User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

The third generation of therapeutic innovation and the future of psychopharmacology

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

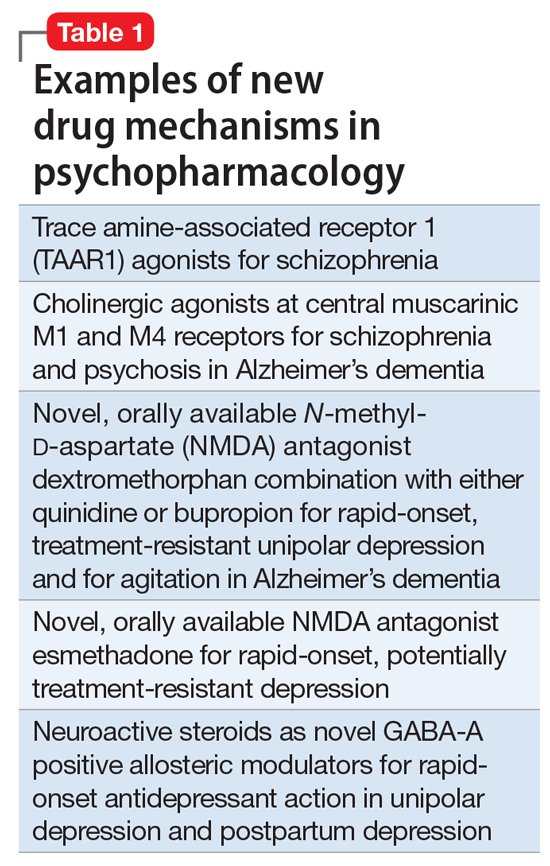

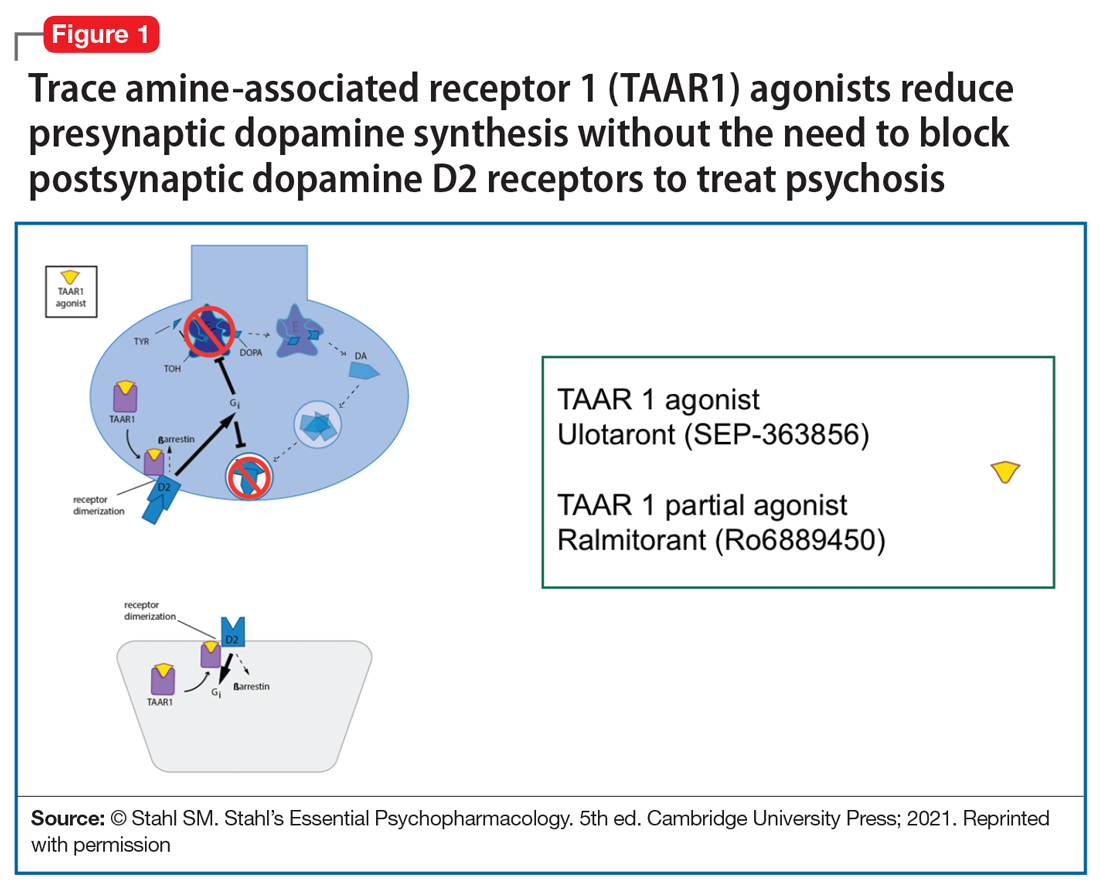

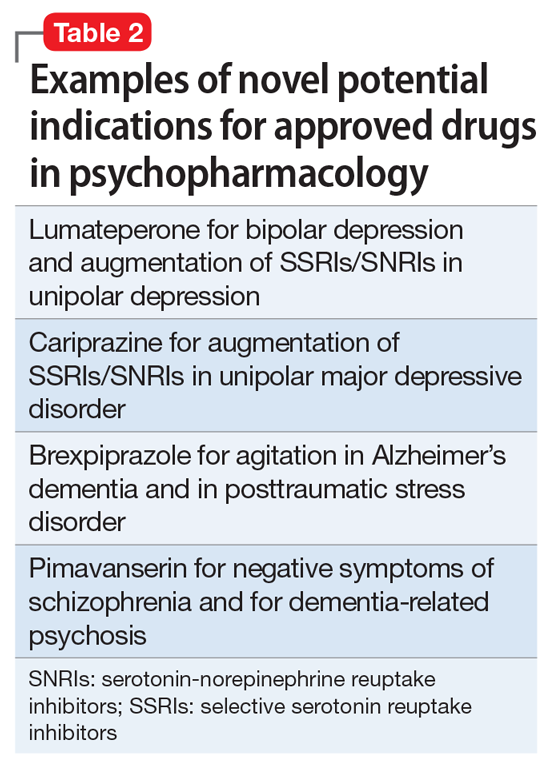

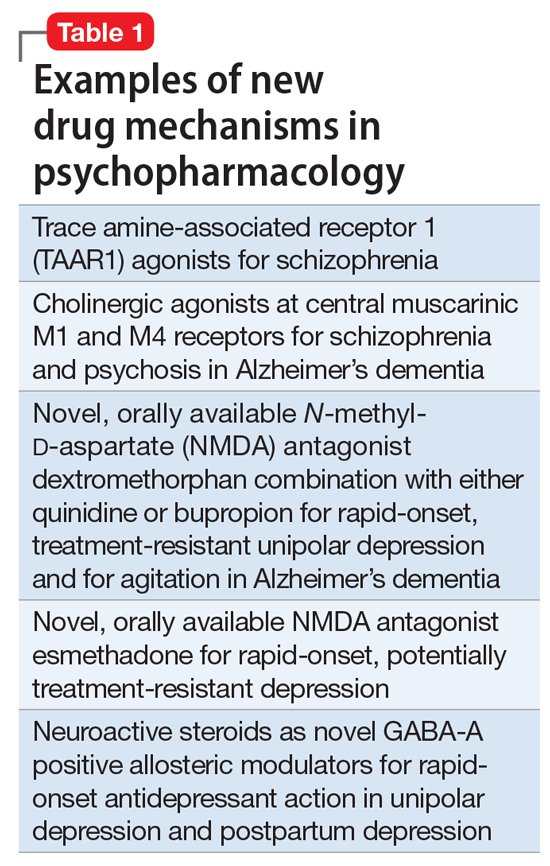

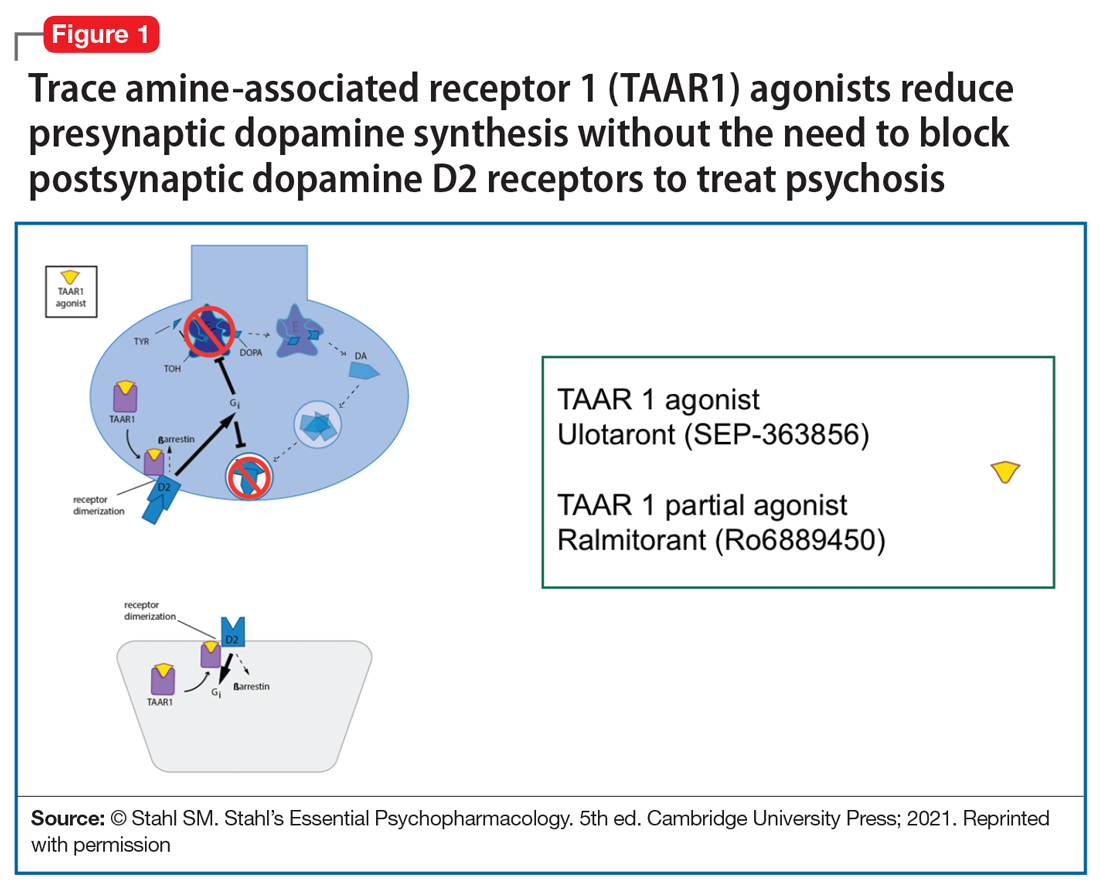

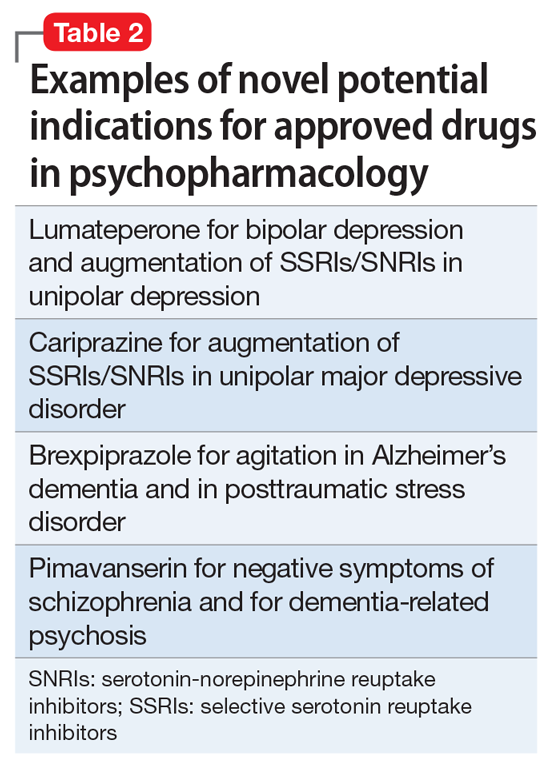

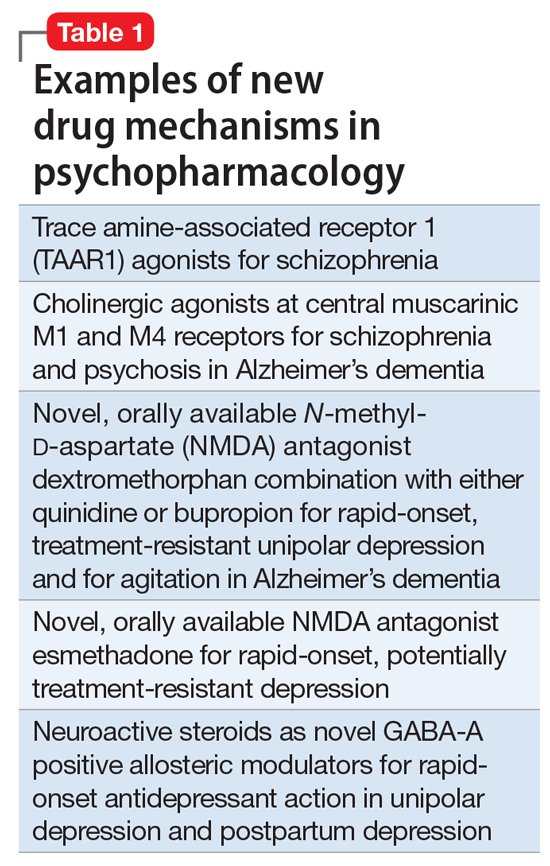

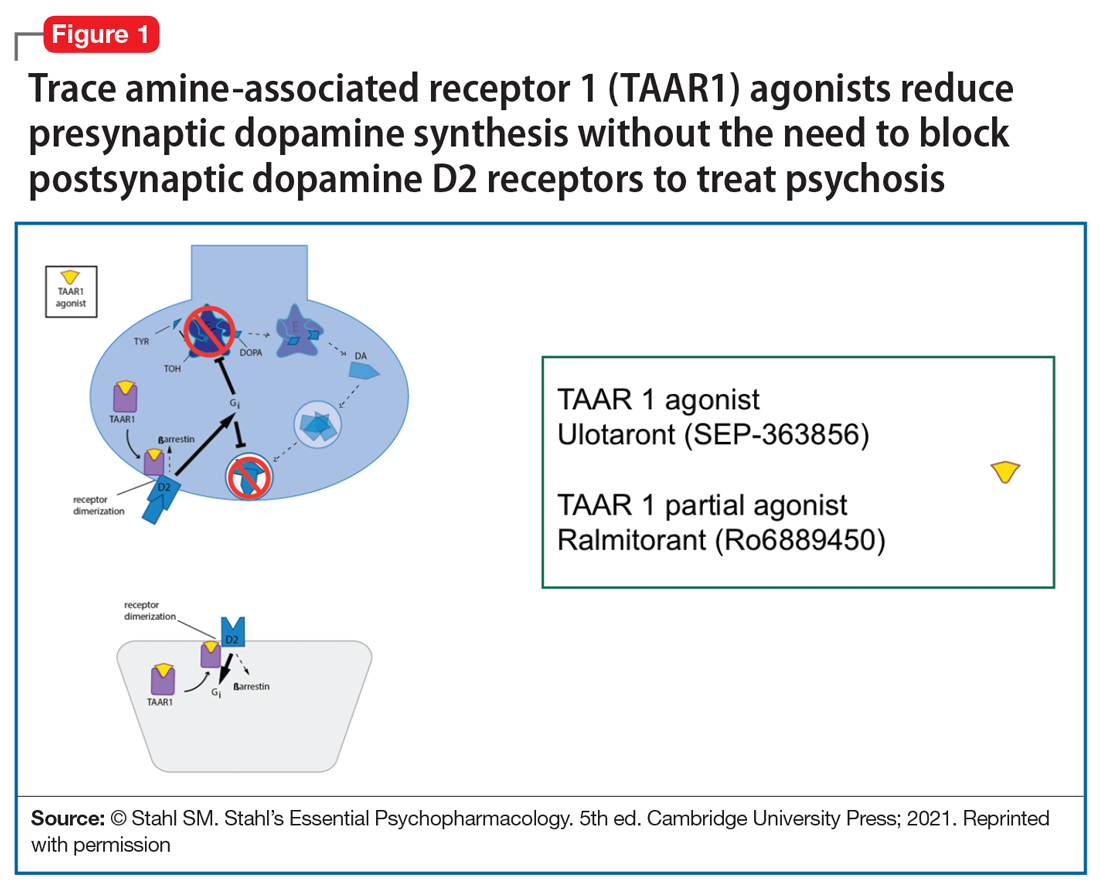

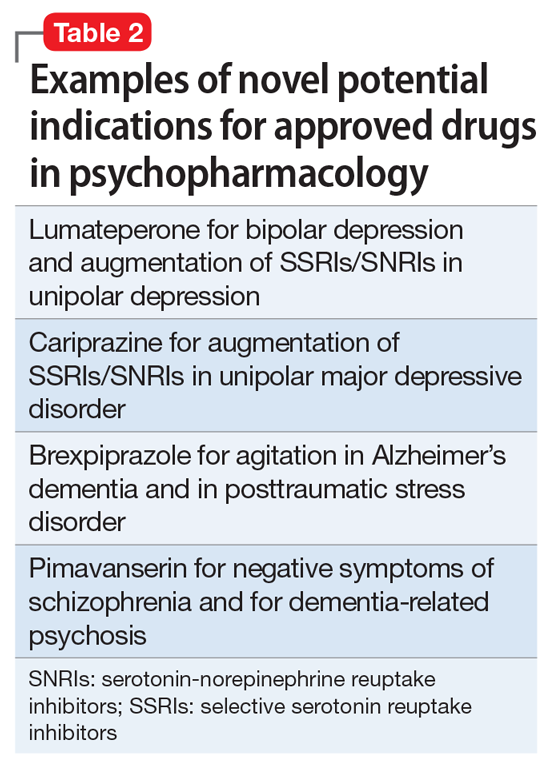

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

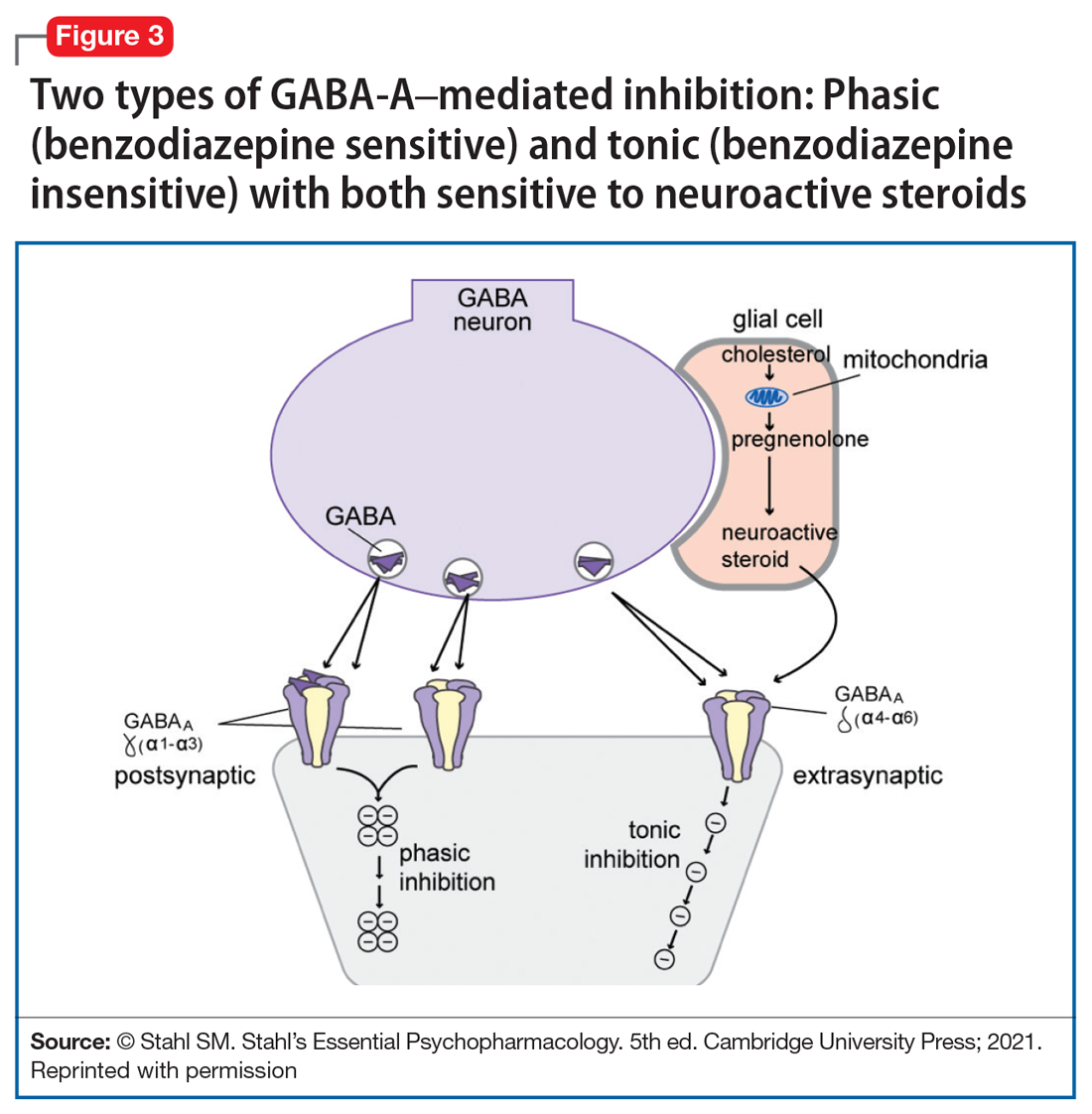

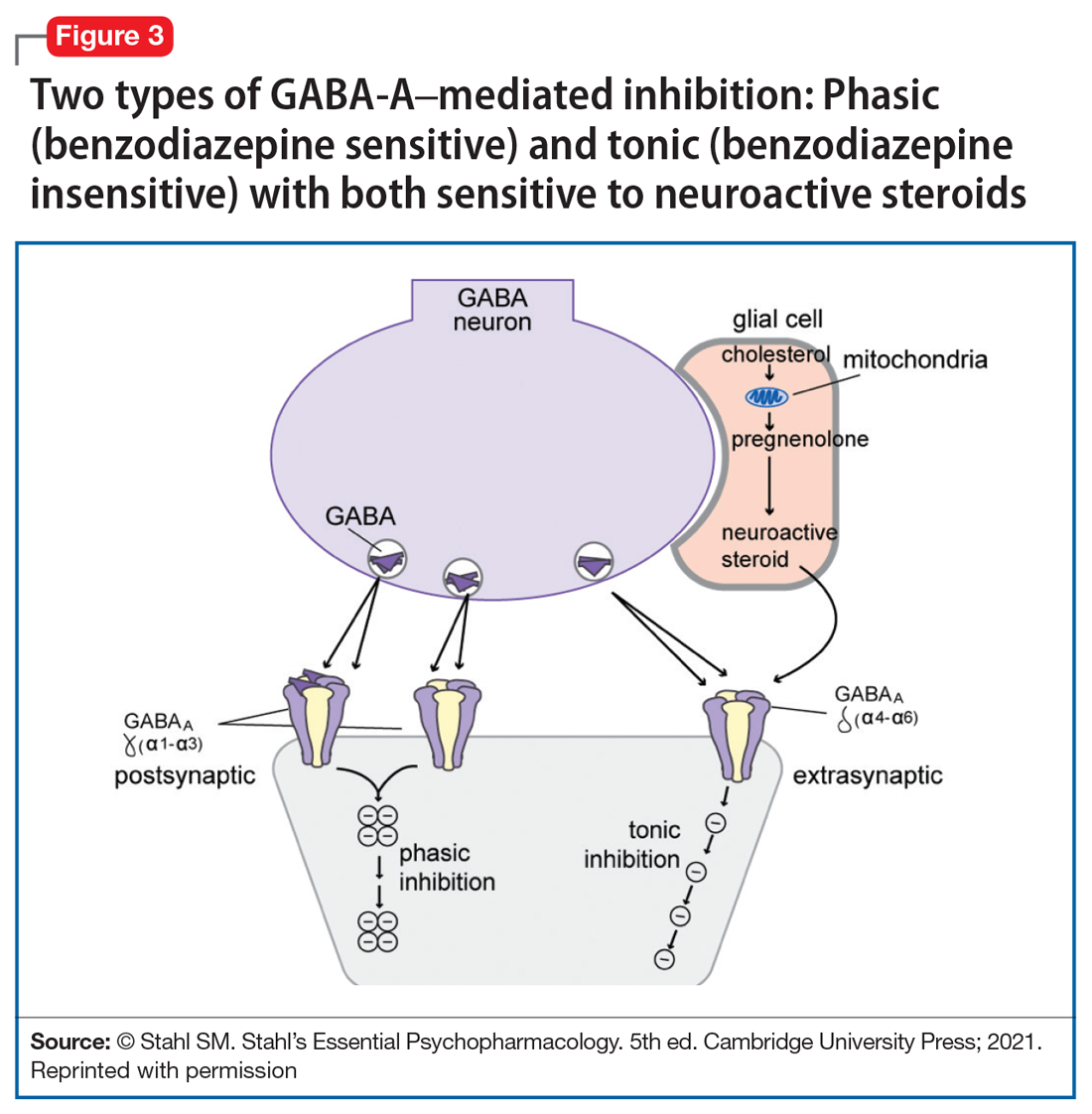

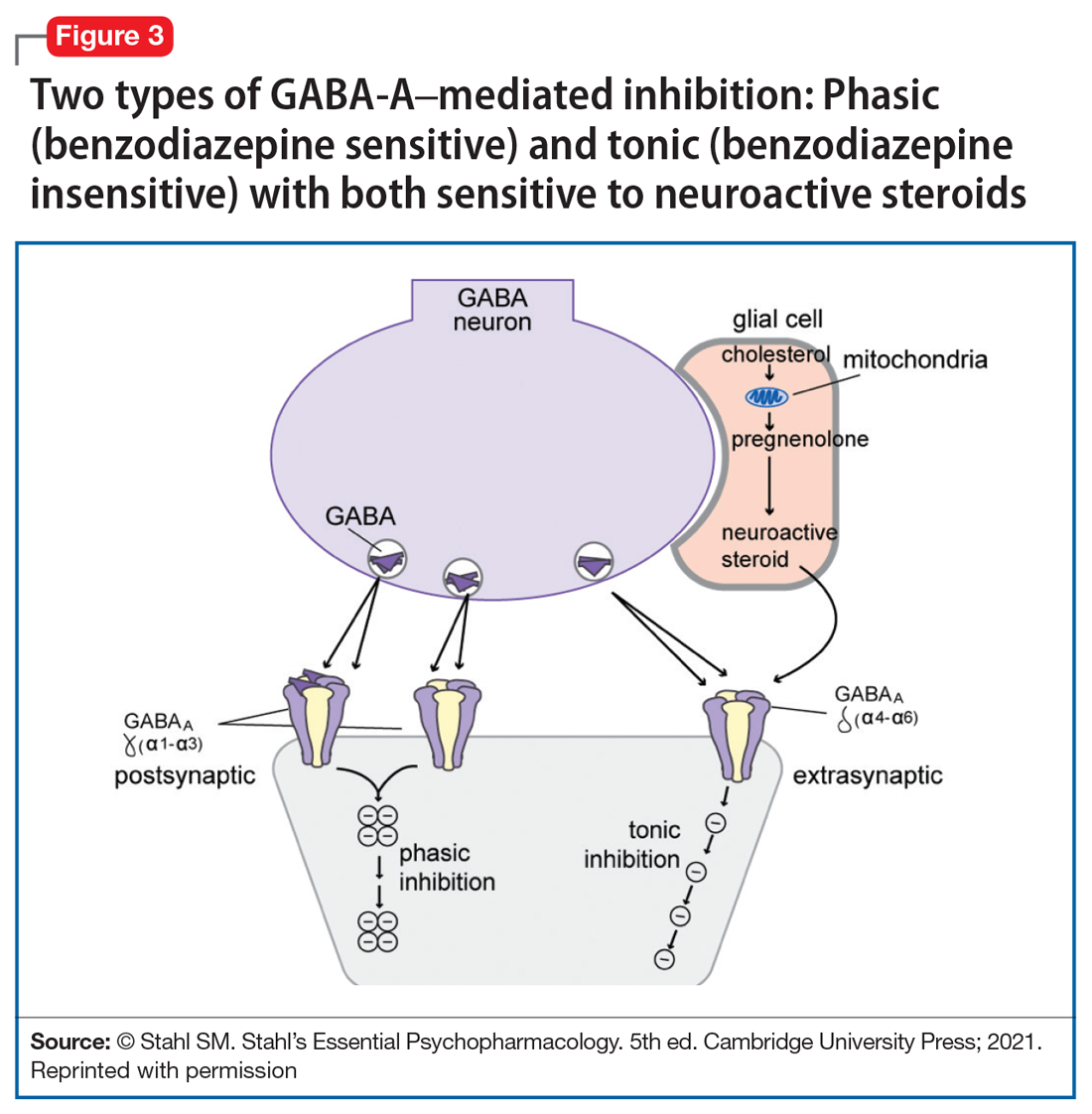

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

Adolescents, THC, and the risk of psychosis

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in Current Psychiatry. All submissions to Readers’ Forum undergo peer review and are subject to editing for length and style. For more information, contact [email protected].

Since the recent legalization and decriminalization of cannabis (marijuana) use throughout the United States, adolescents’ access to, and use of, cannabis has increased.1 Cannabis products have been marketed in ways that attract adolescents, such as edible gummies, cookies, and hard candies, as well as by vaping.1 The adolescent years are a delicate period of development during which individuals are prone to psychiatric illness, including depression, anxiety, and psychosis.2,3 Here we discuss the relationship between adolescent cannabis use and the development of psychosis.

How cannabis can affect the adolescent brain

The 2 main psychotropic substances found within the cannabis plant are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD).1,4 Endocannabinoids are fatty acid derivatives produced in the brain that bind to cannabinoid (CB) receptors found in the brain and the peripheral nervous system.1,4

During adolescence, neurodevelopment and neurochemical balances are evolving, and it’s during this period that the bulk of prefrontal pruning occurs, especially in the glutamatergic and gamma aminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) neural pathways.5 THC affects the CB1 receptors by downregulating the neuron receptors, which then alters the maturation of the prefrontal cortical GABAergic neurons. Also, THC affects the upregulation of the microglia located on the CB2 receptors, thereby altering synaptic pruning even further.2,5

All of these changes can cause brain insults that can contribute to the precipitation of psychotic decompensation in adolescents who ingest products that contain THC. In addition, consuming THC might hasten the progression of disorder in adolescents who are genetically predisposed to psychotic disorders. However, existing studies must be interpreted with caution because there are other contributing risk factors for psychosis, such as social isolation, that can alter dopamine signaling as well as oligodendrocyte maturation, which can affect myelination in the prefrontal area of the evolving brain. Factors such as increased academic demand can alter the release of cortisol, which in turn affects the dopamine response as well as the structure of the hippocampus as it responds to cortisol. With all of these contributing factors, it is difficult to attribute psychosis in adolescents solely to the use of THC.5

How to discuss cannabis usewith adolescents

Clinicians should engage in open-ended therapeutic conversations about cannabis use with their adolescent patients, including the various types of cannabis and methods of use (ingestion vs inhalation, etc). Educate patients about the acute and long-term effects of THC use, including an increased risk of depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse in adulthood.

For a patient who has experienced a psychotic episode, early intervention has proven to result in greater treatment response and functional improvement because it reduces brain exposure to neurotoxic effects in adolescents.3 Access to community resources such as school counselors can help to create coping strategies and enhance family support, which can optimize treatment outcomes and medication adherence, all of which will minimize the likelihood of another psychotic episode. Kelleher et al6 found an increased risk of suicidal behavior after a psychotic experience from any cause in adolescents and young adults, and thereby recommended that clinicians conduct continuous assessment of suicidal ideation in such patients.

1. US Food & Drug Administration. 5 Things to know about delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol – delta-8 THC. Updated September 14, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/5-things-know-about-delta-8-tetrahy drocannabinol-delta-8-thc

2. Patel PK, Leathem LD, Currin DL, et al. Adolescent neurodevelopment and vulnerability to psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89(2):184-193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.06.028

3. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632

4. Mastrangelo M. Clinical approach to neurodegenerative disorders in childhood: an updated overview. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119(4):511-521. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01160-0

5. Sewell RA, Ranganathan M, D’Souza DC. Cannabinoids and psychosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):152-162. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782802

6. Kelleher I, Cederlöf M, Lichtenstein P. Psychotic experiences as a predictor of the natural course of suicidal ideation: a Swedish cohort study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):184-188. doi: 10.1002/wps.20131

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in Current Psychiatry. All submissions to Readers’ Forum undergo peer review and are subject to editing for length and style. For more information, contact [email protected].

Since the recent legalization and decriminalization of cannabis (marijuana) use throughout the United States, adolescents’ access to, and use of, cannabis has increased.1 Cannabis products have been marketed in ways that attract adolescents, such as edible gummies, cookies, and hard candies, as well as by vaping.1 The adolescent years are a delicate period of development during which individuals are prone to psychiatric illness, including depression, anxiety, and psychosis.2,3 Here we discuss the relationship between adolescent cannabis use and the development of psychosis.

How cannabis can affect the adolescent brain

The 2 main psychotropic substances found within the cannabis plant are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD).1,4 Endocannabinoids are fatty acid derivatives produced in the brain that bind to cannabinoid (CB) receptors found in the brain and the peripheral nervous system.1,4

During adolescence, neurodevelopment and neurochemical balances are evolving, and it’s during this period that the bulk of prefrontal pruning occurs, especially in the glutamatergic and gamma aminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) neural pathways.5 THC affects the CB1 receptors by downregulating the neuron receptors, which then alters the maturation of the prefrontal cortical GABAergic neurons. Also, THC affects the upregulation of the microglia located on the CB2 receptors, thereby altering synaptic pruning even further.2,5

All of these changes can cause brain insults that can contribute to the precipitation of psychotic decompensation in adolescents who ingest products that contain THC. In addition, consuming THC might hasten the progression of disorder in adolescents who are genetically predisposed to psychotic disorders. However, existing studies must be interpreted with caution because there are other contributing risk factors for psychosis, such as social isolation, that can alter dopamine signaling as well as oligodendrocyte maturation, which can affect myelination in the prefrontal area of the evolving brain. Factors such as increased academic demand can alter the release of cortisol, which in turn affects the dopamine response as well as the structure of the hippocampus as it responds to cortisol. With all of these contributing factors, it is difficult to attribute psychosis in adolescents solely to the use of THC.5

How to discuss cannabis usewith adolescents

Clinicians should engage in open-ended therapeutic conversations about cannabis use with their adolescent patients, including the various types of cannabis and methods of use (ingestion vs inhalation, etc). Educate patients about the acute and long-term effects of THC use, including an increased risk of depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse in adulthood.

For a patient who has experienced a psychotic episode, early intervention has proven to result in greater treatment response and functional improvement because it reduces brain exposure to neurotoxic effects in adolescents.3 Access to community resources such as school counselors can help to create coping strategies and enhance family support, which can optimize treatment outcomes and medication adherence, all of which will minimize the likelihood of another psychotic episode. Kelleher et al6 found an increased risk of suicidal behavior after a psychotic experience from any cause in adolescents and young adults, and thereby recommended that clinicians conduct continuous assessment of suicidal ideation in such patients.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in Current Psychiatry. All submissions to Readers’ Forum undergo peer review and are subject to editing for length and style. For more information, contact [email protected].

Since the recent legalization and decriminalization of cannabis (marijuana) use throughout the United States, adolescents’ access to, and use of, cannabis has increased.1 Cannabis products have been marketed in ways that attract adolescents, such as edible gummies, cookies, and hard candies, as well as by vaping.1 The adolescent years are a delicate period of development during which individuals are prone to psychiatric illness, including depression, anxiety, and psychosis.2,3 Here we discuss the relationship between adolescent cannabis use and the development of psychosis.

How cannabis can affect the adolescent brain

The 2 main psychotropic substances found within the cannabis plant are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD).1,4 Endocannabinoids are fatty acid derivatives produced in the brain that bind to cannabinoid (CB) receptors found in the brain and the peripheral nervous system.1,4

During adolescence, neurodevelopment and neurochemical balances are evolving, and it’s during this period that the bulk of prefrontal pruning occurs, especially in the glutamatergic and gamma aminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) neural pathways.5 THC affects the CB1 receptors by downregulating the neuron receptors, which then alters the maturation of the prefrontal cortical GABAergic neurons. Also, THC affects the upregulation of the microglia located on the CB2 receptors, thereby altering synaptic pruning even further.2,5

All of these changes can cause brain insults that can contribute to the precipitation of psychotic decompensation in adolescents who ingest products that contain THC. In addition, consuming THC might hasten the progression of disorder in adolescents who are genetically predisposed to psychotic disorders. However, existing studies must be interpreted with caution because there are other contributing risk factors for psychosis, such as social isolation, that can alter dopamine signaling as well as oligodendrocyte maturation, which can affect myelination in the prefrontal area of the evolving brain. Factors such as increased academic demand can alter the release of cortisol, which in turn affects the dopamine response as well as the structure of the hippocampus as it responds to cortisol. With all of these contributing factors, it is difficult to attribute psychosis in adolescents solely to the use of THC.5

How to discuss cannabis usewith adolescents

Clinicians should engage in open-ended therapeutic conversations about cannabis use with their adolescent patients, including the various types of cannabis and methods of use (ingestion vs inhalation, etc). Educate patients about the acute and long-term effects of THC use, including an increased risk of depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse in adulthood.

For a patient who has experienced a psychotic episode, early intervention has proven to result in greater treatment response and functional improvement because it reduces brain exposure to neurotoxic effects in adolescents.3 Access to community resources such as school counselors can help to create coping strategies and enhance family support, which can optimize treatment outcomes and medication adherence, all of which will minimize the likelihood of another psychotic episode. Kelleher et al6 found an increased risk of suicidal behavior after a psychotic experience from any cause in adolescents and young adults, and thereby recommended that clinicians conduct continuous assessment of suicidal ideation in such patients.

1. US Food & Drug Administration. 5 Things to know about delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol – delta-8 THC. Updated September 14, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/5-things-know-about-delta-8-tetrahy drocannabinol-delta-8-thc

2. Patel PK, Leathem LD, Currin DL, et al. Adolescent neurodevelopment and vulnerability to psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89(2):184-193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.06.028

3. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632

4. Mastrangelo M. Clinical approach to neurodegenerative disorders in childhood: an updated overview. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119(4):511-521. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01160-0

5. Sewell RA, Ranganathan M, D’Souza DC. Cannabinoids and psychosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):152-162. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782802

6. Kelleher I, Cederlöf M, Lichtenstein P. Psychotic experiences as a predictor of the natural course of suicidal ideation: a Swedish cohort study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):184-188. doi: 10.1002/wps.20131

1. US Food & Drug Administration. 5 Things to know about delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol – delta-8 THC. Updated September 14, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/5-things-know-about-delta-8-tetrahy drocannabinol-delta-8-thc

2. Patel PK, Leathem LD, Currin DL, et al. Adolescent neurodevelopment and vulnerability to psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89(2):184-193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.06.028

3. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632

4. Mastrangelo M. Clinical approach to neurodegenerative disorders in childhood: an updated overview. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119(4):511-521. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01160-0

5. Sewell RA, Ranganathan M, D’Souza DC. Cannabinoids and psychosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):152-162. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782802

6. Kelleher I, Cederlöf M, Lichtenstein P. Psychotic experiences as a predictor of the natural course of suicidal ideation: a Swedish cohort study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):184-188. doi: 10.1002/wps.20131

Vaping: Understand the risks

From 2017 to 2018, the 30-day prevalence of “vaping” nicotine rose dramatically among 8th graders, 10th graders, 12th graders, college students, and young adults; the increase was the greatest among college students.1 As vaping has become a common phenomenon in our society, it is prudent to have a basic understanding of what vaping is, and its potential health risks.

How it works

Vaping is the inhaling and exhaling of aerosol that is produced by a device.2 Users can vape nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or synthetic drugs. The aerosol, often mistaken for water vapor, consists of fine particles that contain varying amounts of toxic chemicals and heavy metals that enter the lungs and bloodstream when vaping.2 In general, vaping devices consist of a mouthpiece, a battery, a cartridge for containing the e-juice/e-liquid, and a heating component that turns the e-juice/e-liquid into vapor.2 The e-juice/e-liquid usually contains a propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin-based liquid with nicotine, THC, or synthetic drugs.2 The e-juice/e-liquid also contains flavorings, additives, and other chemicals and metals (but not tobacco).2

There are 4 types of vaping devices3:

E-cigarettes. This first generation of vaping devices was introduced to US markets in 2007. E-cigarettes look similar to cigarettes and come in disposable or rechargeable forms.3 They may emit a light when the user puffs. E-cigarettes have shorter battery lives and are less expensive than other vaping devices.

Vape pens. These second-generation vaping devices resemble fountain pens. Vape pens also come in disposable and rechargeable forms.3 They can be refilled with e-juice/e-liquid.3

Vaping mods. These third-generation vaping devices were created when users modified items such as flashlights to create a more powerful vaping experience; however, these self-modifications often are unsafe. Vaping mods are larger than vape pens and e-cigarettes and include modification options. They also have large-capacity batteries that are replaceable. Vaping mods are typically rechargeable and deliver more nicotine than earlier-generation vaping devices.

Pod systems. Pod systems, such as Juul, are the latest generation of vaping devices. These small, sleek devices resemble a USB drive.3 They can be recharged on a laptop or any USB charger.3 Pods combine the portability of e-cigarettes or vape pens with the power of a mod system. There are 2 types of pod systems: open and closed. Open pod systems consist of removable pods that are filled with the user’s choice of e-juice/e-liquid and then replaced after being refilled several times. Closed pod systems are purchased pre-filled with e-juice/e-liquid and are disposable, similar to single-use coffee pods. Juul is the most popular vape brand in the United States.4 For a visual guide of the different vaping devices, see https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/pdfs/ecigarette-or-vaping-products-visual-dictionary-508.pdf

What are the risks?

Vaping is relatively new, so the long-term health effects are not well studied. Although less harmful than smoking cigarettes, vaping is still not safe because users are exposed to chemicals in the aerosol, such as nicotine, heavy metals such as lead, volatile organic compounds, and cancer-causing agents.3 Vaping nicotine can result in the same cardiac and pulmonary complications as smoking cigarettes. Vaping nicotine can also be more addictive than smoking cigarettes because users can buy cartridges with higher concentrations of nicotine or increase the vaping device’s voltage to get a greater “hit” of nicotine (or whatever substance the user is vaping.) Vaping devices can also cause unintentional injuries due to fires and explosions from defective batteries.

Vaping—particularly vaping THC—has been linked to a condition called e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI).5 As of February 18, 2020, the CDC had received reports of approximately 2,800 patients with EVALI who were hospitalized or had died.5 Most EVALI cases have been linked to e-cigarette or vaping products that contained THC, particularly products obtained from informal sources such as friends, family, or in-person or online dealers.5 Vitamin E acetate, an additive in some THC-containing vaping products, has been strongly linked to EVALI.5 When ingested as a vitamin supplement or applied to the skin, vitamin E usually is harmless, but when inhaled, it may interfere with normal lung functioning.5 The CDC recommends that individuals who vape do not use products that contain THC; avoid getting vaping products from informal sources, such as friends, family, or online dealers; and not modify or add any substances to a vaping device other than as intended by the manufacturer.5

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al; the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2018. Volume 2. College students and adults ages 19-60. Published July 2019. Accessed November 12, 2021. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2018.pdf

- Partnership to End Addiction. Vaping & e-cigarettes. Last updated May 2021. Accessed November 12, 2021. https://drugfree.org/drugs/e-cigarettes-vaping/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). Last reviewed February 24, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/about-e-cigarettes.html

- Partnership to End Addiction. What parents need to know about vaping. Published May 2020. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://drugfree.org/article/what-parents-need-to-know-about-vaping/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Last reviewed August 3, 2021. Accessed November 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#overview

From 2017 to 2018, the 30-day prevalence of “vaping” nicotine rose dramatically among 8th graders, 10th graders, 12th graders, college students, and young adults; the increase was the greatest among college students.1 As vaping has become a common phenomenon in our society, it is prudent to have a basic understanding of what vaping is, and its potential health risks.

How it works

Vaping is the inhaling and exhaling of aerosol that is produced by a device.2 Users can vape nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or synthetic drugs. The aerosol, often mistaken for water vapor, consists of fine particles that contain varying amounts of toxic chemicals and heavy metals that enter the lungs and bloodstream when vaping.2 In general, vaping devices consist of a mouthpiece, a battery, a cartridge for containing the e-juice/e-liquid, and a heating component that turns the e-juice/e-liquid into vapor.2 The e-juice/e-liquid usually contains a propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin-based liquid with nicotine, THC, or synthetic drugs.2 The e-juice/e-liquid also contains flavorings, additives, and other chemicals and metals (but not tobacco).2

There are 4 types of vaping devices3:

E-cigarettes. This first generation of vaping devices was introduced to US markets in 2007. E-cigarettes look similar to cigarettes and come in disposable or rechargeable forms.3 They may emit a light when the user puffs. E-cigarettes have shorter battery lives and are less expensive than other vaping devices.

Vape pens. These second-generation vaping devices resemble fountain pens. Vape pens also come in disposable and rechargeable forms.3 They can be refilled with e-juice/e-liquid.3

Vaping mods. These third-generation vaping devices were created when users modified items such as flashlights to create a more powerful vaping experience; however, these self-modifications often are unsafe. Vaping mods are larger than vape pens and e-cigarettes and include modification options. They also have large-capacity batteries that are replaceable. Vaping mods are typically rechargeable and deliver more nicotine than earlier-generation vaping devices.

Pod systems. Pod systems, such as Juul, are the latest generation of vaping devices. These small, sleek devices resemble a USB drive.3 They can be recharged on a laptop or any USB charger.3 Pods combine the portability of e-cigarettes or vape pens with the power of a mod system. There are 2 types of pod systems: open and closed. Open pod systems consist of removable pods that are filled with the user’s choice of e-juice/e-liquid and then replaced after being refilled several times. Closed pod systems are purchased pre-filled with e-juice/e-liquid and are disposable, similar to single-use coffee pods. Juul is the most popular vape brand in the United States.4 For a visual guide of the different vaping devices, see https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/pdfs/ecigarette-or-vaping-products-visual-dictionary-508.pdf

What are the risks?

Vaping is relatively new, so the long-term health effects are not well studied. Although less harmful than smoking cigarettes, vaping is still not safe because users are exposed to chemicals in the aerosol, such as nicotine, heavy metals such as lead, volatile organic compounds, and cancer-causing agents.3 Vaping nicotine can result in the same cardiac and pulmonary complications as smoking cigarettes. Vaping nicotine can also be more addictive than smoking cigarettes because users can buy cartridges with higher concentrations of nicotine or increase the vaping device’s voltage to get a greater “hit” of nicotine (or whatever substance the user is vaping.) Vaping devices can also cause unintentional injuries due to fires and explosions from defective batteries.

Vaping—particularly vaping THC—has been linked to a condition called e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI).5 As of February 18, 2020, the CDC had received reports of approximately 2,800 patients with EVALI who were hospitalized or had died.5 Most EVALI cases have been linked to e-cigarette or vaping products that contained THC, particularly products obtained from informal sources such as friends, family, or in-person or online dealers.5 Vitamin E acetate, an additive in some THC-containing vaping products, has been strongly linked to EVALI.5 When ingested as a vitamin supplement or applied to the skin, vitamin E usually is harmless, but when inhaled, it may interfere with normal lung functioning.5 The CDC recommends that individuals who vape do not use products that contain THC; avoid getting vaping products from informal sources, such as friends, family, or online dealers; and not modify or add any substances to a vaping device other than as intended by the manufacturer.5

From 2017 to 2018, the 30-day prevalence of “vaping” nicotine rose dramatically among 8th graders, 10th graders, 12th graders, college students, and young adults; the increase was the greatest among college students.1 As vaping has become a common phenomenon in our society, it is prudent to have a basic understanding of what vaping is, and its potential health risks.

How it works

Vaping is the inhaling and exhaling of aerosol that is produced by a device.2 Users can vape nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or synthetic drugs. The aerosol, often mistaken for water vapor, consists of fine particles that contain varying amounts of toxic chemicals and heavy metals that enter the lungs and bloodstream when vaping.2 In general, vaping devices consist of a mouthpiece, a battery, a cartridge for containing the e-juice/e-liquid, and a heating component that turns the e-juice/e-liquid into vapor.2 The e-juice/e-liquid usually contains a propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin-based liquid with nicotine, THC, or synthetic drugs.2 The e-juice/e-liquid also contains flavorings, additives, and other chemicals and metals (but not tobacco).2

There are 4 types of vaping devices3:

E-cigarettes. This first generation of vaping devices was introduced to US markets in 2007. E-cigarettes look similar to cigarettes and come in disposable or rechargeable forms.3 They may emit a light when the user puffs. E-cigarettes have shorter battery lives and are less expensive than other vaping devices.

Vape pens. These second-generation vaping devices resemble fountain pens. Vape pens also come in disposable and rechargeable forms.3 They can be refilled with e-juice/e-liquid.3

Vaping mods. These third-generation vaping devices were created when users modified items such as flashlights to create a more powerful vaping experience; however, these self-modifications often are unsafe. Vaping mods are larger than vape pens and e-cigarettes and include modification options. They also have large-capacity batteries that are replaceable. Vaping mods are typically rechargeable and deliver more nicotine than earlier-generation vaping devices.

Pod systems. Pod systems, such as Juul, are the latest generation of vaping devices. These small, sleek devices resemble a USB drive.3 They can be recharged on a laptop or any USB charger.3 Pods combine the portability of e-cigarettes or vape pens with the power of a mod system. There are 2 types of pod systems: open and closed. Open pod systems consist of removable pods that are filled with the user’s choice of e-juice/e-liquid and then replaced after being refilled several times. Closed pod systems are purchased pre-filled with e-juice/e-liquid and are disposable, similar to single-use coffee pods. Juul is the most popular vape brand in the United States.4 For a visual guide of the different vaping devices, see https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/pdfs/ecigarette-or-vaping-products-visual-dictionary-508.pdf

What are the risks?

Vaping is relatively new, so the long-term health effects are not well studied. Although less harmful than smoking cigarettes, vaping is still not safe because users are exposed to chemicals in the aerosol, such as nicotine, heavy metals such as lead, volatile organic compounds, and cancer-causing agents.3 Vaping nicotine can result in the same cardiac and pulmonary complications as smoking cigarettes. Vaping nicotine can also be more addictive than smoking cigarettes because users can buy cartridges with higher concentrations of nicotine or increase the vaping device’s voltage to get a greater “hit” of nicotine (or whatever substance the user is vaping.) Vaping devices can also cause unintentional injuries due to fires and explosions from defective batteries.

Vaping—particularly vaping THC—has been linked to a condition called e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI).5 As of February 18, 2020, the CDC had received reports of approximately 2,800 patients with EVALI who were hospitalized or had died.5 Most EVALI cases have been linked to e-cigarette or vaping products that contained THC, particularly products obtained from informal sources such as friends, family, or in-person or online dealers.5 Vitamin E acetate, an additive in some THC-containing vaping products, has been strongly linked to EVALI.5 When ingested as a vitamin supplement or applied to the skin, vitamin E usually is harmless, but when inhaled, it may interfere with normal lung functioning.5 The CDC recommends that individuals who vape do not use products that contain THC; avoid getting vaping products from informal sources, such as friends, family, or online dealers; and not modify or add any substances to a vaping device other than as intended by the manufacturer.5

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al; the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2018. Volume 2. College students and adults ages 19-60. Published July 2019. Accessed November 12, 2021. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2018.pdf

- Partnership to End Addiction. Vaping & e-cigarettes. Last updated May 2021. Accessed November 12, 2021. https://drugfree.org/drugs/e-cigarettes-vaping/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). Last reviewed February 24, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/about-e-cigarettes.html

- Partnership to End Addiction. What parents need to know about vaping. Published May 2020. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://drugfree.org/article/what-parents-need-to-know-about-vaping/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Last reviewed August 3, 2021. Accessed November 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#overview

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al; the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2018. Volume 2. College students and adults ages 19-60. Published July 2019. Accessed November 12, 2021. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2018.pdf

- Partnership to End Addiction. Vaping & e-cigarettes. Last updated May 2021. Accessed November 12, 2021. https://drugfree.org/drugs/e-cigarettes-vaping/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). Last reviewed February 24, 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/about-e-cigarettes.html

- Partnership to End Addiction. What parents need to know about vaping. Published May 2020. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://drugfree.org/article/what-parents-need-to-know-about-vaping/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Last reviewed August 3, 2021. Accessed November 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#overview

Serotonin-mediated anxiety: How to recognize and treat it

Sara R. Abell, MD, and Rif S. El-Mallakh, MD

Individuals with anxiety will experience frequent or chronic excessive worry, nervousness, a sense of unease, a feeling of being unfocused, and distress, which result in functional impairment.1 Frequently, anxiety is accompanied by restlessness or muscle tension. Generalized anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses in the United States and has a prevalence of 2% to 6% globally.2 Although research has been conducted regarding anxiety’s pathogenesis, to date a firm consensus on its etiology has not been reached.3 It is likely multifactorial, with environmental and biologic components.

One area of focus has been neurotransmitters and the possible role they play in the pathogenesis of anxiety. Specifically, the monoamine neurotransmitters have been implicated in the clinical manifestations of anxiety. Among the amines, normal roles include stimulating the autonomic nervous system and regulating numerous cognitive phenomena, such as volition and emotion. Many psychiatric medications modify aminergic transmission, and many current anxiety medications target amine neurotransmitters. Medications that target histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine all play a role in treating anxiety.

In this article, we focus on serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) as a mediator of anxiety and on excessive synaptic 5-HT as the cause of anxiety. We discuss how 5-HT–mediated anxiety can be identified and offer some solutions for its treatment.

The amine neurotransmitters

There are 6 amine neurotransmitters in the CNS. These are derived from tyrosine (dopamine [DA], norepinephrine [NE], and epinephrine), histidine (histamine), and tryptophan (serotonin [5-HT] and melatonin). In addition to their physiologic actions, amines have been implicated in both acute and chronic anxiety. Excessive DA stimulation has been linked with fear4,5; NE elevations are central to hypervigilance and hyperarousal of posttraumatic stress disorder6; and histamine may mediate emotional memories involved in fear and anxiety.7 Understanding the normal function of 5-HT will aid in understanding its potential problematic role (Box,8-18page 38).

How serotonin-mediated anxiety presents

“Anxiety” is a collection of signs and symptoms that likely represent multiple processes and have the common characteristic of being subjectively unpleasant, with a subjective wish for the feeling to end. The expression of anxiety disorders is quite diverse and ranges from brief episodes such as panic attacks (which may be mediated, in part, by epinephrine/NE19) to lifelong stereotypic obsessions and compulsions (which may be mediated, in part, by DA and modified by 5-HT20,21). Biochemical separation of the anxiety disorders is key to achieving tailored treatment.6 Towards this end, it is important to investigate the phenomenon of serotonin-mediated anxiety.

Because clinicians are familiar with reductions of anxiety as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase 5-HT levels in the synapse, it is difficult to conceptualize serotonin-mediated anxiety. However, many of the effects at postsynaptic 5-HT receptors may be biphasic.15-18 Serotonin-mediated anxiety appears to occur when levels of 5-HT (or stimulation of 5-HT receptors) are particularly high. This is most frequently seen in patients who genetically have high synaptic 5-HT (by virtue of the short form of the 5-HT transporter),22 whose synaptic 5-HT is further increased by treatment with an SSRI,23 and who are experiencing a stressor that yet further increases their synaptic 5-HT.24 However, it may occur in some individuals with only 2 of these 3 conditions.Clinically, individuals with serotonin-mediated anxiety will usually appear calm. The anxiety they are experiencing is not exhibited in any way in the motor system (ie, they do not appear restless, do not pace, muscle tone is not increased, etc.). However, they will generally complain of an internal agitation, a sense of a negative internal energy. Frequently, they will use descriptions such as “I feel I could jump out of my skin.” As previously mentioned, this is usually in the setting of some environmental stress, in addition to either a pharmacologic (SSRI) or genetic (short form of the 5-HT transporter) reason for increasing synaptic 5-HT, or both.

Almost always, interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of the SSRI (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety, quickly or more slowly, respectively. Sublingual asenapine, which at low doses can block 5-HT2C (Ki = 0.03 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 0.07 nM), 5-HT7 (Ki = 0.11 nM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.18 nM), and 5-HT6 (Ki = 0.25 nM),25,26 and which will produce peak plasma levels within 10 minutes,27 usually is quite effective.

Box

Serotonin (5-HT) arises from neurons in the raphe nuclei of the rostral pons and projects superiorly to the cerebral cortex and inferiorly to the spinal cord.8 It works in an inhibitory or excitatory manner depending on which receptors are activated. In the periphery, 5-HT influences intestinal peristalsis, sensory modulation, gland function, thermoregulation, blood pressure, platelet aggregation, and sexual behavior,9 all actions that produce potential adverse effects of serotonin reuptake– inhibiting antidepressants. In the CNS, 5-HT plays a role in attention bias; decision-making; sleep and wakefulness; and mood regulation. In short, serotonin can be viewed as mediating emotional motivation.10

Serotonin alters neuroplasticity. During development, 5-HT stimulates creation of new synapses and increases the density of synaptic webs. It has a direct stimulatory effect on the length of dendrites, their branching, and their myelination.11 In the CNS, it plays a role in dendritic arborization. Animal studies with rats have shown that lesioning highly concentrated 5-HT areas at early ages resulted in an adult brain with a lower number of neurons and a less complex web of dendrites.12,13 In situations of emotional stress, it is theorized that low levels of 5-HT lead to a reduced ability to deal with emotional stressors due to lower levels of complexity in synaptic connections.

Serotonin has also been implicated in mediating some aspects of dopamine-related actions, such as locomotion, reward, and threat avoidance. This is believed to contribute to the beneficial effect of 5-HT2A blockade by secondgeneration antipsychotics (SGAs).14 Blockade of other 5-HT receptors, such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7, may also contribute to the antipsychotic action of SGAs.14

Serotonin receptors are found throughout the body, and 14 subtypes have been identified.9 Excitatory and inhibitory action of 5-HT depends on the receptor, and the actions of 5-HT can differ with the same receptor at different concentrations. This is because serotonin’s effects are biphasic and concentration-dependent, meaning that levels of 5-HT in the synapse will dictate the downstream effect of receptor agonism or antagonism. Animal models have shown that low-dose agonism of 5-HT receptors causes vasoconstriction of the coronary arteries, and high doses cause relaxation. This response has also been demonstrated in the vasculature of the kidneys and the smooth muscle of the trachea. Additionally, 5-HT works in conjunction with histamine to produce a biphasic response in the colonic arteries and veins in situations of endothelial damage.15

Most relevant to this discussion are 5-HT’s actions in mood regulation and behavior. Low 5-HT states result in less behavioral inhibition, leading to higher impulse control failures and aggression. Experiments in mice with deficient serotonergic brain regions show hypoactivity, extended daytime sleep, anxiety, and depressive behaviors.13 Serotonin’s behavioral effects are also biphasic. For example, lowdose antagonism with trazodone of 5-HT receptors demonstrated a pro-aggressive behavioral effect, while high-dose antagonism is anti-aggressive.15 Similar biphasic effects may result in either induction or reduction of anxiety with agents that block or excite certain 5-HT receptors.16-18

Continue to: A key difference: No motor system involvement...

A key difference: No motor system involvement

What distinguishes 5-HT from the other amine transmitters as a mediator of anxiety is the lack of involvement of the motor system. Multiple studies in rats illustrate that exogenously augmenting 5-HT has no effect on levels of locomotor activity. Dopamine depletion is well-characterized in the motor dysfunction of Parkinson’s disease, and DA excess can cause repetitive, stereotyped movements, such as seen in tardive dyskinesia or Huntington’s disease.8 In humans, serotonin-mediated anxiety is usually without a motoric component; patients appear calm but complain of extreme anxiety or agitation. Agitation has been reported after initiation of an SSRI,29 and is more likely to occur in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30 Motoric activation has been reported in some of these studies, but does not seem to cluster with the complaint of agitation.29 The reduced number of available transporters means a chronic steady-state elevation of serotonin, because less serotonin is being removed from the synapse after it is released. This is one of the reasons patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter may be more susceptible to serotonin-mediated anxiety.

What you need to keep in mind

Pharmacologic treatment of anxiety begins with an SSRI, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), or buspirone. Second-line treatments include hydroxyzine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and quetiapine.3,31 However, clinicians need to be aware that a fraction of their patients will report anxiety that will not have any external manifestations, but will be experienced as an unpleasant internal energy. These patients may report an increase in their anxiety levels when started on an SSRI or SNRI.29,30 This anxiety is most likely mediated by increases of synaptic 5-HT. This occurs because many serotonergic receptors may have a biphasic response, so that too much stimulation is experienced as excessive internal energy.16-18 In such patients, blockade of key 5-HT receptors may reduce that internal agitation. The advantage of recognizing serotonin-mediated anxiety is that one can specifically tailor treatment to address the patient’s specific physiology.

It is important to note that the anxiolytic effect of asenapine is specific to patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety. Unlike quetiapine, which is effective as augmentation therapy in generalized anxiety disorder,31 asenapine does not appear to reduce anxiety in patients with schizophrenia32 or borderline personality disorder33 when administered for other reasons. However, it may reduce anxiety in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30,34

Bottom Line

Serotonin-mediated anxiety occurs when levels of synaptic serotonin (5-HT) are high. Patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety appear calm but will report experiencing an unpleasant internal energy. Interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety.

Related Resource

• Bhatt NV. Anxiety disorders. https://emedicine.medscape. com/article/286227-overview

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine • Saphris, Secuado

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Trazodone • Oleptro

1. Shelton CI. Diagnosis and management of anxiety disorders. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104(3 Suppl 3):S2-S5.

2. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):465-475.

3. Locke AB, Kirst N, Shultz CG. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9):617-624.

4. Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Dextroamphetamine modulates the response of the human amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(6):1036-1040.

5. Colombo AC, de Oliveira AR, Reimer AE, et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms underlying catalepsy, fear and anxiety: do they interact? Behav Brain Res. 2013;257:201-207.

6. Togay B, El-Mallakh RS. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from pathophysiology to pharmacology. Curr Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):33-39.

7. Provensi G, Passani MB, Costa A, et al. Neuronal histamine and the memory of emotionally salient events. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(3):557-569.

8. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al (eds). Neuroscience. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2001.

9. Pytliak M, Vargová V, Mechírová V, et al. Serotonin receptors – from molecular biology to clinical applications. Physiol Res. 2011;60(1):15-25.

10. Meneses A, Liy-Salmeron G. Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Rev Neurosci. 2012;23(5-6):543-553.

11. Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Serotonin and brain development: role in human developmental diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56(5):479-485.

12. Towle AC, Breese GR, Mueller RA, et al. Early postnatal administration of 5,7-DHT: effects on serotonergic neurons and terminals. Brain Res. 1984;310(1):67-75.

13. Rok-Bujko P, Krzs´cik P, Szyndler J, et al. The influence of neonatal serotonin depletion on emotional and exploratory behaviours in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2012;226(1):87-95.

14. Meltzer HY. The role of serotonin in antipsychotic drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):106S-115S.

15. Calabrese EJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin): biphasic dose responses. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2001;31(4-5):553-561.

16. Zuardi AW. 5-HT-related drugs and human experimental anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14(4):507-510.

17. Sánchez C, Meier E. Behavioral profiles of SSRIs in animal models of depression, anxiety and aggression. Are they all alike? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1997;129(3):197-205.

18. Koek W, Mitchell NC, Daws LC. Biphasic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on anxiety: rapid reversal of escitalopram’s anxiogenic effects in the novelty-induced hypophagia test in mice? Behav Pharmacol. 2018;29(4):365-369.

19. van Zijderveld GA, Veltman DJ, van Dyck R, et al. Epinephrine-induced panic attacks and hyperventilation. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33(1):73-78.

20. Ho EV, Thompson SL, Katzka WR, et al. Clinically effective OCD treatment prevents 5-HT1B receptor-induced repetitive behavior and striatal activation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(1):57-70.

21. Stein DJ, Costa DLC, Lochner C, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):52.

22. Luddington NS, Mandadapu A, Husk M, et al. Clinical implications of genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter region: a review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(3):93-102.

23. Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. Serotonin receptors and pathways mediate therapeutic effects and side effects. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(3):215-235.

24. Chaouloff F, Berton O, Mormède P. Serotonin and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):28S-32S.

25. Siafis S, Tzachanis D, Samara M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs: From receptor-binding profiles to metabolic side effects. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(8):1210-1223.

26. Carrithers B, El-Mallakh RS. Transdermal asenapine in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1541-1551.

27. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part I: chemistry, receptor affinity profile, pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(6):893-903.

28. Pratts M, Citrome L, Grant W, et al. A single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sublingual asenapine for acute agitation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(1):61-68.

29. Biswas AB, Bhaumik S, Branford D. Treatment-emergent behavioural side effects with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in adults with learning disabilities. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(2):133-137.

30. Perlis RH, Mischoulon D, Smoller JW, et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and adverse effects with fluoxetine treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(9):879-883.

31. Ipser JC, Carey P, Dhansay Y, et al. Pharmacotherapy augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005473.

32. Kane JM, Mackle M, Snow-Adami L, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of asenapine for the prevention of relapse of schizophrenia after long-term treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):349-355.

33. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819.

34. El-Mallakh RS, Nuss S, Gao D, et al. Asenapine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2020;50(1):8-18.

Sara R. Abell, MD, and Rif S. El-Mallakh, MD

Individuals with anxiety will experience frequent or chronic excessive worry, nervousness, a sense of unease, a feeling of being unfocused, and distress, which result in functional impairment.1 Frequently, anxiety is accompanied by restlessness or muscle tension. Generalized anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses in the United States and has a prevalence of 2% to 6% globally.2 Although research has been conducted regarding anxiety’s pathogenesis, to date a firm consensus on its etiology has not been reached.3 It is likely multifactorial, with environmental and biologic components.

One area of focus has been neurotransmitters and the possible role they play in the pathogenesis of anxiety. Specifically, the monoamine neurotransmitters have been implicated in the clinical manifestations of anxiety. Among the amines, normal roles include stimulating the autonomic nervous system and regulating numerous cognitive phenomena, such as volition and emotion. Many psychiatric medications modify aminergic transmission, and many current anxiety medications target amine neurotransmitters. Medications that target histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine all play a role in treating anxiety.

In this article, we focus on serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) as a mediator of anxiety and on excessive synaptic 5-HT as the cause of anxiety. We discuss how 5-HT–mediated anxiety can be identified and offer some solutions for its treatment.

The amine neurotransmitters

There are 6 amine neurotransmitters in the CNS. These are derived from tyrosine (dopamine [DA], norepinephrine [NE], and epinephrine), histidine (histamine), and tryptophan (serotonin [5-HT] and melatonin). In addition to their physiologic actions, amines have been implicated in both acute and chronic anxiety. Excessive DA stimulation has been linked with fear4,5; NE elevations are central to hypervigilance and hyperarousal of posttraumatic stress disorder6; and histamine may mediate emotional memories involved in fear and anxiety.7 Understanding the normal function of 5-HT will aid in understanding its potential problematic role (Box,8-18page 38).

How serotonin-mediated anxiety presents

“Anxiety” is a collection of signs and symptoms that likely represent multiple processes and have the common characteristic of being subjectively unpleasant, with a subjective wish for the feeling to end. The expression of anxiety disorders is quite diverse and ranges from brief episodes such as panic attacks (which may be mediated, in part, by epinephrine/NE19) to lifelong stereotypic obsessions and compulsions (which may be mediated, in part, by DA and modified by 5-HT20,21). Biochemical separation of the anxiety disorders is key to achieving tailored treatment.6 Towards this end, it is important to investigate the phenomenon of serotonin-mediated anxiety.

Because clinicians are familiar with reductions of anxiety as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase 5-HT levels in the synapse, it is difficult to conceptualize serotonin-mediated anxiety. However, many of the effects at postsynaptic 5-HT receptors may be biphasic.15-18 Serotonin-mediated anxiety appears to occur when levels of 5-HT (or stimulation of 5-HT receptors) are particularly high. This is most frequently seen in patients who genetically have high synaptic 5-HT (by virtue of the short form of the 5-HT transporter),22 whose synaptic 5-HT is further increased by treatment with an SSRI,23 and who are experiencing a stressor that yet further increases their synaptic 5-HT.24 However, it may occur in some individuals with only 2 of these 3 conditions.Clinically, individuals with serotonin-mediated anxiety will usually appear calm. The anxiety they are experiencing is not exhibited in any way in the motor system (ie, they do not appear restless, do not pace, muscle tone is not increased, etc.). However, they will generally complain of an internal agitation, a sense of a negative internal energy. Frequently, they will use descriptions such as “I feel I could jump out of my skin.” As previously mentioned, this is usually in the setting of some environmental stress, in addition to either a pharmacologic (SSRI) or genetic (short form of the 5-HT transporter) reason for increasing synaptic 5-HT, or both.

Almost always, interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of the SSRI (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety, quickly or more slowly, respectively. Sublingual asenapine, which at low doses can block 5-HT2C (Ki = 0.03 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 0.07 nM), 5-HT7 (Ki = 0.11 nM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.18 nM), and 5-HT6 (Ki = 0.25 nM),25,26 and which will produce peak plasma levels within 10 minutes,27 usually is quite effective.

Box

Serotonin (5-HT) arises from neurons in the raphe nuclei of the rostral pons and projects superiorly to the cerebral cortex and inferiorly to the spinal cord.8 It works in an inhibitory or excitatory manner depending on which receptors are activated. In the periphery, 5-HT influences intestinal peristalsis, sensory modulation, gland function, thermoregulation, blood pressure, platelet aggregation, and sexual behavior,9 all actions that produce potential adverse effects of serotonin reuptake– inhibiting antidepressants. In the CNS, 5-HT plays a role in attention bias; decision-making; sleep and wakefulness; and mood regulation. In short, serotonin can be viewed as mediating emotional motivation.10

Serotonin alters neuroplasticity. During development, 5-HT stimulates creation of new synapses and increases the density of synaptic webs. It has a direct stimulatory effect on the length of dendrites, their branching, and their myelination.11 In the CNS, it plays a role in dendritic arborization. Animal studies with rats have shown that lesioning highly concentrated 5-HT areas at early ages resulted in an adult brain with a lower number of neurons and a less complex web of dendrites.12,13 In situations of emotional stress, it is theorized that low levels of 5-HT lead to a reduced ability to deal with emotional stressors due to lower levels of complexity in synaptic connections.

Serotonin has also been implicated in mediating some aspects of dopamine-related actions, such as locomotion, reward, and threat avoidance. This is believed to contribute to the beneficial effect of 5-HT2A blockade by secondgeneration antipsychotics (SGAs).14 Blockade of other 5-HT receptors, such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7, may also contribute to the antipsychotic action of SGAs.14

Serotonin receptors are found throughout the body, and 14 subtypes have been identified.9 Excitatory and inhibitory action of 5-HT depends on the receptor, and the actions of 5-HT can differ with the same receptor at different concentrations. This is because serotonin’s effects are biphasic and concentration-dependent, meaning that levels of 5-HT in the synapse will dictate the downstream effect of receptor agonism or antagonism. Animal models have shown that low-dose agonism of 5-HT receptors causes vasoconstriction of the coronary arteries, and high doses cause relaxation. This response has also been demonstrated in the vasculature of the kidneys and the smooth muscle of the trachea. Additionally, 5-HT works in conjunction with histamine to produce a biphasic response in the colonic arteries and veins in situations of endothelial damage.15

Most relevant to this discussion are 5-HT’s actions in mood regulation and behavior. Low 5-HT states result in less behavioral inhibition, leading to higher impulse control failures and aggression. Experiments in mice with deficient serotonergic brain regions show hypoactivity, extended daytime sleep, anxiety, and depressive behaviors.13 Serotonin’s behavioral effects are also biphasic. For example, lowdose antagonism with trazodone of 5-HT receptors demonstrated a pro-aggressive behavioral effect, while high-dose antagonism is anti-aggressive.15 Similar biphasic effects may result in either induction or reduction of anxiety with agents that block or excite certain 5-HT receptors.16-18

Continue to: A key difference: No motor system involvement...

A key difference: No motor system involvement

What distinguishes 5-HT from the other amine transmitters as a mediator of anxiety is the lack of involvement of the motor system. Multiple studies in rats illustrate that exogenously augmenting 5-HT has no effect on levels of locomotor activity. Dopamine depletion is well-characterized in the motor dysfunction of Parkinson’s disease, and DA excess can cause repetitive, stereotyped movements, such as seen in tardive dyskinesia or Huntington’s disease.8 In humans, serotonin-mediated anxiety is usually without a motoric component; patients appear calm but complain of extreme anxiety or agitation. Agitation has been reported after initiation of an SSRI,29 and is more likely to occur in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30 Motoric activation has been reported in some of these studies, but does not seem to cluster with the complaint of agitation.29 The reduced number of available transporters means a chronic steady-state elevation of serotonin, because less serotonin is being removed from the synapse after it is released. This is one of the reasons patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter may be more susceptible to serotonin-mediated anxiety.

What you need to keep in mind

Pharmacologic treatment of anxiety begins with an SSRI, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), or buspirone. Second-line treatments include hydroxyzine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and quetiapine.3,31 However, clinicians need to be aware that a fraction of their patients will report anxiety that will not have any external manifestations, but will be experienced as an unpleasant internal energy. These patients may report an increase in their anxiety levels when started on an SSRI or SNRI.29,30 This anxiety is most likely mediated by increases of synaptic 5-HT. This occurs because many serotonergic receptors may have a biphasic response, so that too much stimulation is experienced as excessive internal energy.16-18 In such patients, blockade of key 5-HT receptors may reduce that internal agitation. The advantage of recognizing serotonin-mediated anxiety is that one can specifically tailor treatment to address the patient’s specific physiology.

It is important to note that the anxiolytic effect of asenapine is specific to patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety. Unlike quetiapine, which is effective as augmentation therapy in generalized anxiety disorder,31 asenapine does not appear to reduce anxiety in patients with schizophrenia32 or borderline personality disorder33 when administered for other reasons. However, it may reduce anxiety in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30,34

Bottom Line

Serotonin-mediated anxiety occurs when levels of synaptic serotonin (5-HT) are high. Patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety appear calm but will report experiencing an unpleasant internal energy. Interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety.

Related Resource

• Bhatt NV. Anxiety disorders. https://emedicine.medscape. com/article/286227-overview

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine • Saphris, Secuado

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Trazodone • Oleptro

Sara R. Abell, MD, and Rif S. El-Mallakh, MD

Individuals with anxiety will experience frequent or chronic excessive worry, nervousness, a sense of unease, a feeling of being unfocused, and distress, which result in functional impairment.1 Frequently, anxiety is accompanied by restlessness or muscle tension. Generalized anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses in the United States and has a prevalence of 2% to 6% globally.2 Although research has been conducted regarding anxiety’s pathogenesis, to date a firm consensus on its etiology has not been reached.3 It is likely multifactorial, with environmental and biologic components.

One area of focus has been neurotransmitters and the possible role they play in the pathogenesis of anxiety. Specifically, the monoamine neurotransmitters have been implicated in the clinical manifestations of anxiety. Among the amines, normal roles include stimulating the autonomic nervous system and regulating numerous cognitive phenomena, such as volition and emotion. Many psychiatric medications modify aminergic transmission, and many current anxiety medications target amine neurotransmitters. Medications that target histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine all play a role in treating anxiety.