User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

An update on the pharmacologic treatment of hypersomnia

The hypersomnias are an etiologically diverse group of disorders of wakefulness and sleep, characterized principally by excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), often despite sufficient or even long total sleep durations. Hypersomnolence may be severely disabling and isolating for patients, is associated with decreased quality of life and economic disadvantage, and, in some cases, may pose a personal and public health danger through drowsy driving. Though historically, management of these patients has been principally supportive and aimed at reducing daytime functional impairment, new and evolving treatments are quickly changing management paradigms in this population. This brief review highlights some of the newest pharmacotherapeutic advances in this dynamic field.

Hypersomnolence is a common presenting concern primary care and sleep clinics, with an estimated prevalence of EDS in the general adult population of as high as 6%.1 The initial diagnosis of hypersomnia is, broadly, a clinical one, with careful consideration to the patient’s report of daytime sleepiness and functional impairment, sleep/wake cycle, and any medical comorbidities. The primary hypersomnias include narcolepsy type 1 (narcolepsy with cataplexy, NT1) and narcolepsy type 2 (without cataplexy, NT2), Kleine-Levin Syndrome (KLS), and idiopathic hypersomnia. Secondary hypersomnia disorders are more commonly encountered in clinical practice and include hypersomnia attributable to another medical condition (including psychiatric and neurologic disorders), hypersomnia related to medication effects, and EDS related to behaviorally insufficient sleep. Distinguishing primary and secondary etiologies, when possible, is important as treatment pathways may vary considerably between hypersomnias.

Generally, overnight in-lab polysomnography is warranted to exclude untreated or sub-optimally treated sleep-disordered breathing or movement disorders which may undermine sleep quality. In the absence of any such findings, this is usually followed by daytime multiple sleep latency testing (MSLT). The MSLT is comprised of four to five scheduled daytime naps in the sleep lab and is designed to quantify a patient’s propensity to sleep during the day and to identify architectural sleep abnormalities which indicate narcolepsy. Specifically, narcolepsy is identified by MSLT when a patient exhibits a sleep onset latency of ≤ 8 minutes and at least two sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs), or, one SOREMP on MSLT with a second noted on the preceding night’s PSG. Actigraphy or sleep logs may be helpful in quantifying a patient’s total sleep time in their home environment. Adjunctive laboratory tests for narcolepsy including HLA typing and CSF hypocretin testing may sometimes be indicated.

General hypersomnia management usually consists of the use of wakefulness promoting agents, such as stimulants (eg, dexmethylphenidate) and dopamine-modulating agents (eg, modafinil, armodafinil), and adjunctive supportive strategies, including planned daytime naps and elimination of modifiable secondary causes. In those patients with hypersomnolence associated with depression or anxiety, the use of antidepressants, including SSRI, SNRI, and DNRIs, is often effective, and these medications can also improve cataplexy symptoms in narcoleptics. KLS may respond to treatment with lithium, shortening the duration of the striking hypersomnolent episodes characteristic of this rare syndrome, and there is some indication that ketamine may also be a helpful adjunctive in some cases. In treatment-refractory cases of hypersomnolence associated with GABA-A receptor potentiation, drugs such as flumazenil and clarithromycin appear to improve subjective measures of hypersomnolence.2,3 In patients with narcolepsy, sodium oxybate (available as Xyrem and, more recently, as a generic medication) has proven to be clinically very useful, reducing EDS and the frequency and severity of cataplexy and sleep disturbance associated with this condition. In July 2020, the FDA approved a new, low-sodium formulation of sodium oxybate (Xywav) for patients 7 years of age and older with a diagnosis of narcolepsy, a helpful option in those patients with cardiovascular and renal disease.

Despite this broadening armamentarium, in many cases daytime sleepiness and functional impairment is refractory to typical pharmacotherapy. In this context, we would like to highlight two newer pharmacotherapeutic options, solriamfetol and pitolisant.

Solriamfetol

Solriamfetol (Sunosi) is a Schedule IV FDA-approved medication indicated for treatment of EDS in adults with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. The precise mechanism of action is unknown, but this medication is believed to inhibit both dopamine and norepinerphrine reuptake in the brain, similar to the widely-prescribed NDRI buproprion. In a 12-week RCT study on its effects on narcolepsy in adults, solriamfetol improved important measures of wakefulness and sleepiness, without associated polysomnographic evidence of significant sleep disruption.4 In another 12-week RCT study of solriamfetol in adult patients with EDS related to OSA, there was a dose-dependent improvement in measures of wakefulness.5 Some notable side-effects seen with this medication include anxiety and elevated mood, as well as increases in blood pressure. A subsequent study of this medication found that it was efficacious at maintenance of improvements at 6 months.6 Given the theorized mechanism of action as an NDRI, future observation and studies could provide insights on its effect on depression, as well.

Pitolisant

Histaminergic neurons within the CNS play an important role in the promotion of wakefulness. Pitolisant (Wakix) is an interesting wakefulness-promoting agent for adult patients with narcolepsy. It acts as an inverse agonist and antagonist of histamine H3 receptors, resulting in a reduction of the usual feedback inhibition effected through the H3 receptor, thereby enhancing CNS release of histamine and other neurotransmitters. This medication was approved by the FDA in August 2019 and is currently indicated for adult patients with narcolepsy. The HARMONY I trial comparing pitolisant with both placebo and modafinil in adults with narcolepsy and EDS demonstrated improvement in measures of sleepiness and maintenance of wakefulness over placebo, and noninferiority to modafinil.7 In addition, pitolisant had a favorable side-effect profile compared with modafinil. Subsequent studies have reaffirmed the safety profile of pitolisant, including its minimal abuse potential. In one recent placebo-controlled trial of the use of pitolisant in a population of 268 adults with positive airway pressure (PAP) non-adherence, pitolisant was found to improve measures of EDS and related patient-reported measurements in patients with OSA who were CPAP nonadherent.8 Though generally well-tolerated by patients, in initial clinical trials pitolisant was associated with increased headache, insomnia, and nausea relative to placebo, among other less commonly reported adverse effects. Pitolisant is QT interval-prolonging, so caution must be taken when using this medication in combination other medications which may induce QT interval prolongation, including SSRIs.

Future directions

Greater awareness of the hypersomnias and their management has led to improved outcomes and access to care for these patients, yet these disorders remain burdensome and the treatments imperfect. Looking forward, novel pharmacotherapies that target underlying mechanisms rather than symptom palliation will allow for more precise treatments. Ongoing investigations of hypocretin receptor agonists seek to target one critical central mediator of wakefulness. Recent studies have highlighted the association of dysautonomia with hypersomnia, offering interesting insight into possible future targets to improve the function and quality of life of these patients.9 Similarly, understanding of the interplay between psychiatric disorders and primary and secondary hypersomnias may offer new therapeutic pathways.

As treatment plans targeting hypersomnia become more comprehensive and holistic, with an increased emphasis on self-care, sleep hygiene, and mental health awareness, in addition to mechanism-specific treatments, we hope they will ultimately provide improved symptom and burden relief for our patients.

Dr. Shih Yee-Marie Tan Gipson is a psychiatrist and Dr. Kevin Gipson is a sleep medicine specialist, both with Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1 Dauvilliers, et al. Hypersomnia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7(4):347-356.

2 Trotti, et al. Clarithromycin in gamma-aminobutyric acid-related hypersomnolence: A randomized, crossover trial. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(3):454-465. doi: 10.1002/ana.24459.

3 Trotti, et al. Flumazenil for the treatment of refractory hypersomnolence: Clinical experience with 153 patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(10):1389-1394. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6196.

4 Thorpy, et al. A randomized study of solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in narcolepsy. Ann Neurol. 2019; 85(3):359-370. doi: 10.1002/ana.25423.

5 Schweitzer, et al. Solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea (TONES 3): A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(11):1421-1431. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1100OC.

6 Malhotra, et al. Long-term study of the safety and maintenance of efficacy of solriamfetol (JZP-110) in the treatment of excessive sleepiness in participants with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2020; 43(2): doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz220.

7 Dauvilliers, et al. Pitolisant versus placebo or modafinil in patients with narcolepsy: a double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(11):1068-1075. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70225-4.

8 Dauvilliers, et al. Pitolisant for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea patients refusing CPAP: A randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201907-1284OC.

9 Miglis, et al. Frequency and severity of autonomic symptoms in idiopathic hypersomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020; 16(5):749-756. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8344.

The hypersomnias are an etiologically diverse group of disorders of wakefulness and sleep, characterized principally by excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), often despite sufficient or even long total sleep durations. Hypersomnolence may be severely disabling and isolating for patients, is associated with decreased quality of life and economic disadvantage, and, in some cases, may pose a personal and public health danger through drowsy driving. Though historically, management of these patients has been principally supportive and aimed at reducing daytime functional impairment, new and evolving treatments are quickly changing management paradigms in this population. This brief review highlights some of the newest pharmacotherapeutic advances in this dynamic field.

Hypersomnolence is a common presenting concern primary care and sleep clinics, with an estimated prevalence of EDS in the general adult population of as high as 6%.1 The initial diagnosis of hypersomnia is, broadly, a clinical one, with careful consideration to the patient’s report of daytime sleepiness and functional impairment, sleep/wake cycle, and any medical comorbidities. The primary hypersomnias include narcolepsy type 1 (narcolepsy with cataplexy, NT1) and narcolepsy type 2 (without cataplexy, NT2), Kleine-Levin Syndrome (KLS), and idiopathic hypersomnia. Secondary hypersomnia disorders are more commonly encountered in clinical practice and include hypersomnia attributable to another medical condition (including psychiatric and neurologic disorders), hypersomnia related to medication effects, and EDS related to behaviorally insufficient sleep. Distinguishing primary and secondary etiologies, when possible, is important as treatment pathways may vary considerably between hypersomnias.

Generally, overnight in-lab polysomnography is warranted to exclude untreated or sub-optimally treated sleep-disordered breathing or movement disorders which may undermine sleep quality. In the absence of any such findings, this is usually followed by daytime multiple sleep latency testing (MSLT). The MSLT is comprised of four to five scheduled daytime naps in the sleep lab and is designed to quantify a patient’s propensity to sleep during the day and to identify architectural sleep abnormalities which indicate narcolepsy. Specifically, narcolepsy is identified by MSLT when a patient exhibits a sleep onset latency of ≤ 8 minutes and at least two sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs), or, one SOREMP on MSLT with a second noted on the preceding night’s PSG. Actigraphy or sleep logs may be helpful in quantifying a patient’s total sleep time in their home environment. Adjunctive laboratory tests for narcolepsy including HLA typing and CSF hypocretin testing may sometimes be indicated.

General hypersomnia management usually consists of the use of wakefulness promoting agents, such as stimulants (eg, dexmethylphenidate) and dopamine-modulating agents (eg, modafinil, armodafinil), and adjunctive supportive strategies, including planned daytime naps and elimination of modifiable secondary causes. In those patients with hypersomnolence associated with depression or anxiety, the use of antidepressants, including SSRI, SNRI, and DNRIs, is often effective, and these medications can also improve cataplexy symptoms in narcoleptics. KLS may respond to treatment with lithium, shortening the duration of the striking hypersomnolent episodes characteristic of this rare syndrome, and there is some indication that ketamine may also be a helpful adjunctive in some cases. In treatment-refractory cases of hypersomnolence associated with GABA-A receptor potentiation, drugs such as flumazenil and clarithromycin appear to improve subjective measures of hypersomnolence.2,3 In patients with narcolepsy, sodium oxybate (available as Xyrem and, more recently, as a generic medication) has proven to be clinically very useful, reducing EDS and the frequency and severity of cataplexy and sleep disturbance associated with this condition. In July 2020, the FDA approved a new, low-sodium formulation of sodium oxybate (Xywav) for patients 7 years of age and older with a diagnosis of narcolepsy, a helpful option in those patients with cardiovascular and renal disease.

Despite this broadening armamentarium, in many cases daytime sleepiness and functional impairment is refractory to typical pharmacotherapy. In this context, we would like to highlight two newer pharmacotherapeutic options, solriamfetol and pitolisant.

Solriamfetol

Solriamfetol (Sunosi) is a Schedule IV FDA-approved medication indicated for treatment of EDS in adults with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. The precise mechanism of action is unknown, but this medication is believed to inhibit both dopamine and norepinerphrine reuptake in the brain, similar to the widely-prescribed NDRI buproprion. In a 12-week RCT study on its effects on narcolepsy in adults, solriamfetol improved important measures of wakefulness and sleepiness, without associated polysomnographic evidence of significant sleep disruption.4 In another 12-week RCT study of solriamfetol in adult patients with EDS related to OSA, there was a dose-dependent improvement in measures of wakefulness.5 Some notable side-effects seen with this medication include anxiety and elevated mood, as well as increases in blood pressure. A subsequent study of this medication found that it was efficacious at maintenance of improvements at 6 months.6 Given the theorized mechanism of action as an NDRI, future observation and studies could provide insights on its effect on depression, as well.

Pitolisant

Histaminergic neurons within the CNS play an important role in the promotion of wakefulness. Pitolisant (Wakix) is an interesting wakefulness-promoting agent for adult patients with narcolepsy. It acts as an inverse agonist and antagonist of histamine H3 receptors, resulting in a reduction of the usual feedback inhibition effected through the H3 receptor, thereby enhancing CNS release of histamine and other neurotransmitters. This medication was approved by the FDA in August 2019 and is currently indicated for adult patients with narcolepsy. The HARMONY I trial comparing pitolisant with both placebo and modafinil in adults with narcolepsy and EDS demonstrated improvement in measures of sleepiness and maintenance of wakefulness over placebo, and noninferiority to modafinil.7 In addition, pitolisant had a favorable side-effect profile compared with modafinil. Subsequent studies have reaffirmed the safety profile of pitolisant, including its minimal abuse potential. In one recent placebo-controlled trial of the use of pitolisant in a population of 268 adults with positive airway pressure (PAP) non-adherence, pitolisant was found to improve measures of EDS and related patient-reported measurements in patients with OSA who were CPAP nonadherent.8 Though generally well-tolerated by patients, in initial clinical trials pitolisant was associated with increased headache, insomnia, and nausea relative to placebo, among other less commonly reported adverse effects. Pitolisant is QT interval-prolonging, so caution must be taken when using this medication in combination other medications which may induce QT interval prolongation, including SSRIs.

Future directions

Greater awareness of the hypersomnias and their management has led to improved outcomes and access to care for these patients, yet these disorders remain burdensome and the treatments imperfect. Looking forward, novel pharmacotherapies that target underlying mechanisms rather than symptom palliation will allow for more precise treatments. Ongoing investigations of hypocretin receptor agonists seek to target one critical central mediator of wakefulness. Recent studies have highlighted the association of dysautonomia with hypersomnia, offering interesting insight into possible future targets to improve the function and quality of life of these patients.9 Similarly, understanding of the interplay between psychiatric disorders and primary and secondary hypersomnias may offer new therapeutic pathways.

As treatment plans targeting hypersomnia become more comprehensive and holistic, with an increased emphasis on self-care, sleep hygiene, and mental health awareness, in addition to mechanism-specific treatments, we hope they will ultimately provide improved symptom and burden relief for our patients.

Dr. Shih Yee-Marie Tan Gipson is a psychiatrist and Dr. Kevin Gipson is a sleep medicine specialist, both with Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1 Dauvilliers, et al. Hypersomnia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7(4):347-356.

2 Trotti, et al. Clarithromycin in gamma-aminobutyric acid-related hypersomnolence: A randomized, crossover trial. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(3):454-465. doi: 10.1002/ana.24459.

3 Trotti, et al. Flumazenil for the treatment of refractory hypersomnolence: Clinical experience with 153 patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(10):1389-1394. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6196.

4 Thorpy, et al. A randomized study of solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in narcolepsy. Ann Neurol. 2019; 85(3):359-370. doi: 10.1002/ana.25423.

5 Schweitzer, et al. Solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea (TONES 3): A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(11):1421-1431. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1100OC.

6 Malhotra, et al. Long-term study of the safety and maintenance of efficacy of solriamfetol (JZP-110) in the treatment of excessive sleepiness in participants with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2020; 43(2): doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz220.

7 Dauvilliers, et al. Pitolisant versus placebo or modafinil in patients with narcolepsy: a double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(11):1068-1075. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70225-4.

8 Dauvilliers, et al. Pitolisant for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea patients refusing CPAP: A randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201907-1284OC.

9 Miglis, et al. Frequency and severity of autonomic symptoms in idiopathic hypersomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020; 16(5):749-756. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8344.

The hypersomnias are an etiologically diverse group of disorders of wakefulness and sleep, characterized principally by excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), often despite sufficient or even long total sleep durations. Hypersomnolence may be severely disabling and isolating for patients, is associated with decreased quality of life and economic disadvantage, and, in some cases, may pose a personal and public health danger through drowsy driving. Though historically, management of these patients has been principally supportive and aimed at reducing daytime functional impairment, new and evolving treatments are quickly changing management paradigms in this population. This brief review highlights some of the newest pharmacotherapeutic advances in this dynamic field.

Hypersomnolence is a common presenting concern primary care and sleep clinics, with an estimated prevalence of EDS in the general adult population of as high as 6%.1 The initial diagnosis of hypersomnia is, broadly, a clinical one, with careful consideration to the patient’s report of daytime sleepiness and functional impairment, sleep/wake cycle, and any medical comorbidities. The primary hypersomnias include narcolepsy type 1 (narcolepsy with cataplexy, NT1) and narcolepsy type 2 (without cataplexy, NT2), Kleine-Levin Syndrome (KLS), and idiopathic hypersomnia. Secondary hypersomnia disorders are more commonly encountered in clinical practice and include hypersomnia attributable to another medical condition (including psychiatric and neurologic disorders), hypersomnia related to medication effects, and EDS related to behaviorally insufficient sleep. Distinguishing primary and secondary etiologies, when possible, is important as treatment pathways may vary considerably between hypersomnias.

Generally, overnight in-lab polysomnography is warranted to exclude untreated or sub-optimally treated sleep-disordered breathing or movement disorders which may undermine sleep quality. In the absence of any such findings, this is usually followed by daytime multiple sleep latency testing (MSLT). The MSLT is comprised of four to five scheduled daytime naps in the sleep lab and is designed to quantify a patient’s propensity to sleep during the day and to identify architectural sleep abnormalities which indicate narcolepsy. Specifically, narcolepsy is identified by MSLT when a patient exhibits a sleep onset latency of ≤ 8 minutes and at least two sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs), or, one SOREMP on MSLT with a second noted on the preceding night’s PSG. Actigraphy or sleep logs may be helpful in quantifying a patient’s total sleep time in their home environment. Adjunctive laboratory tests for narcolepsy including HLA typing and CSF hypocretin testing may sometimes be indicated.

General hypersomnia management usually consists of the use of wakefulness promoting agents, such as stimulants (eg, dexmethylphenidate) and dopamine-modulating agents (eg, modafinil, armodafinil), and adjunctive supportive strategies, including planned daytime naps and elimination of modifiable secondary causes. In those patients with hypersomnolence associated with depression or anxiety, the use of antidepressants, including SSRI, SNRI, and DNRIs, is often effective, and these medications can also improve cataplexy symptoms in narcoleptics. KLS may respond to treatment with lithium, shortening the duration of the striking hypersomnolent episodes characteristic of this rare syndrome, and there is some indication that ketamine may also be a helpful adjunctive in some cases. In treatment-refractory cases of hypersomnolence associated with GABA-A receptor potentiation, drugs such as flumazenil and clarithromycin appear to improve subjective measures of hypersomnolence.2,3 In patients with narcolepsy, sodium oxybate (available as Xyrem and, more recently, as a generic medication) has proven to be clinically very useful, reducing EDS and the frequency and severity of cataplexy and sleep disturbance associated with this condition. In July 2020, the FDA approved a new, low-sodium formulation of sodium oxybate (Xywav) for patients 7 years of age and older with a diagnosis of narcolepsy, a helpful option in those patients with cardiovascular and renal disease.

Despite this broadening armamentarium, in many cases daytime sleepiness and functional impairment is refractory to typical pharmacotherapy. In this context, we would like to highlight two newer pharmacotherapeutic options, solriamfetol and pitolisant.

Solriamfetol

Solriamfetol (Sunosi) is a Schedule IV FDA-approved medication indicated for treatment of EDS in adults with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. The precise mechanism of action is unknown, but this medication is believed to inhibit both dopamine and norepinerphrine reuptake in the brain, similar to the widely-prescribed NDRI buproprion. In a 12-week RCT study on its effects on narcolepsy in adults, solriamfetol improved important measures of wakefulness and sleepiness, without associated polysomnographic evidence of significant sleep disruption.4 In another 12-week RCT study of solriamfetol in adult patients with EDS related to OSA, there was a dose-dependent improvement in measures of wakefulness.5 Some notable side-effects seen with this medication include anxiety and elevated mood, as well as increases in blood pressure. A subsequent study of this medication found that it was efficacious at maintenance of improvements at 6 months.6 Given the theorized mechanism of action as an NDRI, future observation and studies could provide insights on its effect on depression, as well.

Pitolisant

Histaminergic neurons within the CNS play an important role in the promotion of wakefulness. Pitolisant (Wakix) is an interesting wakefulness-promoting agent for adult patients with narcolepsy. It acts as an inverse agonist and antagonist of histamine H3 receptors, resulting in a reduction of the usual feedback inhibition effected through the H3 receptor, thereby enhancing CNS release of histamine and other neurotransmitters. This medication was approved by the FDA in August 2019 and is currently indicated for adult patients with narcolepsy. The HARMONY I trial comparing pitolisant with both placebo and modafinil in adults with narcolepsy and EDS demonstrated improvement in measures of sleepiness and maintenance of wakefulness over placebo, and noninferiority to modafinil.7 In addition, pitolisant had a favorable side-effect profile compared with modafinil. Subsequent studies have reaffirmed the safety profile of pitolisant, including its minimal abuse potential. In one recent placebo-controlled trial of the use of pitolisant in a population of 268 adults with positive airway pressure (PAP) non-adherence, pitolisant was found to improve measures of EDS and related patient-reported measurements in patients with OSA who were CPAP nonadherent.8 Though generally well-tolerated by patients, in initial clinical trials pitolisant was associated with increased headache, insomnia, and nausea relative to placebo, among other less commonly reported adverse effects. Pitolisant is QT interval-prolonging, so caution must be taken when using this medication in combination other medications which may induce QT interval prolongation, including SSRIs.

Future directions

Greater awareness of the hypersomnias and their management has led to improved outcomes and access to care for these patients, yet these disorders remain burdensome and the treatments imperfect. Looking forward, novel pharmacotherapies that target underlying mechanisms rather than symptom palliation will allow for more precise treatments. Ongoing investigations of hypocretin receptor agonists seek to target one critical central mediator of wakefulness. Recent studies have highlighted the association of dysautonomia with hypersomnia, offering interesting insight into possible future targets to improve the function and quality of life of these patients.9 Similarly, understanding of the interplay between psychiatric disorders and primary and secondary hypersomnias may offer new therapeutic pathways.

As treatment plans targeting hypersomnia become more comprehensive and holistic, with an increased emphasis on self-care, sleep hygiene, and mental health awareness, in addition to mechanism-specific treatments, we hope they will ultimately provide improved symptom and burden relief for our patients.

Dr. Shih Yee-Marie Tan Gipson is a psychiatrist and Dr. Kevin Gipson is a sleep medicine specialist, both with Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1 Dauvilliers, et al. Hypersomnia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7(4):347-356.

2 Trotti, et al. Clarithromycin in gamma-aminobutyric acid-related hypersomnolence: A randomized, crossover trial. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(3):454-465. doi: 10.1002/ana.24459.

3 Trotti, et al. Flumazenil for the treatment of refractory hypersomnolence: Clinical experience with 153 patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(10):1389-1394. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6196.

4 Thorpy, et al. A randomized study of solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in narcolepsy. Ann Neurol. 2019; 85(3):359-370. doi: 10.1002/ana.25423.

5 Schweitzer, et al. Solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea (TONES 3): A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(11):1421-1431. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1100OC.

6 Malhotra, et al. Long-term study of the safety and maintenance of efficacy of solriamfetol (JZP-110) in the treatment of excessive sleepiness in participants with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2020; 43(2): doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz220.

7 Dauvilliers, et al. Pitolisant versus placebo or modafinil in patients with narcolepsy: a double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(11):1068-1075. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70225-4.

8 Dauvilliers, et al. Pitolisant for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea patients refusing CPAP: A randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201907-1284OC.

9 Miglis, et al. Frequency and severity of autonomic symptoms in idiopathic hypersomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020; 16(5):749-756. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8344.

Coronavirus-associated aspergillosis increased 30-day mortality risk

Researchers are beginning to make some headway in identifying the role of secondary infections in the course and outcomes of COVID-19.

Patients who are on ventilatory support for severe COVID-19 infections appear to be at high risk for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, which in a small prospective study was associated with a more than threefold risk for 30-day mortality. The findings were published online in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Among 108 patients with COVID-19 on mechanical ventilation in one of three intensive care units, 30 (27.7%) were diagnosed with coronavirus-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) based on consensus definitions similar to those used to diagnose influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA).

Of the patients with CAPA, 44% died within 30 days of ICU admission, compared with 19% of patients who did not meet the criteria for aspergillosis (P = .002). This difference translated into an odds ratio (OR) for death with CAPA of 3.55 (P = .014), reported Michele Bartoletti, MD, PhD, of the infectious diseases unit at Sant’Orsola Malpighi Hospital in Bologna, Italy, and colleagues.

When the investigators applied a proposed definition of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, or “PIPA” to the same patients, the 30-day mortality rate jumped to 74% vs. 26% for patients without PIPA (P < .001), with an OR of 11.60 (P < .001). “We found a high incidence of CAPA among critically ill COVID-19 patients and that its occurrence seems to change the natural history of disease,” they wrote.

“[T]he study from Bartoletti et al. alerts the clinical audience to be aware of CAPA and take appropriate (and where needed repetitive) actions that fits their clinical setting,” Roger J. Brüggemann, PharmD, of the department of pharmacy, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and colleagues wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

Diagnosis challenging

At the best of times, the diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis is difficult, subject to both false-positive and false-negative results, said a critical care specialist who was not involved in the study.

“Critically ill patients are susceptible to having aspergillus, so in reading the article, my only concerns are that I don’t know how accurate the testing is, and I don’t know if their population is truly different from a general population of patients in the ICU,” Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, FCCP, associate director of medical critical care at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, said in an interview.

As seen in ICU patients with severe influenza or other viral infections, patients with severe COVID-19 disease are susceptible to secondary infections, he said, making it difficult to know whether the worse outcomes seen in patients with COVID-19 and presumed aspergillosis are a reflection of their being more critically ill or whether the secondary infections themselves account for the difference in mortality.

Three ICUs

Dr. Bartoletti and colleagues conducted a study on all adult patients with microbiologically confirmed COVID-19 receiving mechanical ventilation in three ICUs in Bologna.

All patients included in the study were screened for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with bronchoalveolar lavage and galactomannan detection and cultures. The lavage was performed on ICU admission, one day from the first day of mechanical ventilation, and if patients had evidence of clinical disease progression.

Samples that tested positive for galactomannan, a component of the aspergillus cell wall, were stored and later analyzed with a commercial quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for aspergillus; these results were not reported to clinicians on the patient floors.

The investigators defined invasive pulmonary aspergillosis according to a recently proposed definition for CAPA. This definition applies to COVID-19–positive patients admitted to an ICU with pulmonary infiltrates and at least one of the following:

- A serum galactomannan > 0.5.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan > 1.0.

- Positive aspergillus bronchoalveolar lavage culture or cavitating infiltrate not attributed to another cause in the area of the pulmonary infiltrate.

They compared the CAPA diagnostic criteria with those of PIPA criteria as described by Stijn J. Blot, PhD, and colleagues in study published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (2012 Jul 1;186(1):56-64).

A total of 108 patients were screened for aspergillosis, with a median age of 64. The majority of patients (78%) were male. The median age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index was 2.5 (range 1-4). The median Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at ICU admission was 4 (range 3-5).

As noted, probable aspergillosis by CAPA criteria was diagnosed in 30 patients (27.7%), with the diagnosis made after a median of 4 days after intubation and a median of 14 days from onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

The incidence rate of probable CAPA was 38.83 per 10,000 ICU patient days.

A comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with and without probable CAPA showed that only chronic steroid therapy at ≥ 16 mg/day prednisone for at least 15 days was significantly associated with risk for CAPA (P = .02).

At a median follow-up of 31 days, 54 patients (50%) had been discharged, 44 (41%) had died, and the remaining patients were still on follow-up.

As noted before, the mortality rate with 30 days of ICU admission was 44% for patients with probable CAPA vs. 19% for patients without. Among patients deemed to have PIPA, 74% died within 30 days of admission, compared with 26% without PIPA.

In a logistic regression model, the association of CAPA with increased risk for 30-day mortality remained even after adjustment for the need for renal replacement therapy (OR 3.02, P = .015) and SOFA score at ICU admission (OR 1.38, P = .004).

In a logistic regression using the PIPA rather than CAPA definition, the OR for 30-day mortality was 11.60 (P = .001).

Prognostic marker

The investigators noted that bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan index appeared to be predictive of death. Each 1-point increase in the index was associated with 1.41-fold increase in the risk for 30-day mortality (P = .0070), a relationship that held up after adjustment for age, need for renal replacement therapy, and SOFA score.

Sixteen patients who met the CAPA definition received antifungal therapy, primarily voriconazole. The use of voriconazole was associated with a nonsignificant trend toward lower mortality.

They noted that the heavy use of immunomodulating agents in the patients in their study may have contributed to the high prevalence of CAPA.

Dr. Ouellette agreed that many of the therapies used to treat COVID-19 in the ICU are experimental, and that agents used to suppress the cytokine storm that is believed to contribute to disease severity may increase risk for secondary infections such as invasive aspergillosis.

“Many of our treatments may be associated with adverse consequences,” he said. “There is a trend toward treating patients with COVID-19 pneumonia with corticosteroids, and certainly that could have an immunosuppressant effect and predispose patients to secondary infections.”

He noted that the World Health Organization recommendations current in March 2020, when the pandemic began in earnest in the United States, advised against the use of corticosteroids, likely because of a lack of evidence of efficacy and concerns about risk for secondary infections.

“Regardless of the strategic choice made, all efforts should be put into improving our ability to reliably identify patients that may benefit from therapeutic interventions, which include host and risk factors, clinical factors and CAPA disease markers,” Dr. Brüggemann and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

The study was performed without external funding. The authors and Dr. Ouellette reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Brüggemann and coauthors report grants and/or personal fees from various companies outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Bartoletti M et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1065.

Researchers are beginning to make some headway in identifying the role of secondary infections in the course and outcomes of COVID-19.

Patients who are on ventilatory support for severe COVID-19 infections appear to be at high risk for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, which in a small prospective study was associated with a more than threefold risk for 30-day mortality. The findings were published online in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Among 108 patients with COVID-19 on mechanical ventilation in one of three intensive care units, 30 (27.7%) were diagnosed with coronavirus-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) based on consensus definitions similar to those used to diagnose influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA).

Of the patients with CAPA, 44% died within 30 days of ICU admission, compared with 19% of patients who did not meet the criteria for aspergillosis (P = .002). This difference translated into an odds ratio (OR) for death with CAPA of 3.55 (P = .014), reported Michele Bartoletti, MD, PhD, of the infectious diseases unit at Sant’Orsola Malpighi Hospital in Bologna, Italy, and colleagues.

When the investigators applied a proposed definition of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, or “PIPA” to the same patients, the 30-day mortality rate jumped to 74% vs. 26% for patients without PIPA (P < .001), with an OR of 11.60 (P < .001). “We found a high incidence of CAPA among critically ill COVID-19 patients and that its occurrence seems to change the natural history of disease,” they wrote.

“[T]he study from Bartoletti et al. alerts the clinical audience to be aware of CAPA and take appropriate (and where needed repetitive) actions that fits their clinical setting,” Roger J. Brüggemann, PharmD, of the department of pharmacy, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and colleagues wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

Diagnosis challenging

At the best of times, the diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis is difficult, subject to both false-positive and false-negative results, said a critical care specialist who was not involved in the study.

“Critically ill patients are susceptible to having aspergillus, so in reading the article, my only concerns are that I don’t know how accurate the testing is, and I don’t know if their population is truly different from a general population of patients in the ICU,” Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, FCCP, associate director of medical critical care at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, said in an interview.

As seen in ICU patients with severe influenza or other viral infections, patients with severe COVID-19 disease are susceptible to secondary infections, he said, making it difficult to know whether the worse outcomes seen in patients with COVID-19 and presumed aspergillosis are a reflection of their being more critically ill or whether the secondary infections themselves account for the difference in mortality.

Three ICUs

Dr. Bartoletti and colleagues conducted a study on all adult patients with microbiologically confirmed COVID-19 receiving mechanical ventilation in three ICUs in Bologna.

All patients included in the study were screened for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with bronchoalveolar lavage and galactomannan detection and cultures. The lavage was performed on ICU admission, one day from the first day of mechanical ventilation, and if patients had evidence of clinical disease progression.

Samples that tested positive for galactomannan, a component of the aspergillus cell wall, were stored and later analyzed with a commercial quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for aspergillus; these results were not reported to clinicians on the patient floors.

The investigators defined invasive pulmonary aspergillosis according to a recently proposed definition for CAPA. This definition applies to COVID-19–positive patients admitted to an ICU with pulmonary infiltrates and at least one of the following:

- A serum galactomannan > 0.5.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan > 1.0.

- Positive aspergillus bronchoalveolar lavage culture or cavitating infiltrate not attributed to another cause in the area of the pulmonary infiltrate.

They compared the CAPA diagnostic criteria with those of PIPA criteria as described by Stijn J. Blot, PhD, and colleagues in study published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (2012 Jul 1;186(1):56-64).

A total of 108 patients were screened for aspergillosis, with a median age of 64. The majority of patients (78%) were male. The median age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index was 2.5 (range 1-4). The median Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at ICU admission was 4 (range 3-5).

As noted, probable aspergillosis by CAPA criteria was diagnosed in 30 patients (27.7%), with the diagnosis made after a median of 4 days after intubation and a median of 14 days from onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

The incidence rate of probable CAPA was 38.83 per 10,000 ICU patient days.

A comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with and without probable CAPA showed that only chronic steroid therapy at ≥ 16 mg/day prednisone for at least 15 days was significantly associated with risk for CAPA (P = .02).

At a median follow-up of 31 days, 54 patients (50%) had been discharged, 44 (41%) had died, and the remaining patients were still on follow-up.

As noted before, the mortality rate with 30 days of ICU admission was 44% for patients with probable CAPA vs. 19% for patients without. Among patients deemed to have PIPA, 74% died within 30 days of admission, compared with 26% without PIPA.

In a logistic regression model, the association of CAPA with increased risk for 30-day mortality remained even after adjustment for the need for renal replacement therapy (OR 3.02, P = .015) and SOFA score at ICU admission (OR 1.38, P = .004).

In a logistic regression using the PIPA rather than CAPA definition, the OR for 30-day mortality was 11.60 (P = .001).

Prognostic marker

The investigators noted that bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan index appeared to be predictive of death. Each 1-point increase in the index was associated with 1.41-fold increase in the risk for 30-day mortality (P = .0070), a relationship that held up after adjustment for age, need for renal replacement therapy, and SOFA score.

Sixteen patients who met the CAPA definition received antifungal therapy, primarily voriconazole. The use of voriconazole was associated with a nonsignificant trend toward lower mortality.

They noted that the heavy use of immunomodulating agents in the patients in their study may have contributed to the high prevalence of CAPA.

Dr. Ouellette agreed that many of the therapies used to treat COVID-19 in the ICU are experimental, and that agents used to suppress the cytokine storm that is believed to contribute to disease severity may increase risk for secondary infections such as invasive aspergillosis.

“Many of our treatments may be associated with adverse consequences,” he said. “There is a trend toward treating patients with COVID-19 pneumonia with corticosteroids, and certainly that could have an immunosuppressant effect and predispose patients to secondary infections.”

He noted that the World Health Organization recommendations current in March 2020, when the pandemic began in earnest in the United States, advised against the use of corticosteroids, likely because of a lack of evidence of efficacy and concerns about risk for secondary infections.

“Regardless of the strategic choice made, all efforts should be put into improving our ability to reliably identify patients that may benefit from therapeutic interventions, which include host and risk factors, clinical factors and CAPA disease markers,” Dr. Brüggemann and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

The study was performed without external funding. The authors and Dr. Ouellette reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Brüggemann and coauthors report grants and/or personal fees from various companies outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Bartoletti M et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1065.

Researchers are beginning to make some headway in identifying the role of secondary infections in the course and outcomes of COVID-19.

Patients who are on ventilatory support for severe COVID-19 infections appear to be at high risk for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, which in a small prospective study was associated with a more than threefold risk for 30-day mortality. The findings were published online in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Among 108 patients with COVID-19 on mechanical ventilation in one of three intensive care units, 30 (27.7%) were diagnosed with coronavirus-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) based on consensus definitions similar to those used to diagnose influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA).

Of the patients with CAPA, 44% died within 30 days of ICU admission, compared with 19% of patients who did not meet the criteria for aspergillosis (P = .002). This difference translated into an odds ratio (OR) for death with CAPA of 3.55 (P = .014), reported Michele Bartoletti, MD, PhD, of the infectious diseases unit at Sant’Orsola Malpighi Hospital in Bologna, Italy, and colleagues.

When the investigators applied a proposed definition of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, or “PIPA” to the same patients, the 30-day mortality rate jumped to 74% vs. 26% for patients without PIPA (P < .001), with an OR of 11.60 (P < .001). “We found a high incidence of CAPA among critically ill COVID-19 patients and that its occurrence seems to change the natural history of disease,” they wrote.

“[T]he study from Bartoletti et al. alerts the clinical audience to be aware of CAPA and take appropriate (and where needed repetitive) actions that fits their clinical setting,” Roger J. Brüggemann, PharmD, of the department of pharmacy, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and colleagues wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

Diagnosis challenging

At the best of times, the diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis is difficult, subject to both false-positive and false-negative results, said a critical care specialist who was not involved in the study.

“Critically ill patients are susceptible to having aspergillus, so in reading the article, my only concerns are that I don’t know how accurate the testing is, and I don’t know if their population is truly different from a general population of patients in the ICU,” Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, FCCP, associate director of medical critical care at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, said in an interview.

As seen in ICU patients with severe influenza or other viral infections, patients with severe COVID-19 disease are susceptible to secondary infections, he said, making it difficult to know whether the worse outcomes seen in patients with COVID-19 and presumed aspergillosis are a reflection of their being more critically ill or whether the secondary infections themselves account for the difference in mortality.

Three ICUs

Dr. Bartoletti and colleagues conducted a study on all adult patients with microbiologically confirmed COVID-19 receiving mechanical ventilation in three ICUs in Bologna.

All patients included in the study were screened for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with bronchoalveolar lavage and galactomannan detection and cultures. The lavage was performed on ICU admission, one day from the first day of mechanical ventilation, and if patients had evidence of clinical disease progression.

Samples that tested positive for galactomannan, a component of the aspergillus cell wall, were stored and later analyzed with a commercial quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for aspergillus; these results were not reported to clinicians on the patient floors.

The investigators defined invasive pulmonary aspergillosis according to a recently proposed definition for CAPA. This definition applies to COVID-19–positive patients admitted to an ICU with pulmonary infiltrates and at least one of the following:

- A serum galactomannan > 0.5.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan > 1.0.

- Positive aspergillus bronchoalveolar lavage culture or cavitating infiltrate not attributed to another cause in the area of the pulmonary infiltrate.

They compared the CAPA diagnostic criteria with those of PIPA criteria as described by Stijn J. Blot, PhD, and colleagues in study published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (2012 Jul 1;186(1):56-64).

A total of 108 patients were screened for aspergillosis, with a median age of 64. The majority of patients (78%) were male. The median age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index was 2.5 (range 1-4). The median Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at ICU admission was 4 (range 3-5).

As noted, probable aspergillosis by CAPA criteria was diagnosed in 30 patients (27.7%), with the diagnosis made after a median of 4 days after intubation and a median of 14 days from onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

The incidence rate of probable CAPA was 38.83 per 10,000 ICU patient days.

A comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with and without probable CAPA showed that only chronic steroid therapy at ≥ 16 mg/day prednisone for at least 15 days was significantly associated with risk for CAPA (P = .02).

At a median follow-up of 31 days, 54 patients (50%) had been discharged, 44 (41%) had died, and the remaining patients were still on follow-up.

As noted before, the mortality rate with 30 days of ICU admission was 44% for patients with probable CAPA vs. 19% for patients without. Among patients deemed to have PIPA, 74% died within 30 days of admission, compared with 26% without PIPA.

In a logistic regression model, the association of CAPA with increased risk for 30-day mortality remained even after adjustment for the need for renal replacement therapy (OR 3.02, P = .015) and SOFA score at ICU admission (OR 1.38, P = .004).

In a logistic regression using the PIPA rather than CAPA definition, the OR for 30-day mortality was 11.60 (P = .001).

Prognostic marker

The investigators noted that bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan index appeared to be predictive of death. Each 1-point increase in the index was associated with 1.41-fold increase in the risk for 30-day mortality (P = .0070), a relationship that held up after adjustment for age, need for renal replacement therapy, and SOFA score.

Sixteen patients who met the CAPA definition received antifungal therapy, primarily voriconazole. The use of voriconazole was associated with a nonsignificant trend toward lower mortality.

They noted that the heavy use of immunomodulating agents in the patients in their study may have contributed to the high prevalence of CAPA.

Dr. Ouellette agreed that many of the therapies used to treat COVID-19 in the ICU are experimental, and that agents used to suppress the cytokine storm that is believed to contribute to disease severity may increase risk for secondary infections such as invasive aspergillosis.

“Many of our treatments may be associated with adverse consequences,” he said. “There is a trend toward treating patients with COVID-19 pneumonia with corticosteroids, and certainly that could have an immunosuppressant effect and predispose patients to secondary infections.”

He noted that the World Health Organization recommendations current in March 2020, when the pandemic began in earnest in the United States, advised against the use of corticosteroids, likely because of a lack of evidence of efficacy and concerns about risk for secondary infections.

“Regardless of the strategic choice made, all efforts should be put into improving our ability to reliably identify patients that may benefit from therapeutic interventions, which include host and risk factors, clinical factors and CAPA disease markers,” Dr. Brüggemann and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

The study was performed without external funding. The authors and Dr. Ouellette reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Brüggemann and coauthors report grants and/or personal fees from various companies outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Bartoletti M et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1065.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

First evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in heart cells

SARS-CoV-2 has been found in cardiac tissue of a child from Brazil with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) related to COVID-19 who presented with myocarditis and died of heart failure.

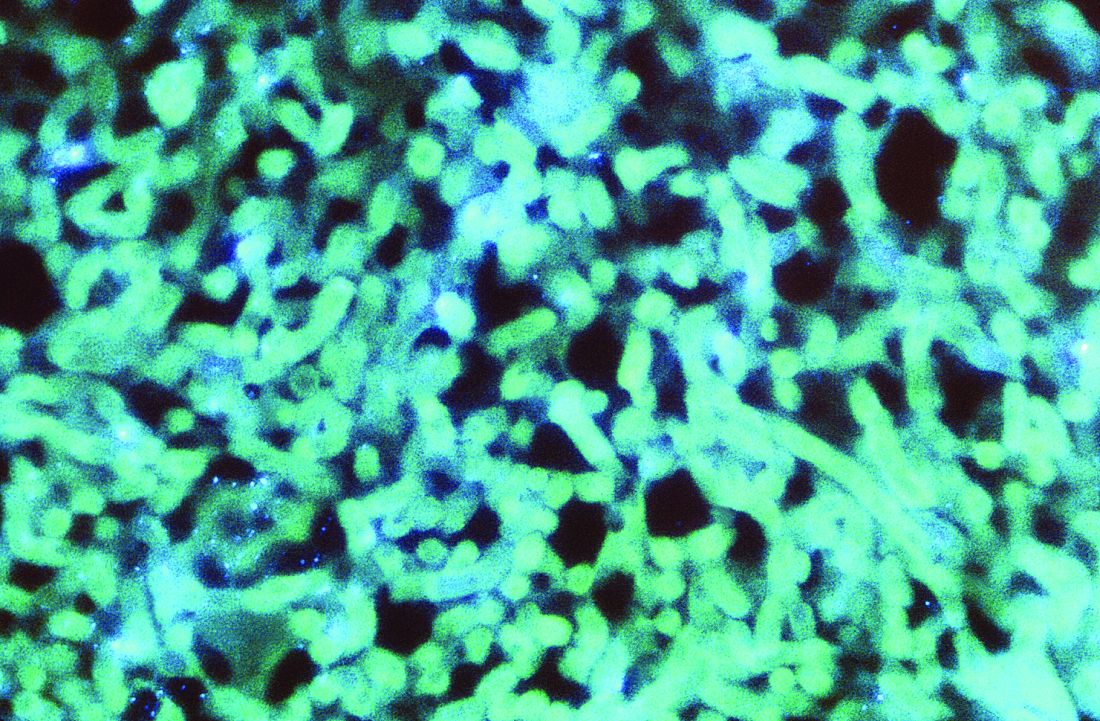

It’s believed to be the first evidence of direct infection of heart muscle cells by the virus; viral particles were identified in different cell lineages of the heart, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and inflammatory cells.

The case was described in a report published online August 20 in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

“The presence of the virus in various cell types of cardiac tissue, as evidenced by electron microscopy, shows that myocarditis in this case is likely a direct inflammatory response to the virus infection in the heart,” first author Marisa Dolhnikoff, MD, department of pathology, University of São Paulo, said in an interview.

There have been previous reports in adults with COVID-19 of both SARS-CoV-2 RNA by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and viral particles by electron microscopy in cardiac tissue from endomyocardial specimens, the researchers noted. One of these reports, published in April by Tavazzi and colleagues, “detected viral particles in cardiac macrophages in an adult patient with acute cardiac injury associated with COVID-19; no viral particles were seen in cardiomyocytes or endothelial cells.

“Our case report is the first to our knowledge to document the presence of viral particles in the cardiac tissue of a child affected by MIS-C,” they added. “Moreover, viral particles were identified in different cell lineages of the heart, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and inflammatory cells.”

‘Concerning’ case report

“This is a concerning report as it shows for the first time that the virus can actually invade the heart muscle cells themselves,” C. Michael Gibson, MD, CEO of the Baim Institute for Clinical Research in Boston, said in an interview.

“Previous reports of COVID-19 and the heart found that the virus was in the area outside the heart muscle cells. We do not know yet the relative contribution of the inflammatory cells invading the heart, the release of blood-borne inflammatory mediators, and the virus inside the heart muscle cells themselves to heart damage,” Dr. Gibson said.

The patient was a previously healthy 11-year-old girl of African descent with MIS-C related to COVID-19. She developed cardiac failure and died after 1 day in the hospital, despite aggressive treatment.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected on a postmortem nasopharyngeal swab and in cardiac and pulmonary tissues by RT-PCR.

Postmortem ultrasound examination of the heart showed a “hyperechogenic and diffusely thickened endocardium (mean thickness, 10 mm), a thickened myocardium (18 mm thick in the left ventricle), and a small pericardial effusion,” Dr. Dolhnikoff and colleagues reported.

Histopathologic exam revealed myocarditis, pericarditis, and endocarditis characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells. Inflammation was mainly interstitial and perivascular, associated with foci of cardiomyocyte necrosis and was mainly composed of CD68+ macrophages, a few CD45+ lymphocytes, and a few neutrophils and eosinophils.

Electron microscopy of cardiac tissue revealed spherical viral particles in shape and size consistent with the Coronaviridae family in the extracellular compartment and within cardiomyocytes, capillary endothelial cells, endocardium endothelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and fibroblasts.

Microthrombi in the pulmonary arterioles and renal glomerular capillaries were also seen at autopsy. SARS-CoV-2–associated pneumonia was mild.

Lymphoid depletion and signs of hemophagocytosis were observed in the spleen and lymph nodes. Acute tubular necrosis in the kidneys and hepatic centrilobular necrosis, secondary to shock, were also seen. Brain tissue showed microglial reactivity.

“Fortunately, MIS-C is a rare event and, although it can be severe and life threatening, most children recover,” Dr. Dolhnikoff commented.

“This case report comes at a time when the scientific community around the world calls attention to MIS-C and the need for it to be quickly recognized and treated by the pediatric community. Evidence of a direct relation between the virus and myocarditis confirms that MIS-C is one of the possible forms of presentation of COVID-19 and that the heart may be the target organ. It also alerts clinicians to possible cardiac sequelae in these children,” she added.

Experts weigh in

Scott Aydin, MD, medical director of pediatric cardiac intensive care, Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York City, said that this case report is “unfortunately not all that surprising.

“Since the initial presentations of MIS-C several months ago, we have suspected mechanisms of direct and indirect injury to the myocardium. This important work is just the next step in further understanding the mechanisms of how COVID-19 creates havoc in the human body and the choices of possible therapies we have to treat children with COVID-19 and MIS-C,” said Dr. Aydin, who was not involved with the case report.

Anish Koka, MD, a cardiologist in private practice in Philadelphia, noted that, in these cases, endomyocardial biopsy is “rarely done because it is fairly invasive, but even when it has been done, the pathologic findings are of widespread inflammation rather than virus-induced cell necrosis.”

“While reports like this are sure to spawn viral tweets, it’s vital to understand that it’s not unusual to find widespread organ dissemination of virus in very sick patients. This does not mean that the virus is causing dysfunction of the organ it happens to be found in,” Dr. Koka said in an interview.

He noted that, in the case of the young girl who died, it took high PCR-cycle threshold values to isolate virus from the lung and heart samples.

“This means there was a low viral load in both organs, supporting the theory of SARS-CoV-2 as a potential trigger of a widespread inflammatory response that results in organ damage, rather than the virus itself infecting and destroying organs,” said Dr. Koka, who was also not associated with the case report.

This research had no specific funding. The authors declared no competing interests. Dr. Aydin disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Koka disclosed financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Jardiance.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SARS-CoV-2 has been found in cardiac tissue of a child from Brazil with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) related to COVID-19 who presented with myocarditis and died of heart failure.

It’s believed to be the first evidence of direct infection of heart muscle cells by the virus; viral particles were identified in different cell lineages of the heart, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and inflammatory cells.

The case was described in a report published online August 20 in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

“The presence of the virus in various cell types of cardiac tissue, as evidenced by electron microscopy, shows that myocarditis in this case is likely a direct inflammatory response to the virus infection in the heart,” first author Marisa Dolhnikoff, MD, department of pathology, University of São Paulo, said in an interview.

There have been previous reports in adults with COVID-19 of both SARS-CoV-2 RNA by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and viral particles by electron microscopy in cardiac tissue from endomyocardial specimens, the researchers noted. One of these reports, published in April by Tavazzi and colleagues, “detected viral particles in cardiac macrophages in an adult patient with acute cardiac injury associated with COVID-19; no viral particles were seen in cardiomyocytes or endothelial cells.

“Our case report is the first to our knowledge to document the presence of viral particles in the cardiac tissue of a child affected by MIS-C,” they added. “Moreover, viral particles were identified in different cell lineages of the heart, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and inflammatory cells.”

‘Concerning’ case report

“This is a concerning report as it shows for the first time that the virus can actually invade the heart muscle cells themselves,” C. Michael Gibson, MD, CEO of the Baim Institute for Clinical Research in Boston, said in an interview.

“Previous reports of COVID-19 and the heart found that the virus was in the area outside the heart muscle cells. We do not know yet the relative contribution of the inflammatory cells invading the heart, the release of blood-borne inflammatory mediators, and the virus inside the heart muscle cells themselves to heart damage,” Dr. Gibson said.

The patient was a previously healthy 11-year-old girl of African descent with MIS-C related to COVID-19. She developed cardiac failure and died after 1 day in the hospital, despite aggressive treatment.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected on a postmortem nasopharyngeal swab and in cardiac and pulmonary tissues by RT-PCR.

Postmortem ultrasound examination of the heart showed a “hyperechogenic and diffusely thickened endocardium (mean thickness, 10 mm), a thickened myocardium (18 mm thick in the left ventricle), and a small pericardial effusion,” Dr. Dolhnikoff and colleagues reported.

Histopathologic exam revealed myocarditis, pericarditis, and endocarditis characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells. Inflammation was mainly interstitial and perivascular, associated with foci of cardiomyocyte necrosis and was mainly composed of CD68+ macrophages, a few CD45+ lymphocytes, and a few neutrophils and eosinophils.

Electron microscopy of cardiac tissue revealed spherical viral particles in shape and size consistent with the Coronaviridae family in the extracellular compartment and within cardiomyocytes, capillary endothelial cells, endocardium endothelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and fibroblasts.

Microthrombi in the pulmonary arterioles and renal glomerular capillaries were also seen at autopsy. SARS-CoV-2–associated pneumonia was mild.

Lymphoid depletion and signs of hemophagocytosis were observed in the spleen and lymph nodes. Acute tubular necrosis in the kidneys and hepatic centrilobular necrosis, secondary to shock, were also seen. Brain tissue showed microglial reactivity.

“Fortunately, MIS-C is a rare event and, although it can be severe and life threatening, most children recover,” Dr. Dolhnikoff commented.

“This case report comes at a time when the scientific community around the world calls attention to MIS-C and the need for it to be quickly recognized and treated by the pediatric community. Evidence of a direct relation between the virus and myocarditis confirms that MIS-C is one of the possible forms of presentation of COVID-19 and that the heart may be the target organ. It also alerts clinicians to possible cardiac sequelae in these children,” she added.

Experts weigh in

Scott Aydin, MD, medical director of pediatric cardiac intensive care, Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York City, said that this case report is “unfortunately not all that surprising.

“Since the initial presentations of MIS-C several months ago, we have suspected mechanisms of direct and indirect injury to the myocardium. This important work is just the next step in further understanding the mechanisms of how COVID-19 creates havoc in the human body and the choices of possible therapies we have to treat children with COVID-19 and MIS-C,” said Dr. Aydin, who was not involved with the case report.

Anish Koka, MD, a cardiologist in private practice in Philadelphia, noted that, in these cases, endomyocardial biopsy is “rarely done because it is fairly invasive, but even when it has been done, the pathologic findings are of widespread inflammation rather than virus-induced cell necrosis.”

“While reports like this are sure to spawn viral tweets, it’s vital to understand that it’s not unusual to find widespread organ dissemination of virus in very sick patients. This does not mean that the virus is causing dysfunction of the organ it happens to be found in,” Dr. Koka said in an interview.

He noted that, in the case of the young girl who died, it took high PCR-cycle threshold values to isolate virus from the lung and heart samples.

“This means there was a low viral load in both organs, supporting the theory of SARS-CoV-2 as a potential trigger of a widespread inflammatory response that results in organ damage, rather than the virus itself infecting and destroying organs,” said Dr. Koka, who was also not associated with the case report.

This research had no specific funding. The authors declared no competing interests. Dr. Aydin disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Koka disclosed financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Jardiance.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SARS-CoV-2 has been found in cardiac tissue of a child from Brazil with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) related to COVID-19 who presented with myocarditis and died of heart failure.

It’s believed to be the first evidence of direct infection of heart muscle cells by the virus; viral particles were identified in different cell lineages of the heart, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and inflammatory cells.

The case was described in a report published online August 20 in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

“The presence of the virus in various cell types of cardiac tissue, as evidenced by electron microscopy, shows that myocarditis in this case is likely a direct inflammatory response to the virus infection in the heart,” first author Marisa Dolhnikoff, MD, department of pathology, University of São Paulo, said in an interview.

There have been previous reports in adults with COVID-19 of both SARS-CoV-2 RNA by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and viral particles by electron microscopy in cardiac tissue from endomyocardial specimens, the researchers noted. One of these reports, published in April by Tavazzi and colleagues, “detected viral particles in cardiac macrophages in an adult patient with acute cardiac injury associated with COVID-19; no viral particles were seen in cardiomyocytes or endothelial cells.

“Our case report is the first to our knowledge to document the presence of viral particles in the cardiac tissue of a child affected by MIS-C,” they added. “Moreover, viral particles were identified in different cell lineages of the heart, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and inflammatory cells.”

‘Concerning’ case report

“This is a concerning report as it shows for the first time that the virus can actually invade the heart muscle cells themselves,” C. Michael Gibson, MD, CEO of the Baim Institute for Clinical Research in Boston, said in an interview.

“Previous reports of COVID-19 and the heart found that the virus was in the area outside the heart muscle cells. We do not know yet the relative contribution of the inflammatory cells invading the heart, the release of blood-borne inflammatory mediators, and the virus inside the heart muscle cells themselves to heart damage,” Dr. Gibson said.

The patient was a previously healthy 11-year-old girl of African descent with MIS-C related to COVID-19. She developed cardiac failure and died after 1 day in the hospital, despite aggressive treatment.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected on a postmortem nasopharyngeal swab and in cardiac and pulmonary tissues by RT-PCR.

Postmortem ultrasound examination of the heart showed a “hyperechogenic and diffusely thickened endocardium (mean thickness, 10 mm), a thickened myocardium (18 mm thick in the left ventricle), and a small pericardial effusion,” Dr. Dolhnikoff and colleagues reported.

Histopathologic exam revealed myocarditis, pericarditis, and endocarditis characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells. Inflammation was mainly interstitial and perivascular, associated with foci of cardiomyocyte necrosis and was mainly composed of CD68+ macrophages, a few CD45+ lymphocytes, and a few neutrophils and eosinophils.

Electron microscopy of cardiac tissue revealed spherical viral particles in shape and size consistent with the Coronaviridae family in the extracellular compartment and within cardiomyocytes, capillary endothelial cells, endocardium endothelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and fibroblasts.

Microthrombi in the pulmonary arterioles and renal glomerular capillaries were also seen at autopsy. SARS-CoV-2–associated pneumonia was mild.

Lymphoid depletion and signs of hemophagocytosis were observed in the spleen and lymph nodes. Acute tubular necrosis in the kidneys and hepatic centrilobular necrosis, secondary to shock, were also seen. Brain tissue showed microglial reactivity.

“Fortunately, MIS-C is a rare event and, although it can be severe and life threatening, most children recover,” Dr. Dolhnikoff commented.

“This case report comes at a time when the scientific community around the world calls attention to MIS-C and the need for it to be quickly recognized and treated by the pediatric community. Evidence of a direct relation between the virus and myocarditis confirms that MIS-C is one of the possible forms of presentation of COVID-19 and that the heart may be the target organ. It also alerts clinicians to possible cardiac sequelae in these children,” she added.

Experts weigh in

Scott Aydin, MD, medical director of pediatric cardiac intensive care, Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York City, said that this case report is “unfortunately not all that surprising.

“Since the initial presentations of MIS-C several months ago, we have suspected mechanisms of direct and indirect injury to the myocardium. This important work is just the next step in further understanding the mechanisms of how COVID-19 creates havoc in the human body and the choices of possible therapies we have to treat children with COVID-19 and MIS-C,” said Dr. Aydin, who was not involved with the case report.

Anish Koka, MD, a cardiologist in private practice in Philadelphia, noted that, in these cases, endomyocardial biopsy is “rarely done because it is fairly invasive, but even when it has been done, the pathologic findings are of widespread inflammation rather than virus-induced cell necrosis.”

“While reports like this are sure to spawn viral tweets, it’s vital to understand that it’s not unusual to find widespread organ dissemination of virus in very sick patients. This does not mean that the virus is causing dysfunction of the organ it happens to be found in,” Dr. Koka said in an interview.

He noted that, in the case of the young girl who died, it took high PCR-cycle threshold values to isolate virus from the lung and heart samples.

“This means there was a low viral load in both organs, supporting the theory of SARS-CoV-2 as a potential trigger of a widespread inflammatory response that results in organ damage, rather than the virus itself infecting and destroying organs,” said Dr. Koka, who was also not associated with the case report.

This research had no specific funding. The authors declared no competing interests. Dr. Aydin disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Koka disclosed financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Jardiance.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Famotidine associated with benefits in hospitalized COVID patients in another trial

It also demonstrated lower levels of serum markers for severe disease.

The findings come from an observational study of 83 hospitalized patients that was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

“The mechanism of exactly how famotidine works has yet to be proven,” lead study author Jeffrey F. Mather, MS, said in an interview. “There’s thought that it works directly on the virus, and there is thought that it works through inactivating certain proteases that are required for the virus infection, but I think the most interesting [hypothesis] is by Malone et al. “They’re looking at the blocking of the histamine-2 receptor causing a decrease in the amount of histamine. It’s all speculative, but it will be interesting if that gets worked out.”

In a study that largely mimicked that of an earlier, larger published observational study on the topic (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.053), Mr. Mather and colleagues retrospectively evaluated 878 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and who required admission to Hartford (Conn.) Hospital between Feb. 24, 2020, and May 14, 2020. Patients were classified as receiving famotidine if they were treated with either oral or intravenous drug within 1 week of COVID-19 screening and/or hospital admission. Primary outcomes of interest were in-hospital death as recorded in the discharge of the patients, requirement for mechanical ventilation, and the composite of death or requirement for ventilation. Secondary outcomes of interest were several serum markers of disease activity including white blood cell count, lymphocyte count, and eosinophil count.

Famotidine was administered orally in 83% of the patients and intravenously in the remaining 17%. Mr. Mather, director of data management in the division of research management at Hartford Hospital, and his colleagues reported that 83 of the 878 patients studied (9.5%) received famotidine. Compared with patients not treated with famotidine, those who received the drug were slightly younger (a mean of 64 vs. 68 years, respectively; P = .021); otherwise, there were no differences between the two groups in baseline demographics or in preexisting comorbidities.

The use of famotidine was associated with a decreased risk of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 0.37; P = .021) as well as combined death or intubation (OR, 0.47; P = .040). The outcomes were similar when the researchers performed propensity score matching to adjust for age differences between groups.

In addition, the use of famotidine was associated with lower levels of serum markers for severe disease including lower median peak C-reactive protein levels (9.4 vs. 12.7 mg/dL; P =. 002), lower median procalcitonin levels (0.16 vs. 0.30 ng/mL; P = .004), and a nonsignificant trend to lower median mean ferritin levels (797.5 vs. 964 ng/mL; P = .076).

Logistic regression analysis revealed that use of famotidine was an independent predictor of both lower mortality and combined death/intubation. In addition, predictors of both adverse outcomes included older age, a body mass index of greater than 30 kg/m2, chronic kidney disease, the national early warning score, and a higher neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio.