User login

Morphology of Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome in Skin of Color

Mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) are non-Hodgkin T-cell lymphomas that make up the majority of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. These conditions commonly affect Black patients, with an incidence rate of 12.6 cases of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas per million individuals vs 9.8 per million individuals in non–skin of color (SoC) patients.1 However, educational resources tend to focus on the clinical manifestations of MF/SS in lighter skin types, describing MF as erythematous patches, plaques, or tumors presenting in non–sun-exposed areas of the skin and SS as generalized erythroderma.2 Skin of color, comprised of Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI,3 is poorly represented across dermatology textbooks,4,5 medical student resources,6 and peer-reviewed publications,7 raising awareness for the need to address this disparity.

Skin of color patients with MF/SS display variable morphologies, including features such as hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation,8 the latter being exceedingly rare in non-SoC patients.9 Familiarity with these differences among providers is essential to allow for equitable diagnosis and treatment across all skin types, especially in light of data predicting that by 2044 more than 50% of the US population will be people of color.10 Patients with SoC are of many ethnic and racial backgrounds, including Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Asian.11

Along with morphologic differences, there also are several racial disparities in the prognosis and survival of patients with MF/SS. Black patients diagnosed with MF present with greater body surface area affected, and Black women with MF have reduced survival rates compared to their White counterparts.12 Given these racial disparities in survival and representation in educational resources, we aimed to quantify the frequency of various morphologic characteristics of MF/SS in patients with SoC vs non-SoC patients to facilitate better recognition of early MF/SS in SoC patients by medical providers.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois). We identified all patients with FSTs IV to VI and biopsy-proven MF/SS who had been clinically photographed in our clinic from January 1998 to December 2019. Only photographs that were high quality enough to review morphologic features were included in our review. Fitzpatrick skin type was determined based on electronic medical record documentation. If photographs were available from multiple visits for the same patient, only those showing posttreatment nonactive lesions were included. Additionally, 36 patients with FSTs I to III (non-SoC) and biopsy-proven MF/SS were included in our review as a comparison with the SoC cohort. The primary outcomes for this study included the presence of scale, erythema, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, violaceous color, lichenification, silver hue, dyschromia, alopecia, poikiloderma, atrophy, and ulceration in active lesions. Dyschromia was defined by the presence of both hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation. Poikiloderma was defined by hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, and atrophy. Secondary outcomes included evaluation of those same characteristics in posttreatment nonactive lesions. All photographs were independently assessed by 3 authors (M.L.E., C.J.W., J.M.M.), and discrepancies were resolved by further review of the photograph in question and discussion.

Statistical Analysis—Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

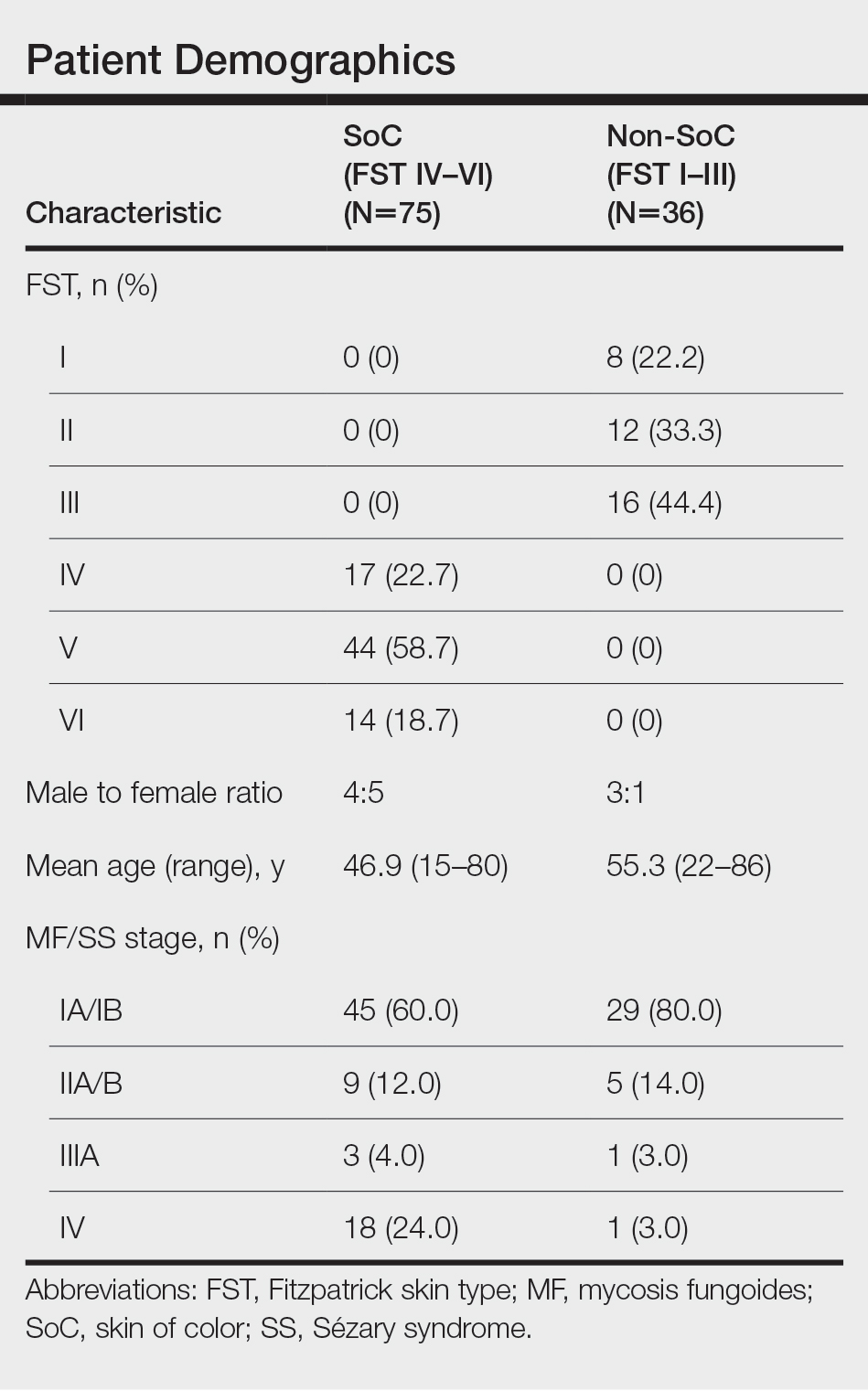

We reviewed photographs of 111 patients across all skin types (8, FST I; 12, FST II; 16, FST III; 17, FST IV; 44, FST V; 14, FST VI). The cohort was 47% female, and the mean age was 49.7 years (range, 15–86 years). The majority of the cohort had early-stage MF (stage IA or IB). There were more cases of SS in the SoC cohort than the non-SoC cohort (Table). Only 5 photographs had discrepancies and required discussion among the reviewers to achieve consensus.

![Frequency of morphologic features found in skin of color (SoC [Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI]) vs non-SoC (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome Frequency of morphologic features found in skin of color (SoC [Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI]) vs non-SoC (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Espinosa_1.JPG)

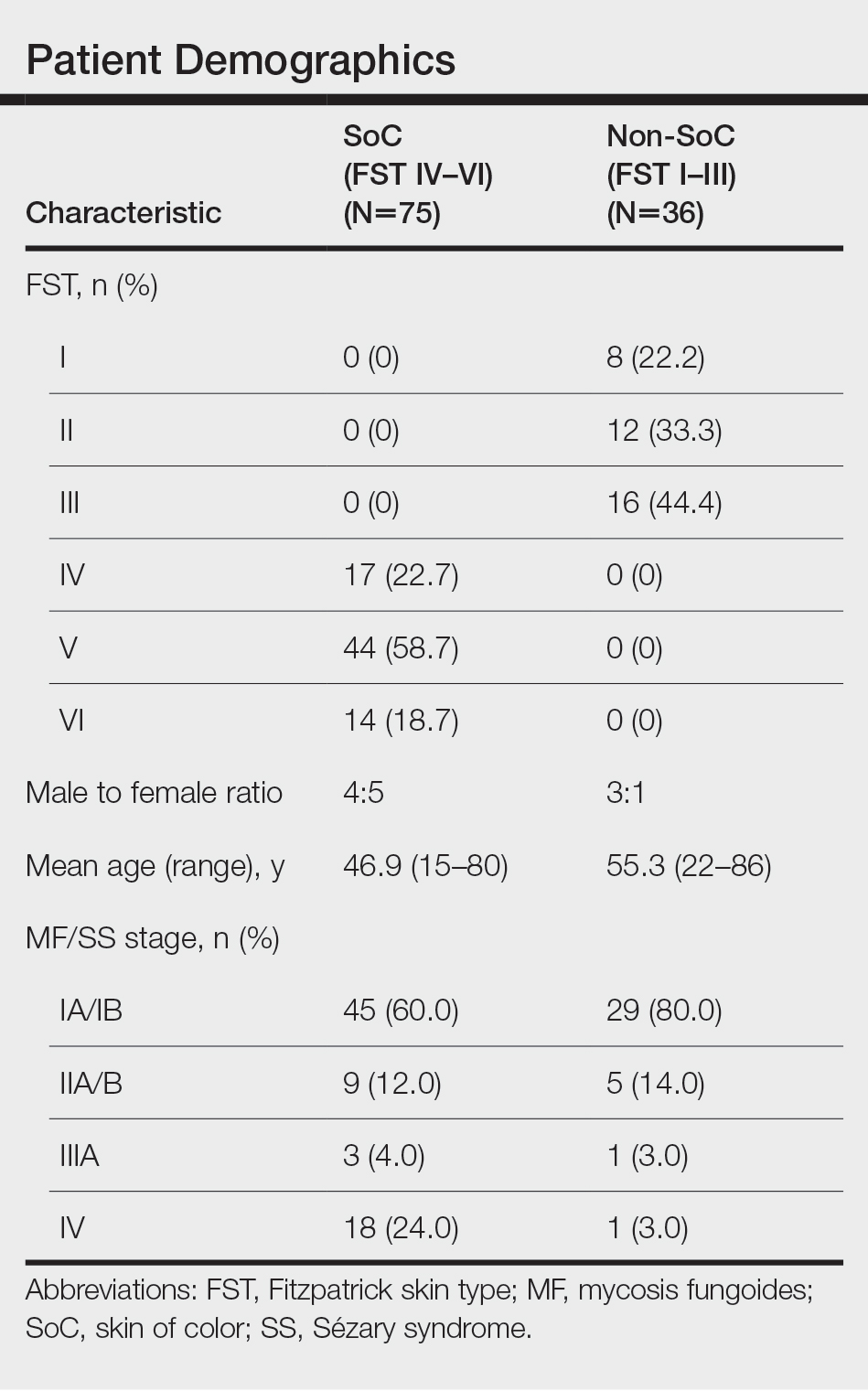

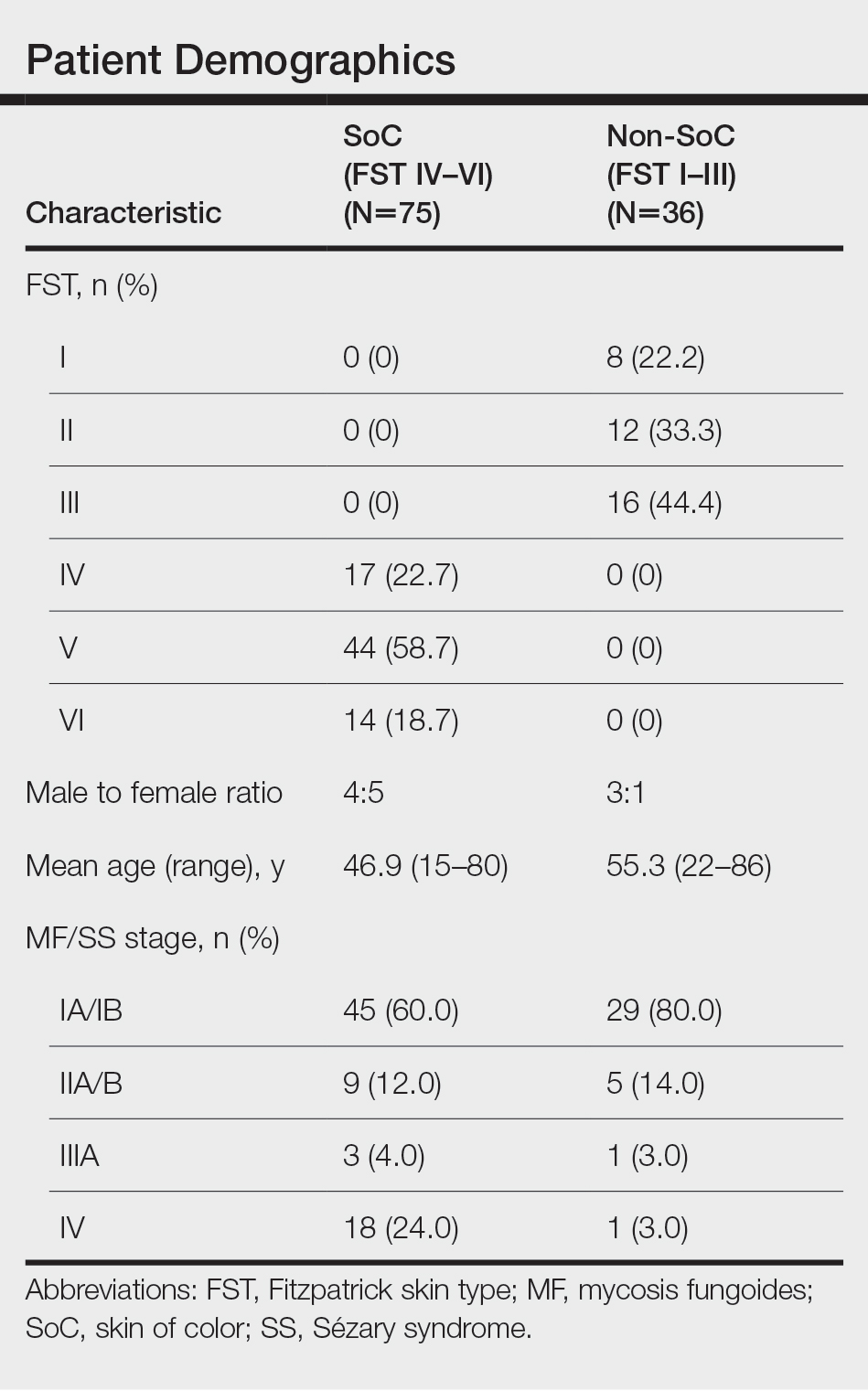

Regarding morphologic characteristics in active lesions (Figure 1), scale was present in almost all patients (99% in SoC, 94% in non-SoC). Erythema was present in nearly all non-SoC patients (94%) but only in 69% of SoC patients (P=.003). Poikiloderma also was found to be present at higher frequencies in non-SoC patients compared with SoC patients (19% and 4%, respectively [P=.008]). However, hyperpigmentation (80% vs 39%), lichenification (43% vs 17%), and silver hue (25% vs 3%) were more common in SoC patients than non-SoC patients (P<.05). There were no significant differences in the remaining features, including hypopigmentation (39% vs 25%), dyschromia (24% vs 19%), violaceous color (44% vs 25%), atrophy (11% vs 22%), alopecia (23% vs 31%), and ulceration (16% vs 8%) between SoC and non-SoC patients (P>.05). Photographs of MF in patients with SoC can be seen in Figure 2.

![Representative photographs of mycosis fungoides (MF) in skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types [FSTs] IV–VI) Representative photographs of mycosis fungoides (MF) in skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types [FSTs] IV–VI)](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/CT109003003_e_Fig2_ABCDE.JPG)

Posttreatment (nonactive) photographs were available for 26 patients (6 non-SoC, 20 SoC). We found that across all FST groups, hyperpigmentation was more common than hypopigmentation in areas of previously active disease. Statistical analysis was not completed given that few non-SoC photographs were available for comparison.

Comment

This qualitative review demonstrates the heterogeneity of MF/SS in SoC patients and that these conditions do not present in this population with the classic erythematous patches and plaques found in non-SoC patients. We found that hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and silver hue were present at higher rates in patients with FSTs IV to VI compared to those with FSTs I to III, which had higher rates of erythema and poikiloderma. Familiarity with these morphologic features along with increased exposure to clinical photographs of MF/SS in SoC patients will aid in the visual recognition required for this diagnosis, since erythema is harder to identify in darker skin types. Recognizing the unique findings of MF in patients with SoC as well as in patients with lighter skin types will enable earlier diagnosis and treatment of MF/SS across all skin types. If MF is diagnosed and treated early, life expectancy is similar to that of patients without MF.13 However, the 5-year survival rate for advanced-stage MF/SS is 52% across all skin types, and studies have found that Black patients with advanced-stage disease have worse outcomes despite accounting for demographic factors and tumor stage.14,15 Given the worse outcomes in SoC patients with advanced-stage MF/SS, earlier diagnosis could help address this disparity.8,13,14 Similar morphologic features could be used in diagnosing other inflammatory conditions; studies have shown that the lack of recognition of erythema in Black children has led to delayed diagnosis of atopic dermatitis and subsequent inadequate treatment.16,17

The morphologic presentation of MF/SS in SoC patients also can influence an optimal treatment plan for this population. Hypopigmented MF responds better to phototherapy than hyperpigmented MF, as phototherapy has been shown to have decreased efficacy with increasing FST.18 Therefore, for patients with FSTs IV to VI, topical agents such as nitrogen mustard or bexarotene may be more suitable treatment options, as the efficacy of these treatments is independent of skin color.8 However, nitrogen mustard commonly leads to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and topical bexarotene may lead to erythema or irritation; therefore, providers must counsel patients on these possible side effects. For refractory disease, adjunct systemic treatments such as oral bexarotene, subcutaneous interferon, methotrexate, or radiation therapy may be considered.8

In addition to aiding in the prompt diagnosis and treatment of MF/SS in SoC patients, our findings may be used to better assess the extent of disease and distinguish between active MF/SS lesions vs xerosis cutis or residual dyschromia from previously treated lesions. It is important to note that these morphologic features must be taken into account with a complete history and work-up. The differential diagnosis of MF/SS includes conditions such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and drug reactions, which may have similar morphology in SoC.19

Limitations of our study include the single-center design and the use of photographs instead of in-person examination; however, our cutaneous lymphoma clinic serves a diverse patient population, and our 3 reviewers rated the photographs independently. Discussion amongst the reviewers to address discrepancies was only required for 5 photographs, indicating the high inter-reviewer reliability. Additionally, the original purpose of FST was to assess for the propensity of the skin to burn when undergoing phototherapy, not to serve as a marker for skin color. We recommend trainees and clinicians be mindful about the purpose of FST and to use inclusive language (eg, using the terms skin irritation, skin tenderness, or skin becoming darker from the sun instead of tanning) when determining FST in darker-skinned individuals.20 Future directions include examining if certain treatments are associated with prolonged dyschromia.

Conclusion

In our single-institution retrospective study, we found differences in the morphologic presentation of MF/SS in SoC patients vs non-SoC patients. While erythema is a common feature in non-SoC patients, clinical features of hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and silver hue should be carefully evaluated in the diagnosis of MF/SS in SoC patients. Knowledge of the heterogenous presentation of MF/SS in patients with SoC allows for expedited diagnosis and treatment, leading to better clinical outcomes. Valuable resources, including Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color, the Skin of Color Society, and VisualDx educate providers on how dermatologic conditions present in darker skin types. However, there is still work to be done to enhance diversity in educational resources in order to provide equitable care to patients of all skin types.

- Korgavkar K, Xiong M, Weinstock M. Changing incidence trends of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1295-1299. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5526

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.E1-E16; quiz 221-222. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.049

- Tull RZ, Kerby E, Subash JJ, et al. Ethnic skin centers in the United States: where are we in 2020?. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1757-1759. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.054

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.084

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Shobajo MT, et al. Skin of color representation in medical education: an analysis of popular preparatory materials used for United States medical licensing examinations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:773-775. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.112

- Montgomery SN, Elbuluk N. A quantitative analysis of research publications focused on the top chief complaints in skin of color patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:241-242. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.031

- Hinds GA, Heald P. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:359-375; quiz 376-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.031

- Ardigó M, Borroni G, Muscardin L, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Caucasian patients: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:264-270. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00907-1

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Updated October 8, 2021. Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.html

- Taylor SC, Kyei A. Defining skin of color. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Huang AH, Kwatra SG, Khanna R, et al. Racial disparities in the clinical presentation and prognosis of patients with mycosis fungoides. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111:633-639. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.08.006

- Kim YH, Jensen RA, Watanabe GL, et al. Clinical stage IA (limited patch and plaque) mycosis fungoides. a long-term outcome analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1309-1313.

- Scarisbrick JJ, Prince HM, Vermeer MH, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma international consortium study of outcome in advanced stages of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: effect of specific prognostic markers on survival and development of a prognostic model. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3766-3773. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.7142

- Nath SK, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Poorer prognosis of African-American patients with mycosis fungoides: an analysis of the SEER dataset, 1988 to 2008. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:419-423. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2013.12.018

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x

- Poladian K, De Souza B, McMichael AJ. Atopic dermatitis in adolescents with skin of color. Cutis. 2019;104:164-168.

- Yones SS, Palmer RA, Garibaldinos TT, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy of psoralen-UV-A therapy vs narrowband UV-B therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:836-842. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.7.836

- Currimbhoy S, Pandya AG. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

Mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) are non-Hodgkin T-cell lymphomas that make up the majority of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. These conditions commonly affect Black patients, with an incidence rate of 12.6 cases of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas per million individuals vs 9.8 per million individuals in non–skin of color (SoC) patients.1 However, educational resources tend to focus on the clinical manifestations of MF/SS in lighter skin types, describing MF as erythematous patches, plaques, or tumors presenting in non–sun-exposed areas of the skin and SS as generalized erythroderma.2 Skin of color, comprised of Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI,3 is poorly represented across dermatology textbooks,4,5 medical student resources,6 and peer-reviewed publications,7 raising awareness for the need to address this disparity.

Skin of color patients with MF/SS display variable morphologies, including features such as hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation,8 the latter being exceedingly rare in non-SoC patients.9 Familiarity with these differences among providers is essential to allow for equitable diagnosis and treatment across all skin types, especially in light of data predicting that by 2044 more than 50% of the US population will be people of color.10 Patients with SoC are of many ethnic and racial backgrounds, including Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Asian.11

Along with morphologic differences, there also are several racial disparities in the prognosis and survival of patients with MF/SS. Black patients diagnosed with MF present with greater body surface area affected, and Black women with MF have reduced survival rates compared to their White counterparts.12 Given these racial disparities in survival and representation in educational resources, we aimed to quantify the frequency of various morphologic characteristics of MF/SS in patients with SoC vs non-SoC patients to facilitate better recognition of early MF/SS in SoC patients by medical providers.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois). We identified all patients with FSTs IV to VI and biopsy-proven MF/SS who had been clinically photographed in our clinic from January 1998 to December 2019. Only photographs that were high quality enough to review morphologic features were included in our review. Fitzpatrick skin type was determined based on electronic medical record documentation. If photographs were available from multiple visits for the same patient, only those showing posttreatment nonactive lesions were included. Additionally, 36 patients with FSTs I to III (non-SoC) and biopsy-proven MF/SS were included in our review as a comparison with the SoC cohort. The primary outcomes for this study included the presence of scale, erythema, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, violaceous color, lichenification, silver hue, dyschromia, alopecia, poikiloderma, atrophy, and ulceration in active lesions. Dyschromia was defined by the presence of both hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation. Poikiloderma was defined by hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, and atrophy. Secondary outcomes included evaluation of those same characteristics in posttreatment nonactive lesions. All photographs were independently assessed by 3 authors (M.L.E., C.J.W., J.M.M.), and discrepancies were resolved by further review of the photograph in question and discussion.

Statistical Analysis—Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed photographs of 111 patients across all skin types (8, FST I; 12, FST II; 16, FST III; 17, FST IV; 44, FST V; 14, FST VI). The cohort was 47% female, and the mean age was 49.7 years (range, 15–86 years). The majority of the cohort had early-stage MF (stage IA or IB). There were more cases of SS in the SoC cohort than the non-SoC cohort (Table). Only 5 photographs had discrepancies and required discussion among the reviewers to achieve consensus.

![Frequency of morphologic features found in skin of color (SoC [Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI]) vs non-SoC (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome Frequency of morphologic features found in skin of color (SoC [Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI]) vs non-SoC (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Espinosa_1.JPG)

Regarding morphologic characteristics in active lesions (Figure 1), scale was present in almost all patients (99% in SoC, 94% in non-SoC). Erythema was present in nearly all non-SoC patients (94%) but only in 69% of SoC patients (P=.003). Poikiloderma also was found to be present at higher frequencies in non-SoC patients compared with SoC patients (19% and 4%, respectively [P=.008]). However, hyperpigmentation (80% vs 39%), lichenification (43% vs 17%), and silver hue (25% vs 3%) were more common in SoC patients than non-SoC patients (P<.05). There were no significant differences in the remaining features, including hypopigmentation (39% vs 25%), dyschromia (24% vs 19%), violaceous color (44% vs 25%), atrophy (11% vs 22%), alopecia (23% vs 31%), and ulceration (16% vs 8%) between SoC and non-SoC patients (P>.05). Photographs of MF in patients with SoC can be seen in Figure 2.

![Representative photographs of mycosis fungoides (MF) in skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types [FSTs] IV–VI) Representative photographs of mycosis fungoides (MF) in skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types [FSTs] IV–VI)](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/CT109003003_e_Fig2_ABCDE.JPG)

Posttreatment (nonactive) photographs were available for 26 patients (6 non-SoC, 20 SoC). We found that across all FST groups, hyperpigmentation was more common than hypopigmentation in areas of previously active disease. Statistical analysis was not completed given that few non-SoC photographs were available for comparison.

Comment

This qualitative review demonstrates the heterogeneity of MF/SS in SoC patients and that these conditions do not present in this population with the classic erythematous patches and plaques found in non-SoC patients. We found that hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and silver hue were present at higher rates in patients with FSTs IV to VI compared to those with FSTs I to III, which had higher rates of erythema and poikiloderma. Familiarity with these morphologic features along with increased exposure to clinical photographs of MF/SS in SoC patients will aid in the visual recognition required for this diagnosis, since erythema is harder to identify in darker skin types. Recognizing the unique findings of MF in patients with SoC as well as in patients with lighter skin types will enable earlier diagnosis and treatment of MF/SS across all skin types. If MF is diagnosed and treated early, life expectancy is similar to that of patients without MF.13 However, the 5-year survival rate for advanced-stage MF/SS is 52% across all skin types, and studies have found that Black patients with advanced-stage disease have worse outcomes despite accounting for demographic factors and tumor stage.14,15 Given the worse outcomes in SoC patients with advanced-stage MF/SS, earlier diagnosis could help address this disparity.8,13,14 Similar morphologic features could be used in diagnosing other inflammatory conditions; studies have shown that the lack of recognition of erythema in Black children has led to delayed diagnosis of atopic dermatitis and subsequent inadequate treatment.16,17

The morphologic presentation of MF/SS in SoC patients also can influence an optimal treatment plan for this population. Hypopigmented MF responds better to phototherapy than hyperpigmented MF, as phototherapy has been shown to have decreased efficacy with increasing FST.18 Therefore, for patients with FSTs IV to VI, topical agents such as nitrogen mustard or bexarotene may be more suitable treatment options, as the efficacy of these treatments is independent of skin color.8 However, nitrogen mustard commonly leads to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and topical bexarotene may lead to erythema or irritation; therefore, providers must counsel patients on these possible side effects. For refractory disease, adjunct systemic treatments such as oral bexarotene, subcutaneous interferon, methotrexate, or radiation therapy may be considered.8

In addition to aiding in the prompt diagnosis and treatment of MF/SS in SoC patients, our findings may be used to better assess the extent of disease and distinguish between active MF/SS lesions vs xerosis cutis or residual dyschromia from previously treated lesions. It is important to note that these morphologic features must be taken into account with a complete history and work-up. The differential diagnosis of MF/SS includes conditions such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and drug reactions, which may have similar morphology in SoC.19

Limitations of our study include the single-center design and the use of photographs instead of in-person examination; however, our cutaneous lymphoma clinic serves a diverse patient population, and our 3 reviewers rated the photographs independently. Discussion amongst the reviewers to address discrepancies was only required for 5 photographs, indicating the high inter-reviewer reliability. Additionally, the original purpose of FST was to assess for the propensity of the skin to burn when undergoing phototherapy, not to serve as a marker for skin color. We recommend trainees and clinicians be mindful about the purpose of FST and to use inclusive language (eg, using the terms skin irritation, skin tenderness, or skin becoming darker from the sun instead of tanning) when determining FST in darker-skinned individuals.20 Future directions include examining if certain treatments are associated with prolonged dyschromia.

Conclusion

In our single-institution retrospective study, we found differences in the morphologic presentation of MF/SS in SoC patients vs non-SoC patients. While erythema is a common feature in non-SoC patients, clinical features of hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and silver hue should be carefully evaluated in the diagnosis of MF/SS in SoC patients. Knowledge of the heterogenous presentation of MF/SS in patients with SoC allows for expedited diagnosis and treatment, leading to better clinical outcomes. Valuable resources, including Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color, the Skin of Color Society, and VisualDx educate providers on how dermatologic conditions present in darker skin types. However, there is still work to be done to enhance diversity in educational resources in order to provide equitable care to patients of all skin types.

Mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) are non-Hodgkin T-cell lymphomas that make up the majority of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. These conditions commonly affect Black patients, with an incidence rate of 12.6 cases of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas per million individuals vs 9.8 per million individuals in non–skin of color (SoC) patients.1 However, educational resources tend to focus on the clinical manifestations of MF/SS in lighter skin types, describing MF as erythematous patches, plaques, or tumors presenting in non–sun-exposed areas of the skin and SS as generalized erythroderma.2 Skin of color, comprised of Fitzpatrick skin types (FSTs) IV to VI,3 is poorly represented across dermatology textbooks,4,5 medical student resources,6 and peer-reviewed publications,7 raising awareness for the need to address this disparity.

Skin of color patients with MF/SS display variable morphologies, including features such as hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation,8 the latter being exceedingly rare in non-SoC patients.9 Familiarity with these differences among providers is essential to allow for equitable diagnosis and treatment across all skin types, especially in light of data predicting that by 2044 more than 50% of the US population will be people of color.10 Patients with SoC are of many ethnic and racial backgrounds, including Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Asian.11

Along with morphologic differences, there also are several racial disparities in the prognosis and survival of patients with MF/SS. Black patients diagnosed with MF present with greater body surface area affected, and Black women with MF have reduced survival rates compared to their White counterparts.12 Given these racial disparities in survival and representation in educational resources, we aimed to quantify the frequency of various morphologic characteristics of MF/SS in patients with SoC vs non-SoC patients to facilitate better recognition of early MF/SS in SoC patients by medical providers.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois). We identified all patients with FSTs IV to VI and biopsy-proven MF/SS who had been clinically photographed in our clinic from January 1998 to December 2019. Only photographs that were high quality enough to review morphologic features were included in our review. Fitzpatrick skin type was determined based on electronic medical record documentation. If photographs were available from multiple visits for the same patient, only those showing posttreatment nonactive lesions were included. Additionally, 36 patients with FSTs I to III (non-SoC) and biopsy-proven MF/SS were included in our review as a comparison with the SoC cohort. The primary outcomes for this study included the presence of scale, erythema, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, violaceous color, lichenification, silver hue, dyschromia, alopecia, poikiloderma, atrophy, and ulceration in active lesions. Dyschromia was defined by the presence of both hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation. Poikiloderma was defined by hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, and atrophy. Secondary outcomes included evaluation of those same characteristics in posttreatment nonactive lesions. All photographs were independently assessed by 3 authors (M.L.E., C.J.W., J.M.M.), and discrepancies were resolved by further review of the photograph in question and discussion.

Statistical Analysis—Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed photographs of 111 patients across all skin types (8, FST I; 12, FST II; 16, FST III; 17, FST IV; 44, FST V; 14, FST VI). The cohort was 47% female, and the mean age was 49.7 years (range, 15–86 years). The majority of the cohort had early-stage MF (stage IA or IB). There were more cases of SS in the SoC cohort than the non-SoC cohort (Table). Only 5 photographs had discrepancies and required discussion among the reviewers to achieve consensus.

![Frequency of morphologic features found in skin of color (SoC [Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI]) vs non-SoC (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome Frequency of morphologic features found in skin of color (SoC [Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI]) vs non-SoC (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) patients with mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Espinosa_1.JPG)

Regarding morphologic characteristics in active lesions (Figure 1), scale was present in almost all patients (99% in SoC, 94% in non-SoC). Erythema was present in nearly all non-SoC patients (94%) but only in 69% of SoC patients (P=.003). Poikiloderma also was found to be present at higher frequencies in non-SoC patients compared with SoC patients (19% and 4%, respectively [P=.008]). However, hyperpigmentation (80% vs 39%), lichenification (43% vs 17%), and silver hue (25% vs 3%) were more common in SoC patients than non-SoC patients (P<.05). There were no significant differences in the remaining features, including hypopigmentation (39% vs 25%), dyschromia (24% vs 19%), violaceous color (44% vs 25%), atrophy (11% vs 22%), alopecia (23% vs 31%), and ulceration (16% vs 8%) between SoC and non-SoC patients (P>.05). Photographs of MF in patients with SoC can be seen in Figure 2.

![Representative photographs of mycosis fungoides (MF) in skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types [FSTs] IV–VI) Representative photographs of mycosis fungoides (MF) in skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types [FSTs] IV–VI)](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/CT109003003_e_Fig2_ABCDE.JPG)

Posttreatment (nonactive) photographs were available for 26 patients (6 non-SoC, 20 SoC). We found that across all FST groups, hyperpigmentation was more common than hypopigmentation in areas of previously active disease. Statistical analysis was not completed given that few non-SoC photographs were available for comparison.

Comment

This qualitative review demonstrates the heterogeneity of MF/SS in SoC patients and that these conditions do not present in this population with the classic erythematous patches and plaques found in non-SoC patients. We found that hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and silver hue were present at higher rates in patients with FSTs IV to VI compared to those with FSTs I to III, which had higher rates of erythema and poikiloderma. Familiarity with these morphologic features along with increased exposure to clinical photographs of MF/SS in SoC patients will aid in the visual recognition required for this diagnosis, since erythema is harder to identify in darker skin types. Recognizing the unique findings of MF in patients with SoC as well as in patients with lighter skin types will enable earlier diagnosis and treatment of MF/SS across all skin types. If MF is diagnosed and treated early, life expectancy is similar to that of patients without MF.13 However, the 5-year survival rate for advanced-stage MF/SS is 52% across all skin types, and studies have found that Black patients with advanced-stage disease have worse outcomes despite accounting for demographic factors and tumor stage.14,15 Given the worse outcomes in SoC patients with advanced-stage MF/SS, earlier diagnosis could help address this disparity.8,13,14 Similar morphologic features could be used in diagnosing other inflammatory conditions; studies have shown that the lack of recognition of erythema in Black children has led to delayed diagnosis of atopic dermatitis and subsequent inadequate treatment.16,17

The morphologic presentation of MF/SS in SoC patients also can influence an optimal treatment plan for this population. Hypopigmented MF responds better to phototherapy than hyperpigmented MF, as phototherapy has been shown to have decreased efficacy with increasing FST.18 Therefore, for patients with FSTs IV to VI, topical agents such as nitrogen mustard or bexarotene may be more suitable treatment options, as the efficacy of these treatments is independent of skin color.8 However, nitrogen mustard commonly leads to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and topical bexarotene may lead to erythema or irritation; therefore, providers must counsel patients on these possible side effects. For refractory disease, adjunct systemic treatments such as oral bexarotene, subcutaneous interferon, methotrexate, or radiation therapy may be considered.8

In addition to aiding in the prompt diagnosis and treatment of MF/SS in SoC patients, our findings may be used to better assess the extent of disease and distinguish between active MF/SS lesions vs xerosis cutis or residual dyschromia from previously treated lesions. It is important to note that these morphologic features must be taken into account with a complete history and work-up. The differential diagnosis of MF/SS includes conditions such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and drug reactions, which may have similar morphology in SoC.19

Limitations of our study include the single-center design and the use of photographs instead of in-person examination; however, our cutaneous lymphoma clinic serves a diverse patient population, and our 3 reviewers rated the photographs independently. Discussion amongst the reviewers to address discrepancies was only required for 5 photographs, indicating the high inter-reviewer reliability. Additionally, the original purpose of FST was to assess for the propensity of the skin to burn when undergoing phototherapy, not to serve as a marker for skin color. We recommend trainees and clinicians be mindful about the purpose of FST and to use inclusive language (eg, using the terms skin irritation, skin tenderness, or skin becoming darker from the sun instead of tanning) when determining FST in darker-skinned individuals.20 Future directions include examining if certain treatments are associated with prolonged dyschromia.

Conclusion

In our single-institution retrospective study, we found differences in the morphologic presentation of MF/SS in SoC patients vs non-SoC patients. While erythema is a common feature in non-SoC patients, clinical features of hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and silver hue should be carefully evaluated in the diagnosis of MF/SS in SoC patients. Knowledge of the heterogenous presentation of MF/SS in patients with SoC allows for expedited diagnosis and treatment, leading to better clinical outcomes. Valuable resources, including Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color, the Skin of Color Society, and VisualDx educate providers on how dermatologic conditions present in darker skin types. However, there is still work to be done to enhance diversity in educational resources in order to provide equitable care to patients of all skin types.

- Korgavkar K, Xiong M, Weinstock M. Changing incidence trends of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1295-1299. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5526

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.E1-E16; quiz 221-222. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.049

- Tull RZ, Kerby E, Subash JJ, et al. Ethnic skin centers in the United States: where are we in 2020?. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1757-1759. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.054

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.084

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Shobajo MT, et al. Skin of color representation in medical education: an analysis of popular preparatory materials used for United States medical licensing examinations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:773-775. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.112

- Montgomery SN, Elbuluk N. A quantitative analysis of research publications focused on the top chief complaints in skin of color patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:241-242. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.031

- Hinds GA, Heald P. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:359-375; quiz 376-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.031

- Ardigó M, Borroni G, Muscardin L, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Caucasian patients: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:264-270. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00907-1

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Updated October 8, 2021. Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.html

- Taylor SC, Kyei A. Defining skin of color. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Huang AH, Kwatra SG, Khanna R, et al. Racial disparities in the clinical presentation and prognosis of patients with mycosis fungoides. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111:633-639. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.08.006

- Kim YH, Jensen RA, Watanabe GL, et al. Clinical stage IA (limited patch and plaque) mycosis fungoides. a long-term outcome analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1309-1313.

- Scarisbrick JJ, Prince HM, Vermeer MH, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma international consortium study of outcome in advanced stages of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: effect of specific prognostic markers on survival and development of a prognostic model. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3766-3773. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.7142

- Nath SK, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Poorer prognosis of African-American patients with mycosis fungoides: an analysis of the SEER dataset, 1988 to 2008. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:419-423. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2013.12.018

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x

- Poladian K, De Souza B, McMichael AJ. Atopic dermatitis in adolescents with skin of color. Cutis. 2019;104:164-168.

- Yones SS, Palmer RA, Garibaldinos TT, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy of psoralen-UV-A therapy vs narrowband UV-B therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:836-842. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.7.836

- Currimbhoy S, Pandya AG. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

- Korgavkar K, Xiong M, Weinstock M. Changing incidence trends of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1295-1299. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5526

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.E1-E16; quiz 221-222. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.049

- Tull RZ, Kerby E, Subash JJ, et al. Ethnic skin centers in the United States: where are we in 2020?. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1757-1759. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.054

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.084

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Shobajo MT, et al. Skin of color representation in medical education: an analysis of popular preparatory materials used for United States medical licensing examinations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:773-775. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.112

- Montgomery SN, Elbuluk N. A quantitative analysis of research publications focused on the top chief complaints in skin of color patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:241-242. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.031

- Hinds GA, Heald P. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:359-375; quiz 376-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.031

- Ardigó M, Borroni G, Muscardin L, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Caucasian patients: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:264-270. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00907-1

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. United States Census Bureau website. Updated October 8, 2021. Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.html

- Taylor SC, Kyei A. Defining skin of color. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Huang AH, Kwatra SG, Khanna R, et al. Racial disparities in the clinical presentation and prognosis of patients with mycosis fungoides. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111:633-639. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.08.006

- Kim YH, Jensen RA, Watanabe GL, et al. Clinical stage IA (limited patch and plaque) mycosis fungoides. a long-term outcome analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1309-1313.

- Scarisbrick JJ, Prince HM, Vermeer MH, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma international consortium study of outcome in advanced stages of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: effect of specific prognostic markers on survival and development of a prognostic model. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3766-3773. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.7142

- Nath SK, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Poorer prognosis of African-American patients with mycosis fungoides: an analysis of the SEER dataset, 1988 to 2008. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:419-423. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2013.12.018

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x

- Poladian K, De Souza B, McMichael AJ. Atopic dermatitis in adolescents with skin of color. Cutis. 2019;104:164-168.

- Yones SS, Palmer RA, Garibaldinos TT, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy of psoralen-UV-A therapy vs narrowband UV-B therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:836-842. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.7.836

- Currimbhoy S, Pandya AG. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al, eds. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be familiar with the variable morphology of mycosis fungoides (MF)/Sézary syndrome (SS) exhibited by patients of all skin types to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment.

- Patients with skin of color (SoC)(Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI) with MF/SS are more likely than non-SoC patients (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) to present with hyperpigmentation, a silver hue, and lichenification, whereas non-SoC patients commonly present with erythema and poikiloderma.