User login

S-ICD ‘noninferior’ to transvenous-lead ICD in head-to-head PRAETORIAN trial

by turning in a “noninferior” performance when it was compared with transvenous-lead devices in a first-of-its-kind head-to-head study.

Patients implanted with the subcutaneous-lead S-ICD (Boston Scientific) defibrillator showed a 4-year risk for inappropriate shocks or device-related complications similar to that seen with standard transvenous-lead implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) in a randomized comparison.

At the same time, the S-ICD did its job by showing a highly significant three-fourths reduction in risk for lead-related complications, compared with ICDs with standard leads, in the trial with more than 800 patients, called PRAETORIAN.

The study population represented a mix of patients seen in “real-world” practice who have an ICD indication, of whom about two-thirds had ischemic cardiomyopathy, said Reinoud Knops, MD, PhD, Academic Medical Center, Hilversum, the Netherlands. About 80% received the devices for primary prevention.

Knops, the trial’s principal investigator, presented the results online May 8 as one of the Heart Rhythm Society 2020 Scientific Sessions virtual presentations.

“I think the PRAETORIAN trial has really shown now, in a conventional ICD population – the real-world patients that we treat with ICD therapy, the single-chamber ICD cohort – that the S-ICD is a really good alternative option,” he said to reporters during a media briefing.

“The main conclusion is that the S-ICD should be considered in all patients who need an ICD who do not have a pacing indication,” Knops said.

This latter part is critical, because the S-ICD does not provide pacing therapy, including antitachycardia pacing (ATP) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and the trial did not enter patients considered likely to benefit from it. For example, it excluded anyone with bradycardia or treatment-refractory monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and patients considered appropriate for CRT.

In fact, there are a lot reasons clinicians might prefer a transvenous-lead ICD over the S-ICD, observed Anne B. Curtis, MD, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, who is not associated with PRAETORIAN.

A transvenous-lead system might be preferred in older patients, those with heart failure, and those with a lot of comorbidities. “A lot of these patients already have cardiomyopathies, so they’re more likely to develop atrial fibrillation or a need for CRT,” conditions that might make a transvenous-lead system the better choice, Curtis told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“For a lot of patients, you’re always thinking that you may have a need for that kind of therapy.”

In contrast, younger patients who perhaps have survived cardiac arrest and probably don’t have heart failure, and so may be less likely to benefit from pacing therapy, Curtis said, “are the kind of patient who you would probably lean very strongly toward for an S-ICD rather than a transvenous ICD.”

Remaining patients, those who might be considered candidates for either kind of device, are actually “a fairly limited subset,” she said.

The trial randomized 849 patients in Europe and the United States, from March 2011 to January 2017, who had a class I or IIa indication for an ICD but no bradycardia or need for CRT or ATP, to be implanted with an S-ICD or a transvenous-lead ICD.

The rates of the primary end point, a composite of device-related complications and inappropriate shocks at a median follow-up of 4 years, were comparable, at 15.1% in the S-ICD group and 15.7% for those with transvenous-lead ICDs.

The incidence of device-related complications numerically favored the S-ICD group, and the incidence of inappropriate shocks numerically favored the transvenous-lead group, but neither difference reached significance.

Knops said the PRAETORIAN researchers are seeking addition funding to extend the follow-up to 8 years. “We will get more insight into the durability of the S-ICD when we follow these patients longer,” he told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The investigator-initiated trial received support from Boston Scientific. Knops discloses receiving consultancy fees and research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Cairdac, and holding stock options from AtaCor Medical.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

by turning in a “noninferior” performance when it was compared with transvenous-lead devices in a first-of-its-kind head-to-head study.

Patients implanted with the subcutaneous-lead S-ICD (Boston Scientific) defibrillator showed a 4-year risk for inappropriate shocks or device-related complications similar to that seen with standard transvenous-lead implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) in a randomized comparison.

At the same time, the S-ICD did its job by showing a highly significant three-fourths reduction in risk for lead-related complications, compared with ICDs with standard leads, in the trial with more than 800 patients, called PRAETORIAN.

The study population represented a mix of patients seen in “real-world” practice who have an ICD indication, of whom about two-thirds had ischemic cardiomyopathy, said Reinoud Knops, MD, PhD, Academic Medical Center, Hilversum, the Netherlands. About 80% received the devices for primary prevention.

Knops, the trial’s principal investigator, presented the results online May 8 as one of the Heart Rhythm Society 2020 Scientific Sessions virtual presentations.

“I think the PRAETORIAN trial has really shown now, in a conventional ICD population – the real-world patients that we treat with ICD therapy, the single-chamber ICD cohort – that the S-ICD is a really good alternative option,” he said to reporters during a media briefing.

“The main conclusion is that the S-ICD should be considered in all patients who need an ICD who do not have a pacing indication,” Knops said.

This latter part is critical, because the S-ICD does not provide pacing therapy, including antitachycardia pacing (ATP) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and the trial did not enter patients considered likely to benefit from it. For example, it excluded anyone with bradycardia or treatment-refractory monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and patients considered appropriate for CRT.

In fact, there are a lot reasons clinicians might prefer a transvenous-lead ICD over the S-ICD, observed Anne B. Curtis, MD, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, who is not associated with PRAETORIAN.

A transvenous-lead system might be preferred in older patients, those with heart failure, and those with a lot of comorbidities. “A lot of these patients already have cardiomyopathies, so they’re more likely to develop atrial fibrillation or a need for CRT,” conditions that might make a transvenous-lead system the better choice, Curtis told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“For a lot of patients, you’re always thinking that you may have a need for that kind of therapy.”

In contrast, younger patients who perhaps have survived cardiac arrest and probably don’t have heart failure, and so may be less likely to benefit from pacing therapy, Curtis said, “are the kind of patient who you would probably lean very strongly toward for an S-ICD rather than a transvenous ICD.”

Remaining patients, those who might be considered candidates for either kind of device, are actually “a fairly limited subset,” she said.

The trial randomized 849 patients in Europe and the United States, from March 2011 to January 2017, who had a class I or IIa indication for an ICD but no bradycardia or need for CRT or ATP, to be implanted with an S-ICD or a transvenous-lead ICD.

The rates of the primary end point, a composite of device-related complications and inappropriate shocks at a median follow-up of 4 years, were comparable, at 15.1% in the S-ICD group and 15.7% for those with transvenous-lead ICDs.

The incidence of device-related complications numerically favored the S-ICD group, and the incidence of inappropriate shocks numerically favored the transvenous-lead group, but neither difference reached significance.

Knops said the PRAETORIAN researchers are seeking addition funding to extend the follow-up to 8 years. “We will get more insight into the durability of the S-ICD when we follow these patients longer,” he told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The investigator-initiated trial received support from Boston Scientific. Knops discloses receiving consultancy fees and research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Cairdac, and holding stock options from AtaCor Medical.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

by turning in a “noninferior” performance when it was compared with transvenous-lead devices in a first-of-its-kind head-to-head study.

Patients implanted with the subcutaneous-lead S-ICD (Boston Scientific) defibrillator showed a 4-year risk for inappropriate shocks or device-related complications similar to that seen with standard transvenous-lead implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) in a randomized comparison.

At the same time, the S-ICD did its job by showing a highly significant three-fourths reduction in risk for lead-related complications, compared with ICDs with standard leads, in the trial with more than 800 patients, called PRAETORIAN.

The study population represented a mix of patients seen in “real-world” practice who have an ICD indication, of whom about two-thirds had ischemic cardiomyopathy, said Reinoud Knops, MD, PhD, Academic Medical Center, Hilversum, the Netherlands. About 80% received the devices for primary prevention.

Knops, the trial’s principal investigator, presented the results online May 8 as one of the Heart Rhythm Society 2020 Scientific Sessions virtual presentations.

“I think the PRAETORIAN trial has really shown now, in a conventional ICD population – the real-world patients that we treat with ICD therapy, the single-chamber ICD cohort – that the S-ICD is a really good alternative option,” he said to reporters during a media briefing.

“The main conclusion is that the S-ICD should be considered in all patients who need an ICD who do not have a pacing indication,” Knops said.

This latter part is critical, because the S-ICD does not provide pacing therapy, including antitachycardia pacing (ATP) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and the trial did not enter patients considered likely to benefit from it. For example, it excluded anyone with bradycardia or treatment-refractory monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and patients considered appropriate for CRT.

In fact, there are a lot reasons clinicians might prefer a transvenous-lead ICD over the S-ICD, observed Anne B. Curtis, MD, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, who is not associated with PRAETORIAN.

A transvenous-lead system might be preferred in older patients, those with heart failure, and those with a lot of comorbidities. “A lot of these patients already have cardiomyopathies, so they’re more likely to develop atrial fibrillation or a need for CRT,” conditions that might make a transvenous-lead system the better choice, Curtis told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“For a lot of patients, you’re always thinking that you may have a need for that kind of therapy.”

In contrast, younger patients who perhaps have survived cardiac arrest and probably don’t have heart failure, and so may be less likely to benefit from pacing therapy, Curtis said, “are the kind of patient who you would probably lean very strongly toward for an S-ICD rather than a transvenous ICD.”

Remaining patients, those who might be considered candidates for either kind of device, are actually “a fairly limited subset,” she said.

The trial randomized 849 patients in Europe and the United States, from March 2011 to January 2017, who had a class I or IIa indication for an ICD but no bradycardia or need for CRT or ATP, to be implanted with an S-ICD or a transvenous-lead ICD.

The rates of the primary end point, a composite of device-related complications and inappropriate shocks at a median follow-up of 4 years, were comparable, at 15.1% in the S-ICD group and 15.7% for those with transvenous-lead ICDs.

The incidence of device-related complications numerically favored the S-ICD group, and the incidence of inappropriate shocks numerically favored the transvenous-lead group, but neither difference reached significance.

Knops said the PRAETORIAN researchers are seeking addition funding to extend the follow-up to 8 years. “We will get more insight into the durability of the S-ICD when we follow these patients longer,” he told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The investigator-initiated trial received support from Boston Scientific. Knops discloses receiving consultancy fees and research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Cairdac, and holding stock options from AtaCor Medical.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Signature STEMI sign may be less diagnostic in the COVID-19 age

The signature electrocardiographic sign indicating ST-segment-elevation MI may be a less-consistent indicator of actual STEMI at a time when patients with COVID-19 have come to overwhelm many hospital ICUs.

Many of the 18 such patients identified at six New York City hospitals who showed ST-segment elevation on their 12-lead ECG in the city’s first month of fighting the pandemic turned out to be free of either obstructive coronary artery disease by angiography or of regional wall-motion abnormalities (RWMA) by ECG, according to a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Those 10 patients in the 18-case series were said to have noncoronary myocardial injury, perhaps from myocarditis – a prevalent feature of severe COVID-19 – and the remaining 8 patients with obstructive coronary artery disease, RWMA, or both were diagnosed with STEMI. Of the latter patients, six went to the cath lab and five of those underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, Sripal Bangalore, MD, MHA, of New York University, and colleagues reported.

In an interview, Dr. Bangalore framed the case-series report as a caution against substituting fibrinolytic therapy for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with STE while hospitals are unusually burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic and invasive procedures intensify the threat of SARS-CoV-2 exposure to clinicians.

The strategy was recently advanced as an option for highly selected patients in a statement from the American College of Cardiology and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI).

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the main reasons fibrinolytic therapy has been pushed is to reduce the exposure to the cath-lab staff,” Dr. Bangalore observed. “But if you pursue that route, it’s problematic because more than half may not have obstructive disease and fibrinolytic therapy may not help. And if you give them fibrinolytics, you’re potentially increasing their risk of bleeding complications.

“The take-home from these 18 patients is that it’s very difficult to guess who is going to have obstructive disease and who is going to have nonobstructive disease,” Dr. Bangalore said. “Maybe we should assess these patients with not just an ECG but with a quick echo, then make a decision. Our practice so far has been to take these patients to the cath lab.”

The ACC/SCAI statement proposed that “fibrinolysis can be considered an option for the relatively stable STEMI patient with active COVID-19” after careful consideration of possible patient benefit versus the risks of cath-lab personnel exposure to the virus.

Only six patients in the current series, including five in the STEMI group, are reported to have had chest pain at about the time of STE, observed Michael J. Blaha, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

So, he said in an interview, “one of their points is that you have to take ST elevations with a grain of salt in this [COVID-19] era, because there are a lot of people presenting with ST elevations in the absence of chest pain.”

That, and the high prevalence of nonobstructive disease in the series, indeed argues against the use of fibrinolytic therapy in such patients, Dr. Blaha said.

Normally, when there is STE, “the pretest probability of STEMI is so high, and if you can’t make it to the cath lab for some reason, sure, it makes sense to give lytics.” However, he said, “COVID-19 is changing the clinical landscape. Now, with a variety of virus-mediated myocardial injury presentations, including myocarditis, the pretest probability of MI is lower.”

The current report “confirms that, in the COVID era, ST elevations are not diagnostic for MI and must be considered within the totality of clinical evidence, and a conservative approach to going to the cath lab is probably warranted,” Dr. Blaha said in an interview.

However, with the reduced pretest probability of STE for STEMI, he agreed, “I almost don’t see any scenario where I’d be comfortable, based on ECG changes alone, giving lytics at this time.”

Dr. Bangalore pointed out that all of the 18 patients in the series had elevated levels of the fibrin degradation product D-dimer, a biomarker that reflects ongoing hemostatic activation. Levels were higher in the 8 patients who ultimately received a STEMI diagnosis than in the remaining 10 patients.

But COVID-19 patients in general may have elevated D-dimer and “a lot of microthrombi,” he said. “So the question is, are those microthrombi also causal for any of the ECG changes we are also seeing?”

Aside from microthrombi, global hypoxia and myocarditis could be other potential causes of STE in COVID-19 patients in the absence of STEMI, Dr. Bangalore proposed. “At this point we just generally don’t know.”

Dr. Bangalore reported no conflicts; disclosures for the other authors are available at nejm.org. Dr. Blaha disclosed receiving grants from Amgen and serving on advisory boards for Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The signature electrocardiographic sign indicating ST-segment-elevation MI may be a less-consistent indicator of actual STEMI at a time when patients with COVID-19 have come to overwhelm many hospital ICUs.

Many of the 18 such patients identified at six New York City hospitals who showed ST-segment elevation on their 12-lead ECG in the city’s first month of fighting the pandemic turned out to be free of either obstructive coronary artery disease by angiography or of regional wall-motion abnormalities (RWMA) by ECG, according to a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Those 10 patients in the 18-case series were said to have noncoronary myocardial injury, perhaps from myocarditis – a prevalent feature of severe COVID-19 – and the remaining 8 patients with obstructive coronary artery disease, RWMA, or both were diagnosed with STEMI. Of the latter patients, six went to the cath lab and five of those underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, Sripal Bangalore, MD, MHA, of New York University, and colleagues reported.

In an interview, Dr. Bangalore framed the case-series report as a caution against substituting fibrinolytic therapy for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with STE while hospitals are unusually burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic and invasive procedures intensify the threat of SARS-CoV-2 exposure to clinicians.

The strategy was recently advanced as an option for highly selected patients in a statement from the American College of Cardiology and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI).

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the main reasons fibrinolytic therapy has been pushed is to reduce the exposure to the cath-lab staff,” Dr. Bangalore observed. “But if you pursue that route, it’s problematic because more than half may not have obstructive disease and fibrinolytic therapy may not help. And if you give them fibrinolytics, you’re potentially increasing their risk of bleeding complications.

“The take-home from these 18 patients is that it’s very difficult to guess who is going to have obstructive disease and who is going to have nonobstructive disease,” Dr. Bangalore said. “Maybe we should assess these patients with not just an ECG but with a quick echo, then make a decision. Our practice so far has been to take these patients to the cath lab.”

The ACC/SCAI statement proposed that “fibrinolysis can be considered an option for the relatively stable STEMI patient with active COVID-19” after careful consideration of possible patient benefit versus the risks of cath-lab personnel exposure to the virus.

Only six patients in the current series, including five in the STEMI group, are reported to have had chest pain at about the time of STE, observed Michael J. Blaha, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

So, he said in an interview, “one of their points is that you have to take ST elevations with a grain of salt in this [COVID-19] era, because there are a lot of people presenting with ST elevations in the absence of chest pain.”

That, and the high prevalence of nonobstructive disease in the series, indeed argues against the use of fibrinolytic therapy in such patients, Dr. Blaha said.

Normally, when there is STE, “the pretest probability of STEMI is so high, and if you can’t make it to the cath lab for some reason, sure, it makes sense to give lytics.” However, he said, “COVID-19 is changing the clinical landscape. Now, with a variety of virus-mediated myocardial injury presentations, including myocarditis, the pretest probability of MI is lower.”

The current report “confirms that, in the COVID era, ST elevations are not diagnostic for MI and must be considered within the totality of clinical evidence, and a conservative approach to going to the cath lab is probably warranted,” Dr. Blaha said in an interview.

However, with the reduced pretest probability of STE for STEMI, he agreed, “I almost don’t see any scenario where I’d be comfortable, based on ECG changes alone, giving lytics at this time.”

Dr. Bangalore pointed out that all of the 18 patients in the series had elevated levels of the fibrin degradation product D-dimer, a biomarker that reflects ongoing hemostatic activation. Levels were higher in the 8 patients who ultimately received a STEMI diagnosis than in the remaining 10 patients.

But COVID-19 patients in general may have elevated D-dimer and “a lot of microthrombi,” he said. “So the question is, are those microthrombi also causal for any of the ECG changes we are also seeing?”

Aside from microthrombi, global hypoxia and myocarditis could be other potential causes of STE in COVID-19 patients in the absence of STEMI, Dr. Bangalore proposed. “At this point we just generally don’t know.”

Dr. Bangalore reported no conflicts; disclosures for the other authors are available at nejm.org. Dr. Blaha disclosed receiving grants from Amgen and serving on advisory boards for Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The signature electrocardiographic sign indicating ST-segment-elevation MI may be a less-consistent indicator of actual STEMI at a time when patients with COVID-19 have come to overwhelm many hospital ICUs.

Many of the 18 such patients identified at six New York City hospitals who showed ST-segment elevation on their 12-lead ECG in the city’s first month of fighting the pandemic turned out to be free of either obstructive coronary artery disease by angiography or of regional wall-motion abnormalities (RWMA) by ECG, according to a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Those 10 patients in the 18-case series were said to have noncoronary myocardial injury, perhaps from myocarditis – a prevalent feature of severe COVID-19 – and the remaining 8 patients with obstructive coronary artery disease, RWMA, or both were diagnosed with STEMI. Of the latter patients, six went to the cath lab and five of those underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, Sripal Bangalore, MD, MHA, of New York University, and colleagues reported.

In an interview, Dr. Bangalore framed the case-series report as a caution against substituting fibrinolytic therapy for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with STE while hospitals are unusually burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic and invasive procedures intensify the threat of SARS-CoV-2 exposure to clinicians.

The strategy was recently advanced as an option for highly selected patients in a statement from the American College of Cardiology and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI).

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the main reasons fibrinolytic therapy has been pushed is to reduce the exposure to the cath-lab staff,” Dr. Bangalore observed. “But if you pursue that route, it’s problematic because more than half may not have obstructive disease and fibrinolytic therapy may not help. And if you give them fibrinolytics, you’re potentially increasing their risk of bleeding complications.

“The take-home from these 18 patients is that it’s very difficult to guess who is going to have obstructive disease and who is going to have nonobstructive disease,” Dr. Bangalore said. “Maybe we should assess these patients with not just an ECG but with a quick echo, then make a decision. Our practice so far has been to take these patients to the cath lab.”

The ACC/SCAI statement proposed that “fibrinolysis can be considered an option for the relatively stable STEMI patient with active COVID-19” after careful consideration of possible patient benefit versus the risks of cath-lab personnel exposure to the virus.

Only six patients in the current series, including five in the STEMI group, are reported to have had chest pain at about the time of STE, observed Michael J. Blaha, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

So, he said in an interview, “one of their points is that you have to take ST elevations with a grain of salt in this [COVID-19] era, because there are a lot of people presenting with ST elevations in the absence of chest pain.”

That, and the high prevalence of nonobstructive disease in the series, indeed argues against the use of fibrinolytic therapy in such patients, Dr. Blaha said.

Normally, when there is STE, “the pretest probability of STEMI is so high, and if you can’t make it to the cath lab for some reason, sure, it makes sense to give lytics.” However, he said, “COVID-19 is changing the clinical landscape. Now, with a variety of virus-mediated myocardial injury presentations, including myocarditis, the pretest probability of MI is lower.”

The current report “confirms that, in the COVID era, ST elevations are not diagnostic for MI and must be considered within the totality of clinical evidence, and a conservative approach to going to the cath lab is probably warranted,” Dr. Blaha said in an interview.

However, with the reduced pretest probability of STE for STEMI, he agreed, “I almost don’t see any scenario where I’d be comfortable, based on ECG changes alone, giving lytics at this time.”

Dr. Bangalore pointed out that all of the 18 patients in the series had elevated levels of the fibrin degradation product D-dimer, a biomarker that reflects ongoing hemostatic activation. Levels were higher in the 8 patients who ultimately received a STEMI diagnosis than in the remaining 10 patients.

But COVID-19 patients in general may have elevated D-dimer and “a lot of microthrombi,” he said. “So the question is, are those microthrombi also causal for any of the ECG changes we are also seeing?”

Aside from microthrombi, global hypoxia and myocarditis could be other potential causes of STE in COVID-19 patients in the absence of STEMI, Dr. Bangalore proposed. “At this point we just generally don’t know.”

Dr. Bangalore reported no conflicts; disclosures for the other authors are available at nejm.org. Dr. Blaha disclosed receiving grants from Amgen and serving on advisory boards for Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

VICTORIA: Vericiguat seen as novel success in tough-to-treat, high-risk heart failure

Not too many years ago, clinicians who treat patients with heart failure, especially those at high risk for decompensation, lamented what seemed a dearth of new drug therapy options.

Now, with the toolbox brimming with new guideline-supported alternatives, .

Importantly, it entered an especially high-risk population with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); everyone in the trial had experienced a prior, usually quite recent, heart failure exacerbation.

In such patients, the addition of vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) to standard drug and device therapies was followed by a moderately but significantly reduced relative risk for the trial’s primary clinical endpoint over about 11 months.

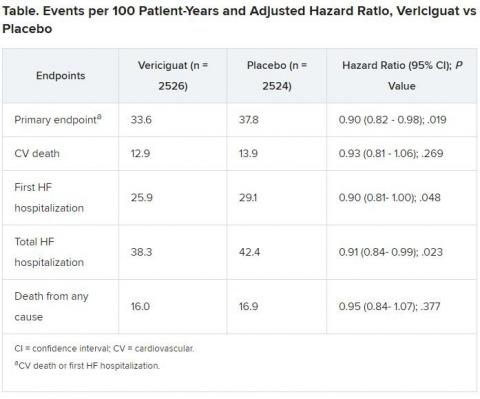

Recipients benefited with a 10% drop in adjusted risk (P = .019) for cardiovascular (CV) death or first heart failure hospitalization compared to a placebo control group.

But researchers leading the 5050-patient Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (VICTORIA), as well as unaffiliated experts who have studied the trial, say that in this case, risk reduction in absolute numbers is a more telling outcome.

“Remember who we’re talking about here in terms of the patients who have this degree of morbidity and mortality,” VICTORIA study chair Paul W. Armstrong, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, pointing to the “incredible placebo-group event rate and relatively modest follow-up of 10.8 months.”

The control group’s primary-endpoint event rate was 37.8 per 100 patient-years, 4.2 points higher than the rate for patients who received vericiguat. “And from there you get a number needed to treat of 24 to prevent one event, which is low,” Armstrong said.

“Think about the hundreds of thousands of people with this disease and what that means at the public health level.” About one in four patients with heart failure experience such exacerbations each year, he said.

Armstrong is lead author on the 42-country trial’s publication today in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his online presentation for the American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). The annual session was conducted virtually this year following the traditional live meeting’s cancelation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The VICTORIA presentation and publication flesh out the cursory top-line primary results that Merck unveiled in November 2019, which had not included the magnitude of the vericiguat relative benefit for the primary endpoint.

The trial represents “another win” for the treatment of heart failure, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, said as an invited discussant following Armstrong’s presentation.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

Symptomatic hypotension occurred in less than 10% and syncope in 4% or less of both groups; neither difference between the two groups was significant. Anemia developed more often in patients receiving vericiguat (7.6%) than in the control group (5.7%).

“We think that on balance, vericiguat is a useful alternative option for patients. But certainly the only thing we can say at this point is it works in the high-risk population that we studied,” Armstrong said. “Whether it works in lower-risk populations and how it compares is speculation, of course.”

The drug’s cost, whatever it might be if approved, is another factor affecting how it would be used, noted several observers.

“We don’t know what the cost-effectiveness will be. It should be reasonable because the benefit was on hospitalization. That’s a costly outcome,” Yancy said.

McMurray was also hopeful. “If the treatment is well tolerated and reasonably priced, it may still be a valuable asset for at least a subset of patients.”

VICTORIA was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp and Bayer AG. Armstrong discloses receiving research grants from Merck, Bayer AG, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and CSL Ltd and consulting fees from Merck, Bayer AG, AstraZeneca, and Novartis. Y ancy has previously disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Stevenson has previously disclosed receiving research grants from Novartis, consulting or serving on an advisory board for Abbott and travel expenses or meals from Novartis and St Jude Medical. McMurray has previously disclosed nonfinancial support or other support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cardiorentis, Amgen, Oxford University/Bayer, Theracos, AbbVie, DalCor, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Vifor-Fresenius.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Presented March 28, 2020. Session 402-08.

N Engl J Med. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text; Circulation. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Not too many years ago, clinicians who treat patients with heart failure, especially those at high risk for decompensation, lamented what seemed a dearth of new drug therapy options.

Now, with the toolbox brimming with new guideline-supported alternatives, .

Importantly, it entered an especially high-risk population with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); everyone in the trial had experienced a prior, usually quite recent, heart failure exacerbation.

In such patients, the addition of vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) to standard drug and device therapies was followed by a moderately but significantly reduced relative risk for the trial’s primary clinical endpoint over about 11 months.

Recipients benefited with a 10% drop in adjusted risk (P = .019) for cardiovascular (CV) death or first heart failure hospitalization compared to a placebo control group.

But researchers leading the 5050-patient Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (VICTORIA), as well as unaffiliated experts who have studied the trial, say that in this case, risk reduction in absolute numbers is a more telling outcome.

“Remember who we’re talking about here in terms of the patients who have this degree of morbidity and mortality,” VICTORIA study chair Paul W. Armstrong, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, pointing to the “incredible placebo-group event rate and relatively modest follow-up of 10.8 months.”

The control group’s primary-endpoint event rate was 37.8 per 100 patient-years, 4.2 points higher than the rate for patients who received vericiguat. “And from there you get a number needed to treat of 24 to prevent one event, which is low,” Armstrong said.

“Think about the hundreds of thousands of people with this disease and what that means at the public health level.” About one in four patients with heart failure experience such exacerbations each year, he said.

Armstrong is lead author on the 42-country trial’s publication today in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his online presentation for the American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). The annual session was conducted virtually this year following the traditional live meeting’s cancelation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The VICTORIA presentation and publication flesh out the cursory top-line primary results that Merck unveiled in November 2019, which had not included the magnitude of the vericiguat relative benefit for the primary endpoint.

The trial represents “another win” for the treatment of heart failure, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, said as an invited discussant following Armstrong’s presentation.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

Symptomatic hypotension occurred in less than 10% and syncope in 4% or less of both groups; neither difference between the two groups was significant. Anemia developed more often in patients receiving vericiguat (7.6%) than in the control group (5.7%).

“We think that on balance, vericiguat is a useful alternative option for patients. But certainly the only thing we can say at this point is it works in the high-risk population that we studied,” Armstrong said. “Whether it works in lower-risk populations and how it compares is speculation, of course.”

The drug’s cost, whatever it might be if approved, is another factor affecting how it would be used, noted several observers.

“We don’t know what the cost-effectiveness will be. It should be reasonable because the benefit was on hospitalization. That’s a costly outcome,” Yancy said.

McMurray was also hopeful. “If the treatment is well tolerated and reasonably priced, it may still be a valuable asset for at least a subset of patients.”

VICTORIA was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp and Bayer AG. Armstrong discloses receiving research grants from Merck, Bayer AG, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and CSL Ltd and consulting fees from Merck, Bayer AG, AstraZeneca, and Novartis. Y ancy has previously disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Stevenson has previously disclosed receiving research grants from Novartis, consulting or serving on an advisory board for Abbott and travel expenses or meals from Novartis and St Jude Medical. McMurray has previously disclosed nonfinancial support or other support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cardiorentis, Amgen, Oxford University/Bayer, Theracos, AbbVie, DalCor, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Vifor-Fresenius.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Presented March 28, 2020. Session 402-08.

N Engl J Med. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text; Circulation. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Not too many years ago, clinicians who treat patients with heart failure, especially those at high risk for decompensation, lamented what seemed a dearth of new drug therapy options.

Now, with the toolbox brimming with new guideline-supported alternatives, .

Importantly, it entered an especially high-risk population with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); everyone in the trial had experienced a prior, usually quite recent, heart failure exacerbation.

In such patients, the addition of vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) to standard drug and device therapies was followed by a moderately but significantly reduced relative risk for the trial’s primary clinical endpoint over about 11 months.

Recipients benefited with a 10% drop in adjusted risk (P = .019) for cardiovascular (CV) death or first heart failure hospitalization compared to a placebo control group.

But researchers leading the 5050-patient Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (VICTORIA), as well as unaffiliated experts who have studied the trial, say that in this case, risk reduction in absolute numbers is a more telling outcome.

“Remember who we’re talking about here in terms of the patients who have this degree of morbidity and mortality,” VICTORIA study chair Paul W. Armstrong, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, pointing to the “incredible placebo-group event rate and relatively modest follow-up of 10.8 months.”

The control group’s primary-endpoint event rate was 37.8 per 100 patient-years, 4.2 points higher than the rate for patients who received vericiguat. “And from there you get a number needed to treat of 24 to prevent one event, which is low,” Armstrong said.

“Think about the hundreds of thousands of people with this disease and what that means at the public health level.” About one in four patients with heart failure experience such exacerbations each year, he said.

Armstrong is lead author on the 42-country trial’s publication today in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his online presentation for the American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). The annual session was conducted virtually this year following the traditional live meeting’s cancelation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The VICTORIA presentation and publication flesh out the cursory top-line primary results that Merck unveiled in November 2019, which had not included the magnitude of the vericiguat relative benefit for the primary endpoint.

The trial represents “another win” for the treatment of heart failure, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, said as an invited discussant following Armstrong’s presentation.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

Symptomatic hypotension occurred in less than 10% and syncope in 4% or less of both groups; neither difference between the two groups was significant. Anemia developed more often in patients receiving vericiguat (7.6%) than in the control group (5.7%).

“We think that on balance, vericiguat is a useful alternative option for patients. But certainly the only thing we can say at this point is it works in the high-risk population that we studied,” Armstrong said. “Whether it works in lower-risk populations and how it compares is speculation, of course.”

The drug’s cost, whatever it might be if approved, is another factor affecting how it would be used, noted several observers.

“We don’t know what the cost-effectiveness will be. It should be reasonable because the benefit was on hospitalization. That’s a costly outcome,” Yancy said.

McMurray was also hopeful. “If the treatment is well tolerated and reasonably priced, it may still be a valuable asset for at least a subset of patients.”

VICTORIA was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp and Bayer AG. Armstrong discloses receiving research grants from Merck, Bayer AG, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and CSL Ltd and consulting fees from Merck, Bayer AG, AstraZeneca, and Novartis. Y ancy has previously disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Stevenson has previously disclosed receiving research grants from Novartis, consulting or serving on an advisory board for Abbott and travel expenses or meals from Novartis and St Jude Medical. McMurray has previously disclosed nonfinancial support or other support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cardiorentis, Amgen, Oxford University/Bayer, Theracos, AbbVie, DalCor, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Vifor-Fresenius.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Presented March 28, 2020. Session 402-08.

N Engl J Med. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text; Circulation. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prescription cascade more likely after CCBs than other hypertension meds

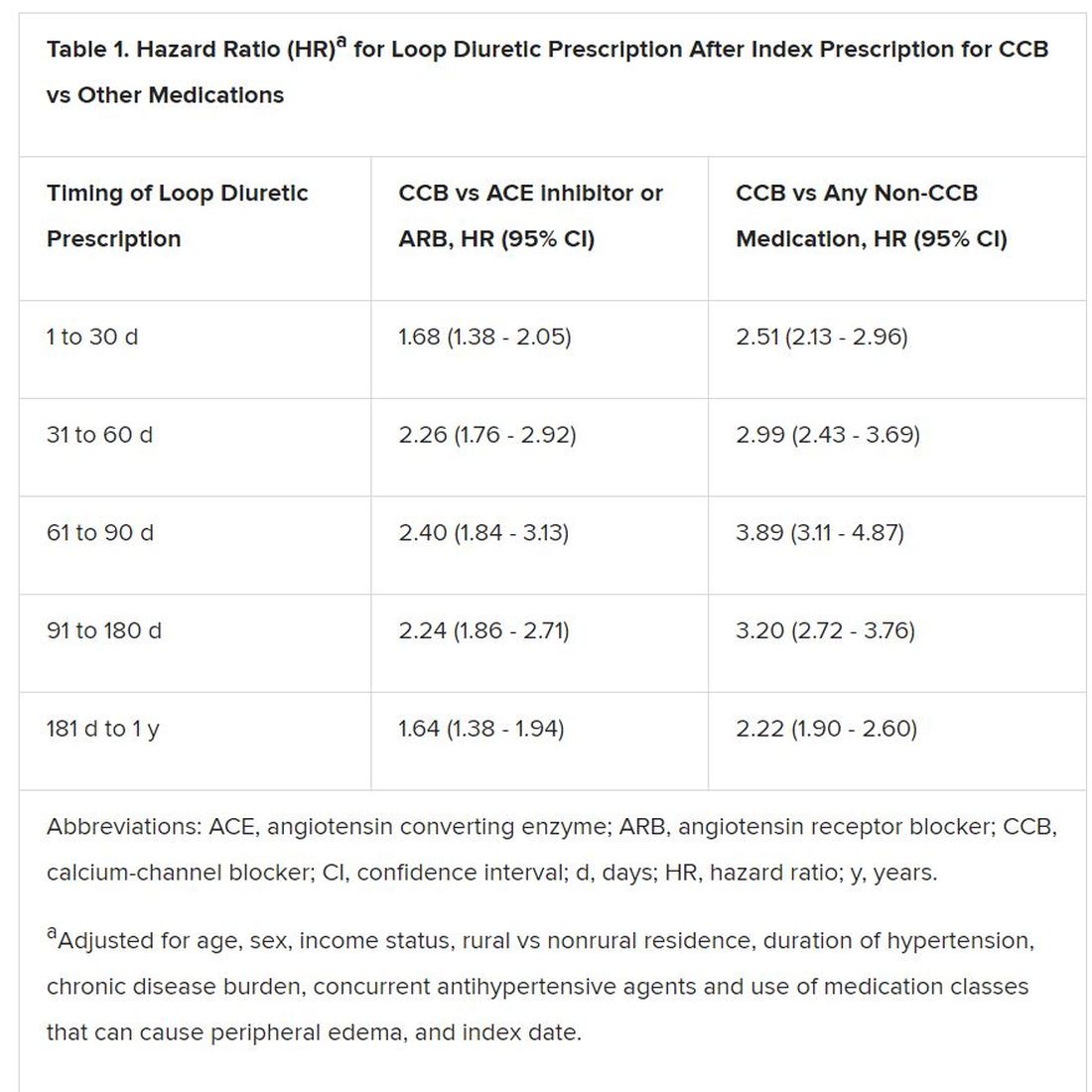

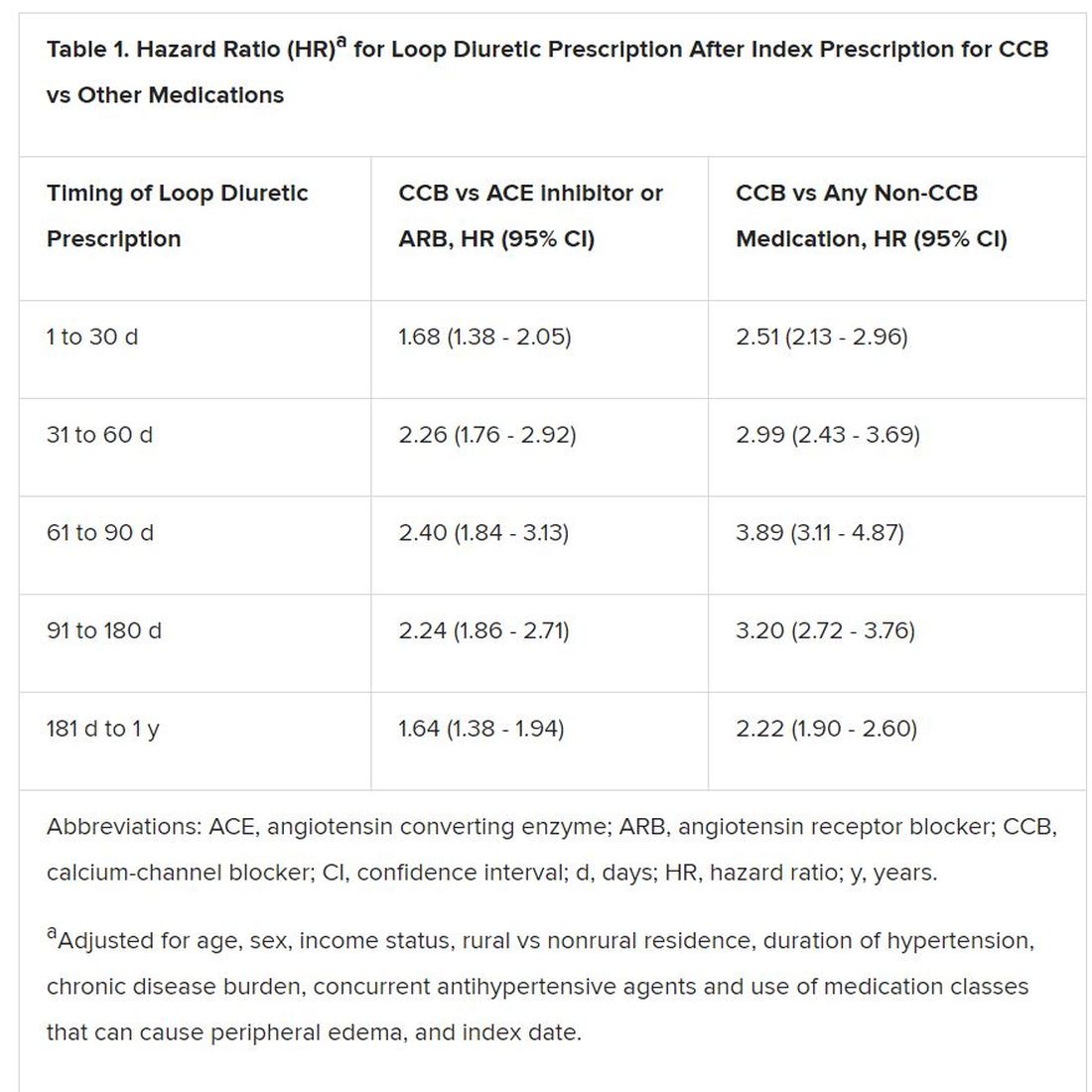

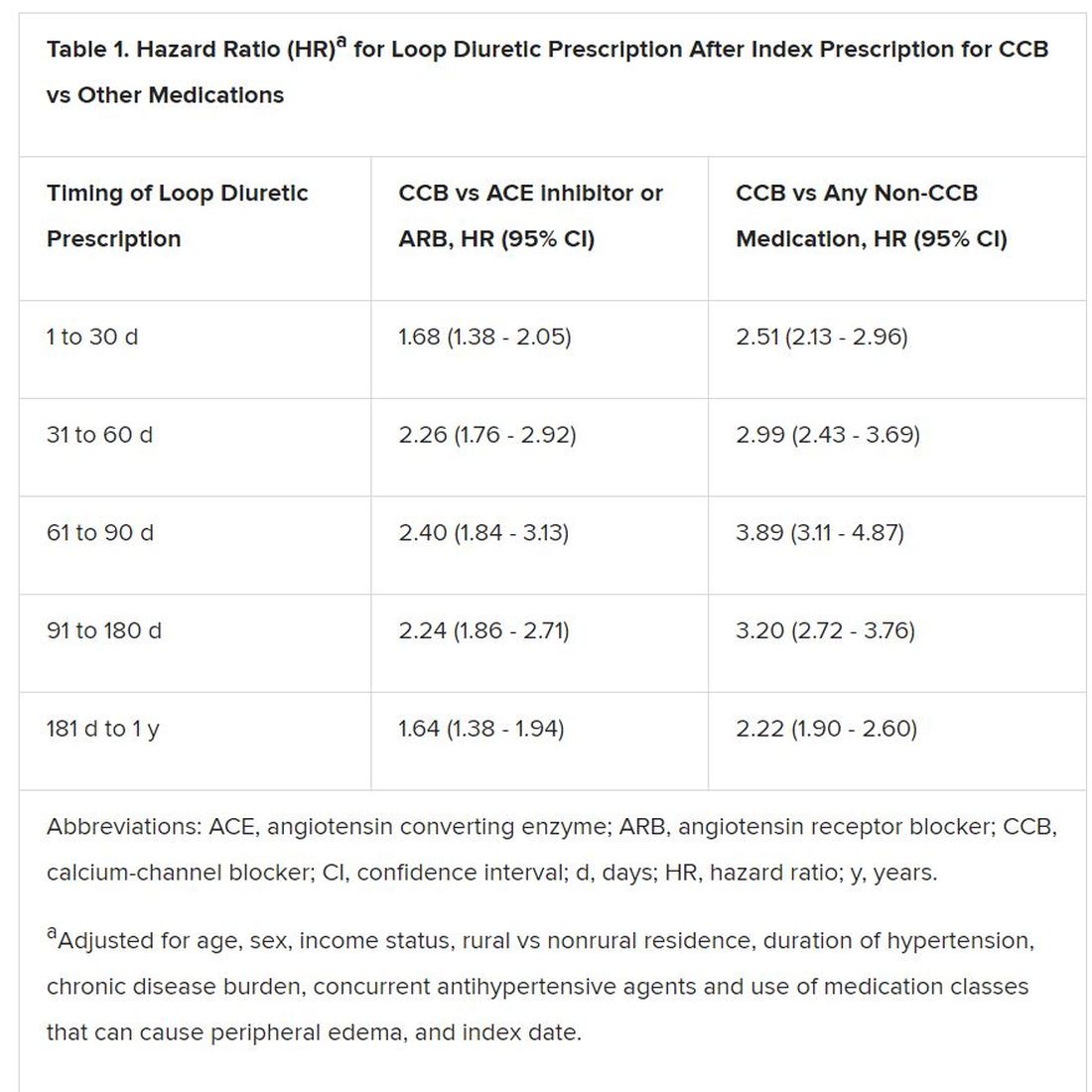

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.

That was unexpected, McCarthy observed, because “peripheral edema occurs more commonly in people taking dihydropyridine CCBs, like amlodipine, compared to non–dihydropyridine CCBs, such as verapamil and diltiazem.”

Savage, McCarthy, their coauthors, and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Elderly adults with hypertension who are newly prescribed a calcium-channel blocker (CCB), compared to other antihypertensive agents, are at least twice as likely to be given a loop diuretic over the following months, a large cohort study suggests.

The likelihood remained elevated for as long as a year after the start of a CCB and was more pronounced when comparing CCBs to any other kind of medication.

“Our findings suggest that many older adults who begin taking a CCB may subsequently experience a prescribing cascade” when loop diuretics are prescribed for peripheral edema, a known CCB adverse effect, that is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, Rachel D. Savage, PhD, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

Edema caused by CCBs is caused by fluid redistribution, not overload, and “treating euvolemic individuals with a diuretic places them at increased risk of overdiuresis, leading to falls, urinary incontinence, acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalances, and a cascade of other downstream consequences to which older adults are especially vulnerable,” explain Savage and coauthors of the analysis published online February 24 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

However, 1.4% of the cohort had been prescribed a loop diuretic, and 4.5% had been given any diuretic within 90 days after the start of CCBs. The corresponding rates were 0.7% and 3.4%, respectively, for patients who had started on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) rather than a CCB.

Also, Savage observed, “the likelihood of being prescribed a loop diuretic following initiation of a CCB changed over time and was greatest 61 to 90 days postinitiation.” At that point, it was increased 2.4 times compared with initiation of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB in an adjusted analysis and increased almost 4 times compared with starting on any non-CCB agent.

Importantly, the actual prevalence of peripheral edema among those started on CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or any non-CCB medication was not available in the data sets.

However, “the main message for clinicians is to consider medication side effects as a potential cause for new symptoms when patients present. We also encourage patients to ask prescribers about whether new symptoms could be caused by a medication,” senior author Lisa M. McCarthy, PharmD, told theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology.

“If a patient experiences peripheral edema while taking a CCB, we would encourage clinicians to consider whether the calcium-channel blocker is still necessary, whether it could be discontinued or the dose reduced, or whether the patient can be switched to another therapy,” she said.

Based on the current analysis, if the rate of CCB-induced peripheral edema is assumed to be 10%, which is consistent with the literature, then “potentially 7% to 14% of people who develop edema while taking a calcium channel blocker may then receive a loop diuretic,” an accompanying editorial notes.

“Patients with polypharmacy are at heightened risk of being exposed to [a] series of prescribing cascades if their current use of medications is not carefully discussed before the decision to add a new antihypertensive,” observe Timothy S. Anderson, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and Michael A. Steinman, MD, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco.

“The initial prescribing cascade can set off many other negative consequences, including adverse drug events, potentially avoidable diagnostic testing, and hospitalizations,” the editorialists caution.

“Identifying prescribing cascades and their consequences is an important step to stem the tide of polypharmacy and inform deprescribing efforts.”

The analysis was based on administrative data from almost 340,000 adults in the community aged 66 years or older with hypertension and new drug prescriptions over 5 years ending in September 2016, the report notes. Their mean age was 74.5 years and 56.5% were women.

The data set included 41,086 patients who were newly prescribed a CCB; 66,494 who were newly prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB; and 231,439 newly prescribed any medication other than a CCB. The prescribed CCB was amlodipine in 79.6% of patients.

Although loop diuretics could possibly have been prescribed sometimes as a second-tier antihypertensive in the absence of peripheral edema, “we made efforts, through the design of our study, to limit this where possible,” Savage said in an interview.

For example, the focus was on loop diuretics, which aren’t generally recommended for blood-pressure lowering. Also, patients with heart failure and those with a recent history of diuretic or other antihypertensive medication use had been excluded, she said.

“As such, our cohort comprised individuals with new-onset or milder hypertension for whom diuretics would unlikely to be prescribed as part of guideline-based hypertension management.”

Although amlodipine was the most commonly prescribed CCB, the potential for a prescribing cascade seemed to be a class effect and to apply at a range of dosages.