User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Disparities seen in COVID-19–related avoidance of care

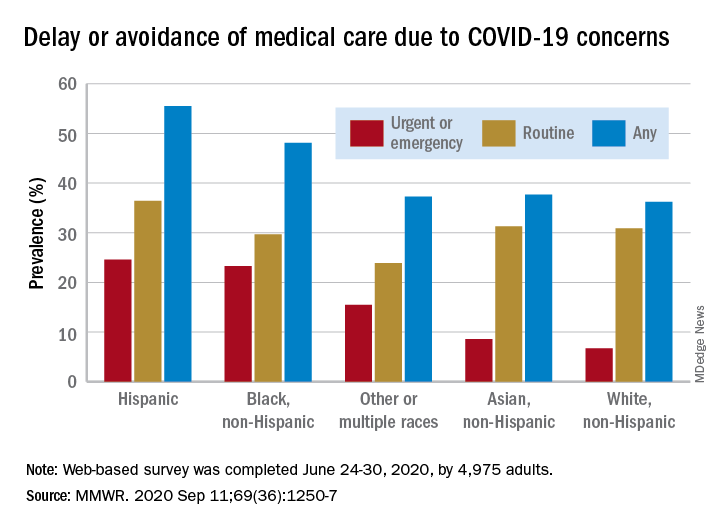

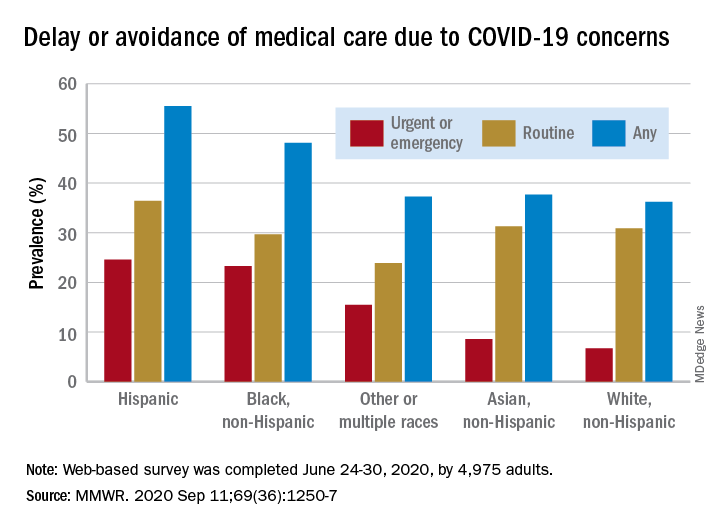

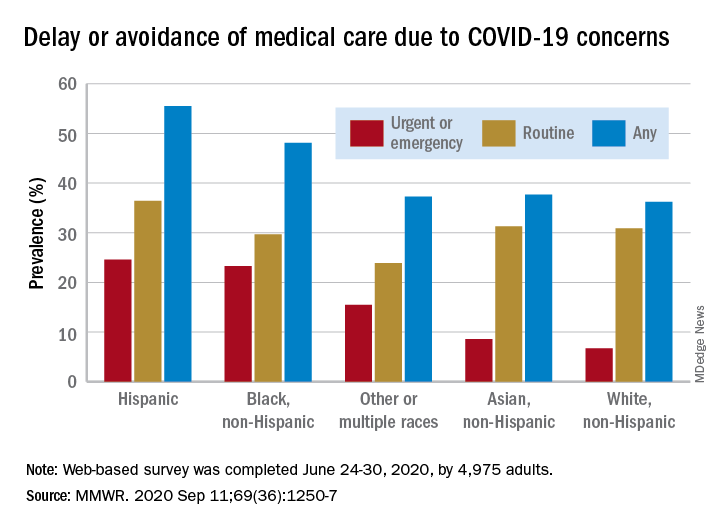

In the early weeks and months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people were trying to avoid the coronavirus by staying away from emergency rooms and medical offices. But how many people is “many”?

Turns out almost 41% of Americans delayed or avoided some form of medical care because of concerns about COVID-19, according to the results of a survey conducted June 24-30 by commercial survey company Qualtrics.

More specifically, the avoidance looks like this: 31.5% of the 4,975 adult respondents had avoided routine care and 12.0% had avoided urgent or emergency care, Mark E. Czeisler and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The two categories were not mutually exclusive since respondents could select both routine care and urgent/emergency care.

There were, however, a number of significant disparities hidden among those numbers for the overall population. Blacks and Hispanics, with respective prevalences of 23.3% and 24.6%, were significantly more likely to delay or avoid urgent/emergency care than were Whites (6.7%), said Mr. Czeisler, a graduate student at Monash University, Melbourne, and associates.

Those differences “are especially concerning given increased COVID-19–associated mortality among Black adults and Hispanic adults,” they noted, adding that “age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates are approximately five times higher among Black persons and four times higher among Hispanic persons than” among Whites.

Other significant disparities in urgent/emergency care avoidance included the following:

- Unpaid caregivers for adults (29.8%) vs. noncaregivers (5.4%).

- Adults with two or more underlying conditions (22.7%) vs. those without such conditions (8.2%).

- Those with a disability (22.8%) vs. those without (8.9%).

- Those with health insurance (12.4%) vs. those without (7.8%).

The highest prevalence for all types of COVID-19–related delay and avoidance came from the adult caregivers (64.3%), followed by those with a disability (60.3%) and adults aged 18-24 years (57.2%). The lowest prevalence numbers were for adults with health insurance (24.8%) and those who were not caregivers for adults (32.2%), Mr. Czeisler and associates reported.

These reports of delayed and avoided care “might reflect adherence to community mitigation efforts such as stay-at-home orders, temporary closures of health facilities, or additional factors. However, if routine care avoidance were to be sustained, adults could miss opportunities for management of chronic conditions, receipt of routine vaccinations, or early detection of new conditions, which might worsen outcomes,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Czeisler ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Sep 11;69(36):1250-7.

In the early weeks and months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people were trying to avoid the coronavirus by staying away from emergency rooms and medical offices. But how many people is “many”?

Turns out almost 41% of Americans delayed or avoided some form of medical care because of concerns about COVID-19, according to the results of a survey conducted June 24-30 by commercial survey company Qualtrics.

More specifically, the avoidance looks like this: 31.5% of the 4,975 adult respondents had avoided routine care and 12.0% had avoided urgent or emergency care, Mark E. Czeisler and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The two categories were not mutually exclusive since respondents could select both routine care and urgent/emergency care.

There were, however, a number of significant disparities hidden among those numbers for the overall population. Blacks and Hispanics, with respective prevalences of 23.3% and 24.6%, were significantly more likely to delay or avoid urgent/emergency care than were Whites (6.7%), said Mr. Czeisler, a graduate student at Monash University, Melbourne, and associates.

Those differences “are especially concerning given increased COVID-19–associated mortality among Black adults and Hispanic adults,” they noted, adding that “age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates are approximately five times higher among Black persons and four times higher among Hispanic persons than” among Whites.

Other significant disparities in urgent/emergency care avoidance included the following:

- Unpaid caregivers for adults (29.8%) vs. noncaregivers (5.4%).

- Adults with two or more underlying conditions (22.7%) vs. those without such conditions (8.2%).

- Those with a disability (22.8%) vs. those without (8.9%).

- Those with health insurance (12.4%) vs. those without (7.8%).

The highest prevalence for all types of COVID-19–related delay and avoidance came from the adult caregivers (64.3%), followed by those with a disability (60.3%) and adults aged 18-24 years (57.2%). The lowest prevalence numbers were for adults with health insurance (24.8%) and those who were not caregivers for adults (32.2%), Mr. Czeisler and associates reported.

These reports of delayed and avoided care “might reflect adherence to community mitigation efforts such as stay-at-home orders, temporary closures of health facilities, or additional factors. However, if routine care avoidance were to be sustained, adults could miss opportunities for management of chronic conditions, receipt of routine vaccinations, or early detection of new conditions, which might worsen outcomes,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Czeisler ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Sep 11;69(36):1250-7.

In the early weeks and months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people were trying to avoid the coronavirus by staying away from emergency rooms and medical offices. But how many people is “many”?

Turns out almost 41% of Americans delayed or avoided some form of medical care because of concerns about COVID-19, according to the results of a survey conducted June 24-30 by commercial survey company Qualtrics.

More specifically, the avoidance looks like this: 31.5% of the 4,975 adult respondents had avoided routine care and 12.0% had avoided urgent or emergency care, Mark E. Czeisler and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The two categories were not mutually exclusive since respondents could select both routine care and urgent/emergency care.

There were, however, a number of significant disparities hidden among those numbers for the overall population. Blacks and Hispanics, with respective prevalences of 23.3% and 24.6%, were significantly more likely to delay or avoid urgent/emergency care than were Whites (6.7%), said Mr. Czeisler, a graduate student at Monash University, Melbourne, and associates.

Those differences “are especially concerning given increased COVID-19–associated mortality among Black adults and Hispanic adults,” they noted, adding that “age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates are approximately five times higher among Black persons and four times higher among Hispanic persons than” among Whites.

Other significant disparities in urgent/emergency care avoidance included the following:

- Unpaid caregivers for adults (29.8%) vs. noncaregivers (5.4%).

- Adults with two or more underlying conditions (22.7%) vs. those without such conditions (8.2%).

- Those with a disability (22.8%) vs. those without (8.9%).

- Those with health insurance (12.4%) vs. those without (7.8%).

The highest prevalence for all types of COVID-19–related delay and avoidance came from the adult caregivers (64.3%), followed by those with a disability (60.3%) and adults aged 18-24 years (57.2%). The lowest prevalence numbers were for adults with health insurance (24.8%) and those who were not caregivers for adults (32.2%), Mr. Czeisler and associates reported.

These reports of delayed and avoided care “might reflect adherence to community mitigation efforts such as stay-at-home orders, temporary closures of health facilities, or additional factors. However, if routine care avoidance were to be sustained, adults could miss opportunities for management of chronic conditions, receipt of routine vaccinations, or early detection of new conditions, which might worsen outcomes,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Czeisler ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Sep 11;69(36):1250-7.

New billing code for added COVID practice expense

The American Medical Association on Sept. 8 announced that a new code, 99072, is intended to cover additional supplies, materials, and clinical staff time over and above those usually included in an office visit when performed during a declared public health emergency, as defined by law, attributable to respiratory-transmitted infectious disease, the AMA said in a release.

Fifty national medical specialty societies and other organizations worked with the AMA’s Specialty Society RVS Update Committee over the summer to collect data on the costs of maintaining safe medical offices during the public health emergency. It has submitted recommendations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services seeking to persuade the federal agencies to recognize the new 99072 payment code.

The intention is to recognize the extra expenses involved in steps now routinely taken to reduce the risk for COVID transmission from office visits, Current Procedural Terminology Editorial Panel Chair Mark S. Synovec, MD, said in an interview. Some practices have adapted by having staff screen patients before they enter offices and making arrangements to keep patients at a safe distance from others during their visits, he said.

“Everyone’s life has significantly changed because of COVID and the health care system has dramatically changed,” Dr. Synovec said. “It was pretty clear that the status quo was not going to work.”

Physician practices will welcome this change, said Veronica Bradley, CPC, a senior industry adviser to the Medical Group Management Association. An office visit that in the past may have involved only basic infection control measures, such as donning a pair of gloves, now may involve clinicians taking the time to put on more extensive protective gear, she said.

“Now they are taking a heck of a lot more precautions, and there’s more time and more supplies being consumed,” Ms. Bradley said in an interview.

Code looks ahead to future use

The AMA explained how this new code differs from CPT code 99070, which is typically reported for supplies and materials that may be used or provided to patients during an office visit.

The new 99072 code applies only during declared public health emergencies and applies only to additional items required to support “a safe in-person provision” of evaluation, treatment, and procedures, the AMA said.

“These items contrast with those typically reported with code 99070, which focuses on additional supplies provided over and above those usually included with a specific service, such as drugs, intravenous catheters, or trays,” the AMA said.

The CPT panel sought to structure the new code for covering COVID practice expenses so that it could not be abused, and also looked ahead to the future, Dr. Synovec said.

“It’s a code that you would put on during a public health emergency as defined by law that would be related to a respiratory-transmitted infectious disease. Obviously we meant it for SARS-CoV-2,” he said. “Hopefully we can go another 100 years before we have another pandemic, but we also wanted to prepare something where if we have another airborne respiratory virus that requires additional practice expenses as seen this time, it would be available for use.”

The AMA also announced a second addition, CPT code 86413, that anticipates greater use of quantitative measurements of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, as opposed to a qualitative assessment (positive/negative) provided by laboratory tests reported by other CPT codes.

More information is available on the AMA website.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Medical Association on Sept. 8 announced that a new code, 99072, is intended to cover additional supplies, materials, and clinical staff time over and above those usually included in an office visit when performed during a declared public health emergency, as defined by law, attributable to respiratory-transmitted infectious disease, the AMA said in a release.

Fifty national medical specialty societies and other organizations worked with the AMA’s Specialty Society RVS Update Committee over the summer to collect data on the costs of maintaining safe medical offices during the public health emergency. It has submitted recommendations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services seeking to persuade the federal agencies to recognize the new 99072 payment code.

The intention is to recognize the extra expenses involved in steps now routinely taken to reduce the risk for COVID transmission from office visits, Current Procedural Terminology Editorial Panel Chair Mark S. Synovec, MD, said in an interview. Some practices have adapted by having staff screen patients before they enter offices and making arrangements to keep patients at a safe distance from others during their visits, he said.

“Everyone’s life has significantly changed because of COVID and the health care system has dramatically changed,” Dr. Synovec said. “It was pretty clear that the status quo was not going to work.”

Physician practices will welcome this change, said Veronica Bradley, CPC, a senior industry adviser to the Medical Group Management Association. An office visit that in the past may have involved only basic infection control measures, such as donning a pair of gloves, now may involve clinicians taking the time to put on more extensive protective gear, she said.

“Now they are taking a heck of a lot more precautions, and there’s more time and more supplies being consumed,” Ms. Bradley said in an interview.

Code looks ahead to future use

The AMA explained how this new code differs from CPT code 99070, which is typically reported for supplies and materials that may be used or provided to patients during an office visit.

The new 99072 code applies only during declared public health emergencies and applies only to additional items required to support “a safe in-person provision” of evaluation, treatment, and procedures, the AMA said.

“These items contrast with those typically reported with code 99070, which focuses on additional supplies provided over and above those usually included with a specific service, such as drugs, intravenous catheters, or trays,” the AMA said.

The CPT panel sought to structure the new code for covering COVID practice expenses so that it could not be abused, and also looked ahead to the future, Dr. Synovec said.

“It’s a code that you would put on during a public health emergency as defined by law that would be related to a respiratory-transmitted infectious disease. Obviously we meant it for SARS-CoV-2,” he said. “Hopefully we can go another 100 years before we have another pandemic, but we also wanted to prepare something where if we have another airborne respiratory virus that requires additional practice expenses as seen this time, it would be available for use.”

The AMA also announced a second addition, CPT code 86413, that anticipates greater use of quantitative measurements of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, as opposed to a qualitative assessment (positive/negative) provided by laboratory tests reported by other CPT codes.

More information is available on the AMA website.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Medical Association on Sept. 8 announced that a new code, 99072, is intended to cover additional supplies, materials, and clinical staff time over and above those usually included in an office visit when performed during a declared public health emergency, as defined by law, attributable to respiratory-transmitted infectious disease, the AMA said in a release.

Fifty national medical specialty societies and other organizations worked with the AMA’s Specialty Society RVS Update Committee over the summer to collect data on the costs of maintaining safe medical offices during the public health emergency. It has submitted recommendations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services seeking to persuade the federal agencies to recognize the new 99072 payment code.

The intention is to recognize the extra expenses involved in steps now routinely taken to reduce the risk for COVID transmission from office visits, Current Procedural Terminology Editorial Panel Chair Mark S. Synovec, MD, said in an interview. Some practices have adapted by having staff screen patients before they enter offices and making arrangements to keep patients at a safe distance from others during their visits, he said.

“Everyone’s life has significantly changed because of COVID and the health care system has dramatically changed,” Dr. Synovec said. “It was pretty clear that the status quo was not going to work.”

Physician practices will welcome this change, said Veronica Bradley, CPC, a senior industry adviser to the Medical Group Management Association. An office visit that in the past may have involved only basic infection control measures, such as donning a pair of gloves, now may involve clinicians taking the time to put on more extensive protective gear, she said.

“Now they are taking a heck of a lot more precautions, and there’s more time and more supplies being consumed,” Ms. Bradley said in an interview.

Code looks ahead to future use

The AMA explained how this new code differs from CPT code 99070, which is typically reported for supplies and materials that may be used or provided to patients during an office visit.

The new 99072 code applies only during declared public health emergencies and applies only to additional items required to support “a safe in-person provision” of evaluation, treatment, and procedures, the AMA said.

“These items contrast with those typically reported with code 99070, which focuses on additional supplies provided over and above those usually included with a specific service, such as drugs, intravenous catheters, or trays,” the AMA said.

The CPT panel sought to structure the new code for covering COVID practice expenses so that it could not be abused, and also looked ahead to the future, Dr. Synovec said.

“It’s a code that you would put on during a public health emergency as defined by law that would be related to a respiratory-transmitted infectious disease. Obviously we meant it for SARS-CoV-2,” he said. “Hopefully we can go another 100 years before we have another pandemic, but we also wanted to prepare something where if we have another airborne respiratory virus that requires additional practice expenses as seen this time, it would be available for use.”

The AMA also announced a second addition, CPT code 86413, that anticipates greater use of quantitative measurements of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, as opposed to a qualitative assessment (positive/negative) provided by laboratory tests reported by other CPT codes.

More information is available on the AMA website.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Distinguishing COVID-19 from flu in kids remains challenging

For children with COVID-19, rates of hospitalization, ICU admission, and ventilator use were similar to those of children with influenza, but rates differed in other respects, according to results of a study published online Sept. 11 in JAMA Network Open.

As winter approaches, distinguishing patients with COVID-19 from those with influenza will become a problem. To assist with that, Xiaoyan Song, PhD, director of the office of infection control and epidemiology at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., and colleagues investigated commonalities and differences between the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 and influenza in children.

“Distinguishing COVID-19 from flu and other respiratory viral infections remains a challenge to clinicians. Although our study showed that patients with COVID-19 were more likely than patients with flu to report fever, gastrointestinal, and other clinical symptoms at the time of diagnosis, the two groups do have many overlapping clinical symptoms,” Dr. Song said. “Until future data show us otherwise, clinicians need to prepare for managing coinfections of COVID-19 with flu and/or other respiratory viral infections in the upcoming flu season.”

The retrospective cohort study included 315 children diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between March 25 and May 15, 2020, and 1,402 children diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed seasonal influenza A or influenza B between Oct. 1, 2019, and June 6, 2020, at Children’s National Hospital. The investigation excluded asymptomatic patients who tested positive for COVID-19.

Patients with COVID-19 and patients with influenza were similar with respect to rates of hospitalization (17% vs. 21%; odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.6-1.1; P = .15), admission to the ICU (6% vs. 7%; OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.3; P = .42), and use of mechanical ventilation (3% vs. 2%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 0.9-2.6; P =.17).

The difference in the duration of ventilation for the two groups was not statistically significant. None of the patients who had COVID-19 or influenza B died, but two patients with influenza A did.

No patients had coinfections, which the researchers attribute to the mid-March shutdown of many schools, which they believe limited the spread of seasonal influenza.

Patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 were older (median age, 9.7 years; range, 0.06-23.2 years) than those hospitalized with either type of influenza (median age, 4.2 years; range, 0.04-23.1). Patients older than 15 years made up 37% of patients with COVID-19 but only 6% of those with influenza.

Among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, 65% had at least one underlying medical condition, compared with 42% of those hospitalized for either type of influenza (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-4.7; P = .002).

The most common underlying condition was neurologic problems from global developmental delay or seizures, identified in 11 patients (20%) hospitalized with COVID-19 and in 24 patients (8%) hospitalized with influenza (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.2; P = .002). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to a history of asthma, cardiac disease, hematologic disease, and cancer.

For both groups, fever and cough were the most frequently reported symptoms at the time of diagnosis. However, more patients hospitalized with COVID-19 reported fever (76% vs. 55%; OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-5.1; P = 01), diarrhea or vomiting (26% vs. 12%; OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-5.0; P = .01), headache (11% vs. 3%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.3-11.5; P = .01), myalgia (22% vs. 7%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.8-8.5; P = .001), or chest pain (11% vs. 3%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.3-11.5; P = .01).

The researchers found no statistically significant differences between the two groups in rates of cough, congestion, sore throat, or shortness of breath.

Comparison of the symptom spectrum between COVID-19 and flu differed with respect to influenza type. More patients with COVID-19 reported fever, cough, diarrhea and vomiting, and myalgia than patients hospitalized with influenza A. But rates of fever, cough, diarrhea or vomiting, headache, or chest pain didn’t differ significantly in patients with COVID-19 and those with influenza B.

Larry K. Kociolek, MD, medical director of infection prevention and control at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, noted the lower age of patients with flu. “Differentiating the two infections, which is difficult if not impossible based on symptoms alone, may have prognostic implications, depending on the age of the child. Because this study was performed outside peak influenza season, when coinfections would be less likely to occur, we must be vigilant about the potential clinical implications of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 coinfection this fall and winter.”

Clinicians will still have to use a combination of symptoms, examinations, and testing to distinguish the two diseases, said Aimee Sznewajs, MD, medical director of the pediatric hospital medicine department at Children’s Minnesota, Minneapolis. “We will continue to test for influenza and COVID-19 prior to hospitalizations and make decisions about whether to hospitalize based on other clinical factors, such as dehydration, oxygen requirement, and vital sign changes.”

Dr. Sznewajs stressed the importance of maintaining public health strategies, including “ensuring all children get the flu vaccine, encouraging mask wearing and hand hygiene, adequate testing to determine which virus is present, and other mitigation measures if the prevalence of COVID-19 is increasing in the community.”

Dr. Song reiterated those points, noting that clinicians need to make the most of the options they have. “Clinicians already have many great tools on hand. It is extremely important to get the flu vaccine now, especially for kids with underlying medical conditions. Diagnostic tests are available for both COVID-19 and flu. Antiviral treatment for flu is available. Judicious use of these tools will protect the health of providers, kids, and well-being at large.”

The authors noted several limitations for the study, including its retrospective design, that the data came from a single center, and that different platforms were used to detect the viruses.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

For children with COVID-19, rates of hospitalization, ICU admission, and ventilator use were similar to those of children with influenza, but rates differed in other respects, according to results of a study published online Sept. 11 in JAMA Network Open.

As winter approaches, distinguishing patients with COVID-19 from those with influenza will become a problem. To assist with that, Xiaoyan Song, PhD, director of the office of infection control and epidemiology at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., and colleagues investigated commonalities and differences between the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 and influenza in children.

“Distinguishing COVID-19 from flu and other respiratory viral infections remains a challenge to clinicians. Although our study showed that patients with COVID-19 were more likely than patients with flu to report fever, gastrointestinal, and other clinical symptoms at the time of diagnosis, the two groups do have many overlapping clinical symptoms,” Dr. Song said. “Until future data show us otherwise, clinicians need to prepare for managing coinfections of COVID-19 with flu and/or other respiratory viral infections in the upcoming flu season.”

The retrospective cohort study included 315 children diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between March 25 and May 15, 2020, and 1,402 children diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed seasonal influenza A or influenza B between Oct. 1, 2019, and June 6, 2020, at Children’s National Hospital. The investigation excluded asymptomatic patients who tested positive for COVID-19.

Patients with COVID-19 and patients with influenza were similar with respect to rates of hospitalization (17% vs. 21%; odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.6-1.1; P = .15), admission to the ICU (6% vs. 7%; OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.3; P = .42), and use of mechanical ventilation (3% vs. 2%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 0.9-2.6; P =.17).

The difference in the duration of ventilation for the two groups was not statistically significant. None of the patients who had COVID-19 or influenza B died, but two patients with influenza A did.

No patients had coinfections, which the researchers attribute to the mid-March shutdown of many schools, which they believe limited the spread of seasonal influenza.

Patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 were older (median age, 9.7 years; range, 0.06-23.2 years) than those hospitalized with either type of influenza (median age, 4.2 years; range, 0.04-23.1). Patients older than 15 years made up 37% of patients with COVID-19 but only 6% of those with influenza.

Among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, 65% had at least one underlying medical condition, compared with 42% of those hospitalized for either type of influenza (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-4.7; P = .002).

The most common underlying condition was neurologic problems from global developmental delay or seizures, identified in 11 patients (20%) hospitalized with COVID-19 and in 24 patients (8%) hospitalized with influenza (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.2; P = .002). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to a history of asthma, cardiac disease, hematologic disease, and cancer.

For both groups, fever and cough were the most frequently reported symptoms at the time of diagnosis. However, more patients hospitalized with COVID-19 reported fever (76% vs. 55%; OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-5.1; P = 01), diarrhea or vomiting (26% vs. 12%; OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-5.0; P = .01), headache (11% vs. 3%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.3-11.5; P = .01), myalgia (22% vs. 7%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.8-8.5; P = .001), or chest pain (11% vs. 3%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.3-11.5; P = .01).

The researchers found no statistically significant differences between the two groups in rates of cough, congestion, sore throat, or shortness of breath.

Comparison of the symptom spectrum between COVID-19 and flu differed with respect to influenza type. More patients with COVID-19 reported fever, cough, diarrhea and vomiting, and myalgia than patients hospitalized with influenza A. But rates of fever, cough, diarrhea or vomiting, headache, or chest pain didn’t differ significantly in patients with COVID-19 and those with influenza B.

Larry K. Kociolek, MD, medical director of infection prevention and control at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, noted the lower age of patients with flu. “Differentiating the two infections, which is difficult if not impossible based on symptoms alone, may have prognostic implications, depending on the age of the child. Because this study was performed outside peak influenza season, when coinfections would be less likely to occur, we must be vigilant about the potential clinical implications of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 coinfection this fall and winter.”

Clinicians will still have to use a combination of symptoms, examinations, and testing to distinguish the two diseases, said Aimee Sznewajs, MD, medical director of the pediatric hospital medicine department at Children’s Minnesota, Minneapolis. “We will continue to test for influenza and COVID-19 prior to hospitalizations and make decisions about whether to hospitalize based on other clinical factors, such as dehydration, oxygen requirement, and vital sign changes.”

Dr. Sznewajs stressed the importance of maintaining public health strategies, including “ensuring all children get the flu vaccine, encouraging mask wearing and hand hygiene, adequate testing to determine which virus is present, and other mitigation measures if the prevalence of COVID-19 is increasing in the community.”

Dr. Song reiterated those points, noting that clinicians need to make the most of the options they have. “Clinicians already have many great tools on hand. It is extremely important to get the flu vaccine now, especially for kids with underlying medical conditions. Diagnostic tests are available for both COVID-19 and flu. Antiviral treatment for flu is available. Judicious use of these tools will protect the health of providers, kids, and well-being at large.”

The authors noted several limitations for the study, including its retrospective design, that the data came from a single center, and that different platforms were used to detect the viruses.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

For children with COVID-19, rates of hospitalization, ICU admission, and ventilator use were similar to those of children with influenza, but rates differed in other respects, according to results of a study published online Sept. 11 in JAMA Network Open.

As winter approaches, distinguishing patients with COVID-19 from those with influenza will become a problem. To assist with that, Xiaoyan Song, PhD, director of the office of infection control and epidemiology at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., and colleagues investigated commonalities and differences between the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 and influenza in children.

“Distinguishing COVID-19 from flu and other respiratory viral infections remains a challenge to clinicians. Although our study showed that patients with COVID-19 were more likely than patients with flu to report fever, gastrointestinal, and other clinical symptoms at the time of diagnosis, the two groups do have many overlapping clinical symptoms,” Dr. Song said. “Until future data show us otherwise, clinicians need to prepare for managing coinfections of COVID-19 with flu and/or other respiratory viral infections in the upcoming flu season.”

The retrospective cohort study included 315 children diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between March 25 and May 15, 2020, and 1,402 children diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed seasonal influenza A or influenza B between Oct. 1, 2019, and June 6, 2020, at Children’s National Hospital. The investigation excluded asymptomatic patients who tested positive for COVID-19.

Patients with COVID-19 and patients with influenza were similar with respect to rates of hospitalization (17% vs. 21%; odds ratio, 0.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.6-1.1; P = .15), admission to the ICU (6% vs. 7%; OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.5-1.3; P = .42), and use of mechanical ventilation (3% vs. 2%; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 0.9-2.6; P =.17).

The difference in the duration of ventilation for the two groups was not statistically significant. None of the patients who had COVID-19 or influenza B died, but two patients with influenza A did.

No patients had coinfections, which the researchers attribute to the mid-March shutdown of many schools, which they believe limited the spread of seasonal influenza.

Patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 were older (median age, 9.7 years; range, 0.06-23.2 years) than those hospitalized with either type of influenza (median age, 4.2 years; range, 0.04-23.1). Patients older than 15 years made up 37% of patients with COVID-19 but only 6% of those with influenza.

Among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, 65% had at least one underlying medical condition, compared with 42% of those hospitalized for either type of influenza (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-4.7; P = .002).

The most common underlying condition was neurologic problems from global developmental delay or seizures, identified in 11 patients (20%) hospitalized with COVID-19 and in 24 patients (8%) hospitalized with influenza (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.2; P = .002). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to a history of asthma, cardiac disease, hematologic disease, and cancer.

For both groups, fever and cough were the most frequently reported symptoms at the time of diagnosis. However, more patients hospitalized with COVID-19 reported fever (76% vs. 55%; OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-5.1; P = 01), diarrhea or vomiting (26% vs. 12%; OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-5.0; P = .01), headache (11% vs. 3%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.3-11.5; P = .01), myalgia (22% vs. 7%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.8-8.5; P = .001), or chest pain (11% vs. 3%; OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.3-11.5; P = .01).

The researchers found no statistically significant differences between the two groups in rates of cough, congestion, sore throat, or shortness of breath.

Comparison of the symptom spectrum between COVID-19 and flu differed with respect to influenza type. More patients with COVID-19 reported fever, cough, diarrhea and vomiting, and myalgia than patients hospitalized with influenza A. But rates of fever, cough, diarrhea or vomiting, headache, or chest pain didn’t differ significantly in patients with COVID-19 and those with influenza B.

Larry K. Kociolek, MD, medical director of infection prevention and control at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, noted the lower age of patients with flu. “Differentiating the two infections, which is difficult if not impossible based on symptoms alone, may have prognostic implications, depending on the age of the child. Because this study was performed outside peak influenza season, when coinfections would be less likely to occur, we must be vigilant about the potential clinical implications of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 coinfection this fall and winter.”

Clinicians will still have to use a combination of symptoms, examinations, and testing to distinguish the two diseases, said Aimee Sznewajs, MD, medical director of the pediatric hospital medicine department at Children’s Minnesota, Minneapolis. “We will continue to test for influenza and COVID-19 prior to hospitalizations and make decisions about whether to hospitalize based on other clinical factors, such as dehydration, oxygen requirement, and vital sign changes.”

Dr. Sznewajs stressed the importance of maintaining public health strategies, including “ensuring all children get the flu vaccine, encouraging mask wearing and hand hygiene, adequate testing to determine which virus is present, and other mitigation measures if the prevalence of COVID-19 is increasing in the community.”

Dr. Song reiterated those points, noting that clinicians need to make the most of the options they have. “Clinicians already have many great tools on hand. It is extremely important to get the flu vaccine now, especially for kids with underlying medical conditions. Diagnostic tests are available for both COVID-19 and flu. Antiviral treatment for flu is available. Judicious use of these tools will protect the health of providers, kids, and well-being at large.”

The authors noted several limitations for the study, including its retrospective design, that the data came from a single center, and that different platforms were used to detect the viruses.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AI can pinpoint COVID-19 from chest x-rays

Conventional chest x-rays combined with artificial intelligence (AI) can identify lung damage from COVID-19 and differentiate coronavirus patients from other patients, improving triage efforts, new research suggests.

The AI tool – developed by Jason Fleischer, PhD, and graduate student Mohammad Tariqul Islam, both from Princeton (N.J.) University – can distinguish COVID-19 patients from those with pneumonia or normal lung tissue with an accuracy of more than 95%.

“We were able to separate the COVID-19 patients with very high fidelity,” Dr. Fleischer said in an interview. “If you give me an x-ray now, I can say with very high confidence whether a patient has COVID-19.”

The diagnostic tool pinpoints patterns on x-ray images that are too subtle for even trained experts to notice. The precision of CT scanning is similar to that of the AI tool, but CT costs much more and has other disadvantages, said Dr. Fleischer, who presented his findings at the virtual European Respiratory Society International Congress 2020.

“CT is more expensive and uses higher doses of radiation,” he said. “Another big thing is that not everyone has tomography facilities – including a lot of rural places and developing countries – so you need something that’s on the spot.”

With machine learning, Dr. Fleischer analyzed 2,300 x-ray images: 1,018 “normal” images from patients who had neither pneumonia nor COVID-19, 1,011 from patients with pneumonia, and 271 from patients with COVID-19.

The AI tool uses a neural network to refine the number and type of lung features being tracked. A UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) clustering algorithm then looks for similarities and differences in those images, he explained.

“We, as users, knew which type each x-ray was – normal, pneumonia positive, or COVID-19 positive – but the network did not,” he added.

Clinicians have observed two basic types of lung problems in COVID-19 patients: pneumonia that fills lung air sacs with fluid and dangerously low blood-oxygen levels despite nearly normal breathing patterns. Because treatment can vary according to type, it would be beneficial to quickly distinguish between them, Dr. Fleischer said.

The AI tool showed that there is a distinct difference in chest x-rays from pneumonia-positive patients and healthy people, he said. It also demonstrated two distinct clusters of COVID-19–positive chest x-rays: those that looked like pneumonia and those with a more normal presentation.

The fact that “the AI system recognizes something unique in chest x-rays from COVID-19–positive patients” indicates that the computer is able to identify visual markers for coronavirus, he explained. “We currently do not know what these markers are.”

Dr. Fleischer said his goal is not to replace physician decision-making, but to supplement it.

“I’m uncomfortable with having computers make the final decision,” he said. “They often have a narrow focus, whereas doctors have the big picture in mind.”

This AI tool is “very interesting,” especially in the context of expanding AI applications in various specialties, said Thierry Fumeaux, MD, from Nyon (Switzerland) Hospital. Some physicians currently disagree on whether a chest x-ray or CT scan is the better tool to help diagnose COVID-19.

“It seems better than the human eye and brain” to pinpoint COVID-19 lung damage, “so it’s very attractive as a technology,” Dr. Fumeaux said in an interview.

And AI can be used to supplement the efforts of busy and fatigued clinicians who might be stretched thin by large caseloads. “I cannot read 200 chest x-rays in a day, but a computer can do that in 2 minutes,” he said.

But Dr. Fumeaux offered a caveat: “Pattern recognition is promising, but at the moment I’m not aware of papers showing that, by using AI, you’re changing anything in the outcome of a patient.”

Ideally, Dr. Fleischer said he hopes that AI will soon be able to accurately indicate which treatments are most effective for individual COVID-19 patients. And the technology might eventually be used to help with treatment decisions for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he noted.

But he needs more data before results indicate whether a COVID-19 patient would benefit from ventilator support, for example, and the tool can be used more widely. To contribute data or collaborate with Dr. Fleischer’s efforts, contact him.

“Machine learning is all about data, so you can find these correlations,” he said. “It would be nice to be able to use it to reassure a worried patient that their prognosis is good; to say that most of the people with symptoms like yours will be just fine.”

Dr. Fleischer and Dr. Fumeaux have declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Conventional chest x-rays combined with artificial intelligence (AI) can identify lung damage from COVID-19 and differentiate coronavirus patients from other patients, improving triage efforts, new research suggests.

The AI tool – developed by Jason Fleischer, PhD, and graduate student Mohammad Tariqul Islam, both from Princeton (N.J.) University – can distinguish COVID-19 patients from those with pneumonia or normal lung tissue with an accuracy of more than 95%.

“We were able to separate the COVID-19 patients with very high fidelity,” Dr. Fleischer said in an interview. “If you give me an x-ray now, I can say with very high confidence whether a patient has COVID-19.”

The diagnostic tool pinpoints patterns on x-ray images that are too subtle for even trained experts to notice. The precision of CT scanning is similar to that of the AI tool, but CT costs much more and has other disadvantages, said Dr. Fleischer, who presented his findings at the virtual European Respiratory Society International Congress 2020.

“CT is more expensive and uses higher doses of radiation,” he said. “Another big thing is that not everyone has tomography facilities – including a lot of rural places and developing countries – so you need something that’s on the spot.”

With machine learning, Dr. Fleischer analyzed 2,300 x-ray images: 1,018 “normal” images from patients who had neither pneumonia nor COVID-19, 1,011 from patients with pneumonia, and 271 from patients with COVID-19.

The AI tool uses a neural network to refine the number and type of lung features being tracked. A UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) clustering algorithm then looks for similarities and differences in those images, he explained.

“We, as users, knew which type each x-ray was – normal, pneumonia positive, or COVID-19 positive – but the network did not,” he added.

Clinicians have observed two basic types of lung problems in COVID-19 patients: pneumonia that fills lung air sacs with fluid and dangerously low blood-oxygen levels despite nearly normal breathing patterns. Because treatment can vary according to type, it would be beneficial to quickly distinguish between them, Dr. Fleischer said.

The AI tool showed that there is a distinct difference in chest x-rays from pneumonia-positive patients and healthy people, he said. It also demonstrated two distinct clusters of COVID-19–positive chest x-rays: those that looked like pneumonia and those with a more normal presentation.

The fact that “the AI system recognizes something unique in chest x-rays from COVID-19–positive patients” indicates that the computer is able to identify visual markers for coronavirus, he explained. “We currently do not know what these markers are.”

Dr. Fleischer said his goal is not to replace physician decision-making, but to supplement it.

“I’m uncomfortable with having computers make the final decision,” he said. “They often have a narrow focus, whereas doctors have the big picture in mind.”

This AI tool is “very interesting,” especially in the context of expanding AI applications in various specialties, said Thierry Fumeaux, MD, from Nyon (Switzerland) Hospital. Some physicians currently disagree on whether a chest x-ray or CT scan is the better tool to help diagnose COVID-19.

“It seems better than the human eye and brain” to pinpoint COVID-19 lung damage, “so it’s very attractive as a technology,” Dr. Fumeaux said in an interview.

And AI can be used to supplement the efforts of busy and fatigued clinicians who might be stretched thin by large caseloads. “I cannot read 200 chest x-rays in a day, but a computer can do that in 2 minutes,” he said.

But Dr. Fumeaux offered a caveat: “Pattern recognition is promising, but at the moment I’m not aware of papers showing that, by using AI, you’re changing anything in the outcome of a patient.”

Ideally, Dr. Fleischer said he hopes that AI will soon be able to accurately indicate which treatments are most effective for individual COVID-19 patients. And the technology might eventually be used to help with treatment decisions for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he noted.

But he needs more data before results indicate whether a COVID-19 patient would benefit from ventilator support, for example, and the tool can be used more widely. To contribute data or collaborate with Dr. Fleischer’s efforts, contact him.

“Machine learning is all about data, so you can find these correlations,” he said. “It would be nice to be able to use it to reassure a worried patient that their prognosis is good; to say that most of the people with symptoms like yours will be just fine.”

Dr. Fleischer and Dr. Fumeaux have declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Conventional chest x-rays combined with artificial intelligence (AI) can identify lung damage from COVID-19 and differentiate coronavirus patients from other patients, improving triage efforts, new research suggests.

The AI tool – developed by Jason Fleischer, PhD, and graduate student Mohammad Tariqul Islam, both from Princeton (N.J.) University – can distinguish COVID-19 patients from those with pneumonia or normal lung tissue with an accuracy of more than 95%.

“We were able to separate the COVID-19 patients with very high fidelity,” Dr. Fleischer said in an interview. “If you give me an x-ray now, I can say with very high confidence whether a patient has COVID-19.”

The diagnostic tool pinpoints patterns on x-ray images that are too subtle for even trained experts to notice. The precision of CT scanning is similar to that of the AI tool, but CT costs much more and has other disadvantages, said Dr. Fleischer, who presented his findings at the virtual European Respiratory Society International Congress 2020.

“CT is more expensive and uses higher doses of radiation,” he said. “Another big thing is that not everyone has tomography facilities – including a lot of rural places and developing countries – so you need something that’s on the spot.”

With machine learning, Dr. Fleischer analyzed 2,300 x-ray images: 1,018 “normal” images from patients who had neither pneumonia nor COVID-19, 1,011 from patients with pneumonia, and 271 from patients with COVID-19.

The AI tool uses a neural network to refine the number and type of lung features being tracked. A UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) clustering algorithm then looks for similarities and differences in those images, he explained.

“We, as users, knew which type each x-ray was – normal, pneumonia positive, or COVID-19 positive – but the network did not,” he added.

Clinicians have observed two basic types of lung problems in COVID-19 patients: pneumonia that fills lung air sacs with fluid and dangerously low blood-oxygen levels despite nearly normal breathing patterns. Because treatment can vary according to type, it would be beneficial to quickly distinguish between them, Dr. Fleischer said.

The AI tool showed that there is a distinct difference in chest x-rays from pneumonia-positive patients and healthy people, he said. It also demonstrated two distinct clusters of COVID-19–positive chest x-rays: those that looked like pneumonia and those with a more normal presentation.

The fact that “the AI system recognizes something unique in chest x-rays from COVID-19–positive patients” indicates that the computer is able to identify visual markers for coronavirus, he explained. “We currently do not know what these markers are.”

Dr. Fleischer said his goal is not to replace physician decision-making, but to supplement it.

“I’m uncomfortable with having computers make the final decision,” he said. “They often have a narrow focus, whereas doctors have the big picture in mind.”

This AI tool is “very interesting,” especially in the context of expanding AI applications in various specialties, said Thierry Fumeaux, MD, from Nyon (Switzerland) Hospital. Some physicians currently disagree on whether a chest x-ray or CT scan is the better tool to help diagnose COVID-19.

“It seems better than the human eye and brain” to pinpoint COVID-19 lung damage, “so it’s very attractive as a technology,” Dr. Fumeaux said in an interview.

And AI can be used to supplement the efforts of busy and fatigued clinicians who might be stretched thin by large caseloads. “I cannot read 200 chest x-rays in a day, but a computer can do that in 2 minutes,” he said.

But Dr. Fumeaux offered a caveat: “Pattern recognition is promising, but at the moment I’m not aware of papers showing that, by using AI, you’re changing anything in the outcome of a patient.”

Ideally, Dr. Fleischer said he hopes that AI will soon be able to accurately indicate which treatments are most effective for individual COVID-19 patients. And the technology might eventually be used to help with treatment decisions for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he noted.

But he needs more data before results indicate whether a COVID-19 patient would benefit from ventilator support, for example, and the tool can be used more widely. To contribute data or collaborate with Dr. Fleischer’s efforts, contact him.

“Machine learning is all about data, so you can find these correlations,” he said. “It would be nice to be able to use it to reassure a worried patient that their prognosis is good; to say that most of the people with symptoms like yours will be just fine.”

Dr. Fleischer and Dr. Fumeaux have declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Social distancing impacts other infectious diseases

Diagnoses of 12 common pediatric infectious diseases in a large pediatric primary care network declined significantly in the weeks after COVID-19 social distancing (SD) was enacted in Massachusetts, compared with the same time period in 2019, an analysis of EHR data has shown.

While declines in infectious disease transmission with SD are not surprising, “these data demonstrate the extent to which transmission of common pediatric infections can be altered when close contact with other children is eliminated,” Jonathan Hatoun, MD, MPH of the Pediatric Physicians’ Organization at Children’s in Brookline, Mass., and coauthors wrote in Pediatrics . “Notably, three of the studied diseases, namely, influenza, croup, and bronchiolitis, essentially disappeared with [social distancing].”

The researchers analyzed the weekly incidence of each diagnosis for similar calendar periods in 2019 and 2020. A pre-SD period was defined as week 1-9, starting on Jan. 1, and a post-SD period was defined as week 13-18. (The several-week gap represented an implementation period as social distancing was enacted in the state earlier in 2020, from a declared statewide state of emergency through school closures and stay-at-home advisories.)

To isolate the effect of widespread SD, they performed a “difference-in-differences regression analysis, with diagnosis count as a function of calendar year, time period (pre-SD versus post-SD) and the interaction between the two.” The Massachusetts pediatric network provides care for approximately 375,000 children in 100 locations around the state.

In their research brief, Dr. Hatoun and coauthors presented weekly rates expressed as diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day. The rate of bronchiolitis, for instance, was 18 and 8 in the pre- and post-SD–equivalent weeks of 2019, respectively, and 20 and 0.6 in the pre- and post-SD weeks of 2020. Their analysis showed the rate in the 2020 post-SD period to be 10 diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day lower than they would have expected based on the 2019 trend.

Rates of pneumonia, acute otitis media, and streptococcal pharyngitis were similarly 14, 85, and 31 diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day lower, respectively. The prevalence of each of the other conditions analyzed – the common cold, croup, gastroenteritis, nonstreptococcal pharyngitis, sinusitis, skin and soft tissue infections, and urinary tract infection (UTI) – also was significantly lower in the 2020 post-SD period than would be expected based on 2019 data (P < .001 for all diagnoses).

Putting things in perspective

“This study puts numbers to the sense that we have all had in pediatrics – that social distancing appears to have had a dramatic impact on the transmission of common childhood infectious diseases, especially other respiratory viral pathogens,” Audrey R. John, MD, PhD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The authors acknowledged the possible role of families not seeking care, but said that a smaller decrease in diagnoses of UTI – generally not a contagious disease – “suggests that changes in care-seeking behavior had a relatively modest effect on the other observed declines.” (The rate of UTI for the pre- and post-SD periods was 3.3 and 3.7 per 100,000 patients per day in 2019, and 3.4 and 2.4 in 2020, for a difference in differences of –1.5).

In an accompanying editorial, David W. Kimberlin, MD and Erica C. Bjornstad, MD, PhD, MPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, called the report “provocative” and wrote that similar observations of infections dropping during periods of isolation – namely, dramatic declines in influenza and other respiratory viruses in Seattle after a record snowstorm in 2019 – combined with findings from other modeling studies “suggest that the decline [reported in Boston] is indeed real” (Pediatrics 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-019232).

However, “we also now know that immunization rates for American children have plummeted since the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [because of a] ... dramatic decrease in the use of health care during the first months of the pandemic,” they wrote. “Viewed through this lens,” the declines reported in Boston may reflect inflections going “undiagnosed and untreated.”

Ultimately, Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Bjornstad said, “the verdict remains out.”

Dr. John said that she and others are “concerned about children not seeking care in a timely manner, and [concerned] that reductions in reported infections might be due to a lack of recognition rather than a lack of transmission.”

In Philadelphia, however, declines in admissions for asthma exacerbations, “which are often caused by respiratory viral infections, suggests that this may not be the case,” said Dr. John, who was asked to comment on the study.

In addition, she said, the Massachusetts data showing that UTI diagnoses “are nearly as common this year as in 2019” are “reassuring.”

Are there lessons for the future?

Coauthor Louis Vernacchio, MD, MSc, chief medical officer of the Pediatric Physicians’ Organization at Children’s network, said in an interview that beyond the pandemic, it’s likely that “more careful attention to proven infection control practices in daycares and schools could reduce the burden of common infectious diseases in children.”

Dr. John similarly sees a long-term value of quantifying the impact of social distancing. “We’ve always known [for instance] that bronchiolitis is the result of viral infection.” Findings like the Massachusetts data “will help us advise families who might be trying to protect their premature infants (at risk for severe bronchiolitis) through social distancing.”

The analysis covered both in-person and telemedicine encounters occurring on weekdays.

The authors of the research brief indicated they have no relevant financial disclosures and there was no external funding. The authors of the commentary also reported they have no relevant financial disclosures, and Dr. John said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-006460.

Diagnoses of 12 common pediatric infectious diseases in a large pediatric primary care network declined significantly in the weeks after COVID-19 social distancing (SD) was enacted in Massachusetts, compared with the same time period in 2019, an analysis of EHR data has shown.

While declines in infectious disease transmission with SD are not surprising, “these data demonstrate the extent to which transmission of common pediatric infections can be altered when close contact with other children is eliminated,” Jonathan Hatoun, MD, MPH of the Pediatric Physicians’ Organization at Children’s in Brookline, Mass., and coauthors wrote in Pediatrics . “Notably, three of the studied diseases, namely, influenza, croup, and bronchiolitis, essentially disappeared with [social distancing].”

The researchers analyzed the weekly incidence of each diagnosis for similar calendar periods in 2019 and 2020. A pre-SD period was defined as week 1-9, starting on Jan. 1, and a post-SD period was defined as week 13-18. (The several-week gap represented an implementation period as social distancing was enacted in the state earlier in 2020, from a declared statewide state of emergency through school closures and stay-at-home advisories.)

To isolate the effect of widespread SD, they performed a “difference-in-differences regression analysis, with diagnosis count as a function of calendar year, time period (pre-SD versus post-SD) and the interaction between the two.” The Massachusetts pediatric network provides care for approximately 375,000 children in 100 locations around the state.

In their research brief, Dr. Hatoun and coauthors presented weekly rates expressed as diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day. The rate of bronchiolitis, for instance, was 18 and 8 in the pre- and post-SD–equivalent weeks of 2019, respectively, and 20 and 0.6 in the pre- and post-SD weeks of 2020. Their analysis showed the rate in the 2020 post-SD period to be 10 diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day lower than they would have expected based on the 2019 trend.

Rates of pneumonia, acute otitis media, and streptococcal pharyngitis were similarly 14, 85, and 31 diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day lower, respectively. The prevalence of each of the other conditions analyzed – the common cold, croup, gastroenteritis, nonstreptococcal pharyngitis, sinusitis, skin and soft tissue infections, and urinary tract infection (UTI) – also was significantly lower in the 2020 post-SD period than would be expected based on 2019 data (P < .001 for all diagnoses).

Putting things in perspective

“This study puts numbers to the sense that we have all had in pediatrics – that social distancing appears to have had a dramatic impact on the transmission of common childhood infectious diseases, especially other respiratory viral pathogens,” Audrey R. John, MD, PhD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The authors acknowledged the possible role of families not seeking care, but said that a smaller decrease in diagnoses of UTI – generally not a contagious disease – “suggests that changes in care-seeking behavior had a relatively modest effect on the other observed declines.” (The rate of UTI for the pre- and post-SD periods was 3.3 and 3.7 per 100,000 patients per day in 2019, and 3.4 and 2.4 in 2020, for a difference in differences of –1.5).

In an accompanying editorial, David W. Kimberlin, MD and Erica C. Bjornstad, MD, PhD, MPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, called the report “provocative” and wrote that similar observations of infections dropping during periods of isolation – namely, dramatic declines in influenza and other respiratory viruses in Seattle after a record snowstorm in 2019 – combined with findings from other modeling studies “suggest that the decline [reported in Boston] is indeed real” (Pediatrics 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-019232).

However, “we also now know that immunization rates for American children have plummeted since the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [because of a] ... dramatic decrease in the use of health care during the first months of the pandemic,” they wrote. “Viewed through this lens,” the declines reported in Boston may reflect inflections going “undiagnosed and untreated.”

Ultimately, Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Bjornstad said, “the verdict remains out.”

Dr. John said that she and others are “concerned about children not seeking care in a timely manner, and [concerned] that reductions in reported infections might be due to a lack of recognition rather than a lack of transmission.”

In Philadelphia, however, declines in admissions for asthma exacerbations, “which are often caused by respiratory viral infections, suggests that this may not be the case,” said Dr. John, who was asked to comment on the study.

In addition, she said, the Massachusetts data showing that UTI diagnoses “are nearly as common this year as in 2019” are “reassuring.”

Are there lessons for the future?

Coauthor Louis Vernacchio, MD, MSc, chief medical officer of the Pediatric Physicians’ Organization at Children’s network, said in an interview that beyond the pandemic, it’s likely that “more careful attention to proven infection control practices in daycares and schools could reduce the burden of common infectious diseases in children.”

Dr. John similarly sees a long-term value of quantifying the impact of social distancing. “We’ve always known [for instance] that bronchiolitis is the result of viral infection.” Findings like the Massachusetts data “will help us advise families who might be trying to protect their premature infants (at risk for severe bronchiolitis) through social distancing.”

The analysis covered both in-person and telemedicine encounters occurring on weekdays.

The authors of the research brief indicated they have no relevant financial disclosures and there was no external funding. The authors of the commentary also reported they have no relevant financial disclosures, and Dr. John said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-006460.

Diagnoses of 12 common pediatric infectious diseases in a large pediatric primary care network declined significantly in the weeks after COVID-19 social distancing (SD) was enacted in Massachusetts, compared with the same time period in 2019, an analysis of EHR data has shown.

While declines in infectious disease transmission with SD are not surprising, “these data demonstrate the extent to which transmission of common pediatric infections can be altered when close contact with other children is eliminated,” Jonathan Hatoun, MD, MPH of the Pediatric Physicians’ Organization at Children’s in Brookline, Mass., and coauthors wrote in Pediatrics . “Notably, three of the studied diseases, namely, influenza, croup, and bronchiolitis, essentially disappeared with [social distancing].”

The researchers analyzed the weekly incidence of each diagnosis for similar calendar periods in 2019 and 2020. A pre-SD period was defined as week 1-9, starting on Jan. 1, and a post-SD period was defined as week 13-18. (The several-week gap represented an implementation period as social distancing was enacted in the state earlier in 2020, from a declared statewide state of emergency through school closures and stay-at-home advisories.)

To isolate the effect of widespread SD, they performed a “difference-in-differences regression analysis, with diagnosis count as a function of calendar year, time period (pre-SD versus post-SD) and the interaction between the two.” The Massachusetts pediatric network provides care for approximately 375,000 children in 100 locations around the state.

In their research brief, Dr. Hatoun and coauthors presented weekly rates expressed as diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day. The rate of bronchiolitis, for instance, was 18 and 8 in the pre- and post-SD–equivalent weeks of 2019, respectively, and 20 and 0.6 in the pre- and post-SD weeks of 2020. Their analysis showed the rate in the 2020 post-SD period to be 10 diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day lower than they would have expected based on the 2019 trend.

Rates of pneumonia, acute otitis media, and streptococcal pharyngitis were similarly 14, 85, and 31 diagnoses per 100,000 patients per day lower, respectively. The prevalence of each of the other conditions analyzed – the common cold, croup, gastroenteritis, nonstreptococcal pharyngitis, sinusitis, skin and soft tissue infections, and urinary tract infection (UTI) – also was significantly lower in the 2020 post-SD period than would be expected based on 2019 data (P < .001 for all diagnoses).

Putting things in perspective

“This study puts numbers to the sense that we have all had in pediatrics – that social distancing appears to have had a dramatic impact on the transmission of common childhood infectious diseases, especially other respiratory viral pathogens,” Audrey R. John, MD, PhD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The authors acknowledged the possible role of families not seeking care, but said that a smaller decrease in diagnoses of UTI – generally not a contagious disease – “suggests that changes in care-seeking behavior had a relatively modest effect on the other observed declines.” (The rate of UTI for the pre- and post-SD periods was 3.3 and 3.7 per 100,000 patients per day in 2019, and 3.4 and 2.4 in 2020, for a difference in differences of –1.5).

In an accompanying editorial, David W. Kimberlin, MD and Erica C. Bjornstad, MD, PhD, MPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, called the report “provocative” and wrote that similar observations of infections dropping during periods of isolation – namely, dramatic declines in influenza and other respiratory viruses in Seattle after a record snowstorm in 2019 – combined with findings from other modeling studies “suggest that the decline [reported in Boston] is indeed real” (Pediatrics 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-019232).

However, “we also now know that immunization rates for American children have plummeted since the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [because of a] ... dramatic decrease in the use of health care during the first months of the pandemic,” they wrote. “Viewed through this lens,” the declines reported in Boston may reflect inflections going “undiagnosed and untreated.”

Ultimately, Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Bjornstad said, “the verdict remains out.”

Dr. John said that she and others are “concerned about children not seeking care in a timely manner, and [concerned] that reductions in reported infections might be due to a lack of recognition rather than a lack of transmission.”

In Philadelphia, however, declines in admissions for asthma exacerbations, “which are often caused by respiratory viral infections, suggests that this may not be the case,” said Dr. John, who was asked to comment on the study.

In addition, she said, the Massachusetts data showing that UTI diagnoses “are nearly as common this year as in 2019” are “reassuring.”

Are there lessons for the future?

Coauthor Louis Vernacchio, MD, MSc, chief medical officer of the Pediatric Physicians’ Organization at Children’s network, said in an interview that beyond the pandemic, it’s likely that “more careful attention to proven infection control practices in daycares and schools could reduce the burden of common infectious diseases in children.”

Dr. John similarly sees a long-term value of quantifying the impact of social distancing. “We’ve always known [for instance] that bronchiolitis is the result of viral infection.” Findings like the Massachusetts data “will help us advise families who might be trying to protect their premature infants (at risk for severe bronchiolitis) through social distancing.”

The analysis covered both in-person and telemedicine encounters occurring on weekdays.

The authors of the research brief indicated they have no relevant financial disclosures and there was no external funding. The authors of the commentary also reported they have no relevant financial disclosures, and Dr. John said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-006460.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Obesity-related hypoventilation increased morbidity risk after bariatric surgery

Patients with obesity-associated sleep hypoventilation had a heightened risk of postoperative morbidities after bariatric surgery, according to a retrospective study.

Reena Mehra, MD, director of sleep disorders research for the Sleep Disorders Center at the Cleveland Clinic, led the team and the findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Her research team examined the outcomes of 1,665 patients who underwent polysomnography prior to bariatric surgery performed at the Cleveland Clinic from 2011 to 2018.

More than two-thirds – 68.5% – had obesity-associated sleep hypoventilation as defined by body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2 and either polysomnography-based end-tidal CO2 ≥45 mm Hg or serum bicarbonate ≥27 mEq/L.

These patients represent “a subset, if you will, of obesity hypoventilation syndrome – a subset that we were able to capture from our sleep studies … [because] we do CO2 monitoring during sleep studies uniformly,” Dr. Mehra said in an interview after the meeting.

Pornprapa Chindamporn, MD, a former fellow at the center and first author on the abstract, presented the findings. Patients in the study had a mean age of 45.2 ± 12.0 years and a BMI of 48.7 ± 9.0. Approximately 20% were male and 63.6% were White.

Those with obesity-associated sleep hypoventilation were more likely to be male and have a higher BMI and higher hemoglobin A1c than those without the condition. They also had a significantly higher apnea-hypopnea index (17.0 vs. 13.8) in those without the condition, she reported.

A number of outcomes (ICU stay, intubation, tracheostomy, discharge disposition, and 30-day readmission) were compared individually and as a composite outcome between those with and without obesity-associated sleep hypoventilation. While some of these postoperative morbidities were more common in patients with the condition, the differences between those with and without OHS were not statistically significant for intubation (1.5% vs. 1.3%, P = .81) and 30-day readmission (13.8% vs. 11.3%, P = .16). However, the composite outcome was significantly higher: 18.9% vs. 14.3% (P = .021), including in multivariable analysis that considered age, gender, BMI, Apnea Hypopnea Index, and diabetes.

All-cause mortality was not significantly different between the groups, likely because of its low overall rate (hazard ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 0.56-3.42).

“In this largest sample to date of systematically phenotyped obesity-associated sleep hypoventilation in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, we identified increased postoperative morbidity,” said Dr. Chindamporn, now a pulmonologist and sleep specialist practicing in Bangkok.

Dr. Mehra said in the interview that patients considering bariatric surgery are typically assessed for obstructive sleep apnea, but “not so much obesity hypoventilation syndrome or obesity-associated sleep-related hypoventilation syndrome.” The findings, “support the notion that we should be closely examining sleep-related hypoventilation in these patients.”

At the Cleveland Clinic, “clinically, we make sure we’re identifying these individuals and communicating the findings to bariatric surgery colleagues and to anesthesia,” said Dr. Mehra, also professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

OHS is defined, according to the 2019 American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline on evaluation and management of OHS, by the combination of obesity, sleep-disordered breathing, and awake daytime hypercapnia, after excluding other causes for hypoventilation (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200[3]:e6-24).

A European Respiratory Society task force has proposed severity grading for OHS, with early stages defined by sleep-related hypoventilation and the highest grade of severity defined by morbidity-associated daytime hypercapnia (Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28:180097). However, Dr. Mehra said she is “not sure that we know enough [from long-term studies of OHS] to say definitively that there’s such an evolution.”

Certainly, she said, future research on OHS should consider its heterogeneity. It is possible that a subset of patients with OHS, “maybe these individuals with sleep-related hypoventilation,” are most likely to have adverse postsurgical outcomes.

Atul Malhotra, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, who was asked to comment on the study, said that OHS is understudied in general and particularly in the perioperative setting. “With the obesity pandemic, issues around OHS are likely to be [increasingly] important. And with increasing [use of] bariatric surgery, strategies to minimize risks are clearly needed,” he said, adding that the potential risks of nonbariatric surgery in patients with OHS require further study.

He noted that mortality rates in good hospitals “have become quite low for many elective surgeries, making it hard to show mortality benefit to most interventions.”

The ATS guideline on OHS states that it is the most severe form of obesity-induced respiratory compromise and leads to serious sequelae, including increased rates of mortality, chronic heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, and hospitalization caused by acute-on-chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure.

Dr. Chindamporn said in her presentation that she had no disclosures. Dr. Mehra’s research program is funded by the National Institute of Health, but she has also procured funding from the American College of Chest Physicians, American Heart Association, Clinical Translational Science Collaborative, and Central Society of Clinical Research. Dr. Malhotra disclosed that he is funded by the NIH and has received income from Merck and LIvanova related to medical education.

CORRECTION 9/15/2020: The original story misstated the presenter of the study. Dr. Chindamporn presented the findings.

Patients with obesity-associated sleep hypoventilation had a heightened risk of postoperative morbidities after bariatric surgery, according to a retrospective study.

Reena Mehra, MD, director of sleep disorders research for the Sleep Disorders Center at the Cleveland Clinic, led the team and the findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Her research team examined the outcomes of 1,665 patients who underwent polysomnography prior to bariatric surgery performed at the Cleveland Clinic from 2011 to 2018.

More than two-thirds – 68.5% – had obesity-associated sleep hypoventilation as defined by body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2 and either polysomnography-based end-tidal CO2 ≥45 mm Hg or serum bicarbonate ≥27 mEq/L.