User login

Multiple Papules on the Eyelid Margin

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

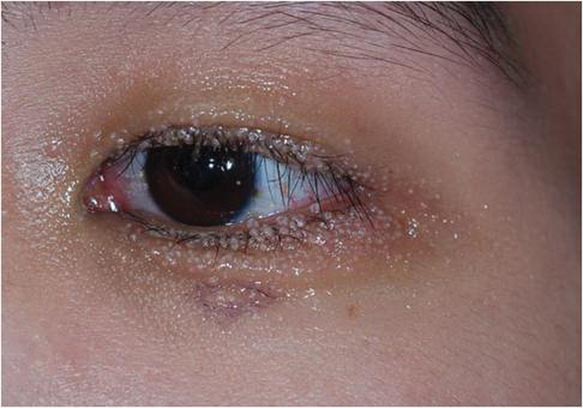

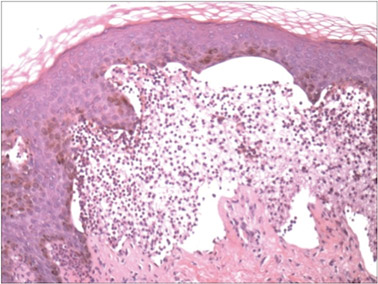

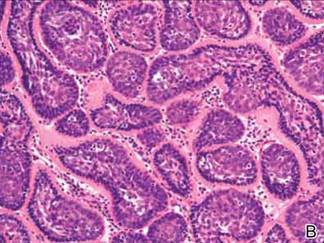

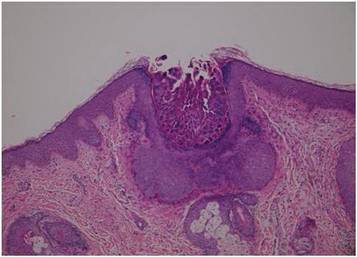

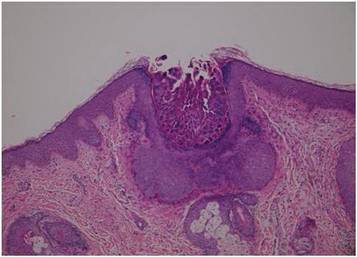

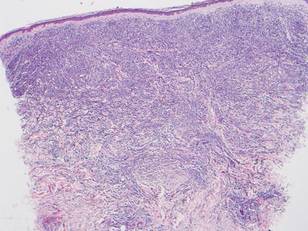

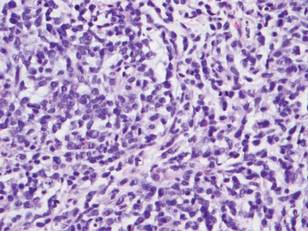

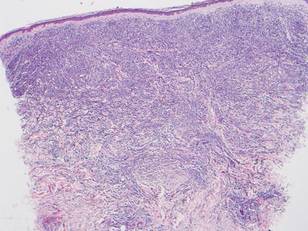

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

The Diagnosis: Molluscum Contagiosum

Dermoscopy showed multiple whitish amorphous structures with peripheral blood vessels (Figure 1). A skin biopsy specimen from the lower eyelid revealed loculated and endophytic epidermal hyperplasia. The keratinocytes contained large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, and the diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum (MC) was confirmed (Figure 2). Laboratory results were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 18 cells/mm3 and viral load of 199,686 copies/mL. The patient was treated with CO2 laser therapy for eyelid lesions. A regimen of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was later started using a combination of lamivudine-zidovudine (150 mg and 300 mg) as well as lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg), both twice daily. There was no recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

|

|

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection that is caused by a double-stranded DNA poxvirus. The clinical manifestations of MC are solitary or multiple, tiny, dome-shaped, pale, waxy or flesh-colored papules with central umbilication. The skin lesions can be located anywhere on the body. It occurs mostly in children, but adults also may be affected. In patients with atopic dermatitis or immunocompromised status such as AIDS, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, or treatment with prednisone and methotrexate, the cutaneous lesions may be more extensive with an atypical presentation.1-6

The diagnosis of MC is mainly made by clinical inspection. However, Giemsa staining, Papanicolaou tests, and histopathology are useful for diagnosis of atypical MC.7 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive and fast diagnostic tool for MC.8,9 In dermoscopy, MC is characterized by multiple spherical, whitish, amorphous structures with a crown of blood vessels surrounding the periphery, termed red corona.8,9 The whitish amorphous structures and red corona correlate with inclusion bodies and dermal dilated blood vessels, respectively.

Approximately 13% of HIV patients have cutaneous MC, and the lesions tend to be more diffuse and refractory to treatment.10 A giant variant and abscess formation also have been described.11,12 Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids often occurs in advanced HIV infection with a CD4 count less than 80 cells/mm3.1 These patients often have been diagnosed with HIV before developing eyelid MC. The severity of MC in immunocompromised patients may be related to the deficits of cell-mediated immunity, especially the T helper 1 (TH1) cytokine pathway. One case report also showed the clinical remission of MC after restoration of CD4 count with HAART.13 Our patient was not previously diagnosed with HIV and the MC of the eyelid margin was the early presentation of AIDS.

Molluscum contagiosum of the eyelids may cause chronic keratoconjunctivitis or even vascular infiltration and scarring of the peripheral cornea.14 These manifestations may be attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction to viral protein in tear film. Therefore, individuals with eyelid MC should accept thorough examination of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options include surgical excision, CO2 laser, curettage, and hyperfocal cryotherapy.15 Several reports also have demonstrated effectiveness of cidofovir for treatment of extensive MC lesions.16 Highly active antiretroviral therapy may play a role in the treatment of patients with AIDS by restoring the CD4 count.13 However, a few patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an intensive inflammatory reaction to pathogens after HAART, leading to paradoxical worsening of existing infection. Spontaneous corneal perforation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a case with eyelid and conjunctival MC has been reported.17 Therefore, physicians should perform MC therapy before HAART and mucocutaneous lesions should be followed regularly to prevent possible morbidity.

In summary, we report a case of AIDS with the initial presentation of MC on the eyelid margin. Physicians should test for HIV infection in patients with an atypical presentation of MC. The ocular mucosa also should be examined in patients with MC of the eyelid to prevent possible complications.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

1. Pérez-Blázquez E, Villafruela I, Madero S. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Orbit. 1999;18:75-81.

2. Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:e114-e116.

3. Moradi P, Bhogal M, Thaung C, et al. Epibulbar molluscum contagiosum lesions in multiple myeloma. Cornea. 2011;30:910-911.

4. Rosenberg EW, Yusk JW. Molluscum contagiosum. eruption following treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:439-441.

5. Yang CH, Lee WI, Hsu TS. Disseminated white papules. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:775-780.

6. Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

7. Kumar N, Okiro P, Wasike R. Cytological diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum with an unusual clinical presentation at an unusual site. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:63-65.

8. Micali G, Lacarrubba F. Augmented diagnostic capability using videodermatoscopy on selected infectious and non-infectious penile growths. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1501-1505.

9. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146.

10. Tzung TY, Yang CY, Chao SC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:216-224.

11. Chang W-Y, Chang C-P, Yang S-A, et al. Giant molluscum contagiosum with concurrence of molluscum dermatitis. Dermatol Sinica. 2005;23:81-85.

12. Bates CM, Carey PB, Dhar J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum—a novel presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:614-615.

13. Schulz D, Sarra GM, Koerner UB, et al. Evolution of HIV-1-related conjunctival molluscum contagiosum under HAART: report of a bilaterally manifesting case and literature review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:951-955.

14. Redmond RM. Molluscum contagiosum is not always benign. BMJ. 2004;329:403.

15. Bardenstein DS, Elmets C. Hyperfocal cryotherapy of multiple molluscum contagiosum lesions in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:131-134.

16. Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

17. Williamson W, Dorot N, Mortemousque B, et al. Spontaneous corneal perforation and conjunctival molluscum contagiosum in a AIDS patient [in French]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:703-707.

A 24-year-old man presented with multiple tiny papules over the left eyelid margin of 2 to 3 months’ duration. There were a couple of papules on the left upper eyelid initially, but they progressed to the upper and lower eyelid margin after scratching. On physical examination, multiple whitish to flesh-colored pearly papules measuring 1 to 2 mm were located on the left eyelid margin. Palpebral follicular conjunctivitis also was noted.

Tense Bullae With Widespread Erosions

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

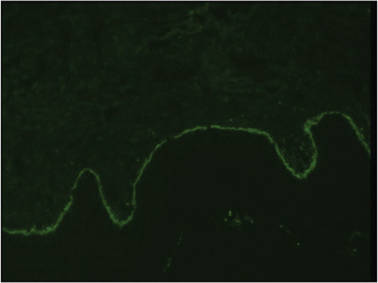

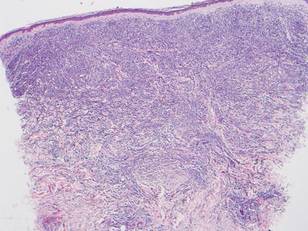

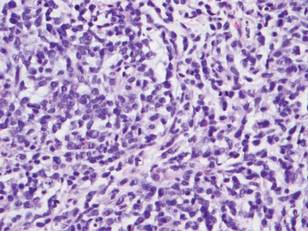

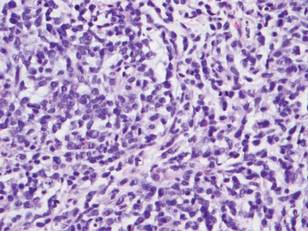

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

A 50-year-old black man presented with a new-onset widespread pruritic bullous eruption 7 months after being diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus. The CD4 lymphocyte count was 421 cells/mm3 and viral load was 7818 copies/mL. Results of a viral culture were negative for herpes simplex virus. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous intact tense bullae as well as scattered erosions on the trunk and extremities. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was prominent, with some areas of hypopigmentation and depigmentation.

Woman Awakens With Rapid Heart Rate

ANSWER

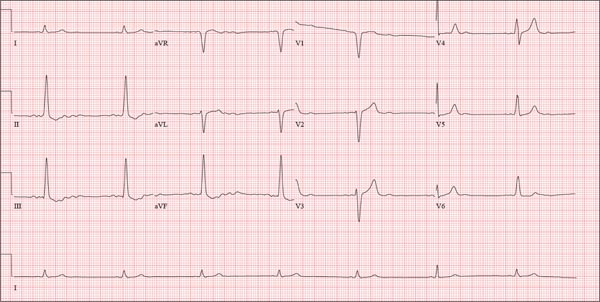

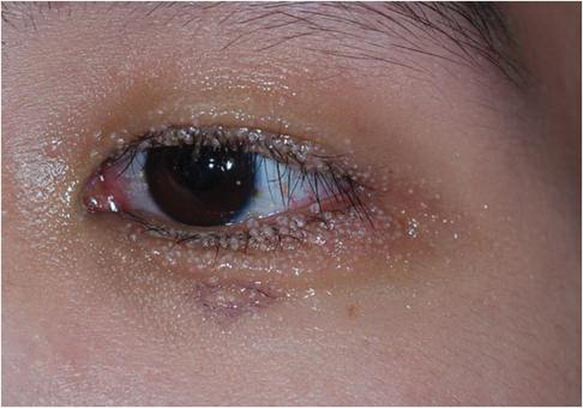

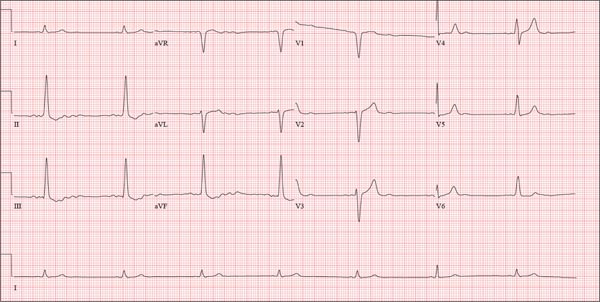

The correct interpretation of this ECG is atrial flutter with a 2:1 block. Careful inspection of lead I reveals a P wave at the terminal portion of the QRS complex, in addition to the P wave seen with a consistent PR interval of 150 ms. This results in two P waves for each QRS complex. Given the presence of the flutter waves, an accurate assessment of the ST segment is not possible.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG is atrial flutter with a 2:1 block. Careful inspection of lead I reveals a P wave at the terminal portion of the QRS complex, in addition to the P wave seen with a consistent PR interval of 150 ms. This results in two P waves for each QRS complex. Given the presence of the flutter waves, an accurate assessment of the ST segment is not possible.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG is atrial flutter with a 2:1 block. Careful inspection of lead I reveals a P wave at the terminal portion of the QRS complex, in addition to the P wave seen with a consistent PR interval of 150 ms. This results in two P waves for each QRS complex. Given the presence of the flutter waves, an accurate assessment of the ST segment is not possible.

Three nights ago, a 44-year-old woman awoke with a regular, rapid heart rate that lasted about 15 minutes before abruptly terminating. The next morning, at the hospital where she works as an emergency department (ED) nurse, she had a colleague perform an undocumented ECG that, by the patient’s account, was normal. Early this morning, she was again awakened by a similar regular but rapid heart rate. Not wanting anyone at her facility to know about the problem, she presents to your ED instead. She denies chest pain but admits that she is slightly short of breath, adding that her symptoms remind her of how she feels when finishing a 10K run. The patient has been in excellent health with no underlying medical problems and no prior cardiac history. She is an avid runner, averaging three miles a day, and does not smoke. She does report drinking two or three glasses of wine in the evenings and admits she likes to party on the weekends, frequently consuming three or four margaritas with her coworkers on Saturday nights. She experimented with cannabis in college but hasn’t used illicit or recreational drugs since graduating. The patient is divorced, has a steady boyfriend, and has no children or siblings. Her parents are alive and well, with no history of arrhythmias, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes. She has no known drug allergies. Her medications include an oral contraceptive and occasional ibuprofen for soreness following exercise. The review of systems is remarkable for menses, which began yesterday. She denies that she is pregnant. Her vision is corrected with contact lenses. Physical examination reveals a thin, athletic-appearing woman who seems anxious. Her height is 67 in and her weight, 132 lb. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 118/68 mm Hg; pulse, 150 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 37.8°C. The HEENT exam is normal with the presence of contact lenses. There is no thyromegaly. The lungs are clear in all fields. Her cardiac exam reveals a regular, rapid rate of 150 beats/min, without murmurs, rubs, or extra heart sounds. The abdomen is soft and nontender without palpable masses. The peripheral pulses are strong and equal bilaterally. There is no peripheral edema. The neurologic exam is intact. Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count, thyroid panel, and chemistry panel, are performed. All values are within normal limits. An ECG reveals a ventricular rate of 149 beats/min; PR interval, 150 ms; QRS interval, 102 ms; QT/QTc interval, 270/425 ms; P axis, 103°; R axis, 78°; and T axis, –18°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Left Arm Pain, Numbness, and Weakness

ANSWER

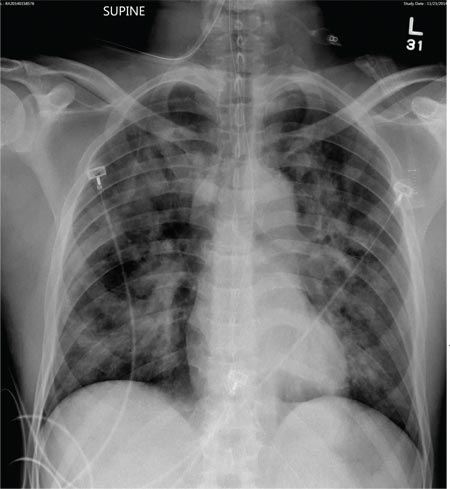

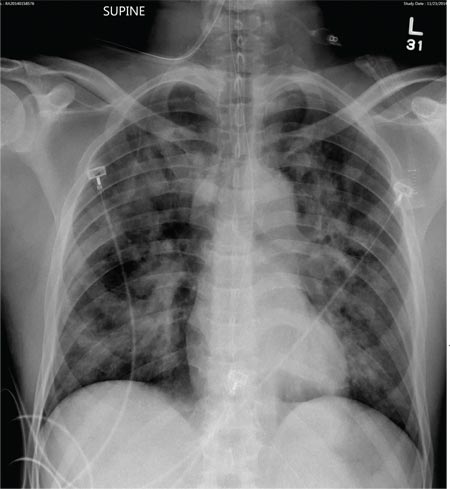

The radiograph shows no evidence of a fracture. However, there is a 2-cm focal sclerotic area noted within the juncture of the humeral neck and head. This finding could represent an enchondroma, a bone cyst, or a bone infarct. Additional imaging, including MRI and bone scan, is warranted, as is orthopedic evaluation. This finding is likely incidental, as the patient’s clinical exam is suggestive of a cervical radiculitis referable to the herniated disc in her neck.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows no evidence of a fracture. However, there is a 2-cm focal sclerotic area noted within the juncture of the humeral neck and head. This finding could represent an enchondroma, a bone cyst, or a bone infarct. Additional imaging, including MRI and bone scan, is warranted, as is orthopedic evaluation. This finding is likely incidental, as the patient’s clinical exam is suggestive of a cervical radiculitis referable to the herniated disc in her neck.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows no evidence of a fracture. However, there is a 2-cm focal sclerotic area noted within the juncture of the humeral neck and head. This finding could represent an enchondroma, a bone cyst, or a bone infarct. Additional imaging, including MRI and bone scan, is warranted, as is orthopedic evaluation. This finding is likely incidental, as the patient’s clinical exam is suggestive of a cervical radiculitis referable to the herniated disc in her neck.

A 40-year-old woman presents to the urgent care clinic complaining of left arm pain with associated numbness and weakness. She denies any injury or trauma, adding that the pain manifested several months ago but has recently progressed. She has already undergone outpatient MRI of her neck; she was told she had some “herniated discs” and would need to see a specialist. Her medical history is significant for hypertension. On physical examination, the patient appears uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. Vital signs are normal. Tenderness is present at the left trapezius and the left shoulder. Mild weakness is present in the left arm; strength is 4/5 and grip strength, 3/5. Pulses are normal, and sensation is intact. Available medical records include a report from her recent MRI of the cervical spine. Findings include a moderate left-sided disc osteophyte at the C6-C7 level and resultant cervical stenosis. A radiograph of the left shoulder is obtained. What is your impression?

Lesions’ Pattern Helps Line Up Diagnosis

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen nitidus (choice “b”), a harmless, self-limited condition of unknown origin. The lesions’ flat-topped (planar) surfaces and tendency to form in linear configurations along lines of trauma (so-called Koebner phenomenon) are also features seen in lichen planus (choice “d”) lesions; however, the latter are almost always pruritic and purple in color. Ironically, the histologic pattern seen in both is almost identical.

An extremely common condition, molluscum contagiosum (choice “a”) presents with multiple tiny papules. But these are not planar, and most will have an umbilicated center. See the Discussion for ways to distinguish it from lichen nitidus.

Flat warts (choice “c”), known as verruca plana, can strongly resemble lichen nitidus, but they are not as flat-topped and do not appear white. They do Koebnerize, however, which occasionally makes the distinction difficult.

DISCUSSION

Lichen nitidus (LN) is an unusual but benign condition primarily affecting children and young adults. Due to the contrast, the white planar papules are easier to see on darker skin. As is the case with many dermatologic diagnoses, LN is easily identified if you’ve heard of it and therefore know what to expect—but much more difficult if you haven’t.

LN’s unique manifestation distinguishes it from other items in the differential. For example, molluscum and LN can easily be confused, especially since both primarily affect children. But the pathognomic central umbilication of molluscum lesions is the key distinguishing feature; the best way to highlight it is with a short blast of liquid nitrogen. (Usually, though, the planar surfaces of LN are sufficient to distinguish it from other conditions.)

In the United States, the term Koebner phenomenon refers to the tendency for lesions to form along areas of trauma, usually in a linear configuration. All four items in our differential can present in this way. However, the term auto-inoculation might be more properly applied to conditions such as warts and molluscum, since the trauma has merely inoculated the organism into the skin. Inflammatory conditions such as LN and lichen planus are not truly “spread” by the trauma.

Linearly configured lesions are sufficiently unusual in dermatology to warrant their own differential. Among those that can present in this manner are psoriasis, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, and vitiligo.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

Our LN patient did not require any treatment, nor was any possible. The condition is quite likely to clear on its own, leaving little if any evidence in its wake.

I often show affected patients and/or their parents pictures of these types of conditions from our textbooks, for added reassurance. And in this day and age, I direct them to websites where they can do more investigation on their own time.

The effective practice of dermatology (and of all medicine, for that matter) includes more than merely making a correct diagnosis: I believe we’re obliged to “sell” it as well.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen nitidus (choice “b”), a harmless, self-limited condition of unknown origin. The lesions’ flat-topped (planar) surfaces and tendency to form in linear configurations along lines of trauma (so-called Koebner phenomenon) are also features seen in lichen planus (choice “d”) lesions; however, the latter are almost always pruritic and purple in color. Ironically, the histologic pattern seen in both is almost identical.

An extremely common condition, molluscum contagiosum (choice “a”) presents with multiple tiny papules. But these are not planar, and most will have an umbilicated center. See the Discussion for ways to distinguish it from lichen nitidus.

Flat warts (choice “c”), known as verruca plana, can strongly resemble lichen nitidus, but they are not as flat-topped and do not appear white. They do Koebnerize, however, which occasionally makes the distinction difficult.

DISCUSSION

Lichen nitidus (LN) is an unusual but benign condition primarily affecting children and young adults. Due to the contrast, the white planar papules are easier to see on darker skin. As is the case with many dermatologic diagnoses, LN is easily identified if you’ve heard of it and therefore know what to expect—but much more difficult if you haven’t.

LN’s unique manifestation distinguishes it from other items in the differential. For example, molluscum and LN can easily be confused, especially since both primarily affect children. But the pathognomic central umbilication of molluscum lesions is the key distinguishing feature; the best way to highlight it is with a short blast of liquid nitrogen. (Usually, though, the planar surfaces of LN are sufficient to distinguish it from other conditions.)

In the United States, the term Koebner phenomenon refers to the tendency for lesions to form along areas of trauma, usually in a linear configuration. All four items in our differential can present in this way. However, the term auto-inoculation might be more properly applied to conditions such as warts and molluscum, since the trauma has merely inoculated the organism into the skin. Inflammatory conditions such as LN and lichen planus are not truly “spread” by the trauma.

Linearly configured lesions are sufficiently unusual in dermatology to warrant their own differential. Among those that can present in this manner are psoriasis, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, and vitiligo.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

Our LN patient did not require any treatment, nor was any possible. The condition is quite likely to clear on its own, leaving little if any evidence in its wake.

I often show affected patients and/or their parents pictures of these types of conditions from our textbooks, for added reassurance. And in this day and age, I direct them to websites where they can do more investigation on their own time.

The effective practice of dermatology (and of all medicine, for that matter) includes more than merely making a correct diagnosis: I believe we’re obliged to “sell” it as well.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen nitidus (choice “b”), a harmless, self-limited condition of unknown origin. The lesions’ flat-topped (planar) surfaces and tendency to form in linear configurations along lines of trauma (so-called Koebner phenomenon) are also features seen in lichen planus (choice “d”) lesions; however, the latter are almost always pruritic and purple in color. Ironically, the histologic pattern seen in both is almost identical.

An extremely common condition, molluscum contagiosum (choice “a”) presents with multiple tiny papules. But these are not planar, and most will have an umbilicated center. See the Discussion for ways to distinguish it from lichen nitidus.

Flat warts (choice “c”), known as verruca plana, can strongly resemble lichen nitidus, but they are not as flat-topped and do not appear white. They do Koebnerize, however, which occasionally makes the distinction difficult.

DISCUSSION

Lichen nitidus (LN) is an unusual but benign condition primarily affecting children and young adults. Due to the contrast, the white planar papules are easier to see on darker skin. As is the case with many dermatologic diagnoses, LN is easily identified if you’ve heard of it and therefore know what to expect—but much more difficult if you haven’t.

LN’s unique manifestation distinguishes it from other items in the differential. For example, molluscum and LN can easily be confused, especially since both primarily affect children. But the pathognomic central umbilication of molluscum lesions is the key distinguishing feature; the best way to highlight it is with a short blast of liquid nitrogen. (Usually, though, the planar surfaces of LN are sufficient to distinguish it from other conditions.)

In the United States, the term Koebner phenomenon refers to the tendency for lesions to form along areas of trauma, usually in a linear configuration. All four items in our differential can present in this way. However, the term auto-inoculation might be more properly applied to conditions such as warts and molluscum, since the trauma has merely inoculated the organism into the skin. Inflammatory conditions such as LN and lichen planus are not truly “spread” by the trauma.

Linearly configured lesions are sufficiently unusual in dermatology to warrant their own differential. Among those that can present in this manner are psoriasis, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, and vitiligo.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

Our LN patient did not require any treatment, nor was any possible. The condition is quite likely to clear on its own, leaving little if any evidence in its wake.

I often show affected patients and/or their parents pictures of these types of conditions from our textbooks, for added reassurance. And in this day and age, I direct them to websites where they can do more investigation on their own time.

The effective practice of dermatology (and of all medicine, for that matter) includes more than merely making a correct diagnosis: I believe we’re obliged to “sell” it as well.

Six months ago, a 6-year-old boy developed asymptomatic lesions on his elbows, then his knees. They slowly spread to other areas, including his forearms. One primary care provider diagnosed probable warts; another, molluscum. The prescribed treatments—liquid nitrogen and tretinoin, respectively—had no effect. The boy’s mother became alarmed when the lesions started to form in long lines on his arms. At that point, she decided to bring him to dermatology for evaluation. Aside from his skin condition, the child is healthy, according to both his mother and the records provided by his primary care provider’s office. The lesions are particularly numerous over the extensor surfaces of the legs—especially the knees—but are also seen on the extensor forearms and elbows. The lesions are exquisitely discrete, identical, tiny white pinpoint papules, all with flat tops. None are umbilicated. In several areas of the arms, linear collections of lesions, some extending as long as 6 cm, are noted. The rest of his exposed type V skin is unremarkable.

Lobular-Appearing Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

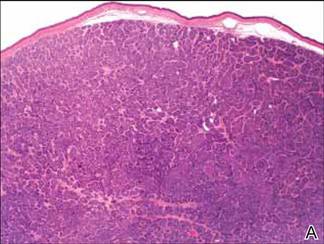

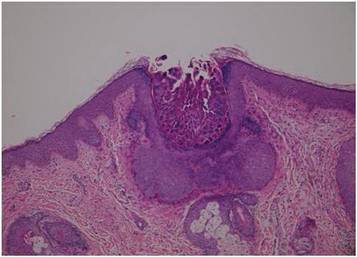

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

A 79-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the left side of the scalp of several years’ duration that had slowly increased in size. Despite its growth, the lesion remained asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, lobular-appearing nodule on the left side of the temporoparietal scalp, measuring 1.5 cm in size.

Lesions With a Distinct Fingerprint Presentation

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis (PPD) is a nonimmunologic cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory reaction resulting from the activation of photosensitizing botanical agents such as furanocoumarins in contact with the skin by exposure to UVA light.1,2 Furanocoumarins, including psoralens and angelicins, become photoexcited and covalently bind to pyrimidine bases on DNA strands, resulting in acute damage to epidermal, dermal, and endothelial cells.1,3

Vegetation most commonly implicated in this plant solar dermatitis are celery, fennel, parsnip, parsley, and hogweed (Apiaceae [formerly known as the Umbelliferae family]), as well as oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits (Rutaceae or citrus family).1,3 Psoralens found in the Persian lime have been noted to cause phototoxic eruptions in the United States, with the rind containing higher concentrations than the pulp.4

Clinical features of PPD include erythema, edema, and vesicle or bullae formation 12 to 36 hours after psoralen and UV light exposure. Burning and pain may be present, but pruritus is not a common characteristic of the eruptions, distinguishing PPD from allergic phytodermatitis.

Hyperpigmentation appears on resolution of the lesions and slowly fades over months to years.1,3,5 Mild exposure may lead to hyperpigmentation without a vesicular or erythematous eruption.1 Phytophotodermatitis follows a benign course and often spontaneously resolves; however, prolonged hyperpigmentation may cause concern for these patients.

Phytophotodermatitis is common among patients preparing drinks and foods with citrus juices or after gardening. Our patient had prepared limeade 3 weeks prior to presentation. The distribution of cutaneous exposure to furanocoumarins influences clinical presentation and may range from blotches and streaks to distinct fingerprint smudges and handprints, as seen in our patient. The distinct full handprint on the right arm was striking. The bullous lesions and resulting hyperpigmentation may mimic burns and healing bruises. In children, PPD often is mistaken for child abuse.1,6,7 In adults, it often is misdiagnosed as poison oak dermatitis, erythema multiforme, and thrombocytopenic purpura.1,3 It is important to recognize PPD to avoid delay in or misdiagnosis and to better counsel patients on how to avoid recurrent episodes of PPD.

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2008.

2. Pomeranz MK, Karen JK. Phytophotodermatitis and limes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:e1.

3. Sassiville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

4. Wagner AM, Wu JJ, Hansen RC, et al. Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:10-14.

5. Flugman SL. Mexican beer dermatitis: a unique variant of lime phytophotodermatitis attributable to contemporary beer-drinking practices. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1194-1195.

6. Mill J, Wallis B, Cuttle L, et al. Phytophotodermatitis: case reports of children presenting with blistering after preparing lime juice. Burns. 2008;34:731-733.

7. Carlsen K, Weismann K. Phytophotodermatitis in 19 children admitted to hospital and their differential diagnoses: child abuse and herpes simplex virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl):S88-S91.

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis (PPD) is a nonimmunologic cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory reaction resulting from the activation of photosensitizing botanical agents such as furanocoumarins in contact with the skin by exposure to UVA light.1,2 Furanocoumarins, including psoralens and angelicins, become photoexcited and covalently bind to pyrimidine bases on DNA strands, resulting in acute damage to epidermal, dermal, and endothelial cells.1,3

Vegetation most commonly implicated in this plant solar dermatitis are celery, fennel, parsnip, parsley, and hogweed (Apiaceae [formerly known as the Umbelliferae family]), as well as oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits (Rutaceae or citrus family).1,3 Psoralens found in the Persian lime have been noted to cause phototoxic eruptions in the United States, with the rind containing higher concentrations than the pulp.4

Clinical features of PPD include erythema, edema, and vesicle or bullae formation 12 to 36 hours after psoralen and UV light exposure. Burning and pain may be present, but pruritus is not a common characteristic of the eruptions, distinguishing PPD from allergic phytodermatitis.

Hyperpigmentation appears on resolution of the lesions and slowly fades over months to years.1,3,5 Mild exposure may lead to hyperpigmentation without a vesicular or erythematous eruption.1 Phytophotodermatitis follows a benign course and often spontaneously resolves; however, prolonged hyperpigmentation may cause concern for these patients.

Phytophotodermatitis is common among patients preparing drinks and foods with citrus juices or after gardening. Our patient had prepared limeade 3 weeks prior to presentation. The distribution of cutaneous exposure to furanocoumarins influences clinical presentation and may range from blotches and streaks to distinct fingerprint smudges and handprints, as seen in our patient. The distinct full handprint on the right arm was striking. The bullous lesions and resulting hyperpigmentation may mimic burns and healing bruises. In children, PPD often is mistaken for child abuse.1,6,7 In adults, it often is misdiagnosed as poison oak dermatitis, erythema multiforme, and thrombocytopenic purpura.1,3 It is important to recognize PPD to avoid delay in or misdiagnosis and to better counsel patients on how to avoid recurrent episodes of PPD.

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis (PPD) is a nonimmunologic cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory reaction resulting from the activation of photosensitizing botanical agents such as furanocoumarins in contact with the skin by exposure to UVA light.1,2 Furanocoumarins, including psoralens and angelicins, become photoexcited and covalently bind to pyrimidine bases on DNA strands, resulting in acute damage to epidermal, dermal, and endothelial cells.1,3

Vegetation most commonly implicated in this plant solar dermatitis are celery, fennel, parsnip, parsley, and hogweed (Apiaceae [formerly known as the Umbelliferae family]), as well as oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits (Rutaceae or citrus family).1,3 Psoralens found in the Persian lime have been noted to cause phototoxic eruptions in the United States, with the rind containing higher concentrations than the pulp.4

Clinical features of PPD include erythema, edema, and vesicle or bullae formation 12 to 36 hours after psoralen and UV light exposure. Burning and pain may be present, but pruritus is not a common characteristic of the eruptions, distinguishing PPD from allergic phytodermatitis.

Hyperpigmentation appears on resolution of the lesions and slowly fades over months to years.1,3,5 Mild exposure may lead to hyperpigmentation without a vesicular or erythematous eruption.1 Phytophotodermatitis follows a benign course and often spontaneously resolves; however, prolonged hyperpigmentation may cause concern for these patients.

Phytophotodermatitis is common among patients preparing drinks and foods with citrus juices or after gardening. Our patient had prepared limeade 3 weeks prior to presentation. The distribution of cutaneous exposure to furanocoumarins influences clinical presentation and may range from blotches and streaks to distinct fingerprint smudges and handprints, as seen in our patient. The distinct full handprint on the right arm was striking. The bullous lesions and resulting hyperpigmentation may mimic burns and healing bruises. In children, PPD often is mistaken for child abuse.1,6,7 In adults, it often is misdiagnosed as poison oak dermatitis, erythema multiforme, and thrombocytopenic purpura.1,3 It is important to recognize PPD to avoid delay in or misdiagnosis and to better counsel patients on how to avoid recurrent episodes of PPD.

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2008.

2. Pomeranz MK, Karen JK. Phytophotodermatitis and limes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:e1.

3. Sassiville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

4. Wagner AM, Wu JJ, Hansen RC, et al. Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:10-14.

5. Flugman SL. Mexican beer dermatitis: a unique variant of lime phytophotodermatitis attributable to contemporary beer-drinking practices. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1194-1195.

6. Mill J, Wallis B, Cuttle L, et al. Phytophotodermatitis: case reports of children presenting with blistering after preparing lime juice. Burns. 2008;34:731-733.