User login

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox Virus

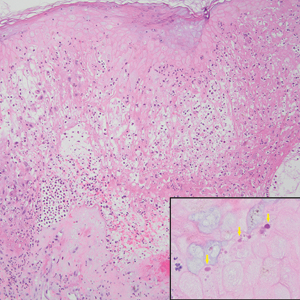

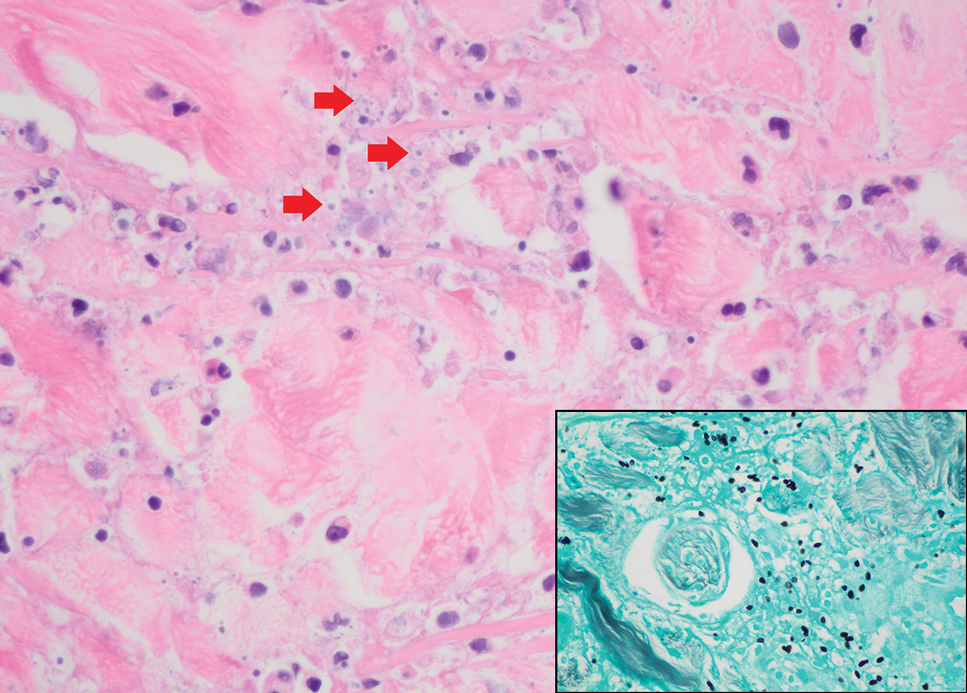

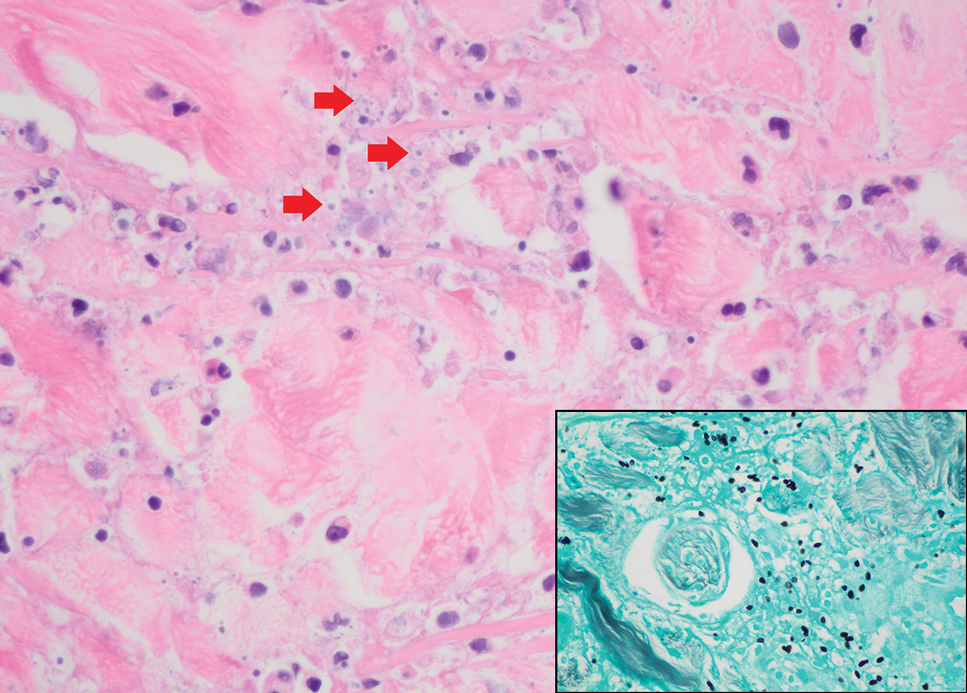

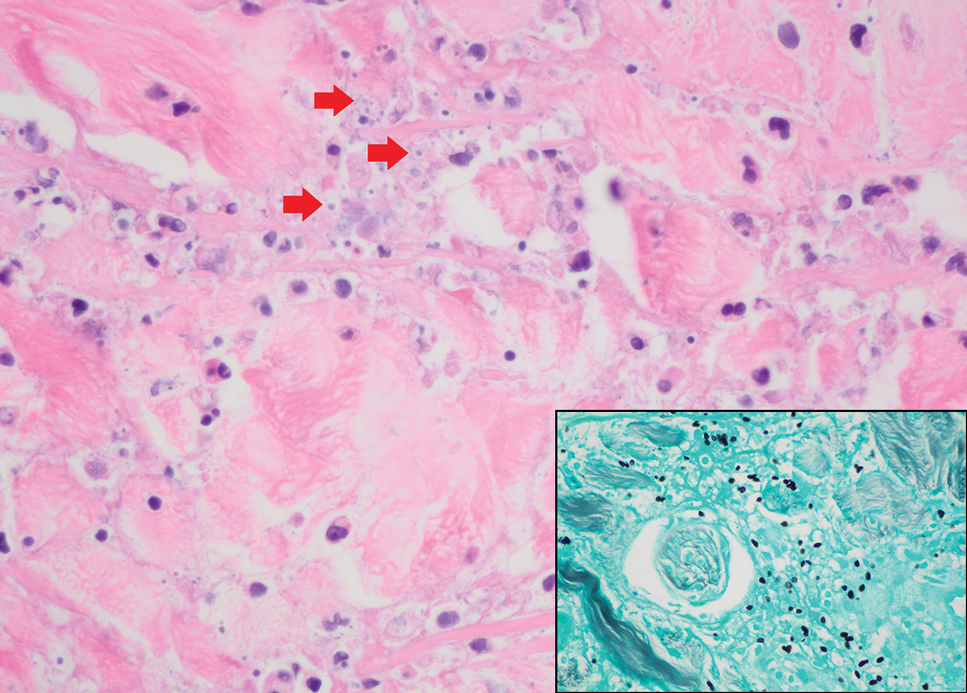

The histopathologic features of mpox virus infection may vary depending on the stage of evolution; findings include ballooning degeneration with multinucleated keratinocytes, acanthosis, spongiosis, a neutrophil-rich inflammatory infiltrate, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies (quiz image inset [arrows]). Prominent neutrophil exocytosis also has been described and may be a characteristic feature in the pustular stage.1,2 A pattern of interface dermatitis also has been observed on histopathology.3 In our patient, the diagnosis of mpox initially was made by clinical and histopathologic correlation and exclusion of other entities in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis subsequently was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The patient received treatment with tecovirimat, but lesions progressed over the following 6 weeks. He subsequently died due to sepsis and multiorgan failure secondary to AIDS.

Mpox is a zoonotic, double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus in the family Poxviridae.4 It is transmitted to humans via direct contact with infected animals, most commonly small mammals such as monkeys, squirrels, and rodents. Mpox also may be transmitted between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids, skin and mucosal lesions, respiratory droplets, or fomites. Mpox infection typically begins with a nonspecific flulike prodrome after a 5- to 21-day incubation period, followed by skin lesions of variable morphology affecting any region of the body. Clinically, mpox lesions have been reported to evolve through macular, papular, and vesiculopustular phases, followed by resolution with crusting. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body but frequently manifest on the face then spread centrifugally across the body, with various phases observed simultaneously.5 A worldwide outbreak in 2022 involved larger numbers of cases in nonendemic areas, primarily due to skin-to-skin contact, with predominant anal and genital localization of the lesions as well as fewer prodromal symptoms.6

The differential diagnosis of crusted and umbilicated papules includes disseminated herpesvirus infection, molluscum contagiosum, disseminated cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis. Additional causative organisms to consider include Penicillium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria, as well as Sporothrix schenckii.

Herpesvirus infections may have similar clinical and histopathologic findings to mpox. Histopathologically, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) are essentially identical; both demonstrate ballooning and reticular epidermal degeneration, chromatin condensation, nuclear degeneration, multinucleated keratinocytes with steel-gray nuclei, and prominent epidermal acantholysis with an inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 1). However, involvement of folliculosebaceous units may favor a diagnosis of VZV. Immunohistochemical staining can further differentiate between HSV and VZV.7 While mpox may have features that overlap with both HSV and VZV, including ballooning degeneration and multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear degeneration, acantholysis is a less commonly reported feature of mpox, and mpox virus infection is characterized by intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies rather than the intranuclear inclusion bodies of HSV and VZV.2,5 The presence of Guarnieri bodies in mpox may further help to distinguish mpox from HSV infection on routine histology.

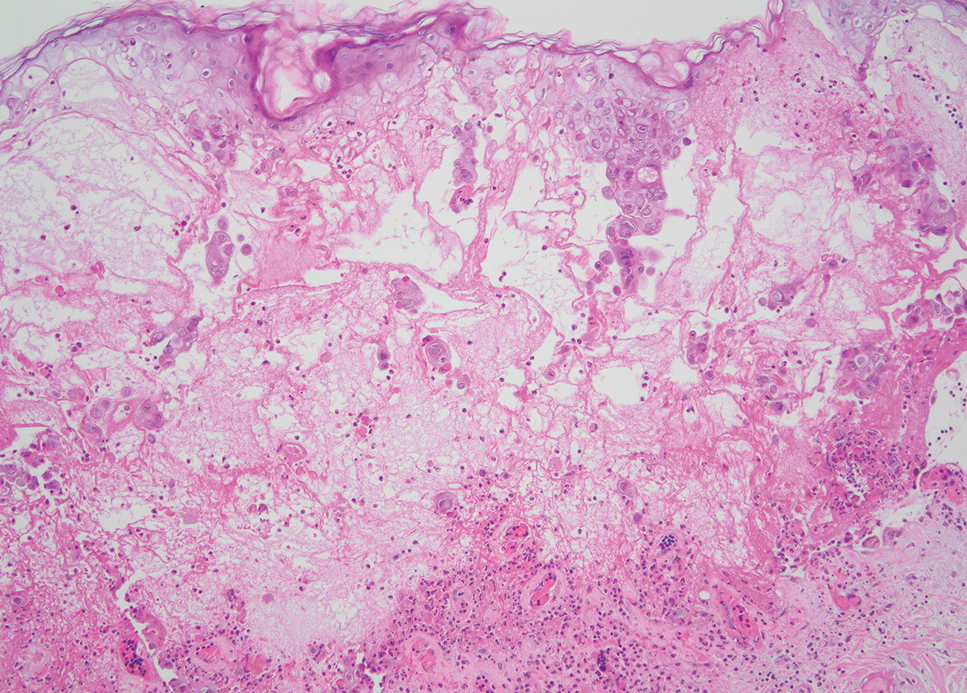

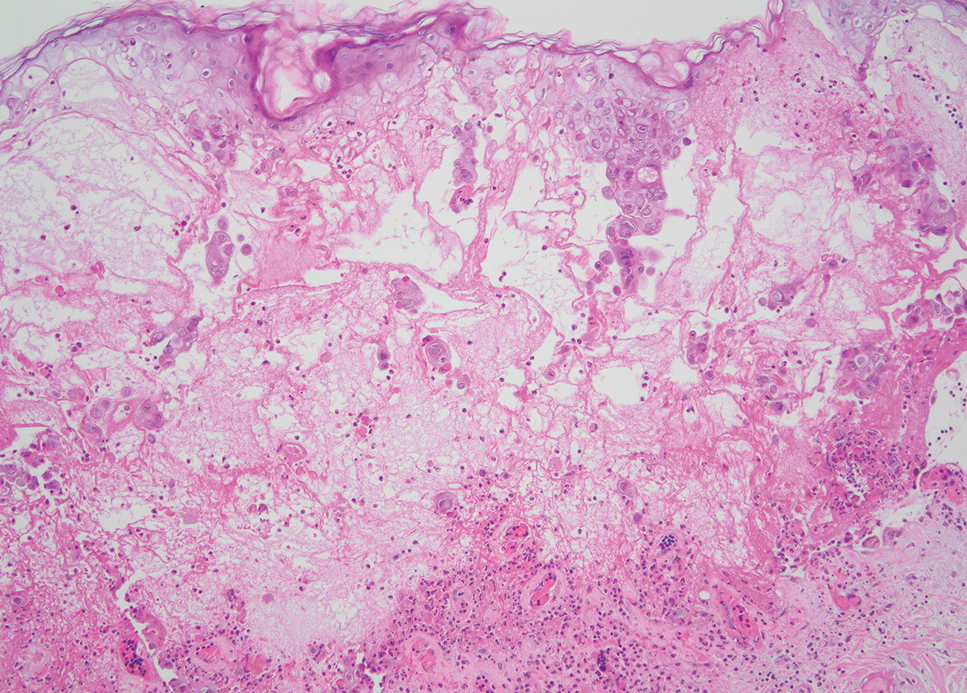

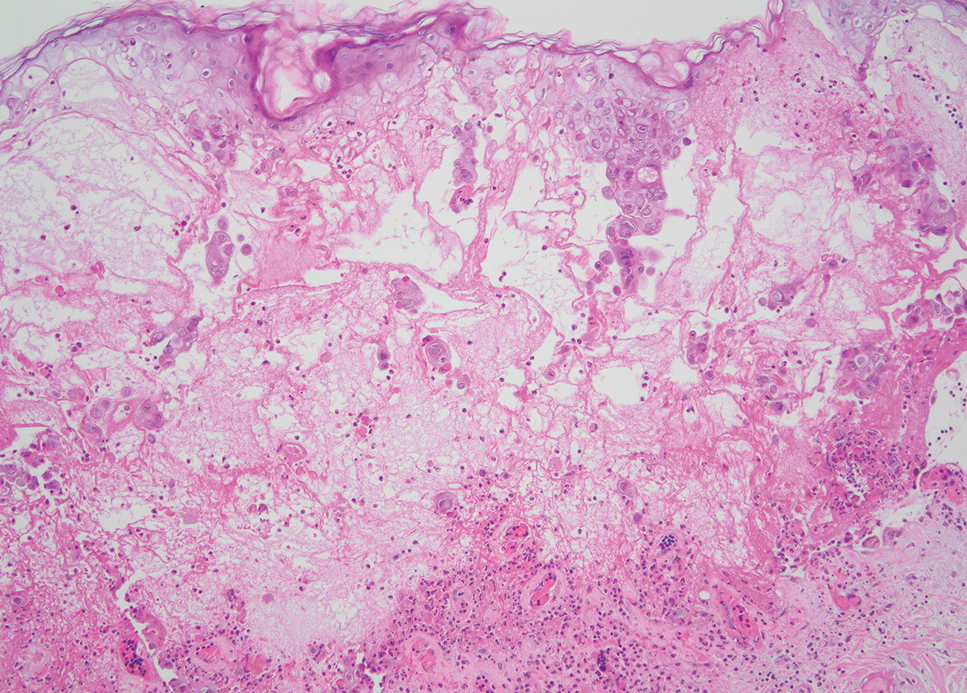

Molluscum contagiosum infection typically manifests as multiple umbilicated papules at sites of inoculation. Large lesions may be seen in the setting of immunosuppression; however, they usually do not progress to vesicular, pustular, or crusted morphologies. Histopathology demonstrates a cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and proliferative rete ridges that descend downward and encircle the dermis with large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion (Henderson-Patterson) bodies (Figure 2).8

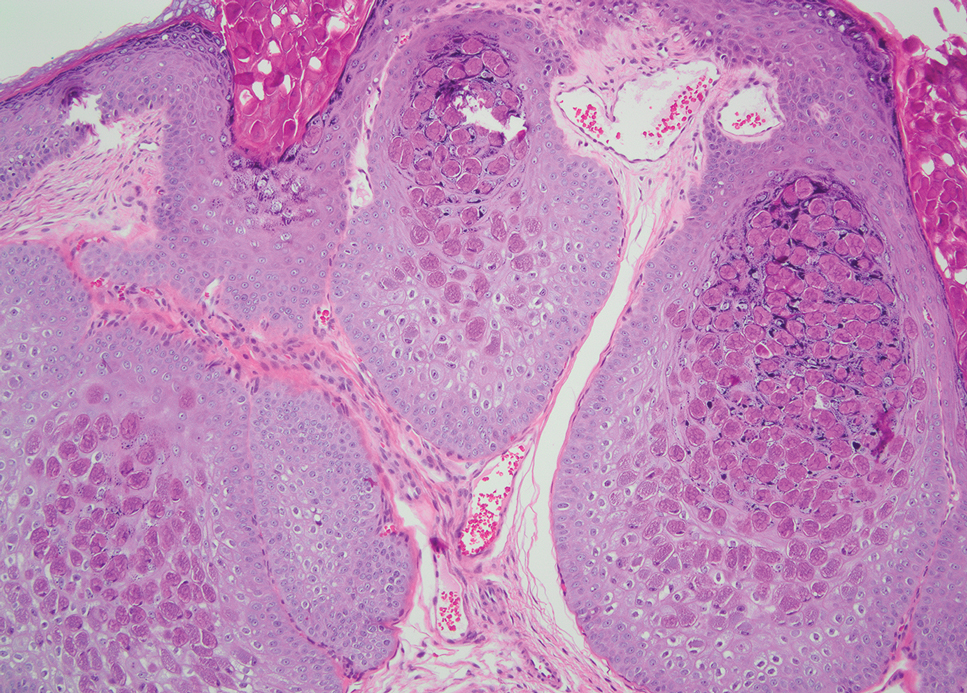

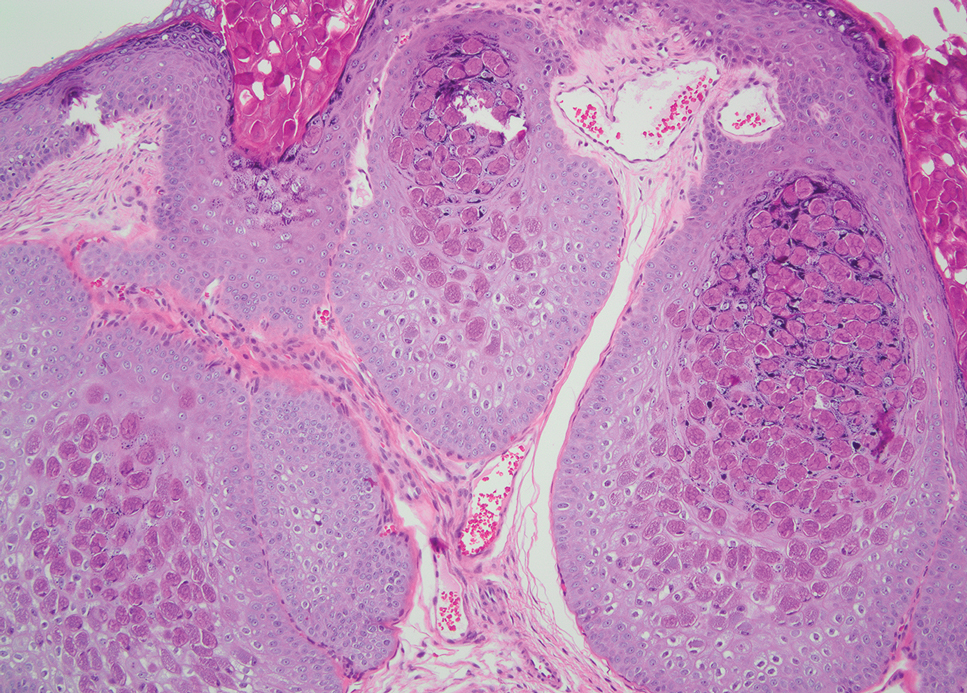

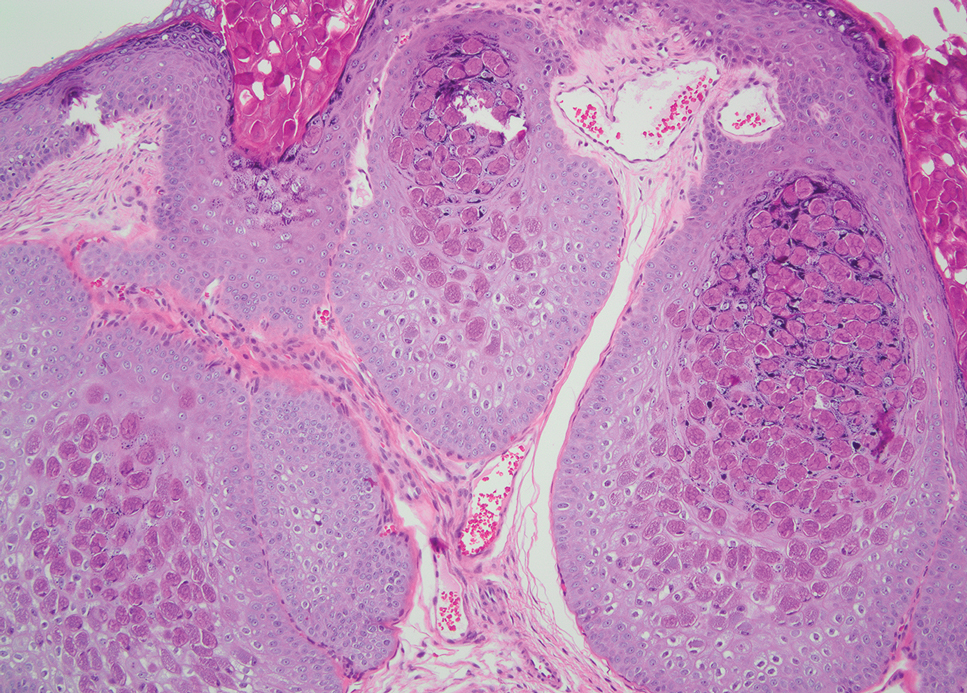

Disseminated cryptococcus infection is caused by the invasive fungus Cryptococcus neoformans and is characterized by meningitis along with fever, malaise, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, pneumonia with cough and dyspnea, and skin rash, most commonly in immunocompromised individuals.9 Skin lesions are a sign of disseminated infection and can manifest as umbilicated or molluscumlike lesions. Histopathology of cryptococcosis demonstrates a granulomatous dermal infiltrate with neutrophils and pleomorphic yeasts measuring 4 µm to 6 µm with refringent capsules.10 Staining with Grocott methenamine silver and/or mucicarmine for yeast capsules can help to identify organisms (Figure 3).

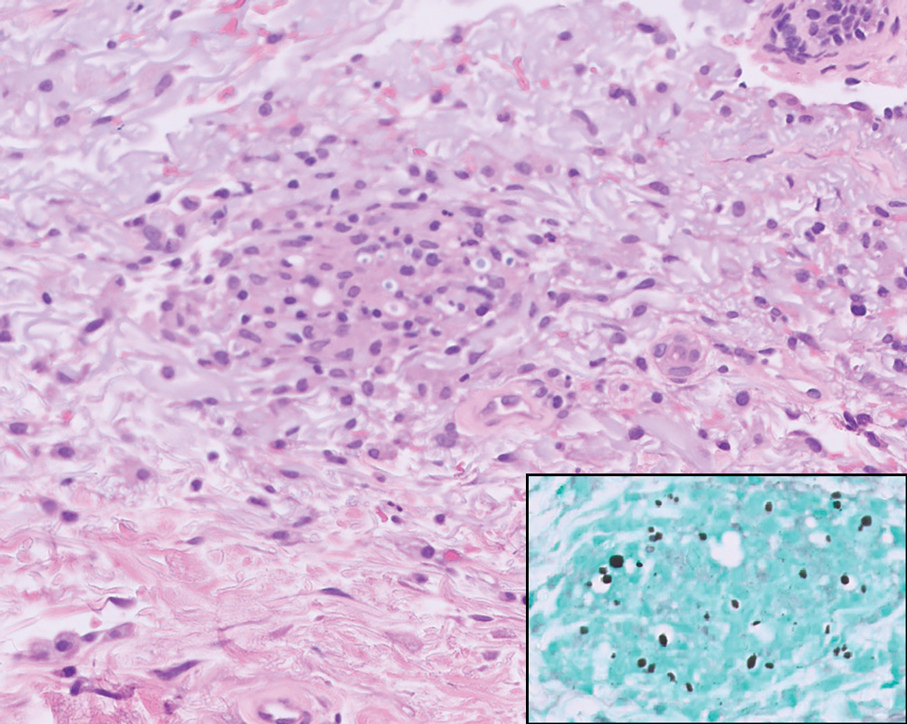

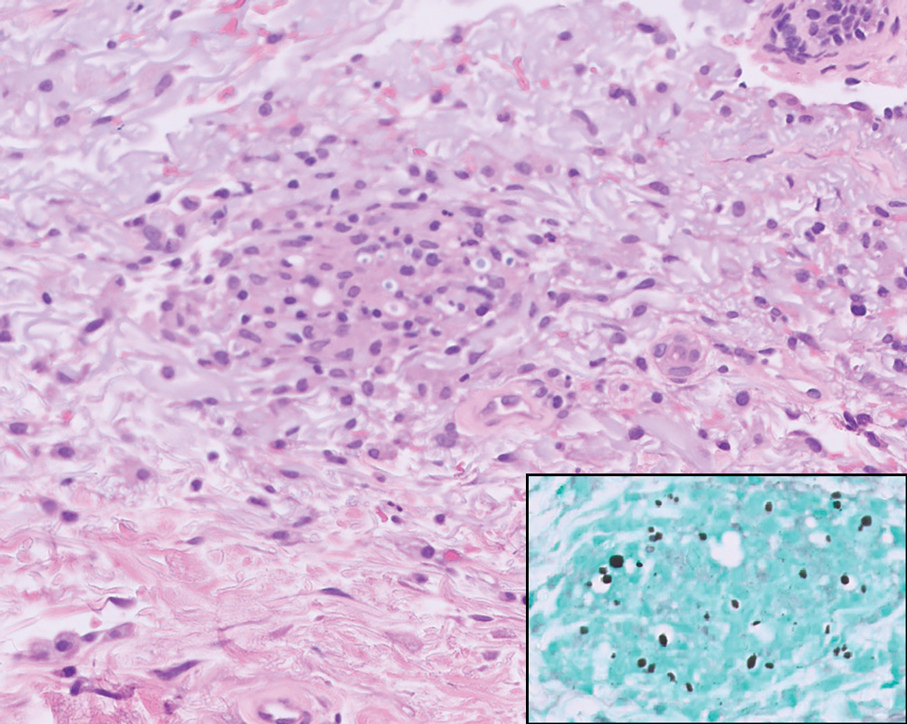

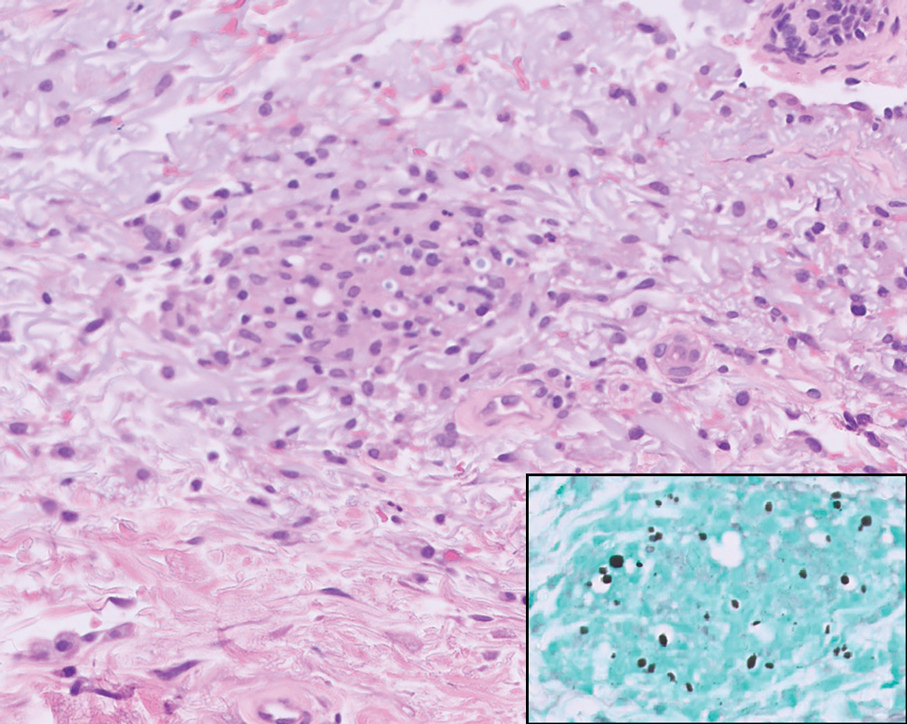

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that can lead to pulmonary, cutaneous, and disseminated disease, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Cutaneous disease may manifest with molluscumlike or verrucous papules and plaques. Histopathologic examination reveals diffuse suppurative and granulomatous infiltrates with foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, containing intracellular and extracellular yeasts measuring 1µm to 5µm, surrounded by a clear halo visible with Grocott methenamine silver stain (Figure 4).

×600). Grocott methenamine silver staining highlights numerous intracellular yeasts (inset, original magnification ×600).

Spreading cutaneous lesions in an immunocompromised individual may be the presentation of multiple infectious etiologies. With the recent rise in mpox cases occurring in nonendemic areas, clinicians should be aware of the spectrum of clinical findings that may occur. Notably, more than one infection may be present in severely immunocompromised individuals, as seen in our patient with chronic orolabial HSV-2 and acute mpox infection. Thorough clinical, histopathologic, and laboratory investigations are necessary for timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and exclusion of other life-threatening conditions.

- Moltrasio C, Boggio FL, Romagnuolo M, et al. Monkeypox: a histopathological and transmission electron microscopy study. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1781-1793. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071781

- Ortins-Pina A, Hegemann B, Saggini A, et al. Histopathological features of human mpox: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:706-710. doi:10.1111/cup.14398

- Chalali F, Merlant M, Truong A, et al. Histological features associated with human mpox virus infection in 2022 outbreak in a nonendemic country. Clin Infect Dis. 21;76:1132-1135. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac856.

- Mpox (monkeypox). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/monkeypox/#tab=tab_1. Accessed August 6, 2025.

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1027-1043. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001

- Philpott D, Hughes CM, Alroy KA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1018-1022. doi:10.15585 /mmwr.mm7132e3

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, et al. Comparative immunohistochemical study of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infections. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:121-126. doi:10.1007 /BF01607163

- Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated March 27, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441898/

- Mada PK, Jamil RT, Alam MU. Cryptococcus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 7, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/

- Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:69-72. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343

- Mustari AP, Rao S, Keshavamurthy V, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023;19:1-4. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_889_2022

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox Virus

The histopathologic features of mpox virus infection may vary depending on the stage of evolution; findings include ballooning degeneration with multinucleated keratinocytes, acanthosis, spongiosis, a neutrophil-rich inflammatory infiltrate, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies (quiz image inset [arrows]). Prominent neutrophil exocytosis also has been described and may be a characteristic feature in the pustular stage.1,2 A pattern of interface dermatitis also has been observed on histopathology.3 In our patient, the diagnosis of mpox initially was made by clinical and histopathologic correlation and exclusion of other entities in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis subsequently was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The patient received treatment with tecovirimat, but lesions progressed over the following 6 weeks. He subsequently died due to sepsis and multiorgan failure secondary to AIDS.

Mpox is a zoonotic, double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus in the family Poxviridae.4 It is transmitted to humans via direct contact with infected animals, most commonly small mammals such as monkeys, squirrels, and rodents. Mpox also may be transmitted between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids, skin and mucosal lesions, respiratory droplets, or fomites. Mpox infection typically begins with a nonspecific flulike prodrome after a 5- to 21-day incubation period, followed by skin lesions of variable morphology affecting any region of the body. Clinically, mpox lesions have been reported to evolve through macular, papular, and vesiculopustular phases, followed by resolution with crusting. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body but frequently manifest on the face then spread centrifugally across the body, with various phases observed simultaneously.5 A worldwide outbreak in 2022 involved larger numbers of cases in nonendemic areas, primarily due to skin-to-skin contact, with predominant anal and genital localization of the lesions as well as fewer prodromal symptoms.6

The differential diagnosis of crusted and umbilicated papules includes disseminated herpesvirus infection, molluscum contagiosum, disseminated cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis. Additional causative organisms to consider include Penicillium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria, as well as Sporothrix schenckii.

Herpesvirus infections may have similar clinical and histopathologic findings to mpox. Histopathologically, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) are essentially identical; both demonstrate ballooning and reticular epidermal degeneration, chromatin condensation, nuclear degeneration, multinucleated keratinocytes with steel-gray nuclei, and prominent epidermal acantholysis with an inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 1). However, involvement of folliculosebaceous units may favor a diagnosis of VZV. Immunohistochemical staining can further differentiate between HSV and VZV.7 While mpox may have features that overlap with both HSV and VZV, including ballooning degeneration and multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear degeneration, acantholysis is a less commonly reported feature of mpox, and mpox virus infection is characterized by intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies rather than the intranuclear inclusion bodies of HSV and VZV.2,5 The presence of Guarnieri bodies in mpox may further help to distinguish mpox from HSV infection on routine histology.

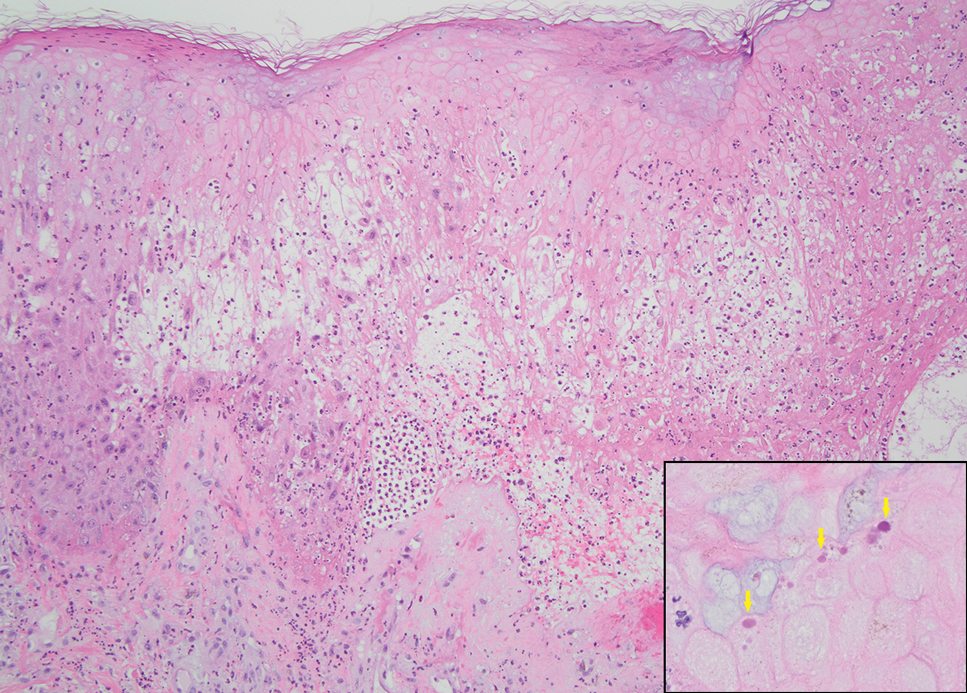

Molluscum contagiosum infection typically manifests as multiple umbilicated papules at sites of inoculation. Large lesions may be seen in the setting of immunosuppression; however, they usually do not progress to vesicular, pustular, or crusted morphologies. Histopathology demonstrates a cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and proliferative rete ridges that descend downward and encircle the dermis with large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion (Henderson-Patterson) bodies (Figure 2).8

Disseminated cryptococcus infection is caused by the invasive fungus Cryptococcus neoformans and is characterized by meningitis along with fever, malaise, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, pneumonia with cough and dyspnea, and skin rash, most commonly in immunocompromised individuals.9 Skin lesions are a sign of disseminated infection and can manifest as umbilicated or molluscumlike lesions. Histopathology of cryptococcosis demonstrates a granulomatous dermal infiltrate with neutrophils and pleomorphic yeasts measuring 4 µm to 6 µm with refringent capsules.10 Staining with Grocott methenamine silver and/or mucicarmine for yeast capsules can help to identify organisms (Figure 3).

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that can lead to pulmonary, cutaneous, and disseminated disease, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Cutaneous disease may manifest with molluscumlike or verrucous papules and plaques. Histopathologic examination reveals diffuse suppurative and granulomatous infiltrates with foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, containing intracellular and extracellular yeasts measuring 1µm to 5µm, surrounded by a clear halo visible with Grocott methenamine silver stain (Figure 4).

×600). Grocott methenamine silver staining highlights numerous intracellular yeasts (inset, original magnification ×600).

Spreading cutaneous lesions in an immunocompromised individual may be the presentation of multiple infectious etiologies. With the recent rise in mpox cases occurring in nonendemic areas, clinicians should be aware of the spectrum of clinical findings that may occur. Notably, more than one infection may be present in severely immunocompromised individuals, as seen in our patient with chronic orolabial HSV-2 and acute mpox infection. Thorough clinical, histopathologic, and laboratory investigations are necessary for timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and exclusion of other life-threatening conditions.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox Virus

The histopathologic features of mpox virus infection may vary depending on the stage of evolution; findings include ballooning degeneration with multinucleated keratinocytes, acanthosis, spongiosis, a neutrophil-rich inflammatory infiltrate, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies (quiz image inset [arrows]). Prominent neutrophil exocytosis also has been described and may be a characteristic feature in the pustular stage.1,2 A pattern of interface dermatitis also has been observed on histopathology.3 In our patient, the diagnosis of mpox initially was made by clinical and histopathologic correlation and exclusion of other entities in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis subsequently was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The patient received treatment with tecovirimat, but lesions progressed over the following 6 weeks. He subsequently died due to sepsis and multiorgan failure secondary to AIDS.

Mpox is a zoonotic, double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus in the family Poxviridae.4 It is transmitted to humans via direct contact with infected animals, most commonly small mammals such as monkeys, squirrels, and rodents. Mpox also may be transmitted between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids, skin and mucosal lesions, respiratory droplets, or fomites. Mpox infection typically begins with a nonspecific flulike prodrome after a 5- to 21-day incubation period, followed by skin lesions of variable morphology affecting any region of the body. Clinically, mpox lesions have been reported to evolve through macular, papular, and vesiculopustular phases, followed by resolution with crusting. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body but frequently manifest on the face then spread centrifugally across the body, with various phases observed simultaneously.5 A worldwide outbreak in 2022 involved larger numbers of cases in nonendemic areas, primarily due to skin-to-skin contact, with predominant anal and genital localization of the lesions as well as fewer prodromal symptoms.6

The differential diagnosis of crusted and umbilicated papules includes disseminated herpesvirus infection, molluscum contagiosum, disseminated cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis. Additional causative organisms to consider include Penicillium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria, as well as Sporothrix schenckii.

Herpesvirus infections may have similar clinical and histopathologic findings to mpox. Histopathologically, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) are essentially identical; both demonstrate ballooning and reticular epidermal degeneration, chromatin condensation, nuclear degeneration, multinucleated keratinocytes with steel-gray nuclei, and prominent epidermal acantholysis with an inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 1). However, involvement of folliculosebaceous units may favor a diagnosis of VZV. Immunohistochemical staining can further differentiate between HSV and VZV.7 While mpox may have features that overlap with both HSV and VZV, including ballooning degeneration and multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear degeneration, acantholysis is a less commonly reported feature of mpox, and mpox virus infection is characterized by intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies rather than the intranuclear inclusion bodies of HSV and VZV.2,5 The presence of Guarnieri bodies in mpox may further help to distinguish mpox from HSV infection on routine histology.

Molluscum contagiosum infection typically manifests as multiple umbilicated papules at sites of inoculation. Large lesions may be seen in the setting of immunosuppression; however, they usually do not progress to vesicular, pustular, or crusted morphologies. Histopathology demonstrates a cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and proliferative rete ridges that descend downward and encircle the dermis with large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion (Henderson-Patterson) bodies (Figure 2).8

Disseminated cryptococcus infection is caused by the invasive fungus Cryptococcus neoformans and is characterized by meningitis along with fever, malaise, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, pneumonia with cough and dyspnea, and skin rash, most commonly in immunocompromised individuals.9 Skin lesions are a sign of disseminated infection and can manifest as umbilicated or molluscumlike lesions. Histopathology of cryptococcosis demonstrates a granulomatous dermal infiltrate with neutrophils and pleomorphic yeasts measuring 4 µm to 6 µm with refringent capsules.10 Staining with Grocott methenamine silver and/or mucicarmine for yeast capsules can help to identify organisms (Figure 3).

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that can lead to pulmonary, cutaneous, and disseminated disease, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Cutaneous disease may manifest with molluscumlike or verrucous papules and plaques. Histopathologic examination reveals diffuse suppurative and granulomatous infiltrates with foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, containing intracellular and extracellular yeasts measuring 1µm to 5µm, surrounded by a clear halo visible with Grocott methenamine silver stain (Figure 4).

×600). Grocott methenamine silver staining highlights numerous intracellular yeasts (inset, original magnification ×600).

Spreading cutaneous lesions in an immunocompromised individual may be the presentation of multiple infectious etiologies. With the recent rise in mpox cases occurring in nonendemic areas, clinicians should be aware of the spectrum of clinical findings that may occur. Notably, more than one infection may be present in severely immunocompromised individuals, as seen in our patient with chronic orolabial HSV-2 and acute mpox infection. Thorough clinical, histopathologic, and laboratory investigations are necessary for timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and exclusion of other life-threatening conditions.

- Moltrasio C, Boggio FL, Romagnuolo M, et al. Monkeypox: a histopathological and transmission electron microscopy study. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1781-1793. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071781

- Ortins-Pina A, Hegemann B, Saggini A, et al. Histopathological features of human mpox: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:706-710. doi:10.1111/cup.14398

- Chalali F, Merlant M, Truong A, et al. Histological features associated with human mpox virus infection in 2022 outbreak in a nonendemic country. Clin Infect Dis. 21;76:1132-1135. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac856.

- Mpox (monkeypox). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/monkeypox/#tab=tab_1. Accessed August 6, 2025.

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1027-1043. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001

- Philpott D, Hughes CM, Alroy KA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1018-1022. doi:10.15585 /mmwr.mm7132e3

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, et al. Comparative immunohistochemical study of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infections. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:121-126. doi:10.1007 /BF01607163

- Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated March 27, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441898/

- Mada PK, Jamil RT, Alam MU. Cryptococcus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 7, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/

- Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:69-72. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343

- Mustari AP, Rao S, Keshavamurthy V, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023;19:1-4. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_889_2022

- Moltrasio C, Boggio FL, Romagnuolo M, et al. Monkeypox: a histopathological and transmission electron microscopy study. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1781-1793. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071781

- Ortins-Pina A, Hegemann B, Saggini A, et al. Histopathological features of human mpox: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:706-710. doi:10.1111/cup.14398

- Chalali F, Merlant M, Truong A, et al. Histological features associated with human mpox virus infection in 2022 outbreak in a nonendemic country. Clin Infect Dis. 21;76:1132-1135. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac856.

- Mpox (monkeypox). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/monkeypox/#tab=tab_1. Accessed August 6, 2025.

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1027-1043. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001

- Philpott D, Hughes CM, Alroy KA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1018-1022. doi:10.15585 /mmwr.mm7132e3

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, et al. Comparative immunohistochemical study of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infections. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:121-126. doi:10.1007 /BF01607163

- Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated March 27, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441898/

- Mada PK, Jamil RT, Alam MU. Cryptococcus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 7, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/

- Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:69-72. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343

- Mustari AP, Rao S, Keshavamurthy V, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023;19:1-4. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_889_2022

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

A 42-year-old man with a history of multidrug-resistant HIV/AIDS presented to the emergency department for evaluation of pruritic, scattered, umbilicated papules on the left cheek, neck, and arms of 3 days’ duration. The patient’s most recent CD4+ T-cell count 6 weeks prior to the development of the rash was 1 cell/mm3. He was noncompliant with antiretroviral therapy. He reported that the lesions had progressed rapidly, starting on the face and extending down the neck and arms. Physical examination revealed scattered umbilicated and centrally crusted papules and plaques on the left cheek, neck, and arms. Erosions involving the oral mucosa also were noted, which the patient reported had been present for several weeks. An oral swab was positive for herpes simplex virus 2 on polymerase chain reaction. A shave biopsy of a lesion from the left cheek was performed.

Tender Nodular Lesions in the Axilla and Vulva

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Histopathologic findings of the left axillary lesion included a diffuse infiltrate of irregular hematolymphoid cells with reniform nuclei that strongly and diffusely stained positively with CD1a and S-100 but were negative for CD138 and CD163 (Figure). Numerous eosinophils also were present. The surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stained positively with CD45. Polymerase chain reaction of the vaginal lesion was negative for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Biopsy of the vaginal lesion revealed a mildly acanthotic epidermis and an aggregation of epithelioid cells with reniform nuclei in the papillary dermis. Positron emission tomography revealed widely disseminated disease. Sequencing of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signalregulated kinase pathway showed amplified expression of these genes but found no mutations. These results led to a diagnosis of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) with a background of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Our patient has since initiated therapy with trametinib leading to disease improvement without known recurrence.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disease of clonal dendritic cells (Langerhans cells) that can present in any organ.1 Most LCH diagnoses are made in pediatric patients, most often presenting in the bones, with other presentations in the skin, hypophysis, liver, lymph nodes, lungs, and spleen occurring less commonly.2 Proto-oncogene BRAF V600E mutations are a common determinant of LCH, with half of cases linked with this mutation that leads to enhanced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, though other mutations have been reported.3,4 These genetic alterations suggest LCH is neoplastic in nature; however, this is controversial, as spontaneous regression among pulmonary LCH has been observed, pointing to a reactive inflammatory process.5 Cutaneous LCH can present as a distinct papular or nodular lesion or multiple lesions with possible ulceration, but it is rare that LCH first presents on the skin.2,6 There is a substantial association of cutaneous LCH with the development of systemically disseminated LCH as well as other blood tumors, such as myelomonocytic leukemia, histiocytic sarcoma, and multiple lymphomas; this association is thought to be due to the common origin of LCH and other blood diseases in the bone marrow.6

Histopathology of LCH shows a diffuse papillary dermal infiltrate of clonal proliferation of reniform or cleaved histiocytes.5 Epidermal ulceration and epidermotropism also are common. Neoplastic cells are found admixed with variable levels of eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils, though eosinophils typically are elevated. Immunohistochemistry characteristically shows the expression of CD1a, S-100, and/or CD207, and the absence of CD163 expression.

Treatment of LCH is primarily dependent on disease dissemination status, with splenic and hepatic involvement, genetic panel results, and central nervous system risk considered in the treatment plan.5 Langerhans cell histiocytosis localized to the skin may require follow-up and monitoring, as spontaneous regression of cutaneous LCH is common. However, topical steroids or psoralen and long-wave UV radiation are potential treatments. Physicians who diagnose unifocal cutaneous LCH should have high clinical suspicion of disseminated LCH, and laboratory and radiographic evaluation may be necessary to rule out systemic disease, as more than 40% of patients with cutaneous LCH have systemic disease upon full evaluation.7 With systemic involvement, systemic chemotherapy may reduce morbidity and mortality, but clinical response should be monitored after 6 weeks of treatment, as results are variably effective. Vinblastine is the most common chemotherapy regimen, with an 84% survival rate and 51.5% event-free survival rate after 8 years.8 Targeted therapy for common genetic mutations also is possible, as vemurafenib has been used to treat patients with the BRAF V600E mutation.

Due to the variable clinical presentation of cutaneous LCH, the lesions can mimic other common skin diseases such as eczema or seborrheic dermatitis.7 However, there are limited data on LCH presenting in infiltrative skin disease. Langerhans cell histiocytosis that was misdiagnosed as HS has been reported,9-11 but LCH presenting alongside long-standing HS is rare. Although LCH often mimics infiltrative skin diseases, its simultaneous presentation with a previously confirmed diagnosis of HS was notable in our patient.

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included HS, Actinomyces infection, lymphomatoid papulosis, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cutaneous findings in HS include chronic acneform nodules with follicular plugging, ruptured ducts leading to epithelized sinuses, inflammation, and abscesses in the axillae or inguinal and perineal areas.11 Histopathology reveals follicular occlusion and hyperkeratinization, which cause destruction of the pilosebaceous glands. Hidradenitis suppurativa features on immunohistochemistry often are conflicting, but there consistently is co-localization of keratinocyte hyperplasia with CD3-, CD4-, CD8-, and CD68-positive staining of cells that produce tumor necrosis factor α, IL-12, IL-23, and IL-32, with CD1a staining variable.12 An infection with Actinomyces, a slow-progressing anaerobic or microaerophilic bacteria, may present in the skin with chronic suppurative inflammation on the neck, trunk, and abdomen. The classic presentation is subcutaneous nodules with localized infiltration of abscesses, fistulas, and draining sinuses.13 Morphologically, Actinomyces causes chronic granulomatous infection with 0.1- to 1-mm sulfur granules, which are seen as basophilic masses with eosinophilic terminal clubs on hematoxylin and eosin staining.14 Histopathology reveals grampositive filamentous Actinomyces bacteria that branch at the edge of the granules. Lymphomatoid papulosis, a nonaggressive T-cell lymphoma, presents as papulonodular and sometimes necrotic disseminated lesions that spontaneously can regress or can cause a higher risk for the development of more aggressive lymphomas.15 Histopathology shows consistently dense, dermal, lymphocytic infiltration. Immunohistochemistry is characterized by lymphocytes expressing CD30 of varying degrees: type A with many CD30 staining cells, type B presenting similar to mycosis fungoides with little CD30 staining, and type C with lymphocytic CD30-staining plaques. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a low-grade soft-tissue malignant tumor with extensive local infiltration characterized by asymptomatic plaques on the trunk and proximal extremities that are indurated and adhered to the skin.16 Histopathology shows extensive invasion into the adjacent tissue far from the original focus of the tumor.

- Girschikofsky M, Arico M, Castillo D, et al. Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-72

- Flores-Terry MA, Sanz-Trenado JL, García-Arpa M, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting in adulthood. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:167-169. doi:10.1016/j .adengl.2018.12.005

- Emile J-F, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

- Bohn OL, Teruya-Feldstein J, Sanchez-Sosa S. Skin biopsy diagnosis of Langerhans cell neoplasms. In: Fernando S, ed. Skin Biopsy: Diagnosis and Treatment [Internet]. InTechOpen; 2013. http://dx.doi .org/10.5772/55893

- Edelbroek JR, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis first presenting in the skin in adults: frequent association with a second haematological malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1287-1294. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11169.x

- Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165: 990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

- Yag˘ ci B, Varan A, Cag˘ lar M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: retrospective analysis of 217 cases in a single center. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;25:399-408. doi:10.1080/08880010802107356

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Mislankar M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with clinical and histologic features of hidradenitis suppurativa: brief report and review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:502-505. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001005

- Chertoff J, Chung J, Ataya A. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis masquerading as hidradenitis suppurativa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:E34-E36. doi:10.1164/rccm.201610-2082IM

- St. Claire K, Bunney R, Ashack KA, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:223-234. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.007

- Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. A systematic review and critical evaluation of immunohistochemical associations in hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Research. 2019;7:1923. doi:10.12688/f1000research.17268.2

- Robati RM, Niknezhad N, Bidari-Zerehpoush F, et al. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis along with the surgical scar on the hand [published online November 9, 2016]. Case Rep Infect Dis. doi:10.1155/2016/5943932

- Ferry T, Valour F, Karsenty J, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Res. 2014;2014:183-197. doi:10.2147/idr.s39601

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785. doi:10.1182 /blood-2004-09-3502

- Tsai Y, Lin P, Chew K, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in children and adolescents: clinical presentation, histology, treatment, and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:1222-1229. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2014.05.03

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Histopathologic findings of the left axillary lesion included a diffuse infiltrate of irregular hematolymphoid cells with reniform nuclei that strongly and diffusely stained positively with CD1a and S-100 but were negative for CD138 and CD163 (Figure). Numerous eosinophils also were present. The surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stained positively with CD45. Polymerase chain reaction of the vaginal lesion was negative for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Biopsy of the vaginal lesion revealed a mildly acanthotic epidermis and an aggregation of epithelioid cells with reniform nuclei in the papillary dermis. Positron emission tomography revealed widely disseminated disease. Sequencing of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signalregulated kinase pathway showed amplified expression of these genes but found no mutations. These results led to a diagnosis of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) with a background of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Our patient has since initiated therapy with trametinib leading to disease improvement without known recurrence.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disease of clonal dendritic cells (Langerhans cells) that can present in any organ.1 Most LCH diagnoses are made in pediatric patients, most often presenting in the bones, with other presentations in the skin, hypophysis, liver, lymph nodes, lungs, and spleen occurring less commonly.2 Proto-oncogene BRAF V600E mutations are a common determinant of LCH, with half of cases linked with this mutation that leads to enhanced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, though other mutations have been reported.3,4 These genetic alterations suggest LCH is neoplastic in nature; however, this is controversial, as spontaneous regression among pulmonary LCH has been observed, pointing to a reactive inflammatory process.5 Cutaneous LCH can present as a distinct papular or nodular lesion or multiple lesions with possible ulceration, but it is rare that LCH first presents on the skin.2,6 There is a substantial association of cutaneous LCH with the development of systemically disseminated LCH as well as other blood tumors, such as myelomonocytic leukemia, histiocytic sarcoma, and multiple lymphomas; this association is thought to be due to the common origin of LCH and other blood diseases in the bone marrow.6

Histopathology of LCH shows a diffuse papillary dermal infiltrate of clonal proliferation of reniform or cleaved histiocytes.5 Epidermal ulceration and epidermotropism also are common. Neoplastic cells are found admixed with variable levels of eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils, though eosinophils typically are elevated. Immunohistochemistry characteristically shows the expression of CD1a, S-100, and/or CD207, and the absence of CD163 expression.

Treatment of LCH is primarily dependent on disease dissemination status, with splenic and hepatic involvement, genetic panel results, and central nervous system risk considered in the treatment plan.5 Langerhans cell histiocytosis localized to the skin may require follow-up and monitoring, as spontaneous regression of cutaneous LCH is common. However, topical steroids or psoralen and long-wave UV radiation are potential treatments. Physicians who diagnose unifocal cutaneous LCH should have high clinical suspicion of disseminated LCH, and laboratory and radiographic evaluation may be necessary to rule out systemic disease, as more than 40% of patients with cutaneous LCH have systemic disease upon full evaluation.7 With systemic involvement, systemic chemotherapy may reduce morbidity and mortality, but clinical response should be monitored after 6 weeks of treatment, as results are variably effective. Vinblastine is the most common chemotherapy regimen, with an 84% survival rate and 51.5% event-free survival rate after 8 years.8 Targeted therapy for common genetic mutations also is possible, as vemurafenib has been used to treat patients with the BRAF V600E mutation.

Due to the variable clinical presentation of cutaneous LCH, the lesions can mimic other common skin diseases such as eczema or seborrheic dermatitis.7 However, there are limited data on LCH presenting in infiltrative skin disease. Langerhans cell histiocytosis that was misdiagnosed as HS has been reported,9-11 but LCH presenting alongside long-standing HS is rare. Although LCH often mimics infiltrative skin diseases, its simultaneous presentation with a previously confirmed diagnosis of HS was notable in our patient.

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included HS, Actinomyces infection, lymphomatoid papulosis, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cutaneous findings in HS include chronic acneform nodules with follicular plugging, ruptured ducts leading to epithelized sinuses, inflammation, and abscesses in the axillae or inguinal and perineal areas.11 Histopathology reveals follicular occlusion and hyperkeratinization, which cause destruction of the pilosebaceous glands. Hidradenitis suppurativa features on immunohistochemistry often are conflicting, but there consistently is co-localization of keratinocyte hyperplasia with CD3-, CD4-, CD8-, and CD68-positive staining of cells that produce tumor necrosis factor α, IL-12, IL-23, and IL-32, with CD1a staining variable.12 An infection with Actinomyces, a slow-progressing anaerobic or microaerophilic bacteria, may present in the skin with chronic suppurative inflammation on the neck, trunk, and abdomen. The classic presentation is subcutaneous nodules with localized infiltration of abscesses, fistulas, and draining sinuses.13 Morphologically, Actinomyces causes chronic granulomatous infection with 0.1- to 1-mm sulfur granules, which are seen as basophilic masses with eosinophilic terminal clubs on hematoxylin and eosin staining.14 Histopathology reveals grampositive filamentous Actinomyces bacteria that branch at the edge of the granules. Lymphomatoid papulosis, a nonaggressive T-cell lymphoma, presents as papulonodular and sometimes necrotic disseminated lesions that spontaneously can regress or can cause a higher risk for the development of more aggressive lymphomas.15 Histopathology shows consistently dense, dermal, lymphocytic infiltration. Immunohistochemistry is characterized by lymphocytes expressing CD30 of varying degrees: type A with many CD30 staining cells, type B presenting similar to mycosis fungoides with little CD30 staining, and type C with lymphocytic CD30-staining plaques. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a low-grade soft-tissue malignant tumor with extensive local infiltration characterized by asymptomatic plaques on the trunk and proximal extremities that are indurated and adhered to the skin.16 Histopathology shows extensive invasion into the adjacent tissue far from the original focus of the tumor.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Histopathologic findings of the left axillary lesion included a diffuse infiltrate of irregular hematolymphoid cells with reniform nuclei that strongly and diffusely stained positively with CD1a and S-100 but were negative for CD138 and CD163 (Figure). Numerous eosinophils also were present. The surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stained positively with CD45. Polymerase chain reaction of the vaginal lesion was negative for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Biopsy of the vaginal lesion revealed a mildly acanthotic epidermis and an aggregation of epithelioid cells with reniform nuclei in the papillary dermis. Positron emission tomography revealed widely disseminated disease. Sequencing of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signalregulated kinase pathway showed amplified expression of these genes but found no mutations. These results led to a diagnosis of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) with a background of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Our patient has since initiated therapy with trametinib leading to disease improvement without known recurrence.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disease of clonal dendritic cells (Langerhans cells) that can present in any organ.1 Most LCH diagnoses are made in pediatric patients, most often presenting in the bones, with other presentations in the skin, hypophysis, liver, lymph nodes, lungs, and spleen occurring less commonly.2 Proto-oncogene BRAF V600E mutations are a common determinant of LCH, with half of cases linked with this mutation that leads to enhanced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, though other mutations have been reported.3,4 These genetic alterations suggest LCH is neoplastic in nature; however, this is controversial, as spontaneous regression among pulmonary LCH has been observed, pointing to a reactive inflammatory process.5 Cutaneous LCH can present as a distinct papular or nodular lesion or multiple lesions with possible ulceration, but it is rare that LCH first presents on the skin.2,6 There is a substantial association of cutaneous LCH with the development of systemically disseminated LCH as well as other blood tumors, such as myelomonocytic leukemia, histiocytic sarcoma, and multiple lymphomas; this association is thought to be due to the common origin of LCH and other blood diseases in the bone marrow.6

Histopathology of LCH shows a diffuse papillary dermal infiltrate of clonal proliferation of reniform or cleaved histiocytes.5 Epidermal ulceration and epidermotropism also are common. Neoplastic cells are found admixed with variable levels of eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils, though eosinophils typically are elevated. Immunohistochemistry characteristically shows the expression of CD1a, S-100, and/or CD207, and the absence of CD163 expression.

Treatment of LCH is primarily dependent on disease dissemination status, with splenic and hepatic involvement, genetic panel results, and central nervous system risk considered in the treatment plan.5 Langerhans cell histiocytosis localized to the skin may require follow-up and monitoring, as spontaneous regression of cutaneous LCH is common. However, topical steroids or psoralen and long-wave UV radiation are potential treatments. Physicians who diagnose unifocal cutaneous LCH should have high clinical suspicion of disseminated LCH, and laboratory and radiographic evaluation may be necessary to rule out systemic disease, as more than 40% of patients with cutaneous LCH have systemic disease upon full evaluation.7 With systemic involvement, systemic chemotherapy may reduce morbidity and mortality, but clinical response should be monitored after 6 weeks of treatment, as results are variably effective. Vinblastine is the most common chemotherapy regimen, with an 84% survival rate and 51.5% event-free survival rate after 8 years.8 Targeted therapy for common genetic mutations also is possible, as vemurafenib has been used to treat patients with the BRAF V600E mutation.

Due to the variable clinical presentation of cutaneous LCH, the lesions can mimic other common skin diseases such as eczema or seborrheic dermatitis.7 However, there are limited data on LCH presenting in infiltrative skin disease. Langerhans cell histiocytosis that was misdiagnosed as HS has been reported,9-11 but LCH presenting alongside long-standing HS is rare. Although LCH often mimics infiltrative skin diseases, its simultaneous presentation with a previously confirmed diagnosis of HS was notable in our patient.

In our patient, the differential diagnosis included HS, Actinomyces infection, lymphomatoid papulosis, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cutaneous findings in HS include chronic acneform nodules with follicular plugging, ruptured ducts leading to epithelized sinuses, inflammation, and abscesses in the axillae or inguinal and perineal areas.11 Histopathology reveals follicular occlusion and hyperkeratinization, which cause destruction of the pilosebaceous glands. Hidradenitis suppurativa features on immunohistochemistry often are conflicting, but there consistently is co-localization of keratinocyte hyperplasia with CD3-, CD4-, CD8-, and CD68-positive staining of cells that produce tumor necrosis factor α, IL-12, IL-23, and IL-32, with CD1a staining variable.12 An infection with Actinomyces, a slow-progressing anaerobic or microaerophilic bacteria, may present in the skin with chronic suppurative inflammation on the neck, trunk, and abdomen. The classic presentation is subcutaneous nodules with localized infiltration of abscesses, fistulas, and draining sinuses.13 Morphologically, Actinomyces causes chronic granulomatous infection with 0.1- to 1-mm sulfur granules, which are seen as basophilic masses with eosinophilic terminal clubs on hematoxylin and eosin staining.14 Histopathology reveals grampositive filamentous Actinomyces bacteria that branch at the edge of the granules. Lymphomatoid papulosis, a nonaggressive T-cell lymphoma, presents as papulonodular and sometimes necrotic disseminated lesions that spontaneously can regress or can cause a higher risk for the development of more aggressive lymphomas.15 Histopathology shows consistently dense, dermal, lymphocytic infiltration. Immunohistochemistry is characterized by lymphocytes expressing CD30 of varying degrees: type A with many CD30 staining cells, type B presenting similar to mycosis fungoides with little CD30 staining, and type C with lymphocytic CD30-staining plaques. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a low-grade soft-tissue malignant tumor with extensive local infiltration characterized by asymptomatic plaques on the trunk and proximal extremities that are indurated and adhered to the skin.16 Histopathology shows extensive invasion into the adjacent tissue far from the original focus of the tumor.

- Girschikofsky M, Arico M, Castillo D, et al. Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-72

- Flores-Terry MA, Sanz-Trenado JL, García-Arpa M, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting in adulthood. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:167-169. doi:10.1016/j .adengl.2018.12.005

- Emile J-F, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

- Bohn OL, Teruya-Feldstein J, Sanchez-Sosa S. Skin biopsy diagnosis of Langerhans cell neoplasms. In: Fernando S, ed. Skin Biopsy: Diagnosis and Treatment [Internet]. InTechOpen; 2013. http://dx.doi .org/10.5772/55893

- Edelbroek JR, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis first presenting in the skin in adults: frequent association with a second haematological malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1287-1294. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11169.x

- Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165: 990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

- Yag˘ ci B, Varan A, Cag˘ lar M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: retrospective analysis of 217 cases in a single center. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;25:399-408. doi:10.1080/08880010802107356

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Mislankar M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with clinical and histologic features of hidradenitis suppurativa: brief report and review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:502-505. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001005

- Chertoff J, Chung J, Ataya A. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis masquerading as hidradenitis suppurativa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:E34-E36. doi:10.1164/rccm.201610-2082IM

- St. Claire K, Bunney R, Ashack KA, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:223-234. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.007

- Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. A systematic review and critical evaluation of immunohistochemical associations in hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Research. 2019;7:1923. doi:10.12688/f1000research.17268.2

- Robati RM, Niknezhad N, Bidari-Zerehpoush F, et al. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis along with the surgical scar on the hand [published online November 9, 2016]. Case Rep Infect Dis. doi:10.1155/2016/5943932

- Ferry T, Valour F, Karsenty J, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Res. 2014;2014:183-197. doi:10.2147/idr.s39601

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785. doi:10.1182 /blood-2004-09-3502

- Tsai Y, Lin P, Chew K, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in children and adolescents: clinical presentation, histology, treatment, and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:1222-1229. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2014.05.03

- Girschikofsky M, Arico M, Castillo D, et al. Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-72

- Flores-Terry MA, Sanz-Trenado JL, García-Arpa M, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting in adulthood. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:167-169. doi:10.1016/j .adengl.2018.12.005

- Emile J-F, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

- Bohn OL, Teruya-Feldstein J, Sanchez-Sosa S. Skin biopsy diagnosis of Langerhans cell neoplasms. In: Fernando S, ed. Skin Biopsy: Diagnosis and Treatment [Internet]. InTechOpen; 2013. http://dx.doi .org/10.5772/55893

- Edelbroek JR, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis first presenting in the skin in adults: frequent association with a second haematological malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1287-1294. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11169.x

- Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165: 990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

- Yag˘ ci B, Varan A, Cag˘ lar M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: retrospective analysis of 217 cases in a single center. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;25:399-408. doi:10.1080/08880010802107356

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Mislankar M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with clinical and histologic features of hidradenitis suppurativa: brief report and review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:502-505. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001005

- Chertoff J, Chung J, Ataya A. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis masquerading as hidradenitis suppurativa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:E34-E36. doi:10.1164/rccm.201610-2082IM

- St. Claire K, Bunney R, Ashack KA, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:223-234. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.007

- Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. A systematic review and critical evaluation of immunohistochemical associations in hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Research. 2019;7:1923. doi:10.12688/f1000research.17268.2

- Robati RM, Niknezhad N, Bidari-Zerehpoush F, et al. Primary cutaneous actinomycosis along with the surgical scar on the hand [published online November 9, 2016]. Case Rep Infect Dis. doi:10.1155/2016/5943932

- Ferry T, Valour F, Karsenty J, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Res. 2014;2014:183-197. doi:10.2147/idr.s39601

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785. doi:10.1182 /blood-2004-09-3502

- Tsai Y, Lin P, Chew K, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in children and adolescents: clinical presentation, histology, treatment, and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:1222-1229. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2014.05.03

A 28-year-old woman presented with tender burning lesions of the left axillary and vaginal skin that had worsened over the last year. Her medical history was notable for hidradenitis suppurativa, which had been present since adolescence, as well as pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis diagnosed 7 years prior to the current presentation after a spontaneous pneumothorax that eventually led to a pulmonary transplantation 3 years prior. The patient’s Langerhans cell histiocytosis was believed to have resolved without treatment after smoking cessation. Physical examination revealed nodular inflammation and scarring with deep undermining along the left axilla as well as swelling of the mons pubis with erosive skin lesions in the surrounding vaginal area. Bilateral cervical, axillary, inguinal, supraclavicular, and femoral lymph node chains were negative for adenopathy. A shave biopsy was performed on the axillary nodule.