User login

Do New Antiobesity Meds Still Require Lifestyle Management?

Is lifestyle counseling needed with the more effective second-generation nutrient-stimulated, hormone-based medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide?

If so, how intensive does the counseling need to be, and what components should be emphasized?

These are the clinical practice questions at the top of mind for healthcare professionals and researchers who provide care to patients who have overweight and/or obesity.

This is what we know. Lifestyle management is considered foundational in the care of patients with obesity.

Because obesity is fundamentally a disease of energy dysregulation, counseling has traditionally focused on dietary caloric reduction, increased physical activity, and strategies to adapt new cognitive and lifestyle behaviors.

On the basis of trial results from the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Look AHEAD studies, provision of intensive behavioral therapy (IBT) is recommended for treatment of obesity by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and by the US Preventive Services Task Force (Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force).

IBT is commonly defined as consisting of 12-26 comprehensive and multicomponent sessions over the course of a year.

Reaffirming the primacy of lifestyle management, all antiobesity medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.

The beneficial effect of combining IBT with earlier-generation medications like naltrexone/bupropion or liraglutide demonstrated that more participants in the trials achieved ≥ 10% weight loss with IBT compared with those taking the medication without IBT: 38.4% vs 20% for naltrexone/bupropion and 46% vs 33% for liraglutide.

Although there aren’t trial data for other first-generation medications like phentermine, orlistat, or phentermine/topiramate, it is assumed that patients taking these medications would also achieve greater weight loss when combined with IBT.

The obesity pharmacotherapy landscape was upended, however, with the approval of semaglutide (Wegovy), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in 2021; and tirzepatide (Zepbound), a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide dual receptor agonist, in 2023.

These highly effective medications harness the effect of naturally occurring incretin hormones that reduce appetite through direct and indirect effects on the brain. Although the study designs differed between the STEP 1 and STEP 3 trials, the addition of IBT to semaglutide increased mean percent weight loss from 15% to 16% after 68 weeks of treatment (Wilding JPH et al; Wadden TA).

Comparable benefits from the STEP 3 and SURMOUNT-1 trials of adding IBT to tirzepatide at the maximal tolerated dose increased mean percent weight loss from 21% to 24% after 72 weeks (Wadden TA; Jastreboff AM). Though multicomponent IBT appears to provide greater weight loss when used with nutrient-stimulated hormone-based therapeutics, the additional benefit may be less when compared with first-generation medications.

So, how should we view the role and importance of lifestyle management when a patient is taking a second-generation medication? We need to shift the focus from prescribing a calorie-reduced diet to counseling for healthy eating patterns.

Because the second-generation drugs are more biologically effective in suppressing appetite (ie, reducing hunger, food noise, and cravings, and increasing satiation and satiety), it is easier for patients to reduce their food intake without a sense of deprivation. Furthermore, many patients express less desire to consume savory, sweet, and other enticing foods.

Patients should be encouraged to optimize the quality of their diet, prioritizing lean protein sources with meals and snacks; increasing fruits, vegetables, fiber, and complex carbohydrates; and keeping well hydrated. Because of the risk of developing micronutrient deficiencies while consuming a low-calorie diet — most notably calcium, iron, and vitamin D — patients may be advised to take a daily multivitamin supplement. Dietary counseling should be introduced when patients start pharmacotherapy, and if needed, referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist may be helpful in making these changes.

Additional counseling tips to mitigate the gastrointestinal side effects of these drugs that most commonly occur during the early dose-escalation phase include eating slowly; choosing smaller portion sizes; stopping eating when full; not skipping meals; and avoiding fatty, fried, and greasy foods. These dietary changes are particularly important over the first days after patients take the injection.

The increased weight loss achieved also raises concerns about the need to maintain lean body mass and the importance of physical activity and exercise counseling. All weight loss interventions, including dietary restriction, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery, result in loss of fat mass and lean body mass.

The goal of lifestyle counseling is to minimize and preserve muscle mass (a component of lean body mass) which is needed for optimal health, mobility, daily function, and quality of life. Counseling should incorporate both aerobic and resistance training. Aerobic exercise (eg, brisk walking, jogging, dancing, elliptical machine, and cycling) improves cardiovascular fitness, metabolic health, and energy expenditure. Resistance (strength) training (eg, weightlifting, resistance bands, and circuit training) lessens the loss of muscle mass, enhances functional strength and mobility, and improves bone density (Gorgojo-Martinez JJ et al; Oppert JM et al).

Robust physical activity has also been shown to be a predictor of weight loss maintenance. A recently published randomized placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of supervised exercise in maintaining body weight and lean body mass after discontinuing 52 weeks of liraglutide treatment compared with no exercise.

Rather than minimizing the provision of lifestyle management, using highly effective second-generation therapeutics redirects the focus on how patients with obesity can strive to achieve a healthy and productive life.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is lifestyle counseling needed with the more effective second-generation nutrient-stimulated, hormone-based medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide?

If so, how intensive does the counseling need to be, and what components should be emphasized?

These are the clinical practice questions at the top of mind for healthcare professionals and researchers who provide care to patients who have overweight and/or obesity.

This is what we know. Lifestyle management is considered foundational in the care of patients with obesity.

Because obesity is fundamentally a disease of energy dysregulation, counseling has traditionally focused on dietary caloric reduction, increased physical activity, and strategies to adapt new cognitive and lifestyle behaviors.

On the basis of trial results from the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Look AHEAD studies, provision of intensive behavioral therapy (IBT) is recommended for treatment of obesity by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and by the US Preventive Services Task Force (Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force).

IBT is commonly defined as consisting of 12-26 comprehensive and multicomponent sessions over the course of a year.

Reaffirming the primacy of lifestyle management, all antiobesity medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.

The beneficial effect of combining IBT with earlier-generation medications like naltrexone/bupropion or liraglutide demonstrated that more participants in the trials achieved ≥ 10% weight loss with IBT compared with those taking the medication without IBT: 38.4% vs 20% for naltrexone/bupropion and 46% vs 33% for liraglutide.

Although there aren’t trial data for other first-generation medications like phentermine, orlistat, or phentermine/topiramate, it is assumed that patients taking these medications would also achieve greater weight loss when combined with IBT.

The obesity pharmacotherapy landscape was upended, however, with the approval of semaglutide (Wegovy), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in 2021; and tirzepatide (Zepbound), a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide dual receptor agonist, in 2023.

These highly effective medications harness the effect of naturally occurring incretin hormones that reduce appetite through direct and indirect effects on the brain. Although the study designs differed between the STEP 1 and STEP 3 trials, the addition of IBT to semaglutide increased mean percent weight loss from 15% to 16% after 68 weeks of treatment (Wilding JPH et al; Wadden TA).

Comparable benefits from the STEP 3 and SURMOUNT-1 trials of adding IBT to tirzepatide at the maximal tolerated dose increased mean percent weight loss from 21% to 24% after 72 weeks (Wadden TA; Jastreboff AM). Though multicomponent IBT appears to provide greater weight loss when used with nutrient-stimulated hormone-based therapeutics, the additional benefit may be less when compared with first-generation medications.

So, how should we view the role and importance of lifestyle management when a patient is taking a second-generation medication? We need to shift the focus from prescribing a calorie-reduced diet to counseling for healthy eating patterns.

Because the second-generation drugs are more biologically effective in suppressing appetite (ie, reducing hunger, food noise, and cravings, and increasing satiation and satiety), it is easier for patients to reduce their food intake without a sense of deprivation. Furthermore, many patients express less desire to consume savory, sweet, and other enticing foods.

Patients should be encouraged to optimize the quality of their diet, prioritizing lean protein sources with meals and snacks; increasing fruits, vegetables, fiber, and complex carbohydrates; and keeping well hydrated. Because of the risk of developing micronutrient deficiencies while consuming a low-calorie diet — most notably calcium, iron, and vitamin D — patients may be advised to take a daily multivitamin supplement. Dietary counseling should be introduced when patients start pharmacotherapy, and if needed, referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist may be helpful in making these changes.

Additional counseling tips to mitigate the gastrointestinal side effects of these drugs that most commonly occur during the early dose-escalation phase include eating slowly; choosing smaller portion sizes; stopping eating when full; not skipping meals; and avoiding fatty, fried, and greasy foods. These dietary changes are particularly important over the first days after patients take the injection.

The increased weight loss achieved also raises concerns about the need to maintain lean body mass and the importance of physical activity and exercise counseling. All weight loss interventions, including dietary restriction, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery, result in loss of fat mass and lean body mass.

The goal of lifestyle counseling is to minimize and preserve muscle mass (a component of lean body mass) which is needed for optimal health, mobility, daily function, and quality of life. Counseling should incorporate both aerobic and resistance training. Aerobic exercise (eg, brisk walking, jogging, dancing, elliptical machine, and cycling) improves cardiovascular fitness, metabolic health, and energy expenditure. Resistance (strength) training (eg, weightlifting, resistance bands, and circuit training) lessens the loss of muscle mass, enhances functional strength and mobility, and improves bone density (Gorgojo-Martinez JJ et al; Oppert JM et al).

Robust physical activity has also been shown to be a predictor of weight loss maintenance. A recently published randomized placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of supervised exercise in maintaining body weight and lean body mass after discontinuing 52 weeks of liraglutide treatment compared with no exercise.

Rather than minimizing the provision of lifestyle management, using highly effective second-generation therapeutics redirects the focus on how patients with obesity can strive to achieve a healthy and productive life.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is lifestyle counseling needed with the more effective second-generation nutrient-stimulated, hormone-based medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide?

If so, how intensive does the counseling need to be, and what components should be emphasized?

These are the clinical practice questions at the top of mind for healthcare professionals and researchers who provide care to patients who have overweight and/or obesity.

This is what we know. Lifestyle management is considered foundational in the care of patients with obesity.

Because obesity is fundamentally a disease of energy dysregulation, counseling has traditionally focused on dietary caloric reduction, increased physical activity, and strategies to adapt new cognitive and lifestyle behaviors.

On the basis of trial results from the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Look AHEAD studies, provision of intensive behavioral therapy (IBT) is recommended for treatment of obesity by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and by the US Preventive Services Task Force (Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force).

IBT is commonly defined as consisting of 12-26 comprehensive and multicomponent sessions over the course of a year.

Reaffirming the primacy of lifestyle management, all antiobesity medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.

The beneficial effect of combining IBT with earlier-generation medications like naltrexone/bupropion or liraglutide demonstrated that more participants in the trials achieved ≥ 10% weight loss with IBT compared with those taking the medication without IBT: 38.4% vs 20% for naltrexone/bupropion and 46% vs 33% for liraglutide.

Although there aren’t trial data for other first-generation medications like phentermine, orlistat, or phentermine/topiramate, it is assumed that patients taking these medications would also achieve greater weight loss when combined with IBT.

The obesity pharmacotherapy landscape was upended, however, with the approval of semaglutide (Wegovy), a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in 2021; and tirzepatide (Zepbound), a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide dual receptor agonist, in 2023.

These highly effective medications harness the effect of naturally occurring incretin hormones that reduce appetite through direct and indirect effects on the brain. Although the study designs differed between the STEP 1 and STEP 3 trials, the addition of IBT to semaglutide increased mean percent weight loss from 15% to 16% after 68 weeks of treatment (Wilding JPH et al; Wadden TA).

Comparable benefits from the STEP 3 and SURMOUNT-1 trials of adding IBT to tirzepatide at the maximal tolerated dose increased mean percent weight loss from 21% to 24% after 72 weeks (Wadden TA; Jastreboff AM). Though multicomponent IBT appears to provide greater weight loss when used with nutrient-stimulated hormone-based therapeutics, the additional benefit may be less when compared with first-generation medications.

So, how should we view the role and importance of lifestyle management when a patient is taking a second-generation medication? We need to shift the focus from prescribing a calorie-reduced diet to counseling for healthy eating patterns.

Because the second-generation drugs are more biologically effective in suppressing appetite (ie, reducing hunger, food noise, and cravings, and increasing satiation and satiety), it is easier for patients to reduce their food intake without a sense of deprivation. Furthermore, many patients express less desire to consume savory, sweet, and other enticing foods.

Patients should be encouraged to optimize the quality of their diet, prioritizing lean protein sources with meals and snacks; increasing fruits, vegetables, fiber, and complex carbohydrates; and keeping well hydrated. Because of the risk of developing micronutrient deficiencies while consuming a low-calorie diet — most notably calcium, iron, and vitamin D — patients may be advised to take a daily multivitamin supplement. Dietary counseling should be introduced when patients start pharmacotherapy, and if needed, referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist may be helpful in making these changes.

Additional counseling tips to mitigate the gastrointestinal side effects of these drugs that most commonly occur during the early dose-escalation phase include eating slowly; choosing smaller portion sizes; stopping eating when full; not skipping meals; and avoiding fatty, fried, and greasy foods. These dietary changes are particularly important over the first days after patients take the injection.

The increased weight loss achieved also raises concerns about the need to maintain lean body mass and the importance of physical activity and exercise counseling. All weight loss interventions, including dietary restriction, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery, result in loss of fat mass and lean body mass.

The goal of lifestyle counseling is to minimize and preserve muscle mass (a component of lean body mass) which is needed for optimal health, mobility, daily function, and quality of life. Counseling should incorporate both aerobic and resistance training. Aerobic exercise (eg, brisk walking, jogging, dancing, elliptical machine, and cycling) improves cardiovascular fitness, metabolic health, and energy expenditure. Resistance (strength) training (eg, weightlifting, resistance bands, and circuit training) lessens the loss of muscle mass, enhances functional strength and mobility, and improves bone density (Gorgojo-Martinez JJ et al; Oppert JM et al).

Robust physical activity has also been shown to be a predictor of weight loss maintenance. A recently published randomized placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of supervised exercise in maintaining body weight and lean body mass after discontinuing 52 weeks of liraglutide treatment compared with no exercise.

Rather than minimizing the provision of lifestyle management, using highly effective second-generation therapeutics redirects the focus on how patients with obesity can strive to achieve a healthy and productive life.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Banned Chemical That Is Still Causing Cancer

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

These types of stories usually end with a call for regulation — to ban said chemical or substance, or to regulate it — but in this case, that has already happened. This new carcinogen I’m telling you about is actually an old chemical. And it has not been manufactured or legally imported in the US since 2013.

So, why bother? Because in this case, the chemical — or, really, a group of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) — are still around: in our soil, in our food, and in our blood.

PBDEs are a group of compounds that confer flame-retardant properties to plastics, and they were used extensively in the latter part of the 20th century in electronic enclosures, business equipment, and foam cushioning in upholstery.

But there was a problem. They don’t chemically bond to plastics; they are just sort of mixed in, which means they can leach out. They are hydrophobic, meaning they don’t get washed out of soil, and, when ingested or inhaled by humans, they dissolve in our fat stores, making it difficult for our normal excretory systems to excrete them.

PBDEs biomagnify. Small animals can take them up from contaminated soil or water, and those animals are eaten by larger animals, which accumulate higher concentrations of the chemicals. This bioaccumulation increases as you move up the food web until you get to an apex predator — like you and me.

This is true of lots of chemicals, of course. The concern arises when these chemicals are toxic. To date, the toxicity data for PBDEs were pretty limited. There were some animal studies where rats were exposed to extremely high doses and they developed liver lesions — but I am always very wary of extrapolating high-dose rat toxicity studies to humans. There was also some suggestion that the chemicals could be endocrine disruptors, affecting breast and thyroid tissue.

What about cancer? In 2016, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded there was “inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogencity of” PBDEs.

In the same report, though, they suggested PBDEs are “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on mechanistic studies.

In other words, we can’t prove they’re cancerous — but come on, they probably are.

Finally, we have some evidence that really pushes us toward the carcinogenic conclusion, in the form of this study, appearing in JAMA Network Open. It’s a nice bit of epidemiology leveraging the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Researchers measured PBDE levels in blood samples from 1100 people enrolled in NHANES in 2003 and 2004 and linked them to death records collected over the next 20 years or so.

The first thing to note is that the researchers were able to measure PBDEs in the blood samples. They were in there. They were detectable. And they were variable. Dividing the 1100 participants into low, medium, and high PBDE tertiles, you can see a nearly 10-fold difference across the population.

Importantly, not many baseline variables correlated with PBDE levels. People in the highest group were a bit younger but had a fairly similar sex distribution, race, ethnicity, education, income, physical activity, smoking status, and body mass index.

This is not a randomized trial, of course — but at least based on these data, exposure levels do seem fairly random, which is what you would expect from an environmental toxin that percolates up through the food chain. They are often somewhat indiscriminate.

This similarity in baseline characteristics between people with low or high blood levels of PBDE also allows us to make some stronger inferences about the observed outcomes. Let’s take a look at them.

After adjustment for baseline factors, individuals in the highest PBDE group had a 43% higher rate of death from any cause over the follow-up period. This was not enough to achieve statistical significance, but it was close.

But the key finding is deaths due to cancer. After adjustment, cancer deaths occurred four times as frequently among those in the high PBDE group, and that is a statistically significant difference.

To be fair, cancer deaths were rare in this cohort. The vast majority of people did not die of anything during the follow-up period regardless of PBDE level. But the data are strongly suggestive of the carcinogenicity of these chemicals.

I should also point out that the researchers are linking the PBDE level at a single time point to all these future events. If PBDE levels remain relatively stable within an individual over time, that’s fine, but if they tend to vary with intake of different foods for example, this would not be captured and would actually lead to an underestimation of the cancer risk.

The researchers also didn’t have granular enough data to determine the type of cancer, but they do show that rates are similar between men and women, which might point away from the more sex-specific cancer etiologies. Clearly, some more work is needed.

Of course, I started this piece by telling you that these chemicals are already pretty much banned in the United States. What are we supposed to do about these findings? Studies have examined the primary ongoing sources of PBDE in our environment and it seems like most of our exposure will be coming from the food we eat due to that biomagnification thing: high-fat fish, meat and dairy products, and fish oil supplements. It may be worth some investigation into the relative adulteration of these products with this new old carcinogen.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

These types of stories usually end with a call for regulation — to ban said chemical or substance, or to regulate it — but in this case, that has already happened. This new carcinogen I’m telling you about is actually an old chemical. And it has not been manufactured or legally imported in the US since 2013.

So, why bother? Because in this case, the chemical — or, really, a group of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) — are still around: in our soil, in our food, and in our blood.

PBDEs are a group of compounds that confer flame-retardant properties to plastics, and they were used extensively in the latter part of the 20th century in electronic enclosures, business equipment, and foam cushioning in upholstery.

But there was a problem. They don’t chemically bond to plastics; they are just sort of mixed in, which means they can leach out. They are hydrophobic, meaning they don’t get washed out of soil, and, when ingested or inhaled by humans, they dissolve in our fat stores, making it difficult for our normal excretory systems to excrete them.

PBDEs biomagnify. Small animals can take them up from contaminated soil or water, and those animals are eaten by larger animals, which accumulate higher concentrations of the chemicals. This bioaccumulation increases as you move up the food web until you get to an apex predator — like you and me.

This is true of lots of chemicals, of course. The concern arises when these chemicals are toxic. To date, the toxicity data for PBDEs were pretty limited. There were some animal studies where rats were exposed to extremely high doses and they developed liver lesions — but I am always very wary of extrapolating high-dose rat toxicity studies to humans. There was also some suggestion that the chemicals could be endocrine disruptors, affecting breast and thyroid tissue.

What about cancer? In 2016, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded there was “inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogencity of” PBDEs.

In the same report, though, they suggested PBDEs are “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on mechanistic studies.

In other words, we can’t prove they’re cancerous — but come on, they probably are.

Finally, we have some evidence that really pushes us toward the carcinogenic conclusion, in the form of this study, appearing in JAMA Network Open. It’s a nice bit of epidemiology leveraging the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Researchers measured PBDE levels in blood samples from 1100 people enrolled in NHANES in 2003 and 2004 and linked them to death records collected over the next 20 years or so.

The first thing to note is that the researchers were able to measure PBDEs in the blood samples. They were in there. They were detectable. And they were variable. Dividing the 1100 participants into low, medium, and high PBDE tertiles, you can see a nearly 10-fold difference across the population.

Importantly, not many baseline variables correlated with PBDE levels. People in the highest group were a bit younger but had a fairly similar sex distribution, race, ethnicity, education, income, physical activity, smoking status, and body mass index.

This is not a randomized trial, of course — but at least based on these data, exposure levels do seem fairly random, which is what you would expect from an environmental toxin that percolates up through the food chain. They are often somewhat indiscriminate.

This similarity in baseline characteristics between people with low or high blood levels of PBDE also allows us to make some stronger inferences about the observed outcomes. Let’s take a look at them.

After adjustment for baseline factors, individuals in the highest PBDE group had a 43% higher rate of death from any cause over the follow-up period. This was not enough to achieve statistical significance, but it was close.

But the key finding is deaths due to cancer. After adjustment, cancer deaths occurred four times as frequently among those in the high PBDE group, and that is a statistically significant difference.

To be fair, cancer deaths were rare in this cohort. The vast majority of people did not die of anything during the follow-up period regardless of PBDE level. But the data are strongly suggestive of the carcinogenicity of these chemicals.

I should also point out that the researchers are linking the PBDE level at a single time point to all these future events. If PBDE levels remain relatively stable within an individual over time, that’s fine, but if they tend to vary with intake of different foods for example, this would not be captured and would actually lead to an underestimation of the cancer risk.

The researchers also didn’t have granular enough data to determine the type of cancer, but they do show that rates are similar between men and women, which might point away from the more sex-specific cancer etiologies. Clearly, some more work is needed.

Of course, I started this piece by telling you that these chemicals are already pretty much banned in the United States. What are we supposed to do about these findings? Studies have examined the primary ongoing sources of PBDE in our environment and it seems like most of our exposure will be coming from the food we eat due to that biomagnification thing: high-fat fish, meat and dairy products, and fish oil supplements. It may be worth some investigation into the relative adulteration of these products with this new old carcinogen.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

These types of stories usually end with a call for regulation — to ban said chemical or substance, or to regulate it — but in this case, that has already happened. This new carcinogen I’m telling you about is actually an old chemical. And it has not been manufactured or legally imported in the US since 2013.

So, why bother? Because in this case, the chemical — or, really, a group of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) — are still around: in our soil, in our food, and in our blood.

PBDEs are a group of compounds that confer flame-retardant properties to plastics, and they were used extensively in the latter part of the 20th century in electronic enclosures, business equipment, and foam cushioning in upholstery.

But there was a problem. They don’t chemically bond to plastics; they are just sort of mixed in, which means they can leach out. They are hydrophobic, meaning they don’t get washed out of soil, and, when ingested or inhaled by humans, they dissolve in our fat stores, making it difficult for our normal excretory systems to excrete them.

PBDEs biomagnify. Small animals can take them up from contaminated soil or water, and those animals are eaten by larger animals, which accumulate higher concentrations of the chemicals. This bioaccumulation increases as you move up the food web until you get to an apex predator — like you and me.

This is true of lots of chemicals, of course. The concern arises when these chemicals are toxic. To date, the toxicity data for PBDEs were pretty limited. There were some animal studies where rats were exposed to extremely high doses and they developed liver lesions — but I am always very wary of extrapolating high-dose rat toxicity studies to humans. There was also some suggestion that the chemicals could be endocrine disruptors, affecting breast and thyroid tissue.

What about cancer? In 2016, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded there was “inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogencity of” PBDEs.

In the same report, though, they suggested PBDEs are “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on mechanistic studies.

In other words, we can’t prove they’re cancerous — but come on, they probably are.

Finally, we have some evidence that really pushes us toward the carcinogenic conclusion, in the form of this study, appearing in JAMA Network Open. It’s a nice bit of epidemiology leveraging the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Researchers measured PBDE levels in blood samples from 1100 people enrolled in NHANES in 2003 and 2004 and linked them to death records collected over the next 20 years or so.

The first thing to note is that the researchers were able to measure PBDEs in the blood samples. They were in there. They were detectable. And they were variable. Dividing the 1100 participants into low, medium, and high PBDE tertiles, you can see a nearly 10-fold difference across the population.

Importantly, not many baseline variables correlated with PBDE levels. People in the highest group were a bit younger but had a fairly similar sex distribution, race, ethnicity, education, income, physical activity, smoking status, and body mass index.

This is not a randomized trial, of course — but at least based on these data, exposure levels do seem fairly random, which is what you would expect from an environmental toxin that percolates up through the food chain. They are often somewhat indiscriminate.

This similarity in baseline characteristics between people with low or high blood levels of PBDE also allows us to make some stronger inferences about the observed outcomes. Let’s take a look at them.

After adjustment for baseline factors, individuals in the highest PBDE group had a 43% higher rate of death from any cause over the follow-up period. This was not enough to achieve statistical significance, but it was close.

But the key finding is deaths due to cancer. After adjustment, cancer deaths occurred four times as frequently among those in the high PBDE group, and that is a statistically significant difference.

To be fair, cancer deaths were rare in this cohort. The vast majority of people did not die of anything during the follow-up period regardless of PBDE level. But the data are strongly suggestive of the carcinogenicity of these chemicals.

I should also point out that the researchers are linking the PBDE level at a single time point to all these future events. If PBDE levels remain relatively stable within an individual over time, that’s fine, but if they tend to vary with intake of different foods for example, this would not be captured and would actually lead to an underestimation of the cancer risk.

The researchers also didn’t have granular enough data to determine the type of cancer, but they do show that rates are similar between men and women, which might point away from the more sex-specific cancer etiologies. Clearly, some more work is needed.

Of course, I started this piece by telling you that these chemicals are already pretty much banned in the United States. What are we supposed to do about these findings? Studies have examined the primary ongoing sources of PBDE in our environment and it seems like most of our exposure will be coming from the food we eat due to that biomagnification thing: high-fat fish, meat and dairy products, and fish oil supplements. It may be worth some investigation into the relative adulteration of these products with this new old carcinogen.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When Does a Disease Become Its Own Specialty?

Once upon a time, treating multiple sclerosis (MS) was easy — steroids.

Then, in the 1990s, came Betaseron, then Avonex, then Copaxone. Suddenly we had three options to choose from, though overall roughly similar in efficacy (yeah, I’m leaving Novantrone out; it’s a niche drug). Treatment required some decision making, though not a huge amount. I usually laid out the different schedules and side effect to patients and let them decide.

MS treatment was uncomplicated enough that I knew family doctors who treated MS patients on their own, and I can’t say I could have done any better. If you’ve got a clear MRI, then prescribe Betaseron and hope.

Then came Rebif, then Tysabri, and then pretty much an explosion of new drugs which hasn’t slowed down. Next up are the BTK agents. An embarrassment of riches, though for patients, their families, and neurologists, a very welcome one.

But as more drugs come out, with different mechanisms of action and monitoring requirements, the treatment of MS becomes more complicated, slowly moving from the realm of a general neurologist to an MS subspecialist.

At some point it raises the question of when does a disease become its own specialty? Perhaps this is a bit of hyperbole — I’m pretty sure I’ll be seeing MS patients for a long time to come — but it’s a valid point. Especially as further research may subdivide MS treatment by genetics and other breakdowns.

Alzheimer’s disease may follow a similar (albeit very welcome) trajectory. While nothing really game-changing has come out in the 20 years, the number of new drugs and different mechanisms of action in development is large. Granted, not all of them will work, but hopefully some will. At some point it may come down to treating patients with a cocktail of drugs with separate ways of managing the disease, with guidance based on genetic or clinical profiles.

And that’s a good thing, but it may, again, move the disease from the province of general neurologists to subspecialists. Maybe that would be a good, maybe not. Probably will depend on the patient, their families, and other factors.

Of course, I may be overthinking this. The number of drugs we have for MS is nothing compared with the available treatments we have for hypertension, yet it’s certainly well within the capabilities of most internists to treat without referring to a cardiologist or nephrologist.

Perhaps the new drugs won’t make a difference except in a handful of cases. As new drugs come out we also move on from the old ones, dropping them from our mental armamentarium except in rare cases. When was the last time you prescribed Betaseron?

These drugs are very welcome, and very needed. I will be happy if we can beat back some of the diseases neurologist see, regardless of whom the patients and up seeing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Once upon a time, treating multiple sclerosis (MS) was easy — steroids.

Then, in the 1990s, came Betaseron, then Avonex, then Copaxone. Suddenly we had three options to choose from, though overall roughly similar in efficacy (yeah, I’m leaving Novantrone out; it’s a niche drug). Treatment required some decision making, though not a huge amount. I usually laid out the different schedules and side effect to patients and let them decide.

MS treatment was uncomplicated enough that I knew family doctors who treated MS patients on their own, and I can’t say I could have done any better. If you’ve got a clear MRI, then prescribe Betaseron and hope.

Then came Rebif, then Tysabri, and then pretty much an explosion of new drugs which hasn’t slowed down. Next up are the BTK agents. An embarrassment of riches, though for patients, their families, and neurologists, a very welcome one.

But as more drugs come out, with different mechanisms of action and monitoring requirements, the treatment of MS becomes more complicated, slowly moving from the realm of a general neurologist to an MS subspecialist.

At some point it raises the question of when does a disease become its own specialty? Perhaps this is a bit of hyperbole — I’m pretty sure I’ll be seeing MS patients for a long time to come — but it’s a valid point. Especially as further research may subdivide MS treatment by genetics and other breakdowns.

Alzheimer’s disease may follow a similar (albeit very welcome) trajectory. While nothing really game-changing has come out in the 20 years, the number of new drugs and different mechanisms of action in development is large. Granted, not all of them will work, but hopefully some will. At some point it may come down to treating patients with a cocktail of drugs with separate ways of managing the disease, with guidance based on genetic or clinical profiles.

And that’s a good thing, but it may, again, move the disease from the province of general neurologists to subspecialists. Maybe that would be a good, maybe not. Probably will depend on the patient, their families, and other factors.

Of course, I may be overthinking this. The number of drugs we have for MS is nothing compared with the available treatments we have for hypertension, yet it’s certainly well within the capabilities of most internists to treat without referring to a cardiologist or nephrologist.

Perhaps the new drugs won’t make a difference except in a handful of cases. As new drugs come out we also move on from the old ones, dropping them from our mental armamentarium except in rare cases. When was the last time you prescribed Betaseron?

These drugs are very welcome, and very needed. I will be happy if we can beat back some of the diseases neurologist see, regardless of whom the patients and up seeing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Once upon a time, treating multiple sclerosis (MS) was easy — steroids.

Then, in the 1990s, came Betaseron, then Avonex, then Copaxone. Suddenly we had three options to choose from, though overall roughly similar in efficacy (yeah, I’m leaving Novantrone out; it’s a niche drug). Treatment required some decision making, though not a huge amount. I usually laid out the different schedules and side effect to patients and let them decide.

MS treatment was uncomplicated enough that I knew family doctors who treated MS patients on their own, and I can’t say I could have done any better. If you’ve got a clear MRI, then prescribe Betaseron and hope.

Then came Rebif, then Tysabri, and then pretty much an explosion of new drugs which hasn’t slowed down. Next up are the BTK agents. An embarrassment of riches, though for patients, their families, and neurologists, a very welcome one.

But as more drugs come out, with different mechanisms of action and monitoring requirements, the treatment of MS becomes more complicated, slowly moving from the realm of a general neurologist to an MS subspecialist.

At some point it raises the question of when does a disease become its own specialty? Perhaps this is a bit of hyperbole — I’m pretty sure I’ll be seeing MS patients for a long time to come — but it’s a valid point. Especially as further research may subdivide MS treatment by genetics and other breakdowns.

Alzheimer’s disease may follow a similar (albeit very welcome) trajectory. While nothing really game-changing has come out in the 20 years, the number of new drugs and different mechanisms of action in development is large. Granted, not all of them will work, but hopefully some will. At some point it may come down to treating patients with a cocktail of drugs with separate ways of managing the disease, with guidance based on genetic or clinical profiles.

And that’s a good thing, but it may, again, move the disease from the province of general neurologists to subspecialists. Maybe that would be a good, maybe not. Probably will depend on the patient, their families, and other factors.

Of course, I may be overthinking this. The number of drugs we have for MS is nothing compared with the available treatments we have for hypertension, yet it’s certainly well within the capabilities of most internists to treat without referring to a cardiologist or nephrologist.

Perhaps the new drugs won’t make a difference except in a handful of cases. As new drugs come out we also move on from the old ones, dropping them from our mental armamentarium except in rare cases. When was the last time you prescribed Betaseron?

These drugs are very welcome, and very needed. I will be happy if we can beat back some of the diseases neurologist see, regardless of whom the patients and up seeing.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Congratulations to AGA’s New Leaders

Each January, the AGA Nominating Committee meets to complete a very important task — namely, selection of new members of AGA’s Governing Board, pending approval by the membership.

Having served on this committee in the past, I can attest to how challenging a task it is to select these leaders from such a talented and committed pool of candidates, each of whom have served the organization in numerous impactful roles over the course of many years.

This year’s recently announced additions to the Governing Board, who will assume their roles this summer, include Dr. Byron Cryer (incoming Vice President), Dr. Shahnaz Sultan (Clinical Research Councillor), and Dr. Jonathan Rosenberg (Practice Councillor). I have had the pleasure of working with each of them over the years from my very early days at AGA and am confident that AGA will continue to thrive under their leadership. Please join me in congratulating Byron, Shahnaz, and Jonathan on their new roles!

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we highlight a phase 3 RCT from NEJM demonstrating the efficacy of seladelpar, an alternative to ursodeoxycholic acid in patients with PBC with refractory pruritus. From the CGH Practice Management section, Dr. Michelle Kim (Cleveland Clinic) and colleagues provide helpful tips on how to optimize EHR use in GI practice, including by incorporating novel tools based on AI, natural language processing, and speech recognition. In our April Member Spotlight, we are excited to feature gastroenterologist and stand-up comedienne Dr. Shida Haghighat of UCLA, who shares her passion for addressing health disparities and highlights how humor helped her cope with the demands of medical training. We hope you enjoy these, and all the stories included in our April issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Each January, the AGA Nominating Committee meets to complete a very important task — namely, selection of new members of AGA’s Governing Board, pending approval by the membership.

Having served on this committee in the past, I can attest to how challenging a task it is to select these leaders from such a talented and committed pool of candidates, each of whom have served the organization in numerous impactful roles over the course of many years.

This year’s recently announced additions to the Governing Board, who will assume their roles this summer, include Dr. Byron Cryer (incoming Vice President), Dr. Shahnaz Sultan (Clinical Research Councillor), and Dr. Jonathan Rosenberg (Practice Councillor). I have had the pleasure of working with each of them over the years from my very early days at AGA and am confident that AGA will continue to thrive under their leadership. Please join me in congratulating Byron, Shahnaz, and Jonathan on their new roles!

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we highlight a phase 3 RCT from NEJM demonstrating the efficacy of seladelpar, an alternative to ursodeoxycholic acid in patients with PBC with refractory pruritus. From the CGH Practice Management section, Dr. Michelle Kim (Cleveland Clinic) and colleagues provide helpful tips on how to optimize EHR use in GI practice, including by incorporating novel tools based on AI, natural language processing, and speech recognition. In our April Member Spotlight, we are excited to feature gastroenterologist and stand-up comedienne Dr. Shida Haghighat of UCLA, who shares her passion for addressing health disparities and highlights how humor helped her cope with the demands of medical training. We hope you enjoy these, and all the stories included in our April issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Each January, the AGA Nominating Committee meets to complete a very important task — namely, selection of new members of AGA’s Governing Board, pending approval by the membership.

Having served on this committee in the past, I can attest to how challenging a task it is to select these leaders from such a talented and committed pool of candidates, each of whom have served the organization in numerous impactful roles over the course of many years.

This year’s recently announced additions to the Governing Board, who will assume their roles this summer, include Dr. Byron Cryer (incoming Vice President), Dr. Shahnaz Sultan (Clinical Research Councillor), and Dr. Jonathan Rosenberg (Practice Councillor). I have had the pleasure of working with each of them over the years from my very early days at AGA and am confident that AGA will continue to thrive under their leadership. Please join me in congratulating Byron, Shahnaz, and Jonathan on their new roles!

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we highlight a phase 3 RCT from NEJM demonstrating the efficacy of seladelpar, an alternative to ursodeoxycholic acid in patients with PBC with refractory pruritus. From the CGH Practice Management section, Dr. Michelle Kim (Cleveland Clinic) and colleagues provide helpful tips on how to optimize EHR use in GI practice, including by incorporating novel tools based on AI, natural language processing, and speech recognition. In our April Member Spotlight, we are excited to feature gastroenterologist and stand-up comedienne Dr. Shida Haghighat of UCLA, who shares her passion for addressing health disparities and highlights how humor helped her cope with the demands of medical training. We hope you enjoy these, and all the stories included in our April issue.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Ultrasound and Its Role In Diagnosing and Managing Endometriosis

Introduction: Imaging for Endometriosis — A Necessary Prerequisite

While the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis remains laparoscopy, it is now recognized that thorough evaluation via ultrasound offers an acceptable, less expensive, and less invasive alternative. It is especially useful for the diagnosis of deep infiltrative disease, which penetrates more than 5 mm into the peritoneum, ovarian endometrioma, and when anatomic distortion occurs, such as to the path of the ureter.

Besides establishing the diagnosis, ultrasound imaging has become, along with MRI, the most important aid for proper preoperative planning. Not only does imaging provide the surgeon and patient with knowledge regarding the extent of the upcoming procedure, but it also allows the minimally invasive gynecologic (MIG) surgeon to involve colleagues, such as colorectal surgeons or urologists. For example, deep infiltrative endometriosis penetrating into the bowel mucosa will require a discoid or segmental bowel resection.

While many endometriosis experts rely on MRI, many MIG surgeons are dependent on ultrasound. I would not consider taking a patient with signs and symptoms suggestive of endometriosis to surgery without 2D/3D transvaginal ultrasound. If the patient possesses a uterus, a saline-infused sonogram is performed to potentially diagnose adenomyosis.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Professor Caterina Exacoustos MD, PhD, associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata,” to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to discuss “Ultrasound and Its Role in the Diagnosis of and Management of Endometriosis, Including DIE.”

Prof. Exacoustos’ main areas of interest are endometriosis and benign diseases including uterine pathology and infertility. Her extensive body of work comprises over 120 scientific publications and numerous book chapters both in English and in Italian.

Prof. Exacoustos continues to be one of the most well respected lecturers speaking about ultrasound throughout the world.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest to report.

Ultrasound and Its Role In Diagnosing and Managing Endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately 10%-20% of premenopausal women worldwide. It is the leading cause of chronic pelvic pain, is often associated with infertility, and has a significant impact on quality of life. Although the natural history of endometriosis remains unknown, emerging evidence suggests that the pathophysiological steps of initiation and development of endometriosis must occur earlier in the lifespan. Most notably, the onset of endometriosis-associated pain symptoms is often reported during adolescence and young adulthood.1

While many patients with endometriosis are referred with dysmenorrhea at a young age, at age ≤ 25 years,2 symptoms are often highly underestimated and considered to be normal and transient.3,4 Clinical and pelvic exams are often negative in young women, and delays in endometriosis diagnosis are well known.

The presentation of primary dysmenorrhea with no anatomical cause embodies the paradigm that dysmenorrhea in adolescents is most often an insignificant disorder. This perspective is probably a root cause of delayed endometriosis diagnosis in young patients. However, another issue behind delayed diagnosis is the reluctance of the physician to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy — historically the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis — for seemingly common symptoms such as dysmenorrhea in young patients.

Today we know that there are typical aspects of ultrasound imaging that identify endometriosis in the pelvis, and notably, the 2022 European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) endometriosis guideline5 recognizes imaging (ultrasound or MRI) as the standard for endometriosis diagnosis without requiring laparoscopic or histological confirmation.

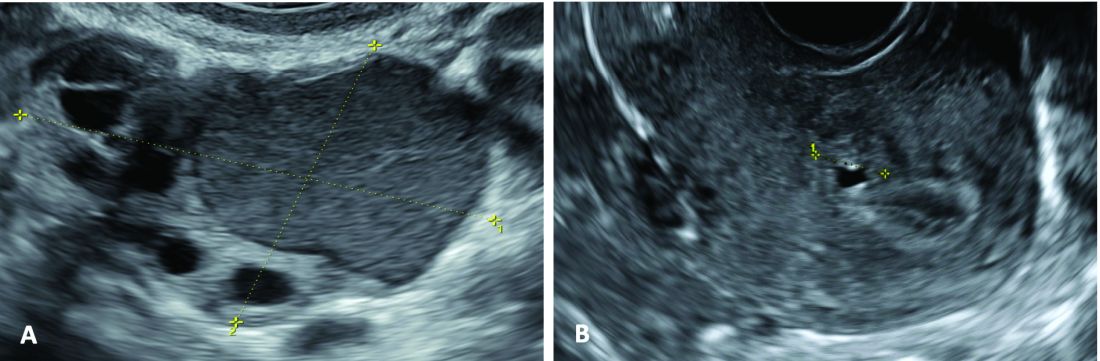

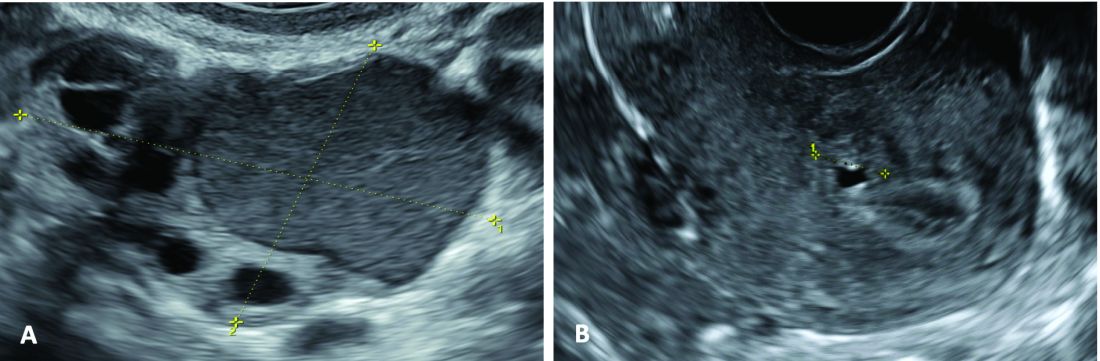

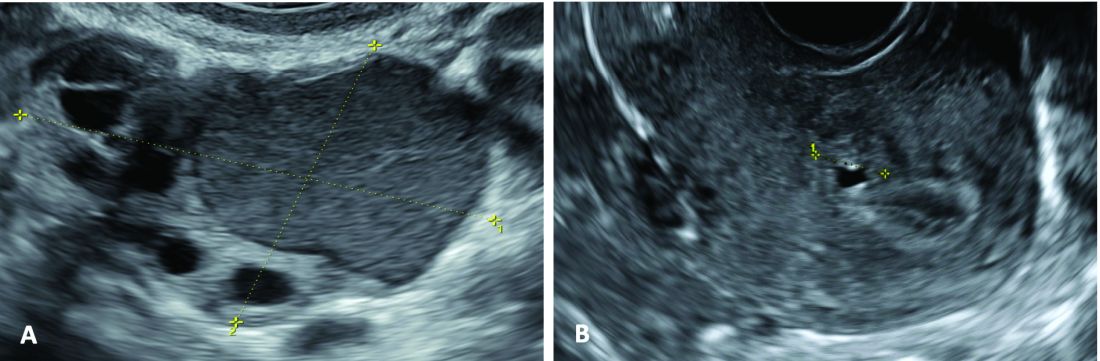

An early and noninvasive method of diagnosis aids in timely diagnosis and provides for the timely initiation of medical management to improve quality of life and prevent progression of disease (Figure 1).

(A. Transvaginal ultrasound appearance of a small ovarian endometrioma in a 16-year-old girl. Note the unilocular cyst with ground glass echogenicity surrounded by multifollicular ovarian tissue. B. Ultrasound image of a retroverted uterus of an 18-year-old girl with focal adenomyosis of the posterior wall. Note the round cystic anechoic areas in the inner myometrium or junctional zone. The small intra-myometrial cyst is surrounded by a hyperechoic ring).

Indeed, the typical appearance of endometriotic pelvic lesions on transvaginal sonography, such as endometriomas and rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) — as well as adenomyosis – can be medically treated without histologic confirmation .

When surgery is advisable, ultrasound findings also play a valuable role in presurgical staging, planning, and counseling for patients of all ages. Determining the extent and location of DIE preoperatively, for instance, facilitates the engagement of the appropriate surgical specialists so that multiple surgeries can be avoided. It also enables patients to be optimally informed before surgery of possible outcomes and complications.

Moreover, in the context of infertility, ultrasound can be a valuable tool for understanding uterine pathology and assessing for adenomyosis so that affected patients may be treated surgically or medically before turning to assisted reproductive technology.

Uniformity, Standardization in the Sonographic Assessment

In Europe, as in the United States, transvaginal sonography (TVS) is the first-line imaging tool for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. In Europe, many ob.gyns. perform ultrasound themselves, as do treating surgeons. When diagnostic findings are negative but clinical suspicion is high, MRI is often utilized. Laparoscopy may then be considered in patients with negative imaging results.

Efforts to standardize terms, definitions, measurements, and sonographic features of different types of endometriosis have been made to make it easier for physicians to share data and communicate with each other. A lack of uniformity has contributed to variability in the reported diagnostic accuracy of TVS.

About 10 years ago, in one such effort, we assessed the accuracy of TVS for DIE by comparing TVS results with laparoscopic/histologic findings, and developed an ultrasound mapping system to accurately record the location, size and depth of lesions visualized by TVS. The accuracy of TVS ranged from 76% for the diagnosis of vaginal endometriosis to 97% for the diagnosis of bladder lesions and posterior cul-de-sac obliteration. Accuracy was 93% and 91% for detecting ureteral involvement (right and left); 87% for uterosacral ligament endometriotic lesions; and 87% for parametrial involvement.6

Shortly after, with a focus on DIE, expert sonographers and physician-sonographers from across Europe — as well as some experts from Australia, Japan, Brazil, Chile, and the United States (Y. Osuga from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School) — came together to agree on a uniform approach to the sonographic evaluation for suspected endometriosis and a standardization of terminology.

The consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group details four steps for examining women with suspected DIE: 1) Evaluation of the uterus and adnexa, 2) evaluation of transvaginal sonographic “soft markers” (ie. site-specific tenderness and ovarian mobility), 3) assessment of the status of the posterior cul-de-sac using real-time ultrasound-based “sliding sign,” and 4) assessment for DIE nodules in the anterior and posterior compartments.7

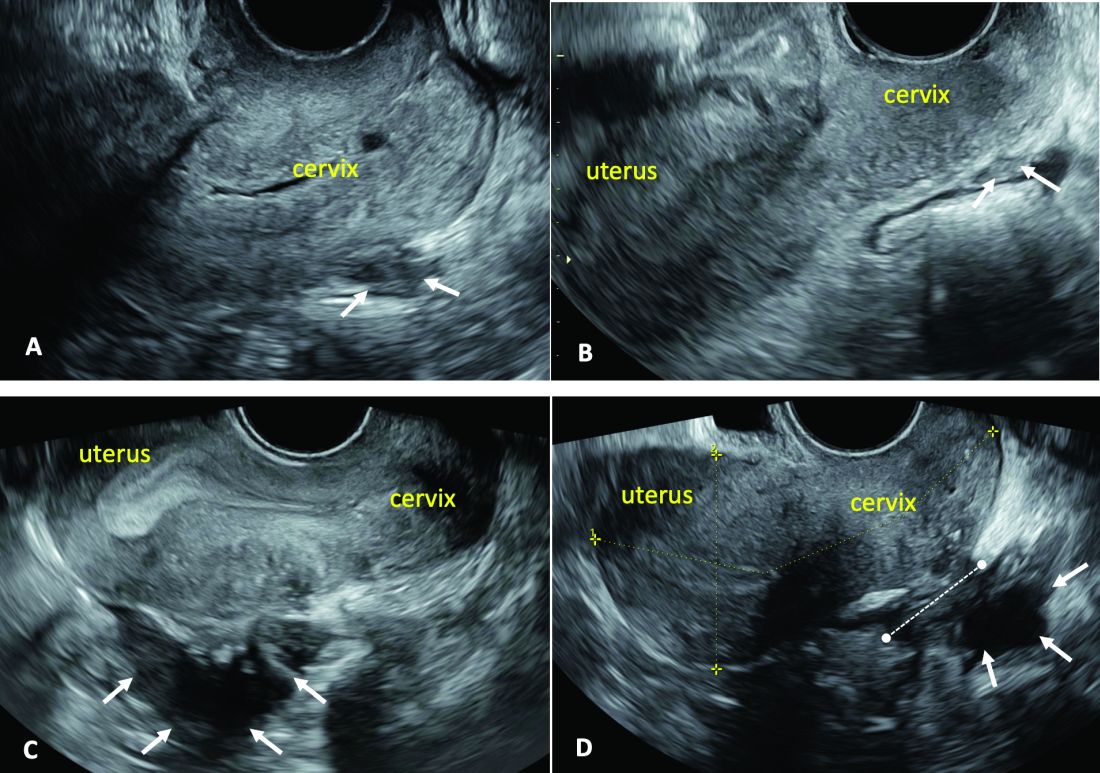

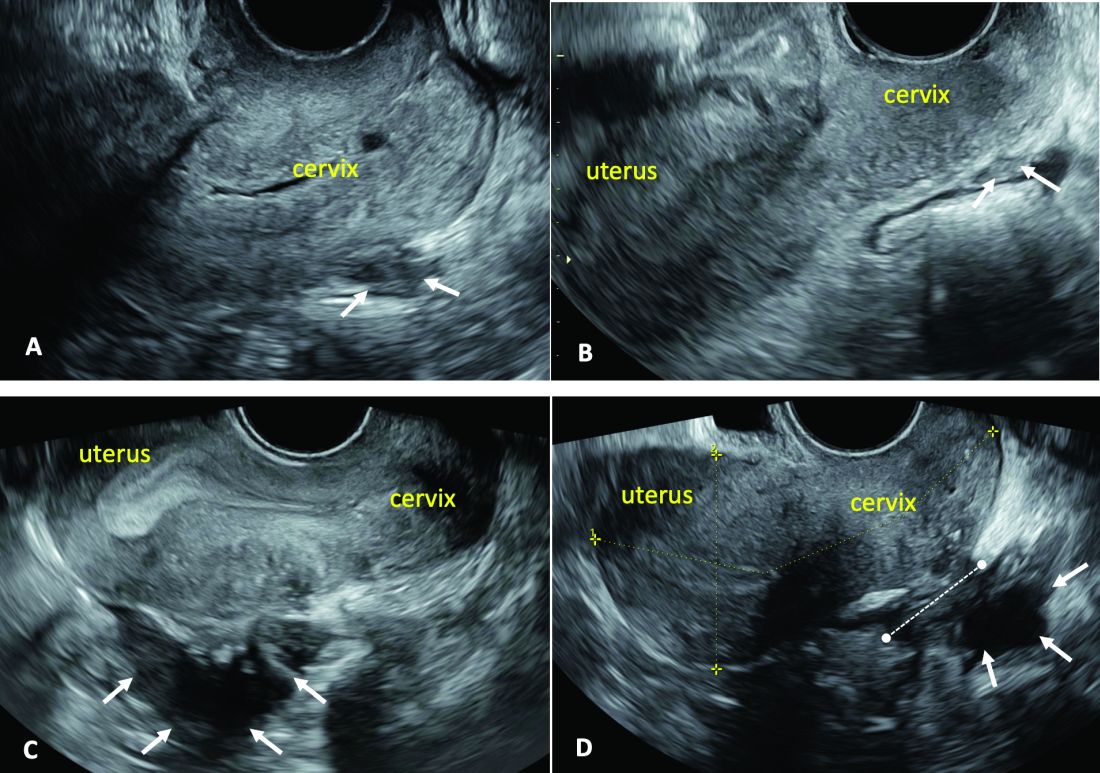

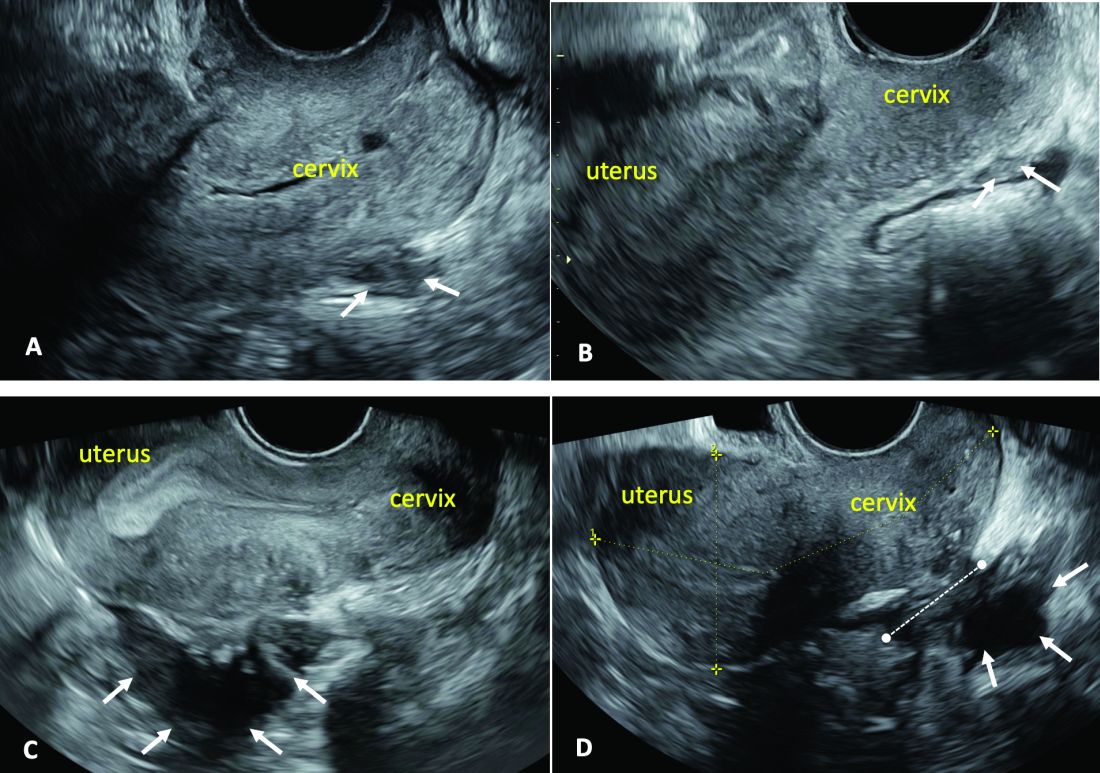

Our paper describing a mapping system and the IDEA paper describe how to detect deep endometriosis in the pelvis by utilizing an ultrasound view of normal anatomy and pelvic organ structure to provide landmarks for accurately defining the site of DIE lesions (Figure 2).

(A. Ultrasound appearance of a small DIE lesion of the retrocervical area [white arrows], which involved the torus uterinum and the right uterosacral ligament [USL]. The lesion appears as hypoechoic tissue with irregular margins caused by the fibrosis induced by the DIE. B. TVS appearance of small nodules of DIE of the left USL. Note the small retrocervical DIE lesion [white arrows], which appears hypoechoic due to the infiltration of the hyperechoic USL. C) Ultrasound appearance of a DIE nodule of the recto-sigmoid wall. Note the hypoechoic thickening of the muscular layers of the bowel wall attached to the corpus of the uterus and the adenomyosis of the posterior wall. The retrocervical area is free. D. TVS appearance of nodules of DIE of the lower rectal wall. Note the hypoechoic lesion [white arrows] of the rectum is attached to a retrocervical DIE fibrosis of the torus and USL [white dotted line]).

So-called rectovaginal endometriosis can be well assessed, for instance, since the involvement of the rectum, sigmoid colon, vaginal wall, rectovaginal septum, and posterior cul-de-sac uterosacral ligament can be seen by ultrasound as a single structure, making the location, size, and depth of any lesions discernible.

Again, this evaluation of the extent of disease is important for presurgical assessment so the surgeon can organize the right team and time of surgery and so the patient can be counseled on the advantages and possible complications of the treatment.

Notably, an accurate ultrasound description of pelvic endometriosis is helpful for accurate classification of disease. Endometriosis classification systems such as that of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL)8 and the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM),9 as well as the #Enzian surgical description system,10 have been adapted to cover findings from ultrasound as well as MRI imaging.

A Systematic Evaluation

In keeping with the IDEA consensus opinion and based on our years of experience at the University of Rome, I advise that patients with typical pain symptoms of endometriosis or infertility undergo an accurate sonographic assessment of the pelvis with particular evaluation not only of the uterus and ovaries but of all pelvic retroperitoneal spaces.

The TVS examination should start with a slightly filled bladder, which permits a better evaluation of the bladder walls and the presence of endometriotic nodules. These nodules appear as hyperechoic linear or spherical lesions bulging toward the lumen and involving the serosa, muscularis, or (sub)mucosa of the bladder.

Then, an accurate evaluation of the uterus in 2D and 3D permits the diagnosis of adenomyosis. 3D sonographic evaluation of the myometrium and of the junctional zone are important; alteration and infiltration of the junctional zone and the presence of small adenomyotic cysts in the inner or outer myometrium are direct, specific signs of adenomyosis and should be ruled out in patients with dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, and pregnancy complications.

Endometriomas of the ovaries can be easily detected as having the typical appearance of a cyst with ground glass content. Adhesions of the ovaries and the uterus also should be evaluated with a dynamic ultrasound approach that utilizes the sliding sign and mobilization by palpation of the organs during the TVS scan.

Finally, the posterior and lateral retroperitoneal compartments should be carefully evaluated, with symptoms guiding the TVS examination whenever possible. Deep endometriotic nodules of the rectum appear as hypoechoic lesions or linear or nodular retroperitoneal thickening with irregular borders, penetrating into the intestinal wall and distorting its normal structure. In young patients, it seems very important to assess for small lesions below the peritoneum between the vagina and rectum, and in the parametria and around the ureter and nerves — lesions that, notably, would not be seen by diagnostic laparoscopy.

The Evaluation of Young Patients

In adolescent and young patients, endometriosis and adenomyosis are often present with small lesions and shallow tissue invasion, making a very careful and experienced approach to ultrasound essential for detection. Endometriomas are often of small diameter, and DIE is not always easily diagnosed because retroperitoneal lesions are similarly very small.

In a series of 270 adolescents (ages 12-20) who were referred to our outpatient gynecologic ultrasound unit over a 5-year period for various indications, at least one ultrasound feature of endometriosis was observed in 13.3%. In those with dysmenorrhea, the detection of endometriosis increased to 21%. Endometrioma was the most common type of endometriosis we found in the study, but DIE and adenomyosis were found in 4%-11%.

Although endometriotic lesions typically are small in young patients, they are often associated with severe pain symptoms, including chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, and dyschezia, all of which can have a serious effect on the quality of life of these young women. These symptoms keep them away from school during menstruation, away from sports, and cause painful intercourse and infertility. In young patients, an accurate TVS can provide a lot of information, and the ability to detect retroperitoneal endometriotic lesions and adenomyosis is probably better than with purely diagnostic laparoscopy, which would evaluate only superficial lesions.

TVS or, when needed, transrectal ultrasound, can enable adequate treatment and follow-up of the disease and its symptoms. There are no guidelines recommending adequate follow-up times to evaluate the effectiveness of medical therapy in patients with ultrasound signs of endometriosis. (Likewise, there are no indications for follow-up in patients with severe dysmenorrhea without ultrasound signs of endometriosis.) Certainly, our studies suggest careful evaluation over time of young patients with severe dysmenorrhea by serial ultrasound scans. With such follow-up, disease progress can be monitored and the medical or surgical treatment approach modified if needed.

The diagnosis of endometriosis at a young age has significant benefits not only in avoiding or reducing progression of the disease, but also in improving quality of life and aiding women in their desire for pregnancy.

Dr. Exacoustos is associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata.” She has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Zondervan KT et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-56.

2. Greene R et al. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9.

3. Chapron C et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:S7-12.

4. Randhawa AE et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34:643-8.

5. Becker CM et al. Hum Reprod Open. 2022(2):hoac009.

6. Exacoustos C et al. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:143-9. 7. Guerriero S et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):318-32.

8. Abrao MS et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1941-50.9. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817-21. 10. Keckstein J et al. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1165-75.

11. Martire FG et al. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(5):1049-57.

Introduction: Imaging for Endometriosis — A Necessary Prerequisite

While the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis remains laparoscopy, it is now recognized that thorough evaluation via ultrasound offers an acceptable, less expensive, and less invasive alternative. It is especially useful for the diagnosis of deep infiltrative disease, which penetrates more than 5 mm into the peritoneum, ovarian endometrioma, and when anatomic distortion occurs, such as to the path of the ureter.

Besides establishing the diagnosis, ultrasound imaging has become, along with MRI, the most important aid for proper preoperative planning. Not only does imaging provide the surgeon and patient with knowledge regarding the extent of the upcoming procedure, but it also allows the minimally invasive gynecologic (MIG) surgeon to involve colleagues, such as colorectal surgeons or urologists. For example, deep infiltrative endometriosis penetrating into the bowel mucosa will require a discoid or segmental bowel resection.

While many endometriosis experts rely on MRI, many MIG surgeons are dependent on ultrasound. I would not consider taking a patient with signs and symptoms suggestive of endometriosis to surgery without 2D/3D transvaginal ultrasound. If the patient possesses a uterus, a saline-infused sonogram is performed to potentially diagnose adenomyosis.

It is a pleasure and honor to welcome Professor Caterina Exacoustos MD, PhD, associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Rome “Tor Vergata,” to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery to discuss “Ultrasound and Its Role in the Diagnosis of and Management of Endometriosis, Including DIE.”

Prof. Exacoustos’ main areas of interest are endometriosis and benign diseases including uterine pathology and infertility. Her extensive body of work comprises over 120 scientific publications and numerous book chapters both in English and in Italian.

Prof. Exacoustos continues to be one of the most well respected lecturers speaking about ultrasound throughout the world.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest to report.

Ultrasound and Its Role In Diagnosing and Managing Endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately 10%-20% of premenopausal women worldwide. It is the leading cause of chronic pelvic pain, is often associated with infertility, and has a significant impact on quality of life. Although the natural history of endometriosis remains unknown, emerging evidence suggests that the pathophysiological steps of initiation and development of endometriosis must occur earlier in the lifespan. Most notably, the onset of endometriosis-associated pain symptoms is often reported during adolescence and young adulthood.1

While many patients with endometriosis are referred with dysmenorrhea at a young age, at age ≤ 25 years,2 symptoms are often highly underestimated and considered to be normal and transient.3,4 Clinical and pelvic exams are often negative in young women, and delays in endometriosis diagnosis are well known.

The presentation of primary dysmenorrhea with no anatomical cause embodies the paradigm that dysmenorrhea in adolescents is most often an insignificant disorder. This perspective is probably a root cause of delayed endometriosis diagnosis in young patients. However, another issue behind delayed diagnosis is the reluctance of the physician to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy — historically the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis — for seemingly common symptoms such as dysmenorrhea in young patients.

Today we know that there are typical aspects of ultrasound imaging that identify endometriosis in the pelvis, and notably, the 2022 European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) endometriosis guideline5 recognizes imaging (ultrasound or MRI) as the standard for endometriosis diagnosis without requiring laparoscopic or histological confirmation.

An early and noninvasive method of diagnosis aids in timely diagnosis and provides for the timely initiation of medical management to improve quality of life and prevent progression of disease (Figure 1).

(A. Transvaginal ultrasound appearance of a small ovarian endometrioma in a 16-year-old girl. Note the unilocular cyst with ground glass echogenicity surrounded by multifollicular ovarian tissue. B. Ultrasound image of a retroverted uterus of an 18-year-old girl with focal adenomyosis of the posterior wall. Note the round cystic anechoic areas in the inner myometrium or junctional zone. The small intra-myometrial cyst is surrounded by a hyperechoic ring).

Indeed, the typical appearance of endometriotic pelvic lesions on transvaginal sonography, such as endometriomas and rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) — as well as adenomyosis – can be medically treated without histologic confirmation .

When surgery is advisable, ultrasound findings also play a valuable role in presurgical staging, planning, and counseling for patients of all ages. Determining the extent and location of DIE preoperatively, for instance, facilitates the engagement of the appropriate surgical specialists so that multiple surgeries can be avoided. It also enables patients to be optimally informed before surgery of possible outcomes and complications.

Moreover, in the context of infertility, ultrasound can be a valuable tool for understanding uterine pathology and assessing for adenomyosis so that affected patients may be treated surgically or medically before turning to assisted reproductive technology.

Uniformity, Standardization in the Sonographic Assessment

In Europe, as in the United States, transvaginal sonography (TVS) is the first-line imaging tool for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. In Europe, many ob.gyns. perform ultrasound themselves, as do treating surgeons. When diagnostic findings are negative but clinical suspicion is high, MRI is often utilized. Laparoscopy may then be considered in patients with negative imaging results.

Efforts to standardize terms, definitions, measurements, and sonographic features of different types of endometriosis have been made to make it easier for physicians to share data and communicate with each other. A lack of uniformity has contributed to variability in the reported diagnostic accuracy of TVS.

About 10 years ago, in one such effort, we assessed the accuracy of TVS for DIE by comparing TVS results with laparoscopic/histologic findings, and developed an ultrasound mapping system to accurately record the location, size and depth of lesions visualized by TVS. The accuracy of TVS ranged from 76% for the diagnosis of vaginal endometriosis to 97% for the diagnosis of bladder lesions and posterior cul-de-sac obliteration. Accuracy was 93% and 91% for detecting ureteral involvement (right and left); 87% for uterosacral ligament endometriotic lesions; and 87% for parametrial involvement.6

Shortly after, with a focus on DIE, expert sonographers and physician-sonographers from across Europe — as well as some experts from Australia, Japan, Brazil, Chile, and the United States (Y. Osuga from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School) — came together to agree on a uniform approach to the sonographic evaluation for suspected endometriosis and a standardization of terminology.

The consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group details four steps for examining women with suspected DIE: 1) Evaluation of the uterus and adnexa, 2) evaluation of transvaginal sonographic “soft markers” (ie. site-specific tenderness and ovarian mobility), 3) assessment of the status of the posterior cul-de-sac using real-time ultrasound-based “sliding sign,” and 4) assessment for DIE nodules in the anterior and posterior compartments.7

Our paper describing a mapping system and the IDEA paper describe how to detect deep endometriosis in the pelvis by utilizing an ultrasound view of normal anatomy and pelvic organ structure to provide landmarks for accurately defining the site of DIE lesions (Figure 2).

(A. Ultrasound appearance of a small DIE lesion of the retrocervical area [white arrows], which involved the torus uterinum and the right uterosacral ligament [USL]. The lesion appears as hypoechoic tissue with irregular margins caused by the fibrosis induced by the DIE. B. TVS appearance of small nodules of DIE of the left USL. Note the small retrocervical DIE lesion [white arrows], which appears hypoechoic due to the infiltration of the hyperechoic USL. C) Ultrasound appearance of a DIE nodule of the recto-sigmoid wall. Note the hypoechoic thickening of the muscular layers of the bowel wall attached to the corpus of the uterus and the adenomyosis of the posterior wall. The retrocervical area is free. D. TVS appearance of nodules of DIE of the lower rectal wall. Note the hypoechoic lesion [white arrows] of the rectum is attached to a retrocervical DIE fibrosis of the torus and USL [white dotted line]).

So-called rectovaginal endometriosis can be well assessed, for instance, since the involvement of the rectum, sigmoid colon, vaginal wall, rectovaginal septum, and posterior cul-de-sac uterosacral ligament can be seen by ultrasound as a single structure, making the location, size, and depth of any lesions discernible.

Again, this evaluation of the extent of disease is important for presurgical assessment so the surgeon can organize the right team and time of surgery and so the patient can be counseled on the advantages and possible complications of the treatment.

Notably, an accurate ultrasound description of pelvic endometriosis is helpful for accurate classification of disease. Endometriosis classification systems such as that of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL)8 and the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM),9 as well as the #Enzian surgical description system,10 have been adapted to cover findings from ultrasound as well as MRI imaging.

A Systematic Evaluation

In keeping with the IDEA consensus opinion and based on our years of experience at the University of Rome, I advise that patients with typical pain symptoms of endometriosis or infertility undergo an accurate sonographic assessment of the pelvis with particular evaluation not only of the uterus and ovaries but of all pelvic retroperitoneal spaces.

The TVS examination should start with a slightly filled bladder, which permits a better evaluation of the bladder walls and the presence of endometriotic nodules. These nodules appear as hyperechoic linear or spherical lesions bulging toward the lumen and involving the serosa, muscularis, or (sub)mucosa of the bladder.

Then, an accurate evaluation of the uterus in 2D and 3D permits the diagnosis of adenomyosis. 3D sonographic evaluation of the myometrium and of the junctional zone are important; alteration and infiltration of the junctional zone and the presence of small adenomyotic cysts in the inner or outer myometrium are direct, specific signs of adenomyosis and should be ruled out in patients with dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, and pregnancy complications.

Endometriomas of the ovaries can be easily detected as having the typical appearance of a cyst with ground glass content. Adhesions of the ovaries and the uterus also should be evaluated with a dynamic ultrasound approach that utilizes the sliding sign and mobilization by palpation of the organs during the TVS scan.

Finally, the posterior and lateral retroperitoneal compartments should be carefully evaluated, with symptoms guiding the TVS examination whenever possible. Deep endometriotic nodules of the rectum appear as hypoechoic lesions or linear or nodular retroperitoneal thickening with irregular borders, penetrating into the intestinal wall and distorting its normal structure. In young patients, it seems very important to assess for small lesions below the peritoneum between the vagina and rectum, and in the parametria and around the ureter and nerves — lesions that, notably, would not be seen by diagnostic laparoscopy.

The Evaluation of Young Patients