User login

Proposed triple I criteria may overlook febrile women at risk post partum

A large proportion of laboring febrile women are not meeting proposed criteria for intrauterine inflammation or infection or both (triple I), but still may be at risk, according to an analysis of expert recommendations for clinical diagnosis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Our data suggest caution in universal implementation of the triple I criteria to guide clinical management of febrile women in the intrapartum period,” according to lead author Samsiya Ona, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

In early 2015, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) established criteria for diagnosing triple I in an effort to “decrease overtreatment of intrapartum women and low-risk newborns.” To assess the validity of those criteria, Dr. Ona and her colleagues analyzed 339 women with a temperature taken of 100.4°F or greater (38.0°C) during labor or within 1 hour post partum from June 2015 to September 2017.

The women were split into two groups: 212 met criteria for suspected triple I (documented fever plus clinical signs of intrauterine infection such as maternal leukocytosis greater than 15,000 per mm3, fetal tachycardia greater than 160 beats per minute, and purulent amniotic fluid) and 127 met criteria for isolated maternal fever. Among the suspected triple I group, incidence of adverse clinical infectious outcomes was 12%, comparable with 10% in the isolated maternal fever group (P = .50). When it came to predicting confirmed triple I, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 71% (95% confidence interval, 61.4%-80.1%) and 41% (95% CI, 33.6%-47.8%), respectively. For predicting adverse clinical infectious outcomes, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 68% (95% CI, 50.2%-82.0%) and 38% (95% CI, 32.6%-43.8%).

The authors cited among study limitations their including only women who had blood cultures sent at initial fever and excluding women who did not have repeat febrile temperature taken within 45 minutes. However, they noted the benefits of working with “a unique, large database with physiologic, laboratory, and microbiological parameters” and emphasized the need for an improved method of diagnosis, suggesting “a simple bedside minimally invasive marker of infection may be ideal.”

The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

A large proportion of laboring febrile women are not meeting proposed criteria for intrauterine inflammation or infection or both (triple I), but still may be at risk, according to an analysis of expert recommendations for clinical diagnosis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Our data suggest caution in universal implementation of the triple I criteria to guide clinical management of febrile women in the intrapartum period,” according to lead author Samsiya Ona, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

In early 2015, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) established criteria for diagnosing triple I in an effort to “decrease overtreatment of intrapartum women and low-risk newborns.” To assess the validity of those criteria, Dr. Ona and her colleagues analyzed 339 women with a temperature taken of 100.4°F or greater (38.0°C) during labor or within 1 hour post partum from June 2015 to September 2017.

The women were split into two groups: 212 met criteria for suspected triple I (documented fever plus clinical signs of intrauterine infection such as maternal leukocytosis greater than 15,000 per mm3, fetal tachycardia greater than 160 beats per minute, and purulent amniotic fluid) and 127 met criteria for isolated maternal fever. Among the suspected triple I group, incidence of adverse clinical infectious outcomes was 12%, comparable with 10% in the isolated maternal fever group (P = .50). When it came to predicting confirmed triple I, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 71% (95% confidence interval, 61.4%-80.1%) and 41% (95% CI, 33.6%-47.8%), respectively. For predicting adverse clinical infectious outcomes, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 68% (95% CI, 50.2%-82.0%) and 38% (95% CI, 32.6%-43.8%).

The authors cited among study limitations their including only women who had blood cultures sent at initial fever and excluding women who did not have repeat febrile temperature taken within 45 minutes. However, they noted the benefits of working with “a unique, large database with physiologic, laboratory, and microbiological parameters” and emphasized the need for an improved method of diagnosis, suggesting “a simple bedside minimally invasive marker of infection may be ideal.”

The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

A large proportion of laboring febrile women are not meeting proposed criteria for intrauterine inflammation or infection or both (triple I), but still may be at risk, according to an analysis of expert recommendations for clinical diagnosis published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Our data suggest caution in universal implementation of the triple I criteria to guide clinical management of febrile women in the intrapartum period,” according to lead author Samsiya Ona, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

In early 2015, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) established criteria for diagnosing triple I in an effort to “decrease overtreatment of intrapartum women and low-risk newborns.” To assess the validity of those criteria, Dr. Ona and her colleagues analyzed 339 women with a temperature taken of 100.4°F or greater (38.0°C) during labor or within 1 hour post partum from June 2015 to September 2017.

The women were split into two groups: 212 met criteria for suspected triple I (documented fever plus clinical signs of intrauterine infection such as maternal leukocytosis greater than 15,000 per mm3, fetal tachycardia greater than 160 beats per minute, and purulent amniotic fluid) and 127 met criteria for isolated maternal fever. Among the suspected triple I group, incidence of adverse clinical infectious outcomes was 12%, comparable with 10% in the isolated maternal fever group (P = .50). When it came to predicting confirmed triple I, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 71% (95% confidence interval, 61.4%-80.1%) and 41% (95% CI, 33.6%-47.8%), respectively. For predicting adverse clinical infectious outcomes, the sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria were 68% (95% CI, 50.2%-82.0%) and 38% (95% CI, 32.6%-43.8%).

The authors cited among study limitations their including only women who had blood cultures sent at initial fever and excluding women who did not have repeat febrile temperature taken within 45 minutes. However, they noted the benefits of working with “a unique, large database with physiologic, laboratory, and microbiological parameters” and emphasized the need for an improved method of diagnosis, suggesting “a simple bedside minimally invasive marker of infection may be ideal.”

The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The sensitivity and specificity of the suspected triple I criteria to predict an adverse clinical infectious outcome were 68% for the suspected triple I group and 38% for the isolated maternal fever group.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 339 women with intrapartum fever from June 2015 to September 2017.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an Expanding the Boundaries Faculty Grant from the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Ona S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003008.

Differences in gut bacteria can distinguish IBD from IBS

Thanks to shotgun metagenomic sequencing of gut microbiota, physicians are on track to more easily distinguish inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), according to an analysis of stool samples from patients with the two common gastrointestinal diseases.

“The integration of these datasets allowed us to pinpoint key species as targets for functional studies in IBD and IBS and to connect knowledge of the etiology and pathogenesis of IBD and IBS with the gut microbiome to provide potential new targets for treatment,” wrote Arnau Vich Vila, of the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, and his coauthors. The report is in Science Translational Medicine.

Stool samples from 1,792 participants were analyzed: 355 from patients with IBD, 412 from patients with IBS, and 1,025 from the control group. The researchers found 24 bacterial taxa associated with both IBD and IBS and specific species that accompanied specific diseases, such as an abundance of Bacteroides in patients with IBD and Firmicutes in patients with IBS. In addition, their predictive model to distinguish IBD from IBS via gut microbial composition data [area under the curve (AUC) mean = 0.91 (0.81 to 0.99)] proved more accurate than did current fecal biomarker calprotectin [AUC mean = 0.80 (0.71 to 0.88); P = .002].

The authors acknowledged additional evidence that will be needed before these results can be translated to clinical practice, including supporting their described microbial pathways with metatranscriptomics and metabolomics data as well as functional experiments. They also observed that their predictive model will need to be validated through replication of their findings in patients with other gastrointestinal disorders or prediagnostic groups. They noted that their analysis benefited from being able to correct for confounding factors such as medication use, which is “essential for identifying disease-associated microbial features and avoiding false-positive associations due to changes in GI acidity or bowel mobility.”

One author reported receiving speaker fees from AbbVie and was a shareholder of the health care IT company Aceso BV and of Floris Medical Holding BV. Another author declared unrestricted research grants from AbbVie, Takeda, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals, is on the advisory boards for Mundipharma and Pharmacosmos, and has received speaker fees from Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. A third author declared consulting work for Takeda. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vich Vila A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap8914.

Thanks to shotgun metagenomic sequencing of gut microbiota, physicians are on track to more easily distinguish inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), according to an analysis of stool samples from patients with the two common gastrointestinal diseases.

“The integration of these datasets allowed us to pinpoint key species as targets for functional studies in IBD and IBS and to connect knowledge of the etiology and pathogenesis of IBD and IBS with the gut microbiome to provide potential new targets for treatment,” wrote Arnau Vich Vila, of the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, and his coauthors. The report is in Science Translational Medicine.

Stool samples from 1,792 participants were analyzed: 355 from patients with IBD, 412 from patients with IBS, and 1,025 from the control group. The researchers found 24 bacterial taxa associated with both IBD and IBS and specific species that accompanied specific diseases, such as an abundance of Bacteroides in patients with IBD and Firmicutes in patients with IBS. In addition, their predictive model to distinguish IBD from IBS via gut microbial composition data [area under the curve (AUC) mean = 0.91 (0.81 to 0.99)] proved more accurate than did current fecal biomarker calprotectin [AUC mean = 0.80 (0.71 to 0.88); P = .002].

The authors acknowledged additional evidence that will be needed before these results can be translated to clinical practice, including supporting their described microbial pathways with metatranscriptomics and metabolomics data as well as functional experiments. They also observed that their predictive model will need to be validated through replication of their findings in patients with other gastrointestinal disorders or prediagnostic groups. They noted that their analysis benefited from being able to correct for confounding factors such as medication use, which is “essential for identifying disease-associated microbial features and avoiding false-positive associations due to changes in GI acidity or bowel mobility.”

One author reported receiving speaker fees from AbbVie and was a shareholder of the health care IT company Aceso BV and of Floris Medical Holding BV. Another author declared unrestricted research grants from AbbVie, Takeda, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals, is on the advisory boards for Mundipharma and Pharmacosmos, and has received speaker fees from Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. A third author declared consulting work for Takeda. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vich Vila A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap8914.

Thanks to shotgun metagenomic sequencing of gut microbiota, physicians are on track to more easily distinguish inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), according to an analysis of stool samples from patients with the two common gastrointestinal diseases.

“The integration of these datasets allowed us to pinpoint key species as targets for functional studies in IBD and IBS and to connect knowledge of the etiology and pathogenesis of IBD and IBS with the gut microbiome to provide potential new targets for treatment,” wrote Arnau Vich Vila, of the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, and his coauthors. The report is in Science Translational Medicine.

Stool samples from 1,792 participants were analyzed: 355 from patients with IBD, 412 from patients with IBS, and 1,025 from the control group. The researchers found 24 bacterial taxa associated with both IBD and IBS and specific species that accompanied specific diseases, such as an abundance of Bacteroides in patients with IBD and Firmicutes in patients with IBS. In addition, their predictive model to distinguish IBD from IBS via gut microbial composition data [area under the curve (AUC) mean = 0.91 (0.81 to 0.99)] proved more accurate than did current fecal biomarker calprotectin [AUC mean = 0.80 (0.71 to 0.88); P = .002].

The authors acknowledged additional evidence that will be needed before these results can be translated to clinical practice, including supporting their described microbial pathways with metatranscriptomics and metabolomics data as well as functional experiments. They also observed that their predictive model will need to be validated through replication of their findings in patients with other gastrointestinal disorders or prediagnostic groups. They noted that their analysis benefited from being able to correct for confounding factors such as medication use, which is “essential for identifying disease-associated microbial features and avoiding false-positive associations due to changes in GI acidity or bowel mobility.”

One author reported receiving speaker fees from AbbVie and was a shareholder of the health care IT company Aceso BV and of Floris Medical Holding BV. Another author declared unrestricted research grants from AbbVie, Takeda, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals, is on the advisory boards for Mundipharma and Pharmacosmos, and has received speaker fees from Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. A third author declared consulting work for Takeda. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vich Vila A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap8914.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data revealed key differences in gut microbiome composition between patients with inflammatory bowel disease and patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Major finding: A predictive model to distinguish IBD from IBS based on gut microbial composition data [area under the curve (AUC) mean = 0.91 (0.81-0.99)] proved more accurate than did fecal biomarker calprotectin [AUC mean = 0.80 (0.71-0.88); P = .002].

Study details: A case-control analysis using shotgun metagenomic sequencing of stool samples from 1,792 individuals with IBD, IBS, or neither.

Disclosures: One author reported receiving speaker fees from AbbVie and was a shareholder of the health care IT company Aceso BV and of Floris Medical Holding BV. Another author declared unrestricted research grants from AbbVie, Takeda, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals, is on the advisory boards for Mundipharma and Pharmacosmos, and has received speaker fees from Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. A third author declared consulting work for Takeda. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vich Vila A et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap8914.

Pregnant women commonly refuse the influenza vaccine

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Although almost all ob.gyns. recommend the influenza and Tdap vaccines for pregnant women, both commonly are refused.

Major finding: A total of 62% of ob.gyns. reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine; 32% reported this for Tdap vaccine.

Study details: An email and mail survey sent to a national network of ob.gyns. between March and June 2016.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Antipsychotic use in young people tied to 80% increased risk of death

Children and young people who received antipsychotic doses higher than 50-mg chlorpromazine equivalents had an 80% increased risk of death at follow-up, compared with a control group, according to a study of young Medicaid enrollees who recently had begun medication.

“The study findings seem to reinforce existing guidelines for improving the outcomes of antipsychotic therapy in children and youths,” wrote lead author Wayne A. Ray, PhD, of the department of health policy at the Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors. Those guidelines include using “psychosocial interventions when possible, cardiometabolic assessment before treatment and monitoring after treatment, and limiting therapy to the lowest dose and shortest duration possible,” they wrote.

The study, published online in JAMA Psychiatry, analyzed children and young adults from Tennessee, aged 5-24 years, who were new medication users, and had been enrolled in Medicaid between 1999 and 2014.

They were split into three groups: a control group (189,361) with users primarily taking attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications and antidepressants; a group (28,377) with users who received antipsychotic doses of 50 mg or less chlorpromazine equivalents; and a group (30,120) with users who received doses higher than 50-mg chlorpromazine equivalents.

At follow-up, the incidence of death in the higher-dose group was 146.2 per 100,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 107.3-199.4 per 100,000 person-years), compared with 49.5 in the lower-dose group (95% CI, 24.8-99.0) and 54.5 in the control group (95% CI, 42.9-69.2). This difference was attributed to unexpected deaths, which accounted for 52.5% of deaths in the higher-dose group. No increased risk of death was noted for injuries or suicides. “The elevated risk persisted for unexpected deaths not due to overdose, with a 4.3-fold increased risk of death from cardiovascular or metabolic causes,” Dr. Ray and his coauthors wrote.

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including a relatively small number of deaths during follow-up and subsequent statistical adjustment during analysis. They also recognized that their data did not factor in important characteristics such as body mass index and family history, and that a “single-state Medicaid cohort may limit the study’s generalizability.”

Nonetheless, they emphasized Medicaid’s relevance as coverage provider for an estimated 39% of U.S. children, along with noting that

“Further studies are needed that compare antipsychotic users and controls within more narrow comorbidity ranges or in analyses that include richer clinical data,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3421.

This study by Wayne A. Ray, PhD, and his colleagues addresses the risks of antipsychotic use in childhood while highlighting the contradictions in how psychiatrically ill children are treated and medicated, according to Barbara Geller, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

Before commenting on the study itself, Dr. Geller noted that child psychiatry is not a subspecialty that deals with “little patients and little problems,” despite that lingering perception among some. “Fifty percent of psychiatry disorders begin by age 14 years,” she wrote, “and childhood age at onset is a risk factor for a more severe longitudinal course in mood and other disorders.”

In addition, though it seems instinctually that antipsychotic medications would have lesser side effects on healthy children, that is not always the case. “The opposite is true for certain metabolic and endocrine effects,” she explained, “such as relatively greater weight gain and prolactin level elevation than adults and the onset of type 2 diabetes within the first year of treatment.”

When it came to the study, Dr. Geller posed questions about the findings, including whether an increase in unexpected deaths among the higher-dose group could be attributed to suicide. She also recommended that future investigations “examine outcomes within child, adolescent, and young adult age subgroups, as opposed to combining all youth 6 to 24 years old.”

That said, this research does probe depths that require continued exploration. “Results in the study by Ray et al. heighten the already increased caution about prescribing antipsychotics to children and adolescents,” she wrote, “and emphasize the need to consider situational triggers of psychopathology to avoid medicating the environment.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3409). No conflicts of interest were reported.

This study by Wayne A. Ray, PhD, and his colleagues addresses the risks of antipsychotic use in childhood while highlighting the contradictions in how psychiatrically ill children are treated and medicated, according to Barbara Geller, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

Before commenting on the study itself, Dr. Geller noted that child psychiatry is not a subspecialty that deals with “little patients and little problems,” despite that lingering perception among some. “Fifty percent of psychiatry disorders begin by age 14 years,” she wrote, “and childhood age at onset is a risk factor for a more severe longitudinal course in mood and other disorders.”

In addition, though it seems instinctually that antipsychotic medications would have lesser side effects on healthy children, that is not always the case. “The opposite is true for certain metabolic and endocrine effects,” she explained, “such as relatively greater weight gain and prolactin level elevation than adults and the onset of type 2 diabetes within the first year of treatment.”

When it came to the study, Dr. Geller posed questions about the findings, including whether an increase in unexpected deaths among the higher-dose group could be attributed to suicide. She also recommended that future investigations “examine outcomes within child, adolescent, and young adult age subgroups, as opposed to combining all youth 6 to 24 years old.”

That said, this research does probe depths that require continued exploration. “Results in the study by Ray et al. heighten the already increased caution about prescribing antipsychotics to children and adolescents,” she wrote, “and emphasize the need to consider situational triggers of psychopathology to avoid medicating the environment.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3409). No conflicts of interest were reported.

This study by Wayne A. Ray, PhD, and his colleagues addresses the risks of antipsychotic use in childhood while highlighting the contradictions in how psychiatrically ill children are treated and medicated, according to Barbara Geller, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

Before commenting on the study itself, Dr. Geller noted that child psychiatry is not a subspecialty that deals with “little patients and little problems,” despite that lingering perception among some. “Fifty percent of psychiatry disorders begin by age 14 years,” she wrote, “and childhood age at onset is a risk factor for a more severe longitudinal course in mood and other disorders.”

In addition, though it seems instinctually that antipsychotic medications would have lesser side effects on healthy children, that is not always the case. “The opposite is true for certain metabolic and endocrine effects,” she explained, “such as relatively greater weight gain and prolactin level elevation than adults and the onset of type 2 diabetes within the first year of treatment.”

When it came to the study, Dr. Geller posed questions about the findings, including whether an increase in unexpected deaths among the higher-dose group could be attributed to suicide. She also recommended that future investigations “examine outcomes within child, adolescent, and young adult age subgroups, as opposed to combining all youth 6 to 24 years old.”

That said, this research does probe depths that require continued exploration. “Results in the study by Ray et al. heighten the already increased caution about prescribing antipsychotics to children and adolescents,” she wrote, “and emphasize the need to consider situational triggers of psychopathology to avoid medicating the environment.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3409). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Children and young people who received antipsychotic doses higher than 50-mg chlorpromazine equivalents had an 80% increased risk of death at follow-up, compared with a control group, according to a study of young Medicaid enrollees who recently had begun medication.

“The study findings seem to reinforce existing guidelines for improving the outcomes of antipsychotic therapy in children and youths,” wrote lead author Wayne A. Ray, PhD, of the department of health policy at the Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors. Those guidelines include using “psychosocial interventions when possible, cardiometabolic assessment before treatment and monitoring after treatment, and limiting therapy to the lowest dose and shortest duration possible,” they wrote.

The study, published online in JAMA Psychiatry, analyzed children and young adults from Tennessee, aged 5-24 years, who were new medication users, and had been enrolled in Medicaid between 1999 and 2014.

They were split into three groups: a control group (189,361) with users primarily taking attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications and antidepressants; a group (28,377) with users who received antipsychotic doses of 50 mg or less chlorpromazine equivalents; and a group (30,120) with users who received doses higher than 50-mg chlorpromazine equivalents.

At follow-up, the incidence of death in the higher-dose group was 146.2 per 100,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 107.3-199.4 per 100,000 person-years), compared with 49.5 in the lower-dose group (95% CI, 24.8-99.0) and 54.5 in the control group (95% CI, 42.9-69.2). This difference was attributed to unexpected deaths, which accounted for 52.5% of deaths in the higher-dose group. No increased risk of death was noted for injuries or suicides. “The elevated risk persisted for unexpected deaths not due to overdose, with a 4.3-fold increased risk of death from cardiovascular or metabolic causes,” Dr. Ray and his coauthors wrote.

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including a relatively small number of deaths during follow-up and subsequent statistical adjustment during analysis. They also recognized that their data did not factor in important characteristics such as body mass index and family history, and that a “single-state Medicaid cohort may limit the study’s generalizability.”

Nonetheless, they emphasized Medicaid’s relevance as coverage provider for an estimated 39% of U.S. children, along with noting that

“Further studies are needed that compare antipsychotic users and controls within more narrow comorbidity ranges or in analyses that include richer clinical data,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3421.

Children and young people who received antipsychotic doses higher than 50-mg chlorpromazine equivalents had an 80% increased risk of death at follow-up, compared with a control group, according to a study of young Medicaid enrollees who recently had begun medication.

“The study findings seem to reinforce existing guidelines for improving the outcomes of antipsychotic therapy in children and youths,” wrote lead author Wayne A. Ray, PhD, of the department of health policy at the Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors. Those guidelines include using “psychosocial interventions when possible, cardiometabolic assessment before treatment and monitoring after treatment, and limiting therapy to the lowest dose and shortest duration possible,” they wrote.

The study, published online in JAMA Psychiatry, analyzed children and young adults from Tennessee, aged 5-24 years, who were new medication users, and had been enrolled in Medicaid between 1999 and 2014.

They were split into three groups: a control group (189,361) with users primarily taking attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications and antidepressants; a group (28,377) with users who received antipsychotic doses of 50 mg or less chlorpromazine equivalents; and a group (30,120) with users who received doses higher than 50-mg chlorpromazine equivalents.

At follow-up, the incidence of death in the higher-dose group was 146.2 per 100,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 107.3-199.4 per 100,000 person-years), compared with 49.5 in the lower-dose group (95% CI, 24.8-99.0) and 54.5 in the control group (95% CI, 42.9-69.2). This difference was attributed to unexpected deaths, which accounted for 52.5% of deaths in the higher-dose group. No increased risk of death was noted for injuries or suicides. “The elevated risk persisted for unexpected deaths not due to overdose, with a 4.3-fold increased risk of death from cardiovascular or metabolic causes,” Dr. Ray and his coauthors wrote.

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including a relatively small number of deaths during follow-up and subsequent statistical adjustment during analysis. They also recognized that their data did not factor in important characteristics such as body mass index and family history, and that a “single-state Medicaid cohort may limit the study’s generalizability.”

Nonetheless, they emphasized Medicaid’s relevance as coverage provider for an estimated 39% of U.S. children, along with noting that

“Further studies are needed that compare antipsychotic users and controls within more narrow comorbidity ranges or in analyses that include richer clinical data,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3421.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Children and youths who received higher doses of antipsychotic medication had an 80% increased risk of death, compared with those in a control group.

Major finding: The incidence of unexpected death was 76.8 per 100,000 person-years in the higher-dose group, compared with 17.9 per 100,000 person-years in the control group.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of Medicaid-enrolled children and young adults from Tennessee, aged 5-24 years, who were new users of antipsychotic or control medications.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Ray WA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3421.

Parental leave for residents pales in comparison to that of faculty physicians

Leave policies for residents who become new parents are uneven, oft-ignored by training boards, and provide less time off than similar policies for faculty physicians. Those were the findings of a pair of research letters published in JAMA.

Kirti Magudia, MD, of the department of radiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and her colleagues reviewed childbearing and family leave policies for 15 graduate medical education (GME)–sponsoring institutions, all of which were affiliated with the top 12 U.S. medical schools. Though all 12 schools provided paid childbearing or family leave for faculty physicians, only 8 of the 15 did so for residents (JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22)]:2372-4).

In programs that did provide leave, the average of 6.6 weeks of paid total maternity leave for residents was less than the 8.6 weeks faculty receive. Both are considerably less than proscribed by the Family and Medical Leave Act, which requires large employers to provide 12 weeks of unpaid leave, but only after 12 months of employment.

The research focused on only institutional policies for paid leave; unpaid leave and state policies may extend the average, and departments may offer leave that goes beyond specific policies, Dr. Magudia and her colleagues noted.

Changes in the residency population make now the right time for establishing consistent family leave policies, Dr. Magudia said in an interview. “We have people starting training later; we have more female trainees. And with the Match system, you’re not in control of exactly where you’re going. You may not have a support system where you end up, and a lot of the top training institutions are in high cost-of-living areas. All of those things together can make trainees especially vulnerable, and because trainees are temporary employees, changing policies to benefit them is very challenging.

“Wellness is a huge issue in medicine, and at large in society,” she said. “Making sure people have adequate parental leave goes a long way toward reducing stress levels and helping them cope with normal life transitions. We want to take steps that promote success among a diverse community of physicians; we want to retain as many people in the field as possible, and we want them to feel supported.”

Beyond asking all GME-sponsoring institutions to adopt parental leave policies, Dr. Magudia believes trainees must be better informed. “It should be clear to training program applicants what the policies are at those institutions,” she said. “That information is extremely difficult to obtain, as we’ve discovered. You can imagine that, if you are the applicant, it can be difficult to ask about those policies during the interview process because it may affect how things turn out.”

“If we can see changes like these made in the near future,” she added, “we will be in a good place.”

In the second study, Briony K. Varda, MD, of the department of urology at Boston Children’s Hospital, and her colleagues also noted the complications of balancing parental leave with training requirements from specialty boards. They compared leave policies among American Board of Medical Specialty member organizations and found that less than half specifically mentioned parental leave for resident physicians (JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22]:2374-7).

Dr. Varda and her colleagues reviewed the websites of 24 ABMS boards to determine their leave policies; 22 had policies but only 11 cited parental leave as an option for residents. Twenty boards have time-based training requirements and allow for a median of 6 weeks leave for any reason; none of the boards had a specific policy for parental leave. In addition, only eight boards had “explicit and clear clarifying language” that would allow program directors to seek exemptions for their residents.

Though limitations like not detecting all available policies – and a subjective evaluation of the policies that were reviewed – could have impacted their study, the coauthors reiterated that the median of 6 weeks leave is less than the average leave for faculty physicians. They also emphasized the detriments associated with inadequate parental leave, including delayed childbearing, use of assisted reproduction technology, and difficulty breastfeeding.

Dr. Varda underlined the issues that arise for program directors, who “must weigh potentially conflicting factors such as adhering to board and institutional policies, maintaining adequate clinical service coverage, considering precedent within the program, and ensuring that resident physicians are well trained.” To balance the needs of all involved “novel approaches such as use of competency-based rather than time-based training milestones” to determine certification eligibility and, in return, lessen the stresses for new-parent residents, she noted.

The researchers disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Magudia K et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22)]:2372-4; Varda B et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22]:2374-7.

Recent data by Magudia et al. have highlighted the fact that family leave policies supporting parents during medical training are widely inconsistent and in many instances do not exist. Where trainee policies do exist, benefits are routinely less robust than those of permanent faculty who receive on average 30% more paid leave time. Stratifying physician wellness needs by training status seems to be a misplaced approach.

It is not only the medical field which sees inconsistencies in the way family leave is allocated for different types of jobs. Millions of Americans receive no time off after birth or adoption, at a time when corporate America offers elite benefits for child care. In medicine, however, there is an expectation that paid family leave should be the norm, perhaps because of our mission to improve the quality of health care.

Of course, there are valid distinctions between faculty and trainees: faculty are more permanent, are more professionally differentiated and accomplished than trainees, have greater responsibilities, and are recruited for their expertise. Arguably, faculty deserve better compensation than trainees.

But the importance of parental leave transcends the routine benefits arguments. There is something more universal about how we value parenting. Parental leave policies benefit the health of parent and child, increase career satisfaction, and improve retention. The process of birth or adoption, ensuing fatigue, family bonding needs, and life-restructuring will challenge all parents regardless of career status.

Awareness of the inadequacies of parental leave policies is the first step in remedying the disparities in support for our trainees. Establishing an equal and adequate family leave policy for physicians at any stage is consistent with the goal of success and well-being for us all.

Laurel Fisher, MD, AGAF, professor of clinical internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She reports no conflicts of interest.

Recent data by Magudia et al. have highlighted the fact that family leave policies supporting parents during medical training are widely inconsistent and in many instances do not exist. Where trainee policies do exist, benefits are routinely less robust than those of permanent faculty who receive on average 30% more paid leave time. Stratifying physician wellness needs by training status seems to be a misplaced approach.

It is not only the medical field which sees inconsistencies in the way family leave is allocated for different types of jobs. Millions of Americans receive no time off after birth or adoption, at a time when corporate America offers elite benefits for child care. In medicine, however, there is an expectation that paid family leave should be the norm, perhaps because of our mission to improve the quality of health care.

Of course, there are valid distinctions between faculty and trainees: faculty are more permanent, are more professionally differentiated and accomplished than trainees, have greater responsibilities, and are recruited for their expertise. Arguably, faculty deserve better compensation than trainees.

But the importance of parental leave transcends the routine benefits arguments. There is something more universal about how we value parenting. Parental leave policies benefit the health of parent and child, increase career satisfaction, and improve retention. The process of birth or adoption, ensuing fatigue, family bonding needs, and life-restructuring will challenge all parents regardless of career status.

Awareness of the inadequacies of parental leave policies is the first step in remedying the disparities in support for our trainees. Establishing an equal and adequate family leave policy for physicians at any stage is consistent with the goal of success and well-being for us all.

Laurel Fisher, MD, AGAF, professor of clinical internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She reports no conflicts of interest.

Recent data by Magudia et al. have highlighted the fact that family leave policies supporting parents during medical training are widely inconsistent and in many instances do not exist. Where trainee policies do exist, benefits are routinely less robust than those of permanent faculty who receive on average 30% more paid leave time. Stratifying physician wellness needs by training status seems to be a misplaced approach.

It is not only the medical field which sees inconsistencies in the way family leave is allocated for different types of jobs. Millions of Americans receive no time off after birth or adoption, at a time when corporate America offers elite benefits for child care. In medicine, however, there is an expectation that paid family leave should be the norm, perhaps because of our mission to improve the quality of health care.

Of course, there are valid distinctions between faculty and trainees: faculty are more permanent, are more professionally differentiated and accomplished than trainees, have greater responsibilities, and are recruited for their expertise. Arguably, faculty deserve better compensation than trainees.

But the importance of parental leave transcends the routine benefits arguments. There is something more universal about how we value parenting. Parental leave policies benefit the health of parent and child, increase career satisfaction, and improve retention. The process of birth or adoption, ensuing fatigue, family bonding needs, and life-restructuring will challenge all parents regardless of career status.

Awareness of the inadequacies of parental leave policies is the first step in remedying the disparities in support for our trainees. Establishing an equal and adequate family leave policy for physicians at any stage is consistent with the goal of success and well-being for us all.

Laurel Fisher, MD, AGAF, professor of clinical internal medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She reports no conflicts of interest.

Leave policies for residents who become new parents are uneven, oft-ignored by training boards, and provide less time off than similar policies for faculty physicians. Those were the findings of a pair of research letters published in JAMA.

Kirti Magudia, MD, of the department of radiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and her colleagues reviewed childbearing and family leave policies for 15 graduate medical education (GME)–sponsoring institutions, all of which were affiliated with the top 12 U.S. medical schools. Though all 12 schools provided paid childbearing or family leave for faculty physicians, only 8 of the 15 did so for residents (JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22)]:2372-4).

In programs that did provide leave, the average of 6.6 weeks of paid total maternity leave for residents was less than the 8.6 weeks faculty receive. Both are considerably less than proscribed by the Family and Medical Leave Act, which requires large employers to provide 12 weeks of unpaid leave, but only after 12 months of employment.

The research focused on only institutional policies for paid leave; unpaid leave and state policies may extend the average, and departments may offer leave that goes beyond specific policies, Dr. Magudia and her colleagues noted.

Changes in the residency population make now the right time for establishing consistent family leave policies, Dr. Magudia said in an interview. “We have people starting training later; we have more female trainees. And with the Match system, you’re not in control of exactly where you’re going. You may not have a support system where you end up, and a lot of the top training institutions are in high cost-of-living areas. All of those things together can make trainees especially vulnerable, and because trainees are temporary employees, changing policies to benefit them is very challenging.

“Wellness is a huge issue in medicine, and at large in society,” she said. “Making sure people have adequate parental leave goes a long way toward reducing stress levels and helping them cope with normal life transitions. We want to take steps that promote success among a diverse community of physicians; we want to retain as many people in the field as possible, and we want them to feel supported.”

Beyond asking all GME-sponsoring institutions to adopt parental leave policies, Dr. Magudia believes trainees must be better informed. “It should be clear to training program applicants what the policies are at those institutions,” she said. “That information is extremely difficult to obtain, as we’ve discovered. You can imagine that, if you are the applicant, it can be difficult to ask about those policies during the interview process because it may affect how things turn out.”

“If we can see changes like these made in the near future,” she added, “we will be in a good place.”

In the second study, Briony K. Varda, MD, of the department of urology at Boston Children’s Hospital, and her colleagues also noted the complications of balancing parental leave with training requirements from specialty boards. They compared leave policies among American Board of Medical Specialty member organizations and found that less than half specifically mentioned parental leave for resident physicians (JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22]:2374-7).

Dr. Varda and her colleagues reviewed the websites of 24 ABMS boards to determine their leave policies; 22 had policies but only 11 cited parental leave as an option for residents. Twenty boards have time-based training requirements and allow for a median of 6 weeks leave for any reason; none of the boards had a specific policy for parental leave. In addition, only eight boards had “explicit and clear clarifying language” that would allow program directors to seek exemptions for their residents.

Though limitations like not detecting all available policies – and a subjective evaluation of the policies that were reviewed – could have impacted their study, the coauthors reiterated that the median of 6 weeks leave is less than the average leave for faculty physicians. They also emphasized the detriments associated with inadequate parental leave, including delayed childbearing, use of assisted reproduction technology, and difficulty breastfeeding.

Dr. Varda underlined the issues that arise for program directors, who “must weigh potentially conflicting factors such as adhering to board and institutional policies, maintaining adequate clinical service coverage, considering precedent within the program, and ensuring that resident physicians are well trained.” To balance the needs of all involved “novel approaches such as use of competency-based rather than time-based training milestones” to determine certification eligibility and, in return, lessen the stresses for new-parent residents, she noted.

The researchers disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Magudia K et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22)]:2372-4; Varda B et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22]:2374-7.

Leave policies for residents who become new parents are uneven, oft-ignored by training boards, and provide less time off than similar policies for faculty physicians. Those were the findings of a pair of research letters published in JAMA.

Kirti Magudia, MD, of the department of radiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and her colleagues reviewed childbearing and family leave policies for 15 graduate medical education (GME)–sponsoring institutions, all of which were affiliated with the top 12 U.S. medical schools. Though all 12 schools provided paid childbearing or family leave for faculty physicians, only 8 of the 15 did so for residents (JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22)]:2372-4).

In programs that did provide leave, the average of 6.6 weeks of paid total maternity leave for residents was less than the 8.6 weeks faculty receive. Both are considerably less than proscribed by the Family and Medical Leave Act, which requires large employers to provide 12 weeks of unpaid leave, but only after 12 months of employment.

The research focused on only institutional policies for paid leave; unpaid leave and state policies may extend the average, and departments may offer leave that goes beyond specific policies, Dr. Magudia and her colleagues noted.

Changes in the residency population make now the right time for establishing consistent family leave policies, Dr. Magudia said in an interview. “We have people starting training later; we have more female trainees. And with the Match system, you’re not in control of exactly where you’re going. You may not have a support system where you end up, and a lot of the top training institutions are in high cost-of-living areas. All of those things together can make trainees especially vulnerable, and because trainees are temporary employees, changing policies to benefit them is very challenging.

“Wellness is a huge issue in medicine, and at large in society,” she said. “Making sure people have adequate parental leave goes a long way toward reducing stress levels and helping them cope with normal life transitions. We want to take steps that promote success among a diverse community of physicians; we want to retain as many people in the field as possible, and we want them to feel supported.”

Beyond asking all GME-sponsoring institutions to adopt parental leave policies, Dr. Magudia believes trainees must be better informed. “It should be clear to training program applicants what the policies are at those institutions,” she said. “That information is extremely difficult to obtain, as we’ve discovered. You can imagine that, if you are the applicant, it can be difficult to ask about those policies during the interview process because it may affect how things turn out.”

“If we can see changes like these made in the near future,” she added, “we will be in a good place.”

In the second study, Briony K. Varda, MD, of the department of urology at Boston Children’s Hospital, and her colleagues also noted the complications of balancing parental leave with training requirements from specialty boards. They compared leave policies among American Board of Medical Specialty member organizations and found that less than half specifically mentioned parental leave for resident physicians (JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22]:2374-7).

Dr. Varda and her colleagues reviewed the websites of 24 ABMS boards to determine their leave policies; 22 had policies but only 11 cited parental leave as an option for residents. Twenty boards have time-based training requirements and allow for a median of 6 weeks leave for any reason; none of the boards had a specific policy for parental leave. In addition, only eight boards had “explicit and clear clarifying language” that would allow program directors to seek exemptions for their residents.

Though limitations like not detecting all available policies – and a subjective evaluation of the policies that were reviewed – could have impacted their study, the coauthors reiterated that the median of 6 weeks leave is less than the average leave for faculty physicians. They also emphasized the detriments associated with inadequate parental leave, including delayed childbearing, use of assisted reproduction technology, and difficulty breastfeeding.

Dr. Varda underlined the issues that arise for program directors, who “must weigh potentially conflicting factors such as adhering to board and institutional policies, maintaining adequate clinical service coverage, considering precedent within the program, and ensuring that resident physicians are well trained.” To balance the needs of all involved “novel approaches such as use of competency-based rather than time-based training milestones” to determine certification eligibility and, in return, lessen the stresses for new-parent residents, she noted.

The researchers disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Magudia K et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22)]:2372-4; Varda B et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320[22]:2374-7.

FROM JAMA

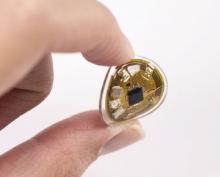

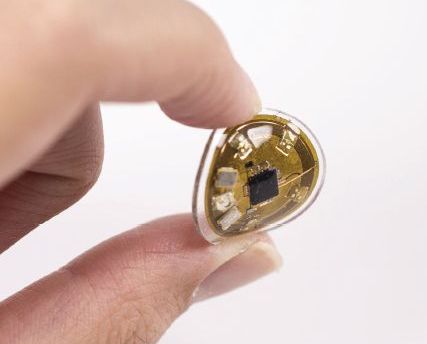

New devices can monitor personalized light exposure for radiation

, according to three studies of the millimeter-scale near-field communication (mm-NFC) devices.

“These studies highlight the differences between mm-NFC dosimeters and commercial devices in real-world, practical scenarios,” wrote lead author Seung Yun Heo of the department of biomedical engineering at the Center for Bio-Integrated Electronics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her coauthors. “The former operate in continuous, uninterrupted modes, whereas the latter capture instantaneous values of intensity at preprogrammed intervals,”they noted. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Separate studies to assess the performance of these “flexible” dosimeters took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and St. Petersburg, Fla. The Florida study included 13 healthy participants who wore skin-mounted mm-NFC ultraviolet A (UVA) dosimeters on the right back hand, left back hand, left inner arm, and left outer arm, plus a commercial dosimeter on the right wrist. The volunteers walked a 6.44-km path three times: a morning and subsequent afternoon stroll, plus an evening walk 4 days later. Four devices failed during the afternoon exercise, but otherwise, participants received data on their smartphones via the dosimeters at 30-minute intervals.

The Brazilian study was made up of nine healthy participants who wore mm-NFC UVA dosimeters on the thumbnail or the middle fingernail; commercial dosimeters were worn on the wrist of the ipsilateral side. These volunteers engaged in rooftop recreational activities that corresponded to solar zenith angles, along with showering and swimming with the use of soap and skin creams. All sensors remained functional over the 4 days of testing, and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail. Accumulated doses ranged widely, “as expected on the basis of the differences in behaviors,” the authors wrote. These observations imply highly variable UV-associated risks between participants, due not only to differences in Fitzpatrick skin types but also to individual behavior patterns,” they added.

The third study of mm-NFC blue light dosimeters comprised three newborns in an Urbana, Ill., neonatal ICU undergoing blue light phototherapy treatments. Nurses mounted dosimeters on the patients’ chests before phototherapy; an antenna underneath the incubator mattress transmitted continuous wireless measurements of blue intensity and dosage at 20-minute intervals for 20 hours.

The authors acknowledged that these devices and their designs have limitations, including a small detection area as compared to the surface area of a human body. The study’s results “represent localized measurements of exposure, whereas the sun irradiance profile across the body surface is not uniform and varies by position of the sun in the sky over the course of a day.” They recommended that future research could “create anatomic specific risk assessment of UV exposure” via multinodal sensing with UVA/UVB dosimeters on several parts of the body.

The Brazilian UV study was sponsored by La Roche Posay and L’Oreal California Research Center. Research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Five of the authors reported commercial interests in the technology. Another author reported paid consultation for Aclaris Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Heo SY et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1643.

, according to three studies of the millimeter-scale near-field communication (mm-NFC) devices.

“These studies highlight the differences between mm-NFC dosimeters and commercial devices in real-world, practical scenarios,” wrote lead author Seung Yun Heo of the department of biomedical engineering at the Center for Bio-Integrated Electronics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her coauthors. “The former operate in continuous, uninterrupted modes, whereas the latter capture instantaneous values of intensity at preprogrammed intervals,”they noted. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Separate studies to assess the performance of these “flexible” dosimeters took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and St. Petersburg, Fla. The Florida study included 13 healthy participants who wore skin-mounted mm-NFC ultraviolet A (UVA) dosimeters on the right back hand, left back hand, left inner arm, and left outer arm, plus a commercial dosimeter on the right wrist. The volunteers walked a 6.44-km path three times: a morning and subsequent afternoon stroll, plus an evening walk 4 days later. Four devices failed during the afternoon exercise, but otherwise, participants received data on their smartphones via the dosimeters at 30-minute intervals.

The Brazilian study was made up of nine healthy participants who wore mm-NFC UVA dosimeters on the thumbnail or the middle fingernail; commercial dosimeters were worn on the wrist of the ipsilateral side. These volunteers engaged in rooftop recreational activities that corresponded to solar zenith angles, along with showering and swimming with the use of soap and skin creams. All sensors remained functional over the 4 days of testing, and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail. Accumulated doses ranged widely, “as expected on the basis of the differences in behaviors,” the authors wrote. These observations imply highly variable UV-associated risks between participants, due not only to differences in Fitzpatrick skin types but also to individual behavior patterns,” they added.

The third study of mm-NFC blue light dosimeters comprised three newborns in an Urbana, Ill., neonatal ICU undergoing blue light phototherapy treatments. Nurses mounted dosimeters on the patients’ chests before phototherapy; an antenna underneath the incubator mattress transmitted continuous wireless measurements of blue intensity and dosage at 20-minute intervals for 20 hours.

The authors acknowledged that these devices and their designs have limitations, including a small detection area as compared to the surface area of a human body. The study’s results “represent localized measurements of exposure, whereas the sun irradiance profile across the body surface is not uniform and varies by position of the sun in the sky over the course of a day.” They recommended that future research could “create anatomic specific risk assessment of UV exposure” via multinodal sensing with UVA/UVB dosimeters on several parts of the body.

The Brazilian UV study was sponsored by La Roche Posay and L’Oreal California Research Center. Research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Five of the authors reported commercial interests in the technology. Another author reported paid consultation for Aclaris Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Heo SY et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1643.

, according to three studies of the millimeter-scale near-field communication (mm-NFC) devices.

“These studies highlight the differences between mm-NFC dosimeters and commercial devices in real-world, practical scenarios,” wrote lead author Seung Yun Heo of the department of biomedical engineering at the Center for Bio-Integrated Electronics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her coauthors. “The former operate in continuous, uninterrupted modes, whereas the latter capture instantaneous values of intensity at preprogrammed intervals,”they noted. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Separate studies to assess the performance of these “flexible” dosimeters took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and St. Petersburg, Fla. The Florida study included 13 healthy participants who wore skin-mounted mm-NFC ultraviolet A (UVA) dosimeters on the right back hand, left back hand, left inner arm, and left outer arm, plus a commercial dosimeter on the right wrist. The volunteers walked a 6.44-km path three times: a morning and subsequent afternoon stroll, plus an evening walk 4 days later. Four devices failed during the afternoon exercise, but otherwise, participants received data on their smartphones via the dosimeters at 30-minute intervals.

The Brazilian study was made up of nine healthy participants who wore mm-NFC UVA dosimeters on the thumbnail or the middle fingernail; commercial dosimeters were worn on the wrist of the ipsilateral side. These volunteers engaged in rooftop recreational activities that corresponded to solar zenith angles, along with showering and swimming with the use of soap and skin creams. All sensors remained functional over the 4 days of testing, and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail. Accumulated doses ranged widely, “as expected on the basis of the differences in behaviors,” the authors wrote. These observations imply highly variable UV-associated risks between participants, due not only to differences in Fitzpatrick skin types but also to individual behavior patterns,” they added.

The third study of mm-NFC blue light dosimeters comprised three newborns in an Urbana, Ill., neonatal ICU undergoing blue light phototherapy treatments. Nurses mounted dosimeters on the patients’ chests before phototherapy; an antenna underneath the incubator mattress transmitted continuous wireless measurements of blue intensity and dosage at 20-minute intervals for 20 hours.

The authors acknowledged that these devices and their designs have limitations, including a small detection area as compared to the surface area of a human body. The study’s results “represent localized measurements of exposure, whereas the sun irradiance profile across the body surface is not uniform and varies by position of the sun in the sky over the course of a day.” They recommended that future research could “create anatomic specific risk assessment of UV exposure” via multinodal sensing with UVA/UVB dosimeters on several parts of the body.

The Brazilian UV study was sponsored by La Roche Posay and L’Oreal California Research Center. Research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Five of the authors reported commercial interests in the technology. Another author reported paid consultation for Aclaris Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Heo SY et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018 Dec 5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau1643.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Newly designed flexible dosimeters can track personalized light exposure and electromagnetic radiation via wireless sensor technology.

Major finding: In one study, during four days of testing – including recreational activities, showering, and swimming—all mm-NFC UVA dosimeter sensors remained functional and 14 of 20 devices remained adhered to the fingernail.