User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

FDA blazes path for ‘real-world’ evidence as proof of efficacy

In 2016, results from the LEADER trial of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes helped jump-start awareness of the potential role of this new class of drugs, the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists, for reducing cardiovascular events. The randomized, placebo-controlled trial enrolled more than 9000 patients at more than 400 sites in over 30 countries, and took nearly 6 years from the start of patient enrollment to publication of the landmark results.

In December 2020, an independent team of researchers published results from a study with a design identical to LEADER, but used data that came not from a massive, global, years-long trial but from already-existing numbers culled from three large U.S. insurance claim databases. The result of this emulation using real-world data was virtually identical to what the actual trial showed, replicating both the direction and statistical significance of the original finding of the randomized, controlled trial (RCT).

What if research proved that this sort of RCT emulation could reliably be done on a regular basis? What might it mean for regulatory decisions on drugs and devices that historically have been based entirely on efficacy evidence from RCTs?

Making the most of a sea of observational data

Medicine in the United States has become increasingly awash in a sea of observational data collected from sources that include electronic health records, insurance claims, and increasingly, personal-health monitoring devices.

The Food and Drug Administration is now in the process of trying to figure out how it can legitimately harness this tsunami of real-world data to make efficacy decisions, essentially creating a new category of evidence to complement traditional data from randomized trials. It’s an opportunity that agency staff and their outside advisors have been keen to seize, especially given the soaring cost of prospective, randomized trials.

Recognition of this untapped resource in part led to a key initiative, among many others, included in the 21st Century Cures Act, passed in December 2016. Among the Act’s mandates was that, by the end of 2021, the FDA would issue guidance on when drug sponsors could use real-world evidence (RWE) to either help support a new indication for an already approved drug or help satisfy postapproval study requirements.

The initiative recognizes that this approach is not appropriate for initial drug approvals, which remain exclusively reliant on evidence from RCTs. Instead, it seems best suited to support expanding indications for already approved drugs.

Although FDA staff have made progress in identifying the challenges and broadening their understanding of how to best handle real-world data that come from observing patients in routine practice, agency leaders stress that this complex issue will likely not be fully resolved by their guidance to be published later this year. The FDA released a draft of the guidance in May 2019.

Can RWE be ‘credible and reliable?’

“Whether observational, nonrandomized data can become credible enough to use is what we’re talking about. These are possibilities that need to be explained and better understood,” said Robert Temple, MD, deputy director for clinical science of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“Since the 1970s, the FDA has recognized historical controls as legitimate, so it’s possible [for RWE] to be credible. The big test is when is it credible and reliable enough [to assess efficacy]?” wondered Dr. Temple during a 2-day workshop on the topic held mid-February and organized by Duke University’s Margolis Center for Health Policy.

“We’re approaching an inflection point regarding how observational studies are generated and used, but our evidentiary standards will not lower, and it will be a case-by-case decision” by the agency as they review future RWE submissions, said John Concato, MD, the FDA’s associate director for real-world evidence, during the workshop.

“We are working toward guidance development, but also looking down the road to what we need to do to enable this,” said Dr. Concato. “It’s a complicated issue. If it was easy, it would have already been fixed.” He added that the agency will likely release a “portfolio” of guidance for submitting real-world data and RWE. Real-world data are raw information that, when analyzed, become RWE.

In short, the FDA seems headed toward guidance that won’t spell out a pathway that guarantees success using RWE but will at least open the door to consideration of this unprecedented application.

Not like flipping a switch

The guidance will not activate acceptance of RWE all at once. “It’s not like a light switch,” cautioned Adam Kroetsch, MPP, research director for biomedical innovation and regulatory policy at Duke-Margolis in Washington, D.C. “It’s an evolutionary process,” and the upcoming guidance will provide “just a little more clarity” on what sorts of best practices using RWE the FDA will find persuasive. “It’s hard for the FDA to clearly say what it’s looking for until they see some good examples,” Dr. Kroetsch said in an interview.

What will change is that drug sponsors can submit using RWE, and the FDA “will have a more open-minded view,” predicted Sebastian Schneeweiss, MD, ScD, a workshop participant and chief of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “For the first time, a law required [the FDA] to take a serious look” at observational data for efficacy assessment.

“The FDA has had a bias against using RWE for evidence of efficacy but has long used it to understand drug safety. Now the FDA is trying to wrap its arms around how to best use RWE” for efficacy decisions, said Joseph S. Ross, MD, another workshop participant and professor of medicine and public health at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The agency’s cautious approach is reassuring, Dr. Ross noted in an interview. “There was worry that the 21st Century Cures Act would open the door to allowing real-world data to be used in ways that weren’t very reliable. Very quickly, the FDA started trying to figure out the best ways to use these data in reasonable ways.”

Duplicating RCTs with RWE

To help better understand the potential use of RWE, the FDA sponsored several demonstration projects. Researchers presented results from three of these projects during the workshop in February. All three examined whether RWE, plugged into the design of an actual RCT, can produce roughly similar results when similar patients are used.

A generally consistent finding from the three demonstration projects was that “when the data are fit for purpose” the emulated or duplicated analyses with RWE “can come to similar conclusions” as the actual RCTs, said Dr. Schneeweiss, who leads one of the demonstration projects, RCT DUPLICATE.

At the workshop he reported results from RWE duplications of 20 different RCTs using insurance claims data from U.S. patients. The findings came from 10 duplications already reported in Circulation in December 2020 (including a duplication of the LEADER trial), and an additional 10 as yet unpublished RCT duplications. In the next few months, the researchers intend to assess a final group of 10 more RCT duplications.

Workshop participants also presented results from two other FDA demonstration projects: the OPERAND program run by the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard; and the CERSI program based at Yale and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. Both are smaller in scale than RCT DUPLICATE, incorporate lab data in addition to claims data, and in some cases test how well RWE can emulate RCTs that are not yet completed.

Collectively, results from these demonstration projects suggest that RWE can successfully emulate the results of an RCT, said Dr. Ross, a coinvestigator on the CERSI study. But the CERSI findings also highlighted how an RCT can fall short of clinical relevance.

“One of our most important findings was that RCTs don’t always represent real-world practice,” he said. His group attempted to replicate the 5,000-patient GRADE trial of four different drug options added to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. One of the four options included insulin glargine (Lantus), and the attempt to emulate the study with RWE hit the bump that no relevant real-world patients in their US claims database actually received the formulation.

That means the GRADE trial “is almost meaningless. It doesn’t reflect real-world practice,” Dr. Ross noted.

Results from the three demonstration projects “highlight the gaps we still have,” summed up Dr. Kroetsch. “They show where we need better data” from observational sources that function as well as data from RCTs.

Still, the demonstration project results are “an important step forward in establishing the validity of real-world evidence,” commented David Kerr, MBChB, an endocrinologist and director of research and innovation at the Sansum Diabetes Research Institute in Santa Barbara, Calif.

‘Target trials’ tether RWE

The target trial approach to designing an observational study is a key tool for boosting reliability and applicability of the results. The idea is to create a well-designed trial that could be the basis for a conventional RCT, and then use observational data to flesh out the target trial instead of collecting data from prospectively enrolled patients.

Designing observational studies that emulate target trials allows causal inferences, said Miguel A. Hernán, MD, DrPH, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. Plugging real-world data into the framework of an appropriately designed target trial substantially cuts the risk of a biased analysis, he explained during the workshop.

However, the approach has limitations. The target trial must be a pragmatic trial, and the approach does not work for placebo-controlled trials, although it can accommodate a usual-care control arm. It also usually precludes patient blinding, testing treatments not used in routine practice, and close monitoring of patients in ways that are uncommon in usual care.

The target trial approach received broad endorsement during the workshop as the future for observational studies destined for efficacy consideration by the FDA.

“The idea of prespecifying a target trial is a really fantastic place to start,” commented Robert Ball, MD, deputy director of the FDA Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. “There is still a whole set of questions once the trial is prespecified, but prespecification would be a fantastic step forward,” he said during the workshop.

Participants also endorsed other important steps to boost the value of observational studies for regulatory reviews, including preregistering the study on a site such as clinicaltrials.gov; being fully transparent about the origins of observational data; using data that match the needs of the target trial; not reviewing the data in advance to avoid cherry picking and gaming the analysis; and reporting neutral or negative results when they occur, something often not currently done for observational analyses.

But although there was clear progress and much agreement among thought leaders at the workshop, FDA representatives stressed caution in moving forward.

“No easy answer”

“With more experience, we can learn what works and what doesn’t work in generating valid results from observational studies,” said Dr. Concato. “Although the observational results have upside potential, we need to learn more. There is no easy answer, no checklist for fit-for-use data, no off-the-shelf study design, and no ideal analytic method.”

Dr. Concato acknowledged that the FDA’s goal is clear given the 2016 legislation. “The FDA is embracing our obligations under the 21st Century Cures Act to evaluate use of real-world data and real-world evidence.”

He also suggested that researchers “shy away from a false dichotomy of RCTs or observational studies and instead think about how and when RCTs and observational studies can be designed and conducted to yield trustworthy results.” Dr. Concato’s solution: “a taxonomy of interventional or noninterventional studies.”

“The FDA is under enormous pressure to embrace real-world evidence, both because of the economics of running RCTs and because of the availability of new observational data from electronic health records, wearable devices, claims, etc.,” said Dr. Kerr, who did not participate in the workshop but coauthored an editorial that calls for using real-world data in regulatory decisions for drugs and devices for diabetes. These factors create an “irresistible force” spurring the FDA to consider observational, noninterventional data.

“I think the FDA really wants this to go forward,” Dr. Kerr added in an interview. “The FDA keeps telling us that clinical trials do not have enough women or patients from minority groups. Real-world data is a way to address that. This will not be the death of RCTs, but this work shines a light on the deficiencies of RCTs and how the deficiencies can be dealt with.”

Dr. Kroetsch has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Schneeweiss has reported being a consultant to and holding equity in Aetion and receiving research funding from the FDA. Dr. Ross has reported receiving research funding from the FDA, Johnson & Johnson, and Medtronic. Dr. Hernán has reported being a consultant for Cytel. Dr. Kerr has reported being a consultant for Ascensia, EOFlow, Lifecare, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diagnostics, and Voluntis. Dr. Temple, Dr. Concato, and Dr. Ball are FDA employees.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2016, results from the LEADER trial of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes helped jump-start awareness of the potential role of this new class of drugs, the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists, for reducing cardiovascular events. The randomized, placebo-controlled trial enrolled more than 9000 patients at more than 400 sites in over 30 countries, and took nearly 6 years from the start of patient enrollment to publication of the landmark results.

In December 2020, an independent team of researchers published results from a study with a design identical to LEADER, but used data that came not from a massive, global, years-long trial but from already-existing numbers culled from three large U.S. insurance claim databases. The result of this emulation using real-world data was virtually identical to what the actual trial showed, replicating both the direction and statistical significance of the original finding of the randomized, controlled trial (RCT).

What if research proved that this sort of RCT emulation could reliably be done on a regular basis? What might it mean for regulatory decisions on drugs and devices that historically have been based entirely on efficacy evidence from RCTs?

Making the most of a sea of observational data

Medicine in the United States has become increasingly awash in a sea of observational data collected from sources that include electronic health records, insurance claims, and increasingly, personal-health monitoring devices.

The Food and Drug Administration is now in the process of trying to figure out how it can legitimately harness this tsunami of real-world data to make efficacy decisions, essentially creating a new category of evidence to complement traditional data from randomized trials. It’s an opportunity that agency staff and their outside advisors have been keen to seize, especially given the soaring cost of prospective, randomized trials.

Recognition of this untapped resource in part led to a key initiative, among many others, included in the 21st Century Cures Act, passed in December 2016. Among the Act’s mandates was that, by the end of 2021, the FDA would issue guidance on when drug sponsors could use real-world evidence (RWE) to either help support a new indication for an already approved drug or help satisfy postapproval study requirements.

The initiative recognizes that this approach is not appropriate for initial drug approvals, which remain exclusively reliant on evidence from RCTs. Instead, it seems best suited to support expanding indications for already approved drugs.

Although FDA staff have made progress in identifying the challenges and broadening their understanding of how to best handle real-world data that come from observing patients in routine practice, agency leaders stress that this complex issue will likely not be fully resolved by their guidance to be published later this year. The FDA released a draft of the guidance in May 2019.

Can RWE be ‘credible and reliable?’

“Whether observational, nonrandomized data can become credible enough to use is what we’re talking about. These are possibilities that need to be explained and better understood,” said Robert Temple, MD, deputy director for clinical science of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“Since the 1970s, the FDA has recognized historical controls as legitimate, so it’s possible [for RWE] to be credible. The big test is when is it credible and reliable enough [to assess efficacy]?” wondered Dr. Temple during a 2-day workshop on the topic held mid-February and organized by Duke University’s Margolis Center for Health Policy.

“We’re approaching an inflection point regarding how observational studies are generated and used, but our evidentiary standards will not lower, and it will be a case-by-case decision” by the agency as they review future RWE submissions, said John Concato, MD, the FDA’s associate director for real-world evidence, during the workshop.

“We are working toward guidance development, but also looking down the road to what we need to do to enable this,” said Dr. Concato. “It’s a complicated issue. If it was easy, it would have already been fixed.” He added that the agency will likely release a “portfolio” of guidance for submitting real-world data and RWE. Real-world data are raw information that, when analyzed, become RWE.

In short, the FDA seems headed toward guidance that won’t spell out a pathway that guarantees success using RWE but will at least open the door to consideration of this unprecedented application.

Not like flipping a switch

The guidance will not activate acceptance of RWE all at once. “It’s not like a light switch,” cautioned Adam Kroetsch, MPP, research director for biomedical innovation and regulatory policy at Duke-Margolis in Washington, D.C. “It’s an evolutionary process,” and the upcoming guidance will provide “just a little more clarity” on what sorts of best practices using RWE the FDA will find persuasive. “It’s hard for the FDA to clearly say what it’s looking for until they see some good examples,” Dr. Kroetsch said in an interview.

What will change is that drug sponsors can submit using RWE, and the FDA “will have a more open-minded view,” predicted Sebastian Schneeweiss, MD, ScD, a workshop participant and chief of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “For the first time, a law required [the FDA] to take a serious look” at observational data for efficacy assessment.

“The FDA has had a bias against using RWE for evidence of efficacy but has long used it to understand drug safety. Now the FDA is trying to wrap its arms around how to best use RWE” for efficacy decisions, said Joseph S. Ross, MD, another workshop participant and professor of medicine and public health at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The agency’s cautious approach is reassuring, Dr. Ross noted in an interview. “There was worry that the 21st Century Cures Act would open the door to allowing real-world data to be used in ways that weren’t very reliable. Very quickly, the FDA started trying to figure out the best ways to use these data in reasonable ways.”

Duplicating RCTs with RWE

To help better understand the potential use of RWE, the FDA sponsored several demonstration projects. Researchers presented results from three of these projects during the workshop in February. All three examined whether RWE, plugged into the design of an actual RCT, can produce roughly similar results when similar patients are used.

A generally consistent finding from the three demonstration projects was that “when the data are fit for purpose” the emulated or duplicated analyses with RWE “can come to similar conclusions” as the actual RCTs, said Dr. Schneeweiss, who leads one of the demonstration projects, RCT DUPLICATE.

At the workshop he reported results from RWE duplications of 20 different RCTs using insurance claims data from U.S. patients. The findings came from 10 duplications already reported in Circulation in December 2020 (including a duplication of the LEADER trial), and an additional 10 as yet unpublished RCT duplications. In the next few months, the researchers intend to assess a final group of 10 more RCT duplications.

Workshop participants also presented results from two other FDA demonstration projects: the OPERAND program run by the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard; and the CERSI program based at Yale and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. Both are smaller in scale than RCT DUPLICATE, incorporate lab data in addition to claims data, and in some cases test how well RWE can emulate RCTs that are not yet completed.

Collectively, results from these demonstration projects suggest that RWE can successfully emulate the results of an RCT, said Dr. Ross, a coinvestigator on the CERSI study. But the CERSI findings also highlighted how an RCT can fall short of clinical relevance.

“One of our most important findings was that RCTs don’t always represent real-world practice,” he said. His group attempted to replicate the 5,000-patient GRADE trial of four different drug options added to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. One of the four options included insulin glargine (Lantus), and the attempt to emulate the study with RWE hit the bump that no relevant real-world patients in their US claims database actually received the formulation.

That means the GRADE trial “is almost meaningless. It doesn’t reflect real-world practice,” Dr. Ross noted.

Results from the three demonstration projects “highlight the gaps we still have,” summed up Dr. Kroetsch. “They show where we need better data” from observational sources that function as well as data from RCTs.

Still, the demonstration project results are “an important step forward in establishing the validity of real-world evidence,” commented David Kerr, MBChB, an endocrinologist and director of research and innovation at the Sansum Diabetes Research Institute in Santa Barbara, Calif.

‘Target trials’ tether RWE

The target trial approach to designing an observational study is a key tool for boosting reliability and applicability of the results. The idea is to create a well-designed trial that could be the basis for a conventional RCT, and then use observational data to flesh out the target trial instead of collecting data from prospectively enrolled patients.

Designing observational studies that emulate target trials allows causal inferences, said Miguel A. Hernán, MD, DrPH, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. Plugging real-world data into the framework of an appropriately designed target trial substantially cuts the risk of a biased analysis, he explained during the workshop.

However, the approach has limitations. The target trial must be a pragmatic trial, and the approach does not work for placebo-controlled trials, although it can accommodate a usual-care control arm. It also usually precludes patient blinding, testing treatments not used in routine practice, and close monitoring of patients in ways that are uncommon in usual care.

The target trial approach received broad endorsement during the workshop as the future for observational studies destined for efficacy consideration by the FDA.

“The idea of prespecifying a target trial is a really fantastic place to start,” commented Robert Ball, MD, deputy director of the FDA Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. “There is still a whole set of questions once the trial is prespecified, but prespecification would be a fantastic step forward,” he said during the workshop.

Participants also endorsed other important steps to boost the value of observational studies for regulatory reviews, including preregistering the study on a site such as clinicaltrials.gov; being fully transparent about the origins of observational data; using data that match the needs of the target trial; not reviewing the data in advance to avoid cherry picking and gaming the analysis; and reporting neutral or negative results when they occur, something often not currently done for observational analyses.

But although there was clear progress and much agreement among thought leaders at the workshop, FDA representatives stressed caution in moving forward.

“No easy answer”

“With more experience, we can learn what works and what doesn’t work in generating valid results from observational studies,” said Dr. Concato. “Although the observational results have upside potential, we need to learn more. There is no easy answer, no checklist for fit-for-use data, no off-the-shelf study design, and no ideal analytic method.”

Dr. Concato acknowledged that the FDA’s goal is clear given the 2016 legislation. “The FDA is embracing our obligations under the 21st Century Cures Act to evaluate use of real-world data and real-world evidence.”

He also suggested that researchers “shy away from a false dichotomy of RCTs or observational studies and instead think about how and when RCTs and observational studies can be designed and conducted to yield trustworthy results.” Dr. Concato’s solution: “a taxonomy of interventional or noninterventional studies.”

“The FDA is under enormous pressure to embrace real-world evidence, both because of the economics of running RCTs and because of the availability of new observational data from electronic health records, wearable devices, claims, etc.,” said Dr. Kerr, who did not participate in the workshop but coauthored an editorial that calls for using real-world data in regulatory decisions for drugs and devices for diabetes. These factors create an “irresistible force” spurring the FDA to consider observational, noninterventional data.

“I think the FDA really wants this to go forward,” Dr. Kerr added in an interview. “The FDA keeps telling us that clinical trials do not have enough women or patients from minority groups. Real-world data is a way to address that. This will not be the death of RCTs, but this work shines a light on the deficiencies of RCTs and how the deficiencies can be dealt with.”

Dr. Kroetsch has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Schneeweiss has reported being a consultant to and holding equity in Aetion and receiving research funding from the FDA. Dr. Ross has reported receiving research funding from the FDA, Johnson & Johnson, and Medtronic. Dr. Hernán has reported being a consultant for Cytel. Dr. Kerr has reported being a consultant for Ascensia, EOFlow, Lifecare, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diagnostics, and Voluntis. Dr. Temple, Dr. Concato, and Dr. Ball are FDA employees.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2016, results from the LEADER trial of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes helped jump-start awareness of the potential role of this new class of drugs, the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists, for reducing cardiovascular events. The randomized, placebo-controlled trial enrolled more than 9000 patients at more than 400 sites in over 30 countries, and took nearly 6 years from the start of patient enrollment to publication of the landmark results.

In December 2020, an independent team of researchers published results from a study with a design identical to LEADER, but used data that came not from a massive, global, years-long trial but from already-existing numbers culled from three large U.S. insurance claim databases. The result of this emulation using real-world data was virtually identical to what the actual trial showed, replicating both the direction and statistical significance of the original finding of the randomized, controlled trial (RCT).

What if research proved that this sort of RCT emulation could reliably be done on a regular basis? What might it mean for regulatory decisions on drugs and devices that historically have been based entirely on efficacy evidence from RCTs?

Making the most of a sea of observational data

Medicine in the United States has become increasingly awash in a sea of observational data collected from sources that include electronic health records, insurance claims, and increasingly, personal-health monitoring devices.

The Food and Drug Administration is now in the process of trying to figure out how it can legitimately harness this tsunami of real-world data to make efficacy decisions, essentially creating a new category of evidence to complement traditional data from randomized trials. It’s an opportunity that agency staff and their outside advisors have been keen to seize, especially given the soaring cost of prospective, randomized trials.

Recognition of this untapped resource in part led to a key initiative, among many others, included in the 21st Century Cures Act, passed in December 2016. Among the Act’s mandates was that, by the end of 2021, the FDA would issue guidance on when drug sponsors could use real-world evidence (RWE) to either help support a new indication for an already approved drug or help satisfy postapproval study requirements.

The initiative recognizes that this approach is not appropriate for initial drug approvals, which remain exclusively reliant on evidence from RCTs. Instead, it seems best suited to support expanding indications for already approved drugs.

Although FDA staff have made progress in identifying the challenges and broadening their understanding of how to best handle real-world data that come from observing patients in routine practice, agency leaders stress that this complex issue will likely not be fully resolved by their guidance to be published later this year. The FDA released a draft of the guidance in May 2019.

Can RWE be ‘credible and reliable?’

“Whether observational, nonrandomized data can become credible enough to use is what we’re talking about. These are possibilities that need to be explained and better understood,” said Robert Temple, MD, deputy director for clinical science of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“Since the 1970s, the FDA has recognized historical controls as legitimate, so it’s possible [for RWE] to be credible. The big test is when is it credible and reliable enough [to assess efficacy]?” wondered Dr. Temple during a 2-day workshop on the topic held mid-February and organized by Duke University’s Margolis Center for Health Policy.

“We’re approaching an inflection point regarding how observational studies are generated and used, but our evidentiary standards will not lower, and it will be a case-by-case decision” by the agency as they review future RWE submissions, said John Concato, MD, the FDA’s associate director for real-world evidence, during the workshop.

“We are working toward guidance development, but also looking down the road to what we need to do to enable this,” said Dr. Concato. “It’s a complicated issue. If it was easy, it would have already been fixed.” He added that the agency will likely release a “portfolio” of guidance for submitting real-world data and RWE. Real-world data are raw information that, when analyzed, become RWE.

In short, the FDA seems headed toward guidance that won’t spell out a pathway that guarantees success using RWE but will at least open the door to consideration of this unprecedented application.

Not like flipping a switch

The guidance will not activate acceptance of RWE all at once. “It’s not like a light switch,” cautioned Adam Kroetsch, MPP, research director for biomedical innovation and regulatory policy at Duke-Margolis in Washington, D.C. “It’s an evolutionary process,” and the upcoming guidance will provide “just a little more clarity” on what sorts of best practices using RWE the FDA will find persuasive. “It’s hard for the FDA to clearly say what it’s looking for until they see some good examples,” Dr. Kroetsch said in an interview.

What will change is that drug sponsors can submit using RWE, and the FDA “will have a more open-minded view,” predicted Sebastian Schneeweiss, MD, ScD, a workshop participant and chief of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “For the first time, a law required [the FDA] to take a serious look” at observational data for efficacy assessment.

“The FDA has had a bias against using RWE for evidence of efficacy but has long used it to understand drug safety. Now the FDA is trying to wrap its arms around how to best use RWE” for efficacy decisions, said Joseph S. Ross, MD, another workshop participant and professor of medicine and public health at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The agency’s cautious approach is reassuring, Dr. Ross noted in an interview. “There was worry that the 21st Century Cures Act would open the door to allowing real-world data to be used in ways that weren’t very reliable. Very quickly, the FDA started trying to figure out the best ways to use these data in reasonable ways.”

Duplicating RCTs with RWE

To help better understand the potential use of RWE, the FDA sponsored several demonstration projects. Researchers presented results from three of these projects during the workshop in February. All three examined whether RWE, plugged into the design of an actual RCT, can produce roughly similar results when similar patients are used.

A generally consistent finding from the three demonstration projects was that “when the data are fit for purpose” the emulated or duplicated analyses with RWE “can come to similar conclusions” as the actual RCTs, said Dr. Schneeweiss, who leads one of the demonstration projects, RCT DUPLICATE.

At the workshop he reported results from RWE duplications of 20 different RCTs using insurance claims data from U.S. patients. The findings came from 10 duplications already reported in Circulation in December 2020 (including a duplication of the LEADER trial), and an additional 10 as yet unpublished RCT duplications. In the next few months, the researchers intend to assess a final group of 10 more RCT duplications.

Workshop participants also presented results from two other FDA demonstration projects: the OPERAND program run by the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard; and the CERSI program based at Yale and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. Both are smaller in scale than RCT DUPLICATE, incorporate lab data in addition to claims data, and in some cases test how well RWE can emulate RCTs that are not yet completed.

Collectively, results from these demonstration projects suggest that RWE can successfully emulate the results of an RCT, said Dr. Ross, a coinvestigator on the CERSI study. But the CERSI findings also highlighted how an RCT can fall short of clinical relevance.

“One of our most important findings was that RCTs don’t always represent real-world practice,” he said. His group attempted to replicate the 5,000-patient GRADE trial of four different drug options added to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. One of the four options included insulin glargine (Lantus), and the attempt to emulate the study with RWE hit the bump that no relevant real-world patients in their US claims database actually received the formulation.

That means the GRADE trial “is almost meaningless. It doesn’t reflect real-world practice,” Dr. Ross noted.

Results from the three demonstration projects “highlight the gaps we still have,” summed up Dr. Kroetsch. “They show where we need better data” from observational sources that function as well as data from RCTs.

Still, the demonstration project results are “an important step forward in establishing the validity of real-world evidence,” commented David Kerr, MBChB, an endocrinologist and director of research and innovation at the Sansum Diabetes Research Institute in Santa Barbara, Calif.

‘Target trials’ tether RWE

The target trial approach to designing an observational study is a key tool for boosting reliability and applicability of the results. The idea is to create a well-designed trial that could be the basis for a conventional RCT, and then use observational data to flesh out the target trial instead of collecting data from prospectively enrolled patients.

Designing observational studies that emulate target trials allows causal inferences, said Miguel A. Hernán, MD, DrPH, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. Plugging real-world data into the framework of an appropriately designed target trial substantially cuts the risk of a biased analysis, he explained during the workshop.

However, the approach has limitations. The target trial must be a pragmatic trial, and the approach does not work for placebo-controlled trials, although it can accommodate a usual-care control arm. It also usually precludes patient blinding, testing treatments not used in routine practice, and close monitoring of patients in ways that are uncommon in usual care.

The target trial approach received broad endorsement during the workshop as the future for observational studies destined for efficacy consideration by the FDA.

“The idea of prespecifying a target trial is a really fantastic place to start,” commented Robert Ball, MD, deputy director of the FDA Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. “There is still a whole set of questions once the trial is prespecified, but prespecification would be a fantastic step forward,” he said during the workshop.

Participants also endorsed other important steps to boost the value of observational studies for regulatory reviews, including preregistering the study on a site such as clinicaltrials.gov; being fully transparent about the origins of observational data; using data that match the needs of the target trial; not reviewing the data in advance to avoid cherry picking and gaming the analysis; and reporting neutral or negative results when they occur, something often not currently done for observational analyses.

But although there was clear progress and much agreement among thought leaders at the workshop, FDA representatives stressed caution in moving forward.

“No easy answer”

“With more experience, we can learn what works and what doesn’t work in generating valid results from observational studies,” said Dr. Concato. “Although the observational results have upside potential, we need to learn more. There is no easy answer, no checklist for fit-for-use data, no off-the-shelf study design, and no ideal analytic method.”

Dr. Concato acknowledged that the FDA’s goal is clear given the 2016 legislation. “The FDA is embracing our obligations under the 21st Century Cures Act to evaluate use of real-world data and real-world evidence.”

He also suggested that researchers “shy away from a false dichotomy of RCTs or observational studies and instead think about how and when RCTs and observational studies can be designed and conducted to yield trustworthy results.” Dr. Concato’s solution: “a taxonomy of interventional or noninterventional studies.”

“The FDA is under enormous pressure to embrace real-world evidence, both because of the economics of running RCTs and because of the availability of new observational data from electronic health records, wearable devices, claims, etc.,” said Dr. Kerr, who did not participate in the workshop but coauthored an editorial that calls for using real-world data in regulatory decisions for drugs and devices for diabetes. These factors create an “irresistible force” spurring the FDA to consider observational, noninterventional data.

“I think the FDA really wants this to go forward,” Dr. Kerr added in an interview. “The FDA keeps telling us that clinical trials do not have enough women or patients from minority groups. Real-world data is a way to address that. This will not be the death of RCTs, but this work shines a light on the deficiencies of RCTs and how the deficiencies can be dealt with.”

Dr. Kroetsch has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Schneeweiss has reported being a consultant to and holding equity in Aetion and receiving research funding from the FDA. Dr. Ross has reported receiving research funding from the FDA, Johnson & Johnson, and Medtronic. Dr. Hernán has reported being a consultant for Cytel. Dr. Kerr has reported being a consultant for Ascensia, EOFlow, Lifecare, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diagnostics, and Voluntis. Dr. Temple, Dr. Concato, and Dr. Ball are FDA employees.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fresh look at ISCHEMIA bolsters conservative message in stable CAD

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

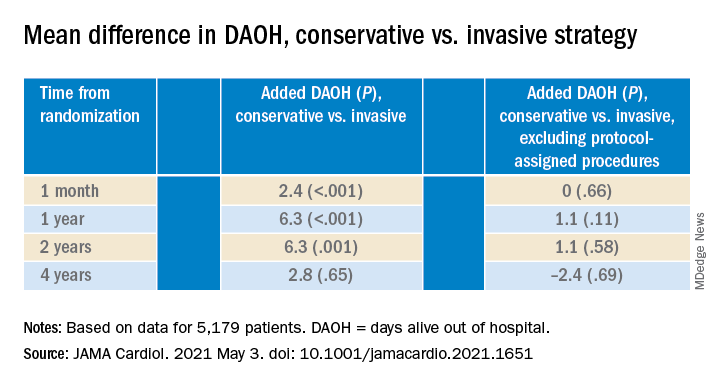

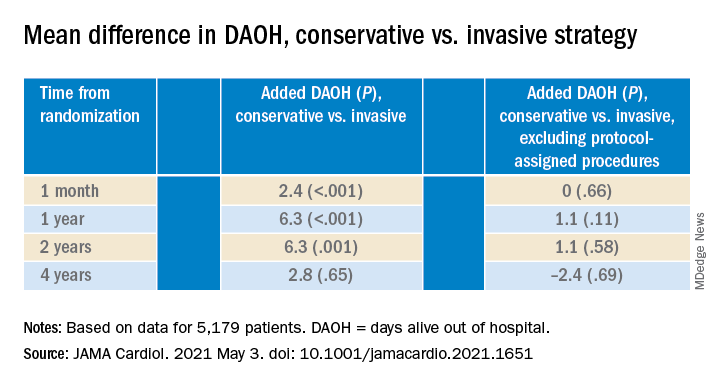

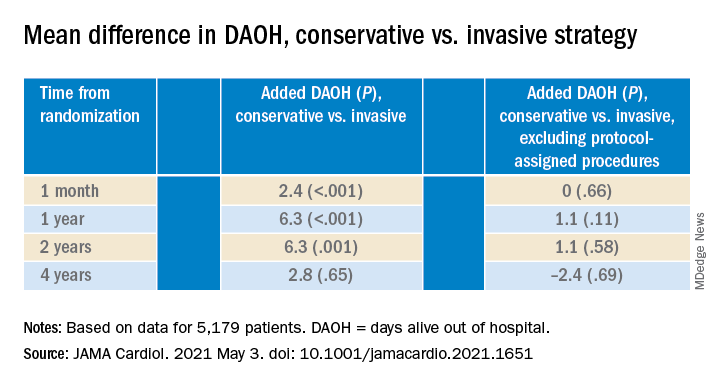

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.

But DAOH evened out for the two groups by the fourth year in the analysis of more than 5,000 patients.

Protocol-determined cath procedures accounted for 61% of hospitalizations in the invasively managed group. A secondary DAOH analysis that excluded such required hospital days, also prespecified, showed no meaningful difference between the two strategies over the 4 years, noted the report published online May 3 in JAMA Cardiology.

DOAH is ‘very, very important’

The DAOH metric has been a far less common consideration in clinical trials, compared with clinical events, yet in some ways it is as “hard” a metric as mortality, encompasses a broader range of outcomes, and may matter more to patients, it’s been argued.

“The thing patients most value is time at home. So they don’t want to be in the hospital, they don’t want to be away from friends, they want to do recreation, or they may want to work,” lead author Harvey D. White, DSc, Green Lane Cardiovascular Services, Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital, University of Auckland, told this news organization.

“When we need to talk to patients – and we do need to talk to patients – to have a days-out-of-hospital metric is very, very important,” he said. It is not only patient focused, it’s “meaningful in terms of the seriousness of events,” in that length of hospitalization tracks with clinical severity, observed Dr. White, who is slated to present the analysis May 17 during the virtual American College of Cardiology 2021 scientific sessions.

As previously reported, ISCHEMIA showed no significant effect on the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest by assignment group over a median 3.2 years. Angina and quality of life measures were improved for patients in the invasive arm.

With an invasive initial strategy, “What we know now is that you get nothing of an advantage in terms of the composite endpoint, and you’re going to spend 6 days more in the hospital in the first 2 years, for largely no benefit,” Dr. White said.

That outlook may apply out to 4 years, the analysis suggests, but could conceivably change if DAOH is reassessed later as the ISCHEMIA follow-up continues for what is now a planned total of 10 years.

Meanwhile, the current findings could enhance doctor-patient discussions about the trade-offs between the two strategies for individuals whose considerations will vary.

“This is a very helpful measure to understand the burden of an approach to the patient,” observed E. Magnus Ohman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not involved in the trial.

With DAOH as an endpoint, “you as a clinician get another aspect of understanding of a treatment’s impact on a multitude of endpoints.” Days out of hospital, he noted, encompasses the effects of clinical events that often go into composite clinical endpoints – not death, but including nonfatal MI, stroke, need for revascularization, and cardiovascular hospitalization.

To patients with stable CAD who ask whether the invasive approach has merits in their case, the DAOH finding “helps you to say, well, at the end of the day, you will probably be spending an equal amount of time in the hospital. Your price up front is a little bit higher, but over time, the group who gets conservative treatment will catch up.”

The DAOH outcome also avoids the limitations of an endpoint based on time to first event, “not the least of which,” said Dr. White, is that it counts only the first of what might be multiple events of varying clinical impact. Misleadingly, “you can have an event that’s a small troponin rise, but that becomes more important in a person than dying the next day.”

The DAOH analysis was based on 5,179 patients from 37 countries who averaged 64 years of age and of whom 23% were women. The endpoint considered only overnight stays in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes.

There were many more hospital or extended care facility stays overall in the invasive-management group, 4,002 versus 1,897 for those following the conservative strategy (P < .001), but the numbers flipped after excluding protocol-assigned procedures: 1,568 stays in the invasive group, compared with 1,897 (P = .001)

There were no associations between DAOH and Seattle Angina Questionnaire 7–Angina Frequency scores or DAOH interactions by age, sex, geographic region, or whether the patient had diabetes, prior MI, or heart failure, the report notes.

The primary ISCHEMIA analysis hinted at a possible long-term advantage for the invasive initial strategy in that event curves for the two arms crossed after 2-3 years, Dr. Ohman observed.

Based on that, for younger patients with stable CAD and ischemia at stress testing, “an investment of more hospital days early on might be worth it in the long run.” But ISCHEMIA, he said, “only suggests it, it doesn’t confirm it.”

The study was supported in part by grants from Arbor Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. Devices or medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Arbor, AstraZeneca, Esperion, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Phillips, Omron Healthcare, and Sunovion. Dr. White disclosed receiving grants paid to his institution and fees for serving on a steering committee from Sanofi-Aventis, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Omthera, American Regent, Eisai, DalCor, CSL Behring, Sanofi-Aventis Australia, and Esperion Therapeutics, and personal fees from Genentech and AstraZeneca. Dr. Ohman reported receiving grants from Abiomed and Cheisi USA, and consulting for Abiomed, Cara Therapeutics, Chiesi USA, Cytokinetics, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and XyloCor Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.

But DAOH evened out for the two groups by the fourth year in the analysis of more than 5,000 patients.

Protocol-determined cath procedures accounted for 61% of hospitalizations in the invasively managed group. A secondary DAOH analysis that excluded such required hospital days, also prespecified, showed no meaningful difference between the two strategies over the 4 years, noted the report published online May 3 in JAMA Cardiology.

DOAH is ‘very, very important’

The DAOH metric has been a far less common consideration in clinical trials, compared with clinical events, yet in some ways it is as “hard” a metric as mortality, encompasses a broader range of outcomes, and may matter more to patients, it’s been argued.

“The thing patients most value is time at home. So they don’t want to be in the hospital, they don’t want to be away from friends, they want to do recreation, or they may want to work,” lead author Harvey D. White, DSc, Green Lane Cardiovascular Services, Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital, University of Auckland, told this news organization.

“When we need to talk to patients – and we do need to talk to patients – to have a days-out-of-hospital metric is very, very important,” he said. It is not only patient focused, it’s “meaningful in terms of the seriousness of events,” in that length of hospitalization tracks with clinical severity, observed Dr. White, who is slated to present the analysis May 17 during the virtual American College of Cardiology 2021 scientific sessions.

As previously reported, ISCHEMIA showed no significant effect on the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest by assignment group over a median 3.2 years. Angina and quality of life measures were improved for patients in the invasive arm.

With an invasive initial strategy, “What we know now is that you get nothing of an advantage in terms of the composite endpoint, and you’re going to spend 6 days more in the hospital in the first 2 years, for largely no benefit,” Dr. White said.

That outlook may apply out to 4 years, the analysis suggests, but could conceivably change if DAOH is reassessed later as the ISCHEMIA follow-up continues for what is now a planned total of 10 years.

Meanwhile, the current findings could enhance doctor-patient discussions about the trade-offs between the two strategies for individuals whose considerations will vary.

“This is a very helpful measure to understand the burden of an approach to the patient,” observed E. Magnus Ohman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not involved in the trial.

With DAOH as an endpoint, “you as a clinician get another aspect of understanding of a treatment’s impact on a multitude of endpoints.” Days out of hospital, he noted, encompasses the effects of clinical events that often go into composite clinical endpoints – not death, but including nonfatal MI, stroke, need for revascularization, and cardiovascular hospitalization.

To patients with stable CAD who ask whether the invasive approach has merits in their case, the DAOH finding “helps you to say, well, at the end of the day, you will probably be spending an equal amount of time in the hospital. Your price up front is a little bit higher, but over time, the group who gets conservative treatment will catch up.”

The DAOH outcome also avoids the limitations of an endpoint based on time to first event, “not the least of which,” said Dr. White, is that it counts only the first of what might be multiple events of varying clinical impact. Misleadingly, “you can have an event that’s a small troponin rise, but that becomes more important in a person than dying the next day.”

The DAOH analysis was based on 5,179 patients from 37 countries who averaged 64 years of age and of whom 23% were women. The endpoint considered only overnight stays in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes.

There were many more hospital or extended care facility stays overall in the invasive-management group, 4,002 versus 1,897 for those following the conservative strategy (P < .001), but the numbers flipped after excluding protocol-assigned procedures: 1,568 stays in the invasive group, compared with 1,897 (P = .001)

There were no associations between DAOH and Seattle Angina Questionnaire 7–Angina Frequency scores or DAOH interactions by age, sex, geographic region, or whether the patient had diabetes, prior MI, or heart failure, the report notes.

The primary ISCHEMIA analysis hinted at a possible long-term advantage for the invasive initial strategy in that event curves for the two arms crossed after 2-3 years, Dr. Ohman observed.

Based on that, for younger patients with stable CAD and ischemia at stress testing, “an investment of more hospital days early on might be worth it in the long run.” But ISCHEMIA, he said, “only suggests it, it doesn’t confirm it.”

The study was supported in part by grants from Arbor Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. Devices or medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Arbor, AstraZeneca, Esperion, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Phillips, Omron Healthcare, and Sunovion. Dr. White disclosed receiving grants paid to his institution and fees for serving on a steering committee from Sanofi-Aventis, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Omthera, American Regent, Eisai, DalCor, CSL Behring, Sanofi-Aventis Australia, and Esperion Therapeutics, and personal fees from Genentech and AstraZeneca. Dr. Ohman reported receiving grants from Abiomed and Cheisi USA, and consulting for Abiomed, Cara Therapeutics, Chiesi USA, Cytokinetics, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and XyloCor Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.

But DAOH evened out for the two groups by the fourth year in the analysis of more than 5,000 patients.

Protocol-determined cath procedures accounted for 61% of hospitalizations in the invasively managed group. A secondary DAOH analysis that excluded such required hospital days, also prespecified, showed no meaningful difference between the two strategies over the 4 years, noted the report published online May 3 in JAMA Cardiology.

DOAH is ‘very, very important’

The DAOH metric has been a far less common consideration in clinical trials, compared with clinical events, yet in some ways it is as “hard” a metric as mortality, encompasses a broader range of outcomes, and may matter more to patients, it’s been argued.

“The thing patients most value is time at home. So they don’t want to be in the hospital, they don’t want to be away from friends, they want to do recreation, or they may want to work,” lead author Harvey D. White, DSc, Green Lane Cardiovascular Services, Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital, University of Auckland, told this news organization.

“When we need to talk to patients – and we do need to talk to patients – to have a days-out-of-hospital metric is very, very important,” he said. It is not only patient focused, it’s “meaningful in terms of the seriousness of events,” in that length of hospitalization tracks with clinical severity, observed Dr. White, who is slated to present the analysis May 17 during the virtual American College of Cardiology 2021 scientific sessions.

As previously reported, ISCHEMIA showed no significant effect on the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest by assignment group over a median 3.2 years. Angina and quality of life measures were improved for patients in the invasive arm.

With an invasive initial strategy, “What we know now is that you get nothing of an advantage in terms of the composite endpoint, and you’re going to spend 6 days more in the hospital in the first 2 years, for largely no benefit,” Dr. White said.

That outlook may apply out to 4 years, the analysis suggests, but could conceivably change if DAOH is reassessed later as the ISCHEMIA follow-up continues for what is now a planned total of 10 years.

Meanwhile, the current findings could enhance doctor-patient discussions about the trade-offs between the two strategies for individuals whose considerations will vary.

“This is a very helpful measure to understand the burden of an approach to the patient,” observed E. Magnus Ohman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not involved in the trial.

With DAOH as an endpoint, “you as a clinician get another aspect of understanding of a treatment’s impact on a multitude of endpoints.” Days out of hospital, he noted, encompasses the effects of clinical events that often go into composite clinical endpoints – not death, but including nonfatal MI, stroke, need for revascularization, and cardiovascular hospitalization.

To patients with stable CAD who ask whether the invasive approach has merits in their case, the DAOH finding “helps you to say, well, at the end of the day, you will probably be spending an equal amount of time in the hospital. Your price up front is a little bit higher, but over time, the group who gets conservative treatment will catch up.”

The DAOH outcome also avoids the limitations of an endpoint based on time to first event, “not the least of which,” said Dr. White, is that it counts only the first of what might be multiple events of varying clinical impact. Misleadingly, “you can have an event that’s a small troponin rise, but that becomes more important in a person than dying the next day.”

The DAOH analysis was based on 5,179 patients from 37 countries who averaged 64 years of age and of whom 23% were women. The endpoint considered only overnight stays in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes.

There were many more hospital or extended care facility stays overall in the invasive-management group, 4,002 versus 1,897 for those following the conservative strategy (P < .001), but the numbers flipped after excluding protocol-assigned procedures: 1,568 stays in the invasive group, compared with 1,897 (P = .001)

There were no associations between DAOH and Seattle Angina Questionnaire 7–Angina Frequency scores or DAOH interactions by age, sex, geographic region, or whether the patient had diabetes, prior MI, or heart failure, the report notes.

The primary ISCHEMIA analysis hinted at a possible long-term advantage for the invasive initial strategy in that event curves for the two arms crossed after 2-3 years, Dr. Ohman observed.

Based on that, for younger patients with stable CAD and ischemia at stress testing, “an investment of more hospital days early on might be worth it in the long run.” But ISCHEMIA, he said, “only suggests it, it doesn’t confirm it.”

The study was supported in part by grants from Arbor Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. Devices or medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Arbor, AstraZeneca, Esperion, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Phillips, Omron Healthcare, and Sunovion. Dr. White disclosed receiving grants paid to his institution and fees for serving on a steering committee from Sanofi-Aventis, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Omthera, American Regent, Eisai, DalCor, CSL Behring, Sanofi-Aventis Australia, and Esperion Therapeutics, and personal fees from Genentech and AstraZeneca. Dr. Ohman reported receiving grants from Abiomed and Cheisi USA, and consulting for Abiomed, Cara Therapeutics, Chiesi USA, Cytokinetics, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and XyloCor Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

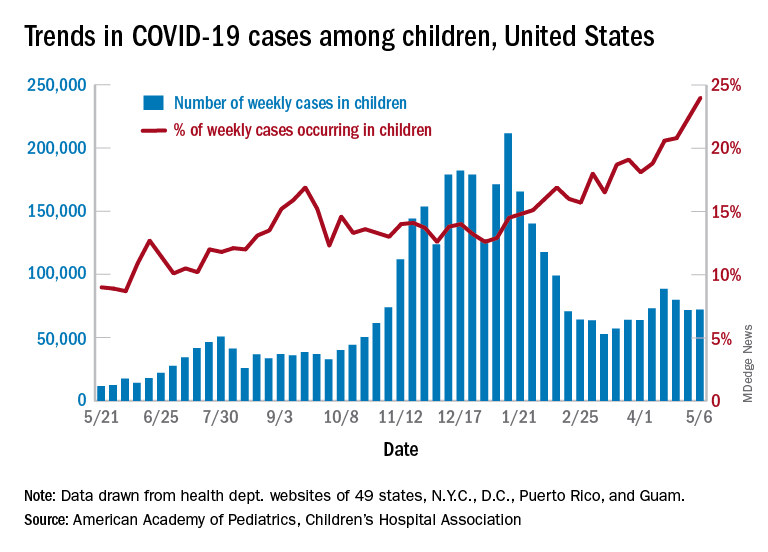

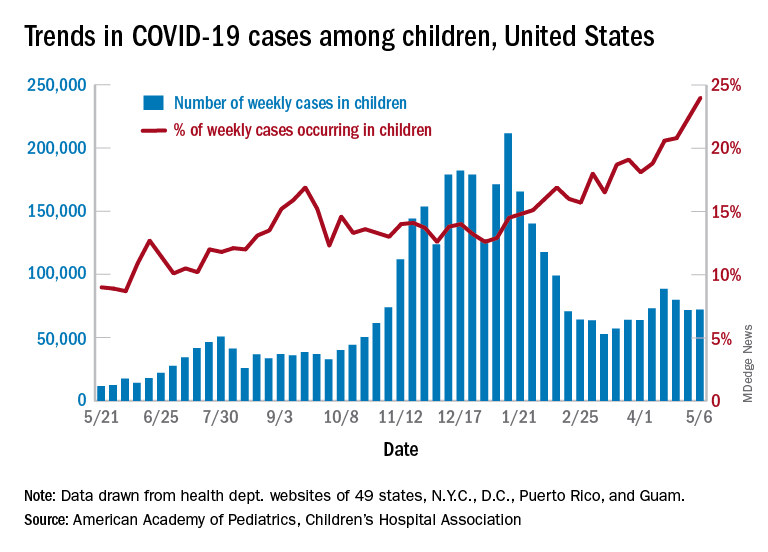

Small increase seen in new COVID-19 cases among children

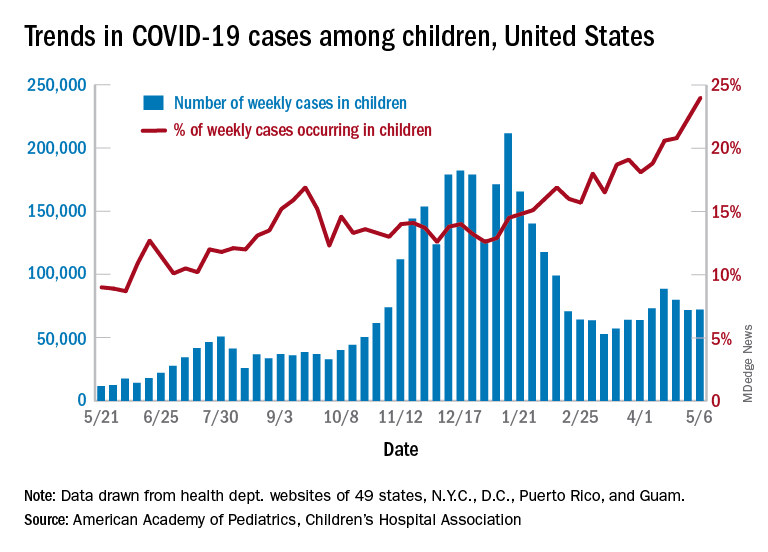

After 2 consecutive weeks of declines, the number of new COVID-19 cases in children rose slightly, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

higher than at any other time during the pandemic, the AAP and CHA data show.

It is worth noting, however, that Rhode Island experienced a 30% increase in the last week, adding about 4,900 cases because of data revision and a lag in reporting, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

All the new cases bring the total national count to just over 3.54 million in children, which represents 14.0% of all cases in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The cumulative case rate as of May 6 was 5,122 per 100,000 children, the two organizations said.

All the new cases that were added to Rhode Island’s total give it the highest cumulative rate in the country: 9,614 cases per 100,000 children. North Dakota is right behind with 9,526 per 100,000, followed by Tennessee (8,898), Connecticut (8,281), and South Carolina (8,274). Vermont has the highest proportion of cases in children at 22.4%, with Alaska next at 20.3% and South Carolina third at 18.7%, according to the AAP and CHA.

Hawaii just reported its first COVID-19–related death in a child, which drops the number of states with zero deaths in children from 10 to 9. Two other new deaths in children from April 30 to May 6 bring the total number to 306 in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are reporting the age distribution of deaths.

In a separate statement, AAP president Lee Savio Beers acknowledged the Food and Drug Administration’s authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children aged 12-15 years as “a critically important step in bringing lifesaving vaccines to children and adolescents. ... We look forward to the discussion by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the CDC, which will make recommendations about the use of this vaccine in adolescents.”

After 2 consecutive weeks of declines, the number of new COVID-19 cases in children rose slightly, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

higher than at any other time during the pandemic, the AAP and CHA data show.

It is worth noting, however, that Rhode Island experienced a 30% increase in the last week, adding about 4,900 cases because of data revision and a lag in reporting, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

All the new cases bring the total national count to just over 3.54 million in children, which represents 14.0% of all cases in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The cumulative case rate as of May 6 was 5,122 per 100,000 children, the two organizations said.

All the new cases that were added to Rhode Island’s total give it the highest cumulative rate in the country: 9,614 cases per 100,000 children. North Dakota is right behind with 9,526 per 100,000, followed by Tennessee (8,898), Connecticut (8,281), and South Carolina (8,274). Vermont has the highest proportion of cases in children at 22.4%, with Alaska next at 20.3% and South Carolina third at 18.7%, according to the AAP and CHA.

Hawaii just reported its first COVID-19–related death in a child, which drops the number of states with zero deaths in children from 10 to 9. Two other new deaths in children from April 30 to May 6 bring the total number to 306 in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are reporting the age distribution of deaths.

In a separate statement, AAP president Lee Savio Beers acknowledged the Food and Drug Administration’s authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children aged 12-15 years as “a critically important step in bringing lifesaving vaccines to children and adolescents. ... We look forward to the discussion by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the CDC, which will make recommendations about the use of this vaccine in adolescents.”

After 2 consecutive weeks of declines, the number of new COVID-19 cases in children rose slightly, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

higher than at any other time during the pandemic, the AAP and CHA data show.

It is worth noting, however, that Rhode Island experienced a 30% increase in the last week, adding about 4,900 cases because of data revision and a lag in reporting, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

All the new cases bring the total national count to just over 3.54 million in children, which represents 14.0% of all cases in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The cumulative case rate as of May 6 was 5,122 per 100,000 children, the two organizations said.

All the new cases that were added to Rhode Island’s total give it the highest cumulative rate in the country: 9,614 cases per 100,000 children. North Dakota is right behind with 9,526 per 100,000, followed by Tennessee (8,898), Connecticut (8,281), and South Carolina (8,274). Vermont has the highest proportion of cases in children at 22.4%, with Alaska next at 20.3% and South Carolina third at 18.7%, according to the AAP and CHA.

Hawaii just reported its first COVID-19–related death in a child, which drops the number of states with zero deaths in children from 10 to 9. Two other new deaths in children from April 30 to May 6 bring the total number to 306 in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are reporting the age distribution of deaths.

In a separate statement, AAP president Lee Savio Beers acknowledged the Food and Drug Administration’s authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children aged 12-15 years as “a critically important step in bringing lifesaving vaccines to children and adolescents. ... We look forward to the discussion by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the CDC, which will make recommendations about the use of this vaccine in adolescents.”

Dr. Fauci: Feds may ease indoor mask mandates soon

Federal guidance on indoor mask use may change soon, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said on May 9.

He was asked whether it’s time to start relaxing indoor mask requirements.

“I think so, and I think you’re going to probably be seeing that as we go along and as more people get vaccinated,” Dr. Fauci said on ABC News’s This Week.Nearly 150 million adults in the United States – or about 58% of the adult population – have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, according to the latest CDC tally. About 113 million adults, or 44%, are considered fully vaccinated.

“The CDC will be, you know, almost in real time … updating their recommendations and their guidelines,” Dr. Fauci said.

In April, the CDC relaxed its guidance for those who have been vaccinated against COVID-19. Those who have gotten a shot don’t need to wear a mask outdoors or in small indoor gatherings with other vaccinated people, but both vaccinated and unvaccinated people are still advised to wear masks in indoor public spaces.

“We do need to start being more liberal as we get more people vaccinated,” Dr. Fauci said. “As you get more people vaccinated, the number of cases per day will absolutely go down.”

The United States is averaging about 43,000 cases per day, he said, adding that the cases need to be “much, much lower.” When the case numbers drop and vaccination numbers increase, the risk of infection will fall dramatically indoors and outdoors, he said.

Even after the pandemic, though, wearing masks could become a seasonal habit, Dr. Fauci said May 9 on NBC News’s Meet the Press.“I think people have gotten used to the fact that wearing masks, clearly if you look at the data, it diminishes respiratory diseases. We’ve had practically a nonexistent flu season this year,” he said.

“So it is conceivable that as we go on, a year or 2 or more from now, that during certain seasonal periods when you have respiratory-borne viruses like the flu, people might actually elect to wear masks to diminish the likelihood that you’ll spread these respiratory-borne diseases,” he said.

Dr. Fauci was asked about indoor mask guidelines on May 9 after former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said face mask requirements should be relaxed.

“Certainly outdoors, we shouldn’t be putting limits on gatherings anymore,” Dr. Gottlieb said on CBS News’s Face the Nation.“The states where prevalence is low, vaccination rates are high, we have good testing in place, and we’re identifying infections, I think we could start lifting these restrictions indoors as well, on a broad basis,” he said.

Lifting pandemic-related restrictions in areas where they’re no longer necessary could also encourage people to implement them again if cases increase during future surges, such as this fall or winter, Dr. Gottlieb said.

At the same time, Americans should continue to follow CDC guidance and wait for new guidelines before changing their indoor mask use, Jeffrey Zients, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, said on CNN’s State of the Union on May 9.

“We all want to get back to a normal lifestyle,” he said. “I think we’re on the path to do that, but stay disciplined, and let’s take advantage of the new privilege of being vaccinated and not wearing masks outdoors, for example, unless you’re in a crowded place.”

Mr. Zients pointed to President Joe Biden’s goal for 70% of adults to receive at least one vaccine dose by July 4.

“As we all move toward that 70% goal, there will be more and more advantages to being vaccinated,” he said. “And if you’re not vaccinated, you’re not protected.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Federal guidance on indoor mask use may change soon, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said on May 9.

He was asked whether it’s time to start relaxing indoor mask requirements.

“I think so, and I think you’re going to probably be seeing that as we go along and as more people get vaccinated,” Dr. Fauci said on ABC News’s This Week.Nearly 150 million adults in the United States – or about 58% of the adult population – have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, according to the latest CDC tally. About 113 million adults, or 44%, are considered fully vaccinated.

“The CDC will be, you know, almost in real time … updating their recommendations and their guidelines,” Dr. Fauci said.

In April, the CDC relaxed its guidance for those who have been vaccinated against COVID-19. Those who have gotten a shot don’t need to wear a mask outdoors or in small indoor gatherings with other vaccinated people, but both vaccinated and unvaccinated people are still advised to wear masks in indoor public spaces.

“We do need to start being more liberal as we get more people vaccinated,” Dr. Fauci said. “As you get more people vaccinated, the number of cases per day will absolutely go down.”

The United States is averaging about 43,000 cases per day, he said, adding that the cases need to be “much, much lower.” When the case numbers drop and vaccination numbers increase, the risk of infection will fall dramatically indoors and outdoors, he said.

Even after the pandemic, though, wearing masks could become a seasonal habit, Dr. Fauci said May 9 on NBC News’s Meet the Press.“I think people have gotten used to the fact that wearing masks, clearly if you look at the data, it diminishes respiratory diseases. We’ve had practically a nonexistent flu season this year,” he said.

“So it is conceivable that as we go on, a year or 2 or more from now, that during certain seasonal periods when you have respiratory-borne viruses like the flu, people might actually elect to wear masks to diminish the likelihood that you’ll spread these respiratory-borne diseases,” he said.

Dr. Fauci was asked about indoor mask guidelines on May 9 after former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said face mask requirements should be relaxed.

“Certainly outdoors, we shouldn’t be putting limits on gatherings anymore,” Dr. Gottlieb said on CBS News’s Face the Nation.“The states where prevalence is low, vaccination rates are high, we have good testing in place, and we’re identifying infections, I think we could start lifting these restrictions indoors as well, on a broad basis,” he said.

Lifting pandemic-related restrictions in areas where they’re no longer necessary could also encourage people to implement them again if cases increase during future surges, such as this fall or winter, Dr. Gottlieb said.

At the same time, Americans should continue to follow CDC guidance and wait for new guidelines before changing their indoor mask use, Jeffrey Zients, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, said on CNN’s State of the Union on May 9.

“We all want to get back to a normal lifestyle,” he said. “I think we’re on the path to do that, but stay disciplined, and let’s take advantage of the new privilege of being vaccinated and not wearing masks outdoors, for example, unless you’re in a crowded place.”

Mr. Zients pointed to President Joe Biden’s goal for 70% of adults to receive at least one vaccine dose by July 4.

“As we all move toward that 70% goal, there will be more and more advantages to being vaccinated,” he said. “And if you’re not vaccinated, you’re not protected.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Federal guidance on indoor mask use may change soon, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said on May 9.

He was asked whether it’s time to start relaxing indoor mask requirements.

“I think so, and I think you’re going to probably be seeing that as we go along and as more people get vaccinated,” Dr. Fauci said on ABC News’s This Week.Nearly 150 million adults in the United States – or about 58% of the adult population – have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, according to the latest CDC tally. About 113 million adults, or 44%, are considered fully vaccinated.

“The CDC will be, you know, almost in real time … updating their recommendations and their guidelines,” Dr. Fauci said.

In April, the CDC relaxed its guidance for those who have been vaccinated against COVID-19. Those who have gotten a shot don’t need to wear a mask outdoors or in small indoor gatherings with other vaccinated people, but both vaccinated and unvaccinated people are still advised to wear masks in indoor public spaces.

“We do need to start being more liberal as we get more people vaccinated,” Dr. Fauci said. “As you get more people vaccinated, the number of cases per day will absolutely go down.”

The United States is averaging about 43,000 cases per day, he said, adding that the cases need to be “much, much lower.” When the case numbers drop and vaccination numbers increase, the risk of infection will fall dramatically indoors and outdoors, he said.

Even after the pandemic, though, wearing masks could become a seasonal habit, Dr. Fauci said May 9 on NBC News’s Meet the Press.“I think people have gotten used to the fact that wearing masks, clearly if you look at the data, it diminishes respiratory diseases. We’ve had practically a nonexistent flu season this year,” he said.