User login

Doug Brunk is a San Diego-based award-winning reporter who began covering health care in 1991. Before joining the company, he wrote for the health sciences division of Columbia University and was an associate editor at Contemporary Long Term Care magazine when it won a Jesse H. Neal Award. His work has been syndicated by the Los Angeles Times and he is the author of two books related to the University of Kentucky Wildcats men's basketball program. Doug has a master’s degree in magazine journalism from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Follow him on Twitter @dougbrunk.

Early-onset atopic dermatitis linked to elevated risk for seasonal allergies and asthma

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – results from a large, retrospective cohort study demonstrated.

“The atopic march is characterized by a progression from atopic dermatitis, usually early in childhood, to subsequent development of allergic rhinitis and asthma, lead study author Joy Wan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is thought that the skin acts as the site of primary sensitization through a defective epithelial barrier, which then allows for allergic sensitization to occur in the airways. It is estimated that 30%-60% of AD patients go on to develop asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. However, not all patients complete the so-called atopic march, and this variation in the risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis among AD patients is not very well understood. Better ways to risk stratify these patients are needed.”

One possible explanation for this variation in the risk of atopy in AD patients could be the timing of their dermatitis onset. “We know that atopic dermatitis begins in infancy, but it can start at any age,” said Dr. Wan, who is a fellow in the section of pediatric dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There has been a distinction between early-onset versus late-onset AD. Some past studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis in children who have early-onset AD before the age of 1 or 2. This suggests that perhaps the model of the atopic march varies between early- and late-onset AD. However, past studies have had several limitations. They’ve often had short durations of follow-up, they’ve only examined narrow ranges of age of onset for AD, and most of them have been designed to primarily evaluate other exposures and outcomes, rather than looking at the timing of AD onset itself.”

For the current study, Dr. Wan and her associates set out to examine the risk of seasonal allergies and asthma among children with AD with respect to the age of AD onset. They used data from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), an ongoing, prospective U.S. cohort of more than 7,700 children with physician-confirmed AD (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Jun;150:593-600). All registry participants had used pimecrolimus cream in the past, but children with lymphoproliferative disease were excluded from the registry, as were those with malignancy or those who required the use of systemic immunosuppression.

The researchers evaluated 3,966 subjects in PEER with at least 3 years of follow-up. The exposure of interest was age of AD onset, and they divided patients into three broad age categories: early onset (age 2 years or younger), mid onset (3-7 years), and late onset (8-17 years). Primary outcomes were prevalent seasonal allergies and asthma at the time of registry enrollment, and incident seasonal allergies and asthma during follow-up, assessed via patient surveys every 3 years.

The study population included high proportions of white and black children, and there was a slight predominance of females. The median age at PEER enrollment increased with advancing age of AD onset (5.2 years in the early-onset group vs. 8.2 years in the mid-onset group and 13.1 years in the late-onset group), while the duration of follow-up was fairly similar across the three groups (a median of about 8.3 months). Family history of AD was common across all three groups, while patients in the late-onset group tended to have better control of their AD, compared with their younger counterparts.

At baseline, the prevalence of seasonal allergies was highest among the early-onset group at 74.6%, compared with 69.9% among the mid-onset group and 70.1% among the late-onset group. After adjusting for sex, race, and age at registry enrollment, the relative risk for prevalent seasonal allergies was 9% lower in the mid-onset group (0.91) and 18% lower in the late-onset group (0.82), compared with those in the early-onset group. Next, Dr. Wan and her associates calculated the incidence of seasonal allergies among 1,054 patients who did not have allergies at baseline. The cumulative incidence was highest among the early-onset group (56.1%), followed by the mid-onset group (46.8%), and the late-onset group (30.6%). On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for seasonal allergies among patients who had no allergies at baseline was 18% lower in the mid-onset group (0.82) and 36% lower in the late-onset group (0.64), compared with those in the early-onset group.

In the analysis of asthma risk by age of AD onset, prevalence was highest among patients in the early-onset group at 51.5%, compared with 44.7% among the mid-onset age group and 43% among the late-onset age group. On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma was 15% lower in the mid-onset group (0.85) and 29% lower in the late-onset group (0.71), compared with those in the early-onset group. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of asthma among patients without asthma at baseline was also highest in the early-onset group (39.2%), compared with 31.9% in the mid-onset group and 29.9% in the late-onset group.

On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma among this subset of patients was 4% lower in the mid-onset group (0.96) and 8% lower in the late-onset group (0.92), compared with those in the early-onset group, a difference that was not statistically significant. “One possible explanation for this is that asthma tends to develop soon after AD does, and the rates of developing asthma later on, as detected by our study, are nondifferential,” Dr. Wan said. “Another possibility is that the impact of early-onset versus late-onset AD is just different for asthma than it is for seasonal allergies.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the risk of misclassification bias and limitations in recall with self-reported data, and the fact that the findings may not be generalizable to all patients with AD.

“Future studies with longer follow-up and studies of adult-onset AD will help extend our findings,” she concluded. “Nevertheless, our findings may inform how we risk stratify patients for AD treatment or atopic march prevention efforts in the future.”

PEER is funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, but Valeant had no role in this study. Dr. Wan reported having no financial disclosures. The study won an award at the meeting for best research presented by a dermatology resident or fellow.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – results from a large, retrospective cohort study demonstrated.

“The atopic march is characterized by a progression from atopic dermatitis, usually early in childhood, to subsequent development of allergic rhinitis and asthma, lead study author Joy Wan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is thought that the skin acts as the site of primary sensitization through a defective epithelial barrier, which then allows for allergic sensitization to occur in the airways. It is estimated that 30%-60% of AD patients go on to develop asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. However, not all patients complete the so-called atopic march, and this variation in the risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis among AD patients is not very well understood. Better ways to risk stratify these patients are needed.”

One possible explanation for this variation in the risk of atopy in AD patients could be the timing of their dermatitis onset. “We know that atopic dermatitis begins in infancy, but it can start at any age,” said Dr. Wan, who is a fellow in the section of pediatric dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There has been a distinction between early-onset versus late-onset AD. Some past studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis in children who have early-onset AD before the age of 1 or 2. This suggests that perhaps the model of the atopic march varies between early- and late-onset AD. However, past studies have had several limitations. They’ve often had short durations of follow-up, they’ve only examined narrow ranges of age of onset for AD, and most of them have been designed to primarily evaluate other exposures and outcomes, rather than looking at the timing of AD onset itself.”

For the current study, Dr. Wan and her associates set out to examine the risk of seasonal allergies and asthma among children with AD with respect to the age of AD onset. They used data from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), an ongoing, prospective U.S. cohort of more than 7,700 children with physician-confirmed AD (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Jun;150:593-600). All registry participants had used pimecrolimus cream in the past, but children with lymphoproliferative disease were excluded from the registry, as were those with malignancy or those who required the use of systemic immunosuppression.

The researchers evaluated 3,966 subjects in PEER with at least 3 years of follow-up. The exposure of interest was age of AD onset, and they divided patients into three broad age categories: early onset (age 2 years or younger), mid onset (3-7 years), and late onset (8-17 years). Primary outcomes were prevalent seasonal allergies and asthma at the time of registry enrollment, and incident seasonal allergies and asthma during follow-up, assessed via patient surveys every 3 years.

The study population included high proportions of white and black children, and there was a slight predominance of females. The median age at PEER enrollment increased with advancing age of AD onset (5.2 years in the early-onset group vs. 8.2 years in the mid-onset group and 13.1 years in the late-onset group), while the duration of follow-up was fairly similar across the three groups (a median of about 8.3 months). Family history of AD was common across all three groups, while patients in the late-onset group tended to have better control of their AD, compared with their younger counterparts.

At baseline, the prevalence of seasonal allergies was highest among the early-onset group at 74.6%, compared with 69.9% among the mid-onset group and 70.1% among the late-onset group. After adjusting for sex, race, and age at registry enrollment, the relative risk for prevalent seasonal allergies was 9% lower in the mid-onset group (0.91) and 18% lower in the late-onset group (0.82), compared with those in the early-onset group. Next, Dr. Wan and her associates calculated the incidence of seasonal allergies among 1,054 patients who did not have allergies at baseline. The cumulative incidence was highest among the early-onset group (56.1%), followed by the mid-onset group (46.8%), and the late-onset group (30.6%). On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for seasonal allergies among patients who had no allergies at baseline was 18% lower in the mid-onset group (0.82) and 36% lower in the late-onset group (0.64), compared with those in the early-onset group.

In the analysis of asthma risk by age of AD onset, prevalence was highest among patients in the early-onset group at 51.5%, compared with 44.7% among the mid-onset age group and 43% among the late-onset age group. On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma was 15% lower in the mid-onset group (0.85) and 29% lower in the late-onset group (0.71), compared with those in the early-onset group. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of asthma among patients without asthma at baseline was also highest in the early-onset group (39.2%), compared with 31.9% in the mid-onset group and 29.9% in the late-onset group.

On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma among this subset of patients was 4% lower in the mid-onset group (0.96) and 8% lower in the late-onset group (0.92), compared with those in the early-onset group, a difference that was not statistically significant. “One possible explanation for this is that asthma tends to develop soon after AD does, and the rates of developing asthma later on, as detected by our study, are nondifferential,” Dr. Wan said. “Another possibility is that the impact of early-onset versus late-onset AD is just different for asthma than it is for seasonal allergies.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the risk of misclassification bias and limitations in recall with self-reported data, and the fact that the findings may not be generalizable to all patients with AD.

“Future studies with longer follow-up and studies of adult-onset AD will help extend our findings,” she concluded. “Nevertheless, our findings may inform how we risk stratify patients for AD treatment or atopic march prevention efforts in the future.”

PEER is funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, but Valeant had no role in this study. Dr. Wan reported having no financial disclosures. The study won an award at the meeting for best research presented by a dermatology resident or fellow.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – results from a large, retrospective cohort study demonstrated.

“The atopic march is characterized by a progression from atopic dermatitis, usually early in childhood, to subsequent development of allergic rhinitis and asthma, lead study author Joy Wan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It is thought that the skin acts as the site of primary sensitization through a defective epithelial barrier, which then allows for allergic sensitization to occur in the airways. It is estimated that 30%-60% of AD patients go on to develop asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. However, not all patients complete the so-called atopic march, and this variation in the risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis among AD patients is not very well understood. Better ways to risk stratify these patients are needed.”

One possible explanation for this variation in the risk of atopy in AD patients could be the timing of their dermatitis onset. “We know that atopic dermatitis begins in infancy, but it can start at any age,” said Dr. Wan, who is a fellow in the section of pediatric dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There has been a distinction between early-onset versus late-onset AD. Some past studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis in children who have early-onset AD before the age of 1 or 2. This suggests that perhaps the model of the atopic march varies between early- and late-onset AD. However, past studies have had several limitations. They’ve often had short durations of follow-up, they’ve only examined narrow ranges of age of onset for AD, and most of them have been designed to primarily evaluate other exposures and outcomes, rather than looking at the timing of AD onset itself.”

For the current study, Dr. Wan and her associates set out to examine the risk of seasonal allergies and asthma among children with AD with respect to the age of AD onset. They used data from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), an ongoing, prospective U.S. cohort of more than 7,700 children with physician-confirmed AD (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Jun;150:593-600). All registry participants had used pimecrolimus cream in the past, but children with lymphoproliferative disease were excluded from the registry, as were those with malignancy or those who required the use of systemic immunosuppression.

The researchers evaluated 3,966 subjects in PEER with at least 3 years of follow-up. The exposure of interest was age of AD onset, and they divided patients into three broad age categories: early onset (age 2 years or younger), mid onset (3-7 years), and late onset (8-17 years). Primary outcomes were prevalent seasonal allergies and asthma at the time of registry enrollment, and incident seasonal allergies and asthma during follow-up, assessed via patient surveys every 3 years.

The study population included high proportions of white and black children, and there was a slight predominance of females. The median age at PEER enrollment increased with advancing age of AD onset (5.2 years in the early-onset group vs. 8.2 years in the mid-onset group and 13.1 years in the late-onset group), while the duration of follow-up was fairly similar across the three groups (a median of about 8.3 months). Family history of AD was common across all three groups, while patients in the late-onset group tended to have better control of their AD, compared with their younger counterparts.

At baseline, the prevalence of seasonal allergies was highest among the early-onset group at 74.6%, compared with 69.9% among the mid-onset group and 70.1% among the late-onset group. After adjusting for sex, race, and age at registry enrollment, the relative risk for prevalent seasonal allergies was 9% lower in the mid-onset group (0.91) and 18% lower in the late-onset group (0.82), compared with those in the early-onset group. Next, Dr. Wan and her associates calculated the incidence of seasonal allergies among 1,054 patients who did not have allergies at baseline. The cumulative incidence was highest among the early-onset group (56.1%), followed by the mid-onset group (46.8%), and the late-onset group (30.6%). On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for seasonal allergies among patients who had no allergies at baseline was 18% lower in the mid-onset group (0.82) and 36% lower in the late-onset group (0.64), compared with those in the early-onset group.

In the analysis of asthma risk by age of AD onset, prevalence was highest among patients in the early-onset group at 51.5%, compared with 44.7% among the mid-onset age group and 43% among the late-onset age group. On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma was 15% lower in the mid-onset group (0.85) and 29% lower in the late-onset group (0.71), compared with those in the early-onset group. Meanwhile, the cumulative incidence of asthma among patients without asthma at baseline was also highest in the early-onset group (39.2%), compared with 31.9% in the mid-onset group and 29.9% in the late-onset group.

On adjusted analysis, the relative risk for asthma among this subset of patients was 4% lower in the mid-onset group (0.96) and 8% lower in the late-onset group (0.92), compared with those in the early-onset group, a difference that was not statistically significant. “One possible explanation for this is that asthma tends to develop soon after AD does, and the rates of developing asthma later on, as detected by our study, are nondifferential,” Dr. Wan said. “Another possibility is that the impact of early-onset versus late-onset AD is just different for asthma than it is for seasonal allergies.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the risk of misclassification bias and limitations in recall with self-reported data, and the fact that the findings may not be generalizable to all patients with AD.

“Future studies with longer follow-up and studies of adult-onset AD will help extend our findings,” she concluded. “Nevertheless, our findings may inform how we risk stratify patients for AD treatment or atopic march prevention efforts in the future.”

PEER is funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, but Valeant had no role in this study. Dr. Wan reported having no financial disclosures. The study won an award at the meeting for best research presented by a dermatology resident or fellow.

AT SPD 2018

Site of morphea lesions predicts risk of extracutaneous manifestations

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Morphea lesions on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head are associated with higher rates of extracutaneous involvement, results from a multicenter retrospective study showed.

“We know that risk is highest with linear morphea,” lead study author Yvonne E. Chiu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Specifically, . However, risk stratification within each of those sites has never really been studied before.”

Dr. Chiu, who is a pediatric dermatologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and her associates carried out a 14-site retrospective study in an effort to characterize morphea lesional distribution and to determine which sites had the highest risk for extracutaneous manifestations. They limited the analysis to patients with pediatric-onset morphea before the age of 18 and adequate lesional photographs in their clinical record. Patients with extragenital lichen sclerosis and atrophoderma were included in the analysis, but those with pansclerotic morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis were excluded. The researchers used custom web-based software to map the morphea lesions, and linked those data to a REDCap database where demographic and clinical information was stored. From this, the researchers tracked neurologic symptoms such as seizures, migraine headaches, other headaches, or any other neurologic signs or symptoms; neurologic testing results from those who underwent MRI, CT, and EEG; musculoskeletal symptoms such as arthritis, arthralgias, joint contracture, leg length discrepancy, and other musculoskeletal issues, as well as ophthalmologic manifestations including uveitis and other ophthalmologic symptoms. Logistic regression was used to analyze association of body sites with extracutaneous involvement.

Dr. Chiu, who also directs the dermatology residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, reported findings from 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea, or an average of about 1.92 lesions per patient. Consistent with prior reports, most patients were female (73%), and the most prevalent subtype was linear morphea (56%), followed by plaque (29%), generalized (8%), and mixed (7%).

The trunk was the single most commonly affected body site, seen in 36% of cases. “However, if you lumped all body sites together, the extremities were the most commonly affected site (44%), while 16% of lesions involved the head and 4% involved the neck,” Dr. Chiu said. Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement. There were small rates of extracutaneous manifestations in the other types of morphea as well.

The most common musculoskeletal complications among patients with linear morphea were arthralgias (20%) and joint contractures (17%), followed by other musculoskeletal complications (15%), leg length discrepancy (5%), and arthritis (2%). Contrary to previously published reports, nonmigraine headaches were more common than seizures among patients with linear morphea (17% vs. 4%, respectively), while 4% of subjects had migraine headaches. Of the 134 subjects who underwent neuroimaging, 19% had abnormal results. Ophthalmologic complications were rare among patients overall, with the exception of those who had linear morphea. Of these cases, 1% had uveitis, and 9% had some other ophthalmologic condition.

Among all patients, the researchers found that left-extremity and extensor-extremity lesions had a stronger association with musculoskeletal involvement (odds ratios of 1.26 and 1.94, respectively). “The reasons for this are unclear,” Dr. Chiu said. “We didn’t assess handedness in our study, but that perhaps could explain it; 90% of the general population is right-hand dominant, so perhaps there’s some sort of protective effect if you’re using an extremity more. Joint contractures showed the greatest discrepancy between left and right extremity. So perhaps if you’re using that one side more, you’re less likely to have a joint contracture.”

When the researchers limited the analysis to head lesions, they observed no significant difference in the lesions between the left and right head (OR, 0.72), but anterior head lesions had a stronger association with neurologic signs or symptoms, compared with posterior head lesions (OR, 2.56), as did superior head lesions, compared with inferior head lesions (OR, 2.23). The association between head lesion location and ophthalmologic involvement was not significant.

“The odds of extracutaneous manifestations vary by site of morphea lesions, with higher odds seen on the left extremity, extensor extremity, the anterior head, and the superior head,” Dr. Chiu concluded. “Further research can be done to perhaps help us decide whether this necessitates difference in management or screening.”

The project was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Morphea lesions on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head are associated with higher rates of extracutaneous involvement, results from a multicenter retrospective study showed.

“We know that risk is highest with linear morphea,” lead study author Yvonne E. Chiu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Specifically, . However, risk stratification within each of those sites has never really been studied before.”

Dr. Chiu, who is a pediatric dermatologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and her associates carried out a 14-site retrospective study in an effort to characterize morphea lesional distribution and to determine which sites had the highest risk for extracutaneous manifestations. They limited the analysis to patients with pediatric-onset morphea before the age of 18 and adequate lesional photographs in their clinical record. Patients with extragenital lichen sclerosis and atrophoderma were included in the analysis, but those with pansclerotic morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis were excluded. The researchers used custom web-based software to map the morphea lesions, and linked those data to a REDCap database where demographic and clinical information was stored. From this, the researchers tracked neurologic symptoms such as seizures, migraine headaches, other headaches, or any other neurologic signs or symptoms; neurologic testing results from those who underwent MRI, CT, and EEG; musculoskeletal symptoms such as arthritis, arthralgias, joint contracture, leg length discrepancy, and other musculoskeletal issues, as well as ophthalmologic manifestations including uveitis and other ophthalmologic symptoms. Logistic regression was used to analyze association of body sites with extracutaneous involvement.

Dr. Chiu, who also directs the dermatology residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, reported findings from 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea, or an average of about 1.92 lesions per patient. Consistent with prior reports, most patients were female (73%), and the most prevalent subtype was linear morphea (56%), followed by plaque (29%), generalized (8%), and mixed (7%).

The trunk was the single most commonly affected body site, seen in 36% of cases. “However, if you lumped all body sites together, the extremities were the most commonly affected site (44%), while 16% of lesions involved the head and 4% involved the neck,” Dr. Chiu said. Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement. There were small rates of extracutaneous manifestations in the other types of morphea as well.

The most common musculoskeletal complications among patients with linear morphea were arthralgias (20%) and joint contractures (17%), followed by other musculoskeletal complications (15%), leg length discrepancy (5%), and arthritis (2%). Contrary to previously published reports, nonmigraine headaches were more common than seizures among patients with linear morphea (17% vs. 4%, respectively), while 4% of subjects had migraine headaches. Of the 134 subjects who underwent neuroimaging, 19% had abnormal results. Ophthalmologic complications were rare among patients overall, with the exception of those who had linear morphea. Of these cases, 1% had uveitis, and 9% had some other ophthalmologic condition.

Among all patients, the researchers found that left-extremity and extensor-extremity lesions had a stronger association with musculoskeletal involvement (odds ratios of 1.26 and 1.94, respectively). “The reasons for this are unclear,” Dr. Chiu said. “We didn’t assess handedness in our study, but that perhaps could explain it; 90% of the general population is right-hand dominant, so perhaps there’s some sort of protective effect if you’re using an extremity more. Joint contractures showed the greatest discrepancy between left and right extremity. So perhaps if you’re using that one side more, you’re less likely to have a joint contracture.”

When the researchers limited the analysis to head lesions, they observed no significant difference in the lesions between the left and right head (OR, 0.72), but anterior head lesions had a stronger association with neurologic signs or symptoms, compared with posterior head lesions (OR, 2.56), as did superior head lesions, compared with inferior head lesions (OR, 2.23). The association between head lesion location and ophthalmologic involvement was not significant.

“The odds of extracutaneous manifestations vary by site of morphea lesions, with higher odds seen on the left extremity, extensor extremity, the anterior head, and the superior head,” Dr. Chiu concluded. “Further research can be done to perhaps help us decide whether this necessitates difference in management or screening.”

The project was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – Morphea lesions on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head are associated with higher rates of extracutaneous involvement, results from a multicenter retrospective study showed.

“We know that risk is highest with linear morphea,” lead study author Yvonne E. Chiu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Specifically, . However, risk stratification within each of those sites has never really been studied before.”

Dr. Chiu, who is a pediatric dermatologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and her associates carried out a 14-site retrospective study in an effort to characterize morphea lesional distribution and to determine which sites had the highest risk for extracutaneous manifestations. They limited the analysis to patients with pediatric-onset morphea before the age of 18 and adequate lesional photographs in their clinical record. Patients with extragenital lichen sclerosis and atrophoderma were included in the analysis, but those with pansclerotic morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis were excluded. The researchers used custom web-based software to map the morphea lesions, and linked those data to a REDCap database where demographic and clinical information was stored. From this, the researchers tracked neurologic symptoms such as seizures, migraine headaches, other headaches, or any other neurologic signs or symptoms; neurologic testing results from those who underwent MRI, CT, and EEG; musculoskeletal symptoms such as arthritis, arthralgias, joint contracture, leg length discrepancy, and other musculoskeletal issues, as well as ophthalmologic manifestations including uveitis and other ophthalmologic symptoms. Logistic regression was used to analyze association of body sites with extracutaneous involvement.

Dr. Chiu, who also directs the dermatology residency program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, reported findings from 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea, or an average of about 1.92 lesions per patient. Consistent with prior reports, most patients were female (73%), and the most prevalent subtype was linear morphea (56%), followed by plaque (29%), generalized (8%), and mixed (7%).

The trunk was the single most commonly affected body site, seen in 36% of cases. “However, if you lumped all body sites together, the extremities were the most commonly affected site (44%), while 16% of lesions involved the head and 4% involved the neck,” Dr. Chiu said. Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement. There were small rates of extracutaneous manifestations in the other types of morphea as well.

The most common musculoskeletal complications among patients with linear morphea were arthralgias (20%) and joint contractures (17%), followed by other musculoskeletal complications (15%), leg length discrepancy (5%), and arthritis (2%). Contrary to previously published reports, nonmigraine headaches were more common than seizures among patients with linear morphea (17% vs. 4%, respectively), while 4% of subjects had migraine headaches. Of the 134 subjects who underwent neuroimaging, 19% had abnormal results. Ophthalmologic complications were rare among patients overall, with the exception of those who had linear morphea. Of these cases, 1% had uveitis, and 9% had some other ophthalmologic condition.

Among all patients, the researchers found that left-extremity and extensor-extremity lesions had a stronger association with musculoskeletal involvement (odds ratios of 1.26 and 1.94, respectively). “The reasons for this are unclear,” Dr. Chiu said. “We didn’t assess handedness in our study, but that perhaps could explain it; 90% of the general population is right-hand dominant, so perhaps there’s some sort of protective effect if you’re using an extremity more. Joint contractures showed the greatest discrepancy between left and right extremity. So perhaps if you’re using that one side more, you’re less likely to have a joint contracture.”

When the researchers limited the analysis to head lesions, they observed no significant difference in the lesions between the left and right head (OR, 0.72), but anterior head lesions had a stronger association with neurologic signs or symptoms, compared with posterior head lesions (OR, 2.56), as did superior head lesions, compared with inferior head lesions (OR, 2.23). The association between head lesion location and ophthalmologic involvement was not significant.

“The odds of extracutaneous manifestations vary by site of morphea lesions, with higher odds seen on the left extremity, extensor extremity, the anterior head, and the superior head,” Dr. Chiu concluded. “Further research can be done to perhaps help us decide whether this necessitates difference in management or screening.”

The project was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

REPORTING FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Extracutaneous involvement is more likely when morphea lesions are present on the extensor extremities, face, and superior head.

Major finding: Patients with linear morphea had the highest rate of extracutaneous involvement. Specifically, 34% had musculoskeletal involvement, 24% had neurologic involvement, and 10% had ophthalmologic involvement.

Study details: A multicenter retrospective study of 826 patients with 2,467 skin lesions of morphea.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance and the SPD. Dr. Chiu reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Spironolactone effectively treats acne in adolescent females

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

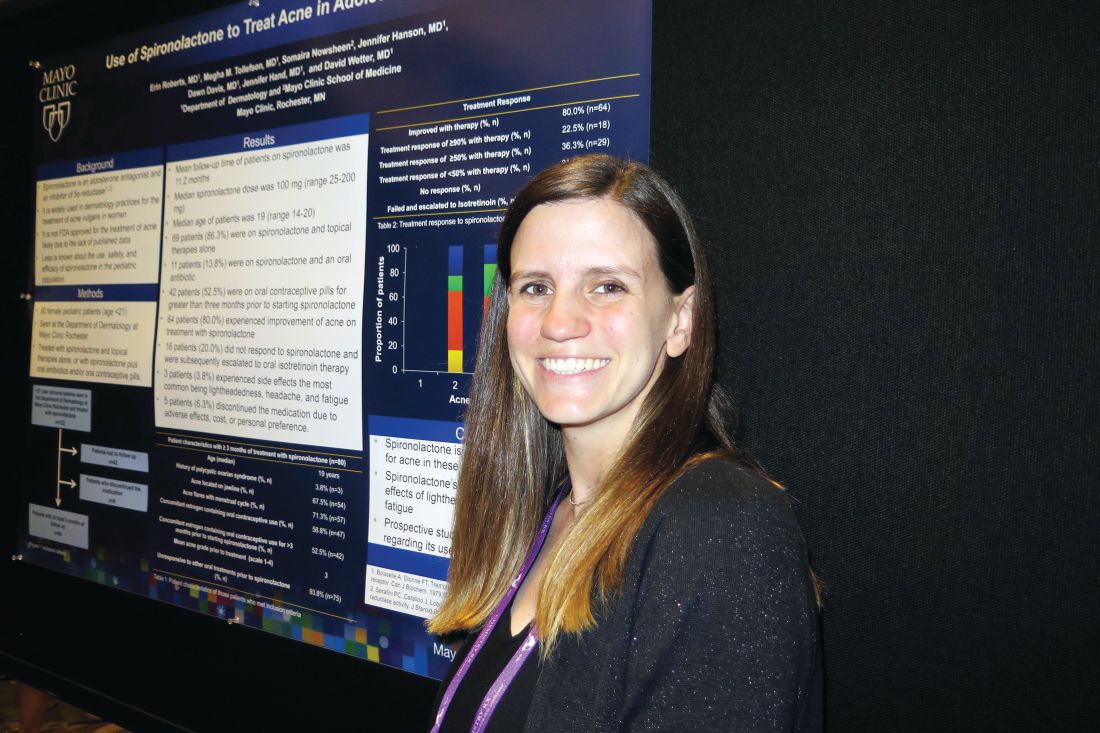

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Erin Roberts, MD, said that while spironolactone is widely used in dermatology for treating acne vulgaris in women, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne, likely because published data are lacking. In addition, she said, less is known about its use, safety, and efficacy in the pediatric population.

Dr. Roberts, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates retrospectively reviewed 80 female patients younger than 21 years of age who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills. All patients were seen by clinicians at the Mayo department of dermatology and were followed for a mean of 11.2 months.

The mean age of patients was 19 years and 71.3% had acne flares with their menstrual cycles, 67.5% had acne located on the jawline, 58.8% had concomitant use of an estrogen-containing oral contraceptive, and 93.8% were unresponsive to other oral treatments prior to using spironolactone.

The median spironolactone daily dose was 100 mg, and ranged between 25 mg and 200 mg. Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone, while 16 (20%) did not respond and were subsequently escalated to oral isotretinoin therapy. Three patients (3.8%) experienced side effects, most commonly lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue, while five patients stopped taking the medication because of adverse effects, cost, or personal preference.

“It was nice to see that spironolactone did improve acne,” Dr. Roberts said. “We think of it as something to use for patients in their 20s, but not as much for patients in their teens. I think it could be a good option for them.” She also recommended starting patients on a dose of 100 mg daily. “We saw that it does have a dose response,” Dr. Roberts said. “It wasn’t until patients got to 100 mg daily that we started to see significant improvement.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Erin Roberts, MD, said that while spironolactone is widely used in dermatology for treating acne vulgaris in women, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne, likely because published data are lacking. In addition, she said, less is known about its use, safety, and efficacy in the pediatric population.

Dr. Roberts, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates retrospectively reviewed 80 female patients younger than 21 years of age who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills. All patients were seen by clinicians at the Mayo department of dermatology and were followed for a mean of 11.2 months.

The mean age of patients was 19 years and 71.3% had acne flares with their menstrual cycles, 67.5% had acne located on the jawline, 58.8% had concomitant use of an estrogen-containing oral contraceptive, and 93.8% were unresponsive to other oral treatments prior to using spironolactone.

The median spironolactone daily dose was 100 mg, and ranged between 25 mg and 200 mg. Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone, while 16 (20%) did not respond and were subsequently escalated to oral isotretinoin therapy. Three patients (3.8%) experienced side effects, most commonly lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue, while five patients stopped taking the medication because of adverse effects, cost, or personal preference.

“It was nice to see that spironolactone did improve acne,” Dr. Roberts said. “We think of it as something to use for patients in their 20s, but not as much for patients in their teens. I think it could be a good option for them.” She also recommended starting patients on a dose of 100 mg daily. “We saw that it does have a dose response,” Dr. Roberts said. “It wasn’t until patients got to 100 mg daily that we started to see significant improvement.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, study author Erin Roberts, MD, said that while spironolactone is widely used in dermatology for treating acne vulgaris in women, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne, likely because published data are lacking. In addition, she said, less is known about its use, safety, and efficacy in the pediatric population.

Dr. Roberts, a resident in the department of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates retrospectively reviewed 80 female patients younger than 21 years of age who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills. All patients were seen by clinicians at the Mayo department of dermatology and were followed for a mean of 11.2 months.

The mean age of patients was 19 years and 71.3% had acne flares with their menstrual cycles, 67.5% had acne located on the jawline, 58.8% had concomitant use of an estrogen-containing oral contraceptive, and 93.8% were unresponsive to other oral treatments prior to using spironolactone.

The median spironolactone daily dose was 100 mg, and ranged between 25 mg and 200 mg. Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone, while 16 (20%) did not respond and were subsequently escalated to oral isotretinoin therapy. Three patients (3.8%) experienced side effects, most commonly lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue, while five patients stopped taking the medication because of adverse effects, cost, or personal preference.

“It was nice to see that spironolactone did improve acne,” Dr. Roberts said. “We think of it as something to use for patients in their 20s, but not as much for patients in their teens. I think it could be a good option for them.” She also recommended starting patients on a dose of 100 mg daily. “We saw that it does have a dose response,” Dr. Roberts said. “It wasn’t until patients got to 100 mg daily that we started to see significant improvement.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Use of spironolactone for acne may be limited by side effects of lightheadedness, headache, and fatigue.

Major finding: Following acne score assessments, the researchers observed that 64 of the 80 patients (80%) experienced improvement of acne on treatment with spironolactone.

Study details: A retrospective review of 80 adolescent females who were treated with spironolactone and topical therapies alone, or with spironolactone plus oral antibiotics and/or contraceptive pills.

Disclosures: Dr. Roberts reported having no financial disclosures.

New analysis improves understanding of PHACE syndrome

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In addition, children with isolated S2 or parotid hemangiomas should be recognized as having lower risk for PHACE, and specifics of evaluation should be discussed with parents on a case-by-case basis.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort study presented by Colleen Cotton, MD, at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

An association between large facial hemangiomas and multiple abnormalities was described as early as 1978, but it wasn’t until 1996 that researchers first proposed the term PHACE to describe the association (Arch Dermatol. 1996;132[3]:307-11). As the National Institutes of Health explain, “PHACE is an acronym for a neurocutaneous syndrome encompassing the following features: posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas of the face, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye abnormalities.” Official diagnostic criteria for PHACE were not established until 2009 (Pediatrics. 2009;124[5]:1447-56) and were updated in 2016 (J Pediatr. 2016;178:24-33.e2).

“A multicenter, prospective, cohort study published in 2010 estimated the incidence of PHACE to be 31% in patients with large facial hemangiomas, while a retrospective study published in 2017 estimated the incidence to be as high as 58%,” Dr. Cotton, chief dermatology resident at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview in advance of the meeting. “With the current understanding of risk for PHACE, any child with a facial hemangioma of greater than or equal to 5 cm in diameter receives a full work-up for the syndrome. However, there has been anecdotal evidence that patients with certain subtypes of hemangiomas (such as parotid hemangiomas) may not carry this same risk.”

In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Cotton and her associates retrospectively analyzed data from 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology centers who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014. The investigators also performed subgroup analyses on different hemangioma characteristics, including parotid hemangiomas and specific facial segments of involvement. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck, and the researchers collected data on age at diagnosis; gender; patterns of hemangioma presentation, including location, size, and depth; diagnostic procedures and results; and type and number of associated anomalies. An expert reviewed photographs or diagrams to confirm facial segment locations.

Of the 244 patients, 34.7% met criteria for PHACE syndrome. On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25cm2 (PPV, 44.8%), with a P value less than .05 for all associations.

Risk of PHACE also increased with the number of locations involved, with a sharp increase observed at three or more locations (PPV, 65.5%; P less than .001). In patients with one unilateral segment involved, S2 and S3 carried a significantly lower risk (P less than .03). Parotid hemangiomas had a negative predictive value of 80.4% (P = .035).

“While we found that patients with parotid hemangiomas had a lower risk of PHACE, 10 patients with parotid hemangiomas did have PHACE, and 90% of those patients had cerebral arterial anomalies,” Dr. Cotton said. “However, only one of these patients had an isolated unilateral parotid hemangioma without other facial segment involvement. Additionally, two patients with isolated involvement of the midcheek below the eye [the S2 location, which was another low risk segment] also had PHACE, both of whom would have been missed without MRI/MRA [magnetic resonance angiography].”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design. “Additionally, many of the very large hemangiomas were not measured in size, and so, estimated sizes needed to be used in calculating relationship of hemangioma size with risk of PHACE,” she said.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.* Dr. Cotton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 7/20/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In addition, children with isolated S2 or parotid hemangiomas should be recognized as having lower risk for PHACE, and specifics of evaluation should be discussed with parents on a case-by-case basis.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort study presented by Colleen Cotton, MD, at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

An association between large facial hemangiomas and multiple abnormalities was described as early as 1978, but it wasn’t until 1996 that researchers first proposed the term PHACE to describe the association (Arch Dermatol. 1996;132[3]:307-11). As the National Institutes of Health explain, “PHACE is an acronym for a neurocutaneous syndrome encompassing the following features: posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas of the face, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye abnormalities.” Official diagnostic criteria for PHACE were not established until 2009 (Pediatrics. 2009;124[5]:1447-56) and were updated in 2016 (J Pediatr. 2016;178:24-33.e2).

“A multicenter, prospective, cohort study published in 2010 estimated the incidence of PHACE to be 31% in patients with large facial hemangiomas, while a retrospective study published in 2017 estimated the incidence to be as high as 58%,” Dr. Cotton, chief dermatology resident at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview in advance of the meeting. “With the current understanding of risk for PHACE, any child with a facial hemangioma of greater than or equal to 5 cm in diameter receives a full work-up for the syndrome. However, there has been anecdotal evidence that patients with certain subtypes of hemangiomas (such as parotid hemangiomas) may not carry this same risk.”

In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Cotton and her associates retrospectively analyzed data from 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology centers who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014. The investigators also performed subgroup analyses on different hemangioma characteristics, including parotid hemangiomas and specific facial segments of involvement. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck, and the researchers collected data on age at diagnosis; gender; patterns of hemangioma presentation, including location, size, and depth; diagnostic procedures and results; and type and number of associated anomalies. An expert reviewed photographs or diagrams to confirm facial segment locations.

Of the 244 patients, 34.7% met criteria for PHACE syndrome. On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25cm2 (PPV, 44.8%), with a P value less than .05 for all associations.

Risk of PHACE also increased with the number of locations involved, with a sharp increase observed at three or more locations (PPV, 65.5%; P less than .001). In patients with one unilateral segment involved, S2 and S3 carried a significantly lower risk (P less than .03). Parotid hemangiomas had a negative predictive value of 80.4% (P = .035).

“While we found that patients with parotid hemangiomas had a lower risk of PHACE, 10 patients with parotid hemangiomas did have PHACE, and 90% of those patients had cerebral arterial anomalies,” Dr. Cotton said. “However, only one of these patients had an isolated unilateral parotid hemangioma without other facial segment involvement. Additionally, two patients with isolated involvement of the midcheek below the eye [the S2 location, which was another low risk segment] also had PHACE, both of whom would have been missed without MRI/MRA [magnetic resonance angiography].”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design. “Additionally, many of the very large hemangiomas were not measured in size, and so, estimated sizes needed to be used in calculating relationship of hemangioma size with risk of PHACE,” she said.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.* Dr. Cotton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 7/20/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. –

In addition, children with isolated S2 or parotid hemangiomas should be recognized as having lower risk for PHACE, and specifics of evaluation should be discussed with parents on a case-by-case basis.

Those are key findings from a retrospective cohort study presented by Colleen Cotton, MD, at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

An association between large facial hemangiomas and multiple abnormalities was described as early as 1978, but it wasn’t until 1996 that researchers first proposed the term PHACE to describe the association (Arch Dermatol. 1996;132[3]:307-11). As the National Institutes of Health explain, “PHACE is an acronym for a neurocutaneous syndrome encompassing the following features: posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas of the face, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye abnormalities.” Official diagnostic criteria for PHACE were not established until 2009 (Pediatrics. 2009;124[5]:1447-56) and were updated in 2016 (J Pediatr. 2016;178:24-33.e2).

“A multicenter, prospective, cohort study published in 2010 estimated the incidence of PHACE to be 31% in patients with large facial hemangiomas, while a retrospective study published in 2017 estimated the incidence to be as high as 58%,” Dr. Cotton, chief dermatology resident at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in an interview in advance of the meeting. “With the current understanding of risk for PHACE, any child with a facial hemangioma of greater than or equal to 5 cm in diameter receives a full work-up for the syndrome. However, there has been anecdotal evidence that patients with certain subtypes of hemangiomas (such as parotid hemangiomas) may not carry this same risk.”

In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Cotton and her associates retrospectively analyzed data from 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology centers who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014. The investigators also performed subgroup analyses on different hemangioma characteristics, including parotid hemangiomas and specific facial segments of involvement. All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck, and the researchers collected data on age at diagnosis; gender; patterns of hemangioma presentation, including location, size, and depth; diagnostic procedures and results; and type and number of associated anomalies. An expert reviewed photographs or diagrams to confirm facial segment locations.

Of the 244 patients, 34.7% met criteria for PHACE syndrome. On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25cm2 (PPV, 44.8%), with a P value less than .05 for all associations.

Risk of PHACE also increased with the number of locations involved, with a sharp increase observed at three or more locations (PPV, 65.5%; P less than .001). In patients with one unilateral segment involved, S2 and S3 carried a significantly lower risk (P less than .03). Parotid hemangiomas had a negative predictive value of 80.4% (P = .035).

“While we found that patients with parotid hemangiomas had a lower risk of PHACE, 10 patients with parotid hemangiomas did have PHACE, and 90% of those patients had cerebral arterial anomalies,” Dr. Cotton said. “However, only one of these patients had an isolated unilateral parotid hemangioma without other facial segment involvement. Additionally, two patients with isolated involvement of the midcheek below the eye [the S2 location, which was another low risk segment] also had PHACE, both of whom would have been missed without MRI/MRA [magnetic resonance angiography].”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design. “Additionally, many of the very large hemangiomas were not measured in size, and so, estimated sizes needed to be used in calculating relationship of hemangioma size with risk of PHACE,” she said.

The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.* Dr. Cotton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 7/20/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance.

FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Children with large, high-risk facial hemangiomas should be prioritized for PHACE syndrome work-up.

Major finding: On multivariate analysis, the following factors were found to be independently and significantly associated with a risk for PHACE: bilateral location (positive predictive value, 54.9%), S1 involvement (PPV, 49.5%), S3 involvement (PPV, 39.5%), and area greater than 25 cm2 (PPV, 44.8%; P less than .05 for all associations).

Study details: A retrospective evaluation of 244 patients from 13 pediatric dermatology who were fully evaluated for PHACE between August 2009 and December 2014.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by a grant from the Pediatric Dermatology Research Association. Dr. Cotton reported having no financial disclosures.

More than 16% of ED sepsis patients not admitted to hospital

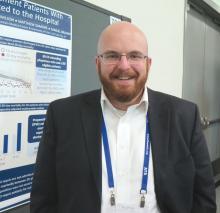

SAN DIEGO – More than 16% of emergency department sepsis patients are not admitted to the hospital, preliminary results from a large retrospective cohort study found.

“Nothing is really known about this topic,” lead study author Ithan D. Peltan, MD, said in an interview at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. “In previous research, we’ve been focused on patients with sepsis who are admitted to the hospital. We have never thoroughly recognized that a fair number of patients who meet clinical criteria for sepsis in the emergency department are actually triaged to outpatient management. We don’t really know anything about these patients. What are their clinical characteristics and what are their outcomes like? And what are the factors that are leading them to be discharged from the ED rather than be admitted to the hospital?”

To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 12,002 adult ED patients who met criteria for sepsis at two tertiary hospitals and two community hospitals in Utah between July 2013 and December 2016. They excluded trauma patients, those who left the ED against medical advice, those who were discharged to hospice or who died in the ED, and eligible patients’ repeat ED encounters. Patients transferred to another acute care facility were considered admitted, while transfers to non-acute care such as skilled nursing or psychiatric facilities were classified as discharges. Next, Dr. Peltan and his associates employed inverse probability weights using a propensity score for ED discharge based on age, sex, Charlson score, ED acuity score, initial ED vital signs, white blood cell count, lactate, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA)score, busyness of the ED, and study hospital to compare 30-day mortality between patients admitted to the hospital versus those discharged from the ED.

Of the 12,002 patients included in the analysis, 10,032 (83.6%) were admitted, while 1,970 (16.4%) were discharged. Compared with admitted patients, discharged patients were younger (a mean of 53 vs. 60 years, respectively; P less than .001); more likely to be female (65% vs. 55%; P less than .001); more likely to be nonwhite or Hispanic (21% vs 17%; P less than .001), and had fewer comorbidities and physiologic derangements. In addition, crude mortality at 30 days was lower in discharged versus admitted patients (1.0% vs. 6.2%, respectively; P less than .001). After the propensity-adjusted analysis, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality for discharged vs. admitted sepsis patients (adjusted odds ratio 1.0).

“We were worried that discharged ED sepsis patients were being mismanaged and weren’t going to do well as similar patients who were admitted to the hospital,” Dr. Peltan said. “This analysis is still a work in progress, but with that caveat, our findings so far suggest that physicians are making pretty good decisions overall.”

The researchers also found that, among 89 ED physicians who cared for 20 or more eligible patients, some did not discharge any of their sepsis patients, while others discharged 39% of their sepsis patients. “That was surprising,” Dr. Peltan said. “This could mean that some hospital sepsis admissions depend on physician practice style more than the patient’s condition or treatment needs.”

Researchers emphasized that they do not recommend routine outpatient management for individual sepsis patients. “Almost certainly, some of the discharged patients should have been admitted to the hospital.” Dr. Peltan said. “I think there’s still a lot of opportunity to understand who these patients are, understand why there is so much physician variation, and to develop tools to further optimize triage decisions.”

The study was funded in part by the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation in Salt Lake City. Dr. Peltan reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peltan ID et al. ATS 2018, Abstract A5994/702.

SAN DIEGO – More than 16% of emergency department sepsis patients are not admitted to the hospital, preliminary results from a large retrospective cohort study found.

“Nothing is really known about this topic,” lead study author Ithan D. Peltan, MD, said in an interview at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. “In previous research, we’ve been focused on patients with sepsis who are admitted to the hospital. We have never thoroughly recognized that a fair number of patients who meet clinical criteria for sepsis in the emergency department are actually triaged to outpatient management. We don’t really know anything about these patients. What are their clinical characteristics and what are their outcomes like? And what are the factors that are leading them to be discharged from the ED rather than be admitted to the hospital?”

To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 12,002 adult ED patients who met criteria for sepsis at two tertiary hospitals and two community hospitals in Utah between July 2013 and December 2016. They excluded trauma patients, those who left the ED against medical advice, those who were discharged to hospice or who died in the ED, and eligible patients’ repeat ED encounters. Patients transferred to another acute care facility were considered admitted, while transfers to non-acute care such as skilled nursing or psychiatric facilities were classified as discharges. Next, Dr. Peltan and his associates employed inverse probability weights using a propensity score for ED discharge based on age, sex, Charlson score, ED acuity score, initial ED vital signs, white blood cell count, lactate, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA)score, busyness of the ED, and study hospital to compare 30-day mortality between patients admitted to the hospital versus those discharged from the ED.

Of the 12,002 patients included in the analysis, 10,032 (83.6%) were admitted, while 1,970 (16.4%) were discharged. Compared with admitted patients, discharged patients were younger (a mean of 53 vs. 60 years, respectively; P less than .001); more likely to be female (65% vs. 55%; P less than .001); more likely to be nonwhite or Hispanic (21% vs 17%; P less than .001), and had fewer comorbidities and physiologic derangements. In addition, crude mortality at 30 days was lower in discharged versus admitted patients (1.0% vs. 6.2%, respectively; P less than .001). After the propensity-adjusted analysis, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality for discharged vs. admitted sepsis patients (adjusted odds ratio 1.0).

“We were worried that discharged ED sepsis patients were being mismanaged and weren’t going to do well as similar patients who were admitted to the hospital,” Dr. Peltan said. “This analysis is still a work in progress, but with that caveat, our findings so far suggest that physicians are making pretty good decisions overall.”

The researchers also found that, among 89 ED physicians who cared for 20 or more eligible patients, some did not discharge any of their sepsis patients, while others discharged 39% of their sepsis patients. “That was surprising,” Dr. Peltan said. “This could mean that some hospital sepsis admissions depend on physician practice style more than the patient’s condition or treatment needs.”

Researchers emphasized that they do not recommend routine outpatient management for individual sepsis patients. “Almost certainly, some of the discharged patients should have been admitted to the hospital.” Dr. Peltan said. “I think there’s still a lot of opportunity to understand who these patients are, understand why there is so much physician variation, and to develop tools to further optimize triage decisions.”

The study was funded in part by the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation in Salt Lake City. Dr. Peltan reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peltan ID et al. ATS 2018, Abstract A5994/702.

SAN DIEGO – More than 16% of emergency department sepsis patients are not admitted to the hospital, preliminary results from a large retrospective cohort study found.

“Nothing is really known about this topic,” lead study author Ithan D. Peltan, MD, said in an interview at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. “In previous research, we’ve been focused on patients with sepsis who are admitted to the hospital. We have never thoroughly recognized that a fair number of patients who meet clinical criteria for sepsis in the emergency department are actually triaged to outpatient management. We don’t really know anything about these patients. What are their clinical characteristics and what are their outcomes like? And what are the factors that are leading them to be discharged from the ED rather than be admitted to the hospital?”

To find out, he and his associates retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 12,002 adult ED patients who met criteria for sepsis at two tertiary hospitals and two community hospitals in Utah between July 2013 and December 2016. They excluded trauma patients, those who left the ED against medical advice, those who were discharged to hospice or who died in the ED, and eligible patients’ repeat ED encounters. Patients transferred to another acute care facility were considered admitted, while transfers to non-acute care such as skilled nursing or psychiatric facilities were classified as discharges. Next, Dr. Peltan and his associates employed inverse probability weights using a propensity score for ED discharge based on age, sex, Charlson score, ED acuity score, initial ED vital signs, white blood cell count, lactate, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA)score, busyness of the ED, and study hospital to compare 30-day mortality between patients admitted to the hospital versus those discharged from the ED.

Of the 12,002 patients included in the analysis, 10,032 (83.6%) were admitted, while 1,970 (16.4%) were discharged. Compared with admitted patients, discharged patients were younger (a mean of 53 vs. 60 years, respectively; P less than .001); more likely to be female (65% vs. 55%; P less than .001); more likely to be nonwhite or Hispanic (21% vs 17%; P less than .001), and had fewer comorbidities and physiologic derangements. In addition, crude mortality at 30 days was lower in discharged versus admitted patients (1.0% vs. 6.2%, respectively; P less than .001). After the propensity-adjusted analysis, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality for discharged vs. admitted sepsis patients (adjusted odds ratio 1.0).

“We were worried that discharged ED sepsis patients were being mismanaged and weren’t going to do well as similar patients who were admitted to the hospital,” Dr. Peltan said. “This analysis is still a work in progress, but with that caveat, our findings so far suggest that physicians are making pretty good decisions overall.”

The researchers also found that, among 89 ED physicians who cared for 20 or more eligible patients, some did not discharge any of their sepsis patients, while others discharged 39% of their sepsis patients. “That was surprising,” Dr. Peltan said. “This could mean that some hospital sepsis admissions depend on physician practice style more than the patient’s condition or treatment needs.”

Researchers emphasized that they do not recommend routine outpatient management for individual sepsis patients. “Almost certainly, some of the discharged patients should have been admitted to the hospital.” Dr. Peltan said. “I think there’s still a lot of opportunity to understand who these patients are, understand why there is so much physician variation, and to develop tools to further optimize triage decisions.”

The study was funded in part by the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation in Salt Lake City. Dr. Peltan reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peltan ID et al. ATS 2018, Abstract A5994/702.

AT ATS 2018

Key clinical point: More research is needed to optimize triage decisions for ED sepsis patients and to understand possible disparities in ED disposition.

Major finding: Among adult patients who met clinical criteria for sepsis in the emergency department, 16.4% were not admitted to the hospital.

Study details: A retrospective study of 12,002 adult ED patients who met criteria for sepsis at two tertiary hospitals and two community hospitals in Utah.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation in Salt Lake City. Dr. Peltan reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Peltan ID et al. Abstract 5994/702, ATS 2018.

Study spotlights risk factors for albuminuria in youth with T2DM

TORONTO – When Brandy Wicklow, MD, began her pediatric endocrinology fellowship at McGill University in 2006, about 12 per 100,000 children in Manitoba, Canada, were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus each year. By 2016 that rate had more than doubled, to 26 per 100,000 children.

“If you look just at indigenous youth in our province, it’s probably one of the highest rates ever reported, with 95 per 100,000 Manitoba First Nation children diagnosed with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Wicklow, a pediatric endocrinologist at the University of Manitoba and the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba.

Many indigenous populations also face an increased risk for primary renal disease. One study reviewed the charts 90 of Canadian First Nation children and adolescents with T2DM (Diabetes Care. 2009;32[5]:786-90). Of 10 who had renal biopsies performed, nine had immune complex disease/glomerulosclerosis, two had mild diabetes-related lesions, and seven had focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS); yet none had classic nephropathy. An analysis of Chinese youth that included 216 renal biopsies yielded similar findings (Intl Urol Nephrol. 2012;45[1]:173-9).

It’s also known that early-onset T2DM is associated with substantially increased incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and mortality in middle age. For example, one study of Pima Indians found that those who were diagnosed with T2DM earlier than 20 years of age had a one in five chance of developing ESRD, while those who were diagnosed at age 20 years or older had a one in two chance of ESRD (JAMA. 2006;296[4]:421-6). In a separate analysis, researchers estimated the remaining lifetime risks for ESRD among Aboriginal people in Australia with and without diabetes (Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103[3]:e24-6). The value for young adults with diabetes was high, about one in two at the age of 30 years, while it decreased with age to one in seven at 60 years.

“One of the first biomarkers we see in terms of renal disease in kids with T2DM is albuminuria,” Dr. Wicklow said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “The question is, why do kids with type 2 get more renal disease than kids with type 1 diabetes?” The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth (SEARCH) study from 2006 found that hypertension, increased body mass index, increased weight circumference, and increased lipids were factors, while the SEARCH study from 2015 found that ethnicity, increased weight to height ratio, and mean arterial pressure were factors.

“Insulin resistance is significantly associated with albuminuria,” Dr. Wicklow continued. “It’s also been shown to be associated with hyperfiltration. Some of the markers of insulin resistance are important but they make up about 19% of the variance between type 1 and type 2, which means there are other variables that we’re not measuring.”

Enter ICARE (Improving Renal Complications in Adolescents with Type 2 Diabetes through Research), an ongoing prospective cohort study that Dr. Wicklow and her associates launched in 2014 at eight centers in Canada. It aims to examine the biopsychosocial risk factors for albuminuria in youth with T2DM and the mechanisms for renal injury. “Our theoretical framework was that biological exposures that we are aware of, such as glycemic control, hypertension, and lipids, would all be important in the development of albuminuria and renal disease in kids,” said Dr. Wicklow, who is the study’s coprimary investigator along with Allison Dart, MD. “But what we thought was novel was that psychological exposures either as socioeconomic status or as mental health factors would also directly impinge on renal health with respect to chronic inflammation in the body, inflammation in the kidneys, and long-term kidney damage.”

The first phase of ICARE involved a detailed phenotypic assessment of youth, including anthropometrics, biochemistry, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, overnight urine collections for albumin excretion, renal ultrasound, and iohexol-derived glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Phase 2 included an evaluation of psychological factors, including hair-derived cortisol; validated questionnaires for perceived stress, distress, and resiliency; and a detailed evaluation of systemic and urine inflammatory biomarkers. Annual follow-up is carried out to assess temporal associations between clinical risk factors and renal outcomes, including progression of albuminuria.

At the meeting, Dr. Wicklow reported on 187 youth enrolled to date. Of these, 96% were of indigenous ethnicity, 57 had albuminuria and 130 did not, and the mean ages of the groups were 16 years and 15 years, respectively. At baseline, a higher proportion of those in the albuminuria group were female (74% vs. 64% of those in the no albuminuria group, respectively), had a higher mean hemoglobin A1c (11% vs. 9%), and had hypertension (94% vs. 72%). She noted that upon presentation to the clinic, only 23% of participants had HbA1c levels less than 7%, only 26% had ranges between 7% and 9%, and about 40% did not have any hypertension. Of those who did, 27% had nighttime-only hypertension, and only 2% had daytime-only hypertension.

“The other risk factor these kids have for developing ESRD is that the majority were exposed to diabetes in pregnancy,” Dr. Wicklow said. “Murine models of maternal diabetes exposure have demonstrated that offspring have small kidneys, less ureteric bud branching, and a lower number of nephrons. Most of the human clinical cohort studies look at associations between development of diabetes and parental hypertension, maternal smoking, and maternal education. There is likely an impact at birth that sets these kids up for development of type 2 diabetes.”

In addition, results from clinical cohort studies have found that depression, mental stress, and distress are high in youth with T2DM. “Preliminary data suggest that if you have positive mental health, or coping strategies, or someone has worked through this with you and you are resilient, you might benefit in terms of overall glycemic control,” she said. For example, ICARE investigators have found that the higher the score on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6), the greater the risk of renal inflammation as measured by monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1; P = .02). “Mental health seems to be something that can directly impact your health from a biological standpoint, and we might be able to find biomarkers of that risk,” Dr. Wicklow said. “Where does the stress come from? Most of my patients are indigenous, so it’s not surprising that the history in Canada of colonization of residential schools has left a lasting impression on these families and communities in terms of loss of language, loss of culture, and loss of land. There’s a community-based stress and a family-based stress that these children feel.”

Social factors also play a big role. She presented baseline findings from 196 youth with T2DM and 456 with T1DM, including measures such as the Socioeconomic Factor Index-Version 2 (SEFI-2), a way to assess socioeconomic characteristics based on Canadian Census data that reflects nonmedical social determinants of health. “It looks at factors like number of rooms in the house, single-parent households, maternal education attainment, and family income,” Dr. Wicklow explained. “The higher the SEFI-2 score, the lower your socioeconomic status is for the area you live in. Kids with T2DM generally live in areas of lower SES and lower socioeconomic index. They often live far away from health care providers. Many do not attend school and many are not with their biologic families, so we’ve had a lot of issues addressing child and family services, in particular in the phase of a chronic illness where our expectation is one thing and the family’s and community’s expectations of what’s realistic in terms of treatment and goals is another. We also have a lot of adolescent pregnancies.”