User login

More cost compression coming

In mid-March, the President released his FY2020 budget proposal. Traditionally, the White House budget has little relation to the ultimate budget since Congress actually creates the final iteration (assuming the government can pass a budget at all). This budget cuts funding for the NIH, Medicare, Medicaid, and most agencies not related to defense, border security, or the TSA. No matter what the final version looks like, the federal deficit will balloon as a result of last year’s tax cuts that were combined with relentless increases in entitlement program spending. The message for health care leaders is clear: Since we are responsible for an enormous percentage of committed federal and state spending, we will be in the cross-hairs of cost compression.

As we enter the 2020 election cycle in earnest, politicians will argue about “Medicare for All” versus government overreach. We will wrestle with competing philosophies of States’ Rights versus Federalism. As physicians, we must advocate for a system of funds flow and regulatory power that we believe best serves our patients within a financially sustainable framework.

On to this month’s issue – there are two stories on early-age colon cancer. A page one story adds to our understanding of the molecular pathways involved (microsatellite instability) and tumor location. Another story points out that younger CRC patients often go undiagnosed or are misdiagnosed. The AGA has published important clinical guidance about pregnancy and IBD and switching from biologic medications to biosimilars. Finally, an enormously important study, published in The Lancet, confirmed that hepatitis C treatment with direct-acting antiviral medications reduces mortality and cancer risk – something we suspected but needed confirmed.

I hope to see everyone at DDW next month.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In mid-March, the President released his FY2020 budget proposal. Traditionally, the White House budget has little relation to the ultimate budget since Congress actually creates the final iteration (assuming the government can pass a budget at all). This budget cuts funding for the NIH, Medicare, Medicaid, and most agencies not related to defense, border security, or the TSA. No matter what the final version looks like, the federal deficit will balloon as a result of last year’s tax cuts that were combined with relentless increases in entitlement program spending. The message for health care leaders is clear: Since we are responsible for an enormous percentage of committed federal and state spending, we will be in the cross-hairs of cost compression.

As we enter the 2020 election cycle in earnest, politicians will argue about “Medicare for All” versus government overreach. We will wrestle with competing philosophies of States’ Rights versus Federalism. As physicians, we must advocate for a system of funds flow and regulatory power that we believe best serves our patients within a financially sustainable framework.

On to this month’s issue – there are two stories on early-age colon cancer. A page one story adds to our understanding of the molecular pathways involved (microsatellite instability) and tumor location. Another story points out that younger CRC patients often go undiagnosed or are misdiagnosed. The AGA has published important clinical guidance about pregnancy and IBD and switching from biologic medications to biosimilars. Finally, an enormously important study, published in The Lancet, confirmed that hepatitis C treatment with direct-acting antiviral medications reduces mortality and cancer risk – something we suspected but needed confirmed.

I hope to see everyone at DDW next month.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In mid-March, the President released his FY2020 budget proposal. Traditionally, the White House budget has little relation to the ultimate budget since Congress actually creates the final iteration (assuming the government can pass a budget at all). This budget cuts funding for the NIH, Medicare, Medicaid, and most agencies not related to defense, border security, or the TSA. No matter what the final version looks like, the federal deficit will balloon as a result of last year’s tax cuts that were combined with relentless increases in entitlement program spending. The message for health care leaders is clear: Since we are responsible for an enormous percentage of committed federal and state spending, we will be in the cross-hairs of cost compression.

As we enter the 2020 election cycle in earnest, politicians will argue about “Medicare for All” versus government overreach. We will wrestle with competing philosophies of States’ Rights versus Federalism. As physicians, we must advocate for a system of funds flow and regulatory power that we believe best serves our patients within a financially sustainable framework.

On to this month’s issue – there are two stories on early-age colon cancer. A page one story adds to our understanding of the molecular pathways involved (microsatellite instability) and tumor location. Another story points out that younger CRC patients often go undiagnosed or are misdiagnosed. The AGA has published important clinical guidance about pregnancy and IBD and switching from biologic medications to biosimilars. Finally, an enormously important study, published in The Lancet, confirmed that hepatitis C treatment with direct-acting antiviral medications reduces mortality and cancer risk – something we suspected but needed confirmed.

I hope to see everyone at DDW next month.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

A.I. and U 2

In a previous Letter from Maine I wrote about a study performed in China in which more than half a million patients were diagnosed by an artificial intelligence (A.I.) system that was able to extract and analyze information from their electronic medical records. The system was at least as accurate as physicians who had access to the same data (“A.I. Shows Promise Assisting Physicians,” by Cade Metz, The New York Times, Feb. 11, 2019). I ended my column with the hopeful assumption that despite incredible advances in A.I., the practice of medicine always would include a human element. However, I left unexplained exactly how physicians would fit into the post-A.I. revolution. In the weeks since I submitted that column, I have been searching for roles that might remain for physicians after A.I. has snatched their bread and butter of diagnosis and management.

I easily can envision a system in which the patient enters her chief complaint and current symptoms into her smartphone or tablet. Using its database of the patient’s past, family, and social history, the system generates a list of laboratory and imaging studies, some of which the patient may be able to submit directly from her handheld device. For example, the system may be able to use the patient’s phone to “examine” her. The A.I. system then generates a diagnosis.

If the diagnosed condition and management is simple and straightforward, such as a rash, the information could be communicated to the patient directly, with a short paragraph of explanation and list of persistent symptoms that would indicate that the condition was not improving as expected. A contact dermatitis comes to mind here.

However, suppose the A.I. system determines that the patient has a 90% chance of having stage IV pancreatic cancer, with a life expectancy of 6 months. Is this the kind of information you would like to learn about yourself by clicking “Your Diagnosis” box on your phone while you were having lunch with a friend? Obviously, a diagnosis of this severity should be communicated human to human, even though it was generated by a highly accurate computer system. And this communication would best be done in the form of a dialogue with someone who knows the patient and has some understanding of how she might understand and cope with the information. In the absence of a prior relationship, the dialogue should occur in real time and face to face at a minimum. I guess we have to acknowledge that FaceTime or Skype might be acceptable here.

Fortunately, stage IV cancers are rare, but there are a bazillion other conditions that, while not serious, require a nuanced explanation as part of a successful management plan that takes into account the patient’s level of anxiety and cognitive abilities. A boilerplate paragraph or two spit out by an A.I. system isn’t good health care. Although I know many physicians do rely on printed handouts for conditions they feel is a no-brainer.

The bottom line is that even when a machine may be better than we are at making some diagnoses, there always will be a role for a human to help other humans understand and cope with those diagnoses. At this point, physicians would appear be the obvious choice to fill that role. How we will get reimbursed for our communication skills is unclear.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a previous Letter from Maine I wrote about a study performed in China in which more than half a million patients were diagnosed by an artificial intelligence (A.I.) system that was able to extract and analyze information from their electronic medical records. The system was at least as accurate as physicians who had access to the same data (“A.I. Shows Promise Assisting Physicians,” by Cade Metz, The New York Times, Feb. 11, 2019). I ended my column with the hopeful assumption that despite incredible advances in A.I., the practice of medicine always would include a human element. However, I left unexplained exactly how physicians would fit into the post-A.I. revolution. In the weeks since I submitted that column, I have been searching for roles that might remain for physicians after A.I. has snatched their bread and butter of diagnosis and management.

I easily can envision a system in which the patient enters her chief complaint and current symptoms into her smartphone or tablet. Using its database of the patient’s past, family, and social history, the system generates a list of laboratory and imaging studies, some of which the patient may be able to submit directly from her handheld device. For example, the system may be able to use the patient’s phone to “examine” her. The A.I. system then generates a diagnosis.

If the diagnosed condition and management is simple and straightforward, such as a rash, the information could be communicated to the patient directly, with a short paragraph of explanation and list of persistent symptoms that would indicate that the condition was not improving as expected. A contact dermatitis comes to mind here.

However, suppose the A.I. system determines that the patient has a 90% chance of having stage IV pancreatic cancer, with a life expectancy of 6 months. Is this the kind of information you would like to learn about yourself by clicking “Your Diagnosis” box on your phone while you were having lunch with a friend? Obviously, a diagnosis of this severity should be communicated human to human, even though it was generated by a highly accurate computer system. And this communication would best be done in the form of a dialogue with someone who knows the patient and has some understanding of how she might understand and cope with the information. In the absence of a prior relationship, the dialogue should occur in real time and face to face at a minimum. I guess we have to acknowledge that FaceTime or Skype might be acceptable here.

Fortunately, stage IV cancers are rare, but there are a bazillion other conditions that, while not serious, require a nuanced explanation as part of a successful management plan that takes into account the patient’s level of anxiety and cognitive abilities. A boilerplate paragraph or two spit out by an A.I. system isn’t good health care. Although I know many physicians do rely on printed handouts for conditions they feel is a no-brainer.

The bottom line is that even when a machine may be better than we are at making some diagnoses, there always will be a role for a human to help other humans understand and cope with those diagnoses. At this point, physicians would appear be the obvious choice to fill that role. How we will get reimbursed for our communication skills is unclear.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a previous Letter from Maine I wrote about a study performed in China in which more than half a million patients were diagnosed by an artificial intelligence (A.I.) system that was able to extract and analyze information from their electronic medical records. The system was at least as accurate as physicians who had access to the same data (“A.I. Shows Promise Assisting Physicians,” by Cade Metz, The New York Times, Feb. 11, 2019). I ended my column with the hopeful assumption that despite incredible advances in A.I., the practice of medicine always would include a human element. However, I left unexplained exactly how physicians would fit into the post-A.I. revolution. In the weeks since I submitted that column, I have been searching for roles that might remain for physicians after A.I. has snatched their bread and butter of diagnosis and management.

I easily can envision a system in which the patient enters her chief complaint and current symptoms into her smartphone or tablet. Using its database of the patient’s past, family, and social history, the system generates a list of laboratory and imaging studies, some of which the patient may be able to submit directly from her handheld device. For example, the system may be able to use the patient’s phone to “examine” her. The A.I. system then generates a diagnosis.

If the diagnosed condition and management is simple and straightforward, such as a rash, the information could be communicated to the patient directly, with a short paragraph of explanation and list of persistent symptoms that would indicate that the condition was not improving as expected. A contact dermatitis comes to mind here.

However, suppose the A.I. system determines that the patient has a 90% chance of having stage IV pancreatic cancer, with a life expectancy of 6 months. Is this the kind of information you would like to learn about yourself by clicking “Your Diagnosis” box on your phone while you were having lunch with a friend? Obviously, a diagnosis of this severity should be communicated human to human, even though it was generated by a highly accurate computer system. And this communication would best be done in the form of a dialogue with someone who knows the patient and has some understanding of how she might understand and cope with the information. In the absence of a prior relationship, the dialogue should occur in real time and face to face at a minimum. I guess we have to acknowledge that FaceTime or Skype might be acceptable here.

Fortunately, stage IV cancers are rare, but there are a bazillion other conditions that, while not serious, require a nuanced explanation as part of a successful management plan that takes into account the patient’s level of anxiety and cognitive abilities. A boilerplate paragraph or two spit out by an A.I. system isn’t good health care. Although I know many physicians do rely on printed handouts for conditions they feel is a no-brainer.

The bottom line is that even when a machine may be better than we are at making some diagnoses, there always will be a role for a human to help other humans understand and cope with those diagnoses. At this point, physicians would appear be the obvious choice to fill that role. How we will get reimbursed for our communication skills is unclear.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Sleeping poorly may mean itching more

Study results showing an association between active atopic dermatitis (AD) and poor sleep quality were published in JAMA Pediatrics by a group of dermatologists at the University of California, San Francisco (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0025). The data on the sleep quality and quantity of nearly 14,000 children were collected over span of 11 years. Of these children, slightly fewer than 5,000 met the researchers’ definition of atopic dermatitis.

Although the sleep duration of children with and without AD was not statistically different, the reports of poor sleep quality and sleep disturbances by children with AD were dramatically more frequent – a nearly 50% higher chance of having more sleep-quality disturbances. In addition, children with more severe active disease were even more likely to report poor sleep quality – almost 80%.

I suspect that you’re not surprised by these findings. You have probably heard numerous tales of poor sleep from families who have children with AD. It just makes sense that a child whose skin is dry and itchy will have trouble sleeping. I’m sure you have struggled to help parents be more diligent about applying moisturizing creams and lotions, and have been aggressive with steroid creams during flare-ups. You may have added sleep onset-promoting antihistamines when topical treatments haven’t been as effective as you had hoped.

Has your working assumption always been that if you can get the child’s skin settled down, the itching will improve and the child will have an easier time falling asleep? But have you ever considered flipping the equation over and tried to be more aggressive in managing the child’s sleep problems?

Like many other folks with psoriasis, I have noticed that my itching is worse when I am tired, and particularly worse in that evil interval between crawling into bed and falling asleep. As the grandparent of a child with AD, I have observed a similar phenomenon. While I am not going to claim that sleep deprivation causes psoriasis or AD, I think that we need to consider the association between poor sleep quality and itching as a feedback loop that must be interrupted. This means that in addition to recommending topicals and moisturizing strategies, we must learn more about our patients’ sleep habits and suggest appropriate sleep hygiene practices.

Many parents aren’t aware of the cruel paradox that an overtired child is more likely to have trouble falling asleep. Has the child been allowed to give up his nap prematurely? Is bedtime at an appropriate hour, and does it consist of a limited number of sleep-promoting rituals? Is the bedroom dark enough, cool enough, and free of electronic distractions?

Providing effective counseling on sleep hygiene is time consuming and requires that you have first convinced the parents that the child’s itching is being aggravated by his sleep deprivation and not just the other way around. Successful management may require a close working relationship between the child’s pediatrician and his dermatologist, with both physicians reinforcing each other’s message that atopic dermatitis isn’t just skin deep.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Is My Child Overtired?: The Sleep Solution for Raising Happier, Healthier Children.” Email him at [email protected].

Study results showing an association between active atopic dermatitis (AD) and poor sleep quality were published in JAMA Pediatrics by a group of dermatologists at the University of California, San Francisco (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0025). The data on the sleep quality and quantity of nearly 14,000 children were collected over span of 11 years. Of these children, slightly fewer than 5,000 met the researchers’ definition of atopic dermatitis.

Although the sleep duration of children with and without AD was not statistically different, the reports of poor sleep quality and sleep disturbances by children with AD were dramatically more frequent – a nearly 50% higher chance of having more sleep-quality disturbances. In addition, children with more severe active disease were even more likely to report poor sleep quality – almost 80%.

I suspect that you’re not surprised by these findings. You have probably heard numerous tales of poor sleep from families who have children with AD. It just makes sense that a child whose skin is dry and itchy will have trouble sleeping. I’m sure you have struggled to help parents be more diligent about applying moisturizing creams and lotions, and have been aggressive with steroid creams during flare-ups. You may have added sleep onset-promoting antihistamines when topical treatments haven’t been as effective as you had hoped.

Has your working assumption always been that if you can get the child’s skin settled down, the itching will improve and the child will have an easier time falling asleep? But have you ever considered flipping the equation over and tried to be more aggressive in managing the child’s sleep problems?

Like many other folks with psoriasis, I have noticed that my itching is worse when I am tired, and particularly worse in that evil interval between crawling into bed and falling asleep. As the grandparent of a child with AD, I have observed a similar phenomenon. While I am not going to claim that sleep deprivation causes psoriasis or AD, I think that we need to consider the association between poor sleep quality and itching as a feedback loop that must be interrupted. This means that in addition to recommending topicals and moisturizing strategies, we must learn more about our patients’ sleep habits and suggest appropriate sleep hygiene practices.

Many parents aren’t aware of the cruel paradox that an overtired child is more likely to have trouble falling asleep. Has the child been allowed to give up his nap prematurely? Is bedtime at an appropriate hour, and does it consist of a limited number of sleep-promoting rituals? Is the bedroom dark enough, cool enough, and free of electronic distractions?

Providing effective counseling on sleep hygiene is time consuming and requires that you have first convinced the parents that the child’s itching is being aggravated by his sleep deprivation and not just the other way around. Successful management may require a close working relationship between the child’s pediatrician and his dermatologist, with both physicians reinforcing each other’s message that atopic dermatitis isn’t just skin deep.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Is My Child Overtired?: The Sleep Solution for Raising Happier, Healthier Children.” Email him at [email protected].

Study results showing an association between active atopic dermatitis (AD) and poor sleep quality were published in JAMA Pediatrics by a group of dermatologists at the University of California, San Francisco (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0025). The data on the sleep quality and quantity of nearly 14,000 children were collected over span of 11 years. Of these children, slightly fewer than 5,000 met the researchers’ definition of atopic dermatitis.

Although the sleep duration of children with and without AD was not statistically different, the reports of poor sleep quality and sleep disturbances by children with AD were dramatically more frequent – a nearly 50% higher chance of having more sleep-quality disturbances. In addition, children with more severe active disease were even more likely to report poor sleep quality – almost 80%.

I suspect that you’re not surprised by these findings. You have probably heard numerous tales of poor sleep from families who have children with AD. It just makes sense that a child whose skin is dry and itchy will have trouble sleeping. I’m sure you have struggled to help parents be more diligent about applying moisturizing creams and lotions, and have been aggressive with steroid creams during flare-ups. You may have added sleep onset-promoting antihistamines when topical treatments haven’t been as effective as you had hoped.

Has your working assumption always been that if you can get the child’s skin settled down, the itching will improve and the child will have an easier time falling asleep? But have you ever considered flipping the equation over and tried to be more aggressive in managing the child’s sleep problems?

Like many other folks with psoriasis, I have noticed that my itching is worse when I am tired, and particularly worse in that evil interval between crawling into bed and falling asleep. As the grandparent of a child with AD, I have observed a similar phenomenon. While I am not going to claim that sleep deprivation causes psoriasis or AD, I think that we need to consider the association between poor sleep quality and itching as a feedback loop that must be interrupted. This means that in addition to recommending topicals and moisturizing strategies, we must learn more about our patients’ sleep habits and suggest appropriate sleep hygiene practices.

Many parents aren’t aware of the cruel paradox that an overtired child is more likely to have trouble falling asleep. Has the child been allowed to give up his nap prematurely? Is bedtime at an appropriate hour, and does it consist of a limited number of sleep-promoting rituals? Is the bedroom dark enough, cool enough, and free of electronic distractions?

Providing effective counseling on sleep hygiene is time consuming and requires that you have first convinced the parents that the child’s itching is being aggravated by his sleep deprivation and not just the other way around. Successful management may require a close working relationship between the child’s pediatrician and his dermatologist, with both physicians reinforcing each other’s message that atopic dermatitis isn’t just skin deep.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Is My Child Overtired?: The Sleep Solution for Raising Happier, Healthier Children.” Email him at [email protected].

Implementation of a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

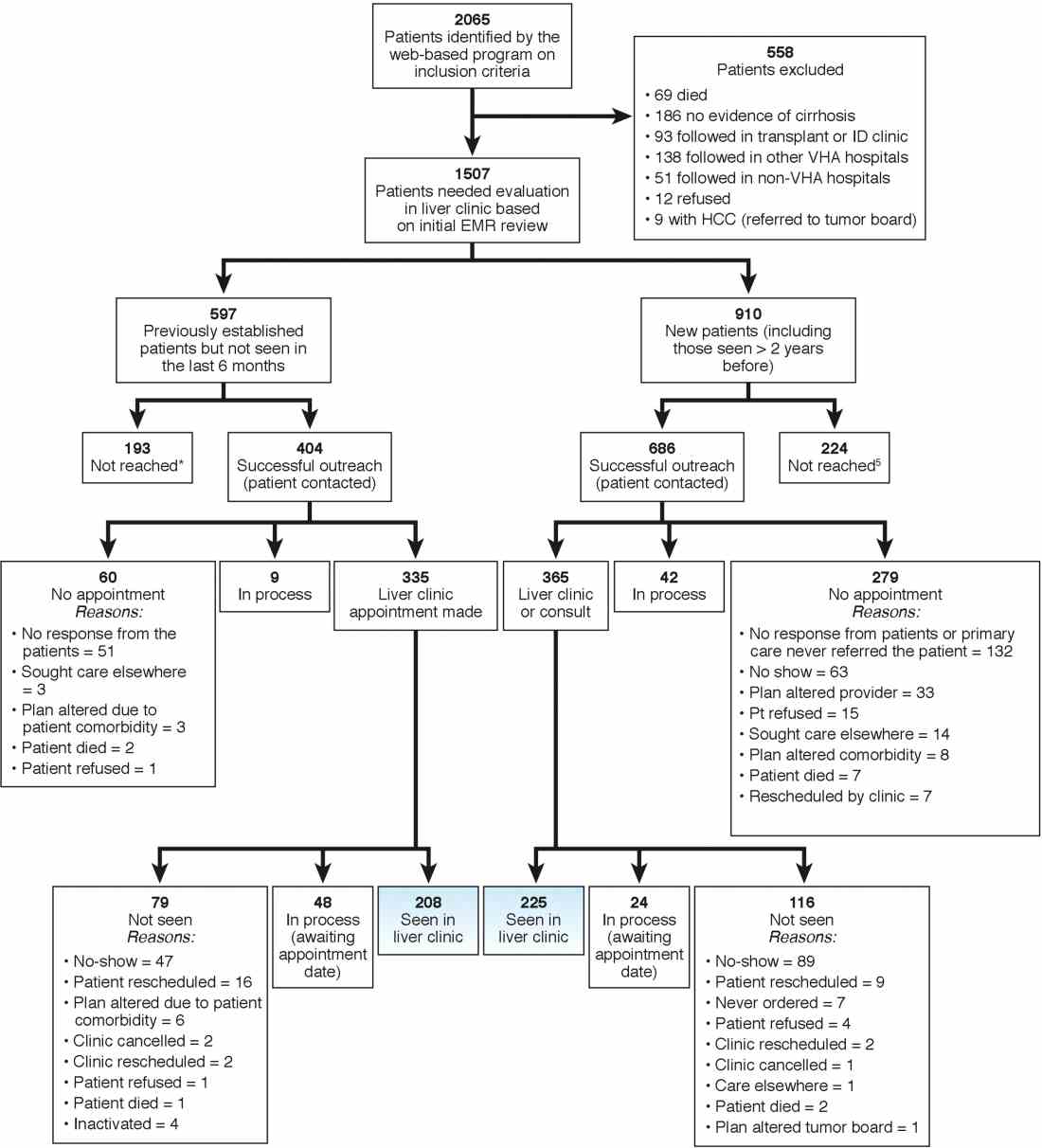

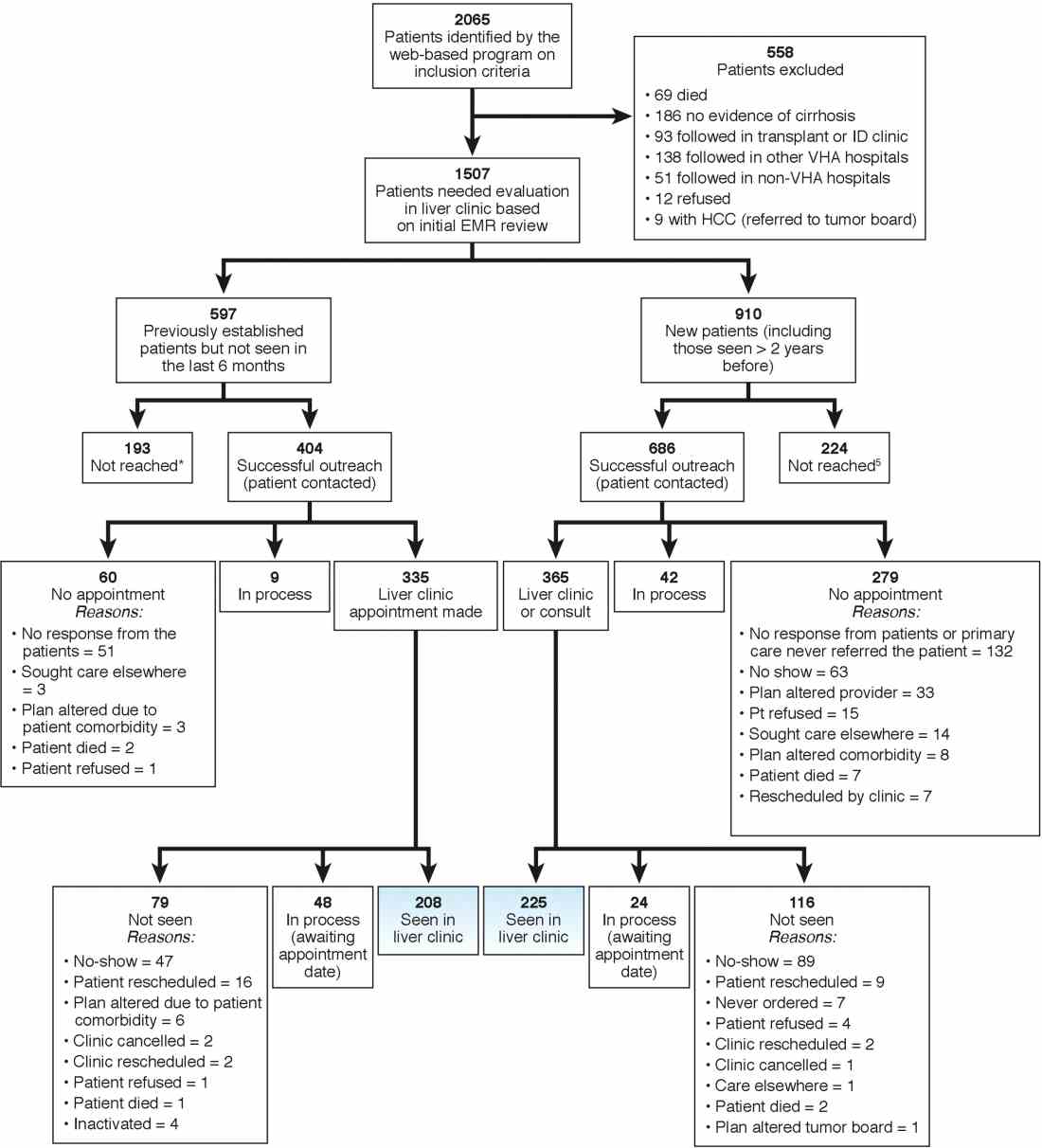

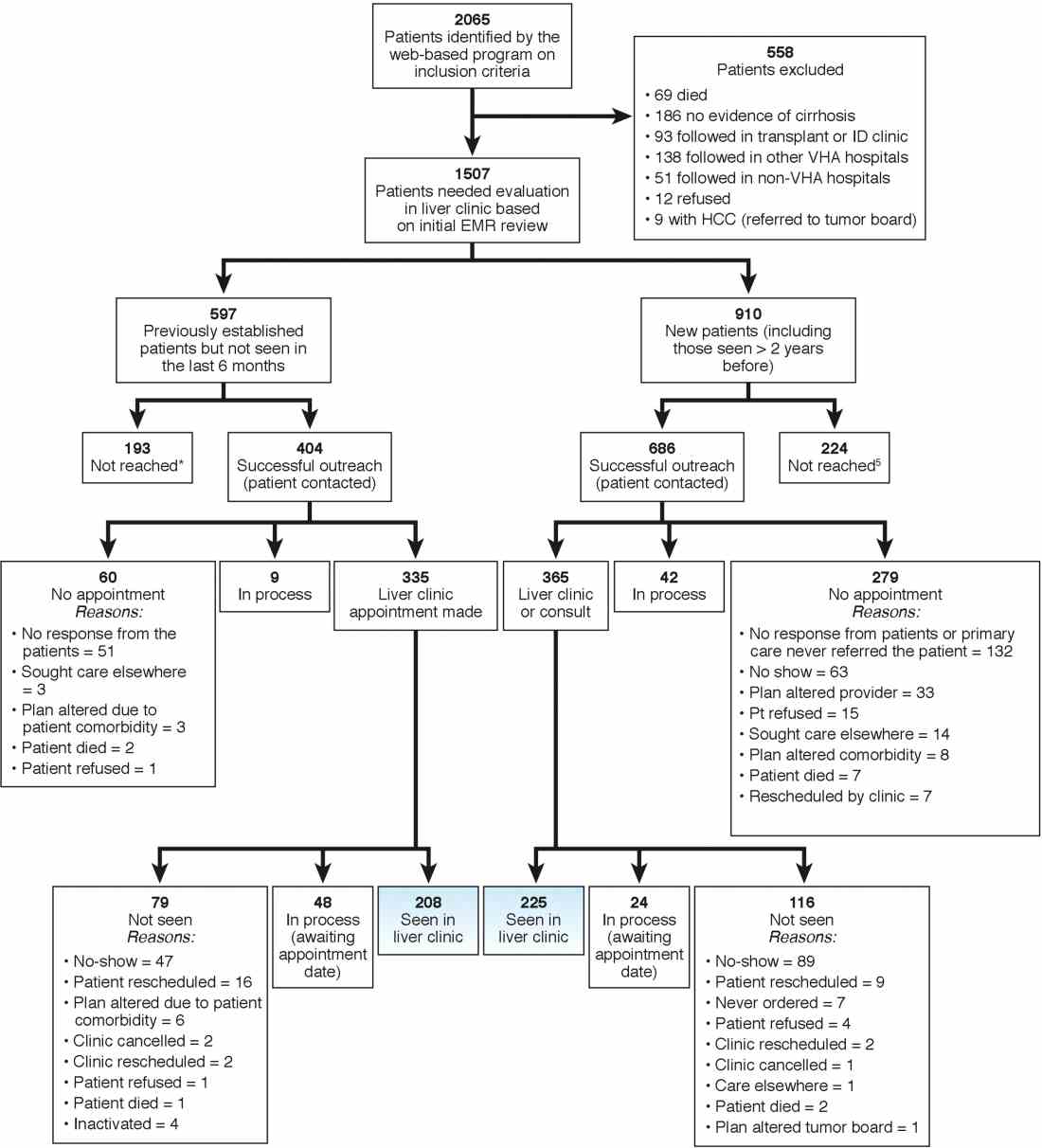

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.

We found several barriers to successful linkage and identified possible solutions. Our results suggest that a direct outreach to patients (without going through PCP) may result in fewer failures to linkage. In total, about 35% of patients who were contacted directly by the liver clinic met the endpoint compared with about 25% of patients who were contacted via their PCP. Future iterations of P-CIMS will rely on direct outreach for most patients. We also found that many patients were unable to keep scheduled appointments; some of this was because of inability to come on specific days and times. Open-access clinics may be one way to accommodate these high-risk patients. Although a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this report, annual cost of maintaining P-CIMS was less than $100,000 (facilitator and programming support), which is equivalent to antiviral treatment cost of four to five HCV patients, suggesting that P-CIMS (with ability to reach out to hundreds of patients) may indeed be cost effective (if not cost saving).

In summary, we built and successfully implemented a population-based health management system with a structured care coordination strategy to facilitate identification and linkage to care of patients with cirrhosis. Our initial results suggest modest success in managing a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. The next steps include comparing the rates of linkage to specialty care with rates in comparable facilities that did not use the tracker; broadening the scope to ensure patients are retained in care and receive guideline-concordant care over time. We will share these results in a subsequent manuscript. To our knowledge, cirrhosis tracker is the first informatics tool that leverages data from the electronic medical records with other tools and strategies to improve quality of cirrhosis care. We believe that the lessons that we learned can also help inform efforts to design programs that encourage use of administrative data–based risk screeners to identify patients with other chronic conditions who are at risk for suboptimal outcomes.

References

1. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-16.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.

3. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-31.

4. Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, et al. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2842-8.

5. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130:1099-106.

6. Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, et al. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204-7.

7. Taddei T, Hunnibell L, DeLorenzo A, et al. EMR-linked cancer tracker facilitates lung and liver cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:77.

8. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:274-82.

9. Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807-20.

10. Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, et al. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:904-12.

Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Mapakshi is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Centerof Excellence, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Smith is project manager at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Taddei is director of the HCC Initiative, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, associate professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University School of Medicine, director, liver cancer team, Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven Hospital; Dr. Hussain is assistant professor, Baylor College of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Madu is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Duong is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine, health services research, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Cao is a statistical analyst at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Mehta is in Health Services Research at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Dr. El-Serag is Chairman and Professor Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Asch is chief of health service research, director of HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System , Palo Alto, Calif., professor of medicine, primary care and population health, Stanford, Calif.; Dr. Midboe is co-implementation research coordinator, HIV/Hepatitis QUERI, director VA patient safety center of inquiry, HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts. This material is based on work supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, QUERI Program, QUE 15-284, VA HIV, Hepatitis C, and Related Conditions Program, and VA National Center for Patient Safety. The work is also supported in part by the Veterans Administration Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413); Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Tex.; and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.

We found several barriers to successful linkage and identified possible solutions. Our results suggest that a direct outreach to patients (without going through PCP) may result in fewer failures to linkage. In total, about 35% of patients who were contacted directly by the liver clinic met the endpoint compared with about 25% of patients who were contacted via their PCP. Future iterations of P-CIMS will rely on direct outreach for most patients. We also found that many patients were unable to keep scheduled appointments; some of this was because of inability to come on specific days and times. Open-access clinics may be one way to accommodate these high-risk patients. Although a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this report, annual cost of maintaining P-CIMS was less than $100,000 (facilitator and programming support), which is equivalent to antiviral treatment cost of four to five HCV patients, suggesting that P-CIMS (with ability to reach out to hundreds of patients) may indeed be cost effective (if not cost saving).

In summary, we built and successfully implemented a population-based health management system with a structured care coordination strategy to facilitate identification and linkage to care of patients with cirrhosis. Our initial results suggest modest success in managing a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. The next steps include comparing the rates of linkage to specialty care with rates in comparable facilities that did not use the tracker; broadening the scope to ensure patients are retained in care and receive guideline-concordant care over time. We will share these results in a subsequent manuscript. To our knowledge, cirrhosis tracker is the first informatics tool that leverages data from the electronic medical records with other tools and strategies to improve quality of cirrhosis care. We believe that the lessons that we learned can also help inform efforts to design programs that encourage use of administrative data–based risk screeners to identify patients with other chronic conditions who are at risk for suboptimal outcomes.

References

1. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-16.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.

3. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-31.

4. Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, et al. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2842-8.

5. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130:1099-106.

6. Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, et al. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204-7.

7. Taddei T, Hunnibell L, DeLorenzo A, et al. EMR-linked cancer tracker facilitates lung and liver cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:77.

8. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:274-82.

9. Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807-20.

10. Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, et al. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:904-12.

Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Mapakshi is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Centerof Excellence, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Smith is project manager at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Taddei is director of the HCC Initiative, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, associate professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University School of Medicine, director, liver cancer team, Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven Hospital; Dr. Hussain is assistant professor, Baylor College of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Madu is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Duong is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine, health services research, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Cao is a statistical analyst at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Mehta is in Health Services Research at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Dr. El-Serag is Chairman and Professor Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Asch is chief of health service research, director of HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System , Palo Alto, Calif., professor of medicine, primary care and population health, Stanford, Calif.; Dr. Midboe is co-implementation research coordinator, HIV/Hepatitis QUERI, director VA patient safety center of inquiry, HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts. This material is based on work supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, QUERI Program, QUE 15-284, VA HIV, Hepatitis C, and Related Conditions Program, and VA National Center for Patient Safety. The work is also supported in part by the Veterans Administration Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413); Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Tex.; and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.

We found several barriers to successful linkage and identified possible solutions. Our results suggest that a direct outreach to patients (without going through PCP) may result in fewer failures to linkage. In total, about 35% of patients who were contacted directly by the liver clinic met the endpoint compared with about 25% of patients who were contacted via their PCP. Future iterations of P-CIMS will rely on direct outreach for most patients. We also found that many patients were unable to keep scheduled appointments; some of this was because of inability to come on specific days and times. Open-access clinics may be one way to accommodate these high-risk patients. Although a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this report, annual cost of maintaining P-CIMS was less than $100,000 (facilitator and programming support), which is equivalent to antiviral treatment cost of four to five HCV patients, suggesting that P-CIMS (with ability to reach out to hundreds of patients) may indeed be cost effective (if not cost saving).

In summary, we built and successfully implemented a population-based health management system with a structured care coordination strategy to facilitate identification and linkage to care of patients with cirrhosis. Our initial results suggest modest success in managing a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. The next steps include comparing the rates of linkage to specialty care with rates in comparable facilities that did not use the tracker; broadening the scope to ensure patients are retained in care and receive guideline-concordant care over time. We will share these results in a subsequent manuscript. To our knowledge, cirrhosis tracker is the first informatics tool that leverages data from the electronic medical records with other tools and strategies to improve quality of cirrhosis care. We believe that the lessons that we learned can also help inform efforts to design programs that encourage use of administrative data–based risk screeners to identify patients with other chronic conditions who are at risk for suboptimal outcomes.

References

1. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-16.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.

3. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-31.