User login

Clinical Endocrinology News is an independent news source that provides endocrinologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the endocrinologist's practice. Specialty topics include Diabetes, Lipid & Metabolic Disorders Menopause, Obesity, Osteoporosis, Pediatric Endocrinology, Pituitary, Thyroid & Adrenal Disorders, and Reproductive Endocrinology. Featured content includes Commentaries, Implementin Health Reform, Law & Medicine, and In the Loop, the blog of Clinical Endocrinology News. Clinical Endocrinology News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

addict

addicted

addicting

addiction

adult sites

alcohol

antibody

ass

attorney

audit

auditor

babies

babpa

baby

ban

banned

banning

best

bisexual

bitch

bleach

blog

blow job

bondage

boobs

booty

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cheap

cheapest

class action

cocaine

cock

counterfeit drug

crack

crap

crime

criminal

cunt

curable

cure

dangerous

dangers

dead

deadly

death

defend

defended

depedent

dependence

dependent

detergent

dick

die

dildo

drug abuse

drug recall

dying

fag

fake

fatal

fatalities

fatality

free

fuck

gangs

gingivitis

guns

hardcore

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

home remedies

homo

horny

hypersensitivity

hypoglycemia treatment

illegal drug use

illegal use of prescription

incest

infant

infants

job

ketoacidosis

kill

killer

killing

kinky

law suit

lawsuit

lawyer

lesbian

marijuana

medicine for hypoglycemia

murder

naked

natural

newborn

nigger

noise

nude

nudity

orgy

over the counter

overdosage

overdose

overdosed

overdosing

penis

pimp

pistol

porn

porno

pornographic

pornography

prison

profanity

purchase

purchasing

pussy

queer

rape

rapist

recall

recreational drug

rob

robberies

sale

sales

sex

sexual

shit

shoot

slut

slutty

stole

stolen

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

supply company

theft

thief

thieves

tit

toddler

toddlers

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treating dka

treating hypoglycemia

treatment for hypoglycemia

vagina

violence

whore

withdrawal

without prescription

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Five ways docs may qualify for discounts on medical malpractice premiums

Getting a better deal might simply mean taking advantage of incentives and discounts your insurer may already offer. These include claims-free, new-to-practice, and working part-time discounts.

However, if you decide to shop around, keep in mind that discounts are just one factor that can affect your premium price – insurers look at your specialty, location, and claims history.

One of the most common ways physicians can earn discounts is by participating in risk management programs. With this type of program, physicians evaluate elements of their practice and documentation practices and identify areas that might leave them at risk for a lawsuit. While they save money, physician risk management programs also are designed to reduce malpractice claims, which ultimately minimizes the potential for bigger financial losses, insurance experts say.

“It’s a win-win situation when liability insurers and physicians work together to minimize risk, and it’s a win for patients,” said Gary Price, MD, president of The Physicians Foundation.

Doctors in private practice or employed by small hospitals that are not self-insured can qualify for these discounts, said David Zetter, president of Zetter HealthCare Management Consultants.

“I do a lot of work with medical malpractice companies trying to find clients policies. All the carriers are transparent about what physicians have to do to lower their premiums. Physicians can receive the discounts if they follow through and meet the insurer’s requirements,” said Mr. Zetter.

State insurance departments regulate medical malpractice insurance, including the premium credits insurers offer. Most states cap discounts at 25%, but some go as high as 70%, according to The Doctors Company, a national physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.

Insurers typically offer doctors several ways to earn discounts. The size of the discount also can depend on whether a doctor is new to a practice, remains claims free, or takes risk management courses.

In addition to the premium discount, some online risk management classes and webinars are eligible for CME credits.

“The credits can add up and they can be used for recertification or relicensure,” said Susan Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company.

Here are five ways you may qualify for discounts with your insurer.

1. Make use of discounts available to new doctors

Doctors can earn hefty discounts on their premiums when they are no longer interns or residents and start practicing medicine. The Doctors Company usually gives a 50% discount on member premiums the first year they’re in practice and a 25% discount credit in their second year. The discounts end after that.

Other insurance carriers offer similar discounts to doctors starting to practice medicine. The deepest one is offered in the first year (at least 50%) and a smaller one (20%-25%) the second year, according to medical malpractice brokers.

“The new-to-practice discount is based solely on when the physician left their formal training to begin their practice for the first time; it is not based on claim-free history,” explained Mr. Zetter.

This is a very common discount used by different insurer carriers, said Dr. Price. “New physicians don’t have the same amount of risk of a lawsuit when they’re starting out. It’s unlikely they will have a claim and most liability actions have a 2-year time limit from the date of injury to be filed.”

2. Take advantage of being claims free

If you’ve been claims free for at least a few years, you may be eligible for a large discount.

“Doctors without claims are a better risk. Once a doctor has one claim, they’re likely to have a second, which the research shows,” said Mr. Zetter.

The most common credit The Doctors Company offers is 3 years of being claim free – this earns doctors up to 25%, he said. Mr. Zetter explained that the criteria and size of The Doctors Company credit may depend on the state where physicians practice.

“We allowed insurance carriers that we acquired to continue with their own claim-free discount program such as Florida’s First Professionals Insurance Company we acquired in 2011,” he said.

Doctors with other medical malpractice insurers may also be eligible for a credit up to 25%. In some instances, they may have to be claims free for 5 or 10 years, say insurance experts.

It pays to shop around before purchasing insurance.

3. If you work part time, make sure your premium reflects that

Physicians who see patients part time can receive up to a 75% discount on their medical liability insurance premiums.

The discounts are based on the hours the physician works per week. The fewer hours worked, the larger the discount. This type of discount does not vary by specialty.

According to The Doctors Company, working 10 hours or less per week may entitle doctors to a 75% discount; working 11-20 hours per week may entitle them to a 50% discount, and working 21-30 hours per week may entitle them to a 25% discount. If you are in this situation, it pays to ask your insurer if there is a discount available to you.

4. Look into your professional medical society insurance company

“I would look at your state medical association [or] state specialty society and talk to your colleagues to learn what premiums they’re paying and about any discounts they’re getting,” advised Mr. Zetter.

Some state medical societies have formed their own liability companies and offer lower premiums to their members because “they’re organized and managed by doctors, which makes their premiums more competitive,” Dr. Price said.

Other state medical societies endorse specific insurance carriers and offer their members a 5% discount for enrolling with them.

5. Enroll in a risk management program

Most insurers offer online educational activities designed to improve patient safety and reduce the risk of a lawsuit. Physicians may be eligible for both premium discounts and CME credits.

Medical Liability Mutual Insurance Company, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, operates in New York and offers physicians a premium discount of up to 5%, CME credit, and maintenance of certification credit for successfully completing its risk management program every other year.

ProAssurance members nationwide can earn 5% in premium discounts if they complete a 2-hour video series called “Back to Basics: Loss Prevention and Navigating Everyday Risks: Using Data to Drive Change.”

They can earn one credit for completing each webinar on topics such as “Medication Management: Minimizing Errors and Improving Safety” and “Opioid Prescribing: Keeping Patients Safe.”

MagMutual offers its insured physicians 1 CME credit for completing their specialty’s risk assessment and courses, which may be applied toward their premium discounts.

The Doctors Company offers its members a 5% premium discount if they complete 4 CME credits. One of its most popular courses is “How To Get Rid of a Difficult Patient.”

“Busy residents like the shorter case studies worth one-quarter credit that they can complete in 15 minutes,” said Ms. Boisvert.

“This is a good bargain from the physician’s standpoint and the fact that risk management education is offered online makes it a lot easier than going to a seminar in person,” said Dr. Price.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Getting a better deal might simply mean taking advantage of incentives and discounts your insurer may already offer. These include claims-free, new-to-practice, and working part-time discounts.

However, if you decide to shop around, keep in mind that discounts are just one factor that can affect your premium price – insurers look at your specialty, location, and claims history.

One of the most common ways physicians can earn discounts is by participating in risk management programs. With this type of program, physicians evaluate elements of their practice and documentation practices and identify areas that might leave them at risk for a lawsuit. While they save money, physician risk management programs also are designed to reduce malpractice claims, which ultimately minimizes the potential for bigger financial losses, insurance experts say.

“It’s a win-win situation when liability insurers and physicians work together to minimize risk, and it’s a win for patients,” said Gary Price, MD, president of The Physicians Foundation.

Doctors in private practice or employed by small hospitals that are not self-insured can qualify for these discounts, said David Zetter, president of Zetter HealthCare Management Consultants.

“I do a lot of work with medical malpractice companies trying to find clients policies. All the carriers are transparent about what physicians have to do to lower their premiums. Physicians can receive the discounts if they follow through and meet the insurer’s requirements,” said Mr. Zetter.

State insurance departments regulate medical malpractice insurance, including the premium credits insurers offer. Most states cap discounts at 25%, but some go as high as 70%, according to The Doctors Company, a national physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.

Insurers typically offer doctors several ways to earn discounts. The size of the discount also can depend on whether a doctor is new to a practice, remains claims free, or takes risk management courses.

In addition to the premium discount, some online risk management classes and webinars are eligible for CME credits.

“The credits can add up and they can be used for recertification or relicensure,” said Susan Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company.

Here are five ways you may qualify for discounts with your insurer.

1. Make use of discounts available to new doctors

Doctors can earn hefty discounts on their premiums when they are no longer interns or residents and start practicing medicine. The Doctors Company usually gives a 50% discount on member premiums the first year they’re in practice and a 25% discount credit in their second year. The discounts end after that.

Other insurance carriers offer similar discounts to doctors starting to practice medicine. The deepest one is offered in the first year (at least 50%) and a smaller one (20%-25%) the second year, according to medical malpractice brokers.

“The new-to-practice discount is based solely on when the physician left their formal training to begin their practice for the first time; it is not based on claim-free history,” explained Mr. Zetter.

This is a very common discount used by different insurer carriers, said Dr. Price. “New physicians don’t have the same amount of risk of a lawsuit when they’re starting out. It’s unlikely they will have a claim and most liability actions have a 2-year time limit from the date of injury to be filed.”

2. Take advantage of being claims free

If you’ve been claims free for at least a few years, you may be eligible for a large discount.

“Doctors without claims are a better risk. Once a doctor has one claim, they’re likely to have a second, which the research shows,” said Mr. Zetter.

The most common credit The Doctors Company offers is 3 years of being claim free – this earns doctors up to 25%, he said. Mr. Zetter explained that the criteria and size of The Doctors Company credit may depend on the state where physicians practice.

“We allowed insurance carriers that we acquired to continue with their own claim-free discount program such as Florida’s First Professionals Insurance Company we acquired in 2011,” he said.

Doctors with other medical malpractice insurers may also be eligible for a credit up to 25%. In some instances, they may have to be claims free for 5 or 10 years, say insurance experts.

It pays to shop around before purchasing insurance.

3. If you work part time, make sure your premium reflects that

Physicians who see patients part time can receive up to a 75% discount on their medical liability insurance premiums.

The discounts are based on the hours the physician works per week. The fewer hours worked, the larger the discount. This type of discount does not vary by specialty.

According to The Doctors Company, working 10 hours or less per week may entitle doctors to a 75% discount; working 11-20 hours per week may entitle them to a 50% discount, and working 21-30 hours per week may entitle them to a 25% discount. If you are in this situation, it pays to ask your insurer if there is a discount available to you.

4. Look into your professional medical society insurance company

“I would look at your state medical association [or] state specialty society and talk to your colleagues to learn what premiums they’re paying and about any discounts they’re getting,” advised Mr. Zetter.

Some state medical societies have formed their own liability companies and offer lower premiums to their members because “they’re organized and managed by doctors, which makes their premiums more competitive,” Dr. Price said.

Other state medical societies endorse specific insurance carriers and offer their members a 5% discount for enrolling with them.

5. Enroll in a risk management program

Most insurers offer online educational activities designed to improve patient safety and reduce the risk of a lawsuit. Physicians may be eligible for both premium discounts and CME credits.

Medical Liability Mutual Insurance Company, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, operates in New York and offers physicians a premium discount of up to 5%, CME credit, and maintenance of certification credit for successfully completing its risk management program every other year.

ProAssurance members nationwide can earn 5% in premium discounts if they complete a 2-hour video series called “Back to Basics: Loss Prevention and Navigating Everyday Risks: Using Data to Drive Change.”

They can earn one credit for completing each webinar on topics such as “Medication Management: Minimizing Errors and Improving Safety” and “Opioid Prescribing: Keeping Patients Safe.”

MagMutual offers its insured physicians 1 CME credit for completing their specialty’s risk assessment and courses, which may be applied toward their premium discounts.

The Doctors Company offers its members a 5% premium discount if they complete 4 CME credits. One of its most popular courses is “How To Get Rid of a Difficult Patient.”

“Busy residents like the shorter case studies worth one-quarter credit that they can complete in 15 minutes,” said Ms. Boisvert.

“This is a good bargain from the physician’s standpoint and the fact that risk management education is offered online makes it a lot easier than going to a seminar in person,” said Dr. Price.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Getting a better deal might simply mean taking advantage of incentives and discounts your insurer may already offer. These include claims-free, new-to-practice, and working part-time discounts.

However, if you decide to shop around, keep in mind that discounts are just one factor that can affect your premium price – insurers look at your specialty, location, and claims history.

One of the most common ways physicians can earn discounts is by participating in risk management programs. With this type of program, physicians evaluate elements of their practice and documentation practices and identify areas that might leave them at risk for a lawsuit. While they save money, physician risk management programs also are designed to reduce malpractice claims, which ultimately minimizes the potential for bigger financial losses, insurance experts say.

“It’s a win-win situation when liability insurers and physicians work together to minimize risk, and it’s a win for patients,” said Gary Price, MD, president of The Physicians Foundation.

Doctors in private practice or employed by small hospitals that are not self-insured can qualify for these discounts, said David Zetter, president of Zetter HealthCare Management Consultants.

“I do a lot of work with medical malpractice companies trying to find clients policies. All the carriers are transparent about what physicians have to do to lower their premiums. Physicians can receive the discounts if they follow through and meet the insurer’s requirements,” said Mr. Zetter.

State insurance departments regulate medical malpractice insurance, including the premium credits insurers offer. Most states cap discounts at 25%, but some go as high as 70%, according to The Doctors Company, a national physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.

Insurers typically offer doctors several ways to earn discounts. The size of the discount also can depend on whether a doctor is new to a practice, remains claims free, or takes risk management courses.

In addition to the premium discount, some online risk management classes and webinars are eligible for CME credits.

“The credits can add up and they can be used for recertification or relicensure,” said Susan Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company.

Here are five ways you may qualify for discounts with your insurer.

1. Make use of discounts available to new doctors

Doctors can earn hefty discounts on their premiums when they are no longer interns or residents and start practicing medicine. The Doctors Company usually gives a 50% discount on member premiums the first year they’re in practice and a 25% discount credit in their second year. The discounts end after that.

Other insurance carriers offer similar discounts to doctors starting to practice medicine. The deepest one is offered in the first year (at least 50%) and a smaller one (20%-25%) the second year, according to medical malpractice brokers.

“The new-to-practice discount is based solely on when the physician left their formal training to begin their practice for the first time; it is not based on claim-free history,” explained Mr. Zetter.

This is a very common discount used by different insurer carriers, said Dr. Price. “New physicians don’t have the same amount of risk of a lawsuit when they’re starting out. It’s unlikely they will have a claim and most liability actions have a 2-year time limit from the date of injury to be filed.”

2. Take advantage of being claims free

If you’ve been claims free for at least a few years, you may be eligible for a large discount.

“Doctors without claims are a better risk. Once a doctor has one claim, they’re likely to have a second, which the research shows,” said Mr. Zetter.

The most common credit The Doctors Company offers is 3 years of being claim free – this earns doctors up to 25%, he said. Mr. Zetter explained that the criteria and size of The Doctors Company credit may depend on the state where physicians practice.

“We allowed insurance carriers that we acquired to continue with their own claim-free discount program such as Florida’s First Professionals Insurance Company we acquired in 2011,” he said.

Doctors with other medical malpractice insurers may also be eligible for a credit up to 25%. In some instances, they may have to be claims free for 5 or 10 years, say insurance experts.

It pays to shop around before purchasing insurance.

3. If you work part time, make sure your premium reflects that

Physicians who see patients part time can receive up to a 75% discount on their medical liability insurance premiums.

The discounts are based on the hours the physician works per week. The fewer hours worked, the larger the discount. This type of discount does not vary by specialty.

According to The Doctors Company, working 10 hours or less per week may entitle doctors to a 75% discount; working 11-20 hours per week may entitle them to a 50% discount, and working 21-30 hours per week may entitle them to a 25% discount. If you are in this situation, it pays to ask your insurer if there is a discount available to you.

4. Look into your professional medical society insurance company

“I would look at your state medical association [or] state specialty society and talk to your colleagues to learn what premiums they’re paying and about any discounts they’re getting,” advised Mr. Zetter.

Some state medical societies have formed their own liability companies and offer lower premiums to their members because “they’re organized and managed by doctors, which makes their premiums more competitive,” Dr. Price said.

Other state medical societies endorse specific insurance carriers and offer their members a 5% discount for enrolling with them.

5. Enroll in a risk management program

Most insurers offer online educational activities designed to improve patient safety and reduce the risk of a lawsuit. Physicians may be eligible for both premium discounts and CME credits.

Medical Liability Mutual Insurance Company, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, operates in New York and offers physicians a premium discount of up to 5%, CME credit, and maintenance of certification credit for successfully completing its risk management program every other year.

ProAssurance members nationwide can earn 5% in premium discounts if they complete a 2-hour video series called “Back to Basics: Loss Prevention and Navigating Everyday Risks: Using Data to Drive Change.”

They can earn one credit for completing each webinar on topics such as “Medication Management: Minimizing Errors and Improving Safety” and “Opioid Prescribing: Keeping Patients Safe.”

MagMutual offers its insured physicians 1 CME credit for completing their specialty’s risk assessment and courses, which may be applied toward their premium discounts.

The Doctors Company offers its members a 5% premium discount if they complete 4 CME credits. One of its most popular courses is “How To Get Rid of a Difficult Patient.”

“Busy residents like the shorter case studies worth one-quarter credit that they can complete in 15 minutes,” said Ms. Boisvert.

“This is a good bargain from the physician’s standpoint and the fact that risk management education is offered online makes it a lot easier than going to a seminar in person,” said Dr. Price.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boys may carry the weight, or overweight, of adults’ infertility

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

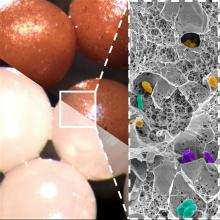

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

New protocol could cut fasting period to detect insulinomas

SEATTLE – , therefore yielding significant hospital cost savings, new data suggest.

Insulinomas are small, rare types of pancreatic tumors that are benign but secrete excess insulin, leading to hypoglycemia. More than 99% of people with insulinomas develop hypoglycemia within 72 hours, hence, the use of a 72-hour fast to detect these tumors.

But most people who are evaluated for hypoglycemia do not have an insulinoma and fasting in hospital for 3 days is burdensome and costly.

As part of a quality improvement project, Cleveland Clinic endocrinology fellow Michelle D. Lundholm, MD, and colleagues modified their hospital’s protocol to include measurement of beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), a marker of insulin suppression, every 12 hours with a cutoff of ≥ 2.7mmol/L for stopping the fast if hypoglycemia (venous glucose ≤ 45mg/dL) hasn’t occurred. This intervention cut in half the number of patients who needed to fast for the full 72 hours, without missing any insulinomas.

“We are excited to share how a relatively simple adjustment to our protocol allowed us to successfully reduce the burden of fasting on patients and more effectively utilize hospital resources. We hope that this encourages other centers to consider doing the same,” Dr. Lundholm said in an interview.

“These data support a 48-hour fast. The literature supports that’s sufficient to detect 95% of insulinomas. ... But, given our small insulinoma cohort, we are looking forward to learning from other studies,” she added.

Dr. Lundholm presented the late-breaking oral abstract at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

Asked to comment, session moderator Jenna Sarvaideo, MD, said: “We’re often steeped in tradition. That’s why this abstract and this quality improvement project is so exciting to me because it challenges the history. … and I think it’s ultimately helping patients.”

Dr. Sarvaideo, of Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center, Milwaukee, noted that, typically, although the fast will be stopped before 72 hours if the patient develops hypoglycemia, “often they don’t, so we keep going on and on. If we just paid more attention to the beta-hydroxybutyrate, I think that would be practice changing.”

She added that more data would be optimal, given that there were under 100 patients in the study, “but I do think that devising protocols is … very much still at the hands of the endocrinologists. I think that this work could make groups reevaluate their protocol and change it, maybe even with a small dataset and then move on from there and see what they see.”

Indeed, Dr. Lundholm pointed out that some institutions, such as the Mayo Clinic, already include 6-hour BHB measurements (along with glucose and insulin) in their protocols.

“For any institution that already draws regular BHB levels like this, it would be very easy to implement a new stopping criterion without adding any additional costs,” she said in an interview.

All insulinomas became apparent in less than 48 hours

The first report to look at the value of testing BHB at regular intervals was published by the Mayo Clinic in 2005 after they noticed patients without insulinoma were complaining of ketosis symptoms such as foul breath and digestive problems toward the end of the fast.

However, although BHB testing is used today as part of the evaluation, it’s typically only drawn at the start of the protocol and again at the time of hypoglycemia or at the end of 72 hours because more frequent values hadn’t been thought to be useful for guiding clinical management, Dr. Lundholm explained.

Between January 2018 and June 2020, Dr. Lundholm and colleagues followed 34 Cleveland Clinic patients who completed the usual 72-hour fast protocol. Overall, 71% were female, and 26% had undergone prior bariatric surgery procedures. Eleven (32%) developed hypoglycemia and stopped fasting. The other 23 (68%) fasted for the full 72 hours.

Dr. Lundholm and colleagues determined that the fast could have ended earlier in 35% of patients based on an elevated BHB without missing any insulinomas.

And so, in June 2020 the group revised their protocol to include the BHB ≥ 2.7mmol/L stopping criterion. Of the 30 patients evaluated from June 2020 to January 2023, 87% were female and 17% had undergone a bariatric procedure.

Here, 15 (50%) reached a BHB ≥ 2.7mmol/L and ended their fast at an average of 43.8 hours. Another seven (23%) ended the fast after developing hypoglycemia. Just eight patients (27%) fasted for the full 72 hours.

Overall, this resulted in approximately 376 fewer cumulative hours of inpatient admission than if patients had fasted for the full time.

Of the 64 patients who have completed the fasting protocol since 2018, seven (11%) who did have an insulinoma developed hypoglycemia within 48 hours and with a BHB < 2.7 mmol/L (median, 0.15).

Advantages: cost, adherence

A day in a general medicine bed at Cleveland Clinic was quoted as costing $2,420, based on publicly available information as of Jan. 1, 2023. “If half of patients leave 1 day earlier, this equates to about $1,210 per patient in savings from bed costs alone,” Dr. Lundholm told this news organization.

The revised protocol required an additional two to four blood draws, depending on the length of the fast. “The cost of these extra blood tests varies by lab and by count, but even at its highest does not exceed the amount of savings from bed costs,” she noted.

Patient adherence is another potential benefit of the revised protocol.

“Any study that requires 72 hours of patient cooperation is a challenge, particularly in an uncomfortable position like fasting. When we looked at these adherence numbers, we found that the percentage of patients who prematurely ended their fast decreased from 35% to 17% with the updated protocol,” Dr. Lundholm continued.

“This translates to fewer inconclusive results and fewer readmissions for repeat 72-hour fasting. While this was not our primary outcome, it was another noted benefit of our change,” she said.

Dr. Lundholm and Dr. Sarvaideo have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

SEATTLE – , therefore yielding significant hospital cost savings, new data suggest.

Insulinomas are small, rare types of pancreatic tumors that are benign but secrete excess insulin, leading to hypoglycemia. More than 99% of people with insulinomas develop hypoglycemia within 72 hours, hence, the use of a 72-hour fast to detect these tumors.

But most people who are evaluated for hypoglycemia do not have an insulinoma and fasting in hospital for 3 days is burdensome and costly.

As part of a quality improvement project, Cleveland Clinic endocrinology fellow Michelle D. Lundholm, MD, and colleagues modified their hospital’s protocol to include measurement of beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), a marker of insulin suppression, every 12 hours with a cutoff of ≥ 2.7mmol/L for stopping the fast if hypoglycemia (venous glucose ≤ 45mg/dL) hasn’t occurred. This intervention cut in half the number of patients who needed to fast for the full 72 hours, without missing any insulinomas.

“We are excited to share how a relatively simple adjustment to our protocol allowed us to successfully reduce the burden of fasting on patients and more effectively utilize hospital resources. We hope that this encourages other centers to consider doing the same,” Dr. Lundholm said in an interview.

“These data support a 48-hour fast. The literature supports that’s sufficient to detect 95% of insulinomas. ... But, given our small insulinoma cohort, we are looking forward to learning from other studies,” she added.

Dr. Lundholm presented the late-breaking oral abstract at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

Asked to comment, session moderator Jenna Sarvaideo, MD, said: “We’re often steeped in tradition. That’s why this abstract and this quality improvement project is so exciting to me because it challenges the history. … and I think it’s ultimately helping patients.”

Dr. Sarvaideo, of Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center, Milwaukee, noted that, typically, although the fast will be stopped before 72 hours if the patient develops hypoglycemia, “often they don’t, so we keep going on and on. If we just paid more attention to the beta-hydroxybutyrate, I think that would be practice changing.”

She added that more data would be optimal, given that there were under 100 patients in the study, “but I do think that devising protocols is … very much still at the hands of the endocrinologists. I think that this work could make groups reevaluate their protocol and change it, maybe even with a small dataset and then move on from there and see what they see.”

Indeed, Dr. Lundholm pointed out that some institutions, such as the Mayo Clinic, already include 6-hour BHB measurements (along with glucose and insulin) in their protocols.

“For any institution that already draws regular BHB levels like this, it would be very easy to implement a new stopping criterion without adding any additional costs,” she said in an interview.

All insulinomas became apparent in less than 48 hours

The first report to look at the value of testing BHB at regular intervals was published by the Mayo Clinic in 2005 after they noticed patients without insulinoma were complaining of ketosis symptoms such as foul breath and digestive problems toward the end of the fast.

However, although BHB testing is used today as part of the evaluation, it’s typically only drawn at the start of the protocol and again at the time of hypoglycemia or at the end of 72 hours because more frequent values hadn’t been thought to be useful for guiding clinical management, Dr. Lundholm explained.

Between January 2018 and June 2020, Dr. Lundholm and colleagues followed 34 Cleveland Clinic patients who completed the usual 72-hour fast protocol. Overall, 71% were female, and 26% had undergone prior bariatric surgery procedures. Eleven (32%) developed hypoglycemia and stopped fasting. The other 23 (68%) fasted for the full 72 hours.

Dr. Lundholm and colleagues determined that the fast could have ended earlier in 35% of patients based on an elevated BHB without missing any insulinomas.

And so, in June 2020 the group revised their protocol to include the BHB ≥ 2.7mmol/L stopping criterion. Of the 30 patients evaluated from June 2020 to January 2023, 87% were female and 17% had undergone a bariatric procedure.

Here, 15 (50%) reached a BHB ≥ 2.7mmol/L and ended their fast at an average of 43.8 hours. Another seven (23%) ended the fast after developing hypoglycemia. Just eight patients (27%) fasted for the full 72 hours.

Overall, this resulted in approximately 376 fewer cumulative hours of inpatient admission than if patients had fasted for the full time.

Of the 64 patients who have completed the fasting protocol since 2018, seven (11%) who did have an insulinoma developed hypoglycemia within 48 hours and with a BHB < 2.7 mmol/L (median, 0.15).

Advantages: cost, adherence

A day in a general medicine bed at Cleveland Clinic was quoted as costing $2,420, based on publicly available information as of Jan. 1, 2023. “If half of patients leave 1 day earlier, this equates to about $1,210 per patient in savings from bed costs alone,” Dr. Lundholm told this news organization.

The revised protocol required an additional two to four blood draws, depending on the length of the fast. “The cost of these extra blood tests varies by lab and by count, but even at its highest does not exceed the amount of savings from bed costs,” she noted.

Patient adherence is another potential benefit of the revised protocol.

“Any study that requires 72 hours of patient cooperation is a challenge, particularly in an uncomfortable position like fasting. When we looked at these adherence numbers, we found that the percentage of patients who prematurely ended their fast decreased from 35% to 17% with the updated protocol,” Dr. Lundholm continued.

“This translates to fewer inconclusive results and fewer readmissions for repeat 72-hour fasting. While this was not our primary outcome, it was another noted benefit of our change,” she said.

Dr. Lundholm and Dr. Sarvaideo have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

SEATTLE – , therefore yielding significant hospital cost savings, new data suggest.

Insulinomas are small, rare types of pancreatic tumors that are benign but secrete excess insulin, leading to hypoglycemia. More than 99% of people with insulinomas develop hypoglycemia within 72 hours, hence, the use of a 72-hour fast to detect these tumors.

But most people who are evaluated for hypoglycemia do not have an insulinoma and fasting in hospital for 3 days is burdensome and costly.

As part of a quality improvement project, Cleveland Clinic endocrinology fellow Michelle D. Lundholm, MD, and colleagues modified their hospital’s protocol to include measurement of beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), a marker of insulin suppression, every 12 hours with a cutoff of ≥ 2.7mmol/L for stopping the fast if hypoglycemia (venous glucose ≤ 45mg/dL) hasn’t occurred. This intervention cut in half the number of patients who needed to fast for the full 72 hours, without missing any insulinomas.

“We are excited to share how a relatively simple adjustment to our protocol allowed us to successfully reduce the burden of fasting on patients and more effectively utilize hospital resources. We hope that this encourages other centers to consider doing the same,” Dr. Lundholm said in an interview.

“These data support a 48-hour fast. The literature supports that’s sufficient to detect 95% of insulinomas. ... But, given our small insulinoma cohort, we are looking forward to learning from other studies,” she added.

Dr. Lundholm presented the late-breaking oral abstract at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

Asked to comment, session moderator Jenna Sarvaideo, MD, said: “We’re often steeped in tradition. That’s why this abstract and this quality improvement project is so exciting to me because it challenges the history. … and I think it’s ultimately helping patients.”

Dr. Sarvaideo, of Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center, Milwaukee, noted that, typically, although the fast will be stopped before 72 hours if the patient develops hypoglycemia, “often they don’t, so we keep going on and on. If we just paid more attention to the beta-hydroxybutyrate, I think that would be practice changing.”

She added that more data would be optimal, given that there were under 100 patients in the study, “but I do think that devising protocols is … very much still at the hands of the endocrinologists. I think that this work could make groups reevaluate their protocol and change it, maybe even with a small dataset and then move on from there and see what they see.”

Indeed, Dr. Lundholm pointed out that some institutions, such as the Mayo Clinic, already include 6-hour BHB measurements (along with glucose and insulin) in their protocols.

“For any institution that already draws regular BHB levels like this, it would be very easy to implement a new stopping criterion without adding any additional costs,” she said in an interview.

All insulinomas became apparent in less than 48 hours

The first report to look at the value of testing BHB at regular intervals was published by the Mayo Clinic in 2005 after they noticed patients without insulinoma were complaining of ketosis symptoms such as foul breath and digestive problems toward the end of the fast.

However, although BHB testing is used today as part of the evaluation, it’s typically only drawn at the start of the protocol and again at the time of hypoglycemia or at the end of 72 hours because more frequent values hadn’t been thought to be useful for guiding clinical management, Dr. Lundholm explained.

Between January 2018 and June 2020, Dr. Lundholm and colleagues followed 34 Cleveland Clinic patients who completed the usual 72-hour fast protocol. Overall, 71% were female, and 26% had undergone prior bariatric surgery procedures. Eleven (32%) developed hypoglycemia and stopped fasting. The other 23 (68%) fasted for the full 72 hours.

Dr. Lundholm and colleagues determined that the fast could have ended earlier in 35% of patients based on an elevated BHB without missing any insulinomas.

And so, in June 2020 the group revised their protocol to include the BHB ≥ 2.7mmol/L stopping criterion. Of the 30 patients evaluated from June 2020 to January 2023, 87% were female and 17% had undergone a bariatric procedure.

Here, 15 (50%) reached a BHB ≥ 2.7mmol/L and ended their fast at an average of 43.8 hours. Another seven (23%) ended the fast after developing hypoglycemia. Just eight patients (27%) fasted for the full 72 hours.

Overall, this resulted in approximately 376 fewer cumulative hours of inpatient admission than if patients had fasted for the full time.

Of the 64 patients who have completed the fasting protocol since 2018, seven (11%) who did have an insulinoma developed hypoglycemia within 48 hours and with a BHB < 2.7 mmol/L (median, 0.15).

Advantages: cost, adherence

A day in a general medicine bed at Cleveland Clinic was quoted as costing $2,420, based on publicly available information as of Jan. 1, 2023. “If half of patients leave 1 day earlier, this equates to about $1,210 per patient in savings from bed costs alone,” Dr. Lundholm told this news organization.

The revised protocol required an additional two to four blood draws, depending on the length of the fast. “The cost of these extra blood tests varies by lab and by count, but even at its highest does not exceed the amount of savings from bed costs,” she noted.

Patient adherence is another potential benefit of the revised protocol.

“Any study that requires 72 hours of patient cooperation is a challenge, particularly in an uncomfortable position like fasting. When we looked at these adherence numbers, we found that the percentage of patients who prematurely ended their fast decreased from 35% to 17% with the updated protocol,” Dr. Lundholm continued.

“This translates to fewer inconclusive results and fewer readmissions for repeat 72-hour fasting. While this was not our primary outcome, it was another noted benefit of our change,” she said.

Dr. Lundholm and Dr. Sarvaideo have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AACE 2023

Part-time physician: Is it a viable career choice?

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

But physicians working part-time express a contrasting point of view. “I don’t believe that part-time workers are responsible for the health care shortage but rather, a great solution,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because in order to continue working for a long time rather than quitting when the demands exceed human capacity, working part time is a great compromise to offer a life of more sustainable well-being and longevity as a physician, and still live a wholehearted life.”

Pros and cons of being a part-time physician

Pros

Less burnout: The American Medical Association has tracked burnout rates for 22 years. By the end of 2021, nearly 63% of physicians reported burnout symptoms, compared with 38% the year before. Going part time appears to reduce burnout, suggests a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Better work-life balance: Rachel Miller, MD, an ob.gyn., worked 60-70 hours weekly for 9 years. In 2022, she went to work as an OB hospitalist for a health care system that welcomes part-time clinicians. Since then, she has achieved a better work-life balance, putting in 26-28 hours a week. Dr. Miller now spends more time with her kids and in her additional role as an executive coach to leaders in the medical field.

More focus: “When I’m at work, I’m 100% mentally in and focused,” said Dr. Miller. “My interactions with patients are different because I’m not burned out. My demeanor and my willingness to connect are stronger.”

Better health: Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, with CardioSolution, traded full-time work for part time when health issues and a kidney transplant sidelined his 30-year career in 2018. “Despite my significant health issues, I’ve been able to continue working at a pace that suits me rather than having to retire,” he said. “Part-time physicians can still enjoy patient care, research, innovation, education, and training while balancing that with other areas of life.”

Errin Weisman, a DO who gave up full-time work in 2016, said cutting back makes her feel healthier, happier, and more energized. “Part-time work helps me to bring my A game each day I work and deliver the best care.” She’s also a life coach encouraging other physicians to find balance in their professional and personal lives.

Cons

Cut in pay: Obviously, the No. 1 con is you’ll make less working part time, so adjusting to a salary decrease can be a huge issue, especially if you don’t have other sources of income. Physicians paying off student loans, those caring for children or elderly parents, or those in their prime earning years needing to save for retirement may not be able to go part time.

Diminished career: The chance for promotions or being well known in your field can be diminished, as well as a loss of proficiency if you’re only performing surgery or procedures part time. In some specialties, working part time and not keeping up with (or being able to practice) newer technology developments can harm your career or reputation in the long run.

Missing out: While working part time has many benefits, physicians also experience a wide range of drawbacks. Dr. Goodman, for example, said she misses delivering babies and doing surgeries. Dr. Miller said she gave up some aspects of her specialty, like performing hysterectomies, participating in complex cases, and no longer having an office like she did as a full-time ob.gyn.

Loss of fellowship: Dr. O’Connell said she missed the camaraderie and sense of belonging when she scaled back her hours. “I felt like a fish out of water, that my values didn’t align with the group’s values,” she said. This led to self-doubt, frustrated colleagues, and a reduction in benefits.

Lost esteem: Dr. O’Connell also felt she was expected to work overtime without additional pay and was no longer eligible for bonuses. “I was treated as a team player when I was needed, but not when it came to perks and benefits and insider privilege,” she said. There may be a loss of esteem among colleagues and supervisors.

Overcoming stigma: Because part-time physician work is still not prevalent among colleagues, some may resist the idea, have less respect for it, perceive it as not being serious about your career as a physician, or associate it with being lazy or entitled.

Summing it up

Every physician must weigh the value and drawbacks of part-time work, but the more physicians who go this route, the more part-time medicine gains traction and the more physicians can learn about its values versus its drawbacks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

But physicians working part-time express a contrasting point of view. “I don’t believe that part-time workers are responsible for the health care shortage but rather, a great solution,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because in order to continue working for a long time rather than quitting when the demands exceed human capacity, working part time is a great compromise to offer a life of more sustainable well-being and longevity as a physician, and still live a wholehearted life.”

Pros and cons of being a part-time physician

Pros

Less burnout: The American Medical Association has tracked burnout rates for 22 years. By the end of 2021, nearly 63% of physicians reported burnout symptoms, compared with 38% the year before. Going part time appears to reduce burnout, suggests a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Better work-life balance: Rachel Miller, MD, an ob.gyn., worked 60-70 hours weekly for 9 years. In 2022, she went to work as an OB hospitalist for a health care system that welcomes part-time clinicians. Since then, she has achieved a better work-life balance, putting in 26-28 hours a week. Dr. Miller now spends more time with her kids and in her additional role as an executive coach to leaders in the medical field.

More focus: “When I’m at work, I’m 100% mentally in and focused,” said Dr. Miller. “My interactions with patients are different because I’m not burned out. My demeanor and my willingness to connect are stronger.”

Better health: Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, with CardioSolution, traded full-time work for part time when health issues and a kidney transplant sidelined his 30-year career in 2018. “Despite my significant health issues, I’ve been able to continue working at a pace that suits me rather than having to retire,” he said. “Part-time physicians can still enjoy patient care, research, innovation, education, and training while balancing that with other areas of life.”

Errin Weisman, a DO who gave up full-time work in 2016, said cutting back makes her feel healthier, happier, and more energized. “Part-time work helps me to bring my A game each day I work and deliver the best care.” She’s also a life coach encouraging other physicians to find balance in their professional and personal lives.

Cons

Cut in pay: Obviously, the No. 1 con is you’ll make less working part time, so adjusting to a salary decrease can be a huge issue, especially if you don’t have other sources of income. Physicians paying off student loans, those caring for children or elderly parents, or those in their prime earning years needing to save for retirement may not be able to go part time.

Diminished career: The chance for promotions or being well known in your field can be diminished, as well as a loss of proficiency if you’re only performing surgery or procedures part time. In some specialties, working part time and not keeping up with (or being able to practice) newer technology developments can harm your career or reputation in the long run.

Missing out: While working part time has many benefits, physicians also experience a wide range of drawbacks. Dr. Goodman, for example, said she misses delivering babies and doing surgeries. Dr. Miller said she gave up some aspects of her specialty, like performing hysterectomies, participating in complex cases, and no longer having an office like she did as a full-time ob.gyn.

Loss of fellowship: Dr. O’Connell said she missed the camaraderie and sense of belonging when she scaled back her hours. “I felt like a fish out of water, that my values didn’t align with the group’s values,” she said. This led to self-doubt, frustrated colleagues, and a reduction in benefits.

Lost esteem: Dr. O’Connell also felt she was expected to work overtime without additional pay and was no longer eligible for bonuses. “I was treated as a team player when I was needed, but not when it came to perks and benefits and insider privilege,” she said. There may be a loss of esteem among colleagues and supervisors.

Overcoming stigma: Because part-time physician work is still not prevalent among colleagues, some may resist the idea, have less respect for it, perceive it as not being serious about your career as a physician, or associate it with being lazy or entitled.

Summing it up

Every physician must weigh the value and drawbacks of part-time work, but the more physicians who go this route, the more part-time medicine gains traction and the more physicians can learn about its values versus its drawbacks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.