User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

MIS-C is a serious immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection

One of the take-away messages from a review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is that clinicians treating this condition “need to be comfortable with uncertainty,” Melissa Hazen, MD, said at a synthesis of multiple published case series and personal experience summarized at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

She emphasized MIS-C patient care “requires flexibility,” and she advised clinicians managing these patients to open the lines of communication with the many specialists who often are required to deal with complications affecting an array of organ systems.

MIS-C might best be understood as the most serious manifestation of an immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection that ranges from transient mild symptoms to the life-threatening multiple organ involvement that characterizes this newly recognized threat. Although “most children who encounter this pathogen only develop mild disease,” the spectrum of the disease can move in a subset of patients to a “Kawasaki-like illness” without hemodynamic instability and then to MIS-C “with highly elevated systemic inflammatory markers and multiple organ involvement,” explained Dr. Hazen, an attending physician in the rheumatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

most of which have only recently reached publication, according to Dr. Hazen. In general, the description of the most common symptoms and their course has been relatively consistent.

In 186 cases of MIS-C collected in a study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 148 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 90 patients (48%) received vasoactive support, 37 (20%) received mechanical ventilation, and 4 (2%) died.1 The median age was 8 years (range, 3-13 years) in this study. The case definition was fever for at least 24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation, multisystem organ involvement, and evidence of COVID-19 infection. In this cohort of 186 children, 92% had gastrointestinal, 80% had cardiovascular, 76% had hematologic, and 70% had respiratory system involvement.

In a different series of 95 cases collected in New York State, 79 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 61 (62%) received vasoactive support, 10 (10%) received mechanical ventilation, 4 (4%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and 2 (2%) died. 2 Thirty-one percent patients were aged 0-5 years, 42% were 6-12 years, and 26% were 13-20 years of age. In that series, for which the case definition was elevation of two or more inflammatory markers, virologic evidence of COVID-19 infection, 80% had gastrointestinal system involvement, and 53% had evidence of myocarditis.

In both of these series, as well as others published and unpublished, the peak in MIS-C cases has occurred about 3 to 4 weeks after peak COVID-19 activity, according to Diana Lee, MD, a pediatrician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. This pattern, reported by others, was observed in New York State, where 230 cases of MIS-C were collected from the beginning of May until the end of June, which reflected this 3- to 4-week delay in peak incidence.

“This does seem to be a rare syndrome since this [group of] 230 cases is amongst the entire population of children in New York State. So, yes, we should be keeping this in mind in our differential, but we should not forget all the other reasons that children can have a fever,” she said.

Both Dr. Hazen and Dr. Lee cautioned that MIS-C, despite a general consistency among published studies, remains a moving target in regard to how it is being characterized. In a 2-day period in May, the CDC, the World Health Organization, and New York State all issued descriptions of MIS-C, employing compatible but slightly different terminology and diagnostic criteria. Many questions regarding optimal methods of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up remain unanswered.

Questions regarding the risk to the cardiovascular system, one of the organs most commonly affected in MIS-C, are among the most urgent. It is not now clear how best to monitor cardiovascular involvement, how to intervene, and how to follow patients in the postinfection period, according to Kevin G. Friedman, MD, a pediatrician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an attending physician in the department of cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“The most frequent complication we have seen is ventricular dysfunction, which occurs in about half of these patients,” he reported. “Usually it is in the mild to moderate range, but occasionally patients have an ejection fraction of less than 40%.”

Coronary abnormalities, typically in the form of dilations or small aneurysms, occur in 10%-20% of children with MIS-C, according to Dr. Friedman. Giant aneurysms have been reported.

“Some of these findings can progress including in both the acute phase and, particularly for the coronary aneurysms, in the subacute phase. We recommend echocardiograms and EKGs at diagnosis and at 1-2 weeks to recheck coronary size or sooner if there are clinical indications,” Dr. Friedman advised.

Protocols like these are constantly under review as more information becomes available. There are as yet no guidelines, and practice differs across institutions, according to the investigators summarizing this information.

None of the speakers had any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Feldstein LR et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-46.

2. Dufort EM et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med 2020;383:347-58.

One of the take-away messages from a review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is that clinicians treating this condition “need to be comfortable with uncertainty,” Melissa Hazen, MD, said at a synthesis of multiple published case series and personal experience summarized at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

She emphasized MIS-C patient care “requires flexibility,” and she advised clinicians managing these patients to open the lines of communication with the many specialists who often are required to deal with complications affecting an array of organ systems.

MIS-C might best be understood as the most serious manifestation of an immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection that ranges from transient mild symptoms to the life-threatening multiple organ involvement that characterizes this newly recognized threat. Although “most children who encounter this pathogen only develop mild disease,” the spectrum of the disease can move in a subset of patients to a “Kawasaki-like illness” without hemodynamic instability and then to MIS-C “with highly elevated systemic inflammatory markers and multiple organ involvement,” explained Dr. Hazen, an attending physician in the rheumatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

most of which have only recently reached publication, according to Dr. Hazen. In general, the description of the most common symptoms and their course has been relatively consistent.

In 186 cases of MIS-C collected in a study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 148 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 90 patients (48%) received vasoactive support, 37 (20%) received mechanical ventilation, and 4 (2%) died.1 The median age was 8 years (range, 3-13 years) in this study. The case definition was fever for at least 24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation, multisystem organ involvement, and evidence of COVID-19 infection. In this cohort of 186 children, 92% had gastrointestinal, 80% had cardiovascular, 76% had hematologic, and 70% had respiratory system involvement.

In a different series of 95 cases collected in New York State, 79 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 61 (62%) received vasoactive support, 10 (10%) received mechanical ventilation, 4 (4%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and 2 (2%) died. 2 Thirty-one percent patients were aged 0-5 years, 42% were 6-12 years, and 26% were 13-20 years of age. In that series, for which the case definition was elevation of two or more inflammatory markers, virologic evidence of COVID-19 infection, 80% had gastrointestinal system involvement, and 53% had evidence of myocarditis.

In both of these series, as well as others published and unpublished, the peak in MIS-C cases has occurred about 3 to 4 weeks after peak COVID-19 activity, according to Diana Lee, MD, a pediatrician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. This pattern, reported by others, was observed in New York State, where 230 cases of MIS-C were collected from the beginning of May until the end of June, which reflected this 3- to 4-week delay in peak incidence.

“This does seem to be a rare syndrome since this [group of] 230 cases is amongst the entire population of children in New York State. So, yes, we should be keeping this in mind in our differential, but we should not forget all the other reasons that children can have a fever,” she said.

Both Dr. Hazen and Dr. Lee cautioned that MIS-C, despite a general consistency among published studies, remains a moving target in regard to how it is being characterized. In a 2-day period in May, the CDC, the World Health Organization, and New York State all issued descriptions of MIS-C, employing compatible but slightly different terminology and diagnostic criteria. Many questions regarding optimal methods of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up remain unanswered.

Questions regarding the risk to the cardiovascular system, one of the organs most commonly affected in MIS-C, are among the most urgent. It is not now clear how best to monitor cardiovascular involvement, how to intervene, and how to follow patients in the postinfection period, according to Kevin G. Friedman, MD, a pediatrician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an attending physician in the department of cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“The most frequent complication we have seen is ventricular dysfunction, which occurs in about half of these patients,” he reported. “Usually it is in the mild to moderate range, but occasionally patients have an ejection fraction of less than 40%.”

Coronary abnormalities, typically in the form of dilations or small aneurysms, occur in 10%-20% of children with MIS-C, according to Dr. Friedman. Giant aneurysms have been reported.

“Some of these findings can progress including in both the acute phase and, particularly for the coronary aneurysms, in the subacute phase. We recommend echocardiograms and EKGs at diagnosis and at 1-2 weeks to recheck coronary size or sooner if there are clinical indications,” Dr. Friedman advised.

Protocols like these are constantly under review as more information becomes available. There are as yet no guidelines, and practice differs across institutions, according to the investigators summarizing this information.

None of the speakers had any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Feldstein LR et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-46.

2. Dufort EM et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med 2020;383:347-58.

One of the take-away messages from a review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is that clinicians treating this condition “need to be comfortable with uncertainty,” Melissa Hazen, MD, said at a synthesis of multiple published case series and personal experience summarized at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

She emphasized MIS-C patient care “requires flexibility,” and she advised clinicians managing these patients to open the lines of communication with the many specialists who often are required to deal with complications affecting an array of organ systems.

MIS-C might best be understood as the most serious manifestation of an immune-mediated response to COVID-19 infection that ranges from transient mild symptoms to the life-threatening multiple organ involvement that characterizes this newly recognized threat. Although “most children who encounter this pathogen only develop mild disease,” the spectrum of the disease can move in a subset of patients to a “Kawasaki-like illness” without hemodynamic instability and then to MIS-C “with highly elevated systemic inflammatory markers and multiple organ involvement,” explained Dr. Hazen, an attending physician in the rheumatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

most of which have only recently reached publication, according to Dr. Hazen. In general, the description of the most common symptoms and their course has been relatively consistent.

In 186 cases of MIS-C collected in a study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 148 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 90 patients (48%) received vasoactive support, 37 (20%) received mechanical ventilation, and 4 (2%) died.1 The median age was 8 years (range, 3-13 years) in this study. The case definition was fever for at least 24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation, multisystem organ involvement, and evidence of COVID-19 infection. In this cohort of 186 children, 92% had gastrointestinal, 80% had cardiovascular, 76% had hematologic, and 70% had respiratory system involvement.

In a different series of 95 cases collected in New York State, 79 (80%) were admitted to intensive care, 61 (62%) received vasoactive support, 10 (10%) received mechanical ventilation, 4 (4%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and 2 (2%) died. 2 Thirty-one percent patients were aged 0-5 years, 42% were 6-12 years, and 26% were 13-20 years of age. In that series, for which the case definition was elevation of two or more inflammatory markers, virologic evidence of COVID-19 infection, 80% had gastrointestinal system involvement, and 53% had evidence of myocarditis.

In both of these series, as well as others published and unpublished, the peak in MIS-C cases has occurred about 3 to 4 weeks after peak COVID-19 activity, according to Diana Lee, MD, a pediatrician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. This pattern, reported by others, was observed in New York State, where 230 cases of MIS-C were collected from the beginning of May until the end of June, which reflected this 3- to 4-week delay in peak incidence.

“This does seem to be a rare syndrome since this [group of] 230 cases is amongst the entire population of children in New York State. So, yes, we should be keeping this in mind in our differential, but we should not forget all the other reasons that children can have a fever,” she said.

Both Dr. Hazen and Dr. Lee cautioned that MIS-C, despite a general consistency among published studies, remains a moving target in regard to how it is being characterized. In a 2-day period in May, the CDC, the World Health Organization, and New York State all issued descriptions of MIS-C, employing compatible but slightly different terminology and diagnostic criteria. Many questions regarding optimal methods of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up remain unanswered.

Questions regarding the risk to the cardiovascular system, one of the organs most commonly affected in MIS-C, are among the most urgent. It is not now clear how best to monitor cardiovascular involvement, how to intervene, and how to follow patients in the postinfection period, according to Kevin G. Friedman, MD, a pediatrician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an attending physician in the department of cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“The most frequent complication we have seen is ventricular dysfunction, which occurs in about half of these patients,” he reported. “Usually it is in the mild to moderate range, but occasionally patients have an ejection fraction of less than 40%.”

Coronary abnormalities, typically in the form of dilations or small aneurysms, occur in 10%-20% of children with MIS-C, according to Dr. Friedman. Giant aneurysms have been reported.

“Some of these findings can progress including in both the acute phase and, particularly for the coronary aneurysms, in the subacute phase. We recommend echocardiograms and EKGs at diagnosis and at 1-2 weeks to recheck coronary size or sooner if there are clinical indications,” Dr. Friedman advised.

Protocols like these are constantly under review as more information becomes available. There are as yet no guidelines, and practice differs across institutions, according to the investigators summarizing this information.

None of the speakers had any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Feldstein LR et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-46.

2. Dufort EM et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med 2020;383:347-58.

FROM PHM20 VIRTUAL

Physician recruitment drops by 30% because of pandemic

the firm reported.

“Rather than having many practice opportunities to choose from, physicians now may have to compete to secure practice opportunities that meet their needs,” the authors wrote in Merritt Hawkins’ report on the impact of COVID-19.

Most of the report concerns physician recruitment from April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020. The data were mostly derived from searches that Merritt Hawkins conducted before the effects of the pandemic was fully felt.

Family medicine was again the most sought-after specialty, as it has been for the past 14 years. But demand for primary care doctors – including family physicians, internists, and pediatricians – leveled off, and average starting salaries for primary care doctors dropped during 2019-2020. In contrast, the number of searches conducted for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) increased by 54%, and their salaries increased slightly.

To explain the lackluster prospects for primary care before the pandemic, the authors cited research showing that patients were turning away from the traditional office visit model. At the same time, there was a rise in visits to NPs and PAs, including those in urgent care centers and retail clinics.

As a result of decreased demand for primary care physicians and the rising prevalence of telehealth, Merritt Hawkins expects primary care salaries to drop overall. With telehealth generating a larger portion of revenues, “it is uncertain whether primary care physicians will be able to sustain levels of reimbursement that were prevalent pre-COVID even at such time as the economy is improved and utilization increases,” the authors reported.

Demand for specialists was increasing prior to the COVID-19 crisis, partly as a result of the aging of the population. Seventy-eight percent of all searches were for medical specialists, compared with 67% 5 years ago. However, the pandemic has set back specialist searches. “Demand and compensation for specialists also will change as a result of COVID-19 in response to declines in the volume of medical procedures,” according to the authors.

In contrast, the recruitment of doctors who are on the front line of COVID-19 care is expected to increase. Among the fields anticipated to be in demand are emergency department specialists, infectious disease specialists, and pulmonology/critical care physicians. Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview that this trend is already happening and will accelerate as COVID-19 hot spots arise across the country.

Specialists in different fields received either higher or lower offers than during the previous year. Starting salaries for noninvasive cardiologists, for example, dropped 7.3%; gastroenterologists earned 7.7% less; and neurologists, 6.9% less. In contrast, orthopedic surgeons saw offers surge 16.7%; radiologists, 9.3%; and pulmonologists/critical care specialists, 7.7%.

Physicians were offered salaries plus bonuses in three-quarters of searches. Relative value unit–based production remained the most common basis for bonuses. Quality/value-based metrics were used in computing 64% of bonuses – up from 56% the previous year – but still determined only 11% of total physician compensation.

Pandemic outlook

Whereas health care helped drive the U.S. economy in 2018-2019, the pace of job growth in health care has decreased since March. As a result of the pandemic, health care spending in the United States declined by 18% in the first quarter of 2020. Physician practice revenue dropped by 55% during the first quarter, and many small and solo practices are still struggling.

In a 2018 Merritt Hawkins survey, 18% of physicians said they had used telehealth to treat patients. Because of the pandemic, that percentage jumped to 48% in April 2020. But telehealth hasn’t made up for the loss of patient revenue from in-office procedures, tests, and other services, and it still isn’t being reimbursed at the same level as in-office visits.

With practices under severe financial strain, the authors explained, “A majority of private practices have curtailed most physician recruiting activity since the virus emerged.”

In some states, many specialty practices have been adversely affected by the suspension of elective procedures, and specialty practices that rely on nonessential procedures are unlikely to recruit additional physicians.

One-third of practices could close

The survival of many private practices is now in question. “Based on the losses physician practices have sustained as a result of COVID-19, some markets could lose up to 35% or more of their most vulnerable group practices while a large percent of others will be acquired,” the authors wrote.

Hospitals and health systems will acquire the bulk of these practices, in many cases at fire-sale prices, Mr. Singleton predicted. This enormous shift from private practice to employment, he added, “will have as much to do with the [physician] income levels we’re going to see as the demand for the specialties themselves.”

Right now, he said, Merritt Hawkins is fielding a huge number of requests from doctors seeking employment, but there aren’t many jobs out there. “We haven’t seen an employer-friendly market like this since the 1970s,” he noted. “Before the pandemic, a physician might have had five to 10 jobs to choose from. Now it’s the opposite: We have one job, and 5 to 10 physicians are applying for it.”

Singleton believes the market will adjust by the second quarter of next year. Even if the pandemic worsens, he said, the system will have made the necessary corrections and adjustments “because we have to start seeing patients again, both in terms of demand and economics. So these doctors will be in demand again and will have work.”

Contingent employment

Although the COVID-related falloff in revenue has hit private practices the hardest, some employed physicians have also found themselves in a bind. According to a Merritt Hawkins/Physicians Foundation survey conducted in April, 21% of physicians said they had been furloughed or had taken a pay cut.

Mr. Singleton views this trend as part of hospitals’ reassessment of how they’re going to deal with labor going forward. To cope with utilization ebbs and flows in response to the virus, hospitals are now considering what the report calls a “contingent labor/flex staffing model.”

Under this type of arrangement, which some hospitals have already adopted, physicians may no longer work full time in a single setting, Mr. Singleton said. They may be asked to conduct telehealth visits on nights and weekends and work 20 hours a week in the clinic, or they may have shifts in multiple hospitals or clinics.

“You can make as much or more on a temporary basis as on a permanent basis,” he said. “But you have to be more flexible. You may have to travel or do a different scope of work, or work in different settings.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

the firm reported.

“Rather than having many practice opportunities to choose from, physicians now may have to compete to secure practice opportunities that meet their needs,” the authors wrote in Merritt Hawkins’ report on the impact of COVID-19.

Most of the report concerns physician recruitment from April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020. The data were mostly derived from searches that Merritt Hawkins conducted before the effects of the pandemic was fully felt.

Family medicine was again the most sought-after specialty, as it has been for the past 14 years. But demand for primary care doctors – including family physicians, internists, and pediatricians – leveled off, and average starting salaries for primary care doctors dropped during 2019-2020. In contrast, the number of searches conducted for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) increased by 54%, and their salaries increased slightly.

To explain the lackluster prospects for primary care before the pandemic, the authors cited research showing that patients were turning away from the traditional office visit model. At the same time, there was a rise in visits to NPs and PAs, including those in urgent care centers and retail clinics.

As a result of decreased demand for primary care physicians and the rising prevalence of telehealth, Merritt Hawkins expects primary care salaries to drop overall. With telehealth generating a larger portion of revenues, “it is uncertain whether primary care physicians will be able to sustain levels of reimbursement that were prevalent pre-COVID even at such time as the economy is improved and utilization increases,” the authors reported.

Demand for specialists was increasing prior to the COVID-19 crisis, partly as a result of the aging of the population. Seventy-eight percent of all searches were for medical specialists, compared with 67% 5 years ago. However, the pandemic has set back specialist searches. “Demand and compensation for specialists also will change as a result of COVID-19 in response to declines in the volume of medical procedures,” according to the authors.

In contrast, the recruitment of doctors who are on the front line of COVID-19 care is expected to increase. Among the fields anticipated to be in demand are emergency department specialists, infectious disease specialists, and pulmonology/critical care physicians. Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview that this trend is already happening and will accelerate as COVID-19 hot spots arise across the country.

Specialists in different fields received either higher or lower offers than during the previous year. Starting salaries for noninvasive cardiologists, for example, dropped 7.3%; gastroenterologists earned 7.7% less; and neurologists, 6.9% less. In contrast, orthopedic surgeons saw offers surge 16.7%; radiologists, 9.3%; and pulmonologists/critical care specialists, 7.7%.

Physicians were offered salaries plus bonuses in three-quarters of searches. Relative value unit–based production remained the most common basis for bonuses. Quality/value-based metrics were used in computing 64% of bonuses – up from 56% the previous year – but still determined only 11% of total physician compensation.

Pandemic outlook

Whereas health care helped drive the U.S. economy in 2018-2019, the pace of job growth in health care has decreased since March. As a result of the pandemic, health care spending in the United States declined by 18% in the first quarter of 2020. Physician practice revenue dropped by 55% during the first quarter, and many small and solo practices are still struggling.

In a 2018 Merritt Hawkins survey, 18% of physicians said they had used telehealth to treat patients. Because of the pandemic, that percentage jumped to 48% in April 2020. But telehealth hasn’t made up for the loss of patient revenue from in-office procedures, tests, and other services, and it still isn’t being reimbursed at the same level as in-office visits.

With practices under severe financial strain, the authors explained, “A majority of private practices have curtailed most physician recruiting activity since the virus emerged.”

In some states, many specialty practices have been adversely affected by the suspension of elective procedures, and specialty practices that rely on nonessential procedures are unlikely to recruit additional physicians.

One-third of practices could close

The survival of many private practices is now in question. “Based on the losses physician practices have sustained as a result of COVID-19, some markets could lose up to 35% or more of their most vulnerable group practices while a large percent of others will be acquired,” the authors wrote.

Hospitals and health systems will acquire the bulk of these practices, in many cases at fire-sale prices, Mr. Singleton predicted. This enormous shift from private practice to employment, he added, “will have as much to do with the [physician] income levels we’re going to see as the demand for the specialties themselves.”

Right now, he said, Merritt Hawkins is fielding a huge number of requests from doctors seeking employment, but there aren’t many jobs out there. “We haven’t seen an employer-friendly market like this since the 1970s,” he noted. “Before the pandemic, a physician might have had five to 10 jobs to choose from. Now it’s the opposite: We have one job, and 5 to 10 physicians are applying for it.”

Singleton believes the market will adjust by the second quarter of next year. Even if the pandemic worsens, he said, the system will have made the necessary corrections and adjustments “because we have to start seeing patients again, both in terms of demand and economics. So these doctors will be in demand again and will have work.”

Contingent employment

Although the COVID-related falloff in revenue has hit private practices the hardest, some employed physicians have also found themselves in a bind. According to a Merritt Hawkins/Physicians Foundation survey conducted in April, 21% of physicians said they had been furloughed or had taken a pay cut.

Mr. Singleton views this trend as part of hospitals’ reassessment of how they’re going to deal with labor going forward. To cope with utilization ebbs and flows in response to the virus, hospitals are now considering what the report calls a “contingent labor/flex staffing model.”

Under this type of arrangement, which some hospitals have already adopted, physicians may no longer work full time in a single setting, Mr. Singleton said. They may be asked to conduct telehealth visits on nights and weekends and work 20 hours a week in the clinic, or they may have shifts in multiple hospitals or clinics.

“You can make as much or more on a temporary basis as on a permanent basis,” he said. “But you have to be more flexible. You may have to travel or do a different scope of work, or work in different settings.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

the firm reported.

“Rather than having many practice opportunities to choose from, physicians now may have to compete to secure practice opportunities that meet their needs,” the authors wrote in Merritt Hawkins’ report on the impact of COVID-19.

Most of the report concerns physician recruitment from April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020. The data were mostly derived from searches that Merritt Hawkins conducted before the effects of the pandemic was fully felt.

Family medicine was again the most sought-after specialty, as it has been for the past 14 years. But demand for primary care doctors – including family physicians, internists, and pediatricians – leveled off, and average starting salaries for primary care doctors dropped during 2019-2020. In contrast, the number of searches conducted for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) increased by 54%, and their salaries increased slightly.

To explain the lackluster prospects for primary care before the pandemic, the authors cited research showing that patients were turning away from the traditional office visit model. At the same time, there was a rise in visits to NPs and PAs, including those in urgent care centers and retail clinics.

As a result of decreased demand for primary care physicians and the rising prevalence of telehealth, Merritt Hawkins expects primary care salaries to drop overall. With telehealth generating a larger portion of revenues, “it is uncertain whether primary care physicians will be able to sustain levels of reimbursement that were prevalent pre-COVID even at such time as the economy is improved and utilization increases,” the authors reported.

Demand for specialists was increasing prior to the COVID-19 crisis, partly as a result of the aging of the population. Seventy-eight percent of all searches were for medical specialists, compared with 67% 5 years ago. However, the pandemic has set back specialist searches. “Demand and compensation for specialists also will change as a result of COVID-19 in response to declines in the volume of medical procedures,” according to the authors.

In contrast, the recruitment of doctors who are on the front line of COVID-19 care is expected to increase. Among the fields anticipated to be in demand are emergency department specialists, infectious disease specialists, and pulmonology/critical care physicians. Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview that this trend is already happening and will accelerate as COVID-19 hot spots arise across the country.

Specialists in different fields received either higher or lower offers than during the previous year. Starting salaries for noninvasive cardiologists, for example, dropped 7.3%; gastroenterologists earned 7.7% less; and neurologists, 6.9% less. In contrast, orthopedic surgeons saw offers surge 16.7%; radiologists, 9.3%; and pulmonologists/critical care specialists, 7.7%.

Physicians were offered salaries plus bonuses in three-quarters of searches. Relative value unit–based production remained the most common basis for bonuses. Quality/value-based metrics were used in computing 64% of bonuses – up from 56% the previous year – but still determined only 11% of total physician compensation.

Pandemic outlook

Whereas health care helped drive the U.S. economy in 2018-2019, the pace of job growth in health care has decreased since March. As a result of the pandemic, health care spending in the United States declined by 18% in the first quarter of 2020. Physician practice revenue dropped by 55% during the first quarter, and many small and solo practices are still struggling.

In a 2018 Merritt Hawkins survey, 18% of physicians said they had used telehealth to treat patients. Because of the pandemic, that percentage jumped to 48% in April 2020. But telehealth hasn’t made up for the loss of patient revenue from in-office procedures, tests, and other services, and it still isn’t being reimbursed at the same level as in-office visits.

With practices under severe financial strain, the authors explained, “A majority of private practices have curtailed most physician recruiting activity since the virus emerged.”

In some states, many specialty practices have been adversely affected by the suspension of elective procedures, and specialty practices that rely on nonessential procedures are unlikely to recruit additional physicians.

One-third of practices could close

The survival of many private practices is now in question. “Based on the losses physician practices have sustained as a result of COVID-19, some markets could lose up to 35% or more of their most vulnerable group practices while a large percent of others will be acquired,” the authors wrote.

Hospitals and health systems will acquire the bulk of these practices, in many cases at fire-sale prices, Mr. Singleton predicted. This enormous shift from private practice to employment, he added, “will have as much to do with the [physician] income levels we’re going to see as the demand for the specialties themselves.”

Right now, he said, Merritt Hawkins is fielding a huge number of requests from doctors seeking employment, but there aren’t many jobs out there. “We haven’t seen an employer-friendly market like this since the 1970s,” he noted. “Before the pandemic, a physician might have had five to 10 jobs to choose from. Now it’s the opposite: We have one job, and 5 to 10 physicians are applying for it.”

Singleton believes the market will adjust by the second quarter of next year. Even if the pandemic worsens, he said, the system will have made the necessary corrections and adjustments “because we have to start seeing patients again, both in terms of demand and economics. So these doctors will be in demand again and will have work.”

Contingent employment

Although the COVID-related falloff in revenue has hit private practices the hardest, some employed physicians have also found themselves in a bind. According to a Merritt Hawkins/Physicians Foundation survey conducted in April, 21% of physicians said they had been furloughed or had taken a pay cut.

Mr. Singleton views this trend as part of hospitals’ reassessment of how they’re going to deal with labor going forward. To cope with utilization ebbs and flows in response to the virus, hospitals are now considering what the report calls a “contingent labor/flex staffing model.”

Under this type of arrangement, which some hospitals have already adopted, physicians may no longer work full time in a single setting, Mr. Singleton said. They may be asked to conduct telehealth visits on nights and weekends and work 20 hours a week in the clinic, or they may have shifts in multiple hospitals or clinics.

“You can make as much or more on a temporary basis as on a permanent basis,” he said. “But you have to be more flexible. You may have to travel or do a different scope of work, or work in different settings.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

NFL’s only physician player opts out of 2020 season over COVID

Canadian-born Duvernay-Tardif, right guard for the Kansas City Chiefs, announced on Twitter on July 24 what he called “one of the most difficult decisions I have had to make in my life.”

“There is no doubt in my mind the Chiefs’ medical staff have put together a strong plan to minimize the health risks associated with COVID-19, but some risks will remain,” he posted.

“Being at the frontline during this offseason has given me a different perspective on this pandemic and the stress it puts on individuals and our healthcare system. I cannot allow myself to potentially transmit the virus in our communities simply to play the sport that I love. If I am to take risks, I will do it caring for patients.”

According to CNN, Duvernay-Tardif, less than 3 months after helping the Chiefs win the Super Bowl in February, began working at a long-term care facility near Montreal in what he described as a “nursing role.”

Duvernay-Tardif wrote recently in an article for Sports Illustrated that he has not completed his residency and is not yet licensed to practice.

“My first day back in the hospital was April 24,” Duvernay-Tardif wrote. “I felt nervous the night before, but a good nervous, like before a game.”

Duvernay-Tardif has also served on the NFL Players’ Association COVID-19 task force, according to Yahoo News .

A spokesperson for Duvernay-Tardif told Medscape Medical News he was unavailable to comment about the announcement.

Starting His Dual Career

Duvernay-Tardif, 29, was drafted in the sixth round by the Chiefs in 2014.

According to Forbes , he spent 8 years (2010-2018) pursuing his medical degree while still playing college football for McGill University in Montreal. Duvernay-Tardif played offensive tackle for the Redmen and in his senior year (2013) won the Metras Trophy as most outstanding lineman in Canadian college football.

He explained in a previous Medscape interview how he managed his dual career; as a doctor he said he would like to focus on emergency medicine:

“I would say that at around 16-17 years of age, I was pretty convinced that medicine was for me,” he told Medscape.

“I was lucky that I didn’t have to do an undergrad program,” he continued. “In Canada, they have a fast-track program where instead of doing a full undergrad before getting into medical school, you can do a 1-year program where you can do all your physiology and biology classes all together.

“I had the chance to get into that program, and that’s how I was able to manage football and medicine at the same time. There’s no way I could have finished my med school doing part-time med school like I did for the past 4 years.”

ESPN explained the opt-out option: “According to an agreement approved by both the league and the union on [July 24], players considered high risk for COVID-19 can earn $350,000 and an accrued NFL season if they choose to opt out of the 2020 season. Players without risk can earn $150,000 for opting out. Duvernay-Tardif was scheduled to make $2.75 million this season.”

The danger of COVID-19 in professional sports has already been seen in Major League Baseball.

According to USA Today, the Miami Marlins have at least 14 players and staff who have tested positive for COVID-19, and major league baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred must decide whether to further delay the shortened season, cancel it, or allow it to continue.

MLB postponed the Marlins’ home opener July 27 against the Baltimore Orioles as well as the New York Yankees game in Philadelphia against the Phillies.

COVID-19 also shut down professional, college, high school, and recreational sports throughout much of the country beginning in March.

Medicine, Football Intersect

In the previous Medscape interview, Duvernay-Tardif talked about how medicine influenced his football career.

“For me, medicine was really helpful in the sense that I was better able to build a routine and question what works for me and what doesn’t. It gave me the ability to structure my work in order to optimize my time and to make sure that it’s pertinent.

“Another thing is the psychology and the sports psychology. I think there’s a little bit of a stigma around mental health issues in professional sports and everywhere, actually. I think because of medicine, I was more willing to question myself and more willing to use different tools in order to be a better football player.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Canadian-born Duvernay-Tardif, right guard for the Kansas City Chiefs, announced on Twitter on July 24 what he called “one of the most difficult decisions I have had to make in my life.”

“There is no doubt in my mind the Chiefs’ medical staff have put together a strong plan to minimize the health risks associated with COVID-19, but some risks will remain,” he posted.

“Being at the frontline during this offseason has given me a different perspective on this pandemic and the stress it puts on individuals and our healthcare system. I cannot allow myself to potentially transmit the virus in our communities simply to play the sport that I love. If I am to take risks, I will do it caring for patients.”

According to CNN, Duvernay-Tardif, less than 3 months after helping the Chiefs win the Super Bowl in February, began working at a long-term care facility near Montreal in what he described as a “nursing role.”

Duvernay-Tardif wrote recently in an article for Sports Illustrated that he has not completed his residency and is not yet licensed to practice.

“My first day back in the hospital was April 24,” Duvernay-Tardif wrote. “I felt nervous the night before, but a good nervous, like before a game.”

Duvernay-Tardif has also served on the NFL Players’ Association COVID-19 task force, according to Yahoo News .

A spokesperson for Duvernay-Tardif told Medscape Medical News he was unavailable to comment about the announcement.

Starting His Dual Career

Duvernay-Tardif, 29, was drafted in the sixth round by the Chiefs in 2014.

According to Forbes , he spent 8 years (2010-2018) pursuing his medical degree while still playing college football for McGill University in Montreal. Duvernay-Tardif played offensive tackle for the Redmen and in his senior year (2013) won the Metras Trophy as most outstanding lineman in Canadian college football.

He explained in a previous Medscape interview how he managed his dual career; as a doctor he said he would like to focus on emergency medicine:

“I would say that at around 16-17 years of age, I was pretty convinced that medicine was for me,” he told Medscape.

“I was lucky that I didn’t have to do an undergrad program,” he continued. “In Canada, they have a fast-track program where instead of doing a full undergrad before getting into medical school, you can do a 1-year program where you can do all your physiology and biology classes all together.

“I had the chance to get into that program, and that’s how I was able to manage football and medicine at the same time. There’s no way I could have finished my med school doing part-time med school like I did for the past 4 years.”

ESPN explained the opt-out option: “According to an agreement approved by both the league and the union on [July 24], players considered high risk for COVID-19 can earn $350,000 and an accrued NFL season if they choose to opt out of the 2020 season. Players without risk can earn $150,000 for opting out. Duvernay-Tardif was scheduled to make $2.75 million this season.”

The danger of COVID-19 in professional sports has already been seen in Major League Baseball.

According to USA Today, the Miami Marlins have at least 14 players and staff who have tested positive for COVID-19, and major league baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred must decide whether to further delay the shortened season, cancel it, or allow it to continue.

MLB postponed the Marlins’ home opener July 27 against the Baltimore Orioles as well as the New York Yankees game in Philadelphia against the Phillies.

COVID-19 also shut down professional, college, high school, and recreational sports throughout much of the country beginning in March.

Medicine, Football Intersect

In the previous Medscape interview, Duvernay-Tardif talked about how medicine influenced his football career.

“For me, medicine was really helpful in the sense that I was better able to build a routine and question what works for me and what doesn’t. It gave me the ability to structure my work in order to optimize my time and to make sure that it’s pertinent.

“Another thing is the psychology and the sports psychology. I think there’s a little bit of a stigma around mental health issues in professional sports and everywhere, actually. I think because of medicine, I was more willing to question myself and more willing to use different tools in order to be a better football player.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Canadian-born Duvernay-Tardif, right guard for the Kansas City Chiefs, announced on Twitter on July 24 what he called “one of the most difficult decisions I have had to make in my life.”

“There is no doubt in my mind the Chiefs’ medical staff have put together a strong plan to minimize the health risks associated with COVID-19, but some risks will remain,” he posted.

“Being at the frontline during this offseason has given me a different perspective on this pandemic and the stress it puts on individuals and our healthcare system. I cannot allow myself to potentially transmit the virus in our communities simply to play the sport that I love. If I am to take risks, I will do it caring for patients.”

According to CNN, Duvernay-Tardif, less than 3 months after helping the Chiefs win the Super Bowl in February, began working at a long-term care facility near Montreal in what he described as a “nursing role.”

Duvernay-Tardif wrote recently in an article for Sports Illustrated that he has not completed his residency and is not yet licensed to practice.

“My first day back in the hospital was April 24,” Duvernay-Tardif wrote. “I felt nervous the night before, but a good nervous, like before a game.”

Duvernay-Tardif has also served on the NFL Players’ Association COVID-19 task force, according to Yahoo News .

A spokesperson for Duvernay-Tardif told Medscape Medical News he was unavailable to comment about the announcement.

Starting His Dual Career

Duvernay-Tardif, 29, was drafted in the sixth round by the Chiefs in 2014.

According to Forbes , he spent 8 years (2010-2018) pursuing his medical degree while still playing college football for McGill University in Montreal. Duvernay-Tardif played offensive tackle for the Redmen and in his senior year (2013) won the Metras Trophy as most outstanding lineman in Canadian college football.

He explained in a previous Medscape interview how he managed his dual career; as a doctor he said he would like to focus on emergency medicine:

“I would say that at around 16-17 years of age, I was pretty convinced that medicine was for me,” he told Medscape.

“I was lucky that I didn’t have to do an undergrad program,” he continued. “In Canada, they have a fast-track program where instead of doing a full undergrad before getting into medical school, you can do a 1-year program where you can do all your physiology and biology classes all together.

“I had the chance to get into that program, and that’s how I was able to manage football and medicine at the same time. There’s no way I could have finished my med school doing part-time med school like I did for the past 4 years.”

ESPN explained the opt-out option: “According to an agreement approved by both the league and the union on [July 24], players considered high risk for COVID-19 can earn $350,000 and an accrued NFL season if they choose to opt out of the 2020 season. Players without risk can earn $150,000 for opting out. Duvernay-Tardif was scheduled to make $2.75 million this season.”

The danger of COVID-19 in professional sports has already been seen in Major League Baseball.

According to USA Today, the Miami Marlins have at least 14 players and staff who have tested positive for COVID-19, and major league baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred must decide whether to further delay the shortened season, cancel it, or allow it to continue.

MLB postponed the Marlins’ home opener July 27 against the Baltimore Orioles as well as the New York Yankees game in Philadelphia against the Phillies.

COVID-19 also shut down professional, college, high school, and recreational sports throughout much of the country beginning in March.

Medicine, Football Intersect

In the previous Medscape interview, Duvernay-Tardif talked about how medicine influenced his football career.

“For me, medicine was really helpful in the sense that I was better able to build a routine and question what works for me and what doesn’t. It gave me the ability to structure my work in order to optimize my time and to make sure that it’s pertinent.

“Another thing is the psychology and the sports psychology. I think there’s a little bit of a stigma around mental health issues in professional sports and everywhere, actually. I think because of medicine, I was more willing to question myself and more willing to use different tools in order to be a better football player.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Diary of a rheumatologist who briefly became a COVID hospitalist

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

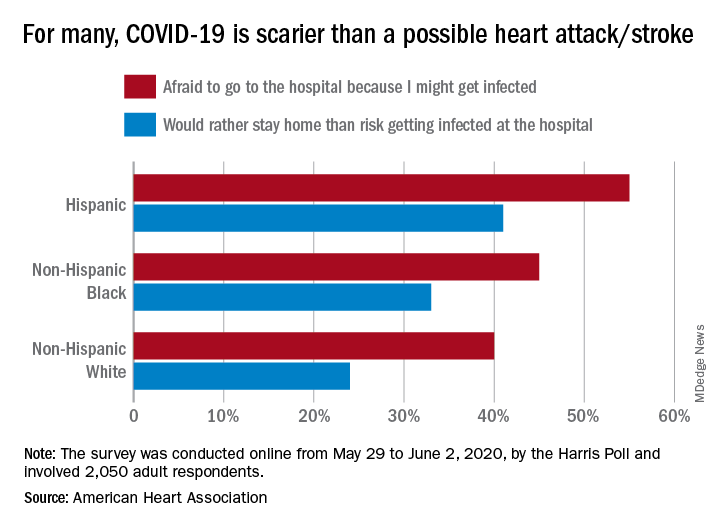

COVID-19 fears would keep most Hispanics with stroke, MI symptoms home

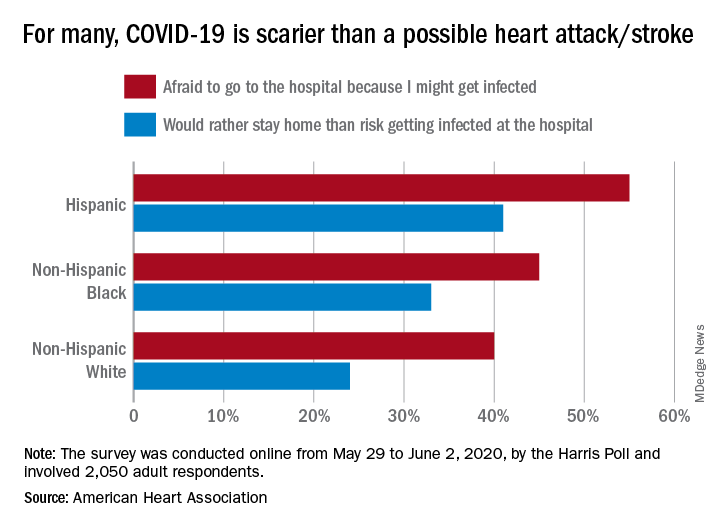

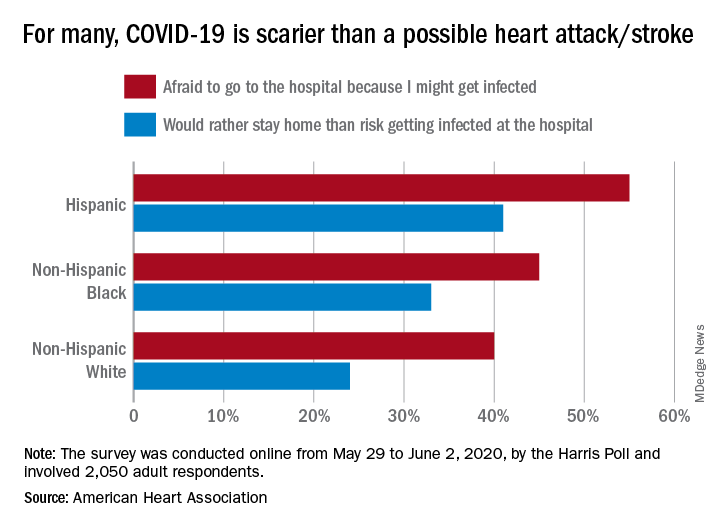

More than half of Hispanic adults would be afraid to go to a hospital for a possible heart attack or stroke because they might get infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a new survey from the American Heart Association.

Compared with Hispanic respondents, 55% of whom said they feared COVID-19, significantly fewer Blacks (45%) and Whites (40%) would be scared to go to the hospital if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke, the AHA said based on the survey of 2,050 adults, which was conducted May 29 to June 2, 2020, by the Harris Poll.

Hispanics also were significantly more likely to stay home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke (41%), rather than risk getting infected at the hospital, than were Blacks (33%), who were significantly more likely than Whites (24%) to stay home, the AHA reported.

White respondents, on the other hand, were the most likely to believe (89%) that a hospital would give them the same quality of care provided to everyone else. Hispanics and Blacks had significantly lower rates, at 78% and 74%, respectively, the AHA noted.