User login

Remembering the Dead in Unity and Peace

Soldiers’ graves are the greatest preachers of peace.

Albert Schweitzer 1

From the window of my room in the house where I grew up, I could see the American flag flying over Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery. I would ride my bicycle around the paths that divided the grassy sections of graves to the blocks where my father and grandfather were buried. I would stand before the gravesites in a state combining prayer, processing, and remembrance. Carved into my grandfather’s headstone were the 2 world wars he fought in and on my father’s, the 3 conflicts in which he served. I would walk up to their headstones and trace the emblems of belief: the engraved Star of David that marked my grandfather’s grave and the simple cross for my father.

My visits and writing about them may strike some readers as morbid. However, for me, the experience and memories are calming and peaceful, like the cemetery. There was something incredibly comforting about the uniformity of the headstones standing out for miles, mirroring the ranks of soldiers in the wars they commemorated. Yet, as with the men and women who fought each conflict, every grave told a succinct Hemingway-like story of their military career etched in stone. I know now that discrimination in the military segregated even the burial of service members.2 It appeared to my younger self that at least compared to civilian cemeteries with their massive monuments to the wealthy and powerful, there was an egalitarian effect: my master sergeant grandfather’s plot was indistinguishable from that of my colonel father.

Memorial Day and military cemeteries have a shared history. While Veterans Day honors all who have worn the uniform, living and dead, Memorial Day, as its name suggests, remembers those who have died in a broadly conceived line of duty. To emphasize the more solemn character of the holiday, the original name, Decoration Day, was changed to emphasize the reverence of remembrance.3 The first widespread observance of Memorial Day was to commemorate those who perished in the Civil War, which remains the conflict with the highest number of casualties in American history. The first national commemoration occurred at Arlington National Cemetery when 5000 volunteers decorated 20,000 Union and Confederate graves in an act of solidarity and reconciliation. The practice struck a chord in a country beleaguered by war and division.2

National cemeteries also emerged from the grief and gratitude that marked the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln, who gave us the famous US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mission motto, also inaugurated national cemeteries. At the beginning of the Civil War, only Union soldiers who sacrificed their lives to end slavery were entitled to burial. Reflective of the rift that divided the country, Confederate soldiers contended that such divisiveness should not continue unto death and were granted the right to be buried beside those they fought against, united in death and memory.4

Today, the country is more divided than ever: more than a few observers of American culture, including the new popular film Civil War, believe we are on the brink of another civil war.5 While we take their warning seriously, there are still signs of unity amongst the people, like those who followed the war between the states. Recently, in that same national cemetery where I first contemplated these themes, justice, delayed too long, was not entirely denied. A ceremony was held to dedicate 17 headstones to honor the memories of Black World War I Army soldiers who were court-martialed and hanged in the wake of the Houston riots of 1917. As a sign of their dishonor, their headstones listed only their dates and names—nothing of their military service. At the urging of their descendants, the US Army reopened the files and found the verdict to have been racially motivated. They set aside their convictions, gave them honorable discharges for their service in life, and replaced their gravesites with ones that enshrined that respect in death.6

Some reading this column may, like me, have had the profound privilege of participating in a burial at a national cemetery. We recall the stirring mix of pride and loss when the honor guard hands the perfectly folded flag to the bereaved family member and bids farewell to their comrade with a salute. Yet, not all families have this privilege. One of the saddest experiences I recall is when I was in a leadership position at a VA facility and unable to help impoverished families who were denied VA burial benefits or payments to transport their deceased veteran closer to home. That sorrow often turned to thankful relief when a veterans service organization or other community group offered to pay the funerary expenses. Fortunately, like eligibility for VA health care, the criteria for burial benefits have steadily expanded to encompass spouses, adult children, and others who served.7

In a similar display of altruism this Memorial Day, veterans service organizations, Boy Scouts, and volunteers will place a flag on every grave to show that some memories are stronger than death. If you have never seen it, I encourage you to visit a VA or a national cemetery this holiday or, even better, volunteer to place flags. Either way, spend a few moments thankfully remembering that we can all engage in those uniquely American Memorial Day pastimes of barbecues and baseball games because so many served and died to protect our way of life. The epigraph at the beginning of this column is attributed to Albert Schweitzer, the physician-theologian of reverence for life. The news today is full of war and rumors of war.8 Let us all hope that the message is heard around the world so there is no need to build more national cemeteries to remember our veterans.

1. Cohen R. On Omaha Beach today, where’s the comradeship? The New York Times. June 5, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/06/05/world/on-omaha-beach-today-where-s-the-comradeship.html

2. Stillwell B. ‘How decoration day’ became memorial day. Military.com. Published May 12, 2020. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.military.com/holidays/memorial-day/how-decoration-day-became-memorial-day.html

3. The history of Memorial Day. PBS. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/national-memorial-day-concert/memorial-day/history/

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration. Facts: NCA history and development. Updated October 18, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.cem.va.gov/facts/NCA_History_and_Development_1.asp

5. Lerer L. How the movie ‘civil war’ echoes real political anxieties. The New York Times. April 21, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/21/us/politics/civil-war-movie-politics.html

6. VA’s national cemetery administration dedicates new headstones to honor black soldiers, correcting 1917 injustice. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published February 22, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-headstones-black-soldiers-1917-injustice/

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration. Burial benefits. Updated September 27, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.cem.va.gov/burial_benefits/

8. Racker M. Why so many politicians are talking about world war III. Time. November 20, 2023. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://time.com/6336897/israel-war-gaza-world-war-iii/

Soldiers’ graves are the greatest preachers of peace.

Albert Schweitzer 1

From the window of my room in the house where I grew up, I could see the American flag flying over Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery. I would ride my bicycle around the paths that divided the grassy sections of graves to the blocks where my father and grandfather were buried. I would stand before the gravesites in a state combining prayer, processing, and remembrance. Carved into my grandfather’s headstone were the 2 world wars he fought in and on my father’s, the 3 conflicts in which he served. I would walk up to their headstones and trace the emblems of belief: the engraved Star of David that marked my grandfather’s grave and the simple cross for my father.

My visits and writing about them may strike some readers as morbid. However, for me, the experience and memories are calming and peaceful, like the cemetery. There was something incredibly comforting about the uniformity of the headstones standing out for miles, mirroring the ranks of soldiers in the wars they commemorated. Yet, as with the men and women who fought each conflict, every grave told a succinct Hemingway-like story of their military career etched in stone. I know now that discrimination in the military segregated even the burial of service members.2 It appeared to my younger self that at least compared to civilian cemeteries with their massive monuments to the wealthy and powerful, there was an egalitarian effect: my master sergeant grandfather’s plot was indistinguishable from that of my colonel father.

Memorial Day and military cemeteries have a shared history. While Veterans Day honors all who have worn the uniform, living and dead, Memorial Day, as its name suggests, remembers those who have died in a broadly conceived line of duty. To emphasize the more solemn character of the holiday, the original name, Decoration Day, was changed to emphasize the reverence of remembrance.3 The first widespread observance of Memorial Day was to commemorate those who perished in the Civil War, which remains the conflict with the highest number of casualties in American history. The first national commemoration occurred at Arlington National Cemetery when 5000 volunteers decorated 20,000 Union and Confederate graves in an act of solidarity and reconciliation. The practice struck a chord in a country beleaguered by war and division.2

National cemeteries also emerged from the grief and gratitude that marked the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln, who gave us the famous US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mission motto, also inaugurated national cemeteries. At the beginning of the Civil War, only Union soldiers who sacrificed their lives to end slavery were entitled to burial. Reflective of the rift that divided the country, Confederate soldiers contended that such divisiveness should not continue unto death and were granted the right to be buried beside those they fought against, united in death and memory.4

Today, the country is more divided than ever: more than a few observers of American culture, including the new popular film Civil War, believe we are on the brink of another civil war.5 While we take their warning seriously, there are still signs of unity amongst the people, like those who followed the war between the states. Recently, in that same national cemetery where I first contemplated these themes, justice, delayed too long, was not entirely denied. A ceremony was held to dedicate 17 headstones to honor the memories of Black World War I Army soldiers who were court-martialed and hanged in the wake of the Houston riots of 1917. As a sign of their dishonor, their headstones listed only their dates and names—nothing of their military service. At the urging of their descendants, the US Army reopened the files and found the verdict to have been racially motivated. They set aside their convictions, gave them honorable discharges for their service in life, and replaced their gravesites with ones that enshrined that respect in death.6

Some reading this column may, like me, have had the profound privilege of participating in a burial at a national cemetery. We recall the stirring mix of pride and loss when the honor guard hands the perfectly folded flag to the bereaved family member and bids farewell to their comrade with a salute. Yet, not all families have this privilege. One of the saddest experiences I recall is when I was in a leadership position at a VA facility and unable to help impoverished families who were denied VA burial benefits or payments to transport their deceased veteran closer to home. That sorrow often turned to thankful relief when a veterans service organization or other community group offered to pay the funerary expenses. Fortunately, like eligibility for VA health care, the criteria for burial benefits have steadily expanded to encompass spouses, adult children, and others who served.7

In a similar display of altruism this Memorial Day, veterans service organizations, Boy Scouts, and volunteers will place a flag on every grave to show that some memories are stronger than death. If you have never seen it, I encourage you to visit a VA or a national cemetery this holiday or, even better, volunteer to place flags. Either way, spend a few moments thankfully remembering that we can all engage in those uniquely American Memorial Day pastimes of barbecues and baseball games because so many served and died to protect our way of life. The epigraph at the beginning of this column is attributed to Albert Schweitzer, the physician-theologian of reverence for life. The news today is full of war and rumors of war.8 Let us all hope that the message is heard around the world so there is no need to build more national cemeteries to remember our veterans.

Soldiers’ graves are the greatest preachers of peace.

Albert Schweitzer 1

From the window of my room in the house where I grew up, I could see the American flag flying over Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery. I would ride my bicycle around the paths that divided the grassy sections of graves to the blocks where my father and grandfather were buried. I would stand before the gravesites in a state combining prayer, processing, and remembrance. Carved into my grandfather’s headstone were the 2 world wars he fought in and on my father’s, the 3 conflicts in which he served. I would walk up to their headstones and trace the emblems of belief: the engraved Star of David that marked my grandfather’s grave and the simple cross for my father.

My visits and writing about them may strike some readers as morbid. However, for me, the experience and memories are calming and peaceful, like the cemetery. There was something incredibly comforting about the uniformity of the headstones standing out for miles, mirroring the ranks of soldiers in the wars they commemorated. Yet, as with the men and women who fought each conflict, every grave told a succinct Hemingway-like story of their military career etched in stone. I know now that discrimination in the military segregated even the burial of service members.2 It appeared to my younger self that at least compared to civilian cemeteries with their massive monuments to the wealthy and powerful, there was an egalitarian effect: my master sergeant grandfather’s plot was indistinguishable from that of my colonel father.

Memorial Day and military cemeteries have a shared history. While Veterans Day honors all who have worn the uniform, living and dead, Memorial Day, as its name suggests, remembers those who have died in a broadly conceived line of duty. To emphasize the more solemn character of the holiday, the original name, Decoration Day, was changed to emphasize the reverence of remembrance.3 The first widespread observance of Memorial Day was to commemorate those who perished in the Civil War, which remains the conflict with the highest number of casualties in American history. The first national commemoration occurred at Arlington National Cemetery when 5000 volunteers decorated 20,000 Union and Confederate graves in an act of solidarity and reconciliation. The practice struck a chord in a country beleaguered by war and division.2

National cemeteries also emerged from the grief and gratitude that marked the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln, who gave us the famous US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mission motto, also inaugurated national cemeteries. At the beginning of the Civil War, only Union soldiers who sacrificed their lives to end slavery were entitled to burial. Reflective of the rift that divided the country, Confederate soldiers contended that such divisiveness should not continue unto death and were granted the right to be buried beside those they fought against, united in death and memory.4

Today, the country is more divided than ever: more than a few observers of American culture, including the new popular film Civil War, believe we are on the brink of another civil war.5 While we take their warning seriously, there are still signs of unity amongst the people, like those who followed the war between the states. Recently, in that same national cemetery where I first contemplated these themes, justice, delayed too long, was not entirely denied. A ceremony was held to dedicate 17 headstones to honor the memories of Black World War I Army soldiers who were court-martialed and hanged in the wake of the Houston riots of 1917. As a sign of their dishonor, their headstones listed only their dates and names—nothing of their military service. At the urging of their descendants, the US Army reopened the files and found the verdict to have been racially motivated. They set aside their convictions, gave them honorable discharges for their service in life, and replaced their gravesites with ones that enshrined that respect in death.6

Some reading this column may, like me, have had the profound privilege of participating in a burial at a national cemetery. We recall the stirring mix of pride and loss when the honor guard hands the perfectly folded flag to the bereaved family member and bids farewell to their comrade with a salute. Yet, not all families have this privilege. One of the saddest experiences I recall is when I was in a leadership position at a VA facility and unable to help impoverished families who were denied VA burial benefits or payments to transport their deceased veteran closer to home. That sorrow often turned to thankful relief when a veterans service organization or other community group offered to pay the funerary expenses. Fortunately, like eligibility for VA health care, the criteria for burial benefits have steadily expanded to encompass spouses, adult children, and others who served.7

In a similar display of altruism this Memorial Day, veterans service organizations, Boy Scouts, and volunteers will place a flag on every grave to show that some memories are stronger than death. If you have never seen it, I encourage you to visit a VA or a national cemetery this holiday or, even better, volunteer to place flags. Either way, spend a few moments thankfully remembering that we can all engage in those uniquely American Memorial Day pastimes of barbecues and baseball games because so many served and died to protect our way of life. The epigraph at the beginning of this column is attributed to Albert Schweitzer, the physician-theologian of reverence for life. The news today is full of war and rumors of war.8 Let us all hope that the message is heard around the world so there is no need to build more national cemeteries to remember our veterans.

1. Cohen R. On Omaha Beach today, where’s the comradeship? The New York Times. June 5, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/06/05/world/on-omaha-beach-today-where-s-the-comradeship.html

2. Stillwell B. ‘How decoration day’ became memorial day. Military.com. Published May 12, 2020. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.military.com/holidays/memorial-day/how-decoration-day-became-memorial-day.html

3. The history of Memorial Day. PBS. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/national-memorial-day-concert/memorial-day/history/

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration. Facts: NCA history and development. Updated October 18, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.cem.va.gov/facts/NCA_History_and_Development_1.asp

5. Lerer L. How the movie ‘civil war’ echoes real political anxieties. The New York Times. April 21, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/21/us/politics/civil-war-movie-politics.html

6. VA’s national cemetery administration dedicates new headstones to honor black soldiers, correcting 1917 injustice. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published February 22, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-headstones-black-soldiers-1917-injustice/

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration. Burial benefits. Updated September 27, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.cem.va.gov/burial_benefits/

8. Racker M. Why so many politicians are talking about world war III. Time. November 20, 2023. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://time.com/6336897/israel-war-gaza-world-war-iii/

1. Cohen R. On Omaha Beach today, where’s the comradeship? The New York Times. June 5, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/06/05/world/on-omaha-beach-today-where-s-the-comradeship.html

2. Stillwell B. ‘How decoration day’ became memorial day. Military.com. Published May 12, 2020. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.military.com/holidays/memorial-day/how-decoration-day-became-memorial-day.html

3. The history of Memorial Day. PBS. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/national-memorial-day-concert/memorial-day/history/

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration. Facts: NCA history and development. Updated October 18, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.cem.va.gov/facts/NCA_History_and_Development_1.asp

5. Lerer L. How the movie ‘civil war’ echoes real political anxieties. The New York Times. April 21, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/21/us/politics/civil-war-movie-politics.html

6. VA’s national cemetery administration dedicates new headstones to honor black soldiers, correcting 1917 injustice. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published February 22, 2024. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-headstones-black-soldiers-1917-injustice/

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration. Burial benefits. Updated September 27, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.cem.va.gov/burial_benefits/

8. Racker M. Why so many politicians are talking about world war III. Time. November 20, 2023. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://time.com/6336897/israel-war-gaza-world-war-iii/

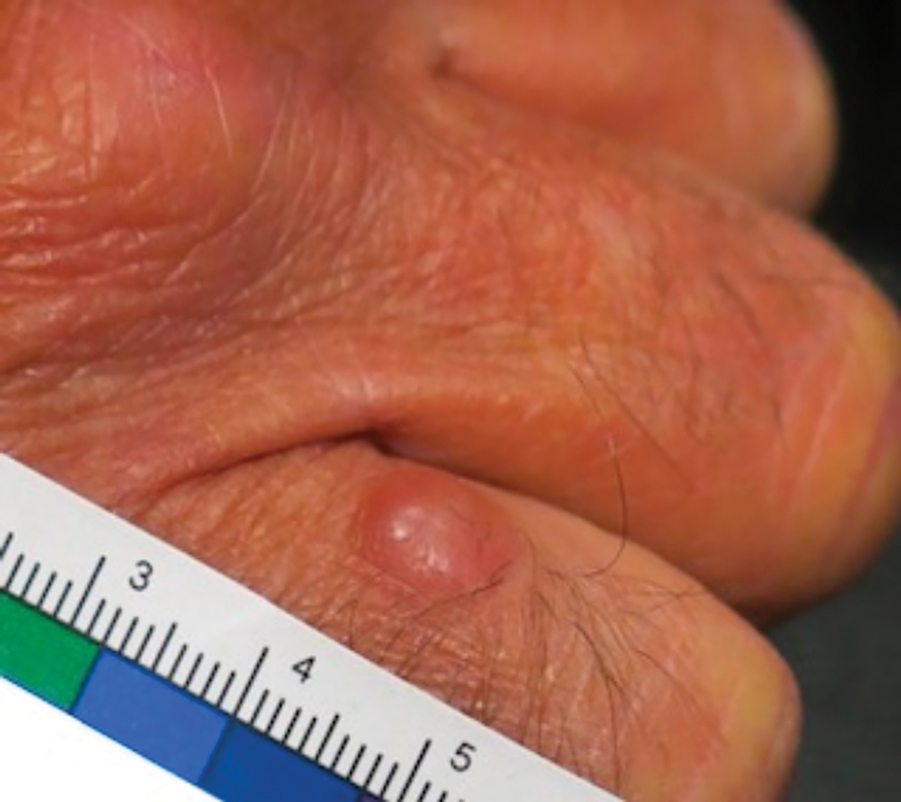

Multiple Asymptomatic Dome-Shaped Papules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

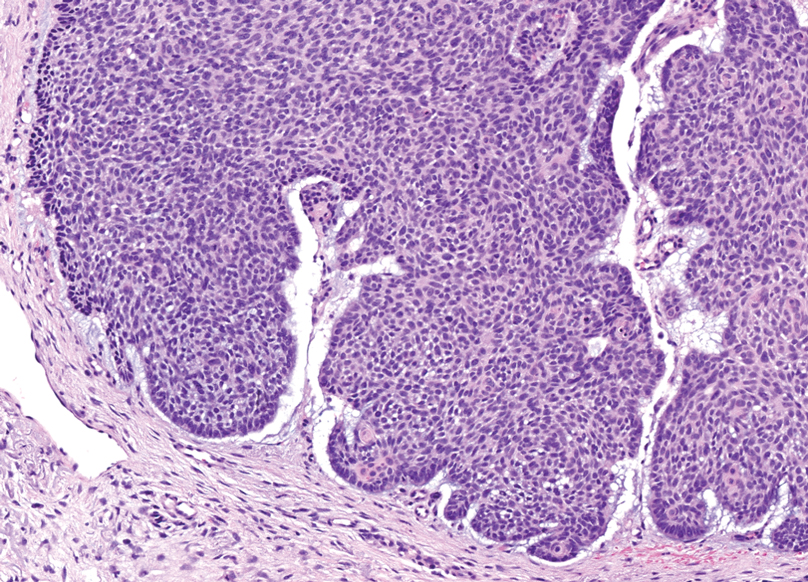

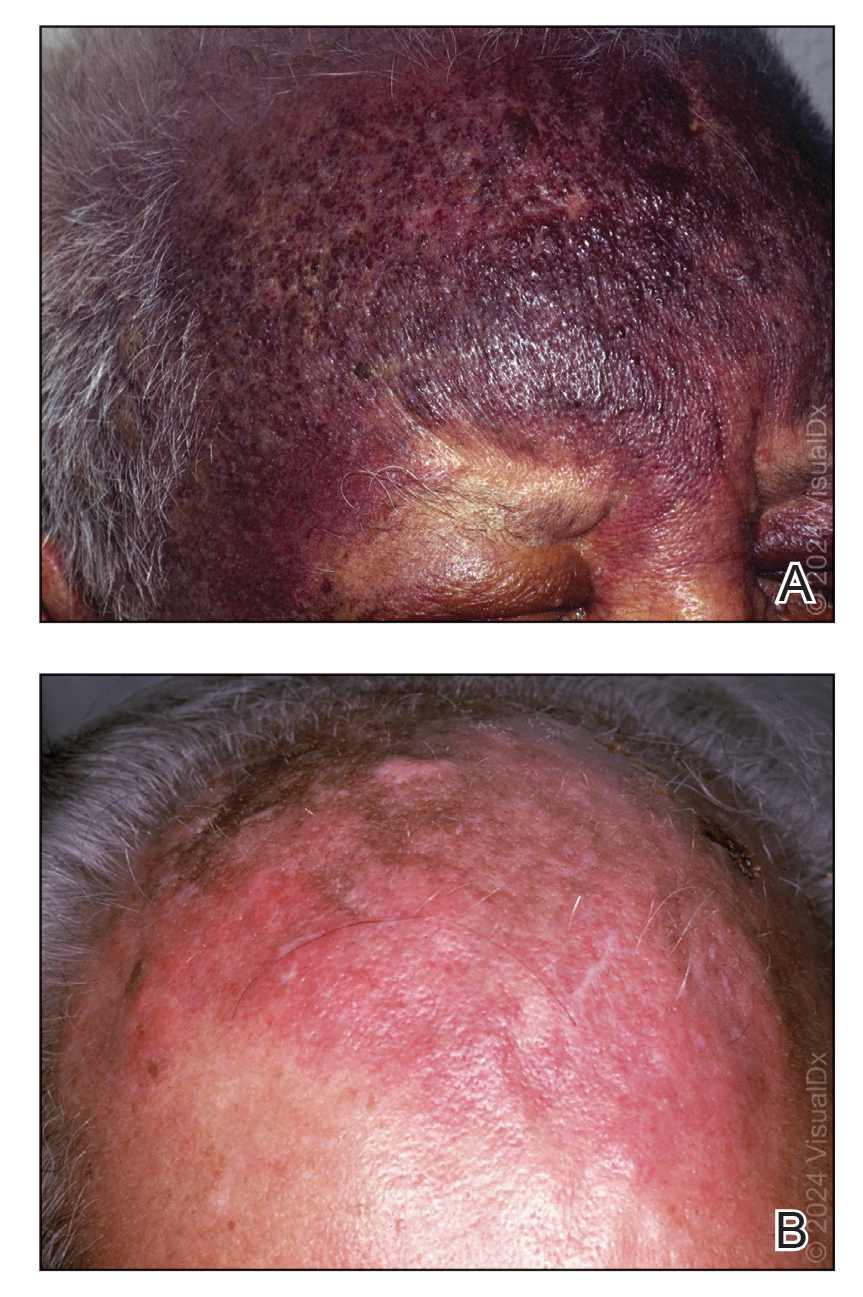

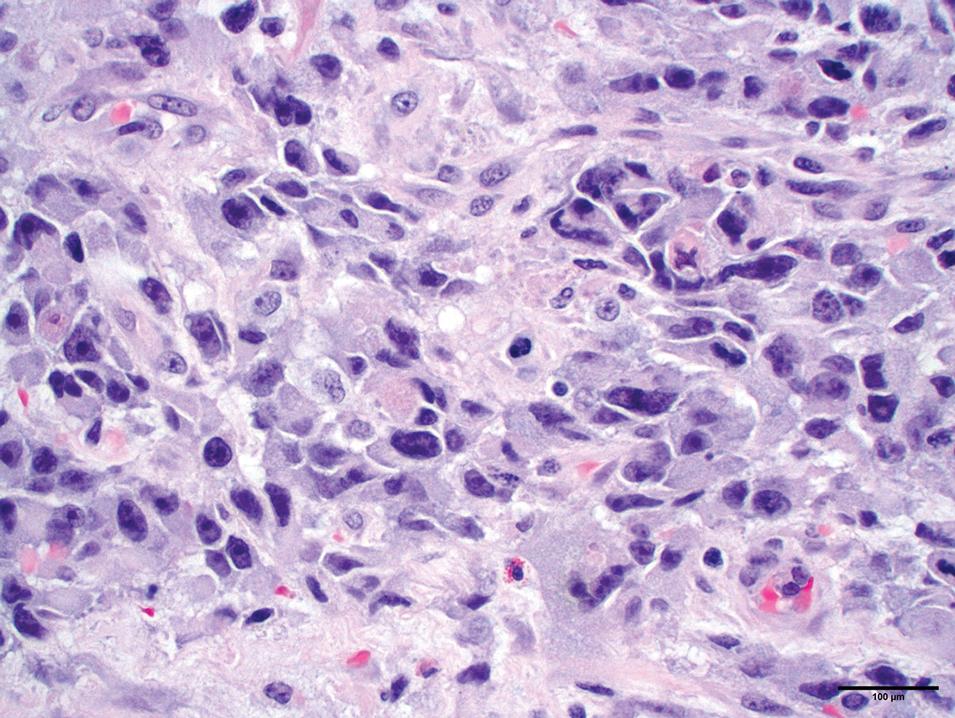

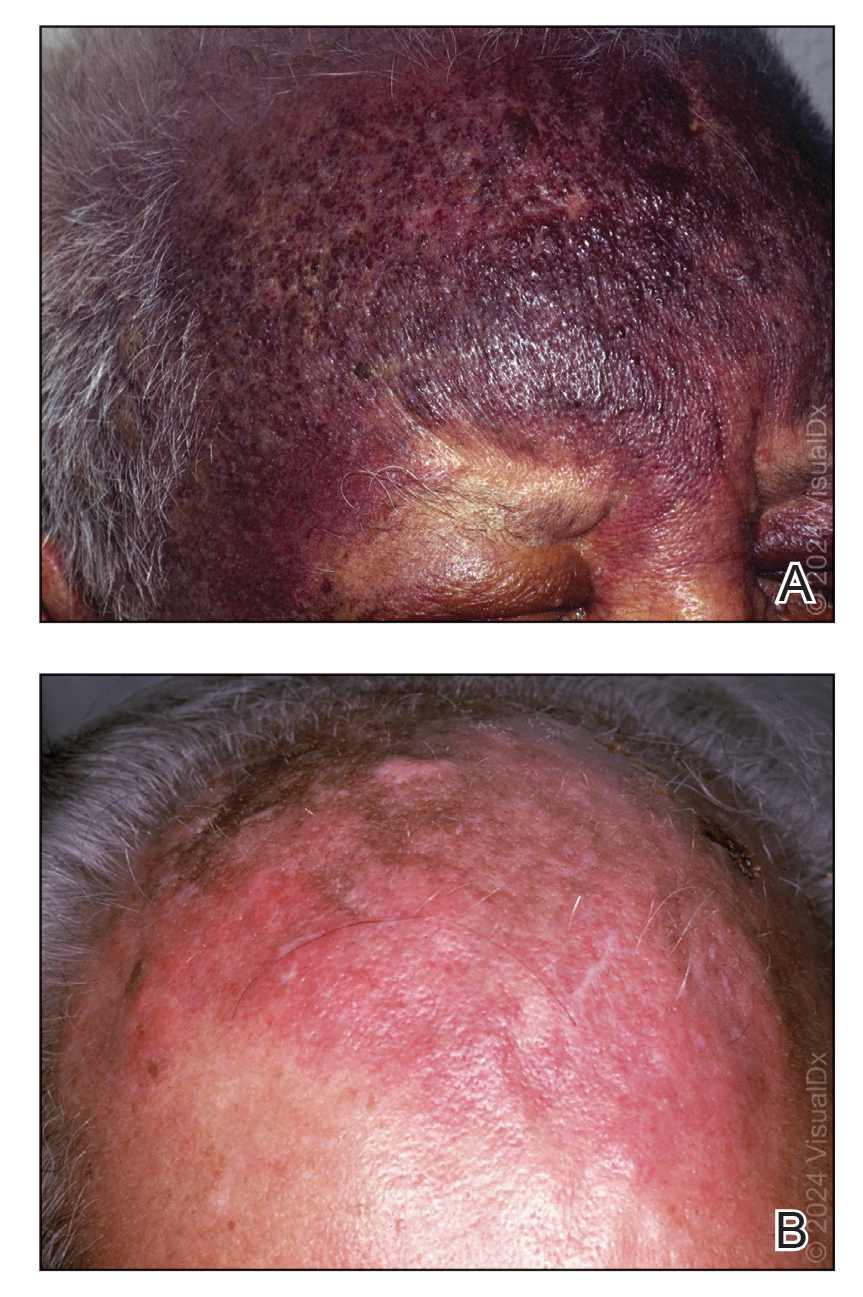

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

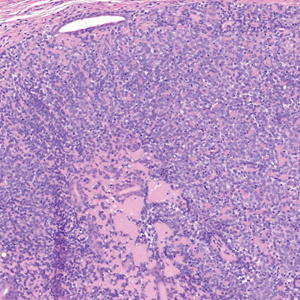

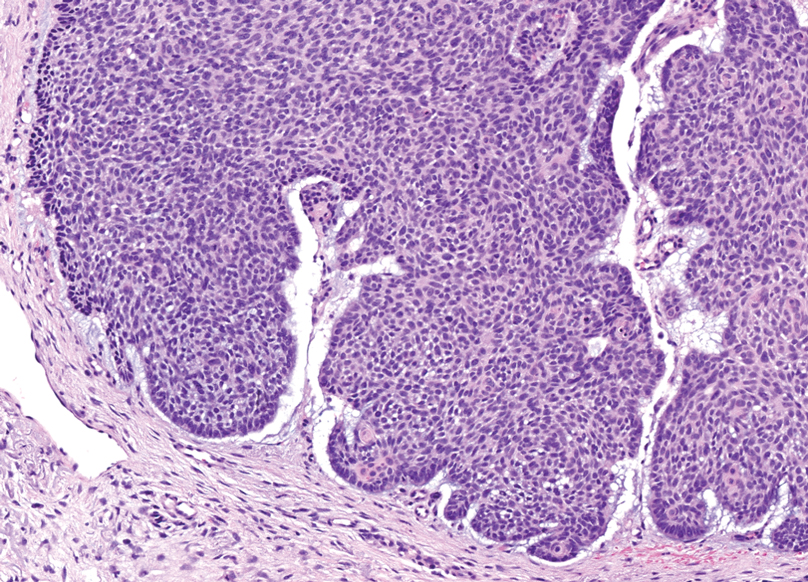

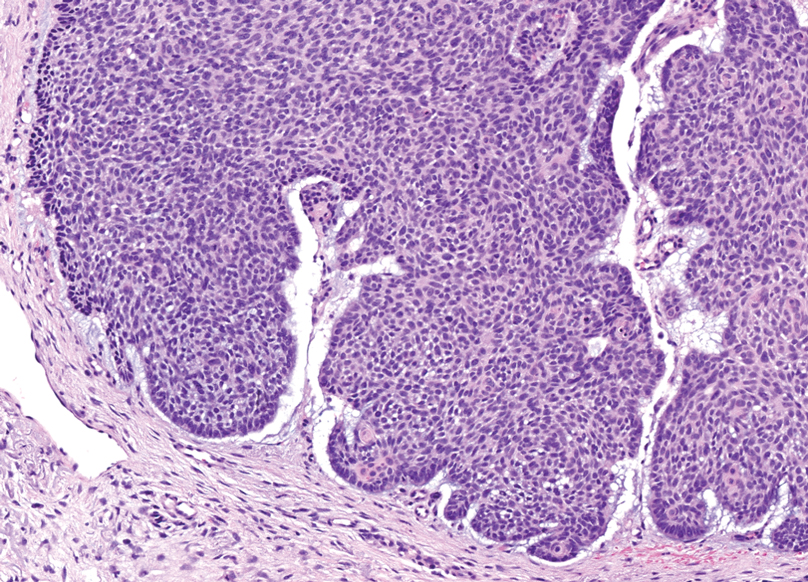

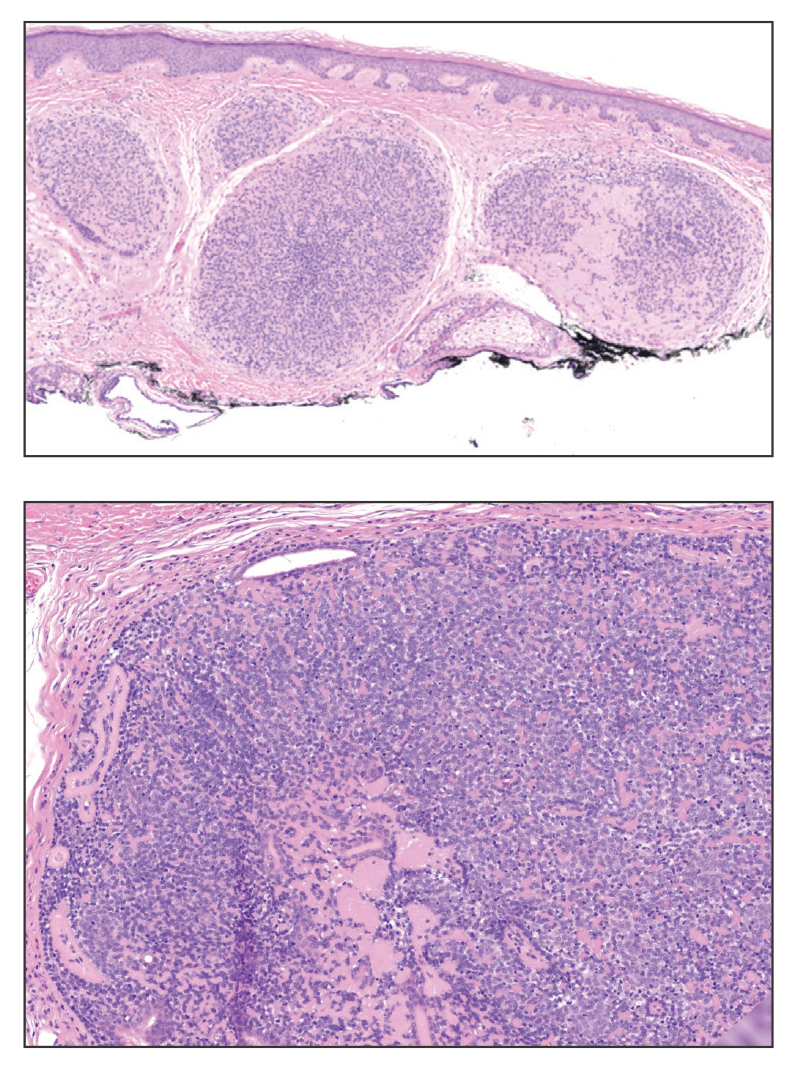

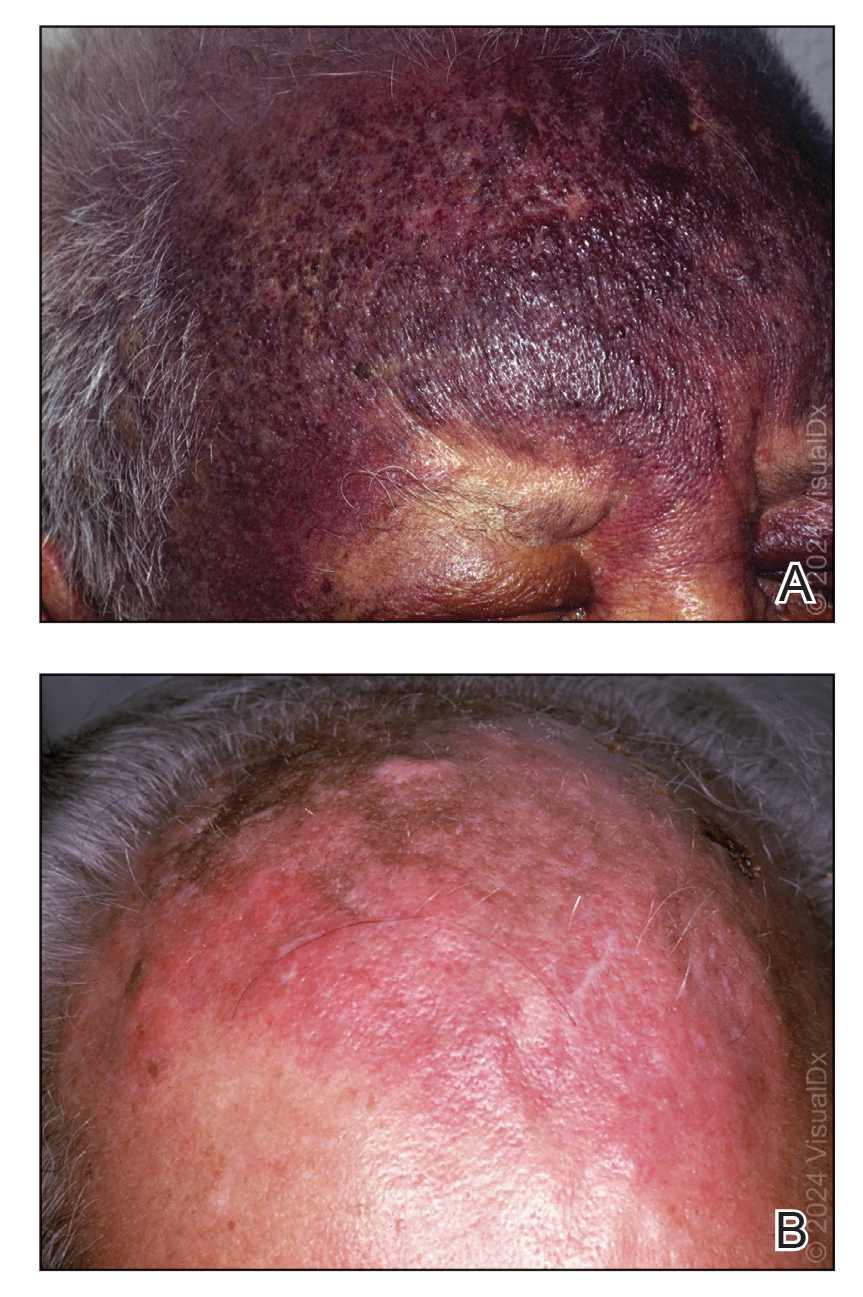

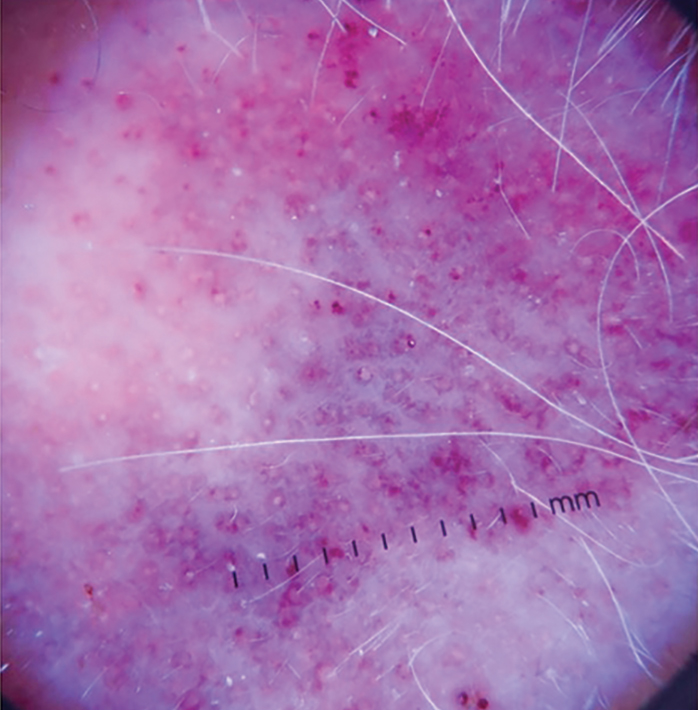

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

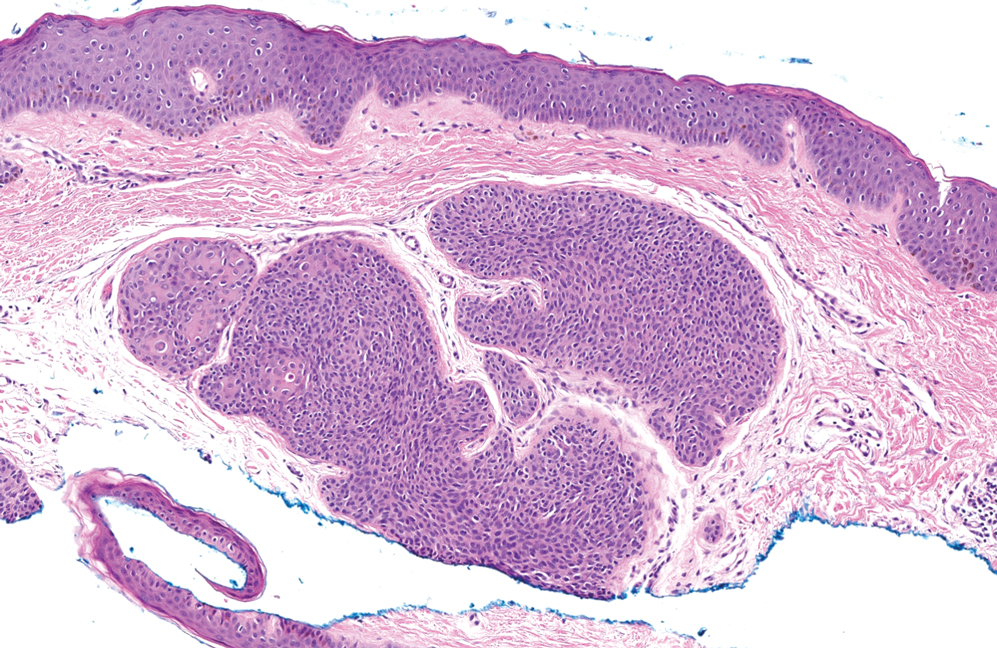

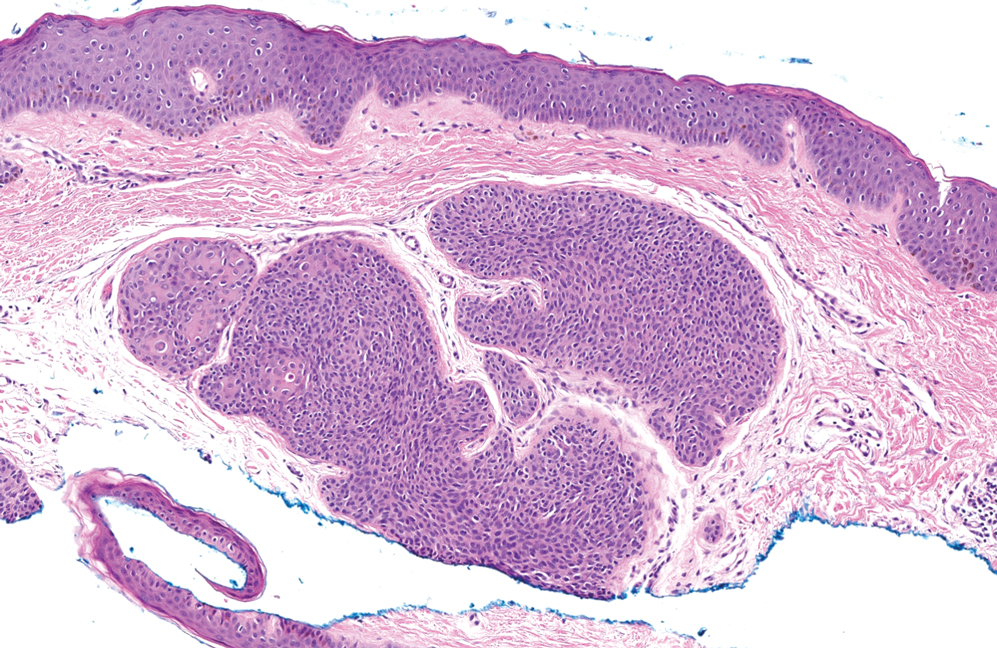

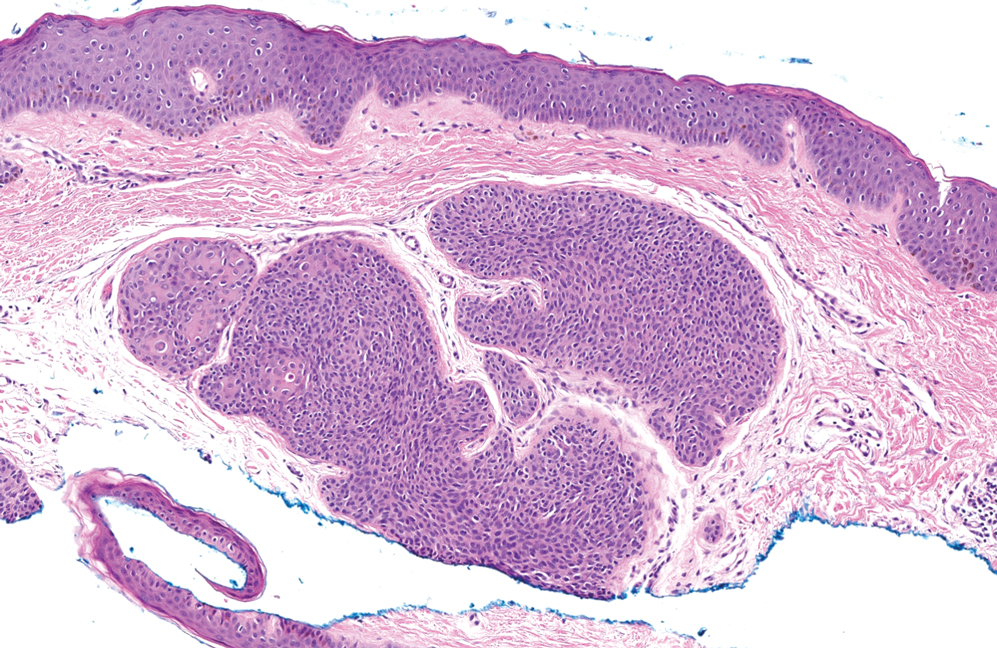

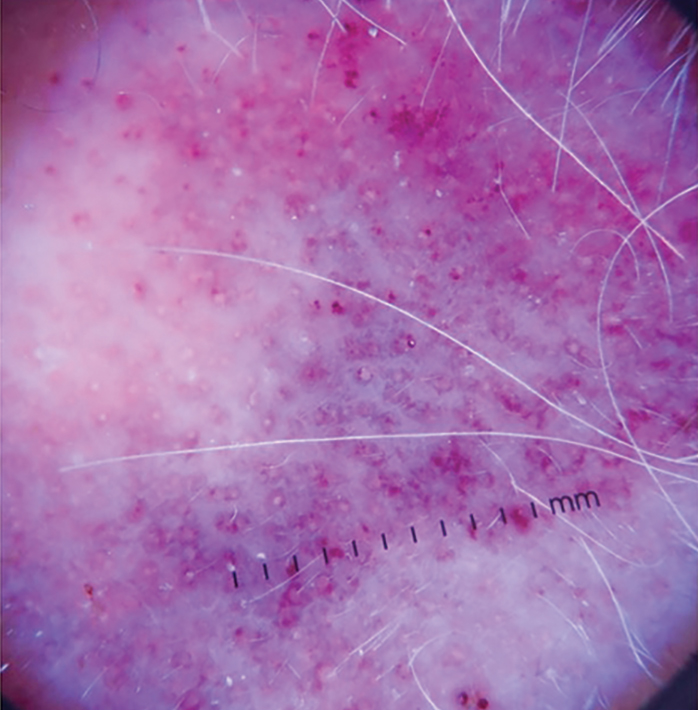

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

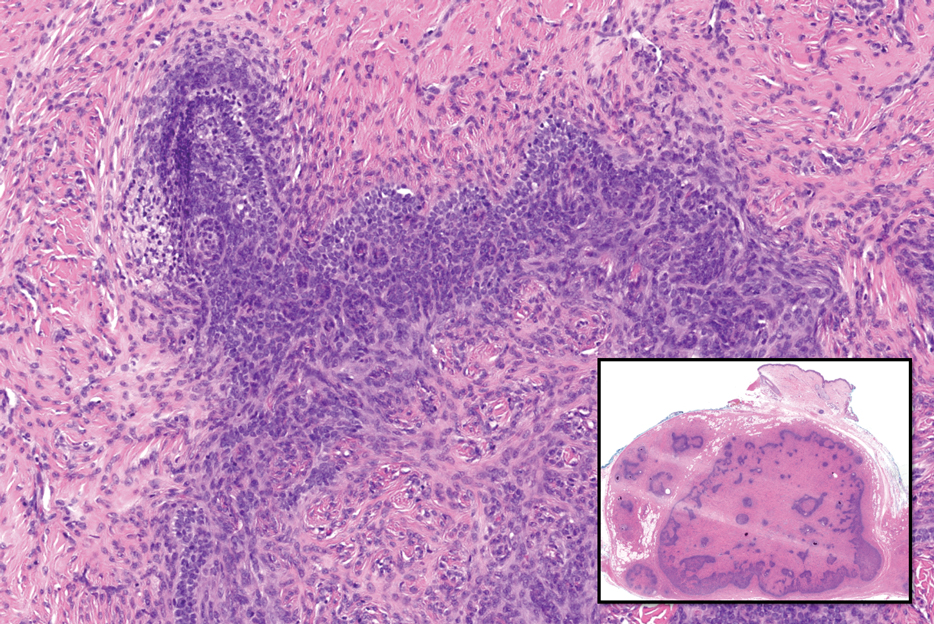

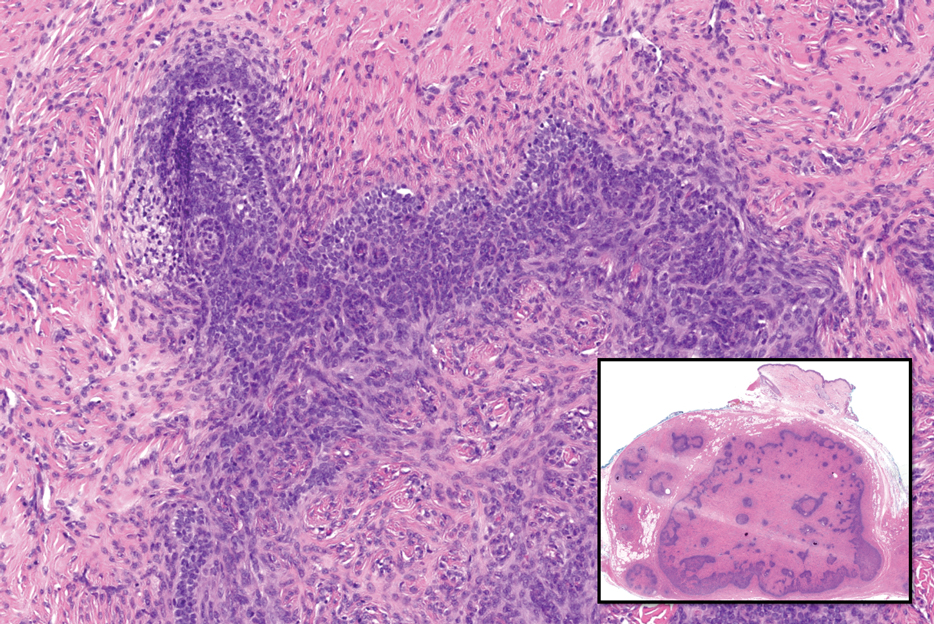

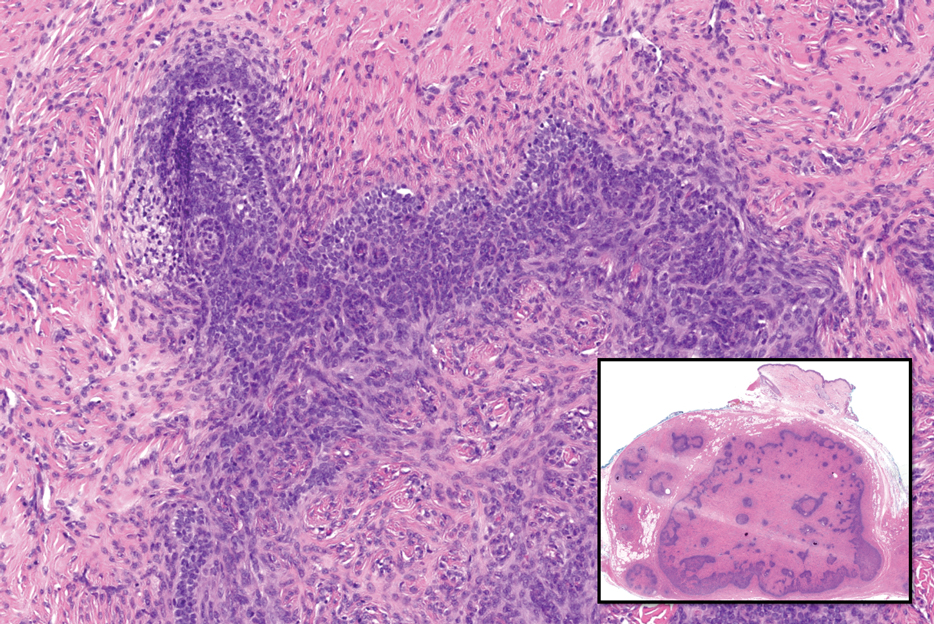

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

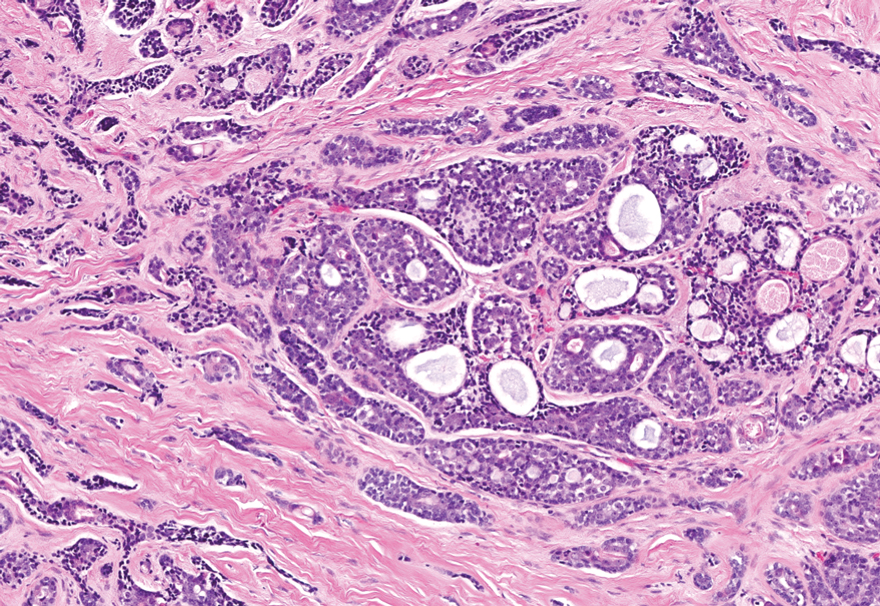

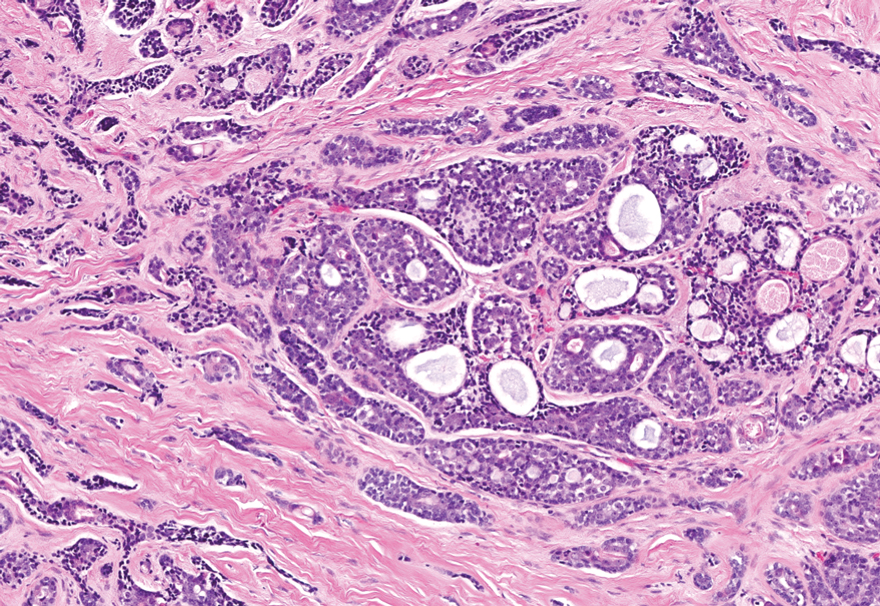

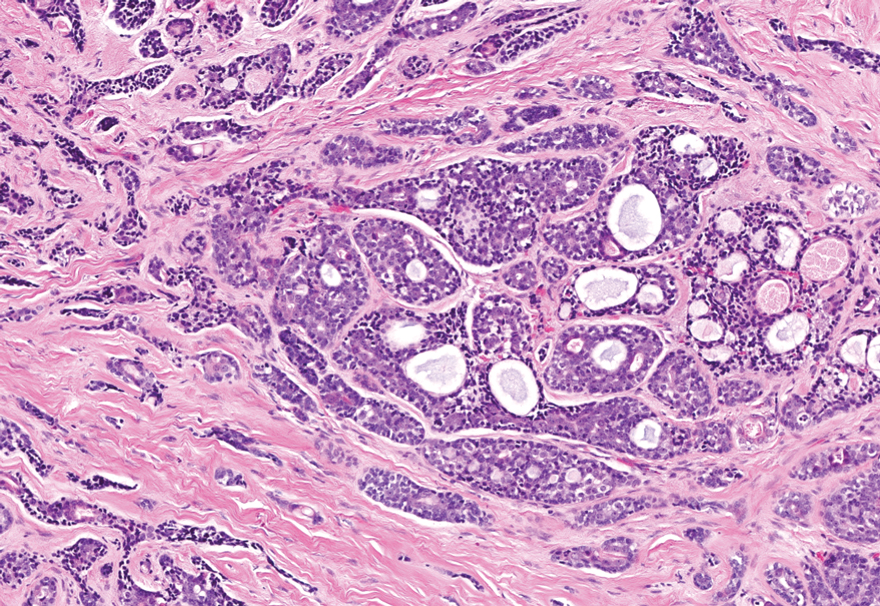

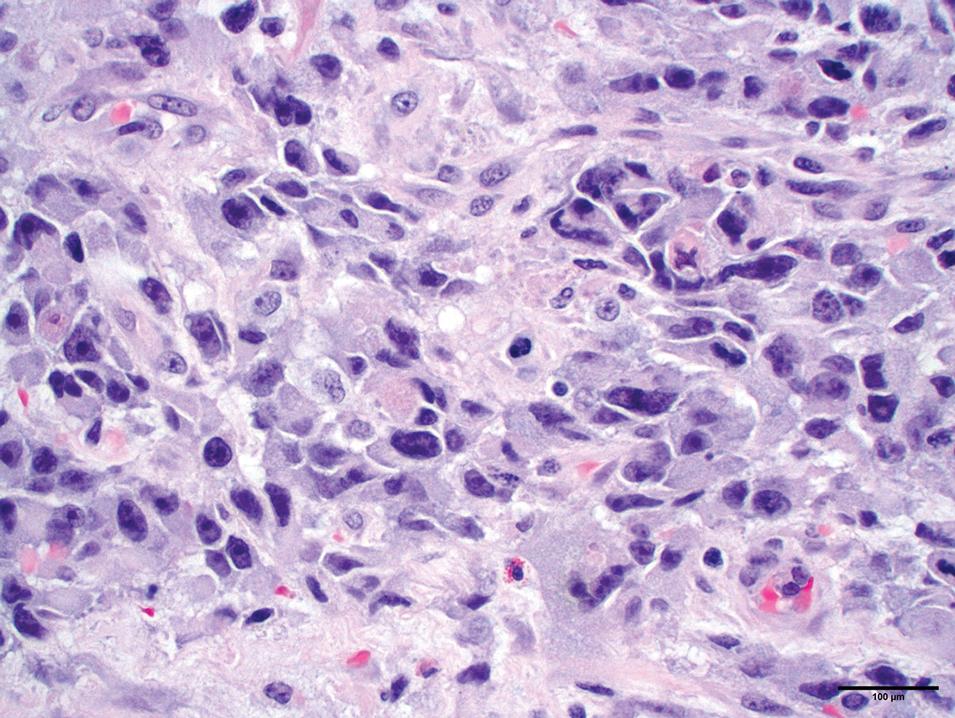

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

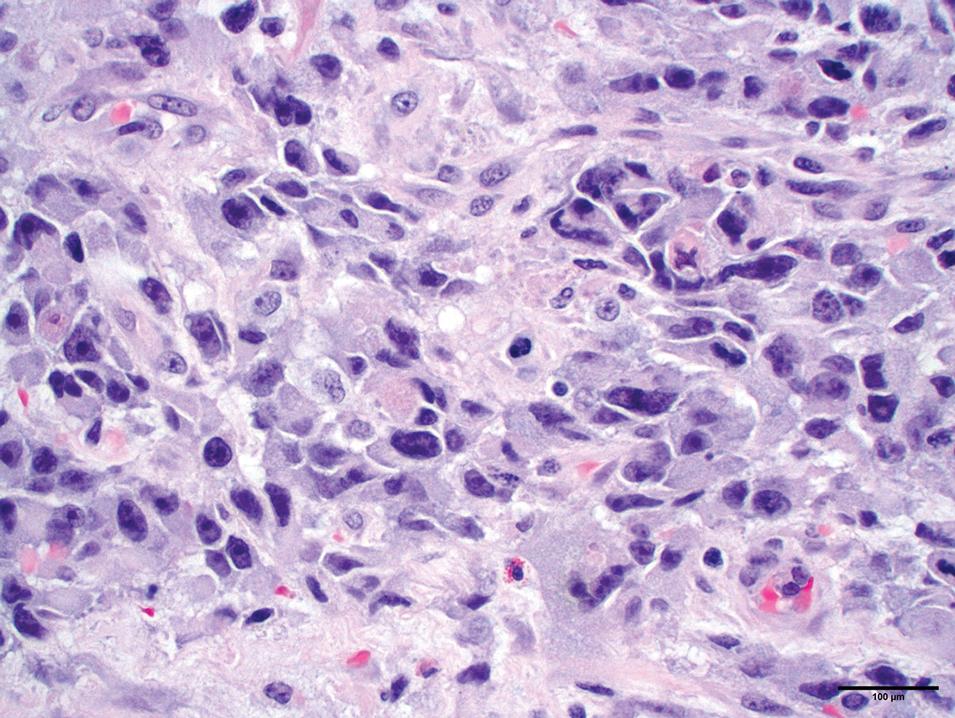

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

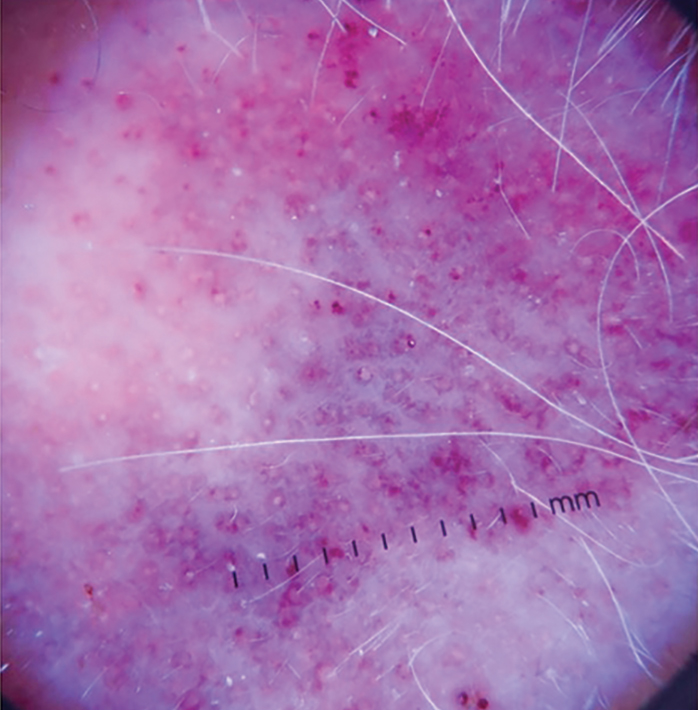

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

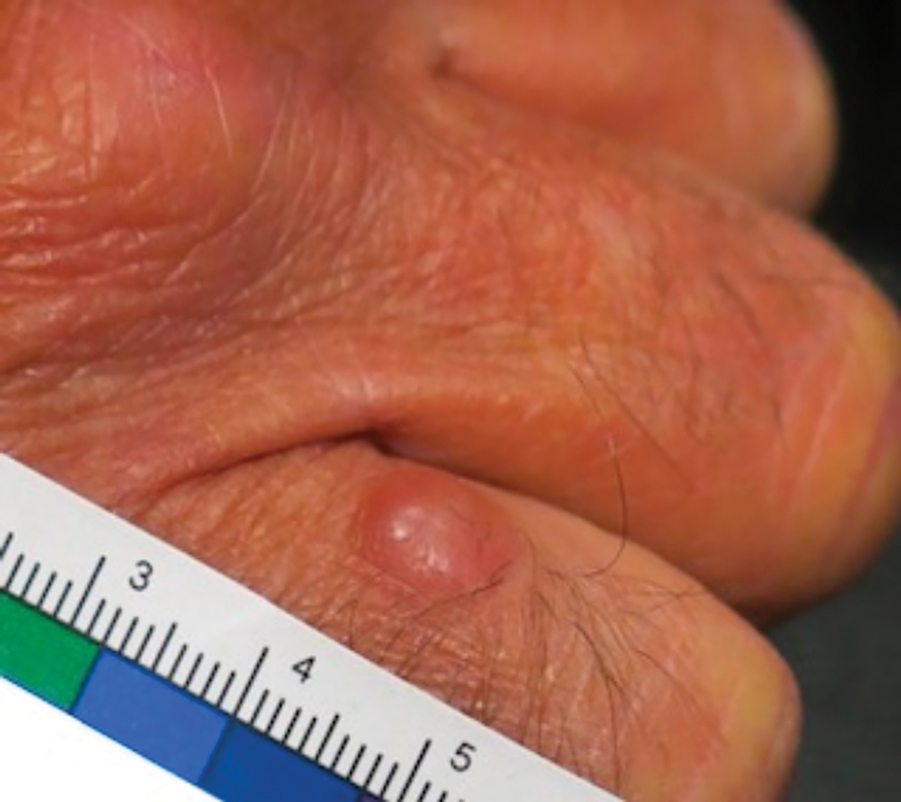

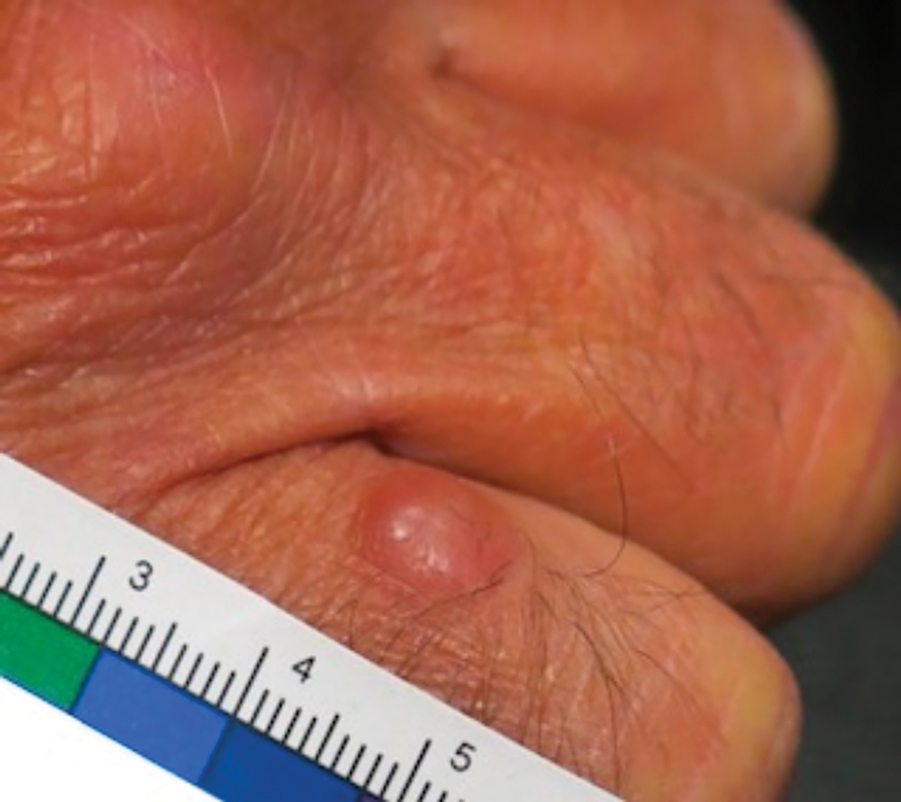

A 62-year-old man with a history of cylindromas presented to our clinic with multiple asymptomatic, 3- to 4-mm, nonmobile, dome-shaped, telangiectatic, pink papules over the parietal and vertex scalp that had been present for more than 10 years without change. Several family members had similar lesions that had not been evaluated by a physician, and there had been no genetic evaluation. Shave biopsies of several lesions were performed.

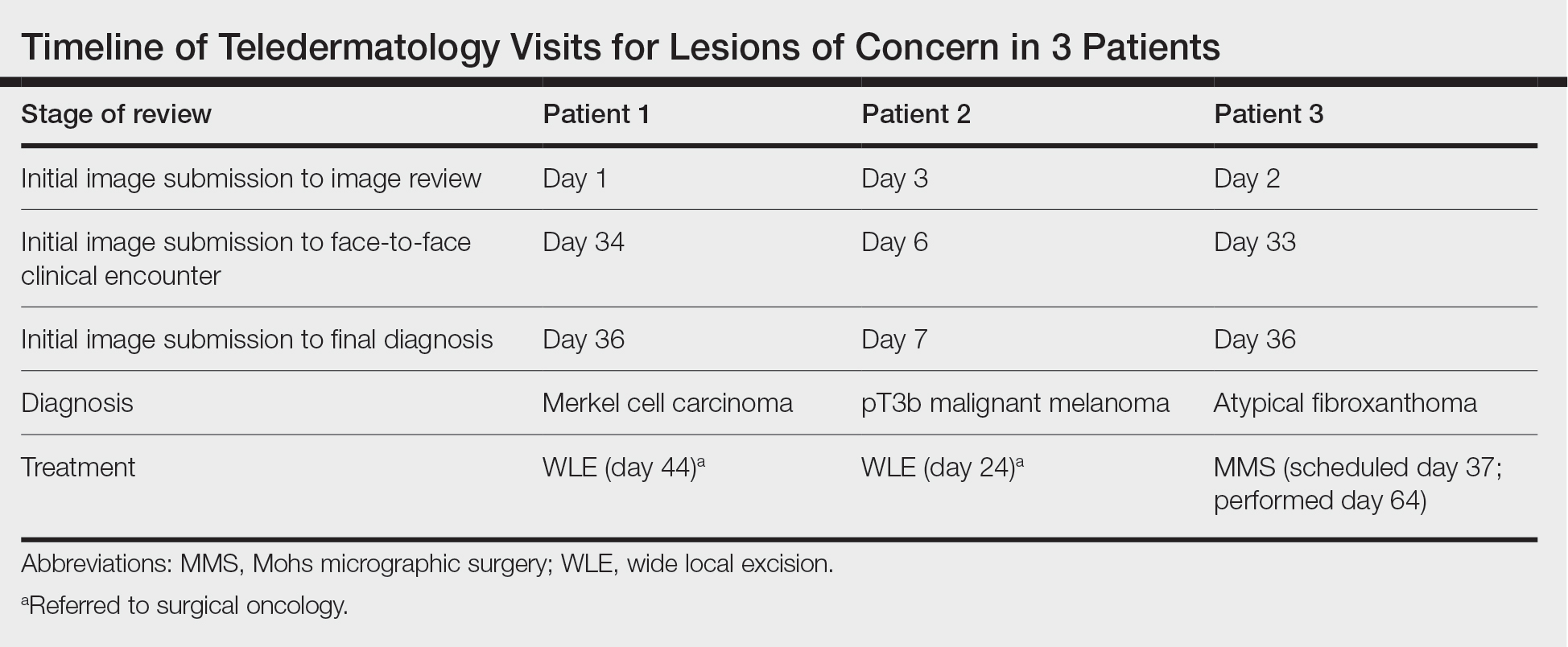

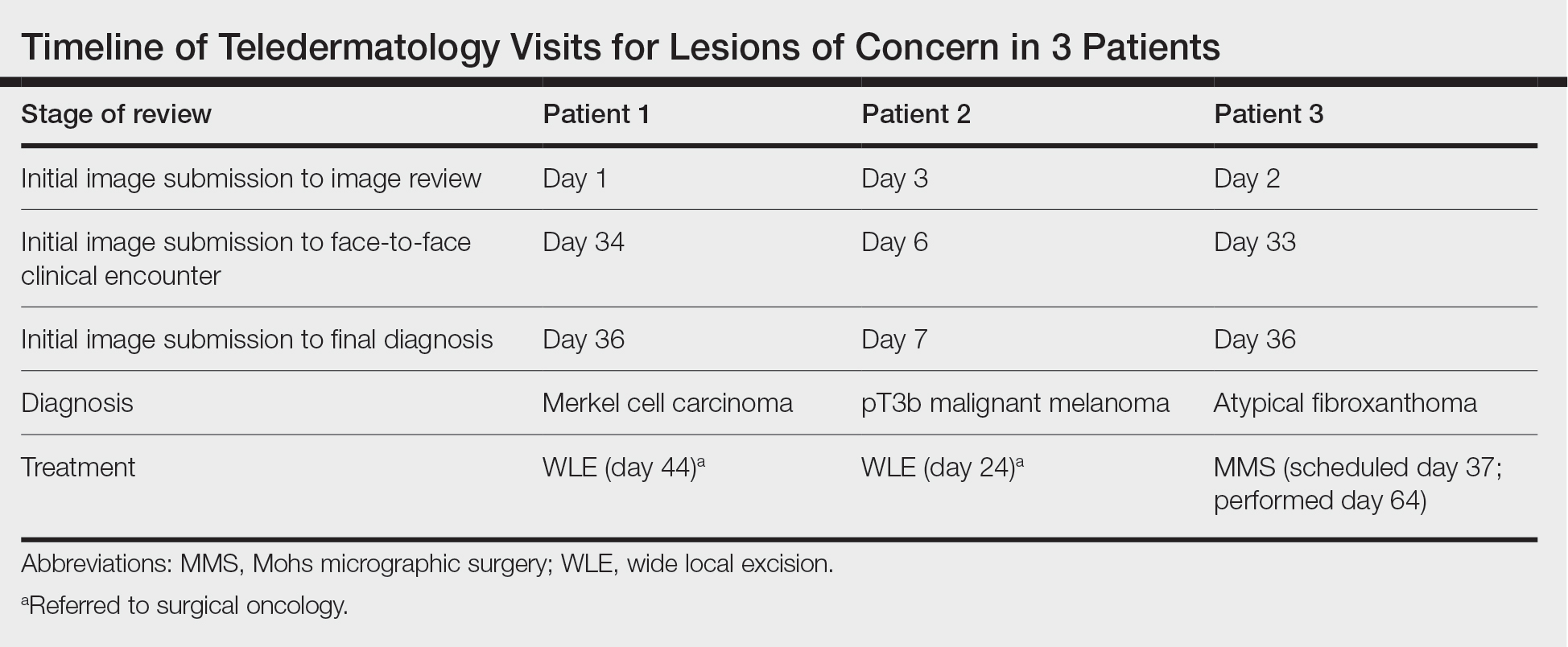

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Care for Patients With Skin Cancer

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

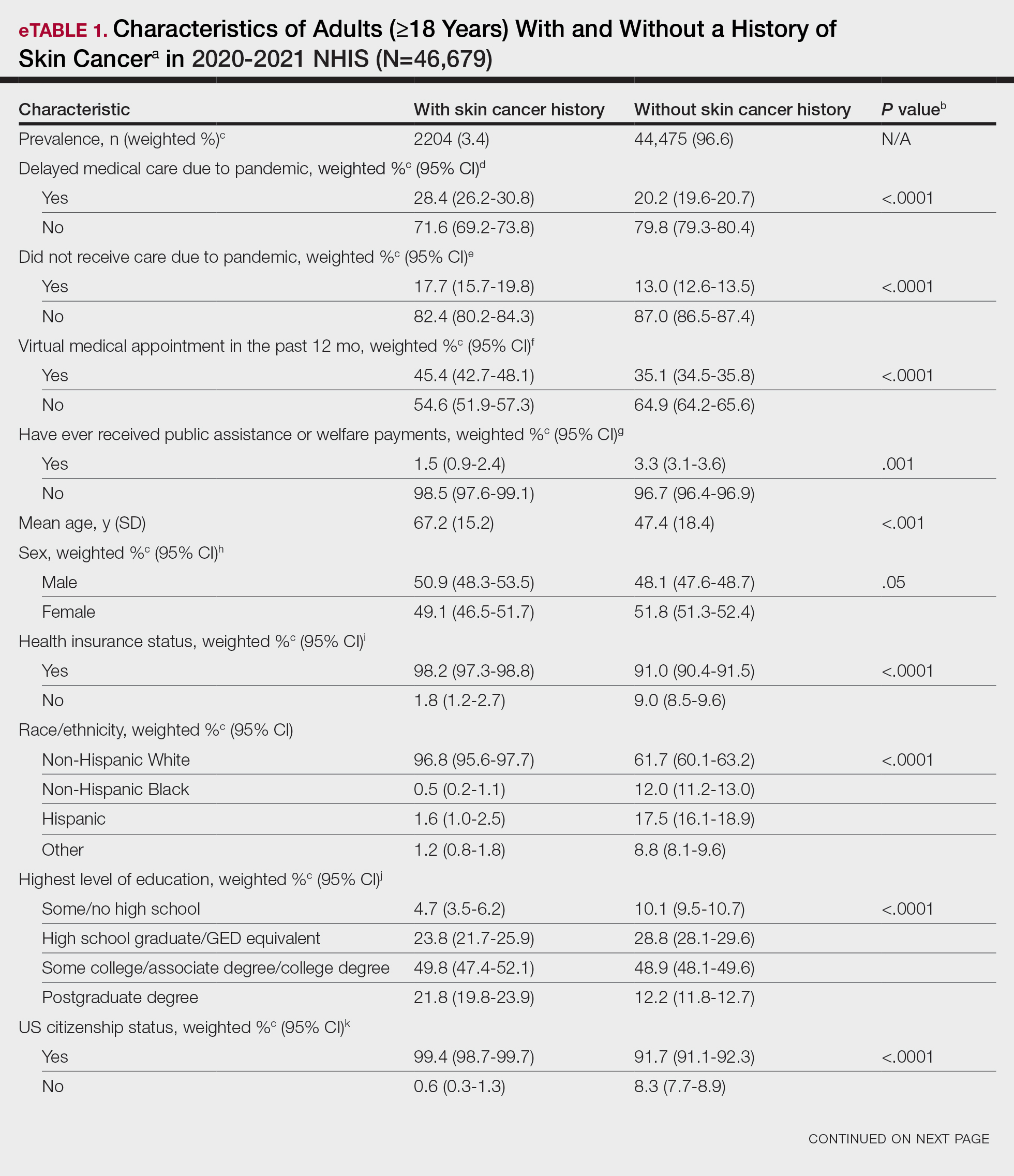

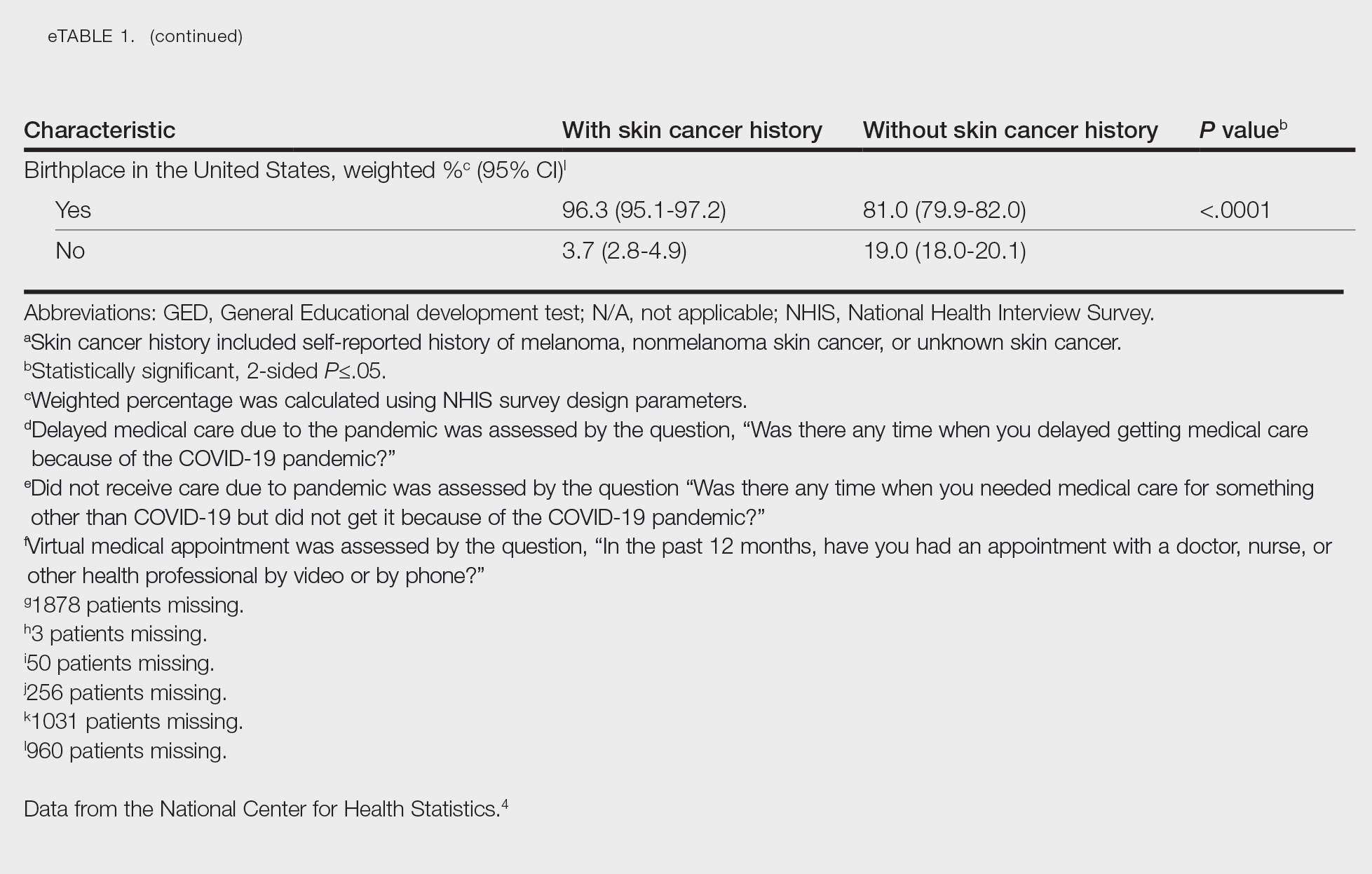

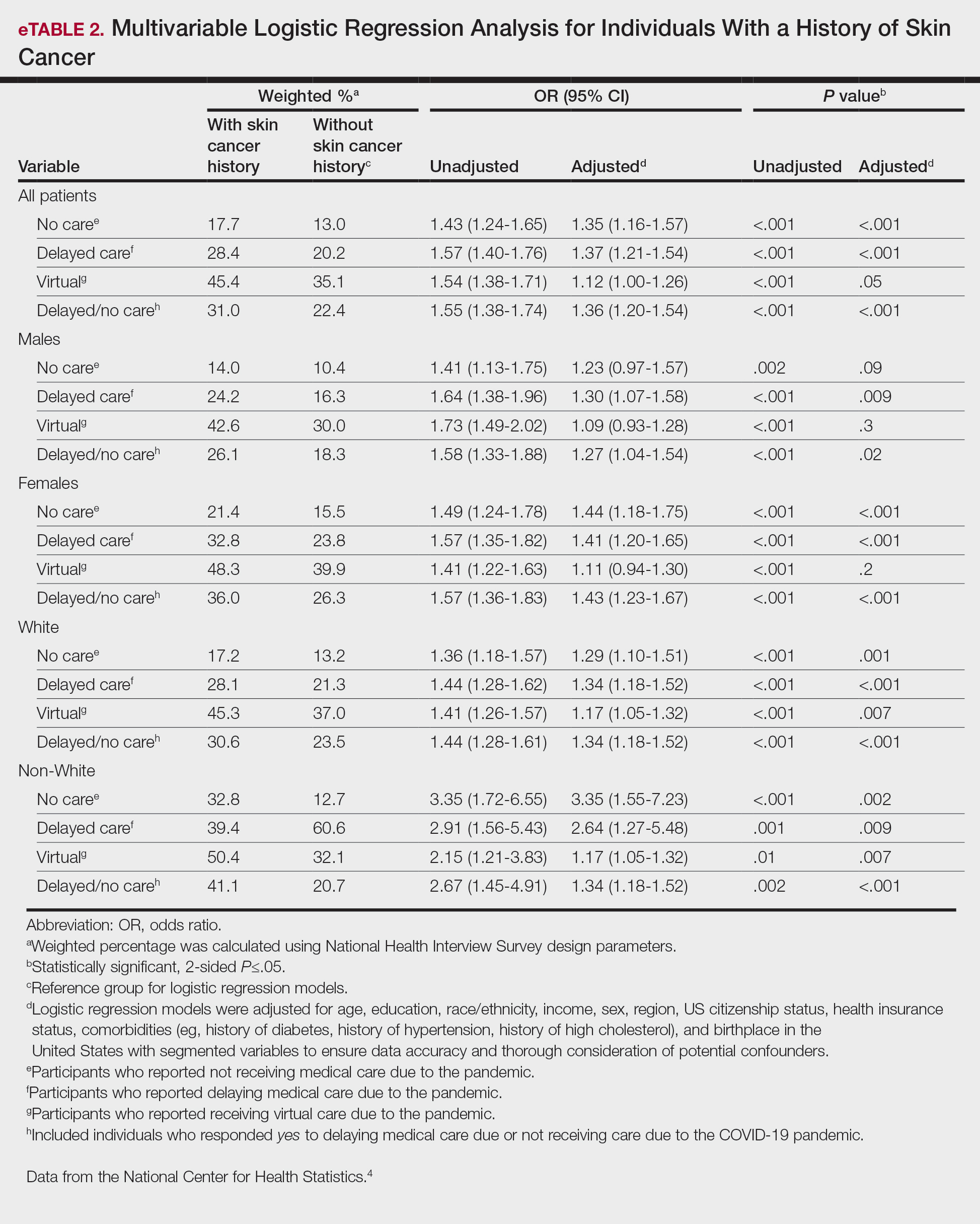

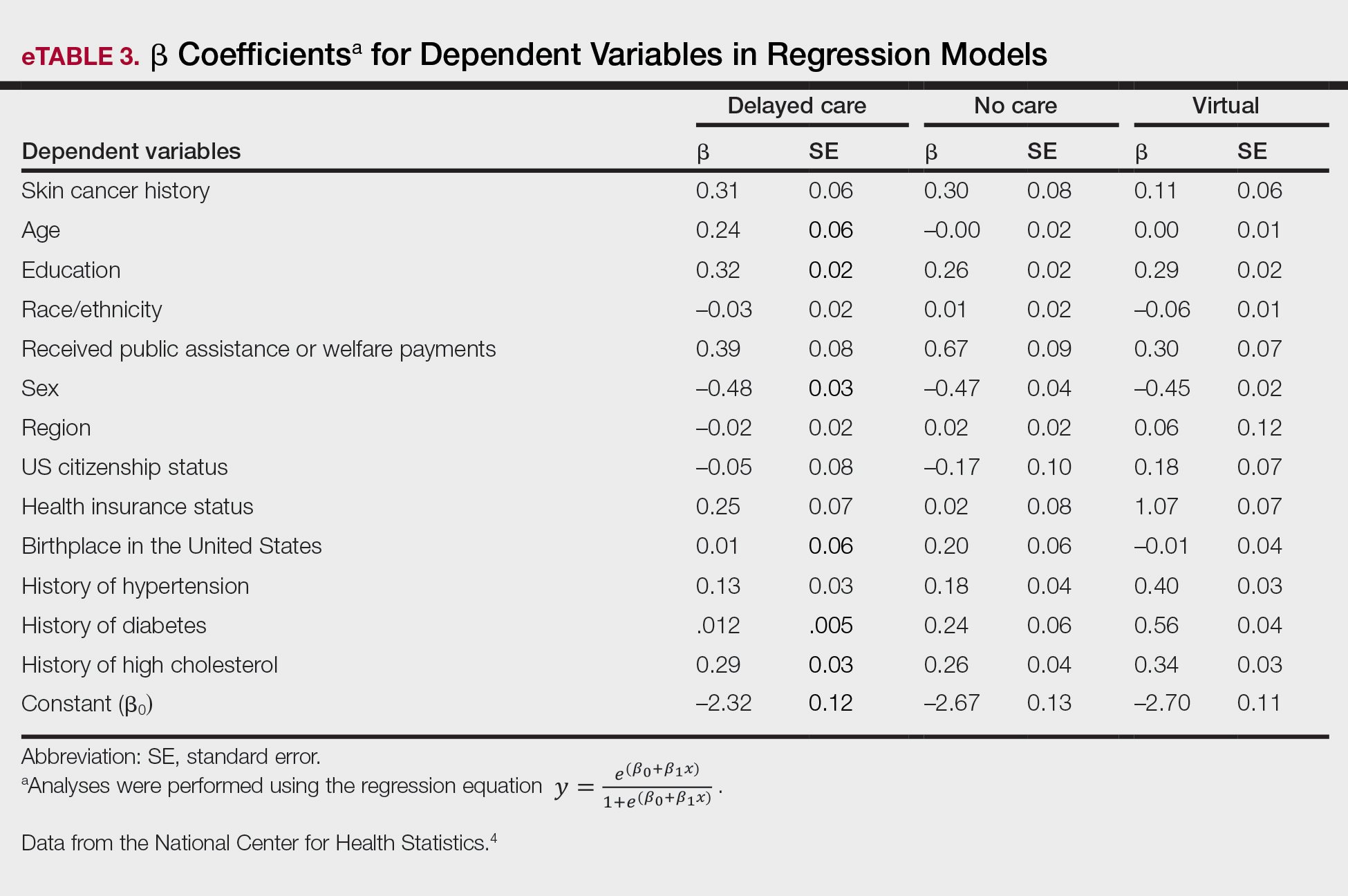

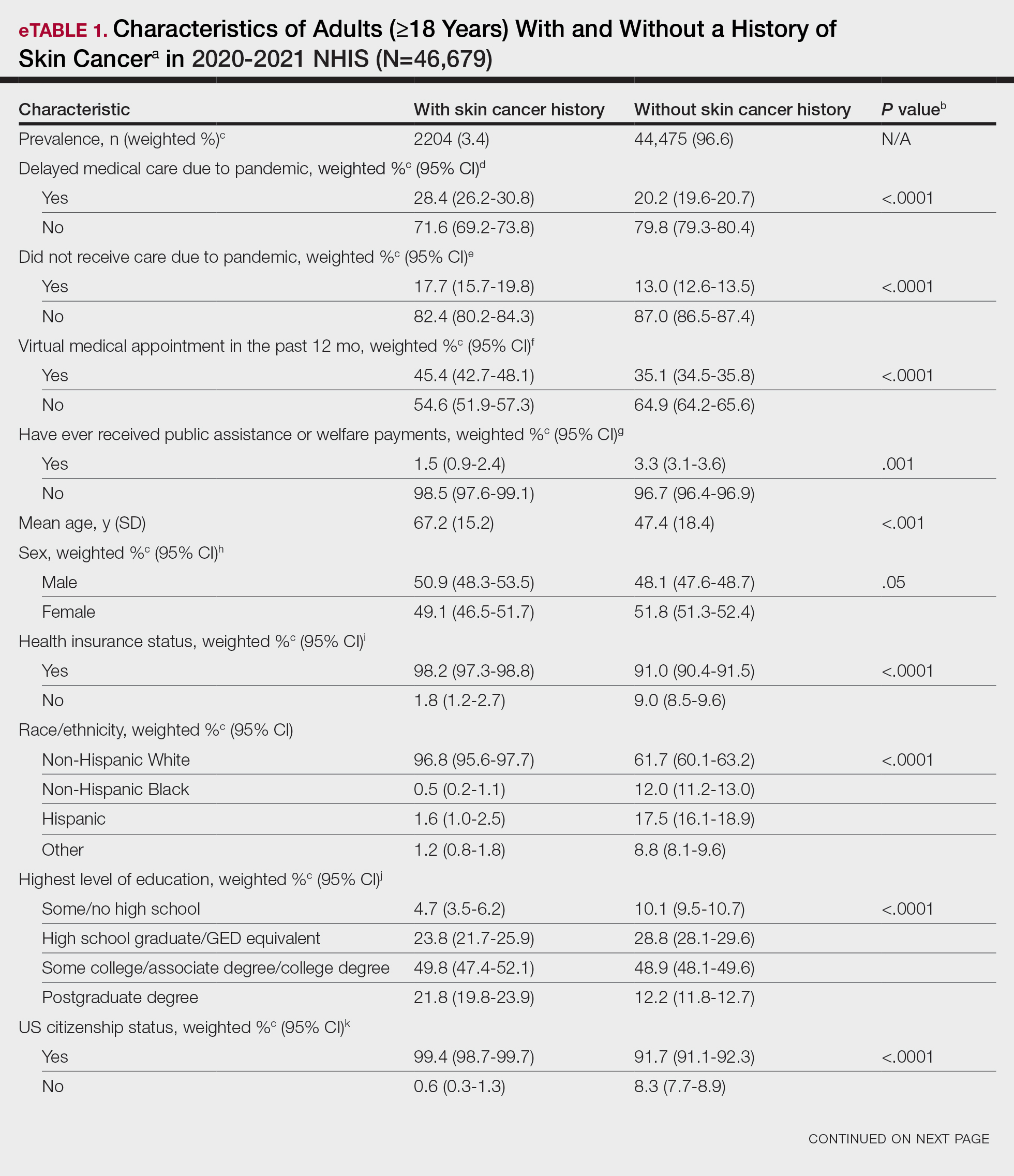

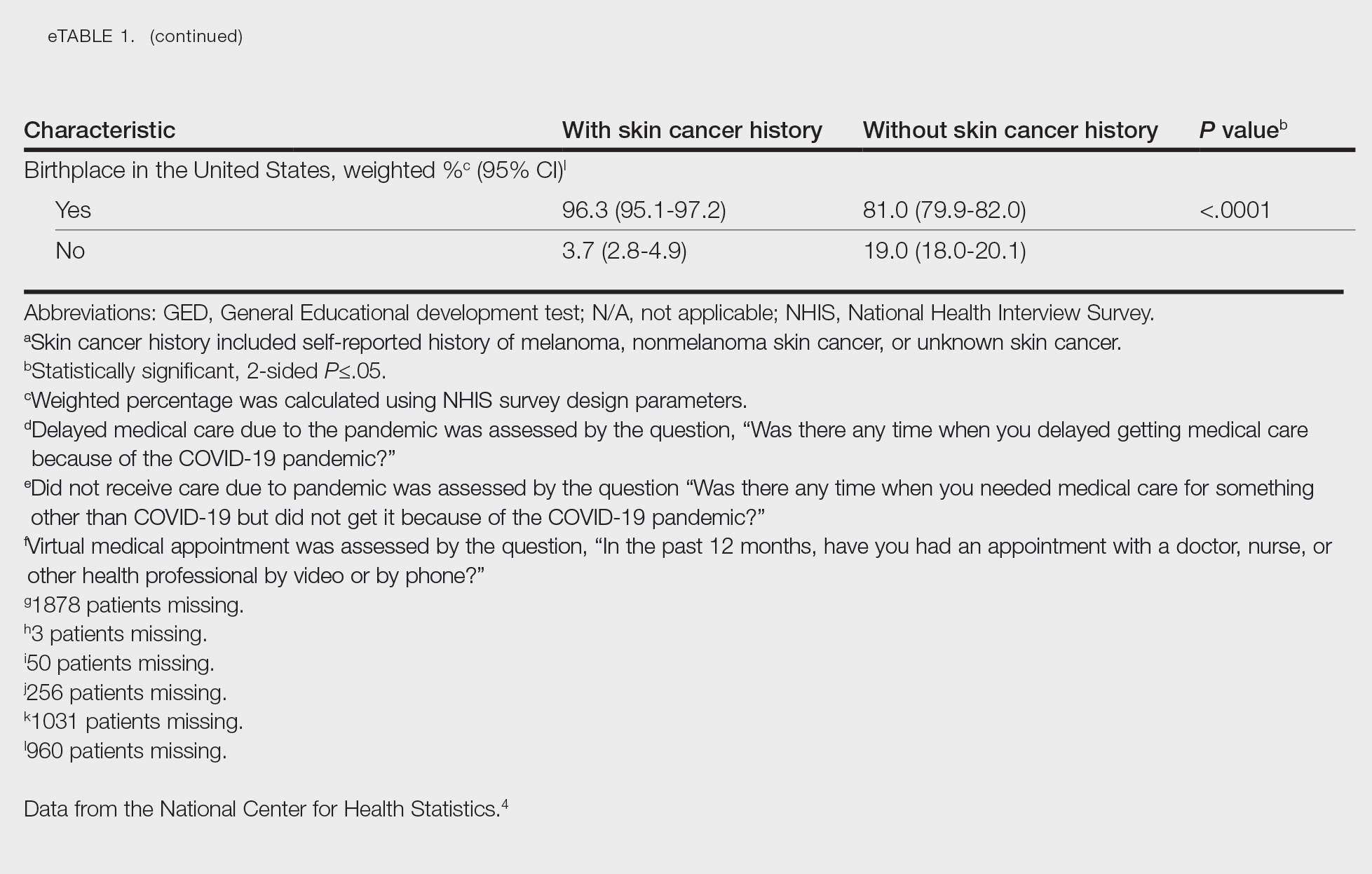

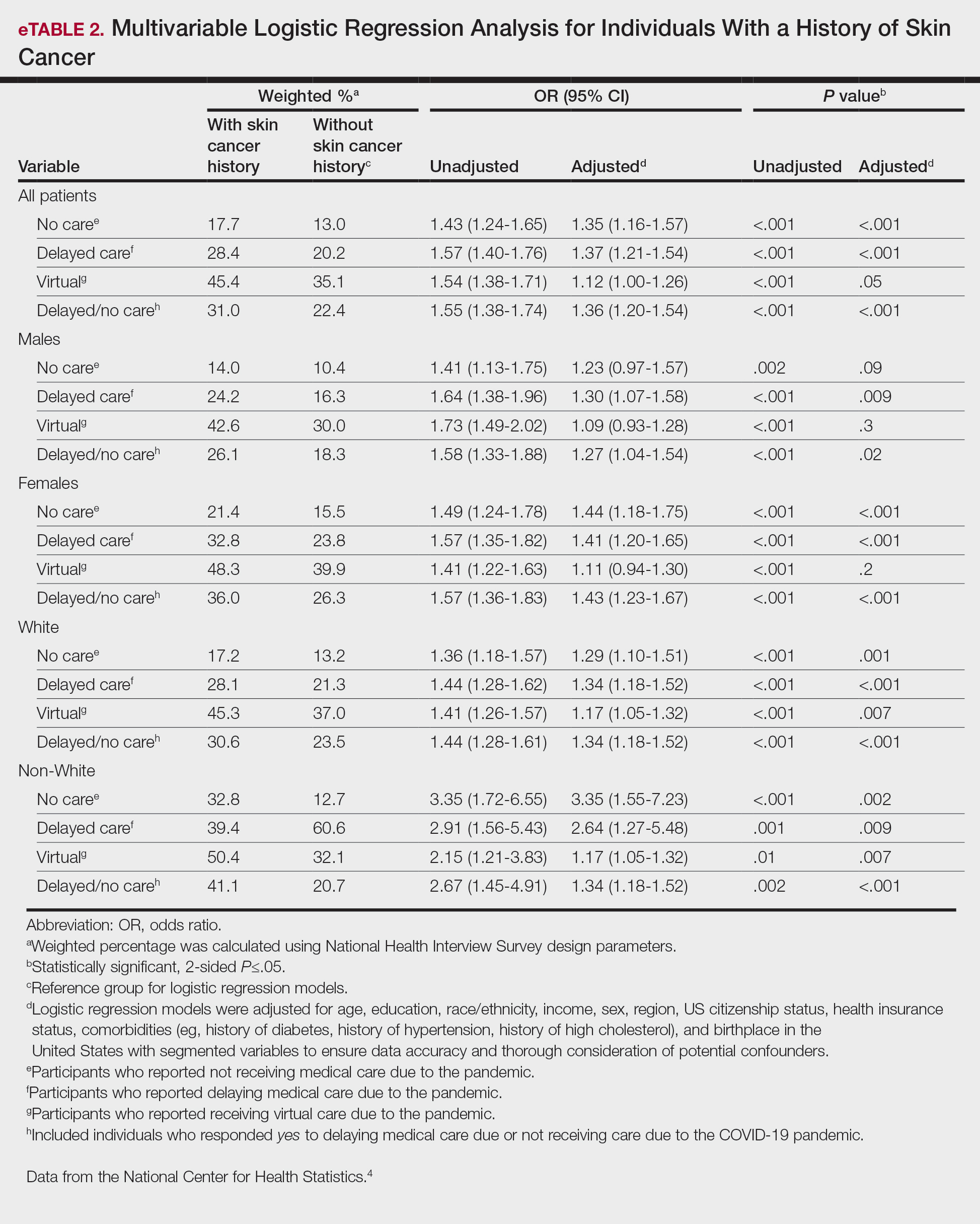

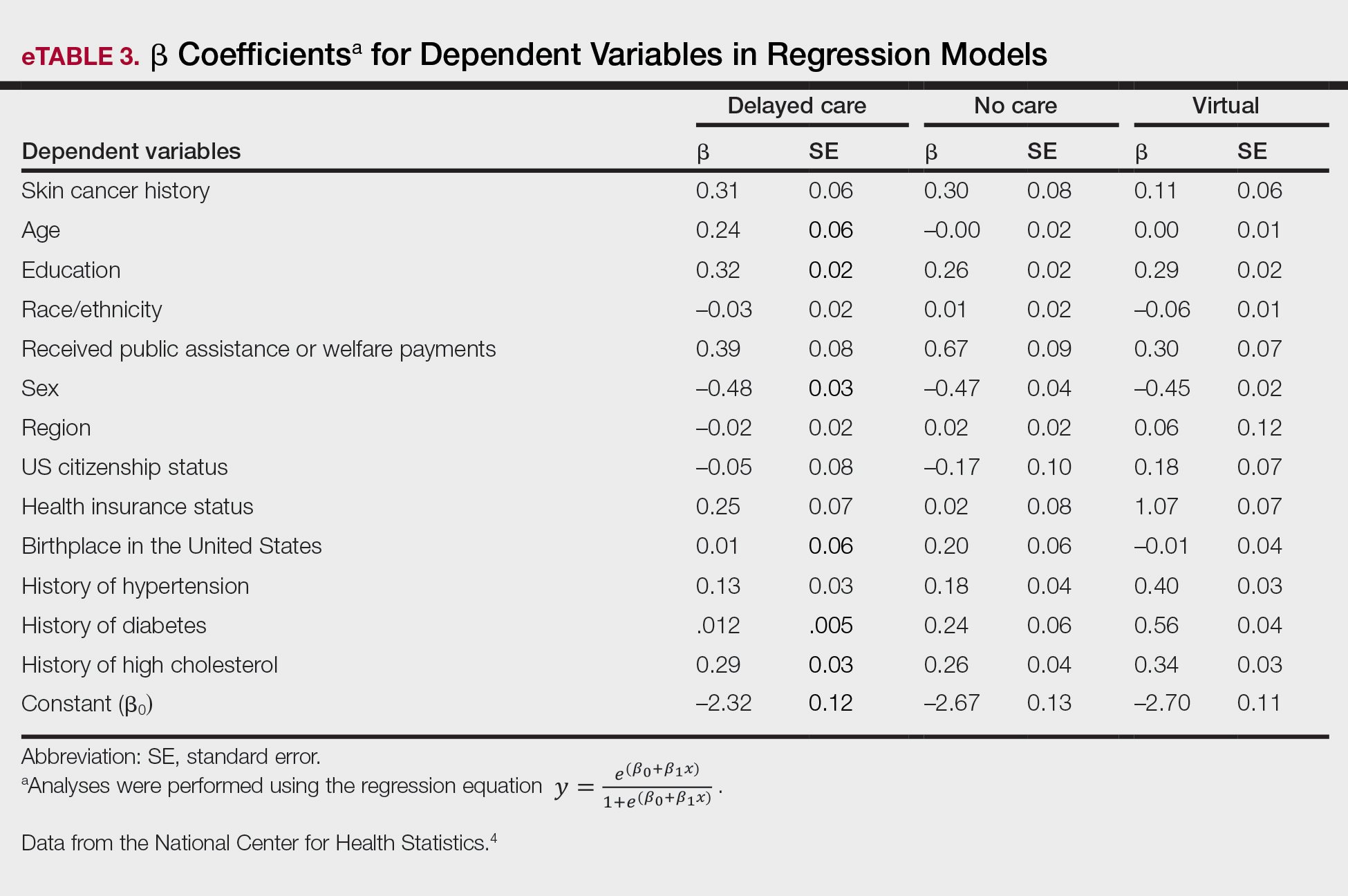

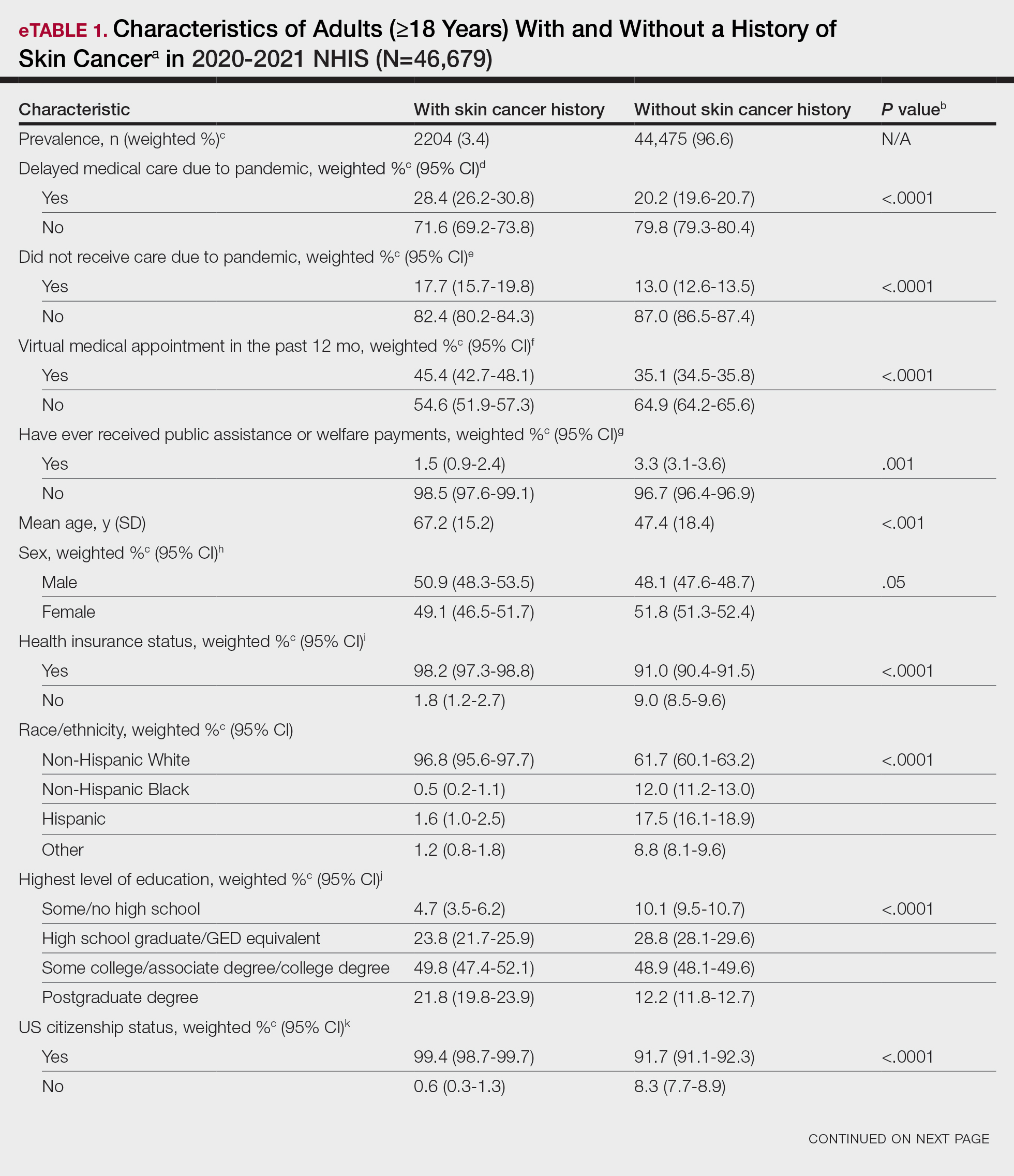

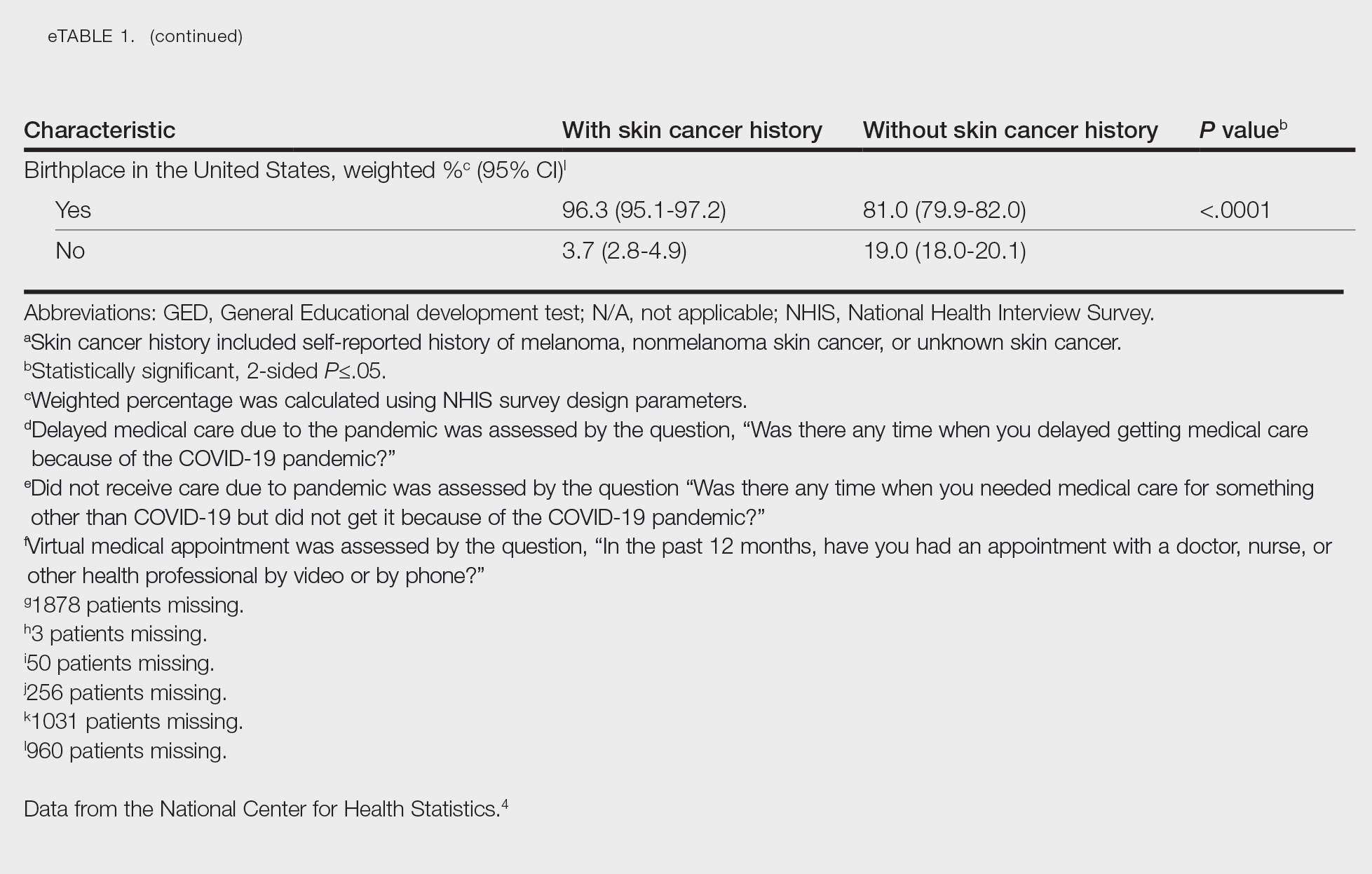

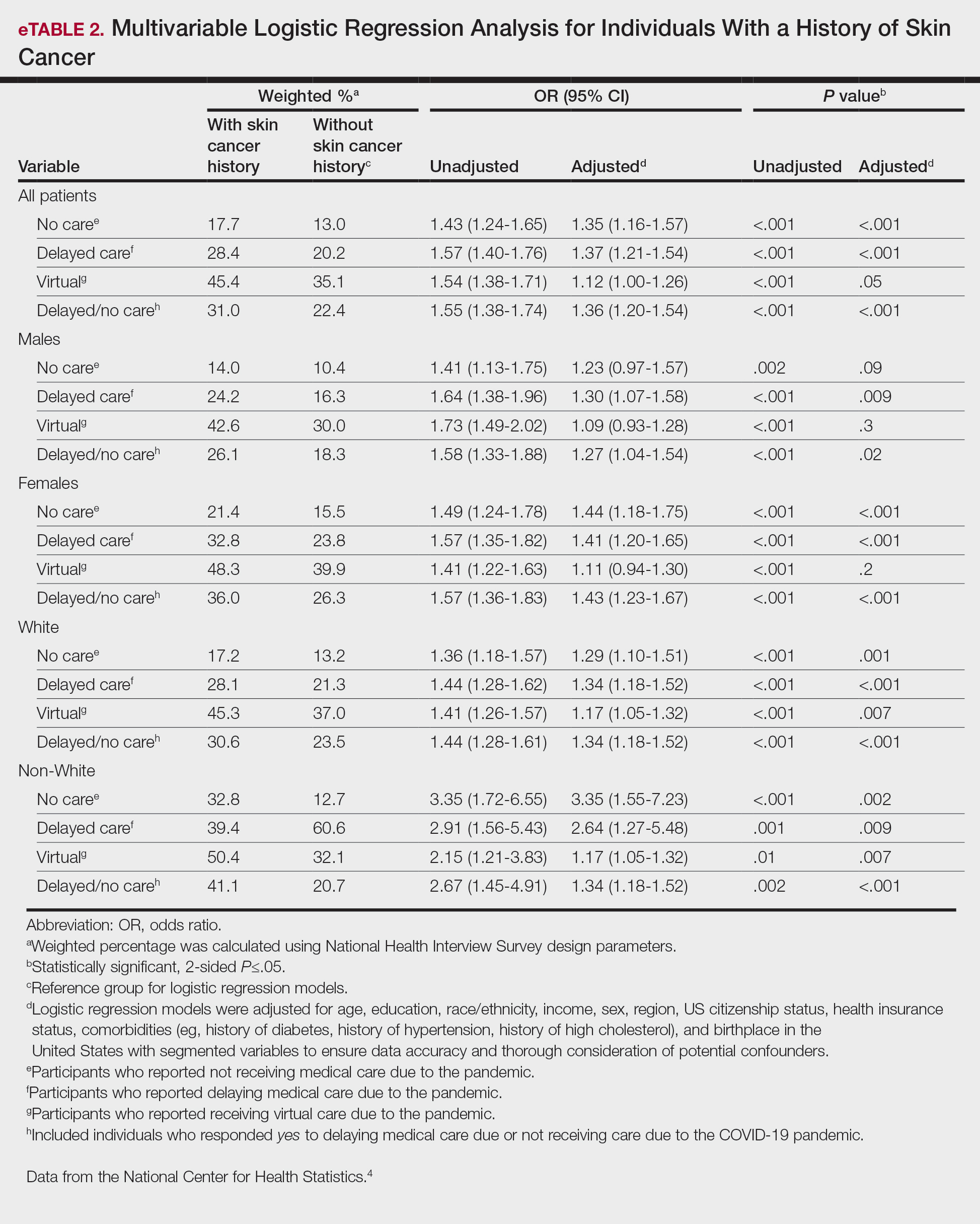

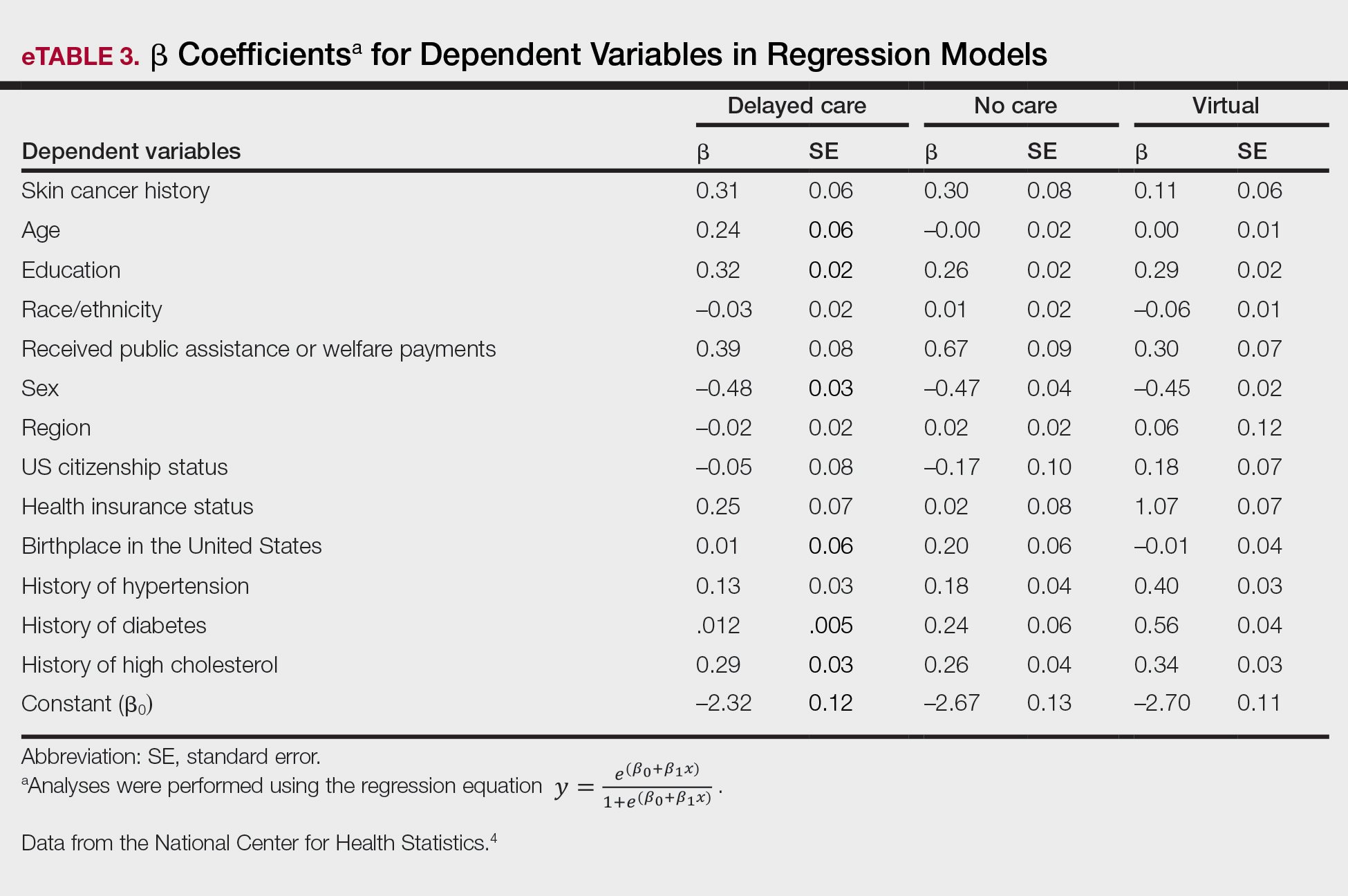

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

PRACTICE POINTS

- The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the landscape of medicine, as many individuals are now utilizing telemedicine to receive care.

- Many individuals will continue to receive telemedicine moving forward, making it crucial to understand access to care.

Comment on “Skin Cancer Screening: The Paradox of Melanoma and Improved All-Cause Mortality”

To the Editor:

I was unsurprised and gratified by the information presented in the Viewpoint on skin cancer screening by Ngo1 (Cutis. 2024;113:94-96). In my 30 years as a community dermatologist, I have observed that patients who opt to have periodic full-body skin examinations usually are more health literate, more likely to have a primary care physician (PCP) who has encouraged them to do so (ie, a conscientious practitioner directing their preventive care), more likely to have a strong will to live, and less likely to have multiple stressors that preclude self-care (eg, may be less likely to have a spouse for whom they are a caregiver) compared to those who do not get screened.

Findings on a full-body skin examination may impact patients in many ways, not only by the detection of skin cancers. I have discovered the following:

- evidence of diabetes/insulin resistance in the form of acanthosis nigricans, tinea corporis, erythrasma;

- evidence of rosacea associated with excessive alcohol intake;

- evidence of smoking-related issues such as psoriasis or hidradenitis suppurativa;

- cutaneous evidence of other systemic diseases (eg, autoimmune disease, cancer);

- elucidation of other chronic health problems (eg, psoriasis of the skin as a clue for undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis); and

- detection of parasites on the skin (eg, ticks) or signs of infection that may have notable ramifications (eg, interdigital maceration of a diabetic patient with tinea pedis).

I even saw a patient who had been sent for magnetic resonance imaging for back pain by her internist without any physical examination when she actually had an erosion over the sacrum from a rug burn!

When conducting full-body skin examinations, dermatologists should not underestimate these principles:

- The “magic” of using a relatively noninvasive and sensitive screening tool—comfort and stress reduction for the patient from a thorough visual, tactile, olfactory, and auditory examination.

- Human interaction—especially when the patient is seen annually or even more frequently over a period of years or decades, and especially when an excellent patient-physician rapport has been established.

- The impact of improving a patient’s appearance on their overall sense of well-being (eg, by controlling rosacea).

- The opportunity to introduce concepts (ie, educate patients) such as alcohol avoidance, smoking cessation, weight reduction, hygiene, diet, and exercise in a more tangential way than a PCP, as well as to consider with patients the idea that lifestyle modification may be an adjunct, if not a replacement, for prescription treatments.

- The stress reduction that ensues when a variety of self-identified health issues are addressed, for which the only treatment may be reassurance.

I would add to Dr. Ngo’s argument that stratifying patients into skin cancer risk categories may be a useful measure if the only goal of periodic dermatologic evaluation is skin cancer detection. One size rarely fits all when it comes to health recommendations.

In sum, I believe that periodic full-body skin examination is absolutely beneficial to patient care, and I am not at all surprised that all-cause mortality was lower in patients who have those examinations. Furthermore, when I offer my healthy, low-risk patients the option to return in 2 years rather than 1, the vast majority insist on 1 year. My mother used to say, “It’s better to be looked over than to be overlooked,” and I tell my patients that, too—but it seems they already know that instinctively.

- Ngo BT. Skin cancer screening: the paradox of melanoma and improved all-cause mortality. Cutis. 2024;113:94-96. doi:10.12788/cutis.0948

To the Editor:

I was unsurprised and gratified by the information presented in the Viewpoint on skin cancer screening by Ngo1 (Cutis. 2024;113:94-96). In my 30 years as a community dermatologist, I have observed that patients who opt to have periodic full-body skin examinations usually are more health literate, more likely to have a primary care physician (PCP) who has encouraged them to do so (ie, a conscientious practitioner directing their preventive care), more likely to have a strong will to live, and less likely to have multiple stressors that preclude self-care (eg, may be less likely to have a spouse for whom they are a caregiver) compared to those who do not get screened.

Findings on a full-body skin examination may impact patients in many ways, not only by the detection of skin cancers. I have discovered the following:

- evidence of diabetes/insulin resistance in the form of acanthosis nigricans, tinea corporis, erythrasma;

- evidence of rosacea associated with excessive alcohol intake;

- evidence of smoking-related issues such as psoriasis or hidradenitis suppurativa;

- cutaneous evidence of other systemic diseases (eg, autoimmune disease, cancer);

- elucidation of other chronic health problems (eg, psoriasis of the skin as a clue for undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis); and

- detection of parasites on the skin (eg, ticks) or signs of infection that may have notable ramifications (eg, interdigital maceration of a diabetic patient with tinea pedis).

I even saw a patient who had been sent for magnetic resonance imaging for back pain by her internist without any physical examination when she actually had an erosion over the sacrum from a rug burn!

When conducting full-body skin examinations, dermatologists should not underestimate these principles:

- The “magic” of using a relatively noninvasive and sensitive screening tool—comfort and stress reduction for the patient from a thorough visual, tactile, olfactory, and auditory examination.

- Human interaction—especially when the patient is seen annually or even more frequently over a period of years or decades, and especially when an excellent patient-physician rapport has been established.

- The impact of improving a patient’s appearance on their overall sense of well-being (eg, by controlling rosacea).

- The opportunity to introduce concepts (ie, educate patients) such as alcohol avoidance, smoking cessation, weight reduction, hygiene, diet, and exercise in a more tangential way than a PCP, as well as to consider with patients the idea that lifestyle modification may be an adjunct, if not a replacement, for prescription treatments.

- The stress reduction that ensues when a variety of self-identified health issues are addressed, for which the only treatment may be reassurance.

I would add to Dr. Ngo’s argument that stratifying patients into skin cancer risk categories may be a useful measure if the only goal of periodic dermatologic evaluation is skin cancer detection. One size rarely fits all when it comes to health recommendations.

In sum, I believe that periodic full-body skin examination is absolutely beneficial to patient care, and I am not at all surprised that all-cause mortality was lower in patients who have those examinations. Furthermore, when I offer my healthy, low-risk patients the option to return in 2 years rather than 1, the vast majority insist on 1 year. My mother used to say, “It’s better to be looked over than to be overlooked,” and I tell my patients that, too—but it seems they already know that instinctively.

To the Editor:

I was unsurprised and gratified by the information presented in the Viewpoint on skin cancer screening by Ngo1 (Cutis. 2024;113:94-96). In my 30 years as a community dermatologist, I have observed that patients who opt to have periodic full-body skin examinations usually are more health literate, more likely to have a primary care physician (PCP) who has encouraged them to do so (ie, a conscientious practitioner directing their preventive care), more likely to have a strong will to live, and less likely to have multiple stressors that preclude self-care (eg, may be less likely to have a spouse for whom they are a caregiver) compared to those who do not get screened.

Findings on a full-body skin examination may impact patients in many ways, not only by the detection of skin cancers. I have discovered the following:

- evidence of diabetes/insulin resistance in the form of acanthosis nigricans, tinea corporis, erythrasma;

- evidence of rosacea associated with excessive alcohol intake;

- evidence of smoking-related issues such as psoriasis or hidradenitis suppurativa;

- cutaneous evidence of other systemic diseases (eg, autoimmune disease, cancer);

- elucidation of other chronic health problems (eg, psoriasis of the skin as a clue for undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis); and

- detection of parasites on the skin (eg, ticks) or signs of infection that may have notable ramifications (eg, interdigital maceration of a diabetic patient with tinea pedis).

I even saw a patient who had been sent for magnetic resonance imaging for back pain by her internist without any physical examination when she actually had an erosion over the sacrum from a rug burn!

When conducting full-body skin examinations, dermatologists should not underestimate these principles:

- The “magic” of using a relatively noninvasive and sensitive screening tool—comfort and stress reduction for the patient from a thorough visual, tactile, olfactory, and auditory examination.

- Human interaction—especially when the patient is seen annually or even more frequently over a period of years or decades, and especially when an excellent patient-physician rapport has been established.

- The impact of improving a patient’s appearance on their overall sense of well-being (eg, by controlling rosacea).

- The opportunity to introduce concepts (ie, educate patients) such as alcohol avoidance, smoking cessation, weight reduction, hygiene, diet, and exercise in a more tangential way than a PCP, as well as to consider with patients the idea that lifestyle modification may be an adjunct, if not a replacement, for prescription treatments.

- The stress reduction that ensues when a variety of self-identified health issues are addressed, for which the only treatment may be reassurance.

I would add to Dr. Ngo’s argument that stratifying patients into skin cancer risk categories may be a useful measure if the only goal of periodic dermatologic evaluation is skin cancer detection. One size rarely fits all when it comes to health recommendations.

In sum, I believe that periodic full-body skin examination is absolutely beneficial to patient care, and I am not at all surprised that all-cause mortality was lower in patients who have those examinations. Furthermore, when I offer my healthy, low-risk patients the option to return in 2 years rather than 1, the vast majority insist on 1 year. My mother used to say, “It’s better to be looked over than to be overlooked,” and I tell my patients that, too—but it seems they already know that instinctively.

- Ngo BT. Skin cancer screening: the paradox of melanoma and improved all-cause mortality. Cutis. 2024;113:94-96. doi:10.12788/cutis.0948

- Ngo BT. Skin cancer screening: the paradox of melanoma and improved all-cause mortality. Cutis. 2024;113:94-96. doi:10.12788/cutis.0948

Understanding the Evaluation and Management Add-on Complexity Code

On January 1, 2024, a new add-on complexity code, G2211, was implemented to the documentation of evaluation and management (E/M) visits.1 Created by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), G2211 is defined as “visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single, serious, or complex condition.”2 It is an add-on code, meaning that it must be listed with either a new or established outpatient E/M visit.

G2211 originally was introduced in the 2021 Proposed Rule but was delayed via a congressional mandate for 3 years.1 It originally was estimated that this code would be billed with 90% of all office visit claims, accounting for an approximately $3.3 billion increase in physician fee schedule spending; however, this estimate was revised with its reintroduction in the 2024 Final Rule, and it currently is estimated that it will be billed with 38% of all office visit claims.3,4

This add-on code was created to capture the inherent complexity of an E/M visit that is derived from the longitudinal nature of the physician-patient relationship and to better account for the additional resources of these outpatient E/M visits.5 Although these criteria often are met in the setting of an E/M visit within a primary care specialty (eg, family practice, internal medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, pediatrics), this code is not restricted to medical professionals based on specialties. The CMS noted that “the most important information used to determine whether the add-on code could be billed is the relationship between the practitioner and the patient,” specifically if they are fulfilling one of the following roles: “the continuing focal point for all needed health care services” or “ongoing care related to a patient's single, serious and complex condition.”6

Of note, further definitions regarding what constitutes a single, serious or complex condition have not yet been provided by CMS. The code should not be utilized when the relationship with the patient is of a discrete, routine, or time-limited nature. The resulting care should be personalized and should result in a comprehensive, longitudinal, and continuous relationship with the patient and should involve delivery of team-based care that is accessible, coordinated with other practitioners and providers, and integrated with the broader health care landscape.6

Herein, 5 examples are provided of scenarios when G2211 might be utilized as well as when it would not be appropriate to bill for this code.

Example 1

A 48-year-old man (an established patient) with a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis presents to a dermatologist for follow-up. The dermatologist has been managing both conditions for 3 years with methotrexate. The patient’s disease is well controlled at the current visit, and he presents for follow-up of disease activity and laboratory monitoring every 3 months. The dermatologist continues the patient on methotrexate after reviewing the risks, benefits, and adverse effects and orders a complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel.

Would use of G2211 be appropriate for this visit?—Yes, in this case it would be appropriate to bill for G2211. In this example, the physician is providing longitudinal ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single, serious or complex condition—specifically psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis—via managing methotrexate therapy.

Example 2

Let’s alter the previous example slightly: A 48-year-old man (an established patient) with a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis presents to a dermatologist for follow-up. He is being followed by both a dermatologist and a rheumatologist. The patient is on methotrexate, which was prescribed by the rheumatologist, who also conducts the appropriate laboratory monitoring. The patient’s skin disease currently is well controlled, and the dermatologist discusses this with the patient and advises that he continue to follow up with rheumatology.

Would use of G2211 be appropriate for this visit?—No, in this case it would not be appropriate to utilize G2211. In this example, the dermatologist is providing longitudinal ongoing medical care; however, unlike in the first example, much of the ongoing medical care—in particular the management of the patient’s methotrexate therapy—is being performed by the rheumatologist. Therefore, although these conditions are serious or complex, the dermatologist is not the primary manager of treatment, and it would not be appropriate to bill for G2211.

Example 3

A 35-year-old woman (an established patient) presents to a dermatologist for follow-up of hidradenitis suppurativa. She currently is receiving infliximab infusions that are managed by the dermatologist. At the current presentation, physical examination reveals several persistent active lesions. After discussing possible treatment options, the dermatologist elects to continue infliximab therapy and schedule a deroofing procedure of the persistent areas.

Would use of G2211 be appropriate for this visit?—Yes, in this example it would be appropriate to utilize G2211. The patient has hidradenitis suppurativa, which would be considered a single, serious or complex condition. Additionally, the dermatologist is the primary manager of this condition by prescribing infliximab as well as counseling the patient on the appropriateness of procedural interventions and scheduling for these procedures; the dermatologist also is providing ongoing longitudinal care.

Example 4

Let’s alter the previous example slightly: A 35-year-old woman (an established patient) presents to a dermatologist for follow-up of hidradenitis suppurativa. She currently is receiving infliximab infusions, which are managed by the dermatologist. At the current presentation, physical examination reveals several persistent active lesions. After discussing possible treatment options, the dermatologist elects to perform intralesional triamcinolone injections to active areas during the current visit.

Would use of G2211 be appropriate for this visit?—No, in this case it would not be appropriate to bill for G2211. Similar to Example 3, the dermatologist is treating a single, serious and complex condition and is primarily managing the disease and providing longitudinal care; however, in this case the dermatologist also is performing a minor procedure during the visit: injection of intralesional triamcinolone.

Importantly, G2211 cannot be utilized when modifier -25 is being appended to an outpatient E/M visit. Modifier -25 is defined as a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service.”7 Modifier -25 is utilized when a minor procedure is performed by a qualified health care professional on the same day (generally during the same visit) as an E/M visit. Therefore, G2211 cannot be utilized when a minor procedure (eg, a tangential biopsy, punch biopsy, destruction or intralesional injection into skin) is performed during a visit.

Example 5

A 6-year-old girl presents to a dermatologist for a new rash on the trunk that started 5 days after an upper respiratory infection. The dermatologist evaluates the patient and identifies a blanchable macular eruption on the trunk; the patient is diagnosed with a viral exanthem. Because the patient reported associated pruritus, topical triamcinolone is prescribed.

Would use of G2211 be appropriate for this visit?—No, in this case it would not be appropriate to bill for G2211. A viral exanthem would not be considered an ongoing single, serious or complex condition and would be more consistent with a discrete condition; therefore, even though the dermatologist is primarily managing the disease process, it still would not fulfill the criteria necessary to bill for G2211.

Final Thoughts

G2211 is an add-on code created by the CMS that can be utilized in conjunction with an outpatient E/M visit when certain requirements are fulfilled. Specifically, this code can be utilized when the dermatologist is the primary provider of care for a patient’s ongoing single, serious or complex condition or serves as the continuing focal point for all of the patient’s health care needs. Understanding the nuances associated with this code are critical for correct billing.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar Year (CY) 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule final rule. Published November 2, 2023. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2024-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fact Sheet—Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) payment for office/outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) visits. Published January 11, 2021. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/physician-fee-schedule-pfs-payment-officeoutpatient-evaluation-and-management-em-visits-fact-sheet.pdf

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Broken Medicare system results in CMS proposing reduced physician payments in 2024. Published July 13, 2023. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.asahq.org/advocacy-and-asapac/fda-and-washington-alerts/washington-alerts/2023/07/broken-medicare-system-results-in-cms-proposing-reduced-physician-payments-in-2024

- American Medical Association. CY 2024 Medicare physician payment schedule and quality payment program (QPP) final rule summary. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/ama-summary-2024-mfs-proposed-rule.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. How to use the office & outpatient evaluation and management visit complexity add-on code G2211. MM13473. MLN Matters. Updated January 18, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mm13473-how-use-office-and-outpatient-evaluation-and-management-visit-complexity-add-code-g2211.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS manual system. Published January 18, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/r12461cp.pdf