User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

I have a dream … for psychiatry

One of the most inspiring speeches ever made is Rev. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” about ending discrimination and achieving social justice. Many of the tenets of that classic speech are relevant to psychiatric patients who have been subjected to discrimination and bias instead of the compassion and support that they deserve, as do patients with other medical disorders.

Like Rev. King, we all have dreams, spoken and unspoken. They may be related to our various goals or objectives as individuals, spouses, parents, professionals, friends, or citizens of the world. Here, I will elaborate on my dream as a psychiatric physician, educator, and researcher, with decades of experience treating thousands of patients, many of whom I followed for a long time. I have come to see the world through the eyes and painful journeys of suffering psychiatric patients.

Vision of a better world for our patients

So, here is my dream, comprised of multiple parts that many clinician-readers may have incorporated in their own dreams about psychiatry. I have a dream:

- that the ugly, stubborn stigma of mental illness evaporates and is replaced with empathy and compassion

- that genuine full parity be implemented for all psychiatric patients

- that the public becomes far more educated about their own mental health, and cognizant of psychiatric symptoms in their family members and friends, so they can urge them to promptly seek medical help. The public should be aware that the success rate of treating psychiatric disorders is similar to that of many general medical conditions, such as heart, lung, kidney, and liver diseases

- that psychiatry continues to evolve into a clinical neuroscience, respected and appreciated like its sister neurology, and emphasizing that all mental illnesses are biologically rooted in various brain circuits

- that neuroscience literacy among psychiatrists increases dramatically, while maintaining our biopsychosocial clinical framework

- that federal funding for research into the causes and treatments of psychiatric disorders increases by an order of magnitude, to help accelerate the discovery of cures for disabling psychiatric disorders, which have a serious personal, societal, and financial toll

- that some of the many fabulously wealthy billionaires in this country (and around the world) adopt psychiatry as their favorite charity, and establish powerful and very well-funded research foundations to explore the brain and solve its mysteries in health and disease

- that effective treatments for and interventions to prevent alcohol and substance use disorders are discovered, including vaccines for alcoholism and other drugs of abuse. This would save countless lives lost to addiction

- that Medicare opens its huge wallet and supports thousands of additional residency training positions to address the serious shortage of psychiatrists

- that pharmaceutical companies, admittedly the only entities with the requisite infrastructure to develop new drugs for psychiatry, be creatively incentivized to discover drugs with new mechanisms of action to effectively treat psychiatric conditions for which there are no FDA-approved medications, such as the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia, personality disorders (such as borderline personality), autism, and Alzheimer’s disease

- that the jailing, incarceration, and criminalization of patients with serious mental illness ceases immediately and is replaced with hospitalization and dignified medical treatment instead of prison sentences with murders and rapists. Building more hospitals instead of more prisons is the civilized and ethical approach to psychiatric brain disorders

- that the public recognizes that persons suffering from schizophrenia are more likely to be victims of crime rather than perpetrators. Tell that to the misguided media

- that clinicians in primary care specialties, where up to 50% of patients have a diagnosable and treatable psychiatric illness, be much better trained in psychiatry during their residency. Currently, residents in family medicine, general internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology receive 0 months to 1 month of psychiatry in their 4 years of training. Many are unable to handle the large number of psychiatric disorders in their patients. In addition, psychiatrists and primary care physicians should be colocalized so psychiatric and primary care patients can both benefit from true collaborative care, because many are dually afflicted

- that the syndemic1 (ie, multiple epidemics) that often is effectively addressed for the sake of our patients and society at large. The ongoing syndemic includes poverty, child abuse, human trafficking, domestic violence, racism, suicide, gun violence, broken families, and social media addiction across all ages

- that psychiatric practitioners embrace and adopt validated rating scales in their practice to quantify the severity of the patient’s illness and adverse effects at each visit, and to assess the degree of improvement in both. Measurement is at the foundation of science. Psychiatry will be a stronger medical specialty with measurement-based practice

- that licensing boards stop discriminating against physicians who have recovered from a psychiatric disorder or addiction. This form of stigma is destructive to the functioning of highly trained medical professionals who recover with treatment and can return to work

- that the number of psychiatric hospital beds in the country is significantly expanded to accommodate the high demand, and that psychiatric wards in general hospitals not be repurposed for more lucrative, procedure-oriented programs

- that insurance companies stop the absurdity of authorizing only 3 to 4 days for the inpatient treatment of patients who are acutely psychotic, manic, or suicidally depressed. It is impossible for such serious brain disorders to improve rapidly. This leads to discharging patients who are still unstable and who might relapse quickly after discharge, risking harm to themselves, or ending up in jail

- that HIPAA laws are revised to allow psychiatrists to collect or exchange information about ailing adult members of the family. Collateral information is a vital component of psychiatric evaluation, and its prohibition can be harmful to the patient. The family often is the most likely support system for the mentally ill individual, and must be informed about what their family member needs after discharge

- that long-acting antipsychotics are used very early and widely to prevent the tragic consequences of psychotic relapses,2 and long-lasting antidepressants are developed to prevent the relapse and risk of suicide in many patients who stop their antidepressant medication once they feel better, and do not recognize that like hypertension or diabetes, depression requires ongoing pharmacotherapy to prevent relapse

- that the time to get a court order for involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication to acutely psychotic patients is reduced to 1 day because a large body of published evidence shows that a longer duration of untreated psychosis has a deleterious neurotoxic effect on the brain, worsening outcomes and prognosis.3 The legal system should catch up with scientific findings.

Just as Martin Luther King’s dream resonated loudly for decades and led to salutary legal and societal changes, I hope that what I dream about will eventually become reality. My dream is shared by all my fellow psychiatrists, and it will come true if we unite, lobby continuously, and advocate vigorously for our patients and our noble profession. I am sure we shall overcome our challenges someday.

1. Namer Y, Razum O. Surviving syndemics. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):118-119.

2. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

3. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

One of the most inspiring speeches ever made is Rev. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” about ending discrimination and achieving social justice. Many of the tenets of that classic speech are relevant to psychiatric patients who have been subjected to discrimination and bias instead of the compassion and support that they deserve, as do patients with other medical disorders.

Like Rev. King, we all have dreams, spoken and unspoken. They may be related to our various goals or objectives as individuals, spouses, parents, professionals, friends, or citizens of the world. Here, I will elaborate on my dream as a psychiatric physician, educator, and researcher, with decades of experience treating thousands of patients, many of whom I followed for a long time. I have come to see the world through the eyes and painful journeys of suffering psychiatric patients.

Vision of a better world for our patients

So, here is my dream, comprised of multiple parts that many clinician-readers may have incorporated in their own dreams about psychiatry. I have a dream:

- that the ugly, stubborn stigma of mental illness evaporates and is replaced with empathy and compassion

- that genuine full parity be implemented for all psychiatric patients

- that the public becomes far more educated about their own mental health, and cognizant of psychiatric symptoms in their family members and friends, so they can urge them to promptly seek medical help. The public should be aware that the success rate of treating psychiatric disorders is similar to that of many general medical conditions, such as heart, lung, kidney, and liver diseases

- that psychiatry continues to evolve into a clinical neuroscience, respected and appreciated like its sister neurology, and emphasizing that all mental illnesses are biologically rooted in various brain circuits

- that neuroscience literacy among psychiatrists increases dramatically, while maintaining our biopsychosocial clinical framework

- that federal funding for research into the causes and treatments of psychiatric disorders increases by an order of magnitude, to help accelerate the discovery of cures for disabling psychiatric disorders, which have a serious personal, societal, and financial toll

- that some of the many fabulously wealthy billionaires in this country (and around the world) adopt psychiatry as their favorite charity, and establish powerful and very well-funded research foundations to explore the brain and solve its mysteries in health and disease

- that effective treatments for and interventions to prevent alcohol and substance use disorders are discovered, including vaccines for alcoholism and other drugs of abuse. This would save countless lives lost to addiction

- that Medicare opens its huge wallet and supports thousands of additional residency training positions to address the serious shortage of psychiatrists

- that pharmaceutical companies, admittedly the only entities with the requisite infrastructure to develop new drugs for psychiatry, be creatively incentivized to discover drugs with new mechanisms of action to effectively treat psychiatric conditions for which there are no FDA-approved medications, such as the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia, personality disorders (such as borderline personality), autism, and Alzheimer’s disease

- that the jailing, incarceration, and criminalization of patients with serious mental illness ceases immediately and is replaced with hospitalization and dignified medical treatment instead of prison sentences with murders and rapists. Building more hospitals instead of more prisons is the civilized and ethical approach to psychiatric brain disorders

- that the public recognizes that persons suffering from schizophrenia are more likely to be victims of crime rather than perpetrators. Tell that to the misguided media

- that clinicians in primary care specialties, where up to 50% of patients have a diagnosable and treatable psychiatric illness, be much better trained in psychiatry during their residency. Currently, residents in family medicine, general internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology receive 0 months to 1 month of psychiatry in their 4 years of training. Many are unable to handle the large number of psychiatric disorders in their patients. In addition, psychiatrists and primary care physicians should be colocalized so psychiatric and primary care patients can both benefit from true collaborative care, because many are dually afflicted

- that the syndemic1 (ie, multiple epidemics) that often is effectively addressed for the sake of our patients and society at large. The ongoing syndemic includes poverty, child abuse, human trafficking, domestic violence, racism, suicide, gun violence, broken families, and social media addiction across all ages

- that psychiatric practitioners embrace and adopt validated rating scales in their practice to quantify the severity of the patient’s illness and adverse effects at each visit, and to assess the degree of improvement in both. Measurement is at the foundation of science. Psychiatry will be a stronger medical specialty with measurement-based practice

- that licensing boards stop discriminating against physicians who have recovered from a psychiatric disorder or addiction. This form of stigma is destructive to the functioning of highly trained medical professionals who recover with treatment and can return to work

- that the number of psychiatric hospital beds in the country is significantly expanded to accommodate the high demand, and that psychiatric wards in general hospitals not be repurposed for more lucrative, procedure-oriented programs

- that insurance companies stop the absurdity of authorizing only 3 to 4 days for the inpatient treatment of patients who are acutely psychotic, manic, or suicidally depressed. It is impossible for such serious brain disorders to improve rapidly. This leads to discharging patients who are still unstable and who might relapse quickly after discharge, risking harm to themselves, or ending up in jail

- that HIPAA laws are revised to allow psychiatrists to collect or exchange information about ailing adult members of the family. Collateral information is a vital component of psychiatric evaluation, and its prohibition can be harmful to the patient. The family often is the most likely support system for the mentally ill individual, and must be informed about what their family member needs after discharge

- that long-acting antipsychotics are used very early and widely to prevent the tragic consequences of psychotic relapses,2 and long-lasting antidepressants are developed to prevent the relapse and risk of suicide in many patients who stop their antidepressant medication once they feel better, and do not recognize that like hypertension or diabetes, depression requires ongoing pharmacotherapy to prevent relapse

- that the time to get a court order for involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication to acutely psychotic patients is reduced to 1 day because a large body of published evidence shows that a longer duration of untreated psychosis has a deleterious neurotoxic effect on the brain, worsening outcomes and prognosis.3 The legal system should catch up with scientific findings.

Just as Martin Luther King’s dream resonated loudly for decades and led to salutary legal and societal changes, I hope that what I dream about will eventually become reality. My dream is shared by all my fellow psychiatrists, and it will come true if we unite, lobby continuously, and advocate vigorously for our patients and our noble profession. I am sure we shall overcome our challenges someday.

One of the most inspiring speeches ever made is Rev. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” about ending discrimination and achieving social justice. Many of the tenets of that classic speech are relevant to psychiatric patients who have been subjected to discrimination and bias instead of the compassion and support that they deserve, as do patients with other medical disorders.

Like Rev. King, we all have dreams, spoken and unspoken. They may be related to our various goals or objectives as individuals, spouses, parents, professionals, friends, or citizens of the world. Here, I will elaborate on my dream as a psychiatric physician, educator, and researcher, with decades of experience treating thousands of patients, many of whom I followed for a long time. I have come to see the world through the eyes and painful journeys of suffering psychiatric patients.

Vision of a better world for our patients

So, here is my dream, comprised of multiple parts that many clinician-readers may have incorporated in their own dreams about psychiatry. I have a dream:

- that the ugly, stubborn stigma of mental illness evaporates and is replaced with empathy and compassion

- that genuine full parity be implemented for all psychiatric patients

- that the public becomes far more educated about their own mental health, and cognizant of psychiatric symptoms in their family members and friends, so they can urge them to promptly seek medical help. The public should be aware that the success rate of treating psychiatric disorders is similar to that of many general medical conditions, such as heart, lung, kidney, and liver diseases

- that psychiatry continues to evolve into a clinical neuroscience, respected and appreciated like its sister neurology, and emphasizing that all mental illnesses are biologically rooted in various brain circuits

- that neuroscience literacy among psychiatrists increases dramatically, while maintaining our biopsychosocial clinical framework

- that federal funding for research into the causes and treatments of psychiatric disorders increases by an order of magnitude, to help accelerate the discovery of cures for disabling psychiatric disorders, which have a serious personal, societal, and financial toll

- that some of the many fabulously wealthy billionaires in this country (and around the world) adopt psychiatry as their favorite charity, and establish powerful and very well-funded research foundations to explore the brain and solve its mysteries in health and disease

- that effective treatments for and interventions to prevent alcohol and substance use disorders are discovered, including vaccines for alcoholism and other drugs of abuse. This would save countless lives lost to addiction

- that Medicare opens its huge wallet and supports thousands of additional residency training positions to address the serious shortage of psychiatrists

- that pharmaceutical companies, admittedly the only entities with the requisite infrastructure to develop new drugs for psychiatry, be creatively incentivized to discover drugs with new mechanisms of action to effectively treat psychiatric conditions for which there are no FDA-approved medications, such as the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia, personality disorders (such as borderline personality), autism, and Alzheimer’s disease

- that the jailing, incarceration, and criminalization of patients with serious mental illness ceases immediately and is replaced with hospitalization and dignified medical treatment instead of prison sentences with murders and rapists. Building more hospitals instead of more prisons is the civilized and ethical approach to psychiatric brain disorders

- that the public recognizes that persons suffering from schizophrenia are more likely to be victims of crime rather than perpetrators. Tell that to the misguided media

- that clinicians in primary care specialties, where up to 50% of patients have a diagnosable and treatable psychiatric illness, be much better trained in psychiatry during their residency. Currently, residents in family medicine, general internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology receive 0 months to 1 month of psychiatry in their 4 years of training. Many are unable to handle the large number of psychiatric disorders in their patients. In addition, psychiatrists and primary care physicians should be colocalized so psychiatric and primary care patients can both benefit from true collaborative care, because many are dually afflicted

- that the syndemic1 (ie, multiple epidemics) that often is effectively addressed for the sake of our patients and society at large. The ongoing syndemic includes poverty, child abuse, human trafficking, domestic violence, racism, suicide, gun violence, broken families, and social media addiction across all ages

- that psychiatric practitioners embrace and adopt validated rating scales in their practice to quantify the severity of the patient’s illness and adverse effects at each visit, and to assess the degree of improvement in both. Measurement is at the foundation of science. Psychiatry will be a stronger medical specialty with measurement-based practice

- that licensing boards stop discriminating against physicians who have recovered from a psychiatric disorder or addiction. This form of stigma is destructive to the functioning of highly trained medical professionals who recover with treatment and can return to work

- that the number of psychiatric hospital beds in the country is significantly expanded to accommodate the high demand, and that psychiatric wards in general hospitals not be repurposed for more lucrative, procedure-oriented programs

- that insurance companies stop the absurdity of authorizing only 3 to 4 days for the inpatient treatment of patients who are acutely psychotic, manic, or suicidally depressed. It is impossible for such serious brain disorders to improve rapidly. This leads to discharging patients who are still unstable and who might relapse quickly after discharge, risking harm to themselves, or ending up in jail

- that HIPAA laws are revised to allow psychiatrists to collect or exchange information about ailing adult members of the family. Collateral information is a vital component of psychiatric evaluation, and its prohibition can be harmful to the patient. The family often is the most likely support system for the mentally ill individual, and must be informed about what their family member needs after discharge

- that long-acting antipsychotics are used very early and widely to prevent the tragic consequences of psychotic relapses,2 and long-lasting antidepressants are developed to prevent the relapse and risk of suicide in many patients who stop their antidepressant medication once they feel better, and do not recognize that like hypertension or diabetes, depression requires ongoing pharmacotherapy to prevent relapse

- that the time to get a court order for involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication to acutely psychotic patients is reduced to 1 day because a large body of published evidence shows that a longer duration of untreated psychosis has a deleterious neurotoxic effect on the brain, worsening outcomes and prognosis.3 The legal system should catch up with scientific findings.

Just as Martin Luther King’s dream resonated loudly for decades and led to salutary legal and societal changes, I hope that what I dream about will eventually become reality. My dream is shared by all my fellow psychiatrists, and it will come true if we unite, lobby continuously, and advocate vigorously for our patients and our noble profession. I am sure we shall overcome our challenges someday.

1. Namer Y, Razum O. Surviving syndemics. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):118-119.

2. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

3. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

1. Namer Y, Razum O. Surviving syndemics. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):118-119.

2. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

3. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804.

Maria A. Oquendo, MD, PhD, on the state of psychiatry

For this Psychiatry Leaders’ Perspectives, Awais Aftab, MD, interviewed Maria A. Oquendo, MD, PhD. Dr. Oquendo is the Ruth Meltzer Professor and Chairman of Psychiatry at University of Pennsylvania and Psychiatrist-in-Chief at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Until 2016, she was Professor of Psychiatry and Vice Chairman for Education at Columbia University. In 2017, she was elected to the National Academy of Medicine, one of the highest honors in medicine. Dr. Oquendo has used positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging to map brain abnormalities in mood disorders and suicidal behavior. Dr. Oquendo is Past President of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the International Academy of Suicide Research, and the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP). She is President of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Board of Directors, Vice President of the College of International Neuropsychopharmacology, and has served on the National Institute of Mental Health’s Advisory Council. A recipient of multiple awards in the US, Europe, and South America, most recently, she received the Virginia Kneeland Award for Distinguished Women in Medicine (Columbia University 2016), the Award for Mood Disorders Research (ACP 2017), the Alexandra Symonds Award (APA 2017), the APA’s Research Award (2018), the Dolores Shockley Award (ACNP 2018), the Alexander Glassman Award (Columbia University 2021), and the Senior Investigator Klerman Award (Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance 2021).

Dr. Aftab: A major focus of your presidential year at APA was on prevention in psychiatry (especially suicide prevention), and working toward prevention through collaboration with colleagues in other medical specialties. What is your perspective on where our field presently stands in this regard?

Dr. Oquendo: There are more and more studies that focus on early childhood or pre-adolescence and the utility of intervening at the first sign of a potential issue. This is quite different from what was the case when I was training. Back then, the idea was that in many cases it was best to wait because kids might “grow out of it.” The implication was that care or intervention were “stigmatizing,” or that it could affect the child’s self-esteem and we wanted to “spare” the child. What we are learning now is that there are advantages of intervening early even if the issues are subtle, potentially preventing development of more serious problems down the line. Still, much work remains to be done. Because so many of the disorders we treat are in fact neurodevelopmental, we desperately need more investigators focused on childhood and adolescent mental health. We also need scientists to identify biomarkers that will permit identification of individuals at risk before the emergence of symptoms. Developing that workforce should be front and center if we are to make a dent in the rising rates of psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Aftab: What do you see as some of the strengths of our profession?

Dr. Oquendo: Our profession’s recognition that the doctor-patient relationship remains a powerful element of healing is one of its greatest strengths. Psychiatry is the only area of medicine in which practitioners are students of the doctor-patient relationship. That provides an unparalleled ability to leverage it for good. Another strength is that many who enter psychiatry are humanists, so as a field, we are collectively engaged in working towards improving conditions for our patients and our community.

Dr. Aftab: Are there ways in which the status quo in psychiatry falls short of the ideal? What are our areas of relative weakness?

Dr. Oquendo: The most challenging issue that plagues psychiatry is not of our making, but we do have to address it. The ongoing lack of parity in the US and the insurance industry’s approach of using carve-outs and other strategies to keep psychiatry reimbursement low has led many, if not most, to practice on a cash basis only. This hurts our patients, but also our reputation among our medical colleagues. We need to use creative solutions and engage in advocacy to bring about change.

Dr. Aftab: What is your perception of the threats that psychiatry faces or is likely to face in the future?

Dr. Oquendo: An ongoing threat relates to the low reimbursement for psychiatric services, which tends to drive clinicians towards cash-based practices. Advocacy at the state and federal level as well as with large employers may be one strategy to remedy this inequity.

Dr. Aftab: What do you envision for the future of psychiatry? What sort of opportunities lie ahead for us?

Dr. Oquendo: The adoption of the advances in psychiatry that permit greater reach, such as the adoption of integrated mental health services, utilization of physician extenders, etc., has been slow in psychiatry, but I think the pace is accelerating. This is important because of an upcoming opportunity: the burgeoning need for our help. With stigma quickly decreasing and the younger generations being open about their needs and prioritization of mental health and wellness, it will be a new era, one in which we can make a huge difference in the health and quality of life of the population.

For this Psychiatry Leaders’ Perspectives, Awais Aftab, MD, interviewed Maria A. Oquendo, MD, PhD. Dr. Oquendo is the Ruth Meltzer Professor and Chairman of Psychiatry at University of Pennsylvania and Psychiatrist-in-Chief at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Until 2016, she was Professor of Psychiatry and Vice Chairman for Education at Columbia University. In 2017, she was elected to the National Academy of Medicine, one of the highest honors in medicine. Dr. Oquendo has used positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging to map brain abnormalities in mood disorders and suicidal behavior. Dr. Oquendo is Past President of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the International Academy of Suicide Research, and the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP). She is President of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Board of Directors, Vice President of the College of International Neuropsychopharmacology, and has served on the National Institute of Mental Health’s Advisory Council. A recipient of multiple awards in the US, Europe, and South America, most recently, she received the Virginia Kneeland Award for Distinguished Women in Medicine (Columbia University 2016), the Award for Mood Disorders Research (ACP 2017), the Alexandra Symonds Award (APA 2017), the APA’s Research Award (2018), the Dolores Shockley Award (ACNP 2018), the Alexander Glassman Award (Columbia University 2021), and the Senior Investigator Klerman Award (Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance 2021).

Dr. Aftab: A major focus of your presidential year at APA was on prevention in psychiatry (especially suicide prevention), and working toward prevention through collaboration with colleagues in other medical specialties. What is your perspective on where our field presently stands in this regard?

Dr. Oquendo: There are more and more studies that focus on early childhood or pre-adolescence and the utility of intervening at the first sign of a potential issue. This is quite different from what was the case when I was training. Back then, the idea was that in many cases it was best to wait because kids might “grow out of it.” The implication was that care or intervention were “stigmatizing,” or that it could affect the child’s self-esteem and we wanted to “spare” the child. What we are learning now is that there are advantages of intervening early even if the issues are subtle, potentially preventing development of more serious problems down the line. Still, much work remains to be done. Because so many of the disorders we treat are in fact neurodevelopmental, we desperately need more investigators focused on childhood and adolescent mental health. We also need scientists to identify biomarkers that will permit identification of individuals at risk before the emergence of symptoms. Developing that workforce should be front and center if we are to make a dent in the rising rates of psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Aftab: What do you see as some of the strengths of our profession?

Dr. Oquendo: Our profession’s recognition that the doctor-patient relationship remains a powerful element of healing is one of its greatest strengths. Psychiatry is the only area of medicine in which practitioners are students of the doctor-patient relationship. That provides an unparalleled ability to leverage it for good. Another strength is that many who enter psychiatry are humanists, so as a field, we are collectively engaged in working towards improving conditions for our patients and our community.

Dr. Aftab: Are there ways in which the status quo in psychiatry falls short of the ideal? What are our areas of relative weakness?

Dr. Oquendo: The most challenging issue that plagues psychiatry is not of our making, but we do have to address it. The ongoing lack of parity in the US and the insurance industry’s approach of using carve-outs and other strategies to keep psychiatry reimbursement low has led many, if not most, to practice on a cash basis only. This hurts our patients, but also our reputation among our medical colleagues. We need to use creative solutions and engage in advocacy to bring about change.

Dr. Aftab: What is your perception of the threats that psychiatry faces or is likely to face in the future?

Dr. Oquendo: An ongoing threat relates to the low reimbursement for psychiatric services, which tends to drive clinicians towards cash-based practices. Advocacy at the state and federal level as well as with large employers may be one strategy to remedy this inequity.

Dr. Aftab: What do you envision for the future of psychiatry? What sort of opportunities lie ahead for us?

Dr. Oquendo: The adoption of the advances in psychiatry that permit greater reach, such as the adoption of integrated mental health services, utilization of physician extenders, etc., has been slow in psychiatry, but I think the pace is accelerating. This is important because of an upcoming opportunity: the burgeoning need for our help. With stigma quickly decreasing and the younger generations being open about their needs and prioritization of mental health and wellness, it will be a new era, one in which we can make a huge difference in the health and quality of life of the population.

For this Psychiatry Leaders’ Perspectives, Awais Aftab, MD, interviewed Maria A. Oquendo, MD, PhD. Dr. Oquendo is the Ruth Meltzer Professor and Chairman of Psychiatry at University of Pennsylvania and Psychiatrist-in-Chief at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Until 2016, she was Professor of Psychiatry and Vice Chairman for Education at Columbia University. In 2017, she was elected to the National Academy of Medicine, one of the highest honors in medicine. Dr. Oquendo has used positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging to map brain abnormalities in mood disorders and suicidal behavior. Dr. Oquendo is Past President of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the International Academy of Suicide Research, and the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP). She is President of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Board of Directors, Vice President of the College of International Neuropsychopharmacology, and has served on the National Institute of Mental Health’s Advisory Council. A recipient of multiple awards in the US, Europe, and South America, most recently, she received the Virginia Kneeland Award for Distinguished Women in Medicine (Columbia University 2016), the Award for Mood Disorders Research (ACP 2017), the Alexandra Symonds Award (APA 2017), the APA’s Research Award (2018), the Dolores Shockley Award (ACNP 2018), the Alexander Glassman Award (Columbia University 2021), and the Senior Investigator Klerman Award (Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance 2021).

Dr. Aftab: A major focus of your presidential year at APA was on prevention in psychiatry (especially suicide prevention), and working toward prevention through collaboration with colleagues in other medical specialties. What is your perspective on where our field presently stands in this regard?

Dr. Oquendo: There are more and more studies that focus on early childhood or pre-adolescence and the utility of intervening at the first sign of a potential issue. This is quite different from what was the case when I was training. Back then, the idea was that in many cases it was best to wait because kids might “grow out of it.” The implication was that care or intervention were “stigmatizing,” or that it could affect the child’s self-esteem and we wanted to “spare” the child. What we are learning now is that there are advantages of intervening early even if the issues are subtle, potentially preventing development of more serious problems down the line. Still, much work remains to be done. Because so many of the disorders we treat are in fact neurodevelopmental, we desperately need more investigators focused on childhood and adolescent mental health. We also need scientists to identify biomarkers that will permit identification of individuals at risk before the emergence of symptoms. Developing that workforce should be front and center if we are to make a dent in the rising rates of psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Aftab: What do you see as some of the strengths of our profession?

Dr. Oquendo: Our profession’s recognition that the doctor-patient relationship remains a powerful element of healing is one of its greatest strengths. Psychiatry is the only area of medicine in which practitioners are students of the doctor-patient relationship. That provides an unparalleled ability to leverage it for good. Another strength is that many who enter psychiatry are humanists, so as a field, we are collectively engaged in working towards improving conditions for our patients and our community.

Dr. Aftab: Are there ways in which the status quo in psychiatry falls short of the ideal? What are our areas of relative weakness?

Dr. Oquendo: The most challenging issue that plagues psychiatry is not of our making, but we do have to address it. The ongoing lack of parity in the US and the insurance industry’s approach of using carve-outs and other strategies to keep psychiatry reimbursement low has led many, if not most, to practice on a cash basis only. This hurts our patients, but also our reputation among our medical colleagues. We need to use creative solutions and engage in advocacy to bring about change.

Dr. Aftab: What is your perception of the threats that psychiatry faces or is likely to face in the future?

Dr. Oquendo: An ongoing threat relates to the low reimbursement for psychiatric services, which tends to drive clinicians towards cash-based practices. Advocacy at the state and federal level as well as with large employers may be one strategy to remedy this inequity.

Dr. Aftab: What do you envision for the future of psychiatry? What sort of opportunities lie ahead for us?

Dr. Oquendo: The adoption of the advances in psychiatry that permit greater reach, such as the adoption of integrated mental health services, utilization of physician extenders, etc., has been slow in psychiatry, but I think the pace is accelerating. This is important because of an upcoming opportunity: the burgeoning need for our help. With stigma quickly decreasing and the younger generations being open about their needs and prioritization of mental health and wellness, it will be a new era, one in which we can make a huge difference in the health and quality of life of the population.

Early interventions for psychosis

Neuroscience research over the past half century has failed to significantly advance the treatment of severe mental illness.1,2 Hence, evidence that a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) aggravates—and early intervention with medication and social supports ameliorates—the long-term adverse consequences of psychotic disorders generated a great deal of interest.3,4 This knowledge led to the development of diverse early intervention services worldwide aimed at this putative “critical window.” It raised the possibility that appropriate interventions could prevent the long-term disability that makes chronic psychosis one of the most debilitating disorders.5,6 However, even beyond the varied cultural and economic confounds, it is difficult to assess, compare, and optimize program effectiveness.7 Obstacles include paucity of sufficiently powered, well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the absence of diagnostic biomarkers or other prognostic indicators to better account for the inherent heterogeneity in the population and associated outcomes, and the absence of modifiable risk factors that can guide interventions and provide intermediate outcomes.4,8-10

To better appreciate these issues, it is important to distinguish whether a program is designed to prevent psychosis, or to mitigate the effects of psychosis. Two models include the:

- Prevention model, which focuses on young individuals who are not yet overtly psychotic but at high risk

- First-episode recovery model, which focuses on those who have experienced a first episode of psychosis (FEP) but have not yet developed a chronic disorder.

Both models share long-term goals and are hampered by many of the same issues summarized above. They both deviate markedly from the standard medical model by including psychosocial services designed to promote restoration of a self-defined trajectory to greater independence.11-14 The 2 differ, however, in the challenges they must overcome to produce their sample populations and establish effective interventions.10,15,16

In this article, we provide a succinct overview of these issues and a set of recommendations based on a “strength-based” approach. This approach focuses on finding common ground between patients, their support system, and the treatment team in the service of empowering patients to resume responsibility for transition to adulthood.

The prevention model

While most prevention initiatives in medicine rely on the growing ability to target specific pathophysiologic pathways,3 preventing psychosis relies on clinical evidence showing that DUP and early interventions predict a better course of severe mental illness.17 In contrast, initiatives such as normalizing neonatal neuronal pathways are more consistent with the strategy utilized in other fields but have yet to yield a pathophysiologic target for psychosis.3,18

Initial efforts to identify ‘at-risk’ individuals

The prevention model of psychosis is based on the ability to identify young individuals at high risk for developing a psychotic disorder (Figure). The first screening measures were focused on prodromal psychosis (eg, significant loss of function, family history, and “intermittent” and “attenuated” psychotic symptoms). When applied to referred (ie, pre-screened) samples, 30% to 40% of this group who met criteria transitioned to psychosis over the next 1 to 3 years despite antidepressant and psychosocial interventions.19 Comprising 8 academic medical centers, the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS) produced similar results using the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS).17 Thus, 30% to 50% of pre-screened individuals referred by school counselors and mental health professionals met SIPS criteria, and 35% of these individuals transitioned to psychosis over 30 months. The validity of this measure was further supported by the fact that higher baseline levels of unusual thought content, suspicion/paranoia, social impairment, and substance abuse successfully distinguished approximately 80% of those who transitioned to psychosis. The results of this first generation of screening studies were exciting because they seemed to demonstrate that highly concentrated samples of young persons at high risk of developing psychosis could be identified, and that fine-tuning the screening criteria could produce even more enriched samples (ie, positive predictive power).

Initial interventions produced promising results

The development of effective screening measures led to reports of effective treatment interventions. These were largely applied in a clinical staging model that restricted antipsychotic medications to those who failed to improve after receiving potentially “less toxic” interventions (eg, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and other antioxidants; psychotherapy; cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]; family therapy).5 While study designs were typically quasi-experimental, the interventions appeared to dramatically diminish the transition to psychosis (ie, approximately 50%).

Continue to: The first generation...

The first generation of RCTs appeared to confirm these results, although sample sizes were small, and most study designs assessed only a single intervention. Initial meta-analyses of these data reported that both CBT and antipsychotics appeared to prevent approximately one-half of individuals from becoming psychotic at 12 months, and more than one-third at 2 to 4 years, compared with treatment as usual.20

While some researchers challenged the validity of these findings,21-23 the results generated tremendous international enthusiasm and calls for widespread implementation.6 The number of early intervention services (EIS) centers increased dramatically worldwide, and in 2014 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence released standards for interventions to prevent transition to psychosis.24 These included close monitoring, CBT and family interventions, and avoiding antipsychotics when possible.24

Focusing on sensitivity over specificity

The first generation of studies generated by the prevention model relied on outreach programs or referrals, which produced small samples of carefully selected, pre-screened individuals (Figure, Pre-screened) who were then screened again to establish the high-risk sample.25 While approximately 33% of these individuals became psychotic, the screening process required a very efficient means of eliminating those not at high-risk (given the ultimate target population represented only approximately .5% of young people) (Figure). The pre-screening and screening processes in these first-generation studies were labor-intensive but could only identify approximately 5% of those individuals destined to become psychotic over the next 2 or 3 years. Thus, alternative methods to enhance sensitivity were needed to extend programming to the general population.

Second-generation pre-screening (Figure; Step 1). New pre-screening methods were identified that captured more individuals destined to become psychotic. For example, approximately 90% of this population were registered in health care organizations (eg, health maintenance organizations) and received a psychiatric diagnosis in the year prior to the onset of psychosis (true positives).8 These samples, however, contained a much higher percentage of persons not destined to become psychotic, and somehow the issue of specificity (decreasing false positives) was minimized.8,9 For example, pre-screened samples contained 20 to 50 individuals not destined to become psychotic for each one who did.26 Since screening measures could only eliminate approximately 20% of this group (Figure, Step 2, page 25), second-generation transition rates fell from 30% to 40% to 2% to 10%.27,28

Other pre-screening approaches were introduced, but they also focused on capturing more of those destined to become psychotic (sensitivity) than eliminating those who would not (specificity). For instance, Australia opened more than 100 “Headspace” community centers nationwide designed to promote engagement and self-esteem in youth experiencing anxiety; depression; stress; relationship, work, or school problems; or bullying.13 Most services were free and included mental health staff who screened for psychosis and provided a wide range of services in a destigmatized setting. These methods identified at least an additional 5% to 7% of individuals destined to become psychotic, but to our knowledge, no data have been published on whether they helped eliminate those who did not.

Continue to: Second-generation screening

Second-generation screening (Figure, Step 2). A second screening aims to retain those pre-screened individuals who will become psychotic (ie, minimizing false negatives) while further minimizing those who do not (ie, minimizing false positives). The addition of cognitive, neural (eg, structural MRI; neurophysiologic), and biochemical (eg, inflammatory immune and stress) markers to the risk calculators have produced a sensitivity close to 100%.8,9 Unfortunately, these studies downplayed specificity, which remained approximately 20%.8,9 Specificity is critical not just because of concerns about stigma (ie, labeling people as pre-psychotic when they are not) but also because of the adverse effects of antipsychotic medications and the effects on future program development (interventions are costly and labor-intensive). Also, diluting the pool with individuals not at risk makes it nearly impossible to identify effective interventions (ie, power).27,28

While some studies focused on increasing specificity (to approximately 75%), this leads to an unacceptable loss of sensitivity (from 90% to 60%),29 with 40% of pre-screened individuals who would become psychotic being eliminated from the study population. The addition of other biological markers (eg, salivary cortisol)30 and use of learning health systems may be able to enhance these numbers (initial reports of specificity = 87% and sensitivity = 85%).8,9 This is accomplished by integrating artificial and human intelligence measures of clinical (symptom and neurocognitive measures) and biological (eg, polygenetic risk scores; gray matter volume) variables.31 However, even if these results are replicated, more effective pre-screening measures will be required.

Identifying a suitable sample population for prevention program studies is clearly more complicated than for FEP studies, where one can usually identify many of those in the at-risk population by their first hospitalization for psychotic symptoms. The issues of false positives (eg, substance-induced psychosis) and negatives (eg, slow deterioration, prominent negative symptoms) are important concerns, but proportionately far less significant.

Prevention and FEP interventions

Once a study sample is constituted, 1 to 3 years of treatment interventions are initiated. Interventions for prevention programs typically include CBT directed at attenuated psychosis (eg, reframing or de-catastrophizing unusual thoughts and minimizing distress associated with unusual perceptions); case management to facilitate personal, educational, and vocational goals; and family therapy in single or multi-group formats to educate one’s support system about the risk state and to minimize adverse familial responses.14 Many programs also include supported education or employment services to promote reintegration in age-appropriate activities; group therapy focused on substance abuse and social skills training; cognitive remediation to ameliorate the cognitive dysfunction; and an array of pharmacologic interventions designed to delay or prevent transition to psychosis or to alleviate symptoms. While most interventions are similar, FEP programs have recently included peer support staff. This appears to instill hope in newly diagnosed patients, provide role models, and provide peer supporters an opportunity to use their experiences to help others and earn income.32

The breadth and depth of these services are critical because retention in the program is highly dependent on participant engagement, which in turn is highly dependent on whether the program can help individuals get what they want (eg, friends, employment, education, more autonomy, physical health). The setting and atmosphere of the treatment program and the willingness/ability of staff to meet participants in the community are also important elements.11,12 In this context, the Headspace community centers are having an impact far beyond Australia and may prove to be a particularly good model.13

Continue to: Assessing prevention and FEP interventions

Assessing prevention and FEP interventions

The second generation of studies of prevention programs has not confirmed, let alone extended, the earlier findings and meta-analyses. A 2020 report concluded CBT was still the most promising intervention; it was more effective than control treatments at 12 and 18 months, although not at 6, 24, or 48 months.33 This review included controlled, open-label, and naturalistic studies that assessed family therapy; omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids; integrated psychological therapy (a package of interventions that included family education, CBT, social skills training, and cognitive remediation); N-methyl-

While these disappointing findings are at least partly attributable to the methodological challenges described above and in the Figure, other factors may hinder establishing effective interventions. In contrast to FEP studies, those focused on prevention had a very ambitious agenda (eliminating psychosis) and tended to downplay more modest intermediate outcomes. These studies also tended to assess new ideas with small samples rather than pursue promising findings with larger multi-site studies focused on a group of interventions. The authors of a Cochrane review observed “There is the impression that in this whole area there is a triumph of hope over adversity. There is the repeated hope invested in another—often unique—study question and then a study of fewer than 100 participants are completed. This results in the set of comparisons reported here, all 9 of which are too underpowered to really highlight clear differences.”34 To use a baseball analogy, it seems that investigators are “swinging for the fence” when a few singles are what’s really needed.

From the outset, the goals of FEP studies were more modest, largely ignoring the task of developing consensus definitions of recovery that require following patients for up to 5 to 10 years. Instead, they use intermediate endpoints based on adapting treatments that already appeared effective in patients with chronic mental disorders.35 As a consequence, researchers examining FEP demonstrated clear, albeit limited, salutary effects using large multi-site trials and previously established outcome measures.3,10,36 For instance, the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode-Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP) study was a 2-year, multi-site RCT (N = 404) funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The investigators reported improved indices of social function (eg, quality of life; education and work participation) and total ratings of psychopathology and depression compared with treatment as usual. Furthermore, they established that DUP predicted treatment response.35 The latter finding was underscored by improvement being limited to the 50% with <74 weeks DUP. Annual costs of the program per 1 standard deviation improvement in quality of life were approximately $1,000 for patients with <74 weeks DUP and $40,000 for those with >74 weeks DUP. Concurrent meta-analyses confirmed and extended these findings,16 showing higher remission rates; diminished relapses and hospital admissions; greater engagement in programming; greater involvement in work and school; improved quality of life; and other steps toward recovery. These studies were also able to establish a clear benefit of antipsychotic medications, particularly a high acceptance of long-acting injectable antipsychotic formulations, which promoted adherence and decreased some adverse events37; and early use of clozapine therapy, which improved remission rates and longer-term outcomes.38 Other findings underscored the need to anticipate and address new problems associated with effective antipsychotic therapy (eg, antipsychotic response correlates with weight gain, a particularly intolerable adverse event for this age group).39 Providing pre-emptive strategies such as exercise groups and nutritional education may be necessary to maintain adherence.

Limitations of FEP studies

The effect sizes in these FEP studies were small to medium on outcome measures tracking recovery and associated indicators (eg, global functioning, school/work participation, treatment engagement); the number needed to treat for each of these was >10. There is no clear evidence that recovery programs such as RAISE-ETP actually reduce longer-term disability. Most studies showed disability payments increased while clinical benefits tended to fade over time. In addition, by grouping interventions together, the studies made it difficult to identify effective vs ineffective treatments, let alone determine how best to personalize therapy for participants in future studies.

The next generation of FEP studies

While limited in scope, the results of the recent FEP studies justify a next generation of recovery interventions designed to address these shortcomings and optimize program outcomes.39 Most previous FEP studies were conducted in community mental health center settings, thus eliminating the need to transition services developed in academia into the “real world.” The next generation of NIMH studies will be primarily conducted in analogous settings under the Early Psychosis Intervention Network (EPINET).40 EPINET’s study design echoes that responsible for the stepwise successes in the late 20th century that produced cures for the deadliest childhood cancer, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). This disease was successfully treated by modifying diverse evidence-based practices without relying on pharmacologic or other major treatment breakthroughs. Despite this, the effort yielded successful personalized interventions that were not obtainable for other severe childhood conditions.40 EPINET hopes to automate much of these stepwise advances with a learning health system. This program relies on data routinely collected in clinical practice to drive the process of scientific discovery. Specifically, it determines the relationships between clinical features, biologic measures, treatment characteristics, and symptomatic and functional outcomes. EPINET aims to accelerate our understanding of biomarkers of psychosis risk and onset, as well as factors associated with recovery and cure. Dashboard displays of outcomes will allow for real-time comparisons within and across early intervention clinics. This in turn identifies performance gaps and drives continuous quality improvement.

Continue to: Barriers to optimizing program efficacy for both models

Barriers to optimizing program efficacy for both models

Unfortunately, there are stark differences between ALL and severe mental disorders that potentially jeopardize the achievement of these aims, despite the advances in data analytic abilities that drive the learning health system. Specifically, the heterogeneity of psychotic illnesses and the absence of reliable prognostic and modifiable risk markers (responsible for failed efforts to enhance treatment of serious mental illness over the last half century1,2,41) are unlikely to be resolved by a learning health system. These measures are vital to determine whether specific interventions are effective, particularly given the absence of a randomized control group in the EPINET/learning health system design. Fortunately, however, the National Institutes for Health has recently initiated the Accelerating Medicines Partnership–Schizophrenia (AMP-SCZ). This approach seeks “promising biological markers that can help identify those at risk of developing schizophrenia as early as possible, track the progression of symptoms and other outcomes and ultimately define targets for treatment development.”42 The Box1,4,9,10,36,41,43-45 describes some of the challenges involved in identifying biomarkers of severe mental illness.

Box

Biomarkers and modifiable risk factors4,9,10,41,43 are at the core of personalized medicine and its ultimate objective (ie, theragnostics). This is the ability to identify the correct intervention for a disorder based on a biomarker of the illness.10,36 The inability to identify biomarkers of severe mental illness is multifactorial but in part may be attributable to “looking in all the wrong places.”41 By focusing on neural processes that generate psychiatric symptomatology, investigators are assuming they can bridge the “mind gap”1 and specifically distinguish between pathological, compensatory, or collateral measures of poorly characterized limbic neural functions.41

It may be more productive to identify a pathological process within the limbic system that produces a medical condition as well as the mental disorder. If one can isolate the pathologic limbic circuit activity responsible for a medical condition, one may be able to reproduce this in animal models and determine whether analogous processes contribute to the core features of the mental illness. Characterization of the aberrant neural circuit in animal models also could yield targets for future therapies. For example, episodic water intoxication in a discrete subset of patients with schizophrenia44 appears to arise from a stress diathesis produced by anterior hippocampal pathology that disrupts regulation of antidiuretic hormone, oxytocin, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis secretion. These patients also exhibit psychogenic polydipsia that may be a consequence of the same hippocampal pathology that disrupts ventral striatal and lateral hypothalamic circuits. These circuits, in turn, also modulate motivated behaviors and cognitive processes likely relevant to psychosis.45

A strength-based approach

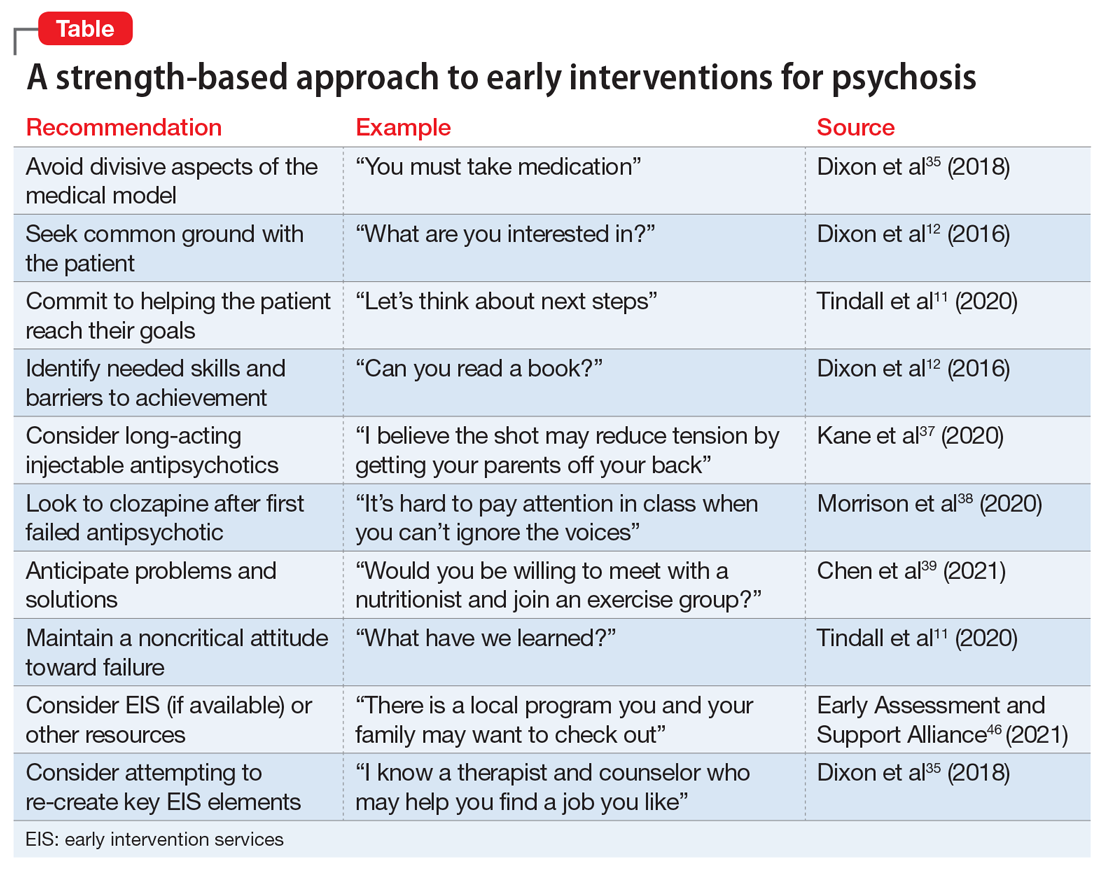

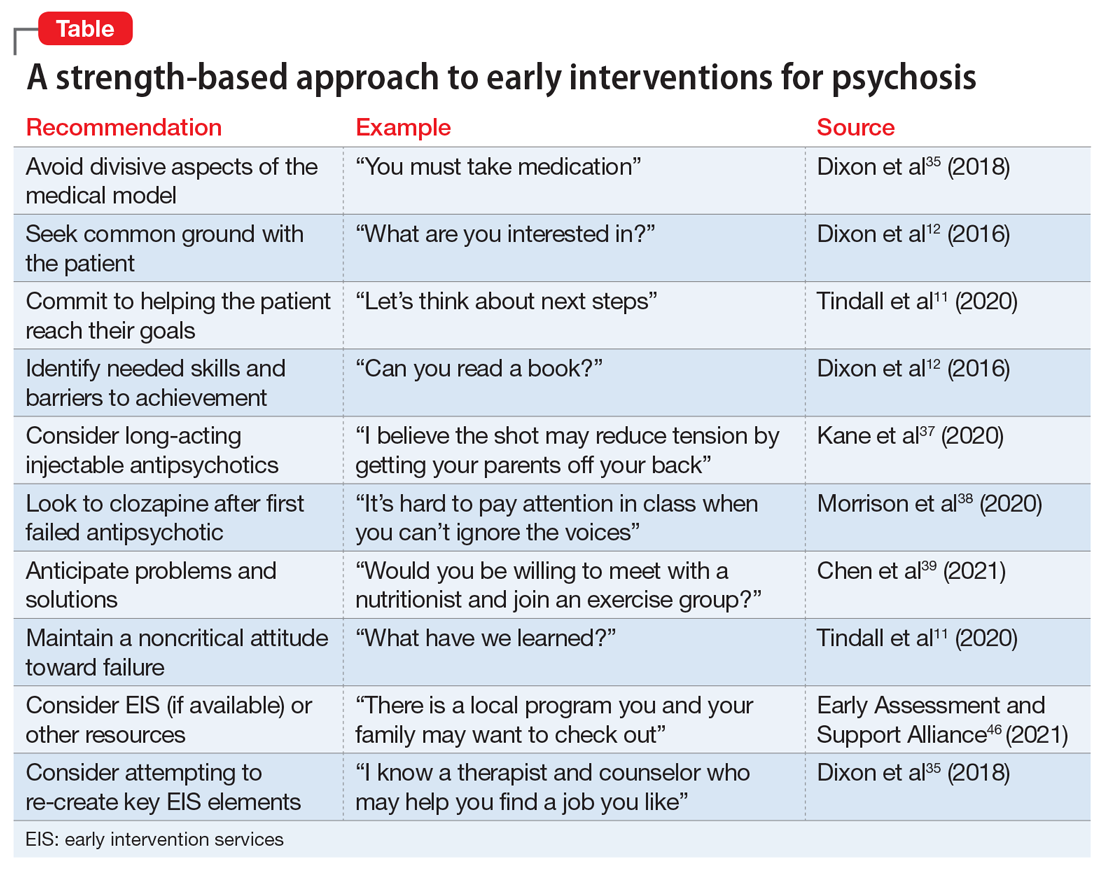

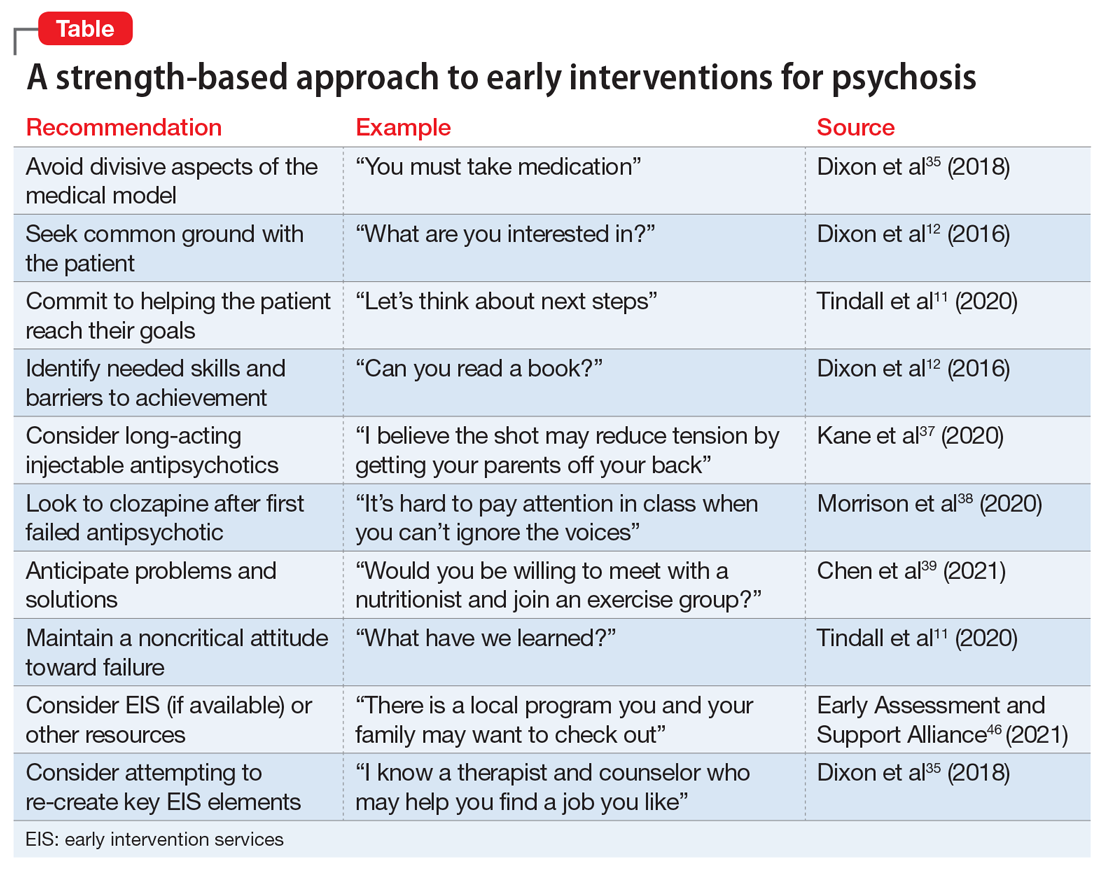

The absence of sufficiently powered RCTs for prevention studies and the reliance on intermediate outcomes for FEP studies leaves unanswered whether such programs can effectively prevent chronic psychosis at a cost society is willing to pay. Still, substantial evidence indicates that outreach, long-acting injectable antipsychotics, early consideration of clozapine, family therapy, CBT for psychosis/attenuated psychosis, and services focused on competitive employment can preserve social and occupational functioning.16,34 Until these broader questions are more definitively addressed, it seems reasonable to apply what we have learned (Table11,12,35,37-39,46).

Simply avoiding the most divisive aspects of the medical model that inadvertently promote stigma and undercut self-confidence may help maintain patients’ willingness to learn how best to apply their strengths and manage their limitations.11 The progression to enduring psychotic features (eg, fixed delusions) may reflect ongoing social isolation and alienation. A strength-based approach seeks first to establish common goals (eg, school, work, friends, family support, housing, leaving home) and then works to empower the patient to successfully reach those goals.35 This typically involves giving them the opportunity to fail, avoiding criticism when they do, and focusing on these experiences as learning opportunities from which success can ultimately result.

It is difficult to offer all these services in a typical private practice setting. Instead, it may make more sense to use one of the hundreds of early intervention services programs in the United States.46 If a psychiatric clinician is dedicated to working with this population, it may also be possible to establish ongoing relationships with primary care physicians, family and CBT therapists, family support services (eg, National Alliance on Mental Illness), caseworkers and employment counselors. In essence, a psychiatrist may be able re-create a multidisciplinary effort by taking advantage of the expertise of these various professionals. The challenge is to create a consistent message for patients and families in the absence of regular meetings with the clinical team, although the recent reliance on and improved sophistication of virtual meetings may help. Psychiatrists often play a critical role even when the patient is not prescribed medication, partly because they are most comfortable handling the risks and may have the most comprehensive understanding of the issues at play. When medications are appropriate and patients with FEP are willing to take them, early consideration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine may provide better stabilization and diminish the risk of earlier and more frequent relapses.

Bottom Line

Early interventions for psychosis include the prevention model and the first-episode recovery model. It is difficult to assess, compare, and optimize the effectiveness of such programs. Current evidence supports a ‘strength-based’ approach focused on finding common ground between patients, their support system, and the treatment team.

Related Resources

- Early Assessment and Support Alliance. National Early Psychosis Directory. https://easacommunity.org/nationaldirectory.php

- Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 ;173(4):362-372

Drug Brand Name

Clozapine • Clozaril

1. Hyman SE. Revolution stalled. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(155):155cm11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003142

2. Harrington A. Mind fixers: psychiatry’s troubled search for the biology of mental illness. W.W. Norton & Company; 2019.

3. Millan MJ, Andrieux A, Bartzokis G, et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: progress and perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(7):485-515.

4. Lieberman JA, Small SA, Girgis RR. Early detection and preventive intervention in schizophrenia: from fantasy to reality. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):794-810.

5. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Nordentoft M, et al. Intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1206-1212.

6. Csillag C, Nordentoft M, Mizuno M, et al. Early intervention in psychosis: From clinical intervention to health system implementation. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(4):757-764.

7. McGorry PD, Ratheesh A, O’Donoghue B. Early intervention—an implementation challenge for 21st century mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):545-546.

8. Rosenheck R. Toward dissemination of secondary prevention for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(5):393-394.

9. Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, Correll CU, et al. Prevention of psychosis: advances in detection, prognosis, and intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(7):755-765.

10. Oliver D, Reilly TJ, Baccaredda Boy O, et al. What causes the onset of psychosis in individuals at clinical high risk? A meta-analysis of risk and protective factors. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(1):110-120.

11. Tindall R, Simmons M, Allott K, et al. Disengagement processes within an early intervention service for first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal, qualitative, multi-perspective study. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:565-565.

12. Dixon LB, Holoshitz Y, Nossel I. Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: review and update. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(1):13-20.

13. Rickwood D, Paraskakis M, Quin D, et al. Australia’s innovation in youth mental health care: The headspace centre model. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(1):159-166.

14. Woodberry KA, Shapiro DI, Bryant C, et al. Progress and future directions in research on the psychosis prodrome: a review for clinicians. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2016;24(2):87-103.

15. Gupta T, Mittal VA. Advances in clinical staging, early intervention, and the prevention of psychosis. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-2027. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20346.1

16. Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555-565.

17. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28-37.

18. Sommer IE, Bearden CE, van Dellen E, et al. Early interventions in risk groups for schizophrenia: what are we waiting for? NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2(1):16003-16003.

19. McGorry PD, Nelson B. Clinical high risk for psychosis—not seeing the trees for the wood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(7):559-560.

20. van der Gaag M, Smit F, Bechdolf A, et al. Preventing a first episode of psychosis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled prevention trials of 12 month and longer-term follow-ups. Schizophr Res. 2013;149(1):56-62.

21. Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD004718. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub3

22. Heinssen RK, Insel TR. Preventing the onset of psychosis: not quite there yet. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(1):28-29.

23. Amos AJ. Evidence that treatment prevents transition to psychosis in ultra-high-risk patients remains questionable. Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1):240.

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG178]. 1.3.7 How to deliver psychological interventions. Published February 12, 2014. Updated March 1, 2014. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/chapter/recommendations#how-to-deliver-psychological-interventions

25. Fusar-Poli P, Werbeloff N, Rutigliano G, et al. Transdiagnostic risk calculator for the automatic detection of individuals at risk and the prediction of psychosis: second replication in an independent National Health Service Trust. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(3):562-570.

26. Fusar-Poli P, Oliver D, Spada G, et al. The case for improved transdiagnostic detection of first-episode psychosis: electronic health record cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2021;228:547-554.

27. Fusar-Poli P. Negative psychosis prevention trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):651.

28. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Furukawa TA. Most at‐risk individuals will not develop a mental disorder: the limited predictive strength of risk factors. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):224-225.

29. Carrión RE, Cornblatt BA, Burton CZ, et al. Personalized prediction of psychosis: external validation of the NAPLS-2 psychosis risk calculator with the EDIPPP Project. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(10):989-996.

30. Worthington MA, Walker EF, Addington J, et al. Incorporating cortisol into the NAPLS2 individualized risk calculator for prediction of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2021;227:95-100.

31. Koutsouleris N, Dwyer DB, Degenhardt F, et al. Multimodal machine learning workflows for prediction of psychosis in patients with clinical high-risk syndromes and recent-onset depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(2):195-209.

32. Simmons MB, Grace D, Fava NJ, et al. The experiences of youth mental health peer workers over time: a qualitative study with longitudinal analysis. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(5):906-914.

33. Devoe DJ, Farris MS, Townes P, et al. Interventions and transition in youth at risk of psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):17r12053. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17r12053

34. Bosnjak Kuharic D, Kekin I, Hew J, et al. Interventions for prodromal stage of psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(11):CD012236

35. Dixon LB, Goldman HH, Srihari VH, et al. Transforming the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States: The RAISE Initiative. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:237-258.

36. Friedman-Yakoobian MS, Parrish EM, Eack SM, et al. Neurocognitive and social cognitive training for youth at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Schizophr Res. 2020;S0920-9964(20)30461-8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.005

37. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. Effect of long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs usual care on time to first hospitalization in early-phase schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1217-1224.

38. Morrison AP, Pyle M, Maughan D, et al. Antipsychotic medication versus psychological intervention versus a combination of both in adolescents with first-episode psychosis (MAPS): a multicentre, three-arm, randomised controlled pilot and feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):788-800.

39. Chen YQ, Li XR, Zhang L, et al. Therapeutic response is associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain in drug-naive first-episode patients with schizophrenia: an 8-week prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(3):20m13469. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13469

40. Insel TR. RAISE-ing our expectations for first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):311-312.

41. Tandon R, Goldman M. Overview of neurobiology. In: Janicak PG, Marder SR, Tandon R, et al, eds. Schizophrenia: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Springer; 2014:27-33.

42. National Institutes of Health. Accelerating Medicines Partnership. Schizophrenia. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.nih.gov/research-training/accelerating-medicines-partnership-amp/schizophrenia

43. Guloksuz S, van Os J. The slow death of the concept of schizophrenia and the painful birth of the psychosis spectrum. Psychol Med. 2018;48(2):229-244.

44. Christ-Crain M, Bichet DG, Fenske WK, et al. Diabetes insipidus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):54.

45. Ahmadi L, Goldman MB. Primary polydipsia: update. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34(5):101469. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2020.101469

46. Early Assessment and Support Alliance. National Early Psychosis Directory. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://easacommunity.org/national-directory.php

Neuroscience research over the past half century has failed to significantly advance the treatment of severe mental illness.1,2 Hence, evidence that a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) aggravates—and early intervention with medication and social supports ameliorates—the long-term adverse consequences of psychotic disorders generated a great deal of interest.3,4 This knowledge led to the development of diverse early intervention services worldwide aimed at this putative “critical window.” It raised the possibility that appropriate interventions could prevent the long-term disability that makes chronic psychosis one of the most debilitating disorders.5,6 However, even beyond the varied cultural and economic confounds, it is difficult to assess, compare, and optimize program effectiveness.7 Obstacles include paucity of sufficiently powered, well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the absence of diagnostic biomarkers or other prognostic indicators to better account for the inherent heterogeneity in the population and associated outcomes, and the absence of modifiable risk factors that can guide interventions and provide intermediate outcomes.4,8-10

To better appreciate these issues, it is important to distinguish whether a program is designed to prevent psychosis, or to mitigate the effects of psychosis. Two models include the:

- Prevention model, which focuses on young individuals who are not yet overtly psychotic but at high risk

- First-episode recovery model, which focuses on those who have experienced a first episode of psychosis (FEP) but have not yet developed a chronic disorder.

Both models share long-term goals and are hampered by many of the same issues summarized above. They both deviate markedly from the standard medical model by including psychosocial services designed to promote restoration of a self-defined trajectory to greater independence.11-14 The 2 differ, however, in the challenges they must overcome to produce their sample populations and establish effective interventions.10,15,16