User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Pig heart transplants and the ethical challenges that lie ahead

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

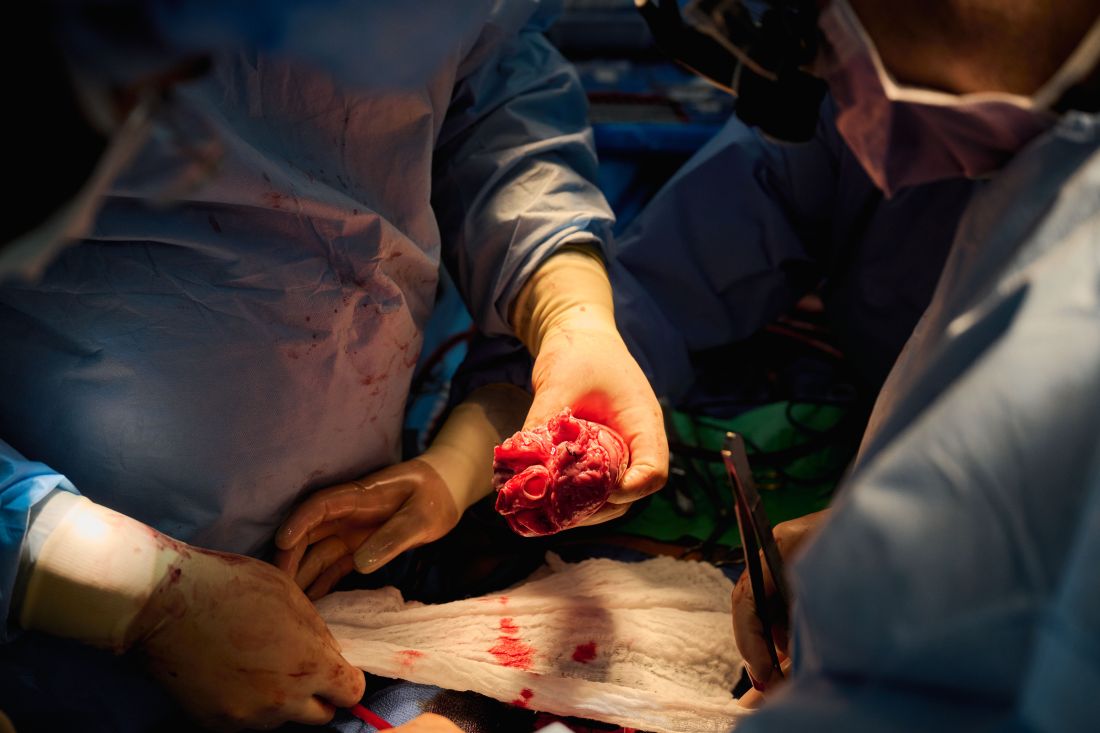

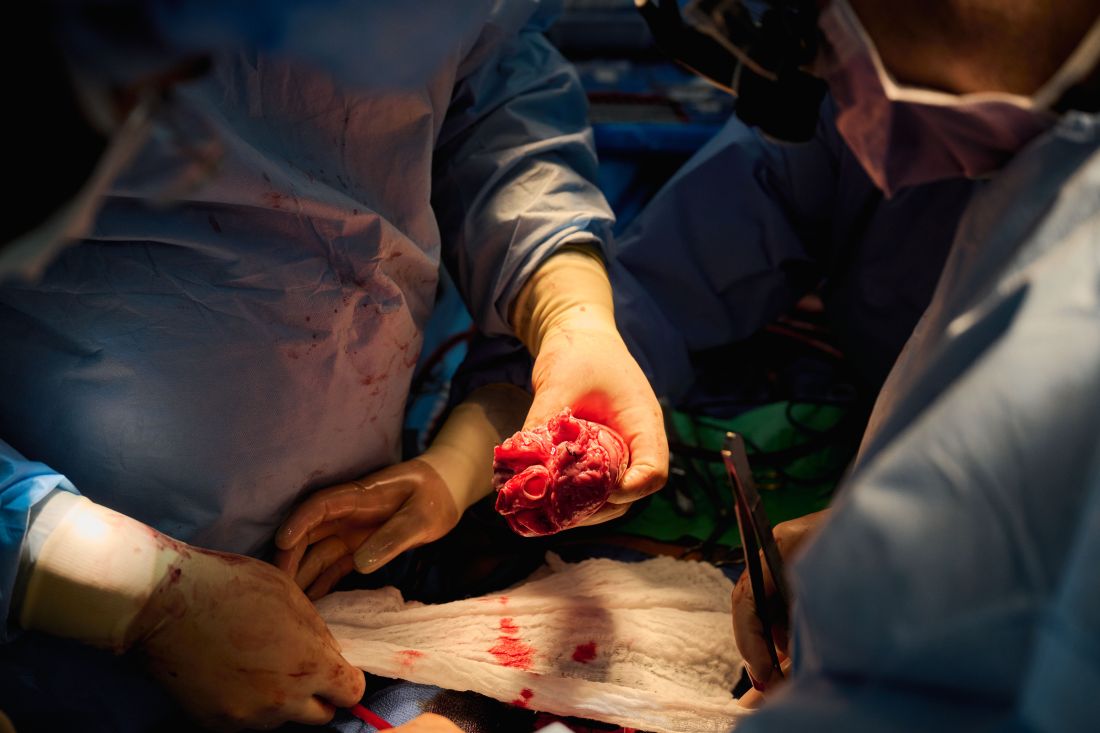

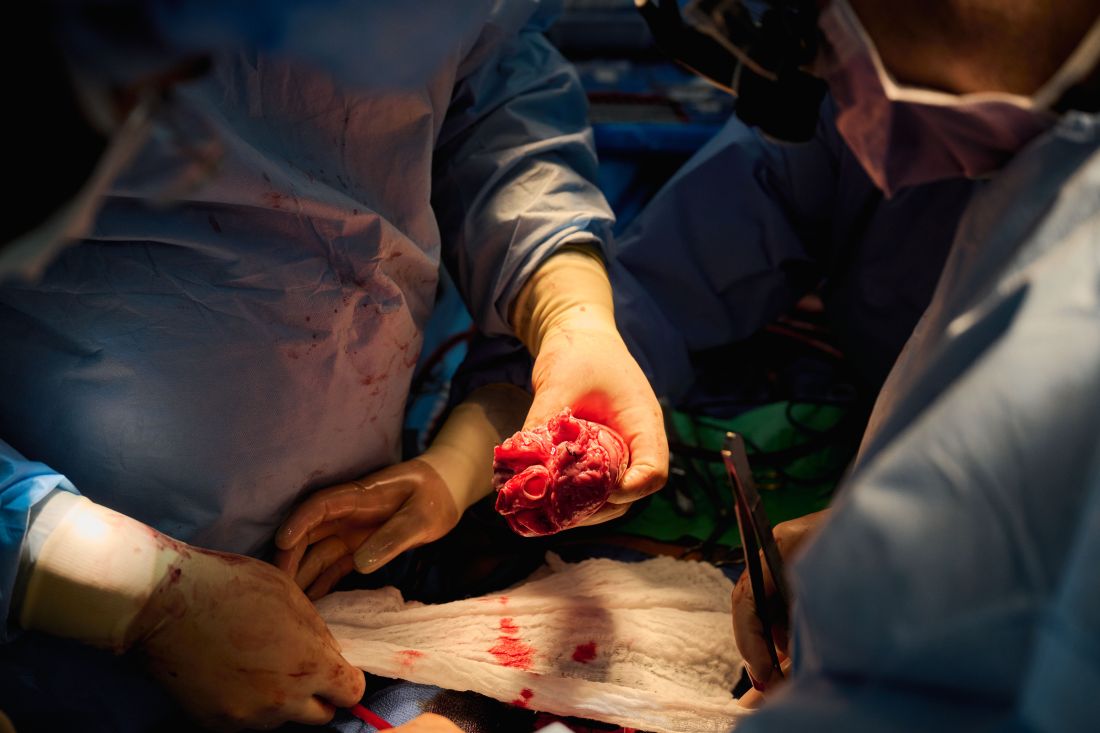

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lung cancer treatment combo may be effective after ICI failure

In a phase 2 clinical trial, the combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor led to improved overall survival versus standard of care in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had failed previous ICI therapy.

NSCLC patients usually receive immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy at some point, whether in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, or among stage 3 patients after radiation. “The majority of patients who get diagnosed with lung cancer will get some sort of immunotherapy, and we know that at least from the advanced setting, about 15% of those will have long-term responses, which means the majority of patients will develop tumor resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” said Karen L. Reckamp, MD, who is the lead author of the study published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

That clinical need has led to the combination of ICIs with VEGF inhibitors. This approach is approved for first-line therapy of renal cell cancer, endometrial, and hepatocellular cancer. Along with its effect on tumor vasculature, VEGF inhibition assists in the activation and maturation of dendritic cells, as well as to attract cytotoxic T cells to the tumor. “By both changing the vasculature and changing the tumor milieu, there’s a potential to overcome that immune suppression and potentially overcome that (ICI) resistance,” said Dr. Reckamp, who is associate director of clinical research at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “The results of the study were encouraging. . We would like to confirm this finding in a phase 3 trial and potentially provide to patients an option that does not include chemotherapy and can potentially overcome resistance to their prior immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study included 136 patients. The median patient age was 66 years and 61% were male. The ICI/VEGF arm had better overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.69; SLR one-sided P = .05). The median overall survival was 14.5 months in the ICI/VEGF arm, versus 11.6 months in the standard care arm. Both arms had similar response rates, and grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were more common in the chemotherapy arm (60% versus 42%).

The next step is a phase 3 trial and Dr. Reckamp hopes to improve patient selection for VEGF inhibitor and VEGF receptor inhibitor therapy. “The precision medicine that’s associated with other tumor alterations has kind of been elusive for VEGF therapies, but I would hope with potentially a larger trial and understanding of some of the biomarkers that we might find a more select patient population who will benefit the most,” Dr. Reckamp said.

She also noted that the comparative arm in the phase 2 study was a combination of docetaxel and ramucirumab. “That combination has shown to be more effective than single agent docetaxel alone so [the new study] was really improved overall survival over the best standard of care therapy we have,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study was funded, in part, by Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Dr. Reckamp disclosed ties to Amgen, Tesaro, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, EMD Serono, Janssen Oncology, Merck KGaA, GlaxoSmithKline, and Mirati Therapeutics.

In a phase 2 clinical trial, the combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor led to improved overall survival versus standard of care in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had failed previous ICI therapy.

NSCLC patients usually receive immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy at some point, whether in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, or among stage 3 patients after radiation. “The majority of patients who get diagnosed with lung cancer will get some sort of immunotherapy, and we know that at least from the advanced setting, about 15% of those will have long-term responses, which means the majority of patients will develop tumor resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” said Karen L. Reckamp, MD, who is the lead author of the study published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

That clinical need has led to the combination of ICIs with VEGF inhibitors. This approach is approved for first-line therapy of renal cell cancer, endometrial, and hepatocellular cancer. Along with its effect on tumor vasculature, VEGF inhibition assists in the activation and maturation of dendritic cells, as well as to attract cytotoxic T cells to the tumor. “By both changing the vasculature and changing the tumor milieu, there’s a potential to overcome that immune suppression and potentially overcome that (ICI) resistance,” said Dr. Reckamp, who is associate director of clinical research at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “The results of the study were encouraging. . We would like to confirm this finding in a phase 3 trial and potentially provide to patients an option that does not include chemotherapy and can potentially overcome resistance to their prior immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study included 136 patients. The median patient age was 66 years and 61% were male. The ICI/VEGF arm had better overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.69; SLR one-sided P = .05). The median overall survival was 14.5 months in the ICI/VEGF arm, versus 11.6 months in the standard care arm. Both arms had similar response rates, and grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were more common in the chemotherapy arm (60% versus 42%).

The next step is a phase 3 trial and Dr. Reckamp hopes to improve patient selection for VEGF inhibitor and VEGF receptor inhibitor therapy. “The precision medicine that’s associated with other tumor alterations has kind of been elusive for VEGF therapies, but I would hope with potentially a larger trial and understanding of some of the biomarkers that we might find a more select patient population who will benefit the most,” Dr. Reckamp said.

She also noted that the comparative arm in the phase 2 study was a combination of docetaxel and ramucirumab. “That combination has shown to be more effective than single agent docetaxel alone so [the new study] was really improved overall survival over the best standard of care therapy we have,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study was funded, in part, by Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Dr. Reckamp disclosed ties to Amgen, Tesaro, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, EMD Serono, Janssen Oncology, Merck KGaA, GlaxoSmithKline, and Mirati Therapeutics.

In a phase 2 clinical trial, the combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor led to improved overall survival versus standard of care in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had failed previous ICI therapy.

NSCLC patients usually receive immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy at some point, whether in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, or among stage 3 patients after radiation. “The majority of patients who get diagnosed with lung cancer will get some sort of immunotherapy, and we know that at least from the advanced setting, about 15% of those will have long-term responses, which means the majority of patients will develop tumor resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” said Karen L. Reckamp, MD, who is the lead author of the study published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

That clinical need has led to the combination of ICIs with VEGF inhibitors. This approach is approved for first-line therapy of renal cell cancer, endometrial, and hepatocellular cancer. Along with its effect on tumor vasculature, VEGF inhibition assists in the activation and maturation of dendritic cells, as well as to attract cytotoxic T cells to the tumor. “By both changing the vasculature and changing the tumor milieu, there’s a potential to overcome that immune suppression and potentially overcome that (ICI) resistance,” said Dr. Reckamp, who is associate director of clinical research at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “The results of the study were encouraging. . We would like to confirm this finding in a phase 3 trial and potentially provide to patients an option that does not include chemotherapy and can potentially overcome resistance to their prior immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study included 136 patients. The median patient age was 66 years and 61% were male. The ICI/VEGF arm had better overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.69; SLR one-sided P = .05). The median overall survival was 14.5 months in the ICI/VEGF arm, versus 11.6 months in the standard care arm. Both arms had similar response rates, and grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were more common in the chemotherapy arm (60% versus 42%).

The next step is a phase 3 trial and Dr. Reckamp hopes to improve patient selection for VEGF inhibitor and VEGF receptor inhibitor therapy. “The precision medicine that’s associated with other tumor alterations has kind of been elusive for VEGF therapies, but I would hope with potentially a larger trial and understanding of some of the biomarkers that we might find a more select patient population who will benefit the most,” Dr. Reckamp said.

She also noted that the comparative arm in the phase 2 study was a combination of docetaxel and ramucirumab. “That combination has shown to be more effective than single agent docetaxel alone so [the new study] was really improved overall survival over the best standard of care therapy we have,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study was funded, in part, by Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Dr. Reckamp disclosed ties to Amgen, Tesaro, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, EMD Serono, Janssen Oncology, Merck KGaA, GlaxoSmithKline, and Mirati Therapeutics.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Does your patient have long COVID? Some clues on what to look for

New Yorker Lyss Stern came down with COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic, in March 2020. She ran a 103° F fever for 5 days straight and was bedridden for several weeks. Yet symptoms such as a persistent headache and tinnitus, or ringing in her ears, lingered.

“Four months later, I still couldn’t walk four blocks without becoming winded,” says Ms. Stern, 48. Five months after her diagnosis, her doctors finally gave a name to her condition: long COVID.

Long COVID is known by many different names: long-haul COVID, postacute COVID-19, or even chronic COVID. It’s a general term used to describe the range of ongoing health problems people can have after their infection.

Another earlier report found that one in five COVID-19 survivors between the ages of 18 and 64, and one in four survivors aged at least 65, have a health condition that may be related to their previous bout with the virus.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to screen for long COVID.

“There’s no definite laboratory test to give us a diagnosis,” says Daniel Sterman, MD, director of the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York. “We’re also still working on a definition, since there’s a whole slew of symptoms associated with the condition.”

It’s a challenge that Ms. Stern is personally acquainted with after she bounced from doctor to doctor for several months before she found her way to the Center for Post-COVID Care at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. “It was a relief to have an official diagnosis, even if it didn’t bring immediate answers,” she says.

What to look for

Many people who become infected with COVID-19 get symptoms that linger for 2-3 weeks after their infection has cleared, says Brittany Baloun, a certified nurse practitioner at the Cleveland Clinic. “It’s not unusual to feel some residual shortness of breath or heart palpitations, especially if you are exerting yourself,” she says. “The acute phase of COVID itself can last for up to 14 days. But if it’s been 30 days since you came down with the virus, and your symptoms are still there and not improving, it indicates some level of long COVID.”

More than 200 symptoms can be linked to long COVID. But perhaps the one that stands out the most is constant fatigue that interferes with daily life.

“We often hear that these patients can’t fold the laundry or take a short walk with their dog without feeling exhausted,” Ms. Baloun says.

This exhaustion may get worse after patients exercise or do something mentally taxing, a condition known as postexertional malaise.

“It can be crushing fatigue; I may clean my room for an hour and talk to a friend, and the next day feel like I can’t get out of bed,” says Allison Guy, 36, who was diagnosed with COVID in February 2021. She’s now a long-COVID advocate in Washington.

Other symptoms can be divided into different categories, which include cardiac/lung symptoms such as shortness of breath, coughing, chest pain, and heart palpitations, as well as neurologic symptoms.

One of the most common neurologic symptoms is brain fog, says Andrew Schamess, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, who runs its post-COVID recovery program. “Patients describe feeling ‘fuzzy’ or ‘spacey,’ and often report that they are forgetful or have memory problems,” he says. Others include:

- Headache.

- Sleep problems. One 2022 study from the Cleveland Clinic found that more than 40% of patients with long COVID reported sleep disturbances.

- Dizziness when standing.

- Pins-and-needles feelings.

- Changes in smell or taste.

- Depression or anxiety.

You could also have digestive symptoms such as diarrhea or stomach pain. Other symptoms include joint or muscle pain, rashes, or changes in menstrual cycles.

Risk of having other health conditions

People who have had COVID-19, particularly a severe case, may be more at risk of getting other health conditions, such as:

- Type 2 diabetes.

- Kidney failure.

- Pulmonary embolism, or a blood clot in the lung.

- Myocarditis, an inflamed heart.

While it’s hard to say precisely whether these conditions were caused by COVID, they are most likely linked to it, says Dr. Schamess. A March 2022 study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, for example, found that people who had recovered from COVID-19 had a 40% higher risk of being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes over the next year.

“We don’t know for sure that infection with COVID-19 triggered someone’s diabetes – it may have been that they already had risk factors and the virus pushed them over the edge,” he says.

COVID-19 itself may also worsen conditions you already have, such as asthma, sleep apnea, or fibromyalgia. “We see patients with previously mild asthma who come in constantly coughing and wheezing, for example,” says Dr. Schamess. “They usually respond well once we start aggressive treatment.” That might include a continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP, setup to help treat sleep apnea, or gabapentin to treat fibromyalgia symptoms.

Is it long COVID or something else?

Long COVID can cause a long list of symptoms, and they can easily mean other ailments. That’s one reason why, if your symptoms last for more than a month, it’s important to see a doctor, Ms. Baloun says. They can run a wide variety of tests to check for other conditions, such as a thyroid disorder or vitamin deficiency, that could be confused with long COVID.

They should also run blood tests such as D-dimer. This helps rule out a pulmonary embolism, which can be a complication of COVID-19 and also causes symptoms that may mimic long COVID, such as breathlessness and anxiety. They will also run tests to look for inflammation, Ms. Baloun says.

“These tests can’t provide definitive answers, but they can help provide clues as to what’s causing symptoms and whether they are related to long COVID,” she says.

What’s just as important, says Dr. Schamess, is a careful medical history. This can help pinpoint exactly when symptoms started, when they worsened, and whether anything else could have triggered them.

“I saw a patient recently who presented with symptoms of brain fog, memory loss, fatigue, headache, and sleep disturbance 5 months after she had COVID-19,” says Dr. Schamess. “After we talked, we realized that her symptoms were due to a fainting spell a couple of months earlier where she whacked her head very hard. She didn’t have long COVID – she had a concussion. But I wouldn’t have picked that up if I had just run a whole battery of tests.”

Ms. Stern agrees. “If you have long COVID, you may come across doctors who dismiss your symptoms, especially if your workups don’t show an obvious problem,” she says. “But you know your body. If it still seems like something is wrong, then you need to continue to push until you find answers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

New Yorker Lyss Stern came down with COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic, in March 2020. She ran a 103° F fever for 5 days straight and was bedridden for several weeks. Yet symptoms such as a persistent headache and tinnitus, or ringing in her ears, lingered.

“Four months later, I still couldn’t walk four blocks without becoming winded,” says Ms. Stern, 48. Five months after her diagnosis, her doctors finally gave a name to her condition: long COVID.

Long COVID is known by many different names: long-haul COVID, postacute COVID-19, or even chronic COVID. It’s a general term used to describe the range of ongoing health problems people can have after their infection.

Another earlier report found that one in five COVID-19 survivors between the ages of 18 and 64, and one in four survivors aged at least 65, have a health condition that may be related to their previous bout with the virus.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to screen for long COVID.

“There’s no definite laboratory test to give us a diagnosis,” says Daniel Sterman, MD, director of the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York. “We’re also still working on a definition, since there’s a whole slew of symptoms associated with the condition.”

It’s a challenge that Ms. Stern is personally acquainted with after she bounced from doctor to doctor for several months before she found her way to the Center for Post-COVID Care at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. “It was a relief to have an official diagnosis, even if it didn’t bring immediate answers,” she says.

What to look for

Many people who become infected with COVID-19 get symptoms that linger for 2-3 weeks after their infection has cleared, says Brittany Baloun, a certified nurse practitioner at the Cleveland Clinic. “It’s not unusual to feel some residual shortness of breath or heart palpitations, especially if you are exerting yourself,” she says. “The acute phase of COVID itself can last for up to 14 days. But if it’s been 30 days since you came down with the virus, and your symptoms are still there and not improving, it indicates some level of long COVID.”

More than 200 symptoms can be linked to long COVID. But perhaps the one that stands out the most is constant fatigue that interferes with daily life.

“We often hear that these patients can’t fold the laundry or take a short walk with their dog without feeling exhausted,” Ms. Baloun says.

This exhaustion may get worse after patients exercise or do something mentally taxing, a condition known as postexertional malaise.

“It can be crushing fatigue; I may clean my room for an hour and talk to a friend, and the next day feel like I can’t get out of bed,” says Allison Guy, 36, who was diagnosed with COVID in February 2021. She’s now a long-COVID advocate in Washington.

Other symptoms can be divided into different categories, which include cardiac/lung symptoms such as shortness of breath, coughing, chest pain, and heart palpitations, as well as neurologic symptoms.

One of the most common neurologic symptoms is brain fog, says Andrew Schamess, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, who runs its post-COVID recovery program. “Patients describe feeling ‘fuzzy’ or ‘spacey,’ and often report that they are forgetful or have memory problems,” he says. Others include:

- Headache.

- Sleep problems. One 2022 study from the Cleveland Clinic found that more than 40% of patients with long COVID reported sleep disturbances.

- Dizziness when standing.

- Pins-and-needles feelings.

- Changes in smell or taste.

- Depression or anxiety.

You could also have digestive symptoms such as diarrhea or stomach pain. Other symptoms include joint or muscle pain, rashes, or changes in menstrual cycles.

Risk of having other health conditions

People who have had COVID-19, particularly a severe case, may be more at risk of getting other health conditions, such as:

- Type 2 diabetes.

- Kidney failure.

- Pulmonary embolism, or a blood clot in the lung.

- Myocarditis, an inflamed heart.

While it’s hard to say precisely whether these conditions were caused by COVID, they are most likely linked to it, says Dr. Schamess. A March 2022 study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, for example, found that people who had recovered from COVID-19 had a 40% higher risk of being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes over the next year.

“We don’t know for sure that infection with COVID-19 triggered someone’s diabetes – it may have been that they already had risk factors and the virus pushed them over the edge,” he says.

COVID-19 itself may also worsen conditions you already have, such as asthma, sleep apnea, or fibromyalgia. “We see patients with previously mild asthma who come in constantly coughing and wheezing, for example,” says Dr. Schamess. “They usually respond well once we start aggressive treatment.” That might include a continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP, setup to help treat sleep apnea, or gabapentin to treat fibromyalgia symptoms.

Is it long COVID or something else?

Long COVID can cause a long list of symptoms, and they can easily mean other ailments. That’s one reason why, if your symptoms last for more than a month, it’s important to see a doctor, Ms. Baloun says. They can run a wide variety of tests to check for other conditions, such as a thyroid disorder or vitamin deficiency, that could be confused with long COVID.

They should also run blood tests such as D-dimer. This helps rule out a pulmonary embolism, which can be a complication of COVID-19 and also causes symptoms that may mimic long COVID, such as breathlessness and anxiety. They will also run tests to look for inflammation, Ms. Baloun says.

“These tests can’t provide definitive answers, but they can help provide clues as to what’s causing symptoms and whether they are related to long COVID,” she says.

What’s just as important, says Dr. Schamess, is a careful medical history. This can help pinpoint exactly when symptoms started, when they worsened, and whether anything else could have triggered them.

“I saw a patient recently who presented with symptoms of brain fog, memory loss, fatigue, headache, and sleep disturbance 5 months after she had COVID-19,” says Dr. Schamess. “After we talked, we realized that her symptoms were due to a fainting spell a couple of months earlier where she whacked her head very hard. She didn’t have long COVID – she had a concussion. But I wouldn’t have picked that up if I had just run a whole battery of tests.”

Ms. Stern agrees. “If you have long COVID, you may come across doctors who dismiss your symptoms, especially if your workups don’t show an obvious problem,” she says. “But you know your body. If it still seems like something is wrong, then you need to continue to push until you find answers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

New Yorker Lyss Stern came down with COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic, in March 2020. She ran a 103° F fever for 5 days straight and was bedridden for several weeks. Yet symptoms such as a persistent headache and tinnitus, or ringing in her ears, lingered.

“Four months later, I still couldn’t walk four blocks without becoming winded,” says Ms. Stern, 48. Five months after her diagnosis, her doctors finally gave a name to her condition: long COVID.

Long COVID is known by many different names: long-haul COVID, postacute COVID-19, or even chronic COVID. It’s a general term used to describe the range of ongoing health problems people can have after their infection.

Another earlier report found that one in five COVID-19 survivors between the ages of 18 and 64, and one in four survivors aged at least 65, have a health condition that may be related to their previous bout with the virus.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to screen for long COVID.

“There’s no definite laboratory test to give us a diagnosis,” says Daniel Sterman, MD, director of the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine at NYU Langone Health in New York. “We’re also still working on a definition, since there’s a whole slew of symptoms associated with the condition.”

It’s a challenge that Ms. Stern is personally acquainted with after she bounced from doctor to doctor for several months before she found her way to the Center for Post-COVID Care at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. “It was a relief to have an official diagnosis, even if it didn’t bring immediate answers,” she says.

What to look for

Many people who become infected with COVID-19 get symptoms that linger for 2-3 weeks after their infection has cleared, says Brittany Baloun, a certified nurse practitioner at the Cleveland Clinic. “It’s not unusual to feel some residual shortness of breath or heart palpitations, especially if you are exerting yourself,” she says. “The acute phase of COVID itself can last for up to 14 days. But if it’s been 30 days since you came down with the virus, and your symptoms are still there and not improving, it indicates some level of long COVID.”

More than 200 symptoms can be linked to long COVID. But perhaps the one that stands out the most is constant fatigue that interferes with daily life.

“We often hear that these patients can’t fold the laundry or take a short walk with their dog without feeling exhausted,” Ms. Baloun says.

This exhaustion may get worse after patients exercise or do something mentally taxing, a condition known as postexertional malaise.

“It can be crushing fatigue; I may clean my room for an hour and talk to a friend, and the next day feel like I can’t get out of bed,” says Allison Guy, 36, who was diagnosed with COVID in February 2021. She’s now a long-COVID advocate in Washington.

Other symptoms can be divided into different categories, which include cardiac/lung symptoms such as shortness of breath, coughing, chest pain, and heart palpitations, as well as neurologic symptoms.

One of the most common neurologic symptoms is brain fog, says Andrew Schamess, MD, a professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, who runs its post-COVID recovery program. “Patients describe feeling ‘fuzzy’ or ‘spacey,’ and often report that they are forgetful or have memory problems,” he says. Others include:

- Headache.

- Sleep problems. One 2022 study from the Cleveland Clinic found that more than 40% of patients with long COVID reported sleep disturbances.

- Dizziness when standing.

- Pins-and-needles feelings.

- Changes in smell or taste.

- Depression or anxiety.

You could also have digestive symptoms such as diarrhea or stomach pain. Other symptoms include joint or muscle pain, rashes, or changes in menstrual cycles.

Risk of having other health conditions

People who have had COVID-19, particularly a severe case, may be more at risk of getting other health conditions, such as:

- Type 2 diabetes.

- Kidney failure.

- Pulmonary embolism, or a blood clot in the lung.

- Myocarditis, an inflamed heart.

While it’s hard to say precisely whether these conditions were caused by COVID, they are most likely linked to it, says Dr. Schamess. A March 2022 study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, for example, found that people who had recovered from COVID-19 had a 40% higher risk of being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes over the next year.

“We don’t know for sure that infection with COVID-19 triggered someone’s diabetes – it may have been that they already had risk factors and the virus pushed them over the edge,” he says.

COVID-19 itself may also worsen conditions you already have, such as asthma, sleep apnea, or fibromyalgia. “We see patients with previously mild asthma who come in constantly coughing and wheezing, for example,” says Dr. Schamess. “They usually respond well once we start aggressive treatment.” That might include a continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP, setup to help treat sleep apnea, or gabapentin to treat fibromyalgia symptoms.

Is it long COVID or something else?

Long COVID can cause a long list of symptoms, and they can easily mean other ailments. That’s one reason why, if your symptoms last for more than a month, it’s important to see a doctor, Ms. Baloun says. They can run a wide variety of tests to check for other conditions, such as a thyroid disorder or vitamin deficiency, that could be confused with long COVID.

They should also run blood tests such as D-dimer. This helps rule out a pulmonary embolism, which can be a complication of COVID-19 and also causes symptoms that may mimic long COVID, such as breathlessness and anxiety. They will also run tests to look for inflammation, Ms. Baloun says.

“These tests can’t provide definitive answers, but they can help provide clues as to what’s causing symptoms and whether they are related to long COVID,” she says.

What’s just as important, says Dr. Schamess, is a careful medical history. This can help pinpoint exactly when symptoms started, when they worsened, and whether anything else could have triggered them.

“I saw a patient recently who presented with symptoms of brain fog, memory loss, fatigue, headache, and sleep disturbance 5 months after she had COVID-19,” says Dr. Schamess. “After we talked, we realized that her symptoms were due to a fainting spell a couple of months earlier where she whacked her head very hard. She didn’t have long COVID – she had a concussion. But I wouldn’t have picked that up if I had just run a whole battery of tests.”

Ms. Stern agrees. “If you have long COVID, you may come across doctors who dismiss your symptoms, especially if your workups don’t show an obvious problem,” she says. “But you know your body. If it still seems like something is wrong, then you need to continue to push until you find answers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Race-specific spirometry may miss emphysema diagnoses

An overreliance on spirometry to identify emphysema led to missed cases in Black individuals, particularly men, based on a secondary data analysis of 2,674 people.

“Over the last few years, there has been growing debate around the use of race adjustment in diagnostic algorithms and equations commonly used in medicine,” lead author Gabrielle Yi-Hui Liu, MD, said in an interview. “Whereas, previously it was common to accept racial or ethnic differences in clinical measures and outcomes as inherent differences among populations, there is now more recognition of how racism, socioeconomic status, and environmental exposures can cause these racial differences. Our initial interest in this study was to examine how the use of race-specific spirometry reference equations, and the use of spirometry in general, may be contributing to racial disparities.”

“Previous studies have suggested that the use of race-specific equations in spirometry can exacerbate racial inequities in healthcare outcomes by under-recognition of early disease in Black adults, and this study adds to that evidence,” said Suman Pal, MBBS, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in an interview.

“By examining the crucial ways in which systemic factors in medicine, such as race-specific equations, exacerbate racial inequities in healthcare, this study is a timely analysis in a moment of national reckoning of structural racism,” said Dr. Pal, who was not involved in the study.

In a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Dr. Liu and colleagues at Northwestern University, Chicago, conducted a secondary analysis of data from the CARDIA Lung study (Coronary Artery Risk Development In Young Adults).

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of emphysema among participants with various measures of normal spirometry results, stratified by sex and race. The normal results included an forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)–forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio greater than or equal to 0.7 or greater than or equal to the lower limit of normal. The participants also were stratified by FEV1 percent predicted, using race-specific reference equations, for FEV1 between 80% and 99% of predicted, or an FEV1 between 100% and 120% of predicted.

The study population included 485 Black men, 762 Black women, 659 White men, and 768 White women who received both a CT scan (in 2010-2011) and spirometry (obtained in 2015-2016) in the CARDIA study. The mean age of the participants at the spirometry exam was 55 years.

A total of 5.3% of the participants had emphysema after stratifying by FEV1-FVC ratio. The prevalence was significantly higher for Black men, compared with White men (12.3% vs. 4.0%; relative risk, 3.0), and for Black women, compared with White women (5.0% vs. 2.6%; RR, 1.9).

The association between Black race and emphysema risk persisted but decreased when the researchers used a race-neutral estimate.

When the participants were stratified by race-specific FEV1 percent predicted, 6.5% of individuals with a race-specific FEV1 between 80% and 99% had emphysema. After controlling for factors including age and smoking, emphysema was significantly more prevalent in Black men versus White men (15.5% vs. 4.0%) and in Black women, compared with White women (6.6% vs. 3.4%).

The racial difference persisted in men with a race-specific FEV1 between 100% and 120% of predicted. Of these, 4.0% had emphysema. The prevalence was significantly higher in Black men, compared with White men (13.9% vs. 2.2%), but similar between Black women and White women (2.6% vs. 2.0%).

The use of race-neutral equations reduced, but did not eliminate, these disparities, the researchers said.

The findings were limited by the lack of CT imaging data from the same visit as the final spirometry collection, the researchers noted. “Given that imaging was obtained 5 years before spirometry and emphysema is an irreversible finding, this may have led to an overall underestimation of the prevalence of emphysema.”

Spirometry alone misses cases

“We were surprised by the substantial rates of emphysema we saw among Black men in our cohort with normal spirometry,” Dr. Liu said in an interview. “We did not expect to find than more than one in eight Black men with an FEV1 between 100% and 120% predicted would have emphysema – a rate more than six times higher than White men with the same range of FEV1.”

“One takeaway is that we are likely missing a lot of people with impaired respiratory health or true lung disease by only using spirometry to diagnose COPD,” said Dr. Liu. In clinical practice, “physicians should consider ordering CT scans on patients with normal spirometry who have respiratory symptoms such as cough or shortness of breath. If emphysema is found, physicians should discuss mitigating any potential risk factors and consider the use of COPD medications such as inhalers.

“Our findings also support using race-neutral reference equations to interpret spirometry instead of race-specific equations. Racial disparities in rates of emphysema among those with ‘normal’ FEV1 [between 80% and 120% predicted], were attenuated or eliminated when race-neutral equations were used to calculate FEV1. This suggests that race-specific equations are normalizing worse lung health in Black adults,” Dr. Liu explained.

“We need to continue research into additional tools that can be used to assess respiratory health and diagnose COPD, while keeping in mind how these tools may affect racial disparities,” said Dr. Liu. “Our study suggests that our reliance on spirometry measures such as FEV1/FVC ratio and FEV1 is missing a number of people with respiratory symptoms and CT evidence of lung disease, and that this is disproportionately affecting Black adults in the United States.” Looking ahead, “it is important to find better tools to identify people with impaired respiratory health or early manifestations of disease so we can intercept chronic lung disease before it becomes clinically apparent and patients have sustained significant lung damage.”

The CARDIA study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Northwestern University, the University of Minnesota, and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Dr. Liu was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Pal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This article was updated 7/22/2022.

An overreliance on spirometry to identify emphysema led to missed cases in Black individuals, particularly men, based on a secondary data analysis of 2,674 people.

“Over the last few years, there has been growing debate around the use of race adjustment in diagnostic algorithms and equations commonly used in medicine,” lead author Gabrielle Yi-Hui Liu, MD, said in an interview. “Whereas, previously it was common to accept racial or ethnic differences in clinical measures and outcomes as inherent differences among populations, there is now more recognition of how racism, socioeconomic status, and environmental exposures can cause these racial differences. Our initial interest in this study was to examine how the use of race-specific spirometry reference equations, and the use of spirometry in general, may be contributing to racial disparities.”

“Previous studies have suggested that the use of race-specific equations in spirometry can exacerbate racial inequities in healthcare outcomes by under-recognition of early disease in Black adults, and this study adds to that evidence,” said Suman Pal, MBBS, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in an interview.

“By examining the crucial ways in which systemic factors in medicine, such as race-specific equations, exacerbate racial inequities in healthcare, this study is a timely analysis in a moment of national reckoning of structural racism,” said Dr. Pal, who was not involved in the study.

In a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Dr. Liu and colleagues at Northwestern University, Chicago, conducted a secondary analysis of data from the CARDIA Lung study (Coronary Artery Risk Development In Young Adults).

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of emphysema among participants with various measures of normal spirometry results, stratified by sex and race. The normal results included an forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)–forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio greater than or equal to 0.7 or greater than or equal to the lower limit of normal. The participants also were stratified by FEV1 percent predicted, using race-specific reference equations, for FEV1 between 80% and 99% of predicted, or an FEV1 between 100% and 120% of predicted.

The study population included 485 Black men, 762 Black women, 659 White men, and 768 White women who received both a CT scan (in 2010-2011) and spirometry (obtained in 2015-2016) in the CARDIA study. The mean age of the participants at the spirometry exam was 55 years.

A total of 5.3% of the participants had emphysema after stratifying by FEV1-FVC ratio. The prevalence was significantly higher for Black men, compared with White men (12.3% vs. 4.0%; relative risk, 3.0), and for Black women, compared with White women (5.0% vs. 2.6%; RR, 1.9).

The association between Black race and emphysema risk persisted but decreased when the researchers used a race-neutral estimate.

When the participants were stratified by race-specific FEV1 percent predicted, 6.5% of individuals with a race-specific FEV1 between 80% and 99% had emphysema. After controlling for factors including age and smoking, emphysema was significantly more prevalent in Black men versus White men (15.5% vs. 4.0%) and in Black women, compared with White women (6.6% vs. 3.4%).

The racial difference persisted in men with a race-specific FEV1 between 100% and 120% of predicted. Of these, 4.0% had emphysema. The prevalence was significantly higher in Black men, compared with White men (13.9% vs. 2.2%), but similar between Black women and White women (2.6% vs. 2.0%).

The use of race-neutral equations reduced, but did not eliminate, these disparities, the researchers said.

The findings were limited by the lack of CT imaging data from the same visit as the final spirometry collection, the researchers noted. “Given that imaging was obtained 5 years before spirometry and emphysema is an irreversible finding, this may have led to an overall underestimation of the prevalence of emphysema.”

Spirometry alone misses cases

“We were surprised by the substantial rates of emphysema we saw among Black men in our cohort with normal spirometry,” Dr. Liu said in an interview. “We did not expect to find than more than one in eight Black men with an FEV1 between 100% and 120% predicted would have emphysema – a rate more than six times higher than White men with the same range of FEV1.”

“One takeaway is that we are likely missing a lot of people with impaired respiratory health or true lung disease by only using spirometry to diagnose COPD,” said Dr. Liu. In clinical practice, “physicians should consider ordering CT scans on patients with normal spirometry who have respiratory symptoms such as cough or shortness of breath. If emphysema is found, physicians should discuss mitigating any potential risk factors and consider the use of COPD medications such as inhalers.

“Our findings also support using race-neutral reference equations to interpret spirometry instead of race-specific equations. Racial disparities in rates of emphysema among those with ‘normal’ FEV1 [between 80% and 120% predicted], were attenuated or eliminated when race-neutral equations were used to calculate FEV1. This suggests that race-specific equations are normalizing worse lung health in Black adults,” Dr. Liu explained.

“We need to continue research into additional tools that can be used to assess respiratory health and diagnose COPD, while keeping in mind how these tools may affect racial disparities,” said Dr. Liu. “Our study suggests that our reliance on spirometry measures such as FEV1/FVC ratio and FEV1 is missing a number of people with respiratory symptoms and CT evidence of lung disease, and that this is disproportionately affecting Black adults in the United States.” Looking ahead, “it is important to find better tools to identify people with impaired respiratory health or early manifestations of disease so we can intercept chronic lung disease before it becomes clinically apparent and patients have sustained significant lung damage.”

The CARDIA study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Northwestern University, the University of Minnesota, and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Dr. Liu was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Pal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This article was updated 7/22/2022.

An overreliance on spirometry to identify emphysema led to missed cases in Black individuals, particularly men, based on a secondary data analysis of 2,674 people.

“Over the last few years, there has been growing debate around the use of race adjustment in diagnostic algorithms and equations commonly used in medicine,” lead author Gabrielle Yi-Hui Liu, MD, said in an interview. “Whereas, previously it was common to accept racial or ethnic differences in clinical measures and outcomes as inherent differences among populations, there is now more recognition of how racism, socioeconomic status, and environmental exposures can cause these racial differences. Our initial interest in this study was to examine how the use of race-specific spirometry reference equations, and the use of spirometry in general, may be contributing to racial disparities.”

“Previous studies have suggested that the use of race-specific equations in spirometry can exacerbate racial inequities in healthcare outcomes by under-recognition of early disease in Black adults, and this study adds to that evidence,” said Suman Pal, MBBS, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in an interview.

“By examining the crucial ways in which systemic factors in medicine, such as race-specific equations, exacerbate racial inequities in healthcare, this study is a timely analysis in a moment of national reckoning of structural racism,” said Dr. Pal, who was not involved in the study.

In a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Dr. Liu and colleagues at Northwestern University, Chicago, conducted a secondary analysis of data from the CARDIA Lung study (Coronary Artery Risk Development In Young Adults).

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of emphysema among participants with various measures of normal spirometry results, stratified by sex and race. The normal results included an forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)–forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio greater than or equal to 0.7 or greater than or equal to the lower limit of normal. The participants also were stratified by FEV1 percent predicted, using race-specific reference equations, for FEV1 between 80% and 99% of predicted, or an FEV1 between 100% and 120% of predicted.

The study population included 485 Black men, 762 Black women, 659 White men, and 768 White women who received both a CT scan (in 2010-2011) and spirometry (obtained in 2015-2016) in the CARDIA study. The mean age of the participants at the spirometry exam was 55 years.

A total of 5.3% of the participants had emphysema after stratifying by FEV1-FVC ratio. The prevalence was significantly higher for Black men, compared with White men (12.3% vs. 4.0%; relative risk, 3.0), and for Black women, compared with White women (5.0% vs. 2.6%; RR, 1.9).

The association between Black race and emphysema risk persisted but decreased when the researchers used a race-neutral estimate.