User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Survey: 2020 will see more attacks on ACA

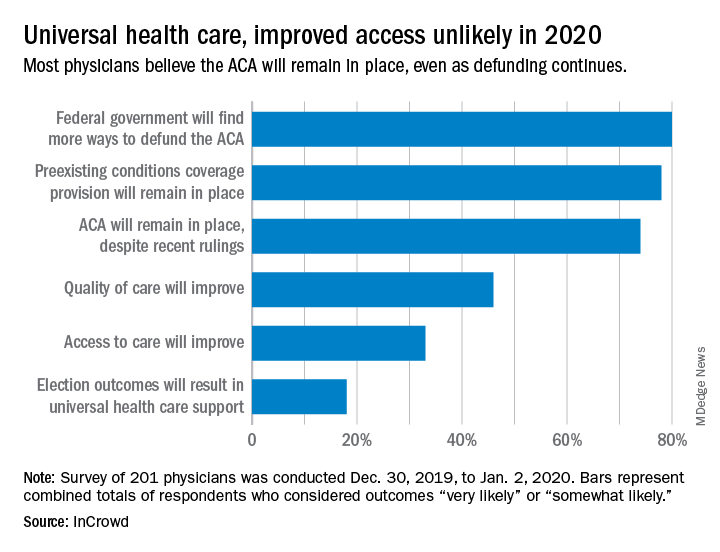

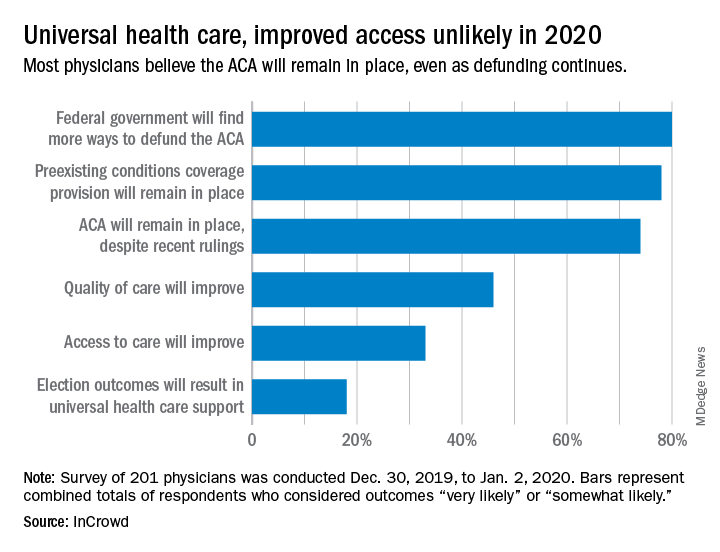

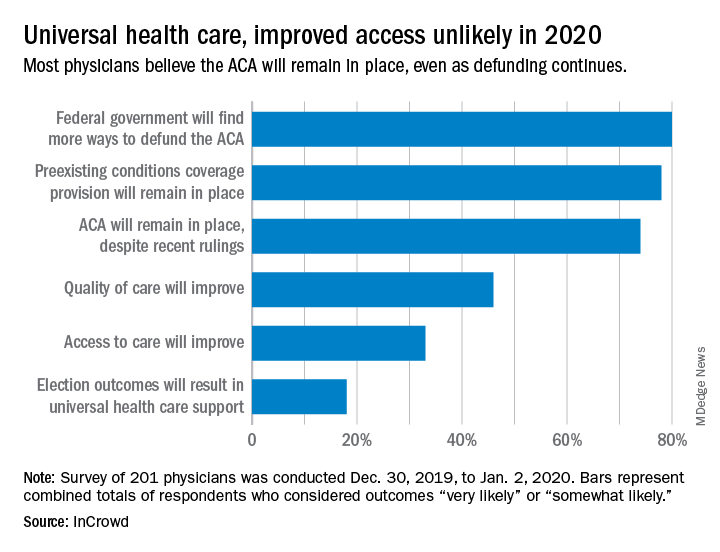

When physicians gaze into their crystal balls to predict what’s coming in 2020, they see continued efforts to defund the Affordable Care Act – meaning the ACA will still be around to be defunded – but they don’t see a lot of support for universal health care, according to health care market research company InCrowd.

Expectations for universal health care came in at 18% of the 100 generalists and 101 specialists who responded to InCrowd’s fifth annual health care predictions survey, which left 82% who thought that “election outcomes will result in universal healthcare support” was somewhat or very unlikely in 2020.

One respondent, a specialist from California, commented that “the global data on universal healthcare for all shows that it results in overall improved population health. Unfortunately, we are so polarized in the US against universal healthcare driven by bias from health insurance companies and decision makers that are quick to ignore scientific data.”

This was the first time InCrowd asked physicians about universal health care, but ACA-related predictions have been included before, and all three scenarios presented were deemed to be increasingly likely, compared with 2019.

Respondents thought that federal government defunding was more likely to occur in 2020 (80%) than in 2019 (73%), but increased majorities also said that preexisting conditions coverage would continue (78% in 2020 vs. 70% in 2019) and that the ACA would remain in place (74% in 2020 vs. 60% in 2019), InCrowd reported after the survey, which was conducted from Dec. 30, 2019, to Jan. 2, 2020.

A respondent who thought the ACA will be eliminated said, “I have as many uninsured today as before the ACA. They are just different. Mainly younger patients who spend less in a year on healthcare than one month’s premium.” Another suggested that eliminateing it “will limit access to care and overload [emergency departments]. More people will die.”

Cost was addressed in a separate survey question that asked how physicians could help to reduce health care spending in 2020.

The leading answer, given by 37% of respondents, was for physicians to “inform themselves of costs and adapt cost-saving prescription practices.” Next came “limit use of expensive tests and scans” with 21%, followed by “prescribe generics when possible” at 20%, which was a substantial drop from the 38% it garnered in 2019, InCrowd noted.

“Participation in [shared savings] programs and risk-based incentive programs and pay-for-performance programs” would provide “better stewardship of resources,” a primary care physician from Michigan wrote.

When the survey turned to pharmaceutical industry predictions for 2020, cost was the major issue.

“What’s interesting about this year’s data is that we’re seeing less emphasis on the importance of bringing innovative, new therapies to market faster … versus expanding affordability, which was nearly a unanimous top priority for respondents,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, InCrowd’s CEO and president, said in a separate statement.

When physicians gaze into their crystal balls to predict what’s coming in 2020, they see continued efforts to defund the Affordable Care Act – meaning the ACA will still be around to be defunded – but they don’t see a lot of support for universal health care, according to health care market research company InCrowd.

Expectations for universal health care came in at 18% of the 100 generalists and 101 specialists who responded to InCrowd’s fifth annual health care predictions survey, which left 82% who thought that “election outcomes will result in universal healthcare support” was somewhat or very unlikely in 2020.

One respondent, a specialist from California, commented that “the global data on universal healthcare for all shows that it results in overall improved population health. Unfortunately, we are so polarized in the US against universal healthcare driven by bias from health insurance companies and decision makers that are quick to ignore scientific data.”

This was the first time InCrowd asked physicians about universal health care, but ACA-related predictions have been included before, and all three scenarios presented were deemed to be increasingly likely, compared with 2019.

Respondents thought that federal government defunding was more likely to occur in 2020 (80%) than in 2019 (73%), but increased majorities also said that preexisting conditions coverage would continue (78% in 2020 vs. 70% in 2019) and that the ACA would remain in place (74% in 2020 vs. 60% in 2019), InCrowd reported after the survey, which was conducted from Dec. 30, 2019, to Jan. 2, 2020.

A respondent who thought the ACA will be eliminated said, “I have as many uninsured today as before the ACA. They are just different. Mainly younger patients who spend less in a year on healthcare than one month’s premium.” Another suggested that eliminateing it “will limit access to care and overload [emergency departments]. More people will die.”

Cost was addressed in a separate survey question that asked how physicians could help to reduce health care spending in 2020.

The leading answer, given by 37% of respondents, was for physicians to “inform themselves of costs and adapt cost-saving prescription practices.” Next came “limit use of expensive tests and scans” with 21%, followed by “prescribe generics when possible” at 20%, which was a substantial drop from the 38% it garnered in 2019, InCrowd noted.

“Participation in [shared savings] programs and risk-based incentive programs and pay-for-performance programs” would provide “better stewardship of resources,” a primary care physician from Michigan wrote.

When the survey turned to pharmaceutical industry predictions for 2020, cost was the major issue.

“What’s interesting about this year’s data is that we’re seeing less emphasis on the importance of bringing innovative, new therapies to market faster … versus expanding affordability, which was nearly a unanimous top priority for respondents,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, InCrowd’s CEO and president, said in a separate statement.

When physicians gaze into their crystal balls to predict what’s coming in 2020, they see continued efforts to defund the Affordable Care Act – meaning the ACA will still be around to be defunded – but they don’t see a lot of support for universal health care, according to health care market research company InCrowd.

Expectations for universal health care came in at 18% of the 100 generalists and 101 specialists who responded to InCrowd’s fifth annual health care predictions survey, which left 82% who thought that “election outcomes will result in universal healthcare support” was somewhat or very unlikely in 2020.

One respondent, a specialist from California, commented that “the global data on universal healthcare for all shows that it results in overall improved population health. Unfortunately, we are so polarized in the US against universal healthcare driven by bias from health insurance companies and decision makers that are quick to ignore scientific data.”

This was the first time InCrowd asked physicians about universal health care, but ACA-related predictions have been included before, and all three scenarios presented were deemed to be increasingly likely, compared with 2019.

Respondents thought that federal government defunding was more likely to occur in 2020 (80%) than in 2019 (73%), but increased majorities also said that preexisting conditions coverage would continue (78% in 2020 vs. 70% in 2019) and that the ACA would remain in place (74% in 2020 vs. 60% in 2019), InCrowd reported after the survey, which was conducted from Dec. 30, 2019, to Jan. 2, 2020.

A respondent who thought the ACA will be eliminated said, “I have as many uninsured today as before the ACA. They are just different. Mainly younger patients who spend less in a year on healthcare than one month’s premium.” Another suggested that eliminateing it “will limit access to care and overload [emergency departments]. More people will die.”

Cost was addressed in a separate survey question that asked how physicians could help to reduce health care spending in 2020.

The leading answer, given by 37% of respondents, was for physicians to “inform themselves of costs and adapt cost-saving prescription practices.” Next came “limit use of expensive tests and scans” with 21%, followed by “prescribe generics when possible” at 20%, which was a substantial drop from the 38% it garnered in 2019, InCrowd noted.

“Participation in [shared savings] programs and risk-based incentive programs and pay-for-performance programs” would provide “better stewardship of resources,” a primary care physician from Michigan wrote.

When the survey turned to pharmaceutical industry predictions for 2020, cost was the major issue.

“What’s interesting about this year’s data is that we’re seeing less emphasis on the importance of bringing innovative, new therapies to market faster … versus expanding affordability, which was nearly a unanimous top priority for respondents,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, InCrowd’s CEO and president, said in a separate statement.

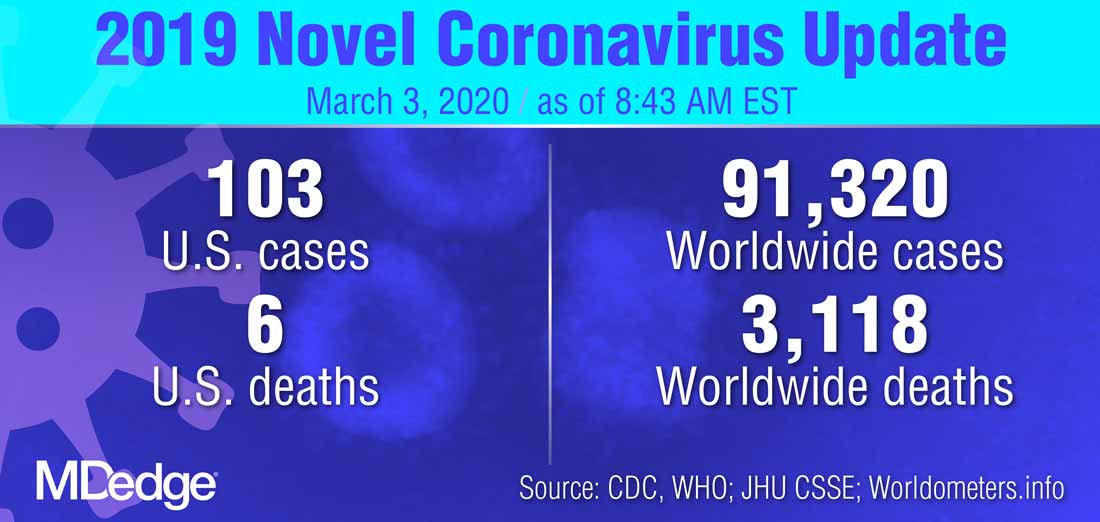

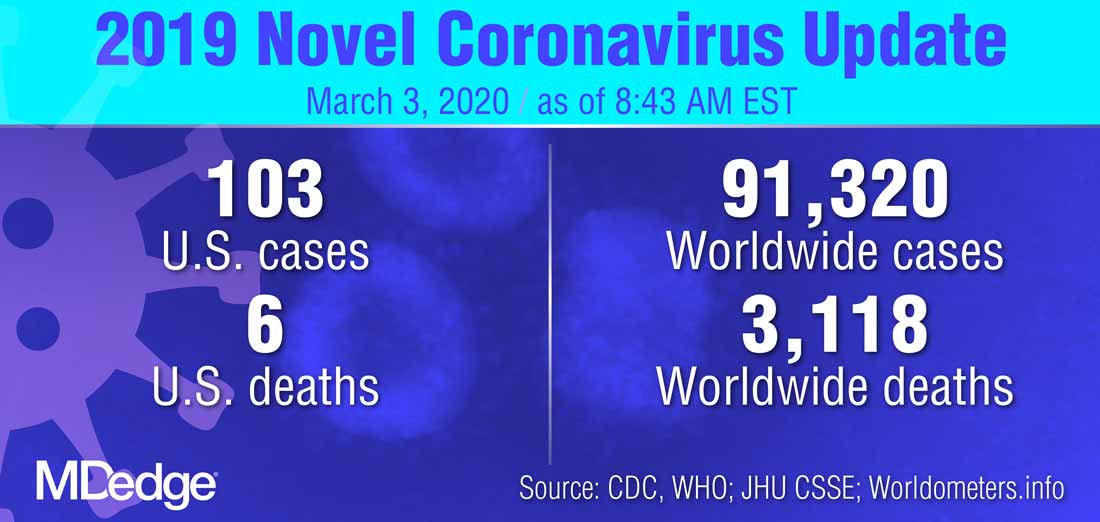

FDA moves to expand coronavirus testing capacity; CDC clarifies testing criteria

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

FROM A PRESS BRIEFING BY THE WHITE HOUSE CORONAVIRUS TASK FORCE

Pembro ups survival in NSCLC: ‘Really extraordinary’ results

More than a third (35%) of patients with relapsed non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) were still alive at 3 years, according to long-term results from a pivotal clinical trial.

The results also showed that, among the 10% of patients who completed all 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, the 3-year overall survival was approximately 99%, with progression-free survival (PFS) at around 70%.

“It is too soon to say that pembrolizumab is a potential cure...and we know that it doesn’t work for all patients, but the agent remains very, very promising,” said lead investigator Roy Herbst, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center, New Haven, Connecticut.

These new results come from the KEYNOTE-010 trial, conducted in more than 1000 patients with NSCLC who had progressed on chemotherapy, randomized to receive immunotherapy with pembrolizumab or chemotherapy with docetaxel.

The results were published online on February 20 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and were previously presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the European Society of Medical Oncology.

Overall survival at 3 years was 35% in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 50% in the tumor, and 23% in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

This compares with 3-year overall survival of 11-13% with docetaxel.

These results are “really extraordinary,” Herbst commented to Medscape Medical News.

The 3-year overall survival rate of 35% in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% “is huge,” he said. “It really shows the durability of the response.”

Herbst commented that the “almost 100%” survival at 3 years among patients who completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab shows that this treatment period (of about 2 years) is “probably about the right time to treat.”

“Currently, the agent is being used in all potential settings, before any other treatment, after other treatment, and with other treatments,” he said.

“Our hope is to find the very best way to use pembrolizumab to treat individual lung cancer patients, assessing how much PD-L1 a tumor expresses, what stage the patient is in, as well as other variables and biomarkers we are working on. This is the story of tailored therapy,” Herbst said.

Approached for comment, Solange Peters, MD, PhD, Oncology Department, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland, said that the results are “very good” and “confirm the paradigms we have been seeing in melanoma,” with good long-term control, which is “very reassuring.”

However, she told Medscape Medical News that the trial raises an important question: «How long do you need to expose your patient with lung cancer to immunotherapy in order to get this long-term control?»

She said the “good news” is that, for the 10% of patients who completed 2 years of treatment per protocol, almost all of them are still alive at 3 years, “which is not observed with chemotherapy.”

The question for Peters is “more about the definition of long-term control,” as it was seen that almost one in three patients nevertheless had some form of progression.

This suggests that you have a group of people “who are nicely controlled, you stop the drug, and 1 year later a third of them have progressed.”

Peters said: “So how long do you need to treat these patients? I would say I still don’t know.”

“If I were one of these patients probably I would still want to continue [on the drug]. Of course, some might have progressed even while remaining on the drug, but the proportion who would have progressed is probably smaller than this one.”

Responses on Re-introduction of Therapy

The study also allowed patients who had completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab to be restarted on the drug if they experienced progression.

The team found that, among 14 patients, 43% had a partial response and 36% had stable disease.

Herbst highlighted this finding and told Medscape Medical News that this «could be very important to physicians because they might want to think about using the drug again» in patients who have progressed on it.

He believes that the progression was not because of any resistance per se but rather a slowing down of the adaptive immune response.

“It’s just that it needs a boost,” he said, while noting that tissue specimens will nevertheless be required to demonstrate the theory.

Peters agreed that these results are “very promising,” but questioned their overall significance, as it is “a very small number of patients” from a subset whose disease was controlled while on treatment and then progressed after stopping.

She also pointed out that, in another study in patients with lung cancer (CheckMate-153), some patients were rechallenged with immunotherapy after having stopped treatment at 1 year “with very poor results.”

Peters said studies in melanoma have shown “rechallenge can be useful in a significant proportion of patients, but still you have not demonstrated that stopping and rechallenging is the same as not stopping.”

Study Details

KEYNOTE-010 involved patients with NSCLC from 202 centers in 24 countries with stage IIIB/IV disease expressing PD-L1 who had experienced disease progression after at least two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy.

They were randomized 1:1:1 to open-label pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg, pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg, or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.

Pembrolizumab was continued for 35 treatment cycles over 2 years and docetaxel was continued for the maximum duration allowed by local regulators.

Patients who stopped pembrolizumab after a complete response or completing all 35 cycles, and who subsequently experienced disease progression, could receive up to 17 additional cycles over 1 year if they had not received another anticancer therapy in the meantime.

Among the 1,034 patients originally recruited between August 2013 and February 2015, 691 were assigned to pembrolizumab at 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg and 343 to docetaxel.

For the intention-to-treat analysis in 1033 patients, the mean duration of follow-up was 42.6 months, with a median treatment duration of 3.5 months in the pembrolizumab group and 2.0 months in the docetaxel group.

Compared with docetaxel, pembrolizumab was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of death, at a hazard ratio of 0.53 in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.69 in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1% (both P < .0001).

In patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50%, median overall survival was 16.9 months in those given pembrolizumab and 8.2 months with docetaxel. Among those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%, median overall survival was 11.8 months with pembrolizumab versus 8.4 months with docetaxel.

Overall survival on Kaplan-Meier analysis was 34.5% with pembrolizumab and 12.7% with docetaxel in the PD-L1 ≥ 50% group, and 22.9% versus 11.0% in the PD-L1 ≥ 1% group.

PFS significantly improved with pembrolizumab versus docetaxel, at a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P < .00001) among patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.83 (P < .005) in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

In terms of safety, 17.7% of patients who completed 2 years of pembrolizumab had grade 3-5 treatment-related adverse events, compared with 16.6% among all pembrolizumab-treated patients and 36.6% of those given docetaxel.

The team reports that 79 patients completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, with a median follow-up of 43.4 months.

Compared with the overall patient group, these patients were less likely to be aged ≥ 65 years and to have received two or more prior treatment lines, although they were more likely to be current or former smokers and to have squamous tumor histology.

Patients who completed 35 cycles had an objective response rate of 94.9%, and 91.0% were still alive at the data cutoff. Overall survival rates were 98.7% at 12 months and 86.3% at 24 months.

Of 71 patients eligible for analysis, 23 experienced progression after completing pembrolizumab, at PFS rates at 12 and 24 months of 72.5% and 57.7%, respectively.

A total of 14 patients were given a second course of pembrolizumab, of whom six had a partial response and five had stable disease. At the data cutoff, five patients had completed 17 additional cycles and 11 were alive.

Pembro Approved at Fixed Dose

One notable aspect of the study is that patients in the pembrolizumab arm were given two different doses of the drug based on body weight, whereas the drug is approved in the United States at a fixed dose of 200 mg.

Herbst told Medscape Medical News he considers the 200-mg dose to be appropriate.

“I didn’t think that the 3-mg versus 10-mg dose per kg that we used in our study made much difference in an average-sized person,” he said, adding that the 200-mg dose “is something a little bit more than 3 mg/kg.”

“So I think that this is clearly the right dos, and I don’t think more would make any difference,” he said.

The study was funded by Merck, the manufacturer of pembrolizumab. Herbst has reported having a consulting or advisory role for many pharmaceutical companies. Other coauthors have also reported relationships with industry, and some of the authors are Merck employees. Peters has reported receiving education grants, providing consultation, attending advisory boards, and/or providing lectures for many pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than a third (35%) of patients with relapsed non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) were still alive at 3 years, according to long-term results from a pivotal clinical trial.

The results also showed that, among the 10% of patients who completed all 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, the 3-year overall survival was approximately 99%, with progression-free survival (PFS) at around 70%.

“It is too soon to say that pembrolizumab is a potential cure...and we know that it doesn’t work for all patients, but the agent remains very, very promising,” said lead investigator Roy Herbst, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center, New Haven, Connecticut.

These new results come from the KEYNOTE-010 trial, conducted in more than 1000 patients with NSCLC who had progressed on chemotherapy, randomized to receive immunotherapy with pembrolizumab or chemotherapy with docetaxel.

The results were published online on February 20 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and were previously presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the European Society of Medical Oncology.

Overall survival at 3 years was 35% in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 50% in the tumor, and 23% in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

This compares with 3-year overall survival of 11-13% with docetaxel.

These results are “really extraordinary,” Herbst commented to Medscape Medical News.

The 3-year overall survival rate of 35% in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% “is huge,” he said. “It really shows the durability of the response.”

Herbst commented that the “almost 100%” survival at 3 years among patients who completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab shows that this treatment period (of about 2 years) is “probably about the right time to treat.”

“Currently, the agent is being used in all potential settings, before any other treatment, after other treatment, and with other treatments,” he said.

“Our hope is to find the very best way to use pembrolizumab to treat individual lung cancer patients, assessing how much PD-L1 a tumor expresses, what stage the patient is in, as well as other variables and biomarkers we are working on. This is the story of tailored therapy,” Herbst said.

Approached for comment, Solange Peters, MD, PhD, Oncology Department, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland, said that the results are “very good” and “confirm the paradigms we have been seeing in melanoma,” with good long-term control, which is “very reassuring.”

However, she told Medscape Medical News that the trial raises an important question: «How long do you need to expose your patient with lung cancer to immunotherapy in order to get this long-term control?»

She said the “good news” is that, for the 10% of patients who completed 2 years of treatment per protocol, almost all of them are still alive at 3 years, “which is not observed with chemotherapy.”

The question for Peters is “more about the definition of long-term control,” as it was seen that almost one in three patients nevertheless had some form of progression.

This suggests that you have a group of people “who are nicely controlled, you stop the drug, and 1 year later a third of them have progressed.”

Peters said: “So how long do you need to treat these patients? I would say I still don’t know.”

“If I were one of these patients probably I would still want to continue [on the drug]. Of course, some might have progressed even while remaining on the drug, but the proportion who would have progressed is probably smaller than this one.”

Responses on Re-introduction of Therapy

The study also allowed patients who had completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab to be restarted on the drug if they experienced progression.

The team found that, among 14 patients, 43% had a partial response and 36% had stable disease.

Herbst highlighted this finding and told Medscape Medical News that this «could be very important to physicians because they might want to think about using the drug again» in patients who have progressed on it.

He believes that the progression was not because of any resistance per se but rather a slowing down of the adaptive immune response.

“It’s just that it needs a boost,” he said, while noting that tissue specimens will nevertheless be required to demonstrate the theory.

Peters agreed that these results are “very promising,” but questioned their overall significance, as it is “a very small number of patients” from a subset whose disease was controlled while on treatment and then progressed after stopping.

She also pointed out that, in another study in patients with lung cancer (CheckMate-153), some patients were rechallenged with immunotherapy after having stopped treatment at 1 year “with very poor results.”

Peters said studies in melanoma have shown “rechallenge can be useful in a significant proportion of patients, but still you have not demonstrated that stopping and rechallenging is the same as not stopping.”

Study Details

KEYNOTE-010 involved patients with NSCLC from 202 centers in 24 countries with stage IIIB/IV disease expressing PD-L1 who had experienced disease progression after at least two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy.

They were randomized 1:1:1 to open-label pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg, pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg, or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.

Pembrolizumab was continued for 35 treatment cycles over 2 years and docetaxel was continued for the maximum duration allowed by local regulators.

Patients who stopped pembrolizumab after a complete response or completing all 35 cycles, and who subsequently experienced disease progression, could receive up to 17 additional cycles over 1 year if they had not received another anticancer therapy in the meantime.

Among the 1,034 patients originally recruited between August 2013 and February 2015, 691 were assigned to pembrolizumab at 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg and 343 to docetaxel.

For the intention-to-treat analysis in 1033 patients, the mean duration of follow-up was 42.6 months, with a median treatment duration of 3.5 months in the pembrolizumab group and 2.0 months in the docetaxel group.

Compared with docetaxel, pembrolizumab was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of death, at a hazard ratio of 0.53 in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.69 in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1% (both P < .0001).

In patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50%, median overall survival was 16.9 months in those given pembrolizumab and 8.2 months with docetaxel. Among those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%, median overall survival was 11.8 months with pembrolizumab versus 8.4 months with docetaxel.

Overall survival on Kaplan-Meier analysis was 34.5% with pembrolizumab and 12.7% with docetaxel in the PD-L1 ≥ 50% group, and 22.9% versus 11.0% in the PD-L1 ≥ 1% group.

PFS significantly improved with pembrolizumab versus docetaxel, at a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P < .00001) among patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.83 (P < .005) in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

In terms of safety, 17.7% of patients who completed 2 years of pembrolizumab had grade 3-5 treatment-related adverse events, compared with 16.6% among all pembrolizumab-treated patients and 36.6% of those given docetaxel.

The team reports that 79 patients completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, with a median follow-up of 43.4 months.

Compared with the overall patient group, these patients were less likely to be aged ≥ 65 years and to have received two or more prior treatment lines, although they were more likely to be current or former smokers and to have squamous tumor histology.

Patients who completed 35 cycles had an objective response rate of 94.9%, and 91.0% were still alive at the data cutoff. Overall survival rates were 98.7% at 12 months and 86.3% at 24 months.

Of 71 patients eligible for analysis, 23 experienced progression after completing pembrolizumab, at PFS rates at 12 and 24 months of 72.5% and 57.7%, respectively.

A total of 14 patients were given a second course of pembrolizumab, of whom six had a partial response and five had stable disease. At the data cutoff, five patients had completed 17 additional cycles and 11 were alive.

Pembro Approved at Fixed Dose

One notable aspect of the study is that patients in the pembrolizumab arm were given two different doses of the drug based on body weight, whereas the drug is approved in the United States at a fixed dose of 200 mg.

Herbst told Medscape Medical News he considers the 200-mg dose to be appropriate.

“I didn’t think that the 3-mg versus 10-mg dose per kg that we used in our study made much difference in an average-sized person,” he said, adding that the 200-mg dose “is something a little bit more than 3 mg/kg.”

“So I think that this is clearly the right dos, and I don’t think more would make any difference,” he said.

The study was funded by Merck, the manufacturer of pembrolizumab. Herbst has reported having a consulting or advisory role for many pharmaceutical companies. Other coauthors have also reported relationships with industry, and some of the authors are Merck employees. Peters has reported receiving education grants, providing consultation, attending advisory boards, and/or providing lectures for many pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than a third (35%) of patients with relapsed non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) were still alive at 3 years, according to long-term results from a pivotal clinical trial.

The results also showed that, among the 10% of patients who completed all 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, the 3-year overall survival was approximately 99%, with progression-free survival (PFS) at around 70%.

“It is too soon to say that pembrolizumab is a potential cure...and we know that it doesn’t work for all patients, but the agent remains very, very promising,” said lead investigator Roy Herbst, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center, New Haven, Connecticut.

These new results come from the KEYNOTE-010 trial, conducted in more than 1000 patients with NSCLC who had progressed on chemotherapy, randomized to receive immunotherapy with pembrolizumab or chemotherapy with docetaxel.

The results were published online on February 20 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and were previously presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the European Society of Medical Oncology.

Overall survival at 3 years was 35% in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 50% in the tumor, and 23% in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

This compares with 3-year overall survival of 11-13% with docetaxel.

These results are “really extraordinary,” Herbst commented to Medscape Medical News.

The 3-year overall survival rate of 35% in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% “is huge,” he said. “It really shows the durability of the response.”

Herbst commented that the “almost 100%” survival at 3 years among patients who completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab shows that this treatment period (of about 2 years) is “probably about the right time to treat.”

“Currently, the agent is being used in all potential settings, before any other treatment, after other treatment, and with other treatments,” he said.

“Our hope is to find the very best way to use pembrolizumab to treat individual lung cancer patients, assessing how much PD-L1 a tumor expresses, what stage the patient is in, as well as other variables and biomarkers we are working on. This is the story of tailored therapy,” Herbst said.

Approached for comment, Solange Peters, MD, PhD, Oncology Department, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland, said that the results are “very good” and “confirm the paradigms we have been seeing in melanoma,” with good long-term control, which is “very reassuring.”

However, she told Medscape Medical News that the trial raises an important question: «How long do you need to expose your patient with lung cancer to immunotherapy in order to get this long-term control?»

She said the “good news” is that, for the 10% of patients who completed 2 years of treatment per protocol, almost all of them are still alive at 3 years, “which is not observed with chemotherapy.”

The question for Peters is “more about the definition of long-term control,” as it was seen that almost one in three patients nevertheless had some form of progression.

This suggests that you have a group of people “who are nicely controlled, you stop the drug, and 1 year later a third of them have progressed.”

Peters said: “So how long do you need to treat these patients? I would say I still don’t know.”

“If I were one of these patients probably I would still want to continue [on the drug]. Of course, some might have progressed even while remaining on the drug, but the proportion who would have progressed is probably smaller than this one.”

Responses on Re-introduction of Therapy

The study also allowed patients who had completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab to be restarted on the drug if they experienced progression.

The team found that, among 14 patients, 43% had a partial response and 36% had stable disease.

Herbst highlighted this finding and told Medscape Medical News that this «could be very important to physicians because they might want to think about using the drug again» in patients who have progressed on it.

He believes that the progression was not because of any resistance per se but rather a slowing down of the adaptive immune response.

“It’s just that it needs a boost,” he said, while noting that tissue specimens will nevertheless be required to demonstrate the theory.

Peters agreed that these results are “very promising,” but questioned their overall significance, as it is “a very small number of patients” from a subset whose disease was controlled while on treatment and then progressed after stopping.

She also pointed out that, in another study in patients with lung cancer (CheckMate-153), some patients were rechallenged with immunotherapy after having stopped treatment at 1 year “with very poor results.”

Peters said studies in melanoma have shown “rechallenge can be useful in a significant proportion of patients, but still you have not demonstrated that stopping and rechallenging is the same as not stopping.”

Study Details

KEYNOTE-010 involved patients with NSCLC from 202 centers in 24 countries with stage IIIB/IV disease expressing PD-L1 who had experienced disease progression after at least two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy.

They were randomized 1:1:1 to open-label pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg, pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg, or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.

Pembrolizumab was continued for 35 treatment cycles over 2 years and docetaxel was continued for the maximum duration allowed by local regulators.

Patients who stopped pembrolizumab after a complete response or completing all 35 cycles, and who subsequently experienced disease progression, could receive up to 17 additional cycles over 1 year if they had not received another anticancer therapy in the meantime.

Among the 1,034 patients originally recruited between August 2013 and February 2015, 691 were assigned to pembrolizumab at 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg and 343 to docetaxel.

For the intention-to-treat analysis in 1033 patients, the mean duration of follow-up was 42.6 months, with a median treatment duration of 3.5 months in the pembrolizumab group and 2.0 months in the docetaxel group.

Compared with docetaxel, pembrolizumab was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of death, at a hazard ratio of 0.53 in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.69 in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1% (both P < .0001).

In patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50%, median overall survival was 16.9 months in those given pembrolizumab and 8.2 months with docetaxel. Among those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%, median overall survival was 11.8 months with pembrolizumab versus 8.4 months with docetaxel.

Overall survival on Kaplan-Meier analysis was 34.5% with pembrolizumab and 12.7% with docetaxel in the PD-L1 ≥ 50% group, and 22.9% versus 11.0% in the PD-L1 ≥ 1% group.

PFS significantly improved with pembrolizumab versus docetaxel, at a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P < .00001) among patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.83 (P < .005) in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

In terms of safety, 17.7% of patients who completed 2 years of pembrolizumab had grade 3-5 treatment-related adverse events, compared with 16.6% among all pembrolizumab-treated patients and 36.6% of those given docetaxel.

The team reports that 79 patients completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, with a median follow-up of 43.4 months.

Compared with the overall patient group, these patients were less likely to be aged ≥ 65 years and to have received two or more prior treatment lines, although they were more likely to be current or former smokers and to have squamous tumor histology.

Patients who completed 35 cycles had an objective response rate of 94.9%, and 91.0% were still alive at the data cutoff. Overall survival rates were 98.7% at 12 months and 86.3% at 24 months.

Of 71 patients eligible for analysis, 23 experienced progression after completing pembrolizumab, at PFS rates at 12 and 24 months of 72.5% and 57.7%, respectively.

A total of 14 patients were given a second course of pembrolizumab, of whom six had a partial response and five had stable disease. At the data cutoff, five patients had completed 17 additional cycles and 11 were alive.

Pembro Approved at Fixed Dose

One notable aspect of the study is that patients in the pembrolizumab arm were given two different doses of the drug based on body weight, whereas the drug is approved in the United States at a fixed dose of 200 mg.

Herbst told Medscape Medical News he considers the 200-mg dose to be appropriate.

“I didn’t think that the 3-mg versus 10-mg dose per kg that we used in our study made much difference in an average-sized person,” he said, adding that the 200-mg dose “is something a little bit more than 3 mg/kg.”

“So I think that this is clearly the right dos, and I don’t think more would make any difference,” he said.

The study was funded by Merck, the manufacturer of pembrolizumab. Herbst has reported having a consulting or advisory role for many pharmaceutical companies. Other coauthors have also reported relationships with industry, and some of the authors are Merck employees. Peters has reported receiving education grants, providing consultation, attending advisory boards, and/or providing lectures for many pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Varied nightly bedtime, sleep duration linked to CVD risk

People who frequently alter the amount of sleep and time they go to bed each night are twofold more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, independent of traditional CVD risk factors, new research suggests.

Prior studies have focused on shift workers because night shift work will influence circadian rhythm and increase CVD risk. But it is increasingly recognized that circadian disruption may occur outside of shift work and accumulate over time, particularly given modern lifestyle factors such as increased use of mobile devices and television at night, said study coauthor Tianyi Huang, ScD, MSc, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Even if they tend to go to sleep at certain times, by following that lifestyle or behavior, it can interfere with their planned sleep timing,” he said.

“One thing that surprised me in this sample is that about one third of participants have irregular sleep patterns that can put them at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. So I think the prevalence is higher than expected,” Huang added.

As reported today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators used data from 7-day wrist actigraphy, 1 night of at-home polysomnography, and sleep questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep-onset timing among 1,992 Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis () participants, aged 45 to 84 years, who were free of CVD and prospectively followed for a me MESA dian of 4.9 years.

A total of 786 patients (39.5%) had sleep duration standard deviation (SD) > 90 minutes and 510 (25.6%) had sleep-onset timing SD > 90 minutes.

During follow-up, there were 111 incident CVD events, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease death, stroke, and other coronary events.

Compared with people who had less than 1 hour of variation in sleep duration, the risk for incident CVD was 9% higher for people whose sleep duration varied 61 to 90 minutes (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 - 1.92), even after controlling for a variety of cardiovascular and sleep-related risk factors such as body mass index, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, total cholesterol, average sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep apnea.

Moreover, the adjusted CVD risk was substantially increased with 91 to 120 minutes of variation (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.91 - 2.76) and more than 120 minutes of variation in sleep duration (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.24 - 3.68).

Every 1-hour increase in sleep duration SD was associated with 36% higher CVD risk (95% CI; 1.07 - 1.73).

Compared with people with no more than a half hour of variation in nightly bedtimes, the adjusted hazard ratios for CVD were 1.16 (95% CI, 0.64 - 2.13), 1.52 (95% CI, 0.81 - 2.88), and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.13 - 3.91) when bedtimes varied by 31 to 60 minutes, 61 to 90 minutes, and more than 90 minutes.

For every 1-hour increase in sleep-onset timing SD, the risk of CVD was 18% higher (95% CI; 1.06 - 1.31).

“The results are similar for the regularity of sleep timing and the regularity of sleep duration, which means that both can contribute to circadian disruption and then lead to development of cardiovascular disease,” Huang said.

This is an important article and signals how sleep is an important marker and possibly a mediator of cardiovascular risk, said Harlan Krumholz, MD, of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not involved with the study.

“What I like about this is it’s a nice longitudinal, epidemiologic study with not just self-report, but sensor-detected sleep, that has been correlated with well-curated and adjudicated outcomes to give us a strong sense of this association,” he told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. “And also, that it goes beyond just the duration — they combine the duration and timing in order to give a fuller picture of sleep.”

Nevertheless, Krumholz said researchers are only at the beginning of being able to quantify the various dimensions of sleep and the degree to which sleep is a reflection of underlying physiologic issues, or whether patients are having erratic sleep patterns that are having a toxic effect on their overall health.

Questions also remain about the mechanism behind the association, whether the increased risk is universal or more harmful for some people, and the best way to measure factors during sleep that can most comprehensively and precisely predict risk.

“As we get more information flowing in from sensors, I think we will begin to develop more sophisticated approaches toward understanding risk, and it will be accompanied by other studies that will help us understand whether, again, this is a reflection of other processes that we should be paying attention to or whether it is a cause of disease and risk,” Krumholz said.

Subgroup analyses suggested positive associations between irregular sleep and CVD in African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans but not in whites. This could be because sleep irregularity, both timing and duration, was substantially higher in minorities, especially African Americans, but may also be as a result of chance because the study sample is relatively small, Huang explained.

The authors note that the overall findings are biologically plausible because of their previous work linking sleep irregularity with metabolic risk factors that predispose to atherosclerosis, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Participants with irregular sleep tended to have worse baseline cardiometabolic profiles, but this only explained a small portion of the associations between sleep irregularity and CVD, they note.

Other possible explanations include circadian clock genes, such as clock, per2 and bmal1, which have been shown experimentally to control a broad range of cardiovascular functions, from blood pressure and endothelial functions to vascular thrombosis and cardiac remodeling.

Irregular sleep may also influence the rhythms of the autonomic nervous system, and behavioral rhythms with regard to timing and/or amount of eating or exercise.

Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms driving the associations, the impact of sleep irregularity on individual CVD outcomes, and to determine whether a 7-day SD of more than 90 minutes for either sleep duration or sleep-onset timing can be used clinically as a threshold target for promoting cardiometabolically healthy sleep, Huang said.

“When providers communicate with their patients regarding strategies for CVD prevention, usually they focus on healthy diet and physical activity; and even when they talk about sleep, they talk about whether they have good sleep quality or sufficient sleep,” he said. “But one thing they should provide is advice regarding sleep regularity and [they should] recommend their patients follow a regular sleep pattern for the purpose of cardiovascular prevention.”

In a related editorial, Olaf Oldenburg, MD, Luderus-Kliniken Münster, Clemenshospital, Münster, Germany, and Jens Spiesshoefer, MD, Institute of Life Sciences, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy, write that the observed independent association between sleep irregularity and CVD “is a particularly striking finding given that impaired circadian rhythm is likely to be much more prevalent than the extreme example of shift work.”

They call on researchers to utilize big data to facilitate understanding of the association and say it is essential to test whether experimental data support the hypothesis that altered circadian rhythms would translate into unfavorable changes in 24-hour sympathovagal and neurohormonal balance, and ultimately CVD.

The present study “will, and should, stimulate much needed additional research on the association between sleep and CVD that may offer novel approaches to help improve the prognosis and daily symptom burden of patients with CVD, and might make sleep itself a therapeutic target in CVD,” the editorialists conclude.

This research was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The MESA Sleep Study was supported by an NHLBI grant. Huang was supported by a career development grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Krumholz and Oldenburg have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Spiesshoefer is supported by grants from the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung, the Innovative Medical Research program at the University of Münster, and Deutsche Herzstiftung; and by young investigator research support from Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa. He also has received travel grants and lecture honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi.

Source: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.054.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who frequently alter the amount of sleep and time they go to bed each night are twofold more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, independent of traditional CVD risk factors, new research suggests.

Prior studies have focused on shift workers because night shift work will influence circadian rhythm and increase CVD risk. But it is increasingly recognized that circadian disruption may occur outside of shift work and accumulate over time, particularly given modern lifestyle factors such as increased use of mobile devices and television at night, said study coauthor Tianyi Huang, ScD, MSc, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Even if they tend to go to sleep at certain times, by following that lifestyle or behavior, it can interfere with their planned sleep timing,” he said.

“One thing that surprised me in this sample is that about one third of participants have irregular sleep patterns that can put them at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. So I think the prevalence is higher than expected,” Huang added.

As reported today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators used data from 7-day wrist actigraphy, 1 night of at-home polysomnography, and sleep questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep-onset timing among 1,992 Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis () participants, aged 45 to 84 years, who were free of CVD and prospectively followed for a me MESA dian of 4.9 years.

A total of 786 patients (39.5%) had sleep duration standard deviation (SD) > 90 minutes and 510 (25.6%) had sleep-onset timing SD > 90 minutes.

During follow-up, there were 111 incident CVD events, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease death, stroke, and other coronary events.

Compared with people who had less than 1 hour of variation in sleep duration, the risk for incident CVD was 9% higher for people whose sleep duration varied 61 to 90 minutes (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 - 1.92), even after controlling for a variety of cardiovascular and sleep-related risk factors such as body mass index, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, total cholesterol, average sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep apnea.

Moreover, the adjusted CVD risk was substantially increased with 91 to 120 minutes of variation (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.91 - 2.76) and more than 120 minutes of variation in sleep duration (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.24 - 3.68).

Every 1-hour increase in sleep duration SD was associated with 36% higher CVD risk (95% CI; 1.07 - 1.73).

Compared with people with no more than a half hour of variation in nightly bedtimes, the adjusted hazard ratios for CVD were 1.16 (95% CI, 0.64 - 2.13), 1.52 (95% CI, 0.81 - 2.88), and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.13 - 3.91) when bedtimes varied by 31 to 60 minutes, 61 to 90 minutes, and more than 90 minutes.

For every 1-hour increase in sleep-onset timing SD, the risk of CVD was 18% higher (95% CI; 1.06 - 1.31).

“The results are similar for the regularity of sleep timing and the regularity of sleep duration, which means that both can contribute to circadian disruption and then lead to development of cardiovascular disease,” Huang said.

This is an important article and signals how sleep is an important marker and possibly a mediator of cardiovascular risk, said Harlan Krumholz, MD, of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not involved with the study.

“What I like about this is it’s a nice longitudinal, epidemiologic study with not just self-report, but sensor-detected sleep, that has been correlated with well-curated and adjudicated outcomes to give us a strong sense of this association,” he told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. “And also, that it goes beyond just the duration — they combine the duration and timing in order to give a fuller picture of sleep.”

Nevertheless, Krumholz said researchers are only at the beginning of being able to quantify the various dimensions of sleep and the degree to which sleep is a reflection of underlying physiologic issues, or whether patients are having erratic sleep patterns that are having a toxic effect on their overall health.

Questions also remain about the mechanism behind the association, whether the increased risk is universal or more harmful for some people, and the best way to measure factors during sleep that can most comprehensively and precisely predict risk.

“As we get more information flowing in from sensors, I think we will begin to develop more sophisticated approaches toward understanding risk, and it will be accompanied by other studies that will help us understand whether, again, this is a reflection of other processes that we should be paying attention to or whether it is a cause of disease and risk,” Krumholz said.

Subgroup analyses suggested positive associations between irregular sleep and CVD in African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans but not in whites. This could be because sleep irregularity, both timing and duration, was substantially higher in minorities, especially African Americans, but may also be as a result of chance because the study sample is relatively small, Huang explained.

The authors note that the overall findings are biologically plausible because of their previous work linking sleep irregularity with metabolic risk factors that predispose to atherosclerosis, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Participants with irregular sleep tended to have worse baseline cardiometabolic profiles, but this only explained a small portion of the associations between sleep irregularity and CVD, they note.

Other possible explanations include circadian clock genes, such as clock, per2 and bmal1, which have been shown experimentally to control a broad range of cardiovascular functions, from blood pressure and endothelial functions to vascular thrombosis and cardiac remodeling.

Irregular sleep may also influence the rhythms of the autonomic nervous system, and behavioral rhythms with regard to timing and/or amount of eating or exercise.

Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms driving the associations, the impact of sleep irregularity on individual CVD outcomes, and to determine whether a 7-day SD of more than 90 minutes for either sleep duration or sleep-onset timing can be used clinically as a threshold target for promoting cardiometabolically healthy sleep, Huang said.

“When providers communicate with their patients regarding strategies for CVD prevention, usually they focus on healthy diet and physical activity; and even when they talk about sleep, they talk about whether they have good sleep quality or sufficient sleep,” he said. “But one thing they should provide is advice regarding sleep regularity and [they should] recommend their patients follow a regular sleep pattern for the purpose of cardiovascular prevention.”

In a related editorial, Olaf Oldenburg, MD, Luderus-Kliniken Münster, Clemenshospital, Münster, Germany, and Jens Spiesshoefer, MD, Institute of Life Sciences, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy, write that the observed independent association between sleep irregularity and CVD “is a particularly striking finding given that impaired circadian rhythm is likely to be much more prevalent than the extreme example of shift work.”

They call on researchers to utilize big data to facilitate understanding of the association and say it is essential to test whether experimental data support the hypothesis that altered circadian rhythms would translate into unfavorable changes in 24-hour sympathovagal and neurohormonal balance, and ultimately CVD.

The present study “will, and should, stimulate much needed additional research on the association between sleep and CVD that may offer novel approaches to help improve the prognosis and daily symptom burden of patients with CVD, and might make sleep itself a therapeutic target in CVD,” the editorialists conclude.

This research was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The MESA Sleep Study was supported by an NHLBI grant. Huang was supported by a career development grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Krumholz and Oldenburg have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Spiesshoefer is supported by grants from the Else-Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung, the Innovative Medical Research program at the University of Münster, and Deutsche Herzstiftung; and by young investigator research support from Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa. He also has received travel grants and lecture honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi.

Source: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 2. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.054.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who frequently alter the amount of sleep and time they go to bed each night are twofold more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, independent of traditional CVD risk factors, new research suggests.

Prior studies have focused on shift workers because night shift work will influence circadian rhythm and increase CVD risk. But it is increasingly recognized that circadian disruption may occur outside of shift work and accumulate over time, particularly given modern lifestyle factors such as increased use of mobile devices and television at night, said study coauthor Tianyi Huang, ScD, MSc, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Even if they tend to go to sleep at certain times, by following that lifestyle or behavior, it can interfere with their planned sleep timing,” he said.

“One thing that surprised me in this sample is that about one third of participants have irregular sleep patterns that can put them at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. So I think the prevalence is higher than expected,” Huang added.

As reported today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators used data from 7-day wrist actigraphy, 1 night of at-home polysomnography, and sleep questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep-onset timing among 1,992 Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis () participants, aged 45 to 84 years, who were free of CVD and prospectively followed for a me MESA dian of 4.9 years.

A total of 786 patients (39.5%) had sleep duration standard deviation (SD) > 90 minutes and 510 (25.6%) had sleep-onset timing SD > 90 minutes.

During follow-up, there were 111 incident CVD events, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease death, stroke, and other coronary events.

Compared with people who had less than 1 hour of variation in sleep duration, the risk for incident CVD was 9% higher for people whose sleep duration varied 61 to 90 minutes (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 - 1.92), even after controlling for a variety of cardiovascular and sleep-related risk factors such as body mass index, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, total cholesterol, average sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and sleep apnea.

Moreover, the adjusted CVD risk was substantially increased with 91 to 120 minutes of variation (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.91 - 2.76) and more than 120 minutes of variation in sleep duration (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.24 - 3.68).

Every 1-hour increase in sleep duration SD was associated with 36% higher CVD risk (95% CI; 1.07 - 1.73).

Compared with people with no more than a half hour of variation in nightly bedtimes, the adjusted hazard ratios for CVD were 1.16 (95% CI, 0.64 - 2.13), 1.52 (95% CI, 0.81 - 2.88), and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.13 - 3.91) when bedtimes varied by 31 to 60 minutes, 61 to 90 minutes, and more than 90 minutes.

For every 1-hour increase in sleep-onset timing SD, the risk of CVD was 18% higher (95% CI; 1.06 - 1.31).

“The results are similar for the regularity of sleep timing and the regularity of sleep duration, which means that both can contribute to circadian disruption and then lead to development of cardiovascular disease,” Huang said.

This is an important article and signals how sleep is an important marker and possibly a mediator of cardiovascular risk, said Harlan Krumholz, MD, of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not involved with the study.

“What I like about this is it’s a nice longitudinal, epidemiologic study with not just self-report, but sensor-detected sleep, that has been correlated with well-curated and adjudicated outcomes to give us a strong sense of this association,” he told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. “And also, that it goes beyond just the duration — they combine the duration and timing in order to give a fuller picture of sleep.”

Nevertheless, Krumholz said researchers are only at the beginning of being able to quantify the various dimensions of sleep and the degree to which sleep is a reflection of underlying physiologic issues, or whether patients are having erratic sleep patterns that are having a toxic effect on their overall health.

Questions also remain about the mechanism behind the association, whether the increased risk is universal or more harmful for some people, and the best way to measure factors during sleep that can most comprehensively and precisely predict risk.

“As we get more information flowing in from sensors, I think we will begin to develop more sophisticated approaches toward understanding risk, and it will be accompanied by other studies that will help us understand whether, again, this is a reflection of other processes that we should be paying attention to or whether it is a cause of disease and risk,” Krumholz said.