User login

Making a case for patient-reported outcomes in clinical inflammatory bowel disease practice

Patients seek medical care when they perceive a deterioration in their health. Gastroenterologists and health care providers are trained to seek out clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and endoscopic evidence of pathology. Conventional endpoints in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical trials and clinical care may fail to capture the full health status and disease experience from the patient perspective. The Food and Drug Administration has called for the development of coprimary endpoints in research trials to include an objective measure of inflammation in conjunction with patient-reported outcomes (PROs). The objective is to support labeling claims and improve safety and effectiveness in the drug approval process.1,2 There is also growing recognition that high-value care includes management of biologic and psychosocial factors to enable patients with chronic diseases to regain their health. Clinicians might follow suit by incorporating valid, reliable PRO measures to usual IBD care in order better to achieve patient-centered care, inform decision making, and improve the care provided.

What are patient-reported outcomes?

The FDA defines a PRO as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” Two PROs are used to measure various aspects of health including physical, emotional, or social domains. PROs have emerged as tools that may foster a better understanding of the patient’s condition, which may go beyond disease activity or symptoms. In effect, incorporating PROs into clinical practice enables a model of “coproduction” of health care, and may contribute to a more reciprocal patient-provider interaction where the needs of the patient may be more fully understood and incorporated into decision-making that may lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.3,4

There are hundreds of available PROs in gastroenterology,5 ranging from simple (characterizing pain with a basic numeric rating scale) to complex multidomain, multi-item instruments. PROs may cover symptom assessment, health-related quality of life, and adherence to and satisfaction with treatment, and may be generic or disease specific. Numerous PROs have been developed for patients with IBD. Commonly used PROs in IBD include severity scales for pain, defecatory urgency, and bloody stool, and several disease-specific and generic instruments assessing different health-related quality-of-life domains have been used in research studies for patients with IBD.

The current approach to patient-centered care for IBD is limited

IBD is a difficult disease to manage – in part because there is no known biomarker that accurately reflects the full spectrum of disease activity. Numerous indices have been developed to better quantify disease activity and measure response to treatment. Among the most frequently used indices in clinical trials are the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and (for ulcerative colitis [UC]) the Mayo Clinic Score. These endpoints incorporate signs and symptoms, laboratory findings (in the CDAI), and endoscopic assessments. The CDAI is a suboptimal instrument because of a lack of correlation with endoscopic inflammation and potential confounding with concomitant gastrointestinal illnesses, such as irritable bowel syndrome.6 The Mayo Clinic Score is difficult to interpret because of some subjective elements (what is considered a normal number of stools per day?); vagueness (mostly bloody stools more than half the time?); and need for a physician assessment, which often does not correspond with the patient’s perception of their disease.7 From a research perspective, this disconnect can compromise the quality of trial data. Clinically, it can negatively impact patients’ satisfaction and impair the patient-provider relationship.8

To that end, regulatory agencies, scientific bodies, and health care payors are shifting toward a more “patient-centered” approach with an emphasis on PROs. However, although the FDA is incorporating the patient perspective in its trials, measuring meaningful outcomes in day-to-day clinical care is challenging. In the absence of active inflammation, more than 30% of patients with IBD still suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms.9 Furthermore, physicians frequently underestimate the effect of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep on patient health. Likewise, some patients with active small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) may experience few gastrointestinal symptoms but have profound fatigue, weight loss, and impaired quality of life. A focused assessment for disease activity may fail to identify aspects of health most relevant or important to individual patient well-being. There is a need for effective, efficient, and standardized strategies to better understand the concerns of the individual seeking help.

Although there are several PROs that measure disease activity primarily for clinical research trials,10 their prevalence in gastroenterology practices has not been assessed. Most likely, few clinical practices currently integrate standardized PROs in routine patient care. This may be because of several reasons, including lack of awareness of newly developed PROs, administrative burden including time and resources to collect PROs, potentially complex interpretation of results, and perhaps a reluctance among physicians to alter traditional patient interview methods of obtaining information about the health status of their patients. For effective use in clinical care, PROs require simple and relevant interpretation to add value to the clinician’s practice, and must minimally impact clinical flow and resources. The use of Internet-enabled tablets has been shown to be a feasible, efficient, and effective means of PRO assessment in gastroenterology practices, with good levels of patient satisfaction.11

Reaping potential benefits of patient-reported outcomes

The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an initiative developed to investigate and promote implementation of PRO measures among patients with chronic diseases. The collection of PROMIS measures has been shown to be feasible at a tertiary care IBD center, enabling a biopsychosocial model of care.12 Likewise, implementation of PROs in other clinical areas including oncology, orthopedics, and rheumatology has been robust.

In an innovative orthopedic study, PROMIS measures collected and linked to the electronic medical record predicted the likelihood of a clinically meaningful benefit from foot and ankle surgery.13 This facilitated tailored patient-specific preoperative discussions about the expected benefit of surgery. In a study at a rheumatology clinic patients with rheumatoid arthritis were asked to identify their highest priority treatment targets using PROMIS domains (fatigue, pain, depression, social function). The highest priority domain was tracked over time as a patient-centered marker of health, essentially personalizing measures of success for the individual patient.14

PROs have the unique potential to affect multiple levels of health care. At the patient level, PRO data can identify specific concerns, manage expectations of recovery, and tailor treatment decisions to personal preference. At the population level, PRO data can be used to standardize aspects of care to understand comparative health and disease among all patients in a practice or relative to outside practices, identify outliers, and drive improvement.

Optimizing PROs for use in clinical trials: CD–PROs and UC–PROs

Developing standardized, validated instruments according to FDA guidance is a complex process. The lack of an FDA-approved PRO has resulted in substantial variability in the definitions of clinical response or remission in clinical trials to date.15 As a result, IBD-specific PROs (CD-PRO and UC-PRO) are being developed under FDA guidance for use in clinical trials.16 With achievement of prequalification for open use, UC-PRO and CD-PRO will cover five IBD-specific outcomes domains or modules: 1) bowel signs and symptoms, 2) systemic symptoms, 3) emotional impact, 4) coping behaviors, and 5) IBD impact on daily life. The bowel signs and symptoms module may also incorporate a functional impact assessment. Each module includes numerous pertinent items (e.g., “I feel worried,” “I feel scared,” “I feel alone” in the emotional impact module) and are currently being tailored and scored for practicality and relevance. It is hoped that UC-PRO and CD-PRO in final form will be relevant and applicable for clinical trials and gastroenterology practices alike.

Because the development of the UC-PRO and the CD-PRO is still underway, interim PROs are being used in ongoing clinical trials. These interim measures were extracted from existing components of the CDAI, Mayo Clinic Score, and UC Disease Activity Index. The CD PRO-2 consists of two items: abdominal pain and stool frequency. The UC PRO-2 is composed of rectal bleeding and stool frequency. The PRO-3 adds an item regarding general well-being. The sensitivity of these PROs was tested in studies for CD and UC. Both PROs performed similarly to their respective parent instrument. Important limitations include the lack of validation, and the fact that these interim measures were derived from parent measures with acknowledged limitations as previously discussed. Current clinical trials are coupling these interim measures with endoscopic data as coprimary endpoints.

PROs in routine clinical practice: Are we ready for prime time?

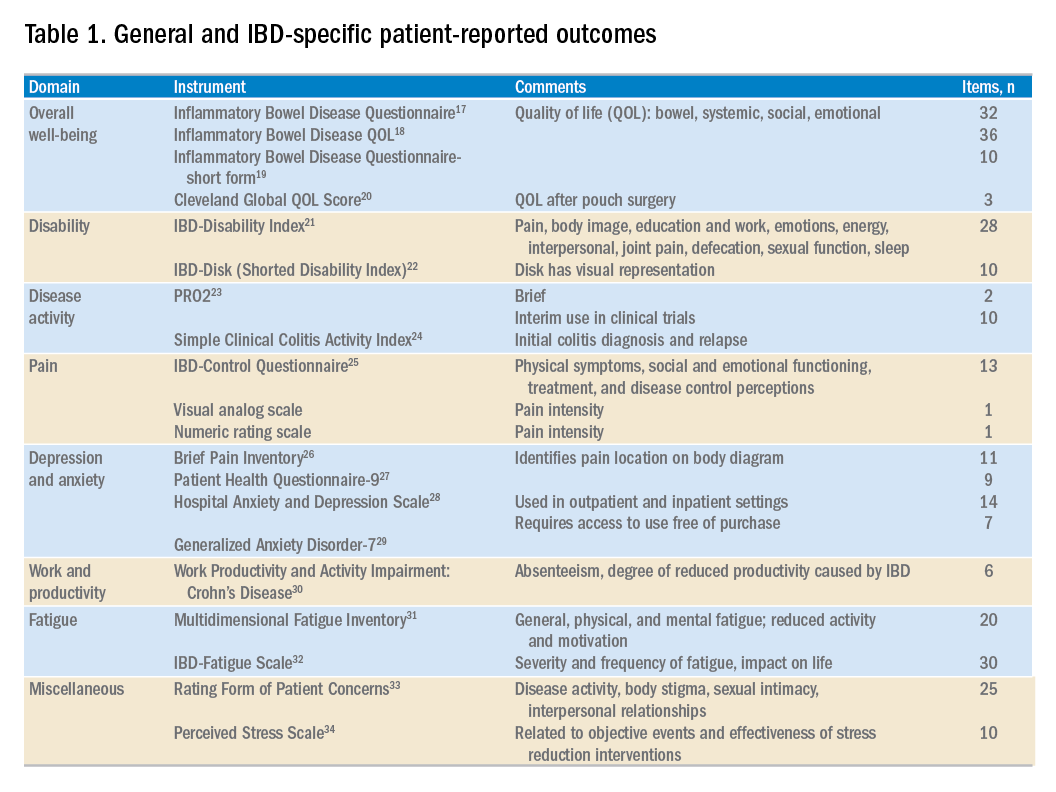

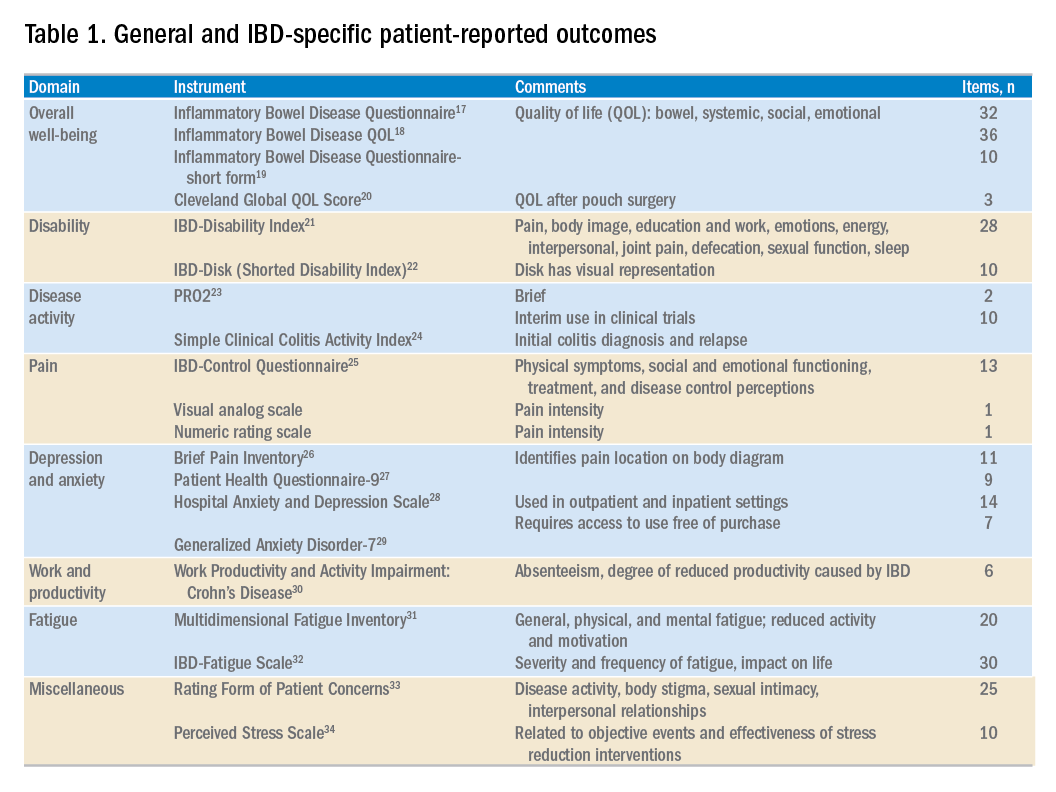

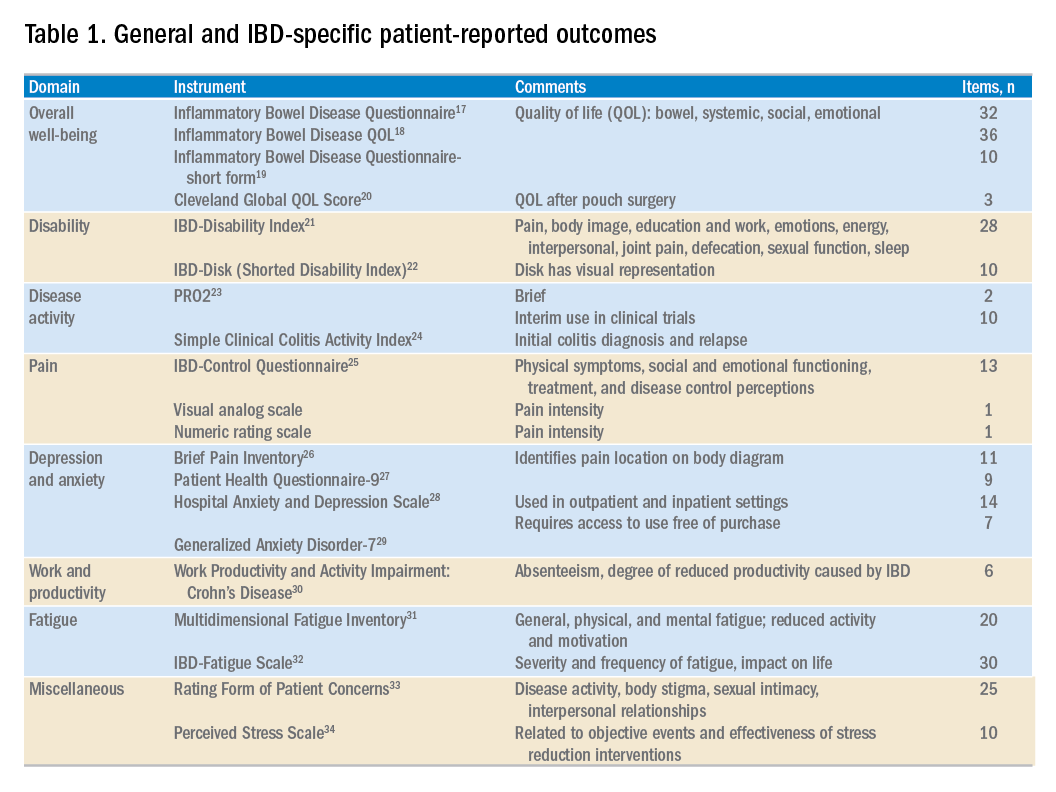

Few instruments developed to date have been widely implemented into routine IBD clinical practice. Table 1 highlights commonly available or recently developed PROs for IBD care. As clinicians strive to more effectively integrate PROs into clinical practice, we propose a three-step process to getting started: 1) select and administer a PRO instrument, 2) identify areas of impairment and create a targeted treatment strategy to focus on those areas, and 3) repeat the same PRO at follow-up to assess for improvement. The instrument can be administered before the visit or in the clinic waiting room. Focus a portion of the patient’s visit on discussing the results and identifying one or more domains to target for improvement. For example, the patient may indicate diarrhea as his/her most important area to target, triggering a symptom-specific investigation and therapeutic approach. The PRO may also highlight social or emotional impairment that may require an ancillary referral. The benefits of this PRO-driven approach to IBD care are twofold. First, the patient’s primary concerns are positioned at the forefront of the clinical visit. Second, aligning the clinician’s focus with the patient input may actually help to streamline each visit and improve overall visit efficiency and patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

As therapies for IBD improve, so should standards of patient-centered care. Clinicians must actively seek and then listen to the concerns of patients and be able to address the multiple facets of living with a chronic disease. PROs empower patients, helping them identify important topics for discussion at the clinical visit. This affords clinicians a better understanding of primary patient concerns before the visit, and potentially improves the quality and value of care. At first, the process of incorporating PROs into a busy clinical practice may be challenging, but targeted treatment plans have the potential to foster a better patient – and physician – experience.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16[5]:603-7).

References

1. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79.

2. Burke, L.B., Kennedy, D.L., Miskala, P.H., et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medical products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281-3.

3. Batalden, M., Baltalden, P., Margolis, P., et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:509-17.

4. Johnson, L.C. Melmed, G.Y., Nelson, E.C., et al. Fostering collaboration through creation of an IBD learning health system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:406-8.

5. Khanna, P., Agarwal, N., Khanna, D., et al. Development of an online library of patient reported outcome measures in gastroenterology: the GI-PRO database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:234-48.

6. Bruining, D.H. Sandborn, W.J. Do not assume symptoms indicate failure of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in January 2015 Emerging Treatment Goals in IBD Trials and Practice 45 REVIEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:395-9.

7. Surti, B., Spiegel, B., Ippoliti, A., et al. Assessing health status in inflammatory bowel disease using a novel single-item numeric rating scale. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1313-21.

8. Marshall, S., Haywood, K. Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:559-68.

9. Simren, M., Axelsson, J., Gillberg, R., et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBD-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389-96.

10. De Jong, M.J., Huibregtse, R., Masclee, A.A.M., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:648-63.

11. Atreja, A., Rizk, M. Capturing patient reported outcomes and quality of life in routine clinical practice: ready to prime time? Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2012;58:19-24.

12. Ishak, W.W., Pan, D., Steiner, A.J., et al. Patient reported outcomes of quality of life, functioning, and GI/psychiatric symptom severity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:798-803.

13. Ho, B., Houck, J.R., Flemister, A.S., et al. Preoperative PROMIS scores predict postoperative success in foot and ankle patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:911-8. 14. Bacalao, E., Greene, G.J., Beaumont, J.L., et al. Standardizing and personalizing the treat to target (T2T) approach for rheumatoid arthritis using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): baseline findings on patient-centered treatment priorities. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1729-36.

15. Ma, C., Panaccione, R., Fedorak, R.N., et al. Heterogeneity in definitions of endpoints for clinical trials of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review for development of a core outcome set. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:637-47.

16. Higgins P. Patient reported outcomes in IBD 2017. Available at: ibdctworkshop.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/patient-reported-outcomes-in-ibd___peter-higgins.pdf. Accessed Aug. 27, 2017.

17. Guyatt, G., Mitchell, A. Irvine, E.J., et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804-10.

18. Love, J.R., Irvine, E.J., Fedorak, R.N. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15-9.

19. Irvine, E.J., Zhou, Q., Thompson, A.K. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-8.

20. Fazio, V.W., O’Riordain, M.G., Lavery, I.C., et al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:575-84.

21. Gower-Rousseau, C., Sarter, H., Savoye, G., et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index in a population-based cohort. Gut. 2017;66:588-96.

22. Gosh, S., Louis, E., Beaugerie, L., et al. Development of the IBD-Disk: a visual self-administered tool assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:333-40.

23. Khanna, R., Zou, G., D’Haens, G., et al. A retrospective analysis: the development of patient reported outcome measures for the assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:77-86.

24. Walmsley, R.S., Ayres, R.C.S., Pounder, P.R., et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29-32.

25. Bodger, K., Ormerod, C., Shackcloth, D., et al. Development and validation of a rapid, general measure of disease control from the patient perspective: the IBD-Control questionnaire. Gut. 2014;63:1092-102.

26. Cleeland, C.S., Ryan, K.M. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-38.

27. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-13.

28. Zigmond, A.S., Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-70.

29. Spitzer, R.L., Korneke, K., Williams, J.B., et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-7.

30. Reilly, M.C., Zbrozek, A.S. Dukes, E.M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmachoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

31. Smets, E.M., Garssen, B. Bonke, B., et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315-25.

32. Czuber-Dochan, W., Norton, C., Bassettt, P., et al. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1398-406.

33. Drossman, D.A., Leserman, J., Li, Z.M., et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701-12. 34. Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385-96.

Dr. Cohen is in the division of digestive and liver diseases; Dr. Melmed is director, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, director, clinical research in the division of gastroenterology, and director, advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellowship program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and UCB; and received support for research from Prometheus Labs. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

Patients seek medical care when they perceive a deterioration in their health. Gastroenterologists and health care providers are trained to seek out clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and endoscopic evidence of pathology. Conventional endpoints in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical trials and clinical care may fail to capture the full health status and disease experience from the patient perspective. The Food and Drug Administration has called for the development of coprimary endpoints in research trials to include an objective measure of inflammation in conjunction with patient-reported outcomes (PROs). The objective is to support labeling claims and improve safety and effectiveness in the drug approval process.1,2 There is also growing recognition that high-value care includes management of biologic and psychosocial factors to enable patients with chronic diseases to regain their health. Clinicians might follow suit by incorporating valid, reliable PRO measures to usual IBD care in order better to achieve patient-centered care, inform decision making, and improve the care provided.

What are patient-reported outcomes?

The FDA defines a PRO as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” Two PROs are used to measure various aspects of health including physical, emotional, or social domains. PROs have emerged as tools that may foster a better understanding of the patient’s condition, which may go beyond disease activity or symptoms. In effect, incorporating PROs into clinical practice enables a model of “coproduction” of health care, and may contribute to a more reciprocal patient-provider interaction where the needs of the patient may be more fully understood and incorporated into decision-making that may lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.3,4

There are hundreds of available PROs in gastroenterology,5 ranging from simple (characterizing pain with a basic numeric rating scale) to complex multidomain, multi-item instruments. PROs may cover symptom assessment, health-related quality of life, and adherence to and satisfaction with treatment, and may be generic or disease specific. Numerous PROs have been developed for patients with IBD. Commonly used PROs in IBD include severity scales for pain, defecatory urgency, and bloody stool, and several disease-specific and generic instruments assessing different health-related quality-of-life domains have been used in research studies for patients with IBD.

The current approach to patient-centered care for IBD is limited

IBD is a difficult disease to manage – in part because there is no known biomarker that accurately reflects the full spectrum of disease activity. Numerous indices have been developed to better quantify disease activity and measure response to treatment. Among the most frequently used indices in clinical trials are the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and (for ulcerative colitis [UC]) the Mayo Clinic Score. These endpoints incorporate signs and symptoms, laboratory findings (in the CDAI), and endoscopic assessments. The CDAI is a suboptimal instrument because of a lack of correlation with endoscopic inflammation and potential confounding with concomitant gastrointestinal illnesses, such as irritable bowel syndrome.6 The Mayo Clinic Score is difficult to interpret because of some subjective elements (what is considered a normal number of stools per day?); vagueness (mostly bloody stools more than half the time?); and need for a physician assessment, which often does not correspond with the patient’s perception of their disease.7 From a research perspective, this disconnect can compromise the quality of trial data. Clinically, it can negatively impact patients’ satisfaction and impair the patient-provider relationship.8

To that end, regulatory agencies, scientific bodies, and health care payors are shifting toward a more “patient-centered” approach with an emphasis on PROs. However, although the FDA is incorporating the patient perspective in its trials, measuring meaningful outcomes in day-to-day clinical care is challenging. In the absence of active inflammation, more than 30% of patients with IBD still suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms.9 Furthermore, physicians frequently underestimate the effect of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep on patient health. Likewise, some patients with active small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) may experience few gastrointestinal symptoms but have profound fatigue, weight loss, and impaired quality of life. A focused assessment for disease activity may fail to identify aspects of health most relevant or important to individual patient well-being. There is a need for effective, efficient, and standardized strategies to better understand the concerns of the individual seeking help.

Although there are several PROs that measure disease activity primarily for clinical research trials,10 their prevalence in gastroenterology practices has not been assessed. Most likely, few clinical practices currently integrate standardized PROs in routine patient care. This may be because of several reasons, including lack of awareness of newly developed PROs, administrative burden including time and resources to collect PROs, potentially complex interpretation of results, and perhaps a reluctance among physicians to alter traditional patient interview methods of obtaining information about the health status of their patients. For effective use in clinical care, PROs require simple and relevant interpretation to add value to the clinician’s practice, and must minimally impact clinical flow and resources. The use of Internet-enabled tablets has been shown to be a feasible, efficient, and effective means of PRO assessment in gastroenterology practices, with good levels of patient satisfaction.11

Reaping potential benefits of patient-reported outcomes

The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an initiative developed to investigate and promote implementation of PRO measures among patients with chronic diseases. The collection of PROMIS measures has been shown to be feasible at a tertiary care IBD center, enabling a biopsychosocial model of care.12 Likewise, implementation of PROs in other clinical areas including oncology, orthopedics, and rheumatology has been robust.

In an innovative orthopedic study, PROMIS measures collected and linked to the electronic medical record predicted the likelihood of a clinically meaningful benefit from foot and ankle surgery.13 This facilitated tailored patient-specific preoperative discussions about the expected benefit of surgery. In a study at a rheumatology clinic patients with rheumatoid arthritis were asked to identify their highest priority treatment targets using PROMIS domains (fatigue, pain, depression, social function). The highest priority domain was tracked over time as a patient-centered marker of health, essentially personalizing measures of success for the individual patient.14

PROs have the unique potential to affect multiple levels of health care. At the patient level, PRO data can identify specific concerns, manage expectations of recovery, and tailor treatment decisions to personal preference. At the population level, PRO data can be used to standardize aspects of care to understand comparative health and disease among all patients in a practice or relative to outside practices, identify outliers, and drive improvement.

Optimizing PROs for use in clinical trials: CD–PROs and UC–PROs

Developing standardized, validated instruments according to FDA guidance is a complex process. The lack of an FDA-approved PRO has resulted in substantial variability in the definitions of clinical response or remission in clinical trials to date.15 As a result, IBD-specific PROs (CD-PRO and UC-PRO) are being developed under FDA guidance for use in clinical trials.16 With achievement of prequalification for open use, UC-PRO and CD-PRO will cover five IBD-specific outcomes domains or modules: 1) bowel signs and symptoms, 2) systemic symptoms, 3) emotional impact, 4) coping behaviors, and 5) IBD impact on daily life. The bowel signs and symptoms module may also incorporate a functional impact assessment. Each module includes numerous pertinent items (e.g., “I feel worried,” “I feel scared,” “I feel alone” in the emotional impact module) and are currently being tailored and scored for practicality and relevance. It is hoped that UC-PRO and CD-PRO in final form will be relevant and applicable for clinical trials and gastroenterology practices alike.

Because the development of the UC-PRO and the CD-PRO is still underway, interim PROs are being used in ongoing clinical trials. These interim measures were extracted from existing components of the CDAI, Mayo Clinic Score, and UC Disease Activity Index. The CD PRO-2 consists of two items: abdominal pain and stool frequency. The UC PRO-2 is composed of rectal bleeding and stool frequency. The PRO-3 adds an item regarding general well-being. The sensitivity of these PROs was tested in studies for CD and UC. Both PROs performed similarly to their respective parent instrument. Important limitations include the lack of validation, and the fact that these interim measures were derived from parent measures with acknowledged limitations as previously discussed. Current clinical trials are coupling these interim measures with endoscopic data as coprimary endpoints.

PROs in routine clinical practice: Are we ready for prime time?

Few instruments developed to date have been widely implemented into routine IBD clinical practice. Table 1 highlights commonly available or recently developed PROs for IBD care. As clinicians strive to more effectively integrate PROs into clinical practice, we propose a three-step process to getting started: 1) select and administer a PRO instrument, 2) identify areas of impairment and create a targeted treatment strategy to focus on those areas, and 3) repeat the same PRO at follow-up to assess for improvement. The instrument can be administered before the visit or in the clinic waiting room. Focus a portion of the patient’s visit on discussing the results and identifying one or more domains to target for improvement. For example, the patient may indicate diarrhea as his/her most important area to target, triggering a symptom-specific investigation and therapeutic approach. The PRO may also highlight social or emotional impairment that may require an ancillary referral. The benefits of this PRO-driven approach to IBD care are twofold. First, the patient’s primary concerns are positioned at the forefront of the clinical visit. Second, aligning the clinician’s focus with the patient input may actually help to streamline each visit and improve overall visit efficiency and patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

As therapies for IBD improve, so should standards of patient-centered care. Clinicians must actively seek and then listen to the concerns of patients and be able to address the multiple facets of living with a chronic disease. PROs empower patients, helping them identify important topics for discussion at the clinical visit. This affords clinicians a better understanding of primary patient concerns before the visit, and potentially improves the quality and value of care. At first, the process of incorporating PROs into a busy clinical practice may be challenging, but targeted treatment plans have the potential to foster a better patient – and physician – experience.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16[5]:603-7).

References

1. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79.

2. Burke, L.B., Kennedy, D.L., Miskala, P.H., et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medical products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281-3.

3. Batalden, M., Baltalden, P., Margolis, P., et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:509-17.

4. Johnson, L.C. Melmed, G.Y., Nelson, E.C., et al. Fostering collaboration through creation of an IBD learning health system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:406-8.

5. Khanna, P., Agarwal, N., Khanna, D., et al. Development of an online library of patient reported outcome measures in gastroenterology: the GI-PRO database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:234-48.

6. Bruining, D.H. Sandborn, W.J. Do not assume symptoms indicate failure of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in January 2015 Emerging Treatment Goals in IBD Trials and Practice 45 REVIEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:395-9.

7. Surti, B., Spiegel, B., Ippoliti, A., et al. Assessing health status in inflammatory bowel disease using a novel single-item numeric rating scale. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1313-21.

8. Marshall, S., Haywood, K. Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:559-68.

9. Simren, M., Axelsson, J., Gillberg, R., et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBD-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389-96.

10. De Jong, M.J., Huibregtse, R., Masclee, A.A.M., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:648-63.

11. Atreja, A., Rizk, M. Capturing patient reported outcomes and quality of life in routine clinical practice: ready to prime time? Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2012;58:19-24.

12. Ishak, W.W., Pan, D., Steiner, A.J., et al. Patient reported outcomes of quality of life, functioning, and GI/psychiatric symptom severity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:798-803.

13. Ho, B., Houck, J.R., Flemister, A.S., et al. Preoperative PROMIS scores predict postoperative success in foot and ankle patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:911-8. 14. Bacalao, E., Greene, G.J., Beaumont, J.L., et al. Standardizing and personalizing the treat to target (T2T) approach for rheumatoid arthritis using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): baseline findings on patient-centered treatment priorities. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1729-36.

15. Ma, C., Panaccione, R., Fedorak, R.N., et al. Heterogeneity in definitions of endpoints for clinical trials of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review for development of a core outcome set. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:637-47.

16. Higgins P. Patient reported outcomes in IBD 2017. Available at: ibdctworkshop.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/patient-reported-outcomes-in-ibd___peter-higgins.pdf. Accessed Aug. 27, 2017.

17. Guyatt, G., Mitchell, A. Irvine, E.J., et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804-10.

18. Love, J.R., Irvine, E.J., Fedorak, R.N. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15-9.

19. Irvine, E.J., Zhou, Q., Thompson, A.K. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-8.

20. Fazio, V.W., O’Riordain, M.G., Lavery, I.C., et al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:575-84.

21. Gower-Rousseau, C., Sarter, H., Savoye, G., et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index in a population-based cohort. Gut. 2017;66:588-96.

22. Gosh, S., Louis, E., Beaugerie, L., et al. Development of the IBD-Disk: a visual self-administered tool assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:333-40.

23. Khanna, R., Zou, G., D’Haens, G., et al. A retrospective analysis: the development of patient reported outcome measures for the assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:77-86.

24. Walmsley, R.S., Ayres, R.C.S., Pounder, P.R., et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29-32.

25. Bodger, K., Ormerod, C., Shackcloth, D., et al. Development and validation of a rapid, general measure of disease control from the patient perspective: the IBD-Control questionnaire. Gut. 2014;63:1092-102.

26. Cleeland, C.S., Ryan, K.M. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-38.

27. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-13.

28. Zigmond, A.S., Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-70.

29. Spitzer, R.L., Korneke, K., Williams, J.B., et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-7.

30. Reilly, M.C., Zbrozek, A.S. Dukes, E.M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmachoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

31. Smets, E.M., Garssen, B. Bonke, B., et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315-25.

32. Czuber-Dochan, W., Norton, C., Bassettt, P., et al. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1398-406.

33. Drossman, D.A., Leserman, J., Li, Z.M., et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701-12. 34. Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385-96.

Dr. Cohen is in the division of digestive and liver diseases; Dr. Melmed is director, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, director, clinical research in the division of gastroenterology, and director, advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellowship program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and UCB; and received support for research from Prometheus Labs. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

Patients seek medical care when they perceive a deterioration in their health. Gastroenterologists and health care providers are trained to seek out clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and endoscopic evidence of pathology. Conventional endpoints in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical trials and clinical care may fail to capture the full health status and disease experience from the patient perspective. The Food and Drug Administration has called for the development of coprimary endpoints in research trials to include an objective measure of inflammation in conjunction with patient-reported outcomes (PROs). The objective is to support labeling claims and improve safety and effectiveness in the drug approval process.1,2 There is also growing recognition that high-value care includes management of biologic and psychosocial factors to enable patients with chronic diseases to regain their health. Clinicians might follow suit by incorporating valid, reliable PRO measures to usual IBD care in order better to achieve patient-centered care, inform decision making, and improve the care provided.

What are patient-reported outcomes?

The FDA defines a PRO as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” Two PROs are used to measure various aspects of health including physical, emotional, or social domains. PROs have emerged as tools that may foster a better understanding of the patient’s condition, which may go beyond disease activity or symptoms. In effect, incorporating PROs into clinical practice enables a model of “coproduction” of health care, and may contribute to a more reciprocal patient-provider interaction where the needs of the patient may be more fully understood and incorporated into decision-making that may lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.3,4

There are hundreds of available PROs in gastroenterology,5 ranging from simple (characterizing pain with a basic numeric rating scale) to complex multidomain, multi-item instruments. PROs may cover symptom assessment, health-related quality of life, and adherence to and satisfaction with treatment, and may be generic or disease specific. Numerous PROs have been developed for patients with IBD. Commonly used PROs in IBD include severity scales for pain, defecatory urgency, and bloody stool, and several disease-specific and generic instruments assessing different health-related quality-of-life domains have been used in research studies for patients with IBD.

The current approach to patient-centered care for IBD is limited

IBD is a difficult disease to manage – in part because there is no known biomarker that accurately reflects the full spectrum of disease activity. Numerous indices have been developed to better quantify disease activity and measure response to treatment. Among the most frequently used indices in clinical trials are the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and (for ulcerative colitis [UC]) the Mayo Clinic Score. These endpoints incorporate signs and symptoms, laboratory findings (in the CDAI), and endoscopic assessments. The CDAI is a suboptimal instrument because of a lack of correlation with endoscopic inflammation and potential confounding with concomitant gastrointestinal illnesses, such as irritable bowel syndrome.6 The Mayo Clinic Score is difficult to interpret because of some subjective elements (what is considered a normal number of stools per day?); vagueness (mostly bloody stools more than half the time?); and need for a physician assessment, which often does not correspond with the patient’s perception of their disease.7 From a research perspective, this disconnect can compromise the quality of trial data. Clinically, it can negatively impact patients’ satisfaction and impair the patient-provider relationship.8

To that end, regulatory agencies, scientific bodies, and health care payors are shifting toward a more “patient-centered” approach with an emphasis on PROs. However, although the FDA is incorporating the patient perspective in its trials, measuring meaningful outcomes in day-to-day clinical care is challenging. In the absence of active inflammation, more than 30% of patients with IBD still suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms.9 Furthermore, physicians frequently underestimate the effect of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep on patient health. Likewise, some patients with active small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) may experience few gastrointestinal symptoms but have profound fatigue, weight loss, and impaired quality of life. A focused assessment for disease activity may fail to identify aspects of health most relevant or important to individual patient well-being. There is a need for effective, efficient, and standardized strategies to better understand the concerns of the individual seeking help.

Although there are several PROs that measure disease activity primarily for clinical research trials,10 their prevalence in gastroenterology practices has not been assessed. Most likely, few clinical practices currently integrate standardized PROs in routine patient care. This may be because of several reasons, including lack of awareness of newly developed PROs, administrative burden including time and resources to collect PROs, potentially complex interpretation of results, and perhaps a reluctance among physicians to alter traditional patient interview methods of obtaining information about the health status of their patients. For effective use in clinical care, PROs require simple and relevant interpretation to add value to the clinician’s practice, and must minimally impact clinical flow and resources. The use of Internet-enabled tablets has been shown to be a feasible, efficient, and effective means of PRO assessment in gastroenterology practices, with good levels of patient satisfaction.11

Reaping potential benefits of patient-reported outcomes

The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an initiative developed to investigate and promote implementation of PRO measures among patients with chronic diseases. The collection of PROMIS measures has been shown to be feasible at a tertiary care IBD center, enabling a biopsychosocial model of care.12 Likewise, implementation of PROs in other clinical areas including oncology, orthopedics, and rheumatology has been robust.

In an innovative orthopedic study, PROMIS measures collected and linked to the electronic medical record predicted the likelihood of a clinically meaningful benefit from foot and ankle surgery.13 This facilitated tailored patient-specific preoperative discussions about the expected benefit of surgery. In a study at a rheumatology clinic patients with rheumatoid arthritis were asked to identify their highest priority treatment targets using PROMIS domains (fatigue, pain, depression, social function). The highest priority domain was tracked over time as a patient-centered marker of health, essentially personalizing measures of success for the individual patient.14

PROs have the unique potential to affect multiple levels of health care. At the patient level, PRO data can identify specific concerns, manage expectations of recovery, and tailor treatment decisions to personal preference. At the population level, PRO data can be used to standardize aspects of care to understand comparative health and disease among all patients in a practice or relative to outside practices, identify outliers, and drive improvement.

Optimizing PROs for use in clinical trials: CD–PROs and UC–PROs

Developing standardized, validated instruments according to FDA guidance is a complex process. The lack of an FDA-approved PRO has resulted in substantial variability in the definitions of clinical response or remission in clinical trials to date.15 As a result, IBD-specific PROs (CD-PRO and UC-PRO) are being developed under FDA guidance for use in clinical trials.16 With achievement of prequalification for open use, UC-PRO and CD-PRO will cover five IBD-specific outcomes domains or modules: 1) bowel signs and symptoms, 2) systemic symptoms, 3) emotional impact, 4) coping behaviors, and 5) IBD impact on daily life. The bowel signs and symptoms module may also incorporate a functional impact assessment. Each module includes numerous pertinent items (e.g., “I feel worried,” “I feel scared,” “I feel alone” in the emotional impact module) and are currently being tailored and scored for practicality and relevance. It is hoped that UC-PRO and CD-PRO in final form will be relevant and applicable for clinical trials and gastroenterology practices alike.

Because the development of the UC-PRO and the CD-PRO is still underway, interim PROs are being used in ongoing clinical trials. These interim measures were extracted from existing components of the CDAI, Mayo Clinic Score, and UC Disease Activity Index. The CD PRO-2 consists of two items: abdominal pain and stool frequency. The UC PRO-2 is composed of rectal bleeding and stool frequency. The PRO-3 adds an item regarding general well-being. The sensitivity of these PROs was tested in studies for CD and UC. Both PROs performed similarly to their respective parent instrument. Important limitations include the lack of validation, and the fact that these interim measures were derived from parent measures with acknowledged limitations as previously discussed. Current clinical trials are coupling these interim measures with endoscopic data as coprimary endpoints.

PROs in routine clinical practice: Are we ready for prime time?

Few instruments developed to date have been widely implemented into routine IBD clinical practice. Table 1 highlights commonly available or recently developed PROs for IBD care. As clinicians strive to more effectively integrate PROs into clinical practice, we propose a three-step process to getting started: 1) select and administer a PRO instrument, 2) identify areas of impairment and create a targeted treatment strategy to focus on those areas, and 3) repeat the same PRO at follow-up to assess for improvement. The instrument can be administered before the visit or in the clinic waiting room. Focus a portion of the patient’s visit on discussing the results and identifying one or more domains to target for improvement. For example, the patient may indicate diarrhea as his/her most important area to target, triggering a symptom-specific investigation and therapeutic approach. The PRO may also highlight social or emotional impairment that may require an ancillary referral. The benefits of this PRO-driven approach to IBD care are twofold. First, the patient’s primary concerns are positioned at the forefront of the clinical visit. Second, aligning the clinician’s focus with the patient input may actually help to streamline each visit and improve overall visit efficiency and patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

As therapies for IBD improve, so should standards of patient-centered care. Clinicians must actively seek and then listen to the concerns of patients and be able to address the multiple facets of living with a chronic disease. PROs empower patients, helping them identify important topics for discussion at the clinical visit. This affords clinicians a better understanding of primary patient concerns before the visit, and potentially improves the quality and value of care. At first, the process of incorporating PROs into a busy clinical practice may be challenging, but targeted treatment plans have the potential to foster a better patient – and physician – experience.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16[5]:603-7).

References

1. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79.

2. Burke, L.B., Kennedy, D.L., Miskala, P.H., et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medical products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281-3.

3. Batalden, M., Baltalden, P., Margolis, P., et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:509-17.

4. Johnson, L.C. Melmed, G.Y., Nelson, E.C., et al. Fostering collaboration through creation of an IBD learning health system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:406-8.

5. Khanna, P., Agarwal, N., Khanna, D., et al. Development of an online library of patient reported outcome measures in gastroenterology: the GI-PRO database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:234-48.

6. Bruining, D.H. Sandborn, W.J. Do not assume symptoms indicate failure of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in January 2015 Emerging Treatment Goals in IBD Trials and Practice 45 REVIEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:395-9.

7. Surti, B., Spiegel, B., Ippoliti, A., et al. Assessing health status in inflammatory bowel disease using a novel single-item numeric rating scale. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1313-21.

8. Marshall, S., Haywood, K. Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:559-68.

9. Simren, M., Axelsson, J., Gillberg, R., et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBD-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389-96.

10. De Jong, M.J., Huibregtse, R., Masclee, A.A.M., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:648-63.

11. Atreja, A., Rizk, M. Capturing patient reported outcomes and quality of life in routine clinical practice: ready to prime time? Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2012;58:19-24.

12. Ishak, W.W., Pan, D., Steiner, A.J., et al. Patient reported outcomes of quality of life, functioning, and GI/psychiatric symptom severity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:798-803.

13. Ho, B., Houck, J.R., Flemister, A.S., et al. Preoperative PROMIS scores predict postoperative success in foot and ankle patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:911-8. 14. Bacalao, E., Greene, G.J., Beaumont, J.L., et al. Standardizing and personalizing the treat to target (T2T) approach for rheumatoid arthritis using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): baseline findings on patient-centered treatment priorities. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1729-36.

15. Ma, C., Panaccione, R., Fedorak, R.N., et al. Heterogeneity in definitions of endpoints for clinical trials of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review for development of a core outcome set. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:637-47.

16. Higgins P. Patient reported outcomes in IBD 2017. Available at: ibdctworkshop.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/patient-reported-outcomes-in-ibd___peter-higgins.pdf. Accessed Aug. 27, 2017.

17. Guyatt, G., Mitchell, A. Irvine, E.J., et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804-10.

18. Love, J.R., Irvine, E.J., Fedorak, R.N. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15-9.

19. Irvine, E.J., Zhou, Q., Thompson, A.K. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-8.

20. Fazio, V.W., O’Riordain, M.G., Lavery, I.C., et al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:575-84.

21. Gower-Rousseau, C., Sarter, H., Savoye, G., et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index in a population-based cohort. Gut. 2017;66:588-96.

22. Gosh, S., Louis, E., Beaugerie, L., et al. Development of the IBD-Disk: a visual self-administered tool assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:333-40.

23. Khanna, R., Zou, G., D’Haens, G., et al. A retrospective analysis: the development of patient reported outcome measures for the assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:77-86.

24. Walmsley, R.S., Ayres, R.C.S., Pounder, P.R., et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29-32.

25. Bodger, K., Ormerod, C., Shackcloth, D., et al. Development and validation of a rapid, general measure of disease control from the patient perspective: the IBD-Control questionnaire. Gut. 2014;63:1092-102.

26. Cleeland, C.S., Ryan, K.M. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-38.

27. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-13.

28. Zigmond, A.S., Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-70.

29. Spitzer, R.L., Korneke, K., Williams, J.B., et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-7.

30. Reilly, M.C., Zbrozek, A.S. Dukes, E.M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmachoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

31. Smets, E.M., Garssen, B. Bonke, B., et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315-25.

32. Czuber-Dochan, W., Norton, C., Bassettt, P., et al. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1398-406.

33. Drossman, D.A., Leserman, J., Li, Z.M., et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701-12. 34. Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385-96.

Dr. Cohen is in the division of digestive and liver diseases; Dr. Melmed is director, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, director, clinical research in the division of gastroenterology, and director, advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellowship program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and UCB; and received support for research from Prometheus Labs. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

Night sweats

A 46-year-old man comes to clinic for evaluation of night sweats. He has been having drenching night sweats for the past 3 months. He has to change his night shirt at least once per night. He has had a 10-pound weight gain over the past 6 months. No chest pain, nausea, or fatigue. He has had a cough for the past 6 months.

Which is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

B. Tuberculosis.

C. Lymphoma.

D. Multiple myeloma.

Night sweats are a common symptom in the general population, estimated to occur in about 10% of people. They can range in frequency and severity. We become most concerned when the patient is concerned, usually when they report drenching night sweats.

What do we need to know about this symptom to help us think of more likely causes and guide us in a more appropriate workup?

Night sweats do not seem to be a bad prognostic symptom. James W. Mold, MD, and his colleagues looked at the prognostic significance of night sweats in two cohorts of elderly patients.1 The prevalence of night sweats in this study was 10%. These two cohorts were followed for a little more than 7 years. More than 1,500 patients were included in the two cohorts. Patients who reported night sweats were not more likely to die, or die sooner, than were those who didn’t have night sweats. The severity of the night sweats did not make a difference.

Lea et al. described the prevalence of night sweats among different inpatient populations, with a range from 33% in surgical and medicine patients, to 60% on obstetrics service.2

Night sweats are common, and don’t appear to be correlated with worse prognosis. So, what are the likely common causes?

There just aren’t good studies on causes of night sweats, but there are studies that suggest that they are seen in some very common diseases. It is always good to look at medication lists as a start when evaluating unexplained symptoms.

Dr. Mold, along with Barbara J. Holtzclaw, PhD, reported higher odds ratios for night sweats for patients on SSRIs (OR, 3.01), angiotensin receptor blockers (OR, 3.44) and thyroid hormone supplements (OR, 2.53).3 W.A. Reynolds, MD, looked at the prevalence of night sweats in a GI practice.4 A total of 41% of the patients reported night sweats, and 12 of 12 patients with GERD who had night sweats had resolution of the night sweats with effective treatment of the GERD.

Dr. Mold and his colleagues found that night sweats were associated with several sleep-related symptoms, including waking up with a bitter taste in the mouth (OR, 1.94), daytime tiredness (OR, 1.99), and legs jerking during sleep (OR, 1.87).5

Erna Arnardottir, PhD, and her colleagues found that obstructive sleep apnea was associated with frequent nocturnal sweating.6 They found that 31% of men and 33% of women with OSA had nocturnal sweating, compared with about 10% of the general population. When the OSA patients were treated with positive airway pressure, the prevalence of nocturnal sweating decreased to 11.5%, similar to general population numbers.

Pearl: Night sweats are associated with common conditions: medications, GERD, and sleep disorders. These are more likely than lymphoma and tuberculosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Jan-Feb;23(1):97-103.

2. South Med J. 1985 Sep;78(9):1065-7.

3. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015 Mar;2(1):29-33.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989 Oct;11(5):590-1.

5. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Sep-Oct;4(5):423-6.

6. BMJ Open. 2013 May 14;3(5).

A 46-year-old man comes to clinic for evaluation of night sweats. He has been having drenching night sweats for the past 3 months. He has to change his night shirt at least once per night. He has had a 10-pound weight gain over the past 6 months. No chest pain, nausea, or fatigue. He has had a cough for the past 6 months.

Which is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

B. Tuberculosis.

C. Lymphoma.

D. Multiple myeloma.

Night sweats are a common symptom in the general population, estimated to occur in about 10% of people. They can range in frequency and severity. We become most concerned when the patient is concerned, usually when they report drenching night sweats.

What do we need to know about this symptom to help us think of more likely causes and guide us in a more appropriate workup?

Night sweats do not seem to be a bad prognostic symptom. James W. Mold, MD, and his colleagues looked at the prognostic significance of night sweats in two cohorts of elderly patients.1 The prevalence of night sweats in this study was 10%. These two cohorts were followed for a little more than 7 years. More than 1,500 patients were included in the two cohorts. Patients who reported night sweats were not more likely to die, or die sooner, than were those who didn’t have night sweats. The severity of the night sweats did not make a difference.

Lea et al. described the prevalence of night sweats among different inpatient populations, with a range from 33% in surgical and medicine patients, to 60% on obstetrics service.2

Night sweats are common, and don’t appear to be correlated with worse prognosis. So, what are the likely common causes?

There just aren’t good studies on causes of night sweats, but there are studies that suggest that they are seen in some very common diseases. It is always good to look at medication lists as a start when evaluating unexplained symptoms.

Dr. Mold, along with Barbara J. Holtzclaw, PhD, reported higher odds ratios for night sweats for patients on SSRIs (OR, 3.01), angiotensin receptor blockers (OR, 3.44) and thyroid hormone supplements (OR, 2.53).3 W.A. Reynolds, MD, looked at the prevalence of night sweats in a GI practice.4 A total of 41% of the patients reported night sweats, and 12 of 12 patients with GERD who had night sweats had resolution of the night sweats with effective treatment of the GERD.

Dr. Mold and his colleagues found that night sweats were associated with several sleep-related symptoms, including waking up with a bitter taste in the mouth (OR, 1.94), daytime tiredness (OR, 1.99), and legs jerking during sleep (OR, 1.87).5

Erna Arnardottir, PhD, and her colleagues found that obstructive sleep apnea was associated with frequent nocturnal sweating.6 They found that 31% of men and 33% of women with OSA had nocturnal sweating, compared with about 10% of the general population. When the OSA patients were treated with positive airway pressure, the prevalence of nocturnal sweating decreased to 11.5%, similar to general population numbers.

Pearl: Night sweats are associated with common conditions: medications, GERD, and sleep disorders. These are more likely than lymphoma and tuberculosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Jan-Feb;23(1):97-103.

2. South Med J. 1985 Sep;78(9):1065-7.

3. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015 Mar;2(1):29-33.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989 Oct;11(5):590-1.

5. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Sep-Oct;4(5):423-6.

6. BMJ Open. 2013 May 14;3(5).

A 46-year-old man comes to clinic for evaluation of night sweats. He has been having drenching night sweats for the past 3 months. He has to change his night shirt at least once per night. He has had a 10-pound weight gain over the past 6 months. No chest pain, nausea, or fatigue. He has had a cough for the past 6 months.

Which is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

B. Tuberculosis.

C. Lymphoma.

D. Multiple myeloma.

Night sweats are a common symptom in the general population, estimated to occur in about 10% of people. They can range in frequency and severity. We become most concerned when the patient is concerned, usually when they report drenching night sweats.

What do we need to know about this symptom to help us think of more likely causes and guide us in a more appropriate workup?

Night sweats do not seem to be a bad prognostic symptom. James W. Mold, MD, and his colleagues looked at the prognostic significance of night sweats in two cohorts of elderly patients.1 The prevalence of night sweats in this study was 10%. These two cohorts were followed for a little more than 7 years. More than 1,500 patients were included in the two cohorts. Patients who reported night sweats were not more likely to die, or die sooner, than were those who didn’t have night sweats. The severity of the night sweats did not make a difference.

Lea et al. described the prevalence of night sweats among different inpatient populations, with a range from 33% in surgical and medicine patients, to 60% on obstetrics service.2

Night sweats are common, and don’t appear to be correlated with worse prognosis. So, what are the likely common causes?

There just aren’t good studies on causes of night sweats, but there are studies that suggest that they are seen in some very common diseases. It is always good to look at medication lists as a start when evaluating unexplained symptoms.

Dr. Mold, along with Barbara J. Holtzclaw, PhD, reported higher odds ratios for night sweats for patients on SSRIs (OR, 3.01), angiotensin receptor blockers (OR, 3.44) and thyroid hormone supplements (OR, 2.53).3 W.A. Reynolds, MD, looked at the prevalence of night sweats in a GI practice.4 A total of 41% of the patients reported night sweats, and 12 of 12 patients with GERD who had night sweats had resolution of the night sweats with effective treatment of the GERD.

Dr. Mold and his colleagues found that night sweats were associated with several sleep-related symptoms, including waking up with a bitter taste in the mouth (OR, 1.94), daytime tiredness (OR, 1.99), and legs jerking during sleep (OR, 1.87).5

Erna Arnardottir, PhD, and her colleagues found that obstructive sleep apnea was associated with frequent nocturnal sweating.6 They found that 31% of men and 33% of women with OSA had nocturnal sweating, compared with about 10% of the general population. When the OSA patients were treated with positive airway pressure, the prevalence of nocturnal sweating decreased to 11.5%, similar to general population numbers.

Pearl: Night sweats are associated with common conditions: medications, GERD, and sleep disorders. These are more likely than lymphoma and tuberculosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Jan-Feb;23(1):97-103.

2. South Med J. 1985 Sep;78(9):1065-7.

3. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015 Mar;2(1):29-33.

4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989 Oct;11(5):590-1.

5. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Sep-Oct;4(5):423-6.

6. BMJ Open. 2013 May 14;3(5).

Hospitalists can meet the demand for physician executives

HM provides “foundational leadership skills”

Hospitals and health systems are increasingly looking to physicians to provide leadership at the most senior executive level. While the chief medical officer (CMO) or similar role has given physicians a seat at the executive table at many organizations, physicians are also being sought for the CEO role at the head of that table.

A commonly referenced study from 2011 by Amanda Goodall, MD, in Social Science & Medicine concluded that, among a cohort of highly ranked hospitals, overall quality metrics were approximately 25% higher in hospitals where a physician was CEO, in comparison to hospitals with non-physician CEOs (2011 Aug;73[4]:535-9). In addition, new positions at both the hospital and health system level are coming into existence: Examples include chief (or VP) of population health, chief innovation officer, chief quality officer, chief patient experience officer, and others.

There is every reason to think that these senior executive physician roles can – and in many cases perhaps should – be filled by hospitalists. Hospital medicine is an ideal “proving ground” for future physician executives and leaders. I believe that the best practitioners of hospital medicine are also the best candidates for hospital, health care, and health system physician executive leadership, because many of the characteristics essential for success as an executive are the same characteristics that are essential for success as a hospitalist. Strong candidates should have the following characteristics:

- A patient-centered perspective. Perhaps the most important characteristic of a leader is empathy. To appreciate the complex, and often (if not usual) challenging emotional states of our patients keeps us connected at the most fundamental, human level to the work we do and to our patients and families. Empathy can – and should – extend to fellow caregivers as well, and allows us to practice and lead teams in the most human of professions. No leader – in health care, anyway – can last long without being able to demonstrate empathy, through words and behavior.

- A systems-based practice: A hospitalist must be able to have a foot in each of two canoes – to be able to see each patient and their family individually and develop preference-based plans of care, and also to be able to focus on process, structure, and outcomes for the hospital system as a whole. The former trait is imbued in us during training and is the critical foundation for the patient-physician relationship. The latter, however, is something different entirely and reflects an ability to have perspective on the entire ecosystem of care – and apply principles of process and quality improvement to achieve forward looking results. That’s leadership.

- Team leadership: Another fundamental attribute of leaders is to assemble a talented and diverse team around an objective, and then to delegate both tasks and their ownership, deferring to expertise. Hospitalists – the best ones, anyway – similarly recognize that for the vast majority of a patient’s hospital stay, the most important caregiver in a patient’s care is someone other than themselves. At any given time, it might be the nurse, aide, pharmacist, care manager, transporter, radiology tech, urologist, housekeeper, surgical resident, or anyone involved in that patient’s care. The hospitalist’s greatest value is in developing the plan of care with the patient and their family, and then communicating – and therefore delegating – that plan to individuals with the expertise to execute that plan. I believe the biggest difficulty hospitalists have in assuming leadership roles is getting out of the comfortable weeds of daily clinical operations and instead focusing on goals, strategies, and teams to accomplish them. The best hospitalists are doing this already as part of their daily care.

- The ability to manage relationships: Hospitalists manage and work among a team of diverse talents. They also often have accountability relationships to a myriad of clinical and administrative leaders in the hospital, each of whom may be in a position of authority to place demands on the hospitalists: A partial list might include the CEO, the chief medical officer, chief nurse, chief of staff, other medical staff departments, academic leaders, and of course, patients and their families. Functioning in a “matrixed” organization – in which lines of authority can go in many directions, depending on the situation – is standard fare, even at the executive level, and the key competency is open and frequent communication.

- Experience: Already, hospitalists assume leadership roles in their hospitals – leaders in quality, medical informatics, patient experience, and continuous improvement. In these roles, physicians work with senior executives and other hospital leaders to both set goals and implement strategies, providing visibility and working relationships that can be helpful to aspiring leaders.

Perhaps more so than most other specialties, then, hospitalists demonstrate foundational leadership skills in their day-to-day practice – an ideal start to a leadership path. This is not to say or suggest that a career devoted purely to clinical practice is somehow inferior – far from it. However, as health care organizations turn to the medical community to provider leadership, hospitalists are well positioned to develop and be developed as executive leaders.

How can the Society of Hospital Medicine help? While management degrees become a common pathway for many, some health systems and professional organizations support their membership with a leadership development curriculum which may be a better place to start. In my opinion, SHM provides one of the most thorough and relevant experiences available. The SHM Leadership Academy focuses on developing a broad set of additional leadership competencies across a spectrum of experience. The format varies depending on the course, but all rely heavily upon experienced hospitalist leaders – in fact, many current and former Board members and officers volunteer their time to facilitate and teach at the Academy, including at the entry level. It’s a powerful way to learn from others who have started walking the leadership path.

Dr. Harte is a past president of SHM and president of Cleveland Clinic Akron General and Southern Region.

HM provides “foundational leadership skills”

HM provides “foundational leadership skills”

Hospitals and health systems are increasingly looking to physicians to provide leadership at the most senior executive level. While the chief medical officer (CMO) or similar role has given physicians a seat at the executive table at many organizations, physicians are also being sought for the CEO role at the head of that table.

A commonly referenced study from 2011 by Amanda Goodall, MD, in Social Science & Medicine concluded that, among a cohort of highly ranked hospitals, overall quality metrics were approximately 25% higher in hospitals where a physician was CEO, in comparison to hospitals with non-physician CEOs (2011 Aug;73[4]:535-9). In addition, new positions at both the hospital and health system level are coming into existence: Examples include chief (or VP) of population health, chief innovation officer, chief quality officer, chief patient experience officer, and others.

There is every reason to think that these senior executive physician roles can – and in many cases perhaps should – be filled by hospitalists. Hospital medicine is an ideal “proving ground” for future physician executives and leaders. I believe that the best practitioners of hospital medicine are also the best candidates for hospital, health care, and health system physician executive leadership, because many of the characteristics essential for success as an executive are the same characteristics that are essential for success as a hospitalist. Strong candidates should have the following characteristics:

- A patient-centered perspective. Perhaps the most important characteristic of a leader is empathy. To appreciate the complex, and often (if not usual) challenging emotional states of our patients keeps us connected at the most fundamental, human level to the work we do and to our patients and families. Empathy can – and should – extend to fellow caregivers as well, and allows us to practice and lead teams in the most human of professions. No leader – in health care, anyway – can last long without being able to demonstrate empathy, through words and behavior.

- A systems-based practice: A hospitalist must be able to have a foot in each of two canoes – to be able to see each patient and their family individually and develop preference-based plans of care, and also to be able to focus on process, structure, and outcomes for the hospital system as a whole. The former trait is imbued in us during training and is the critical foundation for the patient-physician relationship. The latter, however, is something different entirely and reflects an ability to have perspective on the entire ecosystem of care – and apply principles of process and quality improvement to achieve forward looking results. That’s leadership.

- Team leadership: Another fundamental attribute of leaders is to assemble a talented and diverse team around an objective, and then to delegate both tasks and their ownership, deferring to expertise. Hospitalists – the best ones, anyway – similarly recognize that for the vast majority of a patient’s hospital stay, the most important caregiver in a patient’s care is someone other than themselves. At any given time, it might be the nurse, aide, pharmacist, care manager, transporter, radiology tech, urologist, housekeeper, surgical resident, or anyone involved in that patient’s care. The hospitalist’s greatest value is in developing the plan of care with the patient and their family, and then communicating – and therefore delegating – that plan to individuals with the expertise to execute that plan. I believe the biggest difficulty hospitalists have in assuming leadership roles is getting out of the comfortable weeds of daily clinical operations and instead focusing on goals, strategies, and teams to accomplish them. The best hospitalists are doing this already as part of their daily care.

- The ability to manage relationships: Hospitalists manage and work among a team of diverse talents. They also often have accountability relationships to a myriad of clinical and administrative leaders in the hospital, each of whom may be in a position of authority to place demands on the hospitalists: A partial list might include the CEO, the chief medical officer, chief nurse, chief of staff, other medical staff departments, academic leaders, and of course, patients and their families. Functioning in a “matrixed” organization – in which lines of authority can go in many directions, depending on the situation – is standard fare, even at the executive level, and the key competency is open and frequent communication.