User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Specialty and age may contribute to suicidal thoughts among physicians

A physician’s specialty can make a difference when it comes to having suicidal thoughts. Doctors who specialize in family medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, and psychiatry reported double the rates of suicidal thoughts than doctors in oncology, rheumatology, and pulmonary medicine, according to Doctors’ Burden: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2023.

“The specialties with the highest reporting of physician suicidal thoughts are also those with the greatest physician shortages, based on the number of job openings posted by recruiting sites,” said Peter Yellowlees, MD, professor of psychiatry and chief wellness officer at UC Davis Health.

Doctors in those specialties are overworked, which can lead to burnout, he said.

There’s also a generational divide among physicians who reported suicidal thoughts. Millennials (age 27-41) and Gen-X physicians (age 42-56) were more likely to report these thoughts than were Baby Boomers (age 57-75) and the Silent Generation (age 76-95).

“Younger physicians are more burned out – they may have less control over their lives and less meaning than some older doctors who can do what they want,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

One millennial respondent commented that being on call and being required to chart detailed notes in the EHR has contributed to her burnout. “I’m more impatient and make less time and effort to see my friends and family.”

One Silent Generation respondent commented, “I am semi-retired, I take no call, I work no weekends, I provide anesthesia care in my area of special expertise, I work clinically about 46 days a year. Life is good, particularly compared to my younger colleagues who are working 60-plus hours a week with evening work, weekend work, and call. I feel really sorry for them.”

When young people enter medical school, they’re quite healthy, with low rates of depression and burnout, said Dr. Yellowlees. Yet, studies have shown that rates of burnout and suicidal thoughts increased within 2 years. “That reflects what happens when a group of idealistic young people hit a horrible system,” he said.

Who’s responsible?

Millennials were three times as likely as baby boomers to say that a medical school or health care organization should be responsible when a student or physician commits suicide.

“Young physicians may expect more of their employers than my generation did, which we see in residency programs that have unionized,” said Dr. Yellowlees, a Baby Boomer.

“As more young doctors are employed by health care organizations, they also may expect more resources to be available to them, such as wellness programs,” he added.

Younger doctors also focus more on work-life balance than older doctors, including time off and having hobbies, he said. “They are much more rational in terms of their overall beliefs and expectations than the older generation.”

Whom doctors confide in

Nearly 60% of physician-respondents with suicidal thoughts said they confided in a professional or someone they knew. Men were just as likely as women to reach out to a therapist (38%), whereas men were slightly more likely to confide in a family member and women were slightly more likely to confide in a colleague.

“It’s interesting that women are more active in seeking support at work – they often have developed a network of colleagues to support each other’s careers and whom they can confide in,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

He emphasized that 40% of physicians said they didn’t confide in anyone when they had suicidal thoughts. Of those, just over half said they could cope without professional help.

One respondent commented, “It’s just a thought; nothing I would actually do.” Another commented, “Mental health professionals can’t fix the underlying reason for the problem.”

Many doctors were concerned about risking disclosure to their medical boards (42%); that it would show up on their insurance records (33%); and that their colleagues would find out (25%), according to the report.

One respondent commented, “I don’t trust doctors to keep it to themselves.”

Another barrier doctors mentioned was a lack of time to seek help. One commented, “Time. I have none, when am I supposed to find an hour for counseling?”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A physician’s specialty can make a difference when it comes to having suicidal thoughts. Doctors who specialize in family medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, and psychiatry reported double the rates of suicidal thoughts than doctors in oncology, rheumatology, and pulmonary medicine, according to Doctors’ Burden: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2023.

“The specialties with the highest reporting of physician suicidal thoughts are also those with the greatest physician shortages, based on the number of job openings posted by recruiting sites,” said Peter Yellowlees, MD, professor of psychiatry and chief wellness officer at UC Davis Health.

Doctors in those specialties are overworked, which can lead to burnout, he said.

There’s also a generational divide among physicians who reported suicidal thoughts. Millennials (age 27-41) and Gen-X physicians (age 42-56) were more likely to report these thoughts than were Baby Boomers (age 57-75) and the Silent Generation (age 76-95).

“Younger physicians are more burned out – they may have less control over their lives and less meaning than some older doctors who can do what they want,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

One millennial respondent commented that being on call and being required to chart detailed notes in the EHR has contributed to her burnout. “I’m more impatient and make less time and effort to see my friends and family.”

One Silent Generation respondent commented, “I am semi-retired, I take no call, I work no weekends, I provide anesthesia care in my area of special expertise, I work clinically about 46 days a year. Life is good, particularly compared to my younger colleagues who are working 60-plus hours a week with evening work, weekend work, and call. I feel really sorry for them.”

When young people enter medical school, they’re quite healthy, with low rates of depression and burnout, said Dr. Yellowlees. Yet, studies have shown that rates of burnout and suicidal thoughts increased within 2 years. “That reflects what happens when a group of idealistic young people hit a horrible system,” he said.

Who’s responsible?

Millennials were three times as likely as baby boomers to say that a medical school or health care organization should be responsible when a student or physician commits suicide.

“Young physicians may expect more of their employers than my generation did, which we see in residency programs that have unionized,” said Dr. Yellowlees, a Baby Boomer.

“As more young doctors are employed by health care organizations, they also may expect more resources to be available to them, such as wellness programs,” he added.

Younger doctors also focus more on work-life balance than older doctors, including time off and having hobbies, he said. “They are much more rational in terms of their overall beliefs and expectations than the older generation.”

Whom doctors confide in

Nearly 60% of physician-respondents with suicidal thoughts said they confided in a professional or someone they knew. Men were just as likely as women to reach out to a therapist (38%), whereas men were slightly more likely to confide in a family member and women were slightly more likely to confide in a colleague.

“It’s interesting that women are more active in seeking support at work – they often have developed a network of colleagues to support each other’s careers and whom they can confide in,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

He emphasized that 40% of physicians said they didn’t confide in anyone when they had suicidal thoughts. Of those, just over half said they could cope without professional help.

One respondent commented, “It’s just a thought; nothing I would actually do.” Another commented, “Mental health professionals can’t fix the underlying reason for the problem.”

Many doctors were concerned about risking disclosure to their medical boards (42%); that it would show up on their insurance records (33%); and that their colleagues would find out (25%), according to the report.

One respondent commented, “I don’t trust doctors to keep it to themselves.”

Another barrier doctors mentioned was a lack of time to seek help. One commented, “Time. I have none, when am I supposed to find an hour for counseling?”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A physician’s specialty can make a difference when it comes to having suicidal thoughts. Doctors who specialize in family medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, and psychiatry reported double the rates of suicidal thoughts than doctors in oncology, rheumatology, and pulmonary medicine, according to Doctors’ Burden: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2023.

“The specialties with the highest reporting of physician suicidal thoughts are also those with the greatest physician shortages, based on the number of job openings posted by recruiting sites,” said Peter Yellowlees, MD, professor of psychiatry and chief wellness officer at UC Davis Health.

Doctors in those specialties are overworked, which can lead to burnout, he said.

There’s also a generational divide among physicians who reported suicidal thoughts. Millennials (age 27-41) and Gen-X physicians (age 42-56) were more likely to report these thoughts than were Baby Boomers (age 57-75) and the Silent Generation (age 76-95).

“Younger physicians are more burned out – they may have less control over their lives and less meaning than some older doctors who can do what they want,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

One millennial respondent commented that being on call and being required to chart detailed notes in the EHR has contributed to her burnout. “I’m more impatient and make less time and effort to see my friends and family.”

One Silent Generation respondent commented, “I am semi-retired, I take no call, I work no weekends, I provide anesthesia care in my area of special expertise, I work clinically about 46 days a year. Life is good, particularly compared to my younger colleagues who are working 60-plus hours a week with evening work, weekend work, and call. I feel really sorry for them.”

When young people enter medical school, they’re quite healthy, with low rates of depression and burnout, said Dr. Yellowlees. Yet, studies have shown that rates of burnout and suicidal thoughts increased within 2 years. “That reflects what happens when a group of idealistic young people hit a horrible system,” he said.

Who’s responsible?

Millennials were three times as likely as baby boomers to say that a medical school or health care organization should be responsible when a student or physician commits suicide.

“Young physicians may expect more of their employers than my generation did, which we see in residency programs that have unionized,” said Dr. Yellowlees, a Baby Boomer.

“As more young doctors are employed by health care organizations, they also may expect more resources to be available to them, such as wellness programs,” he added.

Younger doctors also focus more on work-life balance than older doctors, including time off and having hobbies, he said. “They are much more rational in terms of their overall beliefs and expectations than the older generation.”

Whom doctors confide in

Nearly 60% of physician-respondents with suicidal thoughts said they confided in a professional or someone they knew. Men were just as likely as women to reach out to a therapist (38%), whereas men were slightly more likely to confide in a family member and women were slightly more likely to confide in a colleague.

“It’s interesting that women are more active in seeking support at work – they often have developed a network of colleagues to support each other’s careers and whom they can confide in,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

He emphasized that 40% of physicians said they didn’t confide in anyone when they had suicidal thoughts. Of those, just over half said they could cope without professional help.

One respondent commented, “It’s just a thought; nothing I would actually do.” Another commented, “Mental health professionals can’t fix the underlying reason for the problem.”

Many doctors were concerned about risking disclosure to their medical boards (42%); that it would show up on their insurance records (33%); and that their colleagues would find out (25%), according to the report.

One respondent commented, “I don’t trust doctors to keep it to themselves.”

Another barrier doctors mentioned was a lack of time to seek help. One commented, “Time. I have none, when am I supposed to find an hour for counseling?”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary function may predict frailty

Pulmonary function was significantly associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults over a 5-year period, as indicated by data from more than 1,000 individuals.

The pulmonary function test has been proposed as a predictive tool for clinical outcomes in geriatrics, including hospitalization, mortality, and frailty, but , write Walter Sepulveda-Loyola, MD, of Universidad de Las Americas, Santiago, Chile, and colleagues.

In an observational study published in Heart and Lung, the researchers reviewed data from adults older than 64 years who were participants in the Toledo Study for Healthy Aging.

The study population included 1,188 older adults (mean age, 74 years; 54% women). The prevalence of frailty at baseline ranged from 7% to 26%.

Frailty was defined using the frailty phenotype (FP) and the Frailty Trait Scale 5 (FTS5). Pulmonary function was determined on the basis of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), using spirometry.

Overall, at the 5-year follow-up, FEV1 and FVC were inversely associated with prevalence and incidence of frailty in nonadjusted and adjusted models using FP and FTS5.

In adjusted models, FEV1 and FVC, as well as FEV1 and FVC percent predicted value, were significantly associated with the prevalence of frailty, with odds ratios ranging from 0.53 to 0.99. FEV1 and FVC were significantly associated with increased incidence of frailty, with odds ratios ranging from 0.49 to 0.50 (P < .05 for both).

Pulmonary function also was associated with prevalent and incident frailty, hospitalization, and mortality in regression models, including the whole sample and after respiratory diseases were excluded.

Pulmonary function measures below the cutoff points for FEV1 and FVC were significantly associated with frailty, as well as with hospitalization and mortality. The cutoff points for FEV1 were 1.805 L for men and 1.165 L for women; cutoff points for FVC were 2.385 L for men and 1.585 L for women.

“Pulmonary function should be evaluated not only in frail patients, with the aim of detecting patients with poor prognoses regardless of their comorbidity, but also in individuals who are not frail but have an increased risk of developing frailty, as well as other adverse events,” the researchers write.

The study findings were limited by lack of data on pulmonary function variables outside of spirometry and by the need for data from populations with different characteristics to assess whether the same cutoff points are predictive of frailty, the researchers note.

The results were strengthened by the large sample size and additional analysis that excluded other respiratory diseases. Future research should consider adding pulmonary function assessment to the frailty model, the authors write.

Given the relationship between pulmonary function and physical capacity, the current study supports more frequent evaluation of pulmonary function in clinical practice for older adults, including those with no pulmonary disease, they conclude.

The study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness, financed by the European Regional Development Funds, and the Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red en Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable and the Fundacion Francisco Soria Melguizo. Lead author Dr. Sepulveda-Loyola was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary function was significantly associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults over a 5-year period, as indicated by data from more than 1,000 individuals.

The pulmonary function test has been proposed as a predictive tool for clinical outcomes in geriatrics, including hospitalization, mortality, and frailty, but , write Walter Sepulveda-Loyola, MD, of Universidad de Las Americas, Santiago, Chile, and colleagues.

In an observational study published in Heart and Lung, the researchers reviewed data from adults older than 64 years who were participants in the Toledo Study for Healthy Aging.

The study population included 1,188 older adults (mean age, 74 years; 54% women). The prevalence of frailty at baseline ranged from 7% to 26%.

Frailty was defined using the frailty phenotype (FP) and the Frailty Trait Scale 5 (FTS5). Pulmonary function was determined on the basis of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), using spirometry.

Overall, at the 5-year follow-up, FEV1 and FVC were inversely associated with prevalence and incidence of frailty in nonadjusted and adjusted models using FP and FTS5.

In adjusted models, FEV1 and FVC, as well as FEV1 and FVC percent predicted value, were significantly associated with the prevalence of frailty, with odds ratios ranging from 0.53 to 0.99. FEV1 and FVC were significantly associated with increased incidence of frailty, with odds ratios ranging from 0.49 to 0.50 (P < .05 for both).

Pulmonary function also was associated with prevalent and incident frailty, hospitalization, and mortality in regression models, including the whole sample and after respiratory diseases were excluded.

Pulmonary function measures below the cutoff points for FEV1 and FVC were significantly associated with frailty, as well as with hospitalization and mortality. The cutoff points for FEV1 were 1.805 L for men and 1.165 L for women; cutoff points for FVC were 2.385 L for men and 1.585 L for women.

“Pulmonary function should be evaluated not only in frail patients, with the aim of detecting patients with poor prognoses regardless of their comorbidity, but also in individuals who are not frail but have an increased risk of developing frailty, as well as other adverse events,” the researchers write.

The study findings were limited by lack of data on pulmonary function variables outside of spirometry and by the need for data from populations with different characteristics to assess whether the same cutoff points are predictive of frailty, the researchers note.

The results were strengthened by the large sample size and additional analysis that excluded other respiratory diseases. Future research should consider adding pulmonary function assessment to the frailty model, the authors write.

Given the relationship between pulmonary function and physical capacity, the current study supports more frequent evaluation of pulmonary function in clinical practice for older adults, including those with no pulmonary disease, they conclude.

The study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness, financed by the European Regional Development Funds, and the Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red en Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable and the Fundacion Francisco Soria Melguizo. Lead author Dr. Sepulveda-Loyola was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary function was significantly associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults over a 5-year period, as indicated by data from more than 1,000 individuals.

The pulmonary function test has been proposed as a predictive tool for clinical outcomes in geriatrics, including hospitalization, mortality, and frailty, but , write Walter Sepulveda-Loyola, MD, of Universidad de Las Americas, Santiago, Chile, and colleagues.

In an observational study published in Heart and Lung, the researchers reviewed data from adults older than 64 years who were participants in the Toledo Study for Healthy Aging.

The study population included 1,188 older adults (mean age, 74 years; 54% women). The prevalence of frailty at baseline ranged from 7% to 26%.

Frailty was defined using the frailty phenotype (FP) and the Frailty Trait Scale 5 (FTS5). Pulmonary function was determined on the basis of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), using spirometry.

Overall, at the 5-year follow-up, FEV1 and FVC were inversely associated with prevalence and incidence of frailty in nonadjusted and adjusted models using FP and FTS5.

In adjusted models, FEV1 and FVC, as well as FEV1 and FVC percent predicted value, were significantly associated with the prevalence of frailty, with odds ratios ranging from 0.53 to 0.99. FEV1 and FVC were significantly associated with increased incidence of frailty, with odds ratios ranging from 0.49 to 0.50 (P < .05 for both).

Pulmonary function also was associated with prevalent and incident frailty, hospitalization, and mortality in regression models, including the whole sample and after respiratory diseases were excluded.

Pulmonary function measures below the cutoff points for FEV1 and FVC were significantly associated with frailty, as well as with hospitalization and mortality. The cutoff points for FEV1 were 1.805 L for men and 1.165 L for women; cutoff points for FVC were 2.385 L for men and 1.585 L for women.

“Pulmonary function should be evaluated not only in frail patients, with the aim of detecting patients with poor prognoses regardless of their comorbidity, but also in individuals who are not frail but have an increased risk of developing frailty, as well as other adverse events,” the researchers write.

The study findings were limited by lack of data on pulmonary function variables outside of spirometry and by the need for data from populations with different characteristics to assess whether the same cutoff points are predictive of frailty, the researchers note.

The results were strengthened by the large sample size and additional analysis that excluded other respiratory diseases. Future research should consider adding pulmonary function assessment to the frailty model, the authors write.

Given the relationship between pulmonary function and physical capacity, the current study supports more frequent evaluation of pulmonary function in clinical practice for older adults, including those with no pulmonary disease, they conclude.

The study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness, financed by the European Regional Development Funds, and the Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red en Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable and the Fundacion Francisco Soria Melguizo. Lead author Dr. Sepulveda-Loyola was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Childhood nightmares a prelude to cognitive problems, Parkinson’s?

new research shows.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams between ages 7 and 11 years, those who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment and roughly seven times more likely to develop PD by age 50 years.

It’s been shown previously that sleep problems in adulthood, including distressing dreams, can precede the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or PD by several years, and in some cases decades, study investigator Abidemi Otaiku, BMBS, University of Birmingham (England), told this news organization.

However, no studies have investigated whether distressing dreams during childhood might also be associated with increased risk for cognitive decline or PD.

“As such, these findings provide evidence for the first time that certain sleep problems in childhood (having regular distressing dreams) could be an early indicator of increased dementia and PD risk,” Dr. Otaiku said.

He noted that the findings build on previous studies which showed that regular nightmares in childhood could be an early indicator for psychiatric problems in adolescence, such as borderline personality disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and psychosis.

The study was published online February 26 in The Lancet journal eClinicalMedicine.

Statistically significant

The prospective, longitudinal analysis used data from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study, a prospective birth cohort which included all people born in Britain during a single week in 1958.

At age 7 years (in 1965) and 11 years (in 1969), mothers were asked to report whether their child experienced “bad dreams or night terrors” in the past 3 months, and cognitive impairment and PD were determined at age 50 (2008).

Among a total of 6,991 children (51% girls), 78.2% never had distressing dreams, 17.9% had transient distressing dreams (either at ages 7 or 11 years), and 3.8% had persistent distressing dreams (at both ages 7 and 11 years).

By age 50, 262 participants had developed cognitive impairment, and five had been diagnosed with PD.

After adjusting for all covariates, having more regular distressing dreams during childhood was “linearly and statistically significantly” associated with higher risk of developing cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 years (P = .037). This was the case in both boys and girls.

Compared with children who never had bad dreams, peers who had persistent distressing dreams (at ages 7 and 11 years) had an 85% increased risk for cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-3.11; P = .019).

The associations remained when incident cognitive impairment and incident PD were analyzed separately.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams, children who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment by age 50 years (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.03-2.99; P = .037), and were about seven times more likely to be diagnosed with PD by age 50 years (aOR, 7.35; 95% CI, 1.03-52.73; P = .047).

The linear association was statistically significant for PD (P = .050) and had a trend toward statistical significance for cognitive impairment (P = .074).

Mechanism unclear

“Early-life nightmares might be causally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, noncausally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, or both. At this stage it remains unclear which of the three options is correct. Therefore, further research on mechanisms is needed,” Dr. Otaiku told this news organization.

“One plausible noncausal explanation is that there are shared genetic factors which predispose individuals to having frequent nightmares in childhood, and to developing neurodegenerative diseases such as AD or PD in adulthood,” he added.

It’s also plausible that having regular nightmares throughout childhood could be a causal risk factor for cognitive impairment and PD by causing chronic sleep disruption, he noted.

“Chronic sleep disruption due to nightmares might lead to impaired glymphatic clearance during sleep – and thus greater accumulation of pathological proteins in the brain, such as amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein,” Dr. Otaiku said.

Disrupted sleep throughout childhood might also impair normal brain development, which could make children’s brains less resilient to neuropathologic damage, he said.

Clinical implications?

There are established treatments for childhood nightmares, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

“For children who have regular nightmares that lead to impaired daytime functioning, it may well be a good idea for them to see a sleep physician to discuss whether treatment may be needed,” Dr. Otaiku said.

But should doctors treat children with persistent nightmares for the purpose of preventing neurodegenerative diseases in adulthood or psychiatric problems in adolescence?

“It’s an interesting possibility. However, more research is needed to confirm these epidemiological associations and to determine whether or not nightmares are a causal risk factor for these conditions,” Dr. Otaiku concluded.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Otaiku reports no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams between ages 7 and 11 years, those who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment and roughly seven times more likely to develop PD by age 50 years.

It’s been shown previously that sleep problems in adulthood, including distressing dreams, can precede the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or PD by several years, and in some cases decades, study investigator Abidemi Otaiku, BMBS, University of Birmingham (England), told this news organization.

However, no studies have investigated whether distressing dreams during childhood might also be associated with increased risk for cognitive decline or PD.

“As such, these findings provide evidence for the first time that certain sleep problems in childhood (having regular distressing dreams) could be an early indicator of increased dementia and PD risk,” Dr. Otaiku said.

He noted that the findings build on previous studies which showed that regular nightmares in childhood could be an early indicator for psychiatric problems in adolescence, such as borderline personality disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and psychosis.

The study was published online February 26 in The Lancet journal eClinicalMedicine.

Statistically significant

The prospective, longitudinal analysis used data from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study, a prospective birth cohort which included all people born in Britain during a single week in 1958.

At age 7 years (in 1965) and 11 years (in 1969), mothers were asked to report whether their child experienced “bad dreams or night terrors” in the past 3 months, and cognitive impairment and PD were determined at age 50 (2008).

Among a total of 6,991 children (51% girls), 78.2% never had distressing dreams, 17.9% had transient distressing dreams (either at ages 7 or 11 years), and 3.8% had persistent distressing dreams (at both ages 7 and 11 years).

By age 50, 262 participants had developed cognitive impairment, and five had been diagnosed with PD.

After adjusting for all covariates, having more regular distressing dreams during childhood was “linearly and statistically significantly” associated with higher risk of developing cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 years (P = .037). This was the case in both boys and girls.

Compared with children who never had bad dreams, peers who had persistent distressing dreams (at ages 7 and 11 years) had an 85% increased risk for cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-3.11; P = .019).

The associations remained when incident cognitive impairment and incident PD were analyzed separately.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams, children who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment by age 50 years (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.03-2.99; P = .037), and were about seven times more likely to be diagnosed with PD by age 50 years (aOR, 7.35; 95% CI, 1.03-52.73; P = .047).

The linear association was statistically significant for PD (P = .050) and had a trend toward statistical significance for cognitive impairment (P = .074).

Mechanism unclear

“Early-life nightmares might be causally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, noncausally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, or both. At this stage it remains unclear which of the three options is correct. Therefore, further research on mechanisms is needed,” Dr. Otaiku told this news organization.

“One plausible noncausal explanation is that there are shared genetic factors which predispose individuals to having frequent nightmares in childhood, and to developing neurodegenerative diseases such as AD or PD in adulthood,” he added.

It’s also plausible that having regular nightmares throughout childhood could be a causal risk factor for cognitive impairment and PD by causing chronic sleep disruption, he noted.

“Chronic sleep disruption due to nightmares might lead to impaired glymphatic clearance during sleep – and thus greater accumulation of pathological proteins in the brain, such as amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein,” Dr. Otaiku said.

Disrupted sleep throughout childhood might also impair normal brain development, which could make children’s brains less resilient to neuropathologic damage, he said.

Clinical implications?

There are established treatments for childhood nightmares, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

“For children who have regular nightmares that lead to impaired daytime functioning, it may well be a good idea for them to see a sleep physician to discuss whether treatment may be needed,” Dr. Otaiku said.

But should doctors treat children with persistent nightmares for the purpose of preventing neurodegenerative diseases in adulthood or psychiatric problems in adolescence?

“It’s an interesting possibility. However, more research is needed to confirm these epidemiological associations and to determine whether or not nightmares are a causal risk factor for these conditions,” Dr. Otaiku concluded.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Otaiku reports no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams between ages 7 and 11 years, those who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment and roughly seven times more likely to develop PD by age 50 years.

It’s been shown previously that sleep problems in adulthood, including distressing dreams, can precede the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or PD by several years, and in some cases decades, study investigator Abidemi Otaiku, BMBS, University of Birmingham (England), told this news organization.

However, no studies have investigated whether distressing dreams during childhood might also be associated with increased risk for cognitive decline or PD.

“As such, these findings provide evidence for the first time that certain sleep problems in childhood (having regular distressing dreams) could be an early indicator of increased dementia and PD risk,” Dr. Otaiku said.

He noted that the findings build on previous studies which showed that regular nightmares in childhood could be an early indicator for psychiatric problems in adolescence, such as borderline personality disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and psychosis.

The study was published online February 26 in The Lancet journal eClinicalMedicine.

Statistically significant

The prospective, longitudinal analysis used data from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study, a prospective birth cohort which included all people born in Britain during a single week in 1958.

At age 7 years (in 1965) and 11 years (in 1969), mothers were asked to report whether their child experienced “bad dreams or night terrors” in the past 3 months, and cognitive impairment and PD were determined at age 50 (2008).

Among a total of 6,991 children (51% girls), 78.2% never had distressing dreams, 17.9% had transient distressing dreams (either at ages 7 or 11 years), and 3.8% had persistent distressing dreams (at both ages 7 and 11 years).

By age 50, 262 participants had developed cognitive impairment, and five had been diagnosed with PD.

After adjusting for all covariates, having more regular distressing dreams during childhood was “linearly and statistically significantly” associated with higher risk of developing cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 years (P = .037). This was the case in both boys and girls.

Compared with children who never had bad dreams, peers who had persistent distressing dreams (at ages 7 and 11 years) had an 85% increased risk for cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-3.11; P = .019).

The associations remained when incident cognitive impairment and incident PD were analyzed separately.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams, children who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment by age 50 years (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.03-2.99; P = .037), and were about seven times more likely to be diagnosed with PD by age 50 years (aOR, 7.35; 95% CI, 1.03-52.73; P = .047).

The linear association was statistically significant for PD (P = .050) and had a trend toward statistical significance for cognitive impairment (P = .074).

Mechanism unclear

“Early-life nightmares might be causally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, noncausally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, or both. At this stage it remains unclear which of the three options is correct. Therefore, further research on mechanisms is needed,” Dr. Otaiku told this news organization.

“One plausible noncausal explanation is that there are shared genetic factors which predispose individuals to having frequent nightmares in childhood, and to developing neurodegenerative diseases such as AD or PD in adulthood,” he added.

It’s also plausible that having regular nightmares throughout childhood could be a causal risk factor for cognitive impairment and PD by causing chronic sleep disruption, he noted.

“Chronic sleep disruption due to nightmares might lead to impaired glymphatic clearance during sleep – and thus greater accumulation of pathological proteins in the brain, such as amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein,” Dr. Otaiku said.

Disrupted sleep throughout childhood might also impair normal brain development, which could make children’s brains less resilient to neuropathologic damage, he said.

Clinical implications?

There are established treatments for childhood nightmares, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

“For children who have regular nightmares that lead to impaired daytime functioning, it may well be a good idea for them to see a sleep physician to discuss whether treatment may be needed,” Dr. Otaiku said.

But should doctors treat children with persistent nightmares for the purpose of preventing neurodegenerative diseases in adulthood or psychiatric problems in adolescence?

“It’s an interesting possibility. However, more research is needed to confirm these epidemiological associations and to determine whether or not nightmares are a causal risk factor for these conditions,” Dr. Otaiku concluded.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Otaiku reports no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ECLINICALMEDICINE

Even mild COVID is hard on the brain

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

OTC budesonide-formoterol for asthma could save lives, money

, according to a computer modeling study presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 2023 annual meeting in San Antonio.

Asthma affects 25 million people, about 1 in 13, in the United States. About 28% are uninsured or underinsured, and 70% have mild asthma. Many are using a $30 inhaled epinephrine product (Primatene Mist) – the only FDA-approved asthma inhaler available without a prescription, said Marcus Shaker, MD, MS, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, and clinician at Dartmouth Health Children’s, N.H.

A new version of Primatene Mist was reintroduced on the market in 2018 after the product was pulled for containing chlorofluorocarbons in 2011, but it is not recommended by professional medical societies because of safety concerns over epinephrine’s adverse effects, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure.

Drugs in its class (bronchodilators) have long been associated with a higher risk for death or near-death.

Meanwhile, research more than 2 decades ago linked regular use of low-dose inhaled corticosteroids with reduced risk for asthma death.

More recently, two large studies (SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) compared maintenance therapy with a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (budesonide) vs. on-demand treatment with an inhaler containing both a corticosteroid (budesonide) and a long-acting bronchodilator (formoterol).

“Using as-needed budesonide-formoterol led to outcomes that are almost as good as taking a maintenance budesonide dose every day,” said Dr. Shaker.

The Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines now recommend this approach – as-needed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus long-acting bronchodilators – for adults with mild asthma. In the United States, however, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute still suggests daily ICS plus quick-relief therapy as needed.

Dr. Shaker and colleagues used computer modeling to compare the cost-effectiveness of as-needed budesonide-formoterol vs. over-the-counter inhaled epinephrine in underinsured U.S. adults who were self-managing their mild asthma. The study randomly assigned these individuals into three groups: OTC inhaled epinephrine (current reality), OTC budesonide-formoterol (not yet available), or no OTC option. The model assumed that patients treated for an exacerbation were referred to a health care provider and started a regimen of ICS plus as-needed rescue therapy.

In this analysis, which has been submitted for publication, the OTC budesonide-formoterol strategy was associated with 12,495 fewer deaths, prevented nearly 14 million severe asthma exacerbations, and saved more than $68 billion. And “when we looked at OTC budesonide-formoterol vs. having no OTC option at all, budesonide-formoterol was similarly cost-effective,” said Dr. Shaker, who presented the results at an AAAAI oral abstract session.

The cost savings emerged even though in the United States asthma controller therapies (for example, fluticasone) cost about 10 times more than rescue therapies (for instance, salbutamol, OTC epinephrine).

Nevertheless, the results make sense. “If you’re using Primatene Mist, your health costs are predicted to be much greater because you’re going to be in the hospital more. Your asthma is not going to be well-controlled,” Thanai Pongdee, MD, an allergist-immunologist with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., told this news organization. “It’s not only the cost of your ER visit but also the cost of loss of work or school, and loss of daily productivity. There are all these associated costs.”

The analysis “is certainly something policy makers could take a look at,” he said.

He noted that current use of budesonide-formoterol is stymied by difficulties with insurance coverage. The difficulties stem from a mismatch between the updated recommendation for as-needed use and the description printed on the brand-name product (Symbicort).

“On the product label, it says Symbicort should be used on a daily basis,” Dr. Pongdee said. “But if a prescription comes through and says you’re going to use this ‘as needed,’ the health plan may say that’s not appropriate because that’s not on the product label.”

Given these access challenges with the all-in-one inhaler, other researchers have developed a workaround – asking patients to continue their usual care (that is, using a rescue inhaler as needed) but to also administer a controller medication after each rescue. When tested in Black and Latino patients with moderate to severe asthma, this easy strategy (patient activated reliever-triggered inhaled corticosteroid, or PARTICS) reduced severe asthma exacerbations about as well as the all-in-one inhaler.

If the all-in-one budesonide-formoterol does become available OTC, Dr. Shaker stressed that it “would not be a substitute for seeing an allergist and getting appropriate medical care and an evaluation and all the rest. But it’s better than the status quo. It’s the sort of thing where the perfect is not the enemy of the good,” he said.

Dr. Shaker is the AAAAI cochair of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters and serves as an editorial board member of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology in Practice. He is also an associate editor of the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Dr. Pongdee serves as an at-large director on the AAAAI board of directors. He receives grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline, and Mayo Clinic is a trial site for GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a computer modeling study presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 2023 annual meeting in San Antonio.

Asthma affects 25 million people, about 1 in 13, in the United States. About 28% are uninsured or underinsured, and 70% have mild asthma. Many are using a $30 inhaled epinephrine product (Primatene Mist) – the only FDA-approved asthma inhaler available without a prescription, said Marcus Shaker, MD, MS, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, and clinician at Dartmouth Health Children’s, N.H.

A new version of Primatene Mist was reintroduced on the market in 2018 after the product was pulled for containing chlorofluorocarbons in 2011, but it is not recommended by professional medical societies because of safety concerns over epinephrine’s adverse effects, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure.

Drugs in its class (bronchodilators) have long been associated with a higher risk for death or near-death.

Meanwhile, research more than 2 decades ago linked regular use of low-dose inhaled corticosteroids with reduced risk for asthma death.

More recently, two large studies (SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) compared maintenance therapy with a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (budesonide) vs. on-demand treatment with an inhaler containing both a corticosteroid (budesonide) and a long-acting bronchodilator (formoterol).

“Using as-needed budesonide-formoterol led to outcomes that are almost as good as taking a maintenance budesonide dose every day,” said Dr. Shaker.

The Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines now recommend this approach – as-needed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus long-acting bronchodilators – for adults with mild asthma. In the United States, however, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute still suggests daily ICS plus quick-relief therapy as needed.

Dr. Shaker and colleagues used computer modeling to compare the cost-effectiveness of as-needed budesonide-formoterol vs. over-the-counter inhaled epinephrine in underinsured U.S. adults who were self-managing their mild asthma. The study randomly assigned these individuals into three groups: OTC inhaled epinephrine (current reality), OTC budesonide-formoterol (not yet available), or no OTC option. The model assumed that patients treated for an exacerbation were referred to a health care provider and started a regimen of ICS plus as-needed rescue therapy.

In this analysis, which has been submitted for publication, the OTC budesonide-formoterol strategy was associated with 12,495 fewer deaths, prevented nearly 14 million severe asthma exacerbations, and saved more than $68 billion. And “when we looked at OTC budesonide-formoterol vs. having no OTC option at all, budesonide-formoterol was similarly cost-effective,” said Dr. Shaker, who presented the results at an AAAAI oral abstract session.

The cost savings emerged even though in the United States asthma controller therapies (for example, fluticasone) cost about 10 times more than rescue therapies (for instance, salbutamol, OTC epinephrine).

Nevertheless, the results make sense. “If you’re using Primatene Mist, your health costs are predicted to be much greater because you’re going to be in the hospital more. Your asthma is not going to be well-controlled,” Thanai Pongdee, MD, an allergist-immunologist with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., told this news organization. “It’s not only the cost of your ER visit but also the cost of loss of work or school, and loss of daily productivity. There are all these associated costs.”

The analysis “is certainly something policy makers could take a look at,” he said.

He noted that current use of budesonide-formoterol is stymied by difficulties with insurance coverage. The difficulties stem from a mismatch between the updated recommendation for as-needed use and the description printed on the brand-name product (Symbicort).

“On the product label, it says Symbicort should be used on a daily basis,” Dr. Pongdee said. “But if a prescription comes through and says you’re going to use this ‘as needed,’ the health plan may say that’s not appropriate because that’s not on the product label.”

Given these access challenges with the all-in-one inhaler, other researchers have developed a workaround – asking patients to continue their usual care (that is, using a rescue inhaler as needed) but to also administer a controller medication after each rescue. When tested in Black and Latino patients with moderate to severe asthma, this easy strategy (patient activated reliever-triggered inhaled corticosteroid, or PARTICS) reduced severe asthma exacerbations about as well as the all-in-one inhaler.

If the all-in-one budesonide-formoterol does become available OTC, Dr. Shaker stressed that it “would not be a substitute for seeing an allergist and getting appropriate medical care and an evaluation and all the rest. But it’s better than the status quo. It’s the sort of thing where the perfect is not the enemy of the good,” he said.

Dr. Shaker is the AAAAI cochair of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters and serves as an editorial board member of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology in Practice. He is also an associate editor of the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Dr. Pongdee serves as an at-large director on the AAAAI board of directors. He receives grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline, and Mayo Clinic is a trial site for GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a computer modeling study presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 2023 annual meeting in San Antonio.

Asthma affects 25 million people, about 1 in 13, in the United States. About 28% are uninsured or underinsured, and 70% have mild asthma. Many are using a $30 inhaled epinephrine product (Primatene Mist) – the only FDA-approved asthma inhaler available without a prescription, said Marcus Shaker, MD, MS, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, and clinician at Dartmouth Health Children’s, N.H.

A new version of Primatene Mist was reintroduced on the market in 2018 after the product was pulled for containing chlorofluorocarbons in 2011, but it is not recommended by professional medical societies because of safety concerns over epinephrine’s adverse effects, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure.

Drugs in its class (bronchodilators) have long been associated with a higher risk for death or near-death.

Meanwhile, research more than 2 decades ago linked regular use of low-dose inhaled corticosteroids with reduced risk for asthma death.

More recently, two large studies (SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) compared maintenance therapy with a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (budesonide) vs. on-demand treatment with an inhaler containing both a corticosteroid (budesonide) and a long-acting bronchodilator (formoterol).

“Using as-needed budesonide-formoterol led to outcomes that are almost as good as taking a maintenance budesonide dose every day,” said Dr. Shaker.

The Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines now recommend this approach – as-needed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus long-acting bronchodilators – for adults with mild asthma. In the United States, however, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute still suggests daily ICS plus quick-relief therapy as needed.

Dr. Shaker and colleagues used computer modeling to compare the cost-effectiveness of as-needed budesonide-formoterol vs. over-the-counter inhaled epinephrine in underinsured U.S. adults who were self-managing their mild asthma. The study randomly assigned these individuals into three groups: OTC inhaled epinephrine (current reality), OTC budesonide-formoterol (not yet available), or no OTC option. The model assumed that patients treated for an exacerbation were referred to a health care provider and started a regimen of ICS plus as-needed rescue therapy.

In this analysis, which has been submitted for publication, the OTC budesonide-formoterol strategy was associated with 12,495 fewer deaths, prevented nearly 14 million severe asthma exacerbations, and saved more than $68 billion. And “when we looked at OTC budesonide-formoterol vs. having no OTC option at all, budesonide-formoterol was similarly cost-effective,” said Dr. Shaker, who presented the results at an AAAAI oral abstract session.

The cost savings emerged even though in the United States asthma controller therapies (for example, fluticasone) cost about 10 times more than rescue therapies (for instance, salbutamol, OTC epinephrine).

Nevertheless, the results make sense. “If you’re using Primatene Mist, your health costs are predicted to be much greater because you’re going to be in the hospital more. Your asthma is not going to be well-controlled,” Thanai Pongdee, MD, an allergist-immunologist with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., told this news organization. “It’s not only the cost of your ER visit but also the cost of loss of work or school, and loss of daily productivity. There are all these associated costs.”

The analysis “is certainly something policy makers could take a look at,” he said.

He noted that current use of budesonide-formoterol is stymied by difficulties with insurance coverage. The difficulties stem from a mismatch between the updated recommendation for as-needed use and the description printed on the brand-name product (Symbicort).

“On the product label, it says Symbicort should be used on a daily basis,” Dr. Pongdee said. “But if a prescription comes through and says you’re going to use this ‘as needed,’ the health plan may say that’s not appropriate because that’s not on the product label.”

Given these access challenges with the all-in-one inhaler, other researchers have developed a workaround – asking patients to continue their usual care (that is, using a rescue inhaler as needed) but to also administer a controller medication after each rescue. When tested in Black and Latino patients with moderate to severe asthma, this easy strategy (patient activated reliever-triggered inhaled corticosteroid, or PARTICS) reduced severe asthma exacerbations about as well as the all-in-one inhaler.

If the all-in-one budesonide-formoterol does become available OTC, Dr. Shaker stressed that it “would not be a substitute for seeing an allergist and getting appropriate medical care and an evaluation and all the rest. But it’s better than the status quo. It’s the sort of thing where the perfect is not the enemy of the good,” he said.

Dr. Shaker is the AAAAI cochair of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters and serves as an editorial board member of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology in Practice. He is also an associate editor of the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Dr. Pongdee serves as an at-large director on the AAAAI board of directors. He receives grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline, and Mayo Clinic is a trial site for GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAAAI 2023

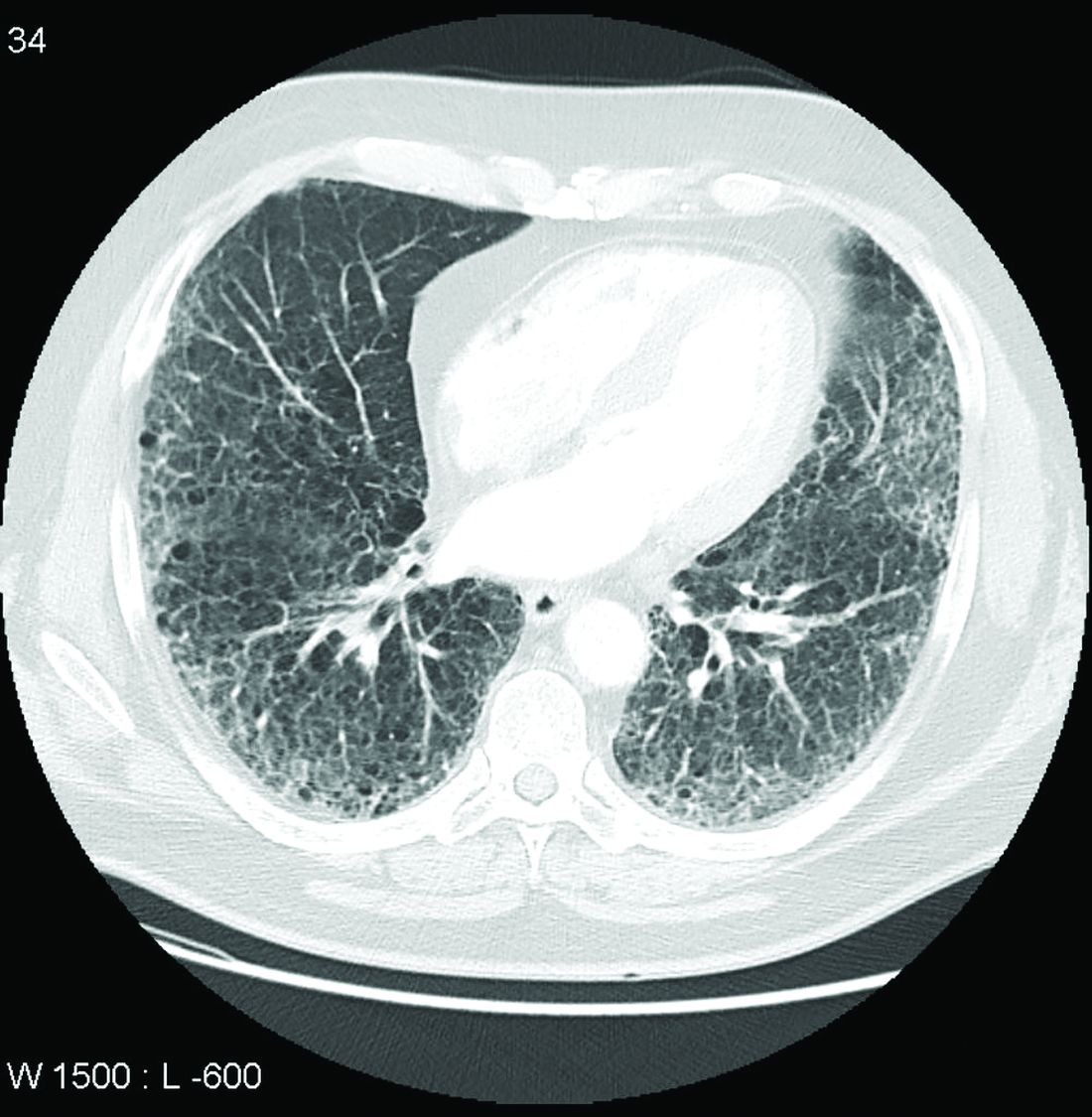

Call it preclinical or subclinical, ILD in RA needs to be tracked

More clinical guidance is needed for monitoring interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, according to a new commentary.

Though ILD is a leading cause of death among patients with RA, these patients are not routinely screened for ILD, the authors say, and there are currently no guidelines on how to monitor ILD progression in patients with RA.

“ILD associated with rheumatoid arthritis is a disease for which there’s been very little research done, so it’s an area of rheumatology where there are many unknowns,” lead author Elizabeth R. Volkmann, MD, who codirects the connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) program at University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The commentary was published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Defining disease

One of the major unknowns is how to define the disease, she said. RA patients sometimes undergo imaging for other medical reasons, and interstitial lung abnormalities are incidentally detected. These patients can be classified as having “preclinical” or “subclinical” ILD, as they do not yet have symptoms; however, there is no consensus as to what these terms mean, the commentary authors write. “The other problem that we have with these terms is that it sometimes creates the perception that this is a nonworrisome feature of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Volkmann said, although the condition should be followed closely.

“We know we can detect imaging features of ILD in people who may not yet have symptoms, and we need to know when to define a clinically important informality that requires follow-up or treatment,” added John M. Davis III, MD, a rheumatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He was not involved with the work.

Dr. Volkmann proposed eliminating the prefixes “pre” and “sub” when referring to ILD. “In other connective tissue diseases, like systemic sclerosis, for example, we can use the term ‘limited’ or ‘extensive’ ILD, based on the extent of involvement of the ILD on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) imaging,” she said. “This could potentially be something that is applied to how we classify patients with RA-ILD.”

Tracking ILD progression

Once ILD is identified, monitoring its progression poses challenges, as respiratory symptoms may be difficult to detect. RA patients may already be avoiding exercise because of joint pain, so they may not notice shortness of breath during physical activity, noted Jessica K. Gordon, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, in an interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the commentary. Cough is a potential symptom of ILD, but cough can also be the result of allergies, postnasal drip, or reflux, she said. Making the distinction between “preclinical” and symptomatic disease can be “complicated,” she added; “you may have to really dig.”

Additionally, there has been little research on the outcomes of patients with preclinical or subclinical ILD and clinical ILD, the commentary authors write. “It is therefore conceivable that some patients with rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed with preclinical or subclinical ILD could potentially have worse outcomes if both the rheumatoid arthritis and ILD are not monitored closely,” they note.

To better track RA-associated ILD for patients with and those without symptoms, the authors advocate for monitoring patients using pulmonary testing and CT scanning, as well as evaluating symptoms. How often these assessments should be conducted depends on the individual, they note. In her own practice, Dr. Volkmann sees patients every 3 months to evaluate their symptoms and conduct pulmonary function tests (PFTs). For patients early in the course of ILD, she orders HRCT imaging once per year.

For Dr. Davis, the frequency of follow-up depends on the severity of ILD. “For minimally symptomatic patients without compromised lung function, we would generally follow annually. For patients with symptomatic ILD on stable therapy, we may monitor every 6 months. For patients with active/progressive ILD, we would generally be following at least every 1-3 months,” he said.

Screening and future research

While there is no evidence to recommend screening patients for ILD using CT, there are certain risk factors for ILD in RA patients, including a history of smoking, male sex, and high RA disease activity despite antirheumatic treatment, Dr. Volkmann said. In both of their practices, Dr. Davis and Dr. Volkmann screen with RA via HRCT and PFTs for ILD for patients with known risk factors that predispose them to the lung condition and/or for patients who report respiratory symptoms.

“We still don’t have an algorithm [for screening patients], and that is a desperate need in this field,” added Joshua J. Solomon, MD, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health, Denver, whose research focuses on RA-associated ILD. While recommendations state that all patients with scleroderma should be screened with CT, ILD incidence is lower among patients with RA, and thus these screening recommendations need to be narrowed, he said. But more research is needed to better fine tune recommendations, he said; “The only thing you can do is give some expert consensus until there are good data.”

Dr. Volkmann has received consulting and speaking fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and institutional support for performing studies on systemic sclerosis for Kadmon, Forbius, Boehringer Ingelheim, Horizon, and Prometheus. Dr. Gordon, Dr. Davis, and Dr. Solomon report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More clinical guidance is needed for monitoring interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, according to a new commentary.

Though ILD is a leading cause of death among patients with RA, these patients are not routinely screened for ILD, the authors say, and there are currently no guidelines on how to monitor ILD progression in patients with RA.

“ILD associated with rheumatoid arthritis is a disease for which there’s been very little research done, so it’s an area of rheumatology where there are many unknowns,” lead author Elizabeth R. Volkmann, MD, who codirects the connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) program at University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The commentary was published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Defining disease

One of the major unknowns is how to define the disease, she said. RA patients sometimes undergo imaging for other medical reasons, and interstitial lung abnormalities are incidentally detected. These patients can be classified as having “preclinical” or “subclinical” ILD, as they do not yet have symptoms; however, there is no consensus as to what these terms mean, the commentary authors write. “The other problem that we have with these terms is that it sometimes creates the perception that this is a nonworrisome feature of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Volkmann said, although the condition should be followed closely.

“We know we can detect imaging features of ILD in people who may not yet have symptoms, and we need to know when to define a clinically important informality that requires follow-up or treatment,” added John M. Davis III, MD, a rheumatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He was not involved with the work.

Dr. Volkmann proposed eliminating the prefixes “pre” and “sub” when referring to ILD. “In other connective tissue diseases, like systemic sclerosis, for example, we can use the term ‘limited’ or ‘extensive’ ILD, based on the extent of involvement of the ILD on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) imaging,” she said. “This could potentially be something that is applied to how we classify patients with RA-ILD.”

Tracking ILD progression

Once ILD is identified, monitoring its progression poses challenges, as respiratory symptoms may be difficult to detect. RA patients may already be avoiding exercise because of joint pain, so they may not notice shortness of breath during physical activity, noted Jessica K. Gordon, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, in an interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the commentary. Cough is a potential symptom of ILD, but cough can also be the result of allergies, postnasal drip, or reflux, she said. Making the distinction between “preclinical” and symptomatic disease can be “complicated,” she added; “you may have to really dig.”

Additionally, there has been little research on the outcomes of patients with preclinical or subclinical ILD and clinical ILD, the commentary authors write. “It is therefore conceivable that some patients with rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed with preclinical or subclinical ILD could potentially have worse outcomes if both the rheumatoid arthritis and ILD are not monitored closely,” they note.