User login

A Nationwide Survey of Dermatology Faculty and Mentors on Their Advice for the Dermatology Match Process

A Nationwide Survey of Dermatology Faculty and Mentors on Their Advice for the Dermatology Match Process

While strong relationships with mentors and advisers are critical to navigating the competitive dermatology match process, the advice medical students receive from different individuals can be contradictory. Unaccredited information online—particularly on social media—as well as data reported by applicants can add to potential confusion.1 Published research has elicited comments and observations from successfully matched medical students about highly discussed topics such as presentations and publications, letters of recommendation, away rotations, and interviews.2,3 However, there currently are no published data about advice that dermatology mentors actually offer medical students. In this study, we aimed to investigate this gap in the current literature and examine the advice dermatology faculty, program directors, and other mentors at institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education across the United States give to medical students applying to dermatology residency.

Methods

A 14-question Johns Hopkins Qualtrics survey was sent via the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) listserve in June 2024 soliciting responses from members who consider themselves to be mentors to dermatology applicants across the United States. The survey included multiple-choice questions with the option to select multiple answers and a space for open-ended responses. The questions first gathered information on the respondents, including the capacity in which the mentors advised medical students (eg, program director, department chair, clinical faculty). Mentors were asked for the number of years they had been advising mentees and if they were advising students with a home dermatology program. In addition, mentors were asked what advice they give their mentees about aspects of the application process, including gap years, dual applications, research involvement, couples matching, program signaling, away rotations, internship year, letters of recommendation, geographic signaling, interviewing advice, and volunteering during medical school.

On August 18, 2024, survey results from 115 respondents were aggregated. The responses for each question were quantitatively assessed to determine whether there was consensus on specific advice offered. The open-ended responses also were qualitatively assessed to determine the most common responses.

Results

The respondents included program directors (30% [35/115]), clinical faculty (22% [25/115]), department chairs (18% [21/115]), assistant program directors (15% [17/115]), medical school clerkship directors (8% [9/115]), primary mentors (ie, faculty who did not fall into any of the aforementioned categories but still advised medical students interested in dermatology)(5% [6/115]), division chiefs (1% [1/115]), and deans (1% [1/115]). Respondents had been advising students for a median of 10 years (range, 1-40 years [25th percentile, 5.00 years; 75th percentile, 13.75 years]). The majority (90% [103/115]) of mentors surveyed were advising students with a home dermatology program.

Areas of Consensus

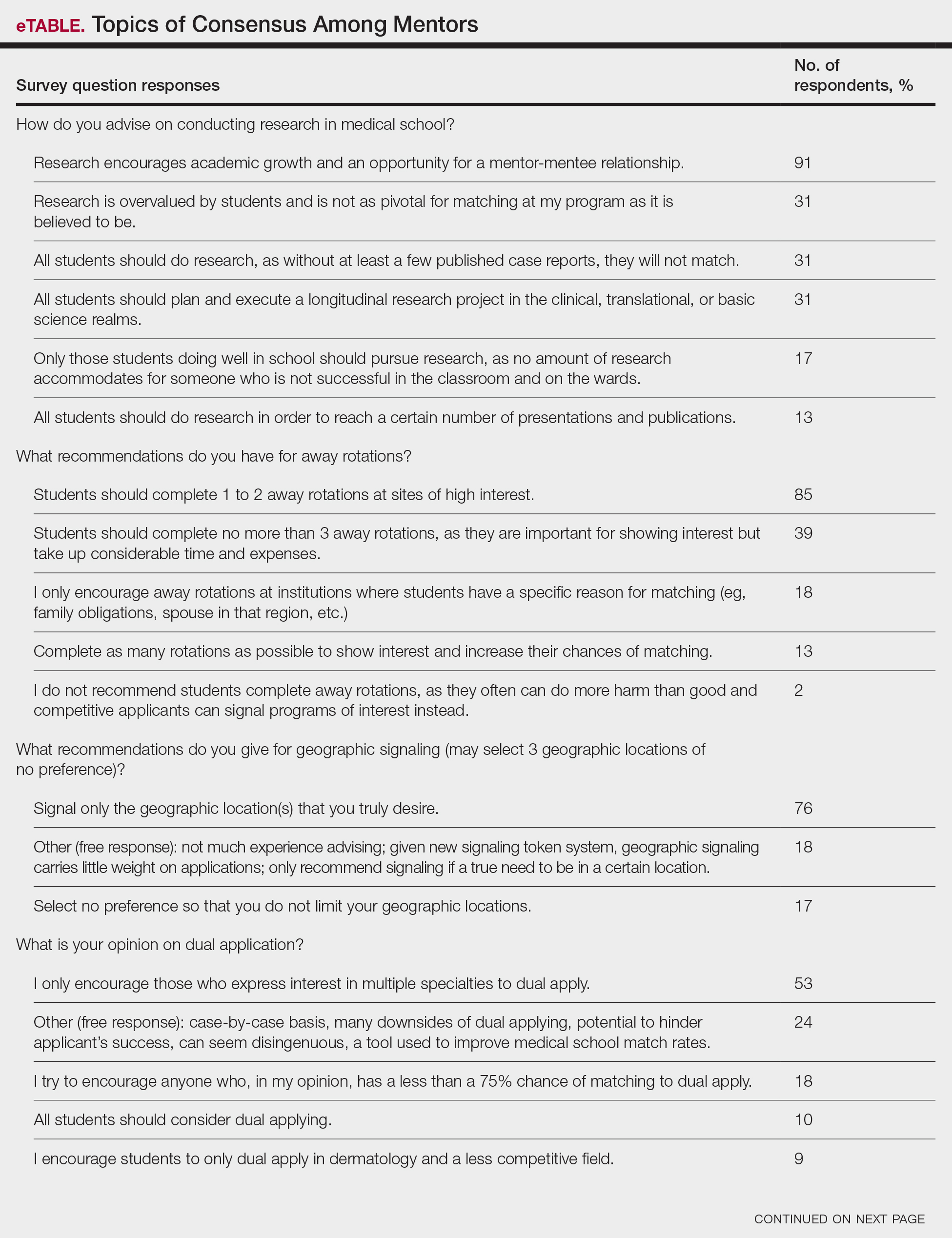

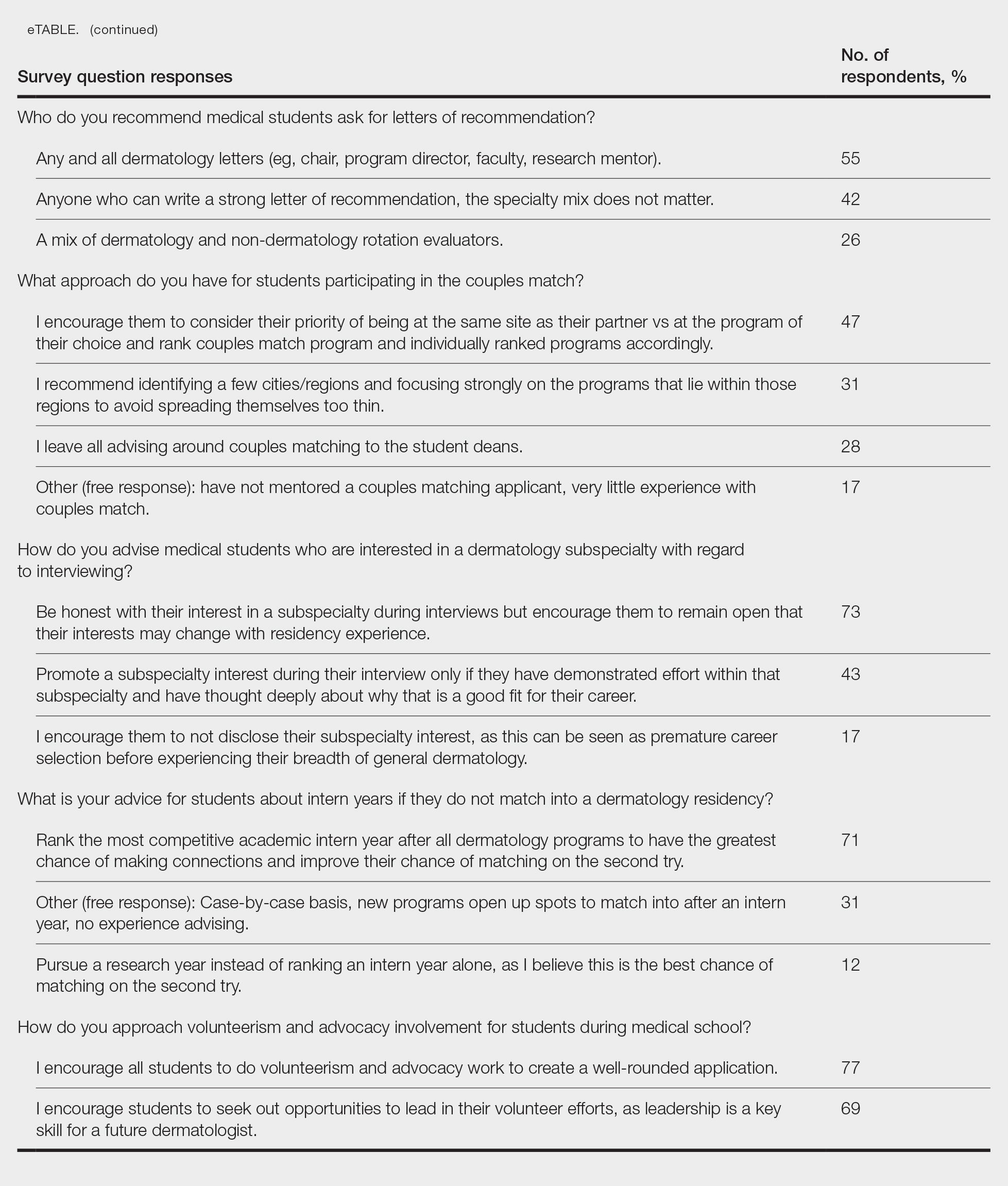

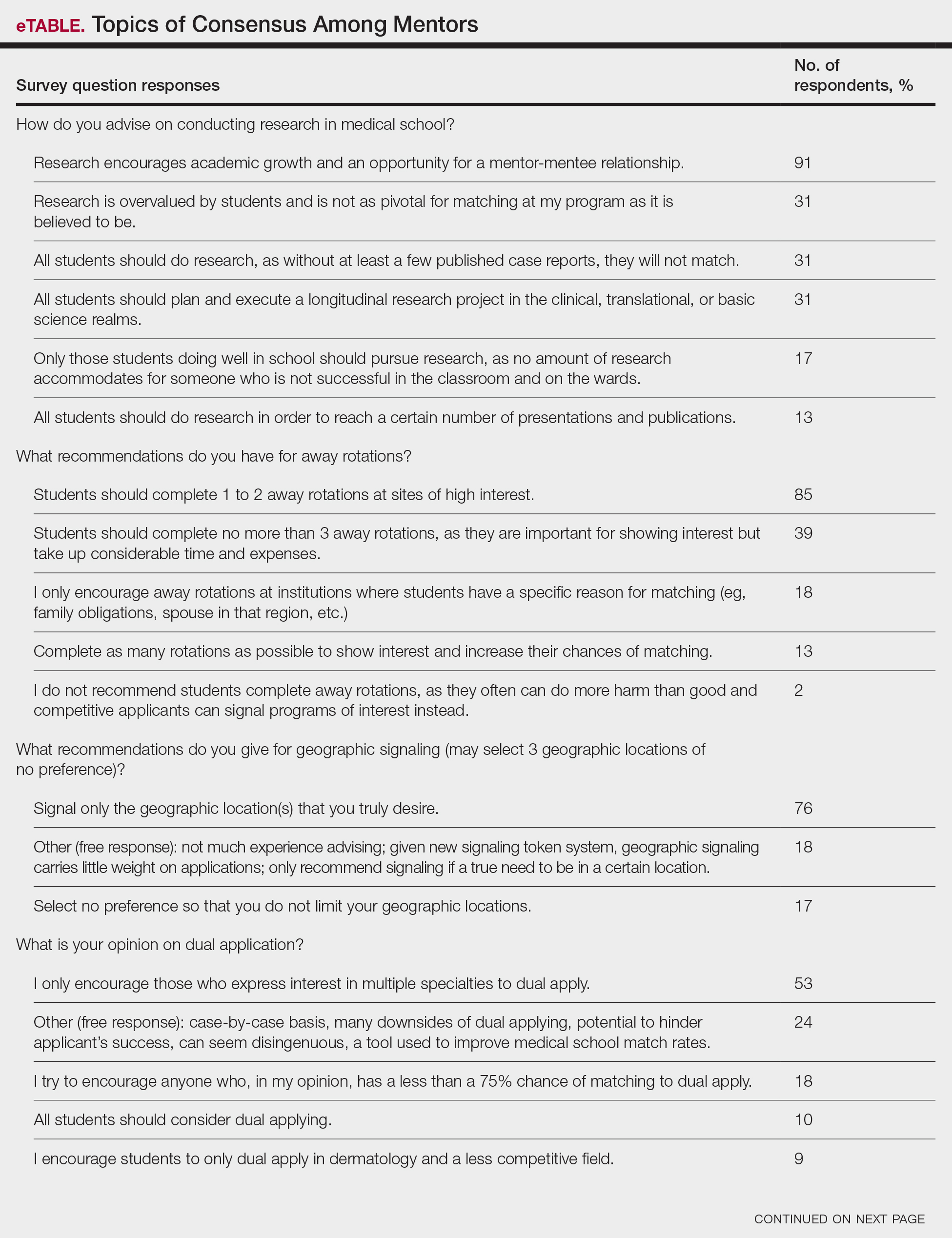

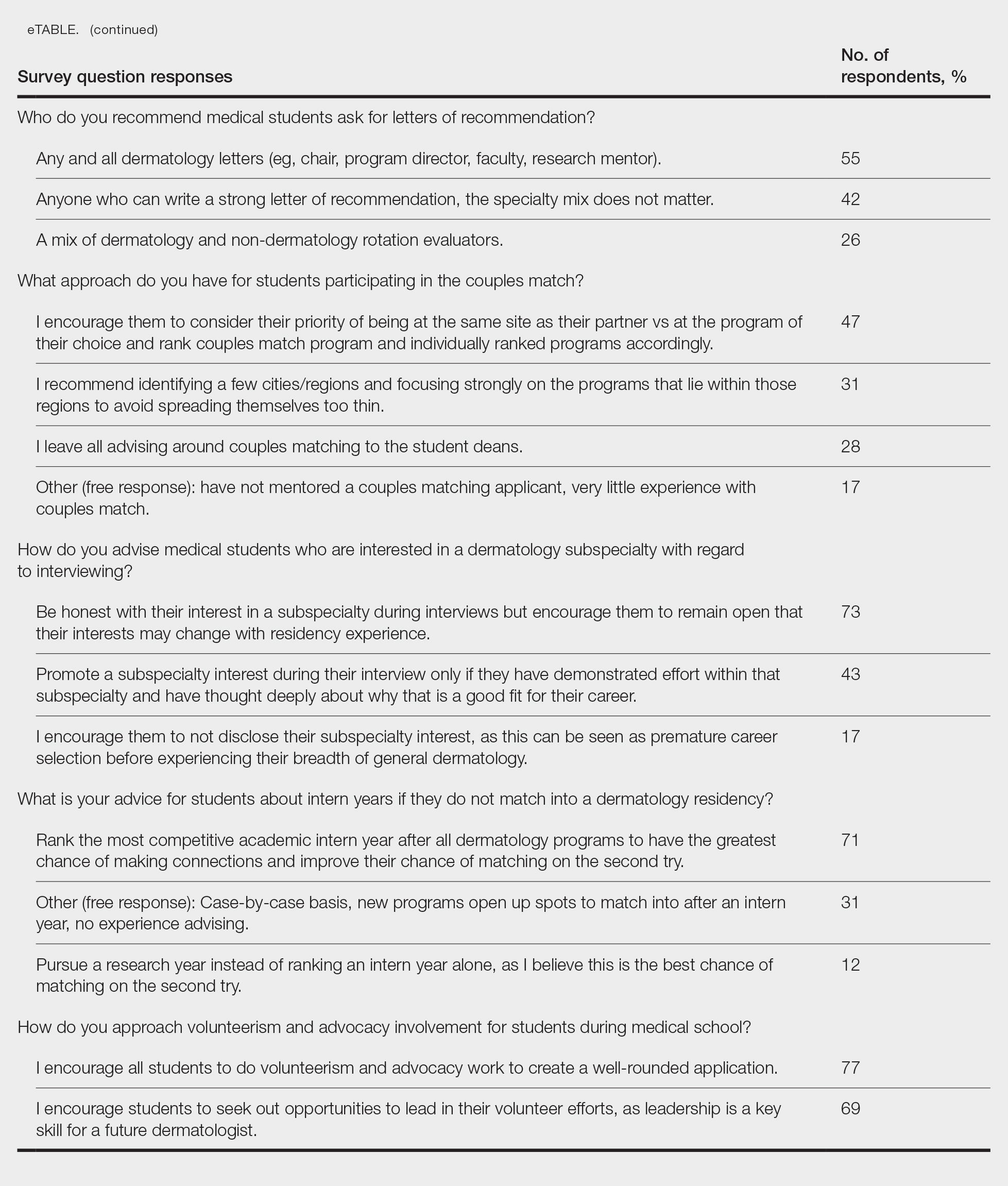

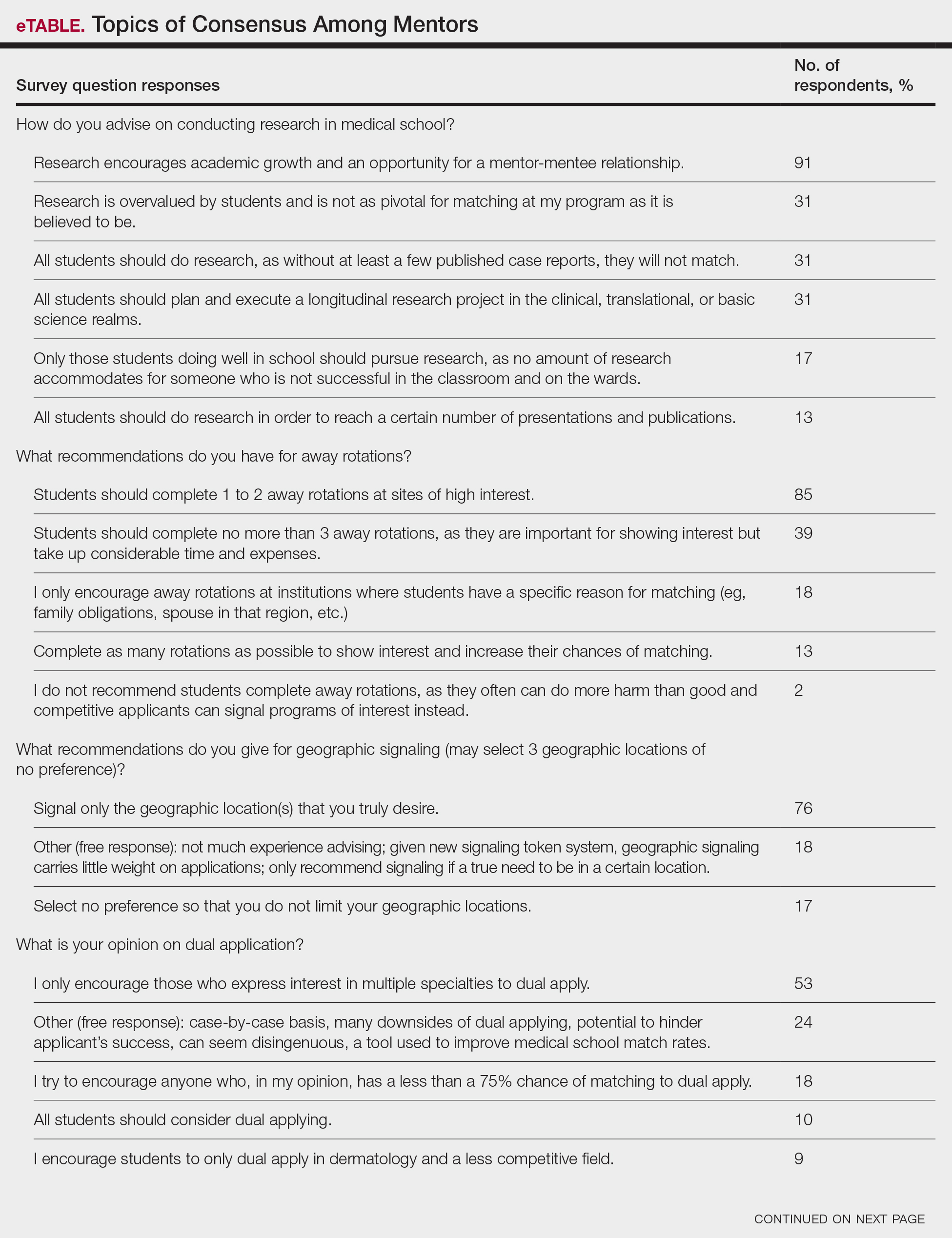

In some areas, there was broad consensus among the advice offered by the mentors that were surveyed (eTable).

Research During Medical School—More than 91% (105/115) of the respondents recommended research to encourage academic growth and indicated that the most important reason for conducting research during medical school is to foster mentor-mentee relationships; however, more than one-third of respondents believed research is overvalued by students and research productivity is not as critical for matching as they perceive it to be. When these responses were categorized by respondent positions, 29% (15/52) of program or assistant directors indicated agreement with the statement that research is overvalued.

Away Rotations—There also was a consensus about the importance of away rotations, with 85% (98/115) of respondents advising students to complete 1 to 2 away rotations at sites of high interest, and 13% (15/115) suggesting that students complete as many away rotations as possible. It is worth noting, however, that the official APD Residency Program Directors Section’s statement on away rotations recommends no more than 2 away rotations (or no more than 3 for students with no home program).4

Reapplication Advice—Additionally, in a situation where students do not match into a dermatology residency program, the vast majority (71% [82/115]) of respondents advised students to rank competitive intern years to foster connections and improve the chance of matching on the second attempt.

Volunteering During Medical School—Seventy-seven percent (89/115) of mentors encouraged students to engage in volunteerism and advocacy during medical school to create a well-rounded application, and 69% (79/115) of mentors encouraged students to display leadership in their volunteer efforts.

Areas Without Consensus

Letters of Recommendation—Most respondents recommended submitting letters of recommendation only from dermatology professionals (55% [63/115]), with the remainder recommending students request a letter from anyone who could provide a strong recommendation regardless of specialty mix (42% [48/115]).

Dermatologic Subspecialties—For students interested in dermatologic subspecialties, 73% (84/115) of mentors advised that students be honest during interviews but keep an open mind that interests during residencies may change. Forty-three percent (49/115) of respondents encouraged students to promote a subspecialty interest during their interview only if they can demonstrate effort within that subspecialty on their application.

Couples Matching—Most respondents approach couples matching on a case-by-case basis and assess individual priorities when they do advise on this topic. Respondents often advise applicants to identify a few cities/regions and focus strongly on the programs within those regions to avoid spreading themselves too thin; however, one-third (38/115) of respondents indicated that they do not personally offer advice regarding the couples match.

Areas With Diverse Opinions

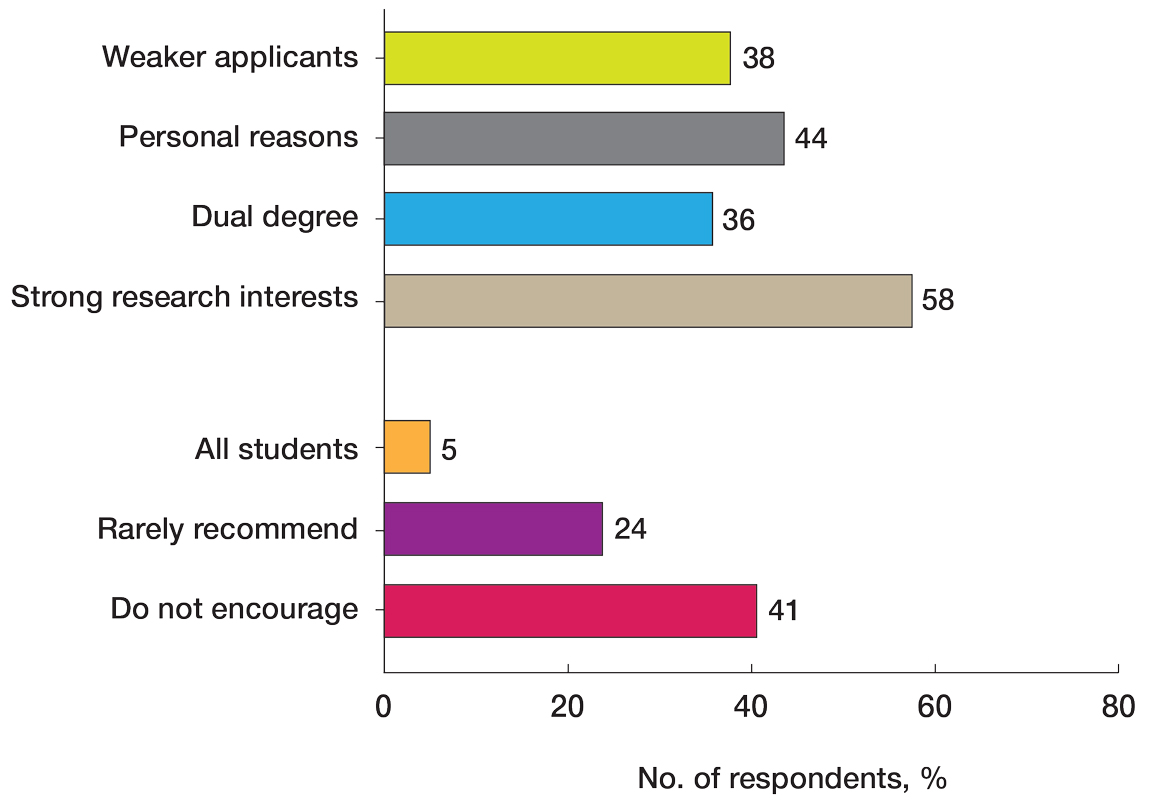

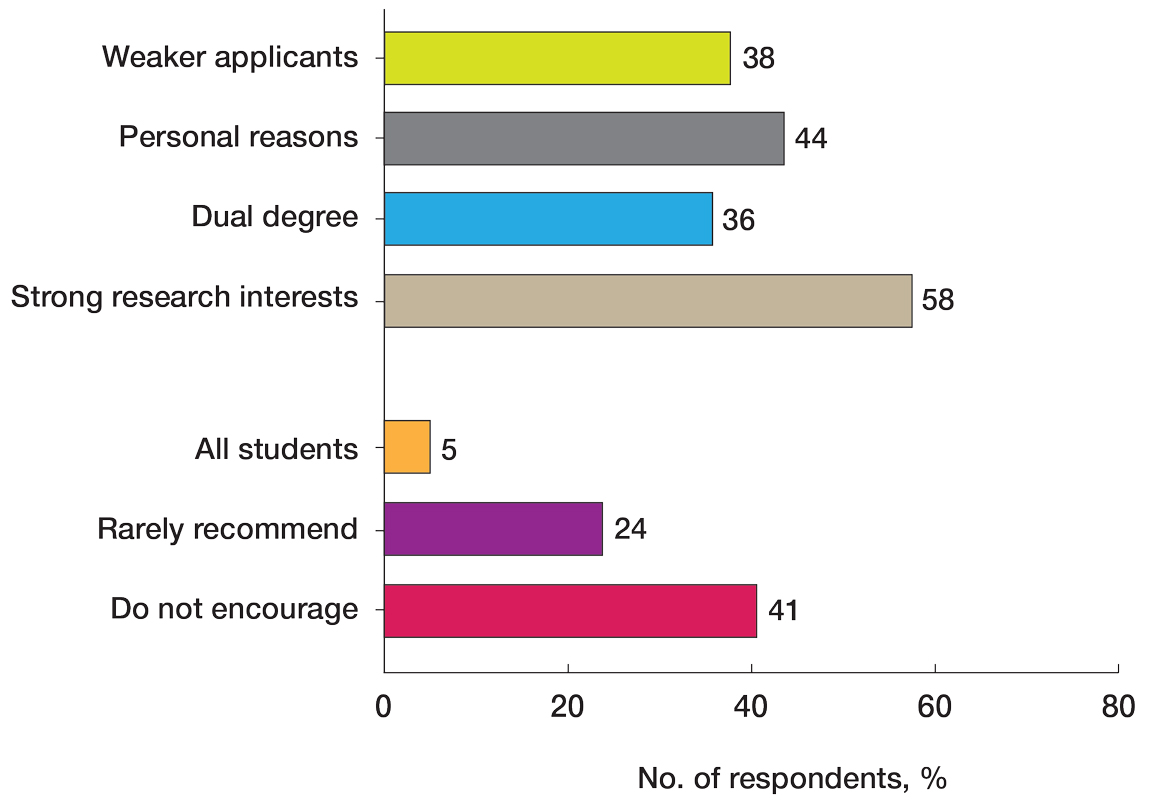

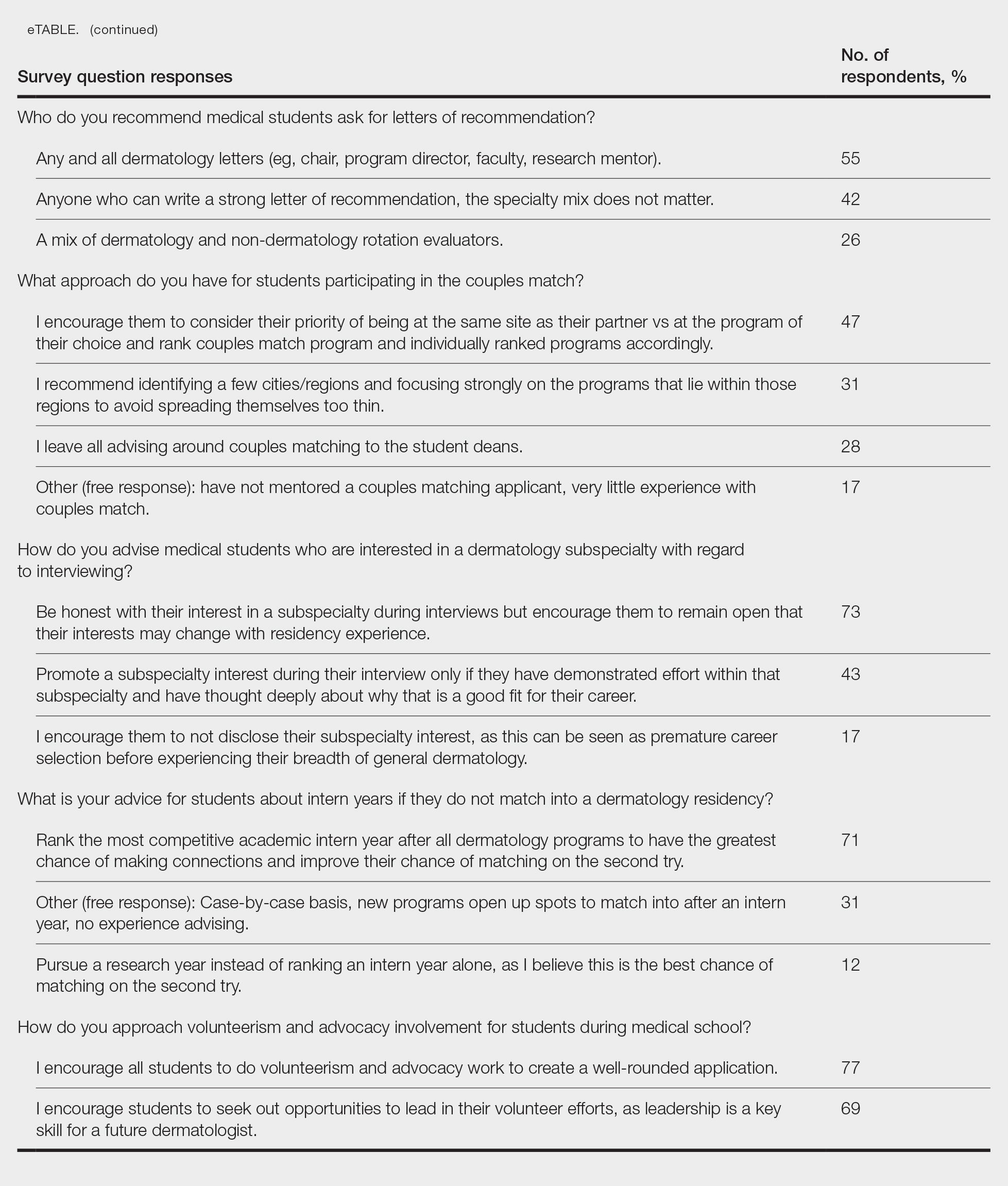

Gap Years—Nearly one-quarter (24% [28/115]) of mentors reported that they rarely recommend students take a year off and only support those who are adamant about doing so, or that they never support taking a gap year at all. A slight majority (58% [67/115]) recommend a gap year for students strongly interested in dermatologic research, and 38% (44/115) recommend a gap year for students with weaker applications (Figure 1). We received many open-ended responses to this question, with mentors frequently indicating that they advise students to take a gap year on a case-by-case basis, with 44% (51/115) of commenters recommending that students only take paid gap-year research positions.

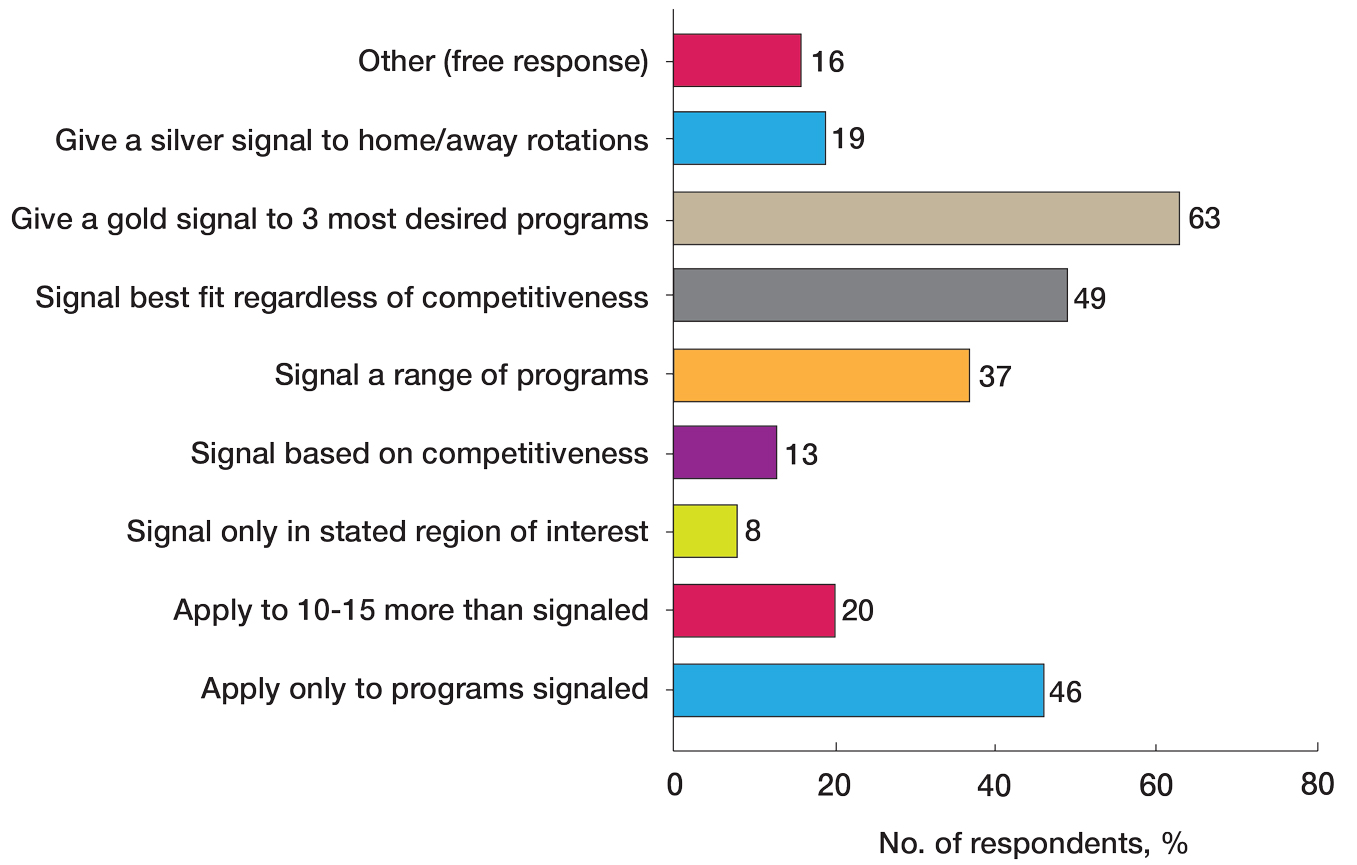

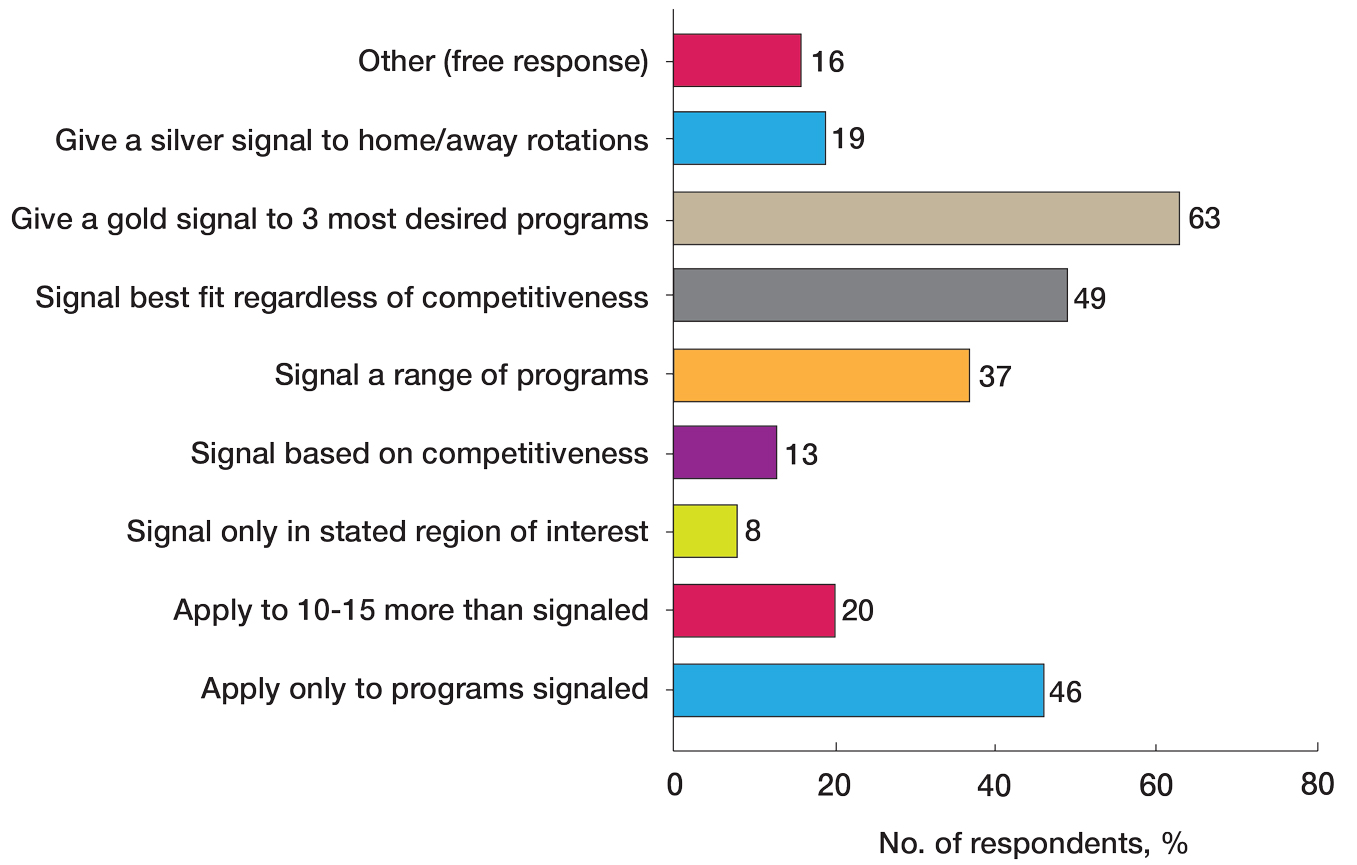

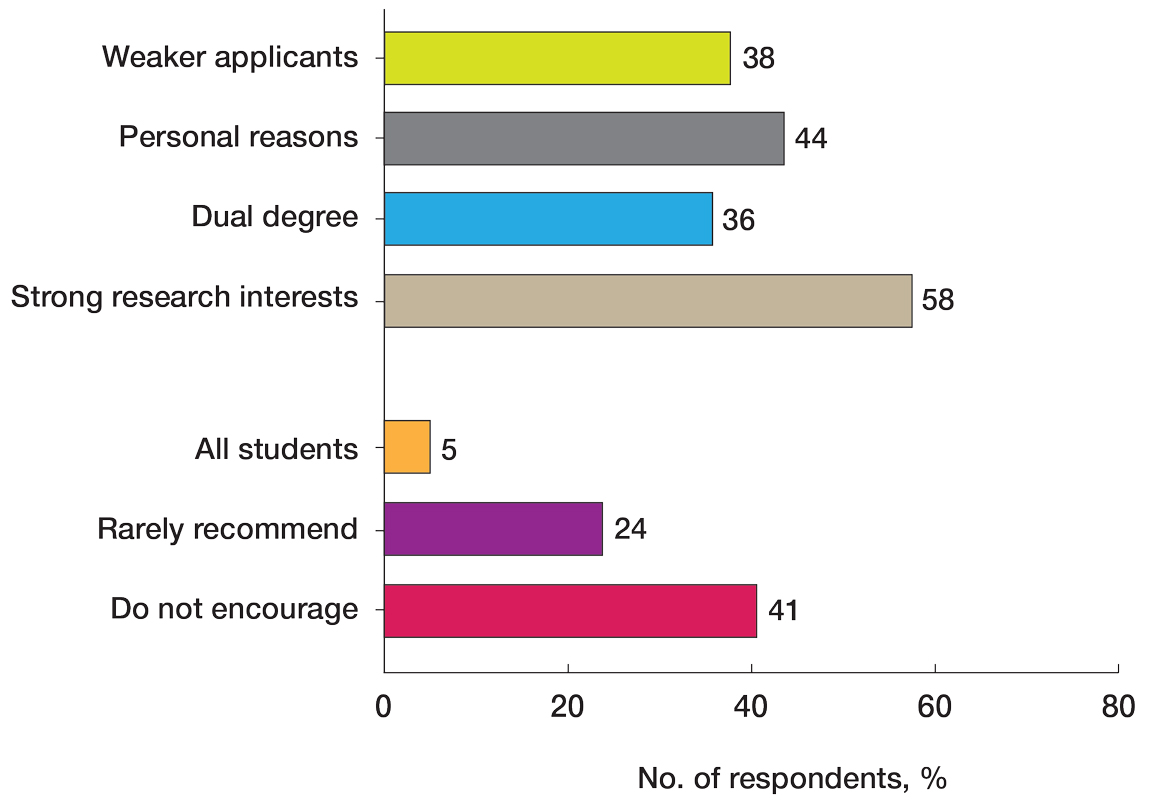

Program Signaling—The dermatology residency application process implemented a system of preference signaling tokens (PSTs) starting with the 2021-2022 cycle. Not quite half (46% [53/115]) of respondents recommend students apply only to places that they signaled, while 20% (23/115) advise responding to 10 to 15 additional programs. Very few (8% [9/115]) advise students to signal only in their stated region of interest. Approximately half (49% [56/115]) of mentors recommend students only signal based on the programs they feel would be the best fit for them without regard for perceived competitiveness—which aligns with the APD Residency Program Directors Section’s recommendation4—while 37% (43/115) recommend students distribute their signals to a wide range of programs. Sixty-three percent (72/115) of respondents recommend gold signaling to the student’s 3 most desired programs regardless of home and away rotation considerations, while 19% (22/115) recommend students give silver signals to their home and away rotation programs, as a rotation is already a signal of a strong desire to be there (Figure 2).

Dual Application—Fifty-three percent (61/115) of mentors recommended dual applying only for those truly interested in multiple specialties. Eighteen percent (21/115) of respondents advised dual applying for those with less than a 75% chance of matching. Twenty-five percent (29/115) of respondents free-wrote comments about approaching dual applying on a case-by-case basis, with many discussing the downsides of dual application and raising concerns that dual applications can hinder applicants’ success, can seem disingenuous, and seem to be a tool used to improve medical school match rates without benefit for the student.

We also stratified the data to compare overall responses from the total cohort with those from only program and assistant program directors. Across the 14 questions, responses from program and assistant program directors alone were similar to the overall cohort results

Comment

This study evaluated nationwide data on mentorship advising in dermatology, detailing mentors’ advice regarding research, gap years, dual applications, away rotations, intern year, couples matching, program signaling, and volunteering during medical school. Based on our results, most respondents agree on the importance of research during medical school, the utility of away rotations, and the value of volunteering during medical school. Similarly, respondents agreed on the importance of having strong letters of recommendation; while some advised asking only dermatology faculty to write letters, others did not have a specialty preference for the letter writers. Respondents also had varying views about sharing interest in subspecialties during residency interviews. Many of the respondents do not provide recommendations regarding geographic signaling and couples matching, expressing that these are parts of an application that are important to approach on a case-by-case basis. Lastly, respondents had diverse opinions regarding the utility of gap years, whether to encourage or discourage dual applications, and how to advise regarding program signaling.

Our results also showed that one-third of respondents believed that research is not as important as it is perceived to be by dermatology applicants. While engaging in research during medical school was almost unanimously encouraged to foster mentor-mentee relationships, respondents expressed that the number of research experiences and publications was not critical. This is an important topic of discussion, as taking a dedicated year away from medical school to complete a research fellowship is becoming a trend among dermatology applicants.5 There has been discussion both on unofficial online platforms as well as in the published literature regarding the pressure for medical students interested in dermatology to publish, which may result in a gap year for research.6 The literature on the utility of a gap year in match rates is sparse, with one study showing no difference in match rates among Mayo Clinic dermatology residents who took research years vs those who did not.7 However, this contrasts with match rates at top dermatology residency programs where 41% of applicants who took a gap year matched vs 19% who did not.7,8 These conflicting data are reflected in our study results, with respondents expressing different opinions on the utility of gap years.

There also are important equity concerns regarding the role of research years in the dermatology residency match process. Dermatology is one of the least racially diverse specialties, although there have been efforts to increase representation among residents and attending physicians.9-11 Research years can be important contributors to this lack of representation, as these often are unpaid and can discourage economically disadvantaged students from applying.9-11 Additionally, applicants may not have the flexibility to defer future salary for a year to match into dermatology; therefore, mentors should offer multiple options to individual applicants instead of solely encouraging gap years, given the conflicting feelings regarding their productivity.

Another topic of disagreement was dual application. Approximately one-third of respondents said they encourage either all students or those with less than a 75% chance of matching to dual apply, while about half only encourage students who are truly interested in multiple specialties to do so. Additionally, a large subset of respondents said they do not encourage dual applications due to concerns that they make applicants a worse candidate for each specialty and overall have negative effects on matching. Twenty-five percent of respondents opted to leave an open-ended response to this question: some offered the perspective that, if applicants feel a need to dual apply due to a weaker application, they do not advise the applicant to apply to dermatology. Many open ended responses underscored that the respondent does not encourage dual applications because they are inherently more time consuming, could hinder the applicant’s success, can seem disingenuous, and are a tool used to improve medical school match rates without being beneficial for the student. Some respondents also favored reapplying to dermatology the following year instead of dual applying. Finally, a subset of mentors indicated that they approach dual applications on a case-by-case basis, and others reported they do not have much experience advising on this topic. Currently, there are no known data in the literature on the efficacy and utility of dual applications in the dermatology match process; therefore, our study provides valuable insight for applicants interested in the impacts of the dual application. Overall, students should approach this option with mentors on an individual basis but ultimately should be aware of the concerns and mixed perceptions of the dual application process.

With regard to program signaling, previous research has shown that PSTs have a large impact on the chance of being granted an interview.12 In our study, we provide a comprehensive overview of advising regarding these signals. While mentors often responded that they did not have much experience advising in this domain—and it is too soon to tell the impact of this program signaling—many offered differing opinions. Many said they recommend that students give a gold signal to their 3 most desired programs regardless of home and away rotations and perceived competitiveness, which follows the guidelines issued by the APD; however, 19% recommend only giving silver signals to home and away rotation programs, as participation in those programs is considered a sufficient signal of interest. Additionally, about half of mentors recommended that students only apply where they signal, whereas 20% recommended applying to 10 to 15 programs beyond those signaled. Future studies should investigate the impact of PSTs on interview invitations once sufficient application cycles have occurred.

Study Limitations

This study was conducted via email to the APD listserve. The total number of faculty on this listserve is unknown; therefore, we do not know the total response rate of the survey. Additionally, we surveyed mentors in this listserve, who therefore receive more emails and overall correspondence about the dermatology match and may be more involved in these conversations. The mentors who responded to our survey may have a different approach and response to our various survey questions than a given mentor across the United States who did not respond to this survey. A final limitation of our study is that the survey responses a mentor gives may not fully match the advice that they give their students privately.

Conclusion

Our survey of dermatology mentors across the United States provides valuable insight into how mentors advise for a strong dermatology residency application. Mentors agreed on the importance of research during medical school, away rotations, strong letters of recommendation, and volunteerism and advocacy to promote a strong residency application. Important topics of disagreement include the decision for dermatology applicants to take a dedicated gap year in medical school, how to use tokens/signals effectively, and the dual application process. Our findings also underscore important application components that applicants and mentors should approach on an individual basis. Future studies should investigate the impact of signals/tokens on the match process as well as the utility of gap years and dual applications, working to standardize the advice applicants receive.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt4604h1w4.

- Kolli SS, Feldman SR, Huang WW. The dermatology residency application process. Dermatol Online J. 2021;26:13030/qt4k1570vj.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.303

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section Information Regarding the 2023-2024 Application Cycle. Published 2023. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/12386/download

- Alikhan A, Sivamani RK, Mutizwa MM, et al. Advice for medical students interested in dermatology: perspectives from fourth year students who matched. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:4.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230. doi:10.1111/ijd.15964

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wassef C, et al. The importance of mentorship during research gap years for the dermatology residency match. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E209-E210. doi:10.1111/ijd.16084

- Zheng DX, Gallo Marin B, Mulligan KM, et al. Inequity concerns surrounding research years and the dermatology residency match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:E247-E248. doi:10.1111/ijd.16179

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Cordova A, et al. Challenging the status quo: increasing diversity in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E421. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.185

- Dirr MA, Brownstone N, Zakria D, et al. Dermatology match preference signaling tokens: impact and implications. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1367-1368. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003645

While strong relationships with mentors and advisers are critical to navigating the competitive dermatology match process, the advice medical students receive from different individuals can be contradictory. Unaccredited information online—particularly on social media—as well as data reported by applicants can add to potential confusion.1 Published research has elicited comments and observations from successfully matched medical students about highly discussed topics such as presentations and publications, letters of recommendation, away rotations, and interviews.2,3 However, there currently are no published data about advice that dermatology mentors actually offer medical students. In this study, we aimed to investigate this gap in the current literature and examine the advice dermatology faculty, program directors, and other mentors at institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education across the United States give to medical students applying to dermatology residency.

Methods

A 14-question Johns Hopkins Qualtrics survey was sent via the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) listserve in June 2024 soliciting responses from members who consider themselves to be mentors to dermatology applicants across the United States. The survey included multiple-choice questions with the option to select multiple answers and a space for open-ended responses. The questions first gathered information on the respondents, including the capacity in which the mentors advised medical students (eg, program director, department chair, clinical faculty). Mentors were asked for the number of years they had been advising mentees and if they were advising students with a home dermatology program. In addition, mentors were asked what advice they give their mentees about aspects of the application process, including gap years, dual applications, research involvement, couples matching, program signaling, away rotations, internship year, letters of recommendation, geographic signaling, interviewing advice, and volunteering during medical school.

On August 18, 2024, survey results from 115 respondents were aggregated. The responses for each question were quantitatively assessed to determine whether there was consensus on specific advice offered. The open-ended responses also were qualitatively assessed to determine the most common responses.

Results

The respondents included program directors (30% [35/115]), clinical faculty (22% [25/115]), department chairs (18% [21/115]), assistant program directors (15% [17/115]), medical school clerkship directors (8% [9/115]), primary mentors (ie, faculty who did not fall into any of the aforementioned categories but still advised medical students interested in dermatology)(5% [6/115]), division chiefs (1% [1/115]), and deans (1% [1/115]). Respondents had been advising students for a median of 10 years (range, 1-40 years [25th percentile, 5.00 years; 75th percentile, 13.75 years]). The majority (90% [103/115]) of mentors surveyed were advising students with a home dermatology program.

Areas of Consensus

In some areas, there was broad consensus among the advice offered by the mentors that were surveyed (eTable).

Research During Medical School—More than 91% (105/115) of the respondents recommended research to encourage academic growth and indicated that the most important reason for conducting research during medical school is to foster mentor-mentee relationships; however, more than one-third of respondents believed research is overvalued by students and research productivity is not as critical for matching as they perceive it to be. When these responses were categorized by respondent positions, 29% (15/52) of program or assistant directors indicated agreement with the statement that research is overvalued.

Away Rotations—There also was a consensus about the importance of away rotations, with 85% (98/115) of respondents advising students to complete 1 to 2 away rotations at sites of high interest, and 13% (15/115) suggesting that students complete as many away rotations as possible. It is worth noting, however, that the official APD Residency Program Directors Section’s statement on away rotations recommends no more than 2 away rotations (or no more than 3 for students with no home program).4

Reapplication Advice—Additionally, in a situation where students do not match into a dermatology residency program, the vast majority (71% [82/115]) of respondents advised students to rank competitive intern years to foster connections and improve the chance of matching on the second attempt.

Volunteering During Medical School—Seventy-seven percent (89/115) of mentors encouraged students to engage in volunteerism and advocacy during medical school to create a well-rounded application, and 69% (79/115) of mentors encouraged students to display leadership in their volunteer efforts.

Areas Without Consensus

Letters of Recommendation—Most respondents recommended submitting letters of recommendation only from dermatology professionals (55% [63/115]), with the remainder recommending students request a letter from anyone who could provide a strong recommendation regardless of specialty mix (42% [48/115]).

Dermatologic Subspecialties—For students interested in dermatologic subspecialties, 73% (84/115) of mentors advised that students be honest during interviews but keep an open mind that interests during residencies may change. Forty-three percent (49/115) of respondents encouraged students to promote a subspecialty interest during their interview only if they can demonstrate effort within that subspecialty on their application.

Couples Matching—Most respondents approach couples matching on a case-by-case basis and assess individual priorities when they do advise on this topic. Respondents often advise applicants to identify a few cities/regions and focus strongly on the programs within those regions to avoid spreading themselves too thin; however, one-third (38/115) of respondents indicated that they do not personally offer advice regarding the couples match.

Areas With Diverse Opinions

Gap Years—Nearly one-quarter (24% [28/115]) of mentors reported that they rarely recommend students take a year off and only support those who are adamant about doing so, or that they never support taking a gap year at all. A slight majority (58% [67/115]) recommend a gap year for students strongly interested in dermatologic research, and 38% (44/115) recommend a gap year for students with weaker applications (Figure 1). We received many open-ended responses to this question, with mentors frequently indicating that they advise students to take a gap year on a case-by-case basis, with 44% (51/115) of commenters recommending that students only take paid gap-year research positions.

Program Signaling—The dermatology residency application process implemented a system of preference signaling tokens (PSTs) starting with the 2021-2022 cycle. Not quite half (46% [53/115]) of respondents recommend students apply only to places that they signaled, while 20% (23/115) advise responding to 10 to 15 additional programs. Very few (8% [9/115]) advise students to signal only in their stated region of interest. Approximately half (49% [56/115]) of mentors recommend students only signal based on the programs they feel would be the best fit for them without regard for perceived competitiveness—which aligns with the APD Residency Program Directors Section’s recommendation4—while 37% (43/115) recommend students distribute their signals to a wide range of programs. Sixty-three percent (72/115) of respondents recommend gold signaling to the student’s 3 most desired programs regardless of home and away rotation considerations, while 19% (22/115) recommend students give silver signals to their home and away rotation programs, as a rotation is already a signal of a strong desire to be there (Figure 2).

Dual Application—Fifty-three percent (61/115) of mentors recommended dual applying only for those truly interested in multiple specialties. Eighteen percent (21/115) of respondents advised dual applying for those with less than a 75% chance of matching. Twenty-five percent (29/115) of respondents free-wrote comments about approaching dual applying on a case-by-case basis, with many discussing the downsides of dual application and raising concerns that dual applications can hinder applicants’ success, can seem disingenuous, and seem to be a tool used to improve medical school match rates without benefit for the student.

We also stratified the data to compare overall responses from the total cohort with those from only program and assistant program directors. Across the 14 questions, responses from program and assistant program directors alone were similar to the overall cohort results

Comment

This study evaluated nationwide data on mentorship advising in dermatology, detailing mentors’ advice regarding research, gap years, dual applications, away rotations, intern year, couples matching, program signaling, and volunteering during medical school. Based on our results, most respondents agree on the importance of research during medical school, the utility of away rotations, and the value of volunteering during medical school. Similarly, respondents agreed on the importance of having strong letters of recommendation; while some advised asking only dermatology faculty to write letters, others did not have a specialty preference for the letter writers. Respondents also had varying views about sharing interest in subspecialties during residency interviews. Many of the respondents do not provide recommendations regarding geographic signaling and couples matching, expressing that these are parts of an application that are important to approach on a case-by-case basis. Lastly, respondents had diverse opinions regarding the utility of gap years, whether to encourage or discourage dual applications, and how to advise regarding program signaling.

Our results also showed that one-third of respondents believed that research is not as important as it is perceived to be by dermatology applicants. While engaging in research during medical school was almost unanimously encouraged to foster mentor-mentee relationships, respondents expressed that the number of research experiences and publications was not critical. This is an important topic of discussion, as taking a dedicated year away from medical school to complete a research fellowship is becoming a trend among dermatology applicants.5 There has been discussion both on unofficial online platforms as well as in the published literature regarding the pressure for medical students interested in dermatology to publish, which may result in a gap year for research.6 The literature on the utility of a gap year in match rates is sparse, with one study showing no difference in match rates among Mayo Clinic dermatology residents who took research years vs those who did not.7 However, this contrasts with match rates at top dermatology residency programs where 41% of applicants who took a gap year matched vs 19% who did not.7,8 These conflicting data are reflected in our study results, with respondents expressing different opinions on the utility of gap years.

There also are important equity concerns regarding the role of research years in the dermatology residency match process. Dermatology is one of the least racially diverse specialties, although there have been efforts to increase representation among residents and attending physicians.9-11 Research years can be important contributors to this lack of representation, as these often are unpaid and can discourage economically disadvantaged students from applying.9-11 Additionally, applicants may not have the flexibility to defer future salary for a year to match into dermatology; therefore, mentors should offer multiple options to individual applicants instead of solely encouraging gap years, given the conflicting feelings regarding their productivity.

Another topic of disagreement was dual application. Approximately one-third of respondents said they encourage either all students or those with less than a 75% chance of matching to dual apply, while about half only encourage students who are truly interested in multiple specialties to do so. Additionally, a large subset of respondents said they do not encourage dual applications due to concerns that they make applicants a worse candidate for each specialty and overall have negative effects on matching. Twenty-five percent of respondents opted to leave an open-ended response to this question: some offered the perspective that, if applicants feel a need to dual apply due to a weaker application, they do not advise the applicant to apply to dermatology. Many open ended responses underscored that the respondent does not encourage dual applications because they are inherently more time consuming, could hinder the applicant’s success, can seem disingenuous, and are a tool used to improve medical school match rates without being beneficial for the student. Some respondents also favored reapplying to dermatology the following year instead of dual applying. Finally, a subset of mentors indicated that they approach dual applications on a case-by-case basis, and others reported they do not have much experience advising on this topic. Currently, there are no known data in the literature on the efficacy and utility of dual applications in the dermatology match process; therefore, our study provides valuable insight for applicants interested in the impacts of the dual application. Overall, students should approach this option with mentors on an individual basis but ultimately should be aware of the concerns and mixed perceptions of the dual application process.

With regard to program signaling, previous research has shown that PSTs have a large impact on the chance of being granted an interview.12 In our study, we provide a comprehensive overview of advising regarding these signals. While mentors often responded that they did not have much experience advising in this domain—and it is too soon to tell the impact of this program signaling—many offered differing opinions. Many said they recommend that students give a gold signal to their 3 most desired programs regardless of home and away rotations and perceived competitiveness, which follows the guidelines issued by the APD; however, 19% recommend only giving silver signals to home and away rotation programs, as participation in those programs is considered a sufficient signal of interest. Additionally, about half of mentors recommended that students only apply where they signal, whereas 20% recommended applying to 10 to 15 programs beyond those signaled. Future studies should investigate the impact of PSTs on interview invitations once sufficient application cycles have occurred.

Study Limitations

This study was conducted via email to the APD listserve. The total number of faculty on this listserve is unknown; therefore, we do not know the total response rate of the survey. Additionally, we surveyed mentors in this listserve, who therefore receive more emails and overall correspondence about the dermatology match and may be more involved in these conversations. The mentors who responded to our survey may have a different approach and response to our various survey questions than a given mentor across the United States who did not respond to this survey. A final limitation of our study is that the survey responses a mentor gives may not fully match the advice that they give their students privately.

Conclusion

Our survey of dermatology mentors across the United States provides valuable insight into how mentors advise for a strong dermatology residency application. Mentors agreed on the importance of research during medical school, away rotations, strong letters of recommendation, and volunteerism and advocacy to promote a strong residency application. Important topics of disagreement include the decision for dermatology applicants to take a dedicated gap year in medical school, how to use tokens/signals effectively, and the dual application process. Our findings also underscore important application components that applicants and mentors should approach on an individual basis. Future studies should investigate the impact of signals/tokens on the match process as well as the utility of gap years and dual applications, working to standardize the advice applicants receive.

While strong relationships with mentors and advisers are critical to navigating the competitive dermatology match process, the advice medical students receive from different individuals can be contradictory. Unaccredited information online—particularly on social media—as well as data reported by applicants can add to potential confusion.1 Published research has elicited comments and observations from successfully matched medical students about highly discussed topics such as presentations and publications, letters of recommendation, away rotations, and interviews.2,3 However, there currently are no published data about advice that dermatology mentors actually offer medical students. In this study, we aimed to investigate this gap in the current literature and examine the advice dermatology faculty, program directors, and other mentors at institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education across the United States give to medical students applying to dermatology residency.

Methods

A 14-question Johns Hopkins Qualtrics survey was sent via the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) listserve in June 2024 soliciting responses from members who consider themselves to be mentors to dermatology applicants across the United States. The survey included multiple-choice questions with the option to select multiple answers and a space for open-ended responses. The questions first gathered information on the respondents, including the capacity in which the mentors advised medical students (eg, program director, department chair, clinical faculty). Mentors were asked for the number of years they had been advising mentees and if they were advising students with a home dermatology program. In addition, mentors were asked what advice they give their mentees about aspects of the application process, including gap years, dual applications, research involvement, couples matching, program signaling, away rotations, internship year, letters of recommendation, geographic signaling, interviewing advice, and volunteering during medical school.

On August 18, 2024, survey results from 115 respondents were aggregated. The responses for each question were quantitatively assessed to determine whether there was consensus on specific advice offered. The open-ended responses also were qualitatively assessed to determine the most common responses.

Results

The respondents included program directors (30% [35/115]), clinical faculty (22% [25/115]), department chairs (18% [21/115]), assistant program directors (15% [17/115]), medical school clerkship directors (8% [9/115]), primary mentors (ie, faculty who did not fall into any of the aforementioned categories but still advised medical students interested in dermatology)(5% [6/115]), division chiefs (1% [1/115]), and deans (1% [1/115]). Respondents had been advising students for a median of 10 years (range, 1-40 years [25th percentile, 5.00 years; 75th percentile, 13.75 years]). The majority (90% [103/115]) of mentors surveyed were advising students with a home dermatology program.

Areas of Consensus

In some areas, there was broad consensus among the advice offered by the mentors that were surveyed (eTable).

Research During Medical School—More than 91% (105/115) of the respondents recommended research to encourage academic growth and indicated that the most important reason for conducting research during medical school is to foster mentor-mentee relationships; however, more than one-third of respondents believed research is overvalued by students and research productivity is not as critical for matching as they perceive it to be. When these responses were categorized by respondent positions, 29% (15/52) of program or assistant directors indicated agreement with the statement that research is overvalued.

Away Rotations—There also was a consensus about the importance of away rotations, with 85% (98/115) of respondents advising students to complete 1 to 2 away rotations at sites of high interest, and 13% (15/115) suggesting that students complete as many away rotations as possible. It is worth noting, however, that the official APD Residency Program Directors Section’s statement on away rotations recommends no more than 2 away rotations (or no more than 3 for students with no home program).4

Reapplication Advice—Additionally, in a situation where students do not match into a dermatology residency program, the vast majority (71% [82/115]) of respondents advised students to rank competitive intern years to foster connections and improve the chance of matching on the second attempt.

Volunteering During Medical School—Seventy-seven percent (89/115) of mentors encouraged students to engage in volunteerism and advocacy during medical school to create a well-rounded application, and 69% (79/115) of mentors encouraged students to display leadership in their volunteer efforts.

Areas Without Consensus

Letters of Recommendation—Most respondents recommended submitting letters of recommendation only from dermatology professionals (55% [63/115]), with the remainder recommending students request a letter from anyone who could provide a strong recommendation regardless of specialty mix (42% [48/115]).

Dermatologic Subspecialties—For students interested in dermatologic subspecialties, 73% (84/115) of mentors advised that students be honest during interviews but keep an open mind that interests during residencies may change. Forty-three percent (49/115) of respondents encouraged students to promote a subspecialty interest during their interview only if they can demonstrate effort within that subspecialty on their application.

Couples Matching—Most respondents approach couples matching on a case-by-case basis and assess individual priorities when they do advise on this topic. Respondents often advise applicants to identify a few cities/regions and focus strongly on the programs within those regions to avoid spreading themselves too thin; however, one-third (38/115) of respondents indicated that they do not personally offer advice regarding the couples match.

Areas With Diverse Opinions

Gap Years—Nearly one-quarter (24% [28/115]) of mentors reported that they rarely recommend students take a year off and only support those who are adamant about doing so, or that they never support taking a gap year at all. A slight majority (58% [67/115]) recommend a gap year for students strongly interested in dermatologic research, and 38% (44/115) recommend a gap year for students with weaker applications (Figure 1). We received many open-ended responses to this question, with mentors frequently indicating that they advise students to take a gap year on a case-by-case basis, with 44% (51/115) of commenters recommending that students only take paid gap-year research positions.

Program Signaling—The dermatology residency application process implemented a system of preference signaling tokens (PSTs) starting with the 2021-2022 cycle. Not quite half (46% [53/115]) of respondents recommend students apply only to places that they signaled, while 20% (23/115) advise responding to 10 to 15 additional programs. Very few (8% [9/115]) advise students to signal only in their stated region of interest. Approximately half (49% [56/115]) of mentors recommend students only signal based on the programs they feel would be the best fit for them without regard for perceived competitiveness—which aligns with the APD Residency Program Directors Section’s recommendation4—while 37% (43/115) recommend students distribute their signals to a wide range of programs. Sixty-three percent (72/115) of respondents recommend gold signaling to the student’s 3 most desired programs regardless of home and away rotation considerations, while 19% (22/115) recommend students give silver signals to their home and away rotation programs, as a rotation is already a signal of a strong desire to be there (Figure 2).

Dual Application—Fifty-three percent (61/115) of mentors recommended dual applying only for those truly interested in multiple specialties. Eighteen percent (21/115) of respondents advised dual applying for those with less than a 75% chance of matching. Twenty-five percent (29/115) of respondents free-wrote comments about approaching dual applying on a case-by-case basis, with many discussing the downsides of dual application and raising concerns that dual applications can hinder applicants’ success, can seem disingenuous, and seem to be a tool used to improve medical school match rates without benefit for the student.

We also stratified the data to compare overall responses from the total cohort with those from only program and assistant program directors. Across the 14 questions, responses from program and assistant program directors alone were similar to the overall cohort results

Comment

This study evaluated nationwide data on mentorship advising in dermatology, detailing mentors’ advice regarding research, gap years, dual applications, away rotations, intern year, couples matching, program signaling, and volunteering during medical school. Based on our results, most respondents agree on the importance of research during medical school, the utility of away rotations, and the value of volunteering during medical school. Similarly, respondents agreed on the importance of having strong letters of recommendation; while some advised asking only dermatology faculty to write letters, others did not have a specialty preference for the letter writers. Respondents also had varying views about sharing interest in subspecialties during residency interviews. Many of the respondents do not provide recommendations regarding geographic signaling and couples matching, expressing that these are parts of an application that are important to approach on a case-by-case basis. Lastly, respondents had diverse opinions regarding the utility of gap years, whether to encourage or discourage dual applications, and how to advise regarding program signaling.

Our results also showed that one-third of respondents believed that research is not as important as it is perceived to be by dermatology applicants. While engaging in research during medical school was almost unanimously encouraged to foster mentor-mentee relationships, respondents expressed that the number of research experiences and publications was not critical. This is an important topic of discussion, as taking a dedicated year away from medical school to complete a research fellowship is becoming a trend among dermatology applicants.5 There has been discussion both on unofficial online platforms as well as in the published literature regarding the pressure for medical students interested in dermatology to publish, which may result in a gap year for research.6 The literature on the utility of a gap year in match rates is sparse, with one study showing no difference in match rates among Mayo Clinic dermatology residents who took research years vs those who did not.7 However, this contrasts with match rates at top dermatology residency programs where 41% of applicants who took a gap year matched vs 19% who did not.7,8 These conflicting data are reflected in our study results, with respondents expressing different opinions on the utility of gap years.

There also are important equity concerns regarding the role of research years in the dermatology residency match process. Dermatology is one of the least racially diverse specialties, although there have been efforts to increase representation among residents and attending physicians.9-11 Research years can be important contributors to this lack of representation, as these often are unpaid and can discourage economically disadvantaged students from applying.9-11 Additionally, applicants may not have the flexibility to defer future salary for a year to match into dermatology; therefore, mentors should offer multiple options to individual applicants instead of solely encouraging gap years, given the conflicting feelings regarding their productivity.

Another topic of disagreement was dual application. Approximately one-third of respondents said they encourage either all students or those with less than a 75% chance of matching to dual apply, while about half only encourage students who are truly interested in multiple specialties to do so. Additionally, a large subset of respondents said they do not encourage dual applications due to concerns that they make applicants a worse candidate for each specialty and overall have negative effects on matching. Twenty-five percent of respondents opted to leave an open-ended response to this question: some offered the perspective that, if applicants feel a need to dual apply due to a weaker application, they do not advise the applicant to apply to dermatology. Many open ended responses underscored that the respondent does not encourage dual applications because they are inherently more time consuming, could hinder the applicant’s success, can seem disingenuous, and are a tool used to improve medical school match rates without being beneficial for the student. Some respondents also favored reapplying to dermatology the following year instead of dual applying. Finally, a subset of mentors indicated that they approach dual applications on a case-by-case basis, and others reported they do not have much experience advising on this topic. Currently, there are no known data in the literature on the efficacy and utility of dual applications in the dermatology match process; therefore, our study provides valuable insight for applicants interested in the impacts of the dual application. Overall, students should approach this option with mentors on an individual basis but ultimately should be aware of the concerns and mixed perceptions of the dual application process.

With regard to program signaling, previous research has shown that PSTs have a large impact on the chance of being granted an interview.12 In our study, we provide a comprehensive overview of advising regarding these signals. While mentors often responded that they did not have much experience advising in this domain—and it is too soon to tell the impact of this program signaling—many offered differing opinions. Many said they recommend that students give a gold signal to their 3 most desired programs regardless of home and away rotations and perceived competitiveness, which follows the guidelines issued by the APD; however, 19% recommend only giving silver signals to home and away rotation programs, as participation in those programs is considered a sufficient signal of interest. Additionally, about half of mentors recommended that students only apply where they signal, whereas 20% recommended applying to 10 to 15 programs beyond those signaled. Future studies should investigate the impact of PSTs on interview invitations once sufficient application cycles have occurred.

Study Limitations

This study was conducted via email to the APD listserve. The total number of faculty on this listserve is unknown; therefore, we do not know the total response rate of the survey. Additionally, we surveyed mentors in this listserve, who therefore receive more emails and overall correspondence about the dermatology match and may be more involved in these conversations. The mentors who responded to our survey may have a different approach and response to our various survey questions than a given mentor across the United States who did not respond to this survey. A final limitation of our study is that the survey responses a mentor gives may not fully match the advice that they give their students privately.

Conclusion

Our survey of dermatology mentors across the United States provides valuable insight into how mentors advise for a strong dermatology residency application. Mentors agreed on the importance of research during medical school, away rotations, strong letters of recommendation, and volunteerism and advocacy to promote a strong residency application. Important topics of disagreement include the decision for dermatology applicants to take a dedicated gap year in medical school, how to use tokens/signals effectively, and the dual application process. Our findings also underscore important application components that applicants and mentors should approach on an individual basis. Future studies should investigate the impact of signals/tokens on the match process as well as the utility of gap years and dual applications, working to standardize the advice applicants receive.

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt4604h1w4.

- Kolli SS, Feldman SR, Huang WW. The dermatology residency application process. Dermatol Online J. 2021;26:13030/qt4k1570vj.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.303

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section Information Regarding the 2023-2024 Application Cycle. Published 2023. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/12386/download

- Alikhan A, Sivamani RK, Mutizwa MM, et al. Advice for medical students interested in dermatology: perspectives from fourth year students who matched. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:4.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230. doi:10.1111/ijd.15964

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wassef C, et al. The importance of mentorship during research gap years for the dermatology residency match. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E209-E210. doi:10.1111/ijd.16084

- Zheng DX, Gallo Marin B, Mulligan KM, et al. Inequity concerns surrounding research years and the dermatology residency match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:E247-E248. doi:10.1111/ijd.16179

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Cordova A, et al. Challenging the status quo: increasing diversity in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E421. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.185

- Dirr MA, Brownstone N, Zakria D, et al. Dermatology match preference signaling tokens: impact and implications. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1367-1368. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003645

- Ramachandran V, Nguyen HY, Dao H Jr. Does it match? analyzing self-reported online dermatology match data to charting outcomes in the match. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt4604h1w4.

- Kolli SS, Feldman SR, Huang WW. The dermatology residency application process. Dermatol Online J. 2021;26:13030/qt4k1570vj.

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.303

- Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section Information Regarding the 2023-2024 Application Cycle. Published 2023. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/12386/download

- Alikhan A, Sivamani RK, Mutizwa MM, et al. Advice for medical students interested in dermatology: perspectives from fourth year students who matched. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:4.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230. doi:10.1111/ijd.15964

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wassef C, et al. The importance of mentorship during research gap years for the dermatology residency match. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E209-E210. doi:10.1111/ijd.16084

- Zheng DX, Gallo Marin B, Mulligan KM, et al. Inequity concerns surrounding research years and the dermatology residency match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:E247-E248. doi:10.1111/ijd.16179

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Cordova A, et al. Challenging the status quo: increasing diversity in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E421. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.185

- Dirr MA, Brownstone N, Zakria D, et al. Dermatology match preference signaling tokens: impact and implications. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1367-1368. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003645

A Nationwide Survey of Dermatology Faculty and Mentors on Their Advice for the Dermatology Match Process

A Nationwide Survey of Dermatology Faculty and Mentors on Their Advice for the Dermatology Match Process

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatology mentors should abide by Association of Professors of Dermatology guidelines when advising regarding signals and away rotations.

- Mentors agree with the utility of research during medical school, completing away rotations, and volunteering during medical school.

- There are differing opinions regarding the utility of a research year, program signaling, couples matching, and dual applying.

Asymptomatic Papules on the Neck

THE DIAGNOSIS: White Fibrous Papulosis

Given the histopathology findings, location on a sun-exposed site, lack of any additional systemic signs or symptoms, and no family history of similar lesions to suggest an underlying genetic condition, a diagnosis of white fibrous papulosis (WFP) was made. White fibrous papulosis is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder that was first reported by Shimizu et al1 in 1985. It is characterized by numerous grouped, 2- to 3-mm, white to flesh-colored papules that in most cases are confined to the neck in middle-aged to elderly individuals; however, cases involving the upper trunk and axillae also have been reported.1-3 The etiology of this condition is unclear but is thought to be related to aging and chronic exposure to UV light. Although treatment is not required, various modalities including tretinoin, excision, and laser therapy have been trialed with varying success.2,4 Our patient elected not to proceed with treatment.

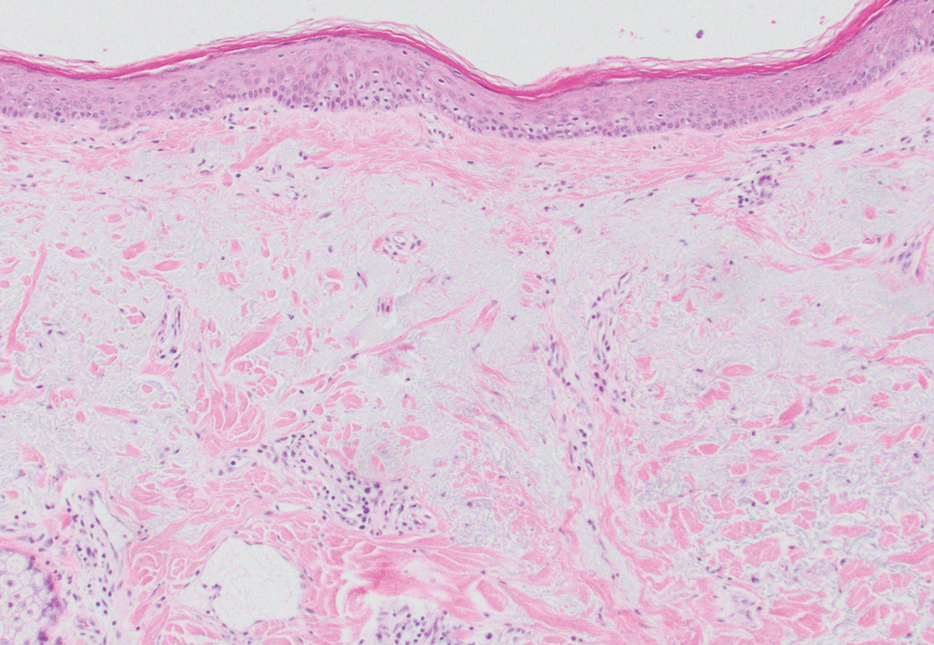

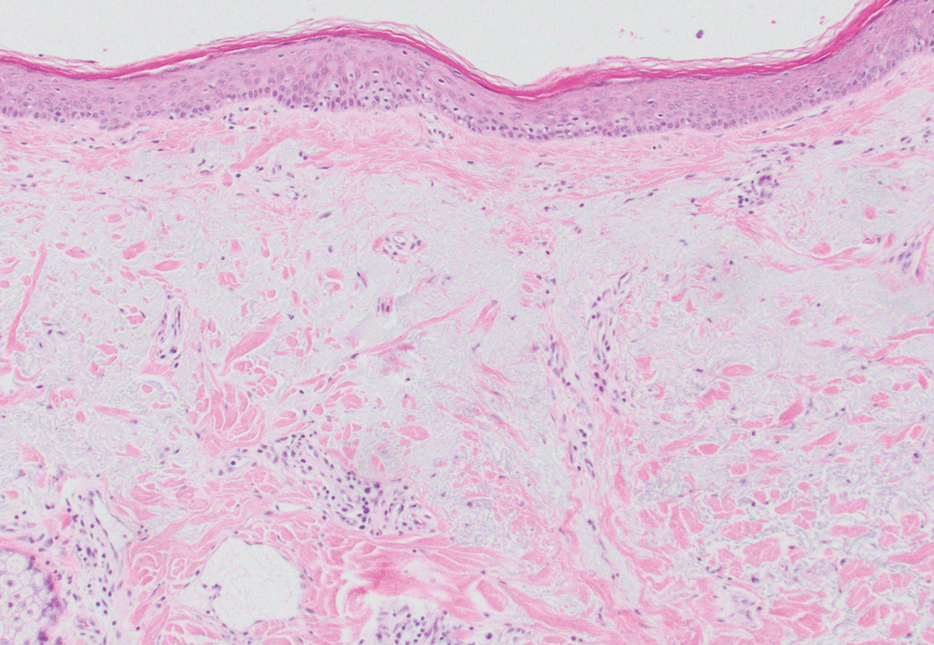

Histologically, WFP may manifest similarly to connective tissue nevi; the overall architecture is nonspecific with focally thickened collagen and often elastic fibers that may be normal to reduced and/or fragmented, as well as an overall decrease in superficial dermal elastic tissue.3,5 Therefore, the differential diagnosis may include connective tissue nevi and require clinical correlation to make a correct diagnosis.

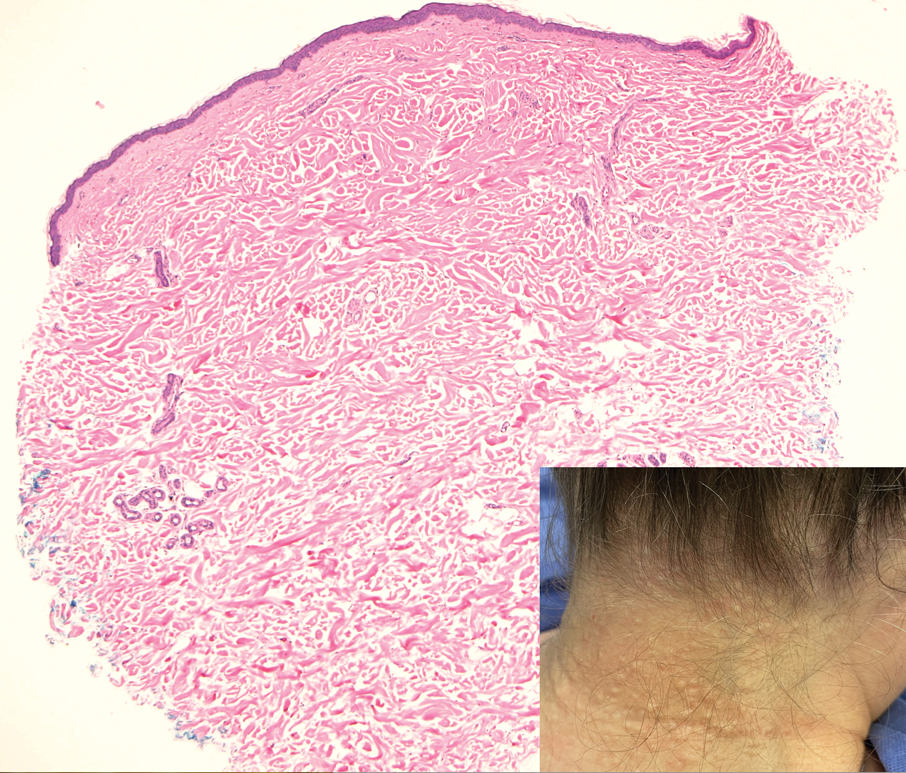

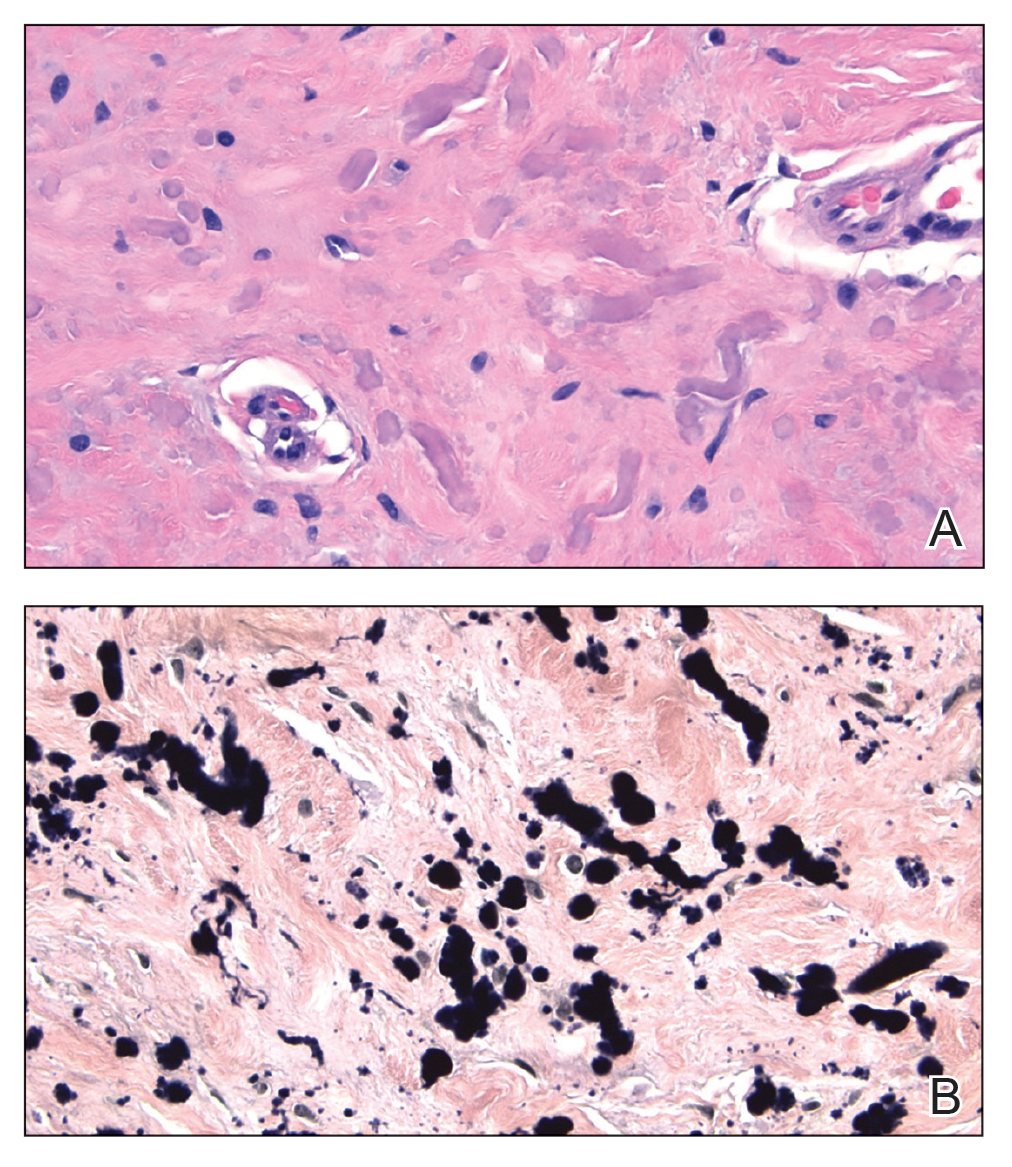

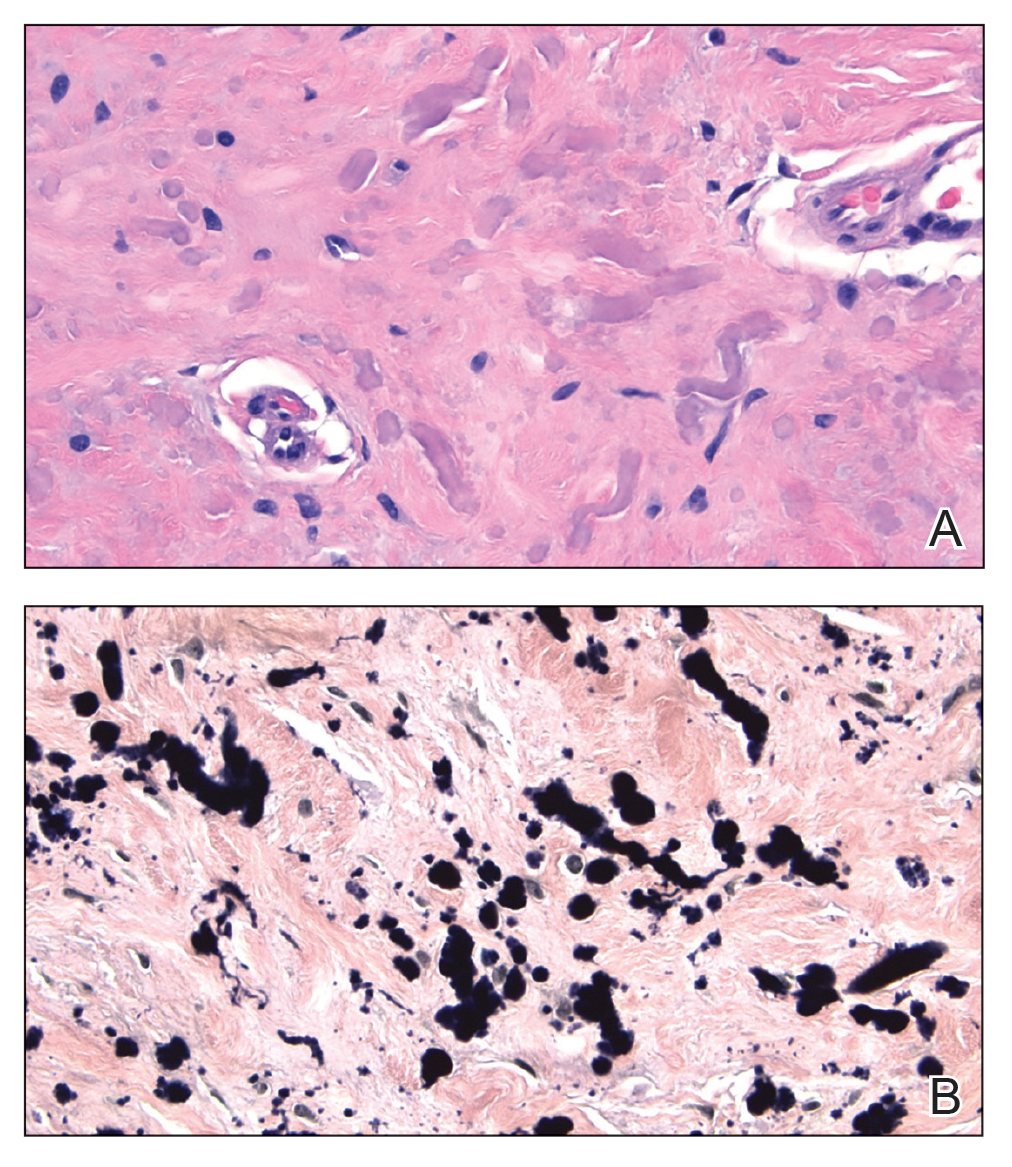

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is an autosomalrecessive disorder most commonly related to mutations in the ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 6 (ABCC6) gene that tends to manifest clinically on the neck and flexural extremities.6 This disease affects elastic fibers, which may become calcified over time. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is associated with ocular complications relating to the Bruch membrane of the retina and angioid streaks; choroidal neovascularization involving the damaged Bruch membrane and episodes of acute retinopathy may result in vision loss in later stages of the disease.7 Involvement of the elastic laminae of arteries can be associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications such as stroke, coronary artery disease, claudication, and aneurysms. Involvement of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts also may occur and most commonly manifests with bleeding. Pathologic alterations in the elastic fibers of the lungs also have been reported in patients with PXE.8 Histologically, PXE exhibits increased abnormally clumped and fragmented elastic fibers in the superficial dermis, often with calcification (Figure 1). Pseudo-PXE related to D-penicillamine use often lacks calcification and has a bramble bush appearance.9

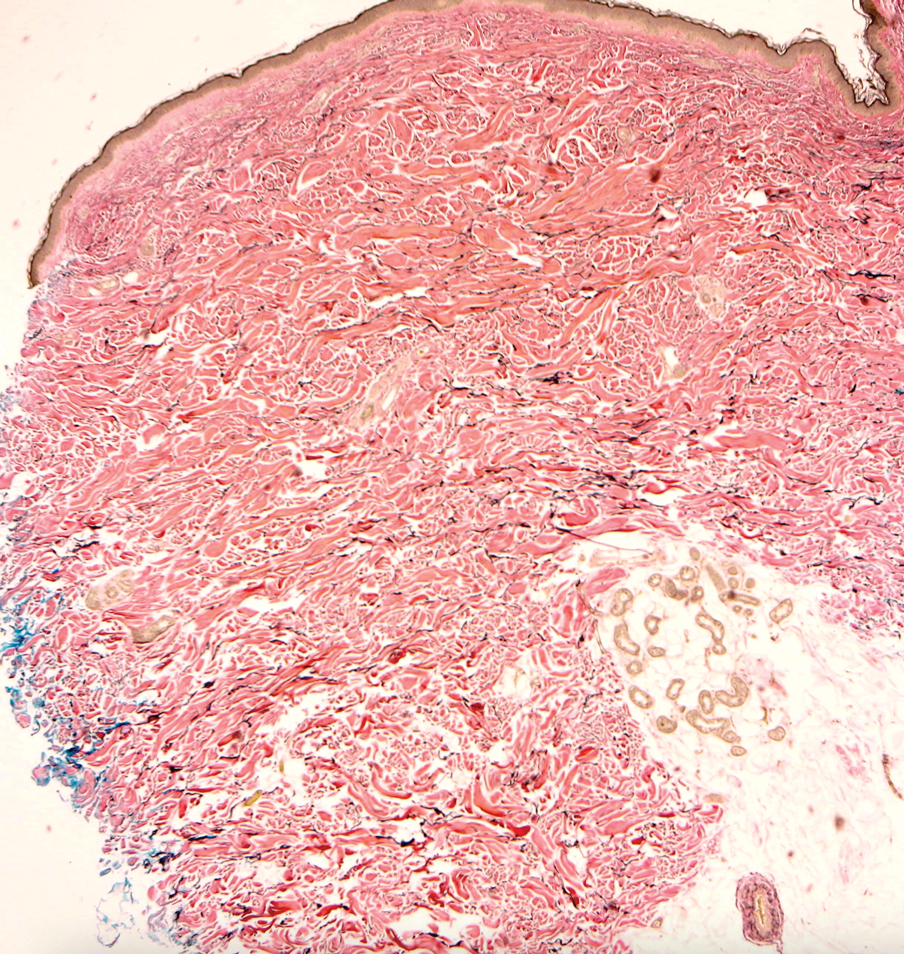

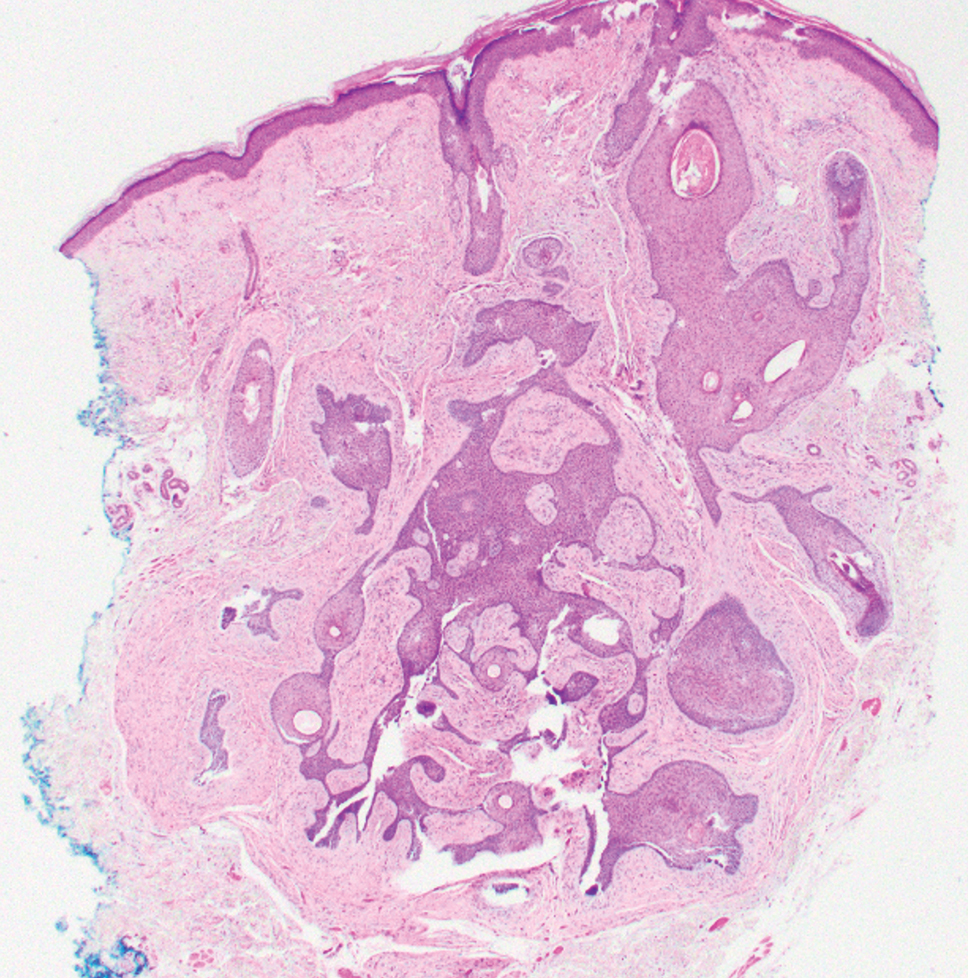

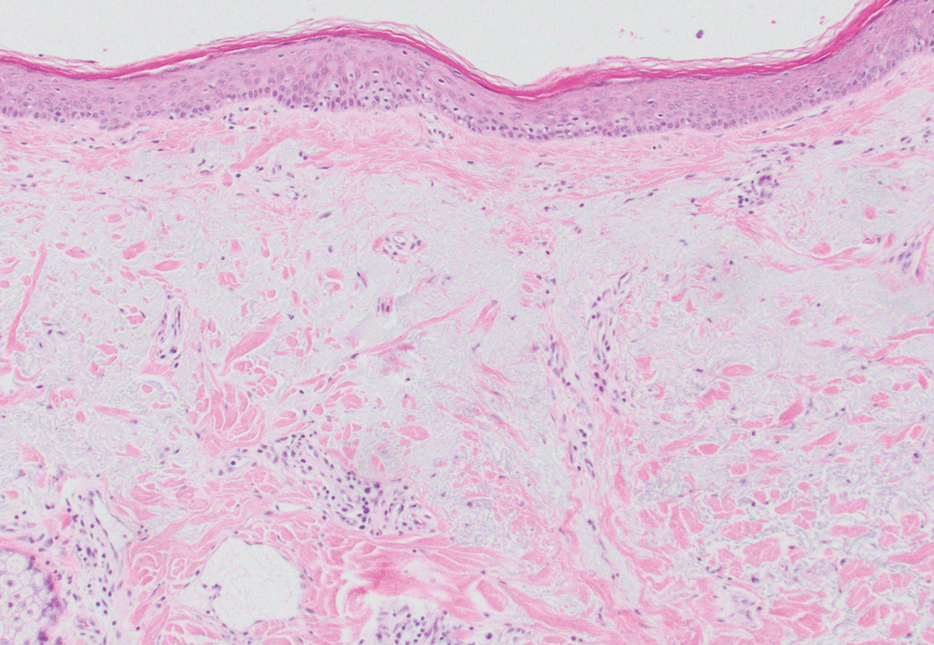

Fibrofolliculomas may manifest alone or in association with an underlying condition such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, in which lesions are most frequently seen scattered on the scalp, face, ears, neck, or upper trunk.10 This condition is related to a folliculin (FLCN) gene germline mutation. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome also may be associated with acrochordons, trichodiscomas, renal cancer, and lung cysts with or without spontaneous pneumothorax. Less frequently noted findings include oral papules, epidermal cysts, angiofibromas, lipomas/angiolipomas, parotid gland tumors, and thyroid neoplasms. Connective tissue nevi/collagenomas can appear clinically similar to fibrofolliculomas; true connective tissue nevi are reported less commonly in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.11 Histologically, a fibrofolliculoma manifests with epidermal strands originating from a hair follicle associated with prominent surrounding connective tissue (Figure 2).

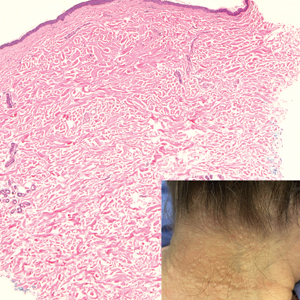

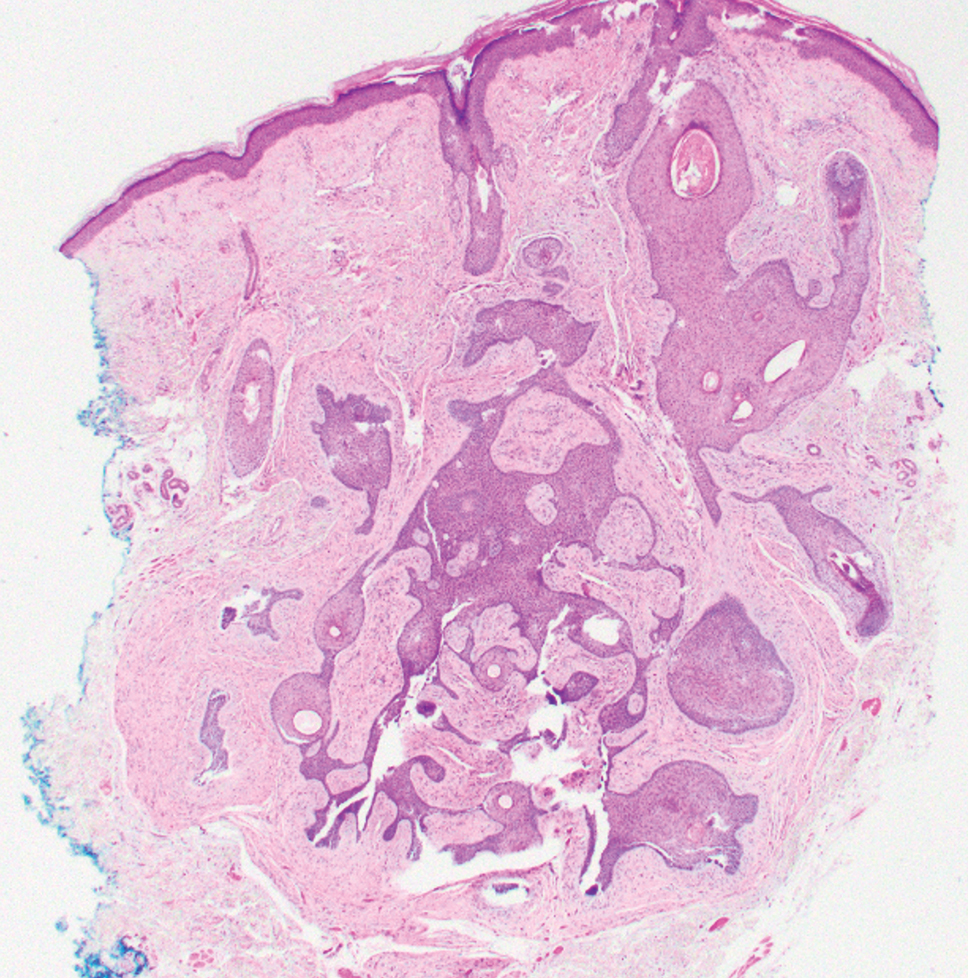

Elastofibroma dorsi is a benign tumor of connective tissue that most commonly manifests clinically as a solitary subcutaneous mass on the back near the inferior angle of the scapula; it typically develops below the rhomboid major and latissimus dorsi muscles.12 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but some patients have reported a family history of the condition or a history of repetitive shoulder movement/trauma prior to onset; the mass may be asymptomatic or associated with pain and/or swelling. Those affected tend to be older than 50 years.13 Histologically, thickened and rounded to beaded elastic fibers are seen admixed with collagen (Figure 3).

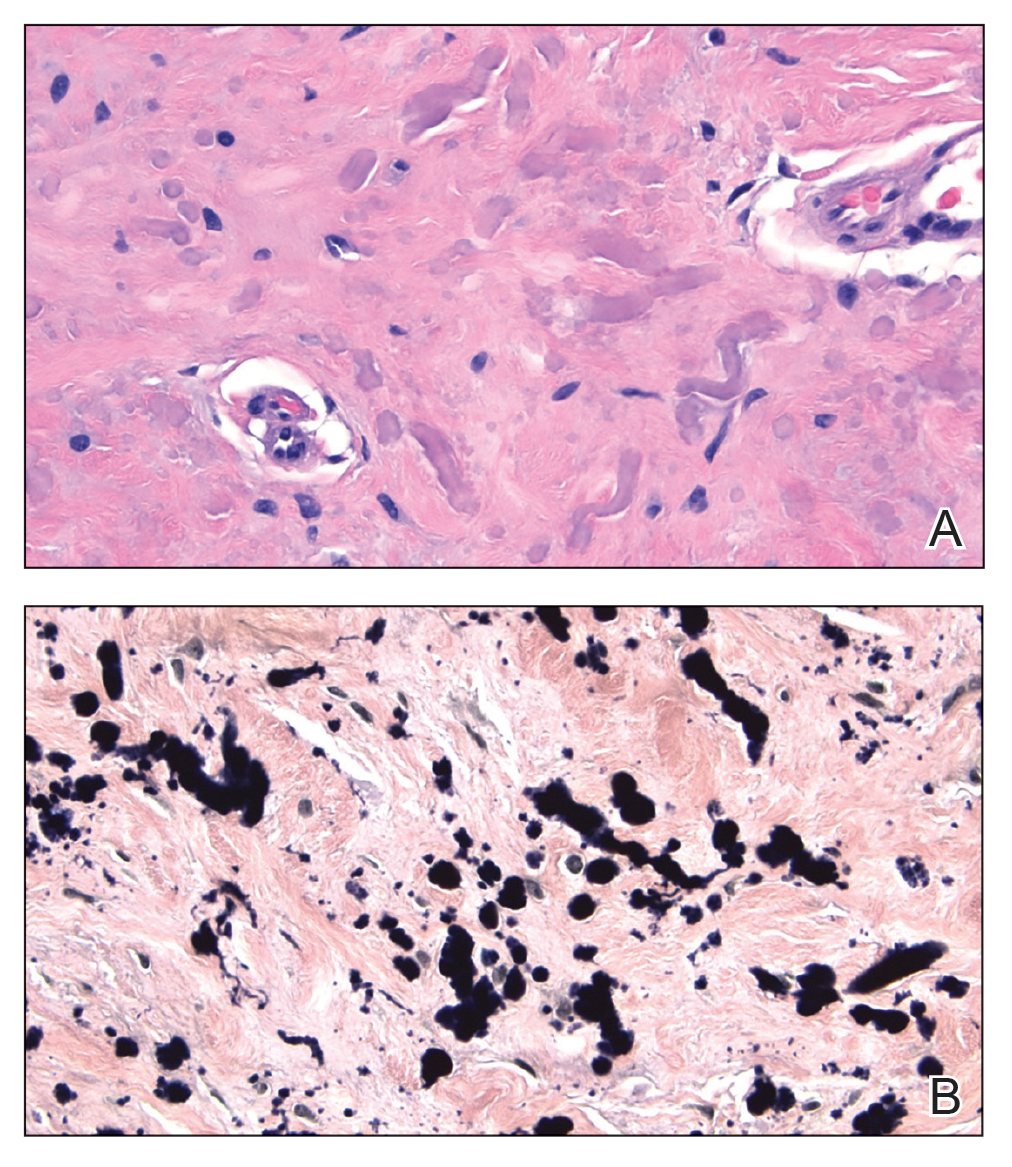

Actinic (solar) elastosis frequently is encountered in many skin biopsies and is caused by chronic photodamage. More hypertrophic variants, such as papular or nodular solar elastosis, may clinically manifest similarly to WFP.14 Histologically, actinic elastosis manifests as a considerable increase in elastic tissue in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 4).

- Shimizu H, Nishikawa T, Kimura S. White fibrous papulosis of the neck: review of our 16 cases. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;95:1077-1084.

- Teo W, Pang S. White fibrous papulosis of the chest and back. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB33.

- Dokic Y, Tschen J. White fibrous papulosis of the axillae and neck. Cureus. 2020;12:E7635.

- Lueangarun S, Panchaprateep R. White fibrous papulosis of the neck treated with fractionated 1550-nm erbium glass laser: a case report. J Lasers Med Sci. 2016;7:256-258.

- Rios-Gomez M, Ramos-Garibay JA, Perez-Santana ME, et al. White fibrous papulosis of the neck: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25661.

- Váradi A, Szabó Z, Pomozi V, et al. ABCC6 as a target in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:671-682.

- Gliem M, Birtel J, Müller PL, et al. Acute retinopathy in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:1165-1173.

- Germain DP. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:85. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0639-8

- Chisti MA, Binamer Y, Alfadley A, et al. D-penicillamine-induced pseudo-pseudoxanthoma elasticum and extensive elastosis perforans serpiginosa with excellent response to acitretin. Ann Saudi Med. 2019;39:56-60.

- Criscito MC, Mu EW, Meehan SA, et al. Dermoscopic features of a solitary fibrofolliculoma on the left cheek. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2 suppl 1):S8-S9.

- Sattler EC, Steinlein OK. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Updated January 30, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1522

- Patnayak R, Jena A, Settipalli S, et al. Elastofibroma: an uncommon tumor revisited. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:34-37. doi:10.4103/0974- 2077.178543

- Chandrasekar CR, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: an uncommon benign pseudotumour. Sarcoma. 2008;2008:756565. doi:10.1155/2008/756565

- Kwittken J. Papular elastosis. Cutis. 2000;66:81-83.

THE DIAGNOSIS: White Fibrous Papulosis

Given the histopathology findings, location on a sun-exposed site, lack of any additional systemic signs or symptoms, and no family history of similar lesions to suggest an underlying genetic condition, a diagnosis of white fibrous papulosis (WFP) was made. White fibrous papulosis is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder that was first reported by Shimizu et al1 in 1985. It is characterized by numerous grouped, 2- to 3-mm, white to flesh-colored papules that in most cases are confined to the neck in middle-aged to elderly individuals; however, cases involving the upper trunk and axillae also have been reported.1-3 The etiology of this condition is unclear but is thought to be related to aging and chronic exposure to UV light. Although treatment is not required, various modalities including tretinoin, excision, and laser therapy have been trialed with varying success.2,4 Our patient elected not to proceed with treatment.

Histologically, WFP may manifest similarly to connective tissue nevi; the overall architecture is nonspecific with focally thickened collagen and often elastic fibers that may be normal to reduced and/or fragmented, as well as an overall decrease in superficial dermal elastic tissue.3,5 Therefore, the differential diagnosis may include connective tissue nevi and require clinical correlation to make a correct diagnosis.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is an autosomalrecessive disorder most commonly related to mutations in the ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 6 (ABCC6) gene that tends to manifest clinically on the neck and flexural extremities.6 This disease affects elastic fibers, which may become calcified over time. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is associated with ocular complications relating to the Bruch membrane of the retina and angioid streaks; choroidal neovascularization involving the damaged Bruch membrane and episodes of acute retinopathy may result in vision loss in later stages of the disease.7 Involvement of the elastic laminae of arteries can be associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications such as stroke, coronary artery disease, claudication, and aneurysms. Involvement of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts also may occur and most commonly manifests with bleeding. Pathologic alterations in the elastic fibers of the lungs also have been reported in patients with PXE.8 Histologically, PXE exhibits increased abnormally clumped and fragmented elastic fibers in the superficial dermis, often with calcification (Figure 1). Pseudo-PXE related to D-penicillamine use often lacks calcification and has a bramble bush appearance.9

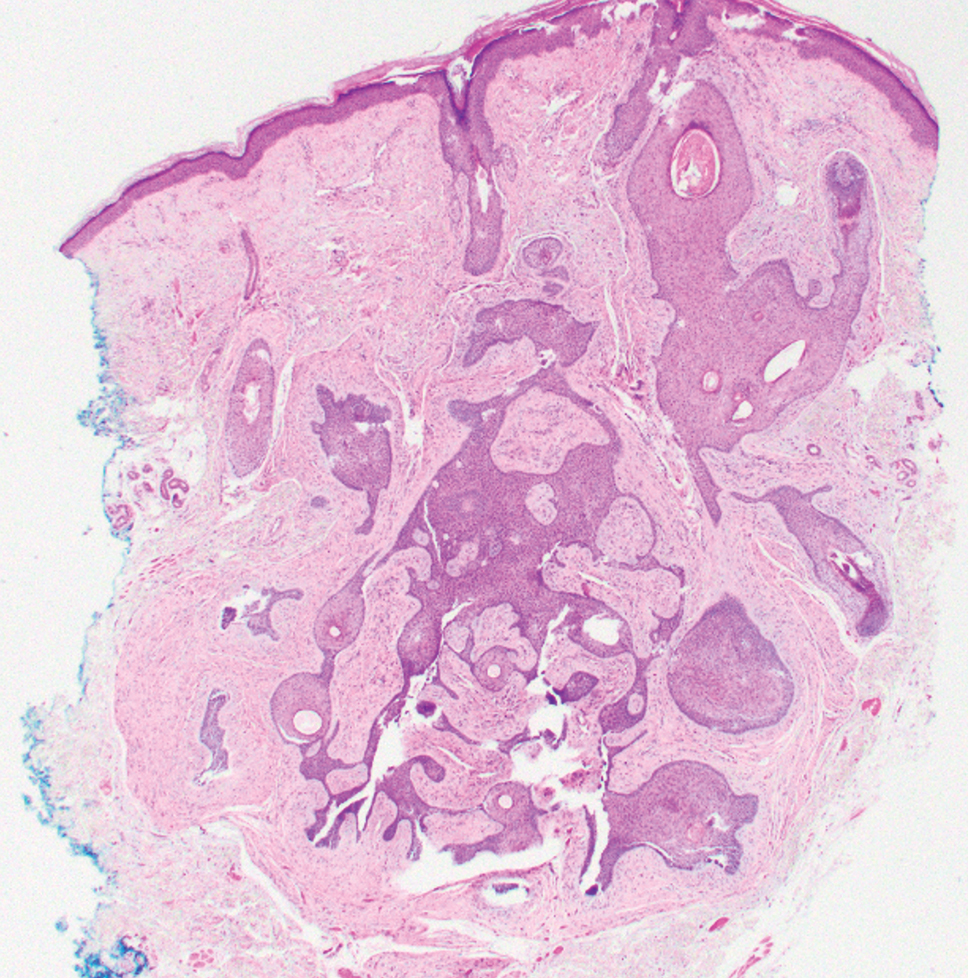

Fibrofolliculomas may manifest alone or in association with an underlying condition such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, in which lesions are most frequently seen scattered on the scalp, face, ears, neck, or upper trunk.10 This condition is related to a folliculin (FLCN) gene germline mutation. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome also may be associated with acrochordons, trichodiscomas, renal cancer, and lung cysts with or without spontaneous pneumothorax. Less frequently noted findings include oral papules, epidermal cysts, angiofibromas, lipomas/angiolipomas, parotid gland tumors, and thyroid neoplasms. Connective tissue nevi/collagenomas can appear clinically similar to fibrofolliculomas; true connective tissue nevi are reported less commonly in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.11 Histologically, a fibrofolliculoma manifests with epidermal strands originating from a hair follicle associated with prominent surrounding connective tissue (Figure 2).

Elastofibroma dorsi is a benign tumor of connective tissue that most commonly manifests clinically as a solitary subcutaneous mass on the back near the inferior angle of the scapula; it typically develops below the rhomboid major and latissimus dorsi muscles.12 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but some patients have reported a family history of the condition or a history of repetitive shoulder movement/trauma prior to onset; the mass may be asymptomatic or associated with pain and/or swelling. Those affected tend to be older than 50 years.13 Histologically, thickened and rounded to beaded elastic fibers are seen admixed with collagen (Figure 3).

Actinic (solar) elastosis frequently is encountered in many skin biopsies and is caused by chronic photodamage. More hypertrophic variants, such as papular or nodular solar elastosis, may clinically manifest similarly to WFP.14 Histologically, actinic elastosis manifests as a considerable increase in elastic tissue in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 4).

THE DIAGNOSIS: White Fibrous Papulosis

Given the histopathology findings, location on a sun-exposed site, lack of any additional systemic signs or symptoms, and no family history of similar lesions to suggest an underlying genetic condition, a diagnosis of white fibrous papulosis (WFP) was made. White fibrous papulosis is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder that was first reported by Shimizu et al1 in 1985. It is characterized by numerous grouped, 2- to 3-mm, white to flesh-colored papules that in most cases are confined to the neck in middle-aged to elderly individuals; however, cases involving the upper trunk and axillae also have been reported.1-3 The etiology of this condition is unclear but is thought to be related to aging and chronic exposure to UV light. Although treatment is not required, various modalities including tretinoin, excision, and laser therapy have been trialed with varying success.2,4 Our patient elected not to proceed with treatment.

Histologically, WFP may manifest similarly to connective tissue nevi; the overall architecture is nonspecific with focally thickened collagen and often elastic fibers that may be normal to reduced and/or fragmented, as well as an overall decrease in superficial dermal elastic tissue.3,5 Therefore, the differential diagnosis may include connective tissue nevi and require clinical correlation to make a correct diagnosis.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is an autosomalrecessive disorder most commonly related to mutations in the ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 6 (ABCC6) gene that tends to manifest clinically on the neck and flexural extremities.6 This disease affects elastic fibers, which may become calcified over time. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is associated with ocular complications relating to the Bruch membrane of the retina and angioid streaks; choroidal neovascularization involving the damaged Bruch membrane and episodes of acute retinopathy may result in vision loss in later stages of the disease.7 Involvement of the elastic laminae of arteries can be associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications such as stroke, coronary artery disease, claudication, and aneurysms. Involvement of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts also may occur and most commonly manifests with bleeding. Pathologic alterations in the elastic fibers of the lungs also have been reported in patients with PXE.8 Histologically, PXE exhibits increased abnormally clumped and fragmented elastic fibers in the superficial dermis, often with calcification (Figure 1). Pseudo-PXE related to D-penicillamine use often lacks calcification and has a bramble bush appearance.9

Fibrofolliculomas may manifest alone or in association with an underlying condition such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, in which lesions are most frequently seen scattered on the scalp, face, ears, neck, or upper trunk.10 This condition is related to a folliculin (FLCN) gene germline mutation. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome also may be associated with acrochordons, trichodiscomas, renal cancer, and lung cysts with or without spontaneous pneumothorax. Less frequently noted findings include oral papules, epidermal cysts, angiofibromas, lipomas/angiolipomas, parotid gland tumors, and thyroid neoplasms. Connective tissue nevi/collagenomas can appear clinically similar to fibrofolliculomas; true connective tissue nevi are reported less commonly in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.11 Histologically, a fibrofolliculoma manifests with epidermal strands originating from a hair follicle associated with prominent surrounding connective tissue (Figure 2).

Elastofibroma dorsi is a benign tumor of connective tissue that most commonly manifests clinically as a solitary subcutaneous mass on the back near the inferior angle of the scapula; it typically develops below the rhomboid major and latissimus dorsi muscles.12 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but some patients have reported a family history of the condition or a history of repetitive shoulder movement/trauma prior to onset; the mass may be asymptomatic or associated with pain and/or swelling. Those affected tend to be older than 50 years.13 Histologically, thickened and rounded to beaded elastic fibers are seen admixed with collagen (Figure 3).

Actinic (solar) elastosis frequently is encountered in many skin biopsies and is caused by chronic photodamage. More hypertrophic variants, such as papular or nodular solar elastosis, may clinically manifest similarly to WFP.14 Histologically, actinic elastosis manifests as a considerable increase in elastic tissue in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 4).

- Shimizu H, Nishikawa T, Kimura S. White fibrous papulosis of the neck: review of our 16 cases. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;95:1077-1084.

- Teo W, Pang S. White fibrous papulosis of the chest and back. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB33.

- Dokic Y, Tschen J. White fibrous papulosis of the axillae and neck. Cureus. 2020;12:E7635.

- Lueangarun S, Panchaprateep R. White fibrous papulosis of the neck treated with fractionated 1550-nm erbium glass laser: a case report. J Lasers Med Sci. 2016;7:256-258.

- Rios-Gomez M, Ramos-Garibay JA, Perez-Santana ME, et al. White fibrous papulosis of the neck: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25661.

- Váradi A, Szabó Z, Pomozi V, et al. ABCC6 as a target in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:671-682.

- Gliem M, Birtel J, Müller PL, et al. Acute retinopathy in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:1165-1173.

- Germain DP. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:85. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0639-8

- Chisti MA, Binamer Y, Alfadley A, et al. D-penicillamine-induced pseudo-pseudoxanthoma elasticum and extensive elastosis perforans serpiginosa with excellent response to acitretin. Ann Saudi Med. 2019;39:56-60.

- Criscito MC, Mu EW, Meehan SA, et al. Dermoscopic features of a solitary fibrofolliculoma on the left cheek. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2 suppl 1):S8-S9.

- Sattler EC, Steinlein OK. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Updated January 30, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1522

- Patnayak R, Jena A, Settipalli S, et al. Elastofibroma: an uncommon tumor revisited. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:34-37. doi:10.4103/0974- 2077.178543

- Chandrasekar CR, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: an uncommon benign pseudotumour. Sarcoma. 2008;2008:756565. doi:10.1155/2008/756565

- Kwittken J. Papular elastosis. Cutis. 2000;66:81-83.

- Shimizu H, Nishikawa T, Kimura S. White fibrous papulosis of the neck: review of our 16 cases. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;95:1077-1084.

- Teo W, Pang S. White fibrous papulosis of the chest and back. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB33.

- Dokic Y, Tschen J. White fibrous papulosis of the axillae and neck. Cureus. 2020;12:E7635.

- Lueangarun S, Panchaprateep R. White fibrous papulosis of the neck treated with fractionated 1550-nm erbium glass laser: a case report. J Lasers Med Sci. 2016;7:256-258.

- Rios-Gomez M, Ramos-Garibay JA, Perez-Santana ME, et al. White fibrous papulosis of the neck: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:E25661.

- Váradi A, Szabó Z, Pomozi V, et al. ABCC6 as a target in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:671-682.

- Gliem M, Birtel J, Müller PL, et al. Acute retinopathy in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:1165-1173.

- Germain DP. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:85. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0639-8

- Chisti MA, Binamer Y, Alfadley A, et al. D-penicillamine-induced pseudo-pseudoxanthoma elasticum and extensive elastosis perforans serpiginosa with excellent response to acitretin. Ann Saudi Med. 2019;39:56-60.

- Criscito MC, Mu EW, Meehan SA, et al. Dermoscopic features of a solitary fibrofolliculoma on the left cheek. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2 suppl 1):S8-S9.

- Sattler EC, Steinlein OK. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Updated January 30, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1522

- Patnayak R, Jena A, Settipalli S, et al. Elastofibroma: an uncommon tumor revisited. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:34-37. doi:10.4103/0974- 2077.178543

- Chandrasekar CR, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, et al. Elastofibroma dorsi: an uncommon benign pseudotumour. Sarcoma. 2008;2008:756565. doi:10.1155/2008/756565

- Kwittken J. Papular elastosis. Cutis. 2000;66:81-83.

A 70-year-old woman with a history of osteoporosis and breast cancer presented for evaluation of asymptomatic, 2- to 3-mm, white to flesh-colored papules concentrated on the inferior occipital scalp and posterior neck (inset) for at least several months. She had no additional systemic signs or symptoms, and there was no family history of similar skin findings. A punch biopsy was performed.