User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

CDC endorses Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for young kids

– meaning the shots are now available for immediate use.

The Nov. 2 decision came mere hours after experts that advise the CDC on vaccinations strongly recommended the vaccine for this age group.

“Together, with science leading the charge, we have taken another important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus that causes COVID-19. We know millions of parents are eager to get their children vaccinated and with this decision, we now have recommended that about 28 million children receive a COVID-19 vaccine. As a mom, I encourage parents with questions to talk to their pediatrician, school nurse, or local pharmacist to learn more about the vaccine and the importance of getting their children vaccinated,” Dr. Walensky said in a prepared statement.

President Joe Biden applauded Dr. Walensky’s endorsement: “Today, we have reached a turning point in our battle against COVID-19: authorization of a safe, effective vaccine for children age 5 to 11. It will allow parents to end months of anxious worrying about their kids, and reduce the extent to which children spread the virus to others. It is a major step forward for our nation in our fight to defeat the virus,” he said in a statement.

The 14 members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted unanimously earlier in the day to recommend the vaccine for kids.

“I feel like I have a responsibility to make this vaccine available to children and their parents,” said committee member Beth Bell, MD, MPH, a clinical professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. Bell noted that all evidence the committee had reviewed pointed to a vaccine that was safe and effective for younger children.

“If I had a grandchild, I would certainly get that grandchild vaccinated as soon as possible,” she said.

Their recommendations follow the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency authorization of Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine for this same age group last week.

“I’m voting for this because I think it could have a huge positive impact on [kids’] health and their social and emotional wellbeing,” said Grace Lee, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine, who chairs the CDC’s ACIP.

She noted that, though masks are available to reduce the risk for kids, they aren’t perfect and transmission still occurs.

“Vaccines are really the only consistent and reliable way to provide that protection,” Lee said.

The vaccine for children is two doses given 3 weeks apart. Each dose is 10 micrograms, which is one-third of the dose used in adults and teens.

To avoid confusion, the smaller dose for kids will come in bottles with orange labels and orange tops. The vaccine for adults is packaged in purple.

The CDC also addressed the question of kids who are close to age 12 when they get their first dose.

In general, pediatricians allow for a 4-day grace period around birthdays to determine which dose is needed. That will be the same with the COVID-19 vaccine.

For kids who are 11 when they start the series, they should get another 10-microgram dose after they turn 12 a few weeks later.

COVID-19 cases in this age group have climbed sharply over the summer and into the fall as schools have fully reopened, sometimes without the benefit of masks.

In the first week of October, roughly 10% of all COVID-19 cases recorded in the United States were among children ages 5 through 11. Since the start of pandemic, about 1.9 million children in this age group have been infected, though that’s almost certainly an undercount. More than 8,300 have been hospitalized, and 94 children have died.

Children of color have been disproportionately impacted. More than two-thirds of hospitalized children have been black or Hispanic.

Weighing benefits and risks

In clinical trials that included more than 4,600 children, the most common adverse events were pain and swelling at the injection site. They could also have side effects like fevers, fatigue, headache, chills, and sometimes swollen lymph nodes.

These kinds of side effects appear to be less common in children ages 5 to 11 than they have been in teens and adults, and they were temporary.

No cases of myocarditis or pericarditis were seen in the studies, but myocarditis is a very rare side effect, and the studies were too small to pick up these cases.

Still, doctors say they’re watching for it. In general, the greatest risk for myocarditis after vaccination has been seen in younger males between the ages of 12 and 30.

Even without COVID-19 or vaccines in the mix, doctors expect to see as many as two cases of myocarditis for every million people over the course of a week. The risk for myocarditis jumps up to about 11 cases for every million doses of mRNA vaccine given to men ages 25 to 30. It’s between 37 and 69 cases per million doses in boys between the ages of 12 and 24.

Still, experts say the possibility of this rare risk shouldn’t deter parents from vaccinating younger children.

Here’s why: The risk for myocarditis is higher after COVID-19 infection than after vaccination. Younger children have a lower risk for myocarditis than teens and young adults, suggesting that this side effect may be less frequent in this age group, although that remains to be seen.

Additionally, the smaller dose authorized for children is expected to minimize the risk for myocarditis even further.

The CDC says parents should call their doctor if a child develops pain in their chest, has trouble breathing, or feels like they have a beating or fluttering heart after vaccination.

What about benefits?

Models looking at the impact of vaccines in this age group predict that, nationally, cases would drop by about 8% if children are vaccinated.

The models also suggested that vaccination of kids this age would slow — but not stop — the emergence of new variants.

For every million doses, the CDC’s modeling predicts that more than 56,000 COVID-19 infections would be prevented in this age group, along with dozens of hospitalizations, and post-COVID conditions like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

CDC experts estimate that just 10 kids would need to be vaccinated over 6 months to prevent a single case of COVID-19.

The CDC pointed out that vaccinating kids may help slow transmission of the virus and would give parents and other caregivers greater confidence in participating in school and extracurricular activities.

CDC experts said they would use a variety of systems, including hospital networks, the open Vaccines and Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) database, the cell-phone based V-SAFE app, and insurance claims databases to keep an eye out for any rare adverse events related to the vaccines in children.

This article, a version of which first appeared on Medscape.com, was updated on Nov. 3, 2021.

– meaning the shots are now available for immediate use.

The Nov. 2 decision came mere hours after experts that advise the CDC on vaccinations strongly recommended the vaccine for this age group.

“Together, with science leading the charge, we have taken another important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus that causes COVID-19. We know millions of parents are eager to get their children vaccinated and with this decision, we now have recommended that about 28 million children receive a COVID-19 vaccine. As a mom, I encourage parents with questions to talk to their pediatrician, school nurse, or local pharmacist to learn more about the vaccine and the importance of getting their children vaccinated,” Dr. Walensky said in a prepared statement.

President Joe Biden applauded Dr. Walensky’s endorsement: “Today, we have reached a turning point in our battle against COVID-19: authorization of a safe, effective vaccine for children age 5 to 11. It will allow parents to end months of anxious worrying about their kids, and reduce the extent to which children spread the virus to others. It is a major step forward for our nation in our fight to defeat the virus,” he said in a statement.

The 14 members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted unanimously earlier in the day to recommend the vaccine for kids.

“I feel like I have a responsibility to make this vaccine available to children and their parents,” said committee member Beth Bell, MD, MPH, a clinical professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. Bell noted that all evidence the committee had reviewed pointed to a vaccine that was safe and effective for younger children.

“If I had a grandchild, I would certainly get that grandchild vaccinated as soon as possible,” she said.

Their recommendations follow the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency authorization of Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine for this same age group last week.

“I’m voting for this because I think it could have a huge positive impact on [kids’] health and their social and emotional wellbeing,” said Grace Lee, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine, who chairs the CDC’s ACIP.

She noted that, though masks are available to reduce the risk for kids, they aren’t perfect and transmission still occurs.

“Vaccines are really the only consistent and reliable way to provide that protection,” Lee said.

The vaccine for children is two doses given 3 weeks apart. Each dose is 10 micrograms, which is one-third of the dose used in adults and teens.

To avoid confusion, the smaller dose for kids will come in bottles with orange labels and orange tops. The vaccine for adults is packaged in purple.

The CDC also addressed the question of kids who are close to age 12 when they get their first dose.

In general, pediatricians allow for a 4-day grace period around birthdays to determine which dose is needed. That will be the same with the COVID-19 vaccine.

For kids who are 11 when they start the series, they should get another 10-microgram dose after they turn 12 a few weeks later.

COVID-19 cases in this age group have climbed sharply over the summer and into the fall as schools have fully reopened, sometimes without the benefit of masks.

In the first week of October, roughly 10% of all COVID-19 cases recorded in the United States were among children ages 5 through 11. Since the start of pandemic, about 1.9 million children in this age group have been infected, though that’s almost certainly an undercount. More than 8,300 have been hospitalized, and 94 children have died.

Children of color have been disproportionately impacted. More than two-thirds of hospitalized children have been black or Hispanic.

Weighing benefits and risks

In clinical trials that included more than 4,600 children, the most common adverse events were pain and swelling at the injection site. They could also have side effects like fevers, fatigue, headache, chills, and sometimes swollen lymph nodes.

These kinds of side effects appear to be less common in children ages 5 to 11 than they have been in teens and adults, and they were temporary.

No cases of myocarditis or pericarditis were seen in the studies, but myocarditis is a very rare side effect, and the studies were too small to pick up these cases.

Still, doctors say they’re watching for it. In general, the greatest risk for myocarditis after vaccination has been seen in younger males between the ages of 12 and 30.

Even without COVID-19 or vaccines in the mix, doctors expect to see as many as two cases of myocarditis for every million people over the course of a week. The risk for myocarditis jumps up to about 11 cases for every million doses of mRNA vaccine given to men ages 25 to 30. It’s between 37 and 69 cases per million doses in boys between the ages of 12 and 24.

Still, experts say the possibility of this rare risk shouldn’t deter parents from vaccinating younger children.

Here’s why: The risk for myocarditis is higher after COVID-19 infection than after vaccination. Younger children have a lower risk for myocarditis than teens and young adults, suggesting that this side effect may be less frequent in this age group, although that remains to be seen.

Additionally, the smaller dose authorized for children is expected to minimize the risk for myocarditis even further.

The CDC says parents should call their doctor if a child develops pain in their chest, has trouble breathing, or feels like they have a beating or fluttering heart after vaccination.

What about benefits?

Models looking at the impact of vaccines in this age group predict that, nationally, cases would drop by about 8% if children are vaccinated.

The models also suggested that vaccination of kids this age would slow — but not stop — the emergence of new variants.

For every million doses, the CDC’s modeling predicts that more than 56,000 COVID-19 infections would be prevented in this age group, along with dozens of hospitalizations, and post-COVID conditions like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

CDC experts estimate that just 10 kids would need to be vaccinated over 6 months to prevent a single case of COVID-19.

The CDC pointed out that vaccinating kids may help slow transmission of the virus and would give parents and other caregivers greater confidence in participating in school and extracurricular activities.

CDC experts said they would use a variety of systems, including hospital networks, the open Vaccines and Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) database, the cell-phone based V-SAFE app, and insurance claims databases to keep an eye out for any rare adverse events related to the vaccines in children.

This article, a version of which first appeared on Medscape.com, was updated on Nov. 3, 2021.

– meaning the shots are now available for immediate use.

The Nov. 2 decision came mere hours after experts that advise the CDC on vaccinations strongly recommended the vaccine for this age group.

“Together, with science leading the charge, we have taken another important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus that causes COVID-19. We know millions of parents are eager to get their children vaccinated and with this decision, we now have recommended that about 28 million children receive a COVID-19 vaccine. As a mom, I encourage parents with questions to talk to their pediatrician, school nurse, or local pharmacist to learn more about the vaccine and the importance of getting their children vaccinated,” Dr. Walensky said in a prepared statement.

President Joe Biden applauded Dr. Walensky’s endorsement: “Today, we have reached a turning point in our battle against COVID-19: authorization of a safe, effective vaccine for children age 5 to 11. It will allow parents to end months of anxious worrying about their kids, and reduce the extent to which children spread the virus to others. It is a major step forward for our nation in our fight to defeat the virus,” he said in a statement.

The 14 members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted unanimously earlier in the day to recommend the vaccine for kids.

“I feel like I have a responsibility to make this vaccine available to children and their parents,” said committee member Beth Bell, MD, MPH, a clinical professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. Bell noted that all evidence the committee had reviewed pointed to a vaccine that was safe and effective for younger children.

“If I had a grandchild, I would certainly get that grandchild vaccinated as soon as possible,” she said.

Their recommendations follow the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency authorization of Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine for this same age group last week.

“I’m voting for this because I think it could have a huge positive impact on [kids’] health and their social and emotional wellbeing,” said Grace Lee, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine, who chairs the CDC’s ACIP.

She noted that, though masks are available to reduce the risk for kids, they aren’t perfect and transmission still occurs.

“Vaccines are really the only consistent and reliable way to provide that protection,” Lee said.

The vaccine for children is two doses given 3 weeks apart. Each dose is 10 micrograms, which is one-third of the dose used in adults and teens.

To avoid confusion, the smaller dose for kids will come in bottles with orange labels and orange tops. The vaccine for adults is packaged in purple.

The CDC also addressed the question of kids who are close to age 12 when they get their first dose.

In general, pediatricians allow for a 4-day grace period around birthdays to determine which dose is needed. That will be the same with the COVID-19 vaccine.

For kids who are 11 when they start the series, they should get another 10-microgram dose after they turn 12 a few weeks later.

COVID-19 cases in this age group have climbed sharply over the summer and into the fall as schools have fully reopened, sometimes without the benefit of masks.

In the first week of October, roughly 10% of all COVID-19 cases recorded in the United States were among children ages 5 through 11. Since the start of pandemic, about 1.9 million children in this age group have been infected, though that’s almost certainly an undercount. More than 8,300 have been hospitalized, and 94 children have died.

Children of color have been disproportionately impacted. More than two-thirds of hospitalized children have been black or Hispanic.

Weighing benefits and risks

In clinical trials that included more than 4,600 children, the most common adverse events were pain and swelling at the injection site. They could also have side effects like fevers, fatigue, headache, chills, and sometimes swollen lymph nodes.

These kinds of side effects appear to be less common in children ages 5 to 11 than they have been in teens and adults, and they were temporary.

No cases of myocarditis or pericarditis were seen in the studies, but myocarditis is a very rare side effect, and the studies were too small to pick up these cases.

Still, doctors say they’re watching for it. In general, the greatest risk for myocarditis after vaccination has been seen in younger males between the ages of 12 and 30.

Even without COVID-19 or vaccines in the mix, doctors expect to see as many as two cases of myocarditis for every million people over the course of a week. The risk for myocarditis jumps up to about 11 cases for every million doses of mRNA vaccine given to men ages 25 to 30. It’s between 37 and 69 cases per million doses in boys between the ages of 12 and 24.

Still, experts say the possibility of this rare risk shouldn’t deter parents from vaccinating younger children.

Here’s why: The risk for myocarditis is higher after COVID-19 infection than after vaccination. Younger children have a lower risk for myocarditis than teens and young adults, suggesting that this side effect may be less frequent in this age group, although that remains to be seen.

Additionally, the smaller dose authorized for children is expected to minimize the risk for myocarditis even further.

The CDC says parents should call their doctor if a child develops pain in their chest, has trouble breathing, or feels like they have a beating or fluttering heart after vaccination.

What about benefits?

Models looking at the impact of vaccines in this age group predict that, nationally, cases would drop by about 8% if children are vaccinated.

The models also suggested that vaccination of kids this age would slow — but not stop — the emergence of new variants.

For every million doses, the CDC’s modeling predicts that more than 56,000 COVID-19 infections would be prevented in this age group, along with dozens of hospitalizations, and post-COVID conditions like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

CDC experts estimate that just 10 kids would need to be vaccinated over 6 months to prevent a single case of COVID-19.

The CDC pointed out that vaccinating kids may help slow transmission of the virus and would give parents and other caregivers greater confidence in participating in school and extracurricular activities.

CDC experts said they would use a variety of systems, including hospital networks, the open Vaccines and Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) database, the cell-phone based V-SAFE app, and insurance claims databases to keep an eye out for any rare adverse events related to the vaccines in children.

This article, a version of which first appeared on Medscape.com, was updated on Nov. 3, 2021.

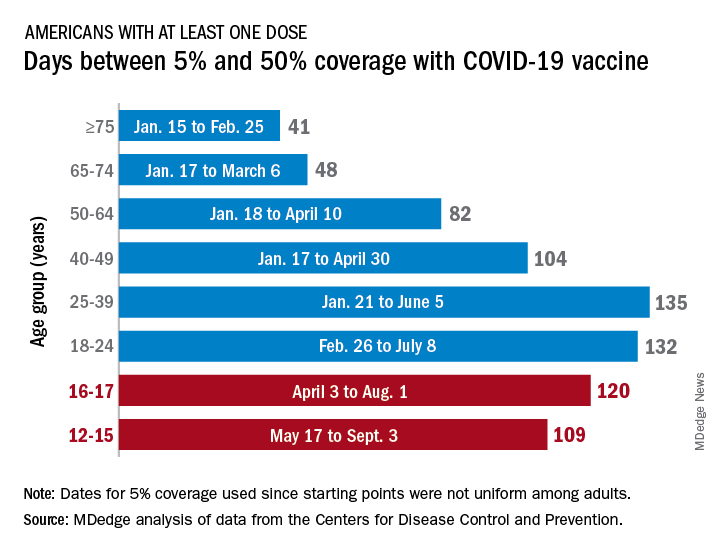

Children and COVID: A look at the pace of vaccination

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

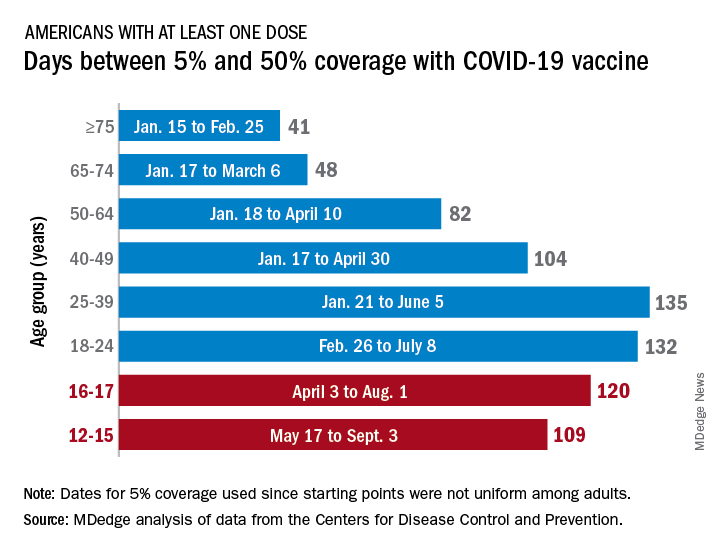

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

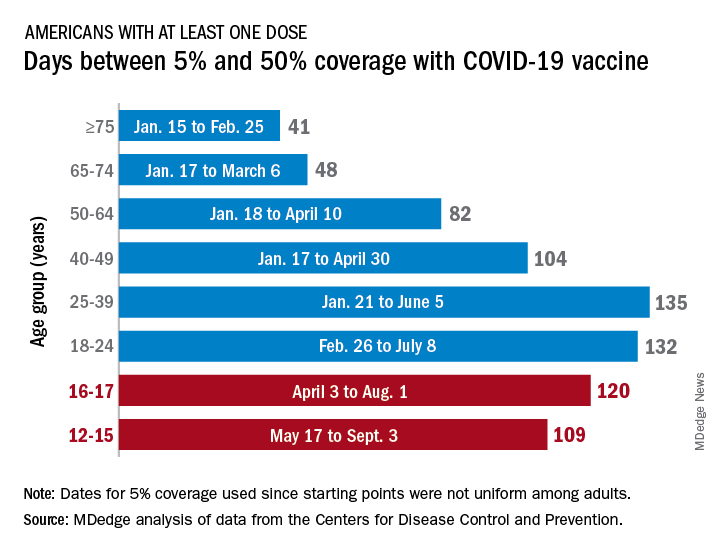

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

ASNC rejects new chest pain guideline it helped create

It was Oct. 28 when the two big North American cardiology societies issued a joint practice guideline on evaluating and managing chest pain that was endorsed by five other subspecialty groups. The next day, another group that had taken part in the document’s genesis explained why it wasn’t one of those five.

Although the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) was “actively engaged at every stage of the guideline-writing and review process,” the society “could not endorse the guideline,” the society announced in a statement released to clinicians and the media. The most prominent cited reason: It doesn’t adequately “support the principle of Patient First Imaging.”

The guideline was published in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, flagship journals of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, respectively.

The document notes at least two clinicians represented ASNC as peer reviewers, and another was on the writing committee, but the organization does not appear in the list of societies endorsing the document.

“We believe that the document fails to provide unbiased guidance to health care professionals on the optimal evaluation of patients with chest pain,” contends an editorial ASNC board members have scheduled for the Jan. 10 issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine but is available now on an open-access preprint server.

“Despite the many important and helpful recommendations in the new guideline, there are several recommendations that we could not support,” it states.

“The ASNC board of directors reviewed the document twice during the endorsement process,” and the society “offered substantive comments after the first endorsement review, several of which were addressed,” Randall C. Thompson, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City, said in an interview.

“However, some of the board’s concerns went unresolved. It was after the board’s second review, when the document had been declared finalized, that they voted not to endorse,” said Dr. Thompson, who is ASNC president.

“When we gather multiple organizations together to review and summarize the evidence, we work collaboratively to interpret the extensive catalog of peer-reviewed, published literature and create clinical practice recommendations,” Guideline Writing Committee Chair Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization in a prepared statement.

“The ASNC had a representative on the writing committee who is a coauthor on the paper and actively participated throughout the writing process the past 4 years,” she said. “The final guideline reflects the latest evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain, as agreed by the seven endorsing organizations.”

The document does not clearly note that an ASNC representative was on the writing committee. However, ASNC confirmed that Renee Bullock-Palmer, MD, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, N.J., is a fellow of the ASNC and had represented the group as one of the coauthors. Two “official reviewers” of the document, however, are listed as ASNC representatives.

Points of contention

“The decision about which test to order can be a nuanced one, and cardiac imaging tests tend to be complementary,” elaborates the editorial on the issue of patient-centered management.

Careful patient selection for different tests is important, “and physician and technical local expertise, availability, quality of equipment, and patient preference are extremely important factors to consider. There is not enough emphasis on this important point,” contend the authors. “This is an important limitation of the guideline.”

Other issues of concern include “lack of balance in the document’s presentation of the science on FFR-CT [fractional flow reserve assessment with computed tomography] and its inappropriately prominent endorsement,” the editorial states.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration–recognized “limitations and contraindications” to FFR-CT tend to be glossed over in the document, Dr. Thompson said. And most ASNC board members were “concerned with the prominent location of the recommendations for FFR-CT in various tables – especially since there was minimal-to-no discussion of the fact that it is currently provided by only one company, that it is not widely available nor covered routinely by health insurance carriers, and [that] the accuracy in the most relevant population is disputed.”

In other concerns, the document “inadequately discusses the benefit” of combining coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores with functional testing, which ASNC said it supports. For example, adding CAC scores to myocardial perfusion imaging improves its diagnostic accuracy and prognostic power.

Functional vs. anatomic testing?

Moreover, “it is no longer appropriate to bundle all types of stress testing together. All stress imaging tests have their unique advantages and limitations.” Yet, “the concept of the dichotomy of functional testing versus anatomic testing is a common theme in the guideline in many important patient groups,” the editorial states. That could overemphasize CT angiography and thus “blur distinction between different types of functional tests.”

Such concerns about “imbalance” in the portrayals of the two kinds of tests were “amplified by the problem of health insurance companies and radiologic benefits managers inappropriately substituting a test that was ordered by a physician with a different test,” Dr. Thompson elaborated. “There is the impression that some of them ‘cherry-pick’ certain guidelines and that this practice is harmful to patients.”

The ASNC currently does not plan its own corresponding guideline, he said. But the editorial says that “over the coming weeks and months ASNC will offer a series of webinars and other programs that address specific patient populations and dilemmas.” Also, “we will enhance our focus on programs to address quality and efficiency to support a patient-first approach to imaging.”

The five subspecialty groups that have endorsed the document are the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

Dr. Thompson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Statements of disclosure for the other editorial writers are listed in the publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was Oct. 28 when the two big North American cardiology societies issued a joint practice guideline on evaluating and managing chest pain that was endorsed by five other subspecialty groups. The next day, another group that had taken part in the document’s genesis explained why it wasn’t one of those five.

Although the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) was “actively engaged at every stage of the guideline-writing and review process,” the society “could not endorse the guideline,” the society announced in a statement released to clinicians and the media. The most prominent cited reason: It doesn’t adequately “support the principle of Patient First Imaging.”

The guideline was published in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, flagship journals of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, respectively.

The document notes at least two clinicians represented ASNC as peer reviewers, and another was on the writing committee, but the organization does not appear in the list of societies endorsing the document.

“We believe that the document fails to provide unbiased guidance to health care professionals on the optimal evaluation of patients with chest pain,” contends an editorial ASNC board members have scheduled for the Jan. 10 issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine but is available now on an open-access preprint server.

“Despite the many important and helpful recommendations in the new guideline, there are several recommendations that we could not support,” it states.

“The ASNC board of directors reviewed the document twice during the endorsement process,” and the society “offered substantive comments after the first endorsement review, several of which were addressed,” Randall C. Thompson, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City, said in an interview.

“However, some of the board’s concerns went unresolved. It was after the board’s second review, when the document had been declared finalized, that they voted not to endorse,” said Dr. Thompson, who is ASNC president.

“When we gather multiple organizations together to review and summarize the evidence, we work collaboratively to interpret the extensive catalog of peer-reviewed, published literature and create clinical practice recommendations,” Guideline Writing Committee Chair Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization in a prepared statement.

“The ASNC had a representative on the writing committee who is a coauthor on the paper and actively participated throughout the writing process the past 4 years,” she said. “The final guideline reflects the latest evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain, as agreed by the seven endorsing organizations.”

The document does not clearly note that an ASNC representative was on the writing committee. However, ASNC confirmed that Renee Bullock-Palmer, MD, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, N.J., is a fellow of the ASNC and had represented the group as one of the coauthors. Two “official reviewers” of the document, however, are listed as ASNC representatives.

Points of contention

“The decision about which test to order can be a nuanced one, and cardiac imaging tests tend to be complementary,” elaborates the editorial on the issue of patient-centered management.

Careful patient selection for different tests is important, “and physician and technical local expertise, availability, quality of equipment, and patient preference are extremely important factors to consider. There is not enough emphasis on this important point,” contend the authors. “This is an important limitation of the guideline.”

Other issues of concern include “lack of balance in the document’s presentation of the science on FFR-CT [fractional flow reserve assessment with computed tomography] and its inappropriately prominent endorsement,” the editorial states.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration–recognized “limitations and contraindications” to FFR-CT tend to be glossed over in the document, Dr. Thompson said. And most ASNC board members were “concerned with the prominent location of the recommendations for FFR-CT in various tables – especially since there was minimal-to-no discussion of the fact that it is currently provided by only one company, that it is not widely available nor covered routinely by health insurance carriers, and [that] the accuracy in the most relevant population is disputed.”

In other concerns, the document “inadequately discusses the benefit” of combining coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores with functional testing, which ASNC said it supports. For example, adding CAC scores to myocardial perfusion imaging improves its diagnostic accuracy and prognostic power.

Functional vs. anatomic testing?

Moreover, “it is no longer appropriate to bundle all types of stress testing together. All stress imaging tests have their unique advantages and limitations.” Yet, “the concept of the dichotomy of functional testing versus anatomic testing is a common theme in the guideline in many important patient groups,” the editorial states. That could overemphasize CT angiography and thus “blur distinction between different types of functional tests.”

Such concerns about “imbalance” in the portrayals of the two kinds of tests were “amplified by the problem of health insurance companies and radiologic benefits managers inappropriately substituting a test that was ordered by a physician with a different test,” Dr. Thompson elaborated. “There is the impression that some of them ‘cherry-pick’ certain guidelines and that this practice is harmful to patients.”

The ASNC currently does not plan its own corresponding guideline, he said. But the editorial says that “over the coming weeks and months ASNC will offer a series of webinars and other programs that address specific patient populations and dilemmas.” Also, “we will enhance our focus on programs to address quality and efficiency to support a patient-first approach to imaging.”

The five subspecialty groups that have endorsed the document are the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

Dr. Thompson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Statements of disclosure for the other editorial writers are listed in the publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was Oct. 28 when the two big North American cardiology societies issued a joint practice guideline on evaluating and managing chest pain that was endorsed by five other subspecialty groups. The next day, another group that had taken part in the document’s genesis explained why it wasn’t one of those five.

Although the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) was “actively engaged at every stage of the guideline-writing and review process,” the society “could not endorse the guideline,” the society announced in a statement released to clinicians and the media. The most prominent cited reason: It doesn’t adequately “support the principle of Patient First Imaging.”

The guideline was published in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, flagship journals of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, respectively.

The document notes at least two clinicians represented ASNC as peer reviewers, and another was on the writing committee, but the organization does not appear in the list of societies endorsing the document.

“We believe that the document fails to provide unbiased guidance to health care professionals on the optimal evaluation of patients with chest pain,” contends an editorial ASNC board members have scheduled for the Jan. 10 issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine but is available now on an open-access preprint server.

“Despite the many important and helpful recommendations in the new guideline, there are several recommendations that we could not support,” it states.

“The ASNC board of directors reviewed the document twice during the endorsement process,” and the society “offered substantive comments after the first endorsement review, several of which were addressed,” Randall C. Thompson, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City, said in an interview.

“However, some of the board’s concerns went unresolved. It was after the board’s second review, when the document had been declared finalized, that they voted not to endorse,” said Dr. Thompson, who is ASNC president.

“When we gather multiple organizations together to review and summarize the evidence, we work collaboratively to interpret the extensive catalog of peer-reviewed, published literature and create clinical practice recommendations,” Guideline Writing Committee Chair Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization in a prepared statement.

“The ASNC had a representative on the writing committee who is a coauthor on the paper and actively participated throughout the writing process the past 4 years,” she said. “The final guideline reflects the latest evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain, as agreed by the seven endorsing organizations.”

The document does not clearly note that an ASNC representative was on the writing committee. However, ASNC confirmed that Renee Bullock-Palmer, MD, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, N.J., is a fellow of the ASNC and had represented the group as one of the coauthors. Two “official reviewers” of the document, however, are listed as ASNC representatives.

Points of contention

“The decision about which test to order can be a nuanced one, and cardiac imaging tests tend to be complementary,” elaborates the editorial on the issue of patient-centered management.

Careful patient selection for different tests is important, “and physician and technical local expertise, availability, quality of equipment, and patient preference are extremely important factors to consider. There is not enough emphasis on this important point,” contend the authors. “This is an important limitation of the guideline.”

Other issues of concern include “lack of balance in the document’s presentation of the science on FFR-CT [fractional flow reserve assessment with computed tomography] and its inappropriately prominent endorsement,” the editorial states.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration–recognized “limitations and contraindications” to FFR-CT tend to be glossed over in the document, Dr. Thompson said. And most ASNC board members were “concerned with the prominent location of the recommendations for FFR-CT in various tables – especially since there was minimal-to-no discussion of the fact that it is currently provided by only one company, that it is not widely available nor covered routinely by health insurance carriers, and [that] the accuracy in the most relevant population is disputed.”

In other concerns, the document “inadequately discusses the benefit” of combining coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores with functional testing, which ASNC said it supports. For example, adding CAC scores to myocardial perfusion imaging improves its diagnostic accuracy and prognostic power.

Functional vs. anatomic testing?

Moreover, “it is no longer appropriate to bundle all types of stress testing together. All stress imaging tests have their unique advantages and limitations.” Yet, “the concept of the dichotomy of functional testing versus anatomic testing is a common theme in the guideline in many important patient groups,” the editorial states. That could overemphasize CT angiography and thus “blur distinction between different types of functional tests.”

Such concerns about “imbalance” in the portrayals of the two kinds of tests were “amplified by the problem of health insurance companies and radiologic benefits managers inappropriately substituting a test that was ordered by a physician with a different test,” Dr. Thompson elaborated. “There is the impression that some of them ‘cherry-pick’ certain guidelines and that this practice is harmful to patients.”

The ASNC currently does not plan its own corresponding guideline, he said. But the editorial says that “over the coming weeks and months ASNC will offer a series of webinars and other programs that address specific patient populations and dilemmas.” Also, “we will enhance our focus on programs to address quality and efficiency to support a patient-first approach to imaging.”

The five subspecialty groups that have endorsed the document are the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

Dr. Thompson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Statements of disclosure for the other editorial writers are listed in the publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccines provide 5 times the protection of natural immunity, CDC study says

, according to a new study published recently in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The research team concluded that vaccination can provide a higher, stronger, and more consistent level of immunity against COVID-19 hospitalization than infection alone for at least six months.

“We now have additional evidence that reaffirms the importance of COVID-19 vaccines, even if you have had prior infection,” Rochelle Walensky, MD, director of the CDC, said in a statement.

“This study adds more to the body of knowledge demonstrating the protection of vaccines against severe disease from COVID-19,” she said. “The best way to stop COVID-19, including the emergence of variants, is with widespread COVID-19 vaccination and with disease prevention actions such as mask wearing, washing hands often, physical distancing and staying home when sick.”

Researchers looked at data from the VISION Network, which included more than 201,000 hospitalizations for COVID-like illness at 187 hospitals across nine states between Jan. 1 to Sept. 2. Among those, more than 94,000 had rapid testing for the coronavirus, and 7,300 had a lab-confirmed test for COVID-19.

The research team found that unvaccinated people with a prior infection within 3 to 6 months were about 5-1/2 times more likely to have laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 than those who were fully vaccinated within 3 to 6 months with the Pfizer or Moderna shots. They found similar results when looking at the months that the Delta variant was the dominant strain of the coronavirus.

Protection from the Moderna vaccine “appeared to be higher” than for the Pfizer vaccine, the study authors wrote. The boost in protection also “trended higher” among older adults, as compared to those under age 65.

Importantly, the research team noted, these estimates may change over time as immunity wanes. Future studies should consider infection-induced and vaccine-induced immunity as time passes during the pandemic, they wrote.

Additional research is also needed for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, they wrote. Those who have received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are currently recommended to receive a booster shot at least two months after the first shot.

Overall, “all eligible persons should be vaccinated against COVID-19 as soon as possible, including unvaccinated persons previously infected,” the research team concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new study published recently in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The research team concluded that vaccination can provide a higher, stronger, and more consistent level of immunity against COVID-19 hospitalization than infection alone for at least six months.

“We now have additional evidence that reaffirms the importance of COVID-19 vaccines, even if you have had prior infection,” Rochelle Walensky, MD, director of the CDC, said in a statement.

“This study adds more to the body of knowledge demonstrating the protection of vaccines against severe disease from COVID-19,” she said. “The best way to stop COVID-19, including the emergence of variants, is with widespread COVID-19 vaccination and with disease prevention actions such as mask wearing, washing hands often, physical distancing and staying home when sick.”

Researchers looked at data from the VISION Network, which included more than 201,000 hospitalizations for COVID-like illness at 187 hospitals across nine states between Jan. 1 to Sept. 2. Among those, more than 94,000 had rapid testing for the coronavirus, and 7,300 had a lab-confirmed test for COVID-19.

The research team found that unvaccinated people with a prior infection within 3 to 6 months were about 5-1/2 times more likely to have laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 than those who were fully vaccinated within 3 to 6 months with the Pfizer or Moderna shots. They found similar results when looking at the months that the Delta variant was the dominant strain of the coronavirus.

Protection from the Moderna vaccine “appeared to be higher” than for the Pfizer vaccine, the study authors wrote. The boost in protection also “trended higher” among older adults, as compared to those under age 65.

Importantly, the research team noted, these estimates may change over time as immunity wanes. Future studies should consider infection-induced and vaccine-induced immunity as time passes during the pandemic, they wrote.

Additional research is also needed for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, they wrote. Those who have received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are currently recommended to receive a booster shot at least two months after the first shot.

Overall, “all eligible persons should be vaccinated against COVID-19 as soon as possible, including unvaccinated persons previously infected,” the research team concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new study published recently in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The research team concluded that vaccination can provide a higher, stronger, and more consistent level of immunity against COVID-19 hospitalization than infection alone for at least six months.

“We now have additional evidence that reaffirms the importance of COVID-19 vaccines, even if you have had prior infection,” Rochelle Walensky, MD, director of the CDC, said in a statement.

“This study adds more to the body of knowledge demonstrating the protection of vaccines against severe disease from COVID-19,” she said. “The best way to stop COVID-19, including the emergence of variants, is with widespread COVID-19 vaccination and with disease prevention actions such as mask wearing, washing hands often, physical distancing and staying home when sick.”

Researchers looked at data from the VISION Network, which included more than 201,000 hospitalizations for COVID-like illness at 187 hospitals across nine states between Jan. 1 to Sept. 2. Among those, more than 94,000 had rapid testing for the coronavirus, and 7,300 had a lab-confirmed test for COVID-19.

The research team found that unvaccinated people with a prior infection within 3 to 6 months were about 5-1/2 times more likely to have laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 than those who were fully vaccinated within 3 to 6 months with the Pfizer or Moderna shots. They found similar results when looking at the months that the Delta variant was the dominant strain of the coronavirus.

Protection from the Moderna vaccine “appeared to be higher” than for the Pfizer vaccine, the study authors wrote. The boost in protection also “trended higher” among older adults, as compared to those under age 65.

Importantly, the research team noted, these estimates may change over time as immunity wanes. Future studies should consider infection-induced and vaccine-induced immunity as time passes during the pandemic, they wrote.

Additional research is also needed for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, they wrote. Those who have received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are currently recommended to receive a booster shot at least two months after the first shot.

Overall, “all eligible persons should be vaccinated against COVID-19 as soon as possible, including unvaccinated persons previously infected,” the research team concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Influenza tied to long-term increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ERs are swamped with seriously ill patients, although many don’t have COVID