User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Could the Surgisphere Lancet and NEJM retractions debacle happen again?

In May 2020, two major scientific journals published and subsequently retracted studies that relied on data provided by the now-disgraced data analytics company Surgisphere.

One of the studies, published in The Lancet, reported an association between the antimalarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine and increased in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19. The second study, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, described an association between underlying cardiovascular disease, but not related drug therapy, with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The retractions in June 2020 followed an open letter to each publication penned by scientists, ethicists, and clinicians who flagged serious methodological and ethical anomalies in the data used in the studies.

On the 1-year anniversary, researchers and journal editors spoke about what was learned to reduce the risk of something like this happening again.

“The Surgisphere incident served as a wake-up call for everyone involved with scientific research to make sure that data have integrity and are robust,” Sunil Rao, MD, professor of medicine, Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., and editor-in-chief of Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, said in an interview.

“I’m sure this isn’t going to be the last incident of this nature, and we have to be vigilant about new datasets or datasets that we haven’t heard of as having a track record of publication,” Dr. Rao said.

Spotlight on authors

The editors of the Lancet Group responded to the “wake-up call” with a statement, Learning From a Retraction, which announced changes to reduce the risks of research and publication misconduct.

The changes affect multiple phases of the publication process. For example, the declaration form that authors must sign “will require that more than one author has directly accessed and verified the data reported in the manuscript.” Additionally, when a research article is the result of an academic and commercial partnership – as was the case in the two retracted studies – “one of the authors named as having accessed and verified data must be from the academic team.”

This was particularly important because it appears that the academic coauthors of the retracted studies did not have access to the data provided by Surgisphere, a private commercial entity.

Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, William Harvey Distinguished Chair in Advanced Cardiovascular Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was the lead author of both studies, declined to be interviewed for this article. In a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine editors requesting that the article be retracted, he wrote: “Because all the authors were not granted access to the raw data and the raw data could not be made available to a third-party auditor, we are unable to validate the primary data sources underlying our article.”

In a similar communication with The Lancet, Dr. Mehra wrote even more pointedly that, in light of the refusal of Surgisphere to make the data available to the third-party auditor, “we can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources.”

“It is very disturbing that the authors were willing to put their names on a paper without ever seeing and verifying the data,” Mario Malički, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at METRICS at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “Saying that they could ‘no longer vouch’ suggests that at one point they could vouch for it. Most likely they took its existence and veracity entirely on trust.”

Dr. Malički pointed out that one of the four criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for being an author on a study is the “agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.”

The new policies put forth by The Lancet are “encouraging,” but perhaps do not go far enough. “Every author, not only one or two authors, should personally take responsibility for the integrity of data,” he stated.

Many journals “adhere to ICMJE rules in principle and have checkboxes for authors to confirm that they guarantee the veracity of the data.” However, they “do not have the resources to verify the authors’ statements.”

Ideally, “it is the institutions where the researchers work that should guarantee the veracity of the raw data – but I do not know any university or institute that does this,” he said.

No ‘good-housekeeping’ seal

For articles based on large, real-world datasets, the Lancet Group will now require that editors ensure that at least one peer reviewer is “knowledgeable about the details of the dataset being reported and can understand its strengths and limitations in relation to the question being addressed.”

For studies that use “very large datasets,” the editors are now required to ensure that, in addition to a statistical peer review, a review from an “expert in data science” is obtained. Reviewers will also be explicitly asked if they have “concerns about research integrity or publication ethics regarding the manuscript they are reviewing.”

Although these changes are encouraging, Harlan Krumholz, MD, professor of medicine (cardiology), Yale University, New Haven, Conn., is not convinced that they are realistic.

Dr. Krumholz, who is also the founder and director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcome Research and Evaluation, said in an interview that “large, real-world datasets” are of two varieties. Datasets drawn from publicly available sources, such as Medicare or Medicaid health records, are utterly transparent.

By contrast, Surgisphere was a privately owned database, and “it is not unusual for privately owned databases to have proprietary data from multiple sources that the company may choose to keep confidential,” Dr. Krumholz said.

He noted that several large datasets are widely used for research purposes, such as IBM, Optum, and Komodo – a data analytics company that recently entered into partnership with a fourth company, PicnicHealth.

These companies receive deidentified electronic health records from health systems and insurers nationwide. Komodo boasts “real-time and longitudinal data on more than 325 million patients, representing more than 65 billion clinical encounters with 15 million new encounters added daily.”

“One has to raise an eyebrow – how were these data acquired? And, given that the U.S. has a population of around 328 million people, is it really plausible that a single company has health records of almost the entire U.S. population?” Dr. Krumholz commented. (A spokesperson for Komodo said in an interview that the company has records on 325 million U.S. patients.)

This is “an issue across the board with ‘real-world evidence,’ which is that it’s like the ‘Wild West’ – the transparencies of private databases are less than optimal and there are no common standards to help us move forward,” Dr. Krumholz said, noting that there is “no external authority overseeing, validating, or auditing these databases. In the end, we are trusting the companies.”

Although the Food and Drug Administration has laid out a framework for how real-world data and real-world evidence can be used to advance scientific research, the FDA does not oversee the databases.

“Thus, there is no ‘good housekeeping seal’ that a peer reviewer or author would be in a position to evaluate,” Dr. Krumholz said. “No journal can do an audit of these types of private databases, so ultimately, it boils down to trust.”

Nevertheless, there were red flags with Surgisphere, Dr. Rao pointed out. Unlike more established and widely used databases, the Surgisphere database had been catapulted from relative obscurity onto center stage, which should have given researchers pause.

AI-assisted peer review

A series of investigative reports by The Guardian raised questions about Sapan Desai, the CEO of Surgisphere, including the fact that hospitals purporting to have contributed data to Surgisphere had never heard of the company.

However, peer reviewers are not expected to be investigative reporters, explained Dr. Malički.

“In an ideal world, editors and peer reviewers would have a chance to look at raw data or would have a certificate from the academic institution the authors are affiliated with that the data have been inspected by the institution, but in the real world, of course, this does not happen,” he said.

Artificial intelligence software is being developed and deployed to assist in the peer review process, Dr. Malički noted. In July 2020, Frontiers Science News debuted its Artificial Intelligence Review Assistant to help editors, reviewers, and authors evaluate the quality of a manuscript. The program can make up to 20 recommendations, including “the assessment of language quality, the detection of plagiarism, and identification of potential conflicts of interest.” The program is now in use in all 103 journals published by Frontiers. Preliminary software is also available to detect statistical errors.

Another system under development is FAIRware, an initiative of the Research on Research Institute in partnership with the Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research. The partnership’s goal is to “develop an automated online tool (or suite of tools) to help researchers ensure that the datasets they produce are ‘FAIR’ at the point of creation,” said Dr. Malički, referring to the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) guiding principles for data management. The principles aim to increase the ability of machines to automatically find and use the data, as well as to support its reuse by individuals.

He added that these advanced tools cannot replace human reviewers, who will “likely always be a necessary quality check in the process.”

Greater transparency needed

Another limitation of peer review is the reviewers themselves, according to Dr. Malički. “It’s a step in the right direction that The Lancet is now requesting a peer reviewer with expertise in big datasets, but it does not go far enough to increase accountability of peer reviewers,” he said.

Dr. Malički is the co–editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review , which has “an open and transparent review process – meaning that we reveal the names of the reviewers to the public and we publish the full review report alongside the paper.” The publication also allows the authors to make public the original version they sent.

Dr. Malički cited several advantages to transparent peer review, particularly the increased accountability that results from placing potential conflicts of interest under the microscope.

As for the concern that identifying the reviewers might soften the review process, “there is little evidence to substantiate that concern,” he added.

Dr. Malički emphasized that making reviews public “is not a problem – people voice strong opinions at conferences and elsewhere. The question remains, who gets to decide if the criticism has been adequately addressed, so that the findings of the study still stand?”

He acknowledged that, “as in politics and on many social platforms, rage, hatred, and personal attacks divert the discussion from the topic at hand, which is why a good moderator is needed.”

A journal editor or a moderator at a scientific conference may be tasked with “stopping all talk not directly related to the topic.”

Widening the circle of scrutiny

Dr. Malički added: “A published paper should not be considered the ‘final word,’ even if it has gone through peer review and is published in a reputable journal. The peer-review process means that a limited number of people have seen the study.”

Once the study is published, “the whole world gets to see it and criticize it, and that widens the circle of scrutiny.”

One classic way to raise concerns about a study post publication is to write a letter to the journal editor. But there is no guarantee that the letter will be published or the authors notified of the feedback.

Dr. Malički encourages readers to use PubPeer, an online forum in which members of the public can post comments on scientific studies and articles.

Once a comment is posted, the authors are alerted. “There is no ‘police department’ that forces authors to acknowledge comments or forces journal editors to take action, but at least PubPeer guarantees that readers’ messages will reach the authors and – depending on how many people raise similar issues – the comments can lead to errata or even full retractions,” he said.

PubPeer was key in pointing out errors in a suspect study from France (which did not involve Surgisphere) that supported the use of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19.

A message to policy makers

High stakes are involved in ensuring the integrity of scientific publications: The French government revoked a decree that allowed hospitals to prescribe hydroxychloroquine for certain COVID-19 patients.

After the Surgisphere Lancet article, the World Health Organization temporarily halted enrollment in the hydroxychloroquine component of the Solidarity international randomized trial of medications to treat COVID-19.

Similarly, the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency instructed the organizers of COPCOV, an international trial of the use of hydroxychloroquine as prophylaxis against COVID-19, to suspend recruitment of patients. The SOLIDARITY trial briefly resumed, but that arm of the trial was ultimately suspended after a preliminary analysis suggested that hydroxychloroquine provided no benefit for patients with COVID-19.

Dr. Malički emphasized that governments and organizations should not “blindly trust journal articles” and make policy decisions based exclusively on study findings in published journals – even with the current improvements in the peer review process – without having their own experts conduct a thorough review of the data.

“If you are not willing to do your own due diligence, then at least be brave enough and say transparently why you are making this policy, or any other changes, and clearly state if your decision is based primarily or solely on the fact that ‘X’ study was published in ‘Y’ journal,” he stated.

Dr. Rao believes that the most important take-home message of the Surgisphere scandal is “that we should be skeptical and do our own due diligence about the kinds of data published – a responsibility that applies to all of us, whether we are investigators, editors at journals, the press, scientists, and readers.”

Dr. Rao reported being on the steering committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored MINT trial and the Bayer-sponsored PACIFIC AMI trial. Dr. Malički reports being a postdoc at METRICS Stanford in the past 3 years. Dr. Krumholz received expenses and/or personal fees from UnitedHealth, Element Science, Aetna, Facebook, the Siegfried and Jensen Law Firm, Arnold and Porter Law Firm, Martin/Baughman Law Firm, F-Prime, and the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases in Beijing. He is an owner of Refactor Health and HugoHealth and had grants and/or contracts from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the FDA, Johnson & Johnson, and the Shenzhen Center for Health Information.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In May 2020, two major scientific journals published and subsequently retracted studies that relied on data provided by the now-disgraced data analytics company Surgisphere.

One of the studies, published in The Lancet, reported an association between the antimalarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine and increased in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19. The second study, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, described an association between underlying cardiovascular disease, but not related drug therapy, with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The retractions in June 2020 followed an open letter to each publication penned by scientists, ethicists, and clinicians who flagged serious methodological and ethical anomalies in the data used in the studies.

On the 1-year anniversary, researchers and journal editors spoke about what was learned to reduce the risk of something like this happening again.

“The Surgisphere incident served as a wake-up call for everyone involved with scientific research to make sure that data have integrity and are robust,” Sunil Rao, MD, professor of medicine, Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., and editor-in-chief of Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, said in an interview.

“I’m sure this isn’t going to be the last incident of this nature, and we have to be vigilant about new datasets or datasets that we haven’t heard of as having a track record of publication,” Dr. Rao said.

Spotlight on authors

The editors of the Lancet Group responded to the “wake-up call” with a statement, Learning From a Retraction, which announced changes to reduce the risks of research and publication misconduct.

The changes affect multiple phases of the publication process. For example, the declaration form that authors must sign “will require that more than one author has directly accessed and verified the data reported in the manuscript.” Additionally, when a research article is the result of an academic and commercial partnership – as was the case in the two retracted studies – “one of the authors named as having accessed and verified data must be from the academic team.”

This was particularly important because it appears that the academic coauthors of the retracted studies did not have access to the data provided by Surgisphere, a private commercial entity.

Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, William Harvey Distinguished Chair in Advanced Cardiovascular Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was the lead author of both studies, declined to be interviewed for this article. In a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine editors requesting that the article be retracted, he wrote: “Because all the authors were not granted access to the raw data and the raw data could not be made available to a third-party auditor, we are unable to validate the primary data sources underlying our article.”

In a similar communication with The Lancet, Dr. Mehra wrote even more pointedly that, in light of the refusal of Surgisphere to make the data available to the third-party auditor, “we can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources.”

“It is very disturbing that the authors were willing to put their names on a paper without ever seeing and verifying the data,” Mario Malički, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at METRICS at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “Saying that they could ‘no longer vouch’ suggests that at one point they could vouch for it. Most likely they took its existence and veracity entirely on trust.”

Dr. Malički pointed out that one of the four criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for being an author on a study is the “agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.”

The new policies put forth by The Lancet are “encouraging,” but perhaps do not go far enough. “Every author, not only one or two authors, should personally take responsibility for the integrity of data,” he stated.

Many journals “adhere to ICMJE rules in principle and have checkboxes for authors to confirm that they guarantee the veracity of the data.” However, they “do not have the resources to verify the authors’ statements.”

Ideally, “it is the institutions where the researchers work that should guarantee the veracity of the raw data – but I do not know any university or institute that does this,” he said.

No ‘good-housekeeping’ seal

For articles based on large, real-world datasets, the Lancet Group will now require that editors ensure that at least one peer reviewer is “knowledgeable about the details of the dataset being reported and can understand its strengths and limitations in relation to the question being addressed.”

For studies that use “very large datasets,” the editors are now required to ensure that, in addition to a statistical peer review, a review from an “expert in data science” is obtained. Reviewers will also be explicitly asked if they have “concerns about research integrity or publication ethics regarding the manuscript they are reviewing.”

Although these changes are encouraging, Harlan Krumholz, MD, professor of medicine (cardiology), Yale University, New Haven, Conn., is not convinced that they are realistic.

Dr. Krumholz, who is also the founder and director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcome Research and Evaluation, said in an interview that “large, real-world datasets” are of two varieties. Datasets drawn from publicly available sources, such as Medicare or Medicaid health records, are utterly transparent.

By contrast, Surgisphere was a privately owned database, and “it is not unusual for privately owned databases to have proprietary data from multiple sources that the company may choose to keep confidential,” Dr. Krumholz said.

He noted that several large datasets are widely used for research purposes, such as IBM, Optum, and Komodo – a data analytics company that recently entered into partnership with a fourth company, PicnicHealth.

These companies receive deidentified electronic health records from health systems and insurers nationwide. Komodo boasts “real-time and longitudinal data on more than 325 million patients, representing more than 65 billion clinical encounters with 15 million new encounters added daily.”

“One has to raise an eyebrow – how were these data acquired? And, given that the U.S. has a population of around 328 million people, is it really plausible that a single company has health records of almost the entire U.S. population?” Dr. Krumholz commented. (A spokesperson for Komodo said in an interview that the company has records on 325 million U.S. patients.)

This is “an issue across the board with ‘real-world evidence,’ which is that it’s like the ‘Wild West’ – the transparencies of private databases are less than optimal and there are no common standards to help us move forward,” Dr. Krumholz said, noting that there is “no external authority overseeing, validating, or auditing these databases. In the end, we are trusting the companies.”

Although the Food and Drug Administration has laid out a framework for how real-world data and real-world evidence can be used to advance scientific research, the FDA does not oversee the databases.

“Thus, there is no ‘good housekeeping seal’ that a peer reviewer or author would be in a position to evaluate,” Dr. Krumholz said. “No journal can do an audit of these types of private databases, so ultimately, it boils down to trust.”

Nevertheless, there were red flags with Surgisphere, Dr. Rao pointed out. Unlike more established and widely used databases, the Surgisphere database had been catapulted from relative obscurity onto center stage, which should have given researchers pause.

AI-assisted peer review

A series of investigative reports by The Guardian raised questions about Sapan Desai, the CEO of Surgisphere, including the fact that hospitals purporting to have contributed data to Surgisphere had never heard of the company.

However, peer reviewers are not expected to be investigative reporters, explained Dr. Malički.

“In an ideal world, editors and peer reviewers would have a chance to look at raw data or would have a certificate from the academic institution the authors are affiliated with that the data have been inspected by the institution, but in the real world, of course, this does not happen,” he said.

Artificial intelligence software is being developed and deployed to assist in the peer review process, Dr. Malički noted. In July 2020, Frontiers Science News debuted its Artificial Intelligence Review Assistant to help editors, reviewers, and authors evaluate the quality of a manuscript. The program can make up to 20 recommendations, including “the assessment of language quality, the detection of plagiarism, and identification of potential conflicts of interest.” The program is now in use in all 103 journals published by Frontiers. Preliminary software is also available to detect statistical errors.

Another system under development is FAIRware, an initiative of the Research on Research Institute in partnership with the Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research. The partnership’s goal is to “develop an automated online tool (or suite of tools) to help researchers ensure that the datasets they produce are ‘FAIR’ at the point of creation,” said Dr. Malički, referring to the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) guiding principles for data management. The principles aim to increase the ability of machines to automatically find and use the data, as well as to support its reuse by individuals.

He added that these advanced tools cannot replace human reviewers, who will “likely always be a necessary quality check in the process.”

Greater transparency needed

Another limitation of peer review is the reviewers themselves, according to Dr. Malički. “It’s a step in the right direction that The Lancet is now requesting a peer reviewer with expertise in big datasets, but it does not go far enough to increase accountability of peer reviewers,” he said.

Dr. Malički is the co–editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review , which has “an open and transparent review process – meaning that we reveal the names of the reviewers to the public and we publish the full review report alongside the paper.” The publication also allows the authors to make public the original version they sent.

Dr. Malički cited several advantages to transparent peer review, particularly the increased accountability that results from placing potential conflicts of interest under the microscope.

As for the concern that identifying the reviewers might soften the review process, “there is little evidence to substantiate that concern,” he added.

Dr. Malički emphasized that making reviews public “is not a problem – people voice strong opinions at conferences and elsewhere. The question remains, who gets to decide if the criticism has been adequately addressed, so that the findings of the study still stand?”

He acknowledged that, “as in politics and on many social platforms, rage, hatred, and personal attacks divert the discussion from the topic at hand, which is why a good moderator is needed.”

A journal editor or a moderator at a scientific conference may be tasked with “stopping all talk not directly related to the topic.”

Widening the circle of scrutiny

Dr. Malički added: “A published paper should not be considered the ‘final word,’ even if it has gone through peer review and is published in a reputable journal. The peer-review process means that a limited number of people have seen the study.”

Once the study is published, “the whole world gets to see it and criticize it, and that widens the circle of scrutiny.”

One classic way to raise concerns about a study post publication is to write a letter to the journal editor. But there is no guarantee that the letter will be published or the authors notified of the feedback.

Dr. Malički encourages readers to use PubPeer, an online forum in which members of the public can post comments on scientific studies and articles.

Once a comment is posted, the authors are alerted. “There is no ‘police department’ that forces authors to acknowledge comments or forces journal editors to take action, but at least PubPeer guarantees that readers’ messages will reach the authors and – depending on how many people raise similar issues – the comments can lead to errata or even full retractions,” he said.

PubPeer was key in pointing out errors in a suspect study from France (which did not involve Surgisphere) that supported the use of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19.

A message to policy makers

High stakes are involved in ensuring the integrity of scientific publications: The French government revoked a decree that allowed hospitals to prescribe hydroxychloroquine for certain COVID-19 patients.

After the Surgisphere Lancet article, the World Health Organization temporarily halted enrollment in the hydroxychloroquine component of the Solidarity international randomized trial of medications to treat COVID-19.

Similarly, the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency instructed the organizers of COPCOV, an international trial of the use of hydroxychloroquine as prophylaxis against COVID-19, to suspend recruitment of patients. The SOLIDARITY trial briefly resumed, but that arm of the trial was ultimately suspended after a preliminary analysis suggested that hydroxychloroquine provided no benefit for patients with COVID-19.

Dr. Malički emphasized that governments and organizations should not “blindly trust journal articles” and make policy decisions based exclusively on study findings in published journals – even with the current improvements in the peer review process – without having their own experts conduct a thorough review of the data.

“If you are not willing to do your own due diligence, then at least be brave enough and say transparently why you are making this policy, or any other changes, and clearly state if your decision is based primarily or solely on the fact that ‘X’ study was published in ‘Y’ journal,” he stated.

Dr. Rao believes that the most important take-home message of the Surgisphere scandal is “that we should be skeptical and do our own due diligence about the kinds of data published – a responsibility that applies to all of us, whether we are investigators, editors at journals, the press, scientists, and readers.”

Dr. Rao reported being on the steering committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored MINT trial and the Bayer-sponsored PACIFIC AMI trial. Dr. Malički reports being a postdoc at METRICS Stanford in the past 3 years. Dr. Krumholz received expenses and/or personal fees from UnitedHealth, Element Science, Aetna, Facebook, the Siegfried and Jensen Law Firm, Arnold and Porter Law Firm, Martin/Baughman Law Firm, F-Prime, and the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases in Beijing. He is an owner of Refactor Health and HugoHealth and had grants and/or contracts from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the FDA, Johnson & Johnson, and the Shenzhen Center for Health Information.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In May 2020, two major scientific journals published and subsequently retracted studies that relied on data provided by the now-disgraced data analytics company Surgisphere.

One of the studies, published in The Lancet, reported an association between the antimalarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine and increased in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19. The second study, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, described an association between underlying cardiovascular disease, but not related drug therapy, with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The retractions in June 2020 followed an open letter to each publication penned by scientists, ethicists, and clinicians who flagged serious methodological and ethical anomalies in the data used in the studies.

On the 1-year anniversary, researchers and journal editors spoke about what was learned to reduce the risk of something like this happening again.

“The Surgisphere incident served as a wake-up call for everyone involved with scientific research to make sure that data have integrity and are robust,” Sunil Rao, MD, professor of medicine, Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., and editor-in-chief of Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, said in an interview.

“I’m sure this isn’t going to be the last incident of this nature, and we have to be vigilant about new datasets or datasets that we haven’t heard of as having a track record of publication,” Dr. Rao said.

Spotlight on authors

The editors of the Lancet Group responded to the “wake-up call” with a statement, Learning From a Retraction, which announced changes to reduce the risks of research and publication misconduct.

The changes affect multiple phases of the publication process. For example, the declaration form that authors must sign “will require that more than one author has directly accessed and verified the data reported in the manuscript.” Additionally, when a research article is the result of an academic and commercial partnership – as was the case in the two retracted studies – “one of the authors named as having accessed and verified data must be from the academic team.”

This was particularly important because it appears that the academic coauthors of the retracted studies did not have access to the data provided by Surgisphere, a private commercial entity.

Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, William Harvey Distinguished Chair in Advanced Cardiovascular Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was the lead author of both studies, declined to be interviewed for this article. In a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine editors requesting that the article be retracted, he wrote: “Because all the authors were not granted access to the raw data and the raw data could not be made available to a third-party auditor, we are unable to validate the primary data sources underlying our article.”

In a similar communication with The Lancet, Dr. Mehra wrote even more pointedly that, in light of the refusal of Surgisphere to make the data available to the third-party auditor, “we can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources.”

“It is very disturbing that the authors were willing to put their names on a paper without ever seeing and verifying the data,” Mario Malički, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at METRICS at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “Saying that they could ‘no longer vouch’ suggests that at one point they could vouch for it. Most likely they took its existence and veracity entirely on trust.”

Dr. Malički pointed out that one of the four criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for being an author on a study is the “agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.”

The new policies put forth by The Lancet are “encouraging,” but perhaps do not go far enough. “Every author, not only one or two authors, should personally take responsibility for the integrity of data,” he stated.

Many journals “adhere to ICMJE rules in principle and have checkboxes for authors to confirm that they guarantee the veracity of the data.” However, they “do not have the resources to verify the authors’ statements.”

Ideally, “it is the institutions where the researchers work that should guarantee the veracity of the raw data – but I do not know any university or institute that does this,” he said.

No ‘good-housekeeping’ seal

For articles based on large, real-world datasets, the Lancet Group will now require that editors ensure that at least one peer reviewer is “knowledgeable about the details of the dataset being reported and can understand its strengths and limitations in relation to the question being addressed.”

For studies that use “very large datasets,” the editors are now required to ensure that, in addition to a statistical peer review, a review from an “expert in data science” is obtained. Reviewers will also be explicitly asked if they have “concerns about research integrity or publication ethics regarding the manuscript they are reviewing.”

Although these changes are encouraging, Harlan Krumholz, MD, professor of medicine (cardiology), Yale University, New Haven, Conn., is not convinced that they are realistic.

Dr. Krumholz, who is also the founder and director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcome Research and Evaluation, said in an interview that “large, real-world datasets” are of two varieties. Datasets drawn from publicly available sources, such as Medicare or Medicaid health records, are utterly transparent.

By contrast, Surgisphere was a privately owned database, and “it is not unusual for privately owned databases to have proprietary data from multiple sources that the company may choose to keep confidential,” Dr. Krumholz said.

He noted that several large datasets are widely used for research purposes, such as IBM, Optum, and Komodo – a data analytics company that recently entered into partnership with a fourth company, PicnicHealth.

These companies receive deidentified electronic health records from health systems and insurers nationwide. Komodo boasts “real-time and longitudinal data on more than 325 million patients, representing more than 65 billion clinical encounters with 15 million new encounters added daily.”

“One has to raise an eyebrow – how were these data acquired? And, given that the U.S. has a population of around 328 million people, is it really plausible that a single company has health records of almost the entire U.S. population?” Dr. Krumholz commented. (A spokesperson for Komodo said in an interview that the company has records on 325 million U.S. patients.)

This is “an issue across the board with ‘real-world evidence,’ which is that it’s like the ‘Wild West’ – the transparencies of private databases are less than optimal and there are no common standards to help us move forward,” Dr. Krumholz said, noting that there is “no external authority overseeing, validating, or auditing these databases. In the end, we are trusting the companies.”

Although the Food and Drug Administration has laid out a framework for how real-world data and real-world evidence can be used to advance scientific research, the FDA does not oversee the databases.

“Thus, there is no ‘good housekeeping seal’ that a peer reviewer or author would be in a position to evaluate,” Dr. Krumholz said. “No journal can do an audit of these types of private databases, so ultimately, it boils down to trust.”

Nevertheless, there were red flags with Surgisphere, Dr. Rao pointed out. Unlike more established and widely used databases, the Surgisphere database had been catapulted from relative obscurity onto center stage, which should have given researchers pause.

AI-assisted peer review

A series of investigative reports by The Guardian raised questions about Sapan Desai, the CEO of Surgisphere, including the fact that hospitals purporting to have contributed data to Surgisphere had never heard of the company.

However, peer reviewers are not expected to be investigative reporters, explained Dr. Malički.

“In an ideal world, editors and peer reviewers would have a chance to look at raw data or would have a certificate from the academic institution the authors are affiliated with that the data have been inspected by the institution, but in the real world, of course, this does not happen,” he said.

Artificial intelligence software is being developed and deployed to assist in the peer review process, Dr. Malički noted. In July 2020, Frontiers Science News debuted its Artificial Intelligence Review Assistant to help editors, reviewers, and authors evaluate the quality of a manuscript. The program can make up to 20 recommendations, including “the assessment of language quality, the detection of plagiarism, and identification of potential conflicts of interest.” The program is now in use in all 103 journals published by Frontiers. Preliminary software is also available to detect statistical errors.

Another system under development is FAIRware, an initiative of the Research on Research Institute in partnership with the Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research. The partnership’s goal is to “develop an automated online tool (or suite of tools) to help researchers ensure that the datasets they produce are ‘FAIR’ at the point of creation,” said Dr. Malički, referring to the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) guiding principles for data management. The principles aim to increase the ability of machines to automatically find and use the data, as well as to support its reuse by individuals.

He added that these advanced tools cannot replace human reviewers, who will “likely always be a necessary quality check in the process.”

Greater transparency needed

Another limitation of peer review is the reviewers themselves, according to Dr. Malički. “It’s a step in the right direction that The Lancet is now requesting a peer reviewer with expertise in big datasets, but it does not go far enough to increase accountability of peer reviewers,” he said.

Dr. Malički is the co–editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review , which has “an open and transparent review process – meaning that we reveal the names of the reviewers to the public and we publish the full review report alongside the paper.” The publication also allows the authors to make public the original version they sent.

Dr. Malički cited several advantages to transparent peer review, particularly the increased accountability that results from placing potential conflicts of interest under the microscope.

As for the concern that identifying the reviewers might soften the review process, “there is little evidence to substantiate that concern,” he added.

Dr. Malički emphasized that making reviews public “is not a problem – people voice strong opinions at conferences and elsewhere. The question remains, who gets to decide if the criticism has been adequately addressed, so that the findings of the study still stand?”

He acknowledged that, “as in politics and on many social platforms, rage, hatred, and personal attacks divert the discussion from the topic at hand, which is why a good moderator is needed.”

A journal editor or a moderator at a scientific conference may be tasked with “stopping all talk not directly related to the topic.”

Widening the circle of scrutiny

Dr. Malički added: “A published paper should not be considered the ‘final word,’ even if it has gone through peer review and is published in a reputable journal. The peer-review process means that a limited number of people have seen the study.”

Once the study is published, “the whole world gets to see it and criticize it, and that widens the circle of scrutiny.”

One classic way to raise concerns about a study post publication is to write a letter to the journal editor. But there is no guarantee that the letter will be published or the authors notified of the feedback.

Dr. Malički encourages readers to use PubPeer, an online forum in which members of the public can post comments on scientific studies and articles.

Once a comment is posted, the authors are alerted. “There is no ‘police department’ that forces authors to acknowledge comments or forces journal editors to take action, but at least PubPeer guarantees that readers’ messages will reach the authors and – depending on how many people raise similar issues – the comments can lead to errata or even full retractions,” he said.

PubPeer was key in pointing out errors in a suspect study from France (which did not involve Surgisphere) that supported the use of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19.

A message to policy makers

High stakes are involved in ensuring the integrity of scientific publications: The French government revoked a decree that allowed hospitals to prescribe hydroxychloroquine for certain COVID-19 patients.

After the Surgisphere Lancet article, the World Health Organization temporarily halted enrollment in the hydroxychloroquine component of the Solidarity international randomized trial of medications to treat COVID-19.

Similarly, the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency instructed the organizers of COPCOV, an international trial of the use of hydroxychloroquine as prophylaxis against COVID-19, to suspend recruitment of patients. The SOLIDARITY trial briefly resumed, but that arm of the trial was ultimately suspended after a preliminary analysis suggested that hydroxychloroquine provided no benefit for patients with COVID-19.

Dr. Malički emphasized that governments and organizations should not “blindly trust journal articles” and make policy decisions based exclusively on study findings in published journals – even with the current improvements in the peer review process – without having their own experts conduct a thorough review of the data.

“If you are not willing to do your own due diligence, then at least be brave enough and say transparently why you are making this policy, or any other changes, and clearly state if your decision is based primarily or solely on the fact that ‘X’ study was published in ‘Y’ journal,” he stated.

Dr. Rao believes that the most important take-home message of the Surgisphere scandal is “that we should be skeptical and do our own due diligence about the kinds of data published – a responsibility that applies to all of us, whether we are investigators, editors at journals, the press, scientists, and readers.”

Dr. Rao reported being on the steering committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored MINT trial and the Bayer-sponsored PACIFIC AMI trial. Dr. Malički reports being a postdoc at METRICS Stanford in the past 3 years. Dr. Krumholz received expenses and/or personal fees from UnitedHealth, Element Science, Aetna, Facebook, the Siegfried and Jensen Law Firm, Arnold and Porter Law Firm, Martin/Baughman Law Firm, F-Prime, and the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases in Beijing. He is an owner of Refactor Health and HugoHealth and had grants and/or contracts from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the FDA, Johnson & Johnson, and the Shenzhen Center for Health Information.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Few clinical guidelines exist for treating post-COVID symptoms

As doctors struggled through several surges of COVID-19 infections, most of what we learned was acquired through real-life experience. While many treatment options were promoted, most flat-out failed to be real therapeutics at all. Now that we have a safe and effective vaccine, we can prevent many infections from this virus. However, we are still left to manage the many post-COVID symptoms our patients continue to suffer with.

Symptoms following infection can last for months and range widely from “brain fog,” fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, generalized weakness, depression, and a host of others. Patients may experience one or all of these symptoms, and there is currently no good way to predict who will go on to become a COVID “long hauler”.

Following the example of being educated by COVID as it happened, the same is true for managing post-COVID symptoms. The medical community still has a poor understanding of why some people develop it and there are few evidence-based studies to support any treatment modalities.

which they define as “new, recurring, or ongoing symptoms more than 4 weeks after infection, sometimes after initial symptom recovery.” It is important to note that these symptoms can occur in any degree of sickness during the acute infection, including in those who were asymptomatic. Even the actual name of this post-COVID syndrome is still being developed, with several other names being used for it as well.

While the guidelines are quite extensive, the actual clinical recommendations are still vague. For example, it is advised to let the patient know that post-COVID symptoms are still not well understood. While it is important to be transparent with patients, this does little to reassure them. Patients look to doctors, especially their primary care physicians, to guide them on the best treatment paths. Yet, we currently have none for post-COVID syndrome.

It is also advised to treat the patients’ symptoms and help improve functioning. For many diseases, doctors like to get to the root cause of the problem. Treating a symptom often masks an underlying condition. It may make the patient feel better and improve what they are capable of doing, which is important, but it also fails to unmask the real problem. It is also important to note that symptoms can be out of proportion to clinical findings and should not be dismissed: we just don’t have the answers yet.

One helpful recommendation is having a patient keep a diary of their symptoms. This will help both the patient and doctor learn what may be triggering factors. If it is, for example, exertion that induces breathlessness, perhaps the patient can gradually increase their level of activity to minimize symptoms. Additionally, a “comprehensive rehabilitation program” is also advised and this can greatly assist addressing all the issues a patient is experiencing, physically and medically.

It is also advised that management of underlying medical conditions be optimized. While this is very important, it is not something specific to post-COVID syndrome: All patients should have their underlying medical conditions well controlled. It might be that the patient is paying more attention to their overall health, which is a good thing. However, this does not necessarily reduce the current symptoms a patient is experiencing.

The CDC makes a good attempt to offer guidance in the frustrating management of post-COVID syndrome. However, their clinical guidelines fail to offer specific management tools specific to treating post-COVID patients. The recommendations offered are more helpful to health in general. The fact that more specific recommendations are lacking is simply caused by the lack of knowledge of this condition at present. As more research is conducted and more knowledge obtained, new guidelines should become more detailed.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

As doctors struggled through several surges of COVID-19 infections, most of what we learned was acquired through real-life experience. While many treatment options were promoted, most flat-out failed to be real therapeutics at all. Now that we have a safe and effective vaccine, we can prevent many infections from this virus. However, we are still left to manage the many post-COVID symptoms our patients continue to suffer with.

Symptoms following infection can last for months and range widely from “brain fog,” fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, generalized weakness, depression, and a host of others. Patients may experience one or all of these symptoms, and there is currently no good way to predict who will go on to become a COVID “long hauler”.

Following the example of being educated by COVID as it happened, the same is true for managing post-COVID symptoms. The medical community still has a poor understanding of why some people develop it and there are few evidence-based studies to support any treatment modalities.

which they define as “new, recurring, or ongoing symptoms more than 4 weeks after infection, sometimes after initial symptom recovery.” It is important to note that these symptoms can occur in any degree of sickness during the acute infection, including in those who were asymptomatic. Even the actual name of this post-COVID syndrome is still being developed, with several other names being used for it as well.

While the guidelines are quite extensive, the actual clinical recommendations are still vague. For example, it is advised to let the patient know that post-COVID symptoms are still not well understood. While it is important to be transparent with patients, this does little to reassure them. Patients look to doctors, especially their primary care physicians, to guide them on the best treatment paths. Yet, we currently have none for post-COVID syndrome.

It is also advised to treat the patients’ symptoms and help improve functioning. For many diseases, doctors like to get to the root cause of the problem. Treating a symptom often masks an underlying condition. It may make the patient feel better and improve what they are capable of doing, which is important, but it also fails to unmask the real problem. It is also important to note that symptoms can be out of proportion to clinical findings and should not be dismissed: we just don’t have the answers yet.

One helpful recommendation is having a patient keep a diary of their symptoms. This will help both the patient and doctor learn what may be triggering factors. If it is, for example, exertion that induces breathlessness, perhaps the patient can gradually increase their level of activity to minimize symptoms. Additionally, a “comprehensive rehabilitation program” is also advised and this can greatly assist addressing all the issues a patient is experiencing, physically and medically.

It is also advised that management of underlying medical conditions be optimized. While this is very important, it is not something specific to post-COVID syndrome: All patients should have their underlying medical conditions well controlled. It might be that the patient is paying more attention to their overall health, which is a good thing. However, this does not necessarily reduce the current symptoms a patient is experiencing.

The CDC makes a good attempt to offer guidance in the frustrating management of post-COVID syndrome. However, their clinical guidelines fail to offer specific management tools specific to treating post-COVID patients. The recommendations offered are more helpful to health in general. The fact that more specific recommendations are lacking is simply caused by the lack of knowledge of this condition at present. As more research is conducted and more knowledge obtained, new guidelines should become more detailed.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

As doctors struggled through several surges of COVID-19 infections, most of what we learned was acquired through real-life experience. While many treatment options were promoted, most flat-out failed to be real therapeutics at all. Now that we have a safe and effective vaccine, we can prevent many infections from this virus. However, we are still left to manage the many post-COVID symptoms our patients continue to suffer with.

Symptoms following infection can last for months and range widely from “brain fog,” fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, generalized weakness, depression, and a host of others. Patients may experience one or all of these symptoms, and there is currently no good way to predict who will go on to become a COVID “long hauler”.

Following the example of being educated by COVID as it happened, the same is true for managing post-COVID symptoms. The medical community still has a poor understanding of why some people develop it and there are few evidence-based studies to support any treatment modalities.

which they define as “new, recurring, or ongoing symptoms more than 4 weeks after infection, sometimes after initial symptom recovery.” It is important to note that these symptoms can occur in any degree of sickness during the acute infection, including in those who were asymptomatic. Even the actual name of this post-COVID syndrome is still being developed, with several other names being used for it as well.

While the guidelines are quite extensive, the actual clinical recommendations are still vague. For example, it is advised to let the patient know that post-COVID symptoms are still not well understood. While it is important to be transparent with patients, this does little to reassure them. Patients look to doctors, especially their primary care physicians, to guide them on the best treatment paths. Yet, we currently have none for post-COVID syndrome.

It is also advised to treat the patients’ symptoms and help improve functioning. For many diseases, doctors like to get to the root cause of the problem. Treating a symptom often masks an underlying condition. It may make the patient feel better and improve what they are capable of doing, which is important, but it also fails to unmask the real problem. It is also important to note that symptoms can be out of proportion to clinical findings and should not be dismissed: we just don’t have the answers yet.

One helpful recommendation is having a patient keep a diary of their symptoms. This will help both the patient and doctor learn what may be triggering factors. If it is, for example, exertion that induces breathlessness, perhaps the patient can gradually increase their level of activity to minimize symptoms. Additionally, a “comprehensive rehabilitation program” is also advised and this can greatly assist addressing all the issues a patient is experiencing, physically and medically.

It is also advised that management of underlying medical conditions be optimized. While this is very important, it is not something specific to post-COVID syndrome: All patients should have their underlying medical conditions well controlled. It might be that the patient is paying more attention to their overall health, which is a good thing. However, this does not necessarily reduce the current symptoms a patient is experiencing.

The CDC makes a good attempt to offer guidance in the frustrating management of post-COVID syndrome. However, their clinical guidelines fail to offer specific management tools specific to treating post-COVID patients. The recommendations offered are more helpful to health in general. The fact that more specific recommendations are lacking is simply caused by the lack of knowledge of this condition at present. As more research is conducted and more knowledge obtained, new guidelines should become more detailed.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

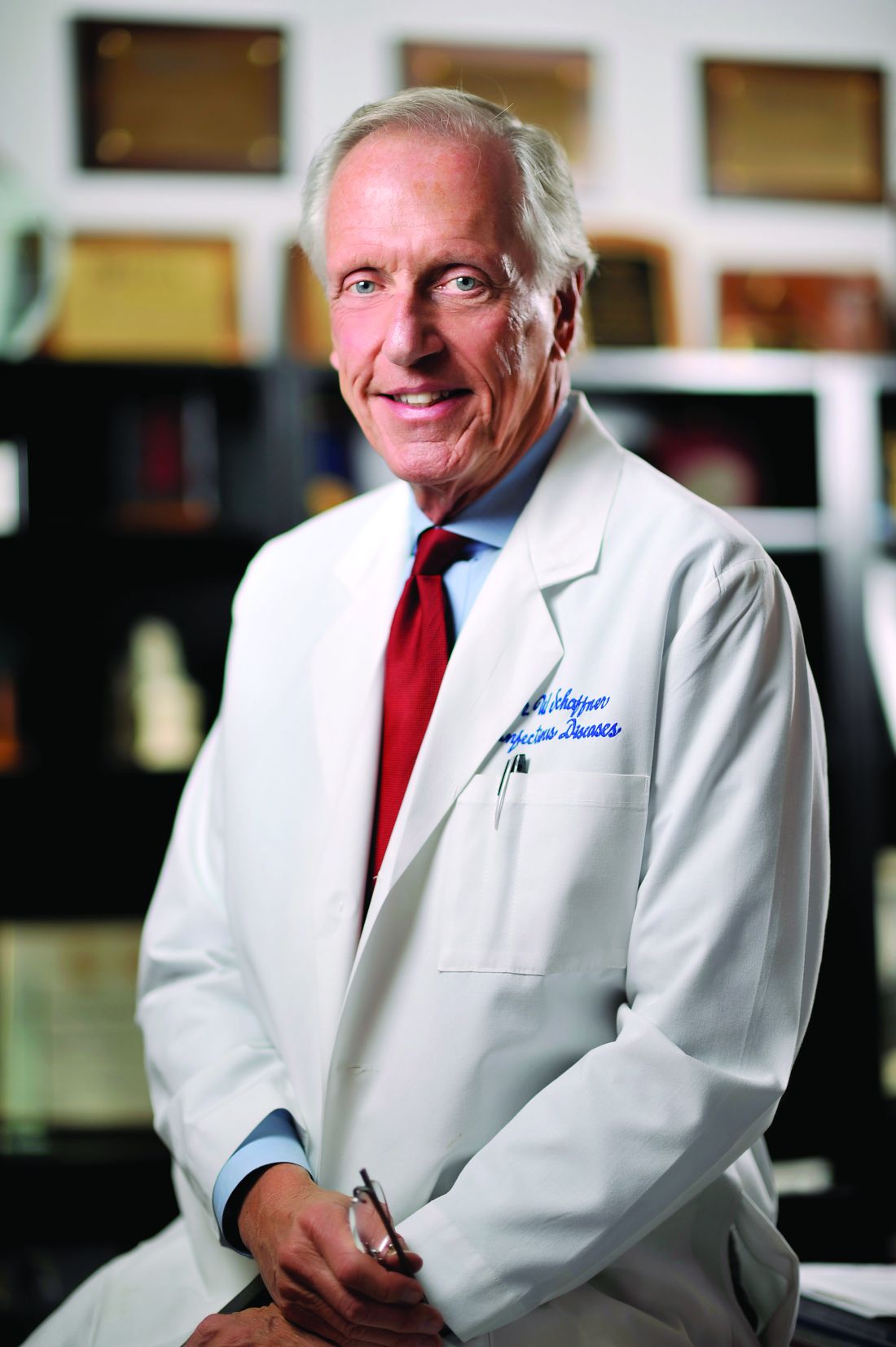

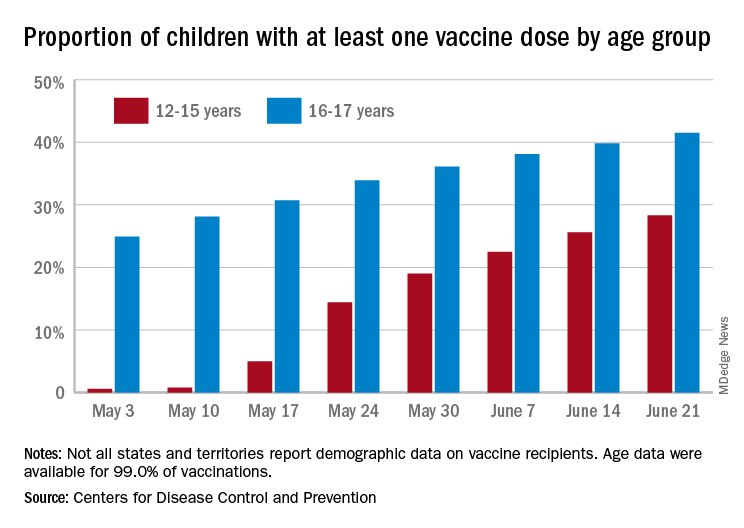

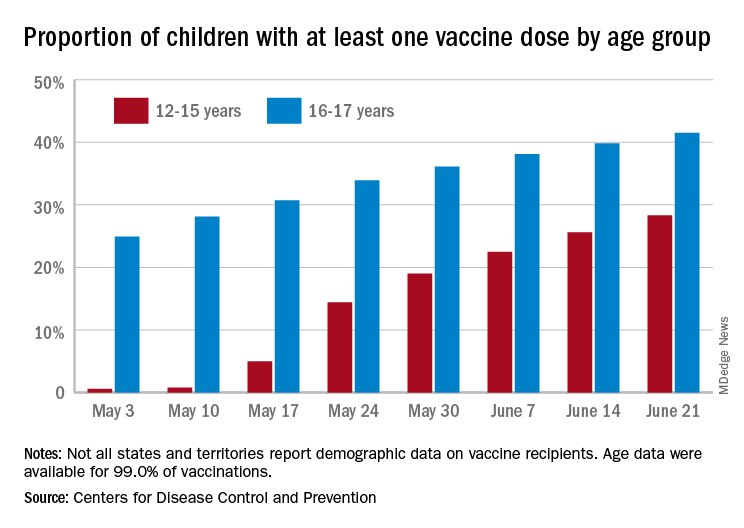

FDA to add myocarditis warning to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines

The Food and Drug Administration is adding a warning to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines’ fact sheets as medical experts continue to investigate cases of heart inflammation, which are rare but are more likely to occur in young men and teen boys.

Doran Fink, MD, PhD, deputy director of the FDA’s division of vaccines and related products applications, told a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel on June 23 that the FDA is finalizing language on a warning statement for health care providers, vaccine recipients, and parents or caregivers of teens.

The incidents are more likely to follow the second dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine, with chest pain and other symptoms occurring within several days to a week, the warning will note.

“Based on limited follow-up, most cases appear to have been associated with resolution of symptoms, but limited information is available about potential long-term sequelae,” Dr. Fink said, describing the statement to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, independent experts who advise the CDC.

“Symptoms suggestive of myocarditis or pericarditis should result in vaccine recipients seeking medical attention,” he said.

Benefits outweigh risks

Although no formal vote occurred after the meeting, the ACIP members delivered a strong endorsement for continuing to vaccinate 12- to 29-year-olds with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines despite the warning.

“To me it’s clear, based on current information, that the benefits of vaccine clearly outweigh the risks,” said ACIP member Veronica McNally, president and CEO of the Franny Strong Foundation in Bloomfield, Mich., a sentiment echoed by other members.

As ACIP was meeting, leaders of the nation’s major physician, nurse, and public health associations issued a statement supporting continued vaccination: “The facts are clear: this is an extremely rare side effect, and only an exceedingly small number of people will experience it after vaccination.

“Importantly, for the young people who do, most cases are mild, and individuals recover often on their own or with minimal treatment. In addition, we know that myocarditis and pericarditis are much more common if you get COVID-19, and the risks to the heart from COVID-19 infection can be more severe.”

ACIP heard the evidence behind that claim. According to the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which contains data from more than 12 million medical records, myocarditis or pericarditis occurs in 12- to 39-year-olds at a rate of 8 per 1 million after the second Pfizer dose and 19.8 per 1 million after the second Moderna dose.

The CDC continues to investigate the link between the mRNA vaccines and heart inflammation, including any differences between the vaccines.

Most of the symptoms resolved quickly, said Tom Shimabukuro, deputy director of CDC’s Immunization Safety Office. Of 323 cases analyzed by the CDC, 309 were hospitalized, 295 were discharged, and 218, or 79%, had recovered from symptoms.

“Most postvaccine myocarditis has been responding to minimal treatment,” pediatric cardiologist Matthew Oster, MD, MPH, from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, told the panel.

COVID ‘risks are higher’

Overall, the CDC has reported 2,767 COVID-19 deaths among people aged 12-29 years, and there have been 4,018 reported cases of the COVID-linked inflammatory disorder MIS-C since the beginning of the pandemic.

That amounts to 1 MIS-C case in every 3,200 COVID infections – 36% of them among teens aged 12-20 years and 62% among children who are Hispanic or Black and non-Hispanic, according to a CDC presentation.

The CDC estimated that every 1 million second-dose COVID vaccines administered to 12- to 17-year-old boys could prevent 5,700 cases of COVID-19, 215 hospitalizations, 71 ICU admissions, and 2 deaths. There could also be 56-69 myocarditis cases.

The emergence of new variants in the United States and the skewed pattern of vaccination around the country also may increase the risk to unvaccinated young people, noted Grace Lee, MD, MPH, chair of the ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup and a pediatric infectious disease physician at Stanford (Calif.) Children’s Health.

“If you’re in an area with low vaccination, the risks are higher,” she said. “The benefits [of the vaccine] are going to be far, far greater than any risk.”

Individuals, parents, and their clinicians should consider the full scope of risk when making decisions about vaccination, she said.

As the pandemic evolves, medical experts have to balance the known risks and benefits while they gather more information, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease physician at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

“The story is not over,” Dr. Schaffner said in an interview. “Clearly, we are still working in the face of a pandemic, so there’s urgency to continue vaccinating. But they would like to know more about the long-term consequences of the myocarditis.”

Booster possibilities

Meanwhile, ACIP began conversations on the parameters for a possible vaccine booster. For now, there are simply questions: Would a third vaccine help the immunocompromised gain protection? Should people get a different type of vaccine – mRNA versus adenovirus vector – for their booster? Most important, how long do antibodies last?

“Prior to going around giving everyone boosters, we really need to improve the overall vaccination coverage,” said Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University. “That will protect everyone.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration is adding a warning to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines’ fact sheets as medical experts continue to investigate cases of heart inflammation, which are rare but are more likely to occur in young men and teen boys.

Doran Fink, MD, PhD, deputy director of the FDA’s division of vaccines and related products applications, told a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel on June 23 that the FDA is finalizing language on a warning statement for health care providers, vaccine recipients, and parents or caregivers of teens.

The incidents are more likely to follow the second dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine, with chest pain and other symptoms occurring within several days to a week, the warning will note.

“Based on limited follow-up, most cases appear to have been associated with resolution of symptoms, but limited information is available about potential long-term sequelae,” Dr. Fink said, describing the statement to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, independent experts who advise the CDC.

“Symptoms suggestive of myocarditis or pericarditis should result in vaccine recipients seeking medical attention,” he said.

Benefits outweigh risks

Although no formal vote occurred after the meeting, the ACIP members delivered a strong endorsement for continuing to vaccinate 12- to 29-year-olds with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines despite the warning.

“To me it’s clear, based on current information, that the benefits of vaccine clearly outweigh the risks,” said ACIP member Veronica McNally, president and CEO of the Franny Strong Foundation in Bloomfield, Mich., a sentiment echoed by other members.

As ACIP was meeting, leaders of the nation’s major physician, nurse, and public health associations issued a statement supporting continued vaccination: “The facts are clear: this is an extremely rare side effect, and only an exceedingly small number of people will experience it after vaccination.

“Importantly, for the young people who do, most cases are mild, and individuals recover often on their own or with minimal treatment. In addition, we know that myocarditis and pericarditis are much more common if you get COVID-19, and the risks to the heart from COVID-19 infection can be more severe.”

ACIP heard the evidence behind that claim. According to the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which contains data from more than 12 million medical records, myocarditis or pericarditis occurs in 12- to 39-year-olds at a rate of 8 per 1 million after the second Pfizer dose and 19.8 per 1 million after the second Moderna dose.

The CDC continues to investigate the link between the mRNA vaccines and heart inflammation, including any differences between the vaccines.

Most of the symptoms resolved quickly, said Tom Shimabukuro, deputy director of CDC’s Immunization Safety Office. Of 323 cases analyzed by the CDC, 309 were hospitalized, 295 were discharged, and 218, or 79%, had recovered from symptoms.

“Most postvaccine myocarditis has been responding to minimal treatment,” pediatric cardiologist Matthew Oster, MD, MPH, from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, told the panel.

COVID ‘risks are higher’

Overall, the CDC has reported 2,767 COVID-19 deaths among people aged 12-29 years, and there have been 4,018 reported cases of the COVID-linked inflammatory disorder MIS-C since the beginning of the pandemic.

That amounts to 1 MIS-C case in every 3,200 COVID infections – 36% of them among teens aged 12-20 years and 62% among children who are Hispanic or Black and non-Hispanic, according to a CDC presentation.

The CDC estimated that every 1 million second-dose COVID vaccines administered to 12- to 17-year-old boys could prevent 5,700 cases of COVID-19, 215 hospitalizations, 71 ICU admissions, and 2 deaths. There could also be 56-69 myocarditis cases.

The emergence of new variants in the United States and the skewed pattern of vaccination around the country also may increase the risk to unvaccinated young people, noted Grace Lee, MD, MPH, chair of the ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup and a pediatric infectious disease physician at Stanford (Calif.) Children’s Health.

“If you’re in an area with low vaccination, the risks are higher,” she said. “The benefits [of the vaccine] are going to be far, far greater than any risk.”

Individuals, parents, and their clinicians should consider the full scope of risk when making decisions about vaccination, she said.

As the pandemic evolves, medical experts have to balance the known risks and benefits while they gather more information, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease physician at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

“The story is not over,” Dr. Schaffner said in an interview. “Clearly, we are still working in the face of a pandemic, so there’s urgency to continue vaccinating. But they would like to know more about the long-term consequences of the myocarditis.”

Booster possibilities

Meanwhile, ACIP began conversations on the parameters for a possible vaccine booster. For now, there are simply questions: Would a third vaccine help the immunocompromised gain protection? Should people get a different type of vaccine – mRNA versus adenovirus vector – for their booster? Most important, how long do antibodies last?

“Prior to going around giving everyone boosters, we really need to improve the overall vaccination coverage,” said Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University. “That will protect everyone.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration is adding a warning to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines’ fact sheets as medical experts continue to investigate cases of heart inflammation, which are rare but are more likely to occur in young men and teen boys.

Doran Fink, MD, PhD, deputy director of the FDA’s division of vaccines and related products applications, told a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel on June 23 that the FDA is finalizing language on a warning statement for health care providers, vaccine recipients, and parents or caregivers of teens.

The incidents are more likely to follow the second dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine, with chest pain and other symptoms occurring within several days to a week, the warning will note.

“Based on limited follow-up, most cases appear to have been associated with resolution of symptoms, but limited information is available about potential long-term sequelae,” Dr. Fink said, describing the statement to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, independent experts who advise the CDC.

“Symptoms suggestive of myocarditis or pericarditis should result in vaccine recipients seeking medical attention,” he said.

Benefits outweigh risks

Although no formal vote occurred after the meeting, the ACIP members delivered a strong endorsement for continuing to vaccinate 12- to 29-year-olds with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines despite the warning.

“To me it’s clear, based on current information, that the benefits of vaccine clearly outweigh the risks,” said ACIP member Veronica McNally, president and CEO of the Franny Strong Foundation in Bloomfield, Mich., a sentiment echoed by other members.

As ACIP was meeting, leaders of the nation’s major physician, nurse, and public health associations issued a statement supporting continued vaccination: “The facts are clear: this is an extremely rare side effect, and only an exceedingly small number of people will experience it after vaccination.

“Importantly, for the young people who do, most cases are mild, and individuals recover often on their own or with minimal treatment. In addition, we know that myocarditis and pericarditis are much more common if you get COVID-19, and the risks to the heart from COVID-19 infection can be more severe.”

ACIP heard the evidence behind that claim. According to the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which contains data from more than 12 million medical records, myocarditis or pericarditis occurs in 12- to 39-year-olds at a rate of 8 per 1 million after the second Pfizer dose and 19.8 per 1 million after the second Moderna dose.

The CDC continues to investigate the link between the mRNA vaccines and heart inflammation, including any differences between the vaccines.

Most of the symptoms resolved quickly, said Tom Shimabukuro, deputy director of CDC’s Immunization Safety Office. Of 323 cases analyzed by the CDC, 309 were hospitalized, 295 were discharged, and 218, or 79%, had recovered from symptoms.

“Most postvaccine myocarditis has been responding to minimal treatment,” pediatric cardiologist Matthew Oster, MD, MPH, from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, told the panel.

COVID ‘risks are higher’

Overall, the CDC has reported 2,767 COVID-19 deaths among people aged 12-29 years, and there have been 4,018 reported cases of the COVID-linked inflammatory disorder MIS-C since the beginning of the pandemic.

That amounts to 1 MIS-C case in every 3,200 COVID infections – 36% of them among teens aged 12-20 years and 62% among children who are Hispanic or Black and non-Hispanic, according to a CDC presentation.

The CDC estimated that every 1 million second-dose COVID vaccines administered to 12- to 17-year-old boys could prevent 5,700 cases of COVID-19, 215 hospitalizations, 71 ICU admissions, and 2 deaths. There could also be 56-69 myocarditis cases.

The emergence of new variants in the United States and the skewed pattern of vaccination around the country also may increase the risk to unvaccinated young people, noted Grace Lee, MD, MPH, chair of the ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup and a pediatric infectious disease physician at Stanford (Calif.) Children’s Health.

“If you’re in an area with low vaccination, the risks are higher,” she said. “The benefits [of the vaccine] are going to be far, far greater than any risk.”

Individuals, parents, and their clinicians should consider the full scope of risk when making decisions about vaccination, she said.

As the pandemic evolves, medical experts have to balance the known risks and benefits while they gather more information, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease physician at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

“The story is not over,” Dr. Schaffner said in an interview. “Clearly, we are still working in the face of a pandemic, so there’s urgency to continue vaccinating. But they would like to know more about the long-term consequences of the myocarditis.”

Booster possibilities

Meanwhile, ACIP began conversations on the parameters for a possible vaccine booster. For now, there are simply questions: Would a third vaccine help the immunocompromised gain protection? Should people get a different type of vaccine – mRNA versus adenovirus vector – for their booster? Most important, how long do antibodies last?

“Prior to going around giving everyone boosters, we really need to improve the overall vaccination coverage,” said Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University. “That will protect everyone.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Dreck’ to drama: How the media handled, and got handled by, COVID

For well over a year, the COVID-19 pandemic has been the biggest story in the world, costing millions of lives, impacting a presidential election, and quaking economies around the world.

But as vaccination rates increase and restrictions relax across the United States, relief is beginning to mix with reflection. Part of that contemplation means grappling with how the media depicted the crisis – in ways that were helpful, harmful, and somewhere in between.

“This story was so overwhelming, and the amount of journalism done about it was also overwhelming, and it’s going to be a while before we can do any kind of comprehensive overview of how journalism really performed,” said Maryn McKenna, an independent journalist and journalism professor at Emory University, Atlanta, who specializes in public and global health.

Some ‘heroically good’ reporting

The pandemic hit at a time when journalism was under a lot of pressure from external forces – undermined by politics, swimming through a sea of misinformation, and pressed by financial pressure to produce more stories more quickly, said Emily Bell, founding director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, New York.

The pandemic drove enormous audiences to news outlets, as people searched for reliable information, and increased the appreciation many people felt for the work of journalists, she said.

“I think there’s been some heroically good reporting and some really empathetic reporting as well,” said Ms. Bell. She cites The New York Times stories honoring the nearly 100,000 people lost to COVID-19 in May 2020 and The Atlantic’s COVID Tracking Project as exceptionally good examples.

Journalism is part of a complex, and evolving, information ecosystem characterized by “traditional” television, radio, and newspapers but also social media, search engine results, niche online news outlets, and clickbait sites.