User login

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious paramyxovirus that has neared elimination in the United States since 2000 due to widespread adoption of the measles vaccine; however, measles recently has made a comeback, with outbreaks reported in more than 60 countries. In the United States, vaccine hesitancy coupled with decreasing vaccination rates, international travel to endemic areas, and decreased funding and resources for monitoring and immunization programs likely led to a re-emergence of measles cases.1,2 The resurgence of measles is troubling given its infectiousness and potential severity in at-risk populations. Since measles has a basic reproduction number of 12 to 18 (ie, 1 infected individual will on average infect 12 to 18 others3), it has the capacity to spread quickly. This is why, prior to the development of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, it was responsible for millions of deaths across the globe.

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, both physicians and the public generally were aware of the signs and symptoms of measles due to its prevalence; however, since there have been so few cases in recent decades, images and descriptions of patients presenting with measles can be found only in textbooks, and many physicians are ill-prepared to diagnose the disease.4 In response to the recent surge in measles cases, dermatologists—who often are among the first medical professionals to encounter febrile patients with rashes—must be prepared to bridge this divide. Herein, we review the clinical signs, diagnostic approach, operational precautions, and public health responsibilities that dermatologists must relearn amid the current measles outbreak.

Background

Measles is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets and may remain airborne for up to 2 hours.5 It also can be transmitted through direct contact with secretions such as mucus. Indirect transmission via fomites, while certainly plausible, is thought to be the least effective mechanism of transmission.6 Following exposure, the incubation period ranges from 7 to 21 days, during which the virus replicates asymptomatically before causing clinical disease.7 Herd immunity for measles requires 93% immunity in the population; public health agencies typically target greater than 95% immunity.8 Humans are the only reservoir for the measles virus, making eradication possible.

The road to eradication began with the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 and subsequent development of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971. As MMR is a live vaccine, 2 doses confer approximately 97% protection.9 The first dose is given at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose is given at 4 to 6 years of age. Immunity is considered lifelong, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization do not recommend routine measles boosters for individuals who have completed the primary 2-dose series.10,11

Widespread vaccination led to a dramatic reduction in incidence, with many countries eliminating measles infections.7 The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, with confirmed cases between 2000 and 2020 ranging from 37 to 1282.12 Vaccination progress stalled in the late 1990s due to vaccine hesitancy resulting from (subsequently debunked) reports of an association between the MMR vaccine and autism.13 Despite efforts to correct this misinformation, many patients continue to espouse these concerns.

Recognizing Measles: Clinical Presentation

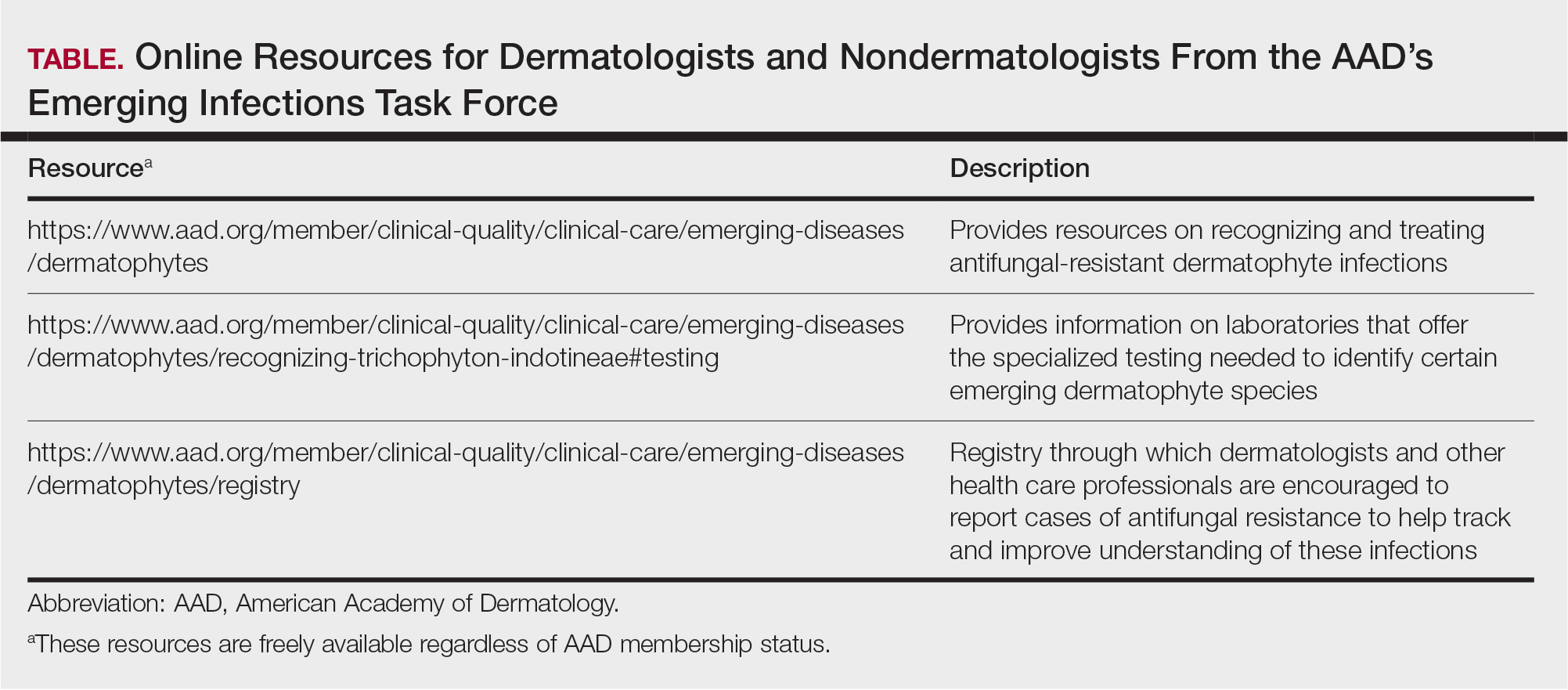

Measles, which most often manifests in childhood but also can occur in adults, follows a distinctive clinical course. The prodromal phase is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza (nasal congestion), and conjunctivitis— conjunctivitis—the 3 “Cs” that serve as early warning signs of the disease. Patients may develop small white macules on the buccal mucosa known as Koplik spots (phonetically the fourth “C”), which appear just before the rash. Three to 5 days after the onset of systemic symptoms, patients will develop a classic morbilliform exanthem. In some cases, the exanthem manifests on the head and neck (Figure 1)—first behind the ears and along the hairline, then spreading caudally to the trunk and extremities. The lesions may become confluent, with patients presenting with diffuse erythema. The exanthem fades over several days to weeks, often accompanied by superficial desquamation.14

Given the nonspecificity of the early symptoms of measles, a high index of suspicion is needed for patients presenting with a febrile illness and a morbilliform eruption (Figure 2). Consideration of MMR vaccination status, exposure history, and local outbreak patterns can help guide risk stratification and the need for testing. Immunocompromised individuals, including those receiving immunosuppressive therapies for dermatologic conditions, may present atypically, lacking the prototypical exanthem or displaying milder signs and further complicating the diagnosis.15 The differential diagnosis for measles includes a drug reaction or other viral exanthem, and a detailed history may help elucidate the culprit.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of measles relies on both molecular and serologic testing. Nasopharyngeal swabs for measles polymerase chain reaction testing are obtained using synthetic (noncotton) swabs placed in a viral transport medium. Serum samples also should be collected for measles IgM and IgG antibody testing. Importantly, measles is a reportable illness, and testing may be coordinated with local departments of health.

Determining a patient’s immune status may be important for certain populations. Patients with documented 2-dose MMR vaccination, positive measles IgG serology, or a prior confirmed measles infection are considered immune. While a positive measles IgG indicates immunity, a negative result in an exposed patient should prompt consideration of postexposure prophylaxis with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Many patients, specifically those presenting to dermatology, are taking immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications—a contraindication for vaccination with the live MMR vaccine. At the time of publication, there was a single reported case of a patient taking a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis who had acquired measles.16 While the benefits of titer assessment in patients who are starting or continuing immunomodulatory therapy are not known and currently it is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dermatologists might consider checking MMR titers and vaccinating (or referring for vaccination) nonimmune patients.17

Infection Control

Early identification of a suspected measles case is paramount. Patients in whom measles is a possibility should be isolated as quickly as possible, and the patient and accompanying caregivers should be masked. Clinical staff should don appropriate personal protective equipment, including an N95 mask. Coordination with the local department of health must occur as soon as measles is suspected.

If testing is an option in the outpatient setting, a nasopharyngeal viral swab and serologic titers can be obtained. If testing is not available on site, patients should be sent to appropriate care facilities; prenotification is critical to prevent nosocomial outbreaks. Patients should be encouraged to isolate and avoid public spaces and/or public transport for 4 days following development of an exanthem.18 Offices should develop clinical protocols for suspected measles cases with training for clinical and office staff.

Final Thoughts

As measles outbreaks become more prevalent, it is incumbent upon physicians to remind ourselves of the signs and symptoms of this largely eliminated disease so that we may pursue early detection and intervention strategies. The primary cutaneous manifestations of measles make dermatologists critical to early recognition and containment efforts. Dermatologists should prepare for the arrival of patients with measles by maintaining vigilance for the classic signs of the disease, implementing stringent isolation protocols, verifying patient immunity when appropriate, and partnering closely with public health authorities.

More broadly, efforts to contain and re-establish a paradigm for eliminating measles outbreaks must be pursued. Encouraging vaccination and developing programs to help combat misinformation surrounding vaccines are critical to this effort. In an era of vaccine hesitancy, measles is a multidisciplinary public health emergency. Dermatologists must remain ready.

- Bedford H, Elliman D. Measles rates are rising again. BMJ. 2024;384.

- Harris E. Measles outbreaks grow amid declining vaccination rates. JAMA. 2023;330:2242.

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, et al. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:E420-E428.

- Swartz MK. Measles: public and professional education. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33:367-368.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/measles/

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE, Feinstone WH. Measles. In: Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Elsevier; 2009: 551-565.

- Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490-2502.

- Maintain the vaccination coverage level of 2 doses of the MMR vaccine for children in kindergarten— IID04. Healthy People 2030 website. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/maintain-vaccination-coverage-level-2-doses-mmr-vaccine-children-kindergarten-iid-04

- Franconeri L, Antona D, Cauchemez S, et al. Two-dose measles vaccine effectiveness remains high over time: a French observational study, 2017–2019. Vaccine. 2023;41:5797-5804.

- World Health Organization. Measles. Accessed May 8, 2025. https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles vaccine recommendations. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

- Dyer C. Lancet retracts Wakefield’s MMR paper. BMJ. 2010;340.

- Alves Graber EM, Andrade FJ, Bost W, et al. An update and review of measles for emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:610-615.

- Kaplan LJ, Daum RS, Smaron M, et al. Severe measles in immunocompromised patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1237-1241.

- Takahashi E, Kurosaka D, Yoshida K, et al. Onset of modified measles after etanercept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Japanese J Clin Immunol. 2010;33:37-41.

- Worth A, Waldman RA, Dieckhaus K, et al. Art of prevention: our approach to the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in adult patients vaccinated against measles before 1968 on biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6:94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical overview of measles (rubeola). Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious paramyxovirus that has neared elimination in the United States since 2000 due to widespread adoption of the measles vaccine; however, measles recently has made a comeback, with outbreaks reported in more than 60 countries. In the United States, vaccine hesitancy coupled with decreasing vaccination rates, international travel to endemic areas, and decreased funding and resources for monitoring and immunization programs likely led to a re-emergence of measles cases.1,2 The resurgence of measles is troubling given its infectiousness and potential severity in at-risk populations. Since measles has a basic reproduction number of 12 to 18 (ie, 1 infected individual will on average infect 12 to 18 others3), it has the capacity to spread quickly. This is why, prior to the development of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, it was responsible for millions of deaths across the globe.

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, both physicians and the public generally were aware of the signs and symptoms of measles due to its prevalence; however, since there have been so few cases in recent decades, images and descriptions of patients presenting with measles can be found only in textbooks, and many physicians are ill-prepared to diagnose the disease.4 In response to the recent surge in measles cases, dermatologists—who often are among the first medical professionals to encounter febrile patients with rashes—must be prepared to bridge this divide. Herein, we review the clinical signs, diagnostic approach, operational precautions, and public health responsibilities that dermatologists must relearn amid the current measles outbreak.

Background

Measles is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets and may remain airborne for up to 2 hours.5 It also can be transmitted through direct contact with secretions such as mucus. Indirect transmission via fomites, while certainly plausible, is thought to be the least effective mechanism of transmission.6 Following exposure, the incubation period ranges from 7 to 21 days, during which the virus replicates asymptomatically before causing clinical disease.7 Herd immunity for measles requires 93% immunity in the population; public health agencies typically target greater than 95% immunity.8 Humans are the only reservoir for the measles virus, making eradication possible.

The road to eradication began with the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 and subsequent development of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971. As MMR is a live vaccine, 2 doses confer approximately 97% protection.9 The first dose is given at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose is given at 4 to 6 years of age. Immunity is considered lifelong, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization do not recommend routine measles boosters for individuals who have completed the primary 2-dose series.10,11

Widespread vaccination led to a dramatic reduction in incidence, with many countries eliminating measles infections.7 The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, with confirmed cases between 2000 and 2020 ranging from 37 to 1282.12 Vaccination progress stalled in the late 1990s due to vaccine hesitancy resulting from (subsequently debunked) reports of an association between the MMR vaccine and autism.13 Despite efforts to correct this misinformation, many patients continue to espouse these concerns.

Recognizing Measles: Clinical Presentation

Measles, which most often manifests in childhood but also can occur in adults, follows a distinctive clinical course. The prodromal phase is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza (nasal congestion), and conjunctivitis— conjunctivitis—the 3 “Cs” that serve as early warning signs of the disease. Patients may develop small white macules on the buccal mucosa known as Koplik spots (phonetically the fourth “C”), which appear just before the rash. Three to 5 days after the onset of systemic symptoms, patients will develop a classic morbilliform exanthem. In some cases, the exanthem manifests on the head and neck (Figure 1)—first behind the ears and along the hairline, then spreading caudally to the trunk and extremities. The lesions may become confluent, with patients presenting with diffuse erythema. The exanthem fades over several days to weeks, often accompanied by superficial desquamation.14

Given the nonspecificity of the early symptoms of measles, a high index of suspicion is needed for patients presenting with a febrile illness and a morbilliform eruption (Figure 2). Consideration of MMR vaccination status, exposure history, and local outbreak patterns can help guide risk stratification and the need for testing. Immunocompromised individuals, including those receiving immunosuppressive therapies for dermatologic conditions, may present atypically, lacking the prototypical exanthem or displaying milder signs and further complicating the diagnosis.15 The differential diagnosis for measles includes a drug reaction or other viral exanthem, and a detailed history may help elucidate the culprit.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of measles relies on both molecular and serologic testing. Nasopharyngeal swabs for measles polymerase chain reaction testing are obtained using synthetic (noncotton) swabs placed in a viral transport medium. Serum samples also should be collected for measles IgM and IgG antibody testing. Importantly, measles is a reportable illness, and testing may be coordinated with local departments of health.

Determining a patient’s immune status may be important for certain populations. Patients with documented 2-dose MMR vaccination, positive measles IgG serology, or a prior confirmed measles infection are considered immune. While a positive measles IgG indicates immunity, a negative result in an exposed patient should prompt consideration of postexposure prophylaxis with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Many patients, specifically those presenting to dermatology, are taking immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications—a contraindication for vaccination with the live MMR vaccine. At the time of publication, there was a single reported case of a patient taking a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis who had acquired measles.16 While the benefits of titer assessment in patients who are starting or continuing immunomodulatory therapy are not known and currently it is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dermatologists might consider checking MMR titers and vaccinating (or referring for vaccination) nonimmune patients.17

Infection Control

Early identification of a suspected measles case is paramount. Patients in whom measles is a possibility should be isolated as quickly as possible, and the patient and accompanying caregivers should be masked. Clinical staff should don appropriate personal protective equipment, including an N95 mask. Coordination with the local department of health must occur as soon as measles is suspected.

If testing is an option in the outpatient setting, a nasopharyngeal viral swab and serologic titers can be obtained. If testing is not available on site, patients should be sent to appropriate care facilities; prenotification is critical to prevent nosocomial outbreaks. Patients should be encouraged to isolate and avoid public spaces and/or public transport for 4 days following development of an exanthem.18 Offices should develop clinical protocols for suspected measles cases with training for clinical and office staff.

Final Thoughts

As measles outbreaks become more prevalent, it is incumbent upon physicians to remind ourselves of the signs and symptoms of this largely eliminated disease so that we may pursue early detection and intervention strategies. The primary cutaneous manifestations of measles make dermatologists critical to early recognition and containment efforts. Dermatologists should prepare for the arrival of patients with measles by maintaining vigilance for the classic signs of the disease, implementing stringent isolation protocols, verifying patient immunity when appropriate, and partnering closely with public health authorities.

More broadly, efforts to contain and re-establish a paradigm for eliminating measles outbreaks must be pursued. Encouraging vaccination and developing programs to help combat misinformation surrounding vaccines are critical to this effort. In an era of vaccine hesitancy, measles is a multidisciplinary public health emergency. Dermatologists must remain ready.

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious paramyxovirus that has neared elimination in the United States since 2000 due to widespread adoption of the measles vaccine; however, measles recently has made a comeback, with outbreaks reported in more than 60 countries. In the United States, vaccine hesitancy coupled with decreasing vaccination rates, international travel to endemic areas, and decreased funding and resources for monitoring and immunization programs likely led to a re-emergence of measles cases.1,2 The resurgence of measles is troubling given its infectiousness and potential severity in at-risk populations. Since measles has a basic reproduction number of 12 to 18 (ie, 1 infected individual will on average infect 12 to 18 others3), it has the capacity to spread quickly. This is why, prior to the development of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, it was responsible for millions of deaths across the globe.

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, both physicians and the public generally were aware of the signs and symptoms of measles due to its prevalence; however, since there have been so few cases in recent decades, images and descriptions of patients presenting with measles can be found only in textbooks, and many physicians are ill-prepared to diagnose the disease.4 In response to the recent surge in measles cases, dermatologists—who often are among the first medical professionals to encounter febrile patients with rashes—must be prepared to bridge this divide. Herein, we review the clinical signs, diagnostic approach, operational precautions, and public health responsibilities that dermatologists must relearn amid the current measles outbreak.

Background

Measles is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets and may remain airborne for up to 2 hours.5 It also can be transmitted through direct contact with secretions such as mucus. Indirect transmission via fomites, while certainly plausible, is thought to be the least effective mechanism of transmission.6 Following exposure, the incubation period ranges from 7 to 21 days, during which the virus replicates asymptomatically before causing clinical disease.7 Herd immunity for measles requires 93% immunity in the population; public health agencies typically target greater than 95% immunity.8 Humans are the only reservoir for the measles virus, making eradication possible.

The road to eradication began with the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 and subsequent development of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971. As MMR is a live vaccine, 2 doses confer approximately 97% protection.9 The first dose is given at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose is given at 4 to 6 years of age. Immunity is considered lifelong, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization do not recommend routine measles boosters for individuals who have completed the primary 2-dose series.10,11

Widespread vaccination led to a dramatic reduction in incidence, with many countries eliminating measles infections.7 The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, with confirmed cases between 2000 and 2020 ranging from 37 to 1282.12 Vaccination progress stalled in the late 1990s due to vaccine hesitancy resulting from (subsequently debunked) reports of an association between the MMR vaccine and autism.13 Despite efforts to correct this misinformation, many patients continue to espouse these concerns.

Recognizing Measles: Clinical Presentation

Measles, which most often manifests in childhood but also can occur in adults, follows a distinctive clinical course. The prodromal phase is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza (nasal congestion), and conjunctivitis— conjunctivitis—the 3 “Cs” that serve as early warning signs of the disease. Patients may develop small white macules on the buccal mucosa known as Koplik spots (phonetically the fourth “C”), which appear just before the rash. Three to 5 days after the onset of systemic symptoms, patients will develop a classic morbilliform exanthem. In some cases, the exanthem manifests on the head and neck (Figure 1)—first behind the ears and along the hairline, then spreading caudally to the trunk and extremities. The lesions may become confluent, with patients presenting with diffuse erythema. The exanthem fades over several days to weeks, often accompanied by superficial desquamation.14

Given the nonspecificity of the early symptoms of measles, a high index of suspicion is needed for patients presenting with a febrile illness and a morbilliform eruption (Figure 2). Consideration of MMR vaccination status, exposure history, and local outbreak patterns can help guide risk stratification and the need for testing. Immunocompromised individuals, including those receiving immunosuppressive therapies for dermatologic conditions, may present atypically, lacking the prototypical exanthem or displaying milder signs and further complicating the diagnosis.15 The differential diagnosis for measles includes a drug reaction or other viral exanthem, and a detailed history may help elucidate the culprit.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of measles relies on both molecular and serologic testing. Nasopharyngeal swabs for measles polymerase chain reaction testing are obtained using synthetic (noncotton) swabs placed in a viral transport medium. Serum samples also should be collected for measles IgM and IgG antibody testing. Importantly, measles is a reportable illness, and testing may be coordinated with local departments of health.

Determining a patient’s immune status may be important for certain populations. Patients with documented 2-dose MMR vaccination, positive measles IgG serology, or a prior confirmed measles infection are considered immune. While a positive measles IgG indicates immunity, a negative result in an exposed patient should prompt consideration of postexposure prophylaxis with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Many patients, specifically those presenting to dermatology, are taking immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications—a contraindication for vaccination with the live MMR vaccine. At the time of publication, there was a single reported case of a patient taking a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis who had acquired measles.16 While the benefits of titer assessment in patients who are starting or continuing immunomodulatory therapy are not known and currently it is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dermatologists might consider checking MMR titers and vaccinating (or referring for vaccination) nonimmune patients.17

Infection Control

Early identification of a suspected measles case is paramount. Patients in whom measles is a possibility should be isolated as quickly as possible, and the patient and accompanying caregivers should be masked. Clinical staff should don appropriate personal protective equipment, including an N95 mask. Coordination with the local department of health must occur as soon as measles is suspected.

If testing is an option in the outpatient setting, a nasopharyngeal viral swab and serologic titers can be obtained. If testing is not available on site, patients should be sent to appropriate care facilities; prenotification is critical to prevent nosocomial outbreaks. Patients should be encouraged to isolate and avoid public spaces and/or public transport for 4 days following development of an exanthem.18 Offices should develop clinical protocols for suspected measles cases with training for clinical and office staff.

Final Thoughts

As measles outbreaks become more prevalent, it is incumbent upon physicians to remind ourselves of the signs and symptoms of this largely eliminated disease so that we may pursue early detection and intervention strategies. The primary cutaneous manifestations of measles make dermatologists critical to early recognition and containment efforts. Dermatologists should prepare for the arrival of patients with measles by maintaining vigilance for the classic signs of the disease, implementing stringent isolation protocols, verifying patient immunity when appropriate, and partnering closely with public health authorities.

More broadly, efforts to contain and re-establish a paradigm for eliminating measles outbreaks must be pursued. Encouraging vaccination and developing programs to help combat misinformation surrounding vaccines are critical to this effort. In an era of vaccine hesitancy, measles is a multidisciplinary public health emergency. Dermatologists must remain ready.

- Bedford H, Elliman D. Measles rates are rising again. BMJ. 2024;384.

- Harris E. Measles outbreaks grow amid declining vaccination rates. JAMA. 2023;330:2242.

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, et al. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:E420-E428.

- Swartz MK. Measles: public and professional education. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33:367-368.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/measles/

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE, Feinstone WH. Measles. In: Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Elsevier; 2009: 551-565.

- Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490-2502.

- Maintain the vaccination coverage level of 2 doses of the MMR vaccine for children in kindergarten— IID04. Healthy People 2030 website. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/maintain-vaccination-coverage-level-2-doses-mmr-vaccine-children-kindergarten-iid-04

- Franconeri L, Antona D, Cauchemez S, et al. Two-dose measles vaccine effectiveness remains high over time: a French observational study, 2017–2019. Vaccine. 2023;41:5797-5804.

- World Health Organization. Measles. Accessed May 8, 2025. https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles vaccine recommendations. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

- Dyer C. Lancet retracts Wakefield’s MMR paper. BMJ. 2010;340.

- Alves Graber EM, Andrade FJ, Bost W, et al. An update and review of measles for emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:610-615.

- Kaplan LJ, Daum RS, Smaron M, et al. Severe measles in immunocompromised patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1237-1241.

- Takahashi E, Kurosaka D, Yoshida K, et al. Onset of modified measles after etanercept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Japanese J Clin Immunol. 2010;33:37-41.

- Worth A, Waldman RA, Dieckhaus K, et al. Art of prevention: our approach to the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in adult patients vaccinated against measles before 1968 on biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6:94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical overview of measles (rubeola). Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- Bedford H, Elliman D. Measles rates are rising again. BMJ. 2024;384.

- Harris E. Measles outbreaks grow amid declining vaccination rates. JAMA. 2023;330:2242.

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, et al. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:E420-E428.

- Swartz MK. Measles: public and professional education. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33:367-368.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/measles/

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE, Feinstone WH. Measles. In: Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Elsevier; 2009: 551-565.

- Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490-2502.

- Maintain the vaccination coverage level of 2 doses of the MMR vaccine for children in kindergarten— IID04. Healthy People 2030 website. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/maintain-vaccination-coverage-level-2-doses-mmr-vaccine-children-kindergarten-iid-04

- Franconeri L, Antona D, Cauchemez S, et al. Two-dose measles vaccine effectiveness remains high over time: a French observational study, 2017–2019. Vaccine. 2023;41:5797-5804.

- World Health Organization. Measles. Accessed May 8, 2025. https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles vaccine recommendations. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

- Dyer C. Lancet retracts Wakefield’s MMR paper. BMJ. 2010;340.

- Alves Graber EM, Andrade FJ, Bost W, et al. An update and review of measles for emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:610-615.

- Kaplan LJ, Daum RS, Smaron M, et al. Severe measles in immunocompromised patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1237-1241.

- Takahashi E, Kurosaka D, Yoshida K, et al. Onset of modified measles after etanercept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Japanese J Clin Immunol. 2010;33:37-41.

- Worth A, Waldman RA, Dieckhaus K, et al. Art of prevention: our approach to the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in adult patients vaccinated against measles before 1968 on biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6:94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical overview of measles (rubeola). Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

The Rise of Antifungal-Resistant Dermatophyte Infections: What Dermatologists Need to Know

The Rise of Antifungal-Resistant Dermatophyte Infections: What Dermatologists Need to Know

Worldwide, it is estimated that up to 1 in 5 individuals will experience a dermatophyte infection (commonly called ringworm or tinea infection) in their lifetime.1 Historically, dermatophyte infections have been considered relatively minor conditions usually treated with short courses of topical antifungals.2 Oral antifungals historically were needed only for patients with nail or hair shaft infections or extensive cutaneous fungal infections, which typically occurred in immunosuppressed patients.2 However, the landscape is changing rapidly due to the global emergence of severe dermatophyte infections that frequently are resistant to first-line antifungal medications.3-5 In this article, we aimed to review the epidemiology of emerging dermatophyte infections and provide dermatologists with information needed for effective diagnosis and management.

Emergence of Trichophyton indotineae

In recent decades, public health officials and dermatologists have noted with concern the spread of the recently emerged dermatophyte species Trichophyton indotineae in South Asia.3,6 This species (previously known as Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VIII) usually is transmitted from person to person, either through direct skin-to-skin contact or by fomites.4,6 Potential sexual transmission of T indotineae infections also has been reported,7 and it is possible that animals may serve as reservoirs for this pathogen, although there are no known reports of direct spread from animals to humans.8,9 Major outbreaks of T indotineae are ongoing in South Asia, and cases have been documented in 6 continents.10-12 In the United States, most but not all cases have occurred in immigrants from or recently returned travelers to South Asia.6,13 The emergence and spread of T indotineae is hypothesized to be promoted by the misuse and overuse of topical antifungal products, particularly those containing combinations of potent corticosteroids with other antimicrobial drugs.14,15

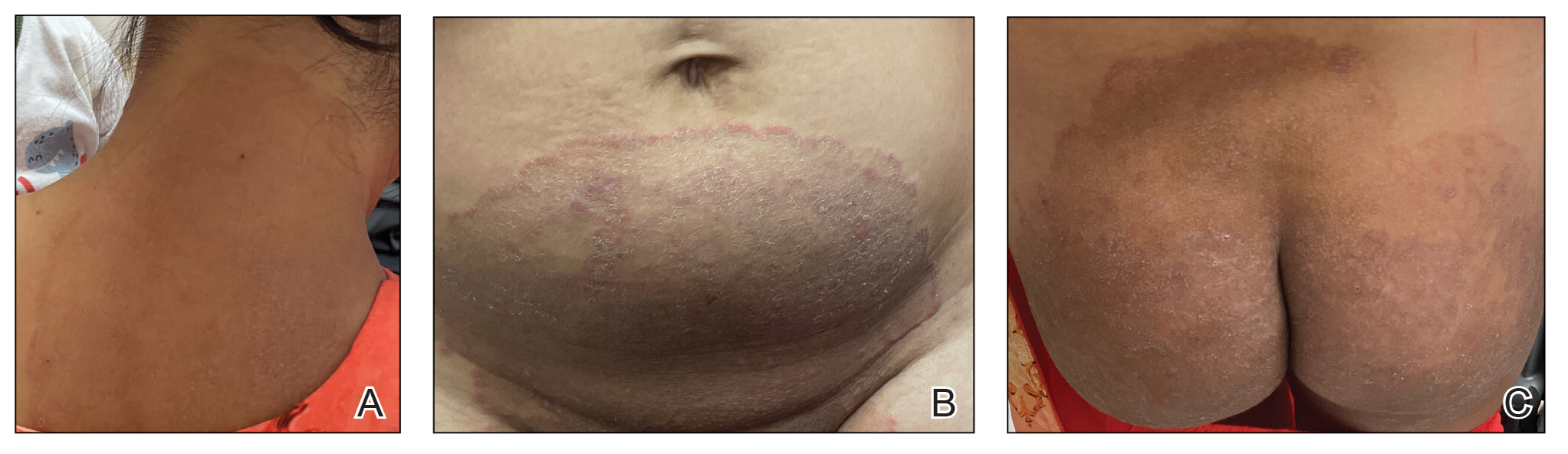

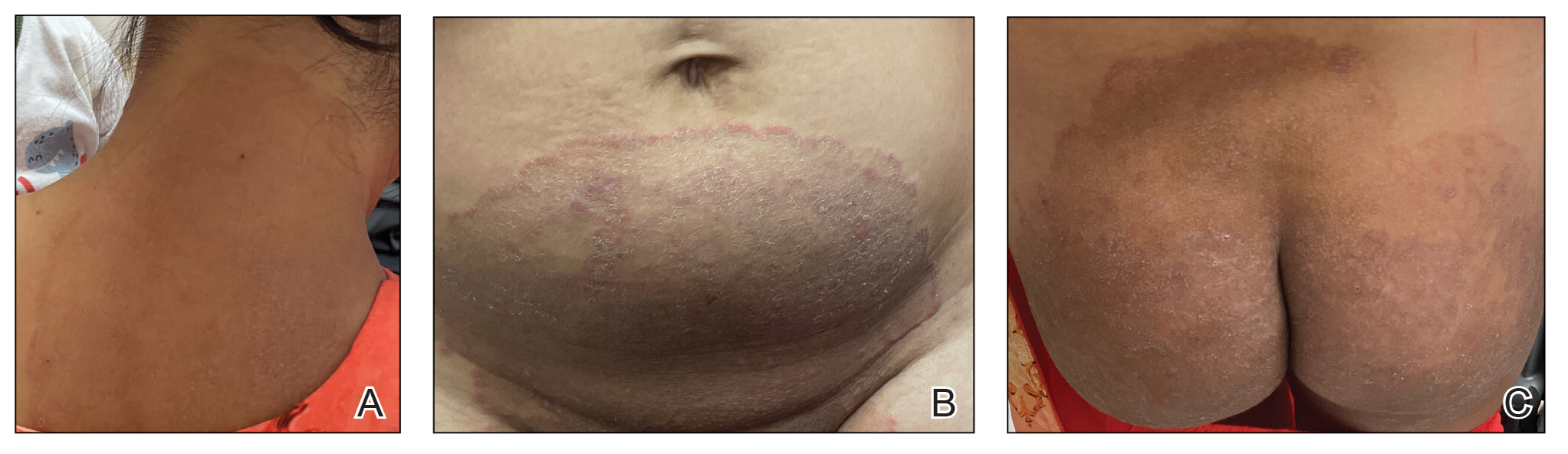

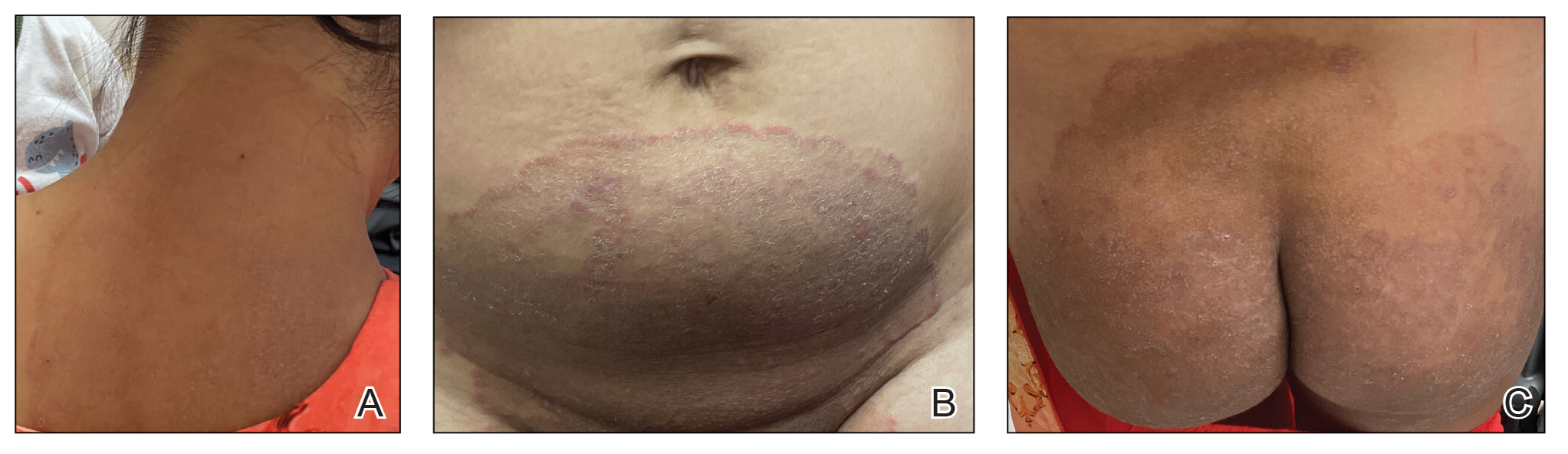

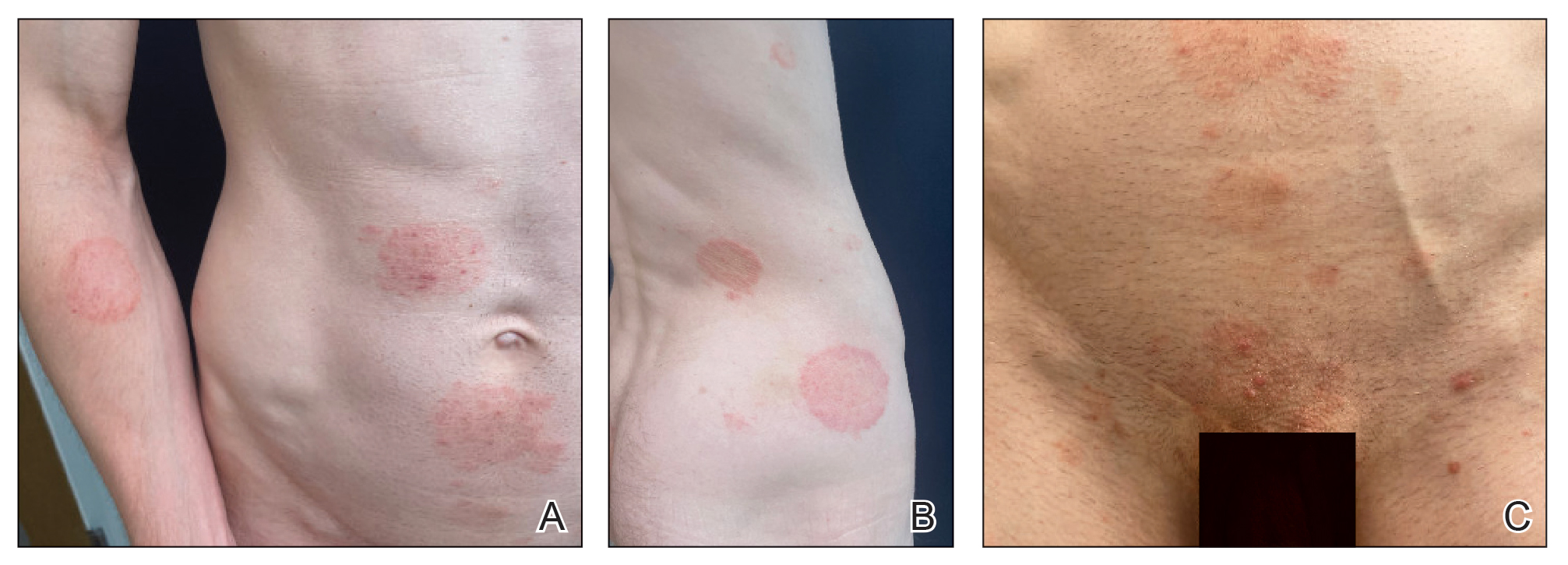

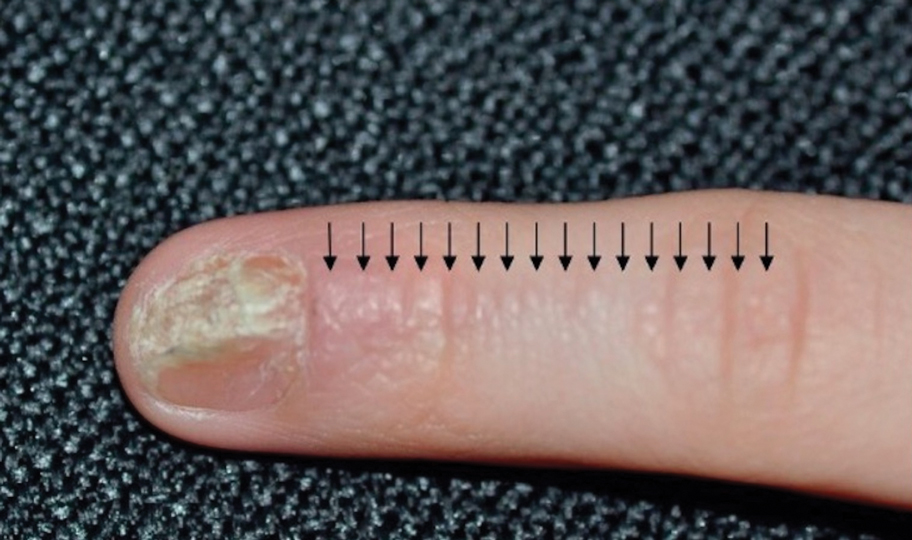

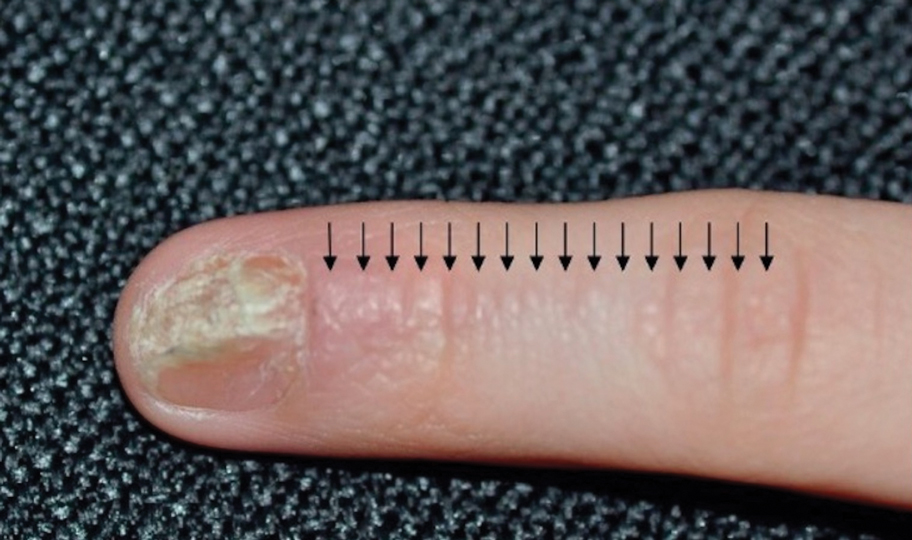

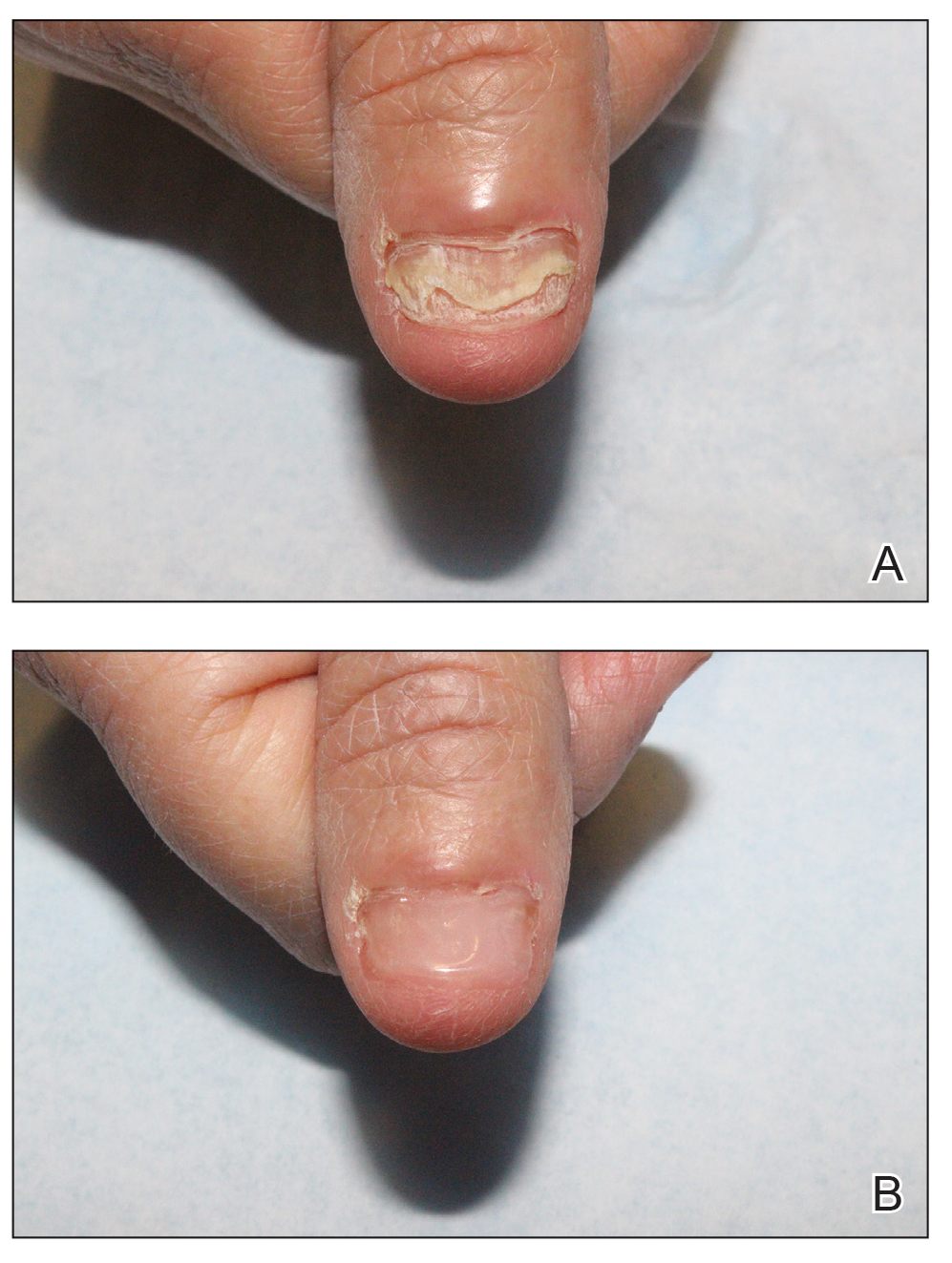

Cutaneous manifestations of T indotineae infections tend to cover large body surface areas, recur frequently, and pose substantial treatment challenges.6,13,16 Several clinical presentations have been documented, including erythematous, scaly concentric plaques; papulosquamous lesions; pustular forms; and corticosteroid-modified disease (Figure 1).6,16 Affected patients seldom are immunocompromised and often have a history of multiple failed courses of topical or oral antifungals, including oral terbinafine.13 Many also have been prescribed topical corticosteroids or have used over-the-counter topical corticosteroids, which worsen the rash.17

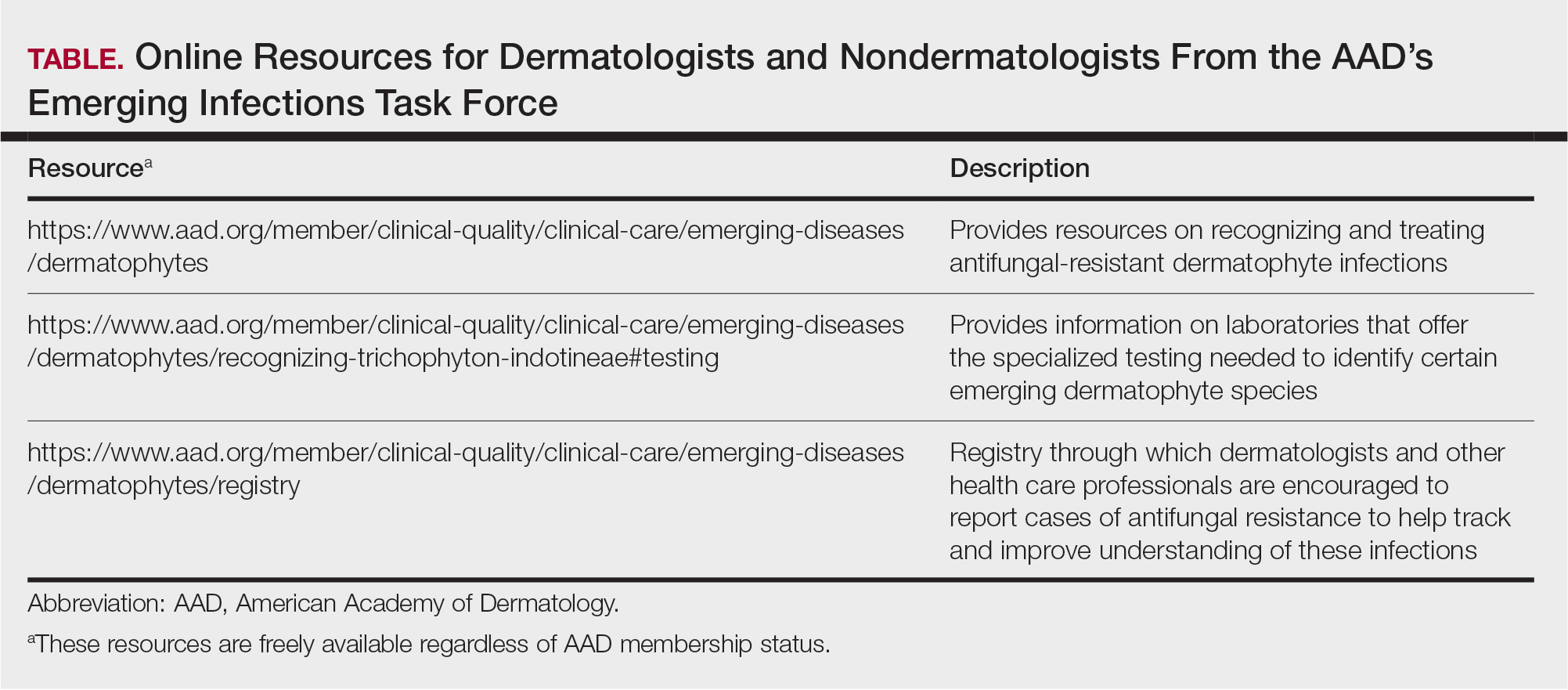

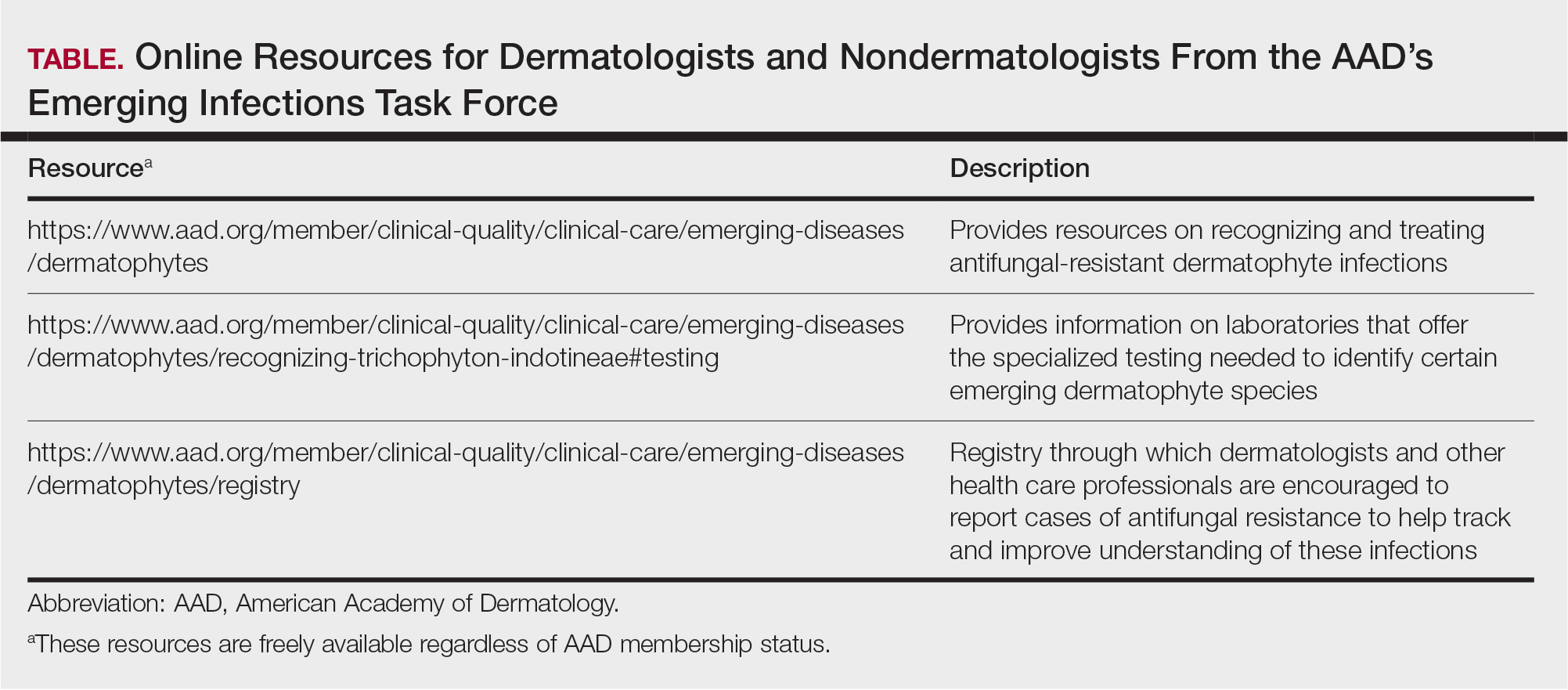

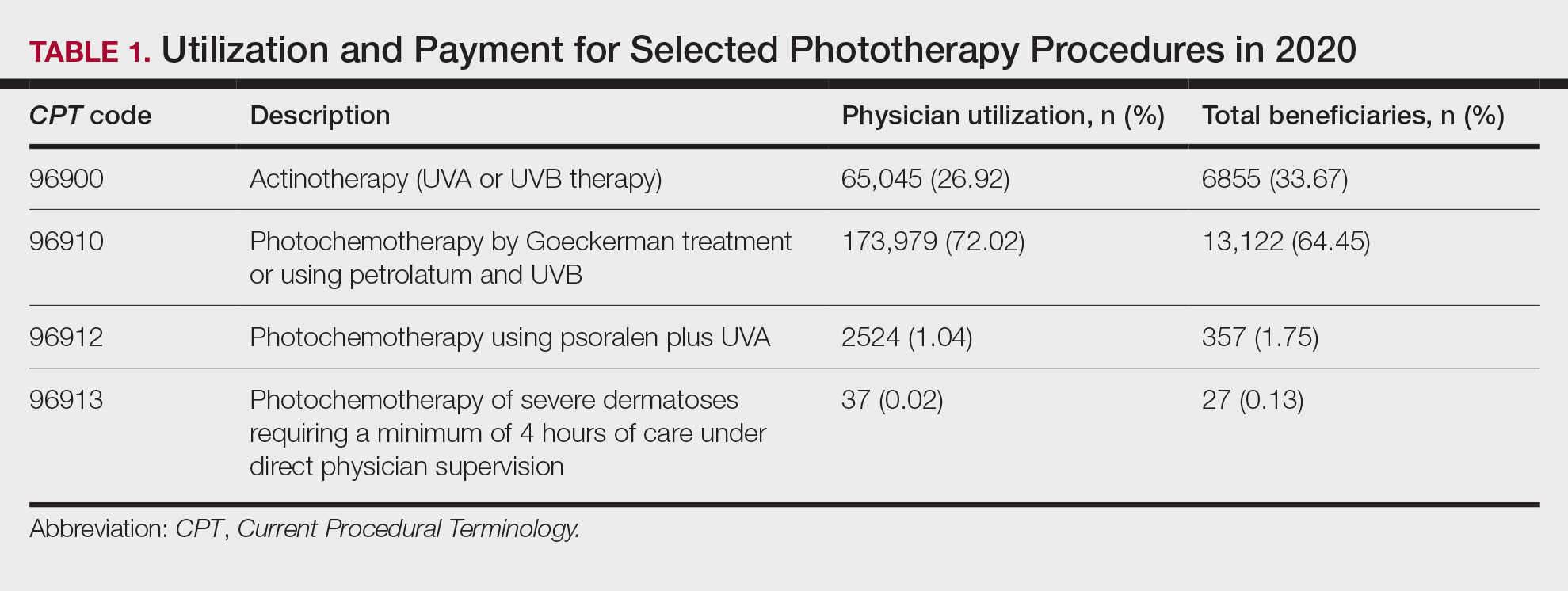

Direct microscopy with potassium hydroxide could be used to confirm the diagnosis of dermatophyte infection, but it does not distinguish T indotineae from other dermatophyte species.2,6 Importantly, culture-based testing usually will misidentify T indotineae as other Trichophyton species such as the more common T mentagrophytes or Trichophyton interdigitale. Definitive identification of T indotineae requires advanced molecular techniques that are available only at select laboratories.6 Unfortunately, availability of such testing is limited (Table), and results may take several weeks; therefore, it is suggested that dermatologists who suspect T indotineae infections based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation begin antifungal treatment after confirmation of dermatophyte infection but not wait for definitive confirmation of the causative organism.16

Itraconazole is considered the first-line therapy for T indotineae infection, as terbinafine usually is ineffective due to mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene.16 Dermatologists should be aware that itraconazole is available in different formulations that can affect absorption. The oral solution has greater bioavailability and should be taken on an empty stomach, whereas the capsules are required to be taken with food for effective absorption; the capsules also should be taken with an acidic beverage such as orange juice. Dermatologists should carefully assess for drug-drug interactions when prescribing itraconazole, given its extensive interaction profile with numerous other medications. Patients may require treatment with itraconazole (100 mg/d or 200 mg/d) for a minimum of 6 to 8 weeks until complete clearance has been achieved and ideally a negative potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings has been obtained. A longer treatment period (eg, ≥3 months) frequently is needed, and relapses are common.6,16,18 Regular follow-up is needed to monitor for infection clearance and recurrences. It is important to note that cases of itraconazole resistance have been reported, although this currently appears to be uncommon.19,20

Other Emerging Dermatophytes to Watch

Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause of dermatophyte infections among humans,21 and cases of terbinafine-resistant T rubrum infections have been reported increasingly in the United States and Canada.5,22-24 Onychomycosis caused by terbinafine-resistant T rubrum has been documented, and patients may have infections that do not respond to terbinafine given at the standard dose and duration.22,23 Case reports have indicated successful treatment using itraconazole 200 mg/d and posaconazole 300 mg/d.5,23

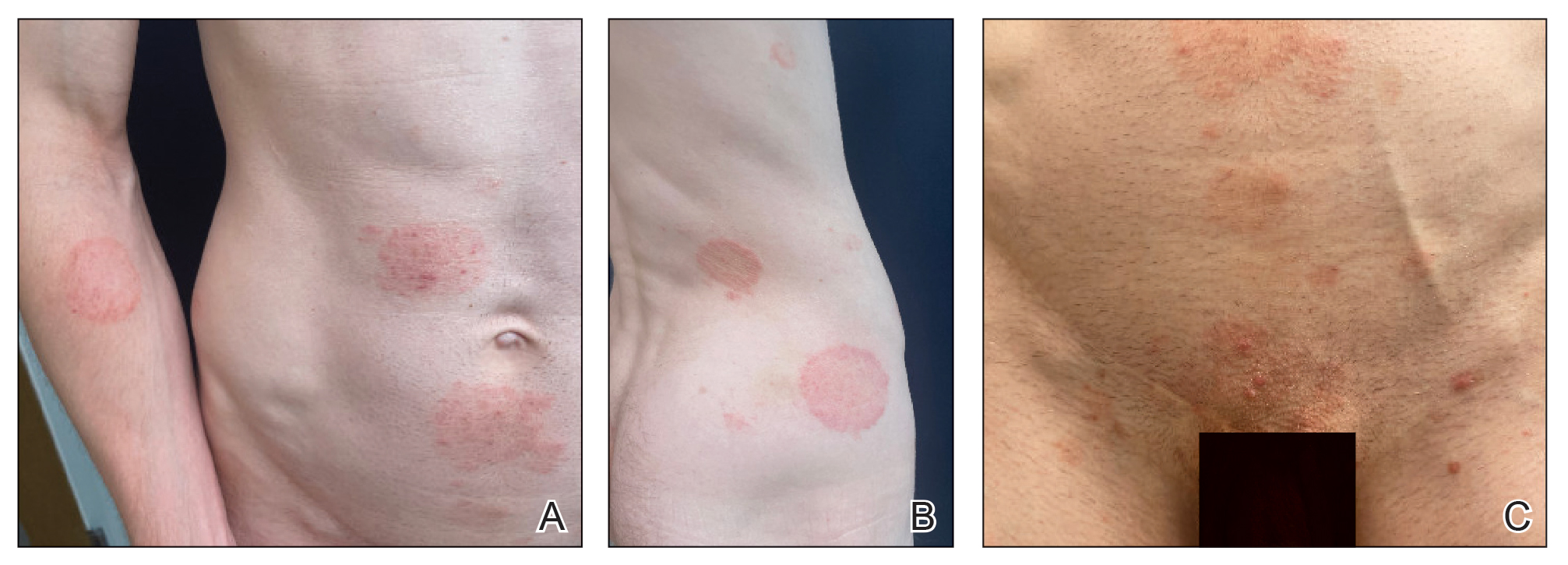

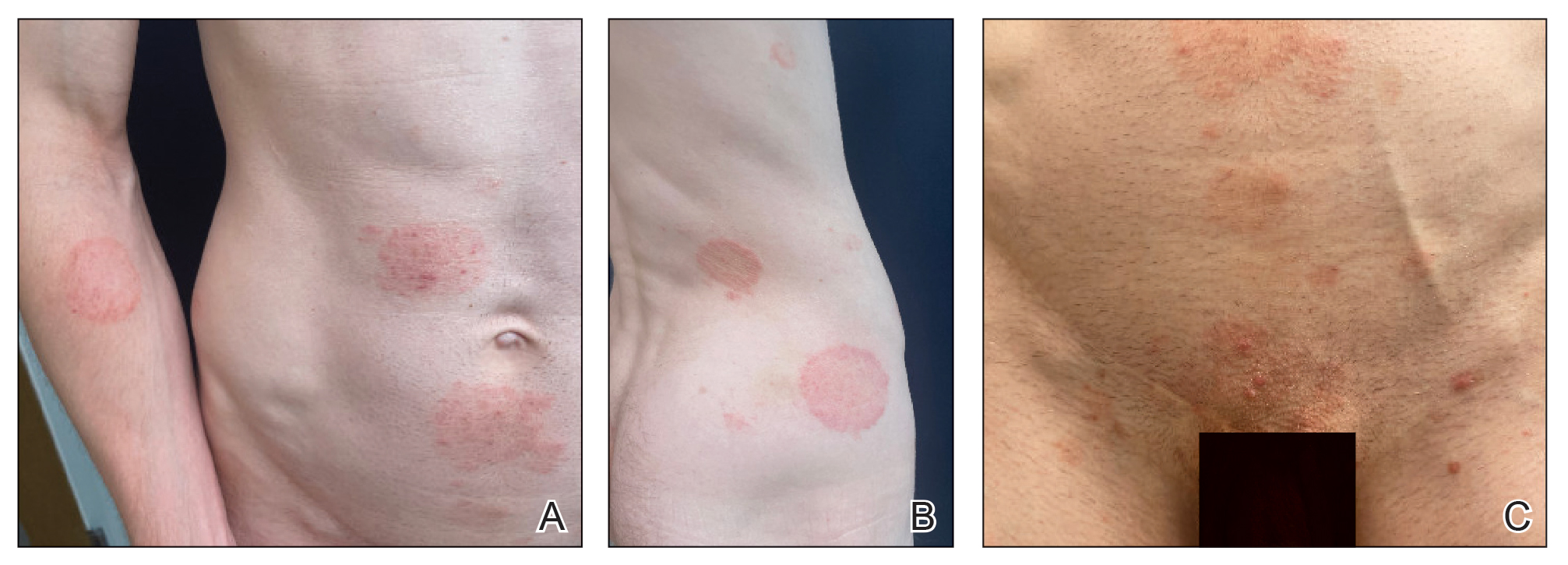

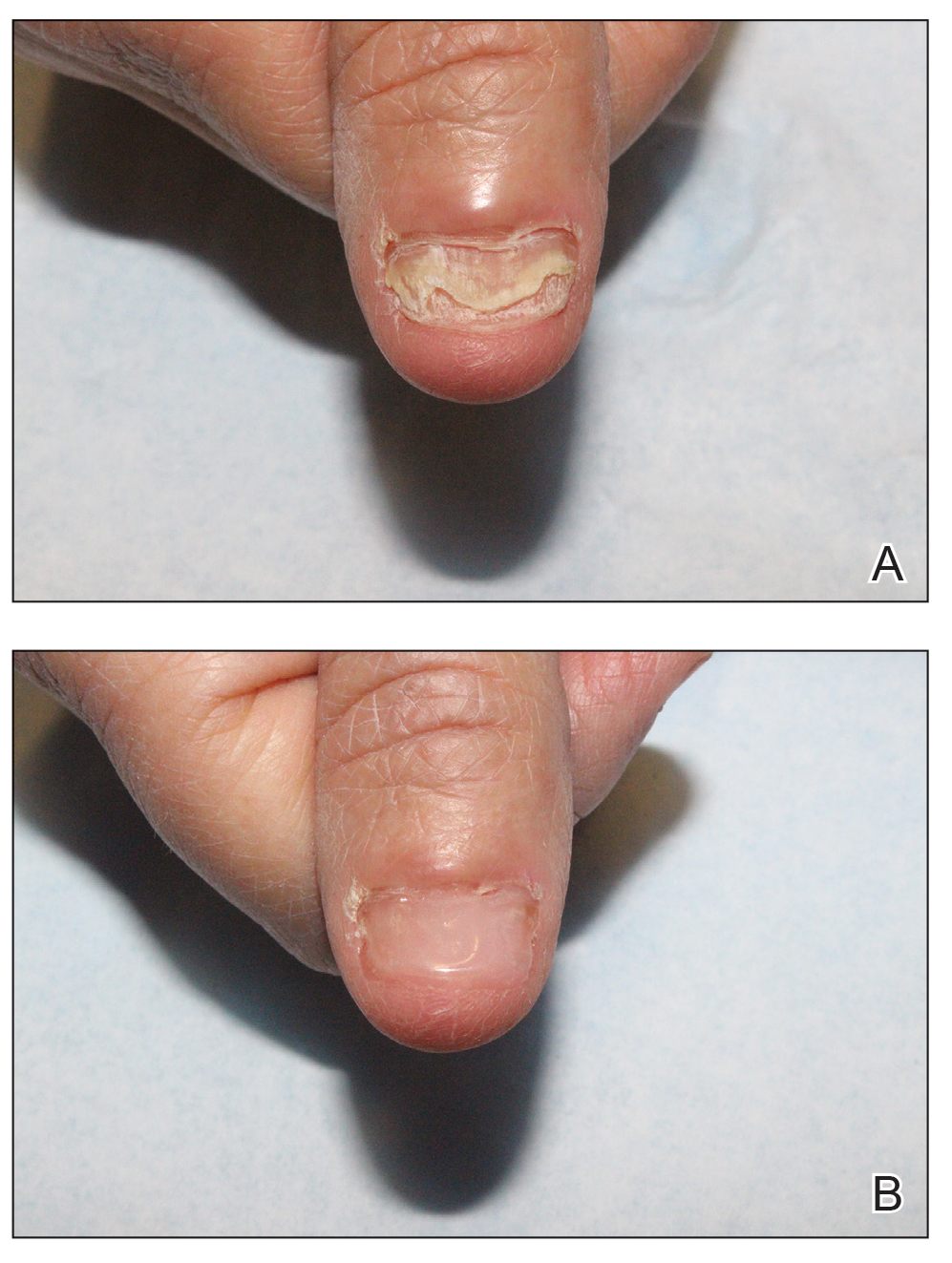

Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII (TMVII) is an emerging dermatophyte that recently has been reported as a cause of sexually transmitted dermatophyte infections in Europe and the United States primarily affecting men who have sex with men.25-27 Patients may present with pruritic, annular, scaly patches and plaques involving the trunk, groin, genital region, or face (Figure 2). Although closely related to T indotineae, TMVII differs in that it more often affects the genital region, generally is susceptible to terbinafine, and in the United States and Europe usually is not related to travel or immigration involving South Asia.26 Although TMVII has not been associated with antifungal resistance, awareness among dermatologists is important because patients may experience inflamed, painful, and persistent rashes that can lead to secondary bacterial infection or scarring, and physicians might mistake it for mimics including eczema or psoriasis.25,26

Importance of Judicious Antifungal Use

Optimizing the use of antifungals is critical to improving patient outcomes and preserving available treatment options.28,29 A retrospective analysis of commercial health insurance data estimated that topical antifungal prescriptions were potentially unnecessary for more than half of the more than 560,000 patients who were prescribed these medications in 2023. In this study, it also was observed that only 16% of patients prescribed a topical antifungal had received diagnostic testing, with low rates across specialties.30 This is concerning because even among board-certified dermatologists, incorrect diagnosis of suspected fungal skin infections can occur; in one survey-based study of board-certified dermatologists who were presented with dermatomycosis images, respondents categorized cases with greater than 75% accuracy in only 31% (4/13) of instances.31 Clotrimazole-betamethasone is among the most commonly prescribed topical antifungals in the United States,14,32 and 2 recent retrospective analyses highlighted that the majority of patients prescribed this medication did not receive any fungal diagnostic testing.33,34

Final Thoughts

In an era of emerging antifungal-resistant dermatophyte infections, it is important for dermatologists to educate nondermatologists about the importance of using diagnostic testing for suspected dermatophyte infections.14,28 Dermatologists also can educate nondermatologist colleagues on the importance of avoiding the use of topical combination antifungal/corticosteroid medications and referring for dermatologic evaluation when diagnoses are uncertain.33,34 Strategies for education by dermatologists could include giving workshops, creating educational materials, and fostering open communication about optimal treatment practices and referral parameters for suspected dermatophyte infections.

- Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174, 177-168.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Uhrlaß S, Verma SB, Gräser Y, et al. Trichophyton indotineae—an emerging pathogen causing recalcitrant dermatophytoses in India and worldwide—a multidimensional perspective. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:757. doi:10.3390/jof8070757

- Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: I. epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:154-175.

- Chen E, Ghannoum M, Elewski BE. Treatment]resistant tinea corporis, a potential public health issue. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:164-165.

- Caplan AS. Notes from the field: first reported US cases of tinea caused by Trichophyton indotineae—New York City, December 2021–March 2023. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2023;72:536-537. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7219a4

- Spivack S, Gold JA, Lockhart SR, et al. Potential sexual transmission of antifungal-resistant Trichophyton indotineae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30:807.

- Jabet A, Brun S, Normand AC, et al. Extensive dermatophytosis caused by terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:229-233.

- Thakur S, Spruijtenburg B, Abhishek, et al. Whole genome sequence analysis of terbinafine resistant and susceptible Trichophyton isolates from human and animal origin. Mycopathologia. 2025;190:13.

- Lockhart SR, Chowdhary A, Gold JA. The rapid emergence of antifungal-resistant human-pathogenic fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:818-832.

- Mosam A, Shuping L, Naicker S, et al. A case of antifungal-resistant ringworm infection in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, caused by Trichophyton indotineae. Public Health Bulletin South Africa. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.phbsa.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/12PHBSA-Ringworm-Article-2023.pdf

- Cañete-Gibas CF, Mele J, Patterson HP, et al. Terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes and the presence of Trichophyton indotineae in North America. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61:E0056223

- Caplan AS, Todd GC, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical course, antifungal susceptibility, and genomic sequencing of Trichophyton indotineae. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:701-709. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1126

- Benedict K. Topical antifungal prescribing for Medicare Part D beneficiaries—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:1-5.

- Verma SB. Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:718-719.

- Khurana A, Sharath S, Sardana K, et al. Clinico-mycological and therapeutic updates on cutaneous dermatophytic infections in the era of Trichophyton indotineae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:315-323. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.024

- Verma S. Steroid modified tinea. BMJ. 2017;356:j973.

- Khurana A, Agarwal A, Agrawal D, et al. Effect of different itraconazole dosing regimens on cure rates, treatment duration, safety, and relapse rates in adult patients with tinea corporis/cruris: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1269-1278.

- Burmester A, Hipler UC, Uhrlaß S, et al. Indian Trichophyton mentagrophytes squalene epoxidase erg1 double mutants show high proportion of combined fluconazole and terbinafine resistance. Mycoses. 2020;63:1175-1180.

- Bhuiyan MSI, Verma SB, Illigner GM, et al. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VIII/Trichophyton indotineae infection and antifungal resistance in Bangladesh. J Fungi (Basel). 2024;10:768. doi:10.3390 /jof10110768

- Hay RJ. Chapter 82: superficial mycoses. In: Ryan ET, Hill DR, Solomon T, et al, eds. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2020:648-652.

- Gupta AK, Cooper EA, Wang T, et al. Detection of squalene epoxidase mutations in United States patients with onychomycosis: implications for management. J Invest Dermatol. 2023;143:2476-2483.E2477.

- Hwang JK, Bakotic WL, Gold JA, et al. Isolation of terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton rubrum from onychomycosis patients who failed treatment at an academic center in New York, United States. J Fungi. 2023;9:710.

- Gu D, Hatch M, Ghannoum M, et al. Treatment-resistant dermatophytosis: a representative case highlighting an emerging public health threat. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:1153-1155.

- Jabet A, Dellière S, Seang S, et al. Sexually transmitted Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII infection among men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1411-1414.

- Zucker J, Caplan AS, Gunaratne SH, et al. Notes from the field: Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII—New York City, April-July 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:985-988.

- Jabet A, Bérot V, Chiarabini T, et al. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VII infections among men who have sex with men in France: an ongoing phenomenon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:407-415.

- Caplan AS, Gold JA, Smith DJ, et al. Improving antifungal stewardship in dermatology in an era of emerging dermatophyte resistance. JAAD International. 2024;15:168-169.

- Elewski B. A call for antifungal stewardship. Br J Dermatol. 2020; 183:798-799.

- Gold JAW, Benedict K, Caplan AS, et al. High rates of potentially unnecessary topical antifungal prescribing in a large commercial health insurance claims database, United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025:S0190-9622(25)00098-2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.01.022

- Yadgar RJ, Bhatia N, Friedman A. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly misdiagnosed: a survey-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:562-563.

- Flint ND, Rhoads JLW, Carlisle R, et al. The continued inappropriate use and overuse of combination topical clotrimazole-betamethasone. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327854686

- Currie DW, Caplan AS, Benedict K, et al. Prescribing of clotrimazolebetamethasone dipropionate, a topical combination corticosteroidantifungal product, for Medicare part D beneficiaries, United States, 2016–2022. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2024;4:E174.

- Gold JA, Caplan AS, Benedict K, et al. Clotrimazole-betamethasone dipropionate prescribing for nonfungal skin conditions. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7:E2411721-E2411721.

Worldwide, it is estimated that up to 1 in 5 individuals will experience a dermatophyte infection (commonly called ringworm or tinea infection) in their lifetime.1 Historically, dermatophyte infections have been considered relatively minor conditions usually treated with short courses of topical antifungals.2 Oral antifungals historically were needed only for patients with nail or hair shaft infections or extensive cutaneous fungal infections, which typically occurred in immunosuppressed patients.2 However, the landscape is changing rapidly due to the global emergence of severe dermatophyte infections that frequently are resistant to first-line antifungal medications.3-5 In this article, we aimed to review the epidemiology of emerging dermatophyte infections and provide dermatologists with information needed for effective diagnosis and management.

Emergence of Trichophyton indotineae

In recent decades, public health officials and dermatologists have noted with concern the spread of the recently emerged dermatophyte species Trichophyton indotineae in South Asia.3,6 This species (previously known as Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VIII) usually is transmitted from person to person, either through direct skin-to-skin contact or by fomites.4,6 Potential sexual transmission of T indotineae infections also has been reported,7 and it is possible that animals may serve as reservoirs for this pathogen, although there are no known reports of direct spread from animals to humans.8,9 Major outbreaks of T indotineae are ongoing in South Asia, and cases have been documented in 6 continents.10-12 In the United States, most but not all cases have occurred in immigrants from or recently returned travelers to South Asia.6,13 The emergence and spread of T indotineae is hypothesized to be promoted by the misuse and overuse of topical antifungal products, particularly those containing combinations of potent corticosteroids with other antimicrobial drugs.14,15

Cutaneous manifestations of T indotineae infections tend to cover large body surface areas, recur frequently, and pose substantial treatment challenges.6,13,16 Several clinical presentations have been documented, including erythematous, scaly concentric plaques; papulosquamous lesions; pustular forms; and corticosteroid-modified disease (Figure 1).6,16 Affected patients seldom are immunocompromised and often have a history of multiple failed courses of topical or oral antifungals, including oral terbinafine.13 Many also have been prescribed topical corticosteroids or have used over-the-counter topical corticosteroids, which worsen the rash.17

Direct microscopy with potassium hydroxide could be used to confirm the diagnosis of dermatophyte infection, but it does not distinguish T indotineae from other dermatophyte species.2,6 Importantly, culture-based testing usually will misidentify T indotineae as other Trichophyton species such as the more common T mentagrophytes or Trichophyton interdigitale. Definitive identification of T indotineae requires advanced molecular techniques that are available only at select laboratories.6 Unfortunately, availability of such testing is limited (Table), and results may take several weeks; therefore, it is suggested that dermatologists who suspect T indotineae infections based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation begin antifungal treatment after confirmation of dermatophyte infection but not wait for definitive confirmation of the causative organism.16

Itraconazole is considered the first-line therapy for T indotineae infection, as terbinafine usually is ineffective due to mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene.16 Dermatologists should be aware that itraconazole is available in different formulations that can affect absorption. The oral solution has greater bioavailability and should be taken on an empty stomach, whereas the capsules are required to be taken with food for effective absorption; the capsules also should be taken with an acidic beverage such as orange juice. Dermatologists should carefully assess for drug-drug interactions when prescribing itraconazole, given its extensive interaction profile with numerous other medications. Patients may require treatment with itraconazole (100 mg/d or 200 mg/d) for a minimum of 6 to 8 weeks until complete clearance has been achieved and ideally a negative potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings has been obtained. A longer treatment period (eg, ≥3 months) frequently is needed, and relapses are common.6,16,18 Regular follow-up is needed to monitor for infection clearance and recurrences. It is important to note that cases of itraconazole resistance have been reported, although this currently appears to be uncommon.19,20

Other Emerging Dermatophytes to Watch

Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause of dermatophyte infections among humans,21 and cases of terbinafine-resistant T rubrum infections have been reported increasingly in the United States and Canada.5,22-24 Onychomycosis caused by terbinafine-resistant T rubrum has been documented, and patients may have infections that do not respond to terbinafine given at the standard dose and duration.22,23 Case reports have indicated successful treatment using itraconazole 200 mg/d and posaconazole 300 mg/d.5,23

Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII (TMVII) is an emerging dermatophyte that recently has been reported as a cause of sexually transmitted dermatophyte infections in Europe and the United States primarily affecting men who have sex with men.25-27 Patients may present with pruritic, annular, scaly patches and plaques involving the trunk, groin, genital region, or face (Figure 2). Although closely related to T indotineae, TMVII differs in that it more often affects the genital region, generally is susceptible to terbinafine, and in the United States and Europe usually is not related to travel or immigration involving South Asia.26 Although TMVII has not been associated with antifungal resistance, awareness among dermatologists is important because patients may experience inflamed, painful, and persistent rashes that can lead to secondary bacterial infection or scarring, and physicians might mistake it for mimics including eczema or psoriasis.25,26

Importance of Judicious Antifungal Use

Optimizing the use of antifungals is critical to improving patient outcomes and preserving available treatment options.28,29 A retrospective analysis of commercial health insurance data estimated that topical antifungal prescriptions were potentially unnecessary for more than half of the more than 560,000 patients who were prescribed these medications in 2023. In this study, it also was observed that only 16% of patients prescribed a topical antifungal had received diagnostic testing, with low rates across specialties.30 This is concerning because even among board-certified dermatologists, incorrect diagnosis of suspected fungal skin infections can occur; in one survey-based study of board-certified dermatologists who were presented with dermatomycosis images, respondents categorized cases with greater than 75% accuracy in only 31% (4/13) of instances.31 Clotrimazole-betamethasone is among the most commonly prescribed topical antifungals in the United States,14,32 and 2 recent retrospective analyses highlighted that the majority of patients prescribed this medication did not receive any fungal diagnostic testing.33,34

Final Thoughts

In an era of emerging antifungal-resistant dermatophyte infections, it is important for dermatologists to educate nondermatologists about the importance of using diagnostic testing for suspected dermatophyte infections.14,28 Dermatologists also can educate nondermatologist colleagues on the importance of avoiding the use of topical combination antifungal/corticosteroid medications and referring for dermatologic evaluation when diagnoses are uncertain.33,34 Strategies for education by dermatologists could include giving workshops, creating educational materials, and fostering open communication about optimal treatment practices and referral parameters for suspected dermatophyte infections.

Worldwide, it is estimated that up to 1 in 5 individuals will experience a dermatophyte infection (commonly called ringworm or tinea infection) in their lifetime.1 Historically, dermatophyte infections have been considered relatively minor conditions usually treated with short courses of topical antifungals.2 Oral antifungals historically were needed only for patients with nail or hair shaft infections or extensive cutaneous fungal infections, which typically occurred in immunosuppressed patients.2 However, the landscape is changing rapidly due to the global emergence of severe dermatophyte infections that frequently are resistant to first-line antifungal medications.3-5 In this article, we aimed to review the epidemiology of emerging dermatophyte infections and provide dermatologists with information needed for effective diagnosis and management.

Emergence of Trichophyton indotineae

In recent decades, public health officials and dermatologists have noted with concern the spread of the recently emerged dermatophyte species Trichophyton indotineae in South Asia.3,6 This species (previously known as Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VIII) usually is transmitted from person to person, either through direct skin-to-skin contact or by fomites.4,6 Potential sexual transmission of T indotineae infections also has been reported,7 and it is possible that animals may serve as reservoirs for this pathogen, although there are no known reports of direct spread from animals to humans.8,9 Major outbreaks of T indotineae are ongoing in South Asia, and cases have been documented in 6 continents.10-12 In the United States, most but not all cases have occurred in immigrants from or recently returned travelers to South Asia.6,13 The emergence and spread of T indotineae is hypothesized to be promoted by the misuse and overuse of topical antifungal products, particularly those containing combinations of potent corticosteroids with other antimicrobial drugs.14,15

Cutaneous manifestations of T indotineae infections tend to cover large body surface areas, recur frequently, and pose substantial treatment challenges.6,13,16 Several clinical presentations have been documented, including erythematous, scaly concentric plaques; papulosquamous lesions; pustular forms; and corticosteroid-modified disease (Figure 1).6,16 Affected patients seldom are immunocompromised and often have a history of multiple failed courses of topical or oral antifungals, including oral terbinafine.13 Many also have been prescribed topical corticosteroids or have used over-the-counter topical corticosteroids, which worsen the rash.17

Direct microscopy with potassium hydroxide could be used to confirm the diagnosis of dermatophyte infection, but it does not distinguish T indotineae from other dermatophyte species.2,6 Importantly, culture-based testing usually will misidentify T indotineae as other Trichophyton species such as the more common T mentagrophytes or Trichophyton interdigitale. Definitive identification of T indotineae requires advanced molecular techniques that are available only at select laboratories.6 Unfortunately, availability of such testing is limited (Table), and results may take several weeks; therefore, it is suggested that dermatologists who suspect T indotineae infections based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation begin antifungal treatment after confirmation of dermatophyte infection but not wait for definitive confirmation of the causative organism.16

Itraconazole is considered the first-line therapy for T indotineae infection, as terbinafine usually is ineffective due to mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene.16 Dermatologists should be aware that itraconazole is available in different formulations that can affect absorption. The oral solution has greater bioavailability and should be taken on an empty stomach, whereas the capsules are required to be taken with food for effective absorption; the capsules also should be taken with an acidic beverage such as orange juice. Dermatologists should carefully assess for drug-drug interactions when prescribing itraconazole, given its extensive interaction profile with numerous other medications. Patients may require treatment with itraconazole (100 mg/d or 200 mg/d) for a minimum of 6 to 8 weeks until complete clearance has been achieved and ideally a negative potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings has been obtained. A longer treatment period (eg, ≥3 months) frequently is needed, and relapses are common.6,16,18 Regular follow-up is needed to monitor for infection clearance and recurrences. It is important to note that cases of itraconazole resistance have been reported, although this currently appears to be uncommon.19,20

Other Emerging Dermatophytes to Watch

Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause of dermatophyte infections among humans,21 and cases of terbinafine-resistant T rubrum infections have been reported increasingly in the United States and Canada.5,22-24 Onychomycosis caused by terbinafine-resistant T rubrum has been documented, and patients may have infections that do not respond to terbinafine given at the standard dose and duration.22,23 Case reports have indicated successful treatment using itraconazole 200 mg/d and posaconazole 300 mg/d.5,23

Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII (TMVII) is an emerging dermatophyte that recently has been reported as a cause of sexually transmitted dermatophyte infections in Europe and the United States primarily affecting men who have sex with men.25-27 Patients may present with pruritic, annular, scaly patches and plaques involving the trunk, groin, genital region, or face (Figure 2). Although closely related to T indotineae, TMVII differs in that it more often affects the genital region, generally is susceptible to terbinafine, and in the United States and Europe usually is not related to travel or immigration involving South Asia.26 Although TMVII has not been associated with antifungal resistance, awareness among dermatologists is important because patients may experience inflamed, painful, and persistent rashes that can lead to secondary bacterial infection or scarring, and physicians might mistake it for mimics including eczema or psoriasis.25,26

Importance of Judicious Antifungal Use

Optimizing the use of antifungals is critical to improving patient outcomes and preserving available treatment options.28,29 A retrospective analysis of commercial health insurance data estimated that topical antifungal prescriptions were potentially unnecessary for more than half of the more than 560,000 patients who were prescribed these medications in 2023. In this study, it also was observed that only 16% of patients prescribed a topical antifungal had received diagnostic testing, with low rates across specialties.30 This is concerning because even among board-certified dermatologists, incorrect diagnosis of suspected fungal skin infections can occur; in one survey-based study of board-certified dermatologists who were presented with dermatomycosis images, respondents categorized cases with greater than 75% accuracy in only 31% (4/13) of instances.31 Clotrimazole-betamethasone is among the most commonly prescribed topical antifungals in the United States,14,32 and 2 recent retrospective analyses highlighted that the majority of patients prescribed this medication did not receive any fungal diagnostic testing.33,34

Final Thoughts

In an era of emerging antifungal-resistant dermatophyte infections, it is important for dermatologists to educate nondermatologists about the importance of using diagnostic testing for suspected dermatophyte infections.14,28 Dermatologists also can educate nondermatologist colleagues on the importance of avoiding the use of topical combination antifungal/corticosteroid medications and referring for dermatologic evaluation when diagnoses are uncertain.33,34 Strategies for education by dermatologists could include giving workshops, creating educational materials, and fostering open communication about optimal treatment practices and referral parameters for suspected dermatophyte infections.

- Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174, 177-168.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Uhrlaß S, Verma SB, Gräser Y, et al. Trichophyton indotineae—an emerging pathogen causing recalcitrant dermatophytoses in India and worldwide—a multidimensional perspective. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:757. doi:10.3390/jof8070757

- Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: I. epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:154-175.

- Chen E, Ghannoum M, Elewski BE. Treatment]resistant tinea corporis, a potential public health issue. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:164-165.

- Caplan AS. Notes from the field: first reported US cases of tinea caused by Trichophyton indotineae—New York City, December 2021–March 2023. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2023;72:536-537. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7219a4

- Spivack S, Gold JA, Lockhart SR, et al. Potential sexual transmission of antifungal-resistant Trichophyton indotineae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30:807.

- Jabet A, Brun S, Normand AC, et al. Extensive dermatophytosis caused by terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:229-233.

- Thakur S, Spruijtenburg B, Abhishek, et al. Whole genome sequence analysis of terbinafine resistant and susceptible Trichophyton isolates from human and animal origin. Mycopathologia. 2025;190:13.

- Lockhart SR, Chowdhary A, Gold JA. The rapid emergence of antifungal-resistant human-pathogenic fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:818-832.

- Mosam A, Shuping L, Naicker S, et al. A case of antifungal-resistant ringworm infection in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, caused by Trichophyton indotineae. Public Health Bulletin South Africa. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.phbsa.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/12PHBSA-Ringworm-Article-2023.pdf

- Cañete-Gibas CF, Mele J, Patterson HP, et al. Terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes and the presence of Trichophyton indotineae in North America. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61:E0056223

- Caplan AS, Todd GC, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical course, antifungal susceptibility, and genomic sequencing of Trichophyton indotineae. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:701-709. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1126

- Benedict K. Topical antifungal prescribing for Medicare Part D beneficiaries—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:1-5.

- Verma SB. Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:718-719.

- Khurana A, Sharath S, Sardana K, et al. Clinico-mycological and therapeutic updates on cutaneous dermatophytic infections in the era of Trichophyton indotineae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:315-323. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.024

- Verma S. Steroid modified tinea. BMJ. 2017;356:j973.

- Khurana A, Agarwal A, Agrawal D, et al. Effect of different itraconazole dosing regimens on cure rates, treatment duration, safety, and relapse rates in adult patients with tinea corporis/cruris: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1269-1278.

- Burmester A, Hipler UC, Uhrlaß S, et al. Indian Trichophyton mentagrophytes squalene epoxidase erg1 double mutants show high proportion of combined fluconazole and terbinafine resistance. Mycoses. 2020;63:1175-1180.

- Bhuiyan MSI, Verma SB, Illigner GM, et al. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VIII/Trichophyton indotineae infection and antifungal resistance in Bangladesh. J Fungi (Basel). 2024;10:768. doi:10.3390 /jof10110768

- Hay RJ. Chapter 82: superficial mycoses. In: Ryan ET, Hill DR, Solomon T, et al, eds. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2020:648-652.

- Gupta AK, Cooper EA, Wang T, et al. Detection of squalene epoxidase mutations in United States patients with onychomycosis: implications for management. J Invest Dermatol. 2023;143:2476-2483.E2477.

- Hwang JK, Bakotic WL, Gold JA, et al. Isolation of terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton rubrum from onychomycosis patients who failed treatment at an academic center in New York, United States. J Fungi. 2023;9:710.

- Gu D, Hatch M, Ghannoum M, et al. Treatment-resistant dermatophytosis: a representative case highlighting an emerging public health threat. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:1153-1155.

- Jabet A, Dellière S, Seang S, et al. Sexually transmitted Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII infection among men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1411-1414.

- Zucker J, Caplan AS, Gunaratne SH, et al. Notes from the field: Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII—New York City, April-July 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:985-988.

- Jabet A, Bérot V, Chiarabini T, et al. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VII infections among men who have sex with men in France: an ongoing phenomenon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:407-415.

- Caplan AS, Gold JA, Smith DJ, et al. Improving antifungal stewardship in dermatology in an era of emerging dermatophyte resistance. JAAD International. 2024;15:168-169.

- Elewski B. A call for antifungal stewardship. Br J Dermatol. 2020; 183:798-799.

- Gold JAW, Benedict K, Caplan AS, et al. High rates of potentially unnecessary topical antifungal prescribing in a large commercial health insurance claims database, United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025:S0190-9622(25)00098-2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.01.022

- Yadgar RJ, Bhatia N, Friedman A. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly misdiagnosed: a survey-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:562-563.

- Flint ND, Rhoads JLW, Carlisle R, et al. The continued inappropriate use and overuse of combination topical clotrimazole-betamethasone. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327854686

- Currie DW, Caplan AS, Benedict K, et al. Prescribing of clotrimazolebetamethasone dipropionate, a topical combination corticosteroidantifungal product, for Medicare part D beneficiaries, United States, 2016–2022. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2024;4:E174.

- Gold JA, Caplan AS, Benedict K, et al. Clotrimazole-betamethasone dipropionate prescribing for nonfungal skin conditions. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7:E2411721-E2411721.

- Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174, 177-168.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Uhrlaß S, Verma SB, Gräser Y, et al. Trichophyton indotineae—an emerging pathogen causing recalcitrant dermatophytoses in India and worldwide—a multidimensional perspective. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:757. doi:10.3390/jof8070757

- Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: I. epidemiology, risk factors and clinical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:154-175.

- Chen E, Ghannoum M, Elewski BE. Treatment]resistant tinea corporis, a potential public health issue. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:164-165.

- Caplan AS. Notes from the field: first reported US cases of tinea caused by Trichophyton indotineae—New York City, December 2021–March 2023. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2023;72:536-537. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7219a4

- Spivack S, Gold JA, Lockhart SR, et al. Potential sexual transmission of antifungal-resistant Trichophyton indotineae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30:807.

- Jabet A, Brun S, Normand AC, et al. Extensive dermatophytosis caused by terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:229-233.

- Thakur S, Spruijtenburg B, Abhishek, et al. Whole genome sequence analysis of terbinafine resistant and susceptible Trichophyton isolates from human and animal origin. Mycopathologia. 2025;190:13.

- Lockhart SR, Chowdhary A, Gold JA. The rapid emergence of antifungal-resistant human-pathogenic fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:818-832.

- Mosam A, Shuping L, Naicker S, et al. A case of antifungal-resistant ringworm infection in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, caused by Trichophyton indotineae. Public Health Bulletin South Africa. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.phbsa.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/12PHBSA-Ringworm-Article-2023.pdf

- Cañete-Gibas CF, Mele J, Patterson HP, et al. Terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes and the presence of Trichophyton indotineae in North America. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61:E0056223

- Caplan AS, Todd GC, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical course, antifungal susceptibility, and genomic sequencing of Trichophyton indotineae. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:701-709. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1126

- Benedict K. Topical antifungal prescribing for Medicare Part D beneficiaries—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:1-5.

- Verma SB. Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:718-719.

- Khurana A, Sharath S, Sardana K, et al. Clinico-mycological and therapeutic updates on cutaneous dermatophytic infections in the era of Trichophyton indotineae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:315-323. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.024

- Verma S. Steroid modified tinea. BMJ. 2017;356:j973.

- Khurana A, Agarwal A, Agrawal D, et al. Effect of different itraconazole dosing regimens on cure rates, treatment duration, safety, and relapse rates in adult patients with tinea corporis/cruris: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1269-1278.

- Burmester A, Hipler UC, Uhrlaß S, et al. Indian Trichophyton mentagrophytes squalene epoxidase erg1 double mutants show high proportion of combined fluconazole and terbinafine resistance. Mycoses. 2020;63:1175-1180.

- Bhuiyan MSI, Verma SB, Illigner GM, et al. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VIII/Trichophyton indotineae infection and antifungal resistance in Bangladesh. J Fungi (Basel). 2024;10:768. doi:10.3390 /jof10110768

- Hay RJ. Chapter 82: superficial mycoses. In: Ryan ET, Hill DR, Solomon T, et al, eds. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2020:648-652.

- Gupta AK, Cooper EA, Wang T, et al. Detection of squalene epoxidase mutations in United States patients with onychomycosis: implications for management. J Invest Dermatol. 2023;143:2476-2483.E2477.

- Hwang JK, Bakotic WL, Gold JA, et al. Isolation of terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton rubrum from onychomycosis patients who failed treatment at an academic center in New York, United States. J Fungi. 2023;9:710.

- Gu D, Hatch M, Ghannoum M, et al. Treatment-resistant dermatophytosis: a representative case highlighting an emerging public health threat. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:1153-1155.

- Jabet A, Dellière S, Seang S, et al. Sexually transmitted Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII infection among men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1411-1414.

- Zucker J, Caplan AS, Gunaratne SH, et al. Notes from the field: Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VII—New York City, April-July 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:985-988.

- Jabet A, Bérot V, Chiarabini T, et al. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VII infections among men who have sex with men in France: an ongoing phenomenon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:407-415.

- Caplan AS, Gold JA, Smith DJ, et al. Improving antifungal stewardship in dermatology in an era of emerging dermatophyte resistance. JAAD International. 2024;15:168-169.

- Elewski B. A call for antifungal stewardship. Br J Dermatol. 2020; 183:798-799.

- Gold JAW, Benedict K, Caplan AS, et al. High rates of potentially unnecessary topical antifungal prescribing in a large commercial health insurance claims database, United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025:S0190-9622(25)00098-2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.01.022

- Yadgar RJ, Bhatia N, Friedman A. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly misdiagnosed: a survey-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:562-563.

- Flint ND, Rhoads JLW, Carlisle R, et al. The continued inappropriate use and overuse of combination topical clotrimazole-betamethasone. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327854686

- Currie DW, Caplan AS, Benedict K, et al. Prescribing of clotrimazolebetamethasone dipropionate, a topical combination corticosteroidantifungal product, for Medicare part D beneficiaries, United States, 2016–2022. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2024;4:E174.

- Gold JA, Caplan AS, Benedict K, et al. Clotrimazole-betamethasone dipropionate prescribing for nonfungal skin conditions. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7:E2411721-E2411721.

The Rise of Antifungal-Resistant Dermatophyte Infections: What Dermatologists Need to Know

The Rise of Antifungal-Resistant Dermatophyte Infections: What Dermatologists Need to Know

PRACTICE POINTS

- Recently emerged dermatophyte species pose a global public health concern because of infection severity, frequent resistance to terbinafine, and easy person-to-person transmission.

- Prolonged itraconazole therapy is considered the firstline treatment for infections caused by Trichophyton indotineae, a globally emerging and frequently terbinafine-resistant dermatophyte.

- Dermatologists can educate nondermatologists on the importance of mycologic confirmation and avoidance of the use of topical antifungal/ corticosteroid products, which are hypothesized to contribute to emergence and spread of resistance.

Implications of Thyroid Disease in Hospitalized Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Implications of Thyroid Disease in Hospitalized Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

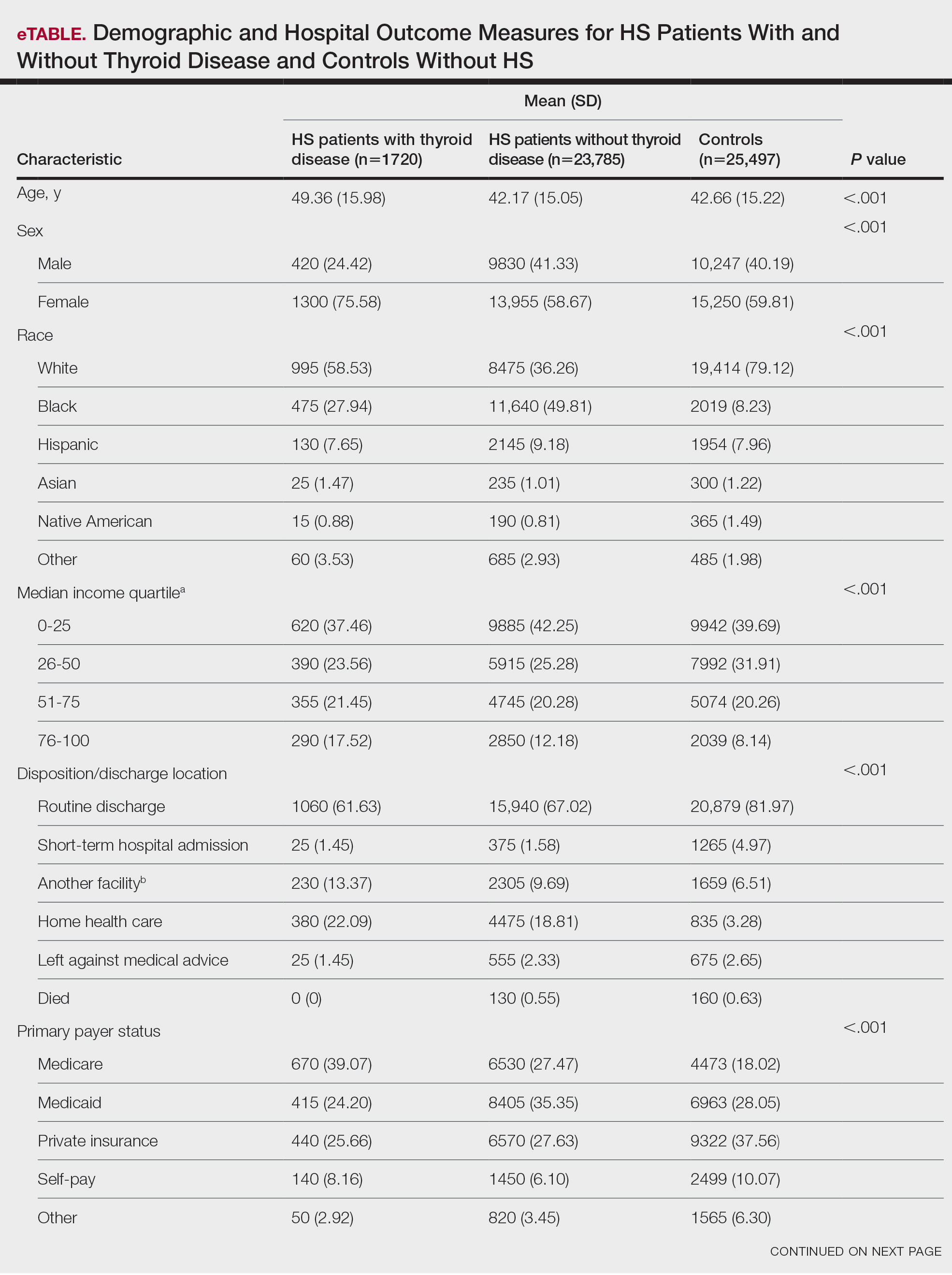

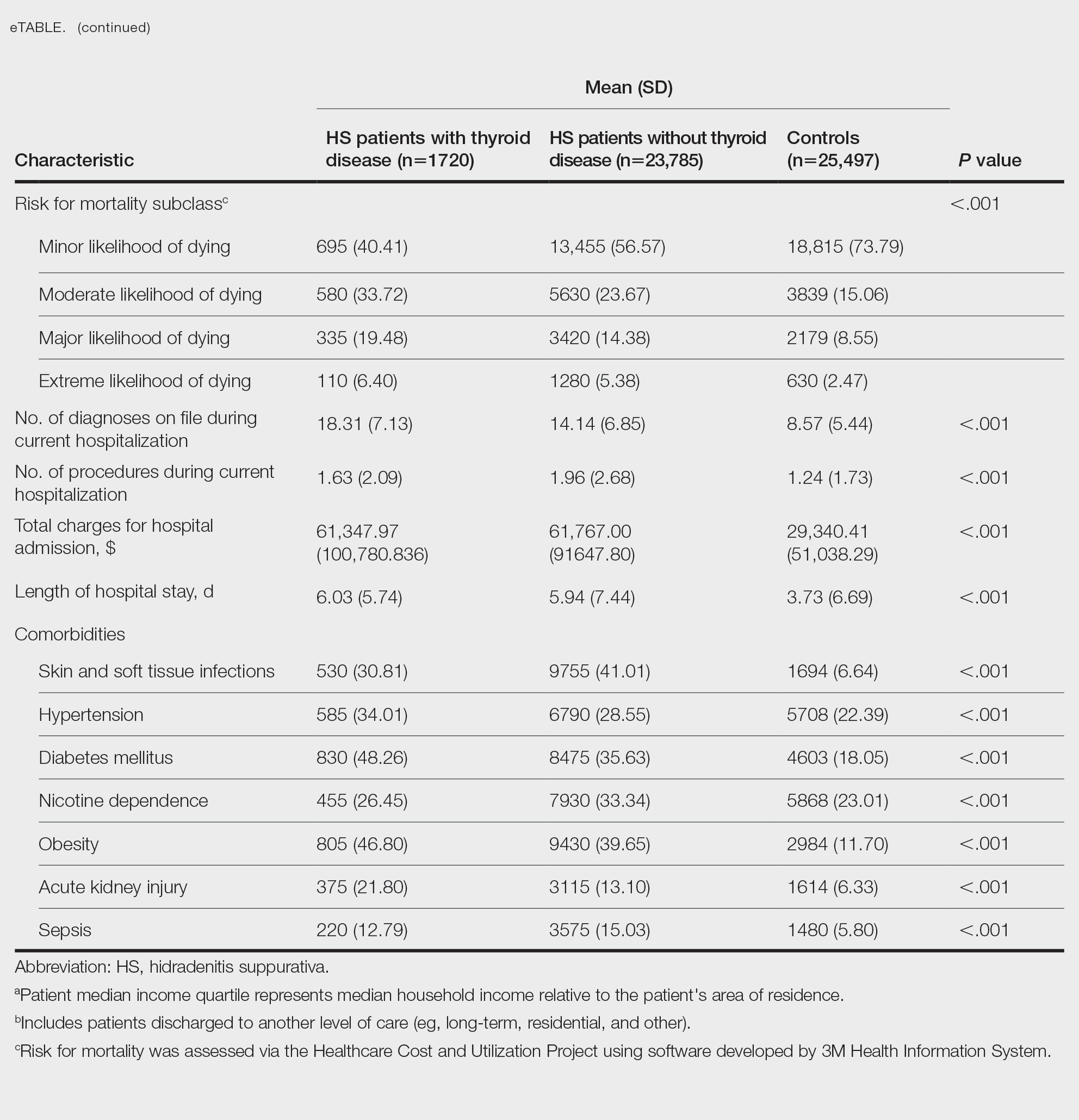

To the Editor: