User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Needed: More studies of CSF molecular biomarkers in psychiatric disorders

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

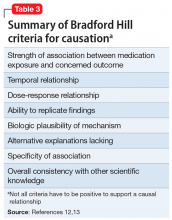

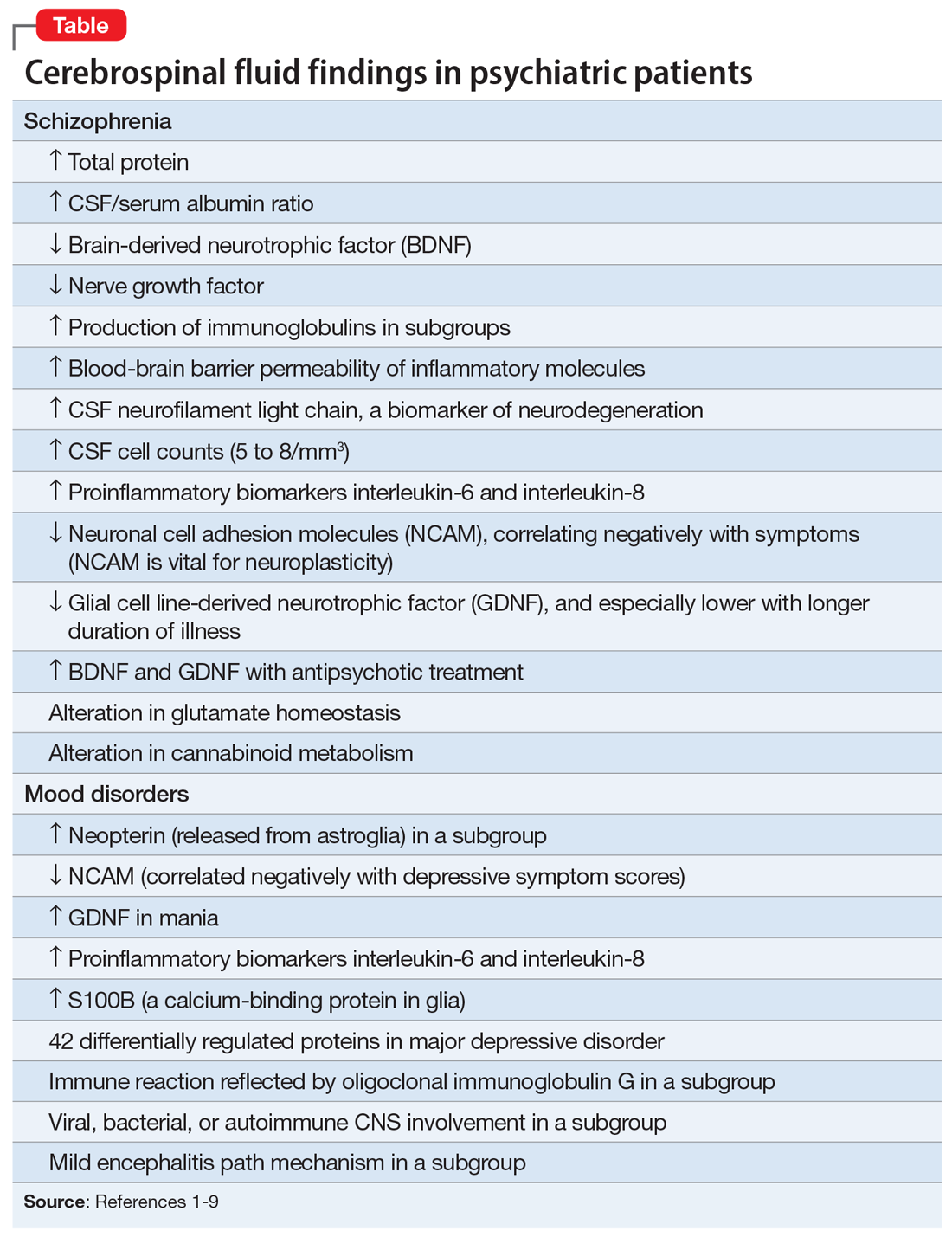

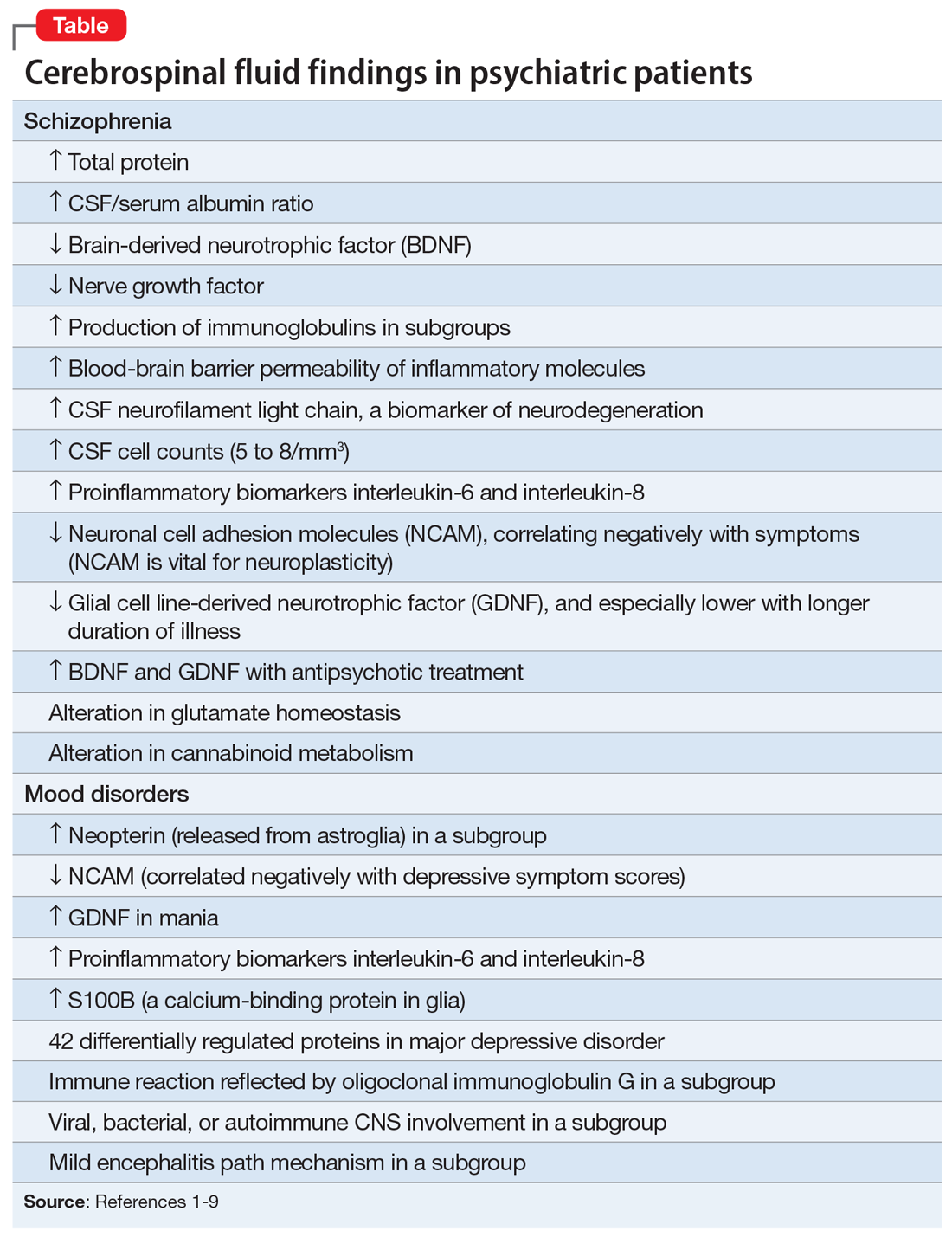

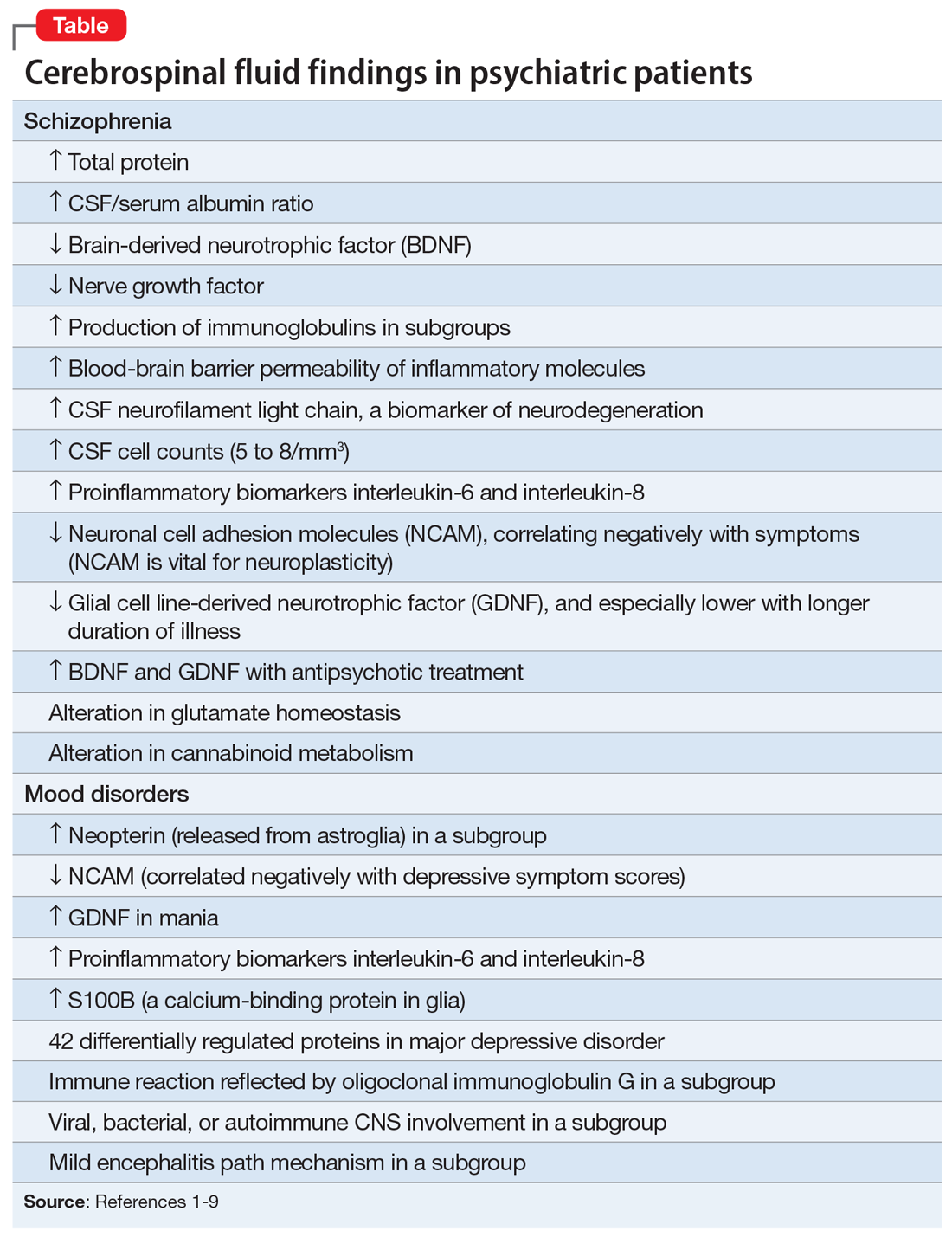

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Late-onset, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

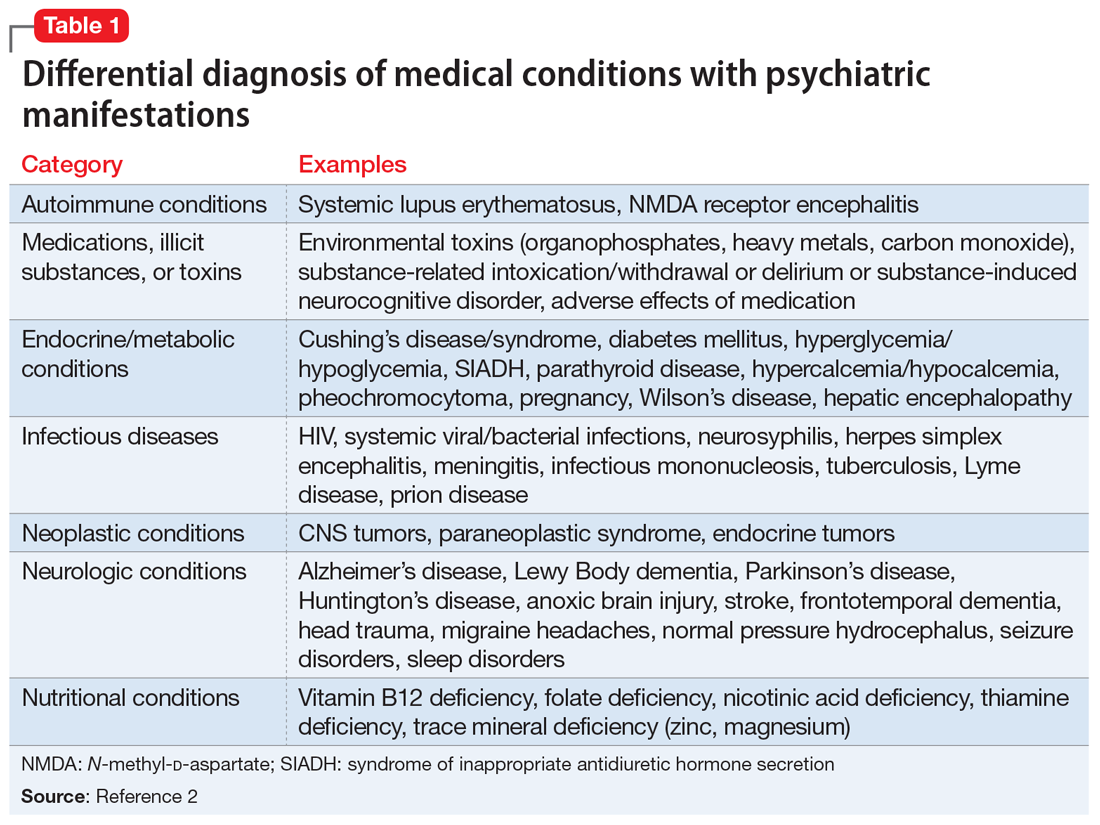

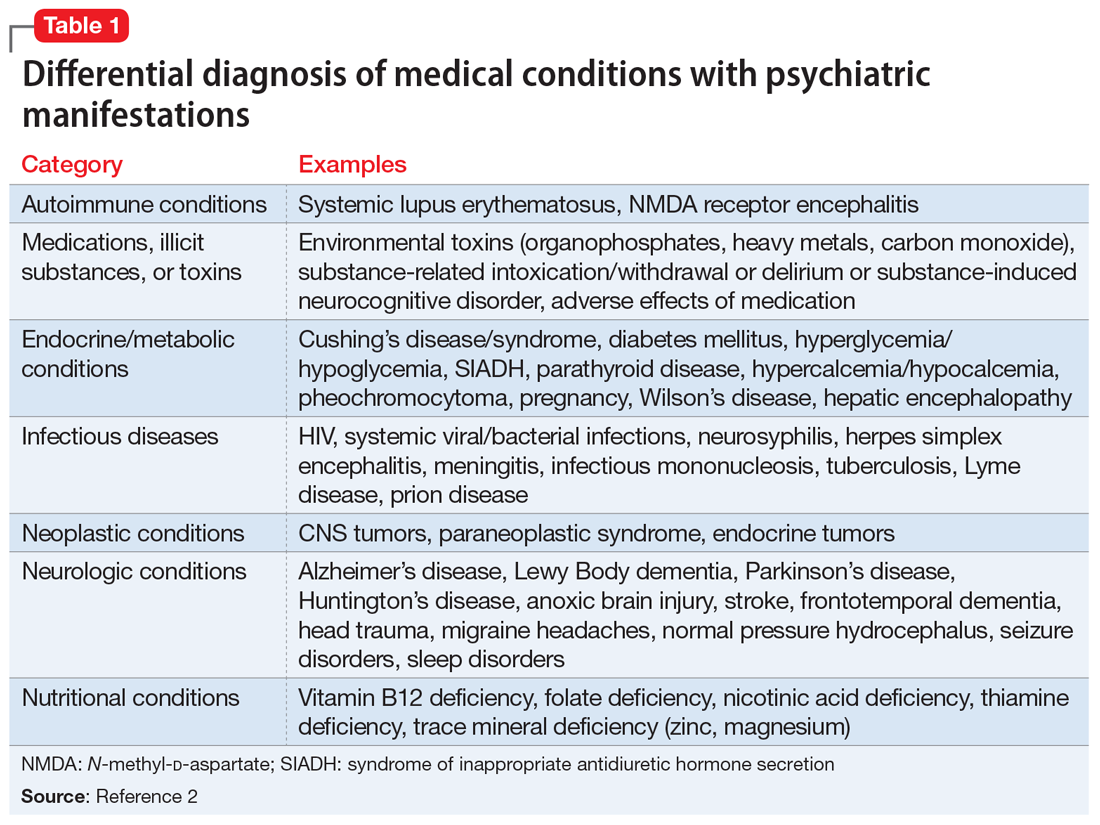

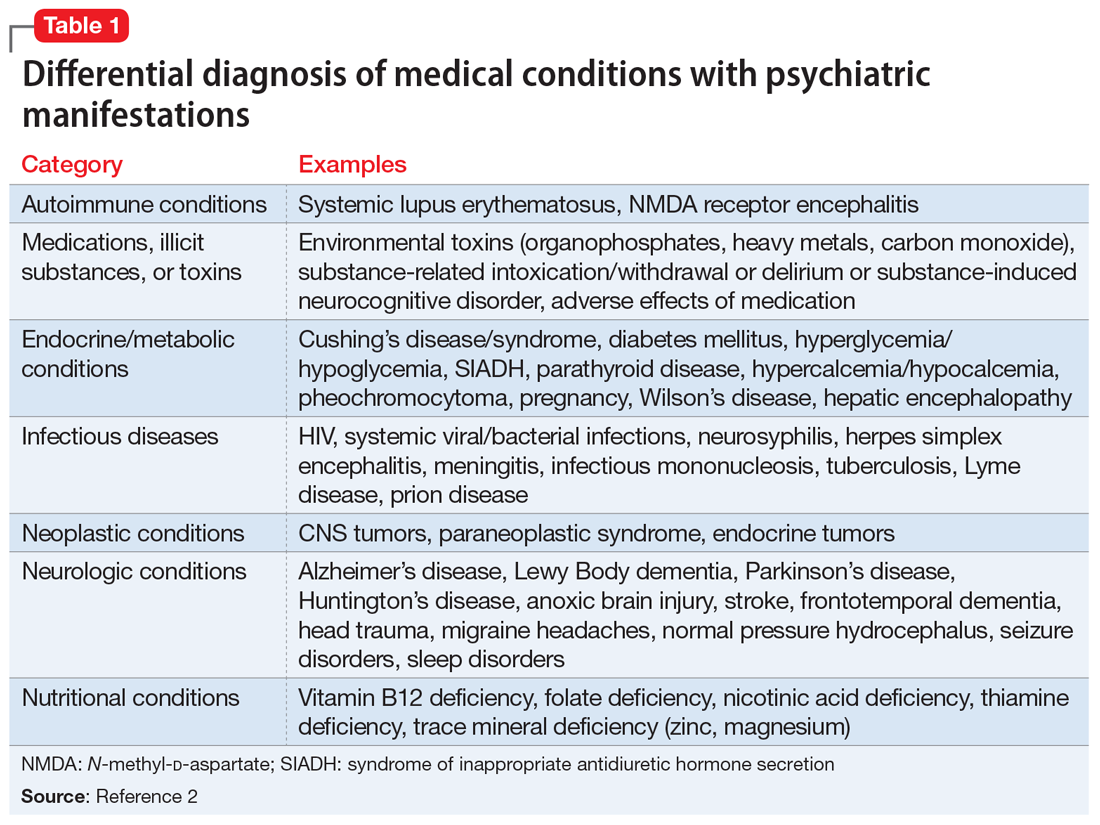

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

Medicine’s ‘Big Lie’

While today “The Big Lie” mainly refers to the actions of the prior President, an older and bigger lie that has a real effect on every American is one perpetrated by our very own health care conglomerate. Americans pay the highest rates for health care on the planet; health care consumes about 17% of our gross domestic product.1 If we got higher-quality care, faster services, longer lives, or even greater consumer happiness, paying those rates might be worth it. But we don’t.

Worse yet is the idea that “board certification” assures the public that the doctor from whom they receive/purchase care is of a higher quality than one who is not so credentialed. That is our “Big Lie!” For decades, the public has been told that they should seek out board-certified doctors. Doctors in training have been told they must get board-certified. Hospitals brag about employing only board-certified doctors, insurers sometimes mandate board certification for a doctor to get paid, and employers use board certification as a benchmark for hiring and as a factor in compensation.

The sacred secret is that board certification makes no difference. There is no substantial evidence in any branch of medicine that doctors who are board-certified are better. There is no evidence that board-certified doctors get their patients healthier with more frequency, faster, less expensively, or with fewer medical errors than other doctors. The reality is that board certification is a sham. It’s a certificate granted after taking a very expensive test, and it is now part of an industry that is misleading the public and harming the trust the medical profession had once earned. Board certification is the equivalent of a diploma mill or an online certificate in any other field.

Why has this been kept under wraps for so long? Follow the money. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) oversees 24 specialty boards and reported revenue of $22.2M and expenses of $19.3M on its 2019 IRS Form 990.2 They make profit every year. But, looking further, these “not-for-profit” educational entities are sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars in their “foundations.” Take the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, for instance. They had more than $140M in assets in 2019.3 How is this possible? Easy. They have misled the American public and been remarkably successful convincing other organizations, such as the Joint Commission, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, that board certification is an assurance of quality. They charge high fees to “candidates” for taking the computer-based test and have developed a system called maintenance of certification (MOC) that is onerous, expensive, and serves as an annuity that forces doctors to pay annually to keep their board certification.

Medicine is a science. In the practice of our discipline, we are expected to follow the science and to adhere to scientific principles. Yet there is neither scientific proof nor good evidence that board certification means anything in terms of competence, safety to the public, or quality of care. Doctors favor life-long learning, and continuing education has long been the standard and should remain so, not board certification or MOC. The mandatory continuing education required in every state to maintain a medical license is sufficient to prove doctors are current in their field of practice and to protect the public.

It is time for the medical community to admit that the emperor wears no clothes, and demand that the money grab of the ABMS and its affiliates be halted. This would result in greater access to care for patients and would reduce the cost of medical care, as the hundreds of millions being “stolen” from doctors today—costs that get passed on to patients—could be recouped and used for treating patients who clearly are in need and are being forgotten as the medical-industrial complex continues to flex its muscles and ensnare more of our national budget in its tentacles.

Neil S. Kaye, MD, DLFAPA

Hockessin, Delaware

1. The World Bank. Current health expenditure (% of GDP). Accessed July 12, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS

2. American Board of Medical Specialties. 2019 Form 990. Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax. Accessed July 12, 2021. https://www.abms.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2019-american-board-of-medical-specialties-form-990.pdf

3. ProPublica. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Accessed July 13, 2021. https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/410654864

While today “The Big Lie” mainly refers to the actions of the prior President, an older and bigger lie that has a real effect on every American is one perpetrated by our very own health care conglomerate. Americans pay the highest rates for health care on the planet; health care consumes about 17% of our gross domestic product.1 If we got higher-quality care, faster services, longer lives, or even greater consumer happiness, paying those rates might be worth it. But we don’t.

Worse yet is the idea that “board certification” assures the public that the doctor from whom they receive/purchase care is of a higher quality than one who is not so credentialed. That is our “Big Lie!” For decades, the public has been told that they should seek out board-certified doctors. Doctors in training have been told they must get board-certified. Hospitals brag about employing only board-certified doctors, insurers sometimes mandate board certification for a doctor to get paid, and employers use board certification as a benchmark for hiring and as a factor in compensation.

The sacred secret is that board certification makes no difference. There is no substantial evidence in any branch of medicine that doctors who are board-certified are better. There is no evidence that board-certified doctors get their patients healthier with more frequency, faster, less expensively, or with fewer medical errors than other doctors. The reality is that board certification is a sham. It’s a certificate granted after taking a very expensive test, and it is now part of an industry that is misleading the public and harming the trust the medical profession had once earned. Board certification is the equivalent of a diploma mill or an online certificate in any other field.

Why has this been kept under wraps for so long? Follow the money. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) oversees 24 specialty boards and reported revenue of $22.2M and expenses of $19.3M on its 2019 IRS Form 990.2 They make profit every year. But, looking further, these “not-for-profit” educational entities are sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars in their “foundations.” Take the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, for instance. They had more than $140M in assets in 2019.3 How is this possible? Easy. They have misled the American public and been remarkably successful convincing other organizations, such as the Joint Commission, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, that board certification is an assurance of quality. They charge high fees to “candidates” for taking the computer-based test and have developed a system called maintenance of certification (MOC) that is onerous, expensive, and serves as an annuity that forces doctors to pay annually to keep their board certification.