User login

Richard Franki is the associate editor who writes and creates graphs. He started with the company in 1987, when it was known as the International Medical News Group. In his years as a journalist, Richard has worked for Cap Cities/ABC, Disney, Harcourt, Elsevier, Quadrant, Frontline, and Internet Brands. In the 1990s, he was a contributor to the ill-fated Indications column, predecessor of Livin' on the MDedge.

2020 left many GIs unhappy in life outside work

A year ago, 81% of gastroenterologists were happy outside of work. Not anymore.

In these COVID-19–pandemic times, that number is down to 54%, according to a survey of more than 12,000 physicians in 29 specialties that was conducted by Medscape.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval of Medscape wrote in the Gastroenterologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the proportion of GIs who say that they’re burned out or are both burned out and depressed now is only a little higher (40%) than in last year’s survey (36%). It’s also just under this year’s burnout rate of 42% for all physicians, which has not changed since last year.

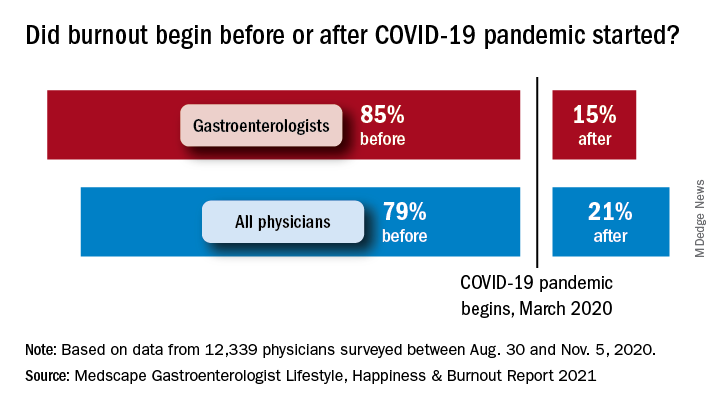

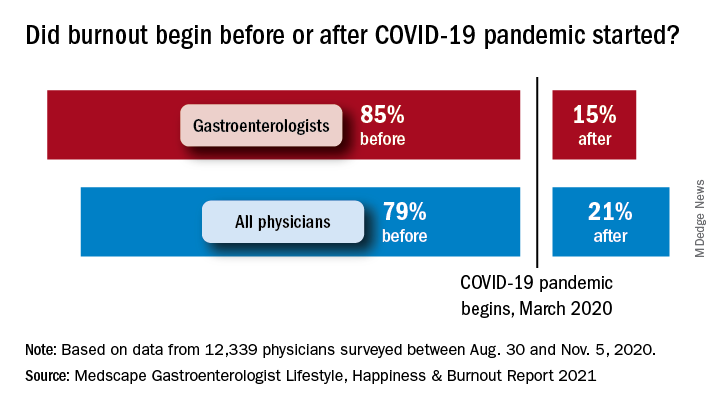

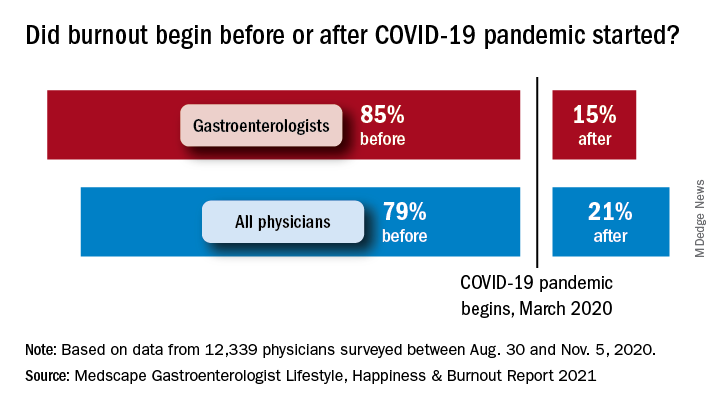

COVID-19 may have had some effect on burnout, though. Among the gastroenterologists with burnout, 15% said it began after the pandemic started, which was, again, less than physicians overall, who had a distribution of 79% before and 21% after. The GIs were slightly less likely to report that their burnout had a severe impact on their everyday lives than physicians overall – 44% versus 47% – but more likely to say that it was bad enough to consider leaving medicine – 15% versus 10%.

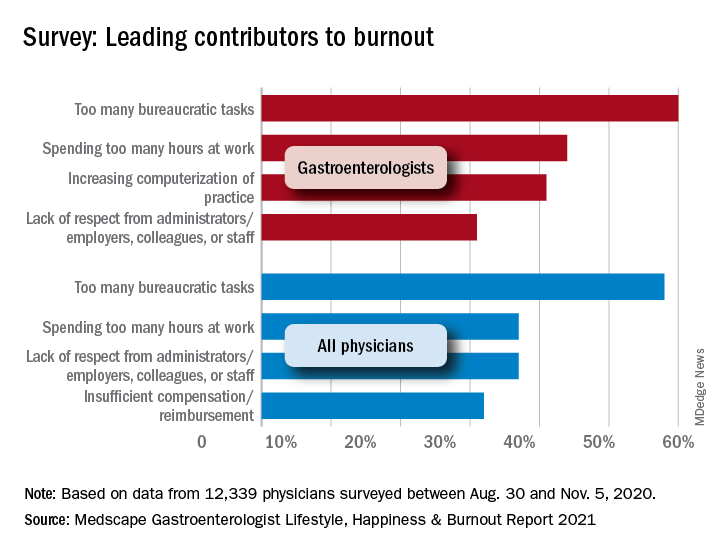

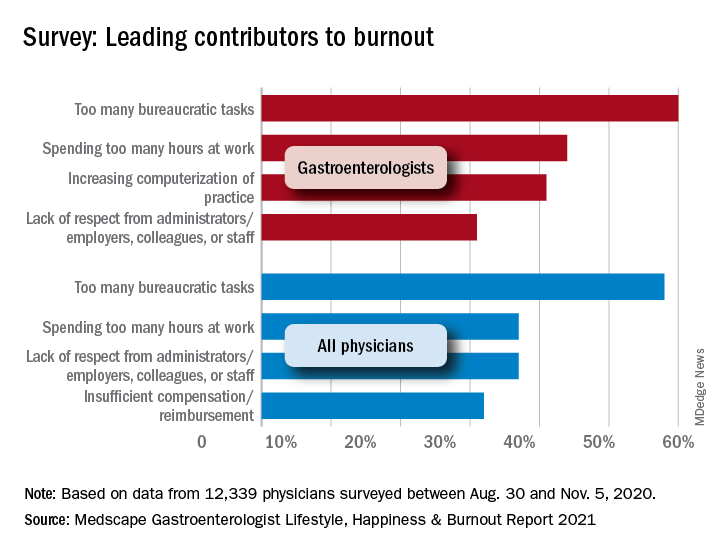

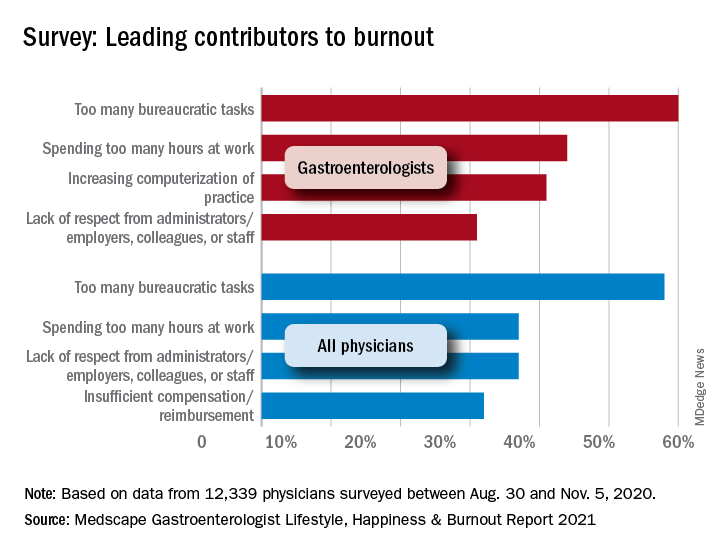

“The chief causes of burnout remain consistent from past years and are pushing physicians to the breaking point,” the Medscape report noted, citing one physician who called it “death by 1,000 cuts.” The biggest contributor to burnout over this past year was, for 60% of gastroenterologists, the excessive number of bureaucratic tasks, followed by spending too much time at work (44%) and increasing computerization (41%).

The two pandemic-related contributors included in the survey were near the bottom of the list for gastroenterologists: stress from social distancing/societal issues (15%) and stress related to treating COVID-19 patients (8%), based on data for the 12,339 physicians – of whom about 2% were GIs – polled from Aug. 30 to Nov. 5, 2020.

To deal with their burnout, many gastroenterologists are exercising – at least 51% of them, anyway. Other popular coping mechanisms include talking with family members and close friends (39%), playing or listening to music (38%), isolating themselves from others (36%), and sleeping (26%). For all physicians, the top choices were exercise (48%), talking with family members/friends (43%), and isolation (43%).

When the subject of professional help was raised, a large majority (84%) of GIs planned to forgo such care. That information was not available for physicians as a group, but 70% of internists agreed, as did 83% of nephrologists, 80% of cardiologists, 80% of oncologists, 89% of urologists, and 80% of general surgeons.

A majority of gastroenterologists (58%) said that their symptoms weren’t severe enough to warrant such help, but 38% said they were too busy, and 11% didn’t want to risk disclosure. Some physicians commented on their own situations:

- “I have no energy when I get home and I feel like I’m ignoring my family, but I need to decompress and process what I dealt with during the day” (oncologist).

- “I can’t do the things that I enjoy to relieve stress, such as traveling. My hair is falling out because I can’t destress” (ob.gyn.).

- “I’m tired and discouraged. It stresses my marriage. I have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. I count the days until Friday” (psychiatrist).

A year ago, 81% of gastroenterologists were happy outside of work. Not anymore.

In these COVID-19–pandemic times, that number is down to 54%, according to a survey of more than 12,000 physicians in 29 specialties that was conducted by Medscape.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval of Medscape wrote in the Gastroenterologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the proportion of GIs who say that they’re burned out or are both burned out and depressed now is only a little higher (40%) than in last year’s survey (36%). It’s also just under this year’s burnout rate of 42% for all physicians, which has not changed since last year.

COVID-19 may have had some effect on burnout, though. Among the gastroenterologists with burnout, 15% said it began after the pandemic started, which was, again, less than physicians overall, who had a distribution of 79% before and 21% after. The GIs were slightly less likely to report that their burnout had a severe impact on their everyday lives than physicians overall – 44% versus 47% – but more likely to say that it was bad enough to consider leaving medicine – 15% versus 10%.

“The chief causes of burnout remain consistent from past years and are pushing physicians to the breaking point,” the Medscape report noted, citing one physician who called it “death by 1,000 cuts.” The biggest contributor to burnout over this past year was, for 60% of gastroenterologists, the excessive number of bureaucratic tasks, followed by spending too much time at work (44%) and increasing computerization (41%).

The two pandemic-related contributors included in the survey were near the bottom of the list for gastroenterologists: stress from social distancing/societal issues (15%) and stress related to treating COVID-19 patients (8%), based on data for the 12,339 physicians – of whom about 2% were GIs – polled from Aug. 30 to Nov. 5, 2020.

To deal with their burnout, many gastroenterologists are exercising – at least 51% of them, anyway. Other popular coping mechanisms include talking with family members and close friends (39%), playing or listening to music (38%), isolating themselves from others (36%), and sleeping (26%). For all physicians, the top choices were exercise (48%), talking with family members/friends (43%), and isolation (43%).

When the subject of professional help was raised, a large majority (84%) of GIs planned to forgo such care. That information was not available for physicians as a group, but 70% of internists agreed, as did 83% of nephrologists, 80% of cardiologists, 80% of oncologists, 89% of urologists, and 80% of general surgeons.

A majority of gastroenterologists (58%) said that their symptoms weren’t severe enough to warrant such help, but 38% said they were too busy, and 11% didn’t want to risk disclosure. Some physicians commented on their own situations:

- “I have no energy when I get home and I feel like I’m ignoring my family, but I need to decompress and process what I dealt with during the day” (oncologist).

- “I can’t do the things that I enjoy to relieve stress, such as traveling. My hair is falling out because I can’t destress” (ob.gyn.).

- “I’m tired and discouraged. It stresses my marriage. I have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. I count the days until Friday” (psychiatrist).

A year ago, 81% of gastroenterologists were happy outside of work. Not anymore.

In these COVID-19–pandemic times, that number is down to 54%, according to a survey of more than 12,000 physicians in 29 specialties that was conducted by Medscape.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval of Medscape wrote in the Gastroenterologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the proportion of GIs who say that they’re burned out or are both burned out and depressed now is only a little higher (40%) than in last year’s survey (36%). It’s also just under this year’s burnout rate of 42% for all physicians, which has not changed since last year.

COVID-19 may have had some effect on burnout, though. Among the gastroenterologists with burnout, 15% said it began after the pandemic started, which was, again, less than physicians overall, who had a distribution of 79% before and 21% after. The GIs were slightly less likely to report that their burnout had a severe impact on their everyday lives than physicians overall – 44% versus 47% – but more likely to say that it was bad enough to consider leaving medicine – 15% versus 10%.

“The chief causes of burnout remain consistent from past years and are pushing physicians to the breaking point,” the Medscape report noted, citing one physician who called it “death by 1,000 cuts.” The biggest contributor to burnout over this past year was, for 60% of gastroenterologists, the excessive number of bureaucratic tasks, followed by spending too much time at work (44%) and increasing computerization (41%).

The two pandemic-related contributors included in the survey were near the bottom of the list for gastroenterologists: stress from social distancing/societal issues (15%) and stress related to treating COVID-19 patients (8%), based on data for the 12,339 physicians – of whom about 2% were GIs – polled from Aug. 30 to Nov. 5, 2020.

To deal with their burnout, many gastroenterologists are exercising – at least 51% of them, anyway. Other popular coping mechanisms include talking with family members and close friends (39%), playing or listening to music (38%), isolating themselves from others (36%), and sleeping (26%). For all physicians, the top choices were exercise (48%), talking with family members/friends (43%), and isolation (43%).

When the subject of professional help was raised, a large majority (84%) of GIs planned to forgo such care. That information was not available for physicians as a group, but 70% of internists agreed, as did 83% of nephrologists, 80% of cardiologists, 80% of oncologists, 89% of urologists, and 80% of general surgeons.

A majority of gastroenterologists (58%) said that their symptoms weren’t severe enough to warrant such help, but 38% said they were too busy, and 11% didn’t want to risk disclosure. Some physicians commented on their own situations:

- “I have no energy when I get home and I feel like I’m ignoring my family, but I need to decompress and process what I dealt with during the day” (oncologist).

- “I can’t do the things that I enjoy to relieve stress, such as traveling. My hair is falling out because I can’t destress” (ob.gyn.).

- “I’m tired and discouraged. It stresses my marriage. I have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. I count the days until Friday” (psychiatrist).

New cases of child COVID-19 drop for fifth straight week

The fifth consecutive week with a decline has the number of new COVID-19 cases in children at its lowest level since late October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when 61,000 cases were reported, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children is now just over 3.1 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all ages in the United States, based on data gathered from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

More children in California (439,000) have been infected than in any other state, while Illinois (176,000), Florida (145,000), Tennessee (137,000), Arizona (127,000), Ohio (121,000), and Pennsylvania (111,000) are the only other states with more than 100,000 cases, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Proportionally, the children of Wyoming have been hardest hit: Pediatric cases represent 19.4% of all cases in the state. The other four states with proportions of 18% or more are Alaska, Vermont, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Cumulative rates, however, tell a somewhat different story, as North Dakota leads with just over 8,500 cases per 100,000 children, followed by Tennessee (7,700 per 100,000) and Rhode Island (7,000 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children, which had not been following the trend of fewer new cases over the last few weeks, dropped below double digits for the first time in a month. The six deaths that occurred during the week of Feb. 12-18 bring the total to 247 since the start of the pandemic in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, according to the report.

The fifth consecutive week with a decline has the number of new COVID-19 cases in children at its lowest level since late October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when 61,000 cases were reported, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children is now just over 3.1 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all ages in the United States, based on data gathered from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

More children in California (439,000) have been infected than in any other state, while Illinois (176,000), Florida (145,000), Tennessee (137,000), Arizona (127,000), Ohio (121,000), and Pennsylvania (111,000) are the only other states with more than 100,000 cases, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Proportionally, the children of Wyoming have been hardest hit: Pediatric cases represent 19.4% of all cases in the state. The other four states with proportions of 18% or more are Alaska, Vermont, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Cumulative rates, however, tell a somewhat different story, as North Dakota leads with just over 8,500 cases per 100,000 children, followed by Tennessee (7,700 per 100,000) and Rhode Island (7,000 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children, which had not been following the trend of fewer new cases over the last few weeks, dropped below double digits for the first time in a month. The six deaths that occurred during the week of Feb. 12-18 bring the total to 247 since the start of the pandemic in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, according to the report.

The fifth consecutive week with a decline has the number of new COVID-19 cases in children at its lowest level since late October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when 61,000 cases were reported, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children is now just over 3.1 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all ages in the United States, based on data gathered from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

More children in California (439,000) have been infected than in any other state, while Illinois (176,000), Florida (145,000), Tennessee (137,000), Arizona (127,000), Ohio (121,000), and Pennsylvania (111,000) are the only other states with more than 100,000 cases, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Proportionally, the children of Wyoming have been hardest hit: Pediatric cases represent 19.4% of all cases in the state. The other four states with proportions of 18% or more are Alaska, Vermont, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Cumulative rates, however, tell a somewhat different story, as North Dakota leads with just over 8,500 cases per 100,000 children, followed by Tennessee (7,700 per 100,000) and Rhode Island (7,000 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children, which had not been following the trend of fewer new cases over the last few weeks, dropped below double digits for the first time in a month. The six deaths that occurred during the week of Feb. 12-18 bring the total to 247 since the start of the pandemic in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, according to the report.

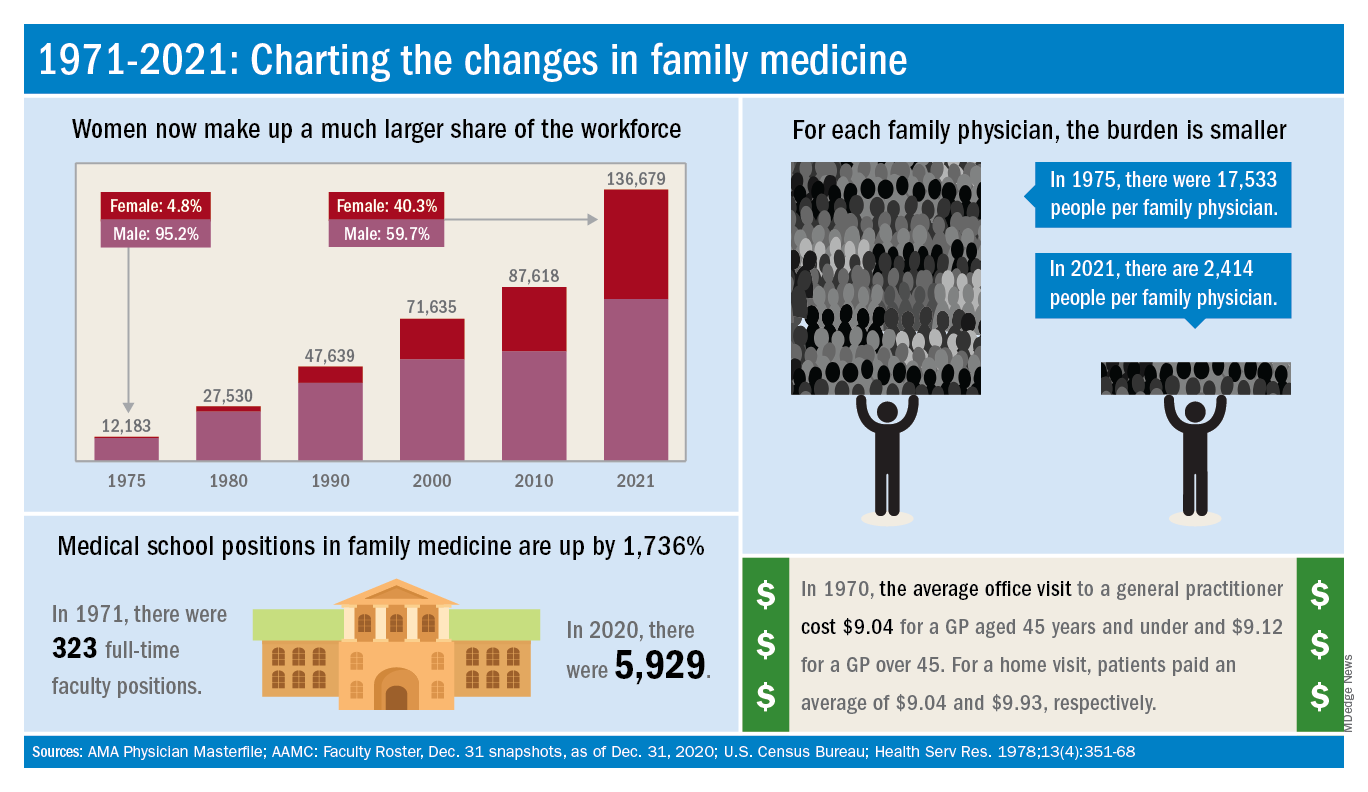

Family medicine has grown; its composition has evolved

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

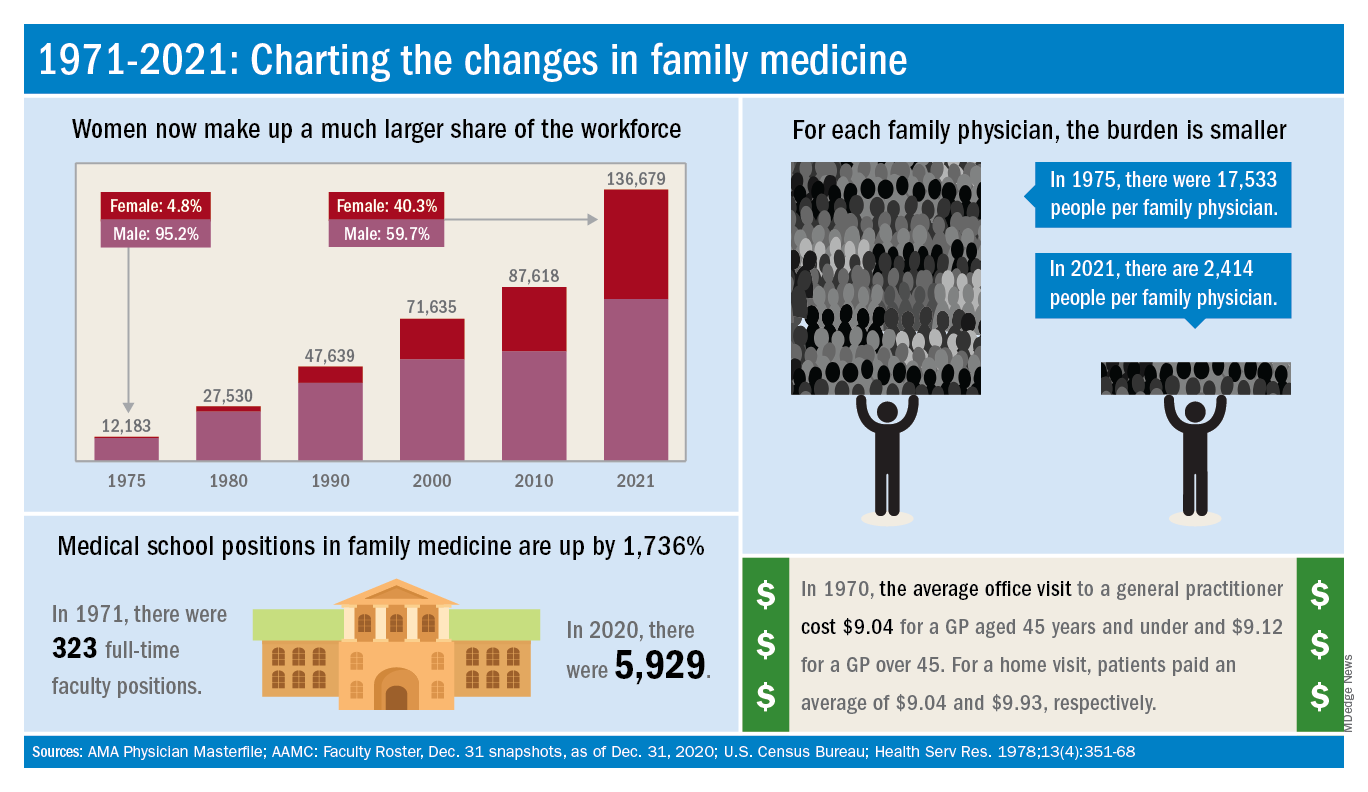

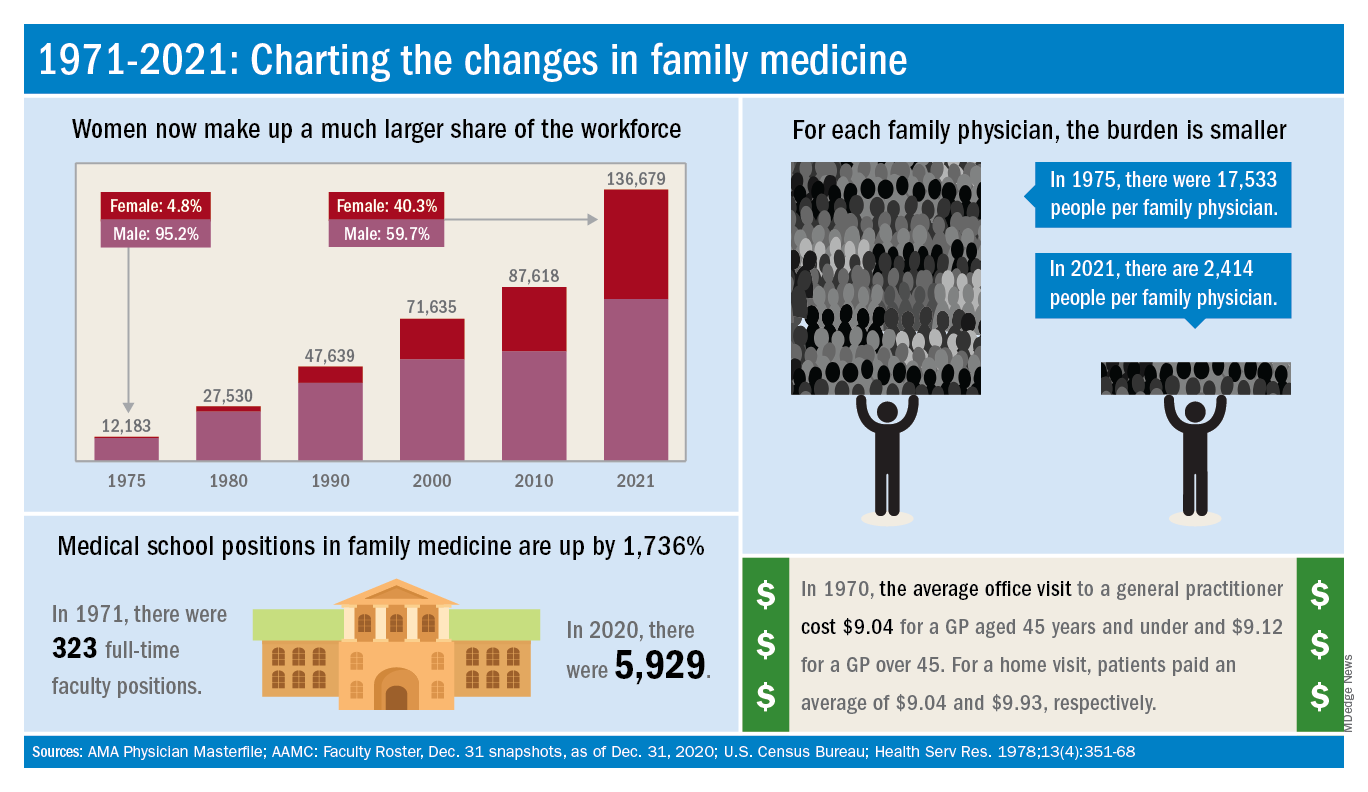

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

and the men and women who practice it are no exception.

The family medicine workforce of 2021 is not the workforce of 1971. Not even close. Although we would like to give a huge shout-out to anyone who can claim to be a member of both.

Today’s FP workforce is, first of all, much larger than it was in 1971, although we can’t actually prove it because the American Medical Association’s data for that year are “only available in books that are locked away at the empty AMA headquarters,” according to a member of the AMA media relations staff who is, like so many people these days, working at home because of the pandemic.

The face of family medicine in 1975 vs. today

Today’s workforce is much larger than it was in 1975, when there were just over 12,000 family physicians in the United States. As of January 2021, the total was approaching 137,000, including all “physicians and residents in patient care, research, administration, teaching, retired, inactive, etc.,” the AMA explained.

Family physicians as a group are much more diverse than they were in 1975. That year, 8.3% of FPs were international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2010, IMGs made up almost 23% of the workforce, and in the 2020 resident match, 37% of the 4,662 available family medicine slots were filled by IMGs.

Women have made even greater inroads into the family physician ranks over the last 5 decades. In 1975, less than 5% of all FPs were females, but by 2021 the proportion of females in the specialty was just over 40%.

In the first 5 years of the family practice era, 1969-1973, only 12 women and 31 IMGs graduated from FP residency programs, those numbers representing 3.2% and 8.3%, respectively, of the total of 372, according to a 1996 study in JAMA. By 1990-1993, women made up 33% and IMGs 14% of the 9,400 graduates.

Another group that increased its presence in family medicine is doctors of osteopathy, who went from zero residency graduates in 1969-1973 to over 1,100 (11.8%) in 1990-1993, the JAMA report noted. By 2020, almost 1,400 osteopathic physicians entered family medicine residencies, filling 30% of all slots available, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

The medical schools producing all these new residents have raised their games since 1971: the number of full-time faculty in family medicine departments rose from 323 to 5,929 in 2020, based on data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (Faculty Roster, Dec. 31 snapshots, as of Dec. 31, 2020).

A shortage or a surplus of FPs?

It has been suggested, however, that all is not well in primary care land. A study conducted by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2016 – a year after 2,463 graduates of MD- and DO-granting medical schools entered family medicine residencies – concluded “that the current medical school system is failing, collectively, to produce the primary care workforce that is needed to achieve optimal health.”

Warnings about physician shortages are nothing new, but how about the other side of the coin? The Jan. 15, 1981, issue of Family Practice News covered a somewhat controversial report from the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee, which projected a surplus of 3,000 FPs, and as many as 70,000 physicians overall, by the year 1990.

Just a few months later, in the June 15, 1981, issue of FPN, an AAFP officer predicted that “the flood of new physicians in the next decade may affect family practice more than any other specialty.”

Mostly, though, the issue is shortages. In 2002, a status report on family practice from the Robert Graham Center acknowledged that “many centers of academic medicine continue to resist the development of family practice and primary care. ... Family medicine remains a true counterculture in these environments, and students may continue to face significant discouragement in response to interest they may express in becoming a family physician.”

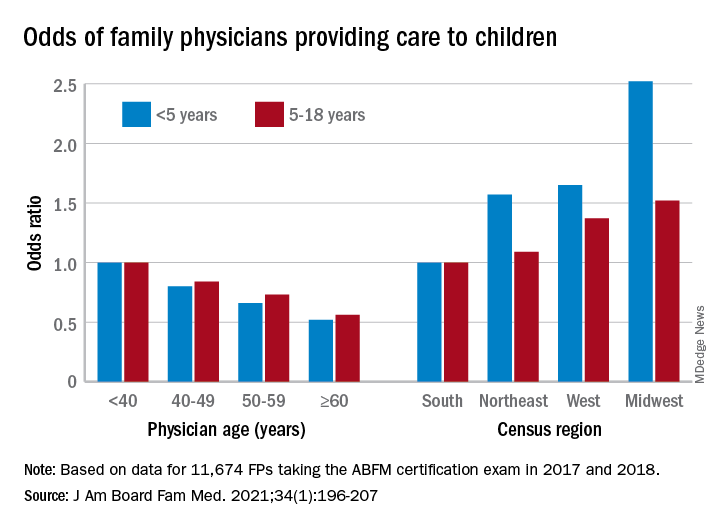

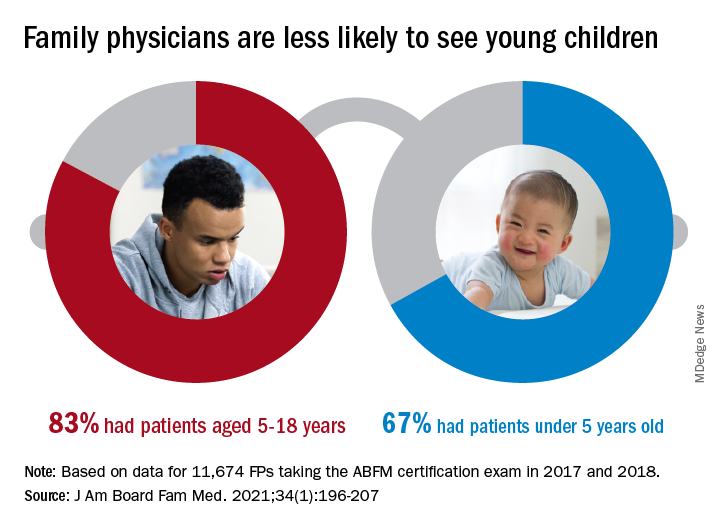

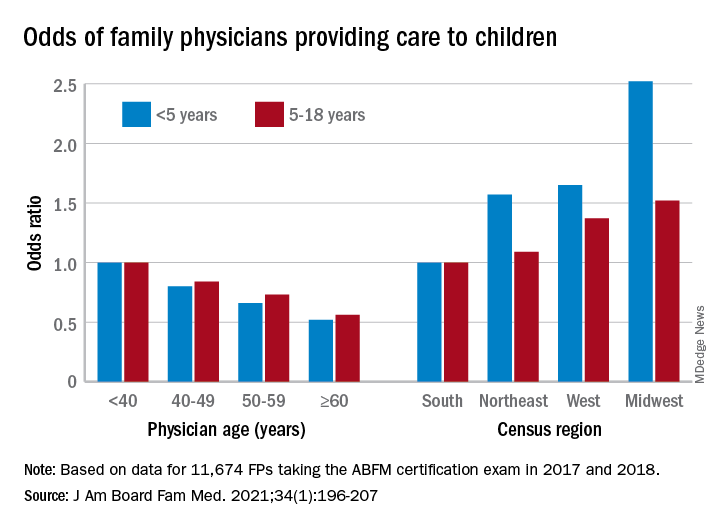

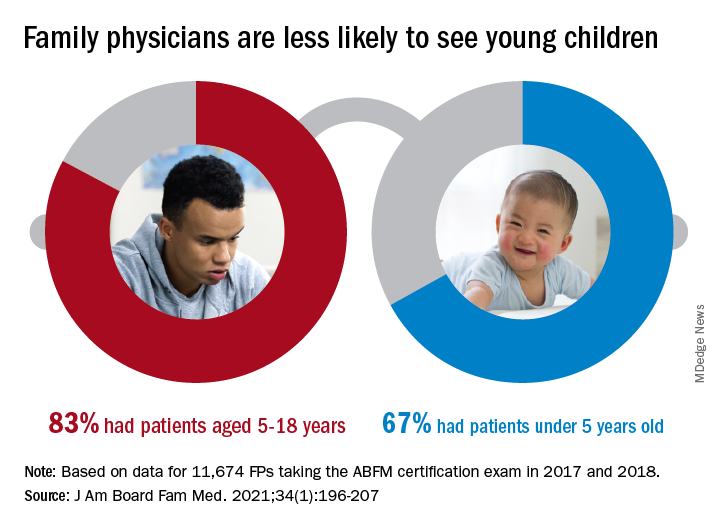

Family medicine: Who cares for the children?

according to new research.

This the latest sign of a long-term decline, and it “poses a broader concern for a specialty that defines itself by its comprehensive scope of practice,” said the study investigators of the Robert Graham Center in Washington, D.C., in a written statement. “This is consistent with previous Robert Graham Center research that reported a similar steady decline from 1992 to 2002.”

Self-reported data from family physicians indicate that 84.3% cared for children aged 18 years and under in 2017, compared with 83.0% in 2018, based on a cross-sectional analysis of data gathered from 11,674 family physicians who completed the practice demographic questionnaire attached to the American Board of Family Medicine’s certification exam in 2017 and 2018.

“This current trend is unsettling, because family physicians provide the majority of pediatric care in rural and pediatrically underserved areas of the United States,” study author Anuradha Jetty, MPH, and coauthors said in the statement.

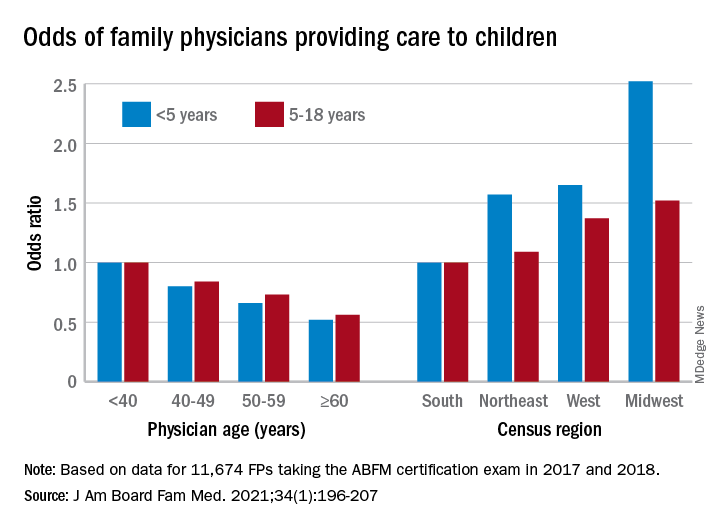

The analysis also offers a snapshot of the current state of pediatric care offered by family physicians. In 2017 and 2018, FPs were more likely to see patients aged 5-18 years than those under age 5 (83.0% vs. 67.0%), with variation by age, location, and race/ethnicity, said Ms. Jetty and colleagues, in their new paper.

FPs aged 60 years and older were much less likely to see pediatric patients, compared with those under age 40: odds ratios were 0.52 for children under 5 and 0.56 for children 5-18. Regional variation was even more pronounced: Compared with their colleagues in the Southern states, Midwestern FPs were 1.52 times as likely to treat children aged 5-18 and 2.52 times as likely to treat children under age 5, the investigators reported.

Non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic family physicians had significantly lower odds of seeing pediatric patients, relative to non-Hispanic White family physicians, as did FPs who were international medical graduates (OR, 0.74), compared with those who trained in the United States, they said.

“Female gender was associated with seeing pediatric patients in a prior study using 2006-2009 [American Board of Family Medicine] data; however, we found no such association in 2017-2018,” Ms. Jetty and associates noted.

“Many diverse drivers likely influence the findings we observed, including organizational, personal, social, and economic factors,” they wrote, suggesting that the policies of some HMOs “may limit scope of practice for employed physicians,” while those who practice in areas of low pediatrician density might “capitalize on a market opportunity ... more than physicians in pediatrician-saturated areas with greater competition for young patients.”

The overall shortage of primary pediatric care may be a matter of debate, the investigators said, but “there is undoubtedly significant variability in the regional supply of pediatric primary care physicians and thus areas where family physicians are needed to meet current pediatric workforce demand.”

The authors reported no conflicts.

according to new research.

This the latest sign of a long-term decline, and it “poses a broader concern for a specialty that defines itself by its comprehensive scope of practice,” said the study investigators of the Robert Graham Center in Washington, D.C., in a written statement. “This is consistent with previous Robert Graham Center research that reported a similar steady decline from 1992 to 2002.”

Self-reported data from family physicians indicate that 84.3% cared for children aged 18 years and under in 2017, compared with 83.0% in 2018, based on a cross-sectional analysis of data gathered from 11,674 family physicians who completed the practice demographic questionnaire attached to the American Board of Family Medicine’s certification exam in 2017 and 2018.

“This current trend is unsettling, because family physicians provide the majority of pediatric care in rural and pediatrically underserved areas of the United States,” study author Anuradha Jetty, MPH, and coauthors said in the statement.

The analysis also offers a snapshot of the current state of pediatric care offered by family physicians. In 2017 and 2018, FPs were more likely to see patients aged 5-18 years than those under age 5 (83.0% vs. 67.0%), with variation by age, location, and race/ethnicity, said Ms. Jetty and colleagues, in their new paper.

FPs aged 60 years and older were much less likely to see pediatric patients, compared with those under age 40: odds ratios were 0.52 for children under 5 and 0.56 for children 5-18. Regional variation was even more pronounced: Compared with their colleagues in the Southern states, Midwestern FPs were 1.52 times as likely to treat children aged 5-18 and 2.52 times as likely to treat children under age 5, the investigators reported.

Non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic family physicians had significantly lower odds of seeing pediatric patients, relative to non-Hispanic White family physicians, as did FPs who were international medical graduates (OR, 0.74), compared with those who trained in the United States, they said.

“Female gender was associated with seeing pediatric patients in a prior study using 2006-2009 [American Board of Family Medicine] data; however, we found no such association in 2017-2018,” Ms. Jetty and associates noted.

“Many diverse drivers likely influence the findings we observed, including organizational, personal, social, and economic factors,” they wrote, suggesting that the policies of some HMOs “may limit scope of practice for employed physicians,” while those who practice in areas of low pediatrician density might “capitalize on a market opportunity ... more than physicians in pediatrician-saturated areas with greater competition for young patients.”

The overall shortage of primary pediatric care may be a matter of debate, the investigators said, but “there is undoubtedly significant variability in the regional supply of pediatric primary care physicians and thus areas where family physicians are needed to meet current pediatric workforce demand.”

The authors reported no conflicts.

according to new research.

This the latest sign of a long-term decline, and it “poses a broader concern for a specialty that defines itself by its comprehensive scope of practice,” said the study investigators of the Robert Graham Center in Washington, D.C., in a written statement. “This is consistent with previous Robert Graham Center research that reported a similar steady decline from 1992 to 2002.”

Self-reported data from family physicians indicate that 84.3% cared for children aged 18 years and under in 2017, compared with 83.0% in 2018, based on a cross-sectional analysis of data gathered from 11,674 family physicians who completed the practice demographic questionnaire attached to the American Board of Family Medicine’s certification exam in 2017 and 2018.

“This current trend is unsettling, because family physicians provide the majority of pediatric care in rural and pediatrically underserved areas of the United States,” study author Anuradha Jetty, MPH, and coauthors said in the statement.

The analysis also offers a snapshot of the current state of pediatric care offered by family physicians. In 2017 and 2018, FPs were more likely to see patients aged 5-18 years than those under age 5 (83.0% vs. 67.0%), with variation by age, location, and race/ethnicity, said Ms. Jetty and colleagues, in their new paper.

FPs aged 60 years and older were much less likely to see pediatric patients, compared with those under age 40: odds ratios were 0.52 for children under 5 and 0.56 for children 5-18. Regional variation was even more pronounced: Compared with their colleagues in the Southern states, Midwestern FPs were 1.52 times as likely to treat children aged 5-18 and 2.52 times as likely to treat children under age 5, the investigators reported.

Non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic family physicians had significantly lower odds of seeing pediatric patients, relative to non-Hispanic White family physicians, as did FPs who were international medical graduates (OR, 0.74), compared with those who trained in the United States, they said.

“Female gender was associated with seeing pediatric patients in a prior study using 2006-2009 [American Board of Family Medicine] data; however, we found no such association in 2017-2018,” Ms. Jetty and associates noted.

“Many diverse drivers likely influence the findings we observed, including organizational, personal, social, and economic factors,” they wrote, suggesting that the policies of some HMOs “may limit scope of practice for employed physicians,” while those who practice in areas of low pediatrician density might “capitalize on a market opportunity ... more than physicians in pediatrician-saturated areas with greater competition for young patients.”

The overall shortage of primary pediatric care may be a matter of debate, the investigators said, but “there is undoubtedly significant variability in the regional supply of pediatric primary care physicians and thus areas where family physicians are needed to meet current pediatric workforce demand.”

The authors reported no conflicts.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN BOARD OF FAMILY MEDICINE

New child COVID-19 cases decline as total passes 3 million

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

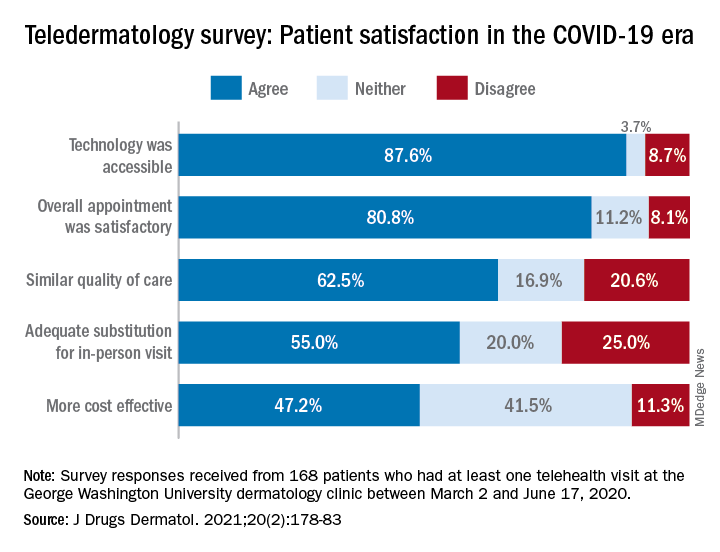

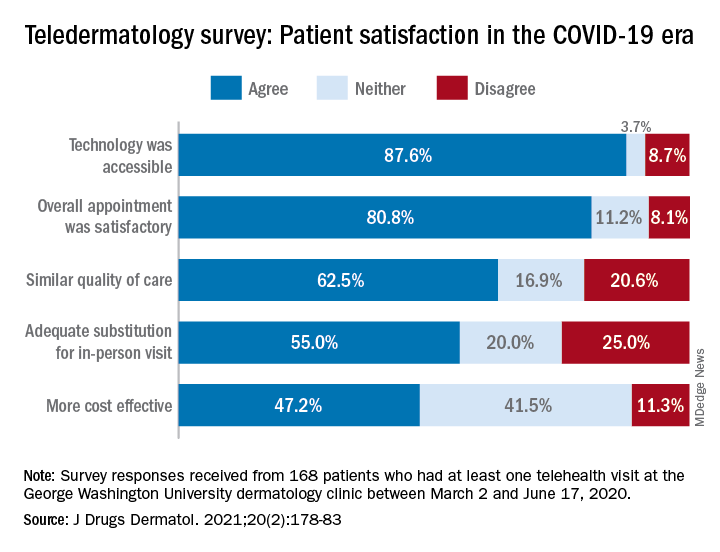

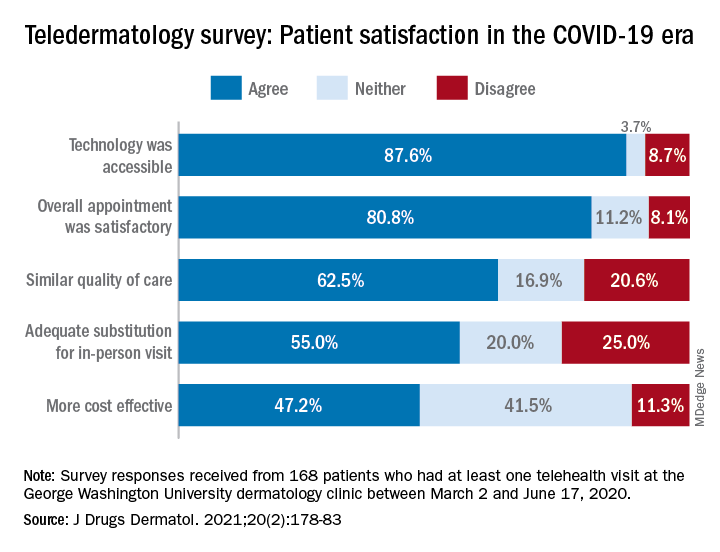

Survey: Most patients support teledermatology

Many medical practices turned to telemedicine when the pandemic shut down the economy last spring, but what do dermatology patients think about the socially distant approach?

and 80% said that they would consider another such visit in the future, according to a survey conducted at George Washington University in Washington.

Although “telehealth is not without its drawbacks … it is clear from this study that the majority of patients feel positively towards teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic and [believe it] can be a suitable alternative for patients who are unable to meet with their providers in person,” Samuel Yeroushalmi, Sarah H. Millan, and associates at the university said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

When presented with a set of statements about the telehealth experience, the 168 survey respondents largely agreed that the overall appointment was satisfactory (80.8%), that minimal barriers were present (78.1%), and that the quality of care was similar to an in-person visit (62.5%), the investigators said.

Other factors, however, were not as well supported. Less than half (47.2%) of the respondents agreed that the telehealth appointments were more cost effective, and just over half (54.7%) agreed that they provided an adequate skin exam, they reported.

Of the set of 14 statements given to the patients – all of whom had at least one telehealth visit with the GW clinic between March 2 and June 17, 2020 – the one on the adequacy of the skin exam provided the largest share of disagreement at 27.1%, Mr. Yeroushalmi and Ms. Millan, medical students at the university and coauthors.

The lack of physical touch was mentioned most often (26.8%) when respondents were asked about their reasons for disliking telehealth visits, followed by the feeling that they had received an inadequate assessment (15.7%), they said.

Despite these drawbacks, “the convenience and efficacy of telehealth as well as its ability to maintain separation while social distancing recommendations are in place make it an effective way for dermatologists to continue to provide quality and safe care during the pandemics as well as during potential future public health crises,” the investigators concluded.

Many medical practices turned to telemedicine when the pandemic shut down the economy last spring, but what do dermatology patients think about the socially distant approach?

and 80% said that they would consider another such visit in the future, according to a survey conducted at George Washington University in Washington.

Although “telehealth is not without its drawbacks … it is clear from this study that the majority of patients feel positively towards teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic and [believe it] can be a suitable alternative for patients who are unable to meet with their providers in person,” Samuel Yeroushalmi, Sarah H. Millan, and associates at the university said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

When presented with a set of statements about the telehealth experience, the 168 survey respondents largely agreed that the overall appointment was satisfactory (80.8%), that minimal barriers were present (78.1%), and that the quality of care was similar to an in-person visit (62.5%), the investigators said.

Other factors, however, were not as well supported. Less than half (47.2%) of the respondents agreed that the telehealth appointments were more cost effective, and just over half (54.7%) agreed that they provided an adequate skin exam, they reported.

Of the set of 14 statements given to the patients – all of whom had at least one telehealth visit with the GW clinic between March 2 and June 17, 2020 – the one on the adequacy of the skin exam provided the largest share of disagreement at 27.1%, Mr. Yeroushalmi and Ms. Millan, medical students at the university and coauthors.

The lack of physical touch was mentioned most often (26.8%) when respondents were asked about their reasons for disliking telehealth visits, followed by the feeling that they had received an inadequate assessment (15.7%), they said.

Despite these drawbacks, “the convenience and efficacy of telehealth as well as its ability to maintain separation while social distancing recommendations are in place make it an effective way for dermatologists to continue to provide quality and safe care during the pandemics as well as during potential future public health crises,” the investigators concluded.

Many medical practices turned to telemedicine when the pandemic shut down the economy last spring, but what do dermatology patients think about the socially distant approach?

and 80% said that they would consider another such visit in the future, according to a survey conducted at George Washington University in Washington.

Although “telehealth is not without its drawbacks … it is clear from this study that the majority of patients feel positively towards teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic and [believe it] can be a suitable alternative for patients who are unable to meet with their providers in person,” Samuel Yeroushalmi, Sarah H. Millan, and associates at the university said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

When presented with a set of statements about the telehealth experience, the 168 survey respondents largely agreed that the overall appointment was satisfactory (80.8%), that minimal barriers were present (78.1%), and that the quality of care was similar to an in-person visit (62.5%), the investigators said.

Other factors, however, were not as well supported. Less than half (47.2%) of the respondents agreed that the telehealth appointments were more cost effective, and just over half (54.7%) agreed that they provided an adequate skin exam, they reported.

Of the set of 14 statements given to the patients – all of whom had at least one telehealth visit with the GW clinic between March 2 and June 17, 2020 – the one on the adequacy of the skin exam provided the largest share of disagreement at 27.1%, Mr. Yeroushalmi and Ms. Millan, medical students at the university and coauthors.

The lack of physical touch was mentioned most often (26.8%) when respondents were asked about their reasons for disliking telehealth visits, followed by the feeling that they had received an inadequate assessment (15.7%), they said.

Despite these drawbacks, “the convenience and efficacy of telehealth as well as its ability to maintain separation while social distancing recommendations are in place make it an effective way for dermatologists to continue to provide quality and safe care during the pandemics as well as during potential future public health crises,” the investigators concluded.

FROM JOURNAL OF DRUGS IN DERMATOLOGY

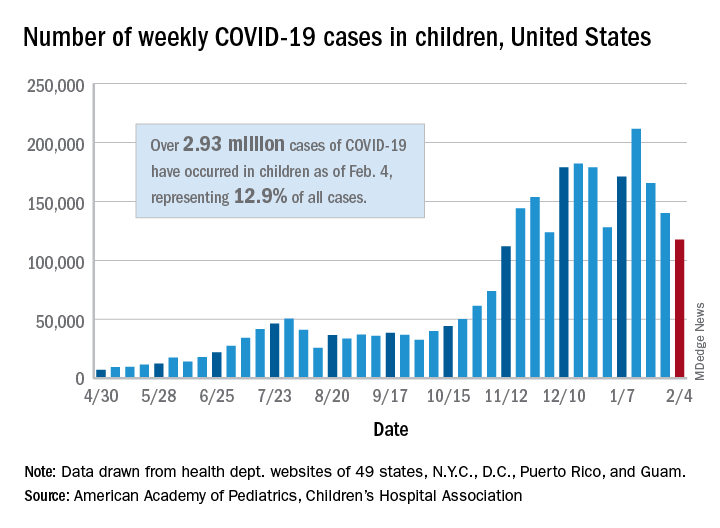

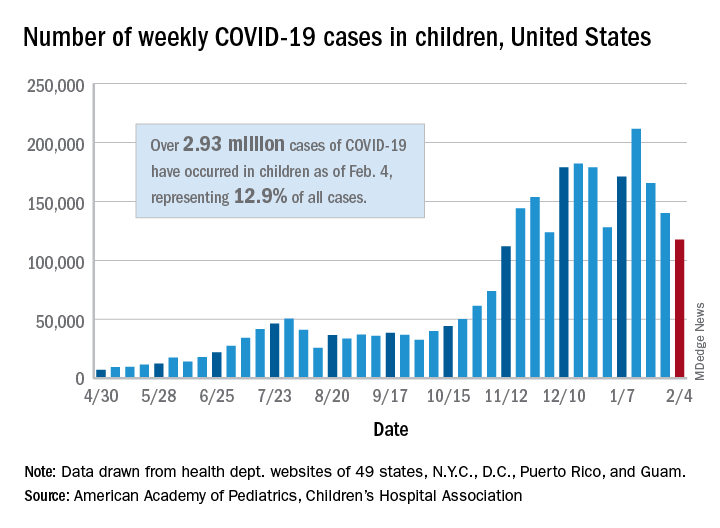

COVID-19 in children: New cases down for third straight week

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

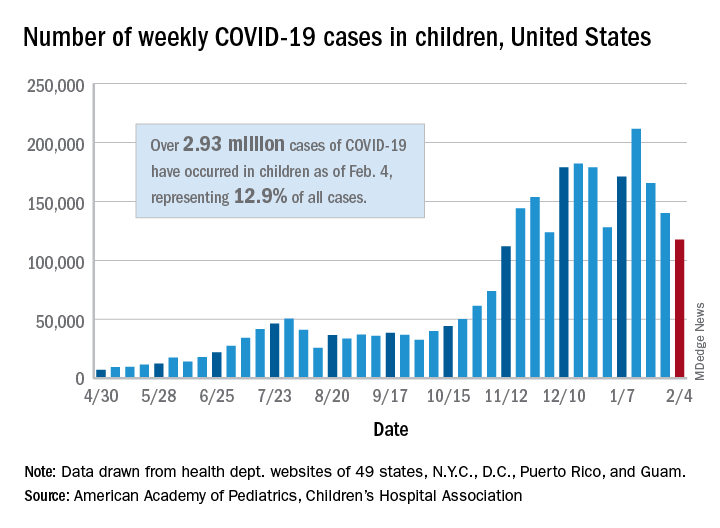

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop

Despite a drop in the number of weekly COVID-19 cases, children made up a larger share of cases for the fourth consecutive week, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Just over 140,000 new cases of COVID-19 in children were reported for the week of Jan. 22-28, down from 165,000 the week before and down from the record high of 211,000 2 weeks earlier, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Since the beginning of January, however, the proportion of weekly cases occurring in children has risen from 12.9% to 15.1%, based on data collected by the AAP/CHA from the health department websites of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, 2.81 million children have been infected by the coronavirus, representing 12.8% of the total for all ages, which is almost 22 million. The cumulative rate since the start of the pandemic passed 3,700 cases per 100,000 children after increasing by 5.2% over the previous week, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Cumulative hospitalizations in children just passed 11,000 in the 24 states (and New York City) that are reporting data for children, which represents 1.8% of COVID-19–related admissions for all ages, a proportion that has not changed since mid-November. Ten more deaths in children were reported during Jan. 22-28, bringing the total to 215 in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are tracking mortality.

In the 10 states that are reporting data on testing, rates of positive results in children range from 7.1% in Indiana, in which children make up the largest proportion of total tests performed (18.1%) to 28.4% in Iowa, where children make up the smallest proportion of tests (6.0%), the AAP and CHA said.

Despite a drop in the number of weekly COVID-19 cases, children made up a larger share of cases for the fourth consecutive week, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Just over 140,000 new cases of COVID-19 in children were reported for the week of Jan. 22-28, down from 165,000 the week before and down from the record high of 211,000 2 weeks earlier, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Since the beginning of January, however, the proportion of weekly cases occurring in children has risen from 12.9% to 15.1%, based on data collected by the AAP/CHA from the health department websites of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, 2.81 million children have been infected by the coronavirus, representing 12.8% of the total for all ages, which is almost 22 million. The cumulative rate since the start of the pandemic passed 3,700 cases per 100,000 children after increasing by 5.2% over the previous week, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Cumulative hospitalizations in children just passed 11,000 in the 24 states (and New York City) that are reporting data for children, which represents 1.8% of COVID-19–related admissions for all ages, a proportion that has not changed since mid-November. Ten more deaths in children were reported during Jan. 22-28, bringing the total to 215 in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are tracking mortality.

In the 10 states that are reporting data on testing, rates of positive results in children range from 7.1% in Indiana, in which children make up the largest proportion of total tests performed (18.1%) to 28.4% in Iowa, where children make up the smallest proportion of tests (6.0%), the AAP and CHA said.

Despite a drop in the number of weekly COVID-19 cases, children made up a larger share of cases for the fourth consecutive week, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Just over 140,000 new cases of COVID-19 in children were reported for the week of Jan. 22-28, down from 165,000 the week before and down from the record high of 211,000 2 weeks earlier, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Since the beginning of January, however, the proportion of weekly cases occurring in children has risen from 12.9% to 15.1%, based on data collected by the AAP/CHA from the health department websites of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, 2.81 million children have been infected by the coronavirus, representing 12.8% of the total for all ages, which is almost 22 million. The cumulative rate since the start of the pandemic passed 3,700 cases per 100,000 children after increasing by 5.2% over the previous week, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Cumulative hospitalizations in children just passed 11,000 in the 24 states (and New York City) that are reporting data for children, which represents 1.8% of COVID-19–related admissions for all ages, a proportion that has not changed since mid-November. Ten more deaths in children were reported during Jan. 22-28, bringing the total to 215 in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are tracking mortality.

In the 10 states that are reporting data on testing, rates of positive results in children range from 7.1% in Indiana, in which children make up the largest proportion of total tests performed (18.1%) to 28.4% in Iowa, where children make up the smallest proportion of tests (6.0%), the AAP and CHA said.

Meta-analysis finds much less lupus than expected

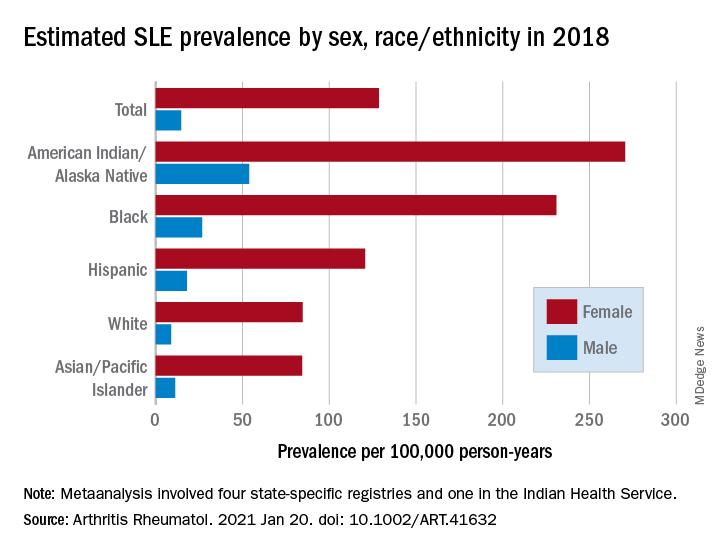

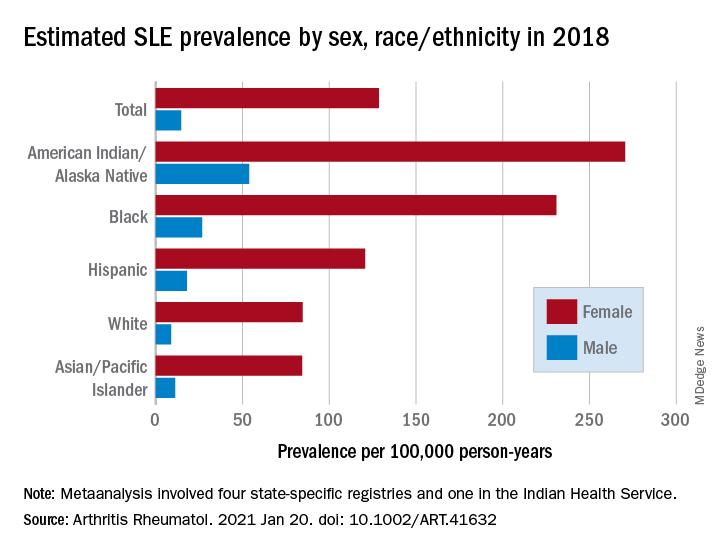

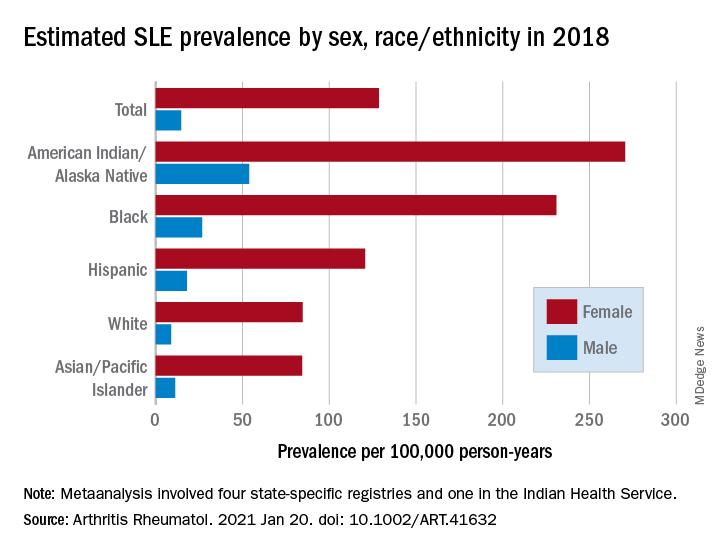

The prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) appears to be much lower than previously believed and may pose “a potential risk to research funding for the disease,” according to results of a meta-analysis involving a network of population-based registries.

“When we started this study, a widely cited lupus statistic was that approximately 1.5 million Americans were affected. Our meta-analysis found the actual prevalence to be slightly more than 200,000: a number that approaches the [Food and Drug Administration’s] definition of a rare disease,” Emily Somers, PhD, ScM, senior author and associate professor of rheumatology and environmental health sciences at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a written statement.

Their estimates, published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology, put the overall SLE prevalence in the United States at 72.8 per 100,000 person-years in 2018, with nearly nine times more females affected (128.7 cases per 100,000) than males (14.6 per 100,000). Race and ethnicity also play a role, as prevalence was highest among American Indian/Alaska Native and Black females, with Hispanic females lower but still higher than White and Asian/Pacific Islander females, Peter M. Izmirly, MD, MSc, of New York University, the lead author, and associates said.

SLE prevalence was distributed similarly in men, although there was a greater relative margin between American Indians/Alaska Natives (53.8 cases per 100,000 person-years) and Blacks (26.7 per 100,000), and Asians/Pacific Islanders were higher than Whites (11.2 vs. 8.9), the investigators reported.

The meta-analysis leveraged data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national lupus registries, which include four state-specific SLE registries and a fifth in the Indian Health Service. All cases of SLE occurred in 2002-2009, and the data were age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. population and separately extrapolated to the 2018 U.S. Census population, they explained.

The analysis was funded by cooperative agreements between the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York University, and the CDC and National Institute of Health.

The prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) appears to be much lower than previously believed and may pose “a potential risk to research funding for the disease,” according to results of a meta-analysis involving a network of population-based registries.

“When we started this study, a widely cited lupus statistic was that approximately 1.5 million Americans were affected. Our meta-analysis found the actual prevalence to be slightly more than 200,000: a number that approaches the [Food and Drug Administration’s] definition of a rare disease,” Emily Somers, PhD, ScM, senior author and associate professor of rheumatology and environmental health sciences at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a written statement.

Their estimates, published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology, put the overall SLE prevalence in the United States at 72.8 per 100,000 person-years in 2018, with nearly nine times more females affected (128.7 cases per 100,000) than males (14.6 per 100,000). Race and ethnicity also play a role, as prevalence was highest among American Indian/Alaska Native and Black females, with Hispanic females lower but still higher than White and Asian/Pacific Islander females, Peter M. Izmirly, MD, MSc, of New York University, the lead author, and associates said.

SLE prevalence was distributed similarly in men, although there was a greater relative margin between American Indians/Alaska Natives (53.8 cases per 100,000 person-years) and Blacks (26.7 per 100,000), and Asians/Pacific Islanders were higher than Whites (11.2 vs. 8.9), the investigators reported.

The meta-analysis leveraged data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national lupus registries, which include four state-specific SLE registries and a fifth in the Indian Health Service. All cases of SLE occurred in 2002-2009, and the data were age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. population and separately extrapolated to the 2018 U.S. Census population, they explained.

The analysis was funded by cooperative agreements between the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York University, and the CDC and National Institute of Health.

The prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) appears to be much lower than previously believed and may pose “a potential risk to research funding for the disease,” according to results of a meta-analysis involving a network of population-based registries.

“When we started this study, a widely cited lupus statistic was that approximately 1.5 million Americans were affected. Our meta-analysis found the actual prevalence to be slightly more than 200,000: a number that approaches the [Food and Drug Administration’s] definition of a rare disease,” Emily Somers, PhD, ScM, senior author and associate professor of rheumatology and environmental health sciences at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a written statement.

Their estimates, published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology, put the overall SLE prevalence in the United States at 72.8 per 100,000 person-years in 2018, with nearly nine times more females affected (128.7 cases per 100,000) than males (14.6 per 100,000). Race and ethnicity also play a role, as prevalence was highest among American Indian/Alaska Native and Black females, with Hispanic females lower but still higher than White and Asian/Pacific Islander females, Peter M. Izmirly, MD, MSc, of New York University, the lead author, and associates said.

SLE prevalence was distributed similarly in men, although there was a greater relative margin between American Indians/Alaska Natives (53.8 cases per 100,000 person-years) and Blacks (26.7 per 100,000), and Asians/Pacific Islanders were higher than Whites (11.2 vs. 8.9), the investigators reported.

The meta-analysis leveraged data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national lupus registries, which include four state-specific SLE registries and a fifth in the Indian Health Service. All cases of SLE occurred in 2002-2009, and the data were age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. population and separately extrapolated to the 2018 U.S. Census population, they explained.

The analysis was funded by cooperative agreements between the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York University, and the CDC and National Institute of Health.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Chart review for cosmetic procedures: 2019 was a good year

Cosmetic procedures continued to increase in popularity in 2019, and body sculpting and laser/light/energy-based procedures led the way, according to a survey by the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery.

the largest proportional rise among the major categories of cosmetic procedures, the ASDS reported in its annual member survey.

Use of laser/light/energy-based devices was up by a much lower 18%, but the increase in the actual number of procedures – nearly 637,000 more than 2018 – was larger than any other category, the ASDS said.

Procedures categorized as “other rejuvenation” – microneedling, platelet-rich plasma, hair rejuvenation, and thread lifts – were another bright spot in the cosmetic lineup in 2019, rising 38% over their 2018 volume. Injectable neuromodulator treatments, which were second in overall volume with almost 2.4 million procedures, were up by 12.5% in 2019, compared with 2018, the ASDS said.

The injectable soft-tissue fillers, however, did not produce any noteworthy gain in the volume of procedures for the second consecutive year. Meanwhile, the number of chemical peel procedures dropped by almost 16% in 2019 after rising for the last 2 years, the ASDS reported.

A closer look at the body-sculpting sector also shows some declines in 2019, despite the overall success: Cryolipolysis procedures were down by 10.3% and deoxycholic acid procedures slipped 13.7%. The biggest addition – over 157,000 procedures – came from muscle-toning devices, which were new to the survey last year, the ASDS noted.

The survey was conducted among the society’s members from May 7 to July 31, 2020, and the 514 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

Cosmetic procedures continued to increase in popularity in 2019, and body sculpting and laser/light/energy-based procedures led the way, according to a survey by the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery.

the largest proportional rise among the major categories of cosmetic procedures, the ASDS reported in its annual member survey.

Use of laser/light/energy-based devices was up by a much lower 18%, but the increase in the actual number of procedures – nearly 637,000 more than 2018 – was larger than any other category, the ASDS said.

Procedures categorized as “other rejuvenation” – microneedling, platelet-rich plasma, hair rejuvenation, and thread lifts – were another bright spot in the cosmetic lineup in 2019, rising 38% over their 2018 volume. Injectable neuromodulator treatments, which were second in overall volume with almost 2.4 million procedures, were up by 12.5% in 2019, compared with 2018, the ASDS said.

The injectable soft-tissue fillers, however, did not produce any noteworthy gain in the volume of procedures for the second consecutive year. Meanwhile, the number of chemical peel procedures dropped by almost 16% in 2019 after rising for the last 2 years, the ASDS reported.

A closer look at the body-sculpting sector also shows some declines in 2019, despite the overall success: Cryolipolysis procedures were down by 10.3% and deoxycholic acid procedures slipped 13.7%. The biggest addition – over 157,000 procedures – came from muscle-toning devices, which were new to the survey last year, the ASDS noted.

The survey was conducted among the society’s members from May 7 to July 31, 2020, and the 514 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

Cosmetic procedures continued to increase in popularity in 2019, and body sculpting and laser/light/energy-based procedures led the way, according to a survey by the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery.

the largest proportional rise among the major categories of cosmetic procedures, the ASDS reported in its annual member survey.

Use of laser/light/energy-based devices was up by a much lower 18%, but the increase in the actual number of procedures – nearly 637,000 more than 2018 – was larger than any other category, the ASDS said.

Procedures categorized as “other rejuvenation” – microneedling, platelet-rich plasma, hair rejuvenation, and thread lifts – were another bright spot in the cosmetic lineup in 2019, rising 38% over their 2018 volume. Injectable neuromodulator treatments, which were second in overall volume with almost 2.4 million procedures, were up by 12.5% in 2019, compared with 2018, the ASDS said.

The injectable soft-tissue fillers, however, did not produce any noteworthy gain in the volume of procedures for the second consecutive year. Meanwhile, the number of chemical peel procedures dropped by almost 16% in 2019 after rising for the last 2 years, the ASDS reported.

A closer look at the body-sculpting sector also shows some declines in 2019, despite the overall success: Cryolipolysis procedures were down by 10.3% and deoxycholic acid procedures slipped 13.7%. The biggest addition – over 157,000 procedures – came from muscle-toning devices, which were new to the survey last year, the ASDS noted.

The survey was conducted among the society’s members from May 7 to July 31, 2020, and the 514 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.