User login

How to Handle Questions About Vaccine Safety

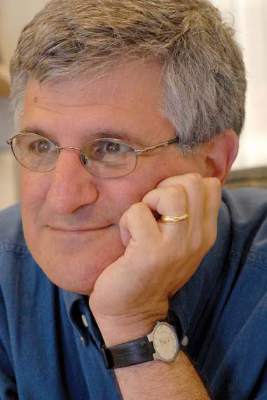

SAN DIEGO – Parental concerns about vaccine safety are a reality of pediatric practice. False perceptions that vaccines are dangerous or unnecessary have eroded herd immunity to the extent that almost 600 measles cases have been reported thus far in 2014 – an unprecedented number, Dr. Paul Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Offit recommended strategies for handling some of the most common questions and concerns parents raise about vaccine safety. He is director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is the Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

Parents may ask: How do you know vaccines are safe? I researched them on the Internet and learned they’re not.

“When people say they’ve done their research on a vaccine and have decided not to get it, what they really mean is they’ve read other people’s opinions on the Internet,” Dr. Offit said. Parents need to understand that not all information sources are equivalent, and that a vaccine must undergo extensive testing before the Food and Drug Administration licenses it or the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend it, he said. “The phase III trials invariably involve thousands of children,” he added.

But the package insert for the vaccine lists a lot of adverse events.

Any adverse event reported before the vaccine is licensed will be listed on the package insert, whether or not the vaccine caused the event, Dr. Offit said. For example, the original package insert for the chicken pox (varicella) vaccine listed fractured leg as an adverse event, because one recipient of the varicella vaccine broke his or her leg within 42 days after receiving the vaccine, he said. “Package inserts are not a medical communication document,” he added. “They are a legal communication document.”

Why are people being compensated for vaccine harm if it isn’t a problem?

The question refers to the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in compensation awards to petitioners since 1989. The program is “a large and tempting pool of money for personal injury lawyers to file compensatory injury suits on behalf of their clients,” Dr. Offit said. But just because a court awarded damages for harm does not mean the vaccine actually caused harm, he said. “The courts are never a place to determine scientific truths. The place you do that is in the scientific venue, by studies.”

Vaccines can contain potential allergens, primarily gelatin (a stabilizer) and latex (in vials or syringes that contain natural rubber), Dr. Offit noted. However, the rate of truly severe reactions to vaccines is extremely low – about one case per 1-2 million doses of vaccine, he said. An exception is yellow fever vaccine , which has caused fatal anaphylaxis, and oral polio vaccine also “had the potential to revert to wild type, which is why we went to the fully inactivated polio vaccine by the year 2000,” Dr. Offit noted. Thrombocytopenia is a potential adverse reaction of some vaccines, but is rare, and there are no compelling data associating measles vaccine with encephalopathy, he said.

The fact of the matter is that vaccines are a product of pharmaceutical companies. Why should I trust a product that is from a pharmaceutical company?

“The fact is you don’t have to trust pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Offit said. “A reporting system for adverse events is out there – VAERS [Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System]. The vaccination safety data will show whether or not there is a safety issue.”

As an example, the human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 vaccine was studied in millions of children after it was licensed in the United States, Dr. Offit said. “The only symptom found was fainting,” he emphasized.

“It’s also not good business to make a vaccine that will do harm,” Dr. Offit said, adding that prelicensure studies of vaccines have cost up to $600 million.

I heard that if I am pregnant, I should not get the flu vaccine because it contains mercury, which is neurotoxic and can harm my baby.

Parents can benefit from understanding the difference between methylmercury – which naturally occurs in the environment and is neurotoxic at high levels of exposure – and ethylmercury, which is formed when the body breaks down the thimerosal that is found in small amounts in some vaccines, Dr. Offit said. Ethylmercury poses much less risk to humans than methylmercury, because it is excreted from the body about 10 times faster, he added.

“Mercury is in the earth’s crust, and always has been in inorganic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If you live on this planet, if you drink anything made from water on this planet, you will be exposed to methylmercury. The quantity of mercury that you ingest every day is logarithmically greater than anything you would get from vaccines. You are at no greater risk of neurodevelopmental problems, including autism, from being vaccinated than if you did not receive any vaccines containing thimerosal.”

Parents may argue that drinking a substance is different from injecting it, but in fact, “mercury is very well absorbed in organic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If it’s ingested, it will cross cell membranes.”

And while thimerosal-free vaccines are available, “advertising these vaccines as safer is not true,” because the small amounts of thimerosal in current vaccines do not pose a health risk, Dr. Offit said.

Why is my child getting hepatitis B vaccine at birth? My child won’t be at risk for a long time.

“The hepatitis B vaccine first came on the market in the early 1980s, and was originally recommended only for high-risk groups,” Dr. Offit said. “For 10 years, the incidence of hepatitis B in this country did not budge. Then it was recommended as a routine vaccination for newborns, because every year, there were 18,000 cases of hepatitis B in kids under 10 years old.” Only half these cases were a result of exposure to hepatitis B virus in the vaginal canal during delivery, he emphasized. The rest resulted from “casual contact with someone who was infected and did not know it, such as a kiss on the lips from an uncle.”

Parents also should understand that chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with a high risk of liver cancer or cirrhosis, Dr. Offit said.

I’m Catholic, and I see that a number of vaccines contain cells that are from aborted fetuses.

In the early 1960s, cells from elective abortions in Sweden and England were used to make vaccines such as hepatitis A, varicella, rubella, and rabies, Dr. Offit noted. Some vaccines are still made in cells that have grown or descended independently from these aborted fetuses, he said. The Catholic Church teaches that Catholics should ask for alternatives when available, but are morally free to use vaccines prepared in cells descended from aborted fetuses, because the greater harm is to the unvaccinated child. The National Catholic Bioethics Center, which derives its teachings directly from the Catholic Church, states, “ The risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concern about the origins of the vaccine. This is especially important for parents, who have a moral obligation to protect the life and health of their children and those around them.”

I don’t want my child to receive vaccines because natural infection is better for the immune system.

The infections against which vaccines protect can be fatal, cause serious illness, and lead to long-term disability, Dr. Offit emphasized. “The fact is that vaccines are good enough,” he emphasized. “The immunity is good enough. You just need it to be good enough to protect you long-term.”

SAN DIEGO – Parental concerns about vaccine safety are a reality of pediatric practice. False perceptions that vaccines are dangerous or unnecessary have eroded herd immunity to the extent that almost 600 measles cases have been reported thus far in 2014 – an unprecedented number, Dr. Paul Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Offit recommended strategies for handling some of the most common questions and concerns parents raise about vaccine safety. He is director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is the Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

Parents may ask: How do you know vaccines are safe? I researched them on the Internet and learned they’re not.

“When people say they’ve done their research on a vaccine and have decided not to get it, what they really mean is they’ve read other people’s opinions on the Internet,” Dr. Offit said. Parents need to understand that not all information sources are equivalent, and that a vaccine must undergo extensive testing before the Food and Drug Administration licenses it or the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend it, he said. “The phase III trials invariably involve thousands of children,” he added.

But the package insert for the vaccine lists a lot of adverse events.

Any adverse event reported before the vaccine is licensed will be listed on the package insert, whether or not the vaccine caused the event, Dr. Offit said. For example, the original package insert for the chicken pox (varicella) vaccine listed fractured leg as an adverse event, because one recipient of the varicella vaccine broke his or her leg within 42 days after receiving the vaccine, he said. “Package inserts are not a medical communication document,” he added. “They are a legal communication document.”

Why are people being compensated for vaccine harm if it isn’t a problem?

The question refers to the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in compensation awards to petitioners since 1989. The program is “a large and tempting pool of money for personal injury lawyers to file compensatory injury suits on behalf of their clients,” Dr. Offit said. But just because a court awarded damages for harm does not mean the vaccine actually caused harm, he said. “The courts are never a place to determine scientific truths. The place you do that is in the scientific venue, by studies.”

Vaccines can contain potential allergens, primarily gelatin (a stabilizer) and latex (in vials or syringes that contain natural rubber), Dr. Offit noted. However, the rate of truly severe reactions to vaccines is extremely low – about one case per 1-2 million doses of vaccine, he said. An exception is yellow fever vaccine , which has caused fatal anaphylaxis, and oral polio vaccine also “had the potential to revert to wild type, which is why we went to the fully inactivated polio vaccine by the year 2000,” Dr. Offit noted. Thrombocytopenia is a potential adverse reaction of some vaccines, but is rare, and there are no compelling data associating measles vaccine with encephalopathy, he said.

The fact of the matter is that vaccines are a product of pharmaceutical companies. Why should I trust a product that is from a pharmaceutical company?

“The fact is you don’t have to trust pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Offit said. “A reporting system for adverse events is out there – VAERS [Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System]. The vaccination safety data will show whether or not there is a safety issue.”

As an example, the human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 vaccine was studied in millions of children after it was licensed in the United States, Dr. Offit said. “The only symptom found was fainting,” he emphasized.

“It’s also not good business to make a vaccine that will do harm,” Dr. Offit said, adding that prelicensure studies of vaccines have cost up to $600 million.

I heard that if I am pregnant, I should not get the flu vaccine because it contains mercury, which is neurotoxic and can harm my baby.

Parents can benefit from understanding the difference between methylmercury – which naturally occurs in the environment and is neurotoxic at high levels of exposure – and ethylmercury, which is formed when the body breaks down the thimerosal that is found in small amounts in some vaccines, Dr. Offit said. Ethylmercury poses much less risk to humans than methylmercury, because it is excreted from the body about 10 times faster, he added.

“Mercury is in the earth’s crust, and always has been in inorganic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If you live on this planet, if you drink anything made from water on this planet, you will be exposed to methylmercury. The quantity of mercury that you ingest every day is logarithmically greater than anything you would get from vaccines. You are at no greater risk of neurodevelopmental problems, including autism, from being vaccinated than if you did not receive any vaccines containing thimerosal.”

Parents may argue that drinking a substance is different from injecting it, but in fact, “mercury is very well absorbed in organic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If it’s ingested, it will cross cell membranes.”

And while thimerosal-free vaccines are available, “advertising these vaccines as safer is not true,” because the small amounts of thimerosal in current vaccines do not pose a health risk, Dr. Offit said.

Why is my child getting hepatitis B vaccine at birth? My child won’t be at risk for a long time.

“The hepatitis B vaccine first came on the market in the early 1980s, and was originally recommended only for high-risk groups,” Dr. Offit said. “For 10 years, the incidence of hepatitis B in this country did not budge. Then it was recommended as a routine vaccination for newborns, because every year, there were 18,000 cases of hepatitis B in kids under 10 years old.” Only half these cases were a result of exposure to hepatitis B virus in the vaginal canal during delivery, he emphasized. The rest resulted from “casual contact with someone who was infected and did not know it, such as a kiss on the lips from an uncle.”

Parents also should understand that chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with a high risk of liver cancer or cirrhosis, Dr. Offit said.

I’m Catholic, and I see that a number of vaccines contain cells that are from aborted fetuses.

In the early 1960s, cells from elective abortions in Sweden and England were used to make vaccines such as hepatitis A, varicella, rubella, and rabies, Dr. Offit noted. Some vaccines are still made in cells that have grown or descended independently from these aborted fetuses, he said. The Catholic Church teaches that Catholics should ask for alternatives when available, but are morally free to use vaccines prepared in cells descended from aborted fetuses, because the greater harm is to the unvaccinated child. The National Catholic Bioethics Center, which derives its teachings directly from the Catholic Church, states, “ The risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concern about the origins of the vaccine. This is especially important for parents, who have a moral obligation to protect the life and health of their children and those around them.”

I don’t want my child to receive vaccines because natural infection is better for the immune system.

The infections against which vaccines protect can be fatal, cause serious illness, and lead to long-term disability, Dr. Offit emphasized. “The fact is that vaccines are good enough,” he emphasized. “The immunity is good enough. You just need it to be good enough to protect you long-term.”

SAN DIEGO – Parental concerns about vaccine safety are a reality of pediatric practice. False perceptions that vaccines are dangerous or unnecessary have eroded herd immunity to the extent that almost 600 measles cases have been reported thus far in 2014 – an unprecedented number, Dr. Paul Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Offit recommended strategies for handling some of the most common questions and concerns parents raise about vaccine safety. He is director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is the Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

Parents may ask: How do you know vaccines are safe? I researched them on the Internet and learned they’re not.

“When people say they’ve done their research on a vaccine and have decided not to get it, what they really mean is they’ve read other people’s opinions on the Internet,” Dr. Offit said. Parents need to understand that not all information sources are equivalent, and that a vaccine must undergo extensive testing before the Food and Drug Administration licenses it or the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend it, he said. “The phase III trials invariably involve thousands of children,” he added.

But the package insert for the vaccine lists a lot of adverse events.

Any adverse event reported before the vaccine is licensed will be listed on the package insert, whether or not the vaccine caused the event, Dr. Offit said. For example, the original package insert for the chicken pox (varicella) vaccine listed fractured leg as an adverse event, because one recipient of the varicella vaccine broke his or her leg within 42 days after receiving the vaccine, he said. “Package inserts are not a medical communication document,” he added. “They are a legal communication document.”

Why are people being compensated for vaccine harm if it isn’t a problem?

The question refers to the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in compensation awards to petitioners since 1989. The program is “a large and tempting pool of money for personal injury lawyers to file compensatory injury suits on behalf of their clients,” Dr. Offit said. But just because a court awarded damages for harm does not mean the vaccine actually caused harm, he said. “The courts are never a place to determine scientific truths. The place you do that is in the scientific venue, by studies.”

Vaccines can contain potential allergens, primarily gelatin (a stabilizer) and latex (in vials or syringes that contain natural rubber), Dr. Offit noted. However, the rate of truly severe reactions to vaccines is extremely low – about one case per 1-2 million doses of vaccine, he said. An exception is yellow fever vaccine , which has caused fatal anaphylaxis, and oral polio vaccine also “had the potential to revert to wild type, which is why we went to the fully inactivated polio vaccine by the year 2000,” Dr. Offit noted. Thrombocytopenia is a potential adverse reaction of some vaccines, but is rare, and there are no compelling data associating measles vaccine with encephalopathy, he said.

The fact of the matter is that vaccines are a product of pharmaceutical companies. Why should I trust a product that is from a pharmaceutical company?

“The fact is you don’t have to trust pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Offit said. “A reporting system for adverse events is out there – VAERS [Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System]. The vaccination safety data will show whether or not there is a safety issue.”

As an example, the human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 vaccine was studied in millions of children after it was licensed in the United States, Dr. Offit said. “The only symptom found was fainting,” he emphasized.

“It’s also not good business to make a vaccine that will do harm,” Dr. Offit said, adding that prelicensure studies of vaccines have cost up to $600 million.

I heard that if I am pregnant, I should not get the flu vaccine because it contains mercury, which is neurotoxic and can harm my baby.

Parents can benefit from understanding the difference between methylmercury – which naturally occurs in the environment and is neurotoxic at high levels of exposure – and ethylmercury, which is formed when the body breaks down the thimerosal that is found in small amounts in some vaccines, Dr. Offit said. Ethylmercury poses much less risk to humans than methylmercury, because it is excreted from the body about 10 times faster, he added.

“Mercury is in the earth’s crust, and always has been in inorganic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If you live on this planet, if you drink anything made from water on this planet, you will be exposed to methylmercury. The quantity of mercury that you ingest every day is logarithmically greater than anything you would get from vaccines. You are at no greater risk of neurodevelopmental problems, including autism, from being vaccinated than if you did not receive any vaccines containing thimerosal.”

Parents may argue that drinking a substance is different from injecting it, but in fact, “mercury is very well absorbed in organic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If it’s ingested, it will cross cell membranes.”

And while thimerosal-free vaccines are available, “advertising these vaccines as safer is not true,” because the small amounts of thimerosal in current vaccines do not pose a health risk, Dr. Offit said.

Why is my child getting hepatitis B vaccine at birth? My child won’t be at risk for a long time.

“The hepatitis B vaccine first came on the market in the early 1980s, and was originally recommended only for high-risk groups,” Dr. Offit said. “For 10 years, the incidence of hepatitis B in this country did not budge. Then it was recommended as a routine vaccination for newborns, because every year, there were 18,000 cases of hepatitis B in kids under 10 years old.” Only half these cases were a result of exposure to hepatitis B virus in the vaginal canal during delivery, he emphasized. The rest resulted from “casual contact with someone who was infected and did not know it, such as a kiss on the lips from an uncle.”

Parents also should understand that chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with a high risk of liver cancer or cirrhosis, Dr. Offit said.

I’m Catholic, and I see that a number of vaccines contain cells that are from aborted fetuses.

In the early 1960s, cells from elective abortions in Sweden and England were used to make vaccines such as hepatitis A, varicella, rubella, and rabies, Dr. Offit noted. Some vaccines are still made in cells that have grown or descended independently from these aborted fetuses, he said. The Catholic Church teaches that Catholics should ask for alternatives when available, but are morally free to use vaccines prepared in cells descended from aborted fetuses, because the greater harm is to the unvaccinated child. The National Catholic Bioethics Center, which derives its teachings directly from the Catholic Church, states, “ The risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concern about the origins of the vaccine. This is especially important for parents, who have a moral obligation to protect the life and health of their children and those around them.”

I don’t want my child to receive vaccines because natural infection is better for the immune system.

The infections against which vaccines protect can be fatal, cause serious illness, and lead to long-term disability, Dr. Offit emphasized. “The fact is that vaccines are good enough,” he emphasized. “The immunity is good enough. You just need it to be good enough to protect you long-term.”

How to handle questions about vaccine safety

SAN DIEGO – Parental concerns about vaccine safety are a reality of pediatric practice. False perceptions that vaccines are dangerous or unnecessary have eroded herd immunity to the extent that almost 600 measles cases have been reported thus far in 2014 – an unprecedented number, Dr. Paul Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Offit recommended strategies for handling some of the most common questions and concerns parents raise about vaccine safety. He is director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is the Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

Parents may ask: How do you know vaccines are safe? I researched them on the Internet and learned they’re not.

“When people say they’ve done their research on a vaccine and have decided not to get it, what they really mean is they’ve read other people’s opinions on the Internet,” Dr. Offit said. Parents need to understand that not all information sources are equivalent, and that a vaccine must undergo extensive testing before the Food and Drug Administration licenses it or the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend it, he said. “The phase III trials invariably involve thousands of children,” he added.

But the package insert for the vaccine lists a lot of adverse events.

Any adverse event reported before the vaccine is licensed will be listed on the package insert, whether or not the vaccine caused the event, Dr. Offit said. For example, the original package insert for the chicken pox (varicella) vaccine listed fractured leg as an adverse event, because one recipient of the varicella vaccine broke his or her leg within 42 days after receiving the vaccine, he said. “Package inserts are not a medical communication document,” he added. “They are a legal communication document.”

Why are people being compensated for vaccine harm if it isn’t a problem?

The question refers to the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in compensation awards to petitioners since 1989. The program is “a large and tempting pool of money for personal injury lawyers to file compensatory injury suits on behalf of their clients,” Dr. Offit said. But just because a court awarded damages for harm does not mean the vaccine actually caused harm, he said. “The courts are never a place to determine scientific truths. The place you do that is in the scientific venue, by studies.”

Vaccines can contain potential allergens, primarily gelatin (a stabilizer) and latex (in vials or syringes that contain natural rubber), Dr. Offit noted. However, the rate of truly severe reactions to vaccines is extremely low – about one case per 1-2 million doses of vaccine, he said. An exception is yellow fever vaccine , which has caused fatal anaphylaxis, and oral polio vaccine also “had the potential to revert to wild type, which is why we went to the fully inactivated polio vaccine by the year 2000,” Dr. Offit noted. Thrombocytopenia is a potential adverse reaction of some vaccines, but is rare, and there are no compelling data associating measles vaccine with encephalopathy, he said.

The fact of the matter is that vaccines are a product of pharmaceutical companies. Why should I trust a product that is from a pharmaceutical company?

“The fact is you don’t have to trust pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Offit said. “A reporting system for adverse events is out there – VAERS [Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System]. The vaccination safety data will show whether or not there is a safety issue.”

As an example, the human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 vaccine was studied in millions of children after it was licensed in the United States, Dr. Offit said. “The only symptom found was fainting,” he emphasized.

“It’s also not good business to make a vaccine that will do harm,” Dr. Offit said, adding that prelicensure studies of vaccines have cost up to $600 million.

I heard that if I am pregnant, I should not get the flu vaccine because it contains mercury, which is neurotoxic and can harm my baby.

Parents can benefit from understanding the difference between methylmercury – which naturally occurs in the environment and is neurotoxic at high levels of exposure – and ethylmercury, which is formed when the body breaks down the thimerosal that is found in small amounts in some vaccines, Dr. Offit said. Ethylmercury poses much less risk to humans than methylmercury, because it is excreted from the body about 10 times faster, he added.

“Mercury is in the earth’s crust, and always has been in inorganic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If you live on this planet, if you drink anything made from water on this planet, you will be exposed to methylmercury. The quantity of mercury that you ingest every day is logarithmically greater than anything you would get from vaccines. You are at no greater risk of neurodevelopmental problems, including autism, from being vaccinated than if you did not receive any vaccines containing thimerosal.”

Parents may argue that drinking a substance is different from injecting it, but in fact, “mercury is very well absorbed in organic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If it’s ingested, it will cross cell membranes.”

And while thimerosal-free vaccines are available, “advertising these vaccines as safer is not true,” because the small amounts of thimerosal in current vaccines do not pose a health risk, Dr. Offit said.

Why is my child getting hepatitis B vaccine at birth? My child won’t be at risk for a long time.

“The hepatitis B vaccine first came on the market in the early 1980s, and was originally recommended only for high-risk groups,” Dr. Offit said. “For 10 years, the incidence of hepatitis B in this country did not budge. Then it was recommended as a routine vaccination for newborns, because every year, there were 18,000 cases of hepatitis B in kids under 10 years old.” Only half these cases were a result of exposure to hepatitis B virus in the vaginal canal during delivery, he emphasized. The rest resulted from “casual contact with someone who was infected and did not know it, such as a kiss on the lips from an uncle.”

Parents also should understand that chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with a high risk of liver cancer or cirrhosis, Dr. Offit said.

I’m Catholic, and I see that a number of vaccines contain cells that are from aborted fetuses.

In the early 1960s, cells from elective abortions in Sweden and England were used to make vaccines such as hepatitis A, varicella, rubella, and rabies, Dr. Offit noted. Some vaccines are still made in cells that have grown or descended independently from these aborted fetuses, he said. The Catholic Church teaches that Catholics should ask for alternatives when available, but are morally free to use vaccines prepared in cells descended from aborted fetuses, because the greater harm is to the unvaccinated child. The National Catholic Bioethics Center, which derives its teachings directly from the Catholic Church, states, “ The risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concern about the origins of the vaccine. This is especially important for parents, who have a moral obligation to protect the life and health of their children and those around them.”

I don’t want my child to receive vaccines because natural infection is better for the immune system.

The infections against which vaccines protect can be fatal, cause serious illness, and lead to long-term disability, Dr. Offit emphasized. “The fact is that vaccines are good enough,” he emphasized. “The immunity is good enough. You just need it to be good enough to protect you long-term.”

SAN DIEGO – Parental concerns about vaccine safety are a reality of pediatric practice. False perceptions that vaccines are dangerous or unnecessary have eroded herd immunity to the extent that almost 600 measles cases have been reported thus far in 2014 – an unprecedented number, Dr. Paul Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Offit recommended strategies for handling some of the most common questions and concerns parents raise about vaccine safety. He is director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is the Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

Parents may ask: How do you know vaccines are safe? I researched them on the Internet and learned they’re not.

“When people say they’ve done their research on a vaccine and have decided not to get it, what they really mean is they’ve read other people’s opinions on the Internet,” Dr. Offit said. Parents need to understand that not all information sources are equivalent, and that a vaccine must undergo extensive testing before the Food and Drug Administration licenses it or the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend it, he said. “The phase III trials invariably involve thousands of children,” he added.

But the package insert for the vaccine lists a lot of adverse events.

Any adverse event reported before the vaccine is licensed will be listed on the package insert, whether or not the vaccine caused the event, Dr. Offit said. For example, the original package insert for the chicken pox (varicella) vaccine listed fractured leg as an adverse event, because one recipient of the varicella vaccine broke his or her leg within 42 days after receiving the vaccine, he said. “Package inserts are not a medical communication document,” he added. “They are a legal communication document.”

Why are people being compensated for vaccine harm if it isn’t a problem?

The question refers to the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in compensation awards to petitioners since 1989. The program is “a large and tempting pool of money for personal injury lawyers to file compensatory injury suits on behalf of their clients,” Dr. Offit said. But just because a court awarded damages for harm does not mean the vaccine actually caused harm, he said. “The courts are never a place to determine scientific truths. The place you do that is in the scientific venue, by studies.”

Vaccines can contain potential allergens, primarily gelatin (a stabilizer) and latex (in vials or syringes that contain natural rubber), Dr. Offit noted. However, the rate of truly severe reactions to vaccines is extremely low – about one case per 1-2 million doses of vaccine, he said. An exception is yellow fever vaccine , which has caused fatal anaphylaxis, and oral polio vaccine also “had the potential to revert to wild type, which is why we went to the fully inactivated polio vaccine by the year 2000,” Dr. Offit noted. Thrombocytopenia is a potential adverse reaction of some vaccines, but is rare, and there are no compelling data associating measles vaccine with encephalopathy, he said.

The fact of the matter is that vaccines are a product of pharmaceutical companies. Why should I trust a product that is from a pharmaceutical company?

“The fact is you don’t have to trust pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Offit said. “A reporting system for adverse events is out there – VAERS [Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System]. The vaccination safety data will show whether or not there is a safety issue.”

As an example, the human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 vaccine was studied in millions of children after it was licensed in the United States, Dr. Offit said. “The only symptom found was fainting,” he emphasized.

“It’s also not good business to make a vaccine that will do harm,” Dr. Offit said, adding that prelicensure studies of vaccines have cost up to $600 million.

I heard that if I am pregnant, I should not get the flu vaccine because it contains mercury, which is neurotoxic and can harm my baby.

Parents can benefit from understanding the difference between methylmercury – which naturally occurs in the environment and is neurotoxic at high levels of exposure – and ethylmercury, which is formed when the body breaks down the thimerosal that is found in small amounts in some vaccines, Dr. Offit said. Ethylmercury poses much less risk to humans than methylmercury, because it is excreted from the body about 10 times faster, he added.

“Mercury is in the earth’s crust, and always has been in inorganic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If you live on this planet, if you drink anything made from water on this planet, you will be exposed to methylmercury. The quantity of mercury that you ingest every day is logarithmically greater than anything you would get from vaccines. You are at no greater risk of neurodevelopmental problems, including autism, from being vaccinated than if you did not receive any vaccines containing thimerosal.”

Parents may argue that drinking a substance is different from injecting it, but in fact, “mercury is very well absorbed in organic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If it’s ingested, it will cross cell membranes.”

And while thimerosal-free vaccines are available, “advertising these vaccines as safer is not true,” because the small amounts of thimerosal in current vaccines do not pose a health risk, Dr. Offit said.

Why is my child getting hepatitis B vaccine at birth? My child won’t be at risk for a long time.

“The hepatitis B vaccine first came on the market in the early 1980s, and was originally recommended only for high-risk groups,” Dr. Offit said. “For 10 years, the incidence of hepatitis B in this country did not budge. Then it was recommended as a routine vaccination for newborns, because every year, there were 18,000 cases of hepatitis B in kids under 10 years old.” Only half these cases were a result of exposure to hepatitis B virus in the vaginal canal during delivery, he emphasized. The rest resulted from “casual contact with someone who was infected and did not know it, such as a kiss on the lips from an uncle.”

Parents also should understand that chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with a high risk of liver cancer or cirrhosis, Dr. Offit said.

I’m Catholic, and I see that a number of vaccines contain cells that are from aborted fetuses.

In the early 1960s, cells from elective abortions in Sweden and England were used to make vaccines such as hepatitis A, varicella, rubella, and rabies, Dr. Offit noted. Some vaccines are still made in cells that have grown or descended independently from these aborted fetuses, he said. The Catholic Church teaches that Catholics should ask for alternatives when available, but are morally free to use vaccines prepared in cells descended from aborted fetuses, because the greater harm is to the unvaccinated child. The National Catholic Bioethics Center, which derives its teachings directly from the Catholic Church, states, “ The risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concern about the origins of the vaccine. This is especially important for parents, who have a moral obligation to protect the life and health of their children and those around them.”

I don’t want my child to receive vaccines because natural infection is better for the immune system.

The infections against which vaccines protect can be fatal, cause serious illness, and lead to long-term disability, Dr. Offit emphasized. “The fact is that vaccines are good enough,” he emphasized. “The immunity is good enough. You just need it to be good enough to protect you long-term.”

SAN DIEGO – Parental concerns about vaccine safety are a reality of pediatric practice. False perceptions that vaccines are dangerous or unnecessary have eroded herd immunity to the extent that almost 600 measles cases have been reported thus far in 2014 – an unprecedented number, Dr. Paul Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Offit recommended strategies for handling some of the most common questions and concerns parents raise about vaccine safety. He is director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is the Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

Parents may ask: How do you know vaccines are safe? I researched them on the Internet and learned they’re not.

“When people say they’ve done their research on a vaccine and have decided not to get it, what they really mean is they’ve read other people’s opinions on the Internet,” Dr. Offit said. Parents need to understand that not all information sources are equivalent, and that a vaccine must undergo extensive testing before the Food and Drug Administration licenses it or the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend it, he said. “The phase III trials invariably involve thousands of children,” he added.

But the package insert for the vaccine lists a lot of adverse events.

Any adverse event reported before the vaccine is licensed will be listed on the package insert, whether or not the vaccine caused the event, Dr. Offit said. For example, the original package insert for the chicken pox (varicella) vaccine listed fractured leg as an adverse event, because one recipient of the varicella vaccine broke his or her leg within 42 days after receiving the vaccine, he said. “Package inserts are not a medical communication document,” he added. “They are a legal communication document.”

Why are people being compensated for vaccine harm if it isn’t a problem?

The question refers to the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in compensation awards to petitioners since 1989. The program is “a large and tempting pool of money for personal injury lawyers to file compensatory injury suits on behalf of their clients,” Dr. Offit said. But just because a court awarded damages for harm does not mean the vaccine actually caused harm, he said. “The courts are never a place to determine scientific truths. The place you do that is in the scientific venue, by studies.”

Vaccines can contain potential allergens, primarily gelatin (a stabilizer) and latex (in vials or syringes that contain natural rubber), Dr. Offit noted. However, the rate of truly severe reactions to vaccines is extremely low – about one case per 1-2 million doses of vaccine, he said. An exception is yellow fever vaccine , which has caused fatal anaphylaxis, and oral polio vaccine also “had the potential to revert to wild type, which is why we went to the fully inactivated polio vaccine by the year 2000,” Dr. Offit noted. Thrombocytopenia is a potential adverse reaction of some vaccines, but is rare, and there are no compelling data associating measles vaccine with encephalopathy, he said.

The fact of the matter is that vaccines are a product of pharmaceutical companies. Why should I trust a product that is from a pharmaceutical company?

“The fact is you don’t have to trust pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Offit said. “A reporting system for adverse events is out there – VAERS [Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System]. The vaccination safety data will show whether or not there is a safety issue.”

As an example, the human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 vaccine was studied in millions of children after it was licensed in the United States, Dr. Offit said. “The only symptom found was fainting,” he emphasized.

“It’s also not good business to make a vaccine that will do harm,” Dr. Offit said, adding that prelicensure studies of vaccines have cost up to $600 million.

I heard that if I am pregnant, I should not get the flu vaccine because it contains mercury, which is neurotoxic and can harm my baby.

Parents can benefit from understanding the difference between methylmercury – which naturally occurs in the environment and is neurotoxic at high levels of exposure – and ethylmercury, which is formed when the body breaks down the thimerosal that is found in small amounts in some vaccines, Dr. Offit said. Ethylmercury poses much less risk to humans than methylmercury, because it is excreted from the body about 10 times faster, he added.

“Mercury is in the earth’s crust, and always has been in inorganic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If you live on this planet, if you drink anything made from water on this planet, you will be exposed to methylmercury. The quantity of mercury that you ingest every day is logarithmically greater than anything you would get from vaccines. You are at no greater risk of neurodevelopmental problems, including autism, from being vaccinated than if you did not receive any vaccines containing thimerosal.”

Parents may argue that drinking a substance is different from injecting it, but in fact, “mercury is very well absorbed in organic form,” Dr. Offit said. “If it’s ingested, it will cross cell membranes.”

And while thimerosal-free vaccines are available, “advertising these vaccines as safer is not true,” because the small amounts of thimerosal in current vaccines do not pose a health risk, Dr. Offit said.

Why is my child getting hepatitis B vaccine at birth? My child won’t be at risk for a long time.

“The hepatitis B vaccine first came on the market in the early 1980s, and was originally recommended only for high-risk groups,” Dr. Offit said. “For 10 years, the incidence of hepatitis B in this country did not budge. Then it was recommended as a routine vaccination for newborns, because every year, there were 18,000 cases of hepatitis B in kids under 10 years old.” Only half these cases were a result of exposure to hepatitis B virus in the vaginal canal during delivery, he emphasized. The rest resulted from “casual contact with someone who was infected and did not know it, such as a kiss on the lips from an uncle.”

Parents also should understand that chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with a high risk of liver cancer or cirrhosis, Dr. Offit said.

I’m Catholic, and I see that a number of vaccines contain cells that are from aborted fetuses.

In the early 1960s, cells from elective abortions in Sweden and England were used to make vaccines such as hepatitis A, varicella, rubella, and rabies, Dr. Offit noted. Some vaccines are still made in cells that have grown or descended independently from these aborted fetuses, he said. The Catholic Church teaches that Catholics should ask for alternatives when available, but are morally free to use vaccines prepared in cells descended from aborted fetuses, because the greater harm is to the unvaccinated child. The National Catholic Bioethics Center, which derives its teachings directly from the Catholic Church, states, “ The risk to public health, if one chooses not to vaccinate, outweighs the legitimate concern about the origins of the vaccine. This is especially important for parents, who have a moral obligation to protect the life and health of their children and those around them.”

I don’t want my child to receive vaccines because natural infection is better for the immune system.

The infections against which vaccines protect can be fatal, cause serious illness, and lead to long-term disability, Dr. Offit emphasized. “The fact is that vaccines are good enough,” he emphasized. “The immunity is good enough. You just need it to be good enough to protect you long-term.”

Pediatric epilepsy linked to Axis I psychiatric disorders

SAN DIEGO – Children with recent-onset epilepsy were more than 2.5 more likely to have Axis I psychiatric disorders than were healthy controls in a prospective, case-control study.

“Children with epilepsy have a significant vulnerability to psychiatric comorbidity,” said Jana E. Jones, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “It will be important to study these children over multiple time points in order to begin to understand the trajectory of psychiatric disorders in epilepsy.”

At baseline, 17%-34% of children with epilepsy had depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), compared with 3%-16% of their age- and sex-matched first-degree cousins (P = .01 for all), the researchers found. Two years later, anxiety still occurred significantly more often among patients in the epilepsy group (31% vs. 10% for controls; P< .001), as did ADHD (19% vs. 4%, respectively; P = .01), they said. These differences remained significant for subgroups of children with focal and generalized epilepsy, compared with controls, Dr. Jones reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The prevalence of depression also remained higher in the epilepsy group at 2-year follow-up (8% vs. 3% for controls), but the difference was not statistically significant. Factors such as age of epilepsy onset, duration of seizures, and number of medications did not appear to affect the likelihood of Axis I disorders, the researchers said.

As recently as 2012, little was known about psychiatric comorbidities in children with epilepsy, said the investigators, noting that their study is the first prospective one of 2 years’ duration on the topic.

The study included 163 children aged 8-18 years. At baseline, all 92 children in the epilepsy group had been diagnosed in the past 12 months and had no other neurologic disorders or developmental disabilities. The researchers identified Axis I disorders by using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia.

The analysis also found that IQ scores for children with epilepsy averaged 100.8 points (standard deviation, 13.7), which was significantly lower than the mean of 108.4 (SD, 11.1) for the control group.

The National Institutes of Health supported the research. The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Children with recent-onset epilepsy were more than 2.5 more likely to have Axis I psychiatric disorders than were healthy controls in a prospective, case-control study.

“Children with epilepsy have a significant vulnerability to psychiatric comorbidity,” said Jana E. Jones, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “It will be important to study these children over multiple time points in order to begin to understand the trajectory of psychiatric disorders in epilepsy.”

At baseline, 17%-34% of children with epilepsy had depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), compared with 3%-16% of their age- and sex-matched first-degree cousins (P = .01 for all), the researchers found. Two years later, anxiety still occurred significantly more often among patients in the epilepsy group (31% vs. 10% for controls; P< .001), as did ADHD (19% vs. 4%, respectively; P = .01), they said. These differences remained significant for subgroups of children with focal and generalized epilepsy, compared with controls, Dr. Jones reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The prevalence of depression also remained higher in the epilepsy group at 2-year follow-up (8% vs. 3% for controls), but the difference was not statistically significant. Factors such as age of epilepsy onset, duration of seizures, and number of medications did not appear to affect the likelihood of Axis I disorders, the researchers said.

As recently as 2012, little was known about psychiatric comorbidities in children with epilepsy, said the investigators, noting that their study is the first prospective one of 2 years’ duration on the topic.

The study included 163 children aged 8-18 years. At baseline, all 92 children in the epilepsy group had been diagnosed in the past 12 months and had no other neurologic disorders or developmental disabilities. The researchers identified Axis I disorders by using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia.

The analysis also found that IQ scores for children with epilepsy averaged 100.8 points (standard deviation, 13.7), which was significantly lower than the mean of 108.4 (SD, 11.1) for the control group.

The National Institutes of Health supported the research. The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Children with recent-onset epilepsy were more than 2.5 more likely to have Axis I psychiatric disorders than were healthy controls in a prospective, case-control study.

“Children with epilepsy have a significant vulnerability to psychiatric comorbidity,” said Jana E. Jones, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “It will be important to study these children over multiple time points in order to begin to understand the trajectory of psychiatric disorders in epilepsy.”

At baseline, 17%-34% of children with epilepsy had depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), compared with 3%-16% of their age- and sex-matched first-degree cousins (P = .01 for all), the researchers found. Two years later, anxiety still occurred significantly more often among patients in the epilepsy group (31% vs. 10% for controls; P< .001), as did ADHD (19% vs. 4%, respectively; P = .01), they said. These differences remained significant for subgroups of children with focal and generalized epilepsy, compared with controls, Dr. Jones reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The prevalence of depression also remained higher in the epilepsy group at 2-year follow-up (8% vs. 3% for controls), but the difference was not statistically significant. Factors such as age of epilepsy onset, duration of seizures, and number of medications did not appear to affect the likelihood of Axis I disorders, the researchers said.

As recently as 2012, little was known about psychiatric comorbidities in children with epilepsy, said the investigators, noting that their study is the first prospective one of 2 years’ duration on the topic.

The study included 163 children aged 8-18 years. At baseline, all 92 children in the epilepsy group had been diagnosed in the past 12 months and had no other neurologic disorders or developmental disabilities. The researchers identified Axis I disorders by using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia.

The analysis also found that IQ scores for children with epilepsy averaged 100.8 points (standard deviation, 13.7), which was significantly lower than the mean of 108.4 (SD, 11.1) for the control group.

The National Institutes of Health supported the research. The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

AT THE AACAP ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Axis I psychiatric disorders in children with recent-onset epilepsy occur at significantly higher rates than in healthy controls and persist at higher levels through 2 years of follow-up.

Major finding: Rates of depression, anxiety, and ADHD in children with epilepsy ranged from 17% to 34%, compared with rates of 3%-16% for the control group (P = .01).

Data source: A prospective, case-control study of 92 children with recent-onset epilepsy and 71 healthy, first-degree cousins matched by age and sex.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health supported the research. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

Pediatricians recommend rear-facing car seats, but parents don’t always comply

SAN DIEGO – Three years after the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that children ride in rear-facing car seats until 2 years of age, almost 90% of pediatricians in Michigan were in compliance, an electronic survey found.

The study, the first of its type in Michigan, highlights “effective messaging, dissemination, and uptake of AAP guidelines,” reported lead researcher Dr. Sneha Rao of Hurley Medical Center, Flint, Mich., and her associates.

In 2011, the AAP upped its age recommendation for use of rear-facing car seats from 12 months (or 20 pounds of body weight) to 2 years of age (Pediatrics 2011;127:788-93), Dr. Rao noted. “Scientifically, the reason for the change is the reduction in impact,” she said in an interview at the annual meeting of the AAP. “It’s easier to treat a broken leg than a broken neck.”

Research shows rear-facing car seats are safer than front-facing seats for young children, including in side-on collisions. In one study, children under 24 months old who were seriously injured in side-on crashes were five times more likely to have been in a front-facing than a rear-facing seat (odds ratio, 5.53; 95% confidence interval, 3.74-8.18) (Inj. Prev. 2007;13:398-402). Side-on collisions often have a frontal component, which causes the child’s head to move further into the seat if rear facing, but away from the seat if front facing, the researchers said.Michigan and many other states also recommend or require that children ride in rear-facing safety seats until about age 2 years. But parents do not necessarily follow the recommendation, studies indicate. Earlier this year, authors of a direct-observation study carried out in Indiana reported that only about 60% of infants and toddlers up to 2 years old rode in rear-facing seats (Inj. Prev. 2014;20:226-31). And in Michigan, another direct-observation study found that 20%-25% of children were riding in a type of seat meant for an older child. Dr. Rao and associates found that only 39% of clinicians thought it was “very effective” to counsel parents of young children about automobile safety, although 73%-82% reported “always” doing so with newborns up to age 2 years, the researchers reported.

For their study, Dr. Rao and her associates sent an electronic survey to all pediatric care providers listed in the directory of the Michigan chapter of the AAP. The 146 respondents included pediatricians and generalists who mostly worked in outpatient settings, the investigators reported. More than 95% of physicians surveyed said they discussed automobile safety with parents of infants and toddlers, Dr. Rao and associates reported. Among 134 respondents to the question about rear-facing seats, 89.6% said they counseled parents to keep children in rear-facing seats until at least 2 years of age, the researchers found.

The AAP guidelines call for 2-year-olds to switch to a front-facing safety seat in the back seat. From ages 4-8 years, they are to use a booster seat and a safety belt. Older children should use lap and shoulder belts and should not ride in the front seat until at least age 13 years, the guidelines state.

The survey’s response rate was only 20%, and questions were not worded so that age categories were necessarily interpreted as mutually exclusive, Dr. Rao acknowledged. She reported no external funding sources of conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Three years after the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that children ride in rear-facing car seats until 2 years of age, almost 90% of pediatricians in Michigan were in compliance, an electronic survey found.

The study, the first of its type in Michigan, highlights “effective messaging, dissemination, and uptake of AAP guidelines,” reported lead researcher Dr. Sneha Rao of Hurley Medical Center, Flint, Mich., and her associates.

In 2011, the AAP upped its age recommendation for use of rear-facing car seats from 12 months (or 20 pounds of body weight) to 2 years of age (Pediatrics 2011;127:788-93), Dr. Rao noted. “Scientifically, the reason for the change is the reduction in impact,” she said in an interview at the annual meeting of the AAP. “It’s easier to treat a broken leg than a broken neck.”

Research shows rear-facing car seats are safer than front-facing seats for young children, including in side-on collisions. In one study, children under 24 months old who were seriously injured in side-on crashes were five times more likely to have been in a front-facing than a rear-facing seat (odds ratio, 5.53; 95% confidence interval, 3.74-8.18) (Inj. Prev. 2007;13:398-402). Side-on collisions often have a frontal component, which causes the child’s head to move further into the seat if rear facing, but away from the seat if front facing, the researchers said.Michigan and many other states also recommend or require that children ride in rear-facing safety seats until about age 2 years. But parents do not necessarily follow the recommendation, studies indicate. Earlier this year, authors of a direct-observation study carried out in Indiana reported that only about 60% of infants and toddlers up to 2 years old rode in rear-facing seats (Inj. Prev. 2014;20:226-31). And in Michigan, another direct-observation study found that 20%-25% of children were riding in a type of seat meant for an older child. Dr. Rao and associates found that only 39% of clinicians thought it was “very effective” to counsel parents of young children about automobile safety, although 73%-82% reported “always” doing so with newborns up to age 2 years, the researchers reported.

For their study, Dr. Rao and her associates sent an electronic survey to all pediatric care providers listed in the directory of the Michigan chapter of the AAP. The 146 respondents included pediatricians and generalists who mostly worked in outpatient settings, the investigators reported. More than 95% of physicians surveyed said they discussed automobile safety with parents of infants and toddlers, Dr. Rao and associates reported. Among 134 respondents to the question about rear-facing seats, 89.6% said they counseled parents to keep children in rear-facing seats until at least 2 years of age, the researchers found.

The AAP guidelines call for 2-year-olds to switch to a front-facing safety seat in the back seat. From ages 4-8 years, they are to use a booster seat and a safety belt. Older children should use lap and shoulder belts and should not ride in the front seat until at least age 13 years, the guidelines state.

The survey’s response rate was only 20%, and questions were not worded so that age categories were necessarily interpreted as mutually exclusive, Dr. Rao acknowledged. She reported no external funding sources of conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Three years after the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that children ride in rear-facing car seats until 2 years of age, almost 90% of pediatricians in Michigan were in compliance, an electronic survey found.

The study, the first of its type in Michigan, highlights “effective messaging, dissemination, and uptake of AAP guidelines,” reported lead researcher Dr. Sneha Rao of Hurley Medical Center, Flint, Mich., and her associates.

In 2011, the AAP upped its age recommendation for use of rear-facing car seats from 12 months (or 20 pounds of body weight) to 2 years of age (Pediatrics 2011;127:788-93), Dr. Rao noted. “Scientifically, the reason for the change is the reduction in impact,” she said in an interview at the annual meeting of the AAP. “It’s easier to treat a broken leg than a broken neck.”

Research shows rear-facing car seats are safer than front-facing seats for young children, including in side-on collisions. In one study, children under 24 months old who were seriously injured in side-on crashes were five times more likely to have been in a front-facing than a rear-facing seat (odds ratio, 5.53; 95% confidence interval, 3.74-8.18) (Inj. Prev. 2007;13:398-402). Side-on collisions often have a frontal component, which causes the child’s head to move further into the seat if rear facing, but away from the seat if front facing, the researchers said.Michigan and many other states also recommend or require that children ride in rear-facing safety seats until about age 2 years. But parents do not necessarily follow the recommendation, studies indicate. Earlier this year, authors of a direct-observation study carried out in Indiana reported that only about 60% of infants and toddlers up to 2 years old rode in rear-facing seats (Inj. Prev. 2014;20:226-31). And in Michigan, another direct-observation study found that 20%-25% of children were riding in a type of seat meant for an older child. Dr. Rao and associates found that only 39% of clinicians thought it was “very effective” to counsel parents of young children about automobile safety, although 73%-82% reported “always” doing so with newborns up to age 2 years, the researchers reported.

For their study, Dr. Rao and her associates sent an electronic survey to all pediatric care providers listed in the directory of the Michigan chapter of the AAP. The 146 respondents included pediatricians and generalists who mostly worked in outpatient settings, the investigators reported. More than 95% of physicians surveyed said they discussed automobile safety with parents of infants and toddlers, Dr. Rao and associates reported. Among 134 respondents to the question about rear-facing seats, 89.6% said they counseled parents to keep children in rear-facing seats until at least 2 years of age, the researchers found.

The AAP guidelines call for 2-year-olds to switch to a front-facing safety seat in the back seat. From ages 4-8 years, they are to use a booster seat and a safety belt. Older children should use lap and shoulder belts and should not ride in the front seat until at least age 13 years, the guidelines state.

The survey’s response rate was only 20%, and questions were not worded so that age categories were necessarily interpreted as mutually exclusive, Dr. Rao acknowledged. She reported no external funding sources of conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Most pediatricians surveyed in Michigan said they advised using rear-facing child car seats until children turned 2 years old.

Major finding: Among 134 respondents, 120 (89.6%) said they counseled parents to keep children in rear-facing safety seats at least until age 2 years.

Data source: Electronic survey of pediatricians and general practitioners in Michigan.

Disclosures: Dr. Rao reported no external funding sources of conflicts of interest.

Very low birthweight predicts mental health problems many years later

SAN DIEGO– Children of very low birthweight had higher rates of mental health disorders 10 to 14 years later than did age-matched controls, but teachers generally did not detect these differences, and instead their mental health assessments were associated with children’s socioeconomic status, a prospective study found.

The finding “has implications for mental health service access” and shows that teachers need education about the long-term mental health risks faced by very-low-birthweight (VLBW) children, said Dr. Fiona McNicholas, a visiting professor at Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates. Clinicians should routinely follow VLBW children and should promote early environmental enrichment for these children, the investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Dr. McNicholas and her associates studied 65 children in Dublin, Ireland, who averaged 11.6 years of age (range, 10-14 years) and had weighed less than 1,500 g, or 3.3 pounds, at birth. The investigators matched each VLBW child with the next child born in the same maternity ward who was of normal birthweight and the same sex. Children, their parents, and their teachers all responded to the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, http://www.sdqinfo.com/) regarding the children. The investigators also assessed the children using the Developmental Well-Being Assessment (http://www.dawba.com/), they said.Almost one-third (32%) of the VLBW cohort had a mental health diagnosis on the DAWBA, which resembled findings from a recent study in Norway (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22752364), reported Dr. McNicholas, also a professor of psychiatry at University College, Dublin. In contrast, only 14% of controls had a DAWBA diagnosis (P = .03), they said.

The rate of abnormal or clinical scores on the SDQ also was four to five times greater for VLBW children, compared with controls, based on child self-report (20% vs. 4%; P = .028) and parental report (32% vs. 8%; P = .007). Teachers “generally underreported pathology,” the investigators said, so scoring between the two groups (8% vs. 2%; P = .463) while large did not achieve statistical significance. The most common diagnosis was attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, which affected 17% of VLBW children and 8% of controls, the researchers added. Anxiety disorders were also common, and rates were slightly higher in VLBW children (12.5%) than among controls (9.8%).

In an analysis of variance test, teachers’ assessments of total SDQ scores depended on children’s socioeconomic status (P < .05) but not on birthweight, IQ score, or gender, reported Dr. McNicholas and her associates. “Initial investment needs to be met with ongoing surveillance and psychoeducation to ensure that disorders are recognized early and offered appropriate interventions,” the investigators concluded.

The overall rate of consent to participate among VLBW children was only 50%, and participants were of higher socioeconomic status than were nonparticipants (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Shire supported the research. The investigators reported advisory board relationships with Shire and received conference and travel support from the company. They declared no other conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO– Children of very low birthweight had higher rates of mental health disorders 10 to 14 years later than did age-matched controls, but teachers generally did not detect these differences, and instead their mental health assessments were associated with children’s socioeconomic status, a prospective study found.

The finding “has implications for mental health service access” and shows that teachers need education about the long-term mental health risks faced by very-low-birthweight (VLBW) children, said Dr. Fiona McNicholas, a visiting professor at Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates. Clinicians should routinely follow VLBW children and should promote early environmental enrichment for these children, the investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Dr. McNicholas and her associates studied 65 children in Dublin, Ireland, who averaged 11.6 years of age (range, 10-14 years) and had weighed less than 1,500 g, or 3.3 pounds, at birth. The investigators matched each VLBW child with the next child born in the same maternity ward who was of normal birthweight and the same sex. Children, their parents, and their teachers all responded to the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, http://www.sdqinfo.com/) regarding the children. The investigators also assessed the children using the Developmental Well-Being Assessment (http://www.dawba.com/), they said.Almost one-third (32%) of the VLBW cohort had a mental health diagnosis on the DAWBA, which resembled findings from a recent study in Norway (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22752364), reported Dr. McNicholas, also a professor of psychiatry at University College, Dublin. In contrast, only 14% of controls had a DAWBA diagnosis (P = .03), they said.

The rate of abnormal or clinical scores on the SDQ also was four to five times greater for VLBW children, compared with controls, based on child self-report (20% vs. 4%; P = .028) and parental report (32% vs. 8%; P = .007). Teachers “generally underreported pathology,” the investigators said, so scoring between the two groups (8% vs. 2%; P = .463) while large did not achieve statistical significance. The most common diagnosis was attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, which affected 17% of VLBW children and 8% of controls, the researchers added. Anxiety disorders were also common, and rates were slightly higher in VLBW children (12.5%) than among controls (9.8%).

In an analysis of variance test, teachers’ assessments of total SDQ scores depended on children’s socioeconomic status (P < .05) but not on birthweight, IQ score, or gender, reported Dr. McNicholas and her associates. “Initial investment needs to be met with ongoing surveillance and psychoeducation to ensure that disorders are recognized early and offered appropriate interventions,” the investigators concluded.

The overall rate of consent to participate among VLBW children was only 50%, and participants were of higher socioeconomic status than were nonparticipants (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Shire supported the research. The investigators reported advisory board relationships with Shire and received conference and travel support from the company. They declared no other conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO– Children of very low birthweight had higher rates of mental health disorders 10 to 14 years later than did age-matched controls, but teachers generally did not detect these differences, and instead their mental health assessments were associated with children’s socioeconomic status, a prospective study found.

The finding “has implications for mental health service access” and shows that teachers need education about the long-term mental health risks faced by very-low-birthweight (VLBW) children, said Dr. Fiona McNicholas, a visiting professor at Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates. Clinicians should routinely follow VLBW children and should promote early environmental enrichment for these children, the investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Dr. McNicholas and her associates studied 65 children in Dublin, Ireland, who averaged 11.6 years of age (range, 10-14 years) and had weighed less than 1,500 g, or 3.3 pounds, at birth. The investigators matched each VLBW child with the next child born in the same maternity ward who was of normal birthweight and the same sex. Children, their parents, and their teachers all responded to the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, http://www.sdqinfo.com/) regarding the children. The investigators also assessed the children using the Developmental Well-Being Assessment (http://www.dawba.com/), they said.Almost one-third (32%) of the VLBW cohort had a mental health diagnosis on the DAWBA, which resembled findings from a recent study in Norway (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22752364), reported Dr. McNicholas, also a professor of psychiatry at University College, Dublin. In contrast, only 14% of controls had a DAWBA diagnosis (P = .03), they said.

The rate of abnormal or clinical scores on the SDQ also was four to five times greater for VLBW children, compared with controls, based on child self-report (20% vs. 4%; P = .028) and parental report (32% vs. 8%; P = .007). Teachers “generally underreported pathology,” the investigators said, so scoring between the two groups (8% vs. 2%; P = .463) while large did not achieve statistical significance. The most common diagnosis was attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, which affected 17% of VLBW children and 8% of controls, the researchers added. Anxiety disorders were also common, and rates were slightly higher in VLBW children (12.5%) than among controls (9.8%).

In an analysis of variance test, teachers’ assessments of total SDQ scores depended on children’s socioeconomic status (P < .05) but not on birthweight, IQ score, or gender, reported Dr. McNicholas and her associates. “Initial investment needs to be met with ongoing surveillance and psychoeducation to ensure that disorders are recognized early and offered appropriate interventions,” the investigators concluded.

The overall rate of consent to participate among VLBW children was only 50%, and participants were of higher socioeconomic status than were nonparticipants (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Shire supported the research. The investigators reported advisory board relationships with Shire and received conference and travel support from the company. They declared no other conflicts of interest.

AT THE AACAP ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Clinicians should routinely follow children born at very low birthweight and promote early environmental enrichment for them.

Major finding: In all, 32% of the VLBW cohort had a mental health diagnosis on the DAWBA, compared with 14% of normal-birthweight controls (P < .03).

Data source: Prospective cohort study of 64 children born at very low birthweight (< 1,500 g) and 51 healthy controls.

Disclosures: Shire provided research support. The researchers reported having advisory board relationships with Shire and receiving conference and travel support from the company. They declared no other conflicts of interest.

Extended telepsychiatry outperformed primary care follow-up for ADHD

SAN DIEGO– Six telepsychiatry sessions cut symptoms by at least half for 46% of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, compared with 13.6% of those who received one telepsychiatry session plus follow-up care by primary care providers, according to a randomized clinical trial.

The extended telepsychiatry intervention consistently outperformed primary care for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), including in subgroups of children with ADHD alone, comorbid anxiety disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, or both, said Dr. Carol M. Rockhill of Seattle Children’s Hospital. “We do think the results of this study justify a more extended consultation model. A single visit is not enough for a child to be stabilized,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity is one of the most common disorders of childhood, and children in rural areas often lack access to appropriate care. The Children’s ADHD Telemental Health Treatment Study (CATTS) included 223 children with ADHD and their primary caregivers at seven underserved sites in Washington and Oregon. The primary outcome was a 50% reduction in ADHD symptoms, “an ambitious goal,” Dr. Rockhill said. Average age of the patients was 9 years, and they did not have serious comorbid diagnoses such as autism, bipolar disorder, or conduct disorder, she said. In all, 18% of children had a diagnosis of ADHD alone, while the rest also had at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder, she said.

For the study, the intervention arm received a total of six telepsychiatry sessions provided by interactive televideo with psychiatrists at Seattle Children’s Hospital. All sites had high bandwidth connectivity, and equipment that could pan, tilt, and zoom, Dr. Rockhill said. “It was nice to really be able to see the parents and caregivers well,” she added. Children received medication management, and caregivers were trained on managing behaviors of ADHD.

The control arm received a single telepsychiatry session and follow-up care by primary care providers. Parents in both groups used the Vanderbilt Assessment Scale to rate children’s behavior throughout the study, Dr. Rockhill said.