User login

Multimodal approach is state of the art for ulcerated infantile hemangiomas

CHICAGO –

About 16% of infantile hemangiomas become ulcerated at some point during their proliferative phase, said Kate Puttgen, MD, during a talk at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

One clinical clue to picking up an infantile hemangioma (IH) that’s destined to ulcerate is an early grayish to white discoloration of the lesion, said Dr. Puttgen, chief of the division of pediatric dermatology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

“Multimodal therapy is an absolute necessity” in treating an ulcerated IH, said Dr. Puttgen. Using an “all hands on deck” approach – a combination of topical and systemic modalities – can help bring the lesion under control.

Beta-blockers are first-line therapy to manage complicated IHs, with propranolol yielding a 98% response rate for all complicated IHs in the literature, said Dr. Puttgen.

Propranolol can decrease the volume and color of IHs and speed involution, in part by its ability to continue working after the proliferative growth phase of an IH. It’s also been shown to reduce the need for surgery in nasal IH, and it’s well tolerated, she added.

Evidence-based therapies for ulcerated hemangiomas include systemic propranolol at 1-3 mg/kg per day. That protocol will result in a healed ulcer within 2-6 weeks in most of the published case series, Dr. Puttgen noted.

Topical timolol also has evidence supporting its use for an ulcerated IH, and it has been found generally safe. In one study of 30 patients with IH, she said, three had mild adverse events consisting of sleep disturbance, diarrhea, and acrocyanosis. Another study reported success when brimonidine 0.2% and timolol 0.5% were used together. It’s possible, said Dr. Puttgen, that there’s a synergistic effect when combining the selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonist effect of brimonidine with timolol, which provides nonselective beta adrenergic blockade. However, she said, there has been an isolated report of brimonidine toxicity.

The ulcerated IHs need wound care, Dr. Puttgen added, with barrier creams and dressings. Pain management should be considered, because an ulcerated IH may have a large, friable, bleeding area. Pulsed-dye laser can also be a useful treatment modality for an ulcerating IH.

Going beyond the treatments for which the evidence is strongest and moving into more “state-of-the-art” treatments, “there may be a niche role for oral corticosteroids” as combination systemic therapy with propranolol, Dr. Puttgen said.

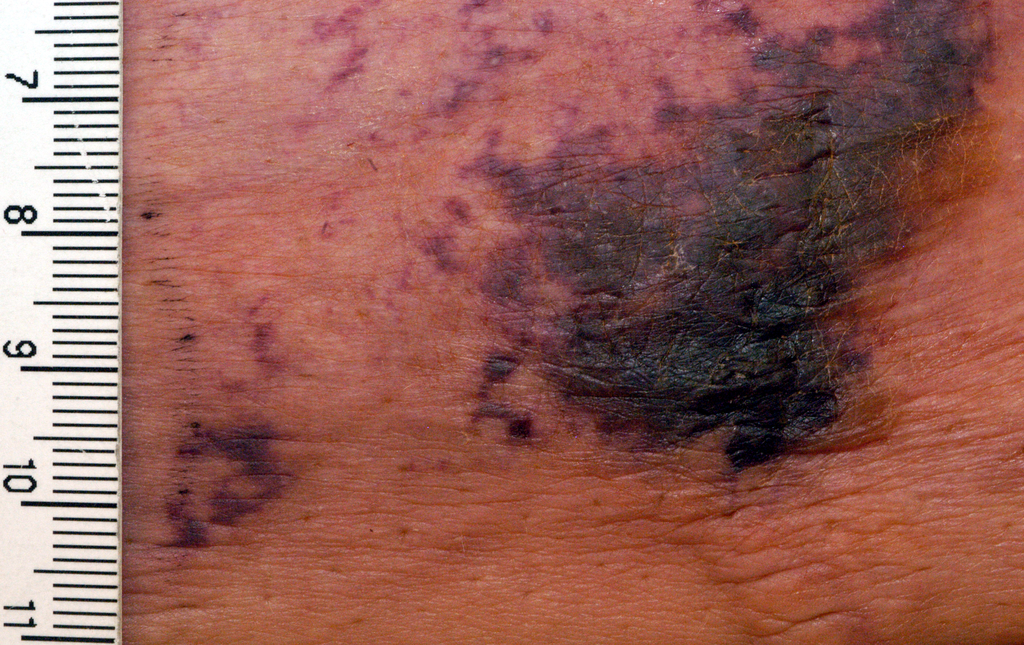

She shared images from a recently published report, in which she’s the senior author, showing the progression of an ulcerated IH. The hemangioma had received wound care and pulsed-dye laser treatment, and the infant was started on systemic propranolol. After 2 weeks, the IH had decreased significantly in volume, but the ulcerated area had actually increased. With the addition of oral corticosteroids, there was a reduction in ulceration after 2 weeks; and after 5 weeks of prednisolone, “the ulceration resolved without rebound,” said Dr. Puttgen. The corticosteroid was then tapered and propranolol was continued for an additional 2 months, then tapered. By 10 months, the IH had almost completely resolved (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Apr;176[4]:1064-7).

If a corticosteroid is added to propranolol, there may be benefit to a slower propranolol dose, Dr. Puttgen said. She suggests an altered dosing schedule, beginning with 1 mg/kg per day in two or three divided doses. Then, over a period of 2-7 days, the total daily dose can be increased to 1.5 mg/kg per day. Bumping the dose up to 2 mg/kg per day or higher should not happen until after 2 weeks at the reduced dosing schedule, she explained.

Dr. Puttgen disclosed that she is on the advisory board and has received honoraria from Pierre Fabre Dermatologie.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO –

About 16% of infantile hemangiomas become ulcerated at some point during their proliferative phase, said Kate Puttgen, MD, during a talk at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

One clinical clue to picking up an infantile hemangioma (IH) that’s destined to ulcerate is an early grayish to white discoloration of the lesion, said Dr. Puttgen, chief of the division of pediatric dermatology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

“Multimodal therapy is an absolute necessity” in treating an ulcerated IH, said Dr. Puttgen. Using an “all hands on deck” approach – a combination of topical and systemic modalities – can help bring the lesion under control.

Beta-blockers are first-line therapy to manage complicated IHs, with propranolol yielding a 98% response rate for all complicated IHs in the literature, said Dr. Puttgen.

Propranolol can decrease the volume and color of IHs and speed involution, in part by its ability to continue working after the proliferative growth phase of an IH. It’s also been shown to reduce the need for surgery in nasal IH, and it’s well tolerated, she added.

Evidence-based therapies for ulcerated hemangiomas include systemic propranolol at 1-3 mg/kg per day. That protocol will result in a healed ulcer within 2-6 weeks in most of the published case series, Dr. Puttgen noted.

Topical timolol also has evidence supporting its use for an ulcerated IH, and it has been found generally safe. In one study of 30 patients with IH, she said, three had mild adverse events consisting of sleep disturbance, diarrhea, and acrocyanosis. Another study reported success when brimonidine 0.2% and timolol 0.5% were used together. It’s possible, said Dr. Puttgen, that there’s a synergistic effect when combining the selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonist effect of brimonidine with timolol, which provides nonselective beta adrenergic blockade. However, she said, there has been an isolated report of brimonidine toxicity.

The ulcerated IHs need wound care, Dr. Puttgen added, with barrier creams and dressings. Pain management should be considered, because an ulcerated IH may have a large, friable, bleeding area. Pulsed-dye laser can also be a useful treatment modality for an ulcerating IH.

Going beyond the treatments for which the evidence is strongest and moving into more “state-of-the-art” treatments, “there may be a niche role for oral corticosteroids” as combination systemic therapy with propranolol, Dr. Puttgen said.

She shared images from a recently published report, in which she’s the senior author, showing the progression of an ulcerated IH. The hemangioma had received wound care and pulsed-dye laser treatment, and the infant was started on systemic propranolol. After 2 weeks, the IH had decreased significantly in volume, but the ulcerated area had actually increased. With the addition of oral corticosteroids, there was a reduction in ulceration after 2 weeks; and after 5 weeks of prednisolone, “the ulceration resolved without rebound,” said Dr. Puttgen. The corticosteroid was then tapered and propranolol was continued for an additional 2 months, then tapered. By 10 months, the IH had almost completely resolved (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Apr;176[4]:1064-7).

If a corticosteroid is added to propranolol, there may be benefit to a slower propranolol dose, Dr. Puttgen said. She suggests an altered dosing schedule, beginning with 1 mg/kg per day in two or three divided doses. Then, over a period of 2-7 days, the total daily dose can be increased to 1.5 mg/kg per day. Bumping the dose up to 2 mg/kg per day or higher should not happen until after 2 weeks at the reduced dosing schedule, she explained.

Dr. Puttgen disclosed that she is on the advisory board and has received honoraria from Pierre Fabre Dermatologie.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO –

About 16% of infantile hemangiomas become ulcerated at some point during their proliferative phase, said Kate Puttgen, MD, during a talk at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

One clinical clue to picking up an infantile hemangioma (IH) that’s destined to ulcerate is an early grayish to white discoloration of the lesion, said Dr. Puttgen, chief of the division of pediatric dermatology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

“Multimodal therapy is an absolute necessity” in treating an ulcerated IH, said Dr. Puttgen. Using an “all hands on deck” approach – a combination of topical and systemic modalities – can help bring the lesion under control.

Beta-blockers are first-line therapy to manage complicated IHs, with propranolol yielding a 98% response rate for all complicated IHs in the literature, said Dr. Puttgen.

Propranolol can decrease the volume and color of IHs and speed involution, in part by its ability to continue working after the proliferative growth phase of an IH. It’s also been shown to reduce the need for surgery in nasal IH, and it’s well tolerated, she added.

Evidence-based therapies for ulcerated hemangiomas include systemic propranolol at 1-3 mg/kg per day. That protocol will result in a healed ulcer within 2-6 weeks in most of the published case series, Dr. Puttgen noted.

Topical timolol also has evidence supporting its use for an ulcerated IH, and it has been found generally safe. In one study of 30 patients with IH, she said, three had mild adverse events consisting of sleep disturbance, diarrhea, and acrocyanosis. Another study reported success when brimonidine 0.2% and timolol 0.5% were used together. It’s possible, said Dr. Puttgen, that there’s a synergistic effect when combining the selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonist effect of brimonidine with timolol, which provides nonselective beta adrenergic blockade. However, she said, there has been an isolated report of brimonidine toxicity.

The ulcerated IHs need wound care, Dr. Puttgen added, with barrier creams and dressings. Pain management should be considered, because an ulcerated IH may have a large, friable, bleeding area. Pulsed-dye laser can also be a useful treatment modality for an ulcerating IH.

Going beyond the treatments for which the evidence is strongest and moving into more “state-of-the-art” treatments, “there may be a niche role for oral corticosteroids” as combination systemic therapy with propranolol, Dr. Puttgen said.

She shared images from a recently published report, in which she’s the senior author, showing the progression of an ulcerated IH. The hemangioma had received wound care and pulsed-dye laser treatment, and the infant was started on systemic propranolol. After 2 weeks, the IH had decreased significantly in volume, but the ulcerated area had actually increased. With the addition of oral corticosteroids, there was a reduction in ulceration after 2 weeks; and after 5 weeks of prednisolone, “the ulceration resolved without rebound,” said Dr. Puttgen. The corticosteroid was then tapered and propranolol was continued for an additional 2 months, then tapered. By 10 months, the IH had almost completely resolved (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Apr;176[4]:1064-7).

If a corticosteroid is added to propranolol, there may be benefit to a slower propranolol dose, Dr. Puttgen said. She suggests an altered dosing schedule, beginning with 1 mg/kg per day in two or three divided doses. Then, over a period of 2-7 days, the total daily dose can be increased to 1.5 mg/kg per day. Bumping the dose up to 2 mg/kg per day or higher should not happen until after 2 weeks at the reduced dosing schedule, she explained.

Dr. Puttgen disclosed that she is on the advisory board and has received honoraria from Pierre Fabre Dermatologie.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCPD 2017

Pregnancy not a barrier to providing cutaneous surgery

NEW YORK – For some dermatologists, surgical care of the pregnant patient represents an area of uncertainty. But with few exceptions, dermatologists can continue with business as usual for their pregnant patients, according to Keith Harrigill, MD.

Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist who previously was a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, delineated the safe zones of dermatologic surgery in these patients at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 2% of pregnant women will require nonobstetric surgery and about 75,000 pregnant women in the United States will have surgery annually, he said. Appendectomies and other emergent abdominal surgery account for a large proportion of these cases; dermatologic surgeries are not included in these figures, and cutaneous procedures in pregnant women are not usually tracked. The literature on dermatologic treatments during pregnancy is “scant,” said Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist in private practice in Birmingham, Ala.

However, it’s known that one-third of women with melanoma are of childbearing age, and melanoma accounts for 8% of the malignancies diagnosed during pregnancy, with a rate estimated at 0.14 to 2.8 per 1,000 live births, he said.

Since some women will have to address potentially serious skin issues during pregnancy, what’s safe, and what isn’t? Dr. Harrigill said that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has provided guidance with an April 2017 opinion, prepared in conjunction with the American Society for Anesthesia, on nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:777-8).

The opinion primarily focuses on major surgery. “What we do – cutaneous surgeries – they consider to be minor surgery,” he said. But even with major procedures, the good news is that “there’s no increase in birth defects in fetal exposure to anesthesia at any age,” he noted.

Dr. Harrigill’s approach, which conforms to the general guidance provided by the opinion, is to think of dermatologic procedures in three categories: urgent, nonurgent, and elective. Urgent procedures might include biopsying and treating a lesion suspicious for melanoma or an aggressive nonmelanoma skin cancer, or controlling a friable, bleeding pyogenic granuloma. “Do these right away,” he said.

Nonurgent procedures, such as treatment of a nodular basal cell carcinoma, should be done during the second trimester, when possible. Elective procedures, such as a scar excision, should be deferred until after delivery.

Dermatologists can almost always achieve adequate pain control with local anesthesia alone, said Dr. Harrigill, pointing out that local anesthesia is “the safest known way to give anesthesia during pregnancy.”

However, when thinking about even a remote risk of teratogenesis, it’s important to understand that fetal organogenesis occurs from day 15 to day 56, and that before 15 days, adverse events are limited to spontaneous abortion. So it’s particularly important to avoid teratogenic medications during the first 2 months of gestation, Dr. Harrigill said.

Part of the concern, he noted, is that it’s ethically problematic to perform large randomized trials in pregnant women, so the guidelines regarding surgery and medication safety are drawn from retrospective studies, registries, meta-analyses, and expert consensus.

Still, according to the ACOG guidelines, “a pregnant woman should never be denied indicated surgery, regardless of trimester.”

There’s no reason to risk delaying a diagnosis of malignancy in a pregnant patient, Dr. Harrigill said. “My dermatologic surgery approach is to biopsy anything that is clinically suspicious for malignancy, at any gestational age.”

When performing biopsies in pregnant patients, he uses the same protocol as he uses with any other patient. Skin preparation can be done with either isopropyl alcohol or chlorhexidine. Some practitioners avoid using povidone iodine because of a theoretical risk of fetal hypothyroidism.

For anesthesia, Dr. Harrigill noted that lidocaine is generally considered safe in pregnancy. He is also comfortable using epinephrine, despite the theoretical concern of uterine artery spasm, for which “studies are lacking.” The relatively minute amount of epinephrine used in dermatologic anesthesia, he said, is not likely to have an impact on such a large vessel.

Prilocaine is generally safe, and combination creams with prilocaine are fine to use, he said. Diphenhydramine is also safe to use. However, he advised avoiding long-acting anesthetic agents, such as mepivacaine and bupivacaine.

His advice regarding sedation? “Don’t do it.” Dr. Harrigill said he doesn’t use sedation in the office for his nonpregnant patients, either.

Before about 20 weeks of pregnancy, Dr. Harrigill said not to worry about how the patient is positioned. But after that, the lateral decubitus position is best because it keeps the gravid uterus from compressing the great vessels.

“Pregnant women are prone to fainting due to progesterone-mediated vasodilation,” he said. Dermatologists can work with their office staff to keep these patients well hydrated, and make sure they get in and out of chairs and off exam tables slowly.

No changes are needed in excision or suturing techniques. Because cicatrization is delayed in pregnant women, Dr. Harrigill uses longer-lasting absorbable sutures with high tensile strength, especially when performing procedures on the trunk or abdomen. This means that his closures will use delayed-absorption epidermal sutures with running nylon pull-through subcuticular sutures as well. He will leave these in for 5-7 days longer than usual.

Pregnant women are not at a higher risk of infection than the general population, so he follows the standard procedures here as well. If an antibiotic is indicated, penicillin, a cephalosporin, azithromycin, and erythromycin base are all logical choices.

To be avoided are sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, which carries a risk of feta hyperbilirubinemia, especially when given in the second trimester; doxycycline and tetracycline, which can cause permanent brown discoloration of the teeth; and fluoroquinolones, which have been associated with cartilage defects.

For analgesia, acetaminophen is an option. Ibuprofen and salicylates should be avoided, especially at the end of pregnancy when their administration is associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and, possibly, placental abruption, Dr. Harrigill noted.

However, short-term use of opioids is generally considered safe for the fetus. If larger doses are given just before delivery, the neonate may experience respiratory depression. This scenario is unlikely to be faced by the dermatologist, noted Dr. Harrigill. “I use these without reservation” in terms of fetal risk, he said.

Collaboration is key when caring for pregnant patients, said Dr. Harrigill, who recommends consulting the obstetrician of record for any procedures other than a simple biopsy or shave removal.

Dr. Harrigill reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – For some dermatologists, surgical care of the pregnant patient represents an area of uncertainty. But with few exceptions, dermatologists can continue with business as usual for their pregnant patients, according to Keith Harrigill, MD.

Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist who previously was a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, delineated the safe zones of dermatologic surgery in these patients at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 2% of pregnant women will require nonobstetric surgery and about 75,000 pregnant women in the United States will have surgery annually, he said. Appendectomies and other emergent abdominal surgery account for a large proportion of these cases; dermatologic surgeries are not included in these figures, and cutaneous procedures in pregnant women are not usually tracked. The literature on dermatologic treatments during pregnancy is “scant,” said Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist in private practice in Birmingham, Ala.

However, it’s known that one-third of women with melanoma are of childbearing age, and melanoma accounts for 8% of the malignancies diagnosed during pregnancy, with a rate estimated at 0.14 to 2.8 per 1,000 live births, he said.

Since some women will have to address potentially serious skin issues during pregnancy, what’s safe, and what isn’t? Dr. Harrigill said that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has provided guidance with an April 2017 opinion, prepared in conjunction with the American Society for Anesthesia, on nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:777-8).

The opinion primarily focuses on major surgery. “What we do – cutaneous surgeries – they consider to be minor surgery,” he said. But even with major procedures, the good news is that “there’s no increase in birth defects in fetal exposure to anesthesia at any age,” he noted.

Dr. Harrigill’s approach, which conforms to the general guidance provided by the opinion, is to think of dermatologic procedures in three categories: urgent, nonurgent, and elective. Urgent procedures might include biopsying and treating a lesion suspicious for melanoma or an aggressive nonmelanoma skin cancer, or controlling a friable, bleeding pyogenic granuloma. “Do these right away,” he said.

Nonurgent procedures, such as treatment of a nodular basal cell carcinoma, should be done during the second trimester, when possible. Elective procedures, such as a scar excision, should be deferred until after delivery.

Dermatologists can almost always achieve adequate pain control with local anesthesia alone, said Dr. Harrigill, pointing out that local anesthesia is “the safest known way to give anesthesia during pregnancy.”

However, when thinking about even a remote risk of teratogenesis, it’s important to understand that fetal organogenesis occurs from day 15 to day 56, and that before 15 days, adverse events are limited to spontaneous abortion. So it’s particularly important to avoid teratogenic medications during the first 2 months of gestation, Dr. Harrigill said.

Part of the concern, he noted, is that it’s ethically problematic to perform large randomized trials in pregnant women, so the guidelines regarding surgery and medication safety are drawn from retrospective studies, registries, meta-analyses, and expert consensus.

Still, according to the ACOG guidelines, “a pregnant woman should never be denied indicated surgery, regardless of trimester.”

There’s no reason to risk delaying a diagnosis of malignancy in a pregnant patient, Dr. Harrigill said. “My dermatologic surgery approach is to biopsy anything that is clinically suspicious for malignancy, at any gestational age.”

When performing biopsies in pregnant patients, he uses the same protocol as he uses with any other patient. Skin preparation can be done with either isopropyl alcohol or chlorhexidine. Some practitioners avoid using povidone iodine because of a theoretical risk of fetal hypothyroidism.

For anesthesia, Dr. Harrigill noted that lidocaine is generally considered safe in pregnancy. He is also comfortable using epinephrine, despite the theoretical concern of uterine artery spasm, for which “studies are lacking.” The relatively minute amount of epinephrine used in dermatologic anesthesia, he said, is not likely to have an impact on such a large vessel.

Prilocaine is generally safe, and combination creams with prilocaine are fine to use, he said. Diphenhydramine is also safe to use. However, he advised avoiding long-acting anesthetic agents, such as mepivacaine and bupivacaine.

His advice regarding sedation? “Don’t do it.” Dr. Harrigill said he doesn’t use sedation in the office for his nonpregnant patients, either.

Before about 20 weeks of pregnancy, Dr. Harrigill said not to worry about how the patient is positioned. But after that, the lateral decubitus position is best because it keeps the gravid uterus from compressing the great vessels.

“Pregnant women are prone to fainting due to progesterone-mediated vasodilation,” he said. Dermatologists can work with their office staff to keep these patients well hydrated, and make sure they get in and out of chairs and off exam tables slowly.

No changes are needed in excision or suturing techniques. Because cicatrization is delayed in pregnant women, Dr. Harrigill uses longer-lasting absorbable sutures with high tensile strength, especially when performing procedures on the trunk or abdomen. This means that his closures will use delayed-absorption epidermal sutures with running nylon pull-through subcuticular sutures as well. He will leave these in for 5-7 days longer than usual.

Pregnant women are not at a higher risk of infection than the general population, so he follows the standard procedures here as well. If an antibiotic is indicated, penicillin, a cephalosporin, azithromycin, and erythromycin base are all logical choices.

To be avoided are sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, which carries a risk of feta hyperbilirubinemia, especially when given in the second trimester; doxycycline and tetracycline, which can cause permanent brown discoloration of the teeth; and fluoroquinolones, which have been associated with cartilage defects.

For analgesia, acetaminophen is an option. Ibuprofen and salicylates should be avoided, especially at the end of pregnancy when their administration is associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and, possibly, placental abruption, Dr. Harrigill noted.

However, short-term use of opioids is generally considered safe for the fetus. If larger doses are given just before delivery, the neonate may experience respiratory depression. This scenario is unlikely to be faced by the dermatologist, noted Dr. Harrigill. “I use these without reservation” in terms of fetal risk, he said.

Collaboration is key when caring for pregnant patients, said Dr. Harrigill, who recommends consulting the obstetrician of record for any procedures other than a simple biopsy or shave removal.

Dr. Harrigill reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – For some dermatologists, surgical care of the pregnant patient represents an area of uncertainty. But with few exceptions, dermatologists can continue with business as usual for their pregnant patients, according to Keith Harrigill, MD.

Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist who previously was a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, delineated the safe zones of dermatologic surgery in these patients at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 2% of pregnant women will require nonobstetric surgery and about 75,000 pregnant women in the United States will have surgery annually, he said. Appendectomies and other emergent abdominal surgery account for a large proportion of these cases; dermatologic surgeries are not included in these figures, and cutaneous procedures in pregnant women are not usually tracked. The literature on dermatologic treatments during pregnancy is “scant,” said Dr. Harrigill, a dermatologist in private practice in Birmingham, Ala.

However, it’s known that one-third of women with melanoma are of childbearing age, and melanoma accounts for 8% of the malignancies diagnosed during pregnancy, with a rate estimated at 0.14 to 2.8 per 1,000 live births, he said.

Since some women will have to address potentially serious skin issues during pregnancy, what’s safe, and what isn’t? Dr. Harrigill said that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has provided guidance with an April 2017 opinion, prepared in conjunction with the American Society for Anesthesia, on nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:777-8).

The opinion primarily focuses on major surgery. “What we do – cutaneous surgeries – they consider to be minor surgery,” he said. But even with major procedures, the good news is that “there’s no increase in birth defects in fetal exposure to anesthesia at any age,” he noted.

Dr. Harrigill’s approach, which conforms to the general guidance provided by the opinion, is to think of dermatologic procedures in three categories: urgent, nonurgent, and elective. Urgent procedures might include biopsying and treating a lesion suspicious for melanoma or an aggressive nonmelanoma skin cancer, or controlling a friable, bleeding pyogenic granuloma. “Do these right away,” he said.

Nonurgent procedures, such as treatment of a nodular basal cell carcinoma, should be done during the second trimester, when possible. Elective procedures, such as a scar excision, should be deferred until after delivery.

Dermatologists can almost always achieve adequate pain control with local anesthesia alone, said Dr. Harrigill, pointing out that local anesthesia is “the safest known way to give anesthesia during pregnancy.”

However, when thinking about even a remote risk of teratogenesis, it’s important to understand that fetal organogenesis occurs from day 15 to day 56, and that before 15 days, adverse events are limited to spontaneous abortion. So it’s particularly important to avoid teratogenic medications during the first 2 months of gestation, Dr. Harrigill said.

Part of the concern, he noted, is that it’s ethically problematic to perform large randomized trials in pregnant women, so the guidelines regarding surgery and medication safety are drawn from retrospective studies, registries, meta-analyses, and expert consensus.

Still, according to the ACOG guidelines, “a pregnant woman should never be denied indicated surgery, regardless of trimester.”

There’s no reason to risk delaying a diagnosis of malignancy in a pregnant patient, Dr. Harrigill said. “My dermatologic surgery approach is to biopsy anything that is clinically suspicious for malignancy, at any gestational age.”

When performing biopsies in pregnant patients, he uses the same protocol as he uses with any other patient. Skin preparation can be done with either isopropyl alcohol or chlorhexidine. Some practitioners avoid using povidone iodine because of a theoretical risk of fetal hypothyroidism.

For anesthesia, Dr. Harrigill noted that lidocaine is generally considered safe in pregnancy. He is also comfortable using epinephrine, despite the theoretical concern of uterine artery spasm, for which “studies are lacking.” The relatively minute amount of epinephrine used in dermatologic anesthesia, he said, is not likely to have an impact on such a large vessel.

Prilocaine is generally safe, and combination creams with prilocaine are fine to use, he said. Diphenhydramine is also safe to use. However, he advised avoiding long-acting anesthetic agents, such as mepivacaine and bupivacaine.

His advice regarding sedation? “Don’t do it.” Dr. Harrigill said he doesn’t use sedation in the office for his nonpregnant patients, either.

Before about 20 weeks of pregnancy, Dr. Harrigill said not to worry about how the patient is positioned. But after that, the lateral decubitus position is best because it keeps the gravid uterus from compressing the great vessels.

“Pregnant women are prone to fainting due to progesterone-mediated vasodilation,” he said. Dermatologists can work with their office staff to keep these patients well hydrated, and make sure they get in and out of chairs and off exam tables slowly.

No changes are needed in excision or suturing techniques. Because cicatrization is delayed in pregnant women, Dr. Harrigill uses longer-lasting absorbable sutures with high tensile strength, especially when performing procedures on the trunk or abdomen. This means that his closures will use delayed-absorption epidermal sutures with running nylon pull-through subcuticular sutures as well. He will leave these in for 5-7 days longer than usual.

Pregnant women are not at a higher risk of infection than the general population, so he follows the standard procedures here as well. If an antibiotic is indicated, penicillin, a cephalosporin, azithromycin, and erythromycin base are all logical choices.

To be avoided are sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, which carries a risk of feta hyperbilirubinemia, especially when given in the second trimester; doxycycline and tetracycline, which can cause permanent brown discoloration of the teeth; and fluoroquinolones, which have been associated with cartilage defects.

For analgesia, acetaminophen is an option. Ibuprofen and salicylates should be avoided, especially at the end of pregnancy when their administration is associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, and, possibly, placental abruption, Dr. Harrigill noted.

However, short-term use of opioids is generally considered safe for the fetus. If larger doses are given just before delivery, the neonate may experience respiratory depression. This scenario is unlikely to be faced by the dermatologist, noted Dr. Harrigill. “I use these without reservation” in terms of fetal risk, he said.

Collaboration is key when caring for pregnant patients, said Dr. Harrigill, who recommends consulting the obstetrician of record for any procedures other than a simple biopsy or shave removal.

Dr. Harrigill reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

Clues to rosacea in patients of skin of color

NEW YORK – A middle-aged patient with Fitzpatrick type V skin comes to the office with a 10-year history of “breakouts” on her face. When asked about topical treatments, she reports that “everything burns or stings,” and says she just has very sensitive skin. What could this be?

Rosacea may often be missed in skin of color, said Dr. Alexis, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s reportedly rare in darker skin types, especially in blacks,” and as a result, dermatologists and patients alike have a low index of suspicion for the diagnosis, he noted.

Also, rosacea looks different on darker skin than it does on lighter skin, which is featured in much of the dermatology teaching material. “In richly pigmented [Fitzpatrick] type VI skin, the erythema of rosacea can be masked,” said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and at Mount Sinai West, both in New York.

Dermatologists, in this case, may have to do some detective work: looking at the distribution of the lesions, thinking about trigger factors from the patient history, and noting the lack of comedones – although the patient has “pimples.” Patient complaints that they are sensitive to almost all topical products and experience stinging with “everything” is another very good clue that the patient may have rosacea.

Keep rosacea on the differential for this picture, advised Dr. Alexis. In skin of color, “rosacea may not be as rare as previously thought – less common, maybe – but not rare.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – A middle-aged patient with Fitzpatrick type V skin comes to the office with a 10-year history of “breakouts” on her face. When asked about topical treatments, she reports that “everything burns or stings,” and says she just has very sensitive skin. What could this be?

Rosacea may often be missed in skin of color, said Dr. Alexis, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s reportedly rare in darker skin types, especially in blacks,” and as a result, dermatologists and patients alike have a low index of suspicion for the diagnosis, he noted.

Also, rosacea looks different on darker skin than it does on lighter skin, which is featured in much of the dermatology teaching material. “In richly pigmented [Fitzpatrick] type VI skin, the erythema of rosacea can be masked,” said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and at Mount Sinai West, both in New York.

Dermatologists, in this case, may have to do some detective work: looking at the distribution of the lesions, thinking about trigger factors from the patient history, and noting the lack of comedones – although the patient has “pimples.” Patient complaints that they are sensitive to almost all topical products and experience stinging with “everything” is another very good clue that the patient may have rosacea.

Keep rosacea on the differential for this picture, advised Dr. Alexis. In skin of color, “rosacea may not be as rare as previously thought – less common, maybe – but not rare.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – A middle-aged patient with Fitzpatrick type V skin comes to the office with a 10-year history of “breakouts” on her face. When asked about topical treatments, she reports that “everything burns or stings,” and says she just has very sensitive skin. What could this be?

Rosacea may often be missed in skin of color, said Dr. Alexis, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s reportedly rare in darker skin types, especially in blacks,” and as a result, dermatologists and patients alike have a low index of suspicion for the diagnosis, he noted.

Also, rosacea looks different on darker skin than it does on lighter skin, which is featured in much of the dermatology teaching material. “In richly pigmented [Fitzpatrick] type VI skin, the erythema of rosacea can be masked,” said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and at Mount Sinai West, both in New York.

Dermatologists, in this case, may have to do some detective work: looking at the distribution of the lesions, thinking about trigger factors from the patient history, and noting the lack of comedones – although the patient has “pimples.” Patient complaints that they are sensitive to almost all topical products and experience stinging with “everything” is another very good clue that the patient may have rosacea.

Keep rosacea on the differential for this picture, advised Dr. Alexis. In skin of color, “rosacea may not be as rare as previously thought – less common, maybe – but not rare.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

Acne-associated hyperpigmentation an important consideration in patients with skin of color

NEW YORK – When treating patients with skin of color for acne, treatment goals may vary from those of patients with lighter skin, according to Andrew F. Alexis, MD.

For example, in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, the desired treatment outcome is not only resolution of acne, but also resolution of hyperpigmentation, said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York, N.Y.

“Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is often the driving force for the dermatology consult” in individuals with skin of color, Dr. Alexis said at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “They may be just as concerned about their dark spots as underlying acne,” he noted, citing a study that he coauthored (J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014 Jul;7[7]:19-31).

In the study – a survey of patients with acne to determine which treatment outcomes were most important – 41.6% of the nonwhite female patients reported that clearance of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was the most important goal, compared with 8.4% of white female respondents (P less than .0001).

It’s important to avoid undertreating patients, especially darker-skinned patients, where ongoing subclinical inflammation may contribute to hyperpigmentation. Even in lesions that appear grossly noninflamed, biopsies may find histological evidence of inflammation, with increased T-cell infiltration of the pilosebaceous units, Dr. Alexis said.

However, there’s always a balancing act in determining how aggressively to treat patients, he added. Dermatologists have to be aware of the risk of hypertrophic scar formation in darker-skinned individuals, especially in truncal areas.

When addressing the acne, step one is to aggressively reduce acne-associated inflammation to reduce potential sequelae. This can be done with any of a number of agents, such as retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, dapsone, azelaic acid, and even intralesional corticosteroid injections, he said.

“All agents have been considered in darker skin types,” he said, noting that “retinoids are particularly important because they can also treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.” Tretinoin 0.1% cream and tazarotene 0.1% cream are both good choices, he added.

Adapalene in a fixed combination with benzoyl peroxide has been studied in darker-skinned patients, with no difference in tolerability or higher incidence of pigmentary sequelae than in lighter-skinned patients, he pointed out.

Dapsone 5% and 7.5% have also been studied in patients with darker skin, and both concentrations showed comparable results for safety and efficacy.

The thinking about second-line agents can shift a bit when treating acne in darker skin. For example, azelaic acid as a 20% cream or 15% gel can be a good choice, and can be helpful in treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but azelaic acid is “not as good an antiacne agent as retinoids,” Dr. Alexis said.

Patients should understand that any of these choices are primarily acne-directed treatments, to be deployed over the first 3-6 months of treatment. Then, beginning at about the 3-month mark and continuing for up to a year, hyperpigmentation can be addressed. “Really emphasize the duration of treatment,” when treating hyperpigmentation, Dr. Alexis advised.

Once the acne is under control and hyperpigmentation can be assessed on its own, dermatologists can consider whether bleaching agents are appropriate. “Should they be used? If so, how?” he asked.

Bleaching agents can be effective, said Dr. Alexis, who recommends lesion-directed rather than broad-field therapy, unless there are many larger hyperpigmented macules. “The more common scenario is smaller, more distributed lesions,” he said. “Superficial chemical peels, if used with caution, can be a good adjunct,” to bleaching agents, he added.

Coming down the road are topical nitric oxide preparations, which he said are looking good for darker skin in clinical trials.

“The key to great outcomes is to initiate a combination regimen that targets inflammation and reduces hyperpigmentation,” said Dr. Alexis. Then, he advised, minimize irritation but don’t undertreat, consider adjunctive chemical peels, and above all, “set realistic timeline expectations.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – When treating patients with skin of color for acne, treatment goals may vary from those of patients with lighter skin, according to Andrew F. Alexis, MD.

For example, in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, the desired treatment outcome is not only resolution of acne, but also resolution of hyperpigmentation, said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York, N.Y.

“Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is often the driving force for the dermatology consult” in individuals with skin of color, Dr. Alexis said at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “They may be just as concerned about their dark spots as underlying acne,” he noted, citing a study that he coauthored (J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014 Jul;7[7]:19-31).

In the study – a survey of patients with acne to determine which treatment outcomes were most important – 41.6% of the nonwhite female patients reported that clearance of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was the most important goal, compared with 8.4% of white female respondents (P less than .0001).

It’s important to avoid undertreating patients, especially darker-skinned patients, where ongoing subclinical inflammation may contribute to hyperpigmentation. Even in lesions that appear grossly noninflamed, biopsies may find histological evidence of inflammation, with increased T-cell infiltration of the pilosebaceous units, Dr. Alexis said.

However, there’s always a balancing act in determining how aggressively to treat patients, he added. Dermatologists have to be aware of the risk of hypertrophic scar formation in darker-skinned individuals, especially in truncal areas.

When addressing the acne, step one is to aggressively reduce acne-associated inflammation to reduce potential sequelae. This can be done with any of a number of agents, such as retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, dapsone, azelaic acid, and even intralesional corticosteroid injections, he said.

“All agents have been considered in darker skin types,” he said, noting that “retinoids are particularly important because they can also treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.” Tretinoin 0.1% cream and tazarotene 0.1% cream are both good choices, he added.

Adapalene in a fixed combination with benzoyl peroxide has been studied in darker-skinned patients, with no difference in tolerability or higher incidence of pigmentary sequelae than in lighter-skinned patients, he pointed out.

Dapsone 5% and 7.5% have also been studied in patients with darker skin, and both concentrations showed comparable results for safety and efficacy.

The thinking about second-line agents can shift a bit when treating acne in darker skin. For example, azelaic acid as a 20% cream or 15% gel can be a good choice, and can be helpful in treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but azelaic acid is “not as good an antiacne agent as retinoids,” Dr. Alexis said.

Patients should understand that any of these choices are primarily acne-directed treatments, to be deployed over the first 3-6 months of treatment. Then, beginning at about the 3-month mark and continuing for up to a year, hyperpigmentation can be addressed. “Really emphasize the duration of treatment,” when treating hyperpigmentation, Dr. Alexis advised.

Once the acne is under control and hyperpigmentation can be assessed on its own, dermatologists can consider whether bleaching agents are appropriate. “Should they be used? If so, how?” he asked.

Bleaching agents can be effective, said Dr. Alexis, who recommends lesion-directed rather than broad-field therapy, unless there are many larger hyperpigmented macules. “The more common scenario is smaller, more distributed lesions,” he said. “Superficial chemical peels, if used with caution, can be a good adjunct,” to bleaching agents, he added.

Coming down the road are topical nitric oxide preparations, which he said are looking good for darker skin in clinical trials.

“The key to great outcomes is to initiate a combination regimen that targets inflammation and reduces hyperpigmentation,” said Dr. Alexis. Then, he advised, minimize irritation but don’t undertreat, consider adjunctive chemical peels, and above all, “set realistic timeline expectations.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – When treating patients with skin of color for acne, treatment goals may vary from those of patients with lighter skin, according to Andrew F. Alexis, MD.

For example, in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, the desired treatment outcome is not only resolution of acne, but also resolution of hyperpigmentation, said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York, N.Y.

“Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is often the driving force for the dermatology consult” in individuals with skin of color, Dr. Alexis said at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “They may be just as concerned about their dark spots as underlying acne,” he noted, citing a study that he coauthored (J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014 Jul;7[7]:19-31).

In the study – a survey of patients with acne to determine which treatment outcomes were most important – 41.6% of the nonwhite female patients reported that clearance of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was the most important goal, compared with 8.4% of white female respondents (P less than .0001).

It’s important to avoid undertreating patients, especially darker-skinned patients, where ongoing subclinical inflammation may contribute to hyperpigmentation. Even in lesions that appear grossly noninflamed, biopsies may find histological evidence of inflammation, with increased T-cell infiltration of the pilosebaceous units, Dr. Alexis said.

However, there’s always a balancing act in determining how aggressively to treat patients, he added. Dermatologists have to be aware of the risk of hypertrophic scar formation in darker-skinned individuals, especially in truncal areas.

When addressing the acne, step one is to aggressively reduce acne-associated inflammation to reduce potential sequelae. This can be done with any of a number of agents, such as retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, dapsone, azelaic acid, and even intralesional corticosteroid injections, he said.

“All agents have been considered in darker skin types,” he said, noting that “retinoids are particularly important because they can also treat postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.” Tretinoin 0.1% cream and tazarotene 0.1% cream are both good choices, he added.

Adapalene in a fixed combination with benzoyl peroxide has been studied in darker-skinned patients, with no difference in tolerability or higher incidence of pigmentary sequelae than in lighter-skinned patients, he pointed out.

Dapsone 5% and 7.5% have also been studied in patients with darker skin, and both concentrations showed comparable results for safety and efficacy.

The thinking about second-line agents can shift a bit when treating acne in darker skin. For example, azelaic acid as a 20% cream or 15% gel can be a good choice, and can be helpful in treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but azelaic acid is “not as good an antiacne agent as retinoids,” Dr. Alexis said.

Patients should understand that any of these choices are primarily acne-directed treatments, to be deployed over the first 3-6 months of treatment. Then, beginning at about the 3-month mark and continuing for up to a year, hyperpigmentation can be addressed. “Really emphasize the duration of treatment,” when treating hyperpigmentation, Dr. Alexis advised.

Once the acne is under control and hyperpigmentation can be assessed on its own, dermatologists can consider whether bleaching agents are appropriate. “Should they be used? If so, how?” he asked.

Bleaching agents can be effective, said Dr. Alexis, who recommends lesion-directed rather than broad-field therapy, unless there are many larger hyperpigmented macules. “The more common scenario is smaller, more distributed lesions,” he said. “Superficial chemical peels, if used with caution, can be a good adjunct,” to bleaching agents, he added.

Coming down the road are topical nitric oxide preparations, which he said are looking good for darker skin in clinical trials.

“The key to great outcomes is to initiate a combination regimen that targets inflammation and reduces hyperpigmentation,” said Dr. Alexis. Then, he advised, minimize irritation but don’t undertreat, consider adjunctive chemical peels, and above all, “set realistic timeline expectations.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 SUMMER AAD MEETING

Screening MRI misses Sturge-Weber in babies with port-wine stain

CHICAGO – Screening infants with a port-wine stain for Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) with a magnetic resonance imaging brain scan had a 23% false-negative rate and actually delayed seizure detection, according to a recent study.

When infants with port-wine stains receive a dermatology consult, they may also be screened for SWS by means of MRI and by electroencephalography, particularly if their lesion phenotype puts them at higher risk for SWS. But the accuracy and benefit of the screenings has not been well established, said Michaela Zallmann, MD, the study’s first author. Hemifacial lesions that involve both the forehead and cheek and median lesions that are centered around the facial midline are both considered high-risk lesions.

Dr. Zallmann, a dermatologist at Monash University and the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, and her coinvestigators examined data on 126 patients with facial port-wine stains who came to a laser clinic over a 12-month period. Of these, 32 (25.4%) had a high-risk port-wine stain, and 9 of those 32 (28.1%) had a capillary-venous malformation characteristic of SWS. Of the high-risk patients, 14 received a screening MRI or EEG before having had a first seizure. Of those 14 scans, 1 resulted in a diagnosis of SWS; of the 13 patients with a negative MRI screen, 3 (23.1%) were later found to have SWS when their parents or caregivers detected seizures. Thus, a total of four of the high-risk infants who were screened eventually were diagnosed with SWS.

Of the 18 high-risk patients who did not receive a screening MRI, 3 (16.7%) developed seizures, while 2 (11.1%) were seizure free but developed glaucoma severe enough to require treatment. One patient who was also seizure free developed an autism spectrum disorder.

Two patients who were in the high-risk group received screening EEGs that detected abnormalities that were not yet clinically evident. These included sub-clinical seizures and posterior-quadrant focal slowing. Both of these patients had initial negative screening MRIs.

Scanning early in life, using inappropriate imaging protocols, and having an inexperienced radiologist were all factors associated with a higher probability of false negative screening MRI, according to the researchers’ analysis, which was presented in a poster session at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

All of the false negative MRIs in the study cohort were conducted in infants younger than 9 weeks old. But whether it is useful to reserve imaging for later in infancy is debatable. “While later imaging may have improved sensitivity, 75% of infants with SWS will have already had their first seizure by 12 months of age,” wrote Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues.

Of the infants involved in the study, two of the three patients with false negative scans did not receive a referral to a neurologist, nor did their parents receive seizure education. “False reassurance may delay seizure detection,” Dr. Zallmann said.

For infants with positive MRIs who went on to develop seizures, the mean age of when they experienced their first documented seizure was 10 weeks. For those who did not receive an MRI, the mean age was 14 months, compared with 28 months for patients who had received a false negative MRI.

In discussing the findings, Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues made the point that early referral to a pediatric neurologist is important, especially for infants with the higher-risk port-wine stain patterns of hemifacial and median lesions. Seizure education can help parents detect the often subtle signs of seizures in infants with SWS, which can include staring spells, subtle limb twitching, and lip smacking.

The fact that seizures were detected an average of 14 months later in patients with negative screening MRIs may mean that such subtle signs were missed. “False reassurance may delay the recognition and treatment of seizures and impact neurodevelopmental outcomes,” Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues wrote in the abstract that accompanied the poster.

The study, while small, helps fill in some knowledge gaps, the researchers pointed out; they noted that there is no consensus on what level or type of facial involvement warrants screening, which protocols are best for MRI and EEG, or even whether the screening will improve seizure detection or outcomes.

“Currently there is no evidence that screening improves neurodevelopmental outcomes,” they said. “Conversely, there is a role for early neurological referral, symptom education, and potentially of EEGs in the prevention of complications related to SWS.”

Dr. Zallmann reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Screening infants with a port-wine stain for Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) with a magnetic resonance imaging brain scan had a 23% false-negative rate and actually delayed seizure detection, according to a recent study.

When infants with port-wine stains receive a dermatology consult, they may also be screened for SWS by means of MRI and by electroencephalography, particularly if their lesion phenotype puts them at higher risk for SWS. But the accuracy and benefit of the screenings has not been well established, said Michaela Zallmann, MD, the study’s first author. Hemifacial lesions that involve both the forehead and cheek and median lesions that are centered around the facial midline are both considered high-risk lesions.

Dr. Zallmann, a dermatologist at Monash University and the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, and her coinvestigators examined data on 126 patients with facial port-wine stains who came to a laser clinic over a 12-month period. Of these, 32 (25.4%) had a high-risk port-wine stain, and 9 of those 32 (28.1%) had a capillary-venous malformation characteristic of SWS. Of the high-risk patients, 14 received a screening MRI or EEG before having had a first seizure. Of those 14 scans, 1 resulted in a diagnosis of SWS; of the 13 patients with a negative MRI screen, 3 (23.1%) were later found to have SWS when their parents or caregivers detected seizures. Thus, a total of four of the high-risk infants who were screened eventually were diagnosed with SWS.

Of the 18 high-risk patients who did not receive a screening MRI, 3 (16.7%) developed seizures, while 2 (11.1%) were seizure free but developed glaucoma severe enough to require treatment. One patient who was also seizure free developed an autism spectrum disorder.

Two patients who were in the high-risk group received screening EEGs that detected abnormalities that were not yet clinically evident. These included sub-clinical seizures and posterior-quadrant focal slowing. Both of these patients had initial negative screening MRIs.

Scanning early in life, using inappropriate imaging protocols, and having an inexperienced radiologist were all factors associated with a higher probability of false negative screening MRI, according to the researchers’ analysis, which was presented in a poster session at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

All of the false negative MRIs in the study cohort were conducted in infants younger than 9 weeks old. But whether it is useful to reserve imaging for later in infancy is debatable. “While later imaging may have improved sensitivity, 75% of infants with SWS will have already had their first seizure by 12 months of age,” wrote Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues.

Of the infants involved in the study, two of the three patients with false negative scans did not receive a referral to a neurologist, nor did their parents receive seizure education. “False reassurance may delay seizure detection,” Dr. Zallmann said.

For infants with positive MRIs who went on to develop seizures, the mean age of when they experienced their first documented seizure was 10 weeks. For those who did not receive an MRI, the mean age was 14 months, compared with 28 months for patients who had received a false negative MRI.

In discussing the findings, Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues made the point that early referral to a pediatric neurologist is important, especially for infants with the higher-risk port-wine stain patterns of hemifacial and median lesions. Seizure education can help parents detect the often subtle signs of seizures in infants with SWS, which can include staring spells, subtle limb twitching, and lip smacking.

The fact that seizures were detected an average of 14 months later in patients with negative screening MRIs may mean that such subtle signs were missed. “False reassurance may delay the recognition and treatment of seizures and impact neurodevelopmental outcomes,” Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues wrote in the abstract that accompanied the poster.

The study, while small, helps fill in some knowledge gaps, the researchers pointed out; they noted that there is no consensus on what level or type of facial involvement warrants screening, which protocols are best for MRI and EEG, or even whether the screening will improve seizure detection or outcomes.

“Currently there is no evidence that screening improves neurodevelopmental outcomes,” they said. “Conversely, there is a role for early neurological referral, symptom education, and potentially of EEGs in the prevention of complications related to SWS.”

Dr. Zallmann reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Screening infants with a port-wine stain for Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) with a magnetic resonance imaging brain scan had a 23% false-negative rate and actually delayed seizure detection, according to a recent study.

When infants with port-wine stains receive a dermatology consult, they may also be screened for SWS by means of MRI and by electroencephalography, particularly if their lesion phenotype puts them at higher risk for SWS. But the accuracy and benefit of the screenings has not been well established, said Michaela Zallmann, MD, the study’s first author. Hemifacial lesions that involve both the forehead and cheek and median lesions that are centered around the facial midline are both considered high-risk lesions.

Dr. Zallmann, a dermatologist at Monash University and the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, and her coinvestigators examined data on 126 patients with facial port-wine stains who came to a laser clinic over a 12-month period. Of these, 32 (25.4%) had a high-risk port-wine stain, and 9 of those 32 (28.1%) had a capillary-venous malformation characteristic of SWS. Of the high-risk patients, 14 received a screening MRI or EEG before having had a first seizure. Of those 14 scans, 1 resulted in a diagnosis of SWS; of the 13 patients with a negative MRI screen, 3 (23.1%) were later found to have SWS when their parents or caregivers detected seizures. Thus, a total of four of the high-risk infants who were screened eventually were diagnosed with SWS.

Of the 18 high-risk patients who did not receive a screening MRI, 3 (16.7%) developed seizures, while 2 (11.1%) were seizure free but developed glaucoma severe enough to require treatment. One patient who was also seizure free developed an autism spectrum disorder.

Two patients who were in the high-risk group received screening EEGs that detected abnormalities that were not yet clinically evident. These included sub-clinical seizures and posterior-quadrant focal slowing. Both of these patients had initial negative screening MRIs.

Scanning early in life, using inappropriate imaging protocols, and having an inexperienced radiologist were all factors associated with a higher probability of false negative screening MRI, according to the researchers’ analysis, which was presented in a poster session at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

All of the false negative MRIs in the study cohort were conducted in infants younger than 9 weeks old. But whether it is useful to reserve imaging for later in infancy is debatable. “While later imaging may have improved sensitivity, 75% of infants with SWS will have already had their first seizure by 12 months of age,” wrote Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues.

Of the infants involved in the study, two of the three patients with false negative scans did not receive a referral to a neurologist, nor did their parents receive seizure education. “False reassurance may delay seizure detection,” Dr. Zallmann said.

For infants with positive MRIs who went on to develop seizures, the mean age of when they experienced their first documented seizure was 10 weeks. For those who did not receive an MRI, the mean age was 14 months, compared with 28 months for patients who had received a false negative MRI.

In discussing the findings, Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues made the point that early referral to a pediatric neurologist is important, especially for infants with the higher-risk port-wine stain patterns of hemifacial and median lesions. Seizure education can help parents detect the often subtle signs of seizures in infants with SWS, which can include staring spells, subtle limb twitching, and lip smacking.

The fact that seizures were detected an average of 14 months later in patients with negative screening MRIs may mean that such subtle signs were missed. “False reassurance may delay the recognition and treatment of seizures and impact neurodevelopmental outcomes,” Dr. Zallmann and her colleagues wrote in the abstract that accompanied the poster.

The study, while small, helps fill in some knowledge gaps, the researchers pointed out; they noted that there is no consensus on what level or type of facial involvement warrants screening, which protocols are best for MRI and EEG, or even whether the screening will improve seizure detection or outcomes.

“Currently there is no evidence that screening improves neurodevelopmental outcomes,” they said. “Conversely, there is a role for early neurological referral, symptom education, and potentially of EEGs in the prevention of complications related to SWS.”

Dr. Zallmann reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT WCPD 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Magnetic resonance imaging screening for Sturge-Weber syndrome resulted in a 23.2% false negative rate in babies with port-wine stain.

Data source: A review of screening and outcomes for 126 infants with port-wine stain seen in a laser clinic over a 12-month period. Disclosures: The lead author reported no disclosures.

Alopecia may be permanent in one in four pediatric HSCT patients

CHICAGO – Late dermatologic manifestations in children who have received hematopoietic stem cell transplants may be more common than previously thought, according to results of a new study.

Johanna Song, MD, and her collaborators reported that, in their prospective pediatric study, 25% of patients had permanent alopecia and 16% had psoriasis, noting that late nonmalignant skin effects of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) have been studied primarily retrospectively, and in adults. Vitiligo and nail changes were also seen.

In a poster presentation at the World Congress of Dermatology, Dr. Song and her colleagues noted that these figures are higher than the previously reported pediatric rates of 1.7% for vitiligo and 15.6% for permanent alopecia. “Early recognition of these late effects can facilitate prompt and appropriate treatment, if desired,” they said.

The single-center, cross-sectional cohort study tracked pediatric patients over an 18-month period and included patients who were at least 1 year post allogeneic HSCT and had not relapsed. Patients who were not English speaking were excluded.

The median age of the 85 patients enrolled in the study was 13.8 years, and participants were a median of 3.6 years post transplant at the time of enrollment. The study’s analysis attempted to determine which patient, transplant, and disease factors might be associated with the late nonmalignant skin changes, according to Dr. Song, a resident dermatologist at Harvard University, Boston, and her colleagues.

Most – 52– of the patients (61.2%) had hematologic malignancies; 12 patients (14.1%) received their transplant for bone marrow failure, and 11 patients (12.5%) had immunodeficiency. Three patients (3.5%) received HSCT for other malignancies, and seven (8.2%) for nonmalignant diseases.

Diffuse hair thinning was seen in 13 (62%) of the 21 patients who had alopecia, while 11 (52%) of the patients with alopecia had an androgenetic hair loss pattern. Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD), skin chronic GVHD, a HSCT regimen that included busulfan conditioning, and a family history of early male-pattern alopecia were all significantly associated with post-HSCT permanent alopecia (P less than .05 for all).

The patients with androgenetic alopecia may be experiencing an accelerated time course of a condition to which they are already genetically disposed, noted Dr. Song and her colleagues.

Psoriasis was commonly seen on the scalp, affecting 11 of the 14 patients with psoriasis (79%), and involved the face in five of the patients (36%). Just one patient had psoriasis elsewhere on the body. There was a nonsignificant trend towards human leukocyte antigen mismatch among patients who had psoriasis. Although “psoriasis may be a marker of persistent immune dysregulation,” the investigators said, they did not identify any associated risk factors that would point toward this mechanism in their analysis.

Twelve patients (14%) had vitiligo, with halo nevi seen in four of these patients. Children who were younger than age 10 years and those who received their transplant for primary immunodeficiency were significantly more likely to have vitiligo (P less than .05 for both). Specific possible mechanisms triggering vitiligo could include thymic dysfunction resulting in loss of self-tolerance, and donor alloreactivity against the patient’s host antigens, according to the authors.

Nail changes such as pterygium and nail pitting, ridging, or thickening were seen in just five patients, all of whom had chronic GVHD of the skin. “Nail changes are likely a result of persistent inflammation and immune dysregulation from chronic GVHD,” said Dr. Song.

These late effects “can significantly impact patients’ quality of life,” according to the authors, who called for larger studies that follow pediatric HSCT patients longitudinally, beginning before the transplant – and for more investigation into the pathogenesis of specific late effects.

Dr. Song reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Late dermatologic manifestations in children who have received hematopoietic stem cell transplants may be more common than previously thought, according to results of a new study.

Johanna Song, MD, and her collaborators reported that, in their prospective pediatric study, 25% of patients had permanent alopecia and 16% had psoriasis, noting that late nonmalignant skin effects of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) have been studied primarily retrospectively, and in adults. Vitiligo and nail changes were also seen.

In a poster presentation at the World Congress of Dermatology, Dr. Song and her colleagues noted that these figures are higher than the previously reported pediatric rates of 1.7% for vitiligo and 15.6% for permanent alopecia. “Early recognition of these late effects can facilitate prompt and appropriate treatment, if desired,” they said.

The single-center, cross-sectional cohort study tracked pediatric patients over an 18-month period and included patients who were at least 1 year post allogeneic HSCT and had not relapsed. Patients who were not English speaking were excluded.

The median age of the 85 patients enrolled in the study was 13.8 years, and participants were a median of 3.6 years post transplant at the time of enrollment. The study’s analysis attempted to determine which patient, transplant, and disease factors might be associated with the late nonmalignant skin changes, according to Dr. Song, a resident dermatologist at Harvard University, Boston, and her colleagues.

Most – 52– of the patients (61.2%) had hematologic malignancies; 12 patients (14.1%) received their transplant for bone marrow failure, and 11 patients (12.5%) had immunodeficiency. Three patients (3.5%) received HSCT for other malignancies, and seven (8.2%) for nonmalignant diseases.

Diffuse hair thinning was seen in 13 (62%) of the 21 patients who had alopecia, while 11 (52%) of the patients with alopecia had an androgenetic hair loss pattern. Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD), skin chronic GVHD, a HSCT regimen that included busulfan conditioning, and a family history of early male-pattern alopecia were all significantly associated with post-HSCT permanent alopecia (P less than .05 for all).

The patients with androgenetic alopecia may be experiencing an accelerated time course of a condition to which they are already genetically disposed, noted Dr. Song and her colleagues.

Psoriasis was commonly seen on the scalp, affecting 11 of the 14 patients with psoriasis (79%), and involved the face in five of the patients (36%). Just one patient had psoriasis elsewhere on the body. There was a nonsignificant trend towards human leukocyte antigen mismatch among patients who had psoriasis. Although “psoriasis may be a marker of persistent immune dysregulation,” the investigators said, they did not identify any associated risk factors that would point toward this mechanism in their analysis.

Twelve patients (14%) had vitiligo, with halo nevi seen in four of these patients. Children who were younger than age 10 years and those who received their transplant for primary immunodeficiency were significantly more likely to have vitiligo (P less than .05 for both). Specific possible mechanisms triggering vitiligo could include thymic dysfunction resulting in loss of self-tolerance, and donor alloreactivity against the patient’s host antigens, according to the authors.

Nail changes such as pterygium and nail pitting, ridging, or thickening were seen in just five patients, all of whom had chronic GVHD of the skin. “Nail changes are likely a result of persistent inflammation and immune dysregulation from chronic GVHD,” said Dr. Song.

These late effects “can significantly impact patients’ quality of life,” according to the authors, who called for larger studies that follow pediatric HSCT patients longitudinally, beginning before the transplant – and for more investigation into the pathogenesis of specific late effects.

Dr. Song reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Late dermatologic manifestations in children who have received hematopoietic stem cell transplants may be more common than previously thought, according to results of a new study.

Johanna Song, MD, and her collaborators reported that, in their prospective pediatric study, 25% of patients had permanent alopecia and 16% had psoriasis, noting that late nonmalignant skin effects of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) have been studied primarily retrospectively, and in adults. Vitiligo and nail changes were also seen.

In a poster presentation at the World Congress of Dermatology, Dr. Song and her colleagues noted that these figures are higher than the previously reported pediatric rates of 1.7% for vitiligo and 15.6% for permanent alopecia. “Early recognition of these late effects can facilitate prompt and appropriate treatment, if desired,” they said.

The single-center, cross-sectional cohort study tracked pediatric patients over an 18-month period and included patients who were at least 1 year post allogeneic HSCT and had not relapsed. Patients who were not English speaking were excluded.

The median age of the 85 patients enrolled in the study was 13.8 years, and participants were a median of 3.6 years post transplant at the time of enrollment. The study’s analysis attempted to determine which patient, transplant, and disease factors might be associated with the late nonmalignant skin changes, according to Dr. Song, a resident dermatologist at Harvard University, Boston, and her colleagues.

Most – 52– of the patients (61.2%) had hematologic malignancies; 12 patients (14.1%) received their transplant for bone marrow failure, and 11 patients (12.5%) had immunodeficiency. Three patients (3.5%) received HSCT for other malignancies, and seven (8.2%) for nonmalignant diseases.

Diffuse hair thinning was seen in 13 (62%) of the 21 patients who had alopecia, while 11 (52%) of the patients with alopecia had an androgenetic hair loss pattern. Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD), skin chronic GVHD, a HSCT regimen that included busulfan conditioning, and a family history of early male-pattern alopecia were all significantly associated with post-HSCT permanent alopecia (P less than .05 for all).

The patients with androgenetic alopecia may be experiencing an accelerated time course of a condition to which they are already genetically disposed, noted Dr. Song and her colleagues.

Psoriasis was commonly seen on the scalp, affecting 11 of the 14 patients with psoriasis (79%), and involved the face in five of the patients (36%). Just one patient had psoriasis elsewhere on the body. There was a nonsignificant trend towards human leukocyte antigen mismatch among patients who had psoriasis. Although “psoriasis may be a marker of persistent immune dysregulation,” the investigators said, they did not identify any associated risk factors that would point toward this mechanism in their analysis.

Twelve patients (14%) had vitiligo, with halo nevi seen in four of these patients. Children who were younger than age 10 years and those who received their transplant for primary immunodeficiency were significantly more likely to have vitiligo (P less than .05 for both). Specific possible mechanisms triggering vitiligo could include thymic dysfunction resulting in loss of self-tolerance, and donor alloreactivity against the patient’s host antigens, according to the authors.

Nail changes such as pterygium and nail pitting, ridging, or thickening were seen in just five patients, all of whom had chronic GVHD of the skin. “Nail changes are likely a result of persistent inflammation and immune dysregulation from chronic GVHD,” said Dr. Song.

These late effects “can significantly impact patients’ quality of life,” according to the authors, who called for larger studies that follow pediatric HSCT patients longitudinally, beginning before the transplant – and for more investigation into the pathogenesis of specific late effects.

Dr. Song reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT WCPD 2017

Key clinical point: