User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

For many, long COVID’s impacts go on and on, major study says

in the same time frame, a large study out of Scotland found.

Multiple studies are evaluating people with long COVID in the hopes of figuring out why some people experience debilitating symptoms long after their primary infection ends and others either do not or recover more quickly.

This current study is notable for its large size – 96,238 people. Researchers checked in with participants at 6, 12, and 18 months, and included a group of people never infected with the coronavirus to help investigators make a stronger case.

“A lot of the symptoms of long COVID are nonspecific and therefore can occur in people never infected,” says senior study author Jill P. Pell, MD, head of the School of Health and Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Ruling out coincidence

This study shows that people experienced a wide range of symptoms after becoming infected with COVID-19 at a significantly higher rate than those who were never infected, “thereby confirming that they were genuinely associated with COVID and not merely a coincidence,” she said.

Among 21,525 people who had COVID-19 and had symptoms, tiredness, headache and muscle aches or muscle weakness were the most common ongoing symptoms.

Loss of smell was almost nine times more likely in this group compared to the never-infected group in one analysis where researchers controlled for other possible factors. The risk for loss of taste was almost six times greater, followed by risk of breathlessness at three times higher.

Long COVID risk was highest after a severe original infection and among older people, women, Black, and South Asian populations, people with socioeconomic disadvantages, and those with more than one underlying health condition.

Adding up the 6% with no recovery after 18 months and 42% with partial recovery means that between 6 and 18 months following symptomatic coronavirus infection, almost half of those infected still experience persistent symptoms.

Vaccination validated

On the plus side, people vaccinated against COVID-19 before getting infected had a lower risk for some persistent symptoms. In addition, Dr. Pell and colleagues found no evidence that people who experienced asymptomatic infection were likely to experience long COVID symptoms or challenges with activities of daily living.

The findings of the Long-COVID in Scotland Study (Long-CISS) were published in the journal Nature Communications.

‘More long COVID than ever before’

“Unfortunately, these long COVID symptoms are not getting better as the cases of COVID get milder,” said Thomas Gut, DO, medical director for the post-COVID recovery program at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital. “Quite the opposite – this infection has become so common in a community because it’s so mild and spreading so rapidly that we’re seeing more long COVID symptoms than ever before.”

Although most patients he sees with long COVID resolve their symptoms within 3-6 months, “We do see some patients who require short-term disability because their symptoms continue past 6 months and out to 2 years,” said Dr. Gut, a hospitalist at Staten Island University Hospital, a member hospital of Northwell Health.

Patients with fatigue and neurocognitive symptoms “have a very tough time going back to work. Short-term disability gives them the time and finances to pursue specialty care with cardiology, pulmonary, and neurocognitive testing,” he said.

Support the whole person

The burden of living with long COVID goes beyond the persistent symptoms. “Long COVID can have wide-ranging impacts – not only on health but also quality of life and activities of daily living [including] work, mobility, self-care and more,” Dr. Pell said. “So, people with long COVID need support relevant to their individual needs and this may extend beyond the health care sector, for example including social services, school or workplace.”

Still, Lisa Penziner, RN, founder of the COVID Long Haulers Support Group in Westchester and Long Island, N.Y., said while people with the most severe cases of COVID-19 tended to have the worst long COVID symptoms, they’re not the only ones.

“We saw many post-COVID members who had mild cases and their long-haul symptoms were worse weeks later than the virus itself,” said Md. Penziner.

She estimates that 80%-90% of her support group members recover within 6 months. “However, there are others who were experiencing symptoms for much longer.”

Respiratory treatment, physical therapy, and other follow-up doctor visits are common after 6 months, for example.

“Additionally, there is a mental health component to recovery as well, meaning that the patient must learn to live while experiencing lingering, long-haul COVID symptoms in work and daily life,” said Ms. Penziner, director of special projects at North Westchester Restorative Therapy & Nursing.

In addition to ongoing medical care, people with long COVID need understanding, she said.

“While long-haul symptoms do not happen to everyone, it is proven that many do experience long-haul symptoms, and the support of the community in understanding is important.”

Limitations of the study

Dr. Pell and colleagues noted some strengths and weaknesses to their study. For example, “as a general population study, our findings provide a better indication of the overall risk and burden of long COVID than hospitalized cohorts,” they noted.

Also, the Scottish population is 96% White, so other long COVID studies with more diverse participants are warranted.

Another potential weakness is the response rate of 16% among those invited to participate in the study, which Dr. Pell and colleagues addressed: “Our cohort included a large sample (33,281) of people previously infected and the response rate of 16% overall and 20% among people who had symptomatic infection was consistent with previous studies that have used SMS text invitations as the sole method of recruitment.”

“We tell patients this should last 3-6 months, but some patients have longer recovery periods,” Dr. Gut said. “We’re here for them. We have a lot of services available to help get them through the recovery process, and we have a lot of options to help support them.”

“What we found most helpful is when there is peer-to-peer support, reaffirming to the member that they are not alone in the long-haul battle, which has been a major benefit of the support group,” Ms. Penziner said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

in the same time frame, a large study out of Scotland found.

Multiple studies are evaluating people with long COVID in the hopes of figuring out why some people experience debilitating symptoms long after their primary infection ends and others either do not or recover more quickly.

This current study is notable for its large size – 96,238 people. Researchers checked in with participants at 6, 12, and 18 months, and included a group of people never infected with the coronavirus to help investigators make a stronger case.

“A lot of the symptoms of long COVID are nonspecific and therefore can occur in people never infected,” says senior study author Jill P. Pell, MD, head of the School of Health and Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Ruling out coincidence

This study shows that people experienced a wide range of symptoms after becoming infected with COVID-19 at a significantly higher rate than those who were never infected, “thereby confirming that they were genuinely associated with COVID and not merely a coincidence,” she said.

Among 21,525 people who had COVID-19 and had symptoms, tiredness, headache and muscle aches or muscle weakness were the most common ongoing symptoms.

Loss of smell was almost nine times more likely in this group compared to the never-infected group in one analysis where researchers controlled for other possible factors. The risk for loss of taste was almost six times greater, followed by risk of breathlessness at three times higher.

Long COVID risk was highest after a severe original infection and among older people, women, Black, and South Asian populations, people with socioeconomic disadvantages, and those with more than one underlying health condition.

Adding up the 6% with no recovery after 18 months and 42% with partial recovery means that between 6 and 18 months following symptomatic coronavirus infection, almost half of those infected still experience persistent symptoms.

Vaccination validated

On the plus side, people vaccinated against COVID-19 before getting infected had a lower risk for some persistent symptoms. In addition, Dr. Pell and colleagues found no evidence that people who experienced asymptomatic infection were likely to experience long COVID symptoms or challenges with activities of daily living.

The findings of the Long-COVID in Scotland Study (Long-CISS) were published in the journal Nature Communications.

‘More long COVID than ever before’

“Unfortunately, these long COVID symptoms are not getting better as the cases of COVID get milder,” said Thomas Gut, DO, medical director for the post-COVID recovery program at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital. “Quite the opposite – this infection has become so common in a community because it’s so mild and spreading so rapidly that we’re seeing more long COVID symptoms than ever before.”

Although most patients he sees with long COVID resolve their symptoms within 3-6 months, “We do see some patients who require short-term disability because their symptoms continue past 6 months and out to 2 years,” said Dr. Gut, a hospitalist at Staten Island University Hospital, a member hospital of Northwell Health.

Patients with fatigue and neurocognitive symptoms “have a very tough time going back to work. Short-term disability gives them the time and finances to pursue specialty care with cardiology, pulmonary, and neurocognitive testing,” he said.

Support the whole person

The burden of living with long COVID goes beyond the persistent symptoms. “Long COVID can have wide-ranging impacts – not only on health but also quality of life and activities of daily living [including] work, mobility, self-care and more,” Dr. Pell said. “So, people with long COVID need support relevant to their individual needs and this may extend beyond the health care sector, for example including social services, school or workplace.”

Still, Lisa Penziner, RN, founder of the COVID Long Haulers Support Group in Westchester and Long Island, N.Y., said while people with the most severe cases of COVID-19 tended to have the worst long COVID symptoms, they’re not the only ones.

“We saw many post-COVID members who had mild cases and their long-haul symptoms were worse weeks later than the virus itself,” said Md. Penziner.

She estimates that 80%-90% of her support group members recover within 6 months. “However, there are others who were experiencing symptoms for much longer.”

Respiratory treatment, physical therapy, and other follow-up doctor visits are common after 6 months, for example.

“Additionally, there is a mental health component to recovery as well, meaning that the patient must learn to live while experiencing lingering, long-haul COVID symptoms in work and daily life,” said Ms. Penziner, director of special projects at North Westchester Restorative Therapy & Nursing.

In addition to ongoing medical care, people with long COVID need understanding, she said.

“While long-haul symptoms do not happen to everyone, it is proven that many do experience long-haul symptoms, and the support of the community in understanding is important.”

Limitations of the study

Dr. Pell and colleagues noted some strengths and weaknesses to their study. For example, “as a general population study, our findings provide a better indication of the overall risk and burden of long COVID than hospitalized cohorts,” they noted.

Also, the Scottish population is 96% White, so other long COVID studies with more diverse participants are warranted.

Another potential weakness is the response rate of 16% among those invited to participate in the study, which Dr. Pell and colleagues addressed: “Our cohort included a large sample (33,281) of people previously infected and the response rate of 16% overall and 20% among people who had symptomatic infection was consistent with previous studies that have used SMS text invitations as the sole method of recruitment.”

“We tell patients this should last 3-6 months, but some patients have longer recovery periods,” Dr. Gut said. “We’re here for them. We have a lot of services available to help get them through the recovery process, and we have a lot of options to help support them.”

“What we found most helpful is when there is peer-to-peer support, reaffirming to the member that they are not alone in the long-haul battle, which has been a major benefit of the support group,” Ms. Penziner said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

in the same time frame, a large study out of Scotland found.

Multiple studies are evaluating people with long COVID in the hopes of figuring out why some people experience debilitating symptoms long after their primary infection ends and others either do not or recover more quickly.

This current study is notable for its large size – 96,238 people. Researchers checked in with participants at 6, 12, and 18 months, and included a group of people never infected with the coronavirus to help investigators make a stronger case.

“A lot of the symptoms of long COVID are nonspecific and therefore can occur in people never infected,” says senior study author Jill P. Pell, MD, head of the School of Health and Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Ruling out coincidence

This study shows that people experienced a wide range of symptoms after becoming infected with COVID-19 at a significantly higher rate than those who were never infected, “thereby confirming that they were genuinely associated with COVID and not merely a coincidence,” she said.

Among 21,525 people who had COVID-19 and had symptoms, tiredness, headache and muscle aches or muscle weakness were the most common ongoing symptoms.

Loss of smell was almost nine times more likely in this group compared to the never-infected group in one analysis where researchers controlled for other possible factors. The risk for loss of taste was almost six times greater, followed by risk of breathlessness at three times higher.

Long COVID risk was highest after a severe original infection and among older people, women, Black, and South Asian populations, people with socioeconomic disadvantages, and those with more than one underlying health condition.

Adding up the 6% with no recovery after 18 months and 42% with partial recovery means that between 6 and 18 months following symptomatic coronavirus infection, almost half of those infected still experience persistent symptoms.

Vaccination validated

On the plus side, people vaccinated against COVID-19 before getting infected had a lower risk for some persistent symptoms. In addition, Dr. Pell and colleagues found no evidence that people who experienced asymptomatic infection were likely to experience long COVID symptoms or challenges with activities of daily living.

The findings of the Long-COVID in Scotland Study (Long-CISS) were published in the journal Nature Communications.

‘More long COVID than ever before’

“Unfortunately, these long COVID symptoms are not getting better as the cases of COVID get milder,” said Thomas Gut, DO, medical director for the post-COVID recovery program at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital. “Quite the opposite – this infection has become so common in a community because it’s so mild and spreading so rapidly that we’re seeing more long COVID symptoms than ever before.”

Although most patients he sees with long COVID resolve their symptoms within 3-6 months, “We do see some patients who require short-term disability because their symptoms continue past 6 months and out to 2 years,” said Dr. Gut, a hospitalist at Staten Island University Hospital, a member hospital of Northwell Health.

Patients with fatigue and neurocognitive symptoms “have a very tough time going back to work. Short-term disability gives them the time and finances to pursue specialty care with cardiology, pulmonary, and neurocognitive testing,” he said.

Support the whole person

The burden of living with long COVID goes beyond the persistent symptoms. “Long COVID can have wide-ranging impacts – not only on health but also quality of life and activities of daily living [including] work, mobility, self-care and more,” Dr. Pell said. “So, people with long COVID need support relevant to their individual needs and this may extend beyond the health care sector, for example including social services, school or workplace.”

Still, Lisa Penziner, RN, founder of the COVID Long Haulers Support Group in Westchester and Long Island, N.Y., said while people with the most severe cases of COVID-19 tended to have the worst long COVID symptoms, they’re not the only ones.

“We saw many post-COVID members who had mild cases and their long-haul symptoms were worse weeks later than the virus itself,” said Md. Penziner.

She estimates that 80%-90% of her support group members recover within 6 months. “However, there are others who were experiencing symptoms for much longer.”

Respiratory treatment, physical therapy, and other follow-up doctor visits are common after 6 months, for example.

“Additionally, there is a mental health component to recovery as well, meaning that the patient must learn to live while experiencing lingering, long-haul COVID symptoms in work and daily life,” said Ms. Penziner, director of special projects at North Westchester Restorative Therapy & Nursing.

In addition to ongoing medical care, people with long COVID need understanding, she said.

“While long-haul symptoms do not happen to everyone, it is proven that many do experience long-haul symptoms, and the support of the community in understanding is important.”

Limitations of the study

Dr. Pell and colleagues noted some strengths and weaknesses to their study. For example, “as a general population study, our findings provide a better indication of the overall risk and burden of long COVID than hospitalized cohorts,” they noted.

Also, the Scottish population is 96% White, so other long COVID studies with more diverse participants are warranted.

Another potential weakness is the response rate of 16% among those invited to participate in the study, which Dr. Pell and colleagues addressed: “Our cohort included a large sample (33,281) of people previously infected and the response rate of 16% overall and 20% among people who had symptomatic infection was consistent with previous studies that have used SMS text invitations as the sole method of recruitment.”

“We tell patients this should last 3-6 months, but some patients have longer recovery periods,” Dr. Gut said. “We’re here for them. We have a lot of services available to help get them through the recovery process, and we have a lot of options to help support them.”

“What we found most helpful is when there is peer-to-peer support, reaffirming to the member that they are not alone in the long-haul battle, which has been a major benefit of the support group,” Ms. Penziner said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

Keep menstrual cramps away the dietary prevention way

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

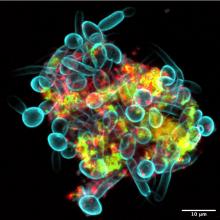

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

63% of long COVID patients are women, study says

according to a new study published in JAMA.

The global study also found that about 6% of people with symptomatic infections had long COVID in 2020 and 2021. The risk for long COVID seemed to be greater among those who needed hospitalization, especially those who needed intensive care.

“Quantifying the number of individuals with long COVID may help policy makers ensure adequate access to services to guide people toward recovery, return to the workplace or school, and restore their mental health and social life,” the researchers wrote.

The study team, which included dozens of researchers across nearly every continent, analyzed data from 54 studies and two databases for more than 1 million patients in 22 countries who had symptomatic COVID infections in 2020 and 2021. They looked at three long COVID symptom types: persistent fatigue with bodily pain or mood swings, ongoing respiratory problems, and cognitive issues. The study included people aged 4-66.

Overall, 6.2% of people reported one of the long COVID symptom types, including 3.7% with ongoing respiratory problems, 3.2% with persistent fatigue and bodily pain or mood swings, and 2.2% with cognitive problems. Among those with long COVID, 38% of people reported more than one symptom cluster.

At 3 months after infection, long COVID symptoms were nearly twice as common in women who were at least 20 years old at 10.6%, compared with men who were at least 20 years old at 5.4%.

Children and teens appeared to have lower risks of long COVID. About 2.8% of patients under age 20 with symptomatic infection developed long-term issues.

The estimated average duration of long COVID symptoms was 9 months among hospitalized patients and 4 months among those who weren’t hospitalized. About 15% of people with long COVID symptoms 3 months after the initial infection continued to have symptoms at 12 months.

The study was largely based on detailed data from ongoing COVID-19 studies in the United States, Austria, the Faroe Islands, Germany, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, and Switzerland, according to UPI. It was supplemented by published data and research conducted as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study. The dozens of researchers are referred to as “Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators.”

The study had limitations, the researchers said, including the assumption that long COVID follows a similar course in all countries. Additional studies may show how long COVID symptoms and severity may vary in different countries and continents.

Ultimately, ongoing studies of large numbers of people with long COVID could help scientists and public health officials understand risk factors and ways to treat the debilitating condition, the study authors wrote, noting that “postinfection fatigue syndrome” has been reported before, namely during the 1918 flu pandemic, after the SARS outbreak in 2003, and after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014.

“Similar symptoms have been reported after other viral infections, including the Epstein-Barr virus, mononucleosis, and dengue, as well as after nonviral infections such as Q fever, Lyme disease and giardiasis,” they wrote.

Several study investigators reported receiving grants and personal fees from a variety of sources.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study published in JAMA.

The global study also found that about 6% of people with symptomatic infections had long COVID in 2020 and 2021. The risk for long COVID seemed to be greater among those who needed hospitalization, especially those who needed intensive care.

“Quantifying the number of individuals with long COVID may help policy makers ensure adequate access to services to guide people toward recovery, return to the workplace or school, and restore their mental health and social life,” the researchers wrote.

The study team, which included dozens of researchers across nearly every continent, analyzed data from 54 studies and two databases for more than 1 million patients in 22 countries who had symptomatic COVID infections in 2020 and 2021. They looked at three long COVID symptom types: persistent fatigue with bodily pain or mood swings, ongoing respiratory problems, and cognitive issues. The study included people aged 4-66.

Overall, 6.2% of people reported one of the long COVID symptom types, including 3.7% with ongoing respiratory problems, 3.2% with persistent fatigue and bodily pain or mood swings, and 2.2% with cognitive problems. Among those with long COVID, 38% of people reported more than one symptom cluster.

At 3 months after infection, long COVID symptoms were nearly twice as common in women who were at least 20 years old at 10.6%, compared with men who were at least 20 years old at 5.4%.

Children and teens appeared to have lower risks of long COVID. About 2.8% of patients under age 20 with symptomatic infection developed long-term issues.

The estimated average duration of long COVID symptoms was 9 months among hospitalized patients and 4 months among those who weren’t hospitalized. About 15% of people with long COVID symptoms 3 months after the initial infection continued to have symptoms at 12 months.

The study was largely based on detailed data from ongoing COVID-19 studies in the United States, Austria, the Faroe Islands, Germany, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, and Switzerland, according to UPI. It was supplemented by published data and research conducted as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study. The dozens of researchers are referred to as “Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators.”

The study had limitations, the researchers said, including the assumption that long COVID follows a similar course in all countries. Additional studies may show how long COVID symptoms and severity may vary in different countries and continents.

Ultimately, ongoing studies of large numbers of people with long COVID could help scientists and public health officials understand risk factors and ways to treat the debilitating condition, the study authors wrote, noting that “postinfection fatigue syndrome” has been reported before, namely during the 1918 flu pandemic, after the SARS outbreak in 2003, and after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014.

“Similar symptoms have been reported after other viral infections, including the Epstein-Barr virus, mononucleosis, and dengue, as well as after nonviral infections such as Q fever, Lyme disease and giardiasis,” they wrote.

Several study investigators reported receiving grants and personal fees from a variety of sources.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study published in JAMA.

The global study also found that about 6% of people with symptomatic infections had long COVID in 2020 and 2021. The risk for long COVID seemed to be greater among those who needed hospitalization, especially those who needed intensive care.

“Quantifying the number of individuals with long COVID may help policy makers ensure adequate access to services to guide people toward recovery, return to the workplace or school, and restore their mental health and social life,” the researchers wrote.

The study team, which included dozens of researchers across nearly every continent, analyzed data from 54 studies and two databases for more than 1 million patients in 22 countries who had symptomatic COVID infections in 2020 and 2021. They looked at three long COVID symptom types: persistent fatigue with bodily pain or mood swings, ongoing respiratory problems, and cognitive issues. The study included people aged 4-66.

Overall, 6.2% of people reported one of the long COVID symptom types, including 3.7% with ongoing respiratory problems, 3.2% with persistent fatigue and bodily pain or mood swings, and 2.2% with cognitive problems. Among those with long COVID, 38% of people reported more than one symptom cluster.

At 3 months after infection, long COVID symptoms were nearly twice as common in women who were at least 20 years old at 10.6%, compared with men who were at least 20 years old at 5.4%.

Children and teens appeared to have lower risks of long COVID. About 2.8% of patients under age 20 with symptomatic infection developed long-term issues.

The estimated average duration of long COVID symptoms was 9 months among hospitalized patients and 4 months among those who weren’t hospitalized. About 15% of people with long COVID symptoms 3 months after the initial infection continued to have symptoms at 12 months.

The study was largely based on detailed data from ongoing COVID-19 studies in the United States, Austria, the Faroe Islands, Germany, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, and Switzerland, according to UPI. It was supplemented by published data and research conducted as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study. The dozens of researchers are referred to as “Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators.”

The study had limitations, the researchers said, including the assumption that long COVID follows a similar course in all countries. Additional studies may show how long COVID symptoms and severity may vary in different countries and continents.

Ultimately, ongoing studies of large numbers of people with long COVID could help scientists and public health officials understand risk factors and ways to treat the debilitating condition, the study authors wrote, noting that “postinfection fatigue syndrome” has been reported before, namely during the 1918 flu pandemic, after the SARS outbreak in 2003, and after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014.

“Similar symptoms have been reported after other viral infections, including the Epstein-Barr virus, mononucleosis, and dengue, as well as after nonviral infections such as Q fever, Lyme disease and giardiasis,” they wrote.

Several study investigators reported receiving grants and personal fees from a variety of sources.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Why people lie about COVID

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Have you ever lied about COVID-19?

Before you get upset, before the “how dare you,” I want you to think carefully.

Did you have COVID-19 (or think you did) and not mention it to someone you were going to be with? Did you tell someone you were taking more COVID precautions than you really were? Did you tell someone you were vaccinated when you weren’t? Have you avoided getting a COVID test even though you knew you should have?

Researchers appreciated the fact that public health interventions in COVID are important but are only as good as the percentage of people who actually abide by them. So, they designed a survey to ask the questions that many people don’t want to hear the answer to.

A total of 1,733 participants – 80% of those invited – responded to the survey. By design, approximately one-third of respondents (477) had already had COVID, one-third (499) were vaccinated and not yet infected, and one-third (509) were unvaccinated and not yet infected.

Of those surveyed, 41.6% admitted that they lied about COVID or didn’t adhere to COVID guidelines - a conservative estimate, if you ask me.

Breaking down some of the results, about 20% of people who previously were infected with COVID said they didn’t mention it when meeting with someone. A similar number said they didn’t tell anyone when they were entering a public place. A bit more concerning to me, roughly 20% reported not disclosing their COVID-positive status when going to a health care provider’s office.

About 10% of those who had not been vaccinated reported lying about their vaccination status. That’s actually less than the 15% of vaccinated people who lied and told someone they weren’t vaccinated.

About 17% of people lied about the need to quarantine, and many more broke quarantine rules.

The authors tried to see if certain personal characteristics predicted people who were more likely to lie about COVID-19–related issues. Turns out there was only one thing that predicted honesty: age.

Older people were more honest about their COVID status and COVID habits. Other factors – gender, education, race, political affiliation, COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, and where you got your COVID information – did not seem to make much of a difference. Why are older people more honest? Because older people take COVID more seriously. And they should; COVID is more severe in older people.

The problem arises, of course, because people who are at lower risk for COVID complications interact with people at higher risk – and in those situations, honesty matters more.

On the other hand, isn’t lying about COVID stuff inevitable? If you know that a positive test means you can’t go to work, and not going to work means you won’t get paid, might you not be more likely to lie about the test? Or not get the test at all?

The authors explored the reasons for dishonesty and they are fairly broad, ranging from the desire for life to feel normal (more than half of people who lied) to not believing that COVID was real (a whopping 30%). Some of the reasons for lying included:

- Wanted life to feel normal (50%).

- Freedom (45%).

- It’s no one’s business (40%).

- COVID isn’t real (30%).

In the end, though, we need to realize that public health recommendations are not going to be universally followed, and people may tell us they are following them when, in fact, they are not.

What this adds is another data point to a trend we’ve seen across the course of the pandemic, a shift from collective to individual responsibility. If you can’t be sure what others are doing in regard to COVID, you need to focus on protecting yourself. Perhaps that shift was inevitable. Doesn’t mean we have to like it.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Have you ever lied about COVID-19?

Before you get upset, before the “how dare you,” I want you to think carefully.

Did you have COVID-19 (or think you did) and not mention it to someone you were going to be with? Did you tell someone you were taking more COVID precautions than you really were? Did you tell someone you were vaccinated when you weren’t? Have you avoided getting a COVID test even though you knew you should have?

Researchers appreciated the fact that public health interventions in COVID are important but are only as good as the percentage of people who actually abide by them. So, they designed a survey to ask the questions that many people don’t want to hear the answer to.

A total of 1,733 participants – 80% of those invited – responded to the survey. By design, approximately one-third of respondents (477) had already had COVID, one-third (499) were vaccinated and not yet infected, and one-third (509) were unvaccinated and not yet infected.

Of those surveyed, 41.6% admitted that they lied about COVID or didn’t adhere to COVID guidelines - a conservative estimate, if you ask me.

Breaking down some of the results, about 20% of people who previously were infected with COVID said they didn’t mention it when meeting with someone. A similar number said they didn’t tell anyone when they were entering a public place. A bit more concerning to me, roughly 20% reported not disclosing their COVID-positive status when going to a health care provider’s office.

About 10% of those who had not been vaccinated reported lying about their vaccination status. That’s actually less than the 15% of vaccinated people who lied and told someone they weren’t vaccinated.

About 17% of people lied about the need to quarantine, and many more broke quarantine rules.

The authors tried to see if certain personal characteristics predicted people who were more likely to lie about COVID-19–related issues. Turns out there was only one thing that predicted honesty: age.

Older people were more honest about their COVID status and COVID habits. Other factors – gender, education, race, political affiliation, COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, and where you got your COVID information – did not seem to make much of a difference. Why are older people more honest? Because older people take COVID more seriously. And they should; COVID is more severe in older people.

The problem arises, of course, because people who are at lower risk for COVID complications interact with people at higher risk – and in those situations, honesty matters more.

On the other hand, isn’t lying about COVID stuff inevitable? If you know that a positive test means you can’t go to work, and not going to work means you won’t get paid, might you not be more likely to lie about the test? Or not get the test at all?

The authors explored the reasons for dishonesty and they are fairly broad, ranging from the desire for life to feel normal (more than half of people who lied) to not believing that COVID was real (a whopping 30%). Some of the reasons for lying included:

- Wanted life to feel normal (50%).

- Freedom (45%).

- It’s no one’s business (40%).

- COVID isn’t real (30%).

In the end, though, we need to realize that public health recommendations are not going to be universally followed, and people may tell us they are following them when, in fact, they are not.

What this adds is another data point to a trend we’ve seen across the course of the pandemic, a shift from collective to individual responsibility. If you can’t be sure what others are doing in regard to COVID, you need to focus on protecting yourself. Perhaps that shift was inevitable. Doesn’t mean we have to like it.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Have you ever lied about COVID-19?

Before you get upset, before the “how dare you,” I want you to think carefully.

Did you have COVID-19 (or think you did) and not mention it to someone you were going to be with? Did you tell someone you were taking more COVID precautions than you really were? Did you tell someone you were vaccinated when you weren’t? Have you avoided getting a COVID test even though you knew you should have?

Researchers appreciated the fact that public health interventions in COVID are important but are only as good as the percentage of people who actually abide by them. So, they designed a survey to ask the questions that many people don’t want to hear the answer to.

A total of 1,733 participants – 80% of those invited – responded to the survey. By design, approximately one-third of respondents (477) had already had COVID, one-third (499) were vaccinated and not yet infected, and one-third (509) were unvaccinated and not yet infected.

Of those surveyed, 41.6% admitted that they lied about COVID or didn’t adhere to COVID guidelines - a conservative estimate, if you ask me.

Breaking down some of the results, about 20% of people who previously were infected with COVID said they didn’t mention it when meeting with someone. A similar number said they didn’t tell anyone when they were entering a public place. A bit more concerning to me, roughly 20% reported not disclosing their COVID-positive status when going to a health care provider’s office.

About 10% of those who had not been vaccinated reported lying about their vaccination status. That’s actually less than the 15% of vaccinated people who lied and told someone they weren’t vaccinated.

About 17% of people lied about the need to quarantine, and many more broke quarantine rules.

The authors tried to see if certain personal characteristics predicted people who were more likely to lie about COVID-19–related issues. Turns out there was only one thing that predicted honesty: age.

Older people were more honest about their COVID status and COVID habits. Other factors – gender, education, race, political affiliation, COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, and where you got your COVID information – did not seem to make much of a difference. Why are older people more honest? Because older people take COVID more seriously. And they should; COVID is more severe in older people.

The problem arises, of course, because people who are at lower risk for COVID complications interact with people at higher risk – and in those situations, honesty matters more.

On the other hand, isn’t lying about COVID stuff inevitable? If you know that a positive test means you can’t go to work, and not going to work means you won’t get paid, might you not be more likely to lie about the test? Or not get the test at all?

The authors explored the reasons for dishonesty and they are fairly broad, ranging from the desire for life to feel normal (more than half of people who lied) to not believing that COVID was real (a whopping 30%). Some of the reasons for lying included:

- Wanted life to feel normal (50%).

- Freedom (45%).

- It’s no one’s business (40%).

- COVID isn’t real (30%).

In the end, though, we need to realize that public health recommendations are not going to be universally followed, and people may tell us they are following them when, in fact, they are not.

What this adds is another data point to a trend we’ve seen across the course of the pandemic, a shift from collective to individual responsibility. If you can’t be sure what others are doing in regard to COVID, you need to focus on protecting yourself. Perhaps that shift was inevitable. Doesn’t mean we have to like it.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com.

ACC issues guidance on ED evaluation of acute chest pain

Chest pain accounts for more than 7 million ED visits annually. A major challenge is to quickly identify the small number of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) among the large number of patients who have noncardiac conditions.

The new document is intended to provide guidance on how to “practically apply” recommendations from the 2021 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain, focusing specifically on patients who present to the ED, the writing group explains.

“A systematic approach – both at the level of the institution and the individual patient – is essential to achieve optimal outcomes for patients presenting with chest pain to the ED,” say writing group chair Michael Kontos, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and colleagues.

At the institution level, this decision pathway recommends high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays coupled with a clinical decision pathway (CDP) to reduce ED “dwell” times and increase the number of patients with chest pain who can safely be discharged without additional testing. This will decrease ED crowding and limit unnecessary testing, they point out.

At the individual patient level, this document aims to provide structure for the ED evaluation of chest pain, accelerating the evaluation process and matching the intensity of testing and treatment to patient risk.

The 36-page document was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Key summary points in the document include the following:

- Electrocardiogram remains the best initial test for evaluation of chest pain in the ED and should be performed and interpreted within 10 minutes of ED arrival.

- In patients who arrive via ambulance, the prehospital ECG should be reviewed, because ischemic changes may have resolved before ED arrival.

- When the ECG shows evidence of acute infarction or ischemia, subsequent care should follow current guidelines for management of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non–ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS).

- Patients with a nonischemic ECG can enter an accelerated CDP designed to provide rapid risk assessment and exclusion of ACS.

- Patients who are hemodynamically unstable, have significant arrhythmias, or evidence of significant heart failure should be evaluated and treated appropriately and are not candidates for an accelerated CDP.

- High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) are the preferred biomarkers for evaluation of possible ACS.

- Patients classified as low risk (rule out) using the current hs-cTn-based CDPs can generally be discharged directly from the ED without additional testing, although outpatient testing may be considered in selected cases.

- Patients with substantially elevated initial hs-cTn values or those with significant dynamic changes over 1-3 hours are assigned to the abnormal/high-risk category and should be further classified according to the universal definition of myocardial infarction type 1 or 2 or acute or chronic nonischemic cardiac injury.

- High-risk patients should usually be admitted to an inpatient setting for further evaluation and treatment.

- Patients determined to be intermediate risk with the CDP should undergo additional observation with repeat hs-cTn measurements at 3-6 hours and risk assessment using either the modified HEART (history, ECG, age, risk factors, and troponin) score or the ED assessment of chest pain score (EDACS).

- Noninvasive testing should be considered for the intermediate-risk group unless low-risk features are identified using risk scores or noninvasive testing has been performed recently with normal or low-risk findings.

The writing group notes that “safe and efficient” management of chest pain in the ED requires appropriate follow-up after discharge. Timing of follow-up and referral for outpatient noninvasive testing should be influenced by patient risk and results of cardiac testing.

Disclosures for members of the writing group are available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chest pain accounts for more than 7 million ED visits annually. A major challenge is to quickly identify the small number of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) among the large number of patients who have noncardiac conditions.

The new document is intended to provide guidance on how to “practically apply” recommendations from the 2021 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain, focusing specifically on patients who present to the ED, the writing group explains.

“A systematic approach – both at the level of the institution and the individual patient – is essential to achieve optimal outcomes for patients presenting with chest pain to the ED,” say writing group chair Michael Kontos, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and colleagues.

At the institution level, this decision pathway recommends high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays coupled with a clinical decision pathway (CDP) to reduce ED “dwell” times and increase the number of patients with chest pain who can safely be discharged without additional testing. This will decrease ED crowding and limit unnecessary testing, they point out.

At the individual patient level, this document aims to provide structure for the ED evaluation of chest pain, accelerating the evaluation process and matching the intensity of testing and treatment to patient risk.

The 36-page document was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Key summary points in the document include the following:

- Electrocardiogram remains the best initial test for evaluation of chest pain in the ED and should be performed and interpreted within 10 minutes of ED arrival.

- In patients who arrive via ambulance, the prehospital ECG should be reviewed, because ischemic changes may have resolved before ED arrival.

- When the ECG shows evidence of acute infarction or ischemia, subsequent care should follow current guidelines for management of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non–ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS).

- Patients with a nonischemic ECG can enter an accelerated CDP designed to provide rapid risk assessment and exclusion of ACS.

- Patients who are hemodynamically unstable, have significant arrhythmias, or evidence of significant heart failure should be evaluated and treated appropriately and are not candidates for an accelerated CDP.

- High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) are the preferred biomarkers for evaluation of possible ACS.

- Patients classified as low risk (rule out) using the current hs-cTn-based CDPs can generally be discharged directly from the ED without additional testing, although outpatient testing may be considered in selected cases.

- Patients with substantially elevated initial hs-cTn values or those with significant dynamic changes over 1-3 hours are assigned to the abnormal/high-risk category and should be further classified according to the universal definition of myocardial infarction type 1 or 2 or acute or chronic nonischemic cardiac injury.

- High-risk patients should usually be admitted to an inpatient setting for further evaluation and treatment.

- Patients determined to be intermediate risk with the CDP should undergo additional observation with repeat hs-cTn measurements at 3-6 hours and risk assessment using either the modified HEART (history, ECG, age, risk factors, and troponin) score or the ED assessment of chest pain score (EDACS).

- Noninvasive testing should be considered for the intermediate-risk group unless low-risk features are identified using risk scores or noninvasive testing has been performed recently with normal or low-risk findings.

The writing group notes that “safe and efficient” management of chest pain in the ED requires appropriate follow-up after discharge. Timing of follow-up and referral for outpatient noninvasive testing should be influenced by patient risk and results of cardiac testing.

Disclosures for members of the writing group are available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chest pain accounts for more than 7 million ED visits annually. A major challenge is to quickly identify the small number of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) among the large number of patients who have noncardiac conditions.

The new document is intended to provide guidance on how to “practically apply” recommendations from the 2021 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain, focusing specifically on patients who present to the ED, the writing group explains.

“A systematic approach – both at the level of the institution and the individual patient – is essential to achieve optimal outcomes for patients presenting with chest pain to the ED,” say writing group chair Michael Kontos, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and colleagues.

At the institution level, this decision pathway recommends high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays coupled with a clinical decision pathway (CDP) to reduce ED “dwell” times and increase the number of patients with chest pain who can safely be discharged without additional testing. This will decrease ED crowding and limit unnecessary testing, they point out.

At the individual patient level, this document aims to provide structure for the ED evaluation of chest pain, accelerating the evaluation process and matching the intensity of testing and treatment to patient risk.

The 36-page document was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Key summary points in the document include the following:

- Electrocardiogram remains the best initial test for evaluation of chest pain in the ED and should be performed and interpreted within 10 minutes of ED arrival.

- In patients who arrive via ambulance, the prehospital ECG should be reviewed, because ischemic changes may have resolved before ED arrival.

- When the ECG shows evidence of acute infarction or ischemia, subsequent care should follow current guidelines for management of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non–ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS).

- Patients with a nonischemic ECG can enter an accelerated CDP designed to provide rapid risk assessment and exclusion of ACS.

- Patients who are hemodynamically unstable, have significant arrhythmias, or evidence of significant heart failure should be evaluated and treated appropriately and are not candidates for an accelerated CDP.

- High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) are the preferred biomarkers for evaluation of possible ACS.

- Patients classified as low risk (rule out) using the current hs-cTn-based CDPs can generally be discharged directly from the ED without additional testing, although outpatient testing may be considered in selected cases.

- Patients with substantially elevated initial hs-cTn values or those with significant dynamic changes over 1-3 hours are assigned to the abnormal/high-risk category and should be further classified according to the universal definition of myocardial infarction type 1 or 2 or acute or chronic nonischemic cardiac injury.

- High-risk patients should usually be admitted to an inpatient setting for further evaluation and treatment.

- Patients determined to be intermediate risk with the CDP should undergo additional observation with repeat hs-cTn measurements at 3-6 hours and risk assessment using either the modified HEART (history, ECG, age, risk factors, and troponin) score or the ED assessment of chest pain score (EDACS).

- Noninvasive testing should be considered for the intermediate-risk group unless low-risk features are identified using risk scores or noninvasive testing has been performed recently with normal or low-risk findings.

The writing group notes that “safe and efficient” management of chest pain in the ED requires appropriate follow-up after discharge. Timing of follow-up and referral for outpatient noninvasive testing should be influenced by patient risk and results of cardiac testing.

Disclosures for members of the writing group are available with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

New advice on artificial pancreas insulin delivery systems

A new consensus statement summarizes the benefits, limitations, and challenges of using automated insulin delivery (AID) systems and provides recommendations for use by people with diabetes.

“Automated insulin delivery systems” is becoming the standard terminology – including by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration – to refer to systems that integrate data from a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system via a control algorithm into an insulin pump in order to automate subcutaneous insulin delivery. “Hybrid AID” or “hybrid closed-loop” refers to the current status of these systems, which still require some degree of user input to control glucose levels.

The term “artificial pancreas” was used interchangeably with AID in the past, but it doesn’t take into account exocrine pancreatic function. The term “bionic pancreas” refers to a specific system in development that would ultimately include glucagon along with insulin.

The new consensus report, titled “Automated insulin delivery: Benefits, challenges, and recommendations,” was published online in Diabetes Care and Diabetologia.

The document is geared toward not only diabetologists and other specialists, but also diabetes nurses and specialist dietitians. Colleagues working at regulatory agencies, health care organizations, and related media might also benefit from reading it.

It is endorsed by two professional societies – the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association – and contrasts with other statements about AID systems that are sponsored by their manufacturers, noted document co-author Mark Evans, PhD, professor of diabetic medicine, University of Cambridge, England, in a statement.

“Many clinically relevant aspects, including safety, are addressed in this report. The aim ... is to encourage ongoing improvement of this technology, its safe and effective use, and its accessibility to all who can benefit from it,” Dr. Evans said.

Lead author Jennifer Sherr, MD, PhD, pediatric endocrinology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., commented that the report “addresses the clinical usage of AID systems from a practical point of view rather than as ... a meta-analysis or a review of all relevant clinical studies. ... As such, the benefits and limitations of systems are discussed while also considering safety, regulatory pathways, and access to this technology.”

AID systems do not mean diabetes is “cured”

Separate recommendations provided at the end of the document are aimed at specific stakeholders, including health care providers, patients and their caregivers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and the research community.

The authors make clear in the introduction that, while representing “a significant movement toward optimizing glucose management for individuals with diabetes,” the use of AID systems doesn’t mean that diabetes is “cured.” Rather, “expectations need to be set adequately so that individuals with diabetes and providers understand what such systems can and cannot do.”

In particular, current commercially available AID systems require user input for mealtime insulin dosing and sometimes for correction doses of high blood glucose levels, although the systems at least partially automate that.

“When integrated into care, AID systems hold promise to relieve some of the daily burdens of diabetes care,” the authors write.

The statement also details problems that may arise with the physical devices, including skin irritation from adhesives, occlusion of insulin infusion sets, early CGM sensor failure, and inadequate dosing algorithms.

“Individuals with diabetes who are considering this type of advanced diabetes therapy should not only have appropriate technical understanding of the system but also be able to revert to standard diabetes treatment (that is, nonautomated subcutaneous insulin delivery by pump or injections) in case the AID system fails. They should be able to independently troubleshoot and have access to their health care provider if needed.”

To monitor the impact of the technology, the authors emphasize the importance of the time-in-range metric derived from CGM, with the goal of achieving 70% or greater time in target blood glucose range.

Separate sections of the document address the benefits and limitations of AID systems, education and expectations for both patients and providers, and patient and provider perspectives, including how to handle urgent questions.

Other sections cover special populations such as pregnant women and people with type 2 diabetes, considerations for patient selection for current AID systems, safety, improving access to the technology, liability, and do-it-yourself systems.

Recommendations for health care professionals

A table near the end of the document provides specific recommendations for health care professionals, including the following:

- Be knowledgeable about AID systems and nuances of different systems, including their distinguishing features as well as strengths and weaknesses.

- Inform patients with diabetes about AID systems, including review of currently available systems, and create realistic expectations for device use.

- Involve patients with diabetes in shared decision-making when considering use of AID systems.

- Share information with patients with diabetes, as well as their peers, about general standards set by national and international guidelines on AID systems.