User login

Consider measles vaccine booster in HIV-positive patients

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Breastfeeding protects against intussusception

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – in a German case-control study.

Two other potent risk factors for intussusception in children less than 1 year old were identified: a family history of intussusception, and an episode of gastroenteritis, Doris F. Oberle, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Oberle, of the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, presented a retrospective study of 116 meticulously validated cases of intussusception in infancy treated at 19 German pediatric centers during 2010-2014 and 272 controls matched by birth month, sex, and location. A standardized interview was conducted with the parents of all study participants.

Rotavirus vaccine was added to the German national vaccination schedule in 2013. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the risk of intussusception was increased by 5.4-fold following the first dose of the vaccine, compared with nonrecipients. However, subsequent doses of rotavirus vaccine were not associated with any excess risk.

In addition, a family history of intussusception was linked to a 4.2-fold increased risk, while an episode of gastroenteritis during the first year of life was associated with a 4.7-fold elevated risk.

In a novel finding, breastfeeding was independently associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of intussusception, compared with that of bottle-fed babies.

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of intussusception were vomiting, abdominal pain, hematochezia, pallor, and reduced appetite, each present in at least half of affected infants.

Dr. Oberle reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the Paul Ehrlich Institute.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – in a German case-control study.

Two other potent risk factors for intussusception in children less than 1 year old were identified: a family history of intussusception, and an episode of gastroenteritis, Doris F. Oberle, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Oberle, of the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, presented a retrospective study of 116 meticulously validated cases of intussusception in infancy treated at 19 German pediatric centers during 2010-2014 and 272 controls matched by birth month, sex, and location. A standardized interview was conducted with the parents of all study participants.

Rotavirus vaccine was added to the German national vaccination schedule in 2013. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the risk of intussusception was increased by 5.4-fold following the first dose of the vaccine, compared with nonrecipients. However, subsequent doses of rotavirus vaccine were not associated with any excess risk.

In addition, a family history of intussusception was linked to a 4.2-fold increased risk, while an episode of gastroenteritis during the first year of life was associated with a 4.7-fold elevated risk.

In a novel finding, breastfeeding was independently associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of intussusception, compared with that of bottle-fed babies.

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of intussusception were vomiting, abdominal pain, hematochezia, pallor, and reduced appetite, each present in at least half of affected infants.

Dr. Oberle reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the Paul Ehrlich Institute.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – in a German case-control study.

Two other potent risk factors for intussusception in children less than 1 year old were identified: a family history of intussusception, and an episode of gastroenteritis, Doris F. Oberle, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Oberle, of the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, presented a retrospective study of 116 meticulously validated cases of intussusception in infancy treated at 19 German pediatric centers during 2010-2014 and 272 controls matched by birth month, sex, and location. A standardized interview was conducted with the parents of all study participants.

Rotavirus vaccine was added to the German national vaccination schedule in 2013. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the risk of intussusception was increased by 5.4-fold following the first dose of the vaccine, compared with nonrecipients. However, subsequent doses of rotavirus vaccine were not associated with any excess risk.

In addition, a family history of intussusception was linked to a 4.2-fold increased risk, while an episode of gastroenteritis during the first year of life was associated with a 4.7-fold elevated risk.

In a novel finding, breastfeeding was independently associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of intussusception, compared with that of bottle-fed babies.

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of intussusception were vomiting, abdominal pain, hematochezia, pallor, and reduced appetite, each present in at least half of affected infants.

Dr. Oberle reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the Paul Ehrlich Institute.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Expanded indication being considered for meningococcal group B vaccine

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – under the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy designation.

Breakthrough Therapy status is reserved for accelerated review of therapies considered to show substantial preliminary promise of effectively targeting a major unmet medical need.

The unmet need here is that there is no meningococcal group B vaccine approved for use in children under age 10 years. Yet infants and children under 5 years of age are at greatest risk of invasive meningococcal B disease, with reported case fatality rates of 8%-9%, Jason D. Maguire, MD, noted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Trumenba has been approved in the United States for patients aged 10-25 years and in the European Union for individuals aged 10 years or older.

Dr. Maguire, of Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development program, presented the results of the two phase 2 randomized safety and immunogenicity trials conducted in patients aged 1- 9 years that the company has submitted to the FDA in support of the expanded indication. One study was carried out in 352 1-year-old toddlers, the other in 400 children aged 2-9 years, whose mean age was 4 years. The studies were carried out in Australia, Finland, Poland, and the Czech Republic.

In a pooled analysis of the vaccine’s immunogenicity when administered in a three-dose schedule of 120 mcg at 0, 2, and 6 months to 193 toddlers and 274 of the children aged 2-9 years, robust bactericidal antibody responses were seen against the four major Neisseria meningitidis group B strains that cause invasive disease. In fact, at least a fourfold rise in titers from baseline to 1 month after dose three was documented in the same high proportion of 1- to 9-year-olds as previously seen in the phase 3 trials that led to vaccine licensure in adolescents and young adults.

“These results support that the use of Trumenba, when given to children ages 1 to less than 10 years at the same dose and schedule that is currently approved in adolescents and young adults, can afford a high degree of protective antibody responses that correlate with immunity in this population,” Dr. Maguire said.

The safety and tolerability analysis included all 752 children in the two phase 2 studies, including the 110 toddlers randomized to three 60-mcg doses of the vaccine, although it has subsequently become clear that 120 mcg is the dose that provides the best immunogenicity with an acceptable safety profile, according to the physician.

Across the age groups, local reactions, including redness and swelling, were more common in Trumenba recipients than in controls who received hepatitis A vaccine and saline injections. So were systemic adverse events. Fever – a systemic event of particular interest to parents and clinicians – occurred in 37% of toddlers after vaccination, compared with 25% of 2- to 9-year-olds and 10%-12% of controls. Of note, prophylactic antipyretics weren’t allowed in the study.

“There’s somewhat of an inverse relationship between age and temperature. So as we go down in age, the rate of fever rises. But after each subsequent dose, regardless of age, there’s a reduction in the incidence of fever,” Dr. Maguire observed.

Most fevers were less than 39.0° C. Only 3 of 752 (less than 1%) patients experienced fever in excess of 40.0° C.

Two children withdrew from the study after developing hip synovitis, which was transient. Another withdrew because of prolonged irritability, fatigue, and decreased appetite.

“Although Trumenba had an acceptable safety and tolerability profile in 1- to 9-year-olds, this analysis wasn’t powered enough to detect uncommon adverse events, so we’ll continue to monitor safety for things like synovitis,” he said.

In 10- to 25-year-olds, the meningococcal vaccine can be given concomitantly with other vaccines without interference. There are plans to study concurrent vaccination with MMR and pneumococcal vaccines in 1- to 9-year-olds as well, according to Dr. Maguire.

Pfizer also now is planning clinical trials of the vaccine in infants, another important group currently unprotected against meningococcal group B disease, he added.

Dr. Maguire is an employee of Pfizer, who funded the studies.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – under the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy designation.

Breakthrough Therapy status is reserved for accelerated review of therapies considered to show substantial preliminary promise of effectively targeting a major unmet medical need.

The unmet need here is that there is no meningococcal group B vaccine approved for use in children under age 10 years. Yet infants and children under 5 years of age are at greatest risk of invasive meningococcal B disease, with reported case fatality rates of 8%-9%, Jason D. Maguire, MD, noted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Trumenba has been approved in the United States for patients aged 10-25 years and in the European Union for individuals aged 10 years or older.

Dr. Maguire, of Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development program, presented the results of the two phase 2 randomized safety and immunogenicity trials conducted in patients aged 1- 9 years that the company has submitted to the FDA in support of the expanded indication. One study was carried out in 352 1-year-old toddlers, the other in 400 children aged 2-9 years, whose mean age was 4 years. The studies were carried out in Australia, Finland, Poland, and the Czech Republic.

In a pooled analysis of the vaccine’s immunogenicity when administered in a three-dose schedule of 120 mcg at 0, 2, and 6 months to 193 toddlers and 274 of the children aged 2-9 years, robust bactericidal antibody responses were seen against the four major Neisseria meningitidis group B strains that cause invasive disease. In fact, at least a fourfold rise in titers from baseline to 1 month after dose three was documented in the same high proportion of 1- to 9-year-olds as previously seen in the phase 3 trials that led to vaccine licensure in adolescents and young adults.

“These results support that the use of Trumenba, when given to children ages 1 to less than 10 years at the same dose and schedule that is currently approved in adolescents and young adults, can afford a high degree of protective antibody responses that correlate with immunity in this population,” Dr. Maguire said.

The safety and tolerability analysis included all 752 children in the two phase 2 studies, including the 110 toddlers randomized to three 60-mcg doses of the vaccine, although it has subsequently become clear that 120 mcg is the dose that provides the best immunogenicity with an acceptable safety profile, according to the physician.

Across the age groups, local reactions, including redness and swelling, were more common in Trumenba recipients than in controls who received hepatitis A vaccine and saline injections. So were systemic adverse events. Fever – a systemic event of particular interest to parents and clinicians – occurred in 37% of toddlers after vaccination, compared with 25% of 2- to 9-year-olds and 10%-12% of controls. Of note, prophylactic antipyretics weren’t allowed in the study.

“There’s somewhat of an inverse relationship between age and temperature. So as we go down in age, the rate of fever rises. But after each subsequent dose, regardless of age, there’s a reduction in the incidence of fever,” Dr. Maguire observed.

Most fevers were less than 39.0° C. Only 3 of 752 (less than 1%) patients experienced fever in excess of 40.0° C.

Two children withdrew from the study after developing hip synovitis, which was transient. Another withdrew because of prolonged irritability, fatigue, and decreased appetite.

“Although Trumenba had an acceptable safety and tolerability profile in 1- to 9-year-olds, this analysis wasn’t powered enough to detect uncommon adverse events, so we’ll continue to monitor safety for things like synovitis,” he said.

In 10- to 25-year-olds, the meningococcal vaccine can be given concomitantly with other vaccines without interference. There are plans to study concurrent vaccination with MMR and pneumococcal vaccines in 1- to 9-year-olds as well, according to Dr. Maguire.

Pfizer also now is planning clinical trials of the vaccine in infants, another important group currently unprotected against meningococcal group B disease, he added.

Dr. Maguire is an employee of Pfizer, who funded the studies.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – under the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy designation.

Breakthrough Therapy status is reserved for accelerated review of therapies considered to show substantial preliminary promise of effectively targeting a major unmet medical need.

The unmet need here is that there is no meningococcal group B vaccine approved for use in children under age 10 years. Yet infants and children under 5 years of age are at greatest risk of invasive meningococcal B disease, with reported case fatality rates of 8%-9%, Jason D. Maguire, MD, noted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Trumenba has been approved in the United States for patients aged 10-25 years and in the European Union for individuals aged 10 years or older.

Dr. Maguire, of Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development program, presented the results of the two phase 2 randomized safety and immunogenicity trials conducted in patients aged 1- 9 years that the company has submitted to the FDA in support of the expanded indication. One study was carried out in 352 1-year-old toddlers, the other in 400 children aged 2-9 years, whose mean age was 4 years. The studies were carried out in Australia, Finland, Poland, and the Czech Republic.

In a pooled analysis of the vaccine’s immunogenicity when administered in a three-dose schedule of 120 mcg at 0, 2, and 6 months to 193 toddlers and 274 of the children aged 2-9 years, robust bactericidal antibody responses were seen against the four major Neisseria meningitidis group B strains that cause invasive disease. In fact, at least a fourfold rise in titers from baseline to 1 month after dose three was documented in the same high proportion of 1- to 9-year-olds as previously seen in the phase 3 trials that led to vaccine licensure in adolescents and young adults.

“These results support that the use of Trumenba, when given to children ages 1 to less than 10 years at the same dose and schedule that is currently approved in adolescents and young adults, can afford a high degree of protective antibody responses that correlate with immunity in this population,” Dr. Maguire said.

The safety and tolerability analysis included all 752 children in the two phase 2 studies, including the 110 toddlers randomized to three 60-mcg doses of the vaccine, although it has subsequently become clear that 120 mcg is the dose that provides the best immunogenicity with an acceptable safety profile, according to the physician.

Across the age groups, local reactions, including redness and swelling, were more common in Trumenba recipients than in controls who received hepatitis A vaccine and saline injections. So were systemic adverse events. Fever – a systemic event of particular interest to parents and clinicians – occurred in 37% of toddlers after vaccination, compared with 25% of 2- to 9-year-olds and 10%-12% of controls. Of note, prophylactic antipyretics weren’t allowed in the study.

“There’s somewhat of an inverse relationship between age and temperature. So as we go down in age, the rate of fever rises. But after each subsequent dose, regardless of age, there’s a reduction in the incidence of fever,” Dr. Maguire observed.

Most fevers were less than 39.0° C. Only 3 of 752 (less than 1%) patients experienced fever in excess of 40.0° C.

Two children withdrew from the study after developing hip synovitis, which was transient. Another withdrew because of prolonged irritability, fatigue, and decreased appetite.

“Although Trumenba had an acceptable safety and tolerability profile in 1- to 9-year-olds, this analysis wasn’t powered enough to detect uncommon adverse events, so we’ll continue to monitor safety for things like synovitis,” he said.

In 10- to 25-year-olds, the meningococcal vaccine can be given concomitantly with other vaccines without interference. There are plans to study concurrent vaccination with MMR and pneumococcal vaccines in 1- to 9-year-olds as well, according to Dr. Maguire.

Pfizer also now is planning clinical trials of the vaccine in infants, another important group currently unprotected against meningococcal group B disease, he added.

Dr. Maguire is an employee of Pfizer, who funded the studies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

Five rules for evaluating melanonychia

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Many dermatologists find melanonychia to be intimidating. The clinical features are ambiguous, and the prospect of doing a painful nail apparatus biopsy can be daunting for the inexperienced. As a result, the biopsy gets delayed and melanoma of the nail is often initially a missed diagnosis, not uncommonly for years, with devastating consequences.

Here are five at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Rule #1: Always look beyond the nail

When a light-skinned person presents with more than one nail with pigmentation, the likelihood that one of them is melanoma is much less than if there is only one nail with melanonychia, according to Dr. Jellinek, a dermatologist in private practice in East Greenwich, R.I.

Also, be sure to look at the skin and mucosa. Consider the medications the patients may be taking: For example, cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) is notorious for causing nail changes as a side effect. A past medical history of lichen planus, carpal tunnel syndrome, Addison disease, or other conditions may explain the melanonychia.

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is a condition worth getting to know. It’s an acquired disorder characterized longitudinal melanonychia and other pigmentary changes, which may include diffuse hyperpigmentation of the orolabial mucosa, ocular pigment, and/or pigmented palmoplantar lesions. It’s said to be rare, but Dr. Jellinek disagrees.

“Learn this one if you don’t know it. I see a case about every 2 weeks. It’s not heritable and not associated with any other medical condition,” he said.

Rule #2: Your dermatoscope is great for nails

What Dr. Jellinek considers to be among the all-time best papers on the value of dermoscopy for nail pigmentation was authored by French investigators. They analyzed 148 consecutive cases of longitudinal melanonychia and concluded that the dermoscopic combination of a brown background coupled with irregular longitudinal lines in terms of color, spacing, diameter, and/or lack of parallelism strongly suggests melanoma. A micro-Hutchinson’s sign, while a rare finding, occurred only in melanoma, where it represented periungual spread of a radial growth phase malignancy (Arch Dermatol. 2002 Oct;138[10]:1327-33).

“I think nail dermoscopy is most helpful for subungual hemorrhage. I average one referral per week for hemorrhage under the nail. On dermoscopy it’s as if someone took paint and threw it at the nail. Purple to brown blood spots, with no background color. This should be a doorway diagnosis of hemorrhage,” Dr. Jellinek said.

Rule #3: Know when you don’t know

“This is really the key for me,” the dermatologist commented. “There are automatic cases for biopsy, and more commonly routine cases for reassurance. But the gray zone, when you know you don’t know, is the key decision making moment.”

When something just doesn’t feel right, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with getting a second opinion, he stressed.

“It’s worthwhile getting to know people whose opinions you trust. There’s a saying I like to teach our fellows: ‘Never worry alone.’ So if you’re worried about someone, listen to that inner voice. There’s no shame in getting a second opinion. It’s great! Patients are never upset, either. They feel really well taken care of,” he said.

Rule #4: Don’t wimp out when a biopsy is warranted

Many dermatologists hem and haw about doing a biopsy for a concerning lesion on the nail, when they wouldn’t hesitate to biopsy a similarly suspicious lesion on the face.

But it’s essential to biopsy the right area, he added. For longitudinal melanonychia, that’s the matrix. The nail plate is the wrong place; a biopsy obtained there will result in an inappropriate benign diagnosis.

“The starter set is to do a punch biopsy. This is your gateway drug to the world of nail surgery. Lots of dermatologists are intimidated by nail surgery, but if you can do any minor surgery, you can do a punch of the matrix. All it takes is a little practice. And if all you can do is punch biopsies, you’re good for your career. If you can do that, you’re golden. There are people who’ve just done punch biopsies for their whole career and they don’t miss melanomas,” he said.

Step one is to undermine the proximal nail fold using a pediatric elevator, which costs only about $30. “If you’re going to do a lot of nail surgery, they’re really helpful,” he said.

There’s no need at all to evulse the nail. Just make oblique incisions in the proximal nail fold in order to reflect it and look at the matrix. A 3-mm punch is standard, directed right over the origin of the pigment. Resist the temptation to force or squeeze the specimen in order to extract it. Instead, use really fine-tipped scissors to nibble at the base of the specimen, then gently pull it out, making an effort to keep the nail plate attached to the digit and avoid getting it stuck up in the punch.

Rule #5: Have dermatopathologists extensively experienced with nail pathology on your Rolodex

The histopathologic findings present in early subungual melanoma in situ are often too subtle for general dermatopathologists to appreciate, in Dr. Jellinek’s experience. He cited other investigators’ study of 18 cases of subungual melanoma in situ, all marked by longitudinal melanonychia. Only half showed the classic giveaway on the original nail matrix biopsy, consisting of a significantly increased number of atypical melanocytes with marked nuclear atypia. Blatant pagetoid spread was infrequent. However, all 18 cases displayed a novel, more subtle, and previously undescribed finding: haphazard and uneven distribution of atypical solitary melanocytes with variably sized and shaped hyperchromatic nuclei (J Cutan Pathol. 2016 Jan;43[1]:41-52).

Dr. Jellinek reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation. SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Many dermatologists find melanonychia to be intimidating. The clinical features are ambiguous, and the prospect of doing a painful nail apparatus biopsy can be daunting for the inexperienced. As a result, the biopsy gets delayed and melanoma of the nail is often initially a missed diagnosis, not uncommonly for years, with devastating consequences.

Here are five at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Rule #1: Always look beyond the nail

When a light-skinned person presents with more than one nail with pigmentation, the likelihood that one of them is melanoma is much less than if there is only one nail with melanonychia, according to Dr. Jellinek, a dermatologist in private practice in East Greenwich, R.I.

Also, be sure to look at the skin and mucosa. Consider the medications the patients may be taking: For example, cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) is notorious for causing nail changes as a side effect. A past medical history of lichen planus, carpal tunnel syndrome, Addison disease, or other conditions may explain the melanonychia.

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is a condition worth getting to know. It’s an acquired disorder characterized longitudinal melanonychia and other pigmentary changes, which may include diffuse hyperpigmentation of the orolabial mucosa, ocular pigment, and/or pigmented palmoplantar lesions. It’s said to be rare, but Dr. Jellinek disagrees.

“Learn this one if you don’t know it. I see a case about every 2 weeks. It’s not heritable and not associated with any other medical condition,” he said.

Rule #2: Your dermatoscope is great for nails

What Dr. Jellinek considers to be among the all-time best papers on the value of dermoscopy for nail pigmentation was authored by French investigators. They analyzed 148 consecutive cases of longitudinal melanonychia and concluded that the dermoscopic combination of a brown background coupled with irregular longitudinal lines in terms of color, spacing, diameter, and/or lack of parallelism strongly suggests melanoma. A micro-Hutchinson’s sign, while a rare finding, occurred only in melanoma, where it represented periungual spread of a radial growth phase malignancy (Arch Dermatol. 2002 Oct;138[10]:1327-33).

“I think nail dermoscopy is most helpful for subungual hemorrhage. I average one referral per week for hemorrhage under the nail. On dermoscopy it’s as if someone took paint and threw it at the nail. Purple to brown blood spots, with no background color. This should be a doorway diagnosis of hemorrhage,” Dr. Jellinek said.

Rule #3: Know when you don’t know

“This is really the key for me,” the dermatologist commented. “There are automatic cases for biopsy, and more commonly routine cases for reassurance. But the gray zone, when you know you don’t know, is the key decision making moment.”

When something just doesn’t feel right, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with getting a second opinion, he stressed.

“It’s worthwhile getting to know people whose opinions you trust. There’s a saying I like to teach our fellows: ‘Never worry alone.’ So if you’re worried about someone, listen to that inner voice. There’s no shame in getting a second opinion. It’s great! Patients are never upset, either. They feel really well taken care of,” he said.

Rule #4: Don’t wimp out when a biopsy is warranted

Many dermatologists hem and haw about doing a biopsy for a concerning lesion on the nail, when they wouldn’t hesitate to biopsy a similarly suspicious lesion on the face.

But it’s essential to biopsy the right area, he added. For longitudinal melanonychia, that’s the matrix. The nail plate is the wrong place; a biopsy obtained there will result in an inappropriate benign diagnosis.

“The starter set is to do a punch biopsy. This is your gateway drug to the world of nail surgery. Lots of dermatologists are intimidated by nail surgery, but if you can do any minor surgery, you can do a punch of the matrix. All it takes is a little practice. And if all you can do is punch biopsies, you’re good for your career. If you can do that, you’re golden. There are people who’ve just done punch biopsies for their whole career and they don’t miss melanomas,” he said.

Step one is to undermine the proximal nail fold using a pediatric elevator, which costs only about $30. “If you’re going to do a lot of nail surgery, they’re really helpful,” he said.

There’s no need at all to evulse the nail. Just make oblique incisions in the proximal nail fold in order to reflect it and look at the matrix. A 3-mm punch is standard, directed right over the origin of the pigment. Resist the temptation to force or squeeze the specimen in order to extract it. Instead, use really fine-tipped scissors to nibble at the base of the specimen, then gently pull it out, making an effort to keep the nail plate attached to the digit and avoid getting it stuck up in the punch.

Rule #5: Have dermatopathologists extensively experienced with nail pathology on your Rolodex

The histopathologic findings present in early subungual melanoma in situ are often too subtle for general dermatopathologists to appreciate, in Dr. Jellinek’s experience. He cited other investigators’ study of 18 cases of subungual melanoma in situ, all marked by longitudinal melanonychia. Only half showed the classic giveaway on the original nail matrix biopsy, consisting of a significantly increased number of atypical melanocytes with marked nuclear atypia. Blatant pagetoid spread was infrequent. However, all 18 cases displayed a novel, more subtle, and previously undescribed finding: haphazard and uneven distribution of atypical solitary melanocytes with variably sized and shaped hyperchromatic nuclei (J Cutan Pathol. 2016 Jan;43[1]:41-52).

Dr. Jellinek reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation. SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Many dermatologists find melanonychia to be intimidating. The clinical features are ambiguous, and the prospect of doing a painful nail apparatus biopsy can be daunting for the inexperienced. As a result, the biopsy gets delayed and melanoma of the nail is often initially a missed diagnosis, not uncommonly for years, with devastating consequences.

Here are five at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Rule #1: Always look beyond the nail

When a light-skinned person presents with more than one nail with pigmentation, the likelihood that one of them is melanoma is much less than if there is only one nail with melanonychia, according to Dr. Jellinek, a dermatologist in private practice in East Greenwich, R.I.

Also, be sure to look at the skin and mucosa. Consider the medications the patients may be taking: For example, cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) is notorious for causing nail changes as a side effect. A past medical history of lichen planus, carpal tunnel syndrome, Addison disease, or other conditions may explain the melanonychia.

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is a condition worth getting to know. It’s an acquired disorder characterized longitudinal melanonychia and other pigmentary changes, which may include diffuse hyperpigmentation of the orolabial mucosa, ocular pigment, and/or pigmented palmoplantar lesions. It’s said to be rare, but Dr. Jellinek disagrees.

“Learn this one if you don’t know it. I see a case about every 2 weeks. It’s not heritable and not associated with any other medical condition,” he said.

Rule #2: Your dermatoscope is great for nails

What Dr. Jellinek considers to be among the all-time best papers on the value of dermoscopy for nail pigmentation was authored by French investigators. They analyzed 148 consecutive cases of longitudinal melanonychia and concluded that the dermoscopic combination of a brown background coupled with irregular longitudinal lines in terms of color, spacing, diameter, and/or lack of parallelism strongly suggests melanoma. A micro-Hutchinson’s sign, while a rare finding, occurred only in melanoma, where it represented periungual spread of a radial growth phase malignancy (Arch Dermatol. 2002 Oct;138[10]:1327-33).

“I think nail dermoscopy is most helpful for subungual hemorrhage. I average one referral per week for hemorrhage under the nail. On dermoscopy it’s as if someone took paint and threw it at the nail. Purple to brown blood spots, with no background color. This should be a doorway diagnosis of hemorrhage,” Dr. Jellinek said.

Rule #3: Know when you don’t know

“This is really the key for me,” the dermatologist commented. “There are automatic cases for biopsy, and more commonly routine cases for reassurance. But the gray zone, when you know you don’t know, is the key decision making moment.”

When something just doesn’t feel right, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with getting a second opinion, he stressed.

“It’s worthwhile getting to know people whose opinions you trust. There’s a saying I like to teach our fellows: ‘Never worry alone.’ So if you’re worried about someone, listen to that inner voice. There’s no shame in getting a second opinion. It’s great! Patients are never upset, either. They feel really well taken care of,” he said.

Rule #4: Don’t wimp out when a biopsy is warranted

Many dermatologists hem and haw about doing a biopsy for a concerning lesion on the nail, when they wouldn’t hesitate to biopsy a similarly suspicious lesion on the face.

But it’s essential to biopsy the right area, he added. For longitudinal melanonychia, that’s the matrix. The nail plate is the wrong place; a biopsy obtained there will result in an inappropriate benign diagnosis.

“The starter set is to do a punch biopsy. This is your gateway drug to the world of nail surgery. Lots of dermatologists are intimidated by nail surgery, but if you can do any minor surgery, you can do a punch of the matrix. All it takes is a little practice. And if all you can do is punch biopsies, you’re good for your career. If you can do that, you’re golden. There are people who’ve just done punch biopsies for their whole career and they don’t miss melanomas,” he said.

Step one is to undermine the proximal nail fold using a pediatric elevator, which costs only about $30. “If you’re going to do a lot of nail surgery, they’re really helpful,” he said.

There’s no need at all to evulse the nail. Just make oblique incisions in the proximal nail fold in order to reflect it and look at the matrix. A 3-mm punch is standard, directed right over the origin of the pigment. Resist the temptation to force or squeeze the specimen in order to extract it. Instead, use really fine-tipped scissors to nibble at the base of the specimen, then gently pull it out, making an effort to keep the nail plate attached to the digit and avoid getting it stuck up in the punch.

Rule #5: Have dermatopathologists extensively experienced with nail pathology on your Rolodex

The histopathologic findings present in early subungual melanoma in situ are often too subtle for general dermatopathologists to appreciate, in Dr. Jellinek’s experience. He cited other investigators’ study of 18 cases of subungual melanoma in situ, all marked by longitudinal melanonychia. Only half showed the classic giveaway on the original nail matrix biopsy, consisting of a significantly increased number of atypical melanocytes with marked nuclear atypia. Blatant pagetoid spread was infrequent. However, all 18 cases displayed a novel, more subtle, and previously undescribed finding: haphazard and uneven distribution of atypical solitary melanocytes with variably sized and shaped hyperchromatic nuclei (J Cutan Pathol. 2016 Jan;43[1]:41-52).

Dr. Jellinek reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation. SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Methotrexate significantly reduced knee OA pain

TORONTO – Philip G. Conaghan, MD, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

There is, however, an asterisk attached to these findings. “Despite a moderate standard effect size, the treatment effect was smaller than some of the thresholds for what is considered clinically meaningful,” he noted at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

That being said, the rheumatologist is convinced further investigation of methotrexate in osteoarthritis is warranted.

“I have to say that, unlike our earlier hydroxychloroquine trial, which was robustly negative with nothing more to say, I think there is a signal in this study. I need to understand the results of this trial better to understand if there is a subgroup we could treat with methotrexate. It’s a cheap drug, it’s readily available, and we’ve got a lot of experience with it,” noted Dr. Conaghan, professor of musculoskeletal medicine at the University of Leeds (England) and director of the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine.

The rationale for the 15-center PROMOTE trial is that synovitis is common in OA. Synovitis is associated with pain, methotrexate is the gold-standard treatment for synovitis in inflammatory forms of arthritis, and current treatments for OA are, to say the least, severely limited. Also, an earlier 30-patient, open-label pilot study of methotrexate in patients with painful knee OA conducted by Dr. Conaghan and coworkers suggested the drug was promising (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2013 May;52[5]:888-92).

PROMOTE included 134 patients with symptomatic and radiographic knee OA who were randomized in double-blind fashion to 6 months of oral methotrexate at 10 mg titrated to a target dose of 25 mg/week or to placebo. All patients also received usual care with oral NSAIDs and/or acetaminophen. Their mean baseline knee pain on a 0-10 numeric rating scale was 6.6.

The primary endpoint, assessed at 6 months, was the difference between the two study arms in average knee pain during the previous week on a 0-10 scale. The score was 5.1 in the methotrexate group and 6.2 in the placebo arm, for a baseline-adjusted treatment difference of 0.83 points, which works out to a standard effect size of 0.36. When the data were reanalyzed after excluding the 15 patients who missed more than four doses of medication within any 3-month period, the between-group difference in pain scores increased to 0.95 points in favor of the methotrexate group.

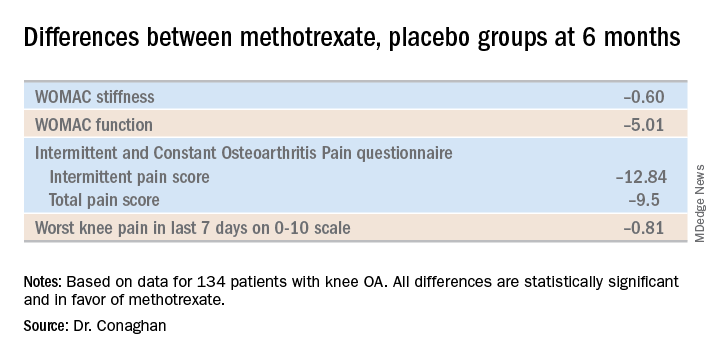

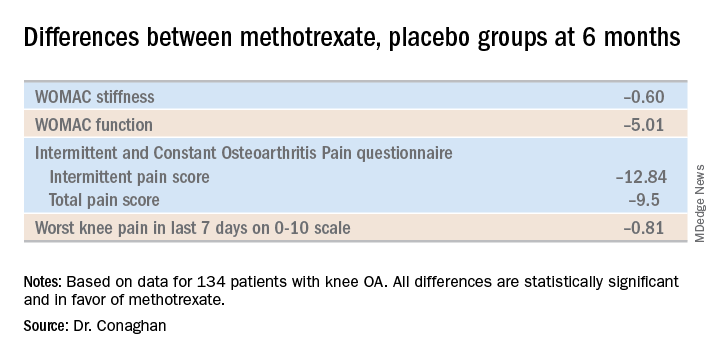

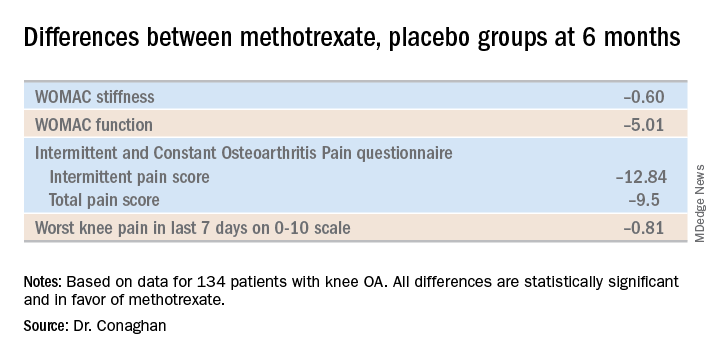

A significant difference in favor of the methotrexate group was documented in the OARSI-OMERACT response rate at 6 months: 45% in the methotrexate group and 26% in the controls. Some secondary endpoints were positive as well, with statistically significant differences seen at 6 months in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) stiffness, WOMAC physical function, and several other endpoints. But there were no significant differences in WOMAC pain, SF-12 physical component or SF-12 mental component scores, or in an OA quality of life measure.

The mean dose of methotrexate used in the study was about 17 mg/week. Dr. Conaghan said that if he could do the trial over again, he would have used subcutaneous methotrexate.

“It’s a more reliable way of getting a dose into people and probably of getting a slightly higher dose into people. In the rheumatoid arthritis world, we use a lot more subcutaneous methotrexate now than we did 10 years ago because it gets around a lot of the minor side effects and helps compliance,” he said.

One audience member suggested that one potentially useful way to zero in on a subgroup of knee OA patients likely to derive the most benefit from methotrexate would be to have screened potential study participants for comorbid fibromyalgia and exclude those with the disorder. Dr. Conaghan replied that the PROMOTE investigators did gather data on participants’ pain at sites other than the knee. That data can be used to identify those at increased likelihood of fibromyalgia, and he agreed that’s worth looking into.

Dr. Conaghan reported having no financial conflicts regarding PROMOTE, which was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and Versus Arthritis.

SOURCE: Conaghan PG et al. OARSI 2019, Abstract 86.

TORONTO – Philip G. Conaghan, MD, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

There is, however, an asterisk attached to these findings. “Despite a moderate standard effect size, the treatment effect was smaller than some of the thresholds for what is considered clinically meaningful,” he noted at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

That being said, the rheumatologist is convinced further investigation of methotrexate in osteoarthritis is warranted.

“I have to say that, unlike our earlier hydroxychloroquine trial, which was robustly negative with nothing more to say, I think there is a signal in this study. I need to understand the results of this trial better to understand if there is a subgroup we could treat with methotrexate. It’s a cheap drug, it’s readily available, and we’ve got a lot of experience with it,” noted Dr. Conaghan, professor of musculoskeletal medicine at the University of Leeds (England) and director of the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine.

The rationale for the 15-center PROMOTE trial is that synovitis is common in OA. Synovitis is associated with pain, methotrexate is the gold-standard treatment for synovitis in inflammatory forms of arthritis, and current treatments for OA are, to say the least, severely limited. Also, an earlier 30-patient, open-label pilot study of methotrexate in patients with painful knee OA conducted by Dr. Conaghan and coworkers suggested the drug was promising (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2013 May;52[5]:888-92).

PROMOTE included 134 patients with symptomatic and radiographic knee OA who were randomized in double-blind fashion to 6 months of oral methotrexate at 10 mg titrated to a target dose of 25 mg/week or to placebo. All patients also received usual care with oral NSAIDs and/or acetaminophen. Their mean baseline knee pain on a 0-10 numeric rating scale was 6.6.

The primary endpoint, assessed at 6 months, was the difference between the two study arms in average knee pain during the previous week on a 0-10 scale. The score was 5.1 in the methotrexate group and 6.2 in the placebo arm, for a baseline-adjusted treatment difference of 0.83 points, which works out to a standard effect size of 0.36. When the data were reanalyzed after excluding the 15 patients who missed more than four doses of medication within any 3-month period, the between-group difference in pain scores increased to 0.95 points in favor of the methotrexate group.

A significant difference in favor of the methotrexate group was documented in the OARSI-OMERACT response rate at 6 months: 45% in the methotrexate group and 26% in the controls. Some secondary endpoints were positive as well, with statistically significant differences seen at 6 months in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) stiffness, WOMAC physical function, and several other endpoints. But there were no significant differences in WOMAC pain, SF-12 physical component or SF-12 mental component scores, or in an OA quality of life measure.

The mean dose of methotrexate used in the study was about 17 mg/week. Dr. Conaghan said that if he could do the trial over again, he would have used subcutaneous methotrexate.

“It’s a more reliable way of getting a dose into people and probably of getting a slightly higher dose into people. In the rheumatoid arthritis world, we use a lot more subcutaneous methotrexate now than we did 10 years ago because it gets around a lot of the minor side effects and helps compliance,” he said.

One audience member suggested that one potentially useful way to zero in on a subgroup of knee OA patients likely to derive the most benefit from methotrexate would be to have screened potential study participants for comorbid fibromyalgia and exclude those with the disorder. Dr. Conaghan replied that the PROMOTE investigators did gather data on participants’ pain at sites other than the knee. That data can be used to identify those at increased likelihood of fibromyalgia, and he agreed that’s worth looking into.

Dr. Conaghan reported having no financial conflicts regarding PROMOTE, which was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and Versus Arthritis.

SOURCE: Conaghan PG et al. OARSI 2019, Abstract 86.

TORONTO – Philip G. Conaghan, MD, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

There is, however, an asterisk attached to these findings. “Despite a moderate standard effect size, the treatment effect was smaller than some of the thresholds for what is considered clinically meaningful,” he noted at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

That being said, the rheumatologist is convinced further investigation of methotrexate in osteoarthritis is warranted.

“I have to say that, unlike our earlier hydroxychloroquine trial, which was robustly negative with nothing more to say, I think there is a signal in this study. I need to understand the results of this trial better to understand if there is a subgroup we could treat with methotrexate. It’s a cheap drug, it’s readily available, and we’ve got a lot of experience with it,” noted Dr. Conaghan, professor of musculoskeletal medicine at the University of Leeds (England) and director of the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine.

The rationale for the 15-center PROMOTE trial is that synovitis is common in OA. Synovitis is associated with pain, methotrexate is the gold-standard treatment for synovitis in inflammatory forms of arthritis, and current treatments for OA are, to say the least, severely limited. Also, an earlier 30-patient, open-label pilot study of methotrexate in patients with painful knee OA conducted by Dr. Conaghan and coworkers suggested the drug was promising (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2013 May;52[5]:888-92).

PROMOTE included 134 patients with symptomatic and radiographic knee OA who were randomized in double-blind fashion to 6 months of oral methotrexate at 10 mg titrated to a target dose of 25 mg/week or to placebo. All patients also received usual care with oral NSAIDs and/or acetaminophen. Their mean baseline knee pain on a 0-10 numeric rating scale was 6.6.

The primary endpoint, assessed at 6 months, was the difference between the two study arms in average knee pain during the previous week on a 0-10 scale. The score was 5.1 in the methotrexate group and 6.2 in the placebo arm, for a baseline-adjusted treatment difference of 0.83 points, which works out to a standard effect size of 0.36. When the data were reanalyzed after excluding the 15 patients who missed more than four doses of medication within any 3-month period, the between-group difference in pain scores increased to 0.95 points in favor of the methotrexate group.

A significant difference in favor of the methotrexate group was documented in the OARSI-OMERACT response rate at 6 months: 45% in the methotrexate group and 26% in the controls. Some secondary endpoints were positive as well, with statistically significant differences seen at 6 months in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) stiffness, WOMAC physical function, and several other endpoints. But there were no significant differences in WOMAC pain, SF-12 physical component or SF-12 mental component scores, or in an OA quality of life measure.

The mean dose of methotrexate used in the study was about 17 mg/week. Dr. Conaghan said that if he could do the trial over again, he would have used subcutaneous methotrexate.

“It’s a more reliable way of getting a dose into people and probably of getting a slightly higher dose into people. In the rheumatoid arthritis world, we use a lot more subcutaneous methotrexate now than we did 10 years ago because it gets around a lot of the minor side effects and helps compliance,” he said.

One audience member suggested that one potentially useful way to zero in on a subgroup of knee OA patients likely to derive the most benefit from methotrexate would be to have screened potential study participants for comorbid fibromyalgia and exclude those with the disorder. Dr. Conaghan replied that the PROMOTE investigators did gather data on participants’ pain at sites other than the knee. That data can be used to identify those at increased likelihood of fibromyalgia, and he agreed that’s worth looking into.

Dr. Conaghan reported having no financial conflicts regarding PROMOTE, which was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and Versus Arthritis.

SOURCE: Conaghan PG et al. OARSI 2019, Abstract 86.

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

Obesity doesn’t hamper flu vaccine response in pregnancy

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – ; indeed, it might actually improve their seroconversion rate, Michelle Clarke reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective cohort study of 90 women vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy, 24 of whom had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more. The impetus for the study was the investigators’ understanding that influenza in pregnancy carries an increased risk of severe complications, obesity is a known risk factor for more severe episodes of influenza, and vaccine responses could potentially be adversely affected by obesity, either because of the associated inflammatory state and altered cytokine profile or inadequate vaccine delivery via the intramuscular route. Yet the impact of obesity on vaccine responses in pregnancy has been unclear.

Blood samples obtained before and 1 month after vaccination showed similarly high-titer postvaccination seropositivity rates against influenza B, H3N2, and H1N1 regardless of the women’s weight status. Indeed, the seropositivity rate against all three influenza viruses was higher in the obese subgroup, by a margin of 92%-74%. Also, postvaccination geometric mean antibody titers were significantly higher in the obese group. Particularly impressive was the difference in H1N1 seroconversion, defined as a fourfold increase in titer 28 days after vaccination: 79% versus 55%, noted Ms. Clarke of the University of Adelaide.

Of note, influenza vaccination in the first trimester resulted in a significantly lower seropositive antibody rate than vaccination in the second or third trimesters. The implication is that gestational age at vaccination, regardless of BMI, may be an important determinant of optimal vaccine protection for mothers and their newborns. However, this tentative conclusion requires confirmation in an independent larger sample, because the patient numbers in the study were small: Seropositive antibodies to all three vaccine antigens were documented in just 7 of 12 women (58%) vaccinated in the first trimester, compared with 47 of 53 (89%) vaccinated in the second trimester and 18 of 25 (72%) in the third.

Ms. Clarke reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the Women’s and Children’s Hospital Research Foundation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – ; indeed, it might actually improve their seroconversion rate, Michelle Clarke reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective cohort study of 90 women vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy, 24 of whom had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more. The impetus for the study was the investigators’ understanding that influenza in pregnancy carries an increased risk of severe complications, obesity is a known risk factor for more severe episodes of influenza, and vaccine responses could potentially be adversely affected by obesity, either because of the associated inflammatory state and altered cytokine profile or inadequate vaccine delivery via the intramuscular route. Yet the impact of obesity on vaccine responses in pregnancy has been unclear.

Blood samples obtained before and 1 month after vaccination showed similarly high-titer postvaccination seropositivity rates against influenza B, H3N2, and H1N1 regardless of the women’s weight status. Indeed, the seropositivity rate against all three influenza viruses was higher in the obese subgroup, by a margin of 92%-74%. Also, postvaccination geometric mean antibody titers were significantly higher in the obese group. Particularly impressive was the difference in H1N1 seroconversion, defined as a fourfold increase in titer 28 days after vaccination: 79% versus 55%, noted Ms. Clarke of the University of Adelaide.

Of note, influenza vaccination in the first trimester resulted in a significantly lower seropositive antibody rate than vaccination in the second or third trimesters. The implication is that gestational age at vaccination, regardless of BMI, may be an important determinant of optimal vaccine protection for mothers and their newborns. However, this tentative conclusion requires confirmation in an independent larger sample, because the patient numbers in the study were small: Seropositive antibodies to all three vaccine antigens were documented in just 7 of 12 women (58%) vaccinated in the first trimester, compared with 47 of 53 (89%) vaccinated in the second trimester and 18 of 25 (72%) in the third.

Ms. Clarke reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the Women’s and Children’s Hospital Research Foundation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – ; indeed, it might actually improve their seroconversion rate, Michelle Clarke reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

She presented a prospective cohort study of 90 women vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy, 24 of whom had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more. The impetus for the study was the investigators’ understanding that influenza in pregnancy carries an increased risk of severe complications, obesity is a known risk factor for more severe episodes of influenza, and vaccine responses could potentially be adversely affected by obesity, either because of the associated inflammatory state and altered cytokine profile or inadequate vaccine delivery via the intramuscular route. Yet the impact of obesity on vaccine responses in pregnancy has been unclear.

Blood samples obtained before and 1 month after vaccination showed similarly high-titer postvaccination seropositivity rates against influenza B, H3N2, and H1N1 regardless of the women’s weight status. Indeed, the seropositivity rate against all three influenza viruses was higher in the obese subgroup, by a margin of 92%-74%. Also, postvaccination geometric mean antibody titers were significantly higher in the obese group. Particularly impressive was the difference in H1N1 seroconversion, defined as a fourfold increase in titer 28 days after vaccination: 79% versus 55%, noted Ms. Clarke of the University of Adelaide.

Of note, influenza vaccination in the first trimester resulted in a significantly lower seropositive antibody rate than vaccination in the second or third trimesters. The implication is that gestational age at vaccination, regardless of BMI, may be an important determinant of optimal vaccine protection for mothers and their newborns. However, this tentative conclusion requires confirmation in an independent larger sample, because the patient numbers in the study were small: Seropositive antibodies to all three vaccine antigens were documented in just 7 of 12 women (58%) vaccinated in the first trimester, compared with 47 of 53 (89%) vaccinated in the second trimester and 18 of 25 (72%) in the third.

Ms. Clarke reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the Women’s and Children’s Hospital Research Foundation.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Key clinical point: High BMI doesn’t impair influenza vaccine responses in pregnant women.

Major finding: Protective antibody levels against all three vaccine antigens were documented 1 month post vaccination in 92% of the obese and 74% of the nonobese mothers.

Study details: This was a prospective observational study of 90 women vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy, 24 of whom were obese.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the University of Adelaide Women’s and Children’s Hospital Research Foundation.

Some Brits snuff out TORCH screen to raise awareness of congenital syphilis

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Pediatricians in the south of England are so concerned about the recent national increase in the diagnosis of syphilis in adults and its ramifications for neonates that they’ve ditched the traditional TORCH newborn screen because the acronym doesn’t specifically remind clinicians to think about congenital syphilis, Mildred A. Iro, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“ explained Dr. Iro of the University of Southampton (England).

She highlighted salient features of three recent cases of congenital syphilis managed at Southampton Children’s Hospital.

“The key message that we’d like to share is that we just need to be more aware about congenital syphilis. Retest mothers if their risk factor status changes, and test suspected infants and children,” Dr. Iro said.

As a practical matter, however, even though current guidelines recommend retesting mothers whose risk factor status becomes heightened following an initial negative syphilis serology result early in pregnancy, clinicians often are unaware that a mother’s risk status has changed. And retesting all mothers during pregnancy isn’t attractive from a cost-benefit standpoint. This makes scrupulous screening of newborns all the more important. And yet TORCH, which stands for Toxoplasmosis, Other, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes infections, isn’t an acronym that promotes awareness of congenital syphilis, a disease which occupies an obscure position in TORCH under the “O” for “Other” heading. That’s why the term “congenital infection screen” has become the new norm in the south of England, she explained.

However, one pediatrician who didn’t consider congenital infection screen to be an improvement in terminology over TORCH had an alternative suggestion, which struck a favorable chord with his fellow audience members: Simply change the acronym to TORCHS, with the S standing for syphilis.

Dr. Iro noted that two of the three affected children were diagnosed at age 7-8 weeks. The third wasn’t diagnosed until age 15 months, when the mother tested positive for syphilis in a subsequent pregnancy. As is typical of the disease known as “the great masquerader,” while all three of the affected children were unwell early in infancy, they presented with a wide range of symptoms. Among the more prominent features were prolonged irritability, respiratory distress, odd rashes, anemia, hepatomegaly, and tachypnea. One infant had reduced movement and pain in one arm.

All three children underwent extensive testing. None had neurosyphilis. All achieved good outcomes on standard guideline-directed therapy.

As for the mothers, they were aged 19, 21, and 23 years when diagnosed with syphilis. All were Caucasian, and antenatal blood testing was negative in all three. None were retested during pregnancy, even though two of them had a male partner or former partner who was positive for syphilis, and the partner of the third disclosed to her that he had sex with men.

At diagnosis, all three women had a strongly positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, a high rapid plasma reagin, and a positive syphilis IgM assay.

Dr. Iro reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Pediatricians in the south of England are so concerned about the recent national increase in the diagnosis of syphilis in adults and its ramifications for neonates that they’ve ditched the traditional TORCH newborn screen because the acronym doesn’t specifically remind clinicians to think about congenital syphilis, Mildred A. Iro, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“ explained Dr. Iro of the University of Southampton (England).

She highlighted salient features of three recent cases of congenital syphilis managed at Southampton Children’s Hospital.

“The key message that we’d like to share is that we just need to be more aware about congenital syphilis. Retest mothers if their risk factor status changes, and test suspected infants and children,” Dr. Iro said.

As a practical matter, however, even though current guidelines recommend retesting mothers whose risk factor status becomes heightened following an initial negative syphilis serology result early in pregnancy, clinicians often are unaware that a mother’s risk status has changed. And retesting all mothers during pregnancy isn’t attractive from a cost-benefit standpoint. This makes scrupulous screening of newborns all the more important. And yet TORCH, which stands for Toxoplasmosis, Other, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes infections, isn’t an acronym that promotes awareness of congenital syphilis, a disease which occupies an obscure position in TORCH under the “O” for “Other” heading. That’s why the term “congenital infection screen” has become the new norm in the south of England, she explained.

However, one pediatrician who didn’t consider congenital infection screen to be an improvement in terminology over TORCH had an alternative suggestion, which struck a favorable chord with his fellow audience members: Simply change the acronym to TORCHS, with the S standing for syphilis.

Dr. Iro noted that two of the three affected children were diagnosed at age 7-8 weeks. The third wasn’t diagnosed until age 15 months, when the mother tested positive for syphilis in a subsequent pregnancy. As is typical of the disease known as “the great masquerader,” while all three of the affected children were unwell early in infancy, they presented with a wide range of symptoms. Among the more prominent features were prolonged irritability, respiratory distress, odd rashes, anemia, hepatomegaly, and tachypnea. One infant had reduced movement and pain in one arm.

All three children underwent extensive testing. None had neurosyphilis. All achieved good outcomes on standard guideline-directed therapy.

As for the mothers, they were aged 19, 21, and 23 years when diagnosed with syphilis. All were Caucasian, and antenatal blood testing was negative in all three. None were retested during pregnancy, even though two of them had a male partner or former partner who was positive for syphilis, and the partner of the third disclosed to her that he had sex with men.

At diagnosis, all three women had a strongly positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, a high rapid plasma reagin, and a positive syphilis IgM assay.

Dr. Iro reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Pediatricians in the south of England are so concerned about the recent national increase in the diagnosis of syphilis in adults and its ramifications for neonates that they’ve ditched the traditional TORCH newborn screen because the acronym doesn’t specifically remind clinicians to think about congenital syphilis, Mildred A. Iro, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“ explained Dr. Iro of the University of Southampton (England).

She highlighted salient features of three recent cases of congenital syphilis managed at Southampton Children’s Hospital.

“The key message that we’d like to share is that we just need to be more aware about congenital syphilis. Retest mothers if their risk factor status changes, and test suspected infants and children,” Dr. Iro said.

As a practical matter, however, even though current guidelines recommend retesting mothers whose risk factor status becomes heightened following an initial negative syphilis serology result early in pregnancy, clinicians often are unaware that a mother’s risk status has changed. And retesting all mothers during pregnancy isn’t attractive from a cost-benefit standpoint. This makes scrupulous screening of newborns all the more important. And yet TORCH, which stands for Toxoplasmosis, Other, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes infections, isn’t an acronym that promotes awareness of congenital syphilis, a disease which occupies an obscure position in TORCH under the “O” for “Other” heading. That’s why the term “congenital infection screen” has become the new norm in the south of England, she explained.

However, one pediatrician who didn’t consider congenital infection screen to be an improvement in terminology over TORCH had an alternative suggestion, which struck a favorable chord with his fellow audience members: Simply change the acronym to TORCHS, with the S standing for syphilis.

Dr. Iro noted that two of the three affected children were diagnosed at age 7-8 weeks. The third wasn’t diagnosed until age 15 months, when the mother tested positive for syphilis in a subsequent pregnancy. As is typical of the disease known as “the great masquerader,” while all three of the affected children were unwell early in infancy, they presented with a wide range of symptoms. Among the more prominent features were prolonged irritability, respiratory distress, odd rashes, anemia, hepatomegaly, and tachypnea. One infant had reduced movement and pain in one arm.

All three children underwent extensive testing. None had neurosyphilis. All achieved good outcomes on standard guideline-directed therapy.

As for the mothers, they were aged 19, 21, and 23 years when diagnosed with syphilis. All were Caucasian, and antenatal blood testing was negative in all three. None were retested during pregnancy, even though two of them had a male partner or former partner who was positive for syphilis, and the partner of the third disclosed to her that he had sex with men.

At diagnosis, all three women had a strongly positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, a high rapid plasma reagin, and a positive syphilis IgM assay.

Dr. Iro reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

C-section linked to serious infection in preschoolers

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Delivery by C-section – especially when elective – carries a significantly higher hospitalization risk for severe infection in the first 5 years of life than vaginal delivery in a study of nearly 7.3 million singleton deliveries in four asset-rich countries, David Burgner, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“This is something that obstetricians might need to consider when discussing with the family the pros and cons for an elective C-section, particularly one that isn’t otherwise indicated for the baby or the mother,” said Dr. Burgner of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

He presented an observational study of 7.29 million singleton births in Denmark, Great Britain, Scotland, and two Australian states during 1996-2015. C-section rates ranged from a low of 17.5% in Denmark to 29.4% in Western Australia, all of which are greater than the 10%-15% rate endorsed by the World Health Organization. Elective C-section rates varied by country from 39% to 57%. Of note, pediatric hospital care in all four countries is free, so economic considerations didn’t drive admission.

The impetus for this international collaboration was to gain new insight into the differential susceptibility to childhood infection, he explained.

“We know from our clinical practice that pretty much all of the children are exposed to pretty much all potentially serious pathogens during early life. And yet it’s only a minority that develop severe infection. It’s an extremely interesting scientific question and an extremely important clinical question as to what’s driving that differential susceptibility,” according to the pediatric infectious disease specialist.

There are a number of established risk factors for infection-related hospitalization in children, including parental smoking, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, and growth measurements at birth. Dr. Burgner and coinvestigators hypothesized that another important risk factor is the nature of the microbiome transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. This postnatal microbiome varies depending upon mode of delivery: Vaginal delivery transmits the maternal enteric microbiome, which they reasoned might be through direct immunomodulation that sets up protective immune responses early in life, especially against respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections. In contrast, delivery by C-section causes the baby to pick up the maternal skin and hospital environment microbiomes, but not the maternal enteric microbiome.

Thus, the investigators hypothesized that C-section poses a greater risk of infection-related hospitalization during the first 5 years of life than does vaginal delivery, and that elective C-section poses a higher risk than does emergency C-section because it is more likely to involve rupture of membranes.

The center-specific rates of C-section and infection-related pediatric infection, when combined into a meta-analysis, bore out the study hypothesis. Emergency C-section was associated with a 9% greater risk of infection-related hospitalization through 5 years of age than was vaginal delivery, while elective C-section was associated with a 13% increased risk, both of which were statistically significant and clinically important.

“We were quite taken with these results. We think they provide evidence that C-section is consistently associated with infection-related hospitalization. It’s an association study that can’t prove causality, but the results implicate the postnatal microbiome as the most plausible explanation in terms of what’s driving this association,” according to Dr. Burgner.