User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

Rethink urologic cancer treatment in the era of COVID-19

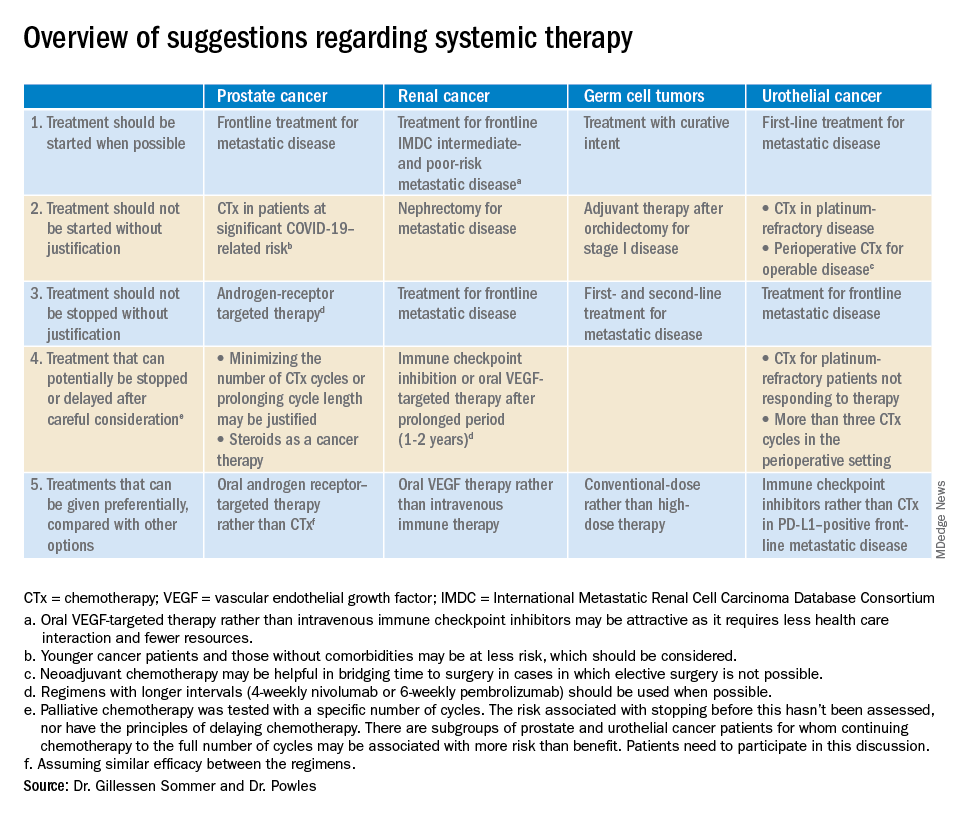

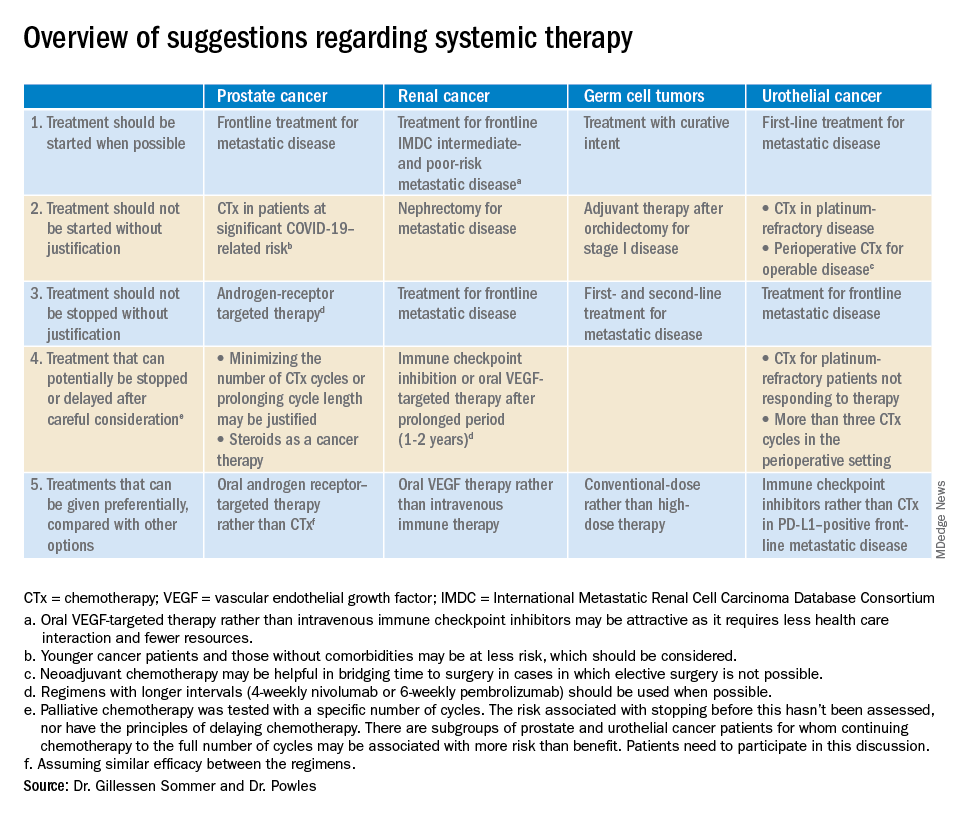

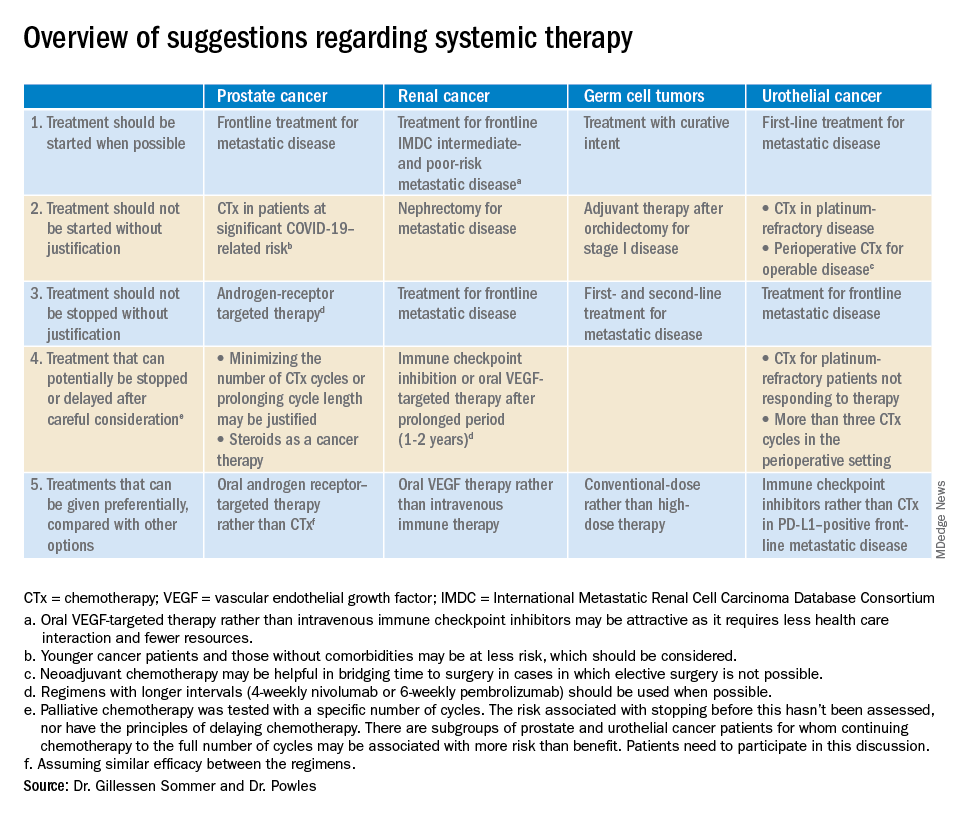

according to an editorial set to be published in European Urology.

“Regimens with a clear survival advantage should be prioritized, with curative treatments remaining mandatory,” wrote Silke Gillessen Sommer, MD, of Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana in Bellizona, Switzerland, and Thomas Powles, MD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London.

However, it may be appropriate to stop or delay therapies with modest or unproven survival benefits. “Delaying the start of therapy ... is an appropriate measure for many of the therapies in urology cancer,” they wrote.

Timely recommendations for oncologists

The COVID-19 pandemic is limiting resources for cancer, noted Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urological oncologist and assistant professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was asked for his thoughts about the editorial.

Oncologists and oncology nurses are being shifted to care for COVID-19 patients, space once devoted to cancer care is being repurposed for the pandemic, and personal protective equipment needed to prepare chemotherapies is in short supply.

Meanwhile, cancer patients are at increased risk of dying from the virus (Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-7), so there’s a need to minimize their contact with the health care system to protect them from nosocomial infection, and a need to keep their immune system as strong as possible to fight it off.

To help cancer patients fight off infection and keep them out of the hospital, the editorialists recommended growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics after chemotherapy, palliative therapies at doses that avoid febrile neutropenia, discontinuing steroids or at least reducing their doses, and avoiding bisphosphonates if they involve potential COVID-19 exposure in medical facilities.

The advice in the editorial mirrors many of the discussions going on right now at the University of Michigan, Dr. Reichert said, and perhaps other oncology services across the United States.

It will come down to how severe the pandemic becomes locally, but he said it seems likely “a lot of us are going to be wearing a different hat for a while.”

Patients who have symptoms from a growing tumor will likely take precedence at the university, but treatment might be postponed until after COVID-19 peaks if tumors don’t affect quality of life. Also, bladder cancer surgery will probably remain urgent “because the longer you wait, the worse the outcomes,” but perhaps not prostate and kidney cancer surgery, where delay is safer, Dr. Reichert said.

Prostate/renal cancers and germ cell tumors

The editorialists noted that oral androgen receptor therapy should be preferred over chemotherapy for prostate cancer. Dr. Reichert explained that’s because androgen blockade is effective, requires less contact with health care providers, and doesn’t suppress the immune system or tie up hospital resources as much as chemotherapy. “In the world we are in right now, oral pills are a better choice,” he said.

The editorialists recommended against both nephrectomy for metastatic renal cancer and adjuvant therapy after orchidectomy for stage 1 germ cell tumors for similar reasons, and also because there’s minimal evidence of benefit.

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested considering a break from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and oral vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) for renal cancer patients who have been on them a year or two. It’s something that would be considered even under normal circumstances, Dr. Reichert explained, but it’s more urgent now to keep people out of the hospital. VEGFs should also be prioritized over ICIs; they have similar efficacy in renal cancer, but VEGFs are a pill.

They also called for oncologists to favor conventional-dose treatments for germ cell tumors over high-dose treatments, meaning bone marrow transplants or high-intensity chemotherapy. Amid a pandemic, the preference is for options “that don’t require a hospital bed,” Dr. Reichert said.

Urothelial cancer

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested not starting or continuing second-line chemotherapies in urothelial cancer patients refractory to first-line platinum-based therapies. The chance they will respond to second-line options is low, perhaps around 10%. That might have been enough before the pandemic, but it’s less justified amid resource shortages and the risk of COVID-19 in the infusion suite, Dr. Reichert explained.

Along the same lines, they also suggested reconsidering perioperative chemotherapy for urothelial cancer, and, if it’s still a go, recommended against going past three cycles, as the benefits in both scenarios are likely marginal. However, if COVID-19 cancels surgeries, neoadjuvant therapy might be the right – and only – call, according to the editorialists.

They recommended prioritizing ICIs over chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). PD-L1–positive patients have a good chance of responding, and ICIs don’t suppress the immune system.

“Chemotherapy still has a slightly higher percent response, but right now, this is a better choice for” PD-L1-positive patients, Dr. Reichert said.

Dr. Gillessen Sommer and Dr. Powles disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Reichert has no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillessen Sommer S, Powles T. “Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Eur Urol. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/eururo/EURUROL-D-20-00382-1585928967060.pdf.

according to an editorial set to be published in European Urology.

“Regimens with a clear survival advantage should be prioritized, with curative treatments remaining mandatory,” wrote Silke Gillessen Sommer, MD, of Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana in Bellizona, Switzerland, and Thomas Powles, MD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London.

However, it may be appropriate to stop or delay therapies with modest or unproven survival benefits. “Delaying the start of therapy ... is an appropriate measure for many of the therapies in urology cancer,” they wrote.

Timely recommendations for oncologists

The COVID-19 pandemic is limiting resources for cancer, noted Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urological oncologist and assistant professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was asked for his thoughts about the editorial.

Oncologists and oncology nurses are being shifted to care for COVID-19 patients, space once devoted to cancer care is being repurposed for the pandemic, and personal protective equipment needed to prepare chemotherapies is in short supply.

Meanwhile, cancer patients are at increased risk of dying from the virus (Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-7), so there’s a need to minimize their contact with the health care system to protect them from nosocomial infection, and a need to keep their immune system as strong as possible to fight it off.

To help cancer patients fight off infection and keep them out of the hospital, the editorialists recommended growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics after chemotherapy, palliative therapies at doses that avoid febrile neutropenia, discontinuing steroids or at least reducing their doses, and avoiding bisphosphonates if they involve potential COVID-19 exposure in medical facilities.

The advice in the editorial mirrors many of the discussions going on right now at the University of Michigan, Dr. Reichert said, and perhaps other oncology services across the United States.

It will come down to how severe the pandemic becomes locally, but he said it seems likely “a lot of us are going to be wearing a different hat for a while.”

Patients who have symptoms from a growing tumor will likely take precedence at the university, but treatment might be postponed until after COVID-19 peaks if tumors don’t affect quality of life. Also, bladder cancer surgery will probably remain urgent “because the longer you wait, the worse the outcomes,” but perhaps not prostate and kidney cancer surgery, where delay is safer, Dr. Reichert said.

Prostate/renal cancers and germ cell tumors

The editorialists noted that oral androgen receptor therapy should be preferred over chemotherapy for prostate cancer. Dr. Reichert explained that’s because androgen blockade is effective, requires less contact with health care providers, and doesn’t suppress the immune system or tie up hospital resources as much as chemotherapy. “In the world we are in right now, oral pills are a better choice,” he said.

The editorialists recommended against both nephrectomy for metastatic renal cancer and adjuvant therapy after orchidectomy for stage 1 germ cell tumors for similar reasons, and also because there’s minimal evidence of benefit.

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested considering a break from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and oral vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) for renal cancer patients who have been on them a year or two. It’s something that would be considered even under normal circumstances, Dr. Reichert explained, but it’s more urgent now to keep people out of the hospital. VEGFs should also be prioritized over ICIs; they have similar efficacy in renal cancer, but VEGFs are a pill.

They also called for oncologists to favor conventional-dose treatments for germ cell tumors over high-dose treatments, meaning bone marrow transplants or high-intensity chemotherapy. Amid a pandemic, the preference is for options “that don’t require a hospital bed,” Dr. Reichert said.

Urothelial cancer

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested not starting or continuing second-line chemotherapies in urothelial cancer patients refractory to first-line platinum-based therapies. The chance they will respond to second-line options is low, perhaps around 10%. That might have been enough before the pandemic, but it’s less justified amid resource shortages and the risk of COVID-19 in the infusion suite, Dr. Reichert explained.

Along the same lines, they also suggested reconsidering perioperative chemotherapy for urothelial cancer, and, if it’s still a go, recommended against going past three cycles, as the benefits in both scenarios are likely marginal. However, if COVID-19 cancels surgeries, neoadjuvant therapy might be the right – and only – call, according to the editorialists.

They recommended prioritizing ICIs over chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). PD-L1–positive patients have a good chance of responding, and ICIs don’t suppress the immune system.

“Chemotherapy still has a slightly higher percent response, but right now, this is a better choice for” PD-L1-positive patients, Dr. Reichert said.

Dr. Gillessen Sommer and Dr. Powles disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Reichert has no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillessen Sommer S, Powles T. “Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Eur Urol. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/eururo/EURUROL-D-20-00382-1585928967060.pdf.

according to an editorial set to be published in European Urology.

“Regimens with a clear survival advantage should be prioritized, with curative treatments remaining mandatory,” wrote Silke Gillessen Sommer, MD, of Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana in Bellizona, Switzerland, and Thomas Powles, MD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London.

However, it may be appropriate to stop or delay therapies with modest or unproven survival benefits. “Delaying the start of therapy ... is an appropriate measure for many of the therapies in urology cancer,” they wrote.

Timely recommendations for oncologists

The COVID-19 pandemic is limiting resources for cancer, noted Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urological oncologist and assistant professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was asked for his thoughts about the editorial.

Oncologists and oncology nurses are being shifted to care for COVID-19 patients, space once devoted to cancer care is being repurposed for the pandemic, and personal protective equipment needed to prepare chemotherapies is in short supply.

Meanwhile, cancer patients are at increased risk of dying from the virus (Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-7), so there’s a need to minimize their contact with the health care system to protect them from nosocomial infection, and a need to keep their immune system as strong as possible to fight it off.

To help cancer patients fight off infection and keep them out of the hospital, the editorialists recommended growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics after chemotherapy, palliative therapies at doses that avoid febrile neutropenia, discontinuing steroids or at least reducing their doses, and avoiding bisphosphonates if they involve potential COVID-19 exposure in medical facilities.

The advice in the editorial mirrors many of the discussions going on right now at the University of Michigan, Dr. Reichert said, and perhaps other oncology services across the United States.

It will come down to how severe the pandemic becomes locally, but he said it seems likely “a lot of us are going to be wearing a different hat for a while.”

Patients who have symptoms from a growing tumor will likely take precedence at the university, but treatment might be postponed until after COVID-19 peaks if tumors don’t affect quality of life. Also, bladder cancer surgery will probably remain urgent “because the longer you wait, the worse the outcomes,” but perhaps not prostate and kidney cancer surgery, where delay is safer, Dr. Reichert said.

Prostate/renal cancers and germ cell tumors

The editorialists noted that oral androgen receptor therapy should be preferred over chemotherapy for prostate cancer. Dr. Reichert explained that’s because androgen blockade is effective, requires less contact with health care providers, and doesn’t suppress the immune system or tie up hospital resources as much as chemotherapy. “In the world we are in right now, oral pills are a better choice,” he said.

The editorialists recommended against both nephrectomy for metastatic renal cancer and adjuvant therapy after orchidectomy for stage 1 germ cell tumors for similar reasons, and also because there’s minimal evidence of benefit.

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested considering a break from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and oral vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) for renal cancer patients who have been on them a year or two. It’s something that would be considered even under normal circumstances, Dr. Reichert explained, but it’s more urgent now to keep people out of the hospital. VEGFs should also be prioritized over ICIs; they have similar efficacy in renal cancer, but VEGFs are a pill.

They also called for oncologists to favor conventional-dose treatments for germ cell tumors over high-dose treatments, meaning bone marrow transplants or high-intensity chemotherapy. Amid a pandemic, the preference is for options “that don’t require a hospital bed,” Dr. Reichert said.

Urothelial cancer

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested not starting or continuing second-line chemotherapies in urothelial cancer patients refractory to first-line platinum-based therapies. The chance they will respond to second-line options is low, perhaps around 10%. That might have been enough before the pandemic, but it’s less justified amid resource shortages and the risk of COVID-19 in the infusion suite, Dr. Reichert explained.

Along the same lines, they also suggested reconsidering perioperative chemotherapy for urothelial cancer, and, if it’s still a go, recommended against going past three cycles, as the benefits in both scenarios are likely marginal. However, if COVID-19 cancels surgeries, neoadjuvant therapy might be the right – and only – call, according to the editorialists.

They recommended prioritizing ICIs over chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). PD-L1–positive patients have a good chance of responding, and ICIs don’t suppress the immune system.

“Chemotherapy still has a slightly higher percent response, but right now, this is a better choice for” PD-L1-positive patients, Dr. Reichert said.

Dr. Gillessen Sommer and Dr. Powles disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Reichert has no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillessen Sommer S, Powles T. “Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Eur Urol. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/eururo/EURUROL-D-20-00382-1585928967060.pdf.

FROM EUROPEAN UROLOGY

FDA grants emergency authorization for first rapid antibody test for COVID-19

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Cellex an emergency use authorization to market a rapid antibody test for COVID-19, the first antibody test released amidst the pandemic.

“It is reasonable to believe that your product may be effective in diagnosing COVID-19,” and “there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative,” the agency said in a letter to Cellex.

A drop of serum, plasma, or whole blood is placed into a well on a small cartridge, and the results are read 15-20 minutes later; lines indicate the presence of IgM, IgG, or both antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Of 128 samples confirmed positive by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in premarket testing, 120 tested positive by IgG, IgM, or both. Of 250 confirmed negative, 239 were negative by the rapid test.

The numbers translated to a positive percent agreement with RT-PCR of 93.8% (95% CI: 88.06-97.26%) and a negative percent agreement of 96.4% (95% CI: 92.26-97.78%), according to labeling.

“Results from antibody testing should not be used as the sole basis to diagnose or exclude SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the labeling states.

Negative results do not rule out infection; antibodies might not have had enough time to form or the virus could have had a minor amino acid mutation in the epitope recognized by the antibodies screened for in the test. False positives can occur due to cross-reactivity with antibodies from previous infections, such as from other coronaviruses.

Labeling suggests that people who test negative should be checked again in a few days, and positive results should be confirmed by other methods. Also, the intensity of the test lines do not necessarily correlate with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers.

As part of its authorization, the FDA waived good manufacturing practice requirements, but stipulated that advertising must state that the test has not been formally approved by the agency.

Testing is limited to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified labs. Positive results are required to be reported to public health authorities. The test can be ordered through Cellex distributors or directly from the company.

IgM antibodies are generally detectable several days after the initial infection, while IgG antibodies take longer. It’s not known how long COVID-19 antibodies persist after the infection has cleared, the agency said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Cellex an emergency use authorization to market a rapid antibody test for COVID-19, the first antibody test released amidst the pandemic.

“It is reasonable to believe that your product may be effective in diagnosing COVID-19,” and “there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative,” the agency said in a letter to Cellex.

A drop of serum, plasma, or whole blood is placed into a well on a small cartridge, and the results are read 15-20 minutes later; lines indicate the presence of IgM, IgG, or both antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Of 128 samples confirmed positive by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in premarket testing, 120 tested positive by IgG, IgM, or both. Of 250 confirmed negative, 239 were negative by the rapid test.

The numbers translated to a positive percent agreement with RT-PCR of 93.8% (95% CI: 88.06-97.26%) and a negative percent agreement of 96.4% (95% CI: 92.26-97.78%), according to labeling.

“Results from antibody testing should not be used as the sole basis to diagnose or exclude SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the labeling states.

Negative results do not rule out infection; antibodies might not have had enough time to form or the virus could have had a minor amino acid mutation in the epitope recognized by the antibodies screened for in the test. False positives can occur due to cross-reactivity with antibodies from previous infections, such as from other coronaviruses.

Labeling suggests that people who test negative should be checked again in a few days, and positive results should be confirmed by other methods. Also, the intensity of the test lines do not necessarily correlate with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers.

As part of its authorization, the FDA waived good manufacturing practice requirements, but stipulated that advertising must state that the test has not been formally approved by the agency.

Testing is limited to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified labs. Positive results are required to be reported to public health authorities. The test can be ordered through Cellex distributors or directly from the company.

IgM antibodies are generally detectable several days after the initial infection, while IgG antibodies take longer. It’s not known how long COVID-19 antibodies persist after the infection has cleared, the agency said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Cellex an emergency use authorization to market a rapid antibody test for COVID-19, the first antibody test released amidst the pandemic.

“It is reasonable to believe that your product may be effective in diagnosing COVID-19,” and “there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative,” the agency said in a letter to Cellex.

A drop of serum, plasma, or whole blood is placed into a well on a small cartridge, and the results are read 15-20 minutes later; lines indicate the presence of IgM, IgG, or both antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Of 128 samples confirmed positive by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in premarket testing, 120 tested positive by IgG, IgM, or both. Of 250 confirmed negative, 239 were negative by the rapid test.

The numbers translated to a positive percent agreement with RT-PCR of 93.8% (95% CI: 88.06-97.26%) and a negative percent agreement of 96.4% (95% CI: 92.26-97.78%), according to labeling.

“Results from antibody testing should not be used as the sole basis to diagnose or exclude SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the labeling states.

Negative results do not rule out infection; antibodies might not have had enough time to form or the virus could have had a minor amino acid mutation in the epitope recognized by the antibodies screened for in the test. False positives can occur due to cross-reactivity with antibodies from previous infections, such as from other coronaviruses.

Labeling suggests that people who test negative should be checked again in a few days, and positive results should be confirmed by other methods. Also, the intensity of the test lines do not necessarily correlate with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers.

As part of its authorization, the FDA waived good manufacturing practice requirements, but stipulated that advertising must state that the test has not been formally approved by the agency.

Testing is limited to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified labs. Positive results are required to be reported to public health authorities. The test can be ordered through Cellex distributors or directly from the company.

IgM antibodies are generally detectable several days after the initial infection, while IgG antibodies take longer. It’s not known how long COVID-19 antibodies persist after the infection has cleared, the agency said.

Skin manifestations are emerging in the coronavirus pandemic

Dermatologists there were pulled from their usual duty to help with the pandemic and looked at what was going on with the skin in 148 COVID-19 inpatients. They excluded 60 who had started new drugs within 15 days to rule out acute drug reactions, then reported what they saw (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387).

Of the 88 COVID-19 patients, 20.5% developed skin manifestations. Eight of the 18 (44%) had skin eruptions at symptom onset, and the rest after hospitalization. Fourteen (78%) had red rashes, three had widespread urticaria, and one had chickenpox-like vesicles. The most commonly affected area was the trunk. Itching was mild or absent, and lesions usually healed up in a few days. Most importantly, skin manifestations did not correlate with disease severity.

These skin manifestations “are similar to cutaneous involvement occurring during common viral infections,” said the author of the report, Sebastiano Recalcati, MD, a dermatologist at Alessandro Manzoni Hospital.

COVID-19 skin manifestations can cloud the diagnosis, according to the authors of another report from Thailand, where the first case of COVID-19 outside of China was reported.

They described a case of a COVID-19 infection in a Bangkok hospital that masqueraded as dengue fever. A person there presented with only a skin rash, petechiae, and a low platelet count, and was diagnosed with Dengue because that’s exactly what it looked like, the authors wrote (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Mar 22. pii: S0190-9622[20]30454-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036).

The correct diagnosis, COVID-19, was made at a tertiary care center after the patient was admitted with respiratory problems.

“There is a possibility that a COVID-19 patient might initially present with a skin rash that can be misdiagnosed as another common disease. ... The practitioner should recognize the possibility that the patient might have only a skin rash” at first, said the lead author of that report, Beuy Joob, PhD, of the Sanitation1 Medical Academic Center, Bangkok, and a coauthor.

There are similar reports in the United States, too. “Many have wondered if COVID-19 presents with any particular skin changes. The answer is yes,” said Randy Jacobs, MD, an assistant clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, Riverside, who also has a private practice in southern California.

“COVID-19 can feature signs of small blood vessel occlusion. These can be petechiae or tiny bruises, and transient livedoid eruptions,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Jacobs had a 67-year-old patient who presented with a low fever, nasal congestion, postnasal drip, and a wet cough but no shortness of breath. It looked like a common cold. But a week later, the man had a nonpruritic blanching livedoid vascular eruption on his right anterior thigh, and blood in his urine, and he felt weak. The vascular eruption and bloody urine resolved in 24 hours, but the COVID-19 test came back positive and his cough became dry and hacking, and the weakness persisted. He’s in a hospital now and on oxygen, but not ventilated so far.

“Another dermatologist friend of mine also reported a similar transient COVID-19 unilateral livedoid eruption,” Dr. Jacobs said.

It suggests vaso-occlusion. Whether it’s neurogenic, microthrombotic, or immune complex mediated is unknown, but it’s “a skin finding that can help clinicians as they work up their patients with COVID-19 symptoms,” he noted.

Dr. Jacobs and the authors of the studies had no disclosures.

Dermatologists there were pulled from their usual duty to help with the pandemic and looked at what was going on with the skin in 148 COVID-19 inpatients. They excluded 60 who had started new drugs within 15 days to rule out acute drug reactions, then reported what they saw (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387).

Of the 88 COVID-19 patients, 20.5% developed skin manifestations. Eight of the 18 (44%) had skin eruptions at symptom onset, and the rest after hospitalization. Fourteen (78%) had red rashes, three had widespread urticaria, and one had chickenpox-like vesicles. The most commonly affected area was the trunk. Itching was mild or absent, and lesions usually healed up in a few days. Most importantly, skin manifestations did not correlate with disease severity.

These skin manifestations “are similar to cutaneous involvement occurring during common viral infections,” said the author of the report, Sebastiano Recalcati, MD, a dermatologist at Alessandro Manzoni Hospital.

COVID-19 skin manifestations can cloud the diagnosis, according to the authors of another report from Thailand, where the first case of COVID-19 outside of China was reported.

They described a case of a COVID-19 infection in a Bangkok hospital that masqueraded as dengue fever. A person there presented with only a skin rash, petechiae, and a low platelet count, and was diagnosed with Dengue because that’s exactly what it looked like, the authors wrote (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Mar 22. pii: S0190-9622[20]30454-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036).

The correct diagnosis, COVID-19, was made at a tertiary care center after the patient was admitted with respiratory problems.

“There is a possibility that a COVID-19 patient might initially present with a skin rash that can be misdiagnosed as another common disease. ... The practitioner should recognize the possibility that the patient might have only a skin rash” at first, said the lead author of that report, Beuy Joob, PhD, of the Sanitation1 Medical Academic Center, Bangkok, and a coauthor.

There are similar reports in the United States, too. “Many have wondered if COVID-19 presents with any particular skin changes. The answer is yes,” said Randy Jacobs, MD, an assistant clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, Riverside, who also has a private practice in southern California.

“COVID-19 can feature signs of small blood vessel occlusion. These can be petechiae or tiny bruises, and transient livedoid eruptions,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Jacobs had a 67-year-old patient who presented with a low fever, nasal congestion, postnasal drip, and a wet cough but no shortness of breath. It looked like a common cold. But a week later, the man had a nonpruritic blanching livedoid vascular eruption on his right anterior thigh, and blood in his urine, and he felt weak. The vascular eruption and bloody urine resolved in 24 hours, but the COVID-19 test came back positive and his cough became dry and hacking, and the weakness persisted. He’s in a hospital now and on oxygen, but not ventilated so far.

“Another dermatologist friend of mine also reported a similar transient COVID-19 unilateral livedoid eruption,” Dr. Jacobs said.

It suggests vaso-occlusion. Whether it’s neurogenic, microthrombotic, or immune complex mediated is unknown, but it’s “a skin finding that can help clinicians as they work up their patients with COVID-19 symptoms,” he noted.

Dr. Jacobs and the authors of the studies had no disclosures.

Dermatologists there were pulled from their usual duty to help with the pandemic and looked at what was going on with the skin in 148 COVID-19 inpatients. They excluded 60 who had started new drugs within 15 days to rule out acute drug reactions, then reported what they saw (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387).

Of the 88 COVID-19 patients, 20.5% developed skin manifestations. Eight of the 18 (44%) had skin eruptions at symptom onset, and the rest after hospitalization. Fourteen (78%) had red rashes, three had widespread urticaria, and one had chickenpox-like vesicles. The most commonly affected area was the trunk. Itching was mild or absent, and lesions usually healed up in a few days. Most importantly, skin manifestations did not correlate with disease severity.

These skin manifestations “are similar to cutaneous involvement occurring during common viral infections,” said the author of the report, Sebastiano Recalcati, MD, a dermatologist at Alessandro Manzoni Hospital.

COVID-19 skin manifestations can cloud the diagnosis, according to the authors of another report from Thailand, where the first case of COVID-19 outside of China was reported.

They described a case of a COVID-19 infection in a Bangkok hospital that masqueraded as dengue fever. A person there presented with only a skin rash, petechiae, and a low platelet count, and was diagnosed with Dengue because that’s exactly what it looked like, the authors wrote (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Mar 22. pii: S0190-9622[20]30454-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036).

The correct diagnosis, COVID-19, was made at a tertiary care center after the patient was admitted with respiratory problems.

“There is a possibility that a COVID-19 patient might initially present with a skin rash that can be misdiagnosed as another common disease. ... The practitioner should recognize the possibility that the patient might have only a skin rash” at first, said the lead author of that report, Beuy Joob, PhD, of the Sanitation1 Medical Academic Center, Bangkok, and a coauthor.

There are similar reports in the United States, too. “Many have wondered if COVID-19 presents with any particular skin changes. The answer is yes,” said Randy Jacobs, MD, an assistant clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, Riverside, who also has a private practice in southern California.

“COVID-19 can feature signs of small blood vessel occlusion. These can be petechiae or tiny bruises, and transient livedoid eruptions,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Jacobs had a 67-year-old patient who presented with a low fever, nasal congestion, postnasal drip, and a wet cough but no shortness of breath. It looked like a common cold. But a week later, the man had a nonpruritic blanching livedoid vascular eruption on his right anterior thigh, and blood in his urine, and he felt weak. The vascular eruption and bloody urine resolved in 24 hours, but the COVID-19 test came back positive and his cough became dry and hacking, and the weakness persisted. He’s in a hospital now and on oxygen, but not ventilated so far.

“Another dermatologist friend of mine also reported a similar transient COVID-19 unilateral livedoid eruption,” Dr. Jacobs said.

It suggests vaso-occlusion. Whether it’s neurogenic, microthrombotic, or immune complex mediated is unknown, but it’s “a skin finding that can help clinicians as they work up their patients with COVID-19 symptoms,” he noted.

Dr. Jacobs and the authors of the studies had no disclosures.

Vascular biomarkers predict pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis

Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients developed pulmonary hypertension (PH) in a prospective cohort of 300 subjects.

However, the associations with PH were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor (PlGF), the sensitivity for future PH was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve (AUC) 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 (sFlt1) – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an AUC of 0.61.

Adding PlGF and sFlt1 elevations to carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, and percent forced vital capacity to predict PH increased the AUC modestly, from 0.72 to 0.77.

The data suggest, perhaps, an early warning system for PH. “Once vascular biomarkers are observed to be elevated, the frequency of other screening tests (e.g., NT-proBNP, DLCO) may be increased in a more cost-effective approach,” wrote investigators led by rheumatologist Christopher Mecoli, MD, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“In the end, the authors did not overstate the case and cautiously recommended that using biomarkers might be useful in the future. The finding that when there are increased numbers of abnormalities of vascular markers, there would be an increased probability of pulmonary hypertension, makes sense.” However, “this was a major fishing expedition, and the data are certainly not sufficient to suggest anything clinical but are of some interest with respect to the general hypothesis,” said rheumatologist Daniel Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, when asked for comment.

The subjects were followed for at least 5 years and had no evidence of PH at study entry. Levels of P1GF, sFlt-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), soluble endoglin, and endostatin were assessed at baseline and at regular intervals thereafter. A total of 46 patients (15%) developed PH after a mean of 3 years.

Risk of PH was associated with baseline elevations of HGF (hazard ratio, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.24-3.17; P = .004); sFlt1 (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.29-7.14; P = .011); and PlGF (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.32-5.69; P = .007).

Just 2 of 25 patients (8%) with no biomarkers elevated at baseline developed PH versus 12 of 29 (42%) with all five elevated. That translated to a dose-response relationship, with each additional elevated biomarker increasing the risk of PH by 78% (95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004).

“There [was] no consistent trend of increasing biomarker levels over time as patients approach[ed] a diagnosis of [PH]. ... Serial testing may have value in patients with early disease to first detect elevations in biomarkers,” but “once elevated, the utility of serially monitoring appears low,” the investigators wrote.

It’s not surprising that “a higher number of elevated biomarkers relating to vascular dysfunction would correspond to a higher risk of PH,” the team wrote. However, “while these biomarkers hold promise in the risk stratification of SSc patients, many more vascular molecules exist which may have similar or greater value.”

There was no substantial correlation between any biomarker and disease duration, age at enrollment, or age at diagnosis, and no significant difference in biomarker level based on patient comorbidities. No biomarker was significantly associated with medication use at cohort entry, and none were significantly associated with the risk of ischemic digital lesions.

The majority of patients were white women. At enrollment, the average age was 52 years, and subjects had SSc for a mean of 10 years.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures were not reported.

SOURCE: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients developed pulmonary hypertension (PH) in a prospective cohort of 300 subjects.

However, the associations with PH were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor (PlGF), the sensitivity for future PH was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve (AUC) 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 (sFlt1) – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an AUC of 0.61.

Adding PlGF and sFlt1 elevations to carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, and percent forced vital capacity to predict PH increased the AUC modestly, from 0.72 to 0.77.

The data suggest, perhaps, an early warning system for PH. “Once vascular biomarkers are observed to be elevated, the frequency of other screening tests (e.g., NT-proBNP, DLCO) may be increased in a more cost-effective approach,” wrote investigators led by rheumatologist Christopher Mecoli, MD, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“In the end, the authors did not overstate the case and cautiously recommended that using biomarkers might be useful in the future. The finding that when there are increased numbers of abnormalities of vascular markers, there would be an increased probability of pulmonary hypertension, makes sense.” However, “this was a major fishing expedition, and the data are certainly not sufficient to suggest anything clinical but are of some interest with respect to the general hypothesis,” said rheumatologist Daniel Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, when asked for comment.

The subjects were followed for at least 5 years and had no evidence of PH at study entry. Levels of P1GF, sFlt-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), soluble endoglin, and endostatin were assessed at baseline and at regular intervals thereafter. A total of 46 patients (15%) developed PH after a mean of 3 years.

Risk of PH was associated with baseline elevations of HGF (hazard ratio, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.24-3.17; P = .004); sFlt1 (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.29-7.14; P = .011); and PlGF (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.32-5.69; P = .007).

Just 2 of 25 patients (8%) with no biomarkers elevated at baseline developed PH versus 12 of 29 (42%) with all five elevated. That translated to a dose-response relationship, with each additional elevated biomarker increasing the risk of PH by 78% (95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004).

“There [was] no consistent trend of increasing biomarker levels over time as patients approach[ed] a diagnosis of [PH]. ... Serial testing may have value in patients with early disease to first detect elevations in biomarkers,” but “once elevated, the utility of serially monitoring appears low,” the investigators wrote.

It’s not surprising that “a higher number of elevated biomarkers relating to vascular dysfunction would correspond to a higher risk of PH,” the team wrote. However, “while these biomarkers hold promise in the risk stratification of SSc patients, many more vascular molecules exist which may have similar or greater value.”

There was no substantial correlation between any biomarker and disease duration, age at enrollment, or age at diagnosis, and no significant difference in biomarker level based on patient comorbidities. No biomarker was significantly associated with medication use at cohort entry, and none were significantly associated with the risk of ischemic digital lesions.

The majority of patients were white women. At enrollment, the average age was 52 years, and subjects had SSc for a mean of 10 years.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures were not reported.

SOURCE: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients developed pulmonary hypertension (PH) in a prospective cohort of 300 subjects.

However, the associations with PH were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor (PlGF), the sensitivity for future PH was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve (AUC) 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 (sFlt1) – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an AUC of 0.61.

Adding PlGF and sFlt1 elevations to carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, and percent forced vital capacity to predict PH increased the AUC modestly, from 0.72 to 0.77.

The data suggest, perhaps, an early warning system for PH. “Once vascular biomarkers are observed to be elevated, the frequency of other screening tests (e.g., NT-proBNP, DLCO) may be increased in a more cost-effective approach,” wrote investigators led by rheumatologist Christopher Mecoli, MD, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“In the end, the authors did not overstate the case and cautiously recommended that using biomarkers might be useful in the future. The finding that when there are increased numbers of abnormalities of vascular markers, there would be an increased probability of pulmonary hypertension, makes sense.” However, “this was a major fishing expedition, and the data are certainly not sufficient to suggest anything clinical but are of some interest with respect to the general hypothesis,” said rheumatologist Daniel Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, when asked for comment.

The subjects were followed for at least 5 years and had no evidence of PH at study entry. Levels of P1GF, sFlt-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), soluble endoglin, and endostatin were assessed at baseline and at regular intervals thereafter. A total of 46 patients (15%) developed PH after a mean of 3 years.

Risk of PH was associated with baseline elevations of HGF (hazard ratio, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.24-3.17; P = .004); sFlt1 (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.29-7.14; P = .011); and PlGF (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.32-5.69; P = .007).

Just 2 of 25 patients (8%) with no biomarkers elevated at baseline developed PH versus 12 of 29 (42%) with all five elevated. That translated to a dose-response relationship, with each additional elevated biomarker increasing the risk of PH by 78% (95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004).

“There [was] no consistent trend of increasing biomarker levels over time as patients approach[ed] a diagnosis of [PH]. ... Serial testing may have value in patients with early disease to first detect elevations in biomarkers,” but “once elevated, the utility of serially monitoring appears low,” the investigators wrote.

It’s not surprising that “a higher number of elevated biomarkers relating to vascular dysfunction would correspond to a higher risk of PH,” the team wrote. However, “while these biomarkers hold promise in the risk stratification of SSc patients, many more vascular molecules exist which may have similar or greater value.”

There was no substantial correlation between any biomarker and disease duration, age at enrollment, or age at diagnosis, and no significant difference in biomarker level based on patient comorbidities. No biomarker was significantly associated with medication use at cohort entry, and none were significantly associated with the risk of ischemic digital lesions.

The majority of patients were white women. At enrollment, the average age was 52 years, and subjects had SSc for a mean of 10 years.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures were not reported.

SOURCE: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis patients developed pulmonary hypertension.

Major finding: The associations with pulmonary hypertension were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor, the sensitivity for future pulmonary hypertension was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an area under the curve of 0.61.

Study details: A prospective cohort of 300 patients

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures weren’t reported.

Source: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

AASLD: Liver transplants should proceed despite COVID-19

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

HIV shortens life expectancy 9 years, healthy life expectancy 16 years

Despite highly effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV still shortens life expectancy by 9 years and healthy life expectancy free of comorbidities 16 years, according to a review of HIV patients and matched controls at Kaiser Permanente facilities in California and the mid-Atlantic states during 2000-2016.

The good news is that starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) when CD4 counts are 500 cells/mm3 or higher closes the mortality gap. People who do so can expect to live into their mid-80s, the same as people without HIV, and the years they can expect to be free of diabetes and cancer is catching up to uninfected people, although the gap for other comorbidities hasn’t changed and the overall comorbidity gap remains 16 years, according to the report, which was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections

“We were excited about finding no difference in lifespan for people starting ART with high CD4 counts, but we were surprised by how wide the gap was for the number of comorbidity free years. Greater attention to comorbidity prevention is needed,” said study lead Julia Marcus, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The team estimated the average number of total and comorbidity-free years of life remaining at age 21 for 39,000 people with HIV who were matched 1:10 with 387,767 uninfected adults by sex, race/ethnicity, year, and medical center.

Overall, adults with HIV could expect to live until they were 77 years old, versus 86 years for people without HIV, during 2014-2016. It’s a large improvement over the 22 year gap during 2000-2003, when the numbers were 59 versus 81 years, respectively, Dr. Marcus reported at the virtual meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but held online this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

But the overall comorbidity gap didn’t budge during 2000-2016. People with HIV during 2014-2016 could expect to be comorbidity free until age 36 years, versus 52 years for the general population, the same 16-year difference during 2000-2003, when the numbers were age 32 versus age 48 years.

During 2014-2016, liver disease came 24 years sooner with HIV, and chronic kidney disease 17 years, chronic lung disease 16 years, cancer 9 years, and diabetes and cancer both 8 years sooner. Early ART didn’t narrow the gap for most comorbidities. Dr. Marcus didn’t address the reasons for the differences, except to note that “smoking rates were definitely higher among people with HIV.”

The results weren’t broken down by sex, but the majority of subjects, 88%, were men. The mean age was 41 years, and about half were white, with most of the rest either black or Hispanic. Transmission was among men who have sex with men in 70% of the cases, heterosexual sex in 20%, and IV drug accounted for the rest. Almost a third of the subjects started ART with CD4 counts at or above 500 cells/mm3.

Dr. Marcus said the results are likely generalizable to most insured people with HIV, but also that comorbidity screening might be higher in the HIV population, which could have affected the results.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Marcus is an adviser for Gilead.

SOURCE: Marcus JL et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 151.

Despite highly effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV still shortens life expectancy by 9 years and healthy life expectancy free of comorbidities 16 years, according to a review of HIV patients and matched controls at Kaiser Permanente facilities in California and the mid-Atlantic states during 2000-2016.

The good news is that starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) when CD4 counts are 500 cells/mm3 or higher closes the mortality gap. People who do so can expect to live into their mid-80s, the same as people without HIV, and the years they can expect to be free of diabetes and cancer is catching up to uninfected people, although the gap for other comorbidities hasn’t changed and the overall comorbidity gap remains 16 years, according to the report, which was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections

“We were excited about finding no difference in lifespan for people starting ART with high CD4 counts, but we were surprised by how wide the gap was for the number of comorbidity free years. Greater attention to comorbidity prevention is needed,” said study lead Julia Marcus, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The team estimated the average number of total and comorbidity-free years of life remaining at age 21 for 39,000 people with HIV who were matched 1:10 with 387,767 uninfected adults by sex, race/ethnicity, year, and medical center.

Overall, adults with HIV could expect to live until they were 77 years old, versus 86 years for people without HIV, during 2014-2016. It’s a large improvement over the 22 year gap during 2000-2003, when the numbers were 59 versus 81 years, respectively, Dr. Marcus reported at the virtual meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but held online this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

But the overall comorbidity gap didn’t budge during 2000-2016. People with HIV during 2014-2016 could expect to be comorbidity free until age 36 years, versus 52 years for the general population, the same 16-year difference during 2000-2003, when the numbers were age 32 versus age 48 years.

During 2014-2016, liver disease came 24 years sooner with HIV, and chronic kidney disease 17 years, chronic lung disease 16 years, cancer 9 years, and diabetes and cancer both 8 years sooner. Early ART didn’t narrow the gap for most comorbidities. Dr. Marcus didn’t address the reasons for the differences, except to note that “smoking rates were definitely higher among people with HIV.”

The results weren’t broken down by sex, but the majority of subjects, 88%, were men. The mean age was 41 years, and about half were white, with most of the rest either black or Hispanic. Transmission was among men who have sex with men in 70% of the cases, heterosexual sex in 20%, and IV drug accounted for the rest. Almost a third of the subjects started ART with CD4 counts at or above 500 cells/mm3.

Dr. Marcus said the results are likely generalizable to most insured people with HIV, but also that comorbidity screening might be higher in the HIV population, which could have affected the results.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Marcus is an adviser for Gilead.

SOURCE: Marcus JL et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 151.

Despite highly effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV still shortens life expectancy by 9 years and healthy life expectancy free of comorbidities 16 years, according to a review of HIV patients and matched controls at Kaiser Permanente facilities in California and the mid-Atlantic states during 2000-2016.

The good news is that starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) when CD4 counts are 500 cells/mm3 or higher closes the mortality gap. People who do so can expect to live into their mid-80s, the same as people without HIV, and the years they can expect to be free of diabetes and cancer is catching up to uninfected people, although the gap for other comorbidities hasn’t changed and the overall comorbidity gap remains 16 years, according to the report, which was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections

“We were excited about finding no difference in lifespan for people starting ART with high CD4 counts, but we were surprised by how wide the gap was for the number of comorbidity free years. Greater attention to comorbidity prevention is needed,” said study lead Julia Marcus, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The team estimated the average number of total and comorbidity-free years of life remaining at age 21 for 39,000 people with HIV who were matched 1:10 with 387,767 uninfected adults by sex, race/ethnicity, year, and medical center.

Overall, adults with HIV could expect to live until they were 77 years old, versus 86 years for people without HIV, during 2014-2016. It’s a large improvement over the 22 year gap during 2000-2003, when the numbers were 59 versus 81 years, respectively, Dr. Marcus reported at the virtual meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but held online this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

But the overall comorbidity gap didn’t budge during 2000-2016. People with HIV during 2014-2016 could expect to be comorbidity free until age 36 years, versus 52 years for the general population, the same 16-year difference during 2000-2003, when the numbers were age 32 versus age 48 years.

During 2014-2016, liver disease came 24 years sooner with HIV, and chronic kidney disease 17 years, chronic lung disease 16 years, cancer 9 years, and diabetes and cancer both 8 years sooner. Early ART didn’t narrow the gap for most comorbidities. Dr. Marcus didn’t address the reasons for the differences, except to note that “smoking rates were definitely higher among people with HIV.”

The results weren’t broken down by sex, but the majority of subjects, 88%, were men. The mean age was 41 years, and about half were white, with most of the rest either black or Hispanic. Transmission was among men who have sex with men in 70% of the cases, heterosexual sex in 20%, and IV drug accounted for the rest. Almost a third of the subjects started ART with CD4 counts at or above 500 cells/mm3.

Dr. Marcus said the results are likely generalizable to most insured people with HIV, but also that comorbidity screening might be higher in the HIV population, which could have affected the results.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Marcus is an adviser for Gilead.

SOURCE: Marcus JL et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 151.

FROM CROI 2020

Less pain with a cancer drug to treat anal HPV, but it’s expensive

At the end of 6 months of low-dose pomalidomide (Pomalyst), more than half of men who have sex with men had partial or complete clearance of long-standing, grade 3 anal lesions from human papillomavirus, irrespective of HIV status; the number increased to almost two-thirds when they were checked at 12 months, according to a 26-subject study said in video presentation of his research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

“Therapy induced durable and continuous clearance of anal HSIL [high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions]. Further study in HPV-associated premalignancy is warranted to follow up this small, single arm study,” said study lead Mark Polizzotto, MD, PhD, head of the therapeutic and vaccine research program at the Kirby Institute in Sydney.

HPV anal lesions, and subsequent HSIL and progression to anal cancer, are prevalent among men who have sex with men. The risk increases with chronic lesions and concomitant HIV infection.

Pomalidomide is potentially a less painful alternative to options such as freezing and laser ablation, and it may have a lower rate of recurrence, but it’s expensive. Copays range upward from $5,000 for a month supply, according to GoodRx. Celgene, the maker of the drug, offers financial assistance.

Pomalidomide is a derivative of thalidomide that’s approved for multiple myeloma and also has shown effect against a viral lesion associated with HIV, Kaposi sarcoma. The drug is a T-cell activator, and since T-cell activation also is key to spontaneous anal HSIL clearance, Dr. Polizzotto and team wanted to take a look to see if it could help, he said.

The men in the study were at high risk for progression to anal cancer. With a median lesion duration of more than 3 years, and at least one case out past 7 years, spontaneous clearance wasn’t in the cards. The lesions were all grade 3 HSIL, which means severe dysplasia, and more than half of the subjects had HPV genotype 16, and the rest had other risky genotypes. Ten subjects also had HIV, which also increases the risk of anal cancer.

Pomalidomide was given in back-to-back cycles for 6 months, each consisting of 2 mg orally for 3 weeks, then 1 week off, along with a thrombolytic, usually aspirin, given the black box warning of blood clots. The dose was half the 5-mg cycle for Kaposi’s.

The overall response rate – complete clearance or a partial clearance of at least a 50% on high-resolution anoscopy – was 50% at 6 months (12/24), including four complete responses (4/15, 27%) in subjects without HIV, as well as four in the HIV group (4/9, 44%).

On follow-up at month 12, “we saw something we did not expect. Strikingly, with no additional therapy in the interim, we saw a deepening of response in a number of subjects.” The overall response rate climbed to 63% (15/24), including 33% complete response in the HIV-free group (5/15) and HIV-positive group (3/9).

Some did lose their response in the interim, however, and the study team is working to figure out if it was do to a recurrence or a new infection.

A general pattern of immune activation on treatment, including increased systemic CD4+ T-cell responses to HPV during therapy, supported the investigator’s hunch of an immunologic mechanism of action, Dr. Polizzotto said.

There were four instances of grade 3 neutropenia over eight treatment cycles, and one possibly related angina attack, but other than that, adverse reactions were generally mild and self-limited, mostly to grade 1 or 2 neutropenia, constipation, fatigue, and rash, with no idiosyncratic reactions in the HIV group or loss of viral suppression, and no discontinuations because of side effects.

The men in the study were aged 40-50 years, with a median age of 54 years; all but one were white. The median lesion involved a quarter of the anal ring, but sometimes more than half.

The work was funded by the Cancer Institute of New South Wales, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and Celgene. Dr. Polizzotto disclosed patents with Celgene and research funding from the company.

SOURCE: Polizzotto M et al. CROI 2020. Abstract 70

At the end of 6 months of low-dose pomalidomide (Pomalyst), more than half of men who have sex with men had partial or complete clearance of long-standing, grade 3 anal lesions from human papillomavirus, irrespective of HIV status; the number increased to almost two-thirds when they were checked at 12 months, according to a 26-subject study said in video presentation of his research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

“Therapy induced durable and continuous clearance of anal HSIL [high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions]. Further study in HPV-associated premalignancy is warranted to follow up this small, single arm study,” said study lead Mark Polizzotto, MD, PhD, head of the therapeutic and vaccine research program at the Kirby Institute in Sydney.

HPV anal lesions, and subsequent HSIL and progression to anal cancer, are prevalent among men who have sex with men. The risk increases with chronic lesions and concomitant HIV infection.

Pomalidomide is potentially a less painful alternative to options such as freezing and laser ablation, and it may have a lower rate of recurrence, but it’s expensive. Copays range upward from $5,000 for a month supply, according to GoodRx. Celgene, the maker of the drug, offers financial assistance.

Pomalidomide is a derivative of thalidomide that’s approved for multiple myeloma and also has shown effect against a viral lesion associated with HIV, Kaposi sarcoma. The drug is a T-cell activator, and since T-cell activation also is key to spontaneous anal HSIL clearance, Dr. Polizzotto and team wanted to take a look to see if it could help, he said.