User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

‘Deeper dive’ into opioid overdose deaths during COVID pandemic

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: Weekly cases top 200,000, vaccinations down

Weekly pediatric cases of COVID-19 exceeded 200,000 for just the second time during the pandemic, while new vaccinations in children continued to decline.

The weekly count has now increased for 9 consecutive weeks, during which time it has risen by over 2,300%, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Total cases in children number almost 4.8 million since the pandemic started.

Vaccinations in children are following a different trend. Vaccine initiation has dropped 3 weeks in a row for both of the eligible age groups: First doses administered were down by 29% among 12- to 15-year-olds over that span and by 32% in 16- to 17-year-olds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since vaccination for children aged 12-15 years started in May, 49% had received at least one dose, and just over 36% were fully vaccinated as of Aug. 30. Among children aged 16-17 years, who have been eligible since December, 57.5% had gotten at least one dose of the vaccine and 46% have completed the two-dose regimen. The total number of children with at least one dose, including those under age 12 who are involved in clinical trials, was about 12 million, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

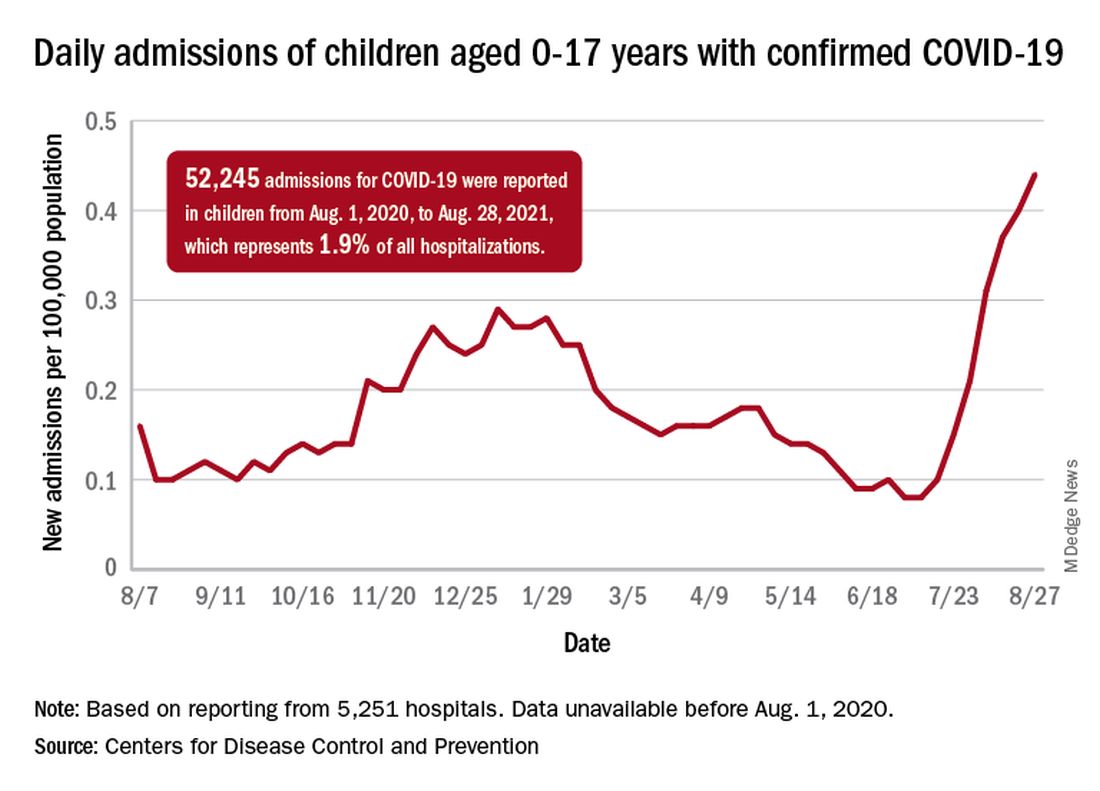

Hospitalizations are higher than ever

The recent rise in new child cases has been accompanied by an unprecedented increase in hospitalizations. The daily rate in children aged 0-17 years, which did not surpass 0.30 new admissions per 100,000 population during the worst of the winter surge, had risen to 0.45 per 100,000 by Aug. 26. Since July 4, when the new-admission rate was at its low point of 0.07 per 100,000, hospitalizations in children have jumped by 543%, based on data reported to the CDC by 5,251 hospitals.

A total of 52,245 children were admitted with confirmed COVID-19 from Aug. 1, 2020, when the CDC dataset begins, to Aug. 28, 2021. Those children represent 1.9% of all COVID admissions (2.7 million) in the United States over that period, the CDC said.

Total COVID-related deaths in children are up to 425 in the 48 jurisdictions (45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that provide mortality data by age, the AAP and the CHA said.

Record-high numbers for the previous 2 reporting weeks – 23 deaths during Aug. 20-26 and 24 deaths during Aug. 13-19, when the previous weekly high was 16 – at least partially reflect the recent addition of South Carolina and New Mexico to the AAP/CHA database, as the two states just started reporting age-related data.

Weekly pediatric cases of COVID-19 exceeded 200,000 for just the second time during the pandemic, while new vaccinations in children continued to decline.

The weekly count has now increased for 9 consecutive weeks, during which time it has risen by over 2,300%, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Total cases in children number almost 4.8 million since the pandemic started.

Vaccinations in children are following a different trend. Vaccine initiation has dropped 3 weeks in a row for both of the eligible age groups: First doses administered were down by 29% among 12- to 15-year-olds over that span and by 32% in 16- to 17-year-olds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since vaccination for children aged 12-15 years started in May, 49% had received at least one dose, and just over 36% were fully vaccinated as of Aug. 30. Among children aged 16-17 years, who have been eligible since December, 57.5% had gotten at least one dose of the vaccine and 46% have completed the two-dose regimen. The total number of children with at least one dose, including those under age 12 who are involved in clinical trials, was about 12 million, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Hospitalizations are higher than ever

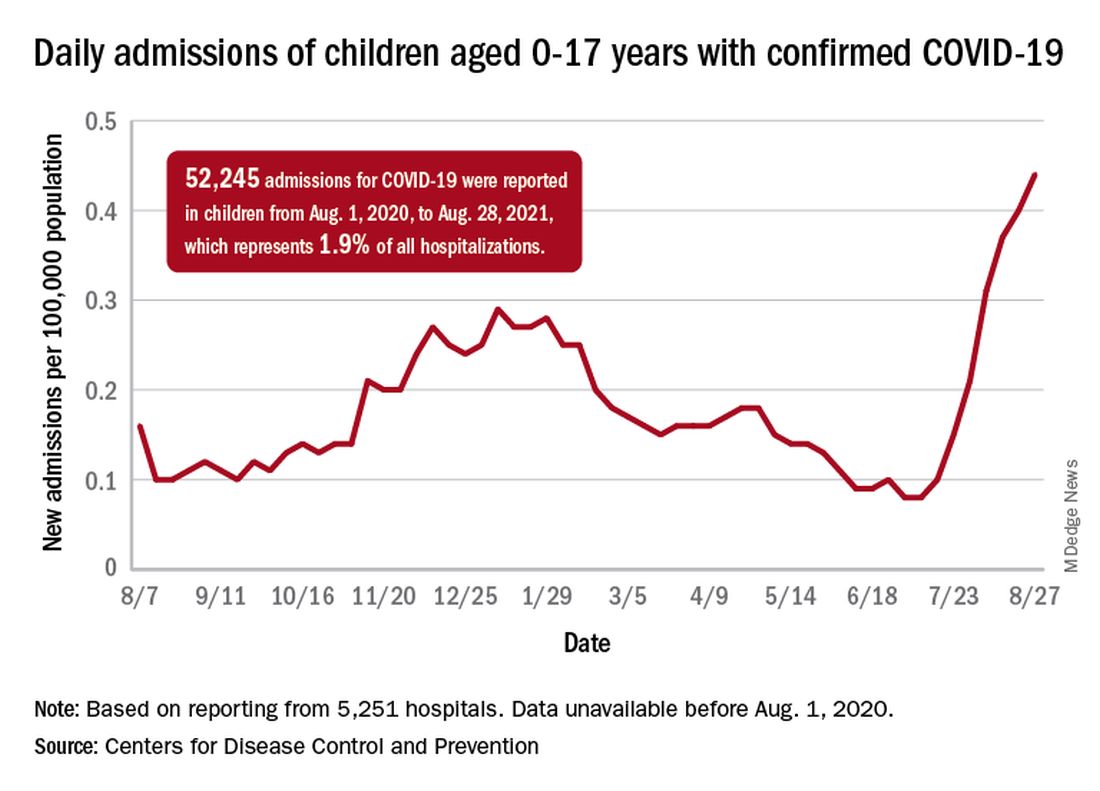

The recent rise in new child cases has been accompanied by an unprecedented increase in hospitalizations. The daily rate in children aged 0-17 years, which did not surpass 0.30 new admissions per 100,000 population during the worst of the winter surge, had risen to 0.45 per 100,000 by Aug. 26. Since July 4, when the new-admission rate was at its low point of 0.07 per 100,000, hospitalizations in children have jumped by 543%, based on data reported to the CDC by 5,251 hospitals.

A total of 52,245 children were admitted with confirmed COVID-19 from Aug. 1, 2020, when the CDC dataset begins, to Aug. 28, 2021. Those children represent 1.9% of all COVID admissions (2.7 million) in the United States over that period, the CDC said.

Total COVID-related deaths in children are up to 425 in the 48 jurisdictions (45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that provide mortality data by age, the AAP and the CHA said.

Record-high numbers for the previous 2 reporting weeks – 23 deaths during Aug. 20-26 and 24 deaths during Aug. 13-19, when the previous weekly high was 16 – at least partially reflect the recent addition of South Carolina and New Mexico to the AAP/CHA database, as the two states just started reporting age-related data.

Weekly pediatric cases of COVID-19 exceeded 200,000 for just the second time during the pandemic, while new vaccinations in children continued to decline.

The weekly count has now increased for 9 consecutive weeks, during which time it has risen by over 2,300%, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Total cases in children number almost 4.8 million since the pandemic started.

Vaccinations in children are following a different trend. Vaccine initiation has dropped 3 weeks in a row for both of the eligible age groups: First doses administered were down by 29% among 12- to 15-year-olds over that span and by 32% in 16- to 17-year-olds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since vaccination for children aged 12-15 years started in May, 49% had received at least one dose, and just over 36% were fully vaccinated as of Aug. 30. Among children aged 16-17 years, who have been eligible since December, 57.5% had gotten at least one dose of the vaccine and 46% have completed the two-dose regimen. The total number of children with at least one dose, including those under age 12 who are involved in clinical trials, was about 12 million, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Hospitalizations are higher than ever

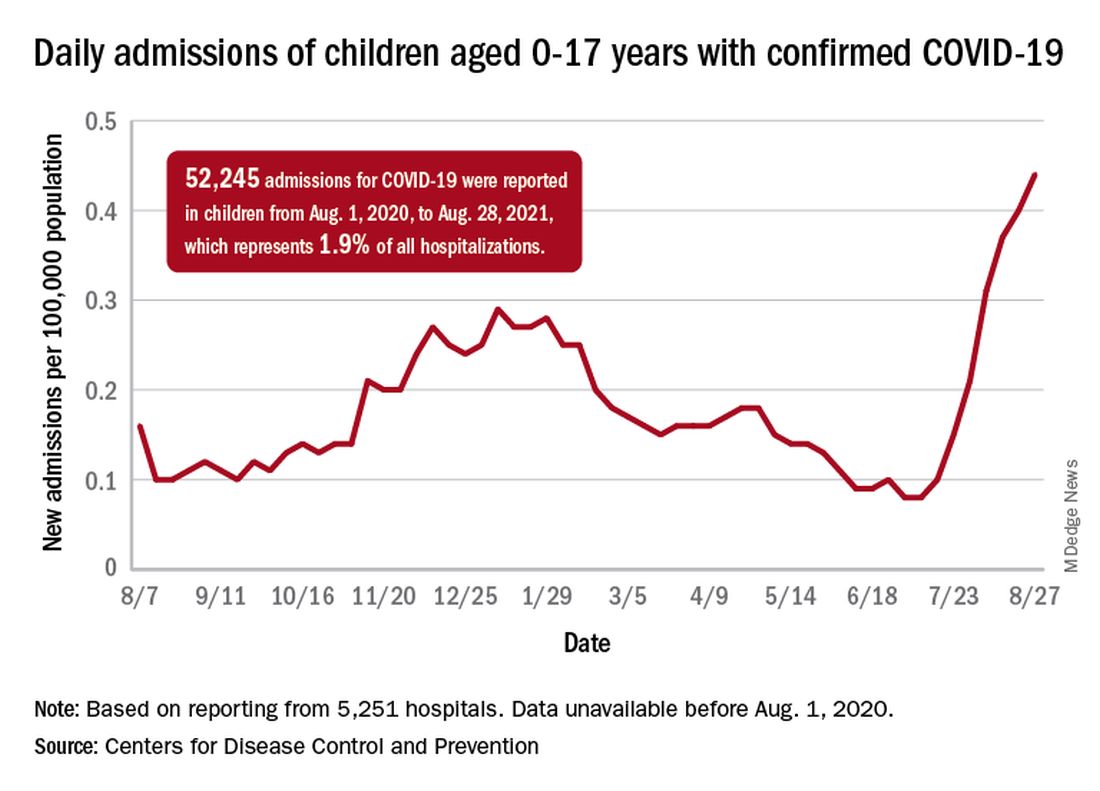

The recent rise in new child cases has been accompanied by an unprecedented increase in hospitalizations. The daily rate in children aged 0-17 years, which did not surpass 0.30 new admissions per 100,000 population during the worst of the winter surge, had risen to 0.45 per 100,000 by Aug. 26. Since July 4, when the new-admission rate was at its low point of 0.07 per 100,000, hospitalizations in children have jumped by 543%, based on data reported to the CDC by 5,251 hospitals.

A total of 52,245 children were admitted with confirmed COVID-19 from Aug. 1, 2020, when the CDC dataset begins, to Aug. 28, 2021. Those children represent 1.9% of all COVID admissions (2.7 million) in the United States over that period, the CDC said.

Total COVID-related deaths in children are up to 425 in the 48 jurisdictions (45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that provide mortality data by age, the AAP and the CHA said.

Record-high numbers for the previous 2 reporting weeks – 23 deaths during Aug. 20-26 and 24 deaths during Aug. 13-19, when the previous weekly high was 16 – at least partially reflect the recent addition of South Carolina and New Mexico to the AAP/CHA database, as the two states just started reporting age-related data.

Long COVID symptoms can persist for more than 1 year, study shows

Nearly half of people who are hospitalized with COVID-19 suffer at least one lingering symptom 1 year after discharge, according to the largest study yet to assess the dynamic recovery of a group of COVID-19 survivors 12 months after the illness.

The most common lingering symptoms are fatigue and muscle weakness. One-third continue to have shortness of breath.

Overall, at 12 months, COVID-19 survivors had more problems with mobility, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression, and had lower self-assessment scores of quality of life than matched COVID-free peers, the investigators report.

The study was published online Aug. 28 in The Lancet.

“While most had made a good recovery, health problems persisted in some patients, especially those who had been critically ill during their hospital stay,” Bin Cao, MD, from the National Center for Respiratory Medicine at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital and Capital Medical University, both in Beijing, said in a Lancet news release.

“Our findings suggest that recovery for some patients will take longer than 1 year, and this should be taken into account when planning delivery of health care services post pandemic,” Dr. Cao said.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the need to understand and respond to long COVID is increasingly pressing,” says a Lancet editorial.

“Symptoms such as persistent fatigue, breathlessness, brain fog, and depression could debilitate many millions of people globally. Long COVID is a modern medical challenge of the first order,” it reads.

Study details

Dr. Cao and colleagues studied 1,276 COVID-19 patients (median age 59; 53% men) discharged from a hospital in Wuhan, China, between Jan. 7 and May 29, 2020. The patients were assessed at 6 and 12 months from the date they first experienced COVID-19 symptoms.

Many symptoms resolved over time, regardless of the severity of illness. Yet 49% of patients still had at least one symptom 12 months after their acute illness, down from 68% at the 6-month mark, the authors report.

Fatigue and muscle weakness were the most commonly reported symptoms seen in 52% of patients at 6 months and 20% at 12 months. Compared with men, women were 1.4 times more likely to report fatigue or muscle weakness.

Patients treated with corticosteroids during the acute phase of COVID-19 were 1.5 times as likely to experience fatigue or muscle weakness after 12 months, compared with those who had not received corticosteroids.

Thirty percent of patients reported dyspnea at 12 months, slightly more than at 6 months (26%). Dyspnea was more common in the most severely ill patients needing a ventilator during their hospital stay (39%), compared with those who did not need oxygen treatment (25%).

At the 6-month check, 349 study participants underwent pulmonary function tests and 244 of those patients completed the same test at 12 months.

Spirometric and lung volume parameters of most of these patients were within normal limits at 12 months. But lung diffusion impairment was observed in about 20%-30% of patients who had been moderately ill with COVID-19 and as high as 54% in critically ill patients.

Compared with men, women were almost three times as likely to have lung diffusion impairment after 12 months.

Of 186 patients with abnormal lung CT scan at 6 months, 118 patients had a repeat CT scan at 12 months. The lung imaging abnormality gradually recovered during follow-up, yet 76% of the most critically ill patients still had ground glass opacity at 12 months.

Mental health hit

Among those patients who had been employed full- or part-time before catching COVID, the majority had returned to their original job (88%) and most had returned to their pre-COVID-19 level of work (76%) within 12 months.

Among those who did not return to their original work, 32% cited decreased physical function, 25% were unwilling to do their previous job, and 18% were unemployed.

As shown in multiple other studies, COVID-19 can take a toll on mental health. In this cohort, slightly more patients reported anxiety or depression at 12 months than at 6 months (23% vs. 26%), and the proportion was much greater than in matched community-dwelling adults without COVID-19 (5%).

Compared with men, women were twice as likely to report anxiety or depression.

“We do not yet fully understand why psychiatric symptoms are slightly more common at 1 year than at 6 months in COVID-19 survivors,” study author Xiaoying Gu, PhD, from the Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, said in the news release.

“These could be caused by a biological process linked to the virus infection itself, or the body’s immune response to it. Or they could be linked to reduced social contact, loneliness, incomplete recovery of physical health, or loss of employment associated with illness. Large, long-term studies of COVID-19 survivors are needed so that we can better understand the long-term physical and mental health consequences of COVID-19,” Dr. Gu said.

The authors caution that the findings represent a group of patients from a single hospital in China and the cohort included only a small number of patients who had been admitted to intensive care (94 of 1,276; 7.4%).

The Lancet editorial urges the scientific and medical community to “collaborate to explore the mechanism and pathogenesis of long COVID, estimate the global and regional disease burdens, better delineate who is most at risk, understand how vaccines might affect the condition, and find effective treatments via randomized controlled trials.”

“At the same time, health care providers must acknowledge and validate the toll of the persistent symptoms of long COVID on patients, and health systems need to be prepared to meet individualized, patient-oriented goals, with an appropriately trained workforce involving physical, cognitive, social, and occupational elements,” the editorial states.

“Answering these research questions while providing compassionate and multidisciplinary care will require the full breadth of scientific and medical ingenuity. It is a challenge to which the whole health community must rise,” the editorialists conclude.

The study was funded by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Major Projects of National Science and Technology on New Drug Creation and Development of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, the China Evergrande Group, the Jack Ma Foundation, Sino Biopharmaceutical, the Ping An Insurance (Group), and the New Sunshine Charity Foundation. The full list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly half of people who are hospitalized with COVID-19 suffer at least one lingering symptom 1 year after discharge, according to the largest study yet to assess the dynamic recovery of a group of COVID-19 survivors 12 months after the illness.

The most common lingering symptoms are fatigue and muscle weakness. One-third continue to have shortness of breath.

Overall, at 12 months, COVID-19 survivors had more problems with mobility, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression, and had lower self-assessment scores of quality of life than matched COVID-free peers, the investigators report.

The study was published online Aug. 28 in The Lancet.

“While most had made a good recovery, health problems persisted in some patients, especially those who had been critically ill during their hospital stay,” Bin Cao, MD, from the National Center for Respiratory Medicine at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital and Capital Medical University, both in Beijing, said in a Lancet news release.

“Our findings suggest that recovery for some patients will take longer than 1 year, and this should be taken into account when planning delivery of health care services post pandemic,” Dr. Cao said.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the need to understand and respond to long COVID is increasingly pressing,” says a Lancet editorial.

“Symptoms such as persistent fatigue, breathlessness, brain fog, and depression could debilitate many millions of people globally. Long COVID is a modern medical challenge of the first order,” it reads.

Study details

Dr. Cao and colleagues studied 1,276 COVID-19 patients (median age 59; 53% men) discharged from a hospital in Wuhan, China, between Jan. 7 and May 29, 2020. The patients were assessed at 6 and 12 months from the date they first experienced COVID-19 symptoms.

Many symptoms resolved over time, regardless of the severity of illness. Yet 49% of patients still had at least one symptom 12 months after their acute illness, down from 68% at the 6-month mark, the authors report.

Fatigue and muscle weakness were the most commonly reported symptoms seen in 52% of patients at 6 months and 20% at 12 months. Compared with men, women were 1.4 times more likely to report fatigue or muscle weakness.

Patients treated with corticosteroids during the acute phase of COVID-19 were 1.5 times as likely to experience fatigue or muscle weakness after 12 months, compared with those who had not received corticosteroids.

Thirty percent of patients reported dyspnea at 12 months, slightly more than at 6 months (26%). Dyspnea was more common in the most severely ill patients needing a ventilator during their hospital stay (39%), compared with those who did not need oxygen treatment (25%).

At the 6-month check, 349 study participants underwent pulmonary function tests and 244 of those patients completed the same test at 12 months.

Spirometric and lung volume parameters of most of these patients were within normal limits at 12 months. But lung diffusion impairment was observed in about 20%-30% of patients who had been moderately ill with COVID-19 and as high as 54% in critically ill patients.

Compared with men, women were almost three times as likely to have lung diffusion impairment after 12 months.

Of 186 patients with abnormal lung CT scan at 6 months, 118 patients had a repeat CT scan at 12 months. The lung imaging abnormality gradually recovered during follow-up, yet 76% of the most critically ill patients still had ground glass opacity at 12 months.

Mental health hit

Among those patients who had been employed full- or part-time before catching COVID, the majority had returned to their original job (88%) and most had returned to their pre-COVID-19 level of work (76%) within 12 months.

Among those who did not return to their original work, 32% cited decreased physical function, 25% were unwilling to do their previous job, and 18% were unemployed.

As shown in multiple other studies, COVID-19 can take a toll on mental health. In this cohort, slightly more patients reported anxiety or depression at 12 months than at 6 months (23% vs. 26%), and the proportion was much greater than in matched community-dwelling adults without COVID-19 (5%).

Compared with men, women were twice as likely to report anxiety or depression.

“We do not yet fully understand why psychiatric symptoms are slightly more common at 1 year than at 6 months in COVID-19 survivors,” study author Xiaoying Gu, PhD, from the Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, said in the news release.

“These could be caused by a biological process linked to the virus infection itself, or the body’s immune response to it. Or they could be linked to reduced social contact, loneliness, incomplete recovery of physical health, or loss of employment associated with illness. Large, long-term studies of COVID-19 survivors are needed so that we can better understand the long-term physical and mental health consequences of COVID-19,” Dr. Gu said.

The authors caution that the findings represent a group of patients from a single hospital in China and the cohort included only a small number of patients who had been admitted to intensive care (94 of 1,276; 7.4%).

The Lancet editorial urges the scientific and medical community to “collaborate to explore the mechanism and pathogenesis of long COVID, estimate the global and regional disease burdens, better delineate who is most at risk, understand how vaccines might affect the condition, and find effective treatments via randomized controlled trials.”

“At the same time, health care providers must acknowledge and validate the toll of the persistent symptoms of long COVID on patients, and health systems need to be prepared to meet individualized, patient-oriented goals, with an appropriately trained workforce involving physical, cognitive, social, and occupational elements,” the editorial states.

“Answering these research questions while providing compassionate and multidisciplinary care will require the full breadth of scientific and medical ingenuity. It is a challenge to which the whole health community must rise,” the editorialists conclude.

The study was funded by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Major Projects of National Science and Technology on New Drug Creation and Development of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, the China Evergrande Group, the Jack Ma Foundation, Sino Biopharmaceutical, the Ping An Insurance (Group), and the New Sunshine Charity Foundation. The full list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly half of people who are hospitalized with COVID-19 suffer at least one lingering symptom 1 year after discharge, according to the largest study yet to assess the dynamic recovery of a group of COVID-19 survivors 12 months after the illness.

The most common lingering symptoms are fatigue and muscle weakness. One-third continue to have shortness of breath.

Overall, at 12 months, COVID-19 survivors had more problems with mobility, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression, and had lower self-assessment scores of quality of life than matched COVID-free peers, the investigators report.

The study was published online Aug. 28 in The Lancet.

“While most had made a good recovery, health problems persisted in some patients, especially those who had been critically ill during their hospital stay,” Bin Cao, MD, from the National Center for Respiratory Medicine at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital and Capital Medical University, both in Beijing, said in a Lancet news release.

“Our findings suggest that recovery for some patients will take longer than 1 year, and this should be taken into account when planning delivery of health care services post pandemic,” Dr. Cao said.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the need to understand and respond to long COVID is increasingly pressing,” says a Lancet editorial.

“Symptoms such as persistent fatigue, breathlessness, brain fog, and depression could debilitate many millions of people globally. Long COVID is a modern medical challenge of the first order,” it reads.

Study details

Dr. Cao and colleagues studied 1,276 COVID-19 patients (median age 59; 53% men) discharged from a hospital in Wuhan, China, between Jan. 7 and May 29, 2020. The patients were assessed at 6 and 12 months from the date they first experienced COVID-19 symptoms.

Many symptoms resolved over time, regardless of the severity of illness. Yet 49% of patients still had at least one symptom 12 months after their acute illness, down from 68% at the 6-month mark, the authors report.

Fatigue and muscle weakness were the most commonly reported symptoms seen in 52% of patients at 6 months and 20% at 12 months. Compared with men, women were 1.4 times more likely to report fatigue or muscle weakness.

Patients treated with corticosteroids during the acute phase of COVID-19 were 1.5 times as likely to experience fatigue or muscle weakness after 12 months, compared with those who had not received corticosteroids.

Thirty percent of patients reported dyspnea at 12 months, slightly more than at 6 months (26%). Dyspnea was more common in the most severely ill patients needing a ventilator during their hospital stay (39%), compared with those who did not need oxygen treatment (25%).

At the 6-month check, 349 study participants underwent pulmonary function tests and 244 of those patients completed the same test at 12 months.

Spirometric and lung volume parameters of most of these patients were within normal limits at 12 months. But lung diffusion impairment was observed in about 20%-30% of patients who had been moderately ill with COVID-19 and as high as 54% in critically ill patients.

Compared with men, women were almost three times as likely to have lung diffusion impairment after 12 months.

Of 186 patients with abnormal lung CT scan at 6 months, 118 patients had a repeat CT scan at 12 months. The lung imaging abnormality gradually recovered during follow-up, yet 76% of the most critically ill patients still had ground glass opacity at 12 months.

Mental health hit

Among those patients who had been employed full- or part-time before catching COVID, the majority had returned to their original job (88%) and most had returned to their pre-COVID-19 level of work (76%) within 12 months.

Among those who did not return to their original work, 32% cited decreased physical function, 25% were unwilling to do their previous job, and 18% were unemployed.

As shown in multiple other studies, COVID-19 can take a toll on mental health. In this cohort, slightly more patients reported anxiety or depression at 12 months than at 6 months (23% vs. 26%), and the proportion was much greater than in matched community-dwelling adults without COVID-19 (5%).

Compared with men, women were twice as likely to report anxiety or depression.

“We do not yet fully understand why psychiatric symptoms are slightly more common at 1 year than at 6 months in COVID-19 survivors,” study author Xiaoying Gu, PhD, from the Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, said in the news release.

“These could be caused by a biological process linked to the virus infection itself, or the body’s immune response to it. Or they could be linked to reduced social contact, loneliness, incomplete recovery of physical health, or loss of employment associated with illness. Large, long-term studies of COVID-19 survivors are needed so that we can better understand the long-term physical and mental health consequences of COVID-19,” Dr. Gu said.

The authors caution that the findings represent a group of patients from a single hospital in China and the cohort included only a small number of patients who had been admitted to intensive care (94 of 1,276; 7.4%).

The Lancet editorial urges the scientific and medical community to “collaborate to explore the mechanism and pathogenesis of long COVID, estimate the global and regional disease burdens, better delineate who is most at risk, understand how vaccines might affect the condition, and find effective treatments via randomized controlled trials.”

“At the same time, health care providers must acknowledge and validate the toll of the persistent symptoms of long COVID on patients, and health systems need to be prepared to meet individualized, patient-oriented goals, with an appropriately trained workforce involving physical, cognitive, social, and occupational elements,” the editorial states.

“Answering these research questions while providing compassionate and multidisciplinary care will require the full breadth of scientific and medical ingenuity. It is a challenge to which the whole health community must rise,” the editorialists conclude.

The study was funded by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Major Projects of National Science and Technology on New Drug Creation and Development of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, the China Evergrande Group, the Jack Ma Foundation, Sino Biopharmaceutical, the Ping An Insurance (Group), and the New Sunshine Charity Foundation. The full list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC panel unanimously backs Pfizer vax, fortifying FDA approval

An independent expert panel within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has studied the potential benefits and risks of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine and voted unanimously to recommend the shots for all Americans ages 16 and older.

The vaccine was fully approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last week.

The inoculation is still available to teens ages 12 to 15 under an emergency use authorization from the FDA.

ACIP now sends its recommendation to the CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, for her sign off.

After reviewing the evidence behind the vaccine, panel member Sarah Long, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, said she couldn’t recall another instance where panelists had so much data on which to base their recommendation.

“This vaccine is worthy of the trust of the American people,” she said.

Doctors across the country use vaccines in line with the recommendations made by the ACIP. Their approval typically means that private and government insurers will cover the cost of the shots. In the case of the COVID-19 vaccines, the government is already picking up the tab.

Few surprises

The panel’s independent review of the vaccine’s effectiveness from nine studies held few surprises.

They found the Pfizer vaccine prevented a COVID infection with symptoms about 90%–92% of the time, at least for the first 4 months after the second shot. Protection against hospitalization and death was even higher.

The vaccine was about 89% effective at preventing a COVID infection without symptoms, according to a pooled estimate of five studies.

The data included in the review was updated only through March 13 of this year, however, and does not reflect the impact of further waning of immunity or the impact of the Delta variant.

In making their recommendation, the panel got an update on the safety of the vaccines, which have now been used in the United States for about 9 months.

The rate of anaphylaxis has settled at around five cases for every million shots given, according to the ACIP’s review of the evidence.

Cases of myocarditis and pericarditis were more common after getting a Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine than would be expected to happen naturally in the general population, but the risk was still very rare, and elevated primarily for men younger than age 30.

Out of 17 million second doses of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines in the United States, there have been 327 confirmed cases of myocarditis reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System in people who are younger than age 30. The average hospital stay for a myocarditis cases is 1 to 2 days.

So far, no one in the United States diagnosed with myocarditis after vaccination has died.

What’s more, the risk of myocarditis after vaccination was dwarfed by the risk of myocarditis after a COVID infection. The risk of myocarditis after a COVID infection was 6 to 34 times higher than the risk after receiving an mRNA vaccine.

About 11% of people who get the vaccine experience a serious reaction to the shot, compared with about 3% in the placebo group. Serious reactions were defined as pain; swelling or redness at the injection site that interferes with activity; needing to visit the hospital or ER for pain; tissue necrosis, or having skin slough off; high fever; vomiting that requires hydration; persistent diarrhea; severe headache; or muscle pain/severe joint pain.

“Safe and effective”

After hearing a presentation on the state of the pandemic in the US, some panel members were struck and shaken that 38% of Americans who are eligible are still not fully vaccinated.

Pablo Sanchez, MD, a pediatrician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, said, “We’re doing an abysmal job vaccinating the American people. The message has to go out that the vaccines are safe and effective.”

A version of this story first appeared on Medscape.com.

An independent expert panel within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has studied the potential benefits and risks of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine and voted unanimously to recommend the shots for all Americans ages 16 and older.

The vaccine was fully approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last week.

The inoculation is still available to teens ages 12 to 15 under an emergency use authorization from the FDA.

ACIP now sends its recommendation to the CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, for her sign off.

After reviewing the evidence behind the vaccine, panel member Sarah Long, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, said she couldn’t recall another instance where panelists had so much data on which to base their recommendation.

“This vaccine is worthy of the trust of the American people,” she said.

Doctors across the country use vaccines in line with the recommendations made by the ACIP. Their approval typically means that private and government insurers will cover the cost of the shots. In the case of the COVID-19 vaccines, the government is already picking up the tab.

Few surprises

The panel’s independent review of the vaccine’s effectiveness from nine studies held few surprises.

They found the Pfizer vaccine prevented a COVID infection with symptoms about 90%–92% of the time, at least for the first 4 months after the second shot. Protection against hospitalization and death was even higher.

The vaccine was about 89% effective at preventing a COVID infection without symptoms, according to a pooled estimate of five studies.

The data included in the review was updated only through March 13 of this year, however, and does not reflect the impact of further waning of immunity or the impact of the Delta variant.

In making their recommendation, the panel got an update on the safety of the vaccines, which have now been used in the United States for about 9 months.

The rate of anaphylaxis has settled at around five cases for every million shots given, according to the ACIP’s review of the evidence.

Cases of myocarditis and pericarditis were more common after getting a Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine than would be expected to happen naturally in the general population, but the risk was still very rare, and elevated primarily for men younger than age 30.

Out of 17 million second doses of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines in the United States, there have been 327 confirmed cases of myocarditis reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System in people who are younger than age 30. The average hospital stay for a myocarditis cases is 1 to 2 days.

So far, no one in the United States diagnosed with myocarditis after vaccination has died.

What’s more, the risk of myocarditis after vaccination was dwarfed by the risk of myocarditis after a COVID infection. The risk of myocarditis after a COVID infection was 6 to 34 times higher than the risk after receiving an mRNA vaccine.

About 11% of people who get the vaccine experience a serious reaction to the shot, compared with about 3% in the placebo group. Serious reactions were defined as pain; swelling or redness at the injection site that interferes with activity; needing to visit the hospital or ER for pain; tissue necrosis, or having skin slough off; high fever; vomiting that requires hydration; persistent diarrhea; severe headache; or muscle pain/severe joint pain.

“Safe and effective”

After hearing a presentation on the state of the pandemic in the US, some panel members were struck and shaken that 38% of Americans who are eligible are still not fully vaccinated.

Pablo Sanchez, MD, a pediatrician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, said, “We’re doing an abysmal job vaccinating the American people. The message has to go out that the vaccines are safe and effective.”

A version of this story first appeared on Medscape.com.

An independent expert panel within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has studied the potential benefits and risks of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine and voted unanimously to recommend the shots for all Americans ages 16 and older.

The vaccine was fully approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last week.

The inoculation is still available to teens ages 12 to 15 under an emergency use authorization from the FDA.

ACIP now sends its recommendation to the CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, for her sign off.

After reviewing the evidence behind the vaccine, panel member Sarah Long, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, said she couldn’t recall another instance where panelists had so much data on which to base their recommendation.

“This vaccine is worthy of the trust of the American people,” she said.

Doctors across the country use vaccines in line with the recommendations made by the ACIP. Their approval typically means that private and government insurers will cover the cost of the shots. In the case of the COVID-19 vaccines, the government is already picking up the tab.

Few surprises

The panel’s independent review of the vaccine’s effectiveness from nine studies held few surprises.

They found the Pfizer vaccine prevented a COVID infection with symptoms about 90%–92% of the time, at least for the first 4 months after the second shot. Protection against hospitalization and death was even higher.

The vaccine was about 89% effective at preventing a COVID infection without symptoms, according to a pooled estimate of five studies.

The data included in the review was updated only through March 13 of this year, however, and does not reflect the impact of further waning of immunity or the impact of the Delta variant.

In making their recommendation, the panel got an update on the safety of the vaccines, which have now been used in the United States for about 9 months.

The rate of anaphylaxis has settled at around five cases for every million shots given, according to the ACIP’s review of the evidence.

Cases of myocarditis and pericarditis were more common after getting a Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine than would be expected to happen naturally in the general population, but the risk was still very rare, and elevated primarily for men younger than age 30.

Out of 17 million second doses of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines in the United States, there have been 327 confirmed cases of myocarditis reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System in people who are younger than age 30. The average hospital stay for a myocarditis cases is 1 to 2 days.

So far, no one in the United States diagnosed with myocarditis after vaccination has died.

What’s more, the risk of myocarditis after vaccination was dwarfed by the risk of myocarditis after a COVID infection. The risk of myocarditis after a COVID infection was 6 to 34 times higher than the risk after receiving an mRNA vaccine.

About 11% of people who get the vaccine experience a serious reaction to the shot, compared with about 3% in the placebo group. Serious reactions were defined as pain; swelling or redness at the injection site that interferes with activity; needing to visit the hospital or ER for pain; tissue necrosis, or having skin slough off; high fever; vomiting that requires hydration; persistent diarrhea; severe headache; or muscle pain/severe joint pain.

“Safe and effective”

After hearing a presentation on the state of the pandemic in the US, some panel members were struck and shaken that 38% of Americans who are eligible are still not fully vaccinated.

Pablo Sanchez, MD, a pediatrician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, said, “We’re doing an abysmal job vaccinating the American people. The message has to go out that the vaccines are safe and effective.”

A version of this story first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children’s upper airways primed to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection

Epithelial and immune cells of the upper airways of children are preactivated and primed to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may contribute to stronger early immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection than adults, new research suggests.

The findings may help to explain why children have a lower risk of developing severe COVID-19 illness or becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the first place, the researchers say.

The study was published online Aug. 18 in Nature Biotechnology.

Primed for action

Children appear to be better able than adults to control SARS-CoV-2 infection, but, until now, the exact molecular mechanisms have been unclear.

A team of investigators from Germany did an in-depth analysis of nasal swab samples obtained from 24 children and 21 adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, as well as a control group of 18 children and 23 adults who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

“We wanted to understand why viral defense appears to work so much better in children than in adults,” Irina Lehmann, PhD, head of the molecular epidemiology unit at the Berlin Institute of Health Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, explained in a news release.

Single-cell sequencing showed that children had higher baseline levels of certain RNA-sensing receptors that are relevant to SARS-CoV-2 detection, such as MDA5 and RIG-I, in the epithelial and immune cells of their noses.

This differential expression led to stronger early immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children than in adults.

Children were also more likely than adults to have distinct immune cell subpopulations, including KLRC1+ cytotoxic T cells, involved in fighting infection, and memory CD8+ T cells, associated with the development of long-lasting immunity.

‘Clear evidence’

The study provides “clear evidence” that upper-airway immune cells of children are “primed for virus sensing, resulting in a stronger early innate antiviral response to SARS-CoV-2 infection than in adults,” the investigators say.

Primed virus sensing and a preactivated innate immune response in children leads to efficient early production of interferons (IFNs) in the infected airways, likely mediating substantial antiviral effects, they note.

Ultimately, this may lead to lower viral replication and faster clearance in children. In fact, several studies have already shown that children eliminate the virus more quickly than adults, consistent with the concept that they shut down viral replication earlier, the study team says.

Weighing in on the findings for this news organization, John Wherry, PhD, director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said this “interesting study highlights potential differences in innate immunity and possibly geographic immunity in the upper respiratory tract in children versus adults.”

“We know there are differences in innate immunity over a lifespan, but exactly how these differences might relate to viral infection remains unclear,” said Dr. Wherry, who was not involved in the study.

“Children, of course, often have more respiratory infections than adults [but] whether this is due to exposure [i.e., daycare, schools, etc.] or susceptibility [lack of accumulated adaptive immunity over a greater number of years of exposure] is unclear,” Dr. Wherry noted.

“These data may help reveal what kinds of innate immune responses in the upper respiratory tract might help restrain SARS-CoV-2 and [perhaps partially] explain why children typically have milder COVID-19 disease,” he added.

The study was supported by the Berlin Institute of Health COVID-19 research program and fightCOVID@DKFZ initiative, European Commission, German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), and German Research Foundation. Dr. Lehmann and Dr. Wherry have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Epithelial and immune cells of the upper airways of children are preactivated and primed to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may contribute to stronger early immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection than adults, new research suggests.

The findings may help to explain why children have a lower risk of developing severe COVID-19 illness or becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the first place, the researchers say.

The study was published online Aug. 18 in Nature Biotechnology.

Primed for action

Children appear to be better able than adults to control SARS-CoV-2 infection, but, until now, the exact molecular mechanisms have been unclear.

A team of investigators from Germany did an in-depth analysis of nasal swab samples obtained from 24 children and 21 adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, as well as a control group of 18 children and 23 adults who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

“We wanted to understand why viral defense appears to work so much better in children than in adults,” Irina Lehmann, PhD, head of the molecular epidemiology unit at the Berlin Institute of Health Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, explained in a news release.

Single-cell sequencing showed that children had higher baseline levels of certain RNA-sensing receptors that are relevant to SARS-CoV-2 detection, such as MDA5 and RIG-I, in the epithelial and immune cells of their noses.

This differential expression led to stronger early immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children than in adults.

Children were also more likely than adults to have distinct immune cell subpopulations, including KLRC1+ cytotoxic T cells, involved in fighting infection, and memory CD8+ T cells, associated with the development of long-lasting immunity.

‘Clear evidence’

The study provides “clear evidence” that upper-airway immune cells of children are “primed for virus sensing, resulting in a stronger early innate antiviral response to SARS-CoV-2 infection than in adults,” the investigators say.

Primed virus sensing and a preactivated innate immune response in children leads to efficient early production of interferons (IFNs) in the infected airways, likely mediating substantial antiviral effects, they note.

Ultimately, this may lead to lower viral replication and faster clearance in children. In fact, several studies have already shown that children eliminate the virus more quickly than adults, consistent with the concept that they shut down viral replication earlier, the study team says.

Weighing in on the findings for this news organization, John Wherry, PhD, director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said this “interesting study highlights potential differences in innate immunity and possibly geographic immunity in the upper respiratory tract in children versus adults.”

“We know there are differences in innate immunity over a lifespan, but exactly how these differences might relate to viral infection remains unclear,” said Dr. Wherry, who was not involved in the study.

“Children, of course, often have more respiratory infections than adults [but] whether this is due to exposure [i.e., daycare, schools, etc.] or susceptibility [lack of accumulated adaptive immunity over a greater number of years of exposure] is unclear,” Dr. Wherry noted.

“These data may help reveal what kinds of innate immune responses in the upper respiratory tract might help restrain SARS-CoV-2 and [perhaps partially] explain why children typically have milder COVID-19 disease,” he added.

The study was supported by the Berlin Institute of Health COVID-19 research program and fightCOVID@DKFZ initiative, European Commission, German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), and German Research Foundation. Dr. Lehmann and Dr. Wherry have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Epithelial and immune cells of the upper airways of children are preactivated and primed to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may contribute to stronger early immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection than adults, new research suggests.

The findings may help to explain why children have a lower risk of developing severe COVID-19 illness or becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the first place, the researchers say.

The study was published online Aug. 18 in Nature Biotechnology.

Primed for action

Children appear to be better able than adults to control SARS-CoV-2 infection, but, until now, the exact molecular mechanisms have been unclear.

A team of investigators from Germany did an in-depth analysis of nasal swab samples obtained from 24 children and 21 adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, as well as a control group of 18 children and 23 adults who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

“We wanted to understand why viral defense appears to work so much better in children than in adults,” Irina Lehmann, PhD, head of the molecular epidemiology unit at the Berlin Institute of Health Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, explained in a news release.

Single-cell sequencing showed that children had higher baseline levels of certain RNA-sensing receptors that are relevant to SARS-CoV-2 detection, such as MDA5 and RIG-I, in the epithelial and immune cells of their noses.

This differential expression led to stronger early immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children than in adults.

Children were also more likely than adults to have distinct immune cell subpopulations, including KLRC1+ cytotoxic T cells, involved in fighting infection, and memory CD8+ T cells, associated with the development of long-lasting immunity.

‘Clear evidence’

The study provides “clear evidence” that upper-airway immune cells of children are “primed for virus sensing, resulting in a stronger early innate antiviral response to SARS-CoV-2 infection than in adults,” the investigators say.

Primed virus sensing and a preactivated innate immune response in children leads to efficient early production of interferons (IFNs) in the infected airways, likely mediating substantial antiviral effects, they note.

Ultimately, this may lead to lower viral replication and faster clearance in children. In fact, several studies have already shown that children eliminate the virus more quickly than adults, consistent with the concept that they shut down viral replication earlier, the study team says.

Weighing in on the findings for this news organization, John Wherry, PhD, director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said this “interesting study highlights potential differences in innate immunity and possibly geographic immunity in the upper respiratory tract in children versus adults.”

“We know there are differences in innate immunity over a lifespan, but exactly how these differences might relate to viral infection remains unclear,” said Dr. Wherry, who was not involved in the study.

“Children, of course, often have more respiratory infections than adults [but] whether this is due to exposure [i.e., daycare, schools, etc.] or susceptibility [lack of accumulated adaptive immunity over a greater number of years of exposure] is unclear,” Dr. Wherry noted.

“These data may help reveal what kinds of innate immune responses in the upper respiratory tract might help restrain SARS-CoV-2 and [perhaps partially] explain why children typically have milder COVID-19 disease,” he added.

The study was supported by the Berlin Institute of Health COVID-19 research program and fightCOVID@DKFZ initiative, European Commission, German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), and German Research Foundation. Dr. Lehmann and Dr. Wherry have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antidepressant helps prevent hospitalization in COVID patients: Study

A handful of studies have suggested that for newly infected COVID-19 patients, risk for serious illness may be reduced with a short course of fluvoxamine (Luvox), a decades-old pill typically prescribed for depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). But those were small studies involving just a few hundred people.

This week, researchers reported promising data from a large, randomized phase 3 trial that enrolled COVID-19 patients from 11 sites in Brazil. In this study, in which 1,472 people were assigned to receive either a 10-day course of fluvoxamine or placebo pills, the antidepressant cut emergency department and hospital admissions by 29%.

Findings from the new study, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published August 23 in MedRxiv.

Around the globe, particularly in countries without access to vaccines, “treatment options that are cheap and available and supported by good-quality evidence are the only hope we’ve got to reduce mortality within high-risk populations,” said Edward Mills, PhD, professor in the department of health research methods, evidence, and impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The new findings came from TOGETHER, a large platform trial coordinated by Dr. Mills and colleagues to evaluate the use of fluvoxamine and other repurposed drug candidates for symptomatic, high-risk, adult outpatients with confirmed cases of COVID-19.

The trial’s adaptive format allows multiple agents to be added and tested alongside placebo in a single master protocol – similar to the United Kingdom’s Recovery trial, which found that the common steroid dexamethasone could reduce deaths among hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

In platform trials, treatment arms can be dropped for futility, as was the case with hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir-ritonavir, neither of which did better than placebo at preventing hospitalization in an earlier TOGETHER trial analysis.

Study details

In the newly reported analysis, patients were randomly assigned to receive fluvoxamine or placebo between January and August 2021. Participants took fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily for 10 days. By comparison, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends a maximum daily dose of 300 mg of fluvoxamine for patients with OCD; full psychiatric benefits occur after 6 weeks.