User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

The surprising failure of vitamin D in deficient kids

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

My basic gripe is that you’ve got all these observational studies linking lower levels of vitamin D to everything from dementia to falls to cancer to COVID infection, and then you do a big randomized trial of supplementation and don’t see an effect.

And the explanation is that vitamin D is not necessarily the thing causing these bad outcomes; it’s a bystander – a canary in the coal mine. Your vitamin D level is a marker of your lifestyle; it’s higher in people who eat healthier foods, who exercise, and who spend more time out in the sun.

And yet ... if you were to ask me whether supplementing vitamin D in children with vitamin D deficiency would help them grow better and be healthier, I probably would have been on board for the idea.

And, it looks like, I would have been wrong.

Yes, it’s another negative randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to add to the seemingly ever-growing body of literature suggesting that your money is better spent on a day at the park rather than buying D3 from your local GNC.

We are talking about this study, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Briefly, 8,851 children from around Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, were randomized to receive 14,000 international units of vitamin D3 or placebo every week for 3 years.

Before we get into the results of the study, I need to point out that this part of Mongolia has a high rate of vitamin D deficiency. Beyond that, a prior observational study by these authors had shown that lower vitamin D levels were linked to the risk of acquiring latent tuberculosis infection in this area. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with poorer growth metrics in children. Given the global scourge that is TB (around 2 million deaths a year) and childhood malnutrition (around 10% of children around the world), vitamin D supplementation is incredibly attractive as a public health intervention. It is relatively low on side effects and, importantly, it is cheap – and thus scalable.

Back to the study. These kids had pretty poor vitamin D levels at baseline; 95% of them were deficient, based on the accepted standard of levels less than 20 ng/mL. Over 30% were severely deficient, with levels less than 10 ng/mL.

The initial purpose of this study was to see if supplementation would prevent TB, but that analysis, which was published a few months ago, was negative. Vitamin D levels went up dramatically in the intervention group – they were taking their pills – but there was no difference in the rate of latent TB infection, active TB, other respiratory infections, or even serum interferon gamma levels.

Nothing.

But to be fair, the TB seroconversion rate was lower than expected, potentially leading to an underpowered study.

Which brings us to the just-published analysis which moves away from infectious disease to something where vitamin D should have some stronger footing: growth.

Would the kids who were randomized to vitamin D, those same kids who got their vitamin D levels into the normal range over 3 years of supplementation, grow more or grow better than the kids who didn’t?

And, unfortunately, the answer is still no.

At the end of follow-up, height z scores were not different between the groups. BMI z scores were not different between the groups. Pubertal development was not different between the groups. This was true not only overall, but across various subgroups, including analyses of those kids who had vitamin D levels less than 10 ng/mL to start with.

So, what’s going on? There are two very broad possibilities we can endorse. First, there’s the idea that vitamin D supplementation simply doesn’t do much for health. This is supported, now, by a long string of large clinical trials that show no effect across a variety of disease states and predisease states. In other words, the observational data linking low vitamin D to bad outcomes is correlation, not causation.

Or we can take the tack of some vitamin D apologists and decide that this trial just got it wrong. Perhaps the dose wasn’t given correctly, or 3 years isn’t long enough to see a real difference, or the growth metrics were wrong, or vitamin D needs to be given alongside something else to really work and so on. This is fine; no study is perfect and there is always something to criticize, believe me. But we need to be careful not to fall into the baby-and-bathwater fallacy. Just because we think a study could have done something better, or differently, doesn’t mean we can ignore all the results. And as each new randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation comes out, it’s getting harder and harder to believe that these trialists keep getting their methods wrong. Maybe they are just testing something that doesn’t work.

What to do? Well, it should be obvious. If low vitamin D levels are linked to TB rates and poor growth but supplementation doesn’t fix the problem, then we have to fix what is upstream of the problem. We need to boost vitamin D levels not through supplements, but through nutrition, exercise, activity, and getting outside. That’s a randomized trial you can sign me up for any day.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

My basic gripe is that you’ve got all these observational studies linking lower levels of vitamin D to everything from dementia to falls to cancer to COVID infection, and then you do a big randomized trial of supplementation and don’t see an effect.

And the explanation is that vitamin D is not necessarily the thing causing these bad outcomes; it’s a bystander – a canary in the coal mine. Your vitamin D level is a marker of your lifestyle; it’s higher in people who eat healthier foods, who exercise, and who spend more time out in the sun.

And yet ... if you were to ask me whether supplementing vitamin D in children with vitamin D deficiency would help them grow better and be healthier, I probably would have been on board for the idea.

And, it looks like, I would have been wrong.

Yes, it’s another negative randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to add to the seemingly ever-growing body of literature suggesting that your money is better spent on a day at the park rather than buying D3 from your local GNC.

We are talking about this study, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Briefly, 8,851 children from around Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, were randomized to receive 14,000 international units of vitamin D3 or placebo every week for 3 years.

Before we get into the results of the study, I need to point out that this part of Mongolia has a high rate of vitamin D deficiency. Beyond that, a prior observational study by these authors had shown that lower vitamin D levels were linked to the risk of acquiring latent tuberculosis infection in this area. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with poorer growth metrics in children. Given the global scourge that is TB (around 2 million deaths a year) and childhood malnutrition (around 10% of children around the world), vitamin D supplementation is incredibly attractive as a public health intervention. It is relatively low on side effects and, importantly, it is cheap – and thus scalable.

Back to the study. These kids had pretty poor vitamin D levels at baseline; 95% of them were deficient, based on the accepted standard of levels less than 20 ng/mL. Over 30% were severely deficient, with levels less than 10 ng/mL.

The initial purpose of this study was to see if supplementation would prevent TB, but that analysis, which was published a few months ago, was negative. Vitamin D levels went up dramatically in the intervention group – they were taking their pills – but there was no difference in the rate of latent TB infection, active TB, other respiratory infections, or even serum interferon gamma levels.

Nothing.

But to be fair, the TB seroconversion rate was lower than expected, potentially leading to an underpowered study.

Which brings us to the just-published analysis which moves away from infectious disease to something where vitamin D should have some stronger footing: growth.

Would the kids who were randomized to vitamin D, those same kids who got their vitamin D levels into the normal range over 3 years of supplementation, grow more or grow better than the kids who didn’t?

And, unfortunately, the answer is still no.

At the end of follow-up, height z scores were not different between the groups. BMI z scores were not different between the groups. Pubertal development was not different between the groups. This was true not only overall, but across various subgroups, including analyses of those kids who had vitamin D levels less than 10 ng/mL to start with.

So, what’s going on? There are two very broad possibilities we can endorse. First, there’s the idea that vitamin D supplementation simply doesn’t do much for health. This is supported, now, by a long string of large clinical trials that show no effect across a variety of disease states and predisease states. In other words, the observational data linking low vitamin D to bad outcomes is correlation, not causation.

Or we can take the tack of some vitamin D apologists and decide that this trial just got it wrong. Perhaps the dose wasn’t given correctly, or 3 years isn’t long enough to see a real difference, or the growth metrics were wrong, or vitamin D needs to be given alongside something else to really work and so on. This is fine; no study is perfect and there is always something to criticize, believe me. But we need to be careful not to fall into the baby-and-bathwater fallacy. Just because we think a study could have done something better, or differently, doesn’t mean we can ignore all the results. And as each new randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation comes out, it’s getting harder and harder to believe that these trialists keep getting their methods wrong. Maybe they are just testing something that doesn’t work.

What to do? Well, it should be obvious. If low vitamin D levels are linked to TB rates and poor growth but supplementation doesn’t fix the problem, then we have to fix what is upstream of the problem. We need to boost vitamin D levels not through supplements, but through nutrition, exercise, activity, and getting outside. That’s a randomized trial you can sign me up for any day.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

My basic gripe is that you’ve got all these observational studies linking lower levels of vitamin D to everything from dementia to falls to cancer to COVID infection, and then you do a big randomized trial of supplementation and don’t see an effect.

And the explanation is that vitamin D is not necessarily the thing causing these bad outcomes; it’s a bystander – a canary in the coal mine. Your vitamin D level is a marker of your lifestyle; it’s higher in people who eat healthier foods, who exercise, and who spend more time out in the sun.

And yet ... if you were to ask me whether supplementing vitamin D in children with vitamin D deficiency would help them grow better and be healthier, I probably would have been on board for the idea.

And, it looks like, I would have been wrong.

Yes, it’s another negative randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to add to the seemingly ever-growing body of literature suggesting that your money is better spent on a day at the park rather than buying D3 from your local GNC.

We are talking about this study, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Briefly, 8,851 children from around Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, were randomized to receive 14,000 international units of vitamin D3 or placebo every week for 3 years.

Before we get into the results of the study, I need to point out that this part of Mongolia has a high rate of vitamin D deficiency. Beyond that, a prior observational study by these authors had shown that lower vitamin D levels were linked to the risk of acquiring latent tuberculosis infection in this area. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with poorer growth metrics in children. Given the global scourge that is TB (around 2 million deaths a year) and childhood malnutrition (around 10% of children around the world), vitamin D supplementation is incredibly attractive as a public health intervention. It is relatively low on side effects and, importantly, it is cheap – and thus scalable.

Back to the study. These kids had pretty poor vitamin D levels at baseline; 95% of them were deficient, based on the accepted standard of levels less than 20 ng/mL. Over 30% were severely deficient, with levels less than 10 ng/mL.

The initial purpose of this study was to see if supplementation would prevent TB, but that analysis, which was published a few months ago, was negative. Vitamin D levels went up dramatically in the intervention group – they were taking their pills – but there was no difference in the rate of latent TB infection, active TB, other respiratory infections, or even serum interferon gamma levels.

Nothing.

But to be fair, the TB seroconversion rate was lower than expected, potentially leading to an underpowered study.

Which brings us to the just-published analysis which moves away from infectious disease to something where vitamin D should have some stronger footing: growth.

Would the kids who were randomized to vitamin D, those same kids who got their vitamin D levels into the normal range over 3 years of supplementation, grow more or grow better than the kids who didn’t?

And, unfortunately, the answer is still no.

At the end of follow-up, height z scores were not different between the groups. BMI z scores were not different between the groups. Pubertal development was not different between the groups. This was true not only overall, but across various subgroups, including analyses of those kids who had vitamin D levels less than 10 ng/mL to start with.

So, what’s going on? There are two very broad possibilities we can endorse. First, there’s the idea that vitamin D supplementation simply doesn’t do much for health. This is supported, now, by a long string of large clinical trials that show no effect across a variety of disease states and predisease states. In other words, the observational data linking low vitamin D to bad outcomes is correlation, not causation.

Or we can take the tack of some vitamin D apologists and decide that this trial just got it wrong. Perhaps the dose wasn’t given correctly, or 3 years isn’t long enough to see a real difference, or the growth metrics were wrong, or vitamin D needs to be given alongside something else to really work and so on. This is fine; no study is perfect and there is always something to criticize, believe me. But we need to be careful not to fall into the baby-and-bathwater fallacy. Just because we think a study could have done something better, or differently, doesn’t mean we can ignore all the results. And as each new randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation comes out, it’s getting harder and harder to believe that these trialists keep getting their methods wrong. Maybe they are just testing something that doesn’t work.

What to do? Well, it should be obvious. If low vitamin D levels are linked to TB rates and poor growth but supplementation doesn’t fix the problem, then we have to fix what is upstream of the problem. We need to boost vitamin D levels not through supplements, but through nutrition, exercise, activity, and getting outside. That’s a randomized trial you can sign me up for any day.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. flu activity already at mid-season levels

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Persistent asthma linked to higher carotid plaque burden

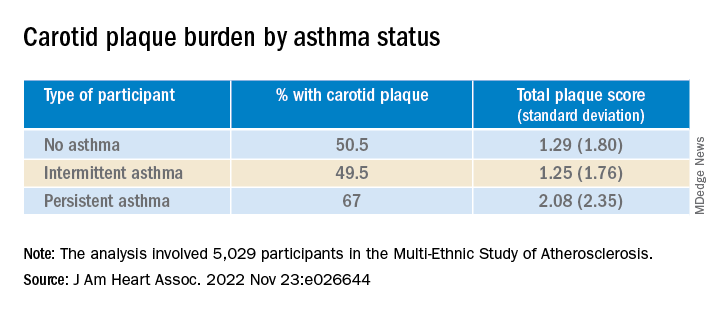

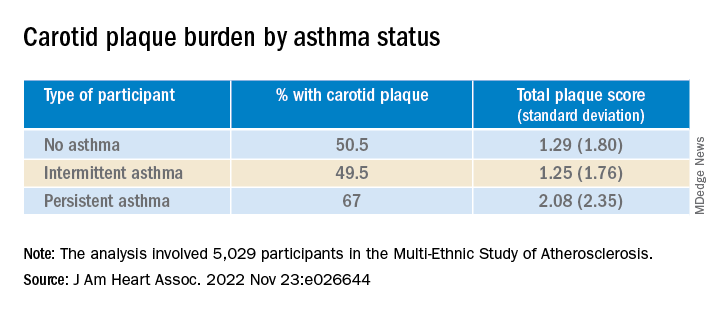

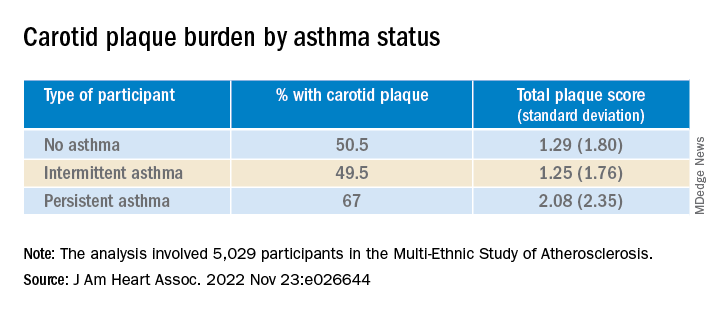

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

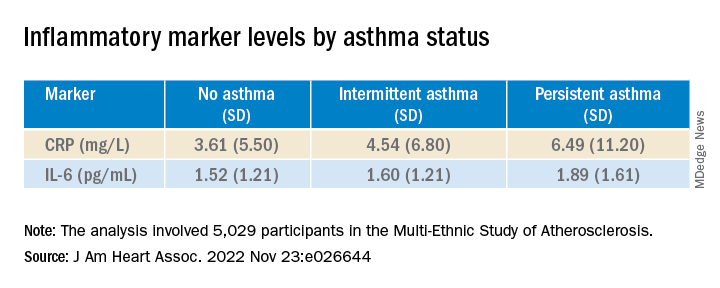

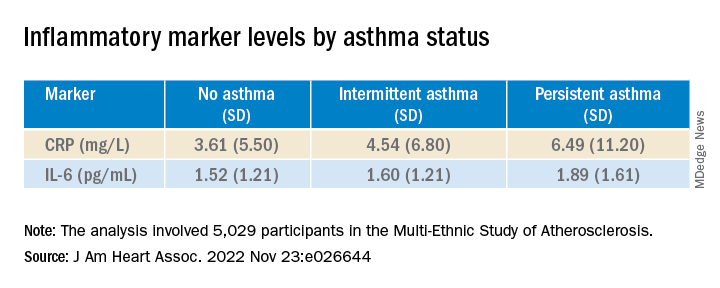

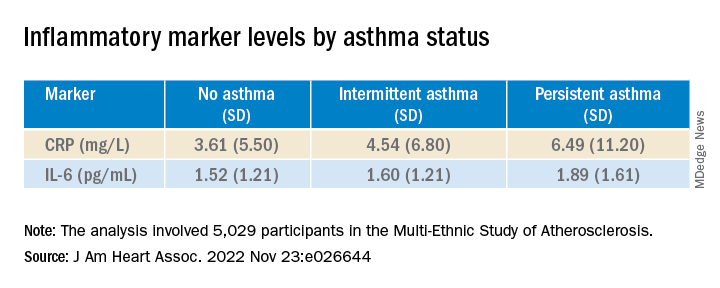

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study affirms shorter regimens for drug-resistant tuberculosis

Two short-course bedaquiline-containing treatment regimens for rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis showed “robust evidence” for superior efficacy and less ototoxicity compared to a 9-month injectable control regimen, researchers report.

The findings validate the World Health Organization’s current recommendation of a 9-month, bedaquiline-based oral regimen, “which was based only on observational data,” noted lead author Ruth Goodall, PhD, from the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, and colleagues.

The study was published in The Lancet.

The Standard Treatment Regimen of Anti-tuberculosis Drugs for Patients With MDR-TB (STREAM) stage 2 study was a randomized, phase 3, noninferiority trial conducted at 13 hospital clinics in seven countries that had prespecified tests for superiority if noninferiority was shown. The study enrolled individuals aged 15 years or older who had rifampicin-resistant TB without fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside resistance.

The study’s first stage, STREAM stage 1, showed that The 9-month regimen was recommended by the WHO in 2016. That recommendation was superceded in 2020 when concerns of hearing loss associated with aminoglycosides prompted the WHO to endorse a 9-month bedaquiline-containing, injectable-free alternative, the authors write.

Seeking shorter treatment for better outcomes

STREAM stage 2 used a 9-month injectable regimen as its control. The investigators measured it against a fully oral 9-month bedaquiline-based treatment (primary comparison), as well as a 6-month oral bedaquiline regimen that included 8 weeks of a second-line injectable (secondary comparison).

The 9-month fully oral treatment included levofloxacin, clofazimine, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 40 weeks; bedaquiline, high-dose isoniazid, and prothionamide were given for the 16-week intensive phase.

The 6-month regimen included bedaquiline, clofazimine, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin for 28 weeks, supplemented by high-dose isoniazid with kanamycin for an 8-week intensive phase.

For both comparisons, the primary outcome was favorable status at 76 weeks, defined as cultures that were negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis without a preceding unfavorable outcome (defined as any death, bacteriologic failure or recurrence, or major treatment change).

Among 517 participants in the modified intention-to-treat population across the study groups, 62% were men, and 38% were women (median age, 32.5 years).

For the primary comparison, 71% of the control group and 83% of the oral regimen group had a favorable outcome.

In the secondary comparison, 69% had a favorable outcome in the control group, compared with 91% of those receiving the 6-month regimen.

Although the rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was similar in all three groups, there was significantly less ototoxicity among patients who received the oral regimen, compared with control patients (2% vs. 9%); 4% of those taking the 6-month regimen had hearing loss, compared with 8% of control patients.

Exploratory analyses comparing both bedaquiline-containing regimens revealed a significantly higher proportion of favorable outcomes among participants receiving the 6-month regimen (91%), compared with patients taking the fully oral 9-month regimen (79%). There were no significant differences in the rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events.

The trial’s main limitation was its open-label design, which might have influenced decisions about treatment change, note the investigators.

“STREAM stage 2 has shown that two short-course, bedaquiline-containing regimens are not only non-inferior but superior to a 9-month injectable-containing regimen,” they conclude.

“The STREAM stage 2 fully oral regimen avoided the toxicity of aminoglycosides, and the 6-month regimen was highly effective, with reduced levels of ototoxicity. These two regimens offer promising treatment options for patients with MDR or rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis,” the authors write.

Dr. Goodall added, “Although both STREAM regimens were very effective, participants experienced relatively high levels of adverse events during the trial (though many of these were likely due to the close laboratory monitoring of the trial).

“While hearing loss was reduced on the 6-month regimen, it was not entirely eliminated,” she said. “Other new regimens in the field containing the medicine linezolid report side effects such as anemia and peripheral neuropathy. So more work needs to be done to ensure the treatment regimens are as safe and tolerable for patients as possible. In addition, even 6 months’ treatment is long for patients to tolerate, and further regimen shortening would be a welcome development for patients and health systems.”

‘A revolution in MDR tuberculosis’

“The authors must be commended on completing this challenging high-quality, phase 3, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial involving 13 health care facilities across Ethiopia, Georgia, India, Moldova, Mongolia, South Africa, and Uganda ... despite the COVID-19 pandemic,” noted Keertan Dheda, MD, PhD, and Christoph Lange, MD, PhD, in an accompanying comment titled, “A Revolution in the Management of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis”.

Although the WHO recently approved an all-oral 6-month bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid plus moxifloxacin (BPaLM) regimen, results from the alternate 6-month regimen examined in STREAM stage 2 “do provide confidence in using 2 months of an injectable as part of a salvage regimen in patients for whom MDR tuberculosis treatment is not successful” or in those with extensively drug-resistant (XDR) or pre-XDR TB, “for whom therapeutic options are few,” noted Dr. Dheda, from the University of Cape Town (South Africa) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Dr. Lange, from the University of Lübeck (Germany), Baylor College of Medicine, and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston.

The study authors and the commentators stress that safer and simpler treatments are still needed for MDR TB. “The search is now on for regimens that could further reduce duration, toxicity, and pill burden,” note Dr. Dheda and Dr. Lange.

However, they also note that “substantial resistance” to bedaquiline is already emerging. “Therefore, if we are to protect key drugs from becoming functionally redundant, drug-susceptibility testing capacity will need to be rapidly improved to minimize resistance amplification and onward disease transmission.”

The study was funded by USAID and Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Goodall has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Dheda has received funding from the EU and the South African Medical Research Council for studies related to the diagnosis or management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Dr. Lange is supported by the German Center for Infection Research and has received funding from the European Commission for studies on the development of novel antituberculosis medicines and for studies related to novel diagnostics of tuberculosis; consulting fees from INSMED; speaker’s fees from INSMED, GILEAD, and Janssen; and is a member of the data safety board of trials from Medicines sans Frontiers, all of which are unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two short-course bedaquiline-containing treatment regimens for rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis showed “robust evidence” for superior efficacy and less ototoxicity compared to a 9-month injectable control regimen, researchers report.

The findings validate the World Health Organization’s current recommendation of a 9-month, bedaquiline-based oral regimen, “which was based only on observational data,” noted lead author Ruth Goodall, PhD, from the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, and colleagues.

The study was published in The Lancet.

The Standard Treatment Regimen of Anti-tuberculosis Drugs for Patients With MDR-TB (STREAM) stage 2 study was a randomized, phase 3, noninferiority trial conducted at 13 hospital clinics in seven countries that had prespecified tests for superiority if noninferiority was shown. The study enrolled individuals aged 15 years or older who had rifampicin-resistant TB without fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside resistance.

The study’s first stage, STREAM stage 1, showed that The 9-month regimen was recommended by the WHO in 2016. That recommendation was superceded in 2020 when concerns of hearing loss associated with aminoglycosides prompted the WHO to endorse a 9-month bedaquiline-containing, injectable-free alternative, the authors write.

Seeking shorter treatment for better outcomes

STREAM stage 2 used a 9-month injectable regimen as its control. The investigators measured it against a fully oral 9-month bedaquiline-based treatment (primary comparison), as well as a 6-month oral bedaquiline regimen that included 8 weeks of a second-line injectable (secondary comparison).

The 9-month fully oral treatment included levofloxacin, clofazimine, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 40 weeks; bedaquiline, high-dose isoniazid, and prothionamide were given for the 16-week intensive phase.

The 6-month regimen included bedaquiline, clofazimine, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin for 28 weeks, supplemented by high-dose isoniazid with kanamycin for an 8-week intensive phase.

For both comparisons, the primary outcome was favorable status at 76 weeks, defined as cultures that were negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis without a preceding unfavorable outcome (defined as any death, bacteriologic failure or recurrence, or major treatment change).

Among 517 participants in the modified intention-to-treat population across the study groups, 62% were men, and 38% were women (median age, 32.5 years).

For the primary comparison, 71% of the control group and 83% of the oral regimen group had a favorable outcome.

In the secondary comparison, 69% had a favorable outcome in the control group, compared with 91% of those receiving the 6-month regimen.

Although the rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was similar in all three groups, there was significantly less ototoxicity among patients who received the oral regimen, compared with control patients (2% vs. 9%); 4% of those taking the 6-month regimen had hearing loss, compared with 8% of control patients.

Exploratory analyses comparing both bedaquiline-containing regimens revealed a significantly higher proportion of favorable outcomes among participants receiving the 6-month regimen (91%), compared with patients taking the fully oral 9-month regimen (79%). There were no significant differences in the rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events.

The trial’s main limitation was its open-label design, which might have influenced decisions about treatment change, note the investigators.

“STREAM stage 2 has shown that two short-course, bedaquiline-containing regimens are not only non-inferior but superior to a 9-month injectable-containing regimen,” they conclude.

“The STREAM stage 2 fully oral regimen avoided the toxicity of aminoglycosides, and the 6-month regimen was highly effective, with reduced levels of ototoxicity. These two regimens offer promising treatment options for patients with MDR or rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis,” the authors write.

Dr. Goodall added, “Although both STREAM regimens were very effective, participants experienced relatively high levels of adverse events during the trial (though many of these were likely due to the close laboratory monitoring of the trial).

“While hearing loss was reduced on the 6-month regimen, it was not entirely eliminated,” she said. “Other new regimens in the field containing the medicine linezolid report side effects such as anemia and peripheral neuropathy. So more work needs to be done to ensure the treatment regimens are as safe and tolerable for patients as possible. In addition, even 6 months’ treatment is long for patients to tolerate, and further regimen shortening would be a welcome development for patients and health systems.”

‘A revolution in MDR tuberculosis’

“The authors must be commended on completing this challenging high-quality, phase 3, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial involving 13 health care facilities across Ethiopia, Georgia, India, Moldova, Mongolia, South Africa, and Uganda ... despite the COVID-19 pandemic,” noted Keertan Dheda, MD, PhD, and Christoph Lange, MD, PhD, in an accompanying comment titled, “A Revolution in the Management of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis”.

Although the WHO recently approved an all-oral 6-month bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid plus moxifloxacin (BPaLM) regimen, results from the alternate 6-month regimen examined in STREAM stage 2 “do provide confidence in using 2 months of an injectable as part of a salvage regimen in patients for whom MDR tuberculosis treatment is not successful” or in those with extensively drug-resistant (XDR) or pre-XDR TB, “for whom therapeutic options are few,” noted Dr. Dheda, from the University of Cape Town (South Africa) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Dr. Lange, from the University of Lübeck (Germany), Baylor College of Medicine, and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston.

The study authors and the commentators stress that safer and simpler treatments are still needed for MDR TB. “The search is now on for regimens that could further reduce duration, toxicity, and pill burden,” note Dr. Dheda and Dr. Lange.

However, they also note that “substantial resistance” to bedaquiline is already emerging. “Therefore, if we are to protect key drugs from becoming functionally redundant, drug-susceptibility testing capacity will need to be rapidly improved to minimize resistance amplification and onward disease transmission.”

The study was funded by USAID and Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Goodall has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Dheda has received funding from the EU and the South African Medical Research Council for studies related to the diagnosis or management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Dr. Lange is supported by the German Center for Infection Research and has received funding from the European Commission for studies on the development of novel antituberculosis medicines and for studies related to novel diagnostics of tuberculosis; consulting fees from INSMED; speaker’s fees from INSMED, GILEAD, and Janssen; and is a member of the data safety board of trials from Medicines sans Frontiers, all of which are unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two short-course bedaquiline-containing treatment regimens for rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis showed “robust evidence” for superior efficacy and less ototoxicity compared to a 9-month injectable control regimen, researchers report.

The findings validate the World Health Organization’s current recommendation of a 9-month, bedaquiline-based oral regimen, “which was based only on observational data,” noted lead author Ruth Goodall, PhD, from the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, and colleagues.

The study was published in The Lancet.

The Standard Treatment Regimen of Anti-tuberculosis Drugs for Patients With MDR-TB (STREAM) stage 2 study was a randomized, phase 3, noninferiority trial conducted at 13 hospital clinics in seven countries that had prespecified tests for superiority if noninferiority was shown. The study enrolled individuals aged 15 years or older who had rifampicin-resistant TB without fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside resistance.

The study’s first stage, STREAM stage 1, showed that The 9-month regimen was recommended by the WHO in 2016. That recommendation was superceded in 2020 when concerns of hearing loss associated with aminoglycosides prompted the WHO to endorse a 9-month bedaquiline-containing, injectable-free alternative, the authors write.

Seeking shorter treatment for better outcomes

STREAM stage 2 used a 9-month injectable regimen as its control. The investigators measured it against a fully oral 9-month bedaquiline-based treatment (primary comparison), as well as a 6-month oral bedaquiline regimen that included 8 weeks of a second-line injectable (secondary comparison).

The 9-month fully oral treatment included levofloxacin, clofazimine, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 40 weeks; bedaquiline, high-dose isoniazid, and prothionamide were given for the 16-week intensive phase.

The 6-month regimen included bedaquiline, clofazimine, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin for 28 weeks, supplemented by high-dose isoniazid with kanamycin for an 8-week intensive phase.

For both comparisons, the primary outcome was favorable status at 76 weeks, defined as cultures that were negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis without a preceding unfavorable outcome (defined as any death, bacteriologic failure or recurrence, or major treatment change).

Among 517 participants in the modified intention-to-treat population across the study groups, 62% were men, and 38% were women (median age, 32.5 years).

For the primary comparison, 71% of the control group and 83% of the oral regimen group had a favorable outcome.

In the secondary comparison, 69% had a favorable outcome in the control group, compared with 91% of those receiving the 6-month regimen.

Although the rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was similar in all three groups, there was significantly less ototoxicity among patients who received the oral regimen, compared with control patients (2% vs. 9%); 4% of those taking the 6-month regimen had hearing loss, compared with 8% of control patients.

Exploratory analyses comparing both bedaquiline-containing regimens revealed a significantly higher proportion of favorable outcomes among participants receiving the 6-month regimen (91%), compared with patients taking the fully oral 9-month regimen (79%). There were no significant differences in the rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events.

The trial’s main limitation was its open-label design, which might have influenced decisions about treatment change, note the investigators.

“STREAM stage 2 has shown that two short-course, bedaquiline-containing regimens are not only non-inferior but superior to a 9-month injectable-containing regimen,” they conclude.

“The STREAM stage 2 fully oral regimen avoided the toxicity of aminoglycosides, and the 6-month regimen was highly effective, with reduced levels of ototoxicity. These two regimens offer promising treatment options for patients with MDR or rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis,” the authors write.

Dr. Goodall added, “Although both STREAM regimens were very effective, participants experienced relatively high levels of adverse events during the trial (though many of these were likely due to the close laboratory monitoring of the trial).

“While hearing loss was reduced on the 6-month regimen, it was not entirely eliminated,” she said. “Other new regimens in the field containing the medicine linezolid report side effects such as anemia and peripheral neuropathy. So more work needs to be done to ensure the treatment regimens are as safe and tolerable for patients as possible. In addition, even 6 months’ treatment is long for patients to tolerate, and further regimen shortening would be a welcome development for patients and health systems.”

‘A revolution in MDR tuberculosis’

“The authors must be commended on completing this challenging high-quality, phase 3, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial involving 13 health care facilities across Ethiopia, Georgia, India, Moldova, Mongolia, South Africa, and Uganda ... despite the COVID-19 pandemic,” noted Keertan Dheda, MD, PhD, and Christoph Lange, MD, PhD, in an accompanying comment titled, “A Revolution in the Management of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis”.

Although the WHO recently approved an all-oral 6-month bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid plus moxifloxacin (BPaLM) regimen, results from the alternate 6-month regimen examined in STREAM stage 2 “do provide confidence in using 2 months of an injectable as part of a salvage regimen in patients for whom MDR tuberculosis treatment is not successful” or in those with extensively drug-resistant (XDR) or pre-XDR TB, “for whom therapeutic options are few,” noted Dr. Dheda, from the University of Cape Town (South Africa) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Dr. Lange, from the University of Lübeck (Germany), Baylor College of Medicine, and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston.

The study authors and the commentators stress that safer and simpler treatments are still needed for MDR TB. “The search is now on for regimens that could further reduce duration, toxicity, and pill burden,” note Dr. Dheda and Dr. Lange.

However, they also note that “substantial resistance” to bedaquiline is already emerging. “Therefore, if we are to protect key drugs from becoming functionally redundant, drug-susceptibility testing capacity will need to be rapidly improved to minimize resistance amplification and onward disease transmission.”

The study was funded by USAID and Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Goodall has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Dheda has received funding from the EU and the South African Medical Research Council for studies related to the diagnosis or management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Dr. Lange is supported by the German Center for Infection Research and has received funding from the European Commission for studies on the development of novel antituberculosis medicines and for studies related to novel diagnostics of tuberculosis; consulting fees from INSMED; speaker’s fees from INSMED, GILEAD, and Janssen; and is a member of the data safety board of trials from Medicines sans Frontiers, all of which are unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More vaccinated people dying of COVID as fewer get booster shots

“We can no longer say this is a pandemic of the unvaccinated,” Kaiser Family Foundation Vice President Cynthia Cox, who conducted the analysis, told The Washington Post.

People who had been vaccinated or boosted made up 58% of COVID-19 deaths in August, the analysis showed. The rate has been on the rise: 23% of coronavirus deaths were among vaccinated people in September 2021, and the vaccinated made up 42% of deaths in January and February 2022, the Post reported.

Research continues to show that people who are vaccinated or boosted have a lower risk of death. The rise in deaths among the vaccinated is the result of three factors, Ms. Cox said.

- A large majority of people in the United States have been vaccinated (267 million people, the said).

- People who are at the greatest risk of dying from COVID-19 are more likely to be vaccinated and boosted, such as the elderly.

- Vaccines lose their effectiveness over time; the virus changes to avoid vaccines; and people need to choose to get boosters to continue to be protected.

The case for the effectiveness of vaccines and boosters versus skipping the shots remains strong. People age 6 months and older who are unvaccinated are six times more likely to die of COVID-19, compared to those who got the primary series of shots, the Post reported. Survival rates were even better with additional booster shots, particularly among older people.

“I feel very confident that if people continue to get vaccinated at good numbers, if people get boosted, we can absolutely have a very safe and healthy holiday season,” Ashish Jha, White House coronavirus czar, said on Nov. 22.

The number of Americans who have gotten the most recent booster has been increasing ahead of the holidays. CDC data show that 12% of the U.S. population age 5 and older has received a booster.

A new study by a team of researchers from Harvard University and Yale University estimates that 94% of the U.S. population has been infected with COVID-19 at least once, leaving just 1 in 20 people who have never had the virus.

“Despite these high exposure numbers, there is still substantial population susceptibility to infection with an Omicron variant,” the authors wrote.

They said that if all states achieved the vaccination levels of Vermont, where 55% of people had at least one booster and 22% got a second one, there would be “an appreciable improvement in population immunity, with greater relative impact for protection against infection versus severe disease. This additional protection results from both the recovery of immunity lost due to waning and the increased effectiveness of the bivalent booster against Omicron infections.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

“We can no longer say this is a pandemic of the unvaccinated,” Kaiser Family Foundation Vice President Cynthia Cox, who conducted the analysis, told The Washington Post.

People who had been vaccinated or boosted made up 58% of COVID-19 deaths in August, the analysis showed. The rate has been on the rise: 23% of coronavirus deaths were among vaccinated people in September 2021, and the vaccinated made up 42% of deaths in January and February 2022, the Post reported.

Research continues to show that people who are vaccinated or boosted have a lower risk of death. The rise in deaths among the vaccinated is the result of three factors, Ms. Cox said.

- A large majority of people in the United States have been vaccinated (267 million people, the said).

- People who are at the greatest risk of dying from COVID-19 are more likely to be vaccinated and boosted, such as the elderly.

- Vaccines lose their effectiveness over time; the virus changes to avoid vaccines; and people need to choose to get boosters to continue to be protected.

The case for the effectiveness of vaccines and boosters versus skipping the shots remains strong. People age 6 months and older who are unvaccinated are six times more likely to die of COVID-19, compared to those who got the primary series of shots, the Post reported. Survival rates were even better with additional booster shots, particularly among older people.

“I feel very confident that if people continue to get vaccinated at good numbers, if people get boosted, we can absolutely have a very safe and healthy holiday season,” Ashish Jha, White House coronavirus czar, said on Nov. 22.

The number of Americans who have gotten the most recent booster has been increasing ahead of the holidays. CDC data show that 12% of the U.S. population age 5 and older has received a booster.

A new study by a team of researchers from Harvard University and Yale University estimates that 94% of the U.S. population has been infected with COVID-19 at least once, leaving just 1 in 20 people who have never had the virus.

“Despite these high exposure numbers, there is still substantial population susceptibility to infection with an Omicron variant,” the authors wrote.

They said that if all states achieved the vaccination levels of Vermont, where 55% of people had at least one booster and 22% got a second one, there would be “an appreciable improvement in population immunity, with greater relative impact for protection against infection versus severe disease. This additional protection results from both the recovery of immunity lost due to waning and the increased effectiveness of the bivalent booster against Omicron infections.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

“We can no longer say this is a pandemic of the unvaccinated,” Kaiser Family Foundation Vice President Cynthia Cox, who conducted the analysis, told The Washington Post.

People who had been vaccinated or boosted made up 58% of COVID-19 deaths in August, the analysis showed. The rate has been on the rise: 23% of coronavirus deaths were among vaccinated people in September 2021, and the vaccinated made up 42% of deaths in January and February 2022, the Post reported.

Research continues to show that people who are vaccinated or boosted have a lower risk of death. The rise in deaths among the vaccinated is the result of three factors, Ms. Cox said.

- A large majority of people in the United States have been vaccinated (267 million people, the said).

- People who are at the greatest risk of dying from COVID-19 are more likely to be vaccinated and boosted, such as the elderly.

- Vaccines lose their effectiveness over time; the virus changes to avoid vaccines; and people need to choose to get boosters to continue to be protected.

The case for the effectiveness of vaccines and boosters versus skipping the shots remains strong. People age 6 months and older who are unvaccinated are six times more likely to die of COVID-19, compared to those who got the primary series of shots, the Post reported. Survival rates were even better with additional booster shots, particularly among older people.

“I feel very confident that if people continue to get vaccinated at good numbers, if people get boosted, we can absolutely have a very safe and healthy holiday season,” Ashish Jha, White House coronavirus czar, said on Nov. 22.

The number of Americans who have gotten the most recent booster has been increasing ahead of the holidays. CDC data show that 12% of the U.S. population age 5 and older has received a booster.

A new study by a team of researchers from Harvard University and Yale University estimates that 94% of the U.S. population has been infected with COVID-19 at least once, leaving just 1 in 20 people who have never had the virus.

“Despite these high exposure numbers, there is still substantial population susceptibility to infection with an Omicron variant,” the authors wrote.

They said that if all states achieved the vaccination levels of Vermont, where 55% of people had at least one booster and 22% got a second one, there would be “an appreciable improvement in population immunity, with greater relative impact for protection against infection versus severe disease. This additional protection results from both the recovery of immunity lost due to waning and the increased effectiveness of the bivalent booster against Omicron infections.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Don’t call me ‘Dr.,’ say some physicians – but most prefer the title

When Mark Cucuzzella, MD, meets a new patient at the West Virginia Medical School clinic, he introduces himself as “Mark.” For one thing, says Dr. Cucuzzella, his last name is a mouthful. For another, the 56-year-old general practitioner asserts that getting on a first-name basis with his patients is integral to delivering the best care.

“I’m trying to break down the old paternalistic barriers of the doctor/patient relationship,” he says. “Titles create an environment where the doctors are making all the decisions and not involving the patient in any course of action.”

Aniruddh Setya, MD, has a different take on informality between patients and doctors: It’s not OK. “I am not your friend,” says the 35-year-old pediatrician from Florida-based KIDZ Medical Services. “There has to be a level of respect for the education and accomplishment of being a physician.”

published in JAMA Network Open. But that doesn’t mean most physicians support the practice. In fact, some doctors contend that it can be harmful, particularly to female physicians.

“My concern is that untitling (so termed by Amy Diehl, PhD, and Leanne Dzubinski, PhD) intrudes upon important professional boundaries and might be correlated with diminishing the value of someone’s time,” says Leah Witt, MD, a geriatrician at UCSF Health, San Francisco. Dr. Witt, along with colleague Lekshmi Santhosh, MD, a pulmonologist, offered commentary on the study results. “Studies have shown that women physicians get more patient portal messages, spend more time in the electronic health record, and have longer visits,” Dr. Witt said. “Dr. Santhosh and I wonder if untitling is a signifier of this diminished value of our time, and an assumption of increased ease of access leading to this higher workload.”

To compile the results reported in JAMA Network Open, Mayo Clinic researchers analyzed more than 90,000 emails from patients to doctors over the course of 3 years, beginning in 2018. Of those emails, more than 32% included the physician’s first name in greeting or salutation. For women physicians, the odds were twice as high that their titles would be omitted in the correspondence. The same holds true for doctors of osteopathic medicine (DOs) compared with MDs, and primary care physicians had similar odds for a title drop compared with specialists.

Dr. Witt says the findings are not surprising. “They match my experience as a woman in medicine, as Dr. Santhosh and I write in our commentary,” she says. “We think the findings could easily be replicated at other centers.”

Indeed, research on 321 speaker introductions at a medical rounds found that when female physicians introduced other physicians, they usually applied the doctor title. When the job of introducing colleagues fell to male physicians, however, the stats fell to 72.4% for male peers and only 49.2% when introducing female peers.

The Mayo Clinic study authors identified the pitfalls of patients who informally address their doctors. They wrote, “Untitling may have a negative impact on physicians, demonstrate lack of respect, and can lead to reduction in formality of the physician/patient relationship or workplace.”

Physician preferences vary

Although the results of the Mayo Clinic analysis didn’t and couldn’t address physician sentiments on patient informality, Dr. Setya observes that American culture is becoming less formal. “I’ve been practicing for over 10 years, and the number of people who consider doctors as equals is growing,” he says. “This has been particularly true over the last couple of years.”

This change was documented in 2015. Add in the pandemic and an entire society that is now accustomed to working from home in sweats, and it’s not a stretch to understand why some patients have become less formal in many settings. The 2015 article noted, however, that most physicians prefer to keep titles in the mix.