User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Weight loss with semaglutide maintained for up to 3 years

Once weekly glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) semaglutide (Ozempic, Novo Nordisk) significantly improved hemoglobin A1c level and body weight for up to 3 years in a large cohort of adults with type 2 diabetes, show real-world data from Israel.

and, in particular, in those patients with higher adherence to the therapy.

Avraham Karasik, MD, from the Institute of Research and Innovation at Maccabi Health Services, Tel Aviv, led the study and presented the work as a poster at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“We found a clinically relevant improvement in blood sugar control and weight loss after 6 months of treatment, comparable with that seen in randomized trials,” said Dr. Karasik during an interview. “Importantly, these effects were sustained for up to 3 years, supporting the use of once weekly semaglutide for the long-term management of type 2 diabetes.”

Esther Walden, RN, deputy head of care at Diabetes UK, appreciated that the real-world findings reflected those seen in the randomized controlled trials. “This study suggests that improvements in blood sugars and weight loss can potentially be sustained in the longer term for adults with type 2 diabetes taking semaglutide as prescribed.”

Large scale, long term, and real world

Dr. Karasik explained that in Israel, there are many early adopters of once weekly semaglutide, and as such, it made for a large sample size, with a significant use duration for the retrospective study. “It’s a popular drug and there are lots of questions about durability of effect,” he pointed out.

Though evidence from randomized controlled trials support the effectiveness of once weekly semaglutide to treat type 2 diabetes, these studies are mostly of relatively short follow-up, explained Dr. Karasik, pointing out that long-term, large-scale, real-world data are needed. “In real life, people are acting differently to the trial setting and some adhere while others don’t, so it was interesting to see the durability as well as what happens when people discontinue treatment or adhere less.”

“Unsurprisingly, people who had a higher proportion of days covered ([PDC]; the total days of semaglutide use as a proportion of the total number of days followed up) had a higher effect,” explained Dr. Karasik, adding that, “if you don’t take it, it doesn’t work.”

A total of 23,442 patients were included in the study, with 6,049 followed up for 2 years or more. Mean baseline A1c was 7.6%-7.9%; body mass index (BMI) was 33.7-33.8 kg/m2; metformin was taken by 84%-88% of participants; insulin was taken by 30%; and 31% were treated with another GLP-1 RA prior to receiving semaglutide.

For study inclusion, participants were required to have had redeemed at least one prescription for subcutaneous semaglutide (0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg), and had at least one A1c measurement 12 months before and around 6 months after the start of semaglutide.

The primary outcome was change in A1c from baseline to the end of the follow-up at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months. Key secondary outcomes included change in body weight from baseline to the end of the follow-up (36 months); change in A1c and body weight in subgroups of patients who were persistently on therapy (at 12, 24, 36 months); and change in A1c and body weight in subgroups stratified by baseline characteristics. There was also an exploratory outcome, which was change in A1c and weight after treatment discontinuation. Dr. Karasik presented some of these results in his poster.

Median follow-up was 17.6 months in the total population and was 29.9 months in those who persisted with therapy for 2 years or more. “We have over 23,000 participants so it’s a large group, and these are not selected patients so the generalizability is better.”

Three-year sustained effect

Results from the total population showed that A1c lowered by a mean of 0.77% (from 7.6% to 6.8%) and body weight reduced by 4.7 kg (from 94.1 kg to 89.7 kg) after 6 months of treatment. These reductions were maintained during 3 years of follow-up in around 1,000 patients.

A significant 75% of participants adhered to once weekly semaglutide (PDC of more than 60%) within the first 6 months. In patients who used semaglutide for at least 2 years, those with high adherence (PDC of at least 80%) showed an A1c reduction of 0.76% after 24 months and of 0.43% after 36 months. Body weight was reduced by 6.0 kg after 24 months and 5.8 kg after 36 months.

Reductions in both A1c and weight were lower in patients with PDC of below 60%, compared with those with PDC of 60%-79% or 80% or over (statistically significant difference of P < .05 for between-groups differences for both outcomes across maximum follow-up time).

As expected, among patients who were GLP-1 RA–naive, reductions in A1c level and body weight were more pronounced, compared with GLP-1 RA–experienced patients (A1c reduction, –0.87% vs. –0.54%; weight loss, –5.5 kg vs. –3.0 kg, respectively; P < .001 for between-groups difference for both outcomes).

Dr. Karasik reported that some patients who stopped taking semaglutide did not regain weight immediately and that this potential residual effect after treatment discontinuation merits additional investigation. “This is not like in the randomized controlled trials. I don’t know how to interpret it, but that’s the observation. A1c did increase a little when they stopped therapy, compared to those with PDC [of 60%-79% or 80% or over] (P < .05 for between-groups difference for both outcomes in most follow-up time).”

He also highlighted that in regard to the long-term outcomes, “unlike many drugs where the effect fades out with time, here we don’t see that happening. This is another encouraging point.”

Dr. Karasik declares speaker fees and grants from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. The study was supported by Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Once weekly glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) semaglutide (Ozempic, Novo Nordisk) significantly improved hemoglobin A1c level and body weight for up to 3 years in a large cohort of adults with type 2 diabetes, show real-world data from Israel.

and, in particular, in those patients with higher adherence to the therapy.

Avraham Karasik, MD, from the Institute of Research and Innovation at Maccabi Health Services, Tel Aviv, led the study and presented the work as a poster at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“We found a clinically relevant improvement in blood sugar control and weight loss after 6 months of treatment, comparable with that seen in randomized trials,” said Dr. Karasik during an interview. “Importantly, these effects were sustained for up to 3 years, supporting the use of once weekly semaglutide for the long-term management of type 2 diabetes.”

Esther Walden, RN, deputy head of care at Diabetes UK, appreciated that the real-world findings reflected those seen in the randomized controlled trials. “This study suggests that improvements in blood sugars and weight loss can potentially be sustained in the longer term for adults with type 2 diabetes taking semaglutide as prescribed.”

Large scale, long term, and real world

Dr. Karasik explained that in Israel, there are many early adopters of once weekly semaglutide, and as such, it made for a large sample size, with a significant use duration for the retrospective study. “It’s a popular drug and there are lots of questions about durability of effect,” he pointed out.

Though evidence from randomized controlled trials support the effectiveness of once weekly semaglutide to treat type 2 diabetes, these studies are mostly of relatively short follow-up, explained Dr. Karasik, pointing out that long-term, large-scale, real-world data are needed. “In real life, people are acting differently to the trial setting and some adhere while others don’t, so it was interesting to see the durability as well as what happens when people discontinue treatment or adhere less.”

“Unsurprisingly, people who had a higher proportion of days covered ([PDC]; the total days of semaglutide use as a proportion of the total number of days followed up) had a higher effect,” explained Dr. Karasik, adding that, “if you don’t take it, it doesn’t work.”

A total of 23,442 patients were included in the study, with 6,049 followed up for 2 years or more. Mean baseline A1c was 7.6%-7.9%; body mass index (BMI) was 33.7-33.8 kg/m2; metformin was taken by 84%-88% of participants; insulin was taken by 30%; and 31% were treated with another GLP-1 RA prior to receiving semaglutide.

For study inclusion, participants were required to have had redeemed at least one prescription for subcutaneous semaglutide (0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg), and had at least one A1c measurement 12 months before and around 6 months after the start of semaglutide.

The primary outcome was change in A1c from baseline to the end of the follow-up at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months. Key secondary outcomes included change in body weight from baseline to the end of the follow-up (36 months); change in A1c and body weight in subgroups of patients who were persistently on therapy (at 12, 24, 36 months); and change in A1c and body weight in subgroups stratified by baseline characteristics. There was also an exploratory outcome, which was change in A1c and weight after treatment discontinuation. Dr. Karasik presented some of these results in his poster.

Median follow-up was 17.6 months in the total population and was 29.9 months in those who persisted with therapy for 2 years or more. “We have over 23,000 participants so it’s a large group, and these are not selected patients so the generalizability is better.”

Three-year sustained effect

Results from the total population showed that A1c lowered by a mean of 0.77% (from 7.6% to 6.8%) and body weight reduced by 4.7 kg (from 94.1 kg to 89.7 kg) after 6 months of treatment. These reductions were maintained during 3 years of follow-up in around 1,000 patients.

A significant 75% of participants adhered to once weekly semaglutide (PDC of more than 60%) within the first 6 months. In patients who used semaglutide for at least 2 years, those with high adherence (PDC of at least 80%) showed an A1c reduction of 0.76% after 24 months and of 0.43% after 36 months. Body weight was reduced by 6.0 kg after 24 months and 5.8 kg after 36 months.

Reductions in both A1c and weight were lower in patients with PDC of below 60%, compared with those with PDC of 60%-79% or 80% or over (statistically significant difference of P < .05 for between-groups differences for both outcomes across maximum follow-up time).

As expected, among patients who were GLP-1 RA–naive, reductions in A1c level and body weight were more pronounced, compared with GLP-1 RA–experienced patients (A1c reduction, –0.87% vs. –0.54%; weight loss, –5.5 kg vs. –3.0 kg, respectively; P < .001 for between-groups difference for both outcomes).

Dr. Karasik reported that some patients who stopped taking semaglutide did not regain weight immediately and that this potential residual effect after treatment discontinuation merits additional investigation. “This is not like in the randomized controlled trials. I don’t know how to interpret it, but that’s the observation. A1c did increase a little when they stopped therapy, compared to those with PDC [of 60%-79% or 80% or over] (P < .05 for between-groups difference for both outcomes in most follow-up time).”

He also highlighted that in regard to the long-term outcomes, “unlike many drugs where the effect fades out with time, here we don’t see that happening. This is another encouraging point.”

Dr. Karasik declares speaker fees and grants from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. The study was supported by Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Once weekly glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) semaglutide (Ozempic, Novo Nordisk) significantly improved hemoglobin A1c level and body weight for up to 3 years in a large cohort of adults with type 2 diabetes, show real-world data from Israel.

and, in particular, in those patients with higher adherence to the therapy.

Avraham Karasik, MD, from the Institute of Research and Innovation at Maccabi Health Services, Tel Aviv, led the study and presented the work as a poster at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

“We found a clinically relevant improvement in blood sugar control and weight loss after 6 months of treatment, comparable with that seen in randomized trials,” said Dr. Karasik during an interview. “Importantly, these effects were sustained for up to 3 years, supporting the use of once weekly semaglutide for the long-term management of type 2 diabetes.”

Esther Walden, RN, deputy head of care at Diabetes UK, appreciated that the real-world findings reflected those seen in the randomized controlled trials. “This study suggests that improvements in blood sugars and weight loss can potentially be sustained in the longer term for adults with type 2 diabetes taking semaglutide as prescribed.”

Large scale, long term, and real world

Dr. Karasik explained that in Israel, there are many early adopters of once weekly semaglutide, and as such, it made for a large sample size, with a significant use duration for the retrospective study. “It’s a popular drug and there are lots of questions about durability of effect,” he pointed out.

Though evidence from randomized controlled trials support the effectiveness of once weekly semaglutide to treat type 2 diabetes, these studies are mostly of relatively short follow-up, explained Dr. Karasik, pointing out that long-term, large-scale, real-world data are needed. “In real life, people are acting differently to the trial setting and some adhere while others don’t, so it was interesting to see the durability as well as what happens when people discontinue treatment or adhere less.”

“Unsurprisingly, people who had a higher proportion of days covered ([PDC]; the total days of semaglutide use as a proportion of the total number of days followed up) had a higher effect,” explained Dr. Karasik, adding that, “if you don’t take it, it doesn’t work.”

A total of 23,442 patients were included in the study, with 6,049 followed up for 2 years or more. Mean baseline A1c was 7.6%-7.9%; body mass index (BMI) was 33.7-33.8 kg/m2; metformin was taken by 84%-88% of participants; insulin was taken by 30%; and 31% were treated with another GLP-1 RA prior to receiving semaglutide.

For study inclusion, participants were required to have had redeemed at least one prescription for subcutaneous semaglutide (0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg), and had at least one A1c measurement 12 months before and around 6 months after the start of semaglutide.

The primary outcome was change in A1c from baseline to the end of the follow-up at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months. Key secondary outcomes included change in body weight from baseline to the end of the follow-up (36 months); change in A1c and body weight in subgroups of patients who were persistently on therapy (at 12, 24, 36 months); and change in A1c and body weight in subgroups stratified by baseline characteristics. There was also an exploratory outcome, which was change in A1c and weight after treatment discontinuation. Dr. Karasik presented some of these results in his poster.

Median follow-up was 17.6 months in the total population and was 29.9 months in those who persisted with therapy for 2 years or more. “We have over 23,000 participants so it’s a large group, and these are not selected patients so the generalizability is better.”

Three-year sustained effect

Results from the total population showed that A1c lowered by a mean of 0.77% (from 7.6% to 6.8%) and body weight reduced by 4.7 kg (from 94.1 kg to 89.7 kg) after 6 months of treatment. These reductions were maintained during 3 years of follow-up in around 1,000 patients.

A significant 75% of participants adhered to once weekly semaglutide (PDC of more than 60%) within the first 6 months. In patients who used semaglutide for at least 2 years, those with high adherence (PDC of at least 80%) showed an A1c reduction of 0.76% after 24 months and of 0.43% after 36 months. Body weight was reduced by 6.0 kg after 24 months and 5.8 kg after 36 months.

Reductions in both A1c and weight were lower in patients with PDC of below 60%, compared with those with PDC of 60%-79% or 80% or over (statistically significant difference of P < .05 for between-groups differences for both outcomes across maximum follow-up time).

As expected, among patients who were GLP-1 RA–naive, reductions in A1c level and body weight were more pronounced, compared with GLP-1 RA–experienced patients (A1c reduction, –0.87% vs. –0.54%; weight loss, –5.5 kg vs. –3.0 kg, respectively; P < .001 for between-groups difference for both outcomes).

Dr. Karasik reported that some patients who stopped taking semaglutide did not regain weight immediately and that this potential residual effect after treatment discontinuation merits additional investigation. “This is not like in the randomized controlled trials. I don’t know how to interpret it, but that’s the observation. A1c did increase a little when they stopped therapy, compared to those with PDC [of 60%-79% or 80% or over] (P < .05 for between-groups difference for both outcomes in most follow-up time).”

He also highlighted that in regard to the long-term outcomes, “unlike many drugs where the effect fades out with time, here we don’t see that happening. This is another encouraging point.”

Dr. Karasik declares speaker fees and grants from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca. The study was supported by Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2023

Tirzepatide with insulin glargine improves type 2 diabetes

HAMBURG, GERMANY – Once-weekly tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Lilly) added to insulin glargine resulted in greater reductions in hemoglobin A1c along with more weight loss and less hypoglycemia, compared with prandial insulin lispro (Humalog, Sanofi), for patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes, show data from the SURPASS-6 randomized clinical trial.

It also resulted in a higher percentage of participants meeting an A1c target of less than 7.0%, wrote the researchers, whose study was presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and was published simultaneously in JAMA.

Also, daily insulin glargine use was substantially lower among participants who received tirzepatide, compared with insulin lispro. Insulin glargine was administered at a dosage 13 IU/day; insulin lispro was administered at a dosage of 62 IU/day. “At the highest dose, some patients stopped their insulin [glargine] in the tirzepatide arm,” said Juan Pablo Frias, MD, medical director and principal investigator of Velocity Clinical Research, Los Angeles, who presented the findings. “We demonstrated clinically meaningful and superior glycemic and body weight control with tirzepatide compared with insulin lispro, while tirzepatide was also associated with less clinically significant hypoglycemia.”

Weight improved for participants who received tirzepatide compared with those who received insulin lispro, at –10 kg and +4 kg respectively. The rate of clinically significant hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 54 mg/dL) or severe hypoglycemia was tenfold lower with tirzepatide, compared with insulin lispro.

The session dedicated to tirzepatide was comoderated by Apostolos Tsapas, MD, professor of medicine and diabetes, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece, and Konstantinos Toulis, MD, consultant in endocrinology and diabetes, General Military Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece. Dr. Toulis remarked that, in the chronic disease setting, management and treatment intensification are challenging to integrate, and there are barriers to adoption in routine practice. “This is particularly true when it adds complexity, as in the case of multiple prandial insulin injections on top of basal insulin in suboptimally treated individuals with type 2 diabetes.

“Demonstrating superiority over insulin lispro in terms of the so-called trio of A1c, weight loss, and hypoglycemic events, tirzepatide offers both a simpler to adhere to and a more efficacious treatment intensification option.” He noted that, while long-term safety data are awaited, “this seems to be a definite step forward from any viewpoint, with the possible exception of the taxpayer’s perspective.”

Dr. Tsapas added: “These data further support the very high dual glucose and weight efficacy of tirzepatide and the primary role of incretin-related therapies amongst the injectables for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.”

Tirzepatide 5, 10, 15 mg vs. insulin lispro in addition to insulin glargine

The researchers aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of adding once-weekly tirzepatide, compared with thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro, as an adjunctive therapy to insulin glargine for patients with type 2 diabetes that was inadequately controlled with basal insulin.

Tirzepatide activates the body’s receptors for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1). The study authors noted that “recent guidelines support adding an injectable incretin-related therapy such as GLP-1 receptor agonist for glycemic control, rather than basal insulin, when oral medications are inadequate.”

The open-label, phase 3b clinical trial drew data from 135 sites across 15 countries and included 1,428 adults with type 2 diabetes who were taking basal insulin. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:3 ratio to receive once-weekly subcutaneous injections of tirzepatide (5 mg [n = 243], 10 mg [n = 238], or 15 mg [n = 236]) or prandial thrice-daily insulin lispro (n = 708).

Both arms were well matched. The average age was 60 years, and 60% of participants were women. The average amount of time patients had type 2 diabetes was 14 years; 85% of participants continued taking metformin. The average A1c level was 8.8% at baseline. Patients were categorized as having obesity (average body mass index, 33 kg/m2). The average insulin glargine dose was 46 units, or 0.5 units/kg.

Outcomes included noninferiority of tirzepatide (pooled cohort) compared with insulin lispro, both in addition to insulin glargine; and A1c change from baseline to week 52 (noninferiority margin, 0.3%). Key secondary endpoints included change in body weight and percentage of participants who achieved an A1c target of less than 7.0%.

About 90% of participants who received the study drug completed the study, said Dr. Frias. “Only 0.5% of tirzepatide patients needed rescue therapy, while only 2% of the insulin lispro did.”

Prior to optimization, the average insulin glargine dose was 42 IU/kg; during optimization, it rose to an average of 46 IU/kg. “At 52 weeks, those on basal-bolus insulin found their insulin glargine dose stayed flat while insulin lispro was 62 units,” reported Dr. Frias. “The three tirzepatide doses show a reduction in insulin glargine, such that the pooled dose reached an average of 11 units, while 20% actually came off their basal insulin altogether [pooled tirzepatide].”

Tirzepatide (pooled) led to the recommended A1c target of less than 7.0% for 68% of patients versus 36% of patients in the insulin lispro group.

About 68% of the patients who received tirzepatide (pooled) achieved the recommended A1c target of less than 7.0% versus 36% of patients in the insulin lispro group.

“Individual tirzepatide doses and pooled doses showed significant reduction in A1c and up to a 2.5% reduction,” Dr. Frias added. “Normoglycemia was obtained by a greater proportion of patients on tirzepatide doses versus basal-bolus insulin – one-third in the 15-mg tirzepatide dose.”

Body weight reduction of 10% or more with tirzepatide

Further, at week 52, weight loss of 5% or more was achieved by 75.4% of participants in the pooled tirzepatide group, compared with 6.3% in the prandial lispro group. The weight loss was accompanied by clinically relevant improvements in cardiometabolic parameters.

In an exploratory analysis, weight loss of 10% or more was achieved by a mean of 48.9% of pooled tirzepatide-treated participants at week 52, compared with 2% of those taking insulin lispro, said Dr. Frias.

“It is possible that the body weight loss induced by tirzepatide therapy and its reported effect in reducing liver fat content may have led to an improvement in insulin sensitivity and decreased insulin requirements,” wrote the researchers in their article.

Hypoglycemia risk and the weight gain observed with complex insulin regimens that include prandial insulin have been main limitations to optimally up-titrate insulin therapy in clinical practice, wrote the authors.

Dr. Frias noted that, in this study, 48% of patients who received insulin lispro experienced clinically significant hypoglycemia, while only 10% of patients in the tirzepatide arms did. “This was 0.4 episodes per patient-year versus 4.4 in tirzepatide and insulin lispro respectively.”

There were more reports of adverse events among the tirzepatide groups than the insulin lispro group. “Typically, with tirzepatide, the commonest adverse events were GI in origin and were mild to moderate.” Rates were 14%-26% for nausea, 11%-15% for diarrhea, and 5%-13% for vomiting.

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Frias has received grants from Eli Lilly paid to his institution during the conduct of the study and grants, personal fees, or nonfinancial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Merck, Altimmune, 89BIO, Akero, Carmot Therapeutics, Intercept, Janssen, Madrigal, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work. Dr. Toulis and Dr. Tsapas declared no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HAMBURG, GERMANY – Once-weekly tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Lilly) added to insulin glargine resulted in greater reductions in hemoglobin A1c along with more weight loss and less hypoglycemia, compared with prandial insulin lispro (Humalog, Sanofi), for patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes, show data from the SURPASS-6 randomized clinical trial.

It also resulted in a higher percentage of participants meeting an A1c target of less than 7.0%, wrote the researchers, whose study was presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and was published simultaneously in JAMA.

Also, daily insulin glargine use was substantially lower among participants who received tirzepatide, compared with insulin lispro. Insulin glargine was administered at a dosage 13 IU/day; insulin lispro was administered at a dosage of 62 IU/day. “At the highest dose, some patients stopped their insulin [glargine] in the tirzepatide arm,” said Juan Pablo Frias, MD, medical director and principal investigator of Velocity Clinical Research, Los Angeles, who presented the findings. “We demonstrated clinically meaningful and superior glycemic and body weight control with tirzepatide compared with insulin lispro, while tirzepatide was also associated with less clinically significant hypoglycemia.”

Weight improved for participants who received tirzepatide compared with those who received insulin lispro, at –10 kg and +4 kg respectively. The rate of clinically significant hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 54 mg/dL) or severe hypoglycemia was tenfold lower with tirzepatide, compared with insulin lispro.

The session dedicated to tirzepatide was comoderated by Apostolos Tsapas, MD, professor of medicine and diabetes, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece, and Konstantinos Toulis, MD, consultant in endocrinology and diabetes, General Military Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece. Dr. Toulis remarked that, in the chronic disease setting, management and treatment intensification are challenging to integrate, and there are barriers to adoption in routine practice. “This is particularly true when it adds complexity, as in the case of multiple prandial insulin injections on top of basal insulin in suboptimally treated individuals with type 2 diabetes.

“Demonstrating superiority over insulin lispro in terms of the so-called trio of A1c, weight loss, and hypoglycemic events, tirzepatide offers both a simpler to adhere to and a more efficacious treatment intensification option.” He noted that, while long-term safety data are awaited, “this seems to be a definite step forward from any viewpoint, with the possible exception of the taxpayer’s perspective.”

Dr. Tsapas added: “These data further support the very high dual glucose and weight efficacy of tirzepatide and the primary role of incretin-related therapies amongst the injectables for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.”

Tirzepatide 5, 10, 15 mg vs. insulin lispro in addition to insulin glargine

The researchers aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of adding once-weekly tirzepatide, compared with thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro, as an adjunctive therapy to insulin glargine for patients with type 2 diabetes that was inadequately controlled with basal insulin.

Tirzepatide activates the body’s receptors for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1). The study authors noted that “recent guidelines support adding an injectable incretin-related therapy such as GLP-1 receptor agonist for glycemic control, rather than basal insulin, when oral medications are inadequate.”

The open-label, phase 3b clinical trial drew data from 135 sites across 15 countries and included 1,428 adults with type 2 diabetes who were taking basal insulin. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:3 ratio to receive once-weekly subcutaneous injections of tirzepatide (5 mg [n = 243], 10 mg [n = 238], or 15 mg [n = 236]) or prandial thrice-daily insulin lispro (n = 708).

Both arms were well matched. The average age was 60 years, and 60% of participants were women. The average amount of time patients had type 2 diabetes was 14 years; 85% of participants continued taking metformin. The average A1c level was 8.8% at baseline. Patients were categorized as having obesity (average body mass index, 33 kg/m2). The average insulin glargine dose was 46 units, or 0.5 units/kg.

Outcomes included noninferiority of tirzepatide (pooled cohort) compared with insulin lispro, both in addition to insulin glargine; and A1c change from baseline to week 52 (noninferiority margin, 0.3%). Key secondary endpoints included change in body weight and percentage of participants who achieved an A1c target of less than 7.0%.

About 90% of participants who received the study drug completed the study, said Dr. Frias. “Only 0.5% of tirzepatide patients needed rescue therapy, while only 2% of the insulin lispro did.”

Prior to optimization, the average insulin glargine dose was 42 IU/kg; during optimization, it rose to an average of 46 IU/kg. “At 52 weeks, those on basal-bolus insulin found their insulin glargine dose stayed flat while insulin lispro was 62 units,” reported Dr. Frias. “The three tirzepatide doses show a reduction in insulin glargine, such that the pooled dose reached an average of 11 units, while 20% actually came off their basal insulin altogether [pooled tirzepatide].”

Tirzepatide (pooled) led to the recommended A1c target of less than 7.0% for 68% of patients versus 36% of patients in the insulin lispro group.

About 68% of the patients who received tirzepatide (pooled) achieved the recommended A1c target of less than 7.0% versus 36% of patients in the insulin lispro group.

“Individual tirzepatide doses and pooled doses showed significant reduction in A1c and up to a 2.5% reduction,” Dr. Frias added. “Normoglycemia was obtained by a greater proportion of patients on tirzepatide doses versus basal-bolus insulin – one-third in the 15-mg tirzepatide dose.”

Body weight reduction of 10% or more with tirzepatide

Further, at week 52, weight loss of 5% or more was achieved by 75.4% of participants in the pooled tirzepatide group, compared with 6.3% in the prandial lispro group. The weight loss was accompanied by clinically relevant improvements in cardiometabolic parameters.

In an exploratory analysis, weight loss of 10% or more was achieved by a mean of 48.9% of pooled tirzepatide-treated participants at week 52, compared with 2% of those taking insulin lispro, said Dr. Frias.

“It is possible that the body weight loss induced by tirzepatide therapy and its reported effect in reducing liver fat content may have led to an improvement in insulin sensitivity and decreased insulin requirements,” wrote the researchers in their article.

Hypoglycemia risk and the weight gain observed with complex insulin regimens that include prandial insulin have been main limitations to optimally up-titrate insulin therapy in clinical practice, wrote the authors.

Dr. Frias noted that, in this study, 48% of patients who received insulin lispro experienced clinically significant hypoglycemia, while only 10% of patients in the tirzepatide arms did. “This was 0.4 episodes per patient-year versus 4.4 in tirzepatide and insulin lispro respectively.”

There were more reports of adverse events among the tirzepatide groups than the insulin lispro group. “Typically, with tirzepatide, the commonest adverse events were GI in origin and were mild to moderate.” Rates were 14%-26% for nausea, 11%-15% for diarrhea, and 5%-13% for vomiting.

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Frias has received grants from Eli Lilly paid to his institution during the conduct of the study and grants, personal fees, or nonfinancial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Merck, Altimmune, 89BIO, Akero, Carmot Therapeutics, Intercept, Janssen, Madrigal, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work. Dr. Toulis and Dr. Tsapas declared no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HAMBURG, GERMANY – Once-weekly tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Lilly) added to insulin glargine resulted in greater reductions in hemoglobin A1c along with more weight loss and less hypoglycemia, compared with prandial insulin lispro (Humalog, Sanofi), for patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes, show data from the SURPASS-6 randomized clinical trial.

It also resulted in a higher percentage of participants meeting an A1c target of less than 7.0%, wrote the researchers, whose study was presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and was published simultaneously in JAMA.

Also, daily insulin glargine use was substantially lower among participants who received tirzepatide, compared with insulin lispro. Insulin glargine was administered at a dosage 13 IU/day; insulin lispro was administered at a dosage of 62 IU/day. “At the highest dose, some patients stopped their insulin [glargine] in the tirzepatide arm,” said Juan Pablo Frias, MD, medical director and principal investigator of Velocity Clinical Research, Los Angeles, who presented the findings. “We demonstrated clinically meaningful and superior glycemic and body weight control with tirzepatide compared with insulin lispro, while tirzepatide was also associated with less clinically significant hypoglycemia.”

Weight improved for participants who received tirzepatide compared with those who received insulin lispro, at –10 kg and +4 kg respectively. The rate of clinically significant hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 54 mg/dL) or severe hypoglycemia was tenfold lower with tirzepatide, compared with insulin lispro.

The session dedicated to tirzepatide was comoderated by Apostolos Tsapas, MD, professor of medicine and diabetes, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece, and Konstantinos Toulis, MD, consultant in endocrinology and diabetes, General Military Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece. Dr. Toulis remarked that, in the chronic disease setting, management and treatment intensification are challenging to integrate, and there are barriers to adoption in routine practice. “This is particularly true when it adds complexity, as in the case of multiple prandial insulin injections on top of basal insulin in suboptimally treated individuals with type 2 diabetes.

“Demonstrating superiority over insulin lispro in terms of the so-called trio of A1c, weight loss, and hypoglycemic events, tirzepatide offers both a simpler to adhere to and a more efficacious treatment intensification option.” He noted that, while long-term safety data are awaited, “this seems to be a definite step forward from any viewpoint, with the possible exception of the taxpayer’s perspective.”

Dr. Tsapas added: “These data further support the very high dual glucose and weight efficacy of tirzepatide and the primary role of incretin-related therapies amongst the injectables for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.”

Tirzepatide 5, 10, 15 mg vs. insulin lispro in addition to insulin glargine

The researchers aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of adding once-weekly tirzepatide, compared with thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro, as an adjunctive therapy to insulin glargine for patients with type 2 diabetes that was inadequately controlled with basal insulin.

Tirzepatide activates the body’s receptors for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1). The study authors noted that “recent guidelines support adding an injectable incretin-related therapy such as GLP-1 receptor agonist for glycemic control, rather than basal insulin, when oral medications are inadequate.”

The open-label, phase 3b clinical trial drew data from 135 sites across 15 countries and included 1,428 adults with type 2 diabetes who were taking basal insulin. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:3 ratio to receive once-weekly subcutaneous injections of tirzepatide (5 mg [n = 243], 10 mg [n = 238], or 15 mg [n = 236]) or prandial thrice-daily insulin lispro (n = 708).

Both arms were well matched. The average age was 60 years, and 60% of participants were women. The average amount of time patients had type 2 diabetes was 14 years; 85% of participants continued taking metformin. The average A1c level was 8.8% at baseline. Patients were categorized as having obesity (average body mass index, 33 kg/m2). The average insulin glargine dose was 46 units, or 0.5 units/kg.

Outcomes included noninferiority of tirzepatide (pooled cohort) compared with insulin lispro, both in addition to insulin glargine; and A1c change from baseline to week 52 (noninferiority margin, 0.3%). Key secondary endpoints included change in body weight and percentage of participants who achieved an A1c target of less than 7.0%.

About 90% of participants who received the study drug completed the study, said Dr. Frias. “Only 0.5% of tirzepatide patients needed rescue therapy, while only 2% of the insulin lispro did.”

Prior to optimization, the average insulin glargine dose was 42 IU/kg; during optimization, it rose to an average of 46 IU/kg. “At 52 weeks, those on basal-bolus insulin found their insulin glargine dose stayed flat while insulin lispro was 62 units,” reported Dr. Frias. “The three tirzepatide doses show a reduction in insulin glargine, such that the pooled dose reached an average of 11 units, while 20% actually came off their basal insulin altogether [pooled tirzepatide].”

Tirzepatide (pooled) led to the recommended A1c target of less than 7.0% for 68% of patients versus 36% of patients in the insulin lispro group.

About 68% of the patients who received tirzepatide (pooled) achieved the recommended A1c target of less than 7.0% versus 36% of patients in the insulin lispro group.

“Individual tirzepatide doses and pooled doses showed significant reduction in A1c and up to a 2.5% reduction,” Dr. Frias added. “Normoglycemia was obtained by a greater proportion of patients on tirzepatide doses versus basal-bolus insulin – one-third in the 15-mg tirzepatide dose.”

Body weight reduction of 10% or more with tirzepatide

Further, at week 52, weight loss of 5% or more was achieved by 75.4% of participants in the pooled tirzepatide group, compared with 6.3% in the prandial lispro group. The weight loss was accompanied by clinically relevant improvements in cardiometabolic parameters.

In an exploratory analysis, weight loss of 10% or more was achieved by a mean of 48.9% of pooled tirzepatide-treated participants at week 52, compared with 2% of those taking insulin lispro, said Dr. Frias.

“It is possible that the body weight loss induced by tirzepatide therapy and its reported effect in reducing liver fat content may have led to an improvement in insulin sensitivity and decreased insulin requirements,” wrote the researchers in their article.

Hypoglycemia risk and the weight gain observed with complex insulin regimens that include prandial insulin have been main limitations to optimally up-titrate insulin therapy in clinical practice, wrote the authors.

Dr. Frias noted that, in this study, 48% of patients who received insulin lispro experienced clinically significant hypoglycemia, while only 10% of patients in the tirzepatide arms did. “This was 0.4 episodes per patient-year versus 4.4 in tirzepatide and insulin lispro respectively.”

There were more reports of adverse events among the tirzepatide groups than the insulin lispro group. “Typically, with tirzepatide, the commonest adverse events were GI in origin and were mild to moderate.” Rates were 14%-26% for nausea, 11%-15% for diarrhea, and 5%-13% for vomiting.

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Frias has received grants from Eli Lilly paid to his institution during the conduct of the study and grants, personal fees, or nonfinancial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Merck, Altimmune, 89BIO, Akero, Carmot Therapeutics, Intercept, Janssen, Madrigal, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work. Dr. Toulis and Dr. Tsapas declared no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EASD 2023

Decoding AFib recurrence: PCPs’ role in personalized care

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three patients who experience their first bout of atrial fibrillation (AFib) during hospitalization can expect to experience a recurrence of the arrhythmia within the year, new research shows.

The findings, reported in Annals of Internal Medicine, suggest these patients may be good candidates for oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk for stroke.

“Atrial fibrillation is very common in patients for the very first time in their life when they’re sick and in the hospital,” said William F. McIntyre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., who led the study. These new insights into AFib management suggest there is a need for primary care physicians to be on the lookout for potential recurrence.

AFib is strongly linked to stroke, and patients at greater risk for stroke may be prescribed oral anticoagulants. Although the arrhythmia can be reversed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, risk for recurrence was unclear, Dr. McIntyre said.

“We wanted to know if the patient was in atrial fibrillation because of the physiologic stress that they were under, or if they just have the disease called atrial fibrillation, which should usually be followed lifelong by a specialist,” Dr. McIntyre said.

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues followed 139 patients (mean age, 71 years) at three medical centers in Ontario who experienced new-onset AFib during their hospital stay, along with an equal number of patients who had no history of AFib and who served as controls. The research team used a Holter monitor to record study participants’ heart rhythm for 14 days to detect incident AFib at 1 and 6 months after discharge. They also followed up with periodic phone calls for up to 12 months. Among the study participants, half were admitted for noncardiac surgeries, and the other half were admitted for medical illnesses, including infections and pneumonia. Participants with a prior history of AFib were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome of the study was an episode of AFib that lasted at least 30 seconds on the monitor or one detected during routine care at the 12-month mark.

Patients who experienced AFib for the first time in the hospital had roughly a 33% risk for recurrence within a year, nearly sevenfold higher than their age- and sex-matched counterparts who had not had an arrhythmia during their hospital stay (3%; confidence interval, 0%-6.4%).

“This study has important implications for management of patients who have a first presentation of AFib that is concurrent with a reversible physiologic stressor,” the authors wrote. “An AFib recurrence risk of 33.1% at 1 year is neither low enough to conclude that transient new-onset AFib in the setting of another illness is benign nor high enough that all such transient new-onset AFib can be assumed to be paroxysmal AFib. Instead, these results call for risk stratification and follow-up in these patients.”

The researchers reported that among people with recurrent AFib in the study, the median total time in arrhythmia was 9 hours. “This far exceeds the cutoff of 6 minutes that was established as being associated with stroke using simulated AFib screening in patients with implanted continuous monitors,” they wrote. “These results suggest that the patients in our study who had AFib detected in follow-up are similar to contemporary patients with AFib for whom evidence-based therapies, including oral anticoagulation, are warranted.”

Dr. McIntyre and colleagues were able to track outcomes and treatments for the patients in the study. In the group with recurrent AFib, 1 had a stroke, 2 experienced systemic embolism, 3 had a heart failure event, 6 experienced bleeding, and 11 died. In the other group, there was one case of stroke, one of heart failure, four cases involving bleeding, and seven deaths. “The proportion of participants with new-onset AFib during their initial hospitalization who were taking oral anticoagulants was 47.1% at 6 months and 49.2% at 12 months. This included 73% of participants with AFib detected during follow-up and 39% who did not have AFib detected during follow-up,” they wrote.

The uncertain nature of AFib recurrence complicates predictions about patients’ posthospitalization experiences within the following year. “We cannot just say: ‘Hey, this is just a reversible illness, and now we can forget about it,’ ” Dr. McIntyre said. “Nor is the risk of recurrence so strong in the other direction that you can give patients a lifelong diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.”

Role for primary care

Without that certainty, physicians cannot refer everyone who experiences new-onset AFib to a cardiologist for long-term care. The variability in recurrence rates necessitates a more nuanced and personalized approach. Here, primary care physicians step in, offering tailored care based on their established, long-term patient relationships, Dr. McIntyre said.

The study participants already have chronic health conditions that bring them into regular contact with their family physician. This gives primary care physicians a golden opportunity to be on lookout and to recommend care from a cardiologist at the appropriate time if it becomes necessary, he said.

“I have certainly seen cases of recurrent atrial fibrillation in patients who had an episode while hospitalized, and consistent with this study, this is a common clinical occurrence,” said Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York. Primary care physicians must remain vigilant and avoid the temptation to attribute AFib solely to illness or surgery

“Ideally, we would have randomized clinical trial data to guide the decision about whether to use prophylactic anticoagulation,” said Dr. Bhatt, who added that a cardiology consultation may also be appropriate.

Dr. McIntyre reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous relationships with industry.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Spironolactone safe, effective option for women with hidradenitis suppurativa

CARLSBAD, CALIF. –

Those are the key findings from a single-center retrospective study that Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, and colleagues presented during a poster session at the annual symposium of the California Society of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery.

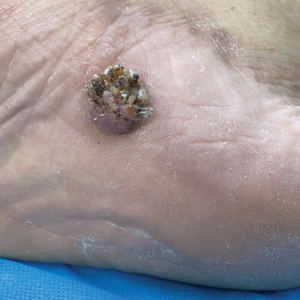

In an interview after the meeting, Dr. Hsiao, a dermatologist who directs the hidradenitis suppurativa clinic at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that hormones are thought to play a role in HS pathogenesis given the typical HS symptom onset around puberty and fluctuations in disease activity with menses (typically premenstrual flares) and pregnancy. “Spironolactone, an anti-androgenic agent, is used to treat HS in women; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of spironolactone for HS and whether certain patient characteristics may influence treatment response,” she told this news organization. “This study is unique in that we contribute to existing literature regarding spironolactone efficacy in HS and we also investigate whether the presence of menstrual HS flares or polycystic ovarian syndrome influences the likelihood of response to spironolactone.”

For the analysis, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 53 adult women with HS who were prescribed spironolactone and who received care at USC’s HS clinic between January 2015 and December 2021. They collected data on demographics, comorbidities, HS medications, treatment response at 3 and 6 months, as well as adverse events. They also evaluated physician-assessed response to treatment when available.

The mean age of patients was 31 years, 37% were White, 30.4% were Black, 21.7% were Hispanic, 6.5% were Asian, and the remainder were biracial. The mean age at HS diagnosis was 25.1 years and the three most common comorbidities were acne (50.9%), obesity (45.3%), and anemia (37.7%). As for menstrual history, 56.6% had perimenstrual HS flares and 37.7% had irregular menstrual cycles. The top three classes of concomitant medications were antibiotics (58.5%), oral contraceptives (50.9%), and other birth control methods (18.9%).

The mean spironolactone dose was 104 mg/day; 84.1% of the women experienced improvement of HS 3 months after starting the drug, while 81.8% had improvement of their HS 6 months after starting the drug. The researchers also found that 56.6% of women had documented perimenstrual HS flares and 7.5% had PCOS.

“Spironolactone is often thought of as a helpful medication to consider if a patient reports having HS flares around menses or features of PCOS,” Dr. Hsiao said. However, she added, “our study found that there was no statistically significant difference in the response to spironolactone based on the presence of premenstrual flares or concomitant PCOS.” She said that spironolactone may be used as an adjunct therapeutic option in patients with more severe disease in addition to other medical and surgical therapies for HS. “Combining different treatment options that target different pathophysiologic factors is usually required to achieve adequate disease control in HS,” she said.

Dr. Hsiao acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and small sample size. “A confounding variable is that some patients were on other medications in addition to spironolactone, which may have influenced treatment outcomes,” she noted. “Larger prospective studies are needed to identify optimal dosing for spironolactone therapy in HS as well as predictors of treatment response.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that with only one FDA-approved systemic medication for the management of HS (adalimumab), “we off-label bandits must be creative to curtail the incredibly painful impact this chronic, destructive inflammatory disease can have on our patients.”

“The evidence supporting our approaches, whether it be antibiotics, immunomodulators, or in this case, antihormonal therapies, is limited, so more data is always welcome,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved with the study. “One very interesting point raised by the authors, one I share with my trainees frequently from my own experience, is that regardless of menstrual cycle abnormalities, spironolactone can be impactful. This is important to remember, in that overt signs of hormonal influences is not a requisite for the use or effectiveness of antihormonal therapy.”

Dr. Hsiao disclosed that she is a member of board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. She has also served as a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, UCB, as a speaker for AbbVie, and as an investigator for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Incyte. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CARLSBAD, CALIF. –

Those are the key findings from a single-center retrospective study that Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, and colleagues presented during a poster session at the annual symposium of the California Society of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery.

In an interview after the meeting, Dr. Hsiao, a dermatologist who directs the hidradenitis suppurativa clinic at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that hormones are thought to play a role in HS pathogenesis given the typical HS symptom onset around puberty and fluctuations in disease activity with menses (typically premenstrual flares) and pregnancy. “Spironolactone, an anti-androgenic agent, is used to treat HS in women; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of spironolactone for HS and whether certain patient characteristics may influence treatment response,” she told this news organization. “This study is unique in that we contribute to existing literature regarding spironolactone efficacy in HS and we also investigate whether the presence of menstrual HS flares or polycystic ovarian syndrome influences the likelihood of response to spironolactone.”

For the analysis, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 53 adult women with HS who were prescribed spironolactone and who received care at USC’s HS clinic between January 2015 and December 2021. They collected data on demographics, comorbidities, HS medications, treatment response at 3 and 6 months, as well as adverse events. They also evaluated physician-assessed response to treatment when available.

The mean age of patients was 31 years, 37% were White, 30.4% were Black, 21.7% were Hispanic, 6.5% were Asian, and the remainder were biracial. The mean age at HS diagnosis was 25.1 years and the three most common comorbidities were acne (50.9%), obesity (45.3%), and anemia (37.7%). As for menstrual history, 56.6% had perimenstrual HS flares and 37.7% had irregular menstrual cycles. The top three classes of concomitant medications were antibiotics (58.5%), oral contraceptives (50.9%), and other birth control methods (18.9%).

The mean spironolactone dose was 104 mg/day; 84.1% of the women experienced improvement of HS 3 months after starting the drug, while 81.8% had improvement of their HS 6 months after starting the drug. The researchers also found that 56.6% of women had documented perimenstrual HS flares and 7.5% had PCOS.

“Spironolactone is often thought of as a helpful medication to consider if a patient reports having HS flares around menses or features of PCOS,” Dr. Hsiao said. However, she added, “our study found that there was no statistically significant difference in the response to spironolactone based on the presence of premenstrual flares or concomitant PCOS.” She said that spironolactone may be used as an adjunct therapeutic option in patients with more severe disease in addition to other medical and surgical therapies for HS. “Combining different treatment options that target different pathophysiologic factors is usually required to achieve adequate disease control in HS,” she said.

Dr. Hsiao acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and small sample size. “A confounding variable is that some patients were on other medications in addition to spironolactone, which may have influenced treatment outcomes,” she noted. “Larger prospective studies are needed to identify optimal dosing for spironolactone therapy in HS as well as predictors of treatment response.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that with only one FDA-approved systemic medication for the management of HS (adalimumab), “we off-label bandits must be creative to curtail the incredibly painful impact this chronic, destructive inflammatory disease can have on our patients.”

“The evidence supporting our approaches, whether it be antibiotics, immunomodulators, or in this case, antihormonal therapies, is limited, so more data is always welcome,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved with the study. “One very interesting point raised by the authors, one I share with my trainees frequently from my own experience, is that regardless of menstrual cycle abnormalities, spironolactone can be impactful. This is important to remember, in that overt signs of hormonal influences is not a requisite for the use or effectiveness of antihormonal therapy.”

Dr. Hsiao disclosed that she is a member of board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. She has also served as a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, UCB, as a speaker for AbbVie, and as an investigator for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Incyte. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CARLSBAD, CALIF. –

Those are the key findings from a single-center retrospective study that Jennifer L. Hsiao, MD, and colleagues presented during a poster session at the annual symposium of the California Society of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery.

In an interview after the meeting, Dr. Hsiao, a dermatologist who directs the hidradenitis suppurativa clinic at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that hormones are thought to play a role in HS pathogenesis given the typical HS symptom onset around puberty and fluctuations in disease activity with menses (typically premenstrual flares) and pregnancy. “Spironolactone, an anti-androgenic agent, is used to treat HS in women; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of spironolactone for HS and whether certain patient characteristics may influence treatment response,” she told this news organization. “This study is unique in that we contribute to existing literature regarding spironolactone efficacy in HS and we also investigate whether the presence of menstrual HS flares or polycystic ovarian syndrome influences the likelihood of response to spironolactone.”

For the analysis, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 53 adult women with HS who were prescribed spironolactone and who received care at USC’s HS clinic between January 2015 and December 2021. They collected data on demographics, comorbidities, HS medications, treatment response at 3 and 6 months, as well as adverse events. They also evaluated physician-assessed response to treatment when available.

The mean age of patients was 31 years, 37% were White, 30.4% were Black, 21.7% were Hispanic, 6.5% were Asian, and the remainder were biracial. The mean age at HS diagnosis was 25.1 years and the three most common comorbidities were acne (50.9%), obesity (45.3%), and anemia (37.7%). As for menstrual history, 56.6% had perimenstrual HS flares and 37.7% had irregular menstrual cycles. The top three classes of concomitant medications were antibiotics (58.5%), oral contraceptives (50.9%), and other birth control methods (18.9%).

The mean spironolactone dose was 104 mg/day; 84.1% of the women experienced improvement of HS 3 months after starting the drug, while 81.8% had improvement of their HS 6 months after starting the drug. The researchers also found that 56.6% of women had documented perimenstrual HS flares and 7.5% had PCOS.

“Spironolactone is often thought of as a helpful medication to consider if a patient reports having HS flares around menses or features of PCOS,” Dr. Hsiao said. However, she added, “our study found that there was no statistically significant difference in the response to spironolactone based on the presence of premenstrual flares or concomitant PCOS.” She said that spironolactone may be used as an adjunct therapeutic option in patients with more severe disease in addition to other medical and surgical therapies for HS. “Combining different treatment options that target different pathophysiologic factors is usually required to achieve adequate disease control in HS,” she said.

Dr. Hsiao acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center design and small sample size. “A confounding variable is that some patients were on other medications in addition to spironolactone, which may have influenced treatment outcomes,” she noted. “Larger prospective studies are needed to identify optimal dosing for spironolactone therapy in HS as well as predictors of treatment response.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that with only one FDA-approved systemic medication for the management of HS (adalimumab), “we off-label bandits must be creative to curtail the incredibly painful impact this chronic, destructive inflammatory disease can have on our patients.”

“The evidence supporting our approaches, whether it be antibiotics, immunomodulators, or in this case, antihormonal therapies, is limited, so more data is always welcome,” said Dr. Friedman, who was not involved with the study. “One very interesting point raised by the authors, one I share with my trainees frequently from my own experience, is that regardless of menstrual cycle abnormalities, spironolactone can be impactful. This is important to remember, in that overt signs of hormonal influences is not a requisite for the use or effectiveness of antihormonal therapy.”

Dr. Hsiao disclosed that she is a member of board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. She has also served as a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, UCB, as a speaker for AbbVie, and as an investigator for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Incyte. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT CALDERM 2023

Preparing for the viral trifecta: RSV, influenza, and COVID-19

New armamentaria available to fight an old disease.

In July 2023, nirsevimab (Beyfortus), a monoclonal antibody, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease in infants and children younger than 2 years of age. On Aug. 3, 2023, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended routine use of it for all infants younger than 8 months of age born during or entering their first RSV season. Its use is also recommended for certain children 8-19 months of age who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease at the start of their second RSV season. Hearing the approval, I immediately had a flashback to residency, recalling the multiple infants admitted each fall and winter exhibiting classic symptoms including cough, rhinorrhea, nasal flaring, retractions, and wheezing with many having oxygen requirements and others needing intubation. Only supportive care was available.

RSV is the leading cause of infant hospitalizations. Annually, the CDC estimates there are 50,000-80,000 RSV hospitalizations and 100-300 RSV-related deaths in the United States in persons younger than 5 years of age. While premature infants have the highest rates of hospitalization (three times a term infant) about 79% of hospitalized children younger than 2 years have no underlying medical risks.1 The majority of children will experience RSV as an upper respiratory infection within the first 2 years of life. However, severe disease requiring hospitalization is more likely to occur in premature infants and children younger than 6 months; children younger than 2 with congenital heart disease and/or chronic lung disease; children with severe cystic fibrosis; as well as the immunocompromised child and individuals with neuromuscular disorders that preclude clearing mucous secretions or have difficulty swallowing.

Palivizumab (Synagis), the first monoclonal antibody to prevent RSV in infants was licensed in 1998. Its use was limited to infants meeting specific criteria developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Only 5% of infants had access to it. It was a short-acting agent requiring monthly injections, which were very costly ($1,661-$2,584 per dose). Eligible infants could receive up to five injections per season. Several studies proved its use was not cost beneficial.