User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Nontraditional therapies for treatment-resistant depression

Presently, FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies (eg, lithium, thyroid supplementation, stimulants, second-generation antipsychotics) for major depressive disorder (MDD) often produce less-than-desired outcomes while carrying a potentially substantial safety and tolerability burden. The lack of clinically useful and individual-based biomarkers (eg, genetic, neurophysiological, imaging) is a major obstacle to enhancing treatment efficacy and/or decreasing associated adverse effects (AEs). While the discovery of such tools is being aggressively pursued and ultimately will facilitate a more precision-based choice of therapy, empirical strategies remain our primary approach.

In controlled trials, several nontraditional treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have shown promise. These include “repurposed” (off-label) medications, herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

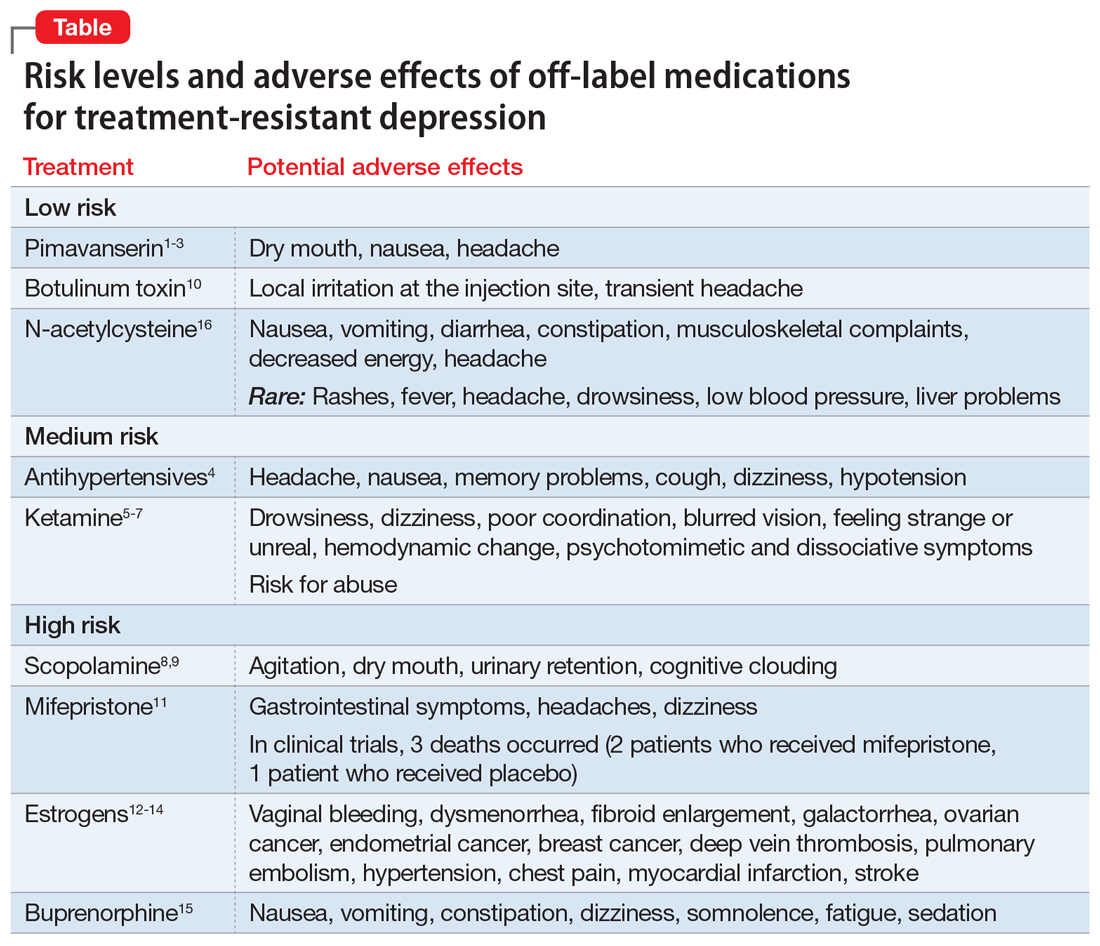

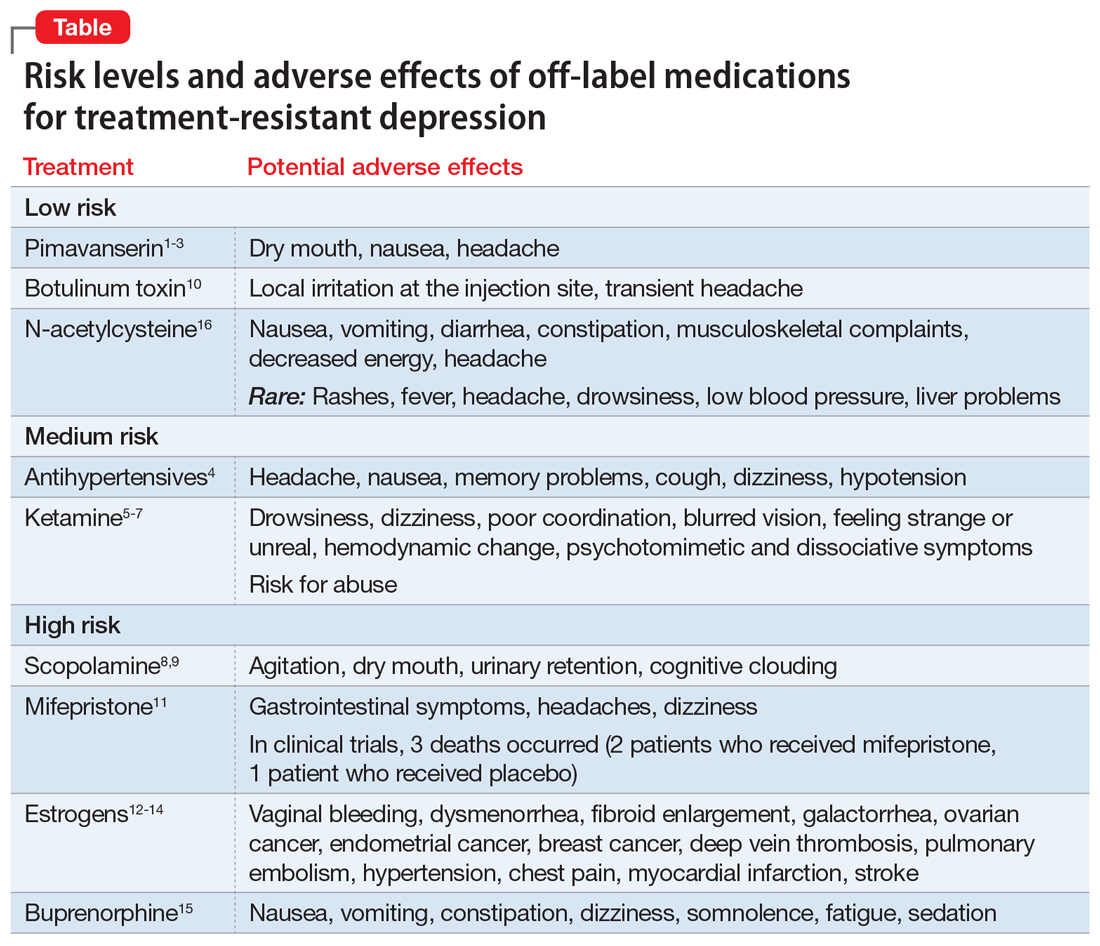

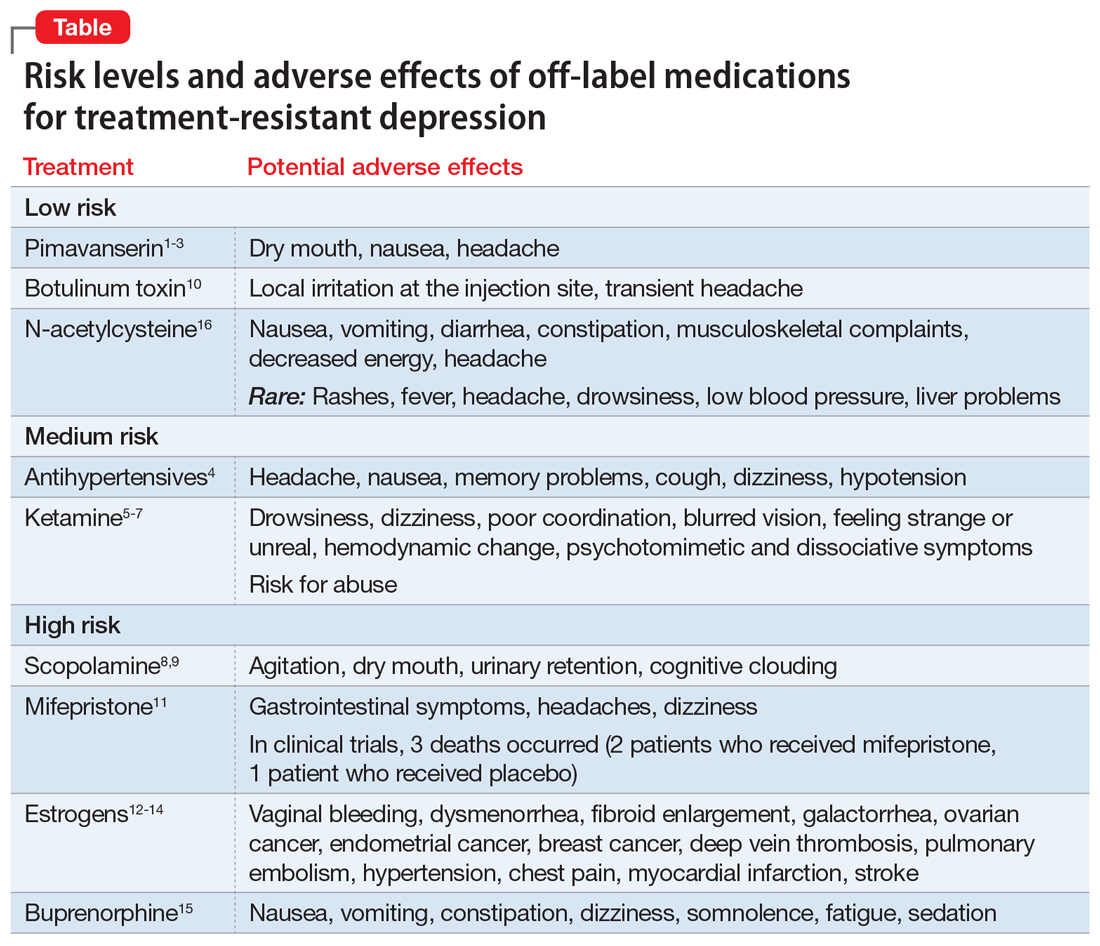

Importantly, some nontraditional treatments also demonstrate AEs (Table1-16). With a careful consideration of the risk/benefit balance, this article reviews some of the better-studied treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). In Part 1, we will examine off-label medications. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional approaches to TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

We believe this review will help clinicians who need to formulate a different approach after their patient with depression is not helped by traditional first-, second-, and third-line treatments. The potential options discussed in Part 1 of this article are categorized based on their putative mechanism of action (MOA) for depression.

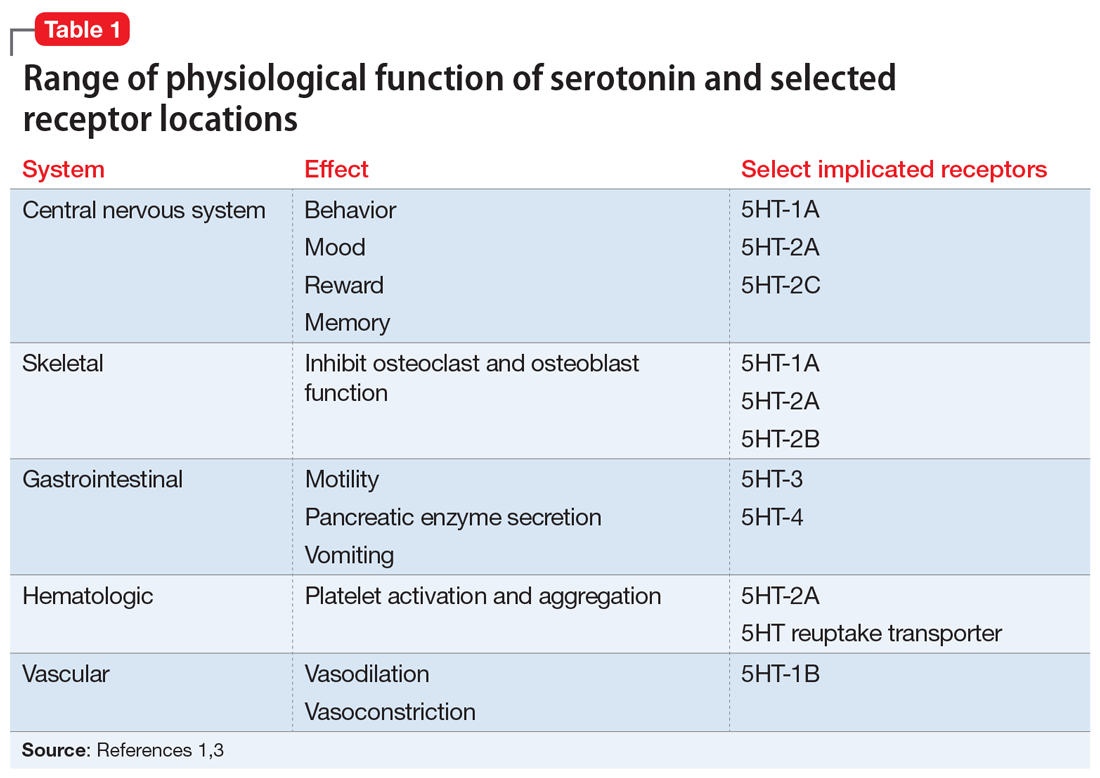

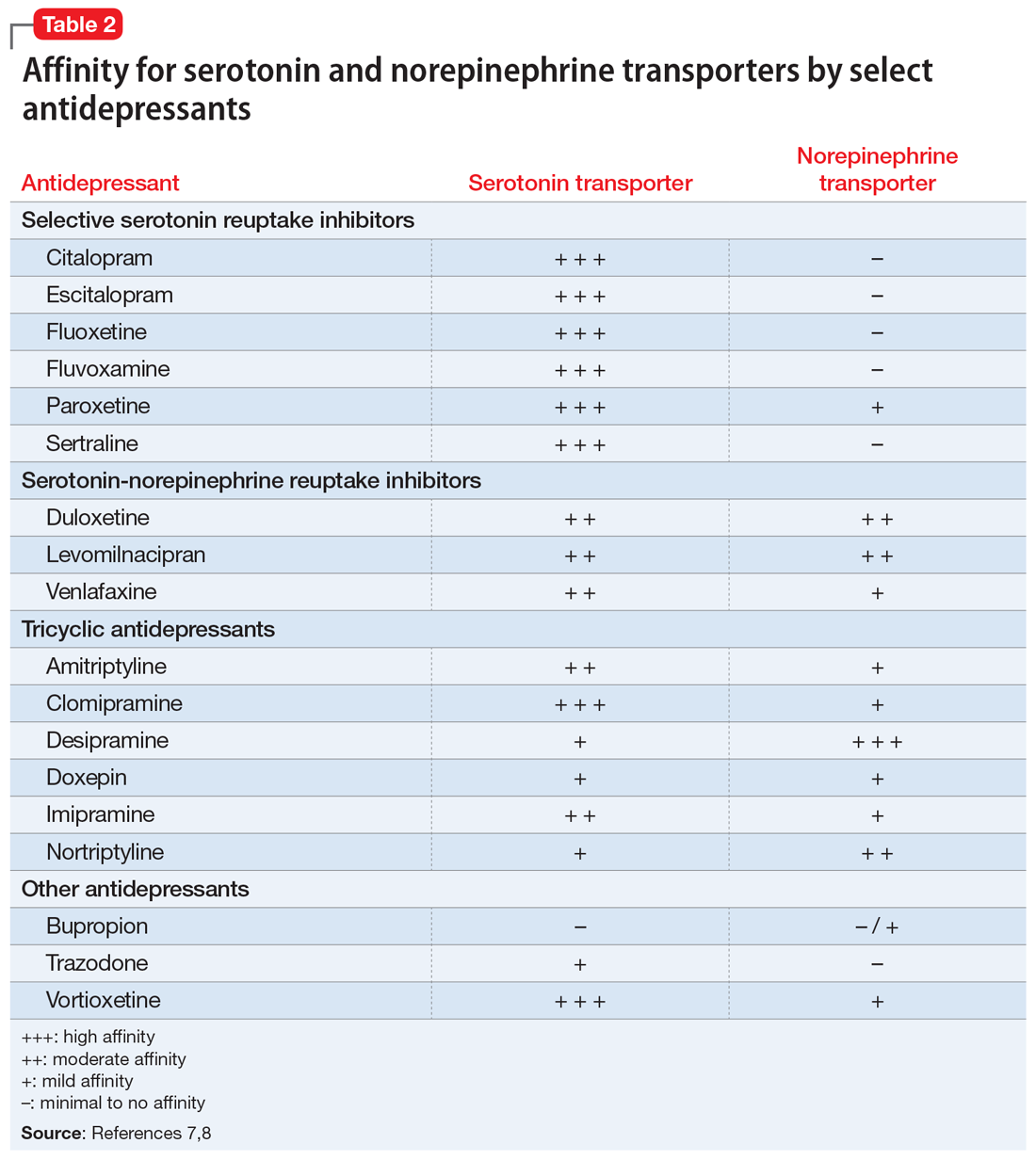

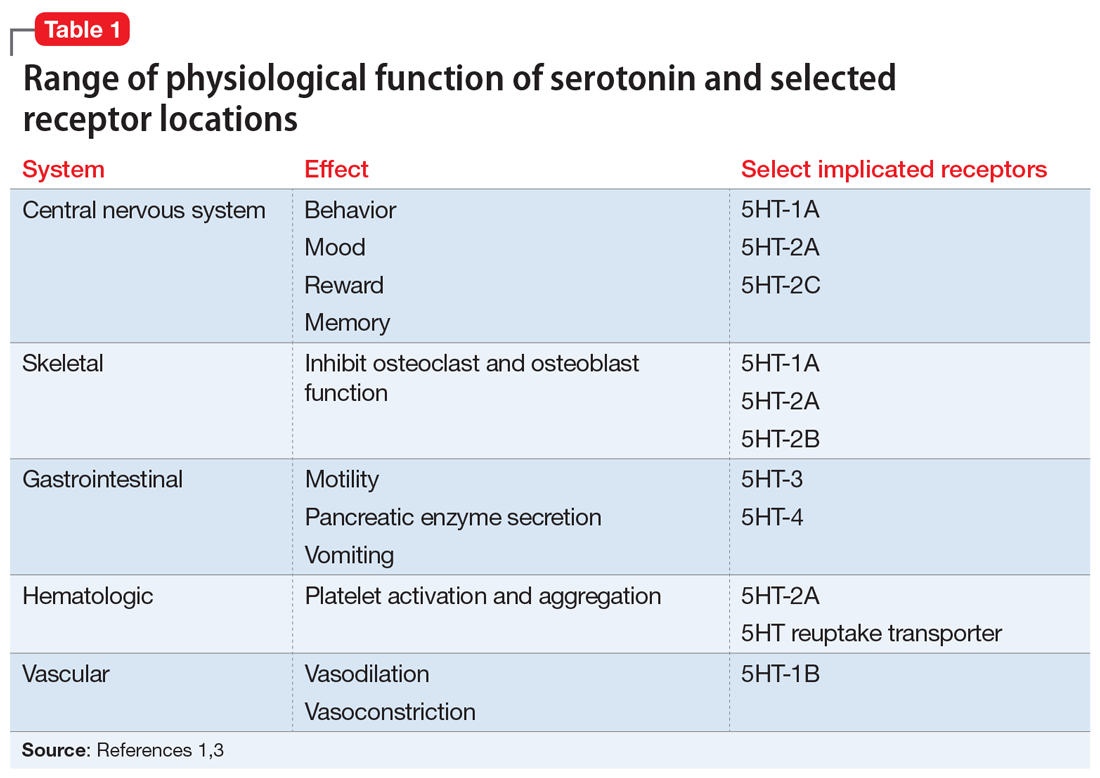

Serotonergic and noradrenergic strategies

Pimavanserin is FDA-approved for treatment of Parkinson’s psychosis. Its potential MOA as an adjunctive strategy for MDD may involve 5-HT2A antagonist and inverse agonist receptor activity, as well as lesser effects at the 5-HT2Creceptor.

A 2-stage, 5-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) (CLARITY; N = 207) found adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) produced a robust antidepressant effect vs placebo in patients whose depression did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the data suggested that pimavanserin also improved sleepiness (P < .0003) and daily functioning (P < .014) at Week 5.2

Unfortunately, two 6-week, Phase III RCTs (CLARITY-2 and -3; N = 298) did not find a statistically significant difference between active treatment and placebo. This was based on change in the primary outcome measure (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score) when adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) was added to an SSRI or SNRI in patients with TRD.3 There was, however, a significant difference favoring active treatment over placebo based on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity score.

Continue to: In these trials...

In these trials, pimavanserin was generally well-tolerated. The most common AEs were dry mouth, nausea, and headache. Pimavanserin has minimal activity at norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors, thus avoiding AEs associated with these receptor interactions.

Given the mixed efficacy results of existing trials, further studies are needed to clarify this agent’s overall risk/benefit in the context of TRD.

Antihypertensive medications

Emerging data suggest that some beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-inhibiting agents, and calcium antagonists are associated with a decreased incidence of depression. A large 2020 study (N = 3,747,190) used population-based Danish registries (2005 to 2015) to evaluate if any of the 41 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications were associated with the diagnosis of depressive disorder or use of antidepressants.4 These researchers found that enalapril, ramipril, amlodipine, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol (P < .001), and verapamil (P < .004) were strongly associated with a decreased risk of depression.4

Adverse effects across these different classes of antihypertensives are well characterized, can be substantial, and commonly are related to their impact on cardiovascular function (eg, hypotension). Clinically, these agents may be potential adjuncts for patients with TRD who need antihypertensive therapy. Their use and the choice of specific agent should only be determined in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) or appropriate specialist.

Glutamatergic strategies

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic and analgesic. Its MOA for treating depression appears to occur primarily through antagonist activity at the N-methyl-

Continue to: Many published studies...

Many published studies and reviews have described ketamine’s role for treating MDD. Several studies have reported that low-dose (0.5 mg/kg) IV ketamine infusions can rapidly attenuate severe episodes of MDD as well as associated suicidality. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (N = 368) comparing ketamine to placebo for acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression reported superior therapeutic effects with active treatment at 24 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days.6 The response and remission rates for ketamine were 52% and 21% at 24 hours; 48% and 24% at 72 hours; and 40% and 26% at 7 days, respectively.6

The most commonly reported AEs during the 4 hours after ketamine infusion included7:

- drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination

- blurred vision, feeling strange or unreal

- hemodynamic changes (approximately 33%)

- small but significant (P < .05) increases in psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms.

Because some individuals use ketamine recreationally, this agent also carries the risk of abuse.

Research is ongoing on strategies for long-term maintenance ketamine treatment, and the results of both short- and long-term trials will require careful scrutiny to better assess this agent’s safety and tolerability. Clinicians should first consider esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—because an intranasal formulation of this agent is FDA-approved for treating patients with TRD or MDD with suicidality when administered in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–certified setting.

Cholinergic strategies

Scopolamine is a potent muscarinic receptor antagonist used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by motion sickness or medications used during surgery. Its use for MDD is based on the theory that muscarinic receptors may be hypersensitive in mood disorders.

Continue to: Several double-blind RCTs...

Several double-blind RCTs of patients with unipolar or bipolar depression that used 3 pulsed IV infusions (4.0 mcg/kg) over 15 minutes found a rapid, robust antidepressant effect with scopolamine vs placebo.8,9 The oral formulation might also be effective, but would not have a rapid onset.

Common adverse effects of scopolamine include agitation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and cognitive clouding. Given scopolamine’s substantial AE profile, it should be considered only for patients with TRD who could also benefit from the oral formulation for the medical indications noted above, should generally be avoided in older patients, and should be prescribed in consultation with the patient’s PCP.

Botulinum toxin. This neurotoxin inhibits acetylcholine release. It is used to treat disorders characterized by abnormal muscular contraction, such as strabismus, blepharospasm, and chronic pain syndromes. Its MOA for depression may involve its paralytic effects after injection into the glabella forehead muscle (based on the facial feedback hypothesis), as well as modulation of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.

In several small trials, injectable botulinum toxin type A (BTA) (29 units) demonstrated antidepressant effects. A recent review that considered 6 trials (N = 235; 4 of the 6 studies were RCTs, 3 of which were rated as high quality) concluded that BTA may be a promising treatment for MDD.10 Limitations of this review included lack of a priori hypotheses, small sample sizes, gender bias, and difficulty in blinding.

In clinical trials, the most common AEs included local irritation at the injection site and transient headache. This agent’s relatively mild AE profile and possible overlap when used for some of the medical indications noted above opens its potential use as an adjunct in patients with comorbid TRD.

Continue to: Endocrine strategies

Endocrine strategies

Mifepristone (RU486). This anti-glucocorticoid receptor antagonist is used as an abortifacient. Based on the theory that hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD with psychotic features (psychotic depression), this agent has been studied as a treatment for this indication.

An analysis of 5 double-blind RCTs (N = 1,460) found that 7 days of mifepristone, 1,200 mg/d, was superior to placebo (P < .004) in reducing psychotic symptoms of depression.11 Plasma concentrations ≥1,600 ng/mL may be required to maximize benefit.11

Overall, this agent demonstrated a good safety profile in clinical trials, with treatment-emergent AEs reported in 556 (66.7%) patients who received mifepristone vs 386 (61.6%) patients who received placebo.11 Common AEs included gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, headache, and dizziness. However, 3 deaths occurred: 2 patients who received mifepristone and 1 patient who received placebo. Given this potential for a fatal outcome, clinicians should first consider prescribing an adjunctive antipsychotic agent or electroconvulsive therapy.

Estrogens. These hormones are important for sexual and reproductive development and are used to treat various sexual/reproductive disorders, primarily in women. Their role in treating depression is based on the observation that perimenopause is accompanied by an increased risk of new and recurrent depression coincident with declining ovarian function.

Evidence supports the antidepressant efficacy of transdermal estradiol plus progesterone for perimenopausal depression, but not for postmenopausal depression.12-14 However, estrogens carry significant risks that must be carefully considered in relationship to their potential benefits. These risks include:

- vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea

- fibroid enlargement

- galactorrhea

- ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer

- deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism

- hypertension, chest pain, myocardial infarction, stroke.

Continue to: The use of estrogens...

The use of estrogens as an adjunctive therapy for women with treatment-resistant perimenopausal depression should only be undertaken when standard strategies have failed, and in consultation with an endocrine specialist who can monitor for potentially serious AEs.

Opioid medications

Buprenorphine is used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) as well as acute and chronic pain. The opioid system is involved in the regulation of mood and may be an appropriate target for novel antidepressants. The use of buprenorphine in combination with samidorphan (a preferential mu-opioid receptor antagonist) has shown initial promise for TRD while minimizing abuse potential.

Although earlier results were mixed, a pooled analysis of 2 recent large RCTs (N = 760) of patients with MDD who had not responded to antidepressants reported greater reduction in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores from baseline for active treatment (buprenorphine/samidorphan; 2 mg/2 mg) vs placebo at multiple timepoints, including end of treatment (-1.8; P < .010).15

The most common AEs included nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, somnolence, fatigue, and sedation. There was minimal evidence of abuse, dependence, or opioid withdrawal. Due to the opioid crisis in the United States, the resulting relaxation of regulations regarding prescribing buprenorphine, and the high rates of depression among patients with OUD, buprenorphine/samidorphan, which is an investigational agent that is not FDA-approved, may be particularly helpful for patients with OUD who also experience comorbid TRD.

Antioxidant agents

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an amino acid that can treat acetaminophen toxicity and moderate hepatic damage by increasing glutathione levels. Glutathione is also the primary antioxidant in the CNS. NAC may protect against oxidative stress, chelate heavy metals, reduce inflammation, protect against mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance neurogenesis, all potential pathophysiological processes that may contribute to depression.16

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (N = 574) considered patients with various depression diagnoses who were randomized to adjunctive NAC, 1,000 mg twice a day, or placebo. Over 12 to 24 weeks, there was a significantly greater improvement in mood symptoms and functionality with NAC vs placebo.16

Overall, NAC was well-tolerated. The most common AEs were GI symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints, decreased energy, and headache. While NAC has been touted as a potential adjunct therapy for several psychiatric disorders, including TRD, the evidence for benefit remains limited. Given its favorable AE profile, however, and over-the-counter availability, it remains an option for select patients. It is important to ask patients if they are already taking NAC.

Options beyond off-label medications

There are a multitude of options available for addressing TRD. Many FDA-approved medications are repurposed and prescribed off-label for other indications when the risk/benefit balance is favorable. In Part 1 of this article, we reviewed several off-label medications that have supportive controlled data for treating TRD. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional therapies for TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Bottom Line

Off-label medications that may offer benefit for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) include pimavanserin, antihypertensive agents, ketamine, scopolamine, botulinum toxin, mifepristone, estrogens, buprenorphine, and N-acetylcysteine. Although some evidence supports use of these agents as adjuncts for TRD, an individualized risk/benefit analysis is required.

Related Resource

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: How to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Katerzia, Norvasc

Atenolol • Tenormin

Bisoprolol • Zebeta

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Carvedilol • Coreg

Enalapril • Vasotec

Esketamine • Spravato

Estradiol transdermal • Estraderm

Ketamine • Ketalar

Mifepristone • Mifeprex

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Progesterone • Prometrium

Propranolol • Inderal

Ramipril • Altace

Verapamil • Calan, Verelan

1. Fava M, Dirks B, Freeman M, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive pimavanserin in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to therapy (CLARITY). J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6):19m12928.

2. Jha MK, Fava M, Freeman MP, et al. Effect of adjunctive pimavanserin on sleep/wakefulness in patients with major depressive disorder: secondary analysis from CLARITY. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13425.

3. ACADIA Pharmaceuticals announces top-line results from the Phase 3 CLARITY study evaluating pimavanserin for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. News release. Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. Published July 20, 2020. https://ir.acadia-pharm.com/news-releases/news-release-details/acadia-pharmaceuticals-announces-top-line-results-phase-3-0

4. Kessing LV, Rytgaard HC, Ekstrom CT, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of depression: a nationwide population-based study. Hypertension. 2020;76(4):1263-1279.

5. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

6. Han Y, Chen J, Zou D, et al. Efficacy of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2859-2867.

7. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

8. Hasselmann, H. Scopolamine and depression: a role for muscarinic antagonism? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(4):673-683.

9. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

10. Stearns TP, Shad MU, Guzman GC. Glabellar botulinum toxin injections in major depressive disorder: a critical review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5): 18r02298.

11. Block TS, Kushner H, Kalin N, et al. Combined analysis of mifepristone for psychotic depression: plasma levels associated with clinical response. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(1):46-54.

12. Rubinow DR, Johnson SL, Schmidt PJ, et al. Efficacy of estradiol in perimenopausal depression: so much promise and so few answers. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):539-549.

13. Schmidt PJ, Ben Dor R, Martinez PE, et al. Effects of estradiol withdrawal on mood in women with past perimenopausal depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):714-726.

14. Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, et al. Efficacy of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone in the prevention of depressive symptoms in the menopause transition: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):149-157.

15. Fava M, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Opioid system modulation with buprenorphine/samidorphan combination for major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1580-1591.

16. Fernandes BS, Dean OM, Dodd S, et al. N-Acetylcysteine in depressive symptoms and functionality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):e457-466.

Presently, FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies (eg, lithium, thyroid supplementation, stimulants, second-generation antipsychotics) for major depressive disorder (MDD) often produce less-than-desired outcomes while carrying a potentially substantial safety and tolerability burden. The lack of clinically useful and individual-based biomarkers (eg, genetic, neurophysiological, imaging) is a major obstacle to enhancing treatment efficacy and/or decreasing associated adverse effects (AEs). While the discovery of such tools is being aggressively pursued and ultimately will facilitate a more precision-based choice of therapy, empirical strategies remain our primary approach.

In controlled trials, several nontraditional treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have shown promise. These include “repurposed” (off-label) medications, herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Importantly, some nontraditional treatments also demonstrate AEs (Table1-16). With a careful consideration of the risk/benefit balance, this article reviews some of the better-studied treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). In Part 1, we will examine off-label medications. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional approaches to TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

We believe this review will help clinicians who need to formulate a different approach after their patient with depression is not helped by traditional first-, second-, and third-line treatments. The potential options discussed in Part 1 of this article are categorized based on their putative mechanism of action (MOA) for depression.

Serotonergic and noradrenergic strategies

Pimavanserin is FDA-approved for treatment of Parkinson’s psychosis. Its potential MOA as an adjunctive strategy for MDD may involve 5-HT2A antagonist and inverse agonist receptor activity, as well as lesser effects at the 5-HT2Creceptor.

A 2-stage, 5-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) (CLARITY; N = 207) found adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) produced a robust antidepressant effect vs placebo in patients whose depression did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the data suggested that pimavanserin also improved sleepiness (P < .0003) and daily functioning (P < .014) at Week 5.2

Unfortunately, two 6-week, Phase III RCTs (CLARITY-2 and -3; N = 298) did not find a statistically significant difference between active treatment and placebo. This was based on change in the primary outcome measure (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score) when adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) was added to an SSRI or SNRI in patients with TRD.3 There was, however, a significant difference favoring active treatment over placebo based on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity score.

Continue to: In these trials...

In these trials, pimavanserin was generally well-tolerated. The most common AEs were dry mouth, nausea, and headache. Pimavanserin has minimal activity at norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors, thus avoiding AEs associated with these receptor interactions.

Given the mixed efficacy results of existing trials, further studies are needed to clarify this agent’s overall risk/benefit in the context of TRD.

Antihypertensive medications

Emerging data suggest that some beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-inhibiting agents, and calcium antagonists are associated with a decreased incidence of depression. A large 2020 study (N = 3,747,190) used population-based Danish registries (2005 to 2015) to evaluate if any of the 41 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications were associated with the diagnosis of depressive disorder or use of antidepressants.4 These researchers found that enalapril, ramipril, amlodipine, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol (P < .001), and verapamil (P < .004) were strongly associated with a decreased risk of depression.4

Adverse effects across these different classes of antihypertensives are well characterized, can be substantial, and commonly are related to their impact on cardiovascular function (eg, hypotension). Clinically, these agents may be potential adjuncts for patients with TRD who need antihypertensive therapy. Their use and the choice of specific agent should only be determined in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) or appropriate specialist.

Glutamatergic strategies

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic and analgesic. Its MOA for treating depression appears to occur primarily through antagonist activity at the N-methyl-

Continue to: Many published studies...

Many published studies and reviews have described ketamine’s role for treating MDD. Several studies have reported that low-dose (0.5 mg/kg) IV ketamine infusions can rapidly attenuate severe episodes of MDD as well as associated suicidality. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (N = 368) comparing ketamine to placebo for acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression reported superior therapeutic effects with active treatment at 24 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days.6 The response and remission rates for ketamine were 52% and 21% at 24 hours; 48% and 24% at 72 hours; and 40% and 26% at 7 days, respectively.6

The most commonly reported AEs during the 4 hours after ketamine infusion included7:

- drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination

- blurred vision, feeling strange or unreal

- hemodynamic changes (approximately 33%)

- small but significant (P < .05) increases in psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms.

Because some individuals use ketamine recreationally, this agent also carries the risk of abuse.

Research is ongoing on strategies for long-term maintenance ketamine treatment, and the results of both short- and long-term trials will require careful scrutiny to better assess this agent’s safety and tolerability. Clinicians should first consider esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—because an intranasal formulation of this agent is FDA-approved for treating patients with TRD or MDD with suicidality when administered in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–certified setting.

Cholinergic strategies

Scopolamine is a potent muscarinic receptor antagonist used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by motion sickness or medications used during surgery. Its use for MDD is based on the theory that muscarinic receptors may be hypersensitive in mood disorders.

Continue to: Several double-blind RCTs...

Several double-blind RCTs of patients with unipolar or bipolar depression that used 3 pulsed IV infusions (4.0 mcg/kg) over 15 minutes found a rapid, robust antidepressant effect with scopolamine vs placebo.8,9 The oral formulation might also be effective, but would not have a rapid onset.

Common adverse effects of scopolamine include agitation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and cognitive clouding. Given scopolamine’s substantial AE profile, it should be considered only for patients with TRD who could also benefit from the oral formulation for the medical indications noted above, should generally be avoided in older patients, and should be prescribed in consultation with the patient’s PCP.

Botulinum toxin. This neurotoxin inhibits acetylcholine release. It is used to treat disorders characterized by abnormal muscular contraction, such as strabismus, blepharospasm, and chronic pain syndromes. Its MOA for depression may involve its paralytic effects after injection into the glabella forehead muscle (based on the facial feedback hypothesis), as well as modulation of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.

In several small trials, injectable botulinum toxin type A (BTA) (29 units) demonstrated antidepressant effects. A recent review that considered 6 trials (N = 235; 4 of the 6 studies were RCTs, 3 of which were rated as high quality) concluded that BTA may be a promising treatment for MDD.10 Limitations of this review included lack of a priori hypotheses, small sample sizes, gender bias, and difficulty in blinding.

In clinical trials, the most common AEs included local irritation at the injection site and transient headache. This agent’s relatively mild AE profile and possible overlap when used for some of the medical indications noted above opens its potential use as an adjunct in patients with comorbid TRD.

Continue to: Endocrine strategies

Endocrine strategies

Mifepristone (RU486). This anti-glucocorticoid receptor antagonist is used as an abortifacient. Based on the theory that hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD with psychotic features (psychotic depression), this agent has been studied as a treatment for this indication.

An analysis of 5 double-blind RCTs (N = 1,460) found that 7 days of mifepristone, 1,200 mg/d, was superior to placebo (P < .004) in reducing psychotic symptoms of depression.11 Plasma concentrations ≥1,600 ng/mL may be required to maximize benefit.11

Overall, this agent demonstrated a good safety profile in clinical trials, with treatment-emergent AEs reported in 556 (66.7%) patients who received mifepristone vs 386 (61.6%) patients who received placebo.11 Common AEs included gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, headache, and dizziness. However, 3 deaths occurred: 2 patients who received mifepristone and 1 patient who received placebo. Given this potential for a fatal outcome, clinicians should first consider prescribing an adjunctive antipsychotic agent or electroconvulsive therapy.

Estrogens. These hormones are important for sexual and reproductive development and are used to treat various sexual/reproductive disorders, primarily in women. Their role in treating depression is based on the observation that perimenopause is accompanied by an increased risk of new and recurrent depression coincident with declining ovarian function.

Evidence supports the antidepressant efficacy of transdermal estradiol plus progesterone for perimenopausal depression, but not for postmenopausal depression.12-14 However, estrogens carry significant risks that must be carefully considered in relationship to their potential benefits. These risks include:

- vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea

- fibroid enlargement

- galactorrhea

- ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer

- deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism

- hypertension, chest pain, myocardial infarction, stroke.

Continue to: The use of estrogens...

The use of estrogens as an adjunctive therapy for women with treatment-resistant perimenopausal depression should only be undertaken when standard strategies have failed, and in consultation with an endocrine specialist who can monitor for potentially serious AEs.

Opioid medications

Buprenorphine is used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) as well as acute and chronic pain. The opioid system is involved in the regulation of mood and may be an appropriate target for novel antidepressants. The use of buprenorphine in combination with samidorphan (a preferential mu-opioid receptor antagonist) has shown initial promise for TRD while minimizing abuse potential.

Although earlier results were mixed, a pooled analysis of 2 recent large RCTs (N = 760) of patients with MDD who had not responded to antidepressants reported greater reduction in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores from baseline for active treatment (buprenorphine/samidorphan; 2 mg/2 mg) vs placebo at multiple timepoints, including end of treatment (-1.8; P < .010).15

The most common AEs included nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, somnolence, fatigue, and sedation. There was minimal evidence of abuse, dependence, or opioid withdrawal. Due to the opioid crisis in the United States, the resulting relaxation of regulations regarding prescribing buprenorphine, and the high rates of depression among patients with OUD, buprenorphine/samidorphan, which is an investigational agent that is not FDA-approved, may be particularly helpful for patients with OUD who also experience comorbid TRD.

Antioxidant agents

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an amino acid that can treat acetaminophen toxicity and moderate hepatic damage by increasing glutathione levels. Glutathione is also the primary antioxidant in the CNS. NAC may protect against oxidative stress, chelate heavy metals, reduce inflammation, protect against mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance neurogenesis, all potential pathophysiological processes that may contribute to depression.16

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (N = 574) considered patients with various depression diagnoses who were randomized to adjunctive NAC, 1,000 mg twice a day, or placebo. Over 12 to 24 weeks, there was a significantly greater improvement in mood symptoms and functionality with NAC vs placebo.16

Overall, NAC was well-tolerated. The most common AEs were GI symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints, decreased energy, and headache. While NAC has been touted as a potential adjunct therapy for several psychiatric disorders, including TRD, the evidence for benefit remains limited. Given its favorable AE profile, however, and over-the-counter availability, it remains an option for select patients. It is important to ask patients if they are already taking NAC.

Options beyond off-label medications

There are a multitude of options available for addressing TRD. Many FDA-approved medications are repurposed and prescribed off-label for other indications when the risk/benefit balance is favorable. In Part 1 of this article, we reviewed several off-label medications that have supportive controlled data for treating TRD. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional therapies for TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Bottom Line

Off-label medications that may offer benefit for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) include pimavanserin, antihypertensive agents, ketamine, scopolamine, botulinum toxin, mifepristone, estrogens, buprenorphine, and N-acetylcysteine. Although some evidence supports use of these agents as adjuncts for TRD, an individualized risk/benefit analysis is required.

Related Resource

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: How to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Katerzia, Norvasc

Atenolol • Tenormin

Bisoprolol • Zebeta

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Carvedilol • Coreg

Enalapril • Vasotec

Esketamine • Spravato

Estradiol transdermal • Estraderm

Ketamine • Ketalar

Mifepristone • Mifeprex

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Progesterone • Prometrium

Propranolol • Inderal

Ramipril • Altace

Verapamil • Calan, Verelan

Presently, FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies (eg, lithium, thyroid supplementation, stimulants, second-generation antipsychotics) for major depressive disorder (MDD) often produce less-than-desired outcomes while carrying a potentially substantial safety and tolerability burden. The lack of clinically useful and individual-based biomarkers (eg, genetic, neurophysiological, imaging) is a major obstacle to enhancing treatment efficacy and/or decreasing associated adverse effects (AEs). While the discovery of such tools is being aggressively pursued and ultimately will facilitate a more precision-based choice of therapy, empirical strategies remain our primary approach.

In controlled trials, several nontraditional treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have shown promise. These include “repurposed” (off-label) medications, herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Importantly, some nontraditional treatments also demonstrate AEs (Table1-16). With a careful consideration of the risk/benefit balance, this article reviews some of the better-studied treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). In Part 1, we will examine off-label medications. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional approaches to TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

We believe this review will help clinicians who need to formulate a different approach after their patient with depression is not helped by traditional first-, second-, and third-line treatments. The potential options discussed in Part 1 of this article are categorized based on their putative mechanism of action (MOA) for depression.

Serotonergic and noradrenergic strategies

Pimavanserin is FDA-approved for treatment of Parkinson’s psychosis. Its potential MOA as an adjunctive strategy for MDD may involve 5-HT2A antagonist and inverse agonist receptor activity, as well as lesser effects at the 5-HT2Creceptor.

A 2-stage, 5-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) (CLARITY; N = 207) found adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) produced a robust antidepressant effect vs placebo in patients whose depression did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the data suggested that pimavanserin also improved sleepiness (P < .0003) and daily functioning (P < .014) at Week 5.2

Unfortunately, two 6-week, Phase III RCTs (CLARITY-2 and -3; N = 298) did not find a statistically significant difference between active treatment and placebo. This was based on change in the primary outcome measure (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score) when adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) was added to an SSRI or SNRI in patients with TRD.3 There was, however, a significant difference favoring active treatment over placebo based on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity score.

Continue to: In these trials...

In these trials, pimavanserin was generally well-tolerated. The most common AEs were dry mouth, nausea, and headache. Pimavanserin has minimal activity at norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors, thus avoiding AEs associated with these receptor interactions.

Given the mixed efficacy results of existing trials, further studies are needed to clarify this agent’s overall risk/benefit in the context of TRD.

Antihypertensive medications

Emerging data suggest that some beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-inhibiting agents, and calcium antagonists are associated with a decreased incidence of depression. A large 2020 study (N = 3,747,190) used population-based Danish registries (2005 to 2015) to evaluate if any of the 41 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications were associated with the diagnosis of depressive disorder or use of antidepressants.4 These researchers found that enalapril, ramipril, amlodipine, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol (P < .001), and verapamil (P < .004) were strongly associated with a decreased risk of depression.4

Adverse effects across these different classes of antihypertensives are well characterized, can be substantial, and commonly are related to their impact on cardiovascular function (eg, hypotension). Clinically, these agents may be potential adjuncts for patients with TRD who need antihypertensive therapy. Their use and the choice of specific agent should only be determined in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) or appropriate specialist.

Glutamatergic strategies

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic and analgesic. Its MOA for treating depression appears to occur primarily through antagonist activity at the N-methyl-

Continue to: Many published studies...

Many published studies and reviews have described ketamine’s role for treating MDD. Several studies have reported that low-dose (0.5 mg/kg) IV ketamine infusions can rapidly attenuate severe episodes of MDD as well as associated suicidality. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (N = 368) comparing ketamine to placebo for acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression reported superior therapeutic effects with active treatment at 24 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days.6 The response and remission rates for ketamine were 52% and 21% at 24 hours; 48% and 24% at 72 hours; and 40% and 26% at 7 days, respectively.6

The most commonly reported AEs during the 4 hours after ketamine infusion included7:

- drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination

- blurred vision, feeling strange or unreal

- hemodynamic changes (approximately 33%)

- small but significant (P < .05) increases in psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms.

Because some individuals use ketamine recreationally, this agent also carries the risk of abuse.

Research is ongoing on strategies for long-term maintenance ketamine treatment, and the results of both short- and long-term trials will require careful scrutiny to better assess this agent’s safety and tolerability. Clinicians should first consider esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—because an intranasal formulation of this agent is FDA-approved for treating patients with TRD or MDD with suicidality when administered in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–certified setting.

Cholinergic strategies

Scopolamine is a potent muscarinic receptor antagonist used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by motion sickness or medications used during surgery. Its use for MDD is based on the theory that muscarinic receptors may be hypersensitive in mood disorders.

Continue to: Several double-blind RCTs...

Several double-blind RCTs of patients with unipolar or bipolar depression that used 3 pulsed IV infusions (4.0 mcg/kg) over 15 minutes found a rapid, robust antidepressant effect with scopolamine vs placebo.8,9 The oral formulation might also be effective, but would not have a rapid onset.

Common adverse effects of scopolamine include agitation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and cognitive clouding. Given scopolamine’s substantial AE profile, it should be considered only for patients with TRD who could also benefit from the oral formulation for the medical indications noted above, should generally be avoided in older patients, and should be prescribed in consultation with the patient’s PCP.

Botulinum toxin. This neurotoxin inhibits acetylcholine release. It is used to treat disorders characterized by abnormal muscular contraction, such as strabismus, blepharospasm, and chronic pain syndromes. Its MOA for depression may involve its paralytic effects after injection into the glabella forehead muscle (based on the facial feedback hypothesis), as well as modulation of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.

In several small trials, injectable botulinum toxin type A (BTA) (29 units) demonstrated antidepressant effects. A recent review that considered 6 trials (N = 235; 4 of the 6 studies were RCTs, 3 of which were rated as high quality) concluded that BTA may be a promising treatment for MDD.10 Limitations of this review included lack of a priori hypotheses, small sample sizes, gender bias, and difficulty in blinding.

In clinical trials, the most common AEs included local irritation at the injection site and transient headache. This agent’s relatively mild AE profile and possible overlap when used for some of the medical indications noted above opens its potential use as an adjunct in patients with comorbid TRD.

Continue to: Endocrine strategies

Endocrine strategies

Mifepristone (RU486). This anti-glucocorticoid receptor antagonist is used as an abortifacient. Based on the theory that hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD with psychotic features (psychotic depression), this agent has been studied as a treatment for this indication.

An analysis of 5 double-blind RCTs (N = 1,460) found that 7 days of mifepristone, 1,200 mg/d, was superior to placebo (P < .004) in reducing psychotic symptoms of depression.11 Plasma concentrations ≥1,600 ng/mL may be required to maximize benefit.11

Overall, this agent demonstrated a good safety profile in clinical trials, with treatment-emergent AEs reported in 556 (66.7%) patients who received mifepristone vs 386 (61.6%) patients who received placebo.11 Common AEs included gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, headache, and dizziness. However, 3 deaths occurred: 2 patients who received mifepristone and 1 patient who received placebo. Given this potential for a fatal outcome, clinicians should first consider prescribing an adjunctive antipsychotic agent or electroconvulsive therapy.

Estrogens. These hormones are important for sexual and reproductive development and are used to treat various sexual/reproductive disorders, primarily in women. Their role in treating depression is based on the observation that perimenopause is accompanied by an increased risk of new and recurrent depression coincident with declining ovarian function.

Evidence supports the antidepressant efficacy of transdermal estradiol plus progesterone for perimenopausal depression, but not for postmenopausal depression.12-14 However, estrogens carry significant risks that must be carefully considered in relationship to their potential benefits. These risks include:

- vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea

- fibroid enlargement

- galactorrhea

- ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer

- deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism

- hypertension, chest pain, myocardial infarction, stroke.

Continue to: The use of estrogens...

The use of estrogens as an adjunctive therapy for women with treatment-resistant perimenopausal depression should only be undertaken when standard strategies have failed, and in consultation with an endocrine specialist who can monitor for potentially serious AEs.

Opioid medications

Buprenorphine is used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) as well as acute and chronic pain. The opioid system is involved in the regulation of mood and may be an appropriate target for novel antidepressants. The use of buprenorphine in combination with samidorphan (a preferential mu-opioid receptor antagonist) has shown initial promise for TRD while minimizing abuse potential.

Although earlier results were mixed, a pooled analysis of 2 recent large RCTs (N = 760) of patients with MDD who had not responded to antidepressants reported greater reduction in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores from baseline for active treatment (buprenorphine/samidorphan; 2 mg/2 mg) vs placebo at multiple timepoints, including end of treatment (-1.8; P < .010).15

The most common AEs included nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, somnolence, fatigue, and sedation. There was minimal evidence of abuse, dependence, or opioid withdrawal. Due to the opioid crisis in the United States, the resulting relaxation of regulations regarding prescribing buprenorphine, and the high rates of depression among patients with OUD, buprenorphine/samidorphan, which is an investigational agent that is not FDA-approved, may be particularly helpful for patients with OUD who also experience comorbid TRD.

Antioxidant agents

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an amino acid that can treat acetaminophen toxicity and moderate hepatic damage by increasing glutathione levels. Glutathione is also the primary antioxidant in the CNS. NAC may protect against oxidative stress, chelate heavy metals, reduce inflammation, protect against mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance neurogenesis, all potential pathophysiological processes that may contribute to depression.16

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (N = 574) considered patients with various depression diagnoses who were randomized to adjunctive NAC, 1,000 mg twice a day, or placebo. Over 12 to 24 weeks, there was a significantly greater improvement in mood symptoms and functionality with NAC vs placebo.16

Overall, NAC was well-tolerated. The most common AEs were GI symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints, decreased energy, and headache. While NAC has been touted as a potential adjunct therapy for several psychiatric disorders, including TRD, the evidence for benefit remains limited. Given its favorable AE profile, however, and over-the-counter availability, it remains an option for select patients. It is important to ask patients if they are already taking NAC.

Options beyond off-label medications

There are a multitude of options available for addressing TRD. Many FDA-approved medications are repurposed and prescribed off-label for other indications when the risk/benefit balance is favorable. In Part 1 of this article, we reviewed several off-label medications that have supportive controlled data for treating TRD. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional therapies for TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Bottom Line

Off-label medications that may offer benefit for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) include pimavanserin, antihypertensive agents, ketamine, scopolamine, botulinum toxin, mifepristone, estrogens, buprenorphine, and N-acetylcysteine. Although some evidence supports use of these agents as adjuncts for TRD, an individualized risk/benefit analysis is required.

Related Resource

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: How to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Katerzia, Norvasc

Atenolol • Tenormin

Bisoprolol • Zebeta

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Carvedilol • Coreg

Enalapril • Vasotec

Esketamine • Spravato

Estradiol transdermal • Estraderm

Ketamine • Ketalar

Mifepristone • Mifeprex

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Progesterone • Prometrium

Propranolol • Inderal

Ramipril • Altace

Verapamil • Calan, Verelan

1. Fava M, Dirks B, Freeman M, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive pimavanserin in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to therapy (CLARITY). J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6):19m12928.

2. Jha MK, Fava M, Freeman MP, et al. Effect of adjunctive pimavanserin on sleep/wakefulness in patients with major depressive disorder: secondary analysis from CLARITY. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13425.

3. ACADIA Pharmaceuticals announces top-line results from the Phase 3 CLARITY study evaluating pimavanserin for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. News release. Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. Published July 20, 2020. https://ir.acadia-pharm.com/news-releases/news-release-details/acadia-pharmaceuticals-announces-top-line-results-phase-3-0

4. Kessing LV, Rytgaard HC, Ekstrom CT, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of depression: a nationwide population-based study. Hypertension. 2020;76(4):1263-1279.

5. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

6. Han Y, Chen J, Zou D, et al. Efficacy of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2859-2867.

7. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

8. Hasselmann, H. Scopolamine and depression: a role for muscarinic antagonism? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(4):673-683.

9. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

10. Stearns TP, Shad MU, Guzman GC. Glabellar botulinum toxin injections in major depressive disorder: a critical review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5): 18r02298.

11. Block TS, Kushner H, Kalin N, et al. Combined analysis of mifepristone for psychotic depression: plasma levels associated with clinical response. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(1):46-54.

12. Rubinow DR, Johnson SL, Schmidt PJ, et al. Efficacy of estradiol in perimenopausal depression: so much promise and so few answers. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):539-549.

13. Schmidt PJ, Ben Dor R, Martinez PE, et al. Effects of estradiol withdrawal on mood in women with past perimenopausal depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):714-726.

14. Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, et al. Efficacy of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone in the prevention of depressive symptoms in the menopause transition: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):149-157.

15. Fava M, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Opioid system modulation with buprenorphine/samidorphan combination for major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1580-1591.

16. Fernandes BS, Dean OM, Dodd S, et al. N-Acetylcysteine in depressive symptoms and functionality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):e457-466.

1. Fava M, Dirks B, Freeman M, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive pimavanserin in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to therapy (CLARITY). J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6):19m12928.

2. Jha MK, Fava M, Freeman MP, et al. Effect of adjunctive pimavanserin on sleep/wakefulness in patients with major depressive disorder: secondary analysis from CLARITY. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13425.

3. ACADIA Pharmaceuticals announces top-line results from the Phase 3 CLARITY study evaluating pimavanserin for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. News release. Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. Published July 20, 2020. https://ir.acadia-pharm.com/news-releases/news-release-details/acadia-pharmaceuticals-announces-top-line-results-phase-3-0

4. Kessing LV, Rytgaard HC, Ekstrom CT, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of depression: a nationwide population-based study. Hypertension. 2020;76(4):1263-1279.

5. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

6. Han Y, Chen J, Zou D, et al. Efficacy of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2859-2867.

7. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

8. Hasselmann, H. Scopolamine and depression: a role for muscarinic antagonism? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(4):673-683.

9. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

10. Stearns TP, Shad MU, Guzman GC. Glabellar botulinum toxin injections in major depressive disorder: a critical review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5): 18r02298.

11. Block TS, Kushner H, Kalin N, et al. Combined analysis of mifepristone for psychotic depression: plasma levels associated with clinical response. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(1):46-54.

12. Rubinow DR, Johnson SL, Schmidt PJ, et al. Efficacy of estradiol in perimenopausal depression: so much promise and so few answers. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):539-549.

13. Schmidt PJ, Ben Dor R, Martinez PE, et al. Effects of estradiol withdrawal on mood in women with past perimenopausal depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):714-726.

14. Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, et al. Efficacy of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone in the prevention of depressive symptoms in the menopause transition: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):149-157.

15. Fava M, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Opioid system modulation with buprenorphine/samidorphan combination for major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1580-1591.

16. Fernandes BS, Dean OM, Dodd S, et al. N-Acetylcysteine in depressive symptoms and functionality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):e457-466.

Confidentiality and privilege: What you don’t know can hurt you

Mrs. W, age 35, presents to your clinic seeking treatment for anxiety and depression. She has no psychiatric history but reports feeling sad, overwhelmed, and stressed. Mrs. W has been married for 10 years, has 2 young children, and is currently pregnant. She recently discovered that her husband has been having an affair. Mrs. W tells you that she feels her marriage is unsalvageable and would like to ask her husband for a divorce, but worries that he will “put up a fight” and demand full custody of their children. When you ask why, she states that her husband is “pretty narcissistic” and tends to become combative when criticized or threatened, such as a recent discussion they had about his affair that ended with him concluding that if she were “sexier and more confident” he would not have cheated on her.

As Mrs. W is talking, you recall a conversation you recently overheard at a continuing medical education event. Two clinicians were discussing how their records had been subpoenaed in a child custody case, even though the patient’s mental health was not contested. You realize that Mrs. W’s situation may also fit under this exception to confidentiality or privilege. You wonder if you should have disclosed this possibility to her at the outset of your session and wonder what you should say now, because she is clearly in distress and in need of psychiatric treatment. On the other hand, you want her to be fully informed of the potential repercussions if she continues with treatment.

Confidentiality and privilege allow our patients to disclose sensitive details in a safe space. The psychiatrist’s duty is to keep the patient’s information confidential, except in limited circumstances. The patient’s privilege is their right to prevent someone in a special confidential relationship from testifying against them or releasing their private records. In certain instances, a patient may waive or be forced to waive privilege, and a psychiatrist may be compelled to testify or release treatment records to a court. This article reviews exceptions to confidentiality and privilege, focusing specifically on a little-known exception to privilege that arises in divorce and child custody cases. We discuss relevant legislation and provide recommendations for psychiatrists to better understand how to discuss these legal realities with patients who are or may go through a divorce or child custody case.

Understanding confidentiality and privilege

Confidentiality and privilege are related but distinct concepts. Confidentiality relates to the overall trusting relationship created between 2 parties, such as a physician and their patient, and the duty on the part of the trusted individual to keep information private. Privilege refers to a person’s specific legal right to prevent someone in that confidential, trusting relationship from testifying against them in court or releasing confidential records. Privilege is owned by the patient and must be asserted or waived by the patient in legal proceedings. The concepts of confidentiality and privilege are crucial in creating an open, candid therapeutic environment. Many courts, including the US Supreme Court,1 have recognized the importance of confidentiality and privilege in establishing a positive therapeutic relationship between a psychotherapist and a patient. Without confidentiality and privilege, patients would be less likely to share sensitive yet clinically important information.

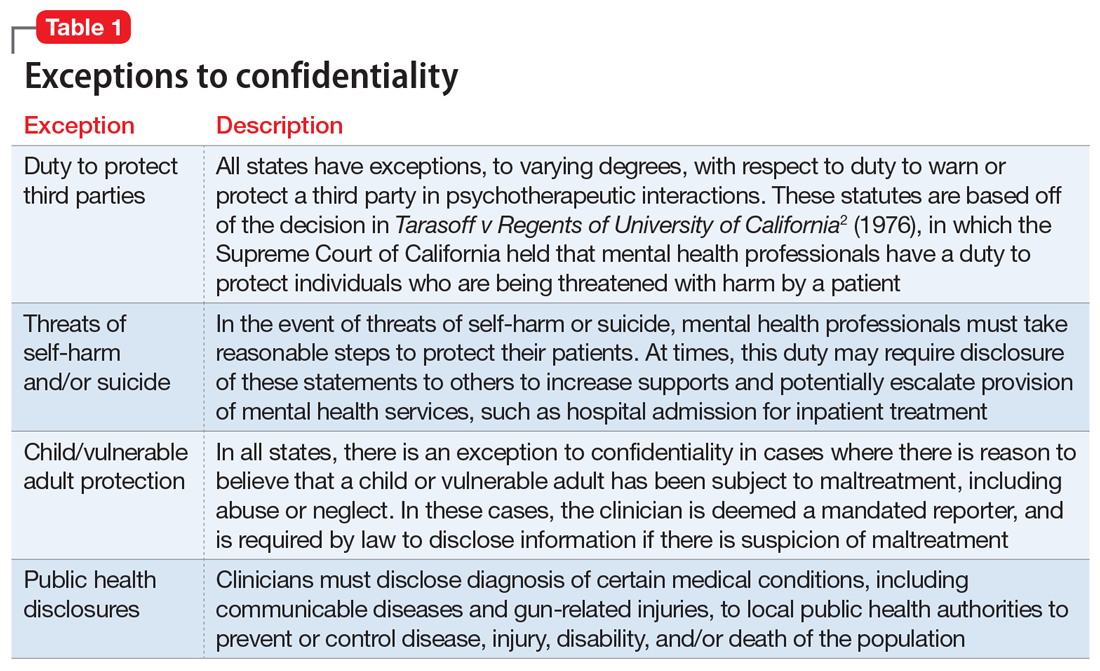

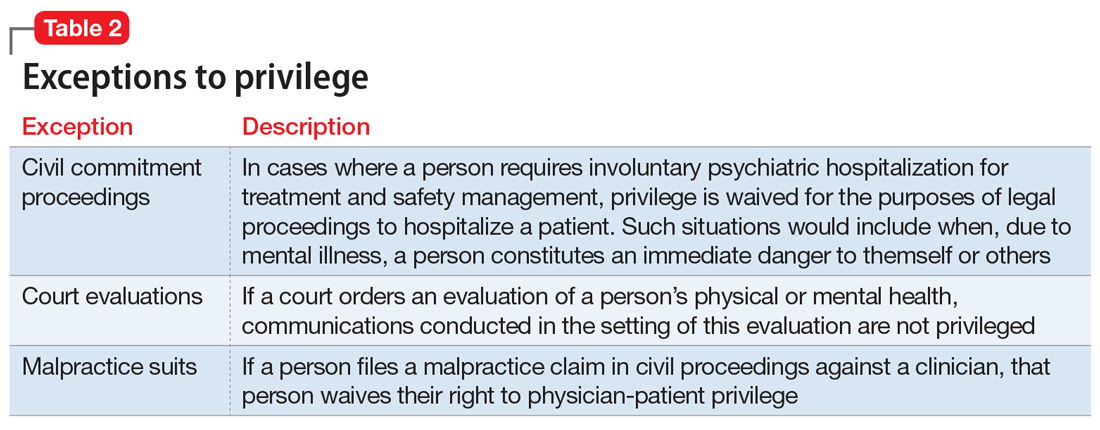

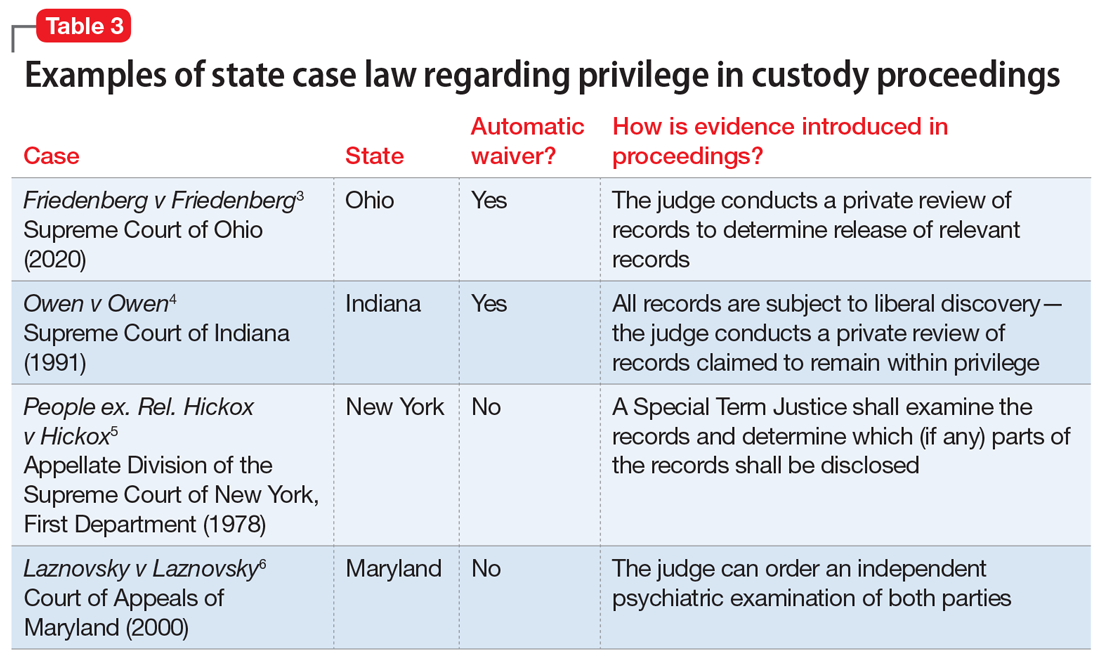

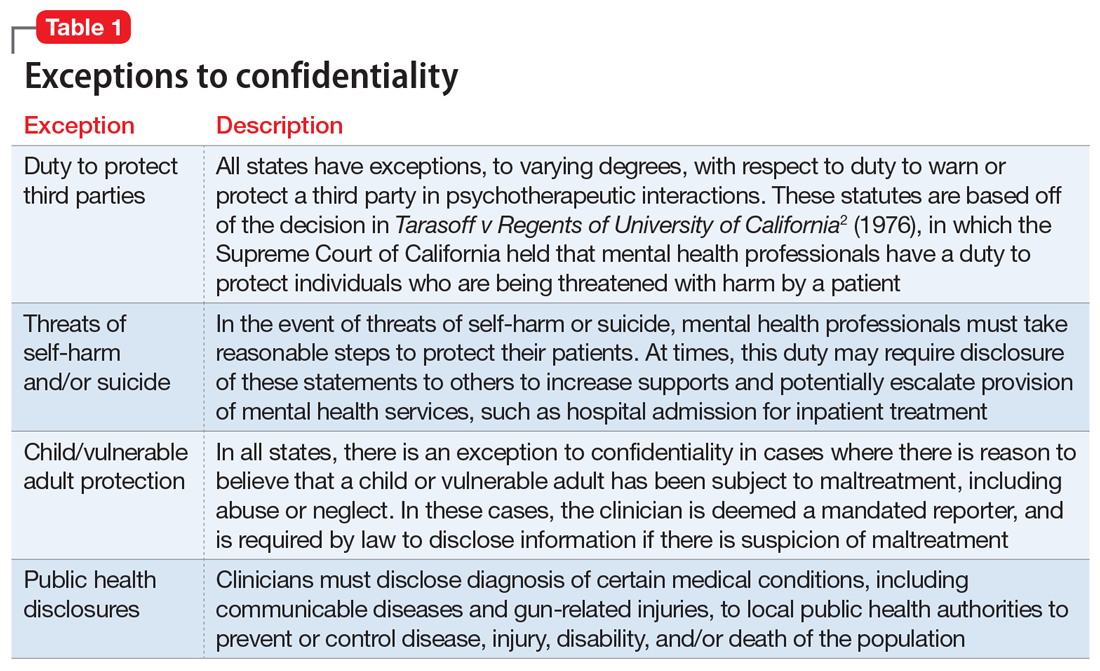

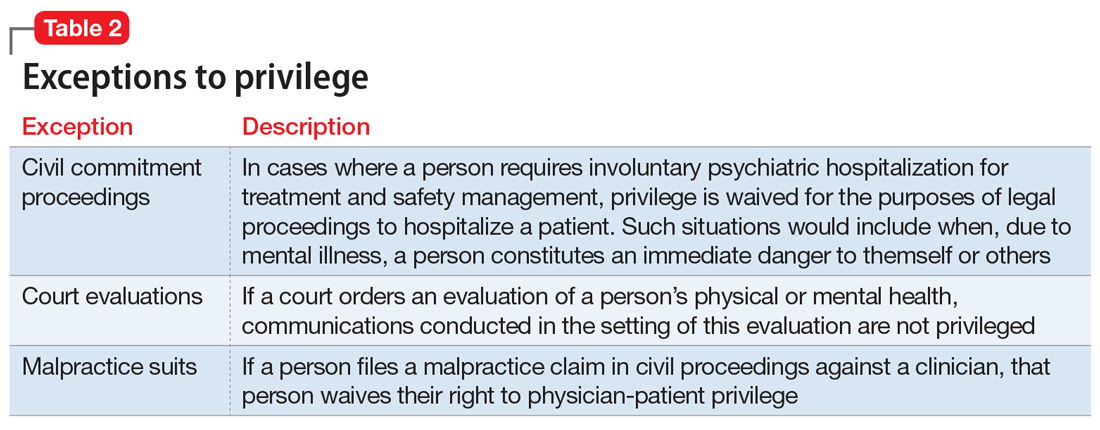

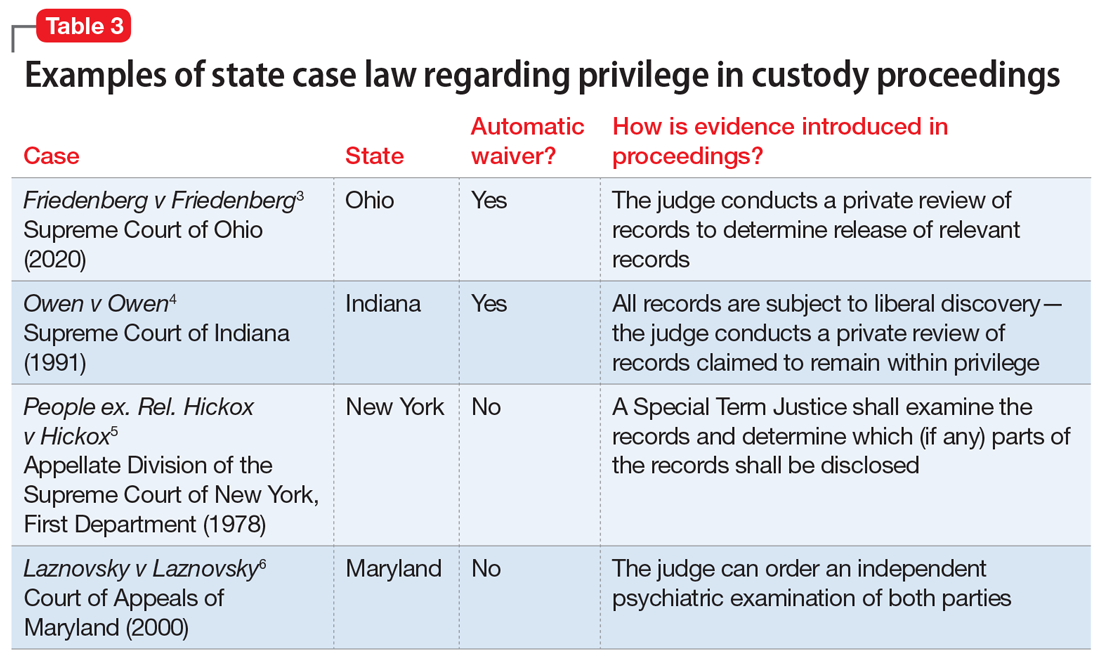

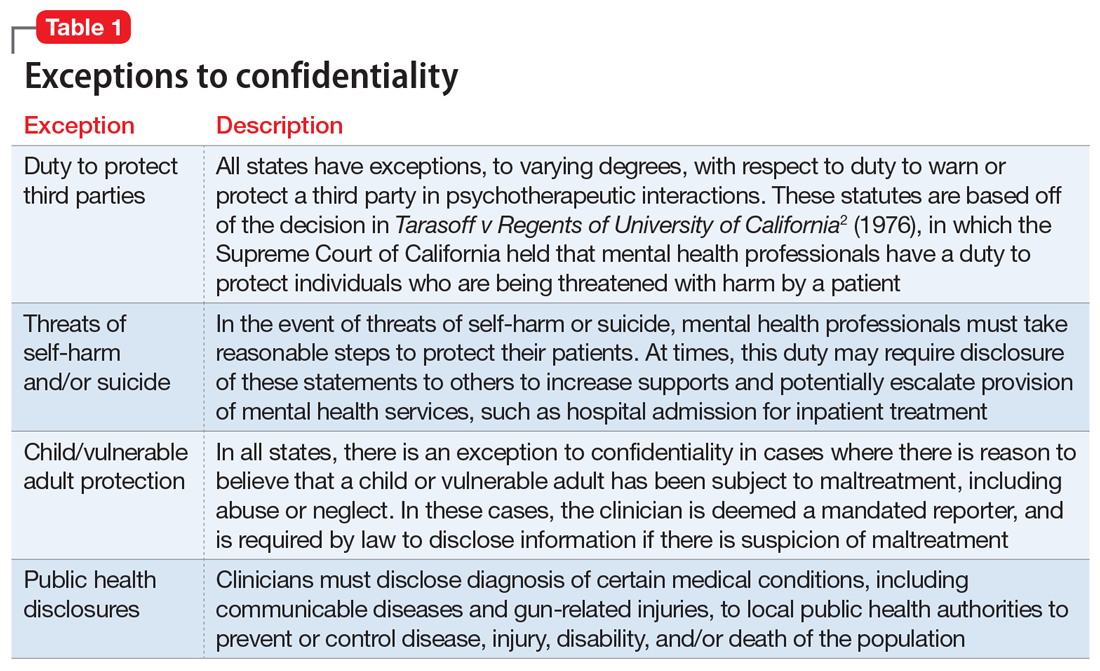

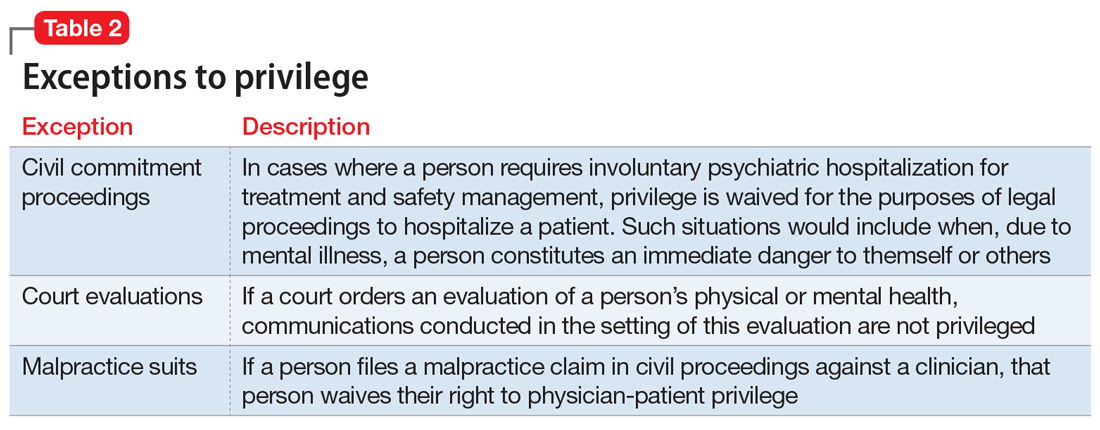

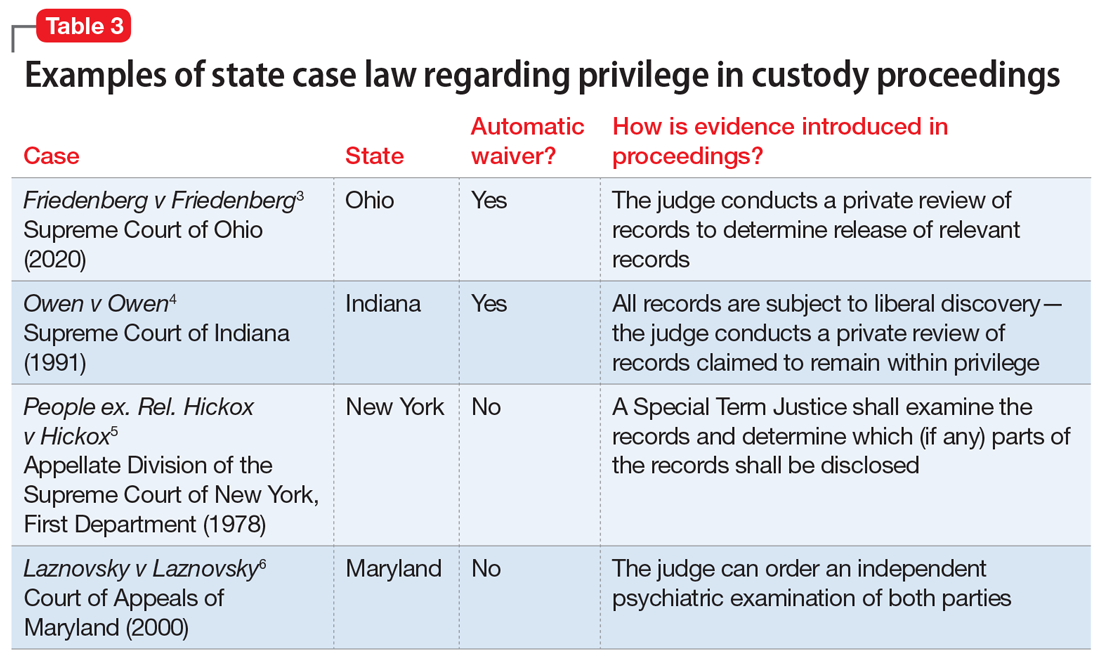

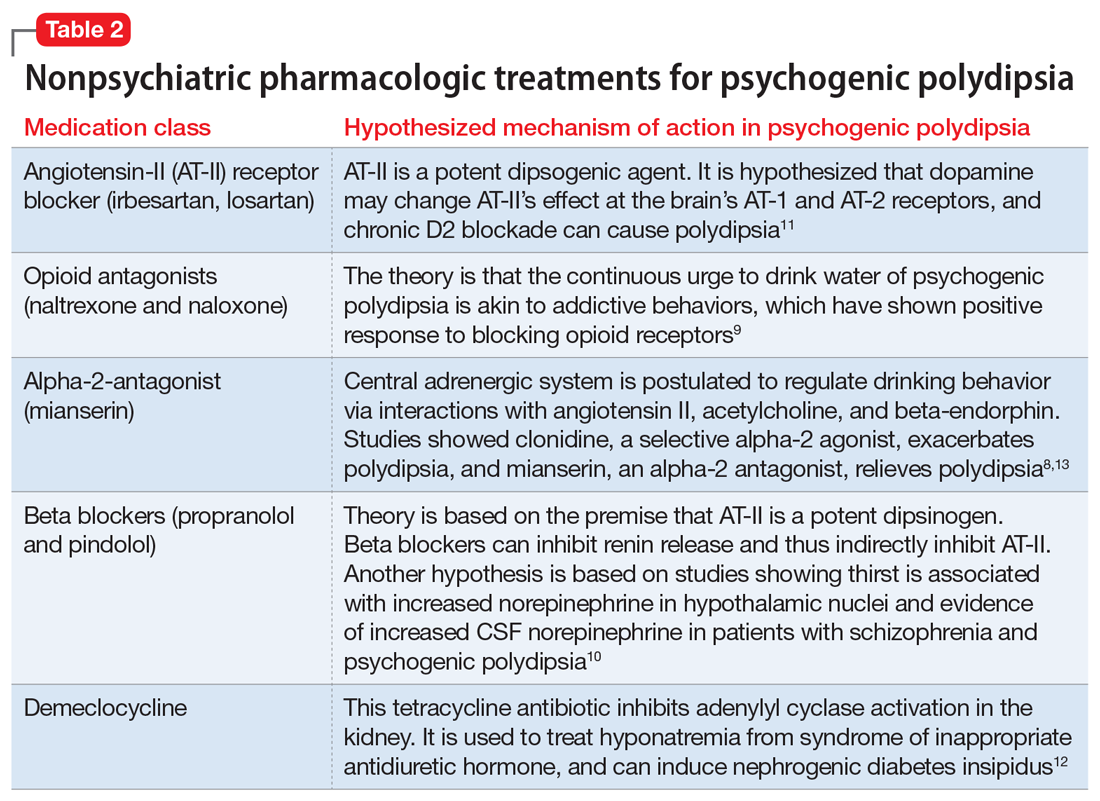

Commonly encountered exceptions to confidentiality (Table 12) and privilege (Table 2) exist in medical practice. Psychiatrists should discuss these exceptions with patients at the outset of clinical treatment. A little-known exception to privilege that may compel a psychiatrist to disclose confidential records can occur in child custody proceedings. In certain states, the mere filing of a child custody claim constitutes an exception to physician-patient privilege. In these states, the parent filing for divorce and custody may automatically waive privilege and thus compel disclosure of psychiatric records, even if their mental health is not in question. The following recent Ohio Supreme Court case illustrates this exception.

Friedenberg v Friedenberg (2020)

Friedenberg v Friedenberg3 addressed the issue of privilege and release of mental health treatment records in custody disputes. Belinda Torres Friedenberg and Keith Friedenberg were married with 4 minor children. Mrs. Friedenberg filed for divorce in 2016, requesting custody of the children and spousal support. In response, Mr. Friedenberg also filed a complaint seeking custody. Mr. Friedenberg subpoenaed mental health treatment records for Mrs. Friedenberg, who responded by filing a request to prevent the release of these records given physician-patient privilege. Mr. Friedenberg argued that Mrs. Friedenberg had placed her physical and mental health at issue when she filed for divorce and custody. At no point did Mr. Friedenberg allege that Mrs. Friedenberg’s mental health made her an unfit parent. The court agreed with Mr. Friedenberg and compelled disclosure of Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records, stating it is “hard to imagine a scenario where the mental health records of a parent would not be relevant to issues around custody and the best interests of the children.” The judge reviewed Mrs. Friedenberg’s psychiatric records privately and released records deemed relevant to the custody proceedings. On appeal, the Ohio Supreme Court agreed with this approach, holding that a parent’s mental fitness is always an issue in child custody cases, even if not asserted by either party. The court further held that unnecessary disclosure of sensitive information was prevented by the judge’s private review of records before deciding which records to release to the opposing spouse.

Waiver of physician-patient privilege

Waiver of physician-patient privilege in custody and divorce proceedings varies by state (Table 33-6). The Friedenberg decision highlights the most restrictive approach, where the mere filing of a divorce and child custody request automatically waives privilege. Some states, such as Indiana,4 follow a similar scheme to Ohio. Other states are silent on this issue or explicitly prohibit a waiver of privilege, asserting that custody disputes alone do not trigger disclosure without additional justifications, such as aberrant parental behaviors or other historical information concerning for abuse, neglect, or lack of parental fitness, or if a parent places their mental health at issue.7

Continue to: Once privilege is waived...

Once privilege is waived, the next step is to determine who should examine psychiatric records, deem relevance, and disclose sensitive information to the court and the opposing party. A judge may make this determination, as in the Friedenberg case. Alternatively, an independent psychiatric examiner may be appointed by the court to examine one or both parties; to obtain collateral information, including psychiatric records; and to submit a report to the court with medicolegal opinions regarding parental fitness. For example, in Maryland,6 the mere filing of a custody suit does not waive privilege. If a parent’s mental health is questioned, the judge may order an independent psychiatric examination to determine the parent’s fitness, thus balancing the best interests of the child with the parent’s right to physician-patient privilege.

The problem with automatic waivers

The foundation of the physician-patient relationship is trust and confidentiality. While this holds true for every specialty, perhaps it is even more important in psychiatry, where our patients routinely disclose sensitive, personal information in hopes of healing. Patients may not be aware of exceptions to confidentiality, or only be aware of the most well-known exceptions, such as the clinician’s duty to report abuse, or to warn a third party about risk of harm by a patient. Furthermore, clinicians and patients alike may not be aware of less-common exceptions to privilege, such as those that may occur in custody proceedings. This is critically important in light of the high number of patients who are or may be seeking divorce and custody of their children.

As psychiatric clinicians, it is highly likely that we will see patients going through divorce and custody proceedings. In 2018, there were 2.24 marriages for every divorce,8 and in 2014, 27% of all American children were living with a custodial parent, with the other parent living elsewhere.9 Divorce can be a profoundly stressful time; thus, it would be expected that many individuals going through divorce would seek psychiatric treatment and support.

Our concern is that the Friedenberg approach, which results in automatic disclosure of sensitive mental health information when a party files for divorce and custody, could deter patients from seeking psychiatric treatment, especially those anticipating divorce. Importantly, because women are nearly twice as likely as men to experience depression and anxiety10 and are more likely to seek treatment, this approach could disproportionately impact them.11 In general, an automatic waiver policy may create an additional obstacle for individuals who are already reticent to seek treatment.

How to handle these situations

As a psychiatrist, you should be familiar with your state’s laws regarding exceptions to patient-physician privilege, and should discuss exceptions at the outset of treatment. However, you will need to weigh the potential negative impacts of this information on the therapeutic relationship, including possible early termination. Furthermore, this information may impact a patient’s willingness to disclose all relevant information to mental health treatment if there is concern for later court disclosure. How should you balance these concerns? First, encourage patients to ask questions and raise concerns about confidentiality and privilege.12 In addition, you may direct the patient to other resources, such as a family law attorney, if they have questions about how certain information may be used in a legal proceeding.

Continue to: Second, you should be...

Second, you should be transparent regarding documentation of psychiatric visits. While documentation must meet ethical, legal, and billing requirements, you should take care to include only relevant information needed to make a diagnosis and provide indicated treatment while maintaining a neutral tone and avoiding medical jargon.13 For instance, we frequently use the term “denied” in medical documentation, as in “Mr. X denied cough, sore throat, fever or chills.” However, in psychiatric notes, if a patient “denied alcohol use,” the colloquial interpretation of this word could imply a tone of distrust toward the patient. A more sensitive way to document this might be: “When screened, reported no alcohol use.” If a patient divulges information and then asks you to omit this from their chart, but you do not feel comfortable doing so, explain what and why you must include the information in the chart.14

Third, if you receive a subpoena or other document requesting privileged information, first contact the patient and inform them of the request, and then seek legal consultation through your employer or malpractice insurer.15 Not all subpoenas are valid and enforceable, so it is important for an attorney to examine the subpoena; in addition, the patient’s attorney may choose to challenge the subpoena and limit the disclosure of privileged information.

Finally, inform legislatures and courts about the potential harm of automatic waivers in custody proceedings. A judge’s examination of the psychiatric records, as in Friedenberg, is not an adequate safeguard. A judge is not a trained mental health professional and may deem “relevant” information to be nearly everything: a history of abuse, remote drug or alcohol use, disclosure of a past crime, or financial troubles. We advocate for courts to follow the Maryland model, where a spouse does not automatically waive privilege if filing for divorce or custody. If mental health becomes an issue in a case, then the court may seek an independent psychiatric examination. The independent examiner will have access to patient records but will be in a better position to determine which details are relevant in determining diagnosis and parental fitness, and to render an opinion to the court.

CASE CONTINUED

You inform Mrs. W about a possible exception to privilege in divorce and custody cases. She decides to first talk with a family law attorney before proceeding with treatment. You defer your diagnosis and wait to see if she wants to proceed with treatment. Unfortunately, she does not return to your office.

Bottom Line

Some states limit the confidentiality and privilege of parents who are in psychiatric treatment and also involved in divorce and child custody cases. Psychiatrists should be mindful of these exceptions, and discuss them with patients at the onset of treatment.

Related Resources

- Legal Information Institute. Child custody: an overview. www.law.cornell.edu/wex/child_custody

- Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Child custody in divorce. In: Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological evaluations for the courts. Guilford Press; 2018:530-533.

1. Jaffee v Redmond, 518 US 1 (1996).

2. Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 118 Cal Rptr 129 (Cal 1974); modified by Tarasoff v Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 551 P.2d 334 (Cal 1976).

3. Friedenberg v Friedenberg, No. 2019-0416 (Ohio 2020).

4. Owen v Owen, 563 NE 2d 605 (Ind 1991).

5. People ex. Rel. Hickox v Hickox, 410 NY S 2d 81 (NY App Div 1978).

6. Laznovsky v Laznovsky, 745 A 2d 1054 (Md 2000).

7. Eykel I, Miskel E. The mental health privilege in divorce and custody cases. Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers. 2012;25(2):453-476.

8. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats: Family life. Marriage and divorce. Published May 2020. Accessed July 29, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm

9. The United States Census Bureau. Current population reports: custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2013. Published January 2016. Accessed July 29, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/P60-255.pdf

10. World Health Organization. Gender and mental health. Published June 2002. Accessed August 2, 2021. https://www.who.int/gender/other_health/genderMH.pdf

11. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

12. Younggren J, Harris E. Can you keep a secret? Confidentiality in psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):589-600.

13. The Committee on Psychiatry and Law. Confidentiality and privilege communication in the practice of psychiatry. Report no. 45. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry; 1960.

14. Wiger D. Ethical considerations in documentation. In: Wiger D. The psychotherapy documentation primer. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2013:35-45.

15. Stansbury CD. Accessibility to a parent’s psychotherapy records in custody disputes: how can the competing interests be balanced? Behav Sci Law. 2010;28(4):522-541.

Mrs. W, age 35, presents to your clinic seeking treatment for anxiety and depression. She has no psychiatric history but reports feeling sad, overwhelmed, and stressed. Mrs. W has been married for 10 years, has 2 young children, and is currently pregnant. She recently discovered that her husband has been having an affair. Mrs. W tells you that she feels her marriage is unsalvageable and would like to ask her husband for a divorce, but worries that he will “put up a fight” and demand full custody of their children. When you ask why, she states that her husband is “pretty narcissistic” and tends to become combative when criticized or threatened, such as a recent discussion they had about his affair that ended with him concluding that if she were “sexier and more confident” he would not have cheated on her.

As Mrs. W is talking, you recall a conversation you recently overheard at a continuing medical education event. Two clinicians were discussing how their records had been subpoenaed in a child custody case, even though the patient’s mental health was not contested. You realize that Mrs. W’s situation may also fit under this exception to confidentiality or privilege. You wonder if you should have disclosed this possibility to her at the outset of your session and wonder what you should say now, because she is clearly in distress and in need of psychiatric treatment. On the other hand, you want her to be fully informed of the potential repercussions if she continues with treatment.

Confidentiality and privilege allow our patients to disclose sensitive details in a safe space. The psychiatrist’s duty is to keep the patient’s information confidential, except in limited circumstances. The patient’s privilege is their right to prevent someone in a special confidential relationship from testifying against them or releasing their private records. In certain instances, a patient may waive or be forced to waive privilege, and a psychiatrist may be compelled to testify or release treatment records to a court. This article reviews exceptions to confidentiality and privilege, focusing specifically on a little-known exception to privilege that arises in divorce and child custody cases. We discuss relevant legislation and provide recommendations for psychiatrists to better understand how to discuss these legal realities with patients who are or may go through a divorce or child custody case.

Understanding confidentiality and privilege

Confidentiality and privilege are related but distinct concepts. Confidentiality relates to the overall trusting relationship created between 2 parties, such as a physician and their patient, and the duty on the part of the trusted individual to keep information private. Privilege refers to a person’s specific legal right to prevent someone in that confidential, trusting relationship from testifying against them in court or releasing confidential records. Privilege is owned by the patient and must be asserted or waived by the patient in legal proceedings. The concepts of confidentiality and privilege are crucial in creating an open, candid therapeutic environment. Many courts, including the US Supreme Court,1 have recognized the importance of confidentiality and privilege in establishing a positive therapeutic relationship between a psychotherapist and a patient. Without confidentiality and privilege, patients would be less likely to share sensitive yet clinically important information.

Commonly encountered exceptions to confidentiality (Table 12) and privilege (Table 2) exist in medical practice. Psychiatrists should discuss these exceptions with patients at the outset of clinical treatment. A little-known exception to privilege that may compel a psychiatrist to disclose confidential records can occur in child custody proceedings. In certain states, the mere filing of a child custody claim constitutes an exception to physician-patient privilege. In these states, the parent filing for divorce and custody may automatically waive privilege and thus compel disclosure of psychiatric records, even if their mental health is not in question. The following recent Ohio Supreme Court case illustrates this exception.

Friedenberg v Friedenberg (2020)