User login

Seven Years of Pain Between the Toes

ANSWER

The correct answer is soft corn (choice “c”). They are caused by bony friction and almost always found between the fourth and fifth toes.

Soft corns are often mistaken for warts (choice “a”). But warts don’t present as painful, macerated lesions between the toes.

Morton neuroma (choice “b”) is actually a neurofibroma, not a virtual tumor. It is usually found on the plantar forefoot between the second and third toes.

Interdigital fungal infections (choice “d”) often develop between the fourth and fifth toes and are often macerated. However, they do not take the form of lesions and do not hurt.

DISCUSSION

Soft corns are known in podiatric circles as heloma molle but are sometimes called kissing corns because they’re caused by friction between bony prominences on the fourth and fifth phalanges, which rub together with every step. Normally, these toes are hourglass shaped, but in patients prone to develop soft corns, the proximal bases of the toes are too wide. The type of shoe the patient wears can be an important factor as well, especially when high heels and/or narrow toe boxes are involved.

The treatment of soft corns can be nonsurgical—sometimes as simple as separating the toes with a tuft of lambswool. However, surgical intervention is often required. In such cases, the head of the proximal phalanx is cut and removed to make the adjacent bones more parallel. Occasionally, the skin is so damaged that it too must be removed and the toes sewn together.

Removing corns with chemicals, shaving, or excision provides no lasting relief, since these methods do not address the underlying structural issues.

Hard corns, also known as heloma durum, tend to develop on the dorsal aspect of the fifth toe secondary to pressure from shoes. Changing the type of shoe worn is one solution, but often, as with soft corns, the underlying bony prominence must be addressed.

There is a third type of corn, the periungual corn, which develops on or near the edge of a nail. These corns are often erroneously called warts.

This patient was referred to a podiatrist, who will likely solve the problem. There is no topical product that can help, and nonsurgical approaches will provide temporary relief at best.

ANSWER

The correct answer is soft corn (choice “c”). They are caused by bony friction and almost always found between the fourth and fifth toes.

Soft corns are often mistaken for warts (choice “a”). But warts don’t present as painful, macerated lesions between the toes.

Morton neuroma (choice “b”) is actually a neurofibroma, not a virtual tumor. It is usually found on the plantar forefoot between the second and third toes.

Interdigital fungal infections (choice “d”) often develop between the fourth and fifth toes and are often macerated. However, they do not take the form of lesions and do not hurt.

DISCUSSION

Soft corns are known in podiatric circles as heloma molle but are sometimes called kissing corns because they’re caused by friction between bony prominences on the fourth and fifth phalanges, which rub together with every step. Normally, these toes are hourglass shaped, but in patients prone to develop soft corns, the proximal bases of the toes are too wide. The type of shoe the patient wears can be an important factor as well, especially when high heels and/or narrow toe boxes are involved.

The treatment of soft corns can be nonsurgical—sometimes as simple as separating the toes with a tuft of lambswool. However, surgical intervention is often required. In such cases, the head of the proximal phalanx is cut and removed to make the adjacent bones more parallel. Occasionally, the skin is so damaged that it too must be removed and the toes sewn together.

Removing corns with chemicals, shaving, or excision provides no lasting relief, since these methods do not address the underlying structural issues.

Hard corns, also known as heloma durum, tend to develop on the dorsal aspect of the fifth toe secondary to pressure from shoes. Changing the type of shoe worn is one solution, but often, as with soft corns, the underlying bony prominence must be addressed.

There is a third type of corn, the periungual corn, which develops on or near the edge of a nail. These corns are often erroneously called warts.

This patient was referred to a podiatrist, who will likely solve the problem. There is no topical product that can help, and nonsurgical approaches will provide temporary relief at best.

ANSWER

The correct answer is soft corn (choice “c”). They are caused by bony friction and almost always found between the fourth and fifth toes.

Soft corns are often mistaken for warts (choice “a”). But warts don’t present as painful, macerated lesions between the toes.

Morton neuroma (choice “b”) is actually a neurofibroma, not a virtual tumor. It is usually found on the plantar forefoot between the second and third toes.

Interdigital fungal infections (choice “d”) often develop between the fourth and fifth toes and are often macerated. However, they do not take the form of lesions and do not hurt.

DISCUSSION

Soft corns are known in podiatric circles as heloma molle but are sometimes called kissing corns because they’re caused by friction between bony prominences on the fourth and fifth phalanges, which rub together with every step. Normally, these toes are hourglass shaped, but in patients prone to develop soft corns, the proximal bases of the toes are too wide. The type of shoe the patient wears can be an important factor as well, especially when high heels and/or narrow toe boxes are involved.

The treatment of soft corns can be nonsurgical—sometimes as simple as separating the toes with a tuft of lambswool. However, surgical intervention is often required. In such cases, the head of the proximal phalanx is cut and removed to make the adjacent bones more parallel. Occasionally, the skin is so damaged that it too must be removed and the toes sewn together.

Removing corns with chemicals, shaving, or excision provides no lasting relief, since these methods do not address the underlying structural issues.

Hard corns, also known as heloma durum, tend to develop on the dorsal aspect of the fifth toe secondary to pressure from shoes. Changing the type of shoe worn is one solution, but often, as with soft corns, the underlying bony prominence must be addressed.

There is a third type of corn, the periungual corn, which develops on or near the edge of a nail. These corns are often erroneously called warts.

This patient was referred to a podiatrist, who will likely solve the problem. There is no topical product that can help, and nonsurgical approaches will provide temporary relief at best.

For at least seven years, this 40-year-old man has had pain in the area between the fourth and fifth toes on his left foot. During that time, he has consulted clinicians in a number of settings—including urgent care centers and the emergency department—and received “at least 30” prescriptions for oral antibiotics. Given his persistent pain, none of these treatment attempts has helped. He spends a great deal of time on his feet at work, which worsens the pain. The only relief he experiences is when he goes home at night and removes his socks and shoes. Walking barefoot, he reports, results in relatively little discomfort. The patient claims to be in good health otherwise, specifically denying diabetes. He takes no medications regularly. The skin in the lowest point of the webspace between his fourth and fifth toes is focally thickened, white, and macerated, but there is no redness. The area is exquisitely tender to touch. Examination of the rest of his foot is unremarkable.

Erythematous Nodular Plaque Encircling the Lower Leg

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

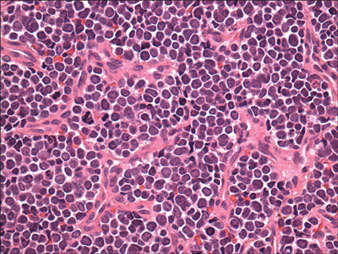

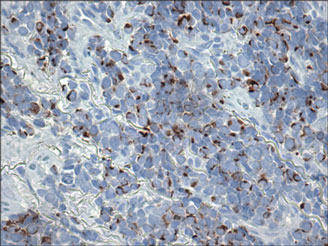

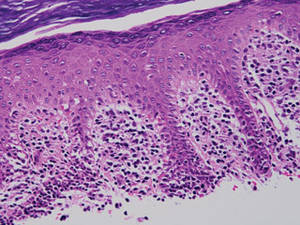

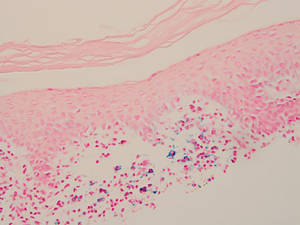

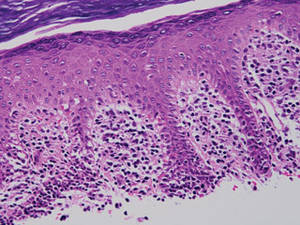

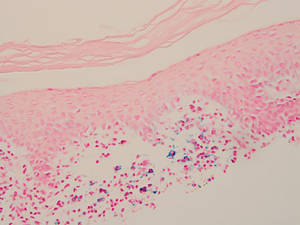

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6

A study of 251 patients in 1970-2002 showed that pathologic nodal staging identifies a group of patients with excellent long-term survival.1 Our patient preferred to undergo positron emission tomography rather than a sentinel lymph node biopsy prior to surgery. Also, after margin-negative excision and pathologic nodal staging, local and nodal recurrence rates were low. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients showed a trend (P=.08) to decreased survival compared with stage II patients who did not receive chemotherapy.7 A multidisciplinary approach to treatment including surgery, radiation,8 and chemotherapy needs to be created for each individual patient. Merkel cell carcinoma is the cause of death in 35% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare orphan tumor with rapidly increasing incidence in an era of immunosuppression. It has a grave prognosis, as demonstrated in our case, if not detected early. People at increased risk for MCC must have regular skin checks. Unfortunately, our patient was a nursing home resident and had not had a skin check for 2 years prior to presentation.

1. Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

2. Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

3. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

4. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

5. Assouline A, Tai P, Joseph K, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of skin-current controversies and recommendations.Rare Tumors. 2011;4:e23.

6. Paulson KG, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, et al. Antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus T-antigen oncoproteins reflect tumor burden in Merkel cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8388-8397.

7. Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

8. Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

9. Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6

A study of 251 patients in 1970-2002 showed that pathologic nodal staging identifies a group of patients with excellent long-term survival.1 Our patient preferred to undergo positron emission tomography rather than a sentinel lymph node biopsy prior to surgery. Also, after margin-negative excision and pathologic nodal staging, local and nodal recurrence rates were low. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients showed a trend (P=.08) to decreased survival compared with stage II patients who did not receive chemotherapy.7 A multidisciplinary approach to treatment including surgery, radiation,8 and chemotherapy needs to be created for each individual patient. Merkel cell carcinoma is the cause of death in 35% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare orphan tumor with rapidly increasing incidence in an era of immunosuppression. It has a grave prognosis, as demonstrated in our case, if not detected early. People at increased risk for MCC must have regular skin checks. Unfortunately, our patient was a nursing home resident and had not had a skin check for 2 years prior to presentation.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6

A study of 251 patients in 1970-2002 showed that pathologic nodal staging identifies a group of patients with excellent long-term survival.1 Our patient preferred to undergo positron emission tomography rather than a sentinel lymph node biopsy prior to surgery. Also, after margin-negative excision and pathologic nodal staging, local and nodal recurrence rates were low. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients showed a trend (P=.08) to decreased survival compared with stage II patients who did not receive chemotherapy.7 A multidisciplinary approach to treatment including surgery, radiation,8 and chemotherapy needs to be created for each individual patient. Merkel cell carcinoma is the cause of death in 35% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare orphan tumor with rapidly increasing incidence in an era of immunosuppression. It has a grave prognosis, as demonstrated in our case, if not detected early. People at increased risk for MCC must have regular skin checks. Unfortunately, our patient was a nursing home resident and had not had a skin check for 2 years prior to presentation.

1. Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

2. Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

3. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

4. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

5. Assouline A, Tai P, Joseph K, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of skin-current controversies and recommendations.Rare Tumors. 2011;4:e23.

6. Paulson KG, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, et al. Antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus T-antigen oncoproteins reflect tumor burden in Merkel cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8388-8397.

7. Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

8. Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

9. Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

1. Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

2. Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

3. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

4. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

5. Assouline A, Tai P, Joseph K, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of skin-current controversies and recommendations.Rare Tumors. 2011;4:e23.

6. Paulson KG, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, et al. Antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus T-antigen oncoproteins reflect tumor burden in Merkel cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8388-8397.

7. Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

8. Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

9. Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

A 66-year-old woman presented with red to violaceous, rapidly growing nodules on the skin. Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and renal failure. She had 2 rejected kidney transplants and was on hemodialysis at the time of presentation. She noticed asymptomatic nodules present on the left lower leg that progressively coalesced, finally encroaching the whole girth of the limb, spreading from the foot to the knee in a short duration of 3 months. The regional lymph nodes were not clinically palpable.

Erythematous Plaques on the Hand and Wrist

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

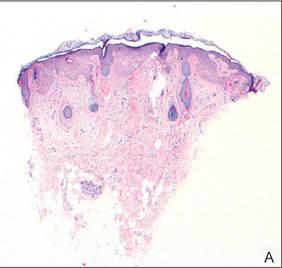

Lichen aureus (LA) is classified as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD), a collection of conditions that are characterized by petechiae, pigmentation, and occasionally telangiectasia without a causative underlying disorder. As in our case, the lesions of LA are usually asymptomatic. They appear as circumscribed areas of discrete or confluent macules and papules that can range in color from gold or copper to purple (Figure 1). The lesions typically occur unilaterally on the lower extremities but can occur on all body regions. The etiology is unknown, but explanations such as venous insufficiency,1 contact allergens,2 and drugs3,4 have been proposed. Unlike other PPDs, LA tends to occur abruptly and then either stabilizes or progresses slowly over years. Studies have reported resolution in 2 to 7 years.5 The average age of onset is in the 20s and 30s, with pediatric cases accounting for only 17%.6 Pediatric cases are more likely to be self-limited and occur in uncommon sites such as the trunk and arms.7

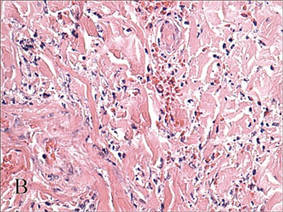

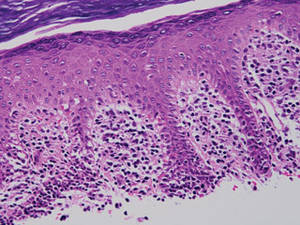

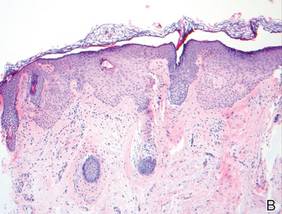

Lichen aureus is characterized histopathologically by a dense, bandlike, dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Additionally, there is variable exocytosis of lymphocytes and marked accumulation of siderotic macrophages (Figure 3). These qualities in the proper clinical setting help differentiate LA from other PPDs that share findings of capillaritis, hemosiderin deposition, and erythrocyte extravasation near dermal vessels. An iron stain assists in the diagnosis of LA (Figure 3), as it differentiates the disease from other lichenoid conditions such as lichen planus. Zaballos et al8 also demonstrated a role for dermoscopy to clinically differentiate LA from other similar-appearing lesions such as lichen planus.

The lesions of LA are benign. Because the predominantly T-cell infiltrate is monoclonal in approximately 50% of cases,2,9-11 authors have suggested the possibility of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9,12 Guitart and Magro13 classified LA as a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia with potential for progression. Despite these reports, the general consensus is that LA is a benign, self-limiting condition. The benign nature of LA is supported by Fink-Puches et al2 who followed 23 patients for a mean 102.1 months and did not observe a single case of progression to malignancy.

There have been many treatment regimens attempted for patients with LA. Topical corticosteroids have not been found to be beneficial14; however, there have been isolated cases reporting its efficacy in children.7,15 Other medications that have been effective in small trials include psoralen plus UVA,16 topical pimecrolimus,5 calcium dobesilate,17 and combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin.18 Despite some reported benefit, the use of potent immunomodulating medications is not indicated due to the benign nature of the disease. Alternative supplements including oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid have also been explored with modest benefit.19

1. Reinhardt L, Wilkin JK, Tausend R. Vascular abnormalities in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:417-420.

2. Fink-Puches R, Wolf P, Kerl H, et al. Lichen aureus: clinicopathologic features, natural history, and relationship to mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1169-1173.

3. Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

4. Yazdi AS, Mayser P, Sander CA. Lichen aureus with clonal T cells in a child possibly induced by regular consumption of an energy drink. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:960-962.

5. Bohm M, Bonsmann G, Luger TA. Resolution of lichen aureus in a 10-year-old child after topical pimecrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:519-520.

6. Gelmetti C, Cerri D, Grimalt R. Lichen aureus in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:280-283.

7. Kim MJ, Kim BY, Park KC, et al. A case of childhood lichen aureus. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:393-395.

8. Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

9. Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

10. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

11. Crowson AN, Magro CM, Zahorchak R. Atypical pigmentary purpura: a clinical, histopathologic, and genotypic study. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1004-1012.

12. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

13. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

14. Graham RM, English JS, Emmerson RW. Lichen aureus—a study of twelve cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:393-401.

15. Fujita H, Iguchi M, Ikari Y, et al. Lichen aureus on the back in a 6-year-old girl. J Dermatol. 2007;34:148-149.

16. Ling TC, Goulden V, Goodfield MJ. PUVA therapy in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:145-146.

17. Agrawal SK, Gandhi V, Bhattacharya SN. Calcium dobesilate (Cd) in pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD): a pilot evaluation. J Dermatol. 2004;31:98-103.

18. Lee HW, Lee DK, Chang SE, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1378-1380.

19. Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;4(2, pt 1):207-208.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

Lichen aureus (LA) is classified as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD), a collection of conditions that are characterized by petechiae, pigmentation, and occasionally telangiectasia without a causative underlying disorder. As in our case, the lesions of LA are usually asymptomatic. They appear as circumscribed areas of discrete or confluent macules and papules that can range in color from gold or copper to purple (Figure 1). The lesions typically occur unilaterally on the lower extremities but can occur on all body regions. The etiology is unknown, but explanations such as venous insufficiency,1 contact allergens,2 and drugs3,4 have been proposed. Unlike other PPDs, LA tends to occur abruptly and then either stabilizes or progresses slowly over years. Studies have reported resolution in 2 to 7 years.5 The average age of onset is in the 20s and 30s, with pediatric cases accounting for only 17%.6 Pediatric cases are more likely to be self-limited and occur in uncommon sites such as the trunk and arms.7

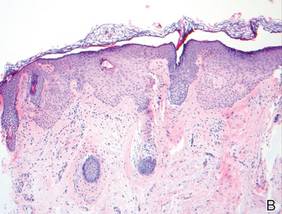

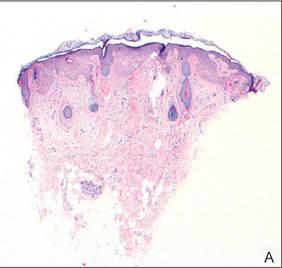

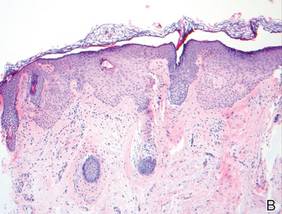

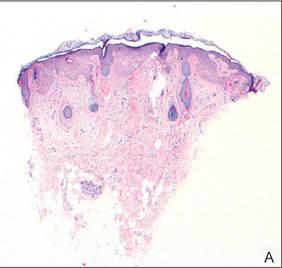

Lichen aureus is characterized histopathologically by a dense, bandlike, dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Additionally, there is variable exocytosis of lymphocytes and marked accumulation of siderotic macrophages (Figure 3). These qualities in the proper clinical setting help differentiate LA from other PPDs that share findings of capillaritis, hemosiderin deposition, and erythrocyte extravasation near dermal vessels. An iron stain assists in the diagnosis of LA (Figure 3), as it differentiates the disease from other lichenoid conditions such as lichen planus. Zaballos et al8 also demonstrated a role for dermoscopy to clinically differentiate LA from other similar-appearing lesions such as lichen planus.

The lesions of LA are benign. Because the predominantly T-cell infiltrate is monoclonal in approximately 50% of cases,2,9-11 authors have suggested the possibility of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9,12 Guitart and Magro13 classified LA as a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia with potential for progression. Despite these reports, the general consensus is that LA is a benign, self-limiting condition. The benign nature of LA is supported by Fink-Puches et al2 who followed 23 patients for a mean 102.1 months and did not observe a single case of progression to malignancy.

There have been many treatment regimens attempted for patients with LA. Topical corticosteroids have not been found to be beneficial14; however, there have been isolated cases reporting its efficacy in children.7,15 Other medications that have been effective in small trials include psoralen plus UVA,16 topical pimecrolimus,5 calcium dobesilate,17 and combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin.18 Despite some reported benefit, the use of potent immunomodulating medications is not indicated due to the benign nature of the disease. Alternative supplements including oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid have also been explored with modest benefit.19

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

Lichen aureus (LA) is classified as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD), a collection of conditions that are characterized by petechiae, pigmentation, and occasionally telangiectasia without a causative underlying disorder. As in our case, the lesions of LA are usually asymptomatic. They appear as circumscribed areas of discrete or confluent macules and papules that can range in color from gold or copper to purple (Figure 1). The lesions typically occur unilaterally on the lower extremities but can occur on all body regions. The etiology is unknown, but explanations such as venous insufficiency,1 contact allergens,2 and drugs3,4 have been proposed. Unlike other PPDs, LA tends to occur abruptly and then either stabilizes or progresses slowly over years. Studies have reported resolution in 2 to 7 years.5 The average age of onset is in the 20s and 30s, with pediatric cases accounting for only 17%.6 Pediatric cases are more likely to be self-limited and occur in uncommon sites such as the trunk and arms.7

Lichen aureus is characterized histopathologically by a dense, bandlike, dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Additionally, there is variable exocytosis of lymphocytes and marked accumulation of siderotic macrophages (Figure 3). These qualities in the proper clinical setting help differentiate LA from other PPDs that share findings of capillaritis, hemosiderin deposition, and erythrocyte extravasation near dermal vessels. An iron stain assists in the diagnosis of LA (Figure 3), as it differentiates the disease from other lichenoid conditions such as lichen planus. Zaballos et al8 also demonstrated a role for dermoscopy to clinically differentiate LA from other similar-appearing lesions such as lichen planus.

The lesions of LA are benign. Because the predominantly T-cell infiltrate is monoclonal in approximately 50% of cases,2,9-11 authors have suggested the possibility of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9,12 Guitart and Magro13 classified LA as a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia with potential for progression. Despite these reports, the general consensus is that LA is a benign, self-limiting condition. The benign nature of LA is supported by Fink-Puches et al2 who followed 23 patients for a mean 102.1 months and did not observe a single case of progression to malignancy.

There have been many treatment regimens attempted for patients with LA. Topical corticosteroids have not been found to be beneficial14; however, there have been isolated cases reporting its efficacy in children.7,15 Other medications that have been effective in small trials include psoralen plus UVA,16 topical pimecrolimus,5 calcium dobesilate,17 and combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin.18 Despite some reported benefit, the use of potent immunomodulating medications is not indicated due to the benign nature of the disease. Alternative supplements including oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid have also been explored with modest benefit.19

1. Reinhardt L, Wilkin JK, Tausend R. Vascular abnormalities in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:417-420.

2. Fink-Puches R, Wolf P, Kerl H, et al. Lichen aureus: clinicopathologic features, natural history, and relationship to mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1169-1173.

3. Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

4. Yazdi AS, Mayser P, Sander CA. Lichen aureus with clonal T cells in a child possibly induced by regular consumption of an energy drink. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:960-962.

5. Bohm M, Bonsmann G, Luger TA. Resolution of lichen aureus in a 10-year-old child after topical pimecrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:519-520.

6. Gelmetti C, Cerri D, Grimalt R. Lichen aureus in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:280-283.

7. Kim MJ, Kim BY, Park KC, et al. A case of childhood lichen aureus. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:393-395.

8. Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

9. Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

10. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

11. Crowson AN, Magro CM, Zahorchak R. Atypical pigmentary purpura: a clinical, histopathologic, and genotypic study. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1004-1012.

12. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

13. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

14. Graham RM, English JS, Emmerson RW. Lichen aureus—a study of twelve cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:393-401.

15. Fujita H, Iguchi M, Ikari Y, et al. Lichen aureus on the back in a 6-year-old girl. J Dermatol. 2007;34:148-149.

16. Ling TC, Goulden V, Goodfield MJ. PUVA therapy in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:145-146.

17. Agrawal SK, Gandhi V, Bhattacharya SN. Calcium dobesilate (Cd) in pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD): a pilot evaluation. J Dermatol. 2004;31:98-103.

18. Lee HW, Lee DK, Chang SE, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1378-1380.

19. Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;4(2, pt 1):207-208.

1. Reinhardt L, Wilkin JK, Tausend R. Vascular abnormalities in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:417-420.

2. Fink-Puches R, Wolf P, Kerl H, et al. Lichen aureus: clinicopathologic features, natural history, and relationship to mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1169-1173.

3. Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

4. Yazdi AS, Mayser P, Sander CA. Lichen aureus with clonal T cells in a child possibly induced by regular consumption of an energy drink. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:960-962.

5. Bohm M, Bonsmann G, Luger TA. Resolution of lichen aureus in a 10-year-old child after topical pimecrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:519-520.

6. Gelmetti C, Cerri D, Grimalt R. Lichen aureus in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:280-283.

7. Kim MJ, Kim BY, Park KC, et al. A case of childhood lichen aureus. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:393-395.

8. Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

9. Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

10. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

11. Crowson AN, Magro CM, Zahorchak R. Atypical pigmentary purpura: a clinical, histopathologic, and genotypic study. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1004-1012.

12. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

13. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

14. Graham RM, English JS, Emmerson RW. Lichen aureus—a study of twelve cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:393-401.

15. Fujita H, Iguchi M, Ikari Y, et al. Lichen aureus on the back in a 6-year-old girl. J Dermatol. 2007;34:148-149.

16. Ling TC, Goulden V, Goodfield MJ. PUVA therapy in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:145-146.

17. Agrawal SK, Gandhi V, Bhattacharya SN. Calcium dobesilate (Cd) in pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD): a pilot evaluation. J Dermatol. 2004;31:98-103.

18. Lee HW, Lee DK, Chang SE, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1378-1380.

19. Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;4(2, pt 1):207-208.

Large Subcutaneous Masses

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules on the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. His medical history was remarkable for alcoholism, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

Cutaneous Manifestations of Cocaine Use

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Cutaneous Vasculopathy

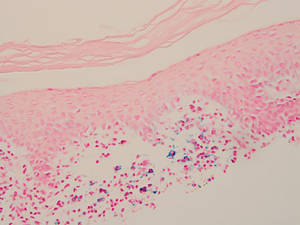

In our patient, tender stellate purpura and occasional bullae were present on the ears, arms and legs, groin, and buttocks (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination revealed subepidermal detachment, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation, consistent with early leukocyctoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

|

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy is a condition related primarily to cocaine use. Levamisole is an immunomodulatory agent, historically used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug for rheumatoid arthritis and as adjuvant chemotherapy for various types of cancer. However, levamisole for human use was banned from US and Canadian markets in 1999 and 2003, respectively, due to increased risk for agranulocytosis, retiform purpura, and epilepsy.1 Currently, veterinarians use levamisole as an anthelminthic agent to deworm house and farm animals. In Europe, pediatric nephrologists use it as a steroid-sparing agent in children with steroid-dependent nephritic syndrome.

Over the last decade, levamisole has increasingly been used as a cocaine adulterant or bulking agent. This contaminant closely resembles cocaine physically and is theorized to prolong or attenuate cocaine’s “high.” Approximately 69% of cocaine sampled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration is adulterated with levamisole.2 Similarly, levamisole-contaminated cocaine also has been found in Europe, Australia, and other parts of the world. Potential complications include vasculitis, thromboembolism, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis.3

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy appears to affect cocaine users of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Cocaine can be smoked, snorted, or injected. In nearly all reported cases, patients characteristically present with hemorrhagic bullae of the bilateral ear helix, cheeks, or nasal tip. Any body site can be affected with retiform purpura or necrotic bullae. Along with skin lesions, arthralgia is commonly reported, as are constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, malaise)4; oral mucosal involvement also has been reported.5 Laboratory investigation can reveal neutropenia, positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) in the perinuclear or cytoplasmic pattern, positive proteinase 3, and negative or mildly elevated antimyeloperoxidase.3-5 Acute renal injury and pulmonary hemorrhage are other potentially serious copmlications.4 Antihuman neutrophil elastase antibody testing can help distinguish levamisole-induced vasculopathy from other forms of immune-mediated vasculitis and will be negative in immune-mediated vasculitides such as Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis), Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis), and polyarteritis nodosa.6 On histology, microvascular thrombosis or leukocytoclastic vasculitis can both, or individually, be seen. Epidermal necrosis, dermal hemorrhage, and endothelial hyperplasia have all been noted in skin biopsied from necrotic bullae.

|

Levamisole’s short half-life (approximately 5–6 hours) makes it difficult to detect on routine blood draws. An astute physician suspecting this diagnosis on initial presentation can ask for levamisole detection on urine toxicology screening.7 Urine samples also can be sent for testing with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, though this test may only be available at major research centers.8

Differential diagnosis of levamisole toxicity includes different types of vasculitides such as cryoglobulinemia (positive serum IgM and IgG cryoglobulins; possible hepatitis C infection), Wegener granulomatosis (cytoplasmic ANCA positive; associated with upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation, glomerulonephritis), Churg-Strauss syndrome (perinuclear ANCA positive; associated with asthma and eosinophilia), and polyarteritis nodosa (medium vessel involvement only; associated with livedo reticularis, subcutaneous nodules, ulcers).9 Necrotic lesions also may raise the possibility of warfarin necrosis, heparin necrosis, or cholesterol emboli. Cholesterol embolism most frequently presents with small vessel vasculitis and necrosis of distal extremities such as the toes. With large areas of skin involvement and bullae, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis also should be considered.9

Definitive treatment of this condition requires complete and immediate cessation of cocaine use. Levamisole also has been found as a contaminant in heroin.1 Thus, it may be prudent to recommend heroin avoidance to the patient to prevent recurrences. Management of acute levamisole-induced vasculopathy is primarily symptomatic. Some patients with severe neutropenia at risk for infection have been treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, while others have only required pain control, usually with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10 Oral prednisone and colchicine also have been used with reported success.5

Given the increasing incidence of levamisole toxicity and public health implications, clinicians should be aware of this association and the classic clinical and laboratory findings.

1. Aberastury MN, Silva WH, Vaccarezza MM, et al. Epilepsia partialis continua associated with levamisole. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:385-388.

2. Nationwide public health alert issued concerning life-threatening risk posed by cocaine laced with veterinary anti-parasite drug [press release]. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; September 21, 2009. http://beta.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/200909211245. Accessed October 9, 2014.

3. Lee KC, Culpepper K, Kessler M. Levamisole-induced thrombosis: literature review and pertinent laboratory findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e128-e129.

4. McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

5. Poon SH, Baliog CR Jr, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leucopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

6. Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

7. Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

8. Trehy ML, Brown DJ, Woodruff JT, et al. Determination of levamisole in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2001;35:545-550.

9. Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

10. Zhu NY, Legatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:287-289.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Cutaneous Vasculopathy

In our patient, tender stellate purpura and occasional bullae were present on the ears, arms and legs, groin, and buttocks (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination revealed subepidermal detachment, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation, consistent with early leukocyctoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

|

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy is a condition related primarily to cocaine use. Levamisole is an immunomodulatory agent, historically used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug for rheumatoid arthritis and as adjuvant chemotherapy for various types of cancer. However, levamisole for human use was banned from US and Canadian markets in 1999 and 2003, respectively, due to increased risk for agranulocytosis, retiform purpura, and epilepsy.1 Currently, veterinarians use levamisole as an anthelminthic agent to deworm house and farm animals. In Europe, pediatric nephrologists use it as a steroid-sparing agent in children with steroid-dependent nephritic syndrome.

Over the last decade, levamisole has increasingly been used as a cocaine adulterant or bulking agent. This contaminant closely resembles cocaine physically and is theorized to prolong or attenuate cocaine’s “high.” Approximately 69% of cocaine sampled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration is adulterated with levamisole.2 Similarly, levamisole-contaminated cocaine also has been found in Europe, Australia, and other parts of the world. Potential complications include vasculitis, thromboembolism, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis.3

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy appears to affect cocaine users of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Cocaine can be smoked, snorted, or injected. In nearly all reported cases, patients characteristically present with hemorrhagic bullae of the bilateral ear helix, cheeks, or nasal tip. Any body site can be affected with retiform purpura or necrotic bullae. Along with skin lesions, arthralgia is commonly reported, as are constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, malaise)4; oral mucosal involvement also has been reported.5 Laboratory investigation can reveal neutropenia, positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) in the perinuclear or cytoplasmic pattern, positive proteinase 3, and negative or mildly elevated antimyeloperoxidase.3-5 Acute renal injury and pulmonary hemorrhage are other potentially serious copmlications.4 Antihuman neutrophil elastase antibody testing can help distinguish levamisole-induced vasculopathy from other forms of immune-mediated vasculitis and will be negative in immune-mediated vasculitides such as Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis), Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis), and polyarteritis nodosa.6 On histology, microvascular thrombosis or leukocytoclastic vasculitis can both, or individually, be seen. Epidermal necrosis, dermal hemorrhage, and endothelial hyperplasia have all been noted in skin biopsied from necrotic bullae.

|

Levamisole’s short half-life (approximately 5–6 hours) makes it difficult to detect on routine blood draws. An astute physician suspecting this diagnosis on initial presentation can ask for levamisole detection on urine toxicology screening.7 Urine samples also can be sent for testing with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, though this test may only be available at major research centers.8

Differential diagnosis of levamisole toxicity includes different types of vasculitides such as cryoglobulinemia (positive serum IgM and IgG cryoglobulins; possible hepatitis C infection), Wegener granulomatosis (cytoplasmic ANCA positive; associated with upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation, glomerulonephritis), Churg-Strauss syndrome (perinuclear ANCA positive; associated with asthma and eosinophilia), and polyarteritis nodosa (medium vessel involvement only; associated with livedo reticularis, subcutaneous nodules, ulcers).9 Necrotic lesions also may raise the possibility of warfarin necrosis, heparin necrosis, or cholesterol emboli. Cholesterol embolism most frequently presents with small vessel vasculitis and necrosis of distal extremities such as the toes. With large areas of skin involvement and bullae, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis also should be considered.9

Definitive treatment of this condition requires complete and immediate cessation of cocaine use. Levamisole also has been found as a contaminant in heroin.1 Thus, it may be prudent to recommend heroin avoidance to the patient to prevent recurrences. Management of acute levamisole-induced vasculopathy is primarily symptomatic. Some patients with severe neutropenia at risk for infection have been treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, while others have only required pain control, usually with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10 Oral prednisone and colchicine also have been used with reported success.5

Given the increasing incidence of levamisole toxicity and public health implications, clinicians should be aware of this association and the classic clinical and laboratory findings.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Cutaneous Vasculopathy

In our patient, tender stellate purpura and occasional bullae were present on the ears, arms and legs, groin, and buttocks (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination revealed subepidermal detachment, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation, consistent with early leukocyctoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

|

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy is a condition related primarily to cocaine use. Levamisole is an immunomodulatory agent, historically used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug for rheumatoid arthritis and as adjuvant chemotherapy for various types of cancer. However, levamisole for human use was banned from US and Canadian markets in 1999 and 2003, respectively, due to increased risk for agranulocytosis, retiform purpura, and epilepsy.1 Currently, veterinarians use levamisole as an anthelminthic agent to deworm house and farm animals. In Europe, pediatric nephrologists use it as a steroid-sparing agent in children with steroid-dependent nephritic syndrome.

Over the last decade, levamisole has increasingly been used as a cocaine adulterant or bulking agent. This contaminant closely resembles cocaine physically and is theorized to prolong or attenuate cocaine’s “high.” Approximately 69% of cocaine sampled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration is adulterated with levamisole.2 Similarly, levamisole-contaminated cocaine also has been found in Europe, Australia, and other parts of the world. Potential complications include vasculitis, thromboembolism, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis.3

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy appears to affect cocaine users of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Cocaine can be smoked, snorted, or injected. In nearly all reported cases, patients characteristically present with hemorrhagic bullae of the bilateral ear helix, cheeks, or nasal tip. Any body site can be affected with retiform purpura or necrotic bullae. Along with skin lesions, arthralgia is commonly reported, as are constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, malaise)4; oral mucosal involvement also has been reported.5 Laboratory investigation can reveal neutropenia, positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) in the perinuclear or cytoplasmic pattern, positive proteinase 3, and negative or mildly elevated antimyeloperoxidase.3-5 Acute renal injury and pulmonary hemorrhage are other potentially serious copmlications.4 Antihuman neutrophil elastase antibody testing can help distinguish levamisole-induced vasculopathy from other forms of immune-mediated vasculitis and will be negative in immune-mediated vasculitides such as Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis), Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis), and polyarteritis nodosa.6 On histology, microvascular thrombosis or leukocytoclastic vasculitis can both, or individually, be seen. Epidermal necrosis, dermal hemorrhage, and endothelial hyperplasia have all been noted in skin biopsied from necrotic bullae.

|

Levamisole’s short half-life (approximately 5–6 hours) makes it difficult to detect on routine blood draws. An astute physician suspecting this diagnosis on initial presentation can ask for levamisole detection on urine toxicology screening.7 Urine samples also can be sent for testing with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, though this test may only be available at major research centers.8

Differential diagnosis of levamisole toxicity includes different types of vasculitides such as cryoglobulinemia (positive serum IgM and IgG cryoglobulins; possible hepatitis C infection), Wegener granulomatosis (cytoplasmic ANCA positive; associated with upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation, glomerulonephritis), Churg-Strauss syndrome (perinuclear ANCA positive; associated with asthma and eosinophilia), and polyarteritis nodosa (medium vessel involvement only; associated with livedo reticularis, subcutaneous nodules, ulcers).9 Necrotic lesions also may raise the possibility of warfarin necrosis, heparin necrosis, or cholesterol emboli. Cholesterol embolism most frequently presents with small vessel vasculitis and necrosis of distal extremities such as the toes. With large areas of skin involvement and bullae, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis also should be considered.9

Definitive treatment of this condition requires complete and immediate cessation of cocaine use. Levamisole also has been found as a contaminant in heroin.1 Thus, it may be prudent to recommend heroin avoidance to the patient to prevent recurrences. Management of acute levamisole-induced vasculopathy is primarily symptomatic. Some patients with severe neutropenia at risk for infection have been treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, while others have only required pain control, usually with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10 Oral prednisone and colchicine also have been used with reported success.5

Given the increasing incidence of levamisole toxicity and public health implications, clinicians should be aware of this association and the classic clinical and laboratory findings.

1. Aberastury MN, Silva WH, Vaccarezza MM, et al. Epilepsia partialis continua associated with levamisole. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:385-388.

2. Nationwide public health alert issued concerning life-threatening risk posed by cocaine laced with veterinary anti-parasite drug [press release]. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; September 21, 2009. http://beta.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/200909211245. Accessed October 9, 2014.

3. Lee KC, Culpepper K, Kessler M. Levamisole-induced thrombosis: literature review and pertinent laboratory findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e128-e129.

4. McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

5. Poon SH, Baliog CR Jr, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leucopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

6. Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

7. Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

8. Trehy ML, Brown DJ, Woodruff JT, et al. Determination of levamisole in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2001;35:545-550.

9. Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

10. Zhu NY, Legatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:287-289.

1. Aberastury MN, Silva WH, Vaccarezza MM, et al. Epilepsia partialis continua associated with levamisole. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:385-388.

2. Nationwide public health alert issued concerning life-threatening risk posed by cocaine laced with veterinary anti-parasite drug [press release]. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; September 21, 2009. http://beta.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/200909211245. Accessed October 9, 2014.

3. Lee KC, Culpepper K, Kessler M. Levamisole-induced thrombosis: literature review and pertinent laboratory findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e128-e129.

4. McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

5. Poon SH, Baliog CR Jr, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leucopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

6. Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.