User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Multivitamins and dementia: Untangling the COSMOS study web

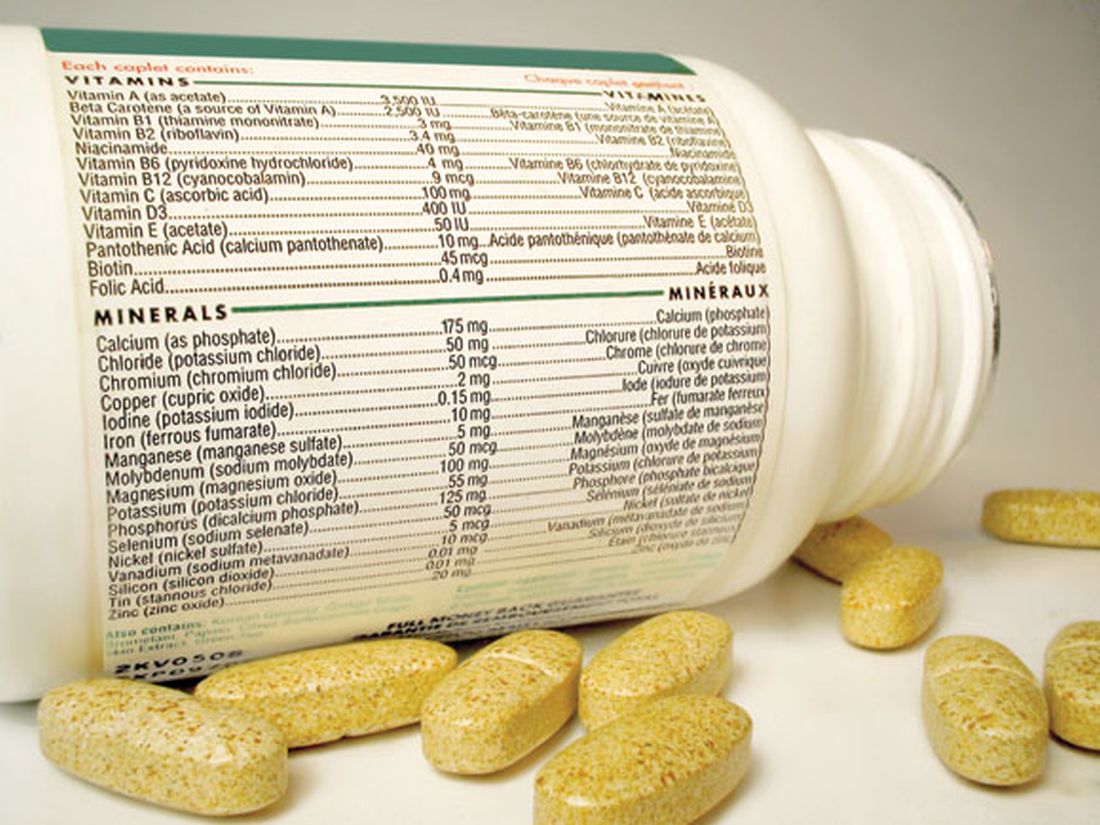

I have written before about the COSMOS study and its finding that multivitamins (and chocolate) did not improve brain or cardiovascular health. So I was surprised to read that a “new” study found that vitamins can forestall dementia and age-related cognitive decline.

Upon closer look, the new data are neither new nor convincing, at least to me.

Chocolate and multivitamins for CVD and cancer prevention

The large randomized COSMOS trial was supposed to be the definitive study on chocolate that would establish its heart-health benefits without a doubt. Or, rather, the benefits of a cocoa bean extract in pill form given to healthy, older volunteers. The COSMOS study was negative. Chocolate, or the cocoa bean extract they used, did not reduce cardiovascular events.

And yet for all the prepublication importance attached to COSMOS, it is scarcely mentioned. Had it been positive, rest assured that Mars, the candy bar company that cofunded the research, and other interested parties would have been shouting it from the rooftops. As it is, they’re already spinning it.

Which brings us to the multivitamin component. COSMOS actually had a 2 × 2 design. In other words, there were four groups in this study: chocolate plus multivitamin, chocolate plus placebo, placebo plus multivitamin, and placebo plus placebo. This type of study design allows you to study two different interventions simultaneously, provided that they are independent and do not interact with each other. In addition to the primary cardiovascular endpoint, they also studied a cancer endpoint.

The multivitamin supplement didn’t reduce cardiovascular events either. Nor did it affect cancer outcomes. The main COSMOS study was negative and reinforced what countless other studies have proven: Taking a daily multivitamin does not reduce your risk of having a heart attack or developing cancer.

But wait, there’s more: COSMOS-Mind

But no researcher worth his salt studies just one or two endpoints in a study. The participants also underwent neurologic and memory testing. These results were reported separately in the COSMOS-Mind study.

COSMOS-Mind is often described as a separate (or “new”) study. In reality, it included the same participants from the original COSMOS trial and measured yet another primary outcome of cognitive performance on a series of tests administered by telephone. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with studying multiple outcomes in your patient population (after all, that salami isn’t going to slice itself), they cannot all be primary outcomes. Some, by necessity, must be secondary hypothesis–generating outcomes. If you test enough endpoints, multiple hypothesis testing dictates that eventually you will get a positive result simply by chance.

There was a time when the neurocognitive outcomes of COSMOS would have been reported in the same paper as the cardiovascular outcomes, but that time seems to have passed us by. Researchers live or die by the number of their publications, and there is an inherent advantage to squeezing as many publications as possible from the same dataset. Though, to be fair, the journal would probably have asked them to split up the paper as well.

In brief, the cocoa extract again fell short in COSMOS-Mind, but the multivitamin arm did better on the composite cognitive outcome. It was a fairly small difference – a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score at the 3-year mark (the z-score is the mean divided by the standard deviation). Much was also made of the fact that the improvement seemed to vary by prior history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Those with a history of CVD had a 0.11-point improvement, whereas those without had a 0.06-point improvement. The authors couldn’t offer a definitive explanation for these findings. Any argument that multivitamins improve cardiovascular health and therefore prevent vascular dementia has to contend with the fact that the main COSMOS study didn’t show a cardiovascular benefit for vitamins. Speculation that you are treating nutritional deficiencies is exactly that: speculation.

A more salient question is: What does a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score mean clinically? This study didn’t assess whether a multivitamin supplement prevented dementia or allowed people to live independently for longer. In fairness, that would have been exceptionally difficult to do and would have required a much longer study.

Their one attempt to quantify the cognitive benefit clinically was a calculation about normal age-related decline. Test scores were 0.045 points lower for every 1-year increase in age among participants (their mean age was 73 years). So the authors contend that a 0.07-point increase, or the 0.083-point increase that they found at year 3, corresponds to 1.8 years of age-related decline forestalled. Whether this is an appropriate assumption, I leave for the reader to decide.

COSMOS-Web and replication

The results of COSMOS-Mind were seemingly bolstered by the recent publication of COSMOS-Web. Although I’ve seen this study described as having replicated the results of COSMOS-Mind, that description is a bit misleading. This was yet another ancillary COSMOS study; more than half of the 2,262 participants in COSMOS-Mind were also included in COSMOS-Web. Replicating results in the same people isn’t true replication.

The main difference between COSMOS-Mind and COSMOS-Web is that the former used a telephone interview to administer the cognitive tests and the latter used the Internet. They also had different endpoints, with COSMOS-Web looking at immediate recall rather than a global test composite.

COSMOS-Web was a positive study in that patients getting the multivitamin supplement did better on the test for immediate memory recall (remembering a list of 20 words), though they didn’t improve on tests of memory retention, executive function, or novel object recognition (basically a test where subjects have to identify matching geometric patterns and then recall them later). They were able to remember an additional 0.71 word on average, compared with 0.44 word in the placebo group. (For the record, it found no benefit for the cocoa extract).

Everybody does better on memory tests the second time around because practice makes perfect, hence the improvement in the placebo group. This benefit at 1 year did not survive to the end of follow-up at 3 years, in contrast to COSMOS-Mind, where the benefit was not apparent at 1 year and seen only at year 3. A history of cardiovascular disease didn’t seem to affect the results in COSMOS-Web as it did in COSMOS-Mind. As far as replications go, COSMOS-Web has some very non-negligible differences, compared with COSMOS-Mind. This incongruity, especially given the overlap in the patient populations is hard to reconcile. If COSMOS-Web was supposed to assuage any doubts that persisted after COSMOS-Mind, it hasn’t for me.

One of these studies is not like the others

Finally, although the COSMOS trial and all its ancillary study analyses suggest a neurocognitive benefit to multivitamin supplementation, it’s not the first study to test the matter. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study looked at vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper. There was no benefit on any of the six cognitive tests administered to patients. The Women’s Health Study, the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study and PREADViSE have all failed to show any benefit to the various vitamins and minerals they studied. A meta-analysis of 11 trials found no benefit to B vitamins in slowing cognitive aging.

The claim that COSMOS is the “first” study to test the hypothesis hinges on some careful wordplay. Prior studies tested specific vitamins, not a multivitamin. In the discussion of the paper, these other studies are critiqued for being short term. But the Physicians’ Health Study II did in fact study a multivitamin and assessed cognitive performance on average 2.5 years after randomization. It found no benefit. The authors of COSMOS-Web critiqued the 2.5-year wait to perform cognitive testing, saying it would have missed any short-term benefits. Although, given that they simultaneously praised their 3 years of follow-up, the criticism is hard to fully accept or even understand.

Whether follow-up is short or long, uses individual vitamins or a multivitamin, the results excluding COSMOS are uniformly negative.

Do enough tests in the same population, and something will rise above the noise just by chance. When you get a positive result in your research, it’s always exciting. But when a slew of studies that came before you are negative, you aren’t groundbreaking. You’re an outlier.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I have written before about the COSMOS study and its finding that multivitamins (and chocolate) did not improve brain or cardiovascular health. So I was surprised to read that a “new” study found that vitamins can forestall dementia and age-related cognitive decline.

Upon closer look, the new data are neither new nor convincing, at least to me.

Chocolate and multivitamins for CVD and cancer prevention

The large randomized COSMOS trial was supposed to be the definitive study on chocolate that would establish its heart-health benefits without a doubt. Or, rather, the benefits of a cocoa bean extract in pill form given to healthy, older volunteers. The COSMOS study was negative. Chocolate, or the cocoa bean extract they used, did not reduce cardiovascular events.

And yet for all the prepublication importance attached to COSMOS, it is scarcely mentioned. Had it been positive, rest assured that Mars, the candy bar company that cofunded the research, and other interested parties would have been shouting it from the rooftops. As it is, they’re already spinning it.

Which brings us to the multivitamin component. COSMOS actually had a 2 × 2 design. In other words, there were four groups in this study: chocolate plus multivitamin, chocolate plus placebo, placebo plus multivitamin, and placebo plus placebo. This type of study design allows you to study two different interventions simultaneously, provided that they are independent and do not interact with each other. In addition to the primary cardiovascular endpoint, they also studied a cancer endpoint.

The multivitamin supplement didn’t reduce cardiovascular events either. Nor did it affect cancer outcomes. The main COSMOS study was negative and reinforced what countless other studies have proven: Taking a daily multivitamin does not reduce your risk of having a heart attack or developing cancer.

But wait, there’s more: COSMOS-Mind

But no researcher worth his salt studies just one or two endpoints in a study. The participants also underwent neurologic and memory testing. These results were reported separately in the COSMOS-Mind study.

COSMOS-Mind is often described as a separate (or “new”) study. In reality, it included the same participants from the original COSMOS trial and measured yet another primary outcome of cognitive performance on a series of tests administered by telephone. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with studying multiple outcomes in your patient population (after all, that salami isn’t going to slice itself), they cannot all be primary outcomes. Some, by necessity, must be secondary hypothesis–generating outcomes. If you test enough endpoints, multiple hypothesis testing dictates that eventually you will get a positive result simply by chance.

There was a time when the neurocognitive outcomes of COSMOS would have been reported in the same paper as the cardiovascular outcomes, but that time seems to have passed us by. Researchers live or die by the number of their publications, and there is an inherent advantage to squeezing as many publications as possible from the same dataset. Though, to be fair, the journal would probably have asked them to split up the paper as well.

In brief, the cocoa extract again fell short in COSMOS-Mind, but the multivitamin arm did better on the composite cognitive outcome. It was a fairly small difference – a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score at the 3-year mark (the z-score is the mean divided by the standard deviation). Much was also made of the fact that the improvement seemed to vary by prior history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Those with a history of CVD had a 0.11-point improvement, whereas those without had a 0.06-point improvement. The authors couldn’t offer a definitive explanation for these findings. Any argument that multivitamins improve cardiovascular health and therefore prevent vascular dementia has to contend with the fact that the main COSMOS study didn’t show a cardiovascular benefit for vitamins. Speculation that you are treating nutritional deficiencies is exactly that: speculation.

A more salient question is: What does a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score mean clinically? This study didn’t assess whether a multivitamin supplement prevented dementia or allowed people to live independently for longer. In fairness, that would have been exceptionally difficult to do and would have required a much longer study.

Their one attempt to quantify the cognitive benefit clinically was a calculation about normal age-related decline. Test scores were 0.045 points lower for every 1-year increase in age among participants (their mean age was 73 years). So the authors contend that a 0.07-point increase, or the 0.083-point increase that they found at year 3, corresponds to 1.8 years of age-related decline forestalled. Whether this is an appropriate assumption, I leave for the reader to decide.

COSMOS-Web and replication

The results of COSMOS-Mind were seemingly bolstered by the recent publication of COSMOS-Web. Although I’ve seen this study described as having replicated the results of COSMOS-Mind, that description is a bit misleading. This was yet another ancillary COSMOS study; more than half of the 2,262 participants in COSMOS-Mind were also included in COSMOS-Web. Replicating results in the same people isn’t true replication.

The main difference between COSMOS-Mind and COSMOS-Web is that the former used a telephone interview to administer the cognitive tests and the latter used the Internet. They also had different endpoints, with COSMOS-Web looking at immediate recall rather than a global test composite.

COSMOS-Web was a positive study in that patients getting the multivitamin supplement did better on the test for immediate memory recall (remembering a list of 20 words), though they didn’t improve on tests of memory retention, executive function, or novel object recognition (basically a test where subjects have to identify matching geometric patterns and then recall them later). They were able to remember an additional 0.71 word on average, compared with 0.44 word in the placebo group. (For the record, it found no benefit for the cocoa extract).

Everybody does better on memory tests the second time around because practice makes perfect, hence the improvement in the placebo group. This benefit at 1 year did not survive to the end of follow-up at 3 years, in contrast to COSMOS-Mind, where the benefit was not apparent at 1 year and seen only at year 3. A history of cardiovascular disease didn’t seem to affect the results in COSMOS-Web as it did in COSMOS-Mind. As far as replications go, COSMOS-Web has some very non-negligible differences, compared with COSMOS-Mind. This incongruity, especially given the overlap in the patient populations is hard to reconcile. If COSMOS-Web was supposed to assuage any doubts that persisted after COSMOS-Mind, it hasn’t for me.

One of these studies is not like the others

Finally, although the COSMOS trial and all its ancillary study analyses suggest a neurocognitive benefit to multivitamin supplementation, it’s not the first study to test the matter. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study looked at vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper. There was no benefit on any of the six cognitive tests administered to patients. The Women’s Health Study, the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study and PREADViSE have all failed to show any benefit to the various vitamins and minerals they studied. A meta-analysis of 11 trials found no benefit to B vitamins in slowing cognitive aging.

The claim that COSMOS is the “first” study to test the hypothesis hinges on some careful wordplay. Prior studies tested specific vitamins, not a multivitamin. In the discussion of the paper, these other studies are critiqued for being short term. But the Physicians’ Health Study II did in fact study a multivitamin and assessed cognitive performance on average 2.5 years after randomization. It found no benefit. The authors of COSMOS-Web critiqued the 2.5-year wait to perform cognitive testing, saying it would have missed any short-term benefits. Although, given that they simultaneously praised their 3 years of follow-up, the criticism is hard to fully accept or even understand.

Whether follow-up is short or long, uses individual vitamins or a multivitamin, the results excluding COSMOS are uniformly negative.

Do enough tests in the same population, and something will rise above the noise just by chance. When you get a positive result in your research, it’s always exciting. But when a slew of studies that came before you are negative, you aren’t groundbreaking. You’re an outlier.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I have written before about the COSMOS study and its finding that multivitamins (and chocolate) did not improve brain or cardiovascular health. So I was surprised to read that a “new” study found that vitamins can forestall dementia and age-related cognitive decline.

Upon closer look, the new data are neither new nor convincing, at least to me.

Chocolate and multivitamins for CVD and cancer prevention

The large randomized COSMOS trial was supposed to be the definitive study on chocolate that would establish its heart-health benefits without a doubt. Or, rather, the benefits of a cocoa bean extract in pill form given to healthy, older volunteers. The COSMOS study was negative. Chocolate, or the cocoa bean extract they used, did not reduce cardiovascular events.

And yet for all the prepublication importance attached to COSMOS, it is scarcely mentioned. Had it been positive, rest assured that Mars, the candy bar company that cofunded the research, and other interested parties would have been shouting it from the rooftops. As it is, they’re already spinning it.

Which brings us to the multivitamin component. COSMOS actually had a 2 × 2 design. In other words, there were four groups in this study: chocolate plus multivitamin, chocolate plus placebo, placebo plus multivitamin, and placebo plus placebo. This type of study design allows you to study two different interventions simultaneously, provided that they are independent and do not interact with each other. In addition to the primary cardiovascular endpoint, they also studied a cancer endpoint.

The multivitamin supplement didn’t reduce cardiovascular events either. Nor did it affect cancer outcomes. The main COSMOS study was negative and reinforced what countless other studies have proven: Taking a daily multivitamin does not reduce your risk of having a heart attack or developing cancer.

But wait, there’s more: COSMOS-Mind

But no researcher worth his salt studies just one or two endpoints in a study. The participants also underwent neurologic and memory testing. These results were reported separately in the COSMOS-Mind study.

COSMOS-Mind is often described as a separate (or “new”) study. In reality, it included the same participants from the original COSMOS trial and measured yet another primary outcome of cognitive performance on a series of tests administered by telephone. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with studying multiple outcomes in your patient population (after all, that salami isn’t going to slice itself), they cannot all be primary outcomes. Some, by necessity, must be secondary hypothesis–generating outcomes. If you test enough endpoints, multiple hypothesis testing dictates that eventually you will get a positive result simply by chance.

There was a time when the neurocognitive outcomes of COSMOS would have been reported in the same paper as the cardiovascular outcomes, but that time seems to have passed us by. Researchers live or die by the number of their publications, and there is an inherent advantage to squeezing as many publications as possible from the same dataset. Though, to be fair, the journal would probably have asked them to split up the paper as well.

In brief, the cocoa extract again fell short in COSMOS-Mind, but the multivitamin arm did better on the composite cognitive outcome. It was a fairly small difference – a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score at the 3-year mark (the z-score is the mean divided by the standard deviation). Much was also made of the fact that the improvement seemed to vary by prior history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Those with a history of CVD had a 0.11-point improvement, whereas those without had a 0.06-point improvement. The authors couldn’t offer a definitive explanation for these findings. Any argument that multivitamins improve cardiovascular health and therefore prevent vascular dementia has to contend with the fact that the main COSMOS study didn’t show a cardiovascular benefit for vitamins. Speculation that you are treating nutritional deficiencies is exactly that: speculation.

A more salient question is: What does a 0.07-point improvement on the z-score mean clinically? This study didn’t assess whether a multivitamin supplement prevented dementia or allowed people to live independently for longer. In fairness, that would have been exceptionally difficult to do and would have required a much longer study.

Their one attempt to quantify the cognitive benefit clinically was a calculation about normal age-related decline. Test scores were 0.045 points lower for every 1-year increase in age among participants (their mean age was 73 years). So the authors contend that a 0.07-point increase, or the 0.083-point increase that they found at year 3, corresponds to 1.8 years of age-related decline forestalled. Whether this is an appropriate assumption, I leave for the reader to decide.

COSMOS-Web and replication

The results of COSMOS-Mind were seemingly bolstered by the recent publication of COSMOS-Web. Although I’ve seen this study described as having replicated the results of COSMOS-Mind, that description is a bit misleading. This was yet another ancillary COSMOS study; more than half of the 2,262 participants in COSMOS-Mind were also included in COSMOS-Web. Replicating results in the same people isn’t true replication.

The main difference between COSMOS-Mind and COSMOS-Web is that the former used a telephone interview to administer the cognitive tests and the latter used the Internet. They also had different endpoints, with COSMOS-Web looking at immediate recall rather than a global test composite.

COSMOS-Web was a positive study in that patients getting the multivitamin supplement did better on the test for immediate memory recall (remembering a list of 20 words), though they didn’t improve on tests of memory retention, executive function, or novel object recognition (basically a test where subjects have to identify matching geometric patterns and then recall them later). They were able to remember an additional 0.71 word on average, compared with 0.44 word in the placebo group. (For the record, it found no benefit for the cocoa extract).

Everybody does better on memory tests the second time around because practice makes perfect, hence the improvement in the placebo group. This benefit at 1 year did not survive to the end of follow-up at 3 years, in contrast to COSMOS-Mind, where the benefit was not apparent at 1 year and seen only at year 3. A history of cardiovascular disease didn’t seem to affect the results in COSMOS-Web as it did in COSMOS-Mind. As far as replications go, COSMOS-Web has some very non-negligible differences, compared with COSMOS-Mind. This incongruity, especially given the overlap in the patient populations is hard to reconcile. If COSMOS-Web was supposed to assuage any doubts that persisted after COSMOS-Mind, it hasn’t for me.

One of these studies is not like the others

Finally, although the COSMOS trial and all its ancillary study analyses suggest a neurocognitive benefit to multivitamin supplementation, it’s not the first study to test the matter. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study looked at vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, zinc, and copper. There was no benefit on any of the six cognitive tests administered to patients. The Women’s Health Study, the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study and PREADViSE have all failed to show any benefit to the various vitamins and minerals they studied. A meta-analysis of 11 trials found no benefit to B vitamins in slowing cognitive aging.

The claim that COSMOS is the “first” study to test the hypothesis hinges on some careful wordplay. Prior studies tested specific vitamins, not a multivitamin. In the discussion of the paper, these other studies are critiqued for being short term. But the Physicians’ Health Study II did in fact study a multivitamin and assessed cognitive performance on average 2.5 years after randomization. It found no benefit. The authors of COSMOS-Web critiqued the 2.5-year wait to perform cognitive testing, saying it would have missed any short-term benefits. Although, given that they simultaneously praised their 3 years of follow-up, the criticism is hard to fully accept or even understand.

Whether follow-up is short or long, uses individual vitamins or a multivitamin, the results excluding COSMOS are uniformly negative.

Do enough tests in the same population, and something will rise above the noise just by chance. When you get a positive result in your research, it’s always exciting. But when a slew of studies that came before you are negative, you aren’t groundbreaking. You’re an outlier.

Dr. Labos is a cardiologist at Hôpital Notre-Dame, Montreal. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Overburdened: Health care workers more likely to die by suicide

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

If you run into a health care provider these days and ask, “How are you doing?” you’re likely to get a response like this one: “You know, hanging in there.” You smile and move on. But it may be time to go a step further. If you ask that next question – “No, really, how are you doing?” Well, you might need to carve out some time.

It’s been a rough few years for those of us in the health care professions. Our lives, dominated by COVID-related concerns at home, were equally dominated by COVID concerns at work. On the job, there were fewer and fewer of us around as exploitation and COVID-related stressors led doctors, nurses, and others to leave the profession entirely or take early retirement. Even now, I’m not sure we’ve recovered. Staffing in the hospitals is still a huge problem, and the persistence of impersonal meetings via teleconference – which not only prevent any sort of human connection but, audaciously, run from one into another without a break – robs us of even the subtle joy of walking from one hallway to another for 5 minutes of reflection before sitting down to view the next hastily cobbled together PowerPoint.

I’m speaking in generalities, of course.

I’m talking about how bad things are now because, in truth, they’ve never been great. And that may be why health care workers – people with jobs focused on serving others – are nevertheless at substantially increased risk for suicide.

Analyses through the years have shown that physicians tend to have higher rates of death from suicide than the general population. There are reasons for this that may not entirely be because of work-related stress. Doctors’ suicide attempts are more often lethal – we know what is likely to work, after all.

And, according to this paper in JAMA, it is those people who may be suffering most of all.

The study is a nationally representative sample based on the 2008 American Community Survey. Records were linked to the National Death Index through 2019.

Survey respondents were classified into five categories of health care worker, as you can see here. And 1,666,000 non–health care workers served as the control group.

Let’s take a look at the numbers.

I’m showing you age- and sex-standardized rates of death from suicide, starting with non–health care workers. In this study, physicians have similar rates of death from suicide to the general population. Nurses have higher rates, but health care support workers – nurses’ aides, home health aides – have rates nearly twice that of the general population.

Only social and behavioral health workers had rates lower than those in the general population, perhaps because they know how to access life-saving resources.

Of course, these groups differ in a lot of ways – education and income, for example. But even after adjustment for these factors as well as for sex, race, and marital status, the results persist. The only group with even a trend toward lower suicide rates are social and behavioral health workers.

There has been much hand-wringing about rates of physician suicide in the past. It is still a very real problem. But this paper finally highlights that there is a lot more to the health care profession than physicians. It’s time we acknowledge and support the people in our profession who seem to be suffering more than any of us: the aides, the techs, the support staff – the overworked and underpaid who have to deal with all the stresses that physicians like me face and then some.

There’s more to suicide risk than just your job; I know that. Family matters. Relationships matter. Medical and psychiatric illnesses matter. But to ignore this problem when it is right here, in our own house so to speak, can’t continue.

Might I suggest we start by asking someone in our profession – whether doctor, nurse, aide, or tech – how they are doing. How they are really doing. And when we are done listening, we use what we hear to advocate for real change.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

If you run into a health care provider these days and ask, “How are you doing?” you’re likely to get a response like this one: “You know, hanging in there.” You smile and move on. But it may be time to go a step further. If you ask that next question – “No, really, how are you doing?” Well, you might need to carve out some time.

It’s been a rough few years for those of us in the health care professions. Our lives, dominated by COVID-related concerns at home, were equally dominated by COVID concerns at work. On the job, there were fewer and fewer of us around as exploitation and COVID-related stressors led doctors, nurses, and others to leave the profession entirely or take early retirement. Even now, I’m not sure we’ve recovered. Staffing in the hospitals is still a huge problem, and the persistence of impersonal meetings via teleconference – which not only prevent any sort of human connection but, audaciously, run from one into another without a break – robs us of even the subtle joy of walking from one hallway to another for 5 minutes of reflection before sitting down to view the next hastily cobbled together PowerPoint.

I’m speaking in generalities, of course.

I’m talking about how bad things are now because, in truth, they’ve never been great. And that may be why health care workers – people with jobs focused on serving others – are nevertheless at substantially increased risk for suicide.

Analyses through the years have shown that physicians tend to have higher rates of death from suicide than the general population. There are reasons for this that may not entirely be because of work-related stress. Doctors’ suicide attempts are more often lethal – we know what is likely to work, after all.

And, according to this paper in JAMA, it is those people who may be suffering most of all.

The study is a nationally representative sample based on the 2008 American Community Survey. Records were linked to the National Death Index through 2019.

Survey respondents were classified into five categories of health care worker, as you can see here. And 1,666,000 non–health care workers served as the control group.

Let’s take a look at the numbers.

I’m showing you age- and sex-standardized rates of death from suicide, starting with non–health care workers. In this study, physicians have similar rates of death from suicide to the general population. Nurses have higher rates, but health care support workers – nurses’ aides, home health aides – have rates nearly twice that of the general population.

Only social and behavioral health workers had rates lower than those in the general population, perhaps because they know how to access life-saving resources.

Of course, these groups differ in a lot of ways – education and income, for example. But even after adjustment for these factors as well as for sex, race, and marital status, the results persist. The only group with even a trend toward lower suicide rates are social and behavioral health workers.

There has been much hand-wringing about rates of physician suicide in the past. It is still a very real problem. But this paper finally highlights that there is a lot more to the health care profession than physicians. It’s time we acknowledge and support the people in our profession who seem to be suffering more than any of us: the aides, the techs, the support staff – the overworked and underpaid who have to deal with all the stresses that physicians like me face and then some.

There’s more to suicide risk than just your job; I know that. Family matters. Relationships matter. Medical and psychiatric illnesses matter. But to ignore this problem when it is right here, in our own house so to speak, can’t continue.

Might I suggest we start by asking someone in our profession – whether doctor, nurse, aide, or tech – how they are doing. How they are really doing. And when we are done listening, we use what we hear to advocate for real change.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

If you run into a health care provider these days and ask, “How are you doing?” you’re likely to get a response like this one: “You know, hanging in there.” You smile and move on. But it may be time to go a step further. If you ask that next question – “No, really, how are you doing?” Well, you might need to carve out some time.

It’s been a rough few years for those of us in the health care professions. Our lives, dominated by COVID-related concerns at home, were equally dominated by COVID concerns at work. On the job, there were fewer and fewer of us around as exploitation and COVID-related stressors led doctors, nurses, and others to leave the profession entirely or take early retirement. Even now, I’m not sure we’ve recovered. Staffing in the hospitals is still a huge problem, and the persistence of impersonal meetings via teleconference – which not only prevent any sort of human connection but, audaciously, run from one into another without a break – robs us of even the subtle joy of walking from one hallway to another for 5 minutes of reflection before sitting down to view the next hastily cobbled together PowerPoint.

I’m speaking in generalities, of course.

I’m talking about how bad things are now because, in truth, they’ve never been great. And that may be why health care workers – people with jobs focused on serving others – are nevertheless at substantially increased risk for suicide.

Analyses through the years have shown that physicians tend to have higher rates of death from suicide than the general population. There are reasons for this that may not entirely be because of work-related stress. Doctors’ suicide attempts are more often lethal – we know what is likely to work, after all.

And, according to this paper in JAMA, it is those people who may be suffering most of all.

The study is a nationally representative sample based on the 2008 American Community Survey. Records were linked to the National Death Index through 2019.

Survey respondents were classified into five categories of health care worker, as you can see here. And 1,666,000 non–health care workers served as the control group.

Let’s take a look at the numbers.

I’m showing you age- and sex-standardized rates of death from suicide, starting with non–health care workers. In this study, physicians have similar rates of death from suicide to the general population. Nurses have higher rates, but health care support workers – nurses’ aides, home health aides – have rates nearly twice that of the general population.

Only social and behavioral health workers had rates lower than those in the general population, perhaps because they know how to access life-saving resources.

Of course, these groups differ in a lot of ways – education and income, for example. But even after adjustment for these factors as well as for sex, race, and marital status, the results persist. The only group with even a trend toward lower suicide rates are social and behavioral health workers.

There has been much hand-wringing about rates of physician suicide in the past. It is still a very real problem. But this paper finally highlights that there is a lot more to the health care profession than physicians. It’s time we acknowledge and support the people in our profession who seem to be suffering more than any of us: the aides, the techs, the support staff – the overworked and underpaid who have to deal with all the stresses that physicians like me face and then some.

There’s more to suicide risk than just your job; I know that. Family matters. Relationships matter. Medical and psychiatric illnesses matter. But to ignore this problem when it is right here, in our own house so to speak, can’t continue.

Might I suggest we start by asking someone in our profession – whether doctor, nurse, aide, or tech – how they are doing. How they are really doing. And when we are done listening, we use what we hear to advocate for real change.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The unappreciated healing power of awe

I’m standing atop the Klein Matterhorn, staring out at the Alps, their moonscape peaks forming a jagged, terrifying, glorious white horizon.

I am small. But the emotions are huge. The joy: I get to be a part of all this today. The fear: It could kill me. More than kill me, it could consume me.

That’s what I always used to feel when training in Zermatt, Switzerland.

I was lucky. As a former U.S. Ski Team athlete, I was regularly able to experience such magnificent scenescapes – and feel the tactile insanity of it, too, the rise and fall of helicopters or trams taking us up the mountains, the slicing, frigid air at the summit, and the lurking on-edge feeling that you, tiny human, really aren’t meant to be standing where you are standing.

“Awe puts things in perspective,” said Craig Anderson, PhD, postdoctoral scholar at Washington University at St. Louis, and researcher of emotions and behavior. “It’s about feeling connected with people and part of the larger collective – and that makes it okay to feel small.”

Our modern world is at odds with awe. We tend to shrink into our daily lives, our problems, our devices, and the real-time emotional reactions to those things, especially anger.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

‘In the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear’

That’s how New York University ethical leadership professor Jonathan Haidt, PhD, and psychology professor Dacher Keltner, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, defined awe in a seminal report from 2003.

The feeling is composed of two elements: perceived vastness (sensing something larger than ourselves) and accommodation (our need to process and understand that vastness). The researchers also wrote that awe could “change the course of life in profound and permanent ways.”

“There’s a correlation between people who are happier and those who report more feelings of awe,” said David Yaden, PhD, assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthor of “The Varieties of Spiritual Experience.” “It’s unclear, though, which way the causality runs. Is it that having more awe experiences makes people happier? Or that happy people have more awe. But there is a correlation.”

One aspect about awe that’s clear: When people experience it, they report feeling more connected. And that sense of connection can lead to prosocial behavior – such as serving others and engaging with one’s community.

“Feelings of isolation are quite difficult, and we’re social creatures, so when we feel connected, we can benefit from it,” Dr. Yaden said.

A 2022 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology revealed that awe “awakens self-transcendence, which in turn invigorates pursuit of the authentic self.”

While these effects can be seen as one individual’s benefits, the researchers posited that they also lead to prosocial behaviors. Another study conducted by the same scientists showed that awe led to greater-good behavior during the pandemic, to the tune of an increased willingness to donate blood. In this study, researchers also cited a correlation between feelings of awe and increased empathy.

The awe experience

Dr. Yaden joined Dr. Keltner and other researchers in creating a scale for the “awe experience,” and found six related factors: a feeling that time momentarily slows; a sense of self-diminishment (your sense of self becomes smaller); a sense of connectedness; feeling in the presence of something grand; the need to mentally process the experience; and physical changes, like goosebumps or feeling your jaw slightly drop.

“Any of these factors can be large or small,” Dr. Yaden noted, adding that awe can also feel positive or negative. A hurricane can instill awe, for example, and the experience might not be pleasant.

However, “it’s more common for the awe experience to be positive,” Dr. Yaden said.

How your brain processes awe

Functional MRI, by which brain activity is measured through blood flow, allows researchers to see what’s happening in the brain after an awe experience.

One study that was conducted in the Netherlands and was published in the journal Human Brain Mapping suggested that certain parts of the brain that are responsible for self-reflection were less “activated” when participants watched awe-inspiring videos.

The researchers posit that the “captivating nature of awe stimuli” could be responsible for such reductions, meaning participants’ brains were geared more toward feelings of connection with others or something greater – and a smaller sense of self.

Another study published in the journal Emotion revealed a link between awe and lower levels of inflammatory cytokines, so awe could have positive and potentially protective health benefits, as well.

And of course there are the physical and emotional benefits of nature, as dozens of studies reveal. Dr. Anderson’s research in the journal Emotion showed that nature “experiences” led to more feelings of awe and that the effects of nature also reduced stress and increased well-being.

Why we turn away from awe

The world we inhabit day to day isn’t conducive to experiencing awe – indoors, seated, reacting negatively to work or social media. The mentalities we forge because of this sometimes work against experiencing any form of awe.

Example: Some people don’t like to feel small. That requires a capacity for humility.

“That [feeling] can be threatening,” noted Dr. Anderson, who earned his doctorate studying as part of Dr. Keltner’s “Project Awe” research team at UC Berkeley.

The pandemic and politics and rise in angry Internet culture also contribute. And if you didn’t know, humans have a “negativity bias.”

“Our responses to stress tend to be stronger in magnitude than responses to positive things,” Dr. Anderson said. “Browsing the Internet and seeing negative things can hijack our responses. Anger really narrows our attention on what makes us angry.”

In that sense, anger is the antithesis of awe. As Dr. Anderson puts it: Awe broadens our attention to the world and “opens us up to other people and possibilities,” he said. “When we’re faced with daily hassles, when we experience something vast and awe-inspiring, those other problems aren’t as big of a deal.”

We crave awe in spite of ourselves

An awful lot of us are out there seeking awe, knowingly or not.

People have been stopping at scenic overlooks and climbing local peaks since forever, but let’s start with record-setting attendance at the most basic and accessible source of natural awe we have in the United States: national parks.

In 2022, 68% of the 312 million visitors sought out nature-based or recreational park activities (as opposed to historical or cultural activities). Even though a rise in national park visits in 2021 and 2022 could be attributed to pandemic-related behavior (the need for social distancing and/or the desire to get outside), people were flocking to parks prior to COVID-19. In fact, 33 parks set visitation records in 2019; 12 did so in 2022.

We also seek awe in man-made spectacle. Consider annual visitor numbers for the following:

- Golden Gate Bridge: 10 million

- : 4 million

- : 1.62 million

And what about the most awe-inducing experience ever manufactured: Space tourism. While catering to the wealthy for now, flying to space allows untrained people to enjoy something only a chosen few astronauts have been able to feel: the “overview effect,” a term coined by author Frank White for the shift in perspective that occurs in people who see Earth from space.

Upon his return from his Blue Origin flight, actor William Shatner was candid about his emotional experience. “I was crying,” he told NPR. “I didn’t know what I was crying about. It was the death that I saw in space and the lifeforce that I saw coming from the planet – the blue, the beige, and the white. And I realized one was death and the other was life.”

We want awe. We want to feel this way.

Adding everyday awe to your life

It may seem counterintuitive: Most awe-inspiring places are special occasion destinations, but in truth it’s possible to find awe each day. Outdoors and indoors.

Park Rx America, led by Robert Zarr, MD, MPH, boasts a network of nearly 1500 healthcare providers ready to “prescribe” walks or time in nature as part of healing. “Our growing community of ‘nature prescribers’ incorporate nature as a treatment option for their willing clients and patients,” Dr. Zarr said.

He also noted that awe is all about where you look, including in small places.

“Something as simple as going for a walk and stopping to notice the complexity of fractal patterns in the leaves, for example, leaves me with a sense of awe,” he said. “Although difficult to measure, there is no doubt that an important part of our health is intricately linked to these daily awe-filled moments.”

Nature is not the only way. Dr. Yaden suggested that going to a museum to see art or sporting events is also a way to experience the feeling.

An unexpected source of man-made awe: Screens. A study published in Nature showed that immersive video experiences (in this case, one achieved by virtual reality) were effective in eliciting an awe response in participants.

While virtual reality isn’t ubiquitous, immersive film experiences are. IMAX screens were created for just this purpose (as anyone who saw the Avatar films in this format can attest).

Is it perfect? No. But whether you’re witnessing a birth, hiking an autumn trail bathed in orange, or letting off a little gasp when you see Oppenheimer’s nuclear explosion in 70 mm, it all counts.

Because it’s not about the thing. It’s about your openness to be awed by the thing.

I’m a little like Dr. Zarr in that I can find wonder in the crystalline structures of a snowflake. And I also love to hike and inhale expansive views. If you can get to Switzerland, and specifically Zermatt, take the old red tram to the top. I highly recommend it.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I’m standing atop the Klein Matterhorn, staring out at the Alps, their moonscape peaks forming a jagged, terrifying, glorious white horizon.

I am small. But the emotions are huge. The joy: I get to be a part of all this today. The fear: It could kill me. More than kill me, it could consume me.

That’s what I always used to feel when training in Zermatt, Switzerland.

I was lucky. As a former U.S. Ski Team athlete, I was regularly able to experience such magnificent scenescapes – and feel the tactile insanity of it, too, the rise and fall of helicopters or trams taking us up the mountains, the slicing, frigid air at the summit, and the lurking on-edge feeling that you, tiny human, really aren’t meant to be standing where you are standing.

“Awe puts things in perspective,” said Craig Anderson, PhD, postdoctoral scholar at Washington University at St. Louis, and researcher of emotions and behavior. “It’s about feeling connected with people and part of the larger collective – and that makes it okay to feel small.”

Our modern world is at odds with awe. We tend to shrink into our daily lives, our problems, our devices, and the real-time emotional reactions to those things, especially anger.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

‘In the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear’

That’s how New York University ethical leadership professor Jonathan Haidt, PhD, and psychology professor Dacher Keltner, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, defined awe in a seminal report from 2003.

The feeling is composed of two elements: perceived vastness (sensing something larger than ourselves) and accommodation (our need to process and understand that vastness). The researchers also wrote that awe could “change the course of life in profound and permanent ways.”

“There’s a correlation between people who are happier and those who report more feelings of awe,” said David Yaden, PhD, assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthor of “The Varieties of Spiritual Experience.” “It’s unclear, though, which way the causality runs. Is it that having more awe experiences makes people happier? Or that happy people have more awe. But there is a correlation.”

One aspect about awe that’s clear: When people experience it, they report feeling more connected. And that sense of connection can lead to prosocial behavior – such as serving others and engaging with one’s community.

“Feelings of isolation are quite difficult, and we’re social creatures, so when we feel connected, we can benefit from it,” Dr. Yaden said.

A 2022 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology revealed that awe “awakens self-transcendence, which in turn invigorates pursuit of the authentic self.”

While these effects can be seen as one individual’s benefits, the researchers posited that they also lead to prosocial behaviors. Another study conducted by the same scientists showed that awe led to greater-good behavior during the pandemic, to the tune of an increased willingness to donate blood. In this study, researchers also cited a correlation between feelings of awe and increased empathy.

The awe experience

Dr. Yaden joined Dr. Keltner and other researchers in creating a scale for the “awe experience,” and found six related factors: a feeling that time momentarily slows; a sense of self-diminishment (your sense of self becomes smaller); a sense of connectedness; feeling in the presence of something grand; the need to mentally process the experience; and physical changes, like goosebumps or feeling your jaw slightly drop.

“Any of these factors can be large or small,” Dr. Yaden noted, adding that awe can also feel positive or negative. A hurricane can instill awe, for example, and the experience might not be pleasant.

However, “it’s more common for the awe experience to be positive,” Dr. Yaden said.

How your brain processes awe

Functional MRI, by which brain activity is measured through blood flow, allows researchers to see what’s happening in the brain after an awe experience.

One study that was conducted in the Netherlands and was published in the journal Human Brain Mapping suggested that certain parts of the brain that are responsible for self-reflection were less “activated” when participants watched awe-inspiring videos.

The researchers posit that the “captivating nature of awe stimuli” could be responsible for such reductions, meaning participants’ brains were geared more toward feelings of connection with others or something greater – and a smaller sense of self.

Another study published in the journal Emotion revealed a link between awe and lower levels of inflammatory cytokines, so awe could have positive and potentially protective health benefits, as well.

And of course there are the physical and emotional benefits of nature, as dozens of studies reveal. Dr. Anderson’s research in the journal Emotion showed that nature “experiences” led to more feelings of awe and that the effects of nature also reduced stress and increased well-being.

Why we turn away from awe

The world we inhabit day to day isn’t conducive to experiencing awe – indoors, seated, reacting negatively to work or social media. The mentalities we forge because of this sometimes work against experiencing any form of awe.

Example: Some people don’t like to feel small. That requires a capacity for humility.

“That [feeling] can be threatening,” noted Dr. Anderson, who earned his doctorate studying as part of Dr. Keltner’s “Project Awe” research team at UC Berkeley.

The pandemic and politics and rise in angry Internet culture also contribute. And if you didn’t know, humans have a “negativity bias.”

“Our responses to stress tend to be stronger in magnitude than responses to positive things,” Dr. Anderson said. “Browsing the Internet and seeing negative things can hijack our responses. Anger really narrows our attention on what makes us angry.”

In that sense, anger is the antithesis of awe. As Dr. Anderson puts it: Awe broadens our attention to the world and “opens us up to other people and possibilities,” he said. “When we’re faced with daily hassles, when we experience something vast and awe-inspiring, those other problems aren’t as big of a deal.”

We crave awe in spite of ourselves

An awful lot of us are out there seeking awe, knowingly or not.

People have been stopping at scenic overlooks and climbing local peaks since forever, but let’s start with record-setting attendance at the most basic and accessible source of natural awe we have in the United States: national parks.

In 2022, 68% of the 312 million visitors sought out nature-based or recreational park activities (as opposed to historical or cultural activities). Even though a rise in national park visits in 2021 and 2022 could be attributed to pandemic-related behavior (the need for social distancing and/or the desire to get outside), people were flocking to parks prior to COVID-19. In fact, 33 parks set visitation records in 2019; 12 did so in 2022.

We also seek awe in man-made spectacle. Consider annual visitor numbers for the following:

- Golden Gate Bridge: 10 million

- : 4 million

- : 1.62 million

And what about the most awe-inducing experience ever manufactured: Space tourism. While catering to the wealthy for now, flying to space allows untrained people to enjoy something only a chosen few astronauts have been able to feel: the “overview effect,” a term coined by author Frank White for the shift in perspective that occurs in people who see Earth from space.

Upon his return from his Blue Origin flight, actor William Shatner was candid about his emotional experience. “I was crying,” he told NPR. “I didn’t know what I was crying about. It was the death that I saw in space and the lifeforce that I saw coming from the planet – the blue, the beige, and the white. And I realized one was death and the other was life.”

We want awe. We want to feel this way.

Adding everyday awe to your life

It may seem counterintuitive: Most awe-inspiring places are special occasion destinations, but in truth it’s possible to find awe each day. Outdoors and indoors.

Park Rx America, led by Robert Zarr, MD, MPH, boasts a network of nearly 1500 healthcare providers ready to “prescribe” walks or time in nature as part of healing. “Our growing community of ‘nature prescribers’ incorporate nature as a treatment option for their willing clients and patients,” Dr. Zarr said.

He also noted that awe is all about where you look, including in small places.

“Something as simple as going for a walk and stopping to notice the complexity of fractal patterns in the leaves, for example, leaves me with a sense of awe,” he said. “Although difficult to measure, there is no doubt that an important part of our health is intricately linked to these daily awe-filled moments.”

Nature is not the only way. Dr. Yaden suggested that going to a museum to see art or sporting events is also a way to experience the feeling.

An unexpected source of man-made awe: Screens. A study published in Nature showed that immersive video experiences (in this case, one achieved by virtual reality) were effective in eliciting an awe response in participants.

While virtual reality isn’t ubiquitous, immersive film experiences are. IMAX screens were created for just this purpose (as anyone who saw the Avatar films in this format can attest).

Is it perfect? No. But whether you’re witnessing a birth, hiking an autumn trail bathed in orange, or letting off a little gasp when you see Oppenheimer’s nuclear explosion in 70 mm, it all counts.

Because it’s not about the thing. It’s about your openness to be awed by the thing.

I’m a little like Dr. Zarr in that I can find wonder in the crystalline structures of a snowflake. And I also love to hike and inhale expansive views. If you can get to Switzerland, and specifically Zermatt, take the old red tram to the top. I highly recommend it.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I’m standing atop the Klein Matterhorn, staring out at the Alps, their moonscape peaks forming a jagged, terrifying, glorious white horizon.

I am small. But the emotions are huge. The joy: I get to be a part of all this today. The fear: It could kill me. More than kill me, it could consume me.

That’s what I always used to feel when training in Zermatt, Switzerland.

I was lucky. As a former U.S. Ski Team athlete, I was regularly able to experience such magnificent scenescapes – and feel the tactile insanity of it, too, the rise and fall of helicopters or trams taking us up the mountains, the slicing, frigid air at the summit, and the lurking on-edge feeling that you, tiny human, really aren’t meant to be standing where you are standing.

“Awe puts things in perspective,” said Craig Anderson, PhD, postdoctoral scholar at Washington University at St. Louis, and researcher of emotions and behavior. “It’s about feeling connected with people and part of the larger collective – and that makes it okay to feel small.”

Our modern world is at odds with awe. We tend to shrink into our daily lives, our problems, our devices, and the real-time emotional reactions to those things, especially anger.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

‘In the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear’

That’s how New York University ethical leadership professor Jonathan Haidt, PhD, and psychology professor Dacher Keltner, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, defined awe in a seminal report from 2003.

The feeling is composed of two elements: perceived vastness (sensing something larger than ourselves) and accommodation (our need to process and understand that vastness). The researchers also wrote that awe could “change the course of life in profound and permanent ways.”

“There’s a correlation between people who are happier and those who report more feelings of awe,” said David Yaden, PhD, assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthor of “The Varieties of Spiritual Experience.” “It’s unclear, though, which way the causality runs. Is it that having more awe experiences makes people happier? Or that happy people have more awe. But there is a correlation.”

One aspect about awe that’s clear: When people experience it, they report feeling more connected. And that sense of connection can lead to prosocial behavior – such as serving others and engaging with one’s community.

“Feelings of isolation are quite difficult, and we’re social creatures, so when we feel connected, we can benefit from it,” Dr. Yaden said.

A 2022 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology revealed that awe “awakens self-transcendence, which in turn invigorates pursuit of the authentic self.”

While these effects can be seen as one individual’s benefits, the researchers posited that they also lead to prosocial behaviors. Another study conducted by the same scientists showed that awe led to greater-good behavior during the pandemic, to the tune of an increased willingness to donate blood. In this study, researchers also cited a correlation between feelings of awe and increased empathy.

The awe experience

Dr. Yaden joined Dr. Keltner and other researchers in creating a scale for the “awe experience,” and found six related factors: a feeling that time momentarily slows; a sense of self-diminishment (your sense of self becomes smaller); a sense of connectedness; feeling in the presence of something grand; the need to mentally process the experience; and physical changes, like goosebumps or feeling your jaw slightly drop.

“Any of these factors can be large or small,” Dr. Yaden noted, adding that awe can also feel positive or negative. A hurricane can instill awe, for example, and the experience might not be pleasant.

However, “it’s more common for the awe experience to be positive,” Dr. Yaden said.

How your brain processes awe

Functional MRI, by which brain activity is measured through blood flow, allows researchers to see what’s happening in the brain after an awe experience.

One study that was conducted in the Netherlands and was published in the journal Human Brain Mapping suggested that certain parts of the brain that are responsible for self-reflection were less “activated” when participants watched awe-inspiring videos.

The researchers posit that the “captivating nature of awe stimuli” could be responsible for such reductions, meaning participants’ brains were geared more toward feelings of connection with others or something greater – and a smaller sense of self.

Another study published in the journal Emotion revealed a link between awe and lower levels of inflammatory cytokines, so awe could have positive and potentially protective health benefits, as well.

And of course there are the physical and emotional benefits of nature, as dozens of studies reveal. Dr. Anderson’s research in the journal Emotion showed that nature “experiences” led to more feelings of awe and that the effects of nature also reduced stress and increased well-being.

Why we turn away from awe

The world we inhabit day to day isn’t conducive to experiencing awe – indoors, seated, reacting negatively to work or social media. The mentalities we forge because of this sometimes work against experiencing any form of awe.

Example: Some people don’t like to feel small. That requires a capacity for humility.

“That [feeling] can be threatening,” noted Dr. Anderson, who earned his doctorate studying as part of Dr. Keltner’s “Project Awe” research team at UC Berkeley.

The pandemic and politics and rise in angry Internet culture also contribute. And if you didn’t know, humans have a “negativity bias.”

“Our responses to stress tend to be stronger in magnitude than responses to positive things,” Dr. Anderson said. “Browsing the Internet and seeing negative things can hijack our responses. Anger really narrows our attention on what makes us angry.”

In that sense, anger is the antithesis of awe. As Dr. Anderson puts it: Awe broadens our attention to the world and “opens us up to other people and possibilities,” he said. “When we’re faced with daily hassles, when we experience something vast and awe-inspiring, those other problems aren’t as big of a deal.”

We crave awe in spite of ourselves

An awful lot of us are out there seeking awe, knowingly or not.

People have been stopping at scenic overlooks and climbing local peaks since forever, but let’s start with record-setting attendance at the most basic and accessible source of natural awe we have in the United States: national parks.

In 2022, 68% of the 312 million visitors sought out nature-based or recreational park activities (as opposed to historical or cultural activities). Even though a rise in national park visits in 2021 and 2022 could be attributed to pandemic-related behavior (the need for social distancing and/or the desire to get outside), people were flocking to parks prior to COVID-19. In fact, 33 parks set visitation records in 2019; 12 did so in 2022.

We also seek awe in man-made spectacle. Consider annual visitor numbers for the following:

- Golden Gate Bridge: 10 million

- : 4 million

- : 1.62 million

And what about the most awe-inducing experience ever manufactured: Space tourism. While catering to the wealthy for now, flying to space allows untrained people to enjoy something only a chosen few astronauts have been able to feel: the “overview effect,” a term coined by author Frank White for the shift in perspective that occurs in people who see Earth from space.

Upon his return from his Blue Origin flight, actor William Shatner was candid about his emotional experience. “I was crying,” he told NPR. “I didn’t know what I was crying about. It was the death that I saw in space and the lifeforce that I saw coming from the planet – the blue, the beige, and the white. And I realized one was death and the other was life.”

We want awe. We want to feel this way.

Adding everyday awe to your life

It may seem counterintuitive: Most awe-inspiring places are special occasion destinations, but in truth it’s possible to find awe each day. Outdoors and indoors.

Park Rx America, led by Robert Zarr, MD, MPH, boasts a network of nearly 1500 healthcare providers ready to “prescribe” walks or time in nature as part of healing. “Our growing community of ‘nature prescribers’ incorporate nature as a treatment option for their willing clients and patients,” Dr. Zarr said.

He also noted that awe is all about where you look, including in small places.

“Something as simple as going for a walk and stopping to notice the complexity of fractal patterns in the leaves, for example, leaves me with a sense of awe,” he said. “Although difficult to measure, there is no doubt that an important part of our health is intricately linked to these daily awe-filled moments.”

Nature is not the only way. Dr. Yaden suggested that going to a museum to see art or sporting events is also a way to experience the feeling.

An unexpected source of man-made awe: Screens. A study published in Nature showed that immersive video experiences (in this case, one achieved by virtual reality) were effective in eliciting an awe response in participants.

While virtual reality isn’t ubiquitous, immersive film experiences are. IMAX screens were created for just this purpose (as anyone who saw the Avatar films in this format can attest).

Is it perfect? No. But whether you’re witnessing a birth, hiking an autumn trail bathed in orange, or letting off a little gasp when you see Oppenheimer’s nuclear explosion in 70 mm, it all counts.

Because it’s not about the thing. It’s about your openness to be awed by the thing.

I’m a little like Dr. Zarr in that I can find wonder in the crystalline structures of a snowflake. And I also love to hike and inhale expansive views. If you can get to Switzerland, and specifically Zermatt, take the old red tram to the top. I highly recommend it.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How to get paid if your patient passes on

The death of a patient comes with many challenges for physicians, including a range of emotional and professional issues. Beyond those concerns,

“When a patient passes away, obviously there is, unfortunately, a lot of paperwork and stress for families, and it’s a very difficult situation,” says Shikha Jain, MD, an oncologist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Talking about finances in that moment can be difficult and uncomfortable, and one thing I’d recommend is that the physicians themselves not get involved.”

Instead, Dr. Jain said, someone in the billing department in the practice or the hospital should take a lead on dealing with any outstanding debts.

“That doctor-patient relationship is a very precious relationship, so you don’t want to mix that financial aspect of providing care with the doctor-patient relationship,” Dr. Jain said. “That’s one thing that’s really important.”

The best approach in such situations is for practices to have a standing policy in place that dictates how to handle bills once a patient has died.

In most cases, the executor of the patient’s will must inform all creditors, including doctors, that the decedent has died, but sometimes there’s a delay.

Hoping the doctor’s office writes it off

“Even though the person in charge of the estate is supposed to contact the doctor’s office and let them know when a patient has passed, that doesn’t always happen,” says Hope Wen, head of billing at practice management platform Soundry Health. “It can be very challenging to track down that information, and sometimes they’re just crossing their fingers hoping that the doctor’s office will just write off the balance, which they often do.”

Some offices use a service that compares accounts receivable lists to Social Security death files and state records to identify deaths more quickly. Some physicians might also use a debt collection agency or an attorney who has experience collecting decedent debts and dealing with executors and probate courts.

Once the practice becomes aware that a patient has died, it can no longer send communications to the name and address on file, although it can continue to go through the billing process with the insurer for any bills incurred up to the date of the death.

At that point, the estate becomes responsible for the debt, and all communication must go to the executor of the estate (in some states, this might be called a personal representative). The office can reach out to any contacts on file to see if they are able to identify the executor.

“You want to do that in a compassionate way,” says Jack Brown III, JD, MBA, president of Gulf Coast Collection Bureau. “You’ll tell them you’re sorry for their loss, but you’re wondering who is responsible for the estate. Once you’ve identified that person and gotten their letter of administration from the probate court or a power of attorney, then you can speak with that person as if they were the patient.”

The names of executors are also public record and are available through the probate court (sometimes called the surrogate court) in the county where the decedent lived.

“Even if there’s no will or no executive named, the court will appoint an administrator for the estate, which is usually a family member,” said Robert Bernstein, an estate lawyer in Parsippany, N.J. “Their information will be on file in the court.”

Insurance coverage

Typically, insurance will pay for treatment (after deductibles and copays) up until the date of the patient’s death. But, of course, it can take months for some insurance companies to make their final payments, allowing physicians to know exactly how much they’re owed by that estate. In such cases, it’s important for physicians to know the rules in the decedent’s state for how long they have to file a claim.

Most states require that claims occur within 6-9 months of the person’s death. However, in some states, claimants can continue to file for much longer if the estate has not yet paid out all of its assets.

“Sometimes there is real estate to sell or a business to wind down, and it can take years for the estate to distribute all of the assets,” Mr. Bernstein says. “If it’s a year later and they still haven’t distributed the assets, the physician can still file the claim and should be paid.”

In some cases, especially if the decedent received compassionate, quality care, their family will want to make good on any outstanding debts to the health care providers who took care of their loved ones in their final days. In other cases, especially when a family member has had a long illness, their assets have been depleted over time or were transferred to other family members so that there is little left in the estate itself when the patient dies.

Regardless of other circumstances, the estate alone is responsible for such payments, and family members, including spouses and children, typically have no liability. (Though rarely enforced, some states do have filial responsibility laws that could hold children responsible for their parents’ debts, including unpaid medical bills. In addition, states with community property laws might require a surviving spouse to cover their partner’s debt, even after death.)

The probate process varies from state to state, but in general, the probate system and the executor will gather all existing assets and then notify all creditors about how to submit a claim. Typically, the claim will need to include information about how much is owed and documentation, such as bills and an explanation of benefits to back up the claim. It should be borne in mind that even those who’ve passed away have privacy protections under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, so practices must be careful as to how much information they’re sharing through their claim.

Once the estate has received all the claims, the executor will follow a priority of claims, starting with secured creditors. Typically, medical bills, especially those incurred in the last 90 days of the decedent’s life, have priority in the probate process, Mr. Brown says.

How to minimize losses