User login

A creative diversion

Do you have a creative diversion – a hobby for lack of a better word? One frequently hears of physicians who have creative skills not directly related to their professional careers. Furniture-building surgeons, fly-tying orthopedists, pediatrician poets, painting dermatologists ... I have even heard unsubstantiated claims that the traits that encourage individuals to become physicians make it more likely that they will have creative skills. Another one of those left brain/right brain things that probably doesn’t hold water.

If you do have a hobby or have the seed of a creative impulse you think could blossom into a hobby, I bet you wish that you could have an unlimited amount of time to invest in that activity. I am going to argue that this is another example of a situation in which you should be careful what you wish for.

When I was 9 or 10 years old, I bought a small carving of a sandpiper in a gift shop on Cape Cod. I still have it with its chipped bill and yellowed paper label on its driftwood base. That little bird triggered my interest in carving, and with gaps sometimes measured in decades I have been a self-taught bird carver. Some are attempts at realism with burned in feathers that takes weeks to complete. Others are free form painted whimsically, and are created in a few hours. They aren’t for sale, but to keep my inventory in check I distribute them as birthday and hostess gifts.

Ten years ago, after decades of visiting art galleries and grumbling to my wife, “I could do that,” I decided to try my hand at two-dimensional landscape painting. It was a fun challenge, and after a year or 2, I was ready to see what other people thought of my work. The first show that I entered stipulated that all of the entries be for sale. With no intention of parting with my work, I priced mine several orders of magnitude above what I thought they were worth.

One sold, and with that began a 7-year period during which pretty much anything I painted with a maritime theme sold for hundreds of dollars. It was a nice ego trip, but it took me down a dark path in which I began to choose my subjects and style based on what I knew would sell. Creating was no longer something I did for a change of pace. I was now retired, but painting had become my job. I felt burdened by the obligation to paint enough to cover the walls of the restaurant that graciously hung my work.

Luckily, the epiphany that I had sacrificed my creative diversion, which began with that little sandpiper, coincided with the restaurant’s decision to redecorate and the loss of much of my hanging space. I was now free to paint subjects I was interested in, and return to the comfort of carving when I felt the need to create.

If you already have a creative diversion, remember that a large part of its appeal is that it plays counterpoint to your job. Even if you are retired, a hobby provides a change of pace from which we can all benefit.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Do you have a creative diversion – a hobby for lack of a better word? One frequently hears of physicians who have creative skills not directly related to their professional careers. Furniture-building surgeons, fly-tying orthopedists, pediatrician poets, painting dermatologists ... I have even heard unsubstantiated claims that the traits that encourage individuals to become physicians make it more likely that they will have creative skills. Another one of those left brain/right brain things that probably doesn’t hold water.

If you do have a hobby or have the seed of a creative impulse you think could blossom into a hobby, I bet you wish that you could have an unlimited amount of time to invest in that activity. I am going to argue that this is another example of a situation in which you should be careful what you wish for.

When I was 9 or 10 years old, I bought a small carving of a sandpiper in a gift shop on Cape Cod. I still have it with its chipped bill and yellowed paper label on its driftwood base. That little bird triggered my interest in carving, and with gaps sometimes measured in decades I have been a self-taught bird carver. Some are attempts at realism with burned in feathers that takes weeks to complete. Others are free form painted whimsically, and are created in a few hours. They aren’t for sale, but to keep my inventory in check I distribute them as birthday and hostess gifts.

Ten years ago, after decades of visiting art galleries and grumbling to my wife, “I could do that,” I decided to try my hand at two-dimensional landscape painting. It was a fun challenge, and after a year or 2, I was ready to see what other people thought of my work. The first show that I entered stipulated that all of the entries be for sale. With no intention of parting with my work, I priced mine several orders of magnitude above what I thought they were worth.

One sold, and with that began a 7-year period during which pretty much anything I painted with a maritime theme sold for hundreds of dollars. It was a nice ego trip, but it took me down a dark path in which I began to choose my subjects and style based on what I knew would sell. Creating was no longer something I did for a change of pace. I was now retired, but painting had become my job. I felt burdened by the obligation to paint enough to cover the walls of the restaurant that graciously hung my work.

Luckily, the epiphany that I had sacrificed my creative diversion, which began with that little sandpiper, coincided with the restaurant’s decision to redecorate and the loss of much of my hanging space. I was now free to paint subjects I was interested in, and return to the comfort of carving when I felt the need to create.

If you already have a creative diversion, remember that a large part of its appeal is that it plays counterpoint to your job. Even if you are retired, a hobby provides a change of pace from which we can all benefit.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Do you have a creative diversion – a hobby for lack of a better word? One frequently hears of physicians who have creative skills not directly related to their professional careers. Furniture-building surgeons, fly-tying orthopedists, pediatrician poets, painting dermatologists ... I have even heard unsubstantiated claims that the traits that encourage individuals to become physicians make it more likely that they will have creative skills. Another one of those left brain/right brain things that probably doesn’t hold water.

If you do have a hobby or have the seed of a creative impulse you think could blossom into a hobby, I bet you wish that you could have an unlimited amount of time to invest in that activity. I am going to argue that this is another example of a situation in which you should be careful what you wish for.

When I was 9 or 10 years old, I bought a small carving of a sandpiper in a gift shop on Cape Cod. I still have it with its chipped bill and yellowed paper label on its driftwood base. That little bird triggered my interest in carving, and with gaps sometimes measured in decades I have been a self-taught bird carver. Some are attempts at realism with burned in feathers that takes weeks to complete. Others are free form painted whimsically, and are created in a few hours. They aren’t for sale, but to keep my inventory in check I distribute them as birthday and hostess gifts.

Ten years ago, after decades of visiting art galleries and grumbling to my wife, “I could do that,” I decided to try my hand at two-dimensional landscape painting. It was a fun challenge, and after a year or 2, I was ready to see what other people thought of my work. The first show that I entered stipulated that all of the entries be for sale. With no intention of parting with my work, I priced mine several orders of magnitude above what I thought they were worth.

One sold, and with that began a 7-year period during which pretty much anything I painted with a maritime theme sold for hundreds of dollars. It was a nice ego trip, but it took me down a dark path in which I began to choose my subjects and style based on what I knew would sell. Creating was no longer something I did for a change of pace. I was now retired, but painting had become my job. I felt burdened by the obligation to paint enough to cover the walls of the restaurant that graciously hung my work.

Luckily, the epiphany that I had sacrificed my creative diversion, which began with that little sandpiper, coincided with the restaurant’s decision to redecorate and the loss of much of my hanging space. I was now free to paint subjects I was interested in, and return to the comfort of carving when I felt the need to create.

If you already have a creative diversion, remember that a large part of its appeal is that it plays counterpoint to your job. Even if you are retired, a hobby provides a change of pace from which we can all benefit.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Evaluating fever in the first 90 days of life

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

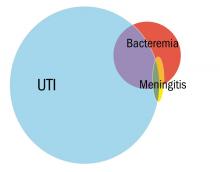

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

DDSEP® 8 Quick Quiz - April 2018 Question 2

Q2. Correct Answer: C

Rationale

The patient presents with acute gallstone pancreatitis. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis and evidence of cholangitis, ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction should be performed. The patients fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant pain are sufficient to make the diagnosis of cholangitis. It is too early in the course of the disease to evaluate for pancreatic necrosis. Typically, triglyceride levels above 1,000 mg/dL are required to induce pancreatitis. Finally, while the patient has cholelithiasis, there is no evidence of cholecystitis. Therefore, a HIDA scan is not warranted.

Reference

1. Behrns KE, Ashley SW, Hunter JG, Carr-Locke D. Early ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis: for whom and when? J Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2008;12(4):629-33.

Q2. Correct Answer: C

Rationale

The patient presents with acute gallstone pancreatitis. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis and evidence of cholangitis, ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction should be performed. The patients fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant pain are sufficient to make the diagnosis of cholangitis. It is too early in the course of the disease to evaluate for pancreatic necrosis. Typically, triglyceride levels above 1,000 mg/dL are required to induce pancreatitis. Finally, while the patient has cholelithiasis, there is no evidence of cholecystitis. Therefore, a HIDA scan is not warranted.

Reference

1. Behrns KE, Ashley SW, Hunter JG, Carr-Locke D. Early ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis: for whom and when? J Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2008;12(4):629-33.

Q2. Correct Answer: C

Rationale

The patient presents with acute gallstone pancreatitis. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis and evidence of cholangitis, ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction should be performed. The patients fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant pain are sufficient to make the diagnosis of cholangitis. It is too early in the course of the disease to evaluate for pancreatic necrosis. Typically, triglyceride levels above 1,000 mg/dL are required to induce pancreatitis. Finally, while the patient has cholelithiasis, there is no evidence of cholecystitis. Therefore, a HIDA scan is not warranted.

Reference

1. Behrns KE, Ashley SW, Hunter JG, Carr-Locke D. Early ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis: for whom and when? J Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2008;12(4):629-33.

A 50-year-old woman with no past medical history presents to the emergency department with the acute onset of severe epigastric pain and vomiting. She is afebrile with a blood pressure of 100/50 mm Hg, and pulse of 110 bpm. Physical exam shows right upper quadrant and epigastric tenderness to palpation without rebound. Labs demonstrate a white blood cell count of 17,000/mm3, hemoglobin of 16 g/dL, creatinine of 1.4 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase of 215 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 190 U/L, a total bilirubin of 2.1 mg/dL, and triglycerides of 492 mg/dL. Right upper quadrant ultrasound reveals gallstones and a 1.2-cm common bile duct. The following day, despite being hydrated aggressively, the patient develops a fever and becomes jaundiced with worsening abdominal pain.

What would be the next step in the patient's management?

DDSEP® 8 Quick Quiz - April 2018 Question 1

Q1. Correct Answer: C

Rationale

The CagA strain of H. pylori has been found to be associated with an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma. CagA-producing H. pylori infection also cause more severe mucosal inflammation and is associated with higher incidences of gastric and duodenal ulcers. A protective effect of CagA+ H. pylori against gastroesophageal reflux disease, reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma has been suggested, as some epidemiologic studies have shown a decreased prevalence of these disorders. Although further studies are needed to verify these relationships, no studies to date have demonstrated an increased risk of esophageal carcinoma associated with H. pylori. CagA-producing H. pylori has not been associated with gastric carcinoid tumor.

References

1. Fallone CA, Barkun AN, Göttke MU, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori genotype with gastroesophageal reflux disease and other upper gastrointestinal diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(3):659-69.

2. Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 2003;125(6):1636-44.

3. Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:329-38.

Q1. Correct Answer: C

Rationale

The CagA strain of H. pylori has been found to be associated with an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma. CagA-producing H. pylori infection also cause more severe mucosal inflammation and is associated with higher incidences of gastric and duodenal ulcers. A protective effect of CagA+ H. pylori against gastroesophageal reflux disease, reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma has been suggested, as some epidemiologic studies have shown a decreased prevalence of these disorders. Although further studies are needed to verify these relationships, no studies to date have demonstrated an increased risk of esophageal carcinoma associated with H. pylori. CagA-producing H. pylori has not been associated with gastric carcinoid tumor.

References

1. Fallone CA, Barkun AN, Göttke MU, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori genotype with gastroesophageal reflux disease and other upper gastrointestinal diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(3):659-69.

2. Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 2003;125(6):1636-44.

3. Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:329-38.

Q1. Correct Answer: C

Rationale

The CagA strain of H. pylori has been found to be associated with an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma. CagA-producing H. pylori infection also cause more severe mucosal inflammation and is associated with higher incidences of gastric and duodenal ulcers. A protective effect of CagA+ H. pylori against gastroesophageal reflux disease, reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma has been suggested, as some epidemiologic studies have shown a decreased prevalence of these disorders. Although further studies are needed to verify these relationships, no studies to date have demonstrated an increased risk of esophageal carcinoma associated with H. pylori. CagA-producing H. pylori has not been associated with gastric carcinoid tumor.

References

1. Fallone CA, Barkun AN, Göttke MU, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori genotype with gastroesophageal reflux disease and other upper gastrointestinal diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(3):659-69.

2. Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 2003;125(6):1636-44.

3. Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:329-38.

The CagA strain of Helicobacter pylori is associated with which of the following?

Hope, hepatology, and social determinants of health

Welcome to the April edition of GI & Hepatology News. April has always been a month where we have a sense of renewal and hope. For those of us living in northern climates, the distinct change in daylight and the melting of the snow (finally) both lifts us from the doldrums of winter darkness. In just over a month, we will gather in Washington for Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). I have seen a preview of AGA plenary sessions (basic science and clinical). They will be terrific. We will hear about advances in areas such as the microbiome, IBD-related inflammatory pathways, new insights into functional bowel disorders, and myriad new therapeutics (both medical and device) for us to share with our patients.

Substantial work is being done to better define an IBD severity index. These metrics are of critical importance for clinical researchers to use as we investigate the efficacy and effectiveness of new IBD drugs. You can also read about incorporating psychological care in the management of chronic diseases – a topic becoming more important as we expand our focus beyond just the biology of disease and into social determinants of health as we continue our transition to value-based reimbursement. Another topic included this month (and to which several DDW sessions are dedicated) is the devastating impact of opiates on our patients.

We have included a number of hepatology articles this month, such as the front-page story on NASH and its relationship with hepatocellular cancer. Pioglitazone benefits NASH patients with and without type 2 diabetes and biomarkers may predict liver transplant failures. There are selected articles about Barrett’s esophagus progression and risk stratification for colorectal cancer.

From Washington, we have received some good news. Please see the AGA commentary on the proposed budget. We were reminded last month about how Federal politics can impact U.S. medicine. With the (very late) reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP), we saw how political dysfunction can impact millions of American family’s lives. Changes in 340-B funding, continued transition from commercial to government payers, a tightening labor market, relentless increases in overhead expenses, all combine to reduce financial margins of both academic and nonacademic health systems. Economic pressures are leading to massive consolidations within the health care delivery system. Vertical integrations now have supplanted horizontal integrations as the industry trend. This situation that will impact many of our independent gastroenterology practices as demand-side management by large national corporations increases.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Welcome to the April edition of GI & Hepatology News. April has always been a month where we have a sense of renewal and hope. For those of us living in northern climates, the distinct change in daylight and the melting of the snow (finally) both lifts us from the doldrums of winter darkness. In just over a month, we will gather in Washington for Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). I have seen a preview of AGA plenary sessions (basic science and clinical). They will be terrific. We will hear about advances in areas such as the microbiome, IBD-related inflammatory pathways, new insights into functional bowel disorders, and myriad new therapeutics (both medical and device) for us to share with our patients.

Substantial work is being done to better define an IBD severity index. These metrics are of critical importance for clinical researchers to use as we investigate the efficacy and effectiveness of new IBD drugs. You can also read about incorporating psychological care in the management of chronic diseases – a topic becoming more important as we expand our focus beyond just the biology of disease and into social determinants of health as we continue our transition to value-based reimbursement. Another topic included this month (and to which several DDW sessions are dedicated) is the devastating impact of opiates on our patients.

We have included a number of hepatology articles this month, such as the front-page story on NASH and its relationship with hepatocellular cancer. Pioglitazone benefits NASH patients with and without type 2 diabetes and biomarkers may predict liver transplant failures. There are selected articles about Barrett’s esophagus progression and risk stratification for colorectal cancer.

From Washington, we have received some good news. Please see the AGA commentary on the proposed budget. We were reminded last month about how Federal politics can impact U.S. medicine. With the (very late) reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP), we saw how political dysfunction can impact millions of American family’s lives. Changes in 340-B funding, continued transition from commercial to government payers, a tightening labor market, relentless increases in overhead expenses, all combine to reduce financial margins of both academic and nonacademic health systems. Economic pressures are leading to massive consolidations within the health care delivery system. Vertical integrations now have supplanted horizontal integrations as the industry trend. This situation that will impact many of our independent gastroenterology practices as demand-side management by large national corporations increases.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Welcome to the April edition of GI & Hepatology News. April has always been a month where we have a sense of renewal and hope. For those of us living in northern climates, the distinct change in daylight and the melting of the snow (finally) both lifts us from the doldrums of winter darkness. In just over a month, we will gather in Washington for Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). I have seen a preview of AGA plenary sessions (basic science and clinical). They will be terrific. We will hear about advances in areas such as the microbiome, IBD-related inflammatory pathways, new insights into functional bowel disorders, and myriad new therapeutics (both medical and device) for us to share with our patients.

Substantial work is being done to better define an IBD severity index. These metrics are of critical importance for clinical researchers to use as we investigate the efficacy and effectiveness of new IBD drugs. You can also read about incorporating psychological care in the management of chronic diseases – a topic becoming more important as we expand our focus beyond just the biology of disease and into social determinants of health as we continue our transition to value-based reimbursement. Another topic included this month (and to which several DDW sessions are dedicated) is the devastating impact of opiates on our patients.

We have included a number of hepatology articles this month, such as the front-page story on NASH and its relationship with hepatocellular cancer. Pioglitazone benefits NASH patients with and without type 2 diabetes and biomarkers may predict liver transplant failures. There are selected articles about Barrett’s esophagus progression and risk stratification for colorectal cancer.

From Washington, we have received some good news. Please see the AGA commentary on the proposed budget. We were reminded last month about how Federal politics can impact U.S. medicine. With the (very late) reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP), we saw how political dysfunction can impact millions of American family’s lives. Changes in 340-B funding, continued transition from commercial to government payers, a tightening labor market, relentless increases in overhead expenses, all combine to reduce financial margins of both academic and nonacademic health systems. Economic pressures are leading to massive consolidations within the health care delivery system. Vertical integrations now have supplanted horizontal integrations as the industry trend. This situation that will impact many of our independent gastroenterology practices as demand-side management by large national corporations increases.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Understanding the new CMS bundle model

Hospitalists have been among the highest-volume participants in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) demonstration model, initiating over 200,000 episodes representing $4.7 billion in spending since the model began.1 On Jan. 9, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced BPCI’s follow-on model, “BPCI Advanced.”2

BPCI launched in October 2013 and sunsets at the end of Q3 2018. BPCI Advanced starts immediately upon conclusion of BPCI (Q4 2018) and is slated to finish at year-end 2023.

CMS intends for the program to qualify as an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM). As BPCI Advanced focuses on episodes of care involving an inpatient stay (It also includes three outpatient episodes.) and the subsequent 90-day recovery period, it represents the first large-scale opportunity for hospitalists to meet criteria for Advanced APM participation. Qualifying for the Advanced APM track of the Quality Payment Program – which involves meeting patient volume or payment thresholds3 – comes with a 5% lump-sum bonus based on Medicare Part B fees and avoids exposure to penalties and reporting requirements of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Key program features

Acute care hospitals and physician groups may initiate episodes under BPCI Advanced, assuming financial risk under the model. Similar to its predecessor, BPCI Advanced assigns a target price based on past claims payments associated with the “episode initiator.”

During the performance period, if the initiator can beat the price in the aggregate for its bundles, it can keep the difference, and if it comes in over the price, it must pay the difference back to Medicare. Medicare discounts the target price by 3%, effectively paying itself that amount. After that, there is no sharing of savings with Medicare, as opposed to the permanent ACO programs, where there is sharing after the ACO meets the minimum savings rate.

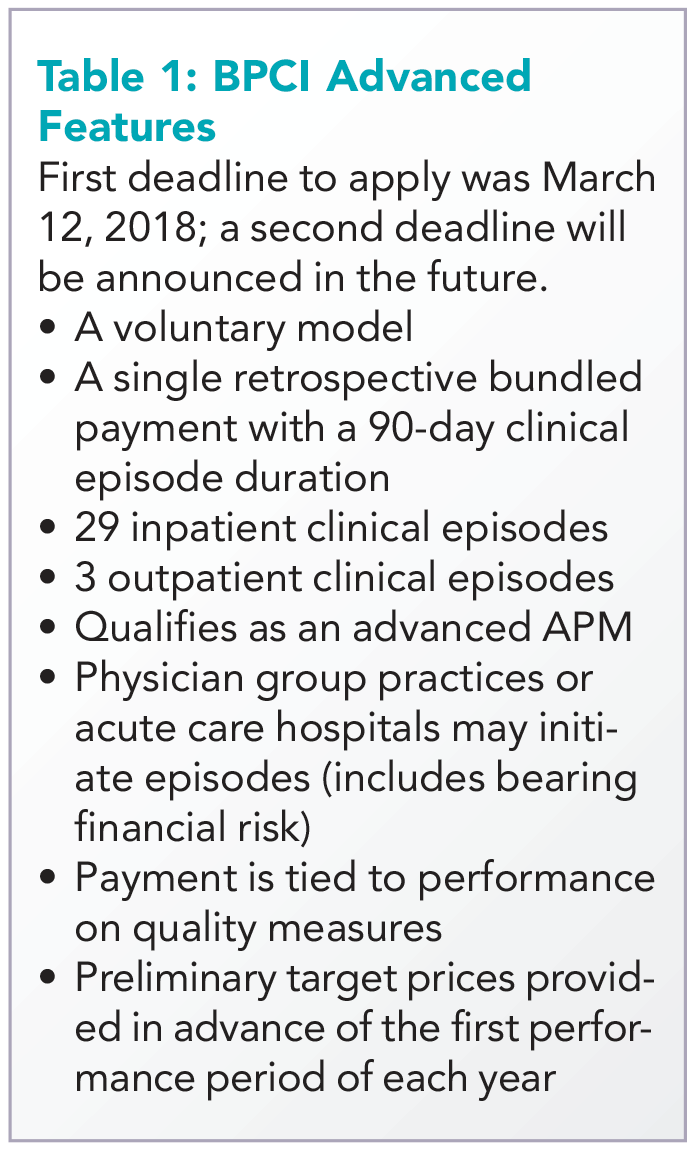

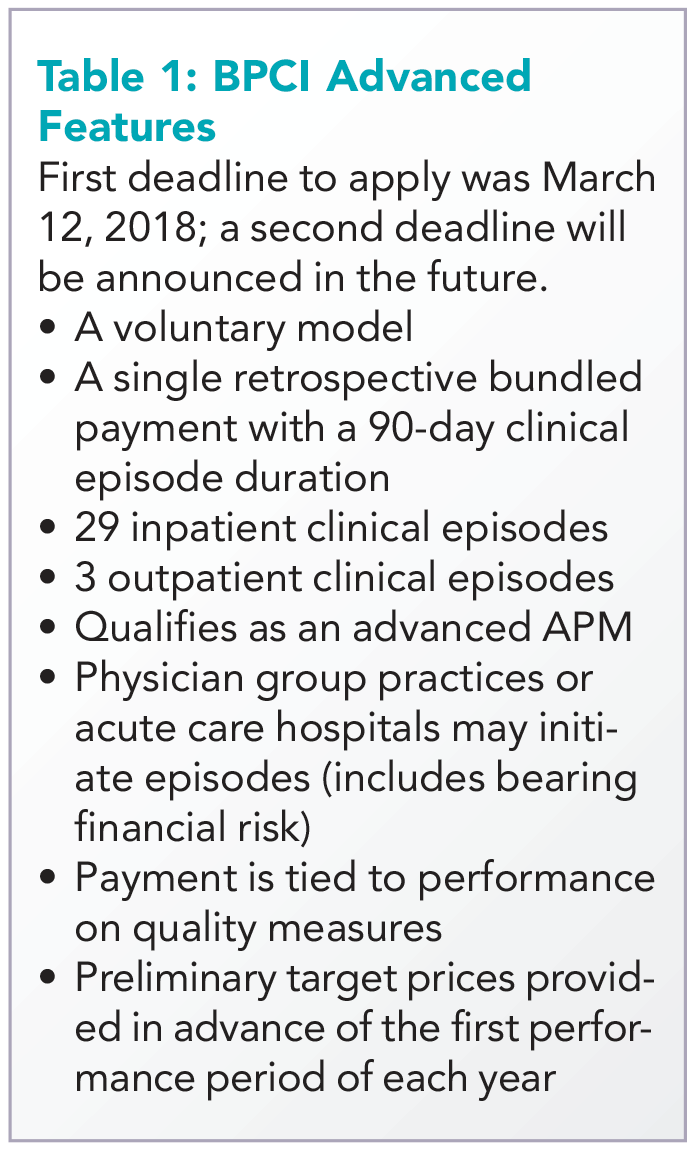

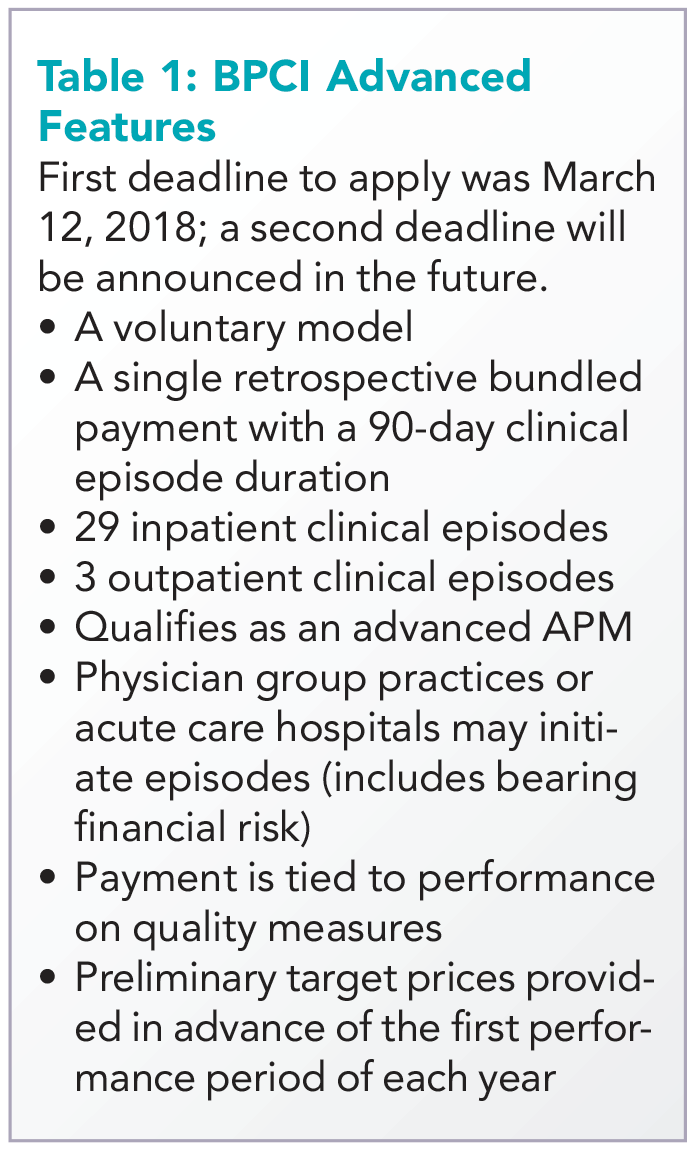

The program allows physician groups and hospital initiators to go it alone or to work with a “convener,” which may share risk and reward with initiators, and may provide software, analytics, networks of high-performing providers like nursing facilities, and knowledge of specific care redesign approaches to enable program success. See Table 1 for a listing of other notable features of BPCI Advanced.

Quality measures

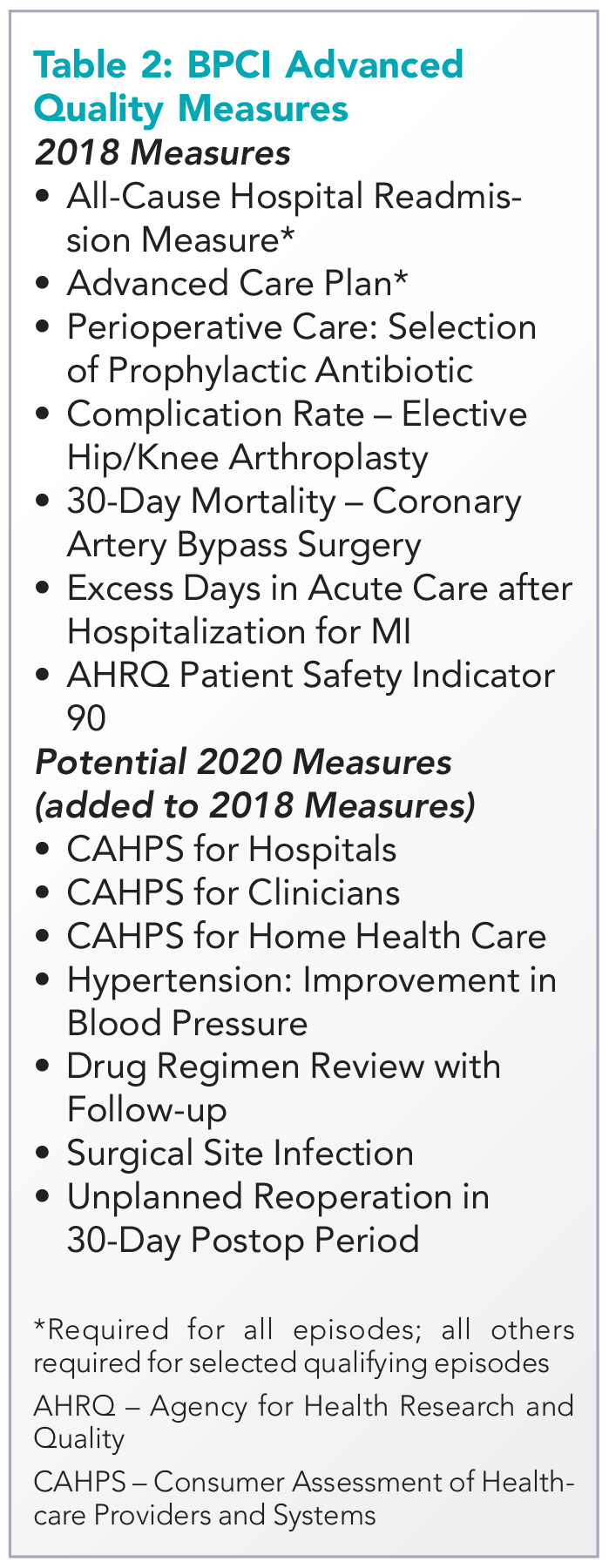

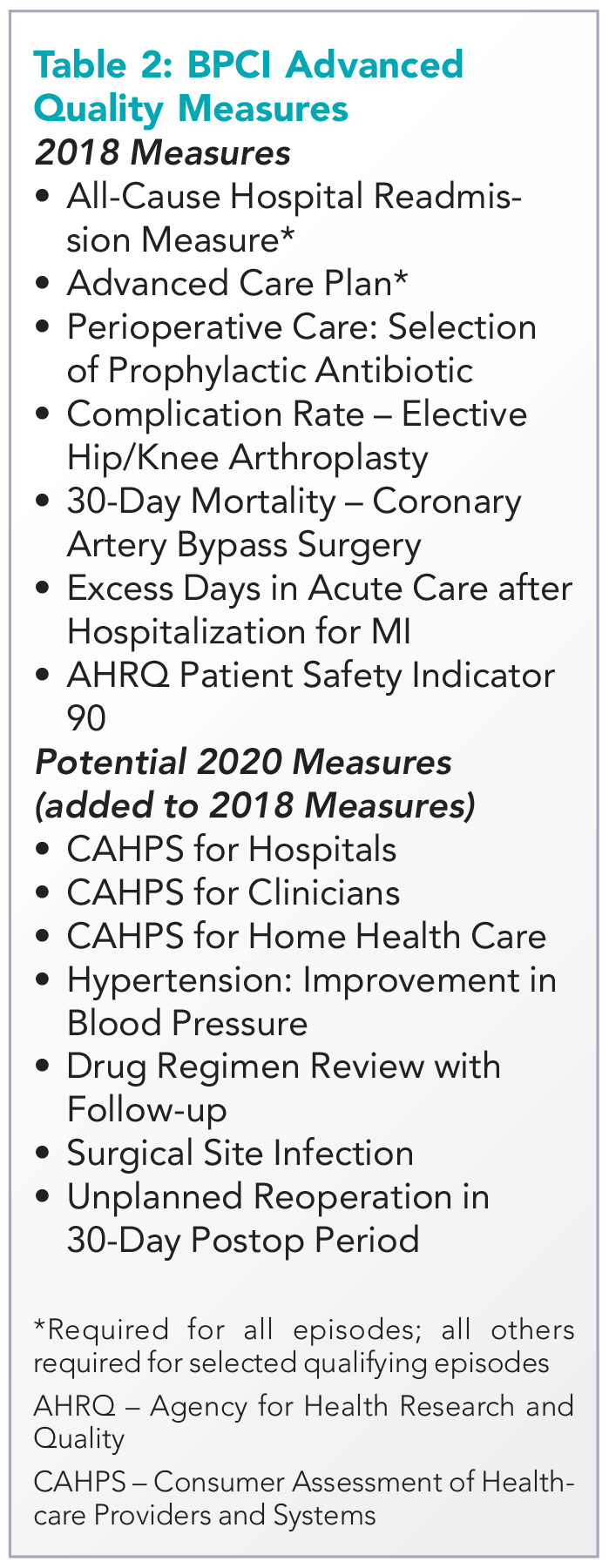

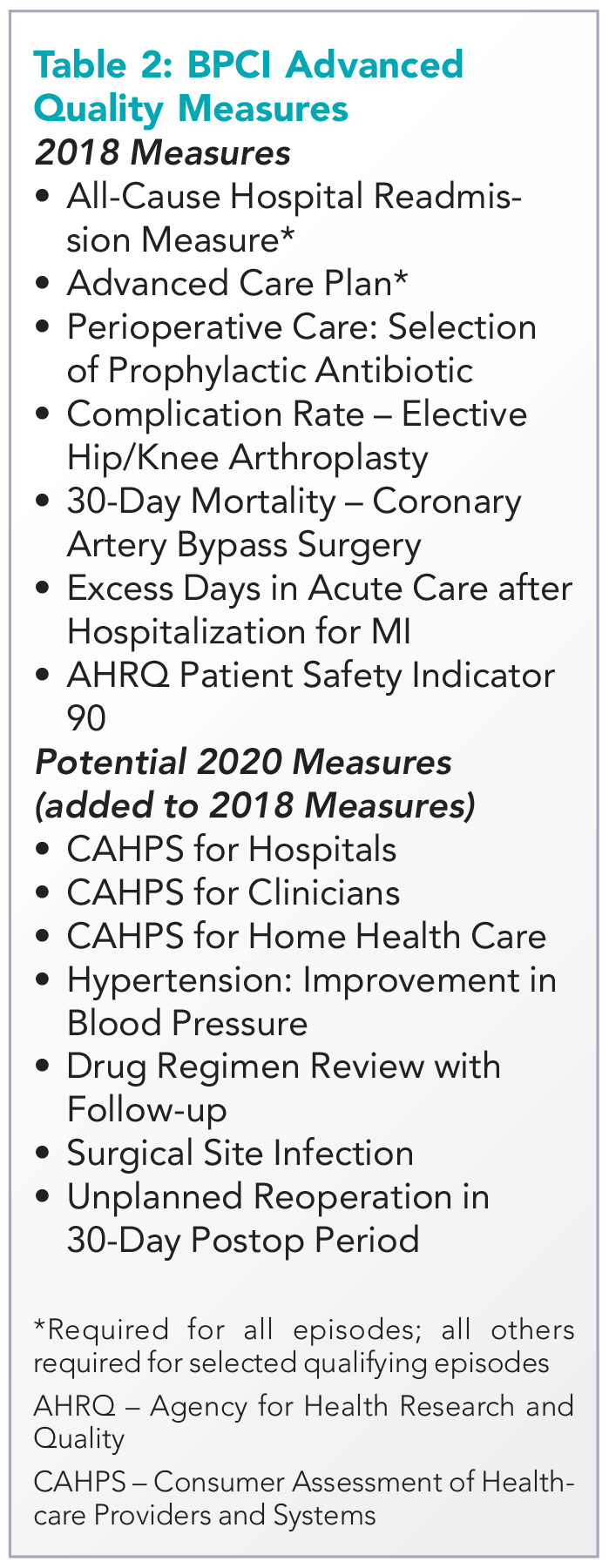

BPCI Advanced qualifies as an Advanced APM in part because payment is tied to performance on a set of quality measures (see Table 2). There are two measures applied to all episodes: all-cause hospital readmissions and advance care plan. These are notable because hospitalists may be especially focused on improvement activities in these areas.

While the advance care plan measure refers to a process reflected by record documentation and is therefore directly under the control of hospitalists, readmissions – and most of the other measures – require a team approach. Because the outcome measures are risk adjusted, accurate and complete clinical documentation is crucial, as it drives how risk is adjusted. Of note, all the 2018 measures, collected directly through claims, will place no additional administrative burden for collection on providers.

Two ways for hospitalists to participate

Hospitalist groups – whether independent or employed – may be episode initiators in BPCI Advanced. In this case, any episodes in which the group participates that carry the name of a member of the hospitalist group in the “Attending Provider” field on the hospital bill claim form to Medicare (and the associated carrier claim) are attributed to that member’s physician group.

For example, if the group has chosen heart failure as an episode in which to participate at the program’s outset, a hospitalization is assigned the heart failure DRG (diagnosis-related group) and a group member is the Attending Provider on the claim form (and submits a claim for the physician services), then the episode is attributed to that group. This means that the group is responsible for payments represented by Medicare Part A and Part B claims (with a few exclusions like trauma and cancer) against the target price for the initial hospitalization and subsequent 90-day period. In practice, hospitalists are rewarded for actions aimed at optimizing location after discharge,4 avoiding readmissions, choosing efficient nursing facilities, and helping patients to maximize functional status.

The other way hospitalists may participate is through an agreement to share in savings with a hospital or physician group episode initiator. This requires hospitalist individuals or groups to enter into a contract with the initiator that meets certain program requirements – for example, report quality measures, engage in care redesign, use certified EHR technology (hospital-based clinicians automatically fulfill this criterion).

If there is broad participation, BPCI Advanced could represent a key milestone for hospitalists, as they seek to be recognized for the value they confer to the system as a whole instead of simply their professional billings. While there are legitimate concerns about the effect MIPS may have on health care value and the complexity of participation in APMs, barring a repeal of the law that created them, hospitalists now have the chance to extend their influence within and outside the hospital’s four walls and be more fairly rewarded for it.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Contact him at [email protected]. Disclosure: The author’s employer, Remedy Partners, is an Awardee Convener for the BPCI initiative and intends to apply as a Convener in BPCI Advanced.

References

1. Based on BPCI awardee convener Remedy Partners claims analysis.

2. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced.

3. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/overview.

4. Whitcomb W. Choosing location after discharge wisely. The-hospitalist.org. 2018 Jan 3. Digital edition. Accessed Jan 13, 2018.

Hospitalists have been among the highest-volume participants in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) demonstration model, initiating over 200,000 episodes representing $4.7 billion in spending since the model began.1 On Jan. 9, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced BPCI’s follow-on model, “BPCI Advanced.”2

BPCI launched in October 2013 and sunsets at the end of Q3 2018. BPCI Advanced starts immediately upon conclusion of BPCI (Q4 2018) and is slated to finish at year-end 2023.

CMS intends for the program to qualify as an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM). As BPCI Advanced focuses on episodes of care involving an inpatient stay (It also includes three outpatient episodes.) and the subsequent 90-day recovery period, it represents the first large-scale opportunity for hospitalists to meet criteria for Advanced APM participation. Qualifying for the Advanced APM track of the Quality Payment Program – which involves meeting patient volume or payment thresholds3 – comes with a 5% lump-sum bonus based on Medicare Part B fees and avoids exposure to penalties and reporting requirements of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Key program features

Acute care hospitals and physician groups may initiate episodes under BPCI Advanced, assuming financial risk under the model. Similar to its predecessor, BPCI Advanced assigns a target price based on past claims payments associated with the “episode initiator.”

During the performance period, if the initiator can beat the price in the aggregate for its bundles, it can keep the difference, and if it comes in over the price, it must pay the difference back to Medicare. Medicare discounts the target price by 3%, effectively paying itself that amount. After that, there is no sharing of savings with Medicare, as opposed to the permanent ACO programs, where there is sharing after the ACO meets the minimum savings rate.

The program allows physician groups and hospital initiators to go it alone or to work with a “convener,” which may share risk and reward with initiators, and may provide software, analytics, networks of high-performing providers like nursing facilities, and knowledge of specific care redesign approaches to enable program success. See Table 1 for a listing of other notable features of BPCI Advanced.

Quality measures

BPCI Advanced qualifies as an Advanced APM in part because payment is tied to performance on a set of quality measures (see Table 2). There are two measures applied to all episodes: all-cause hospital readmissions and advance care plan. These are notable because hospitalists may be especially focused on improvement activities in these areas.

While the advance care plan measure refers to a process reflected by record documentation and is therefore directly under the control of hospitalists, readmissions – and most of the other measures – require a team approach. Because the outcome measures are risk adjusted, accurate and complete clinical documentation is crucial, as it drives how risk is adjusted. Of note, all the 2018 measures, collected directly through claims, will place no additional administrative burden for collection on providers.

Two ways for hospitalists to participate

Hospitalist groups – whether independent or employed – may be episode initiators in BPCI Advanced. In this case, any episodes in which the group participates that carry the name of a member of the hospitalist group in the “Attending Provider” field on the hospital bill claim form to Medicare (and the associated carrier claim) are attributed to that member’s physician group.

For example, if the group has chosen heart failure as an episode in which to participate at the program’s outset, a hospitalization is assigned the heart failure DRG (diagnosis-related group) and a group member is the Attending Provider on the claim form (and submits a claim for the physician services), then the episode is attributed to that group. This means that the group is responsible for payments represented by Medicare Part A and Part B claims (with a few exclusions like trauma and cancer) against the target price for the initial hospitalization and subsequent 90-day period. In practice, hospitalists are rewarded for actions aimed at optimizing location after discharge,4 avoiding readmissions, choosing efficient nursing facilities, and helping patients to maximize functional status.

The other way hospitalists may participate is through an agreement to share in savings with a hospital or physician group episode initiator. This requires hospitalist individuals or groups to enter into a contract with the initiator that meets certain program requirements – for example, report quality measures, engage in care redesign, use certified EHR technology (hospital-based clinicians automatically fulfill this criterion).

If there is broad participation, BPCI Advanced could represent a key milestone for hospitalists, as they seek to be recognized for the value they confer to the system as a whole instead of simply their professional billings. While there are legitimate concerns about the effect MIPS may have on health care value and the complexity of participation in APMs, barring a repeal of the law that created them, hospitalists now have the chance to extend their influence within and outside the hospital’s four walls and be more fairly rewarded for it.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Contact him at [email protected]. Disclosure: The author’s employer, Remedy Partners, is an Awardee Convener for the BPCI initiative and intends to apply as a Convener in BPCI Advanced.

References

1. Based on BPCI awardee convener Remedy Partners claims analysis.

2. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced.

3. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/overview.

4. Whitcomb W. Choosing location after discharge wisely. The-hospitalist.org. 2018 Jan 3. Digital edition. Accessed Jan 13, 2018.

Hospitalists have been among the highest-volume participants in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) demonstration model, initiating over 200,000 episodes representing $4.7 billion in spending since the model began.1 On Jan. 9, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced BPCI’s follow-on model, “BPCI Advanced.”2

BPCI launched in October 2013 and sunsets at the end of Q3 2018. BPCI Advanced starts immediately upon conclusion of BPCI (Q4 2018) and is slated to finish at year-end 2023.

CMS intends for the program to qualify as an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM). As BPCI Advanced focuses on episodes of care involving an inpatient stay (It also includes three outpatient episodes.) and the subsequent 90-day recovery period, it represents the first large-scale opportunity for hospitalists to meet criteria for Advanced APM participation. Qualifying for the Advanced APM track of the Quality Payment Program – which involves meeting patient volume or payment thresholds3 – comes with a 5% lump-sum bonus based on Medicare Part B fees and avoids exposure to penalties and reporting requirements of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Key program features

Acute care hospitals and physician groups may initiate episodes under BPCI Advanced, assuming financial risk under the model. Similar to its predecessor, BPCI Advanced assigns a target price based on past claims payments associated with the “episode initiator.”

During the performance period, if the initiator can beat the price in the aggregate for its bundles, it can keep the difference, and if it comes in over the price, it must pay the difference back to Medicare. Medicare discounts the target price by 3%, effectively paying itself that amount. After that, there is no sharing of savings with Medicare, as opposed to the permanent ACO programs, where there is sharing after the ACO meets the minimum savings rate.

The program allows physician groups and hospital initiators to go it alone or to work with a “convener,” which may share risk and reward with initiators, and may provide software, analytics, networks of high-performing providers like nursing facilities, and knowledge of specific care redesign approaches to enable program success. See Table 1 for a listing of other notable features of BPCI Advanced.

Quality measures

BPCI Advanced qualifies as an Advanced APM in part because payment is tied to performance on a set of quality measures (see Table 2). There are two measures applied to all episodes: all-cause hospital readmissions and advance care plan. These are notable because hospitalists may be especially focused on improvement activities in these areas.

While the advance care plan measure refers to a process reflected by record documentation and is therefore directly under the control of hospitalists, readmissions – and most of the other measures – require a team approach. Because the outcome measures are risk adjusted, accurate and complete clinical documentation is crucial, as it drives how risk is adjusted. Of note, all the 2018 measures, collected directly through claims, will place no additional administrative burden for collection on providers.

Two ways for hospitalists to participate

Hospitalist groups – whether independent or employed – may be episode initiators in BPCI Advanced. In this case, any episodes in which the group participates that carry the name of a member of the hospitalist group in the “Attending Provider” field on the hospital bill claim form to Medicare (and the associated carrier claim) are attributed to that member’s physician group.

For example, if the group has chosen heart failure as an episode in which to participate at the program’s outset, a hospitalization is assigned the heart failure DRG (diagnosis-related group) and a group member is the Attending Provider on the claim form (and submits a claim for the physician services), then the episode is attributed to that group. This means that the group is responsible for payments represented by Medicare Part A and Part B claims (with a few exclusions like trauma and cancer) against the target price for the initial hospitalization and subsequent 90-day period. In practice, hospitalists are rewarded for actions aimed at optimizing location after discharge,4 avoiding readmissions, choosing efficient nursing facilities, and helping patients to maximize functional status.

The other way hospitalists may participate is through an agreement to share in savings with a hospital or physician group episode initiator. This requires hospitalist individuals or groups to enter into a contract with the initiator that meets certain program requirements – for example, report quality measures, engage in care redesign, use certified EHR technology (hospital-based clinicians automatically fulfill this criterion).

If there is broad participation, BPCI Advanced could represent a key milestone for hospitalists, as they seek to be recognized for the value they confer to the system as a whole instead of simply their professional billings. While there are legitimate concerns about the effect MIPS may have on health care value and the complexity of participation in APMs, barring a repeal of the law that created them, hospitalists now have the chance to extend their influence within and outside the hospital’s four walls and be more fairly rewarded for it.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Contact him at [email protected]. Disclosure: The author’s employer, Remedy Partners, is an Awardee Convener for the BPCI initiative and intends to apply as a Convener in BPCI Advanced.

References

1. Based on BPCI awardee convener Remedy Partners claims analysis.

2. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced.

3. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/overview.

4. Whitcomb W. Choosing location after discharge wisely. The-hospitalist.org. 2018 Jan 3. Digital edition. Accessed Jan 13, 2018.

The Right Choice? Mixed feelings about a recent informed consent court decision

On June 20, 2017, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled on a case that may have significant implications for surgical informed consent.

Although the legal complexities of the case might be interesting to some, what got my attention was the question of whether a surgeon can delegate the informed consent discussion with a patient to someone else.

A few weeks later, the patient had a phone conversation with Dr. Tom’s physician assistant (PA) who answered several additional questions Ms. Shinal had about the surgery. Approximately one month later, the patient met with the same PA and had a preoperative history and physical examination and the informed consent form was signed.

About 2 weeks after that, the patient had an open craniotomy with total resection of the tumor. Unfortunately, the procedure was complicated by bleeding that resulted in stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness. Ms. Shinal and her husband sued Dr. Toms for malpractice, and included in the suit was a claim that Dr. Toms failed to obtain informed consent from Ms. Shinal.

At the original trial, the jury was instructed by the judge to consider information given to Ms. Shinal both by Dr. Toms and his PA as included in the informed consent process. The jury found in favor of Dr. Toms and the patient then appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court which upheld the decision. The case was then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which specifically addressed the issue of whether the informed consent discussion must be performed by the surgeon or can be delegated to others.

Several groups, including the American Medical Association, filed briefs in the case supporting Dr. Tom’s claim that the information that is conveyed in the informed consent process is what is important rather than exactly who provides that information to the patient. For many, this case seemed to be relatively straightforward. The surgeon had discussed the operation with the patient, she had agreed, and then in several additional conversations with the surgeon’s PA, the patient’s additional questions had been answered and the patient had willingly signed the informed consent document.

However, in a surprise to many, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision stated that “a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patients’ informed consent. Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.” Based on this finding, the case was sent back to the trial court for a new trial.

Although legal scholars may debate the legal basis of this opinion and the ramifications for future cases, I am more interested in the ethical issues that it raises. Although, in recent decades, I have become increasingly accustomed to the idea of medical care by teams, there is something almost nostalgic about this decision. It suggests to me that at least four of the seven Pennsylvania Supreme Court justices believe that there is something so special about surgical informed consent that it must involve a direct conversation between the patient and the surgeon.

This view seems ever more foreign in an environment in which we increasingly talk about processes of care and systems errors rather than individual relationships and individual responsibility. Although the supremely hierarchical concept of the surgeon as the “captain of the ship” has largely been replaced by the team approach, it is nevertheless true that, in an elective case, the patient would not be in the operating room but for the relationship and trust that the patient has in the surgeon.

As I contemplate this court case, I see how it may add to the challenges of providing surgical care to patients and how it may further the delays to see some surgeons. However, it also reemphasizes for me that informed consent for surgery is less about the information that is transferred to the patient and much more about the relationship in which a patient places his or her trust in the surgeon. The emphasis that this court ruling places on the direct relationship between a surgeon and a patient is a refreshing reminder of the personal responsibility that surgeons have for their patients’ outcomes.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

On June 20, 2017, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled on a case that may have significant implications for surgical informed consent.

Although the legal complexities of the case might be interesting to some, what got my attention was the question of whether a surgeon can delegate the informed consent discussion with a patient to someone else.

A few weeks later, the patient had a phone conversation with Dr. Tom’s physician assistant (PA) who answered several additional questions Ms. Shinal had about the surgery. Approximately one month later, the patient met with the same PA and had a preoperative history and physical examination and the informed consent form was signed.

About 2 weeks after that, the patient had an open craniotomy with total resection of the tumor. Unfortunately, the procedure was complicated by bleeding that resulted in stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness. Ms. Shinal and her husband sued Dr. Toms for malpractice, and included in the suit was a claim that Dr. Toms failed to obtain informed consent from Ms. Shinal.

At the original trial, the jury was instructed by the judge to consider information given to Ms. Shinal both by Dr. Toms and his PA as included in the informed consent process. The jury found in favor of Dr. Toms and the patient then appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court which upheld the decision. The case was then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which specifically addressed the issue of whether the informed consent discussion must be performed by the surgeon or can be delegated to others.

Several groups, including the American Medical Association, filed briefs in the case supporting Dr. Tom’s claim that the information that is conveyed in the informed consent process is what is important rather than exactly who provides that information to the patient. For many, this case seemed to be relatively straightforward. The surgeon had discussed the operation with the patient, she had agreed, and then in several additional conversations with the surgeon’s PA, the patient’s additional questions had been answered and the patient had willingly signed the informed consent document.

However, in a surprise to many, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision stated that “a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patients’ informed consent. Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.” Based on this finding, the case was sent back to the trial court for a new trial.

Although legal scholars may debate the legal basis of this opinion and the ramifications for future cases, I am more interested in the ethical issues that it raises. Although, in recent decades, I have become increasingly accustomed to the idea of medical care by teams, there is something almost nostalgic about this decision. It suggests to me that at least four of the seven Pennsylvania Supreme Court justices believe that there is something so special about surgical informed consent that it must involve a direct conversation between the patient and the surgeon.

This view seems ever more foreign in an environment in which we increasingly talk about processes of care and systems errors rather than individual relationships and individual responsibility. Although the supremely hierarchical concept of the surgeon as the “captain of the ship” has largely been replaced by the team approach, it is nevertheless true that, in an elective case, the patient would not be in the operating room but for the relationship and trust that the patient has in the surgeon.

As I contemplate this court case, I see how it may add to the challenges of providing surgical care to patients and how it may further the delays to see some surgeons. However, it also reemphasizes for me that informed consent for surgery is less about the information that is transferred to the patient and much more about the relationship in which a patient places his or her trust in the surgeon. The emphasis that this court ruling places on the direct relationship between a surgeon and a patient is a refreshing reminder of the personal responsibility that surgeons have for their patients’ outcomes.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

On June 20, 2017, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled on a case that may have significant implications for surgical informed consent.

Although the legal complexities of the case might be interesting to some, what got my attention was the question of whether a surgeon can delegate the informed consent discussion with a patient to someone else.

A few weeks later, the patient had a phone conversation with Dr. Tom’s physician assistant (PA) who answered several additional questions Ms. Shinal had about the surgery. Approximately one month later, the patient met with the same PA and had a preoperative history and physical examination and the informed consent form was signed.

About 2 weeks after that, the patient had an open craniotomy with total resection of the tumor. Unfortunately, the procedure was complicated by bleeding that resulted in stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness. Ms. Shinal and her husband sued Dr. Toms for malpractice, and included in the suit was a claim that Dr. Toms failed to obtain informed consent from Ms. Shinal.

At the original trial, the jury was instructed by the judge to consider information given to Ms. Shinal both by Dr. Toms and his PA as included in the informed consent process. The jury found in favor of Dr. Toms and the patient then appealed to the Pennsylvania Superior Court which upheld the decision. The case was then appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which specifically addressed the issue of whether the informed consent discussion must be performed by the surgeon or can be delegated to others.

Several groups, including the American Medical Association, filed briefs in the case supporting Dr. Tom’s claim that the information that is conveyed in the informed consent process is what is important rather than exactly who provides that information to the patient. For many, this case seemed to be relatively straightforward. The surgeon had discussed the operation with the patient, she had agreed, and then in several additional conversations with the surgeon’s PA, the patient’s additional questions had been answered and the patient had willingly signed the informed consent document.

However, in a surprise to many, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision stated that “a physician may not delegate to others his or her obligation to provide sufficient information in order to obtain a patients’ informed consent. Informed consent requires direct communication between physician and patient and contemplates a back-and-forth, face-to-face exchange, which might include questions that the patient feels the physician must answer personally before the patient feels informed and becomes willing to consent. The duty to obtain the patient’s informed consent belongs solely to the physician.” Based on this finding, the case was sent back to the trial court for a new trial.

Although legal scholars may debate the legal basis of this opinion and the ramifications for future cases, I am more interested in the ethical issues that it raises. Although, in recent decades, I have become increasingly accustomed to the idea of medical care by teams, there is something almost nostalgic about this decision. It suggests to me that at least four of the seven Pennsylvania Supreme Court justices believe that there is something so special about surgical informed consent that it must involve a direct conversation between the patient and the surgeon.

This view seems ever more foreign in an environment in which we increasingly talk about processes of care and systems errors rather than individual relationships and individual responsibility. Although the supremely hierarchical concept of the surgeon as the “captain of the ship” has largely been replaced by the team approach, it is nevertheless true that, in an elective case, the patient would not be in the operating room but for the relationship and trust that the patient has in the surgeon.

As I contemplate this court case, I see how it may add to the challenges of providing surgical care to patients and how it may further the delays to see some surgeons. However, it also reemphasizes for me that informed consent for surgery is less about the information that is transferred to the patient and much more about the relationship in which a patient places his or her trust in the surgeon. The emphasis that this court ruling places on the direct relationship between a surgeon and a patient is a refreshing reminder of the personal responsibility that surgeons have for their patients’ outcomes.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Welcome to Orlando and HM18

Welcome to HM18 and Orlando! This is the annual conference’s first time in Orlando, a city dubbed “the happiest place on earth,” which conjures up magic and curiosity and brings out the kid in everyone. As Walt Disney noted, “Adults are only kids, grown up.” So we hope you have brought your sense of adventure and curiosity, as we have a lot planned for you!

Over the next 3 days, we invite you to network with nearly 5,000 hospitalist colleagues from around the “small world.” Introduce yourself to total strangers and discover you have a lot in common. This conference provides a wonderful opportunity to share best practices and discuss ideas.

Please have fun taking advantage of the wide array of learning opportunities the Annual Conference Committee developed for HM18. We hope the topics will grab your interest and pique your curiosity. We encourage you (and your inner kid) to try on new ideas, attend lectures that catch your eye, and roll up your sleeves to dive into interactive workshops. For extra fun, the committee created catchy Orlando-themed titles for many of the talks. We hope they make you smile!

The Annual Conference Committee members will be wearing large buttons to identify themselves. We welcome any feedback about the meeting. Please take the time to share your thoughts with us, and we are happy to help in any way. The committee members worked hard to create a pre-course day and meeting with something for everyone, knowing there is great diversity under the hospitalist tent. We also strove to make it relevant and timely. The driving force behind the content was “What do practicing hospitalists need and want to know now?”

HM18 contains an abundance of clinical content. Enjoy the 2 days of Clinical Update talks to hear the latest evidence from a diversity of fields. New this year is Updates in Addiction Medicine, given the large opioid crisis that affecting health care. There are 3 days of Rapid Fire talks to answer the clinical questions we all have while caring for patients. The Perioperative/Co-Management track is back with is unique and useful content. We even repeat some of the most popular talks on Tuesday, so you will be able to attend all the “can’t miss” sessions.

New this year is a focus on careers and how to make yours enjoyable and sustainable. Hospital medicine is more than 20 years old, and there are increasing numbers of mid-career hospitalists. The Career Development track offers a series of topics in case you want to spice up your current role, change your schedule, or plan for retirement. Accompanying this are career development workshops that provide practical skills to do just that.

We have also added a new NP/PA track, a palliative care track, and The Great Debate track. Come watch two entertaining speakers have a “smackdown” on a clinical topic. You’ll learn something while laughing.

We’ve also brought back your favorites: practice management, quality, high value care, diagnostic reasoning, academic/research, pediatrics, medical education, and health policy tracks. Don’t forget to check out our interactive workshops. Nearly 150 workshop ideas were submitted, and we are proud to feature 18 of the best.

Of course, you must attend the highly anticipated Updates in Hospital Medicine talk and Plenary Sessions, and be sure to catch the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) Poster Competition. Check out the Exhibit Hall and join a Special Interest Forum! Remember to download the SHM events app, and make sure you get your MOC credit from 34 different lectures.

This conference would not be possible without the tireless effort of SHM staff and leadership, our amazing speakers and faculty, and the committee members. We are excited you are here, and we hope this conference nurtures your curiosity, expands your career, and provides you with valuable educational and networking opportunities.

We sincerely thank you for attending HM18! Enjoy Orlando.

Dr. Finn is an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and course director of HM18.

Welcome to HM18 and Orlando! This is the annual conference’s first time in Orlando, a city dubbed “the happiest place on earth,” which conjures up magic and curiosity and brings out the kid in everyone. As Walt Disney noted, “Adults are only kids, grown up.” So we hope you have brought your sense of adventure and curiosity, as we have a lot planned for you!

Over the next 3 days, we invite you to network with nearly 5,000 hospitalist colleagues from around the “small world.” Introduce yourself to total strangers and discover you have a lot in common. This conference provides a wonderful opportunity to share best practices and discuss ideas.

Please have fun taking advantage of the wide array of learning opportunities the Annual Conference Committee developed for HM18. We hope the topics will grab your interest and pique your curiosity. We encourage you (and your inner kid) to try on new ideas, attend lectures that catch your eye, and roll up your sleeves to dive into interactive workshops. For extra fun, the committee created catchy Orlando-themed titles for many of the talks. We hope they make you smile!

The Annual Conference Committee members will be wearing large buttons to identify themselves. We welcome any feedback about the meeting. Please take the time to share your thoughts with us, and we are happy to help in any way. The committee members worked hard to create a pre-course day and meeting with something for everyone, knowing there is great diversity under the hospitalist tent. We also strove to make it relevant and timely. The driving force behind the content was “What do practicing hospitalists need and want to know now?”

HM18 contains an abundance of clinical content. Enjoy the 2 days of Clinical Update talks to hear the latest evidence from a diversity of fields. New this year is Updates in Addiction Medicine, given the large opioid crisis that affecting health care. There are 3 days of Rapid Fire talks to answer the clinical questions we all have while caring for patients. The Perioperative/Co-Management track is back with is unique and useful content. We even repeat some of the most popular talks on Tuesday, so you will be able to attend all the “can’t miss” sessions.

New this year is a focus on careers and how to make yours enjoyable and sustainable. Hospital medicine is more than 20 years old, and there are increasing numbers of mid-career hospitalists. The Career Development track offers a series of topics in case you want to spice up your current role, change your schedule, or plan for retirement. Accompanying this are career development workshops that provide practical skills to do just that.

We have also added a new NP/PA track, a palliative care track, and The Great Debate track. Come watch two entertaining speakers have a “smackdown” on a clinical topic. You’ll learn something while laughing.

We’ve also brought back your favorites: practice management, quality, high value care, diagnostic reasoning, academic/research, pediatrics, medical education, and health policy tracks. Don’t forget to check out our interactive workshops. Nearly 150 workshop ideas were submitted, and we are proud to feature 18 of the best.

Of course, you must attend the highly anticipated Updates in Hospital Medicine talk and Plenary Sessions, and be sure to catch the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) Poster Competition. Check out the Exhibit Hall and join a Special Interest Forum! Remember to download the SHM events app, and make sure you get your MOC credit from 34 different lectures.

This conference would not be possible without the tireless effort of SHM staff and leadership, our amazing speakers and faculty, and the committee members. We are excited you are here, and we hope this conference nurtures your curiosity, expands your career, and provides you with valuable educational and networking opportunities.

We sincerely thank you for attending HM18! Enjoy Orlando.

Dr. Finn is an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and course director of HM18.

Welcome to HM18 and Orlando! This is the annual conference’s first time in Orlando, a city dubbed “the happiest place on earth,” which conjures up magic and curiosity and brings out the kid in everyone. As Walt Disney noted, “Adults are only kids, grown up.” So we hope you have brought your sense of adventure and curiosity, as we have a lot planned for you!

Over the next 3 days, we invite you to network with nearly 5,000 hospitalist colleagues from around the “small world.” Introduce yourself to total strangers and discover you have a lot in common. This conference provides a wonderful opportunity to share best practices and discuss ideas.