User login

Can a decrease in dopamine lead to binge eating?

In medical school, we were repeatedly advised that there is both a science and an art to the practice of medicine. In these days of doc-in-a-box online consultations for obesity, it’s tempting to think that there’s a one-size-fits-all purely scientific approach for these new weight loss medications. Yet, for every nine patients who lose weight seemingly effortlessly on this class of medication, there is always one whose body stubbornly refuses to submit.

Adam is a 58-year-old man who came to me recently because he was having difficulty losing weight. Over the past 20 years, he’d been steadily gaining weight and now, technically has morbid obesity (a term which should arguably be obsolete). His weight gain is complicated by high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obstructive sleep apnea. His sleep apnea has caused such profound exhaustion that he no longer has the energy to work out. He also has significant ADHD, which has been left untreated because of his ability to white-knuckle it through his many daily meetings and calls. A married father of three, he is a successful portfolio manager at a high-yield bond fund.

Adam tends to eat minimally during the day, thereby baffling his colleagues with the stark contrast between his minimal caloric intake and his large belly. However, when he returns from work late at night (kids safely tucked into bed), the floodgates open. He reports polishing off pints of ice cream, scarfing down bags of cookies, inhaling trays of brownies. No carbohydrate is off limits to him once he steps off the Metro North train and crosses the threshold from work to home.

Does Adam simply lack the desire or common-sense willpower to make the necessary changes in his lifestyle or is there something more complicated at play?

I would argue that Adam’s ADHD triggered a binge-eating disorder (BED) that festered unchecked over the past 20 years. Patients with BED typically eat massive quantities of food over short periods of time – often when they’re not even hungry. Adam admitted that he would generally continue to eat well after feeling stuffed to the brim.

The answer probably lies with dopamine, a neurotransmitter produced in the reward centers of the brain that regulates how people experience pleasure and control impulses. We believe that people with ADHD have low levels of dopamine (it’s actually a bit more complicated, but this is the general idea). These low levels of dopamine lead people to self-medicate with sugars, salt, and fats to increase dopamine levels.

Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is a Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment option for both ADHD and binge eating. It raises the levels of dopamine (as well as norepinephrine) in the brain’s reward center. Often, the strong urge to binge subsides rapidly once ADHD is properly treated.

Rather than starting Adam on a semaglutide or similar agent, I opted to start him on lisdexamfetamine. When I spoke to him 1 week later, he confided that the world suddenly shifted into focus, and he was able to plan his meals throughout the day and resist the urge to binge late at night.

I may eventually add a semaglutide-like medication if his weight loss plateaus, but for now, I will focus on raising his dopamine levels to tackle the underlying cause of his weight gain.

Dr. Messer is a clinical assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In medical school, we were repeatedly advised that there is both a science and an art to the practice of medicine. In these days of doc-in-a-box online consultations for obesity, it’s tempting to think that there’s a one-size-fits-all purely scientific approach for these new weight loss medications. Yet, for every nine patients who lose weight seemingly effortlessly on this class of medication, there is always one whose body stubbornly refuses to submit.

Adam is a 58-year-old man who came to me recently because he was having difficulty losing weight. Over the past 20 years, he’d been steadily gaining weight and now, technically has morbid obesity (a term which should arguably be obsolete). His weight gain is complicated by high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obstructive sleep apnea. His sleep apnea has caused such profound exhaustion that he no longer has the energy to work out. He also has significant ADHD, which has been left untreated because of his ability to white-knuckle it through his many daily meetings and calls. A married father of three, he is a successful portfolio manager at a high-yield bond fund.

Adam tends to eat minimally during the day, thereby baffling his colleagues with the stark contrast between his minimal caloric intake and his large belly. However, when he returns from work late at night (kids safely tucked into bed), the floodgates open. He reports polishing off pints of ice cream, scarfing down bags of cookies, inhaling trays of brownies. No carbohydrate is off limits to him once he steps off the Metro North train and crosses the threshold from work to home.

Does Adam simply lack the desire or common-sense willpower to make the necessary changes in his lifestyle or is there something more complicated at play?

I would argue that Adam’s ADHD triggered a binge-eating disorder (BED) that festered unchecked over the past 20 years. Patients with BED typically eat massive quantities of food over short periods of time – often when they’re not even hungry. Adam admitted that he would generally continue to eat well after feeling stuffed to the brim.

The answer probably lies with dopamine, a neurotransmitter produced in the reward centers of the brain that regulates how people experience pleasure and control impulses. We believe that people with ADHD have low levels of dopamine (it’s actually a bit more complicated, but this is the general idea). These low levels of dopamine lead people to self-medicate with sugars, salt, and fats to increase dopamine levels.

Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is a Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment option for both ADHD and binge eating. It raises the levels of dopamine (as well as norepinephrine) in the brain’s reward center. Often, the strong urge to binge subsides rapidly once ADHD is properly treated.

Rather than starting Adam on a semaglutide or similar agent, I opted to start him on lisdexamfetamine. When I spoke to him 1 week later, he confided that the world suddenly shifted into focus, and he was able to plan his meals throughout the day and resist the urge to binge late at night.

I may eventually add a semaglutide-like medication if his weight loss plateaus, but for now, I will focus on raising his dopamine levels to tackle the underlying cause of his weight gain.

Dr. Messer is a clinical assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In medical school, we were repeatedly advised that there is both a science and an art to the practice of medicine. In these days of doc-in-a-box online consultations for obesity, it’s tempting to think that there’s a one-size-fits-all purely scientific approach for these new weight loss medications. Yet, for every nine patients who lose weight seemingly effortlessly on this class of medication, there is always one whose body stubbornly refuses to submit.

Adam is a 58-year-old man who came to me recently because he was having difficulty losing weight. Over the past 20 years, he’d been steadily gaining weight and now, technically has morbid obesity (a term which should arguably be obsolete). His weight gain is complicated by high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obstructive sleep apnea. His sleep apnea has caused such profound exhaustion that he no longer has the energy to work out. He also has significant ADHD, which has been left untreated because of his ability to white-knuckle it through his many daily meetings and calls. A married father of three, he is a successful portfolio manager at a high-yield bond fund.

Adam tends to eat minimally during the day, thereby baffling his colleagues with the stark contrast between his minimal caloric intake and his large belly. However, when he returns from work late at night (kids safely tucked into bed), the floodgates open. He reports polishing off pints of ice cream, scarfing down bags of cookies, inhaling trays of brownies. No carbohydrate is off limits to him once he steps off the Metro North train and crosses the threshold from work to home.

Does Adam simply lack the desire or common-sense willpower to make the necessary changes in his lifestyle or is there something more complicated at play?

I would argue that Adam’s ADHD triggered a binge-eating disorder (BED) that festered unchecked over the past 20 years. Patients with BED typically eat massive quantities of food over short periods of time – often when they’re not even hungry. Adam admitted that he would generally continue to eat well after feeling stuffed to the brim.

The answer probably lies with dopamine, a neurotransmitter produced in the reward centers of the brain that regulates how people experience pleasure and control impulses. We believe that people with ADHD have low levels of dopamine (it’s actually a bit more complicated, but this is the general idea). These low levels of dopamine lead people to self-medicate with sugars, salt, and fats to increase dopamine levels.

Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is a Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment option for both ADHD and binge eating. It raises the levels of dopamine (as well as norepinephrine) in the brain’s reward center. Often, the strong urge to binge subsides rapidly once ADHD is properly treated.

Rather than starting Adam on a semaglutide or similar agent, I opted to start him on lisdexamfetamine. When I spoke to him 1 week later, he confided that the world suddenly shifted into focus, and he was able to plan his meals throughout the day and resist the urge to binge late at night.

I may eventually add a semaglutide-like medication if his weight loss plateaus, but for now, I will focus on raising his dopamine levels to tackle the underlying cause of his weight gain.

Dr. Messer is a clinical assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When does a bicarb drip make sense?

A 70-year-old woman is admitted to the intensive care unit with a pH of 7.1, an acute kidney injury (AKI), and ketonuria. She is volume depleted and her history is consistent with starvation ketosis. This LOL truly is in NAD (that’s little old lady in no acute distress, for those who haven’t read The House of God). She is clinically stable and seemingly unperturbed by the flurry of activity surrounding her admission.

Your resident is concerned by the severity of the acidosis and suggests starting an intravenous bicarbonate drip. The fellow is adamantly against it. He’s been taught that intravenous bicarbonate increases the serum pH but paradoxically causes intracellular acidosis. As the attending you elect to observe fellow autonomy – no bicarb is given. Because any debate on rounds is a “teachable moment,” you decide to review the evidence and physiology behind infusing bicarbonate.

What do the data reveal?

An excellent review published in CHEST in 2000 covers the physiologic effects of bicarbonate, specifically related to lactic acidosis, which our patient didn’t have. Aside from that difference, the review validates the fellow’s opinion. In short, It is unlikely to provoke hemodynamic or respiratory compromise outside the setting of shock or hypercapnia. Intravenous bicarbonate can lead to intracellular acidosis, hypercapnia, hypocalcemia, and a reduction in oxygen delivery via the Bohr effect. The authors concluded that because the benefits are unproven and the negative effects are real, intravenous bicarbonate should not be used to correct a metabolic acidosis.

The CHEST review hardly settles the issue, though. A survey published a few years later found a majority of intensivists and nephrologists used intravenous bicarbonate to treat metabolic acidosis while the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines for the Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock published in 2017 recommended against bicarbonate for acidosis. It wasn’t until 2018 that we reached the holy grail: a randomized controlled trial.

The BICAR-ICU study randomly assigned patients with a pH of 7.20 or less, PCO2 of 45 mm Hg or less, and sodium bicarbonate concentration of 20 mmol/L or less to receive no bicarbonate versus a sodium bicarbonate drip to maintain a pH greater than 7.30. There’s additional nuance to the trial design and even more detail in the results. To summarize, there was signal for an improvement in renal outcomes across all patients, and those with AKI saw a mortality benefit. Post–BICAR-ICU iterations of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines have incorporated these findings by recommending intravenous bicarbonate for patients with sepsis who have AKI and a pH of 7.20 or less.

That’s not to say BICAR-ICU has settled the issue. Although it’s far and away the best we have, there were fewer than 400 total patients in their intention-to-treat analysis. It was open label, with lots of crossover. The primary outcome was negative for the entire population, with only a subgroup (albeit a prespecified one) showing benefit. Finally, the results weren’t stratified by etiology for the metabolic acidosis. There was also evidence of alkalosis and hypocalcemia in the treatment group.

Last but not least in terms of importance, in most cases when bicarbonate is being considered, wouldn’t some form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) be preferred? This point was raised by nephrologists and intensivists when we covered BICAR-ICU in a journal club at my former program. It’s also mentioned in an accompanying editorial. RRT timing is controversial, and a detailed discussion is outside the scope of this piece and beyond the limits of my current knowledge base. But I do know that the A in the A-E-I-O-U acute indications for dialysis pneumonic stands for acidosis.

Our patient had AKI, a pH of 7.20 or less, and a pCO2 well under 45 mm Hg. Does BICAR-ICU support the resident’s inclination to start a drip? Sort of. The majority of patients enrolled in BICAR-ICU were in shock or were recovering from cardiac arrest, so it’s not clear the results can be generalized to our LOL with starvation ketosis. Extrapolating from studies of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) seems more appropriate, and here the data are poor but equivocal. Reviews are generally negative but don’t rule out the use of intravenous bicarbonate in certain patients with DKA.

Key takeaways

Our patient survived a 24-hour ICU stay with neither cardiopulmonary decompensation nor a need for RRT. Not sure how she did out of the ICU; presumably she was discharged soon after transfer. As is always the case with anecdotal medicine, the absence of a control prevents assessment of the counterfactual. Is it possible she may have done “better” with intravenous bicarbonate? Seems unlikely to me, though I doubt there would have been demonstrable adverse effects. Perhaps next time the fellow can observe resident autonomy?

Aaron B. Holley, MD, is a professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center. He reported conflicts of interest with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 70-year-old woman is admitted to the intensive care unit with a pH of 7.1, an acute kidney injury (AKI), and ketonuria. She is volume depleted and her history is consistent with starvation ketosis. This LOL truly is in NAD (that’s little old lady in no acute distress, for those who haven’t read The House of God). She is clinically stable and seemingly unperturbed by the flurry of activity surrounding her admission.

Your resident is concerned by the severity of the acidosis and suggests starting an intravenous bicarbonate drip. The fellow is adamantly against it. He’s been taught that intravenous bicarbonate increases the serum pH but paradoxically causes intracellular acidosis. As the attending you elect to observe fellow autonomy – no bicarb is given. Because any debate on rounds is a “teachable moment,” you decide to review the evidence and physiology behind infusing bicarbonate.

What do the data reveal?

An excellent review published in CHEST in 2000 covers the physiologic effects of bicarbonate, specifically related to lactic acidosis, which our patient didn’t have. Aside from that difference, the review validates the fellow’s opinion. In short, It is unlikely to provoke hemodynamic or respiratory compromise outside the setting of shock or hypercapnia. Intravenous bicarbonate can lead to intracellular acidosis, hypercapnia, hypocalcemia, and a reduction in oxygen delivery via the Bohr effect. The authors concluded that because the benefits are unproven and the negative effects are real, intravenous bicarbonate should not be used to correct a metabolic acidosis.

The CHEST review hardly settles the issue, though. A survey published a few years later found a majority of intensivists and nephrologists used intravenous bicarbonate to treat metabolic acidosis while the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines for the Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock published in 2017 recommended against bicarbonate for acidosis. It wasn’t until 2018 that we reached the holy grail: a randomized controlled trial.

The BICAR-ICU study randomly assigned patients with a pH of 7.20 or less, PCO2 of 45 mm Hg or less, and sodium bicarbonate concentration of 20 mmol/L or less to receive no bicarbonate versus a sodium bicarbonate drip to maintain a pH greater than 7.30. There’s additional nuance to the trial design and even more detail in the results. To summarize, there was signal for an improvement in renal outcomes across all patients, and those with AKI saw a mortality benefit. Post–BICAR-ICU iterations of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines have incorporated these findings by recommending intravenous bicarbonate for patients with sepsis who have AKI and a pH of 7.20 or less.

That’s not to say BICAR-ICU has settled the issue. Although it’s far and away the best we have, there were fewer than 400 total patients in their intention-to-treat analysis. It was open label, with lots of crossover. The primary outcome was negative for the entire population, with only a subgroup (albeit a prespecified one) showing benefit. Finally, the results weren’t stratified by etiology for the metabolic acidosis. There was also evidence of alkalosis and hypocalcemia in the treatment group.

Last but not least in terms of importance, in most cases when bicarbonate is being considered, wouldn’t some form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) be preferred? This point was raised by nephrologists and intensivists when we covered BICAR-ICU in a journal club at my former program. It’s also mentioned in an accompanying editorial. RRT timing is controversial, and a detailed discussion is outside the scope of this piece and beyond the limits of my current knowledge base. But I do know that the A in the A-E-I-O-U acute indications for dialysis pneumonic stands for acidosis.

Our patient had AKI, a pH of 7.20 or less, and a pCO2 well under 45 mm Hg. Does BICAR-ICU support the resident’s inclination to start a drip? Sort of. The majority of patients enrolled in BICAR-ICU were in shock or were recovering from cardiac arrest, so it’s not clear the results can be generalized to our LOL with starvation ketosis. Extrapolating from studies of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) seems more appropriate, and here the data are poor but equivocal. Reviews are generally negative but don’t rule out the use of intravenous bicarbonate in certain patients with DKA.

Key takeaways

Our patient survived a 24-hour ICU stay with neither cardiopulmonary decompensation nor a need for RRT. Not sure how she did out of the ICU; presumably she was discharged soon after transfer. As is always the case with anecdotal medicine, the absence of a control prevents assessment of the counterfactual. Is it possible she may have done “better” with intravenous bicarbonate? Seems unlikely to me, though I doubt there would have been demonstrable adverse effects. Perhaps next time the fellow can observe resident autonomy?

Aaron B. Holley, MD, is a professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center. He reported conflicts of interest with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 70-year-old woman is admitted to the intensive care unit with a pH of 7.1, an acute kidney injury (AKI), and ketonuria. She is volume depleted and her history is consistent with starvation ketosis. This LOL truly is in NAD (that’s little old lady in no acute distress, for those who haven’t read The House of God). She is clinically stable and seemingly unperturbed by the flurry of activity surrounding her admission.

Your resident is concerned by the severity of the acidosis and suggests starting an intravenous bicarbonate drip. The fellow is adamantly against it. He’s been taught that intravenous bicarbonate increases the serum pH but paradoxically causes intracellular acidosis. As the attending you elect to observe fellow autonomy – no bicarb is given. Because any debate on rounds is a “teachable moment,” you decide to review the evidence and physiology behind infusing bicarbonate.

What do the data reveal?

An excellent review published in CHEST in 2000 covers the physiologic effects of bicarbonate, specifically related to lactic acidosis, which our patient didn’t have. Aside from that difference, the review validates the fellow’s opinion. In short, It is unlikely to provoke hemodynamic or respiratory compromise outside the setting of shock or hypercapnia. Intravenous bicarbonate can lead to intracellular acidosis, hypercapnia, hypocalcemia, and a reduction in oxygen delivery via the Bohr effect. The authors concluded that because the benefits are unproven and the negative effects are real, intravenous bicarbonate should not be used to correct a metabolic acidosis.

The CHEST review hardly settles the issue, though. A survey published a few years later found a majority of intensivists and nephrologists used intravenous bicarbonate to treat metabolic acidosis while the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines for the Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock published in 2017 recommended against bicarbonate for acidosis. It wasn’t until 2018 that we reached the holy grail: a randomized controlled trial.

The BICAR-ICU study randomly assigned patients with a pH of 7.20 or less, PCO2 of 45 mm Hg or less, and sodium bicarbonate concentration of 20 mmol/L or less to receive no bicarbonate versus a sodium bicarbonate drip to maintain a pH greater than 7.30. There’s additional nuance to the trial design and even more detail in the results. To summarize, there was signal for an improvement in renal outcomes across all patients, and those with AKI saw a mortality benefit. Post–BICAR-ICU iterations of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines have incorporated these findings by recommending intravenous bicarbonate for patients with sepsis who have AKI and a pH of 7.20 or less.

That’s not to say BICAR-ICU has settled the issue. Although it’s far and away the best we have, there were fewer than 400 total patients in their intention-to-treat analysis. It was open label, with lots of crossover. The primary outcome was negative for the entire population, with only a subgroup (albeit a prespecified one) showing benefit. Finally, the results weren’t stratified by etiology for the metabolic acidosis. There was also evidence of alkalosis and hypocalcemia in the treatment group.

Last but not least in terms of importance, in most cases when bicarbonate is being considered, wouldn’t some form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) be preferred? This point was raised by nephrologists and intensivists when we covered BICAR-ICU in a journal club at my former program. It’s also mentioned in an accompanying editorial. RRT timing is controversial, and a detailed discussion is outside the scope of this piece and beyond the limits of my current knowledge base. But I do know that the A in the A-E-I-O-U acute indications for dialysis pneumonic stands for acidosis.

Our patient had AKI, a pH of 7.20 or less, and a pCO2 well under 45 mm Hg. Does BICAR-ICU support the resident’s inclination to start a drip? Sort of. The majority of patients enrolled in BICAR-ICU were in shock or were recovering from cardiac arrest, so it’s not clear the results can be generalized to our LOL with starvation ketosis. Extrapolating from studies of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) seems more appropriate, and here the data are poor but equivocal. Reviews are generally negative but don’t rule out the use of intravenous bicarbonate in certain patients with DKA.

Key takeaways

Our patient survived a 24-hour ICU stay with neither cardiopulmonary decompensation nor a need for RRT. Not sure how she did out of the ICU; presumably she was discharged soon after transfer. As is always the case with anecdotal medicine, the absence of a control prevents assessment of the counterfactual. Is it possible she may have done “better” with intravenous bicarbonate? Seems unlikely to me, though I doubt there would have been demonstrable adverse effects. Perhaps next time the fellow can observe resident autonomy?

Aaron B. Holley, MD, is a professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center. He reported conflicts of interest with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The magic of music

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m really going to miss Jimmy Buffett.

I’ve liked his music as far back as I can remember, and was lucky enough to see him in person in the mid-90s.

I’ve written about music before, but its affect on us never fails to amaze me. Songs can be background noise conducive to getting things done. They can also be in the foreground, serving as a mental vacation (or accompanying a real one). They can transport you to another place, briefly clearing your head from the daily goings-on around you. Even if it’s just during the drive home, it’s a welcome escape to a virtual beach and tropical drink.

Songs can bring back memories of certain events or people that we link them to. My dad loved anything by Neil Diamond, and nothing brings back thoughts of Dad more than when my iTunes randomly picks “I Am ... I Said.” Or John Williams’ Star Wars theme, taking me back to the summer of 1977 when I sat, spellbound, by this incredible movie whose magic is still going strong two generations later.

It’s amazing how our brain tries to make music out of nothing. Even in silence we have ear worms, the songs stuck in our head for hours to days (recently I’ve had “I Sing the Body Electric” from the 1980 movie Fame playing in there).

My office is over an MRI scanner, so I can always hear the chiller pumps softly running in the background. Sometimes my brain will turn their rhythmic chirping into a song, altering the pace of the song to fit them. The soft clicking of the ceiling fan, in my home office, does the same thing (for some reason my brain usually tries to fit “Yellow Submarine” to that one, no idea why).

Music is a part of that mysterious essence that makes us human. It touches all of us in some way, which varies between people, songs, and artists.

Jimmy Buffet’s music has a vacation vibe. Songs of the Caribbean & Keys, beaches, bars, boats, and tropical drinks. The 4:12 running time of his most well-known song, “Margaritaville,” gives a brief respite from my day when it comes on.

He passes into the beyond, to the sadness of his family, friends, and fans. But, unlike people, music can be immortal, and so he lives on through his creations. Like, Bach, Lennon, Bowie, Joplin, Sousa, and too many others to count, his work – and the enjoyment we get from it – are a gift left behind for the future.

Tight lines, Jimmy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The most important study from ESC: FRAIL-AF

One of the hardest tasks of a clinician is applying evidence from trials to the person in your office. At the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, the surprising and unexpected results of the FRAIL-AF trial confirm the massive challenge of evidence translation.

FRAIL-AF investigators set out to study the question of whether frail, elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who were doing well with vitamin K antagonists (VKA) should be switched to direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC).

Senior author Geert-Jan Geersing, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), told me that frustration led him to design this study. He was frustrated that colleagues assumed that evidence in nonfrail patients can always be translated to frail patients.

Dr. Geersing offered two reasons why common wisdom may be wrong. First was that the large DOAC versus warfarin trials included few elderly patients with frailty. Second, first author Linda Joosten, MD, made it clear in her presentation that frailty is a lot more than aging. It is a clinical syndrome, which entails a “high burden of comorbidities, dependency on others, and a reduced ability to resist stressors.”

The FRAIL-AF trial

The investigators recruited elderly, frail patients with fibrillation who were treated with VKAs and had stable international normalized ratios from outpatient clinics throughout the Netherlands. They screened about 2,600 patients and enrolled nearly 1,400. Most were excluded for not being frail.

Half the group was randomized to switching to a DOAC – drug choice was left to the treating clinician – and the other half remained on VKAs. Patients were 83 years of age on average with a mean CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4. All four classes of DOAC were used in the switching arm.

The primary endpoint was major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, whichever came first, accounting for death as a competing risk. Follow-up was 1 year.

The results for switching to DOAC vs. VKA

Dr. Joosten started her presentation with this: “The results turned out to be different than we expected.” The authors designed the trial with the idea that switching to DOACs would be superior in safety to remaining on VKAs.

But the trial was halted after an interim analysis found a rate of major bleeding in the switching arm of 15.3% versus 9.4% in the arm staying on VKA (hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.32; P = .0012).

The Kaplan-Meier event curves reveal that the excess risk of bleeding occurred after 100 days and increased with time. This argued against an early effect from transitioning the drugs.

An analysis looking at specific DOAC drugs revealed similar hazards for the two most common ones used – apixaban and rivaroxaban.

Thrombotic events were a secondary endpoint and were low in absolute numbers, 2.4% versus 2.0%, for remaining on VKA and switching to DOAC, respectively (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.60-2.61).

The time in therapeutic range in FRAIL-AF was similar to that in the seminal DOAC trials.

Comments

Three reasons lead me to choose FRAIL-AF as the most important study from the 2023 ESC congress.

First is the specific lesson about switching drugs. Note that FRAIL-AF did not address the question of starting anticoagulation. The trial results show that if you have a frail older patient who is doing well on VKA, don’t change to a DOAC. That is important to know, but it is not what gives this study its heft.

The second reason centers on the investigators choice to do this trial. Dr. Geersing had a feeling that common wisdom was wrong. He did not try to persuade colleagues with anecdote or plausibility or meta-analyses of observational studies. He set out to answer a question in the correct way – with a randomized trial.

This is the path forward in medicine. I’ve often heard proponents of observational research declare that many topics in medicine cannot be studied with trials. I could hear people arguing that it’s not feasible to study mostly home-bound, elderly frail patients. And the fact that there exist so few trials in this space would support that argument.

But the FRAIL-AF authors showed that it is possible. This is the kind of science that medicine should celebrate. There were no soft endpoints, financial conflicts, or spin. If medical science had science as its incentive, rather than attention, FRAIL-AF easily wins top honors.

The third reason FRAIL-AF is so important is that it teaches us the humility required in translating evidence in our clinics. I like to say evidence is what separates doctors from palm readers. But using this evidence requires thinking hard about how average effects in trial environments apply to our patient.

Yes, of course, there is clear evidence from tens of thousands of patients in the DOAC versus warfarin trials, that, for those patients, on average, DOACs compare favorably with VKA. The average age of patients in these trials was 70-73 years; the average age in FRAIL-AF was 83 years. And that is just age. A substudy of the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial found that only 360 of more than 20,000 patients in the trial had severe frailty.

That lesson extends to nearly every common therapy in medicine today. It also casts great doubt on the soft-thinking idea of using evidence from trials to derive quality metrics. As if the nuance of evidence translation can be captured in an electronic health record.

The skillful use of evidence will be one of the main challenges of the next generation of clinicians. Thanks to advances in medical science, more patients will live long enough to become frail. And the so-called “guideline-directed” therapies may not apply to them.

Dr. Joosten, Dr. Geersing, and the FRAIL-AF team have taught us specific lessons about anticoagulation, but their greatest contribution has been to demonstrate the value of humility in science and the practice of evidence-based medicine.

If you treat patients, no trial at this meeting is more important.

Dr. Mandrola is a clinical electrophysiologist at Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the hardest tasks of a clinician is applying evidence from trials to the person in your office. At the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, the surprising and unexpected results of the FRAIL-AF trial confirm the massive challenge of evidence translation.

FRAIL-AF investigators set out to study the question of whether frail, elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who were doing well with vitamin K antagonists (VKA) should be switched to direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC).

Senior author Geert-Jan Geersing, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), told me that frustration led him to design this study. He was frustrated that colleagues assumed that evidence in nonfrail patients can always be translated to frail patients.

Dr. Geersing offered two reasons why common wisdom may be wrong. First was that the large DOAC versus warfarin trials included few elderly patients with frailty. Second, first author Linda Joosten, MD, made it clear in her presentation that frailty is a lot more than aging. It is a clinical syndrome, which entails a “high burden of comorbidities, dependency on others, and a reduced ability to resist stressors.”

The FRAIL-AF trial

The investigators recruited elderly, frail patients with fibrillation who were treated with VKAs and had stable international normalized ratios from outpatient clinics throughout the Netherlands. They screened about 2,600 patients and enrolled nearly 1,400. Most were excluded for not being frail.

Half the group was randomized to switching to a DOAC – drug choice was left to the treating clinician – and the other half remained on VKAs. Patients were 83 years of age on average with a mean CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4. All four classes of DOAC were used in the switching arm.

The primary endpoint was major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, whichever came first, accounting for death as a competing risk. Follow-up was 1 year.

The results for switching to DOAC vs. VKA

Dr. Joosten started her presentation with this: “The results turned out to be different than we expected.” The authors designed the trial with the idea that switching to DOACs would be superior in safety to remaining on VKAs.

But the trial was halted after an interim analysis found a rate of major bleeding in the switching arm of 15.3% versus 9.4% in the arm staying on VKA (hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.32; P = .0012).

The Kaplan-Meier event curves reveal that the excess risk of bleeding occurred after 100 days and increased with time. This argued against an early effect from transitioning the drugs.

An analysis looking at specific DOAC drugs revealed similar hazards for the two most common ones used – apixaban and rivaroxaban.

Thrombotic events were a secondary endpoint and were low in absolute numbers, 2.4% versus 2.0%, for remaining on VKA and switching to DOAC, respectively (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.60-2.61).

The time in therapeutic range in FRAIL-AF was similar to that in the seminal DOAC trials.

Comments

Three reasons lead me to choose FRAIL-AF as the most important study from the 2023 ESC congress.

First is the specific lesson about switching drugs. Note that FRAIL-AF did not address the question of starting anticoagulation. The trial results show that if you have a frail older patient who is doing well on VKA, don’t change to a DOAC. That is important to know, but it is not what gives this study its heft.

The second reason centers on the investigators choice to do this trial. Dr. Geersing had a feeling that common wisdom was wrong. He did not try to persuade colleagues with anecdote or plausibility or meta-analyses of observational studies. He set out to answer a question in the correct way – with a randomized trial.

This is the path forward in medicine. I’ve often heard proponents of observational research declare that many topics in medicine cannot be studied with trials. I could hear people arguing that it’s not feasible to study mostly home-bound, elderly frail patients. And the fact that there exist so few trials in this space would support that argument.

But the FRAIL-AF authors showed that it is possible. This is the kind of science that medicine should celebrate. There were no soft endpoints, financial conflicts, or spin. If medical science had science as its incentive, rather than attention, FRAIL-AF easily wins top honors.

The third reason FRAIL-AF is so important is that it teaches us the humility required in translating evidence in our clinics. I like to say evidence is what separates doctors from palm readers. But using this evidence requires thinking hard about how average effects in trial environments apply to our patient.

Yes, of course, there is clear evidence from tens of thousands of patients in the DOAC versus warfarin trials, that, for those patients, on average, DOACs compare favorably with VKA. The average age of patients in these trials was 70-73 years; the average age in FRAIL-AF was 83 years. And that is just age. A substudy of the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial found that only 360 of more than 20,000 patients in the trial had severe frailty.

That lesson extends to nearly every common therapy in medicine today. It also casts great doubt on the soft-thinking idea of using evidence from trials to derive quality metrics. As if the nuance of evidence translation can be captured in an electronic health record.

The skillful use of evidence will be one of the main challenges of the next generation of clinicians. Thanks to advances in medical science, more patients will live long enough to become frail. And the so-called “guideline-directed” therapies may not apply to them.

Dr. Joosten, Dr. Geersing, and the FRAIL-AF team have taught us specific lessons about anticoagulation, but their greatest contribution has been to demonstrate the value of humility in science and the practice of evidence-based medicine.

If you treat patients, no trial at this meeting is more important.

Dr. Mandrola is a clinical electrophysiologist at Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the hardest tasks of a clinician is applying evidence from trials to the person in your office. At the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, the surprising and unexpected results of the FRAIL-AF trial confirm the massive challenge of evidence translation.

FRAIL-AF investigators set out to study the question of whether frail, elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who were doing well with vitamin K antagonists (VKA) should be switched to direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC).

Senior author Geert-Jan Geersing, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), told me that frustration led him to design this study. He was frustrated that colleagues assumed that evidence in nonfrail patients can always be translated to frail patients.

Dr. Geersing offered two reasons why common wisdom may be wrong. First was that the large DOAC versus warfarin trials included few elderly patients with frailty. Second, first author Linda Joosten, MD, made it clear in her presentation that frailty is a lot more than aging. It is a clinical syndrome, which entails a “high burden of comorbidities, dependency on others, and a reduced ability to resist stressors.”

The FRAIL-AF trial

The investigators recruited elderly, frail patients with fibrillation who were treated with VKAs and had stable international normalized ratios from outpatient clinics throughout the Netherlands. They screened about 2,600 patients and enrolled nearly 1,400. Most were excluded for not being frail.

Half the group was randomized to switching to a DOAC – drug choice was left to the treating clinician – and the other half remained on VKAs. Patients were 83 years of age on average with a mean CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4. All four classes of DOAC were used in the switching arm.

The primary endpoint was major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, whichever came first, accounting for death as a competing risk. Follow-up was 1 year.

The results for switching to DOAC vs. VKA

Dr. Joosten started her presentation with this: “The results turned out to be different than we expected.” The authors designed the trial with the idea that switching to DOACs would be superior in safety to remaining on VKAs.

But the trial was halted after an interim analysis found a rate of major bleeding in the switching arm of 15.3% versus 9.4% in the arm staying on VKA (hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.32; P = .0012).

The Kaplan-Meier event curves reveal that the excess risk of bleeding occurred after 100 days and increased with time. This argued against an early effect from transitioning the drugs.

An analysis looking at specific DOAC drugs revealed similar hazards for the two most common ones used – apixaban and rivaroxaban.

Thrombotic events were a secondary endpoint and were low in absolute numbers, 2.4% versus 2.0%, for remaining on VKA and switching to DOAC, respectively (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.60-2.61).

The time in therapeutic range in FRAIL-AF was similar to that in the seminal DOAC trials.

Comments

Three reasons lead me to choose FRAIL-AF as the most important study from the 2023 ESC congress.

First is the specific lesson about switching drugs. Note that FRAIL-AF did not address the question of starting anticoagulation. The trial results show that if you have a frail older patient who is doing well on VKA, don’t change to a DOAC. That is important to know, but it is not what gives this study its heft.

The second reason centers on the investigators choice to do this trial. Dr. Geersing had a feeling that common wisdom was wrong. He did not try to persuade colleagues with anecdote or plausibility or meta-analyses of observational studies. He set out to answer a question in the correct way – with a randomized trial.

This is the path forward in medicine. I’ve often heard proponents of observational research declare that many topics in medicine cannot be studied with trials. I could hear people arguing that it’s not feasible to study mostly home-bound, elderly frail patients. And the fact that there exist so few trials in this space would support that argument.

But the FRAIL-AF authors showed that it is possible. This is the kind of science that medicine should celebrate. There were no soft endpoints, financial conflicts, or spin. If medical science had science as its incentive, rather than attention, FRAIL-AF easily wins top honors.

The third reason FRAIL-AF is so important is that it teaches us the humility required in translating evidence in our clinics. I like to say evidence is what separates doctors from palm readers. But using this evidence requires thinking hard about how average effects in trial environments apply to our patient.

Yes, of course, there is clear evidence from tens of thousands of patients in the DOAC versus warfarin trials, that, for those patients, on average, DOACs compare favorably with VKA. The average age of patients in these trials was 70-73 years; the average age in FRAIL-AF was 83 years. And that is just age. A substudy of the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial found that only 360 of more than 20,000 patients in the trial had severe frailty.

That lesson extends to nearly every common therapy in medicine today. It also casts great doubt on the soft-thinking idea of using evidence from trials to derive quality metrics. As if the nuance of evidence translation can be captured in an electronic health record.

The skillful use of evidence will be one of the main challenges of the next generation of clinicians. Thanks to advances in medical science, more patients will live long enough to become frail. And the so-called “guideline-directed” therapies may not apply to them.

Dr. Joosten, Dr. Geersing, and the FRAIL-AF team have taught us specific lessons about anticoagulation, but their greatest contribution has been to demonstrate the value of humility in science and the practice of evidence-based medicine.

If you treat patients, no trial at this meeting is more important.

Dr. Mandrola is a clinical electrophysiologist at Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Decapitated’ boy saved by surgery team

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

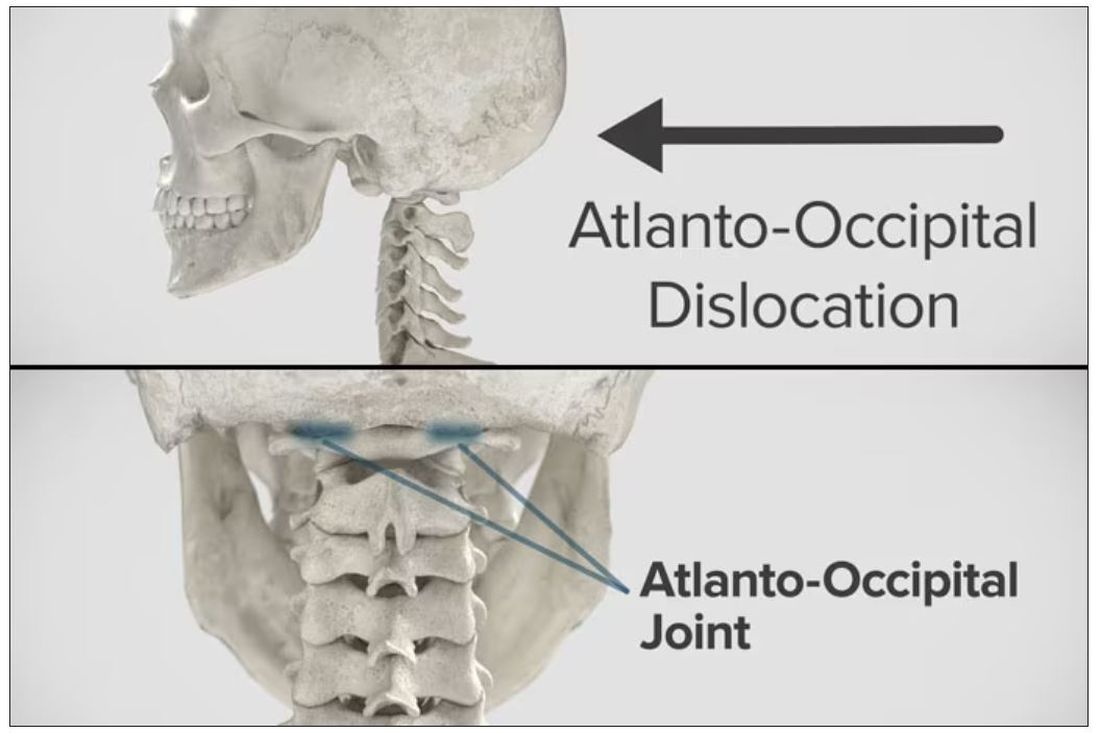

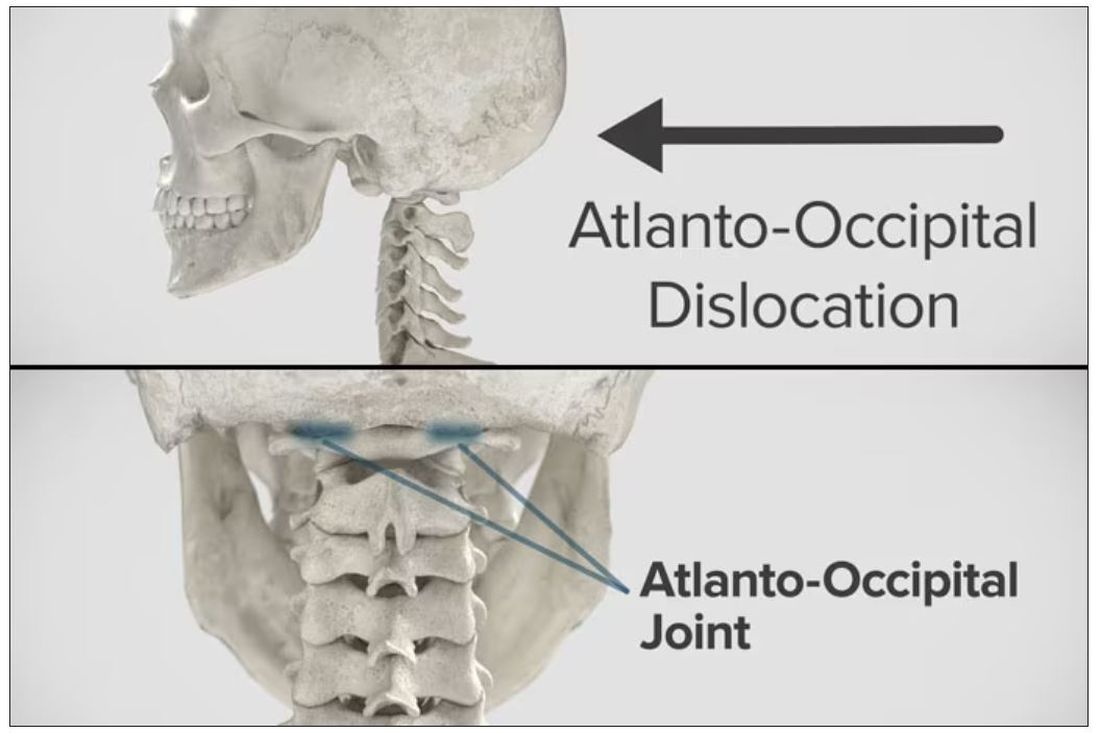

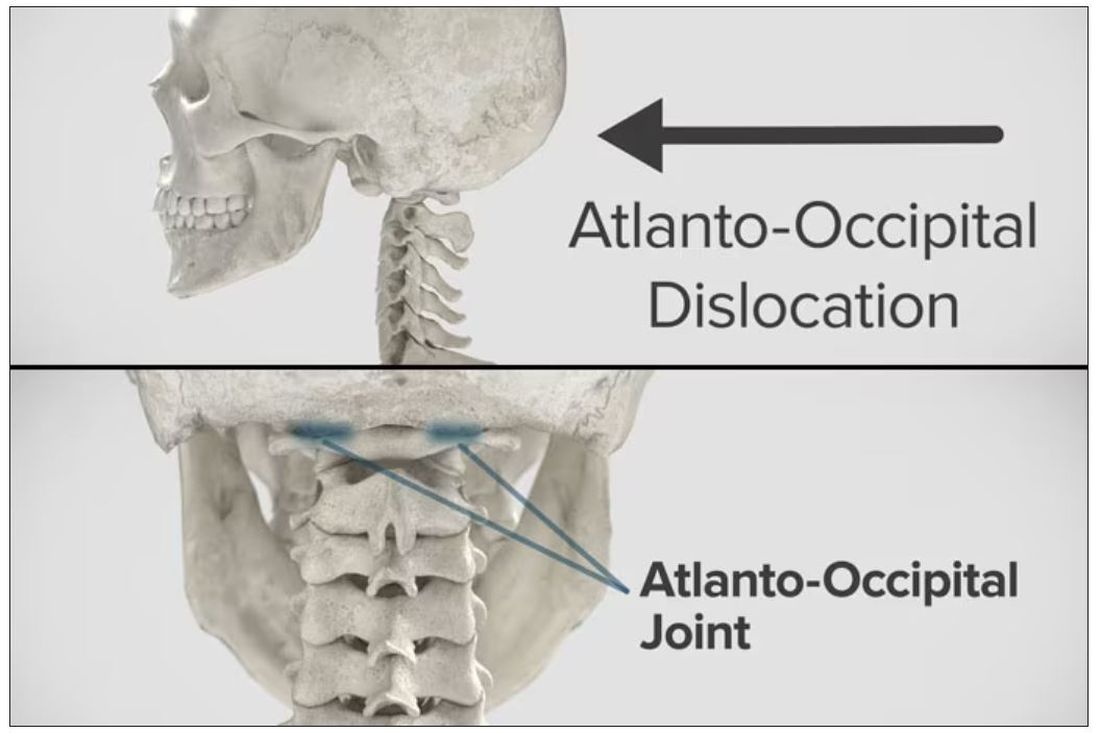

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Dr. Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the time frame.

Dr. Wilson: You’ve done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn’t very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Dr. Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Dr. Wilson: For those of us who aren’t surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you’re trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Dr. Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine – trauma and complex spine surgery – is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I’m going to do. I have a few plans – plan A, plan B, plan C – in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it’s not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I’m talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists – everyone.

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn’t a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Dr. Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company’s (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Dr. Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Dr. Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won’t be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan’s cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case there would be no chance of saving Hassan’s motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Dr. Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Dr. Einav: To be honest, I don’t remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call “flip-over.”

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope – inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan’s peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don’t know exactly how many.

Dr. Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you’re manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Dr. Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He’s doing well. He doesn’t have any motor or sensory deficits. He’s able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Dr. Wilson: That’s incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Dr. Einav: Yes, and that’s the reason that we are monitoring him post surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Dr. Wilson: He will grow, right? He’s only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Dr. Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn’t need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Dr. Wilson: What an incredible story. It’s clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan’s story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

Dr. Wilson: It’s inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here.

Dr. Einav: Thank you very much.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr. Ohad Einav. He’s a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He’s with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. But what we don’t have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr. Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Dr. Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

Dr. Wilson: “Injury to the cervical spine” might be something of an understatement. He had what’s called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Dr. Einav: It’s an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Dr. Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Dr. Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Dr. Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient’s status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Dr. Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ATLS [advanced trauma life support] protocol. He didn’t have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn’t rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn’t have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Dr. Wilson: It’s amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?