User login

Supreme Court to hear ACA subsidy challenge

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to review a case challenging the legality of federal subsidies provided under the Affordable Care Act.

The Court issued the order Nov. 7, granting the plaintiffs in King v. Burwell a review of the case. The plaintiffs assert that under the ACA, only state marketplaces can issue subsidies to eligible patients.

In July, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the plaintiffs, upholding the government’s ability to provide subsidies to eligible patients who purchase insurance through the 36 federally facilitated health care marketplaces.

On the same day, a limited panel of judges on the District of Columbia Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the federal marketplace subsidies were not legal in a similar challenge, Halbig v. Burwell.

The government appealed, seeking a full review, which was granted in September. All 17 D.C. Circuit judges will review the case on Dec. 17.

The Supreme Court is not likely to hear King v. Burwell before that date.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to review a case challenging the legality of federal subsidies provided under the Affordable Care Act.

The Court issued the order Nov. 7, granting the plaintiffs in King v. Burwell a review of the case. The plaintiffs assert that under the ACA, only state marketplaces can issue subsidies to eligible patients.

In July, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the plaintiffs, upholding the government’s ability to provide subsidies to eligible patients who purchase insurance through the 36 federally facilitated health care marketplaces.

On the same day, a limited panel of judges on the District of Columbia Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the federal marketplace subsidies were not legal in a similar challenge, Halbig v. Burwell.

The government appealed, seeking a full review, which was granted in September. All 17 D.C. Circuit judges will review the case on Dec. 17.

The Supreme Court is not likely to hear King v. Burwell before that date.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to review a case challenging the legality of federal subsidies provided under the Affordable Care Act.

The Court issued the order Nov. 7, granting the plaintiffs in King v. Burwell a review of the case. The plaintiffs assert that under the ACA, only state marketplaces can issue subsidies to eligible patients.

In July, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the plaintiffs, upholding the government’s ability to provide subsidies to eligible patients who purchase insurance through the 36 federally facilitated health care marketplaces.

On the same day, a limited panel of judges on the District of Columbia Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the federal marketplace subsidies were not legal in a similar challenge, Halbig v. Burwell.

The government appealed, seeking a full review, which was granted in September. All 17 D.C. Circuit judges will review the case on Dec. 17.

The Supreme Court is not likely to hear King v. Burwell before that date.

On Twitter @aliciaault

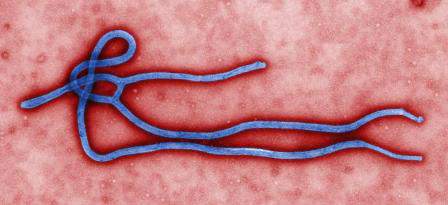

Obama seeks emergency funding for Ebola response

President Obama has asked Congress for $6.1 billion in emergency funding to combat Ebola in West Africa and the United States.

The request comes as the World Health Organization reports that through Nov. 2, there have been a total of 13,042 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases of Ebola in eight countries (Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Spain and the U.S.), and 4,818 deaths.

Although the epidemic appears to be slowing in the initially affected areas of Liberia and Sierra Leone, new cases are popping up in new regions of those countries, Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell said during a press conference.

The emergency funding request reflects the importance of getting to those regions quickly, Ms. Burwell said. “We have to put in place the stopping of it right now, this minute.”

The administration is optimistic that Congress will grant the request, White House Office of Management and Budget Director Shaun Donovan said during the press conference. “We’ve heard a real interest in moving this, and moving it quickly.”

Specifically, the White House is seeking $4.6 billion immediately and $1.5 billion in a contingency fund that could be spent on an as-needed basis.

Included in that request is about $69 million to establish an Ebola Virus Disease Treatment Facility in each state plus Washington, New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Puerto Rico. These facilities would serve as the transfer location for Ebola patients. The funds also would be used to purchase personal protective equipment (PPE), train health care workers, retrofit facilities for enhanced isolation, and create point-of-care labs in isolation areas.

The administration is also seeking $85 million to help support overall health system preparedness. The funds would be used by hospitals to buy PPE; provide training and fit-testing for hospitals, emergency medical services and ambulatory care providers; and to run drills. The money would be funneled through the federal Hospital Preparedness Program managed by 62 state and territorial departments of public health.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would get about $1.8 billion of the request, the National Institutes of Health would get $230 million, and the Food and Drug Administration would get $25 million, Ms. Burwell said. Some of the CDC money would go to helping contain the epidemic in West Africa.

In the U.S., the funds for those HHS agencies would be used to help with preparedness, infection control, contact tracing, monitoring, and to developing diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics, she added.

Some $2 billion of the $6.1 billion overall would go to the U.S. Agency for International Development and to the State Department to help contain Ebola in West Africa.

The contingency fund would be available for any number of potential needs, Mr. Donovan said. With rapidly changing conditions, “it’s necessary to have maximum flexibility to respond quickly.”

The U.S. response is currently funded in part by the continuing resolution that is keeping the government in operation in absence of an approved federal budget. But that money runs out on Dec. 11, unless Congress acts, Mr. Donovan said. He cautioned that if that funding expires and there is no new continuing resolution or action on the emergency request, the federal government might not have any money to fight Ebola.

The request will first go through the House and Senate appropriations committees. Senate Appropriations Chairman Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.) plans to hold a hearing on the U.S. response to Ebola and the White House request on Nov. 12.

“I commend the President for acting to address this crisis at home and abroad,” Sen. Mikulski said in a statement.

On Twitter @aliciaault

President Obama has asked Congress for $6.1 billion in emergency funding to combat Ebola in West Africa and the United States.

The request comes as the World Health Organization reports that through Nov. 2, there have been a total of 13,042 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases of Ebola in eight countries (Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Spain and the U.S.), and 4,818 deaths.

Although the epidemic appears to be slowing in the initially affected areas of Liberia and Sierra Leone, new cases are popping up in new regions of those countries, Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell said during a press conference.

The emergency funding request reflects the importance of getting to those regions quickly, Ms. Burwell said. “We have to put in place the stopping of it right now, this minute.”

The administration is optimistic that Congress will grant the request, White House Office of Management and Budget Director Shaun Donovan said during the press conference. “We’ve heard a real interest in moving this, and moving it quickly.”

Specifically, the White House is seeking $4.6 billion immediately and $1.5 billion in a contingency fund that could be spent on an as-needed basis.

Included in that request is about $69 million to establish an Ebola Virus Disease Treatment Facility in each state plus Washington, New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Puerto Rico. These facilities would serve as the transfer location for Ebola patients. The funds also would be used to purchase personal protective equipment (PPE), train health care workers, retrofit facilities for enhanced isolation, and create point-of-care labs in isolation areas.

The administration is also seeking $85 million to help support overall health system preparedness. The funds would be used by hospitals to buy PPE; provide training and fit-testing for hospitals, emergency medical services and ambulatory care providers; and to run drills. The money would be funneled through the federal Hospital Preparedness Program managed by 62 state and territorial departments of public health.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would get about $1.8 billion of the request, the National Institutes of Health would get $230 million, and the Food and Drug Administration would get $25 million, Ms. Burwell said. Some of the CDC money would go to helping contain the epidemic in West Africa.

In the U.S., the funds for those HHS agencies would be used to help with preparedness, infection control, contact tracing, monitoring, and to developing diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics, she added.

Some $2 billion of the $6.1 billion overall would go to the U.S. Agency for International Development and to the State Department to help contain Ebola in West Africa.

The contingency fund would be available for any number of potential needs, Mr. Donovan said. With rapidly changing conditions, “it’s necessary to have maximum flexibility to respond quickly.”

The U.S. response is currently funded in part by the continuing resolution that is keeping the government in operation in absence of an approved federal budget. But that money runs out on Dec. 11, unless Congress acts, Mr. Donovan said. He cautioned that if that funding expires and there is no new continuing resolution or action on the emergency request, the federal government might not have any money to fight Ebola.

The request will first go through the House and Senate appropriations committees. Senate Appropriations Chairman Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.) plans to hold a hearing on the U.S. response to Ebola and the White House request on Nov. 12.

“I commend the President for acting to address this crisis at home and abroad,” Sen. Mikulski said in a statement.

On Twitter @aliciaault

President Obama has asked Congress for $6.1 billion in emergency funding to combat Ebola in West Africa and the United States.

The request comes as the World Health Organization reports that through Nov. 2, there have been a total of 13,042 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases of Ebola in eight countries (Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Spain and the U.S.), and 4,818 deaths.

Although the epidemic appears to be slowing in the initially affected areas of Liberia and Sierra Leone, new cases are popping up in new regions of those countries, Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell said during a press conference.

The emergency funding request reflects the importance of getting to those regions quickly, Ms. Burwell said. “We have to put in place the stopping of it right now, this minute.”

The administration is optimistic that Congress will grant the request, White House Office of Management and Budget Director Shaun Donovan said during the press conference. “We’ve heard a real interest in moving this, and moving it quickly.”

Specifically, the White House is seeking $4.6 billion immediately and $1.5 billion in a contingency fund that could be spent on an as-needed basis.

Included in that request is about $69 million to establish an Ebola Virus Disease Treatment Facility in each state plus Washington, New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Puerto Rico. These facilities would serve as the transfer location for Ebola patients. The funds also would be used to purchase personal protective equipment (PPE), train health care workers, retrofit facilities for enhanced isolation, and create point-of-care labs in isolation areas.

The administration is also seeking $85 million to help support overall health system preparedness. The funds would be used by hospitals to buy PPE; provide training and fit-testing for hospitals, emergency medical services and ambulatory care providers; and to run drills. The money would be funneled through the federal Hospital Preparedness Program managed by 62 state and territorial departments of public health.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would get about $1.8 billion of the request, the National Institutes of Health would get $230 million, and the Food and Drug Administration would get $25 million, Ms. Burwell said. Some of the CDC money would go to helping contain the epidemic in West Africa.

In the U.S., the funds for those HHS agencies would be used to help with preparedness, infection control, contact tracing, monitoring, and to developing diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics, she added.

Some $2 billion of the $6.1 billion overall would go to the U.S. Agency for International Development and to the State Department to help contain Ebola in West Africa.

The contingency fund would be available for any number of potential needs, Mr. Donovan said. With rapidly changing conditions, “it’s necessary to have maximum flexibility to respond quickly.”

The U.S. response is currently funded in part by the continuing resolution that is keeping the government in operation in absence of an approved federal budget. But that money runs out on Dec. 11, unless Congress acts, Mr. Donovan said. He cautioned that if that funding expires and there is no new continuing resolution or action on the emergency request, the federal government might not have any money to fight Ebola.

The request will first go through the House and Senate appropriations committees. Senate Appropriations Chairman Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.) plans to hold a hearing on the U.S. response to Ebola and the White House request on Nov. 12.

“I commend the President for acting to address this crisis at home and abroad,” Sen. Mikulski said in a statement.

On Twitter @aliciaault

ACC project seeks to reduce heart failure, MI readmissions

A program that’s designed to help hospitals reduce readmissions after inpatient treatment for a heart attack or heart failure is being launched in 35 selected hospitals.

The Patient Navigator Program is sponsored by the American College of Cardiology and AstraZeneca, which provided $10 million in funding for the 2-year pilot program, but was not involved in selection of facilities or any other aspect.

It’s “a unique collaboration between the cardiovascular care team, patients, and families to manage the stress of hospitalization for complex conditions in a way that allows patients to return home, remain healthy, and avoid the need for readmission whenever possible,” said ACC President Patrick T. O’Gara, in a statement.

Hospitals have been under pressure to reduce readmissions since the fall of 2012. That’s when Medicare began penalizing facilities up to 1% of their inpatient admissions for excess readmissions within 30 days of patients with acute myocardial infarctions, heart failure, and pneumonia. The penalty increased to 2% in fiscal year 2014, and went up to 3% in the fiscal year that started Oct. 1. For this year, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip/knee arthroplasty were added to the list of conditions being monitored for readmissions.

The penalties have already been assessed for fiscal year 2015.

Medicare’s Readmissions Reduction Program bases penalties on a prior 3-year period. Fiscal 2015 penalties were based on readmissions from 2010 to 2013.

The Medicare penalties were the driving force behind the creation of the program a few years ago, said Dr. Mary Norine Walsh, chair of the ACC’s Care Transition Oversight Program. But it also represented a chance “to pursue excellence,” said Dr. Walsh in an interview.

The 35 hospitals that are participating were selected by ACC senior staff and cardiologists like Dr. Walsh who are involved in the ACC’s quality improvement efforts. To be eligible, they had to be participants in the ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry ACTION Registry–GWTG, which, according to the ACC, “is a risk-adjusted, outcomes-based quality improvement program that focuses exclusively on high-risk STEMI/NSTEMI myocardial infarction patients.” The registry helps hospitals apply ACC and American Heart Association clinical guideline recommendations and provides quality improvement tools.

They also had to be part of the ACC’s Hospital to Home Initiative, which helps hospitals and cardiovascular care providers improve transitions from hospital to homes.

All 35 hospitals are eligible to receive $80,000 a year for 2 years. Most likely, the facilities will use that money to hire an individual or individuals who can act as a navigator for heart failure and MI patients, said Dr. Walsh, who is the medical director of the heart failure and cardiac transplant program at St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, Ind.

While there are few randomized, controlled trials that examine what works to reduce readmission rates, there are several interventions that have been shown to help, she said. Patient eduction and getting patients in for follow-up care within 7 days are two key components that can make a difference, said Dr. Walsh. Multidisciplinary heart failure programs also have an impact.

The participating hospitals will share their processes and models, and at the end of the 2 years, the hope is that the facilities will continue to fund the program, said Dr. Walsh.

The ACC will also “be interested to find out what success looks like,” she said.

The Patient Navigator Program probably won’t help hospitals avoid penalties until fiscal year 2017 at the earliest, Dr. Walsh noted. However, the model will still be important, she said.

“We know that value-based purchasing is moving on, and the penalties will almost certainly extend to other diagnoses each sequential year, so hospitals are interested in preparing for the future,” said Dr. Walsh.

On Twitter @aliciaault

A program that’s designed to help hospitals reduce readmissions after inpatient treatment for a heart attack or heart failure is being launched in 35 selected hospitals.

The Patient Navigator Program is sponsored by the American College of Cardiology and AstraZeneca, which provided $10 million in funding for the 2-year pilot program, but was not involved in selection of facilities or any other aspect.

It’s “a unique collaboration between the cardiovascular care team, patients, and families to manage the stress of hospitalization for complex conditions in a way that allows patients to return home, remain healthy, and avoid the need for readmission whenever possible,” said ACC President Patrick T. O’Gara, in a statement.

Hospitals have been under pressure to reduce readmissions since the fall of 2012. That’s when Medicare began penalizing facilities up to 1% of their inpatient admissions for excess readmissions within 30 days of patients with acute myocardial infarctions, heart failure, and pneumonia. The penalty increased to 2% in fiscal year 2014, and went up to 3% in the fiscal year that started Oct. 1. For this year, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip/knee arthroplasty were added to the list of conditions being monitored for readmissions.

The penalties have already been assessed for fiscal year 2015.

Medicare’s Readmissions Reduction Program bases penalties on a prior 3-year period. Fiscal 2015 penalties were based on readmissions from 2010 to 2013.

The Medicare penalties were the driving force behind the creation of the program a few years ago, said Dr. Mary Norine Walsh, chair of the ACC’s Care Transition Oversight Program. But it also represented a chance “to pursue excellence,” said Dr. Walsh in an interview.

The 35 hospitals that are participating were selected by ACC senior staff and cardiologists like Dr. Walsh who are involved in the ACC’s quality improvement efforts. To be eligible, they had to be participants in the ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry ACTION Registry–GWTG, which, according to the ACC, “is a risk-adjusted, outcomes-based quality improvement program that focuses exclusively on high-risk STEMI/NSTEMI myocardial infarction patients.” The registry helps hospitals apply ACC and American Heart Association clinical guideline recommendations and provides quality improvement tools.

They also had to be part of the ACC’s Hospital to Home Initiative, which helps hospitals and cardiovascular care providers improve transitions from hospital to homes.

All 35 hospitals are eligible to receive $80,000 a year for 2 years. Most likely, the facilities will use that money to hire an individual or individuals who can act as a navigator for heart failure and MI patients, said Dr. Walsh, who is the medical director of the heart failure and cardiac transplant program at St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, Ind.

While there are few randomized, controlled trials that examine what works to reduce readmission rates, there are several interventions that have been shown to help, she said. Patient eduction and getting patients in for follow-up care within 7 days are two key components that can make a difference, said Dr. Walsh. Multidisciplinary heart failure programs also have an impact.

The participating hospitals will share their processes and models, and at the end of the 2 years, the hope is that the facilities will continue to fund the program, said Dr. Walsh.

The ACC will also “be interested to find out what success looks like,” she said.

The Patient Navigator Program probably won’t help hospitals avoid penalties until fiscal year 2017 at the earliest, Dr. Walsh noted. However, the model will still be important, she said.

“We know that value-based purchasing is moving on, and the penalties will almost certainly extend to other diagnoses each sequential year, so hospitals are interested in preparing for the future,” said Dr. Walsh.

On Twitter @aliciaault

A program that’s designed to help hospitals reduce readmissions after inpatient treatment for a heart attack or heart failure is being launched in 35 selected hospitals.

The Patient Navigator Program is sponsored by the American College of Cardiology and AstraZeneca, which provided $10 million in funding for the 2-year pilot program, but was not involved in selection of facilities or any other aspect.

It’s “a unique collaboration between the cardiovascular care team, patients, and families to manage the stress of hospitalization for complex conditions in a way that allows patients to return home, remain healthy, and avoid the need for readmission whenever possible,” said ACC President Patrick T. O’Gara, in a statement.

Hospitals have been under pressure to reduce readmissions since the fall of 2012. That’s when Medicare began penalizing facilities up to 1% of their inpatient admissions for excess readmissions within 30 days of patients with acute myocardial infarctions, heart failure, and pneumonia. The penalty increased to 2% in fiscal year 2014, and went up to 3% in the fiscal year that started Oct. 1. For this year, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip/knee arthroplasty were added to the list of conditions being monitored for readmissions.

The penalties have already been assessed for fiscal year 2015.

Medicare’s Readmissions Reduction Program bases penalties on a prior 3-year period. Fiscal 2015 penalties were based on readmissions from 2010 to 2013.

The Medicare penalties were the driving force behind the creation of the program a few years ago, said Dr. Mary Norine Walsh, chair of the ACC’s Care Transition Oversight Program. But it also represented a chance “to pursue excellence,” said Dr. Walsh in an interview.

The 35 hospitals that are participating were selected by ACC senior staff and cardiologists like Dr. Walsh who are involved in the ACC’s quality improvement efforts. To be eligible, they had to be participants in the ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry ACTION Registry–GWTG, which, according to the ACC, “is a risk-adjusted, outcomes-based quality improvement program that focuses exclusively on high-risk STEMI/NSTEMI myocardial infarction patients.” The registry helps hospitals apply ACC and American Heart Association clinical guideline recommendations and provides quality improvement tools.

They also had to be part of the ACC’s Hospital to Home Initiative, which helps hospitals and cardiovascular care providers improve transitions from hospital to homes.

All 35 hospitals are eligible to receive $80,000 a year for 2 years. Most likely, the facilities will use that money to hire an individual or individuals who can act as a navigator for heart failure and MI patients, said Dr. Walsh, who is the medical director of the heart failure and cardiac transplant program at St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, Ind.

While there are few randomized, controlled trials that examine what works to reduce readmission rates, there are several interventions that have been shown to help, she said. Patient eduction and getting patients in for follow-up care within 7 days are two key components that can make a difference, said Dr. Walsh. Multidisciplinary heart failure programs also have an impact.

The participating hospitals will share their processes and models, and at the end of the 2 years, the hope is that the facilities will continue to fund the program, said Dr. Walsh.

The ACC will also “be interested to find out what success looks like,” she said.

The Patient Navigator Program probably won’t help hospitals avoid penalties until fiscal year 2017 at the earliest, Dr. Walsh noted. However, the model will still be important, she said.

“We know that value-based purchasing is moving on, and the penalties will almost certainly extend to other diagnoses each sequential year, so hospitals are interested in preparing for the future,” said Dr. Walsh.

On Twitter @aliciaault

House panel faults CDC’s Ebola response

WASHINGTON – Both Republicans and Democrats on the House Oversight and Government Reform committee said they believed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had not been acting quickly or consistently enough to protect health care workers and Americans from the Ebola virus.

Committee Chairman Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) said he felt that the agency had made recommendations on protective equipment that turned out to be ill advised. He also suggested that CDC Director Thomas Frieden had misled the American public about the potential for transmission.

“We have the head of CDC – he’s supposed to be the expert – and he’s made statements that simply aren’t true,” Rep. Issa said at the hearing, adding that the two nurses who were infected at a Dallas hospital had been wearing protective gear recommended by the CDC. “We’re relying on protocols from somebody who has proven not to be correct,” he said.

He asked whether Congress should view the federal government’s Ebola response as not just a singular mistake, but potentially a failure in preparedness for any infectious disease epidemic.

“Our failures largely relate to the fact that we’re learning some new things about Ebola,” said Dr. Nicole Lurie, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. “Ebola has never been in this hemisphere before, and as we’re learning those things we’re tightening up our policies and procedures as quickly as possible,” said Dr. Lurie.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-Va.) said that he, too, wanted answers, noting that “while CDC was giving us assurances about how hard it was to contract the disease,” two nurses were infected. “Do you think perhaps, not intentionally of course, in a zeal to assure the public, CDC misstepped?” he asked.

“I think that CDC has said that some missteps have been made,” said Dr. Lurie.

She labeled the response effort “a work in progress,” adding, “we are taking constant steps to adjust.”

Meanwhile, National Nurses United told the committee that it is asking President Obama to order hospitals to adopt a mandatory uniform of protective clothing and gear to help prevent any further contamination of health care workers.

Deborah Burger, copresident of the nurses’ group, told the panel that hospitals are still unprepared to treat any potential Ebola patients. She cited a survey by the group that found that 85% of responding registered nurses said they had not been adequately trained. Almost 70% said their facility had not communicated any policy regarding the potential admission of an Ebola patient.

“Every [registered nurse] who works in a hospital or healthcare facility could be Nina Pham or Amber Vinson, both of whom contracted Ebola while treating Thomas Eric Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas,” said Ms. Burger.

She noted that even though the CDC had recently updated its guidelines on what health care workers should wear when treating Ebola patients, those guidelines are “just guidelines.”

Ms. Burger added, “all 5,000 hospitals in the U.S.A. get to pick and choose what part of the guidelines they want to implement,” which is why her group was seeking a mandate for protective clothing and gear.

WASHINGTON – Both Republicans and Democrats on the House Oversight and Government Reform committee said they believed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had not been acting quickly or consistently enough to protect health care workers and Americans from the Ebola virus.

Committee Chairman Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) said he felt that the agency had made recommendations on protective equipment that turned out to be ill advised. He also suggested that CDC Director Thomas Frieden had misled the American public about the potential for transmission.

“We have the head of CDC – he’s supposed to be the expert – and he’s made statements that simply aren’t true,” Rep. Issa said at the hearing, adding that the two nurses who were infected at a Dallas hospital had been wearing protective gear recommended by the CDC. “We’re relying on protocols from somebody who has proven not to be correct,” he said.

He asked whether Congress should view the federal government’s Ebola response as not just a singular mistake, but potentially a failure in preparedness for any infectious disease epidemic.

“Our failures largely relate to the fact that we’re learning some new things about Ebola,” said Dr. Nicole Lurie, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. “Ebola has never been in this hemisphere before, and as we’re learning those things we’re tightening up our policies and procedures as quickly as possible,” said Dr. Lurie.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-Va.) said that he, too, wanted answers, noting that “while CDC was giving us assurances about how hard it was to contract the disease,” two nurses were infected. “Do you think perhaps, not intentionally of course, in a zeal to assure the public, CDC misstepped?” he asked.

“I think that CDC has said that some missteps have been made,” said Dr. Lurie.

She labeled the response effort “a work in progress,” adding, “we are taking constant steps to adjust.”

Meanwhile, National Nurses United told the committee that it is asking President Obama to order hospitals to adopt a mandatory uniform of protective clothing and gear to help prevent any further contamination of health care workers.

Deborah Burger, copresident of the nurses’ group, told the panel that hospitals are still unprepared to treat any potential Ebola patients. She cited a survey by the group that found that 85% of responding registered nurses said they had not been adequately trained. Almost 70% said their facility had not communicated any policy regarding the potential admission of an Ebola patient.

“Every [registered nurse] who works in a hospital or healthcare facility could be Nina Pham or Amber Vinson, both of whom contracted Ebola while treating Thomas Eric Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas,” said Ms. Burger.

She noted that even though the CDC had recently updated its guidelines on what health care workers should wear when treating Ebola patients, those guidelines are “just guidelines.”

Ms. Burger added, “all 5,000 hospitals in the U.S.A. get to pick and choose what part of the guidelines they want to implement,” which is why her group was seeking a mandate for protective clothing and gear.

WASHINGTON – Both Republicans and Democrats on the House Oversight and Government Reform committee said they believed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had not been acting quickly or consistently enough to protect health care workers and Americans from the Ebola virus.

Committee Chairman Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) said he felt that the agency had made recommendations on protective equipment that turned out to be ill advised. He also suggested that CDC Director Thomas Frieden had misled the American public about the potential for transmission.

“We have the head of CDC – he’s supposed to be the expert – and he’s made statements that simply aren’t true,” Rep. Issa said at the hearing, adding that the two nurses who were infected at a Dallas hospital had been wearing protective gear recommended by the CDC. “We’re relying on protocols from somebody who has proven not to be correct,” he said.

He asked whether Congress should view the federal government’s Ebola response as not just a singular mistake, but potentially a failure in preparedness for any infectious disease epidemic.

“Our failures largely relate to the fact that we’re learning some new things about Ebola,” said Dr. Nicole Lurie, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. “Ebola has never been in this hemisphere before, and as we’re learning those things we’re tightening up our policies and procedures as quickly as possible,” said Dr. Lurie.

Rep. Gerald Connolly (D-Va.) said that he, too, wanted answers, noting that “while CDC was giving us assurances about how hard it was to contract the disease,” two nurses were infected. “Do you think perhaps, not intentionally of course, in a zeal to assure the public, CDC misstepped?” he asked.

“I think that CDC has said that some missteps have been made,” said Dr. Lurie.

She labeled the response effort “a work in progress,” adding, “we are taking constant steps to adjust.”

Meanwhile, National Nurses United told the committee that it is asking President Obama to order hospitals to adopt a mandatory uniform of protective clothing and gear to help prevent any further contamination of health care workers.

Deborah Burger, copresident of the nurses’ group, told the panel that hospitals are still unprepared to treat any potential Ebola patients. She cited a survey by the group that found that 85% of responding registered nurses said they had not been adequately trained. Almost 70% said their facility had not communicated any policy regarding the potential admission of an Ebola patient.

“Every [registered nurse] who works in a hospital or healthcare facility could be Nina Pham or Amber Vinson, both of whom contracted Ebola while treating Thomas Eric Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas,” said Ms. Burger.

She noted that even though the CDC had recently updated its guidelines on what health care workers should wear when treating Ebola patients, those guidelines are “just guidelines.”

Ms. Burger added, “all 5,000 hospitals in the U.S.A. get to pick and choose what part of the guidelines they want to implement,” which is why her group was seeking a mandate for protective clothing and gear.

AT THE HOUSE OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE

AAFP launches campaign to boost primary care

WASHINGTON– The American Academy of Family Physicians is launching a 5-year strategic effort to help convince payers and policy makers to place a higher value on primary care and that getting back to basics is the way to achieve better health, better care, and lower costs.

Family physicians are best-positioned to deliver on that promise, known as the Triple Aim, said Dr. Glen Stream, in announcing the new campaign at the AAFP Scientific Assembly Oct. 23.

“We believe the solution to many – if not all – of our health care problems can be found in primary care,” said Dr. Stream, a past board chairman of AAFP, in a statement.

Dr. Stream is the chairman of the board of directors of Family Medicine for America’s Health, an organization that will tackle the work of “modernizing the family medicine specialty.” The group will focus on expanding access to the patient-centered medical home, building up the primary care workforce, and shifting from fee for service to a more comprehensive primary care payment model, Dr. Stream said.

One issue the campaign will work on: Advocating for the creation of primary care–specific evaluation and management codes.

“If you had a primary care code that was specifically designed to recognize the intensity and complexity of modern primary care practice and valued it accordingly, then you could change payment for primary care services,” said Dr. Stream, in an interview.

The campaign won’t focus only on physician income, but on “how do you have adequate payment into a medical home system that covers all of the services that patients need and deserve?”

The campaign will also focus on technology. There will be efforts to speak with one voice about improving electronic medical records systems. But the technology work group – one of six on the campaign – will more specifically look at ensuring that new inventions, whether they be at the bedside or on a smartphone – are effective in actually connecting physicians and patients and improve health outcomes.

As part of the overall strategic initiative, the AAFP is also launching “Health is Primary,” a public outreach project that will, among other things, visit a number of cities to showcase primary care interventions that are meeting the Triple Aim.

The cities have not been chosen yet, but the tour will begin in January, said Dr. Stream.

Dr. Don Berwick, who has been a chief promoter of the Triple Aim through the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and when he was administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, applauded the AAFP campaign.

“Bravo to family medicine for taking leadership here,” said Dr. Berwick at the briefing. “You’ll have me rooting for you from now on,” he said.

In a plenary address to the AAFP Scientific Assembly, Sylvia Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services said, “When it comes to improving the way providers are paid, I want you to know that we share your commitment to rewarding value and care coordination, rather than volume and care duplication. Like you, we want to pay providers for what works – whether it’s something as complex as preventing or treating disease or something as straightforward as making sure that you have time to answer a patient’s questions.”

Although most of the campaign’s goals are aligned with those of the AAFP, its efforts are more urgent and more inclusive, Dr. Stream said. The campaign’s board includes representatives from the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, the American Board of Family Medicine, the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors, the North American Primary Care Research Group, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Other board members include a rural physician, a new physician, an association executive, and a representative from the National Partnership for Women and Families.

WASHINGTON– The American Academy of Family Physicians is launching a 5-year strategic effort to help convince payers and policy makers to place a higher value on primary care and that getting back to basics is the way to achieve better health, better care, and lower costs.

Family physicians are best-positioned to deliver on that promise, known as the Triple Aim, said Dr. Glen Stream, in announcing the new campaign at the AAFP Scientific Assembly Oct. 23.

“We believe the solution to many – if not all – of our health care problems can be found in primary care,” said Dr. Stream, a past board chairman of AAFP, in a statement.

Dr. Stream is the chairman of the board of directors of Family Medicine for America’s Health, an organization that will tackle the work of “modernizing the family medicine specialty.” The group will focus on expanding access to the patient-centered medical home, building up the primary care workforce, and shifting from fee for service to a more comprehensive primary care payment model, Dr. Stream said.

One issue the campaign will work on: Advocating for the creation of primary care–specific evaluation and management codes.

“If you had a primary care code that was specifically designed to recognize the intensity and complexity of modern primary care practice and valued it accordingly, then you could change payment for primary care services,” said Dr. Stream, in an interview.

The campaign won’t focus only on physician income, but on “how do you have adequate payment into a medical home system that covers all of the services that patients need and deserve?”

The campaign will also focus on technology. There will be efforts to speak with one voice about improving electronic medical records systems. But the technology work group – one of six on the campaign – will more specifically look at ensuring that new inventions, whether they be at the bedside or on a smartphone – are effective in actually connecting physicians and patients and improve health outcomes.

As part of the overall strategic initiative, the AAFP is also launching “Health is Primary,” a public outreach project that will, among other things, visit a number of cities to showcase primary care interventions that are meeting the Triple Aim.

The cities have not been chosen yet, but the tour will begin in January, said Dr. Stream.

Dr. Don Berwick, who has been a chief promoter of the Triple Aim through the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and when he was administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, applauded the AAFP campaign.

“Bravo to family medicine for taking leadership here,” said Dr. Berwick at the briefing. “You’ll have me rooting for you from now on,” he said.

In a plenary address to the AAFP Scientific Assembly, Sylvia Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services said, “When it comes to improving the way providers are paid, I want you to know that we share your commitment to rewarding value and care coordination, rather than volume and care duplication. Like you, we want to pay providers for what works – whether it’s something as complex as preventing or treating disease or something as straightforward as making sure that you have time to answer a patient’s questions.”

Although most of the campaign’s goals are aligned with those of the AAFP, its efforts are more urgent and more inclusive, Dr. Stream said. The campaign’s board includes representatives from the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, the American Board of Family Medicine, the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors, the North American Primary Care Research Group, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Other board members include a rural physician, a new physician, an association executive, and a representative from the National Partnership for Women and Families.

WASHINGTON– The American Academy of Family Physicians is launching a 5-year strategic effort to help convince payers and policy makers to place a higher value on primary care and that getting back to basics is the way to achieve better health, better care, and lower costs.

Family physicians are best-positioned to deliver on that promise, known as the Triple Aim, said Dr. Glen Stream, in announcing the new campaign at the AAFP Scientific Assembly Oct. 23.

“We believe the solution to many – if not all – of our health care problems can be found in primary care,” said Dr. Stream, a past board chairman of AAFP, in a statement.

Dr. Stream is the chairman of the board of directors of Family Medicine for America’s Health, an organization that will tackle the work of “modernizing the family medicine specialty.” The group will focus on expanding access to the patient-centered medical home, building up the primary care workforce, and shifting from fee for service to a more comprehensive primary care payment model, Dr. Stream said.

One issue the campaign will work on: Advocating for the creation of primary care–specific evaluation and management codes.

“If you had a primary care code that was specifically designed to recognize the intensity and complexity of modern primary care practice and valued it accordingly, then you could change payment for primary care services,” said Dr. Stream, in an interview.

The campaign won’t focus only on physician income, but on “how do you have adequate payment into a medical home system that covers all of the services that patients need and deserve?”

The campaign will also focus on technology. There will be efforts to speak with one voice about improving electronic medical records systems. But the technology work group – one of six on the campaign – will more specifically look at ensuring that new inventions, whether they be at the bedside or on a smartphone – are effective in actually connecting physicians and patients and improve health outcomes.

As part of the overall strategic initiative, the AAFP is also launching “Health is Primary,” a public outreach project that will, among other things, visit a number of cities to showcase primary care interventions that are meeting the Triple Aim.

The cities have not been chosen yet, but the tour will begin in January, said Dr. Stream.

Dr. Don Berwick, who has been a chief promoter of the Triple Aim through the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and when he was administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, applauded the AAFP campaign.

“Bravo to family medicine for taking leadership here,” said Dr. Berwick at the briefing. “You’ll have me rooting for you from now on,” he said.

In a plenary address to the AAFP Scientific Assembly, Sylvia Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services said, “When it comes to improving the way providers are paid, I want you to know that we share your commitment to rewarding value and care coordination, rather than volume and care duplication. Like you, we want to pay providers for what works – whether it’s something as complex as preventing or treating disease or something as straightforward as making sure that you have time to answer a patient’s questions.”

Although most of the campaign’s goals are aligned with those of the AAFP, its efforts are more urgent and more inclusive, Dr. Stream said. The campaign’s board includes representatives from the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, the American Board of Family Medicine, the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors, the North American Primary Care Research Group, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Other board members include a rural physician, a new physician, an association executive, and a representative from the National Partnership for Women and Families.

New AAFP mission: No more Dr. Nice Guy

WASHINGTON – The American Academy of Family Physicians installed a new president and elected four* new board members and a president-elect, as all promised to take family medicine into a new, more focused, and more aggressive era.

The election results were announced Oct. 22 on the eve of the unveiling of a major new AAFP initiative, “Health is Primary,” which will seek to put family physicians at the forefront of the transformation of the health care system.

The details will be publicly released on Oct. 23, but in discussing the campaign with the Congress of Delegates, Dr. Glen R. Stream, a former AAFP president, said, “It is not self-serving to stand up and say the health care system needs solid primary care that’s well compensated to deliver that care in a medical home model.”

That goal “serves our patients and our country,” said Dr. Stream, who is in private practice in La Quinta, Calif. “We have got to get over ‘Family Medicine Nice.’ ”

Dr. Robert L. Wergin, who took over the helm as AAFP president, promised delegates that he would help them manage the challenges of the rapidly changing health care system and asked for their help. “We’ll finish this together and be winners in this health care delivery race,” he said.

Dr. Wergin, an AAFP member since 1982, practices in the town where he was born and raised – Milford, Neb. He’s chairman of the Milford public schools foundation board, and a team physician for the school district, and medical director of the town volunteer fire department. He was named Nebraska family physician of the year in 2002 and the state’s nursing home medical director of the year in 2012.

The new president-elect is Dr. Wanda Filer, a current AAFP board member who practices in York, Pa. She said that the new AAFP direction was “a completely new story.”

It will require the “mobilization of American family medicine,” with everyone coming to the table to explain why they are best positioned to lower costs, and improve access and quality, said Dr. Filer. In the next 3 to 5 years, “the message can be transformational for the American health care system.” New board member Dr. Lynne Lillie, said that she was ready to be a strong advocate for family medicine. “We as family practice physicians are overregulated, undercompensated, overburdened, and undervalued,” said Dr. Lillie, who is in private practice in Red Wing, Minn.

Noting a high level of burnout, a loss of job satisfaction, and declining empathy toward patients, she said,“This is not okay.”

Family physicians “deserve better and our patients deserve better,” said Dr. Lillie.

The Congress of Delegates also elected Dr. John S. Cullen of Valdez, Alaska, and Dr. Mott Blair, of Wallace, N.C., to full 3-year terms as directors. Dr. Cullen is the emergency medical services director for the Alaska Avalanche Information Center. Dr. Blair used to accompany his father, a family physician, on house calls, often into very rural areas. There, he learned “don’t step on a stick that moves,” he said.

The path ahead for family medicine is tricky – and may have sticks that move – but he said he was prepared to take on the challenges.

Dr. Carl Olden of Yakima, Wash., was the final new board member, and will serve the remainder of an expiring 1-year term and then be eligible to run again in 2015. Dr. Olden was born and raised in Toppenish, Wash., on the Yakima Indian Reservation.

After his residency, he went back to the reservation and practiced with the Indian Health Services from 1984 to 1995.

On Twitter @aliciaault

*Correction, 10/24/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of new AAFP board members elected.

WASHINGTON – The American Academy of Family Physicians installed a new president and elected four* new board members and a president-elect, as all promised to take family medicine into a new, more focused, and more aggressive era.

The election results were announced Oct. 22 on the eve of the unveiling of a major new AAFP initiative, “Health is Primary,” which will seek to put family physicians at the forefront of the transformation of the health care system.

The details will be publicly released on Oct. 23, but in discussing the campaign with the Congress of Delegates, Dr. Glen R. Stream, a former AAFP president, said, “It is not self-serving to stand up and say the health care system needs solid primary care that’s well compensated to deliver that care in a medical home model.”

That goal “serves our patients and our country,” said Dr. Stream, who is in private practice in La Quinta, Calif. “We have got to get over ‘Family Medicine Nice.’ ”

Dr. Robert L. Wergin, who took over the helm as AAFP president, promised delegates that he would help them manage the challenges of the rapidly changing health care system and asked for their help. “We’ll finish this together and be winners in this health care delivery race,” he said.

Dr. Wergin, an AAFP member since 1982, practices in the town where he was born and raised – Milford, Neb. He’s chairman of the Milford public schools foundation board, and a team physician for the school district, and medical director of the town volunteer fire department. He was named Nebraska family physician of the year in 2002 and the state’s nursing home medical director of the year in 2012.

The new president-elect is Dr. Wanda Filer, a current AAFP board member who practices in York, Pa. She said that the new AAFP direction was “a completely new story.”

It will require the “mobilization of American family medicine,” with everyone coming to the table to explain why they are best positioned to lower costs, and improve access and quality, said Dr. Filer. In the next 3 to 5 years, “the message can be transformational for the American health care system.” New board member Dr. Lynne Lillie, said that she was ready to be a strong advocate for family medicine. “We as family practice physicians are overregulated, undercompensated, overburdened, and undervalued,” said Dr. Lillie, who is in private practice in Red Wing, Minn.

Noting a high level of burnout, a loss of job satisfaction, and declining empathy toward patients, she said,“This is not okay.”

Family physicians “deserve better and our patients deserve better,” said Dr. Lillie.

The Congress of Delegates also elected Dr. John S. Cullen of Valdez, Alaska, and Dr. Mott Blair, of Wallace, N.C., to full 3-year terms as directors. Dr. Cullen is the emergency medical services director for the Alaska Avalanche Information Center. Dr. Blair used to accompany his father, a family physician, on house calls, often into very rural areas. There, he learned “don’t step on a stick that moves,” he said.

The path ahead for family medicine is tricky – and may have sticks that move – but he said he was prepared to take on the challenges.

Dr. Carl Olden of Yakima, Wash., was the final new board member, and will serve the remainder of an expiring 1-year term and then be eligible to run again in 2015. Dr. Olden was born and raised in Toppenish, Wash., on the Yakima Indian Reservation.

After his residency, he went back to the reservation and practiced with the Indian Health Services from 1984 to 1995.

On Twitter @aliciaault

*Correction, 10/24/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of new AAFP board members elected.

WASHINGTON – The American Academy of Family Physicians installed a new president and elected four* new board members and a president-elect, as all promised to take family medicine into a new, more focused, and more aggressive era.

The election results were announced Oct. 22 on the eve of the unveiling of a major new AAFP initiative, “Health is Primary,” which will seek to put family physicians at the forefront of the transformation of the health care system.

The details will be publicly released on Oct. 23, but in discussing the campaign with the Congress of Delegates, Dr. Glen R. Stream, a former AAFP president, said, “It is not self-serving to stand up and say the health care system needs solid primary care that’s well compensated to deliver that care in a medical home model.”

That goal “serves our patients and our country,” said Dr. Stream, who is in private practice in La Quinta, Calif. “We have got to get over ‘Family Medicine Nice.’ ”

Dr. Robert L. Wergin, who took over the helm as AAFP president, promised delegates that he would help them manage the challenges of the rapidly changing health care system and asked for their help. “We’ll finish this together and be winners in this health care delivery race,” he said.

Dr. Wergin, an AAFP member since 1982, practices in the town where he was born and raised – Milford, Neb. He’s chairman of the Milford public schools foundation board, and a team physician for the school district, and medical director of the town volunteer fire department. He was named Nebraska family physician of the year in 2002 and the state’s nursing home medical director of the year in 2012.

The new president-elect is Dr. Wanda Filer, a current AAFP board member who practices in York, Pa. She said that the new AAFP direction was “a completely new story.”

It will require the “mobilization of American family medicine,” with everyone coming to the table to explain why they are best positioned to lower costs, and improve access and quality, said Dr. Filer. In the next 3 to 5 years, “the message can be transformational for the American health care system.” New board member Dr. Lynne Lillie, said that she was ready to be a strong advocate for family medicine. “We as family practice physicians are overregulated, undercompensated, overburdened, and undervalued,” said Dr. Lillie, who is in private practice in Red Wing, Minn.

Noting a high level of burnout, a loss of job satisfaction, and declining empathy toward patients, she said,“This is not okay.”

Family physicians “deserve better and our patients deserve better,” said Dr. Lillie.

The Congress of Delegates also elected Dr. John S. Cullen of Valdez, Alaska, and Dr. Mott Blair, of Wallace, N.C., to full 3-year terms as directors. Dr. Cullen is the emergency medical services director for the Alaska Avalanche Information Center. Dr. Blair used to accompany his father, a family physician, on house calls, often into very rural areas. There, he learned “don’t step on a stick that moves,” he said.

The path ahead for family medicine is tricky – and may have sticks that move – but he said he was prepared to take on the challenges.

Dr. Carl Olden of Yakima, Wash., was the final new board member, and will serve the remainder of an expiring 1-year term and then be eligible to run again in 2015. Dr. Olden was born and raised in Toppenish, Wash., on the Yakima Indian Reservation.

After his residency, he went back to the reservation and practiced with the Indian Health Services from 1984 to 1995.

On Twitter @aliciaault

*Correction, 10/24/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of new AAFP board members elected.

AT THE AAFP CONGRESS OF DELEGATES

AAFP delegates want Medicare pay for vaccines, insulin pens

WASHINGTON– Medicare Part B should pay physicians to administer vaccines in their offices, according to resolutions passed at the annual Congress of Delegates of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The AAFP’s policymaking body voted to advocate that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pay physicians under Medicare Part B to administer the shingles vaccine and all other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Payment should be retroactive to when the ACIP first recommends a particular vaccine, according to a resolution introduced by the New York State chapter.

The Mississippi delegation urged the delegates to approve a resolution to have Medicare pay for the cost of insulin pens, as many patients with diabetes and vision issues cannot appropriately use vials and syringes, which are covered by Medicare. The AAFP Congress backed this resolution, also.

A hotly contested resolution called for the AAFP to advocate for a ban on diagnostic testing by pharmacists. An initiative in Michigan is allowing pharmacists to test for conditions like strep and then prescribe appropriate medications. The Michigan chapter urged the Congress to take a strong stand against this expansion of scope-of-practice for pharmacists, saying that it would likely spread to other states.

Many delegates said that pharmacists did not have extensive clinical training and that patient safety could be jeopardized. Others said that they did not want to be viewed as engaging in a turf battle against pharmacists.

Ultimately, the Congress referred the proposal to the AAFP board for study.

The Congress also voted against advocating for a single-payer health care system, and referred to the AAFP board a proposal to rescind the marketing approval of the long-acting opioid Zohydro.

The New York and Rhode Island chapters asked the AAFP to lobby the U.S. Congress to pass a law to treat electronic cigarettes the same as tobacco products, and that the minimum age for purchase be made the same as well. That resolution was accepted by the delegates.

The AAFP Congress also adopted a resolution that urged the federal government to end the mandatory 30-day waiting period between when informed consent is given and when Medicaid will cover a voluntary sterilization procedure. Delegates also backed a proposal to urge coverage of vasectomy and male contraceptive services as a preventive care service – that is, a cost-free service – under the Affordable Care Act.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON– Medicare Part B should pay physicians to administer vaccines in their offices, according to resolutions passed at the annual Congress of Delegates of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The AAFP’s policymaking body voted to advocate that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pay physicians under Medicare Part B to administer the shingles vaccine and all other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Payment should be retroactive to when the ACIP first recommends a particular vaccine, according to a resolution introduced by the New York State chapter.

The Mississippi delegation urged the delegates to approve a resolution to have Medicare pay for the cost of insulin pens, as many patients with diabetes and vision issues cannot appropriately use vials and syringes, which are covered by Medicare. The AAFP Congress backed this resolution, also.

A hotly contested resolution called for the AAFP to advocate for a ban on diagnostic testing by pharmacists. An initiative in Michigan is allowing pharmacists to test for conditions like strep and then prescribe appropriate medications. The Michigan chapter urged the Congress to take a strong stand against this expansion of scope-of-practice for pharmacists, saying that it would likely spread to other states.

Many delegates said that pharmacists did not have extensive clinical training and that patient safety could be jeopardized. Others said that they did not want to be viewed as engaging in a turf battle against pharmacists.

Ultimately, the Congress referred the proposal to the AAFP board for study.

The Congress also voted against advocating for a single-payer health care system, and referred to the AAFP board a proposal to rescind the marketing approval of the long-acting opioid Zohydro.

The New York and Rhode Island chapters asked the AAFP to lobby the U.S. Congress to pass a law to treat electronic cigarettes the same as tobacco products, and that the minimum age for purchase be made the same as well. That resolution was accepted by the delegates.

The AAFP Congress also adopted a resolution that urged the federal government to end the mandatory 30-day waiting period between when informed consent is given and when Medicaid will cover a voluntary sterilization procedure. Delegates also backed a proposal to urge coverage of vasectomy and male contraceptive services as a preventive care service – that is, a cost-free service – under the Affordable Care Act.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON– Medicare Part B should pay physicians to administer vaccines in their offices, according to resolutions passed at the annual Congress of Delegates of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The AAFP’s policymaking body voted to advocate that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pay physicians under Medicare Part B to administer the shingles vaccine and all other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Payment should be retroactive to when the ACIP first recommends a particular vaccine, according to a resolution introduced by the New York State chapter.

The Mississippi delegation urged the delegates to approve a resolution to have Medicare pay for the cost of insulin pens, as many patients with diabetes and vision issues cannot appropriately use vials and syringes, which are covered by Medicare. The AAFP Congress backed this resolution, also.

A hotly contested resolution called for the AAFP to advocate for a ban on diagnostic testing by pharmacists. An initiative in Michigan is allowing pharmacists to test for conditions like strep and then prescribe appropriate medications. The Michigan chapter urged the Congress to take a strong stand against this expansion of scope-of-practice for pharmacists, saying that it would likely spread to other states.

Many delegates said that pharmacists did not have extensive clinical training and that patient safety could be jeopardized. Others said that they did not want to be viewed as engaging in a turf battle against pharmacists.

Ultimately, the Congress referred the proposal to the AAFP board for study.

The Congress also voted against advocating for a single-payer health care system, and referred to the AAFP board a proposal to rescind the marketing approval of the long-acting opioid Zohydro.

The New York and Rhode Island chapters asked the AAFP to lobby the U.S. Congress to pass a law to treat electronic cigarettes the same as tobacco products, and that the minimum age for purchase be made the same as well. That resolution was accepted by the delegates.

The AAFP Congress also adopted a resolution that urged the federal government to end the mandatory 30-day waiting period between when informed consent is given and when Medicaid will cover a voluntary sterilization procedure. Delegates also backed a proposal to urge coverage of vasectomy and male contraceptive services as a preventive care service – that is, a cost-free service – under the Affordable Care Act.

On Twitter @aliciaault

AT THE AAFP CONGRESS OF DELEGATES 2014

Family medicine is ascendant, says AAFP’s Cain

WASHINGTON – Family medicine has gone from the brink of collapse to a rising specialty, American Academy of Family Physicians Board Chair Jeffrey Cain said Oct. 20 in a speech capping his service on the academy leadership team.

Dr. Cain noted that he began his run as an AAFP officer in 2007, a time when the “impending collapse” description had been bestowed upon family medicine by the Institute of Medicine. “For family medicine, it really was a time of crisis,” he said at the annual Congress of Delegates of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Payments were low, there was little student interest in the specialty, and some 47 million Americans were uninsured, he said.

“We’ve actually stopped that free fall of [family medicine] and we are now rising,” said Dr. Cain, who completes his term as board chair at the meeting.

Six years ago, insurers, payers, and employers did not see the value of primary care, but now, the adoption of the patient-centered medical home “has proven in the real world that we are the key to the triple aim” of increasing access, increasing quality, and reducing cost, Dr. Cain said.

Medicare is also paying for value, in part through grants from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, he said.

Even President Obama has spoken publicly “about the need to make family medicine the hub of patient-centered care,” Dr. Cain said. “We have not arrived, but we’re on our way.”

In 2007, family medicine had the lowest match rate ever recorded, but the number of matches has increased each year for the past 5 years. There are now 26,000 student members of the AAFP today – one in four U.S. medical students, Dr. Cain said.

Access to primary care has increased as well, he said. Six years ago, there were some 47 million uninsured Americans. The push for the Affordable Care Act “unleashed a political firestorm,” nationally and within the AAFP membership, Dr. Cain said.

The uninsured rate has dropped from 18% to about 13% currently, he said.

“Today I stand before you a witness to what I see as the rebirth of family medicine,” Dr. Cain said.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – Family medicine has gone from the brink of collapse to a rising specialty, American Academy of Family Physicians Board Chair Jeffrey Cain said Oct. 20 in a speech capping his service on the academy leadership team.

Dr. Cain noted that he began his run as an AAFP officer in 2007, a time when the “impending collapse” description had been bestowed upon family medicine by the Institute of Medicine. “For family medicine, it really was a time of crisis,” he said at the annual Congress of Delegates of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Payments were low, there was little student interest in the specialty, and some 47 million Americans were uninsured, he said.

“We’ve actually stopped that free fall of [family medicine] and we are now rising,” said Dr. Cain, who completes his term as board chair at the meeting.

Six years ago, insurers, payers, and employers did not see the value of primary care, but now, the adoption of the patient-centered medical home “has proven in the real world that we are the key to the triple aim” of increasing access, increasing quality, and reducing cost, Dr. Cain said.

Medicare is also paying for value, in part through grants from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, he said.

Even President Obama has spoken publicly “about the need to make family medicine the hub of patient-centered care,” Dr. Cain said. “We have not arrived, but we’re on our way.”

In 2007, family medicine had the lowest match rate ever recorded, but the number of matches has increased each year for the past 5 years. There are now 26,000 student members of the AAFP today – one in four U.S. medical students, Dr. Cain said.

Access to primary care has increased as well, he said. Six years ago, there were some 47 million uninsured Americans. The push for the Affordable Care Act “unleashed a political firestorm,” nationally and within the AAFP membership, Dr. Cain said.

The uninsured rate has dropped from 18% to about 13% currently, he said.

“Today I stand before you a witness to what I see as the rebirth of family medicine,” Dr. Cain said.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – Family medicine has gone from the brink of collapse to a rising specialty, American Academy of Family Physicians Board Chair Jeffrey Cain said Oct. 20 in a speech capping his service on the academy leadership team.

Dr. Cain noted that he began his run as an AAFP officer in 2007, a time when the “impending collapse” description had been bestowed upon family medicine by the Institute of Medicine. “For family medicine, it really was a time of crisis,” he said at the annual Congress of Delegates of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Payments were low, there was little student interest in the specialty, and some 47 million Americans were uninsured, he said.

“We’ve actually stopped that free fall of [family medicine] and we are now rising,” said Dr. Cain, who completes his term as board chair at the meeting.

Six years ago, insurers, payers, and employers did not see the value of primary care, but now, the adoption of the patient-centered medical home “has proven in the real world that we are the key to the triple aim” of increasing access, increasing quality, and reducing cost, Dr. Cain said.

Medicare is also paying for value, in part through grants from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, he said.

Even President Obama has spoken publicly “about the need to make family medicine the hub of patient-centered care,” Dr. Cain said. “We have not arrived, but we’re on our way.”

In 2007, family medicine had the lowest match rate ever recorded, but the number of matches has increased each year for the past 5 years. There are now 26,000 student members of the AAFP today – one in four U.S. medical students, Dr. Cain said.

Access to primary care has increased as well, he said. Six years ago, there were some 47 million uninsured Americans. The push for the Affordable Care Act “unleashed a political firestorm,” nationally and within the AAFP membership, Dr. Cain said.

The uninsured rate has dropped from 18% to about 13% currently, he said.

“Today I stand before you a witness to what I see as the rebirth of family medicine,” Dr. Cain said.

On Twitter @aliciaault

AT THE AAFP CONGRESS OF DELEGATES 2014

Family docs mull abortion, EHRs, gun safety at AAFP Congress

WASHINGTON – Resolutions to end restrictions on abortion providers and to encourage discussion of gun safety predictably elicited significant debate during reference committee discussions at the American Academy of Family Physicians’ annual policy-making meeting.

The Reference Committee on Advocacy considered two abortion-related proposals submitted by the New York State chapter, both aimed at removing state-imposed restrictions on providers, such as requiring physicians who provide the services to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital.

Currently, 27 states have laws that restrict abortion providers, said Dr. Cathleen London of Weill Cornell Physicians, N.Y., an author of the two resolutions. The statutes interfere with access to care, and do not add protections for patients, she said.

“Regardless of where you stand on this issue, making abortion difficult or illegal means that we’ll see abortions performed unsafely,” Dr. London said. “It will not stop them.”

Dr. Reid B. Blackwelder, AAFP president, urged the committee to forward the resolutions to the board of directors for study rather than vote on them directly. “We’d also like to note that the AAFP has adopted a neutral position on abortion,” said Dr. Blackwelder.

But Dr. Robert Reneker of Mercy Health in Grand Rapids, Mich., supported the organization’s neutral position. “To get mixed up in this debate on abortion, and to get off the fence, serves no purpose in furthering some of our other goals,” Dr. Reneker said.

A resolution introduced by the Michigan chapter urges the AAFP to be more outspoken on gun safety. Many delegates supported the resolution’s call for the academy to advocate for legislation that would call for safe gun storage in the home, while others objected to a provision that would allow health insurers in the Affordable Care Act’s health exchanges to collect data about guns in the home.

An opioid-related resolution from the New York State chapter urged the Food and Drug Administration to rescind approval of the long-acting hydrocodone formulation Zohydro. The drug has been viewed by many as highly abusable, but some palliative care and hospice specialists told the reference committee that it was a necessary therapy for their patients.

Delegates also vented about electronic health records. A late resolution introduced by Dr. Leonard Finn of Wellesley, Mass., laid out a wish list of improvements that he said AAFP should advocate, including interoperability.

EHRs “fail to help us do what we want to do – provide excellent care for our patients,” Dr. Finn told the Reference Committee on Practice Enhancement, adding, “No bank, no airline system would tolerate the quality of the software we have to work with.”

Dr. Cecil Bennett of Peachtree City, Ga., also expressed his frustration with current state of EHRs. “I don’t want to tweak the current system, I want to blow it up,” said Dr. Bennett.

The full Congress of Delegates will hear all of the resolutions and vote on them on Oct. 21 and Oct. 22.

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – Resolutions to end restrictions on abortion providers and to encourage discussion of gun safety predictably elicited significant debate during reference committee discussions at the American Academy of Family Physicians’ annual policy-making meeting.

The Reference Committee on Advocacy considered two abortion-related proposals submitted by the New York State chapter, both aimed at removing state-imposed restrictions on providers, such as requiring physicians who provide the services to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital.

Currently, 27 states have laws that restrict abortion providers, said Dr. Cathleen London of Weill Cornell Physicians, N.Y., an author of the two resolutions. The statutes interfere with access to care, and do not add protections for patients, she said.

“Regardless of where you stand on this issue, making abortion difficult or illegal means that we’ll see abortions performed unsafely,” Dr. London said. “It will not stop them.”

Dr. Reid B. Blackwelder, AAFP president, urged the committee to forward the resolutions to the board of directors for study rather than vote on them directly. “We’d also like to note that the AAFP has adopted a neutral position on abortion,” said Dr. Blackwelder.

But Dr. Robert Reneker of Mercy Health in Grand Rapids, Mich., supported the organization’s neutral position. “To get mixed up in this debate on abortion, and to get off the fence, serves no purpose in furthering some of our other goals,” Dr. Reneker said.