User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

HIV does not appear to worsen COVID-19 outcomes

People living with HIV who are admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 are no more likely to die than those without HIV, an analysis conducted in New York City shows. This is despite the fact that comorbidities associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes were more common in the HIV group.

“We don’t see any signs that people with HIV should take extra precautions” to protect themselves from COVID-19, said Keith Sigel, MD, associate professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and the lead researcher on the study, published online June 28 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“We still don’t have a great explanation for why we’re seeing what we’re seeing,” he added. “But we’re glad we’re seeing it.”

The findings have changed how Dr. Sigel talks to his patients with HIV about protecting themselves from COVID-19. Some patients have so curtailed their behavior for fear of acquiring COVID-19 that they aren’t buying groceries or attending needed medical appointments. With these data, Dr. Sigel said he’s comfortable telling his patients, “COVID-19 is bad all by itself, but you don’t need to go crazy. Wear a mask, practice appropriate social distancing and hygiene, but your risk doesn’t appear to be greater.”

The findings conform with those on the lack of association between HIV and COVID-19 severity seen in a cohort study from Spain, a case study from China, and case series from New Jersey, New York City, and Spain.

One of the only regions reporting something different so far is South Africa. There, HIV is the third most common comorbidity associated with death from COVID-19, according to a cohort analysis conducted in the province of Western Cape.

Along with data from HIV prevention and treatment trials, the conference will feature updates on where the world stands in the control of HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. And for an even more focused look, the IAS COVID-19 Conference will immediately follow that meeting.

The New York City cohort

For their study, Dr. Sigel and colleagues examined the 4402 COVID-19 cases at the Mount Sinai Health System’s five hospitals between March 12 and April 23.

They found 88 people with COVID-19 whose charts showed codes indicating they were living with HIV. All 88 were receiving treatment, and 81% of them had undetectable viral loads documented at COVID admission or in the 12 months prior to admission.

The median age was 61 years, and 40% of the cohort was black and 30% was Hispanic.

Patients in the comparison group – 405 people without HIV from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study who had been admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 – were matched in terms of age, race, and stage of COVID-19.

The study had an 80% power to detect a 15% increase in the absolute risk for death in people with COVID-19, with or without HIV.

Patients with HIV were almost three times as likely to have smoked and were more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, and a history of cancer.

“This was a group of patients that one might suspect would do worse,” Dr. Sigel said. And yet, “we didn’t see any difference in deaths. We didn’t see any difference in respiratory failure.”

In fact, people with HIV required mechanical ventilation less often than those without HIV (18% vs. 23%). And when it came to mortality, one in five people died from COVID-19 during follow-up whether they had HIV or not (21% vs. 20%).

The only factor associated with significantly worse outcomes was a history of organ transplantation, “suggesting that non-HIV causes of immunodeficiency may be more prominent risks for severe outcomes,” Dr. Sigel and colleagues explained.

A surprise association

What’s more, the researchers found a slight association between the use of nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) by people with HIV and better outcomes in COVID-19. That echoes findings published June 26 in Annals of Internal Medicine, which showed that people with HIV taking the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine (Truvada, Gilead Sciences) were less likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19, less likely to be hospitalized, and less likely to die.

This has led some to wonder whether NRTIs have some effect on SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Dr. Sigel said he wonders that too, but right now, it’s just musings.

“These studies are not even remotely designed” to show that NRTIs are protective against COVID-19, he explained. “Ours was extremely underpowered to detect that and there was a high potential for confounding.”

“I’d be wary of any study in a subpopulation – which is what we’re dealing with here – that is looking for signals of protection with certain medications,” he added.

A “modest” increase

Using the South African data, released on June 22, public health officials estimate that people with HIV are 2.75 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than those without HIV, making it the third most common comorbidity in people who died from COVID-19, behind diabetes and hypertension. This held true regardless of whether the people with HIV were on treatment.

But when they looked at COVID-19 deaths in the sickest of the sick – those hospitalized with COVID-19 symptoms – HIV was associated with just a 28% increase in the risk for death. The South African researchers called this risk “modest.”

“While these findings may overestimate the effect of HIV on COVID-19 death due to the presence of residual confounding, people living with HIV should be considered a high-risk group for COVID-19 management, with modestly elevated risk of poor outcomes, irrespective of viral suppression,” they wrote.

Epidemiologist Gregorio Millett, MPH, has been tracking the effect of HIV on COVID-19 outcomes since the start of the pandemic in his role as vice president and head of policy at the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amFAR).

Back in April, he and his colleagues looked at rates of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations in counties with disproportionate levels of black residents. These areas often overlapped with the communities selected for the Ending the HIV Epidemic plan to control HIV by 2030. What they found was that there was more HIV and COVID-19 in those communities.

What they didn’t find was that people with HIV in those communities had worse outcomes with COVID-19. This remained true even when they reran the analysis after the number of cases of COVID-19 in the United States surpassed 100,000. Those data have yet to be published, Mr. Millett reported.

“HIV does not pop out,” he said. “It’s still social determinants of health. It’s still underlying conditions. It’s still age as a primary factor.”

“People living with HIV are mainly dying of underlying conditions – so all the things associated with COVID-19 – rather than the association being with HIV itself,” he added.

Although he’s not ruling out the possibility that an association like the one in South Africa could emerge, Mr. Millett, who will present a plenary on the context of the HIV epidemic at the IAS conference, said he suspects we won’t see one.

“If we didn’t see an association with the counties that are disproportionately African American, in the black belt where we see high rates of HIV, particularly where we see the social determinants of health that definitely make a difference – if we’re not seeing that association there, where we have a high proportion of African Americans who are at risk both for HIV and COVID-19 – I just don’t think it’s going to emerge,” he said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People living with HIV who are admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 are no more likely to die than those without HIV, an analysis conducted in New York City shows. This is despite the fact that comorbidities associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes were more common in the HIV group.

“We don’t see any signs that people with HIV should take extra precautions” to protect themselves from COVID-19, said Keith Sigel, MD, associate professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and the lead researcher on the study, published online June 28 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“We still don’t have a great explanation for why we’re seeing what we’re seeing,” he added. “But we’re glad we’re seeing it.”

The findings have changed how Dr. Sigel talks to his patients with HIV about protecting themselves from COVID-19. Some patients have so curtailed their behavior for fear of acquiring COVID-19 that they aren’t buying groceries or attending needed medical appointments. With these data, Dr. Sigel said he’s comfortable telling his patients, “COVID-19 is bad all by itself, but you don’t need to go crazy. Wear a mask, practice appropriate social distancing and hygiene, but your risk doesn’t appear to be greater.”

The findings conform with those on the lack of association between HIV and COVID-19 severity seen in a cohort study from Spain, a case study from China, and case series from New Jersey, New York City, and Spain.

One of the only regions reporting something different so far is South Africa. There, HIV is the third most common comorbidity associated with death from COVID-19, according to a cohort analysis conducted in the province of Western Cape.

Along with data from HIV prevention and treatment trials, the conference will feature updates on where the world stands in the control of HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. And for an even more focused look, the IAS COVID-19 Conference will immediately follow that meeting.

The New York City cohort

For their study, Dr. Sigel and colleagues examined the 4402 COVID-19 cases at the Mount Sinai Health System’s five hospitals between March 12 and April 23.

They found 88 people with COVID-19 whose charts showed codes indicating they were living with HIV. All 88 were receiving treatment, and 81% of them had undetectable viral loads documented at COVID admission or in the 12 months prior to admission.

The median age was 61 years, and 40% of the cohort was black and 30% was Hispanic.

Patients in the comparison group – 405 people without HIV from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study who had been admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 – were matched in terms of age, race, and stage of COVID-19.

The study had an 80% power to detect a 15% increase in the absolute risk for death in people with COVID-19, with or without HIV.

Patients with HIV were almost three times as likely to have smoked and were more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, and a history of cancer.

“This was a group of patients that one might suspect would do worse,” Dr. Sigel said. And yet, “we didn’t see any difference in deaths. We didn’t see any difference in respiratory failure.”

In fact, people with HIV required mechanical ventilation less often than those without HIV (18% vs. 23%). And when it came to mortality, one in five people died from COVID-19 during follow-up whether they had HIV or not (21% vs. 20%).

The only factor associated with significantly worse outcomes was a history of organ transplantation, “suggesting that non-HIV causes of immunodeficiency may be more prominent risks for severe outcomes,” Dr. Sigel and colleagues explained.

A surprise association

What’s more, the researchers found a slight association between the use of nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) by people with HIV and better outcomes in COVID-19. That echoes findings published June 26 in Annals of Internal Medicine, which showed that people with HIV taking the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine (Truvada, Gilead Sciences) were less likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19, less likely to be hospitalized, and less likely to die.

This has led some to wonder whether NRTIs have some effect on SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Dr. Sigel said he wonders that too, but right now, it’s just musings.

“These studies are not even remotely designed” to show that NRTIs are protective against COVID-19, he explained. “Ours was extremely underpowered to detect that and there was a high potential for confounding.”

“I’d be wary of any study in a subpopulation – which is what we’re dealing with here – that is looking for signals of protection with certain medications,” he added.

A “modest” increase

Using the South African data, released on June 22, public health officials estimate that people with HIV are 2.75 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than those without HIV, making it the third most common comorbidity in people who died from COVID-19, behind diabetes and hypertension. This held true regardless of whether the people with HIV were on treatment.

But when they looked at COVID-19 deaths in the sickest of the sick – those hospitalized with COVID-19 symptoms – HIV was associated with just a 28% increase in the risk for death. The South African researchers called this risk “modest.”

“While these findings may overestimate the effect of HIV on COVID-19 death due to the presence of residual confounding, people living with HIV should be considered a high-risk group for COVID-19 management, with modestly elevated risk of poor outcomes, irrespective of viral suppression,” they wrote.

Epidemiologist Gregorio Millett, MPH, has been tracking the effect of HIV on COVID-19 outcomes since the start of the pandemic in his role as vice president and head of policy at the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amFAR).

Back in April, he and his colleagues looked at rates of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations in counties with disproportionate levels of black residents. These areas often overlapped with the communities selected for the Ending the HIV Epidemic plan to control HIV by 2030. What they found was that there was more HIV and COVID-19 in those communities.

What they didn’t find was that people with HIV in those communities had worse outcomes with COVID-19. This remained true even when they reran the analysis after the number of cases of COVID-19 in the United States surpassed 100,000. Those data have yet to be published, Mr. Millett reported.

“HIV does not pop out,” he said. “It’s still social determinants of health. It’s still underlying conditions. It’s still age as a primary factor.”

“People living with HIV are mainly dying of underlying conditions – so all the things associated with COVID-19 – rather than the association being with HIV itself,” he added.

Although he’s not ruling out the possibility that an association like the one in South Africa could emerge, Mr. Millett, who will present a plenary on the context of the HIV epidemic at the IAS conference, said he suspects we won’t see one.

“If we didn’t see an association with the counties that are disproportionately African American, in the black belt where we see high rates of HIV, particularly where we see the social determinants of health that definitely make a difference – if we’re not seeing that association there, where we have a high proportion of African Americans who are at risk both for HIV and COVID-19 – I just don’t think it’s going to emerge,” he said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People living with HIV who are admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 are no more likely to die than those without HIV, an analysis conducted in New York City shows. This is despite the fact that comorbidities associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes were more common in the HIV group.

“We don’t see any signs that people with HIV should take extra precautions” to protect themselves from COVID-19, said Keith Sigel, MD, associate professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and the lead researcher on the study, published online June 28 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“We still don’t have a great explanation for why we’re seeing what we’re seeing,” he added. “But we’re glad we’re seeing it.”

The findings have changed how Dr. Sigel talks to his patients with HIV about protecting themselves from COVID-19. Some patients have so curtailed their behavior for fear of acquiring COVID-19 that they aren’t buying groceries or attending needed medical appointments. With these data, Dr. Sigel said he’s comfortable telling his patients, “COVID-19 is bad all by itself, but you don’t need to go crazy. Wear a mask, practice appropriate social distancing and hygiene, but your risk doesn’t appear to be greater.”

The findings conform with those on the lack of association between HIV and COVID-19 severity seen in a cohort study from Spain, a case study from China, and case series from New Jersey, New York City, and Spain.

One of the only regions reporting something different so far is South Africa. There, HIV is the third most common comorbidity associated with death from COVID-19, according to a cohort analysis conducted in the province of Western Cape.

Along with data from HIV prevention and treatment trials, the conference will feature updates on where the world stands in the control of HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. And for an even more focused look, the IAS COVID-19 Conference will immediately follow that meeting.

The New York City cohort

For their study, Dr. Sigel and colleagues examined the 4402 COVID-19 cases at the Mount Sinai Health System’s five hospitals between March 12 and April 23.

They found 88 people with COVID-19 whose charts showed codes indicating they were living with HIV. All 88 were receiving treatment, and 81% of them had undetectable viral loads documented at COVID admission or in the 12 months prior to admission.

The median age was 61 years, and 40% of the cohort was black and 30% was Hispanic.

Patients in the comparison group – 405 people without HIV from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study who had been admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 – were matched in terms of age, race, and stage of COVID-19.

The study had an 80% power to detect a 15% increase in the absolute risk for death in people with COVID-19, with or without HIV.

Patients with HIV were almost three times as likely to have smoked and were more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, and a history of cancer.

“This was a group of patients that one might suspect would do worse,” Dr. Sigel said. And yet, “we didn’t see any difference in deaths. We didn’t see any difference in respiratory failure.”

In fact, people with HIV required mechanical ventilation less often than those without HIV (18% vs. 23%). And when it came to mortality, one in five people died from COVID-19 during follow-up whether they had HIV or not (21% vs. 20%).

The only factor associated with significantly worse outcomes was a history of organ transplantation, “suggesting that non-HIV causes of immunodeficiency may be more prominent risks for severe outcomes,” Dr. Sigel and colleagues explained.

A surprise association

What’s more, the researchers found a slight association between the use of nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) by people with HIV and better outcomes in COVID-19. That echoes findings published June 26 in Annals of Internal Medicine, which showed that people with HIV taking the combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine (Truvada, Gilead Sciences) were less likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19, less likely to be hospitalized, and less likely to die.

This has led some to wonder whether NRTIs have some effect on SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Dr. Sigel said he wonders that too, but right now, it’s just musings.

“These studies are not even remotely designed” to show that NRTIs are protective against COVID-19, he explained. “Ours was extremely underpowered to detect that and there was a high potential for confounding.”

“I’d be wary of any study in a subpopulation – which is what we’re dealing with here – that is looking for signals of protection with certain medications,” he added.

A “modest” increase

Using the South African data, released on June 22, public health officials estimate that people with HIV are 2.75 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than those without HIV, making it the third most common comorbidity in people who died from COVID-19, behind diabetes and hypertension. This held true regardless of whether the people with HIV were on treatment.

But when they looked at COVID-19 deaths in the sickest of the sick – those hospitalized with COVID-19 symptoms – HIV was associated with just a 28% increase in the risk for death. The South African researchers called this risk “modest.”

“While these findings may overestimate the effect of HIV on COVID-19 death due to the presence of residual confounding, people living with HIV should be considered a high-risk group for COVID-19 management, with modestly elevated risk of poor outcomes, irrespective of viral suppression,” they wrote.

Epidemiologist Gregorio Millett, MPH, has been tracking the effect of HIV on COVID-19 outcomes since the start of the pandemic in his role as vice president and head of policy at the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amFAR).

Back in April, he and his colleagues looked at rates of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations in counties with disproportionate levels of black residents. These areas often overlapped with the communities selected for the Ending the HIV Epidemic plan to control HIV by 2030. What they found was that there was more HIV and COVID-19 in those communities.

What they didn’t find was that people with HIV in those communities had worse outcomes with COVID-19. This remained true even when they reran the analysis after the number of cases of COVID-19 in the United States surpassed 100,000. Those data have yet to be published, Mr. Millett reported.

“HIV does not pop out,” he said. “It’s still social determinants of health. It’s still underlying conditions. It’s still age as a primary factor.”

“People living with HIV are mainly dying of underlying conditions – so all the things associated with COVID-19 – rather than the association being with HIV itself,” he added.

Although he’s not ruling out the possibility that an association like the one in South Africa could emerge, Mr. Millett, who will present a plenary on the context of the HIV epidemic at the IAS conference, said he suspects we won’t see one.

“If we didn’t see an association with the counties that are disproportionately African American, in the black belt where we see high rates of HIV, particularly where we see the social determinants of health that definitely make a difference – if we’re not seeing that association there, where we have a high proportion of African Americans who are at risk both for HIV and COVID-19 – I just don’t think it’s going to emerge,” he said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AIDS 2020

Inhaled treprostinil improves walk distance in patients with ILD-associated pulmonary hypertension

over 16 weeks, compared with patients who used a placebo inhaler, results of a phase 3 trial showed.

Among 326 patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) associated with interstitial lung disease (ILD), those who were randomly assigned to treatment with treprostinil had a placebo-corrected median difference from baseline in 6-minute walk distance of 21 m (P = .004), reported Steven D. Nathan, MD, from Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., on behalf of coinvestigators in the INCREASE study (NCT02630316).

“These results support an additional treatment avenue, and might herald a shift in the clinical management of patients with interstitial lung disease,” he said in the American Thoracic Society’s virtual clinical trial session.

“This was an outstanding presentation and outstanding results. I personally am very excited, because this is a field where I work,” commented Martin Kolb, MD, PhD, from McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., the facilitator for the online presentation.

The INCREASE trial compared inhaled treprostinil dose four times daily with placebo in patients with a CT scan–confirmed diagnosis of World Health Organization group 3 PH within 6 months before randomization who had evidence of diffuse parenchymal lung disease. Eligible patients could have any form of ILD or combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema.

Key inclusion criteria included right-heart catheterization within the previous year with documented pulmonary vascular resistance greater than 3 Wood units, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less, and mean pulmonary arterial pressure 25 mm Hg or higher.

Patients also had to have a 6-minute walk distance of at least 100 m and have stable disease while on an optimized dose of medications for underlying lung disease. Patients with group 3 connective tissue disease had to have baseline forced vital capacity of less than 70%.

The final study cohorts included patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, connective tissue disease, combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, and occupational lung disease.

The patients were randomized to receive either inhaled treprostinil at a starting dose of 6 mcg/breath four times daily or to placebo (163 patients in each arm). All patients started the study drug at a dose of three breaths four times daily during waking hours. Dose escalations – adding 1 additional breath four times daily – were allowed every 3 days, up to a target dose of 9 breaths (54 mcg) four times daily, and a maximum of 12 breaths (72 mcg) four times daily as clinically tolerated.

A total of 130 patients assigned to treprostinil and 128 assigned to placebo completed 16 weeks of therapy and assessment.

As noted before, patients assigned to treprostinil had a placebo-corrected median difference from baseline in peak 6-minute walk distance, as measured by Hodges-Lehmann estimation, of 21 m (P = .004). An analysis of the same parameter using mixed model repeated measurement showed a placebo-corrected difference from baseline in peak 6-minute walk distance of 31.12 m (P < .001).

Secondary endpoints that were significantly better with treprostinil, compared with placebo, included improvements in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, a longer time to clinical worsening, and improvements in peak 6-minute walk distance week 12, and trough 6-minute walk distance at week 15.

Treprostinil was associated with a 39% reduction in risk of clinical worsening (P = .04). In all, 37 patients on treprostinil (22.7%) and 54 on placebo (33.1%) experienced clinical worsening.

For the exploratory endpoints of change in patient reported quality of life as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, or in peak distance saturation product, however, there were no significant differences between the groups.

In addition, treprostinil was associated with a 34% reduction the risk of exacerbation of underlying lung disease, compared with placebo (P = .03).

The safety profile of treprostinil was similar to that seen in other studies of the drug, and most treatment-related adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Adverse events led to discontinuation in 10% of patients on treprostinil and 8% on placebo.

Serious adverse events were seen in 23.3% and 25.8%, respectively. The most frequently occurring adverse events of any grade included cough, headache, dyspnea, dizziness, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, throat irritation, and oropharyngeal pain.

There was no evidence of worsened oxygenation or lung function “allaying V/Q mismatch concerns,” Dr. Nathan said, and there was evidence for an improvement in forced vital capacity with treprostinil.

In the question-and-answer portion of the presentation, Dr. Kolb commented that many clinicians, particularly those who treated patients with ILD, question whether a 21-m difference in walk distance makes much of a difference in patient lives. He relayed a question from a viewer asking how Dr. Nathan and associates reconciled their primary endpoint with the finding that there was no difference in patient-reported quality of life.

“I think that the difference in the 6-minute walk test was both statistically significant and clinically meaningful,” Dr. Nathan replied.

He noted that the primary endpoint used a stringent measure, and that less conservative methods of analysis showed a larger difference in benefit favoring treprostinil. He also pointed out that the original study of inhaled treprostinil added to oral therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension showed a 20-m improvement in walk distance, and that these results were sufficient to get the inhaled formulation approved in the United States (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.027).

Regarding the failure to detect a difference in quality of life, he said that the study was only 16 weeks in length, and that the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire was developed for evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, “perhaps not the best instrument to use in an ILD PH study.”

The study was funded by United Therapeutics. Dr. Nathan disclosed advisory committee activity/consulting, research support, and speaker fees from the company. Dr. Kolb has previously disclosed financial relationships with various companies, not including United Therapeutics.

over 16 weeks, compared with patients who used a placebo inhaler, results of a phase 3 trial showed.

Among 326 patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) associated with interstitial lung disease (ILD), those who were randomly assigned to treatment with treprostinil had a placebo-corrected median difference from baseline in 6-minute walk distance of 21 m (P = .004), reported Steven D. Nathan, MD, from Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., on behalf of coinvestigators in the INCREASE study (NCT02630316).

“These results support an additional treatment avenue, and might herald a shift in the clinical management of patients with interstitial lung disease,” he said in the American Thoracic Society’s virtual clinical trial session.

“This was an outstanding presentation and outstanding results. I personally am very excited, because this is a field where I work,” commented Martin Kolb, MD, PhD, from McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., the facilitator for the online presentation.

The INCREASE trial compared inhaled treprostinil dose four times daily with placebo in patients with a CT scan–confirmed diagnosis of World Health Organization group 3 PH within 6 months before randomization who had evidence of diffuse parenchymal lung disease. Eligible patients could have any form of ILD or combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema.

Key inclusion criteria included right-heart catheterization within the previous year with documented pulmonary vascular resistance greater than 3 Wood units, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less, and mean pulmonary arterial pressure 25 mm Hg or higher.

Patients also had to have a 6-minute walk distance of at least 100 m and have stable disease while on an optimized dose of medications for underlying lung disease. Patients with group 3 connective tissue disease had to have baseline forced vital capacity of less than 70%.

The final study cohorts included patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, connective tissue disease, combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, and occupational lung disease.

The patients were randomized to receive either inhaled treprostinil at a starting dose of 6 mcg/breath four times daily or to placebo (163 patients in each arm). All patients started the study drug at a dose of three breaths four times daily during waking hours. Dose escalations – adding 1 additional breath four times daily – were allowed every 3 days, up to a target dose of 9 breaths (54 mcg) four times daily, and a maximum of 12 breaths (72 mcg) four times daily as clinically tolerated.

A total of 130 patients assigned to treprostinil and 128 assigned to placebo completed 16 weeks of therapy and assessment.

As noted before, patients assigned to treprostinil had a placebo-corrected median difference from baseline in peak 6-minute walk distance, as measured by Hodges-Lehmann estimation, of 21 m (P = .004). An analysis of the same parameter using mixed model repeated measurement showed a placebo-corrected difference from baseline in peak 6-minute walk distance of 31.12 m (P < .001).

Secondary endpoints that were significantly better with treprostinil, compared with placebo, included improvements in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, a longer time to clinical worsening, and improvements in peak 6-minute walk distance week 12, and trough 6-minute walk distance at week 15.

Treprostinil was associated with a 39% reduction in risk of clinical worsening (P = .04). In all, 37 patients on treprostinil (22.7%) and 54 on placebo (33.1%) experienced clinical worsening.

For the exploratory endpoints of change in patient reported quality of life as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, or in peak distance saturation product, however, there were no significant differences between the groups.

In addition, treprostinil was associated with a 34% reduction the risk of exacerbation of underlying lung disease, compared with placebo (P = .03).

The safety profile of treprostinil was similar to that seen in other studies of the drug, and most treatment-related adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Adverse events led to discontinuation in 10% of patients on treprostinil and 8% on placebo.

Serious adverse events were seen in 23.3% and 25.8%, respectively. The most frequently occurring adverse events of any grade included cough, headache, dyspnea, dizziness, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, throat irritation, and oropharyngeal pain.

There was no evidence of worsened oxygenation or lung function “allaying V/Q mismatch concerns,” Dr. Nathan said, and there was evidence for an improvement in forced vital capacity with treprostinil.

In the question-and-answer portion of the presentation, Dr. Kolb commented that many clinicians, particularly those who treated patients with ILD, question whether a 21-m difference in walk distance makes much of a difference in patient lives. He relayed a question from a viewer asking how Dr. Nathan and associates reconciled their primary endpoint with the finding that there was no difference in patient-reported quality of life.

“I think that the difference in the 6-minute walk test was both statistically significant and clinically meaningful,” Dr. Nathan replied.

He noted that the primary endpoint used a stringent measure, and that less conservative methods of analysis showed a larger difference in benefit favoring treprostinil. He also pointed out that the original study of inhaled treprostinil added to oral therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension showed a 20-m improvement in walk distance, and that these results were sufficient to get the inhaled formulation approved in the United States (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.027).

Regarding the failure to detect a difference in quality of life, he said that the study was only 16 weeks in length, and that the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire was developed for evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, “perhaps not the best instrument to use in an ILD PH study.”

The study was funded by United Therapeutics. Dr. Nathan disclosed advisory committee activity/consulting, research support, and speaker fees from the company. Dr. Kolb has previously disclosed financial relationships with various companies, not including United Therapeutics.

over 16 weeks, compared with patients who used a placebo inhaler, results of a phase 3 trial showed.

Among 326 patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) associated with interstitial lung disease (ILD), those who were randomly assigned to treatment with treprostinil had a placebo-corrected median difference from baseline in 6-minute walk distance of 21 m (P = .004), reported Steven D. Nathan, MD, from Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., on behalf of coinvestigators in the INCREASE study (NCT02630316).

“These results support an additional treatment avenue, and might herald a shift in the clinical management of patients with interstitial lung disease,” he said in the American Thoracic Society’s virtual clinical trial session.

“This was an outstanding presentation and outstanding results. I personally am very excited, because this is a field where I work,” commented Martin Kolb, MD, PhD, from McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., the facilitator for the online presentation.

The INCREASE trial compared inhaled treprostinil dose four times daily with placebo in patients with a CT scan–confirmed diagnosis of World Health Organization group 3 PH within 6 months before randomization who had evidence of diffuse parenchymal lung disease. Eligible patients could have any form of ILD or combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema.

Key inclusion criteria included right-heart catheterization within the previous year with documented pulmonary vascular resistance greater than 3 Wood units, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less, and mean pulmonary arterial pressure 25 mm Hg or higher.

Patients also had to have a 6-minute walk distance of at least 100 m and have stable disease while on an optimized dose of medications for underlying lung disease. Patients with group 3 connective tissue disease had to have baseline forced vital capacity of less than 70%.

The final study cohorts included patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, connective tissue disease, combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, and occupational lung disease.

The patients were randomized to receive either inhaled treprostinil at a starting dose of 6 mcg/breath four times daily or to placebo (163 patients in each arm). All patients started the study drug at a dose of three breaths four times daily during waking hours. Dose escalations – adding 1 additional breath four times daily – were allowed every 3 days, up to a target dose of 9 breaths (54 mcg) four times daily, and a maximum of 12 breaths (72 mcg) four times daily as clinically tolerated.

A total of 130 patients assigned to treprostinil and 128 assigned to placebo completed 16 weeks of therapy and assessment.

As noted before, patients assigned to treprostinil had a placebo-corrected median difference from baseline in peak 6-minute walk distance, as measured by Hodges-Lehmann estimation, of 21 m (P = .004). An analysis of the same parameter using mixed model repeated measurement showed a placebo-corrected difference from baseline in peak 6-minute walk distance of 31.12 m (P < .001).

Secondary endpoints that were significantly better with treprostinil, compared with placebo, included improvements in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, a longer time to clinical worsening, and improvements in peak 6-minute walk distance week 12, and trough 6-minute walk distance at week 15.

Treprostinil was associated with a 39% reduction in risk of clinical worsening (P = .04). In all, 37 patients on treprostinil (22.7%) and 54 on placebo (33.1%) experienced clinical worsening.

For the exploratory endpoints of change in patient reported quality of life as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, or in peak distance saturation product, however, there were no significant differences between the groups.

In addition, treprostinil was associated with a 34% reduction the risk of exacerbation of underlying lung disease, compared with placebo (P = .03).

The safety profile of treprostinil was similar to that seen in other studies of the drug, and most treatment-related adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Adverse events led to discontinuation in 10% of patients on treprostinil and 8% on placebo.

Serious adverse events were seen in 23.3% and 25.8%, respectively. The most frequently occurring adverse events of any grade included cough, headache, dyspnea, dizziness, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, throat irritation, and oropharyngeal pain.

There was no evidence of worsened oxygenation or lung function “allaying V/Q mismatch concerns,” Dr. Nathan said, and there was evidence for an improvement in forced vital capacity with treprostinil.

In the question-and-answer portion of the presentation, Dr. Kolb commented that many clinicians, particularly those who treated patients with ILD, question whether a 21-m difference in walk distance makes much of a difference in patient lives. He relayed a question from a viewer asking how Dr. Nathan and associates reconciled their primary endpoint with the finding that there was no difference in patient-reported quality of life.

“I think that the difference in the 6-minute walk test was both statistically significant and clinically meaningful,” Dr. Nathan replied.

He noted that the primary endpoint used a stringent measure, and that less conservative methods of analysis showed a larger difference in benefit favoring treprostinil. He also pointed out that the original study of inhaled treprostinil added to oral therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension showed a 20-m improvement in walk distance, and that these results were sufficient to get the inhaled formulation approved in the United States (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.027).

Regarding the failure to detect a difference in quality of life, he said that the study was only 16 weeks in length, and that the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire was developed for evaluation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, “perhaps not the best instrument to use in an ILD PH study.”

The study was funded by United Therapeutics. Dr. Nathan disclosed advisory committee activity/consulting, research support, and speaker fees from the company. Dr. Kolb has previously disclosed financial relationships with various companies, not including United Therapeutics.

FROM ATS 2020

Pulmonary function tests can’t substitute for high-resolution CT in early systemic sclerosis ILD screening

Clinicians shouldn’t rely on pulmonary function tests (PFTs) alone to screen for interstitial lung disease (ILD). The tests performed poorly in a retrospective study of 212 patients with systemic sclerosis, reinforcing the findings of previous studies.

Any screening algorithm should include high-resolution CT (HRCT), which is good at prognosticating disease, the investigators wrote in Arthritis & Rheumatology. “I think all newly diagnosed systemic sclerosis patients should have a full set of PFTs (spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusion capacity) and an HRCT at baseline to evaluate for ILD,” the study’s lead author, Elana J. Bernstein, MD, said in an interview.

ILD is a leading cause of death in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients, affecting 40%-60% of those with the disease. HRCT is currently the preferred option for detection of ILD. PFTs are commonly used to screen for ILD but haven’t performed well in previous studies. “Someone can have abnormalities on HRCT that are consistent with ILD but still have PFTs that are in the ‘normal’ range,” explained Dr. Bernstein of Columbia University, New York. One cross-sectional study of 102 SSc patients found that the test’s sensitivity for the detection of ILD on HRCT was just 37.5% when forced vital capacity (FVC) <80% predicted.

Investigators sought to assess performance characteristics of PFTs in patients with early diffuse cutaneous SSc, a cohort at high risk of developing ILD. The study enlisted patients from the Prospective Registry of Early Systemic Sclerosis (PRESS), a multicenter, prospective cohort study of adults with early diffuse cutaneous SSc. Overall, 212 patients at 11 U.S. academic medical centers participated in the study from April 2012 to January 2019.

All patients had spirometry (PFT) and HRCT chest scans. PFTs were conducted per American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines. The investigators calculated test characteristics for single PFT and combinations of PFT parameters for the detection of ILD on HRCT. The HRCTs were ordered at the discretion of treating physicians, and scrutinized for ILD features such as reticular changes, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and ground-glass opacities. The investigators defined the lower limit of normal for FVC, total lung capacity, and diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) as 80% predicted.

Overall, Dr. Bernstein and her colleagues found that PFTs lacked sufficient sensitivity and negative predictive value for the detection of ILD on HRCT in these patients.

An FVC <80% predicted performed at only 63% sensitivity and an false negative rate of 37%. Total lung capacity or DLCO <80% predicted had a sensitivity of 46% and 80%, respectively. The combination of FVC or DLCO <80% predicted raised sensitivity to 85%. However, the addition of total lung capacity to this combination did not improve results.

Overall, PFTs had a positive predictive value of 64%-74% and an negative predictive value of 61%-70%. “This means that PFT alone will not accurately predict the presence of ILD in about 35%, and not be correctly negative in about 35%,” observed Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, and professor of rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

While the combination of FVC <80% predicted or DLCO <80% predicted performed better than the other parameters, the sensitivity “is inadequate for an ILD screening test as it results in an false negative rate of 15%, thereby falsely reassuring 15% of patients that they do not have ILD when in fact they do,” the investigators observed.

“This study reinforces the notion that PFTs alone are ineffective screening tools for ILD in the presence of systemic sclerosis, particularly for patients with early systemic sclerosis,” said Elizabeth Volkmann, MD, MS, assistant professor and codirector of the CTD-ILD program in the division of rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The study’s scope was relatively small, yet the results provide further evidence to show that HRCT should be performed in all SSc patients to screen for the presence of ILD, Dr. Volkmann said in an interview.

Other research has demonstrated the value of baseline HRCT as a prognosticator of ILD outcomes. The method provides useful information about the degree of fibrosis and degree of damage in early-stage disease, said Dr. Furst, also an adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a research professor at the University of Florence (Italy). “If there’s honeycombing, that’s a bad prognosis. If it’s ground glass or reticular changes, the prognosis is better.

“Once there’s a lot of damage, it’s much harder to interpret disease with HRCT,” he added.

HRCT and PFT work well together to assess what’s happening in patients, Dr. Furst explained. HRCT provides an idea of anatomic changes, whereas PFT outlines aspects of functional change to diagnose early ILD in early diffuse SSc. The study results should not apply to patients with later disease who have more developed ILD, he noted.

The investigators acknowledged that they weren’t able to categorize and analyze patients according to disease extent because they didn’t quantify the extent of ILD. Another limitation was that the HRCTs and PFTs were ordered at the discretion of individual physicians, which means that not all participants received the tests.

“Although the tests were done in 90% of the population, there is still a probability of a significant selection bias,” Dr. Furst said.

Dr. Bernstein and several other coauthors in the study received grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases to support their work. Dr. Furst disclosed receiving grant/research support from and/or consulting for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corbus, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche/Genentech. Dr. Volkmann disclosed consulting for and/or receiving grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Corbus, and Forbius.

SOURCE: Bernstein EJ et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Jun 25. doi: 10.1002/art.41415.

Clinicians shouldn’t rely on pulmonary function tests (PFTs) alone to screen for interstitial lung disease (ILD). The tests performed poorly in a retrospective study of 212 patients with systemic sclerosis, reinforcing the findings of previous studies.

Any screening algorithm should include high-resolution CT (HRCT), which is good at prognosticating disease, the investigators wrote in Arthritis & Rheumatology. “I think all newly diagnosed systemic sclerosis patients should have a full set of PFTs (spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusion capacity) and an HRCT at baseline to evaluate for ILD,” the study’s lead author, Elana J. Bernstein, MD, said in an interview.

ILD is a leading cause of death in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients, affecting 40%-60% of those with the disease. HRCT is currently the preferred option for detection of ILD. PFTs are commonly used to screen for ILD but haven’t performed well in previous studies. “Someone can have abnormalities on HRCT that are consistent with ILD but still have PFTs that are in the ‘normal’ range,” explained Dr. Bernstein of Columbia University, New York. One cross-sectional study of 102 SSc patients found that the test’s sensitivity for the detection of ILD on HRCT was just 37.5% when forced vital capacity (FVC) <80% predicted.

Investigators sought to assess performance characteristics of PFTs in patients with early diffuse cutaneous SSc, a cohort at high risk of developing ILD. The study enlisted patients from the Prospective Registry of Early Systemic Sclerosis (PRESS), a multicenter, prospective cohort study of adults with early diffuse cutaneous SSc. Overall, 212 patients at 11 U.S. academic medical centers participated in the study from April 2012 to January 2019.

All patients had spirometry (PFT) and HRCT chest scans. PFTs were conducted per American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines. The investigators calculated test characteristics for single PFT and combinations of PFT parameters for the detection of ILD on HRCT. The HRCTs were ordered at the discretion of treating physicians, and scrutinized for ILD features such as reticular changes, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and ground-glass opacities. The investigators defined the lower limit of normal for FVC, total lung capacity, and diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) as 80% predicted.

Overall, Dr. Bernstein and her colleagues found that PFTs lacked sufficient sensitivity and negative predictive value for the detection of ILD on HRCT in these patients.

An FVC <80% predicted performed at only 63% sensitivity and an false negative rate of 37%. Total lung capacity or DLCO <80% predicted had a sensitivity of 46% and 80%, respectively. The combination of FVC or DLCO <80% predicted raised sensitivity to 85%. However, the addition of total lung capacity to this combination did not improve results.

Overall, PFTs had a positive predictive value of 64%-74% and an negative predictive value of 61%-70%. “This means that PFT alone will not accurately predict the presence of ILD in about 35%, and not be correctly negative in about 35%,” observed Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, and professor of rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

While the combination of FVC <80% predicted or DLCO <80% predicted performed better than the other parameters, the sensitivity “is inadequate for an ILD screening test as it results in an false negative rate of 15%, thereby falsely reassuring 15% of patients that they do not have ILD when in fact they do,” the investigators observed.

“This study reinforces the notion that PFTs alone are ineffective screening tools for ILD in the presence of systemic sclerosis, particularly for patients with early systemic sclerosis,” said Elizabeth Volkmann, MD, MS, assistant professor and codirector of the CTD-ILD program in the division of rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The study’s scope was relatively small, yet the results provide further evidence to show that HRCT should be performed in all SSc patients to screen for the presence of ILD, Dr. Volkmann said in an interview.

Other research has demonstrated the value of baseline HRCT as a prognosticator of ILD outcomes. The method provides useful information about the degree of fibrosis and degree of damage in early-stage disease, said Dr. Furst, also an adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a research professor at the University of Florence (Italy). “If there’s honeycombing, that’s a bad prognosis. If it’s ground glass or reticular changes, the prognosis is better.

“Once there’s a lot of damage, it’s much harder to interpret disease with HRCT,” he added.

HRCT and PFT work well together to assess what’s happening in patients, Dr. Furst explained. HRCT provides an idea of anatomic changes, whereas PFT outlines aspects of functional change to diagnose early ILD in early diffuse SSc. The study results should not apply to patients with later disease who have more developed ILD, he noted.

The investigators acknowledged that they weren’t able to categorize and analyze patients according to disease extent because they didn’t quantify the extent of ILD. Another limitation was that the HRCTs and PFTs were ordered at the discretion of individual physicians, which means that not all participants received the tests.

“Although the tests were done in 90% of the population, there is still a probability of a significant selection bias,” Dr. Furst said.

Dr. Bernstein and several other coauthors in the study received grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases to support their work. Dr. Furst disclosed receiving grant/research support from and/or consulting for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corbus, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche/Genentech. Dr. Volkmann disclosed consulting for and/or receiving grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Corbus, and Forbius.

SOURCE: Bernstein EJ et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Jun 25. doi: 10.1002/art.41415.

Clinicians shouldn’t rely on pulmonary function tests (PFTs) alone to screen for interstitial lung disease (ILD). The tests performed poorly in a retrospective study of 212 patients with systemic sclerosis, reinforcing the findings of previous studies.

Any screening algorithm should include high-resolution CT (HRCT), which is good at prognosticating disease, the investigators wrote in Arthritis & Rheumatology. “I think all newly diagnosed systemic sclerosis patients should have a full set of PFTs (spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusion capacity) and an HRCT at baseline to evaluate for ILD,” the study’s lead author, Elana J. Bernstein, MD, said in an interview.

ILD is a leading cause of death in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients, affecting 40%-60% of those with the disease. HRCT is currently the preferred option for detection of ILD. PFTs are commonly used to screen for ILD but haven’t performed well in previous studies. “Someone can have abnormalities on HRCT that are consistent with ILD but still have PFTs that are in the ‘normal’ range,” explained Dr. Bernstein of Columbia University, New York. One cross-sectional study of 102 SSc patients found that the test’s sensitivity for the detection of ILD on HRCT was just 37.5% when forced vital capacity (FVC) <80% predicted.

Investigators sought to assess performance characteristics of PFTs in patients with early diffuse cutaneous SSc, a cohort at high risk of developing ILD. The study enlisted patients from the Prospective Registry of Early Systemic Sclerosis (PRESS), a multicenter, prospective cohort study of adults with early diffuse cutaneous SSc. Overall, 212 patients at 11 U.S. academic medical centers participated in the study from April 2012 to January 2019.

All patients had spirometry (PFT) and HRCT chest scans. PFTs were conducted per American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines. The investigators calculated test characteristics for single PFT and combinations of PFT parameters for the detection of ILD on HRCT. The HRCTs were ordered at the discretion of treating physicians, and scrutinized for ILD features such as reticular changes, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and ground-glass opacities. The investigators defined the lower limit of normal for FVC, total lung capacity, and diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) as 80% predicted.

Overall, Dr. Bernstein and her colleagues found that PFTs lacked sufficient sensitivity and negative predictive value for the detection of ILD on HRCT in these patients.

An FVC <80% predicted performed at only 63% sensitivity and an false negative rate of 37%. Total lung capacity or DLCO <80% predicted had a sensitivity of 46% and 80%, respectively. The combination of FVC or DLCO <80% predicted raised sensitivity to 85%. However, the addition of total lung capacity to this combination did not improve results.

Overall, PFTs had a positive predictive value of 64%-74% and an negative predictive value of 61%-70%. “This means that PFT alone will not accurately predict the presence of ILD in about 35%, and not be correctly negative in about 35%,” observed Daniel E. Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, and professor of rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

While the combination of FVC <80% predicted or DLCO <80% predicted performed better than the other parameters, the sensitivity “is inadequate for an ILD screening test as it results in an false negative rate of 15%, thereby falsely reassuring 15% of patients that they do not have ILD when in fact they do,” the investigators observed.

“This study reinforces the notion that PFTs alone are ineffective screening tools for ILD in the presence of systemic sclerosis, particularly for patients with early systemic sclerosis,” said Elizabeth Volkmann, MD, MS, assistant professor and codirector of the CTD-ILD program in the division of rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The study’s scope was relatively small, yet the results provide further evidence to show that HRCT should be performed in all SSc patients to screen for the presence of ILD, Dr. Volkmann said in an interview.

Other research has demonstrated the value of baseline HRCT as a prognosticator of ILD outcomes. The method provides useful information about the degree of fibrosis and degree of damage in early-stage disease, said Dr. Furst, also an adjunct professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a research professor at the University of Florence (Italy). “If there’s honeycombing, that’s a bad prognosis. If it’s ground glass or reticular changes, the prognosis is better.

“Once there’s a lot of damage, it’s much harder to interpret disease with HRCT,” he added.

HRCT and PFT work well together to assess what’s happening in patients, Dr. Furst explained. HRCT provides an idea of anatomic changes, whereas PFT outlines aspects of functional change to diagnose early ILD in early diffuse SSc. The study results should not apply to patients with later disease who have more developed ILD, he noted.

The investigators acknowledged that they weren’t able to categorize and analyze patients according to disease extent because they didn’t quantify the extent of ILD. Another limitation was that the HRCTs and PFTs were ordered at the discretion of individual physicians, which means that not all participants received the tests.

“Although the tests were done in 90% of the population, there is still a probability of a significant selection bias,” Dr. Furst said.

Dr. Bernstein and several other coauthors in the study received grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases to support their work. Dr. Furst disclosed receiving grant/research support from and/or consulting for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corbus, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche/Genentech. Dr. Volkmann disclosed consulting for and/or receiving grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Corbus, and Forbius.

SOURCE: Bernstein EJ et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Jun 25. doi: 10.1002/art.41415.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Despite guidelines, children receive opioids and steroids for pneumonia and sinusitis

A significant percentage of children receive opioids and systemic corticosteroids for pneumonia and sinusitis despite guidelines, according to an analysis of 2016 Medicaid data from South Carolina.

Prescriptions for these drugs were more likely after visits to EDs than after ambulatory visits, researchers reported in Pediatrics.

“Each of the 828 opioid and 2,737 systemic steroid prescriptions in the data set represent a potentially inappropriate prescription,” wrote Karina G. Phang, MD, MPH, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., and colleagues. “These rates appear excessive given that the use of these medications is not supported by available research or recommended in national guidelines.”

To compare the frequency of opioid and corticosteroid prescriptions for children with pneumonia or sinusitis in ED and ambulatory care settings, the investigators studied 2016 South Carolina Medicaid claims, examining data for patients aged 5-18 years with pneumonia or sinusitis. They excluded children with chronic conditions and acute secondary diagnoses with potentially appropriate indications for steroids, such as asthma. They also excluded children seen at more than one type of clinical location or hospitalized within a week of the visit. Only the primary diagnosis of pneumonia or sinusitis during the first visit of the year for each patient was included.

The researchers included data from 31,838 children in the study, including 2,140 children with pneumonia and 29,698 with sinusitis.

Pneumonia was linked to an opioid prescription in 6% of ED visits (34 of 542) and 1.5% of ambulatory visits (24 of 1,590) (P ≤ .0001). Pneumonia was linked to a steroid prescription in 20% of ED visits (106 of 542) and 12% of ambulatory visits (196 of 1,590) (P ≤ .0001).

Sinusitis was linked to an opioid prescription in 7.5% of ED visits (202 of 2,705) and 2% of ambulatory visits (568 of 26,866) (P ≤ .0001). Sinusitis was linked to a steroid prescription in 19% of ED visits (510 of 2,705) and 7% of ambulatory visits (1,922 of 26,866) (P ≤ .0001).

In logistic regression analyses, ED visits for pneumonia or sinusitis were more than four times more likely to result in children receiving opioids, relative to ambulatory visits (adjusted odds ratio, 4.69 and 4.02, respectively). ED visits also were more likely to result in steroid prescriptions, with aORs of 1.67 for pneumonia and 3.05 for sinusitis.

“I was disappointed to read of these results, although not necessarily surprised,” Michael E. Pichichero, MD, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital, said in an interview.

The data suggest that improved prescribing practices may be needed, “especially in the ED,” wrote Dr. Phang and colleagues. “Although more children who are acutely ill may be seen in the ED, national practice guidelines and research remain relevant for these patients.”

Repeated or prolonged courses of systemic corticosteroids put children at risk for adrenal suppression and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction. “Providers for children must also be aware of the trends in opioid abuse and diversion and must mitigate those risks while still providing adequate analgesia and symptom control,” they wrote.

The use of Medicaid data from 1 year in one state limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the visits occurred “well after publication of relevant guidelines and after concerns of opioid prescribing had become widespread,” according to Dr. Phang and colleagues.

A post hoc evaluation identified one patient with a secondary diagnosis of fracture and 24 patients with a secondary diagnosis of pain, but none of these patients had received an opioid. “Thus, the small subset of patients who may have had secondary diagnoses that would warrant an opioid prescription would not have changed the overall results,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Phang KG et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3690.

A significant percentage of children receive opioids and systemic corticosteroids for pneumonia and sinusitis despite guidelines, according to an analysis of 2016 Medicaid data from South Carolina.

Prescriptions for these drugs were more likely after visits to EDs than after ambulatory visits, researchers reported in Pediatrics.

“Each of the 828 opioid and 2,737 systemic steroid prescriptions in the data set represent a potentially inappropriate prescription,” wrote Karina G. Phang, MD, MPH, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., and colleagues. “These rates appear excessive given that the use of these medications is not supported by available research or recommended in national guidelines.”

To compare the frequency of opioid and corticosteroid prescriptions for children with pneumonia or sinusitis in ED and ambulatory care settings, the investigators studied 2016 South Carolina Medicaid claims, examining data for patients aged 5-18 years with pneumonia or sinusitis. They excluded children with chronic conditions and acute secondary diagnoses with potentially appropriate indications for steroids, such as asthma. They also excluded children seen at more than one type of clinical location or hospitalized within a week of the visit. Only the primary diagnosis of pneumonia or sinusitis during the first visit of the year for each patient was included.

The researchers included data from 31,838 children in the study, including 2,140 children with pneumonia and 29,698 with sinusitis.

Pneumonia was linked to an opioid prescription in 6% of ED visits (34 of 542) and 1.5% of ambulatory visits (24 of 1,590) (P ≤ .0001). Pneumonia was linked to a steroid prescription in 20% of ED visits (106 of 542) and 12% of ambulatory visits (196 of 1,590) (P ≤ .0001).

Sinusitis was linked to an opioid prescription in 7.5% of ED visits (202 of 2,705) and 2% of ambulatory visits (568 of 26,866) (P ≤ .0001). Sinusitis was linked to a steroid prescription in 19% of ED visits (510 of 2,705) and 7% of ambulatory visits (1,922 of 26,866) (P ≤ .0001).

In logistic regression analyses, ED visits for pneumonia or sinusitis were more than four times more likely to result in children receiving opioids, relative to ambulatory visits (adjusted odds ratio, 4.69 and 4.02, respectively). ED visits also were more likely to result in steroid prescriptions, with aORs of 1.67 for pneumonia and 3.05 for sinusitis.

“I was disappointed to read of these results, although not necessarily surprised,” Michael E. Pichichero, MD, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital, said in an interview.

The data suggest that improved prescribing practices may be needed, “especially in the ED,” wrote Dr. Phang and colleagues. “Although more children who are acutely ill may be seen in the ED, national practice guidelines and research remain relevant for these patients.”

Repeated or prolonged courses of systemic corticosteroids put children at risk for adrenal suppression and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction. “Providers for children must also be aware of the trends in opioid abuse and diversion and must mitigate those risks while still providing adequate analgesia and symptom control,” they wrote.

The use of Medicaid data from 1 year in one state limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the visits occurred “well after publication of relevant guidelines and after concerns of opioid prescribing had become widespread,” according to Dr. Phang and colleagues.

A post hoc evaluation identified one patient with a secondary diagnosis of fracture and 24 patients with a secondary diagnosis of pain, but none of these patients had received an opioid. “Thus, the small subset of patients who may have had secondary diagnoses that would warrant an opioid prescription would not have changed the overall results,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Phang KG et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3690.

A significant percentage of children receive opioids and systemic corticosteroids for pneumonia and sinusitis despite guidelines, according to an analysis of 2016 Medicaid data from South Carolina.

Prescriptions for these drugs were more likely after visits to EDs than after ambulatory visits, researchers reported in Pediatrics.

“Each of the 828 opioid and 2,737 systemic steroid prescriptions in the data set represent a potentially inappropriate prescription,” wrote Karina G. Phang, MD, MPH, of Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pa., and colleagues. “These rates appear excessive given that the use of these medications is not supported by available research or recommended in national guidelines.”

To compare the frequency of opioid and corticosteroid prescriptions for children with pneumonia or sinusitis in ED and ambulatory care settings, the investigators studied 2016 South Carolina Medicaid claims, examining data for patients aged 5-18 years with pneumonia or sinusitis. They excluded children with chronic conditions and acute secondary diagnoses with potentially appropriate indications for steroids, such as asthma. They also excluded children seen at more than one type of clinical location or hospitalized within a week of the visit. Only the primary diagnosis of pneumonia or sinusitis during the first visit of the year for each patient was included.

The researchers included data from 31,838 children in the study, including 2,140 children with pneumonia and 29,698 with sinusitis.

Pneumonia was linked to an opioid prescription in 6% of ED visits (34 of 542) and 1.5% of ambulatory visits (24 of 1,590) (P ≤ .0001). Pneumonia was linked to a steroid prescription in 20% of ED visits (106 of 542) and 12% of ambulatory visits (196 of 1,590) (P ≤ .0001).

Sinusitis was linked to an opioid prescription in 7.5% of ED visits (202 of 2,705) and 2% of ambulatory visits (568 of 26,866) (P ≤ .0001). Sinusitis was linked to a steroid prescription in 19% of ED visits (510 of 2,705) and 7% of ambulatory visits (1,922 of 26,866) (P ≤ .0001).

In logistic regression analyses, ED visits for pneumonia or sinusitis were more than four times more likely to result in children receiving opioids, relative to ambulatory visits (adjusted odds ratio, 4.69 and 4.02, respectively). ED visits also were more likely to result in steroid prescriptions, with aORs of 1.67 for pneumonia and 3.05 for sinusitis.

“I was disappointed to read of these results, although not necessarily surprised,” Michael E. Pichichero, MD, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital, said in an interview.

The data suggest that improved prescribing practices may be needed, “especially in the ED,” wrote Dr. Phang and colleagues. “Although more children who are acutely ill may be seen in the ED, national practice guidelines and research remain relevant for these patients.”

Repeated or prolonged courses of systemic corticosteroids put children at risk for adrenal suppression and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction. “Providers for children must also be aware of the trends in opioid abuse and diversion and must mitigate those risks while still providing adequate analgesia and symptom control,” they wrote.

The use of Medicaid data from 1 year in one state limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the visits occurred “well after publication of relevant guidelines and after concerns of opioid prescribing had become widespread,” according to Dr. Phang and colleagues.

A post hoc evaluation identified one patient with a secondary diagnosis of fracture and 24 patients with a secondary diagnosis of pain, but none of these patients had received an opioid. “Thus, the small subset of patients who may have had secondary diagnoses that would warrant an opioid prescription would not have changed the overall results,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Phang KG et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3690.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Primary care practices may lose about $68k per physician this year

Primary care practices stand to lose almost $68,000 per full-time physician this year as COVID-19 causes care delays and cancellations, researchers estimate. And while some outpatient care has started to rebound to near baseline appointment levels, other ambulatory specialties remain dramatically down from prepandemic rates.

For primary care practices, Sanjay Basu, MD, and colleagues calculated the losses at $67,774 in gross revenue per physician (interquartile range, $80,577-$54,990), with a national toll of $15.1 billion this year.

That’s without a potential second wave of COVID-19, noted Dr. Basu, director of research and population health at Collective Health in San Francisco, and colleagues.

When they added a theoretical stay-at-home order for November and December, the estimated loss climbed to $85,666 in gross revenue per full-time physician, with a loss of $19.1 billion nationally. The findings were published online in Health Affairs.

Meanwhile, clinical losses from canceled outpatient care are piling up as well, according to a study by Ateev Mehrotra, MD, associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues, which calculated the clinical losses in outpatient care.

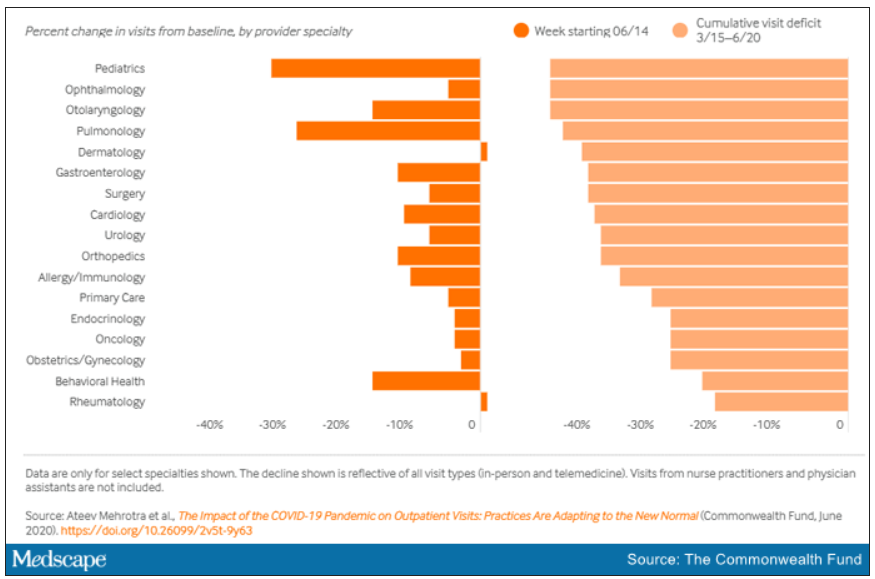

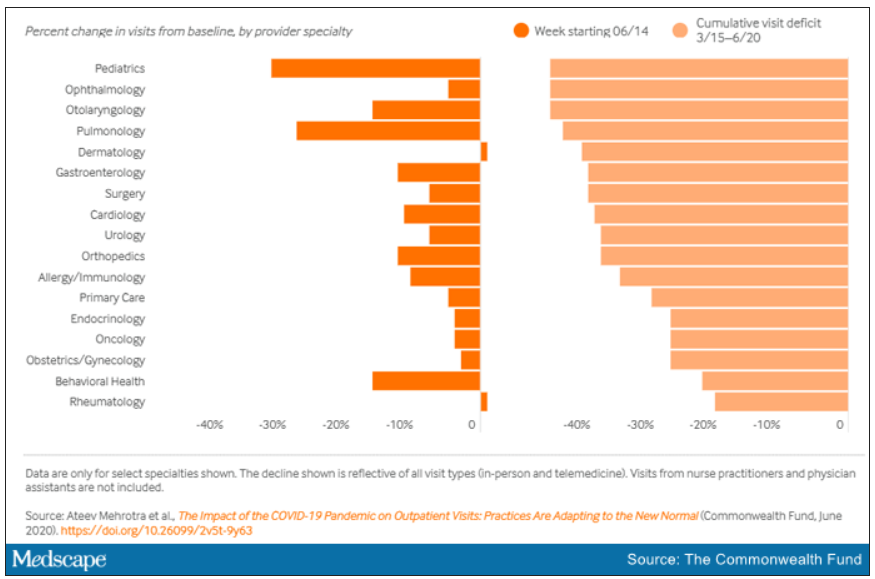

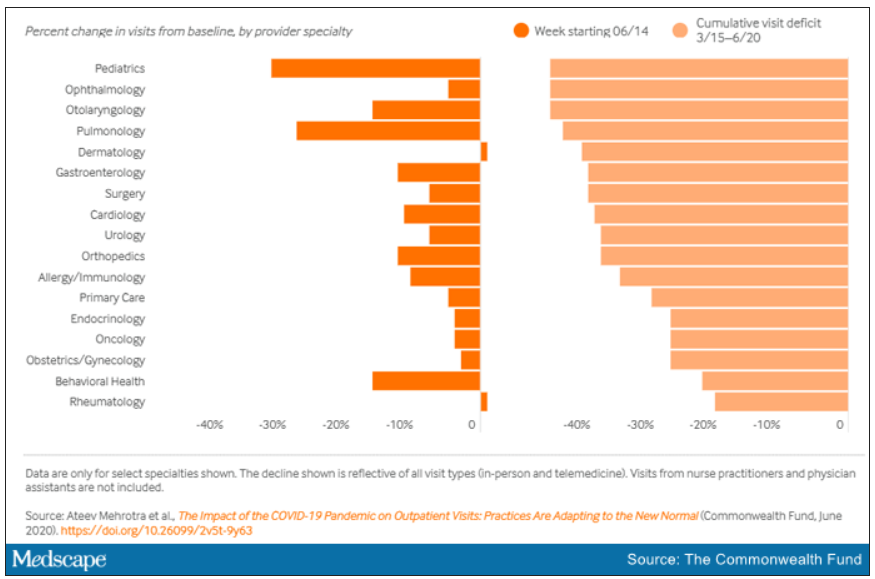

“The ‘cumulative deficit’ in visits over the last 3 months (March 15 to June 20) is nearly 40%,” the authors wrote. They reported their findings in an article published online June 25 by the Commonwealth Fund.

When examined by specialty, Dr. Mehrotra and colleagues found that appointment rebound rates have been uneven. Whereas dermatology and rheumatology visits have already recovered, a couple of specialties have cumulative deficits that are particularly concerning. For example, pediatric visits were down by 47% in the 3 months since March 15 and pulmonology visits were down 45% in that time.

Much depends on the future of telehealth

Closing the financial and care gaps will depend largely on changing payment models for outpatient care and assuring adequate and enduring reimbursement for telehealth, according to experts.

COVID-19 has put a spotlight on the fragility of a fee-for-service system that depends on in-person visits for stability, Daniel Horn, MD, director of population health and quality at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview.

Several things need to happen to change the outlook for outpatient care, he said.

A need mentioned in both studies is that the COVID-19 waivers that make it possible for telehealth visits to be reimbursed like other visits must continue after the pandemic. Those assurances are critical as practices decide whether to invest in telemedicine.

If U.S. practices revert as of Oct. 1, 2020, to the pre–COVID-19 payment system for telehealth, national losses for the year would be more than double the current estimates.

“Given the number of active primary care physicians (n = 223,125), we estimated that the cost would be $38.7 billion (IQR, $31.1 billion-$48.3 billion) at a national level to neutralize the gross revenue losses caused by COVID-19 among primary care practices, without subjecting staff to furloughs,” Dr. Basu and colleagues wrote.

In addition to stabilizing telehealth payment models, another need to improve the outlook for outpatient care is more effective communication that in-person care is safe again in regions with protocols in place, Dr. Horn said.

However, the most important change, Dr. Horn said, is a switch to prospective lump-sum payments – payments made in advance to physicians to treat each patient in the way they and the patient deem best with the most appropriate appointment type – whether by in-person visit, phone call, text reminders, or video session.

Prospective payments would take multipayer coalitions working in conjunction with leadership on the federal level from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Dr. Horn said. Commercial payers and states (through Medicaid funds) should already have that money available with the cancellations of nonessential procedures, he said.

“We expect ongoing turbulent times, so having a prospective payment could unleash the capacity for primary care practices to be creative in the way they care for their patients,” Dr. Horn said.

Visit trends still down

Calculations by Dr. Basu, who is also on the faculty at Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care, and colleagues were partially informed by Dr. Mehrotra’s data on how many visits have been lost because of COVID-19.