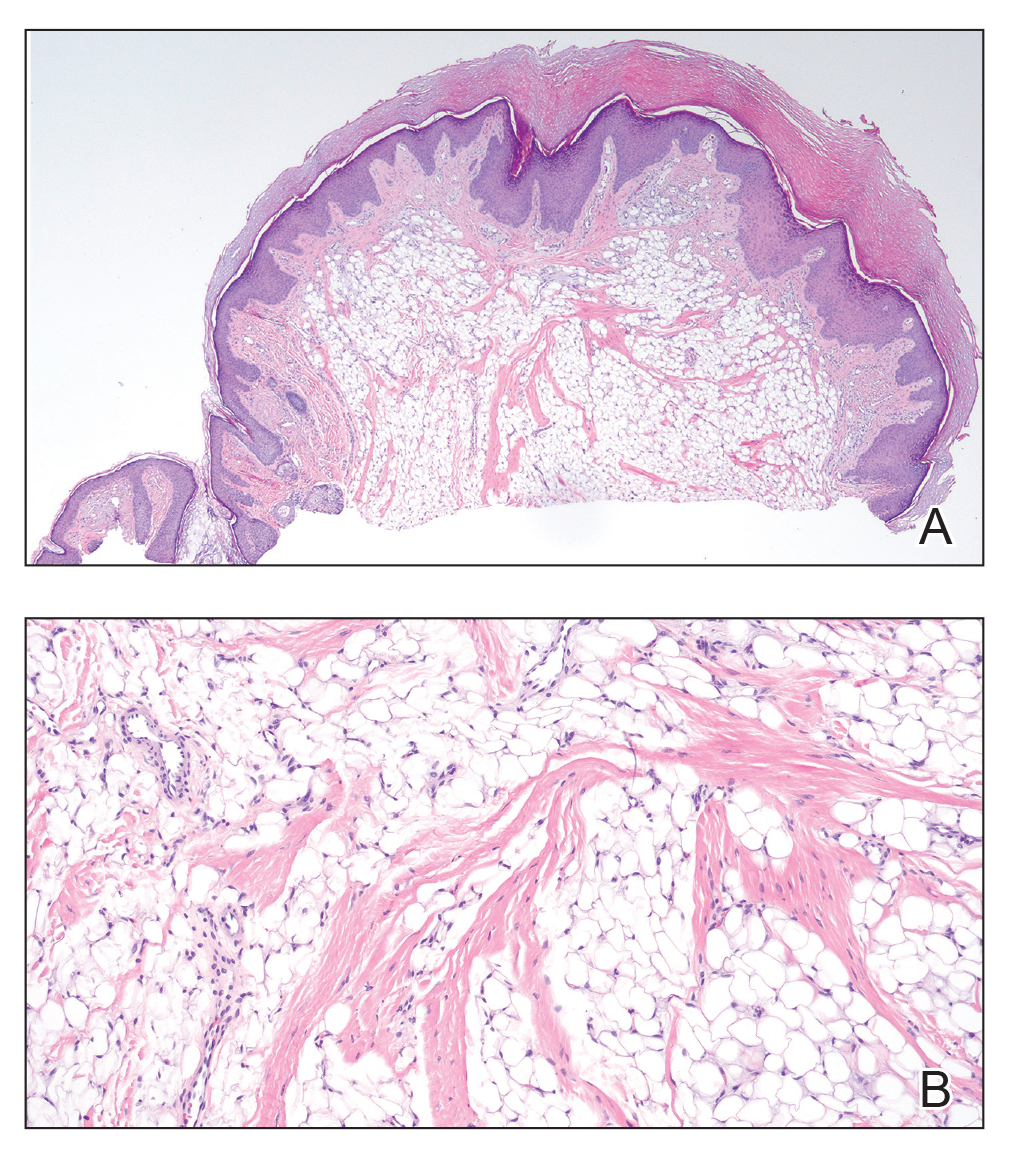

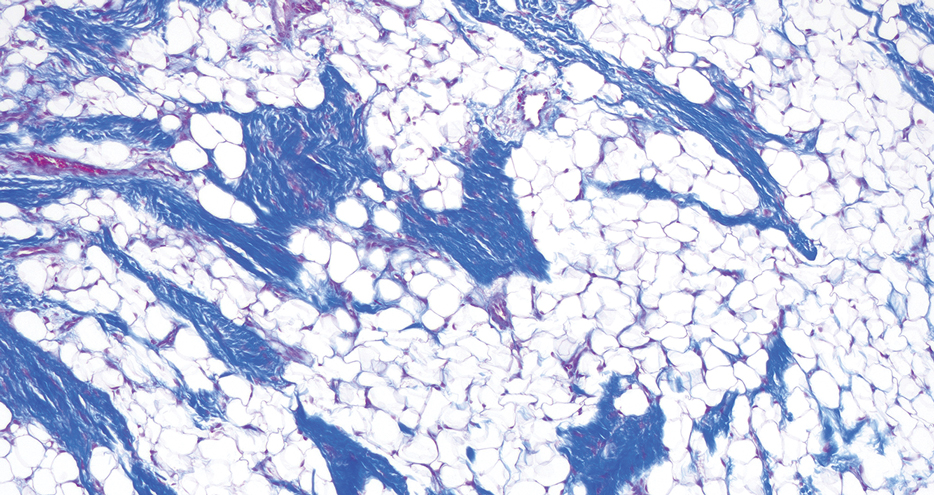

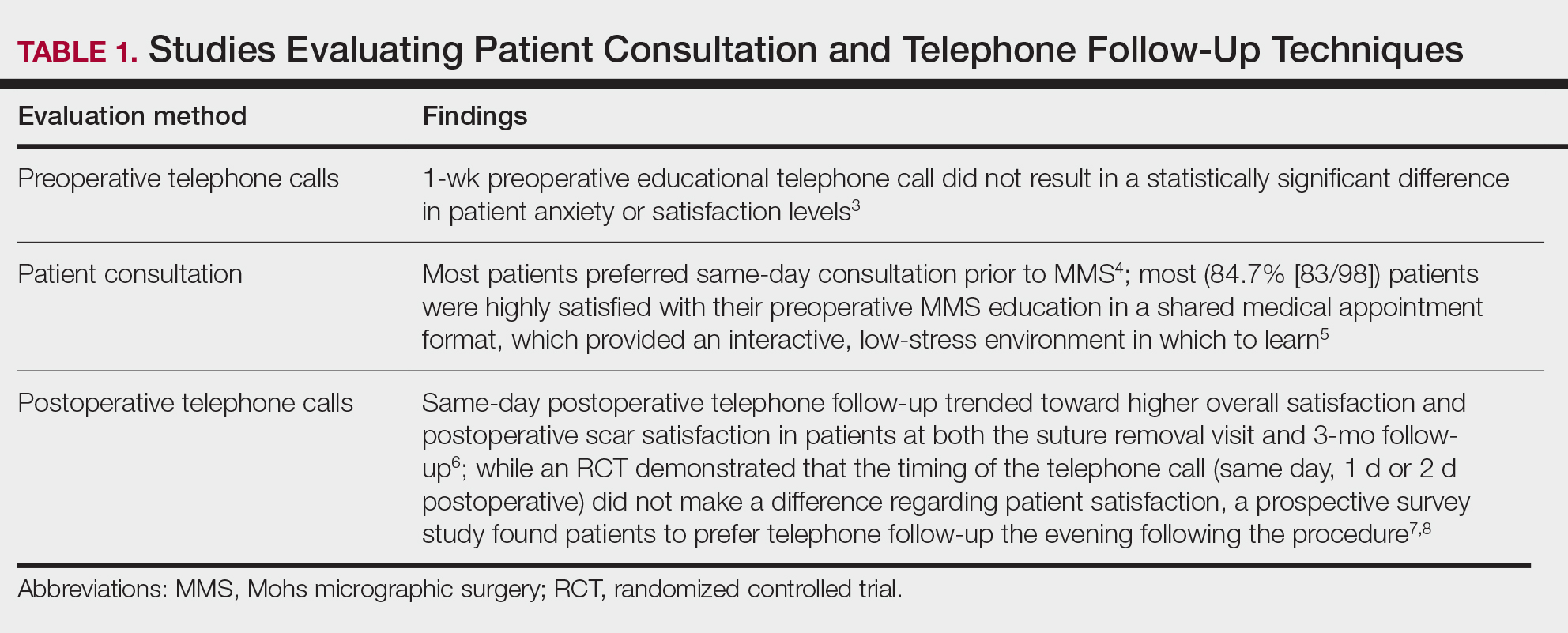

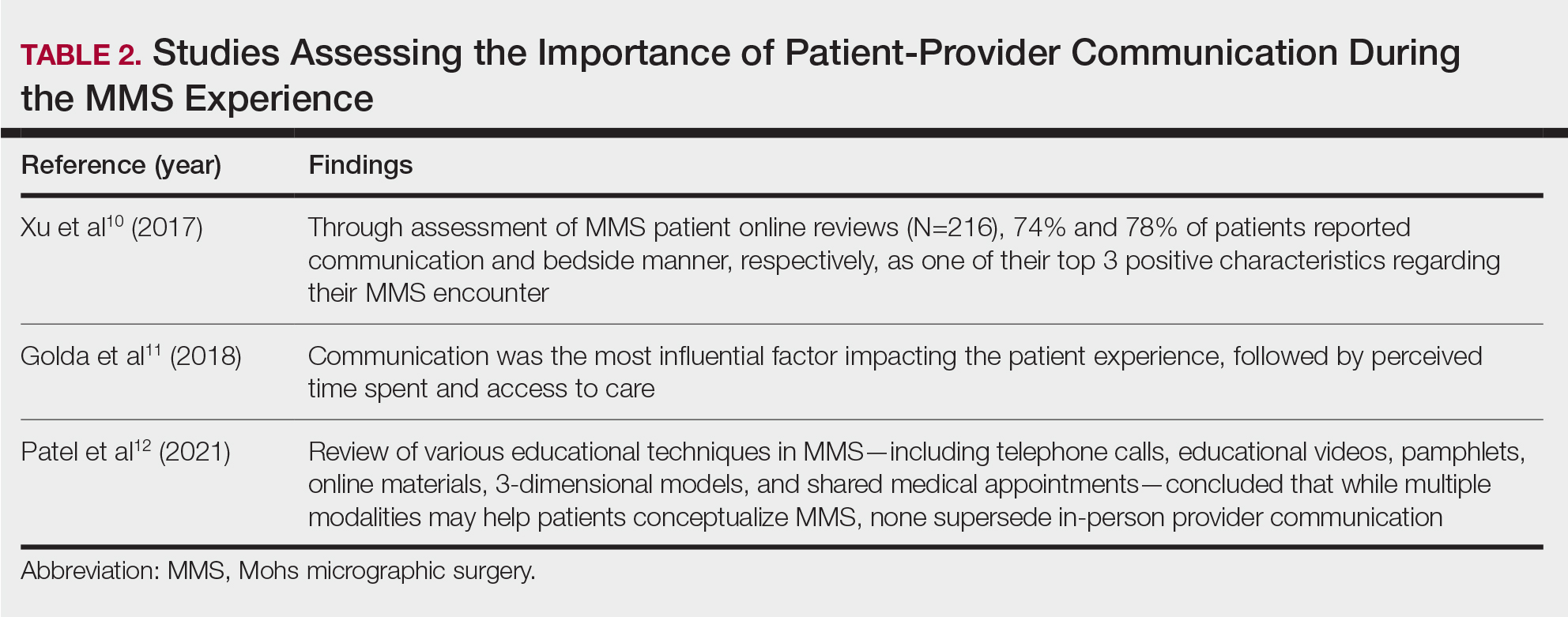

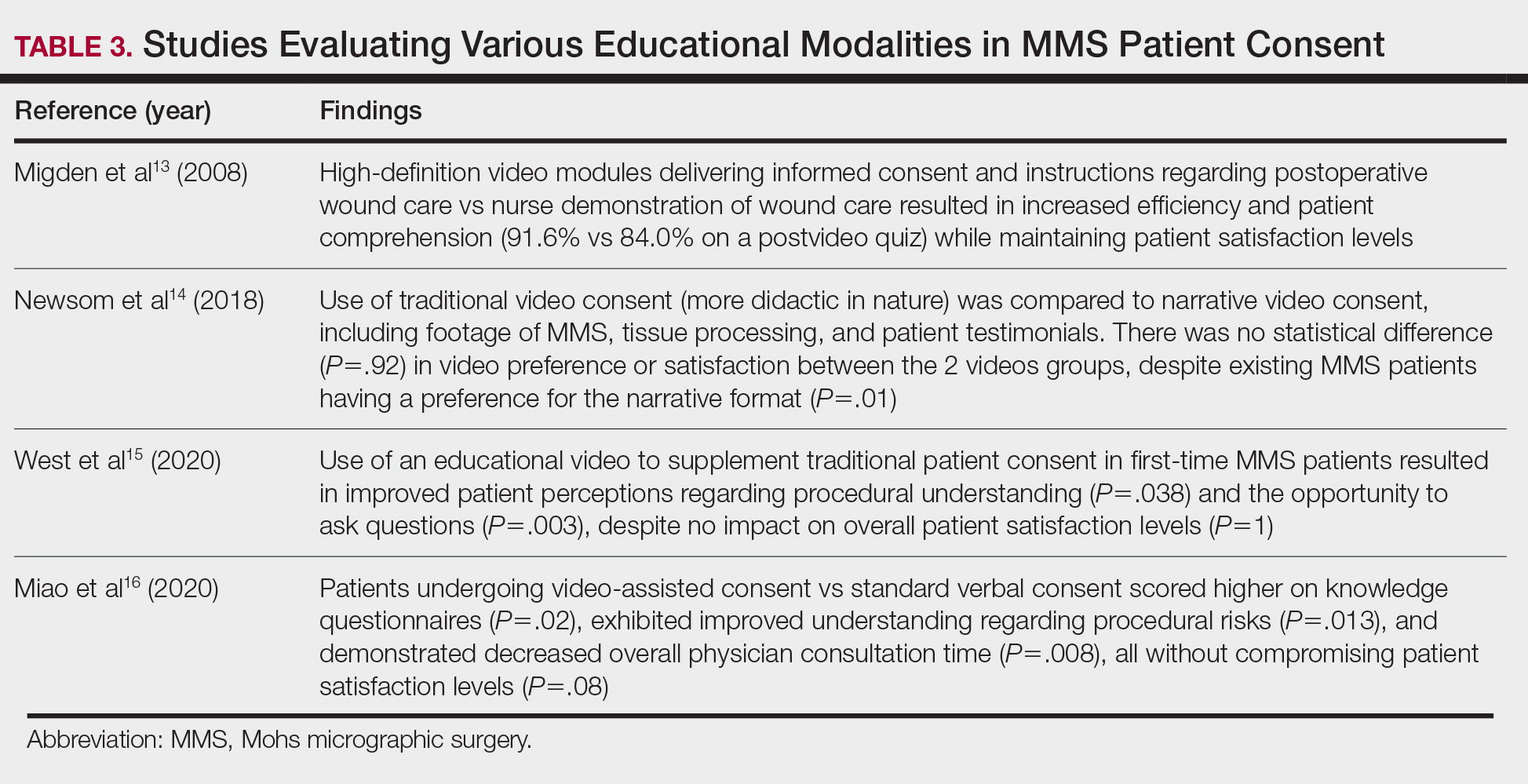

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Uber einen naevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linken Glutaalgegend. Arch Derm Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Chanoki M, Isukos S, Suzuki S, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of the scalp. Cutis. 1989;43:143-144.

- Sáez Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Martin M, Carnerero A, et al. Naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the nose. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:751-752.

- Hassab-El-Naby HMM, Rageh MA. Adult-onset nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis mimicking plane xanthoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:10-11.

- Park HJ, Park CJ, Yi JY, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the face. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:435-437.

- Ioannidou DJ, Stefanidou MP, Panayiotides JG, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (Hoffman-Zurhelle) with localized scleroderma like appearance. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:54-57.

- Nogita T, Wong TY, Hidano A, et al. Pedunculated lipofibroma. a clinicopathologic study of thirty-two cases supporting a simplified nomenclature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):235-240.

- Sawada Y. Solitary nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the forehead. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;16:356-358.

- Knoth W. Uber Naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis Hoffmann-Zurhelle und uber Naevus naevocellularis partim lipomatodes. Dermatologica. 1962;125:161.

- Weitzner S. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:540-542.

- Kaw P, Carlson A, Meyer DR. Nevus lipomatosus (pedunculated lipofibroma) of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:74-76.

- Vano-Galvan S, Moreno C, Vano-Galvan E, et al. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the sole. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:353-354.

- Adotama P, Hutson SD, Rieder EA, et al. Revisiting solitary pedunculated lipofibromas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:954-957.

- Kubin ME, Lantto U, Lindgren O, et al. A rare, recurrent spindle cell lipoma of the nose. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00571.

- Jung SN, Shin JW, Kwon H, et al. Fibrolipoma of the tip of the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:555-556.

- Han XC, Zheng LQ, Shang XL. Dendritic fibromyxolipoma on the nasal tip in an old patient. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7064-7067.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Uber einen naevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linken Glutaalgegend. Arch Derm Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Chanoki M, Isukos S, Suzuki S, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of the scalp. Cutis. 1989;43:143-144.

- Sáez Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Martin M, Carnerero A, et al. Naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the nose. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:751-752.

- Hassab-El-Naby HMM, Rageh MA. Adult-onset nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis mimicking plane xanthoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:10-11.

- Park HJ, Park CJ, Yi JY, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the face. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:435-437.

- Ioannidou DJ, Stefanidou MP, Panayiotides JG, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (Hoffman-Zurhelle) with localized scleroderma like appearance. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:54-57.

- Nogita T, Wong TY, Hidano A, et al. Pedunculated lipofibroma. a clinicopathologic study of thirty-two cases supporting a simplified nomenclature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):235-240.

- Sawada Y. Solitary nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the forehead. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;16:356-358.

- Knoth W. Uber Naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis Hoffmann-Zurhelle und uber Naevus naevocellularis partim lipomatodes. Dermatologica. 1962;125:161.

- Weitzner S. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:540-542.

- Kaw P, Carlson A, Meyer DR. Nevus lipomatosus (pedunculated lipofibroma) of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:74-76.

- Vano-Galvan S, Moreno C, Vano-Galvan E, et al. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the sole. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:353-354.

- Adotama P, Hutson SD, Rieder EA, et al. Revisiting solitary pedunculated lipofibromas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:954-957.

- Kubin ME, Lantto U, Lindgren O, et al. A rare, recurrent spindle cell lipoma of the nose. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00571.

- Jung SN, Shin JW, Kwon H, et al. Fibrolipoma of the tip of the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:555-556.