User login

Parenting style linked to toddler sensory adaptation, behavior

SAN FRANCISCO – Children of parents who have a permissive parenting style were more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation at age 1 year and increased behavior difficulties at 2 years, compared to children exposed to other parenting styles, in a new, unpublished study.

Toddlers with permissive parents had more than double the risk of internalizing behaviors and triple the risk of externalizing behaviors compared to peers whose parents used an authoritative or authoritarian parenting style, reported Mary Lauren Neel, MD, a fellow in pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. This association appeared stronger among preterm infants, but without a statistically significant increased effect.

Dr. Neel’s study tested whether children’s sensory adaptation differed according to parenting styles, as defined by the validated Baumrind’s framework of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting (Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967 Feb;75[1]:43-88). These styles are based on parents’ demandingness (whether they have developmentally appropriate expectations of their child) and responsivity (how sensitively parents perceive and respond to children’s needs), Dr. Neel explained. The majority of the children’s parents (61%) had an authoritative style, while 18% had an authoritarian style, and 11% had a permissive style.

Previous research has identified a link between abnormal sensory interactions with the environment and early behavioral problems, and preterm infants are already more likely to experience both behavioral difficulties and atypical sensory adaption than are children born at term. Dr. Neel’s research, therefore, compared 52 term infants and 51 preterm infants. The median gestational age at birth was 35 weeks, and 29% of the cohort were very preterm, born at 32 weeks or earlier. Almost all (97%) of the mothers had at least a high school education.

The researchers assessed the infants at 12 months with the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile and at 24 months with the Child Behavior Checklist. At 12 months, after adjustment for gestational age at birth, infants of authoritative parents had greater oral sensation seeking (P = .01) and decreased sensory sensitivity (P = .02), those of authoritarian parents had increased sensation seeking (P = .04), and those of permissive parents had decreased attention to children’s visual surroundings (P = .03).

One in five (21%) of the children had an atypical neurologic threshold at 1 year, but no statistically significant association was seen between an atypical threshold and authoritarian and authoritative parenting. Neither parenting style was associated with externalizing or internalizing behaviors.

Permissive parents’ children, however, were 2.6 times more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation. Further, at 2 years, these children were 2.2 times more likely to have internalizing behaviors and 3 times more likely to have externalizing behaviors, Dr. Neel reported.

“The association between permissive parenting and abnormal sensory neurological threshold in the home environment may explain the increased risk for behavior problems in children of permissive parents at 2 years,” she said. The results were consistent among term and preterm infants with a trend toward increasing significance preterm infants.

“It’s possible that prematurity augments these dynamics, but we would need a larger sample size,” she said, adding that the potential underlying mechanisms for that association are something that future research would need to tease out.

After an audience member asked about the possibility that children’s sensory capabilities might be driving parenting style, Dr. Neel acknowledged the bidirectional relationship between parent and child but noted that most psychology research suggest parenting style has more to do with the parents than with their children.

Limitations of the study include its small size and lack of data on other potential confounding factors, such as parental mental health.

The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Children of parents who have a permissive parenting style were more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation at age 1 year and increased behavior difficulties at 2 years, compared to children exposed to other parenting styles, in a new, unpublished study.

Toddlers with permissive parents had more than double the risk of internalizing behaviors and triple the risk of externalizing behaviors compared to peers whose parents used an authoritative or authoritarian parenting style, reported Mary Lauren Neel, MD, a fellow in pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. This association appeared stronger among preterm infants, but without a statistically significant increased effect.

Dr. Neel’s study tested whether children’s sensory adaptation differed according to parenting styles, as defined by the validated Baumrind’s framework of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting (Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967 Feb;75[1]:43-88). These styles are based on parents’ demandingness (whether they have developmentally appropriate expectations of their child) and responsivity (how sensitively parents perceive and respond to children’s needs), Dr. Neel explained. The majority of the children’s parents (61%) had an authoritative style, while 18% had an authoritarian style, and 11% had a permissive style.

Previous research has identified a link between abnormal sensory interactions with the environment and early behavioral problems, and preterm infants are already more likely to experience both behavioral difficulties and atypical sensory adaption than are children born at term. Dr. Neel’s research, therefore, compared 52 term infants and 51 preterm infants. The median gestational age at birth was 35 weeks, and 29% of the cohort were very preterm, born at 32 weeks or earlier. Almost all (97%) of the mothers had at least a high school education.

The researchers assessed the infants at 12 months with the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile and at 24 months with the Child Behavior Checklist. At 12 months, after adjustment for gestational age at birth, infants of authoritative parents had greater oral sensation seeking (P = .01) and decreased sensory sensitivity (P = .02), those of authoritarian parents had increased sensation seeking (P = .04), and those of permissive parents had decreased attention to children’s visual surroundings (P = .03).

One in five (21%) of the children had an atypical neurologic threshold at 1 year, but no statistically significant association was seen between an atypical threshold and authoritarian and authoritative parenting. Neither parenting style was associated with externalizing or internalizing behaviors.

Permissive parents’ children, however, were 2.6 times more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation. Further, at 2 years, these children were 2.2 times more likely to have internalizing behaviors and 3 times more likely to have externalizing behaviors, Dr. Neel reported.

“The association between permissive parenting and abnormal sensory neurological threshold in the home environment may explain the increased risk for behavior problems in children of permissive parents at 2 years,” she said. The results were consistent among term and preterm infants with a trend toward increasing significance preterm infants.

“It’s possible that prematurity augments these dynamics, but we would need a larger sample size,” she said, adding that the potential underlying mechanisms for that association are something that future research would need to tease out.

After an audience member asked about the possibility that children’s sensory capabilities might be driving parenting style, Dr. Neel acknowledged the bidirectional relationship between parent and child but noted that most psychology research suggest parenting style has more to do with the parents than with their children.

Limitations of the study include its small size and lack of data on other potential confounding factors, such as parental mental health.

The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Children of parents who have a permissive parenting style were more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation at age 1 year and increased behavior difficulties at 2 years, compared to children exposed to other parenting styles, in a new, unpublished study.

Toddlers with permissive parents had more than double the risk of internalizing behaviors and triple the risk of externalizing behaviors compared to peers whose parents used an authoritative or authoritarian parenting style, reported Mary Lauren Neel, MD, a fellow in pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. This association appeared stronger among preterm infants, but without a statistically significant increased effect.

Dr. Neel’s study tested whether children’s sensory adaptation differed according to parenting styles, as defined by the validated Baumrind’s framework of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting (Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967 Feb;75[1]:43-88). These styles are based on parents’ demandingness (whether they have developmentally appropriate expectations of their child) and responsivity (how sensitively parents perceive and respond to children’s needs), Dr. Neel explained. The majority of the children’s parents (61%) had an authoritative style, while 18% had an authoritarian style, and 11% had a permissive style.

Previous research has identified a link between abnormal sensory interactions with the environment and early behavioral problems, and preterm infants are already more likely to experience both behavioral difficulties and atypical sensory adaption than are children born at term. Dr. Neel’s research, therefore, compared 52 term infants and 51 preterm infants. The median gestational age at birth was 35 weeks, and 29% of the cohort were very preterm, born at 32 weeks or earlier. Almost all (97%) of the mothers had at least a high school education.

The researchers assessed the infants at 12 months with the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile and at 24 months with the Child Behavior Checklist. At 12 months, after adjustment for gestational age at birth, infants of authoritative parents had greater oral sensation seeking (P = .01) and decreased sensory sensitivity (P = .02), those of authoritarian parents had increased sensation seeking (P = .04), and those of permissive parents had decreased attention to children’s visual surroundings (P = .03).

One in five (21%) of the children had an atypical neurologic threshold at 1 year, but no statistically significant association was seen between an atypical threshold and authoritarian and authoritative parenting. Neither parenting style was associated with externalizing or internalizing behaviors.

Permissive parents’ children, however, were 2.6 times more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation. Further, at 2 years, these children were 2.2 times more likely to have internalizing behaviors and 3 times more likely to have externalizing behaviors, Dr. Neel reported.

“The association between permissive parenting and abnormal sensory neurological threshold in the home environment may explain the increased risk for behavior problems in children of permissive parents at 2 years,” she said. The results were consistent among term and preterm infants with a trend toward increasing significance preterm infants.

“It’s possible that prematurity augments these dynamics, but we would need a larger sample size,” she said, adding that the potential underlying mechanisms for that association are something that future research would need to tease out.

After an audience member asked about the possibility that children’s sensory capabilities might be driving parenting style, Dr. Neel acknowledged the bidirectional relationship between parent and child but noted that most psychology research suggest parenting style has more to do with the parents than with their children.

Limitations of the study include its small size and lack of data on other potential confounding factors, such as parental mental health.

The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

AT PAS 17

Key clinical point: A permissive parenting style is associated with greater behavioral problems in children at age 2 years.

Major finding: Children of permissive parents had 2.2 times greater likelihood of internalizing behaviors and 3 times greater risk of externalizing behaviors at age 2, compared to children of parents with other styles.

Data source: A prospective observational study of 103 infants assessed at 12 and 24 months.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

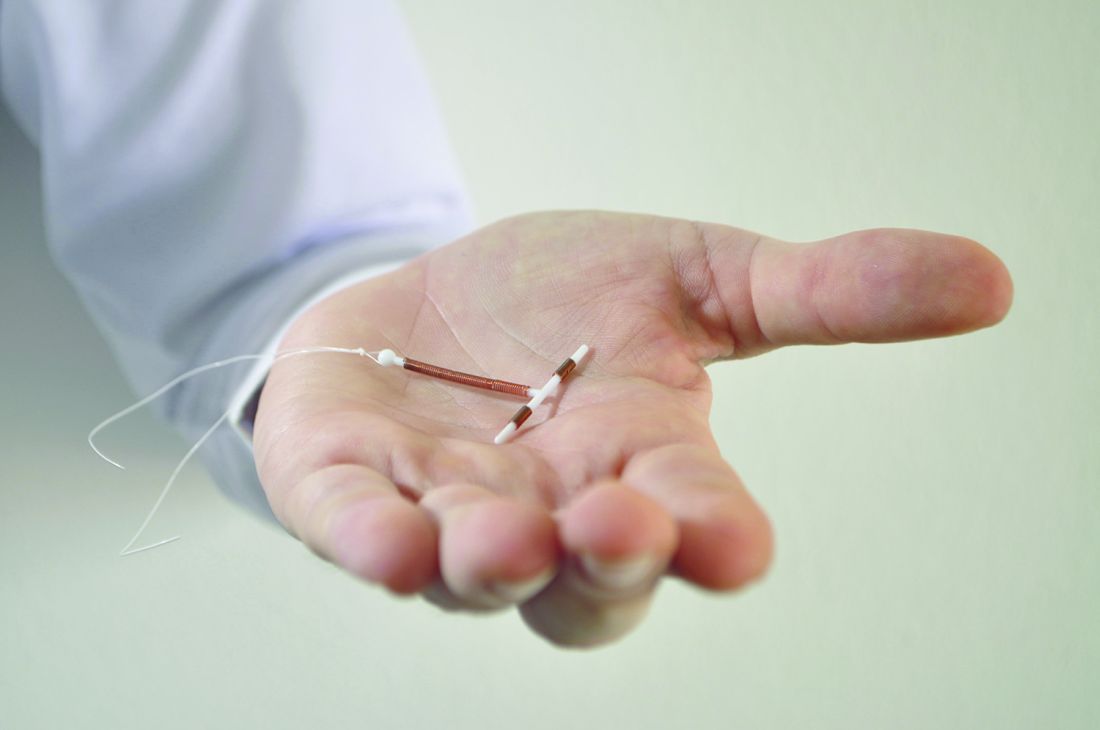

Hormonal IUDs have higher expulsion rates immediately postpartum

Hormonal intrauterine devices inserted immediately postpartum had a nearly six times greater likelihood of expulsion compared with copper IUDs, but most women who requested any type of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) postpartum were still using it half a year later, a recent study found.

“With more than eight out of ten women continuing use at 6 months, in-hospital placement of postpartum LARC devices is a worthwhile intervention,” reported Jennifer L. Eggebroten, MD, and her associates at the University of Utah. “More than half of women who experienced IUD expulsion without commencement of another highly effective contraceptive went on to become pregnant within 2 years, highlighting the need for appropriate counseling prior to device placement and backup contraception planning.”

Ninety percent of the patients were Hispanic, 87% had prior children, and 87% had an income below $24,000. Most (77%) had a vaginal delivery. Those who requested the copper IUD tended to be older and have more children compared with those who asked for the hormonal IUD or implant.

Among the 289 patients who completed the 6 months of follow-up, 17% of those with a hormonal IUD had an expulsion, compared with 4% of women with copper IUDs. That translated to a 5.8 times greater risk of expulsion for hormonal IUDs than for copper ones after the researchers accounted for age, mode of delivery, parity, and any breastfeeding. Expulsion rates were statistically similar between those who had vaginal deliveries and those who had cesarean deliveries.

Just 8% of the women requested removal of their device during the 6 months of follow-up. Most (67%) of the 21 women who had expulsions asked for a replacement. Cost of the device delayed or prevented replacement in some cases. Over the next 2 years, 6 of the 11 women who did not get replacement devices became pregnant.

Meanwhile, 81% of women with a hormonal IUD (88% including replacements), 83% with a copper IUD (86% including replacements), and 90% with an implant were still using that device 6 months later. A quarter of the women who completed the study follow-up reported that they did not return to their providers for their postpartum exams.

“For patients at high risk of rapid repeat pregnancy or who may not return for a postpartum visit, the benefit of placement of a highly effective method of contraception in the hospital prior to discharge may outweigh the increased risk of expulsion,” the researchers wrote. “In some states, by 8 weeks, public insurance coverage may expire and women face much more challenging obstacles to affordable, highly effective birth control options.”

The University of Utah and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development funded the research. The University of Utah receives research funding from LARC manufacturers and one of the coauthors reported financial relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hormonal intrauterine devices inserted immediately postpartum had a nearly six times greater likelihood of expulsion compared with copper IUDs, but most women who requested any type of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) postpartum were still using it half a year later, a recent study found.

“With more than eight out of ten women continuing use at 6 months, in-hospital placement of postpartum LARC devices is a worthwhile intervention,” reported Jennifer L. Eggebroten, MD, and her associates at the University of Utah. “More than half of women who experienced IUD expulsion without commencement of another highly effective contraceptive went on to become pregnant within 2 years, highlighting the need for appropriate counseling prior to device placement and backup contraception planning.”

Ninety percent of the patients were Hispanic, 87% had prior children, and 87% had an income below $24,000. Most (77%) had a vaginal delivery. Those who requested the copper IUD tended to be older and have more children compared with those who asked for the hormonal IUD or implant.

Among the 289 patients who completed the 6 months of follow-up, 17% of those with a hormonal IUD had an expulsion, compared with 4% of women with copper IUDs. That translated to a 5.8 times greater risk of expulsion for hormonal IUDs than for copper ones after the researchers accounted for age, mode of delivery, parity, and any breastfeeding. Expulsion rates were statistically similar between those who had vaginal deliveries and those who had cesarean deliveries.

Just 8% of the women requested removal of their device during the 6 months of follow-up. Most (67%) of the 21 women who had expulsions asked for a replacement. Cost of the device delayed or prevented replacement in some cases. Over the next 2 years, 6 of the 11 women who did not get replacement devices became pregnant.

Meanwhile, 81% of women with a hormonal IUD (88% including replacements), 83% with a copper IUD (86% including replacements), and 90% with an implant were still using that device 6 months later. A quarter of the women who completed the study follow-up reported that they did not return to their providers for their postpartum exams.

“For patients at high risk of rapid repeat pregnancy or who may not return for a postpartum visit, the benefit of placement of a highly effective method of contraception in the hospital prior to discharge may outweigh the increased risk of expulsion,” the researchers wrote. “In some states, by 8 weeks, public insurance coverage may expire and women face much more challenging obstacles to affordable, highly effective birth control options.”

The University of Utah and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development funded the research. The University of Utah receives research funding from LARC manufacturers and one of the coauthors reported financial relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hormonal intrauterine devices inserted immediately postpartum had a nearly six times greater likelihood of expulsion compared with copper IUDs, but most women who requested any type of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) postpartum were still using it half a year later, a recent study found.

“With more than eight out of ten women continuing use at 6 months, in-hospital placement of postpartum LARC devices is a worthwhile intervention,” reported Jennifer L. Eggebroten, MD, and her associates at the University of Utah. “More than half of women who experienced IUD expulsion without commencement of another highly effective contraceptive went on to become pregnant within 2 years, highlighting the need for appropriate counseling prior to device placement and backup contraception planning.”

Ninety percent of the patients were Hispanic, 87% had prior children, and 87% had an income below $24,000. Most (77%) had a vaginal delivery. Those who requested the copper IUD tended to be older and have more children compared with those who asked for the hormonal IUD or implant.

Among the 289 patients who completed the 6 months of follow-up, 17% of those with a hormonal IUD had an expulsion, compared with 4% of women with copper IUDs. That translated to a 5.8 times greater risk of expulsion for hormonal IUDs than for copper ones after the researchers accounted for age, mode of delivery, parity, and any breastfeeding. Expulsion rates were statistically similar between those who had vaginal deliveries and those who had cesarean deliveries.

Just 8% of the women requested removal of their device during the 6 months of follow-up. Most (67%) of the 21 women who had expulsions asked for a replacement. Cost of the device delayed or prevented replacement in some cases. Over the next 2 years, 6 of the 11 women who did not get replacement devices became pregnant.

Meanwhile, 81% of women with a hormonal IUD (88% including replacements), 83% with a copper IUD (86% including replacements), and 90% with an implant were still using that device 6 months later. A quarter of the women who completed the study follow-up reported that they did not return to their providers for their postpartum exams.

“For patients at high risk of rapid repeat pregnancy or who may not return for a postpartum visit, the benefit of placement of a highly effective method of contraception in the hospital prior to discharge may outweigh the increased risk of expulsion,” the researchers wrote. “In some states, by 8 weeks, public insurance coverage may expire and women face much more challenging obstacles to affordable, highly effective birth control options.”

The University of Utah and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development funded the research. The University of Utah receives research funding from LARC manufacturers and one of the coauthors reported financial relationships with LARC manufacturers.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Hormonal IUDs were 5.8 times more likely to be expelled than were copper ones, but at least 80% of women who received a LARC still had it 6 months later.

Data source: A prospective cohort of 325 women who received a hormonal or copper IUD or a contraceptive implant immediately postpartum between October 2013 and February 2016.

Disclosures: The University of Utah and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development funded the research. The University of Utah receives research funding from LARC manufacturers and one of the coauthors reported financial relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Shingles vaccine deemed effective in people with autoimmune disease

The herpes zoster vaccine reduces the risk of shingles in older adults with autoimmune disease, even if they are taking immunosuppressants for their condition, but the protection begins to wane after about 5 years, a recent retrospective study found.

“There has been some concern that patients with autoimmune conditions might have a lower immunogenic response to herpes zoster vaccination, especially when treated with immunosuppressive medications such as glucocorticoids,” wrote Huifeng Yun, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and her colleagues.

The researchers used 2006-2013 Medicare data to calculate the risk of shingles among Medicare recipients who had an autoimmune disease and either did or did not receive the herpes zoster vaccine. All the patients had been enrolled in Medicare for at least 12 continuous months and had a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis.

The researchers matched 59,627 patients who received the herpes zoster vaccine with 119,254 unvaccinated patients, based on age, sex, race, calendar year, autoimmune disease type, and use of autoimmune drugs (biologics, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and glucocorticoids). During a follow-up of up to 7 years, the researchers additionally accounted for comorbid medical conditions and concurrent medications each year.

The cohort, with an average age of 73.5 years in both groups, included 53.1% of adults with rheumatoid arthritis, 31.6% with psoriasis, 20.9% with inflammatory bowel disease, 4.7% with psoriatic arthritis, and 1.4% with ankylosing spondylitis.

Those who received the vaccine had a rate of 0.75 herpes zoster cases per 100 people during the first year, which rose to 1.25 cases per 100 people per year at the seventh year after vaccination. The rate among unvaccinated individuals stayed steady at approximately 1.3-1.7 cases per 100 people per year throughout the study period. These rates, as expected, were approximately 50% higher than in the general population over age 70 without autoimmune disease.

Compared with unvaccinated individuals, vaccinated individuals had a reduced relative risk for shingles of 0.74-0.77 after adjustment for confounders, but the risk reduction only remained statistically significant for the first 5 years after vaccination.

The waning seen with the vaccine’s effectiveness “raises the possibility that patients might benefit from a booster vaccine at some point after initial vaccination, although no recommendation currently exists that would support such a practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Yun has received research funding from Amgen. Other authors disclosed ties to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, Janssen, and Pfizer. One author has received research support and consulting fees from Corrona. The study did not note an external source of funding.

The herpes zoster vaccine reduces the risk of shingles in older adults with autoimmune disease, even if they are taking immunosuppressants for their condition, but the protection begins to wane after about 5 years, a recent retrospective study found.

“There has been some concern that patients with autoimmune conditions might have a lower immunogenic response to herpes zoster vaccination, especially when treated with immunosuppressive medications such as glucocorticoids,” wrote Huifeng Yun, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and her colleagues.

The researchers used 2006-2013 Medicare data to calculate the risk of shingles among Medicare recipients who had an autoimmune disease and either did or did not receive the herpes zoster vaccine. All the patients had been enrolled in Medicare for at least 12 continuous months and had a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis.

The researchers matched 59,627 patients who received the herpes zoster vaccine with 119,254 unvaccinated patients, based on age, sex, race, calendar year, autoimmune disease type, and use of autoimmune drugs (biologics, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and glucocorticoids). During a follow-up of up to 7 years, the researchers additionally accounted for comorbid medical conditions and concurrent medications each year.

The cohort, with an average age of 73.5 years in both groups, included 53.1% of adults with rheumatoid arthritis, 31.6% with psoriasis, 20.9% with inflammatory bowel disease, 4.7% with psoriatic arthritis, and 1.4% with ankylosing spondylitis.

Those who received the vaccine had a rate of 0.75 herpes zoster cases per 100 people during the first year, which rose to 1.25 cases per 100 people per year at the seventh year after vaccination. The rate among unvaccinated individuals stayed steady at approximately 1.3-1.7 cases per 100 people per year throughout the study period. These rates, as expected, were approximately 50% higher than in the general population over age 70 without autoimmune disease.

Compared with unvaccinated individuals, vaccinated individuals had a reduced relative risk for shingles of 0.74-0.77 after adjustment for confounders, but the risk reduction only remained statistically significant for the first 5 years after vaccination.

The waning seen with the vaccine’s effectiveness “raises the possibility that patients might benefit from a booster vaccine at some point after initial vaccination, although no recommendation currently exists that would support such a practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Yun has received research funding from Amgen. Other authors disclosed ties to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, Janssen, and Pfizer. One author has received research support and consulting fees from Corrona. The study did not note an external source of funding.

The herpes zoster vaccine reduces the risk of shingles in older adults with autoimmune disease, even if they are taking immunosuppressants for their condition, but the protection begins to wane after about 5 years, a recent retrospective study found.

“There has been some concern that patients with autoimmune conditions might have a lower immunogenic response to herpes zoster vaccination, especially when treated with immunosuppressive medications such as glucocorticoids,” wrote Huifeng Yun, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and her colleagues.

The researchers used 2006-2013 Medicare data to calculate the risk of shingles among Medicare recipients who had an autoimmune disease and either did or did not receive the herpes zoster vaccine. All the patients had been enrolled in Medicare for at least 12 continuous months and had a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis.

The researchers matched 59,627 patients who received the herpes zoster vaccine with 119,254 unvaccinated patients, based on age, sex, race, calendar year, autoimmune disease type, and use of autoimmune drugs (biologics, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and glucocorticoids). During a follow-up of up to 7 years, the researchers additionally accounted for comorbid medical conditions and concurrent medications each year.

The cohort, with an average age of 73.5 years in both groups, included 53.1% of adults with rheumatoid arthritis, 31.6% with psoriasis, 20.9% with inflammatory bowel disease, 4.7% with psoriatic arthritis, and 1.4% with ankylosing spondylitis.

Those who received the vaccine had a rate of 0.75 herpes zoster cases per 100 people during the first year, which rose to 1.25 cases per 100 people per year at the seventh year after vaccination. The rate among unvaccinated individuals stayed steady at approximately 1.3-1.7 cases per 100 people per year throughout the study period. These rates, as expected, were approximately 50% higher than in the general population over age 70 without autoimmune disease.

Compared with unvaccinated individuals, vaccinated individuals had a reduced relative risk for shingles of 0.74-0.77 after adjustment for confounders, but the risk reduction only remained statistically significant for the first 5 years after vaccination.

The waning seen with the vaccine’s effectiveness “raises the possibility that patients might benefit from a booster vaccine at some point after initial vaccination, although no recommendation currently exists that would support such a practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Yun has received research funding from Amgen. Other authors disclosed ties to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, Janssen, and Pfizer. One author has received research support and consulting fees from Corrona. The study did not note an external source of funding.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Medicare patients with autoimmune disease had a 23%-26% reduced risk of shingles for 5 years after receiving the herpes zoster vaccine.

Data source: The findings are based on analysis of 2006-2013 Medicare data on 59,627 patients who received the herpes zoster vaccine and 119,254 patients who didn’t.

Disclosures: Dr. Yun has received research funding from Amgen. Other authors disclosed ties to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, Janssen, and Pfizer. One author has received research support and consulting fees from Corrona. The study did not note an external source of funding.

Adolescent opioid use common but decreasing

About a quarter of high school seniors have taken prescription opioids, medically or nonmedically, but exposures have declined over the past 2 years, according to a study.

“The recent declines in medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical use of prescribed opioids from 2013 through 2015 found in the current study coincide with similar recent declines in U.S. opioid analgesic prescribing,” reported Sean Esteban McCabe, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates (Pediatrics 2017 March 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2387). “Among adolescents who report both medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical use of prescribed opioids, medical use before initiating nonmedical use of prescribed opioids tended to be most prevalent, and this pattern may be driven by the one-third of adolescents who report nonmedical use of prescribed opioids involving leftover opioid medications from their own previous prescriptions.”

The researchers analyzed data from the Monitoring the Future study from 1976 through 2015, an annual cross-sectional survey of high school seniors from 135 public and private high schools in the United States. Cohorts were nationally representative and varied in size from 2,181 to 3,791 students.

Students were asked whether they had ever been prescribed opioids by a doctor and how often they had ever taken opioids nonmedically. The list of opioids included all the ones available that year, including Vicodin, OxyContin, Percodan, Percocet, Demerol, Ultram, methadone, morphine, opium, and codeine.

Use of opioids for any reason ranged from 16.5% to 24% over the 4 decades, with medical use ranging from a low of 8.5% in 2000 to a peak of 14.4% in 1989. Though 16% of teens had used medical opioids in 1976, prevalence rose to 20% in 1989, then dropped to 13% in 1997 and remained stable. Rates sharply increased to 20% in 2002 – the year Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet were included in the questions – and then began declining again in 2013.

Nonmedical use correlated with medical use though remained less prevalent throughout the study period. This correlation was stronger for males, who are more likely to use opioids recreationally, than for females, who are more likely to use them to self-treat pain, the authors wrote.

Both medical and nonmedical use were more prevalent among white students than black students, in line with previous research showing “health disparities for receiving prescription opioids among racial minority patients,” the authors wrote.

Black teens are more often motivated to use opioids for pain relief, suggesting that their lower exposure rates “could result from a lack of adequate treatment, insufficient availability, overprescribing among white populations or underprescribing among nonwhite populations,” they wrote.

One limitation of the study was that absent students or those who had dropped out have a higher risk of opioid use, thereby possibly contributing to underreporting.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The researchers had no disclosures.

This research is important because nonmedical use of prescribed opiates is believed to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality associated with opiates. The consistency of the Monitoring the Future survey provides a high-level view of opiate use across the country from 1975 to 2015. Although helpful, this perspective can obscure critically important changes in local areas or within specific populations.

It is important to recognize the strong relationship between opioid prescription and nonmedical opioid use. These findings support the policy recommendations to prescribe opioids only when patients have strong indications for opioids and no better treatment options are available.

We view the recent decrease in the medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical opioid use as an important finding, but there are significant small-area variations that would not appear in a national study. The epidemic of opioid use disproportionately affects some urban and more rural areas. Nonmedical use of prescribed opiates in general has become more common in rural areas. West Virginia, a predominantly rural state, has the highest rate of opioid overdose fatality in the country at 41.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2015. The state also has the second highest rate of opioid prescriptions per capita.

We are heartened to see a recent decrease, but we see it as a measured improvement. We understand that the appropriate use of opioids to manage pain can be helpful for our patients, but we must continue to search for solutions to the current crisis. Possible interventions include better education of our patients and families when we prescribe these drugs, better drug regulation, development of new affordable approaches to pain management that have lower potential for abuse, and accessible and affordable treatment programs for those already afflicted.

These comments were taken from an editorial published in Pediatrics by David A. Rosen, MD, FAAP, and Pamela J. Murray, MD, MHP, FAAP, both of West Virginia University in Morgantown. They reported having no disclosures or external funding.

This research is important because nonmedical use of prescribed opiates is believed to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality associated with opiates. The consistency of the Monitoring the Future survey provides a high-level view of opiate use across the country from 1975 to 2015. Although helpful, this perspective can obscure critically important changes in local areas or within specific populations.

It is important to recognize the strong relationship between opioid prescription and nonmedical opioid use. These findings support the policy recommendations to prescribe opioids only when patients have strong indications for opioids and no better treatment options are available.

We view the recent decrease in the medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical opioid use as an important finding, but there are significant small-area variations that would not appear in a national study. The epidemic of opioid use disproportionately affects some urban and more rural areas. Nonmedical use of prescribed opiates in general has become more common in rural areas. West Virginia, a predominantly rural state, has the highest rate of opioid overdose fatality in the country at 41.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2015. The state also has the second highest rate of opioid prescriptions per capita.

We are heartened to see a recent decrease, but we see it as a measured improvement. We understand that the appropriate use of opioids to manage pain can be helpful for our patients, but we must continue to search for solutions to the current crisis. Possible interventions include better education of our patients and families when we prescribe these drugs, better drug regulation, development of new affordable approaches to pain management that have lower potential for abuse, and accessible and affordable treatment programs for those already afflicted.

These comments were taken from an editorial published in Pediatrics by David A. Rosen, MD, FAAP, and Pamela J. Murray, MD, MHP, FAAP, both of West Virginia University in Morgantown. They reported having no disclosures or external funding.

This research is important because nonmedical use of prescribed opiates is believed to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality associated with opiates. The consistency of the Monitoring the Future survey provides a high-level view of opiate use across the country from 1975 to 2015. Although helpful, this perspective can obscure critically important changes in local areas or within specific populations.

It is important to recognize the strong relationship between opioid prescription and nonmedical opioid use. These findings support the policy recommendations to prescribe opioids only when patients have strong indications for opioids and no better treatment options are available.

We view the recent decrease in the medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical opioid use as an important finding, but there are significant small-area variations that would not appear in a national study. The epidemic of opioid use disproportionately affects some urban and more rural areas. Nonmedical use of prescribed opiates in general has become more common in rural areas. West Virginia, a predominantly rural state, has the highest rate of opioid overdose fatality in the country at 41.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2015. The state also has the second highest rate of opioid prescriptions per capita.

We are heartened to see a recent decrease, but we see it as a measured improvement. We understand that the appropriate use of opioids to manage pain can be helpful for our patients, but we must continue to search for solutions to the current crisis. Possible interventions include better education of our patients and families when we prescribe these drugs, better drug regulation, development of new affordable approaches to pain management that have lower potential for abuse, and accessible and affordable treatment programs for those already afflicted.

These comments were taken from an editorial published in Pediatrics by David A. Rosen, MD, FAAP, and Pamela J. Murray, MD, MHP, FAAP, both of West Virginia University in Morgantown. They reported having no disclosures or external funding.

About a quarter of high school seniors have taken prescription opioids, medically or nonmedically, but exposures have declined over the past 2 years, according to a study.

“The recent declines in medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical use of prescribed opioids from 2013 through 2015 found in the current study coincide with similar recent declines in U.S. opioid analgesic prescribing,” reported Sean Esteban McCabe, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates (Pediatrics 2017 March 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2387). “Among adolescents who report both medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical use of prescribed opioids, medical use before initiating nonmedical use of prescribed opioids tended to be most prevalent, and this pattern may be driven by the one-third of adolescents who report nonmedical use of prescribed opioids involving leftover opioid medications from their own previous prescriptions.”

The researchers analyzed data from the Monitoring the Future study from 1976 through 2015, an annual cross-sectional survey of high school seniors from 135 public and private high schools in the United States. Cohorts were nationally representative and varied in size from 2,181 to 3,791 students.

Students were asked whether they had ever been prescribed opioids by a doctor and how often they had ever taken opioids nonmedically. The list of opioids included all the ones available that year, including Vicodin, OxyContin, Percodan, Percocet, Demerol, Ultram, methadone, morphine, opium, and codeine.

Use of opioids for any reason ranged from 16.5% to 24% over the 4 decades, with medical use ranging from a low of 8.5% in 2000 to a peak of 14.4% in 1989. Though 16% of teens had used medical opioids in 1976, prevalence rose to 20% in 1989, then dropped to 13% in 1997 and remained stable. Rates sharply increased to 20% in 2002 – the year Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet were included in the questions – and then began declining again in 2013.

Nonmedical use correlated with medical use though remained less prevalent throughout the study period. This correlation was stronger for males, who are more likely to use opioids recreationally, than for females, who are more likely to use them to self-treat pain, the authors wrote.

Both medical and nonmedical use were more prevalent among white students than black students, in line with previous research showing “health disparities for receiving prescription opioids among racial minority patients,” the authors wrote.

Black teens are more often motivated to use opioids for pain relief, suggesting that their lower exposure rates “could result from a lack of adequate treatment, insufficient availability, overprescribing among white populations or underprescribing among nonwhite populations,” they wrote.

One limitation of the study was that absent students or those who had dropped out have a higher risk of opioid use, thereby possibly contributing to underreporting.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The researchers had no disclosures.

About a quarter of high school seniors have taken prescription opioids, medically or nonmedically, but exposures have declined over the past 2 years, according to a study.

“The recent declines in medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical use of prescribed opioids from 2013 through 2015 found in the current study coincide with similar recent declines in U.S. opioid analgesic prescribing,” reported Sean Esteban McCabe, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates (Pediatrics 2017 March 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2387). “Among adolescents who report both medical use of prescription opioids and nonmedical use of prescribed opioids, medical use before initiating nonmedical use of prescribed opioids tended to be most prevalent, and this pattern may be driven by the one-third of adolescents who report nonmedical use of prescribed opioids involving leftover opioid medications from their own previous prescriptions.”

The researchers analyzed data from the Monitoring the Future study from 1976 through 2015, an annual cross-sectional survey of high school seniors from 135 public and private high schools in the United States. Cohorts were nationally representative and varied in size from 2,181 to 3,791 students.

Students were asked whether they had ever been prescribed opioids by a doctor and how often they had ever taken opioids nonmedically. The list of opioids included all the ones available that year, including Vicodin, OxyContin, Percodan, Percocet, Demerol, Ultram, methadone, morphine, opium, and codeine.

Use of opioids for any reason ranged from 16.5% to 24% over the 4 decades, with medical use ranging from a low of 8.5% in 2000 to a peak of 14.4% in 1989. Though 16% of teens had used medical opioids in 1976, prevalence rose to 20% in 1989, then dropped to 13% in 1997 and remained stable. Rates sharply increased to 20% in 2002 – the year Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet were included in the questions – and then began declining again in 2013.

Nonmedical use correlated with medical use though remained less prevalent throughout the study period. This correlation was stronger for males, who are more likely to use opioids recreationally, than for females, who are more likely to use them to self-treat pain, the authors wrote.

Both medical and nonmedical use were more prevalent among white students than black students, in line with previous research showing “health disparities for receiving prescription opioids among racial minority patients,” the authors wrote.

Black teens are more often motivated to use opioids for pain relief, suggesting that their lower exposure rates “could result from a lack of adequate treatment, insufficient availability, overprescribing among white populations or underprescribing among nonwhite populations,” they wrote.

One limitation of the study was that absent students or those who had dropped out have a higher risk of opioid use, thereby possibly contributing to underreporting.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The researchers had no disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Teen opioid use began to decline from 2013 through 2015 but remains common.

Major finding: Prevalence of teens’ medical or nonmedical use of prescription opioids ranged from 16.5% to 24% between 1976 and 2015.

Data source: Analysis of 40 annual surveys of U.S. high school seniors from 1976 through 2015.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The researchers had no disclosures.

STD testing in youth hindered by confidentiality concerns

Adolescents and young adults on their parents’ health insurance plan are less likely to receive sexual preventive health care, such as sexual risk assessments and testing for sexually transmitted disease, a study found.

Further, teen girls (aged 15-17 years), were more than twice as likely to be tested for chlamydia if they met with their provider alone than if they did not, researchers found.

“Confidentiality issues, including concerns that parents might find out, might be barriers to the use of STD [sexually transmitted disease] services among some subpopulations,” Jami S. Leichliter, PhD, and colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention wrote. “Public health efforts to reduce these confidentiality concerns might be useful,” such as providers meeting privately for at least part of an appointment with an adolescent (MMWR. 2017 Mar 10;66[9]:237-41).

The researchers examined data collected from the 2013-2015 National Survey of Family Growth regarding sexual and reproductive health care experiences and behaviors of youth with sexual experience, specifically teens aged 15-17 and young adults aged 18-25 who were on their parents’ health plan. Sexual experience refers to having ever had vaginal, anal, or oral sex with any partner.

Overall, 12.7% of these youth avoided seeking care for sexual and reproductive health because they worried their parents could find out. For those aged 15-17 years, the rate was even higher, at 22.6%.

These concerns were also reflected in the overall prevalence of chlamydia screenings: Just 17.1% of young women who worried about confidentiality had been screened for chlamydia, compared with 38.7% of young women who did not report that concern.

The researchers also compared teens aged 15-17 who had and had not received a sexual risk assessment, which includes being asked by a provider about their (or their partners’) sexual orientation, number of sexual partners, condom use, and types of sex. Among teens who met with a provider alone in the past year, 71.1% reported receiving a sexual risk assessment, compared with about 36.6% who did not meet privately with a provider.

Similarly, 34.0% of teen girls (aged 15-17 years) who saw their provider alone were tested for chlamydia, compared with 14.9% who never met with their provider alone. Slightly more teen boys (13.6%) received STD testing if they met with their provider alone than if they didn’t (9.5%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report any disclosures.

Adolescents and young adults on their parents’ health insurance plan are less likely to receive sexual preventive health care, such as sexual risk assessments and testing for sexually transmitted disease, a study found.

Further, teen girls (aged 15-17 years), were more than twice as likely to be tested for chlamydia if they met with their provider alone than if they did not, researchers found.

“Confidentiality issues, including concerns that parents might find out, might be barriers to the use of STD [sexually transmitted disease] services among some subpopulations,” Jami S. Leichliter, PhD, and colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention wrote. “Public health efforts to reduce these confidentiality concerns might be useful,” such as providers meeting privately for at least part of an appointment with an adolescent (MMWR. 2017 Mar 10;66[9]:237-41).

The researchers examined data collected from the 2013-2015 National Survey of Family Growth regarding sexual and reproductive health care experiences and behaviors of youth with sexual experience, specifically teens aged 15-17 and young adults aged 18-25 who were on their parents’ health plan. Sexual experience refers to having ever had vaginal, anal, or oral sex with any partner.

Overall, 12.7% of these youth avoided seeking care for sexual and reproductive health because they worried their parents could find out. For those aged 15-17 years, the rate was even higher, at 22.6%.

These concerns were also reflected in the overall prevalence of chlamydia screenings: Just 17.1% of young women who worried about confidentiality had been screened for chlamydia, compared with 38.7% of young women who did not report that concern.

The researchers also compared teens aged 15-17 who had and had not received a sexual risk assessment, which includes being asked by a provider about their (or their partners’) sexual orientation, number of sexual partners, condom use, and types of sex. Among teens who met with a provider alone in the past year, 71.1% reported receiving a sexual risk assessment, compared with about 36.6% who did not meet privately with a provider.

Similarly, 34.0% of teen girls (aged 15-17 years) who saw their provider alone were tested for chlamydia, compared with 14.9% who never met with their provider alone. Slightly more teen boys (13.6%) received STD testing if they met with their provider alone than if they didn’t (9.5%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report any disclosures.

Adolescents and young adults on their parents’ health insurance plan are less likely to receive sexual preventive health care, such as sexual risk assessments and testing for sexually transmitted disease, a study found.

Further, teen girls (aged 15-17 years), were more than twice as likely to be tested for chlamydia if they met with their provider alone than if they did not, researchers found.

“Confidentiality issues, including concerns that parents might find out, might be barriers to the use of STD [sexually transmitted disease] services among some subpopulations,” Jami S. Leichliter, PhD, and colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention wrote. “Public health efforts to reduce these confidentiality concerns might be useful,” such as providers meeting privately for at least part of an appointment with an adolescent (MMWR. 2017 Mar 10;66[9]:237-41).

The researchers examined data collected from the 2013-2015 National Survey of Family Growth regarding sexual and reproductive health care experiences and behaviors of youth with sexual experience, specifically teens aged 15-17 and young adults aged 18-25 who were on their parents’ health plan. Sexual experience refers to having ever had vaginal, anal, or oral sex with any partner.

Overall, 12.7% of these youth avoided seeking care for sexual and reproductive health because they worried their parents could find out. For those aged 15-17 years, the rate was even higher, at 22.6%.

These concerns were also reflected in the overall prevalence of chlamydia screenings: Just 17.1% of young women who worried about confidentiality had been screened for chlamydia, compared with 38.7% of young women who did not report that concern.

The researchers also compared teens aged 15-17 who had and had not received a sexual risk assessment, which includes being asked by a provider about their (or their partners’) sexual orientation, number of sexual partners, condom use, and types of sex. Among teens who met with a provider alone in the past year, 71.1% reported receiving a sexual risk assessment, compared with about 36.6% who did not meet privately with a provider.

Similarly, 34.0% of teen girls (aged 15-17 years) who saw their provider alone were tested for chlamydia, compared with 14.9% who never met with their provider alone. Slightly more teen boys (13.6%) received STD testing if they met with their provider alone than if they didn’t (9.5%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report any disclosures.

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall, 12.7% of sexually experienced youths (aged 15-25 years) who were on their parents’ health plan would not seek sexual and reproductive health care because of confidentiality concerns.

Data source: Responses from sexually experienced youth aged 15-25 years provided during the 2013-2015 U.S. National Survey of Family Growth.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report any disclosures.

Synthetic cannabinoid use linked to multiple risk factors

An estimated 1 in 10 high school students uses synthetic cannabinoids, which are linked to multiple other risk behaviors, and use is more likely among students with depressive symptoms, marijuana use, and alcohol use, investigators in two studies reported.

Synthetic cannabinoids are structurally similar to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, but they may be more potent, with adverse health effects not seen with natural tetrahydrocannabinol in marijuana. These synthetic products are accessible to teens online, in convenience stores, and in smoke shops. Past research has suggested that adolescents aren’t aware of the possible negative effects of these products, such as tachycardia, hypertension, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, irritability, chest pain, hallucinations, confusion, and vertigo.

“Overall, we observed that ever use of synthetic cannabinoids was associated with the majority of health risk behaviors included in our study and that those associations tended to be more pronounced for ever use of synthetic cannabinoids than for ever use of marijuana only, particularly for substance use behaviors and sexual risk behaviors,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2017 March 13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2675).

Dr. Clayton’s team analyzed data from 15,624 students in grades 9-12 from the cross-sectional 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, including all 50 states and Washington. The questions asked about use of marijuana, synthetic cannabinoids, or both. The question about synthetic cannabinoids included reference to street names of the drug, such as K2, Spice, fake weed, King Kong, Yucatan Fire, Skunk, or Moon Rocks. Another three dozen questions asked about risk behaviors related to substance use, violence and injury, mental health, and sexual health.

The results revealed that 29% of students had ever used only marijuana and 9% had ever used synthetic cannabinoids. Most of the students, 61%, had never used either. Although 23% of marijuana users had used synthetic cannabinoids, nearly all (98%) of the cannabinoids users had used marijuana.

Compared with those who had used only marijuana, adolescents who had ever used synthetic cannabinoids were considerably more likely to engage in substance use (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] = 4.85 for current alcohol use; aPR =151.90 for ever use of heroin) or sexual risk behaviors (had sexual intercourse with four or more persons during their life; aPR = 6.20). They also were more than twice as likely to have tried marijuana before age 13 years (aPR = 2.35) and were more likely to have used marijuana at least once in the past month (aPR = 1.36) and to have used marijuana 20 or more times in the past month (aPR = 1.88).

“Youth may progress from marijuana use only to the use of synthetic cannabinoids for a variety of reasons, such as ease of access, perception of safety, and ability to be undetected by many drug tests,” Dr. Clayton and her associates wrote.

The second study found similar associations between marijuana use and later use of synthetic cannabinoids. Andrew L. Ninnemann of the University of Missouri–Columbia, and his associates collected data twice over a 12-month period from 964 high school students at seven public schools in Southeast Texas (Pediatrics. 2017 March 13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3009), to examine the relationship of synthetic cannabinoid use with anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and marijuana use.

The first assessment occurred in spring of 2011 and the second in spring of 2012. Most respondents (response rate, 62%) were sophomores (73%) or juniors (24%), with only 1% each of freshmen and seniors; 1% reported “other.” The sample included 31% African American students, 29% white students, 28% Hispanic students, and 12% of other ethnicities.

Males were more likely than females to use synthetic cannabinoids, and African American students were less likely to use them than teens of other ethnicities. Depression at baseline predicted use of synthetic cannabinoids a year later (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.42, P = .04), as did alcohol use (aOR = 1.85, P = .02), marijuana use (aOR = 2.47, P less than .001), and synthetic cannabinoid use at baseline (aOR = 2.36, P less than .001).

Students also were more likely to use marijuana at follow-up if they had used alcohol (aOR = 1.96, P less than .001) or marijuana (aOR = 4.52, P less than .001) at baseline. However, neither demographic variables nor anxiety, impulsivity, synthetic cannabinoid use, or other drug use significantly predicted marijuana use 1 year later.

Mr. Ninnemann’s study also found a slightly higher prevalence of synthetic cannabinoid use at baseline than the Clayton study did, with 13% of the Texas sample reporting use.

“The substantial risks associated with even a single episode of synthetic cannabinoid use emphasize the critical importance of identifying and targeting potential risk factors,” Mr. Ninnemann and his coauthors wrote. “Our findings indicate that prevention and intervention efforts may benefit from targeting depressive symptoms and alcohol and marijuana use to potentially reduce adolescent use of synthetic cannabinoids.”

Dr. Clayton and her colleagues mentioned a past study finding that 50% of elementary schools, 33% of middle schools, and 13% of high schools do not require instruction on alcohol or other drug use prevention. The U.S. trend of cannabis legalization also introduces uncertainty, the investigators noted.

“It is unclear what impact the legalization of marijuana will have on the use of synthetic cannabinoids,” Dr. Clayton’s team wrote. The evidence is contradictory on the likelihood of teens trying marijuana in these environments, but “there is a concern that if marijuana use increases, the use of synthetic marijuana may also increase,” they noted.

The Clayton study did not have external funding. The Ninnemann study received funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Justice. The authors of both studies reported that they had no disclosures.

Synthetic cannabinoids are made in a lab to have marijuanalike properties, but often have more short-term medical and behavioral toxicities. We at the University of Florida McKnight Brain Institute in Gainesville have studied bath salts and synthetics in the laboratory, but there have been few human studies. The current studies by Clayton et al. and Ninnemann et al., following shortly after the American Academy of Pediatrics warning about the effects of cannabis smoking in adolescents (Pediatrics. 2017 10.1542/peds.2016-4069), are a grim reminder that adolescence is a period of extreme vulnerability to drugs of abuse. Synthetic cannabinoids, as addiction specialists will attest, produce some signs and symptoms of cannabis intoxication, but often with more acute problems, with greater intensity, and of longer duration. In the current two studies, it is clear that the reported consequences of synthetic cannabinoids are greater in terms of risk behaviors and depression than in marijuana smokers.

Mark S. Gold, MD, is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. He also is chairman of the scientific advisory boards for RiverMend Health, Atlanta.

Synthetic cannabinoids are made in a lab to have marijuanalike properties, but often have more short-term medical and behavioral toxicities. We at the University of Florida McKnight Brain Institute in Gainesville have studied bath salts and synthetics in the laboratory, but there have been few human studies. The current studies by Clayton et al. and Ninnemann et al., following shortly after the American Academy of Pediatrics warning about the effects of cannabis smoking in adolescents (Pediatrics. 2017 10.1542/peds.2016-4069), are a grim reminder that adolescence is a period of extreme vulnerability to drugs of abuse. Synthetic cannabinoids, as addiction specialists will attest, produce some signs and symptoms of cannabis intoxication, but often with more acute problems, with greater intensity, and of longer duration. In the current two studies, it is clear that the reported consequences of synthetic cannabinoids are greater in terms of risk behaviors and depression than in marijuana smokers.

Mark S. Gold, MD, is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. He also is chairman of the scientific advisory boards for RiverMend Health, Atlanta.

Synthetic cannabinoids are made in a lab to have marijuanalike properties, but often have more short-term medical and behavioral toxicities. We at the University of Florida McKnight Brain Institute in Gainesville have studied bath salts and synthetics in the laboratory, but there have been few human studies. The current studies by Clayton et al. and Ninnemann et al., following shortly after the American Academy of Pediatrics warning about the effects of cannabis smoking in adolescents (Pediatrics. 2017 10.1542/peds.2016-4069), are a grim reminder that adolescence is a period of extreme vulnerability to drugs of abuse. Synthetic cannabinoids, as addiction specialists will attest, produce some signs and symptoms of cannabis intoxication, but often with more acute problems, with greater intensity, and of longer duration. In the current two studies, it is clear that the reported consequences of synthetic cannabinoids are greater in terms of risk behaviors and depression than in marijuana smokers.

Mark S. Gold, MD, is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. He also is chairman of the scientific advisory boards for RiverMend Health, Atlanta.

An estimated 1 in 10 high school students uses synthetic cannabinoids, which are linked to multiple other risk behaviors, and use is more likely among students with depressive symptoms, marijuana use, and alcohol use, investigators in two studies reported.

Synthetic cannabinoids are structurally similar to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, but they may be more potent, with adverse health effects not seen with natural tetrahydrocannabinol in marijuana. These synthetic products are accessible to teens online, in convenience stores, and in smoke shops. Past research has suggested that adolescents aren’t aware of the possible negative effects of these products, such as tachycardia, hypertension, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, irritability, chest pain, hallucinations, confusion, and vertigo.

“Overall, we observed that ever use of synthetic cannabinoids was associated with the majority of health risk behaviors included in our study and that those associations tended to be more pronounced for ever use of synthetic cannabinoids than for ever use of marijuana only, particularly for substance use behaviors and sexual risk behaviors,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2017 March 13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2675).

Dr. Clayton’s team analyzed data from 15,624 students in grades 9-12 from the cross-sectional 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, including all 50 states and Washington. The questions asked about use of marijuana, synthetic cannabinoids, or both. The question about synthetic cannabinoids included reference to street names of the drug, such as K2, Spice, fake weed, King Kong, Yucatan Fire, Skunk, or Moon Rocks. Another three dozen questions asked about risk behaviors related to substance use, violence and injury, mental health, and sexual health.

The results revealed that 29% of students had ever used only marijuana and 9% had ever used synthetic cannabinoids. Most of the students, 61%, had never used either. Although 23% of marijuana users had used synthetic cannabinoids, nearly all (98%) of the cannabinoids users had used marijuana.

Compared with those who had used only marijuana, adolescents who had ever used synthetic cannabinoids were considerably more likely to engage in substance use (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] = 4.85 for current alcohol use; aPR =151.90 for ever use of heroin) or sexual risk behaviors (had sexual intercourse with four or more persons during their life; aPR = 6.20). They also were more than twice as likely to have tried marijuana before age 13 years (aPR = 2.35) and were more likely to have used marijuana at least once in the past month (aPR = 1.36) and to have used marijuana 20 or more times in the past month (aPR = 1.88).

“Youth may progress from marijuana use only to the use of synthetic cannabinoids for a variety of reasons, such as ease of access, perception of safety, and ability to be undetected by many drug tests,” Dr. Clayton and her associates wrote.

The second study found similar associations between marijuana use and later use of synthetic cannabinoids. Andrew L. Ninnemann of the University of Missouri–Columbia, and his associates collected data twice over a 12-month period from 964 high school students at seven public schools in Southeast Texas (Pediatrics. 2017 March 13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3009), to examine the relationship of synthetic cannabinoid use with anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and marijuana use.

The first assessment occurred in spring of 2011 and the second in spring of 2012. Most respondents (response rate, 62%) were sophomores (73%) or juniors (24%), with only 1% each of freshmen and seniors; 1% reported “other.” The sample included 31% African American students, 29% white students, 28% Hispanic students, and 12% of other ethnicities.

Males were more likely than females to use synthetic cannabinoids, and African American students were less likely to use them than teens of other ethnicities. Depression at baseline predicted use of synthetic cannabinoids a year later (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.42, P = .04), as did alcohol use (aOR = 1.85, P = .02), marijuana use (aOR = 2.47, P less than .001), and synthetic cannabinoid use at baseline (aOR = 2.36, P less than .001).

Students also were more likely to use marijuana at follow-up if they had used alcohol (aOR = 1.96, P less than .001) or marijuana (aOR = 4.52, P less than .001) at baseline. However, neither demographic variables nor anxiety, impulsivity, synthetic cannabinoid use, or other drug use significantly predicted marijuana use 1 year later.

Mr. Ninnemann’s study also found a slightly higher prevalence of synthetic cannabinoid use at baseline than the Clayton study did, with 13% of the Texas sample reporting use.

“The substantial risks associated with even a single episode of synthetic cannabinoid use emphasize the critical importance of identifying and targeting potential risk factors,” Mr. Ninnemann and his coauthors wrote. “Our findings indicate that prevention and intervention efforts may benefit from targeting depressive symptoms and alcohol and marijuana use to potentially reduce adolescent use of synthetic cannabinoids.”

Dr. Clayton and her colleagues mentioned a past study finding that 50% of elementary schools, 33% of middle schools, and 13% of high schools do not require instruction on alcohol or other drug use prevention. The U.S. trend of cannabis legalization also introduces uncertainty, the investigators noted.

“It is unclear what impact the legalization of marijuana will have on the use of synthetic cannabinoids,” Dr. Clayton’s team wrote. The evidence is contradictory on the likelihood of teens trying marijuana in these environments, but “there is a concern that if marijuana use increases, the use of synthetic marijuana may also increase,” they noted.

The Clayton study did not have external funding. The Ninnemann study received funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Justice. The authors of both studies reported that they had no disclosures.

An estimated 1 in 10 high school students uses synthetic cannabinoids, which are linked to multiple other risk behaviors, and use is more likely among students with depressive symptoms, marijuana use, and alcohol use, investigators in two studies reported.

Synthetic cannabinoids are structurally similar to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, but they may be more potent, with adverse health effects not seen with natural tetrahydrocannabinol in marijuana. These synthetic products are accessible to teens online, in convenience stores, and in smoke shops. Past research has suggested that adolescents aren’t aware of the possible negative effects of these products, such as tachycardia, hypertension, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, irritability, chest pain, hallucinations, confusion, and vertigo.

“Overall, we observed that ever use of synthetic cannabinoids was associated with the majority of health risk behaviors included in our study and that those associations tended to be more pronounced for ever use of synthetic cannabinoids than for ever use of marijuana only, particularly for substance use behaviors and sexual risk behaviors,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2017 March 13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2675).

Dr. Clayton’s team analyzed data from 15,624 students in grades 9-12 from the cross-sectional 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, including all 50 states and Washington. The questions asked about use of marijuana, synthetic cannabinoids, or both. The question about synthetic cannabinoids included reference to street names of the drug, such as K2, Spice, fake weed, King Kong, Yucatan Fire, Skunk, or Moon Rocks. Another three dozen questions asked about risk behaviors related to substance use, violence and injury, mental health, and sexual health.

The results revealed that 29% of students had ever used only marijuana and 9% had ever used synthetic cannabinoids. Most of the students, 61%, had never used either. Although 23% of marijuana users had used synthetic cannabinoids, nearly all (98%) of the cannabinoids users had used marijuana.

Compared with those who had used only marijuana, adolescents who had ever used synthetic cannabinoids were considerably more likely to engage in substance use (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] = 4.85 for current alcohol use; aPR =151.90 for ever use of heroin) or sexual risk behaviors (had sexual intercourse with four or more persons during their life; aPR = 6.20). They also were more than twice as likely to have tried marijuana before age 13 years (aPR = 2.35) and were more likely to have used marijuana at least once in the past month (aPR = 1.36) and to have used marijuana 20 or more times in the past month (aPR = 1.88).

“Youth may progress from marijuana use only to the use of synthetic cannabinoids for a variety of reasons, such as ease of access, perception of safety, and ability to be undetected by many drug tests,” Dr. Clayton and her associates wrote.

The second study found similar associations between marijuana use and later use of synthetic cannabinoids. Andrew L. Ninnemann of the University of Missouri–Columbia, and his associates collected data twice over a 12-month period from 964 high school students at seven public schools in Southeast Texas (Pediatrics. 2017 March 13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3009), to examine the relationship of synthetic cannabinoid use with anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and marijuana use.

The first assessment occurred in spring of 2011 and the second in spring of 2012. Most respondents (response rate, 62%) were sophomores (73%) or juniors (24%), with only 1% each of freshmen and seniors; 1% reported “other.” The sample included 31% African American students, 29% white students, 28% Hispanic students, and 12% of other ethnicities.

Males were more likely than females to use synthetic cannabinoids, and African American students were less likely to use them than teens of other ethnicities. Depression at baseline predicted use of synthetic cannabinoids a year later (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.42, P = .04), as did alcohol use (aOR = 1.85, P = .02), marijuana use (aOR = 2.47, P less than .001), and synthetic cannabinoid use at baseline (aOR = 2.36, P less than .001).

Students also were more likely to use marijuana at follow-up if they had used alcohol (aOR = 1.96, P less than .001) or marijuana (aOR = 4.52, P less than .001) at baseline. However, neither demographic variables nor anxiety, impulsivity, synthetic cannabinoid use, or other drug use significantly predicted marijuana use 1 year later.

Mr. Ninnemann’s study also found a slightly higher prevalence of synthetic cannabinoid use at baseline than the Clayton study did, with 13% of the Texas sample reporting use.

“The substantial risks associated with even a single episode of synthetic cannabinoid use emphasize the critical importance of identifying and targeting potential risk factors,” Mr. Ninnemann and his coauthors wrote. “Our findings indicate that prevention and intervention efforts may benefit from targeting depressive symptoms and alcohol and marijuana use to potentially reduce adolescent use of synthetic cannabinoids.”

Dr. Clayton and her colleagues mentioned a past study finding that 50% of elementary schools, 33% of middle schools, and 13% of high schools do not require instruction on alcohol or other drug use prevention. The U.S. trend of cannabis legalization also introduces uncertainty, the investigators noted.

“It is unclear what impact the legalization of marijuana will have on the use of synthetic cannabinoids,” Dr. Clayton’s team wrote. The evidence is contradictory on the likelihood of teens trying marijuana in these environments, but “there is a concern that if marijuana use increases, the use of synthetic marijuana may also increase,” they noted.