User login

Sunscreen Safety: 2024 Updates

Sunscreen is a cornerstone of skin cancer prevention. The first commercial sunscreen was developed nearly 100 years ago,1 yet questions and concerns about the safety of these essential topical photoprotective agents continue to occupy our minds. This article serves as an update on some of the big sunscreen questions, as informed by the available evidence.

Are sunscreens safe?

The story of sunscreen regulation in the United States is long and dry. The major pain point is that sunscreens are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as over-the-counter drugs rather than cosmetics (as in Europe).2 Regulatory hurdles created a situation wherein no new active sunscreen ingredient has been approved by the FDA since 1999, except ecamsule for use in one product line. There is hope that changes enacted under the CARES Act will streamline and expedite the sunscreen approval process in the future.3

Amid the ongoing regulatory slog, the FDA became interested in learning more about sunscreen safety. Specifically, they sought to determine the GRASE (generally regarded as safe and effective) status of the active ingredients in sunscreens. In 2019, only the inorganic (physical/mineral) UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide were considered GRASE.4 Trolamine salicylate and para-aminobenzoic acid were not GRASE, but they currently are not used in sunscreens in the United States. For all the remaining organic (chemical) filters, additional safety data were required to establish GRASE status.4 In 2024, the situation remains largely unchanged. Industry is working with the FDA on testing requirements.5

Why the focus on safety? After all, sunscreens have been used widely for decades without any major safety signals; their only well-established adverse effects are contact dermatitis and staining of clothing.6 Although preclinical studies raised concerns that chemical sunscreens could be associated with endocrine, reproductive, and neurologic toxicities, to date there are no high-quality human studies demonstrating negative effects.7,8

However, exposure patterns have evolved. Sunscreen is recommended to be applied (and reapplied) daily. Also, chemical UV filters are used in many nonsunscreen products such as cosmetics, shampoos, fragrances, and plastics. In the United States, exposure to chemical sunscreens is ubiquitous; according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004, oxybenzone was detected in 97% of more than 2500 urine samples, implying systemic absorption but not harm.9

The FDA confirmed the implication of systemic absorption via 2 maximal usage trials published in 2019 and 2020.10,11 In both studies, several chemical sunscreens were applied at the recommended density of 2 mg/cm2 to 75% of the body surface area multiple times over 4 days. For all tested organic UV filters, blood levels exceeded the predetermined FDA cutoff (0.5 ng/mL), even after one application.10,11 What’s the takeaway? Simply that the FDA now requires additional safety data for chemical sunscreen filters5; the findings in no way imply any associated harm. Two potential mitigating factors are that no one applies sunscreen at 2 mg/cm2, and the FDA’s blood level cutoff was a general estimate not specific to sunscreens.4,12

Nevertheless, a good long-term safety record for sunscreens does not negate the need for enhanced safety data when there is clear evidence of systemic absorption. In the meantime, concerned patients should be counseled that the physical/mineral sunscreens containing zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are considered GRASE by the FDA; even in nanoparticle form, they generally have not been found to penetrate beneath the stratum corneum.7,13

Does sunscreen cause frontal fibrosing alopecia?

Dermatologists are confronting the conundrum of rising cases of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). Several theories on the pathogenesis of this idiopathic scarring alopecia have been raised, one of which involves increased use of sunscreen. Proposed explanations for sunscreen’s role in FFA include a lichenoid reaction inducing hair follicle autoimmunity through an unclear mechanism; a T cell–mediated allergic reaction, which is unlikely according to contact dermatitis experts14; reactive oxygen species production by titanium nanoparticles, yet titanium has been detected in hair follicles of both patients with FFA and controls15; and endocrine disruption following systemic absorption, which has not been supported by any high-quality human studies.7

An association between facial sunscreen use and FFA has been reported in case-control studies16; however, they have been criticized due to methodologic issues and biases, and they provide no evidence of causality.17,18 The jury remains out on the controversial association between sunscreen and FFA, with a need for more convincing data.

Does sunscreen impact coral reef health?

Coral reefs—crucial sources of aquatic biodiversity—are under attack from several different directions including climate change and pollution. As much as 14,000 tons of sunscreen enter coral reefs each year, and chemical sunscreen filters are detectable in waterways throughout the world—even in the Arctic.19,20 Thus, sunscreen has come under scrutiny as a potential environmental threat, particularly with coral bleaching.

Bleaching is a process in which corals exposed to an environmental stressor expel their symbiotic photosynthetic algae and turn white; if conditions fail to improve, the corals are vulnerable to death. In a highly cited 2016 study, coral larvae exposed to oxybenzone in artificial laboratory conditions displayed concentration-dependent mortality and decreased chlorophyll fluorescence, which suggested bleaching.19 These findings influenced legislation in Hawaii and other localities banning sunscreens containing oxybenzone. Problematically, the study has been criticized for acutely exposing the most susceptible coral life-forms to unrealistic oxybenzone concentrations; more broadly, there is no standardized approach to coral toxicity testing.21

The bigger picture (and elephant in the room) is that the primary cause of coral bleaching is undoubtedly climate change/ocean warming.7 More recent studies suggest that oxybenzone probably adds insult to injury for corals already debilitated by ocean warming.22,23

It has been posited that a narrow focus on sunscreens detracts attention from the climate issue.24 Individuals can take a number of actions to reduce their carbon footprint in an effort to preserve our environment, specifically coral reefs.25 Concerned patients should be counseled to use sunscreens containing the physical/mineral UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide, which are unlikely to contribute to coral bleaching as commercially formulated.7

Ongoing Questions

A lot of unknowns about sunscreen safety remain, and much hubbub has been made over studies that often are preliminary at best. At the time of this writing, absent a crystal ball, this author continues to wear chemical sunscreens; spends a lot more time worrying about their carbon footprint than what type of sunscreen to use at the beach; and believes the association of FFA with sunscreen is unlikely to be causal. Hopefully much-needed rigorous evidence will guide our future approach to sunscreen formulation and use.

- Ma Y, Yoo J. History of sunscreen: an updated view. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1044-1049.

- Pantelic MN, Wong N, Kwa M, et al. Ultraviolet filters in the United States and European Union: a review of safety and implications for the future of US sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:632-646.

- Mohammad TF, Lim HW. The important role of dermatologists in public education on sunscreens. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:509-511.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use: proposed rule. Fed Regist. 2019;84:6204-6275.

- Lim HW, Mohammad TF, Wang SQ. Food and Drug Administration’s proposed sunscreen final administrative order: how does it affect sunscreens in the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E83-E84.

- Ekstein SF, Hylwa S. Sunscreens: a review of UV filters and their allergic potential. Dermatitis. 2023;34:176-190.

- Adler BL, DeLeo VA. Sunscreen safety: a review of recent studies on humans and the environment. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2020;9:1-9.

- Suh S, Pham C, Smith J, et al. The banned sunscreen ingredients and their impact on human health: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1033-1042.

- Calafat AM, Wong LY, Ye X, et al. Concentrations of the sunscreen agent benzophenone-3 in residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:893-897.

- Matta MK, Florian J, Zusterzeel R, et al. Effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:256-267.

- Matta MK, Zusterzeel R, Pilli NR, et al. Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2082-2091.

- Petersen B, Wulf HC. Application of sunscreen—theory and reality. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:96-101.

- Mohammed YH, Holmes A, Haridass IN, et al. Support for the safe use of zinc oxide nanoparticle sunscreens: lack of skin penetration or cellular toxicity after repeated application in volunteers. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:308-315.

- Felmingham C, Yip L, Tam M, et al. Allergy to sunscreen and leave-on facial products is not a likely causative mechanism in frontal fibrosing alopecia: perspective from contact allergy experts. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:481-482.

- Thompson CT, Chen ZQ, Kolivras A, et al. Identification of titanium dioxide on the hair shaft of patients with and without frontal fibrosing alopecia: a pilot study of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:216-217.

- Maghfour J, Ceresnie M, Olson J, et al. The association between frontal fibrosing alopecia, sunscreen, and moisturizers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:395-396.

- Seegobin SD, Tziotzios C, Stefanato CM, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia:there is no statistically significant association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1407-1408.

- Ramos PM, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Regarding methodologic concerns in clinical studies on frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E207-E208.

- Downs CA, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2016;70:265-288.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health. The National Academies Press; 2022.

- Mitchelmore CL, Burns EE, Conway A, et al. A critical review of organic ultraviolet filter exposure, hazard, and risk to corals. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2021;40:967-988.

- Vuckovic D, Tinoco AI, Ling L, et al. Conversion of oxybenzone sunscreen to phototoxic glucoside conjugates by sea anemones and corals. Science. 2022;376:644-648.

- Wijgerde T, van Ballegooijen M, Nijland R, et al. Adding insult to injury: effects of chronic oxybenzone exposure and elevated temperature on two reef-building corals. Sci Total Environ. 2020;733:139030.

- Sirois J. Examine all available evidence before making decisions on sunscreen ingredient bans. Sci Total Environ. 2019;674:211-212.

- United Nations. Actions for a healthy planet. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/actnow/ten-actions

Sunscreen is a cornerstone of skin cancer prevention. The first commercial sunscreen was developed nearly 100 years ago,1 yet questions and concerns about the safety of these essential topical photoprotective agents continue to occupy our minds. This article serves as an update on some of the big sunscreen questions, as informed by the available evidence.

Are sunscreens safe?

The story of sunscreen regulation in the United States is long and dry. The major pain point is that sunscreens are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as over-the-counter drugs rather than cosmetics (as in Europe).2 Regulatory hurdles created a situation wherein no new active sunscreen ingredient has been approved by the FDA since 1999, except ecamsule for use in one product line. There is hope that changes enacted under the CARES Act will streamline and expedite the sunscreen approval process in the future.3

Amid the ongoing regulatory slog, the FDA became interested in learning more about sunscreen safety. Specifically, they sought to determine the GRASE (generally regarded as safe and effective) status of the active ingredients in sunscreens. In 2019, only the inorganic (physical/mineral) UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide were considered GRASE.4 Trolamine salicylate and para-aminobenzoic acid were not GRASE, but they currently are not used in sunscreens in the United States. For all the remaining organic (chemical) filters, additional safety data were required to establish GRASE status.4 In 2024, the situation remains largely unchanged. Industry is working with the FDA on testing requirements.5

Why the focus on safety? After all, sunscreens have been used widely for decades without any major safety signals; their only well-established adverse effects are contact dermatitis and staining of clothing.6 Although preclinical studies raised concerns that chemical sunscreens could be associated with endocrine, reproductive, and neurologic toxicities, to date there are no high-quality human studies demonstrating negative effects.7,8

However, exposure patterns have evolved. Sunscreen is recommended to be applied (and reapplied) daily. Also, chemical UV filters are used in many nonsunscreen products such as cosmetics, shampoos, fragrances, and plastics. In the United States, exposure to chemical sunscreens is ubiquitous; according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004, oxybenzone was detected in 97% of more than 2500 urine samples, implying systemic absorption but not harm.9

The FDA confirmed the implication of systemic absorption via 2 maximal usage trials published in 2019 and 2020.10,11 In both studies, several chemical sunscreens were applied at the recommended density of 2 mg/cm2 to 75% of the body surface area multiple times over 4 days. For all tested organic UV filters, blood levels exceeded the predetermined FDA cutoff (0.5 ng/mL), even after one application.10,11 What’s the takeaway? Simply that the FDA now requires additional safety data for chemical sunscreen filters5; the findings in no way imply any associated harm. Two potential mitigating factors are that no one applies sunscreen at 2 mg/cm2, and the FDA’s blood level cutoff was a general estimate not specific to sunscreens.4,12

Nevertheless, a good long-term safety record for sunscreens does not negate the need for enhanced safety data when there is clear evidence of systemic absorption. In the meantime, concerned patients should be counseled that the physical/mineral sunscreens containing zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are considered GRASE by the FDA; even in nanoparticle form, they generally have not been found to penetrate beneath the stratum corneum.7,13

Does sunscreen cause frontal fibrosing alopecia?

Dermatologists are confronting the conundrum of rising cases of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). Several theories on the pathogenesis of this idiopathic scarring alopecia have been raised, one of which involves increased use of sunscreen. Proposed explanations for sunscreen’s role in FFA include a lichenoid reaction inducing hair follicle autoimmunity through an unclear mechanism; a T cell–mediated allergic reaction, which is unlikely according to contact dermatitis experts14; reactive oxygen species production by titanium nanoparticles, yet titanium has been detected in hair follicles of both patients with FFA and controls15; and endocrine disruption following systemic absorption, which has not been supported by any high-quality human studies.7

An association between facial sunscreen use and FFA has been reported in case-control studies16; however, they have been criticized due to methodologic issues and biases, and they provide no evidence of causality.17,18 The jury remains out on the controversial association between sunscreen and FFA, with a need for more convincing data.

Does sunscreen impact coral reef health?

Coral reefs—crucial sources of aquatic biodiversity—are under attack from several different directions including climate change and pollution. As much as 14,000 tons of sunscreen enter coral reefs each year, and chemical sunscreen filters are detectable in waterways throughout the world—even in the Arctic.19,20 Thus, sunscreen has come under scrutiny as a potential environmental threat, particularly with coral bleaching.

Bleaching is a process in which corals exposed to an environmental stressor expel their symbiotic photosynthetic algae and turn white; if conditions fail to improve, the corals are vulnerable to death. In a highly cited 2016 study, coral larvae exposed to oxybenzone in artificial laboratory conditions displayed concentration-dependent mortality and decreased chlorophyll fluorescence, which suggested bleaching.19 These findings influenced legislation in Hawaii and other localities banning sunscreens containing oxybenzone. Problematically, the study has been criticized for acutely exposing the most susceptible coral life-forms to unrealistic oxybenzone concentrations; more broadly, there is no standardized approach to coral toxicity testing.21

The bigger picture (and elephant in the room) is that the primary cause of coral bleaching is undoubtedly climate change/ocean warming.7 More recent studies suggest that oxybenzone probably adds insult to injury for corals already debilitated by ocean warming.22,23

It has been posited that a narrow focus on sunscreens detracts attention from the climate issue.24 Individuals can take a number of actions to reduce their carbon footprint in an effort to preserve our environment, specifically coral reefs.25 Concerned patients should be counseled to use sunscreens containing the physical/mineral UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide, which are unlikely to contribute to coral bleaching as commercially formulated.7

Ongoing Questions

A lot of unknowns about sunscreen safety remain, and much hubbub has been made over studies that often are preliminary at best. At the time of this writing, absent a crystal ball, this author continues to wear chemical sunscreens; spends a lot more time worrying about their carbon footprint than what type of sunscreen to use at the beach; and believes the association of FFA with sunscreen is unlikely to be causal. Hopefully much-needed rigorous evidence will guide our future approach to sunscreen formulation and use.

Sunscreen is a cornerstone of skin cancer prevention. The first commercial sunscreen was developed nearly 100 years ago,1 yet questions and concerns about the safety of these essential topical photoprotective agents continue to occupy our minds. This article serves as an update on some of the big sunscreen questions, as informed by the available evidence.

Are sunscreens safe?

The story of sunscreen regulation in the United States is long and dry. The major pain point is that sunscreens are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as over-the-counter drugs rather than cosmetics (as in Europe).2 Regulatory hurdles created a situation wherein no new active sunscreen ingredient has been approved by the FDA since 1999, except ecamsule for use in one product line. There is hope that changes enacted under the CARES Act will streamline and expedite the sunscreen approval process in the future.3

Amid the ongoing regulatory slog, the FDA became interested in learning more about sunscreen safety. Specifically, they sought to determine the GRASE (generally regarded as safe and effective) status of the active ingredients in sunscreens. In 2019, only the inorganic (physical/mineral) UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide were considered GRASE.4 Trolamine salicylate and para-aminobenzoic acid were not GRASE, but they currently are not used in sunscreens in the United States. For all the remaining organic (chemical) filters, additional safety data were required to establish GRASE status.4 In 2024, the situation remains largely unchanged. Industry is working with the FDA on testing requirements.5

Why the focus on safety? After all, sunscreens have been used widely for decades without any major safety signals; their only well-established adverse effects are contact dermatitis and staining of clothing.6 Although preclinical studies raised concerns that chemical sunscreens could be associated with endocrine, reproductive, and neurologic toxicities, to date there are no high-quality human studies demonstrating negative effects.7,8

However, exposure patterns have evolved. Sunscreen is recommended to be applied (and reapplied) daily. Also, chemical UV filters are used in many nonsunscreen products such as cosmetics, shampoos, fragrances, and plastics. In the United States, exposure to chemical sunscreens is ubiquitous; according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004, oxybenzone was detected in 97% of more than 2500 urine samples, implying systemic absorption but not harm.9

The FDA confirmed the implication of systemic absorption via 2 maximal usage trials published in 2019 and 2020.10,11 In both studies, several chemical sunscreens were applied at the recommended density of 2 mg/cm2 to 75% of the body surface area multiple times over 4 days. For all tested organic UV filters, blood levels exceeded the predetermined FDA cutoff (0.5 ng/mL), even after one application.10,11 What’s the takeaway? Simply that the FDA now requires additional safety data for chemical sunscreen filters5; the findings in no way imply any associated harm. Two potential mitigating factors are that no one applies sunscreen at 2 mg/cm2, and the FDA’s blood level cutoff was a general estimate not specific to sunscreens.4,12

Nevertheless, a good long-term safety record for sunscreens does not negate the need for enhanced safety data when there is clear evidence of systemic absorption. In the meantime, concerned patients should be counseled that the physical/mineral sunscreens containing zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are considered GRASE by the FDA; even in nanoparticle form, they generally have not been found to penetrate beneath the stratum corneum.7,13

Does sunscreen cause frontal fibrosing alopecia?

Dermatologists are confronting the conundrum of rising cases of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). Several theories on the pathogenesis of this idiopathic scarring alopecia have been raised, one of which involves increased use of sunscreen. Proposed explanations for sunscreen’s role in FFA include a lichenoid reaction inducing hair follicle autoimmunity through an unclear mechanism; a T cell–mediated allergic reaction, which is unlikely according to contact dermatitis experts14; reactive oxygen species production by titanium nanoparticles, yet titanium has been detected in hair follicles of both patients with FFA and controls15; and endocrine disruption following systemic absorption, which has not been supported by any high-quality human studies.7

An association between facial sunscreen use and FFA has been reported in case-control studies16; however, they have been criticized due to methodologic issues and biases, and they provide no evidence of causality.17,18 The jury remains out on the controversial association between sunscreen and FFA, with a need for more convincing data.

Does sunscreen impact coral reef health?

Coral reefs—crucial sources of aquatic biodiversity—are under attack from several different directions including climate change and pollution. As much as 14,000 tons of sunscreen enter coral reefs each year, and chemical sunscreen filters are detectable in waterways throughout the world—even in the Arctic.19,20 Thus, sunscreen has come under scrutiny as a potential environmental threat, particularly with coral bleaching.

Bleaching is a process in which corals exposed to an environmental stressor expel their symbiotic photosynthetic algae and turn white; if conditions fail to improve, the corals are vulnerable to death. In a highly cited 2016 study, coral larvae exposed to oxybenzone in artificial laboratory conditions displayed concentration-dependent mortality and decreased chlorophyll fluorescence, which suggested bleaching.19 These findings influenced legislation in Hawaii and other localities banning sunscreens containing oxybenzone. Problematically, the study has been criticized for acutely exposing the most susceptible coral life-forms to unrealistic oxybenzone concentrations; more broadly, there is no standardized approach to coral toxicity testing.21

The bigger picture (and elephant in the room) is that the primary cause of coral bleaching is undoubtedly climate change/ocean warming.7 More recent studies suggest that oxybenzone probably adds insult to injury for corals already debilitated by ocean warming.22,23

It has been posited that a narrow focus on sunscreens detracts attention from the climate issue.24 Individuals can take a number of actions to reduce their carbon footprint in an effort to preserve our environment, specifically coral reefs.25 Concerned patients should be counseled to use sunscreens containing the physical/mineral UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide, which are unlikely to contribute to coral bleaching as commercially formulated.7

Ongoing Questions

A lot of unknowns about sunscreen safety remain, and much hubbub has been made over studies that often are preliminary at best. At the time of this writing, absent a crystal ball, this author continues to wear chemical sunscreens; spends a lot more time worrying about their carbon footprint than what type of sunscreen to use at the beach; and believes the association of FFA with sunscreen is unlikely to be causal. Hopefully much-needed rigorous evidence will guide our future approach to sunscreen formulation and use.

- Ma Y, Yoo J. History of sunscreen: an updated view. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1044-1049.

- Pantelic MN, Wong N, Kwa M, et al. Ultraviolet filters in the United States and European Union: a review of safety and implications for the future of US sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:632-646.

- Mohammad TF, Lim HW. The important role of dermatologists in public education on sunscreens. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:509-511.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use: proposed rule. Fed Regist. 2019;84:6204-6275.

- Lim HW, Mohammad TF, Wang SQ. Food and Drug Administration’s proposed sunscreen final administrative order: how does it affect sunscreens in the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E83-E84.

- Ekstein SF, Hylwa S. Sunscreens: a review of UV filters and their allergic potential. Dermatitis. 2023;34:176-190.

- Adler BL, DeLeo VA. Sunscreen safety: a review of recent studies on humans and the environment. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2020;9:1-9.

- Suh S, Pham C, Smith J, et al. The banned sunscreen ingredients and their impact on human health: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1033-1042.

- Calafat AM, Wong LY, Ye X, et al. Concentrations of the sunscreen agent benzophenone-3 in residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:893-897.

- Matta MK, Florian J, Zusterzeel R, et al. Effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:256-267.

- Matta MK, Zusterzeel R, Pilli NR, et al. Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2082-2091.

- Petersen B, Wulf HC. Application of sunscreen—theory and reality. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:96-101.

- Mohammed YH, Holmes A, Haridass IN, et al. Support for the safe use of zinc oxide nanoparticle sunscreens: lack of skin penetration or cellular toxicity after repeated application in volunteers. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:308-315.

- Felmingham C, Yip L, Tam M, et al. Allergy to sunscreen and leave-on facial products is not a likely causative mechanism in frontal fibrosing alopecia: perspective from contact allergy experts. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:481-482.

- Thompson CT, Chen ZQ, Kolivras A, et al. Identification of titanium dioxide on the hair shaft of patients with and without frontal fibrosing alopecia: a pilot study of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:216-217.

- Maghfour J, Ceresnie M, Olson J, et al. The association between frontal fibrosing alopecia, sunscreen, and moisturizers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:395-396.

- Seegobin SD, Tziotzios C, Stefanato CM, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia:there is no statistically significant association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1407-1408.

- Ramos PM, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Regarding methodologic concerns in clinical studies on frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E207-E208.

- Downs CA, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2016;70:265-288.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health. The National Academies Press; 2022.

- Mitchelmore CL, Burns EE, Conway A, et al. A critical review of organic ultraviolet filter exposure, hazard, and risk to corals. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2021;40:967-988.

- Vuckovic D, Tinoco AI, Ling L, et al. Conversion of oxybenzone sunscreen to phototoxic glucoside conjugates by sea anemones and corals. Science. 2022;376:644-648.

- Wijgerde T, van Ballegooijen M, Nijland R, et al. Adding insult to injury: effects of chronic oxybenzone exposure and elevated temperature on two reef-building corals. Sci Total Environ. 2020;733:139030.

- Sirois J. Examine all available evidence before making decisions on sunscreen ingredient bans. Sci Total Environ. 2019;674:211-212.

- United Nations. Actions for a healthy planet. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/actnow/ten-actions

- Ma Y, Yoo J. History of sunscreen: an updated view. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1044-1049.

- Pantelic MN, Wong N, Kwa M, et al. Ultraviolet filters in the United States and European Union: a review of safety and implications for the future of US sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:632-646.

- Mohammad TF, Lim HW. The important role of dermatologists in public education on sunscreens. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:509-511.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use: proposed rule. Fed Regist. 2019;84:6204-6275.

- Lim HW, Mohammad TF, Wang SQ. Food and Drug Administration’s proposed sunscreen final administrative order: how does it affect sunscreens in the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E83-E84.

- Ekstein SF, Hylwa S. Sunscreens: a review of UV filters and their allergic potential. Dermatitis. 2023;34:176-190.

- Adler BL, DeLeo VA. Sunscreen safety: a review of recent studies on humans and the environment. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2020;9:1-9.

- Suh S, Pham C, Smith J, et al. The banned sunscreen ingredients and their impact on human health: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1033-1042.

- Calafat AM, Wong LY, Ye X, et al. Concentrations of the sunscreen agent benzophenone-3 in residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:893-897.

- Matta MK, Florian J, Zusterzeel R, et al. Effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:256-267.

- Matta MK, Zusterzeel R, Pilli NR, et al. Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2082-2091.

- Petersen B, Wulf HC. Application of sunscreen—theory and reality. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:96-101.

- Mohammed YH, Holmes A, Haridass IN, et al. Support for the safe use of zinc oxide nanoparticle sunscreens: lack of skin penetration or cellular toxicity after repeated application in volunteers. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:308-315.

- Felmingham C, Yip L, Tam M, et al. Allergy to sunscreen and leave-on facial products is not a likely causative mechanism in frontal fibrosing alopecia: perspective from contact allergy experts. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:481-482.

- Thompson CT, Chen ZQ, Kolivras A, et al. Identification of titanium dioxide on the hair shaft of patients with and without frontal fibrosing alopecia: a pilot study of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:216-217.

- Maghfour J, Ceresnie M, Olson J, et al. The association between frontal fibrosing alopecia, sunscreen, and moisturizers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:395-396.

- Seegobin SD, Tziotzios C, Stefanato CM, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia:there is no statistically significant association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1407-1408.

- Ramos PM, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Regarding methodologic concerns in clinical studies on frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E207-E208.

- Downs CA, Kramarsky-Winter E, Segal R, et al. Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the US Virgin Islands. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2016;70:265-288.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health. The National Academies Press; 2022.

- Mitchelmore CL, Burns EE, Conway A, et al. A critical review of organic ultraviolet filter exposure, hazard, and risk to corals. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2021;40:967-988.

- Vuckovic D, Tinoco AI, Ling L, et al. Conversion of oxybenzone sunscreen to phototoxic glucoside conjugates by sea anemones and corals. Science. 2022;376:644-648.

- Wijgerde T, van Ballegooijen M, Nijland R, et al. Adding insult to injury: effects of chronic oxybenzone exposure and elevated temperature on two reef-building corals. Sci Total Environ. 2020;733:139030.

- Sirois J. Examine all available evidence before making decisions on sunscreen ingredient bans. Sci Total Environ. 2019;674:211-212.

- United Nations. Actions for a healthy planet. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/actnow/ten-actions

Clinical Manifestation of Degos Disease: Painful Penile Ulcers

To the Editor:

A 56-year-old man was referred to our Grand Rounds by another dermatologist in our health system for evaluation of a red scaly rash on the trunk that had been present for more than a year. More recently, over the course of approximately 9 months he experienced recurrent painful penile ulcers that lasted for approximately 4 weeks and then self-resolved. He had a medical history of central retinal vein occlusion, primary hyperparathyroidism, and nonspecific colitis. A family history was notable for lung cancer in the patient’s father and myelodysplastic syndrome and breast cancer in his mother; however, there was no family history of a similar rash. A bacterial culture of the penile ulcer was negative. Testing for antibodies against HIV and herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 and 2 was negative. Results of a serum VDRL test were nonreactive, which ruled out syphilis. The patient was treated by the referring dermatologist with azithromycin for possible chancroid without relief.

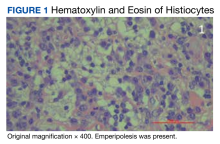

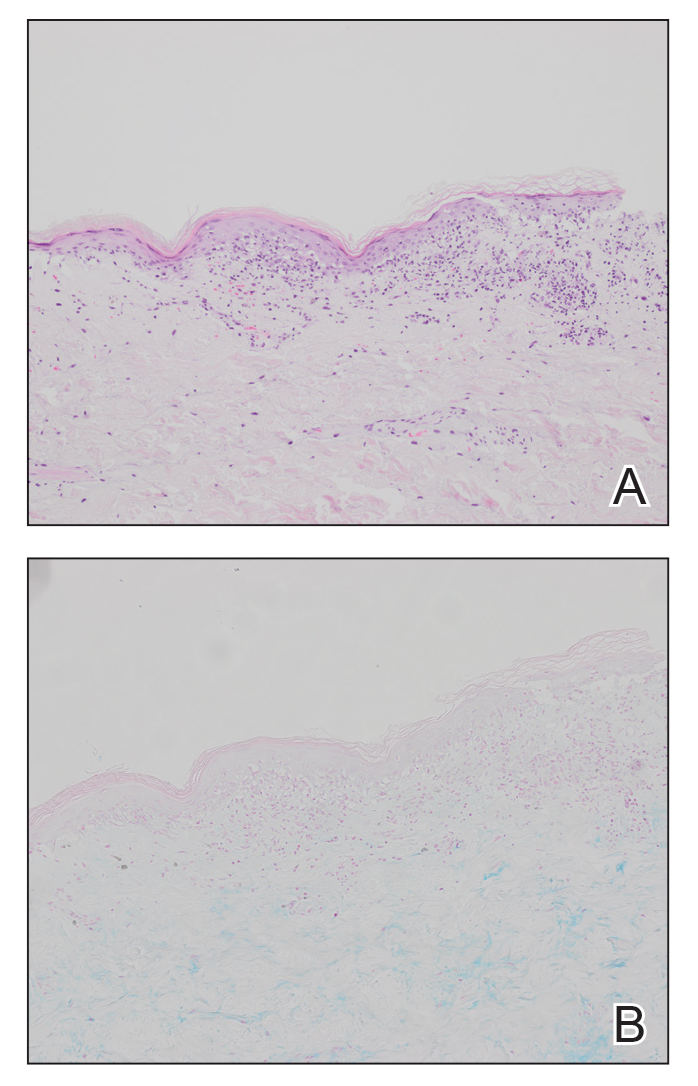

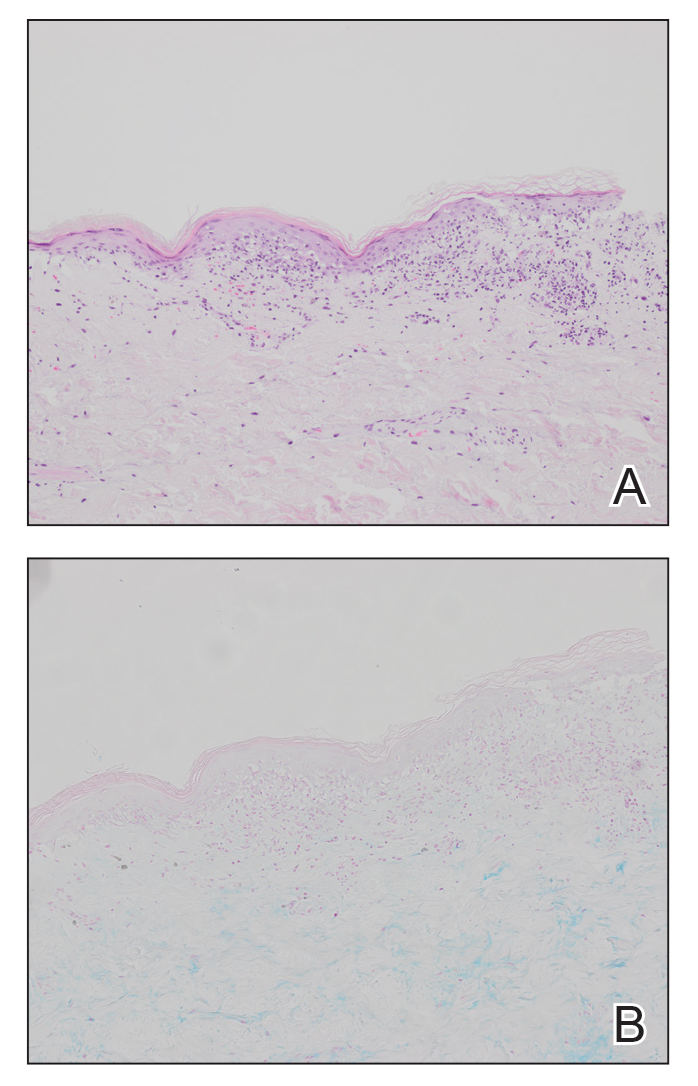

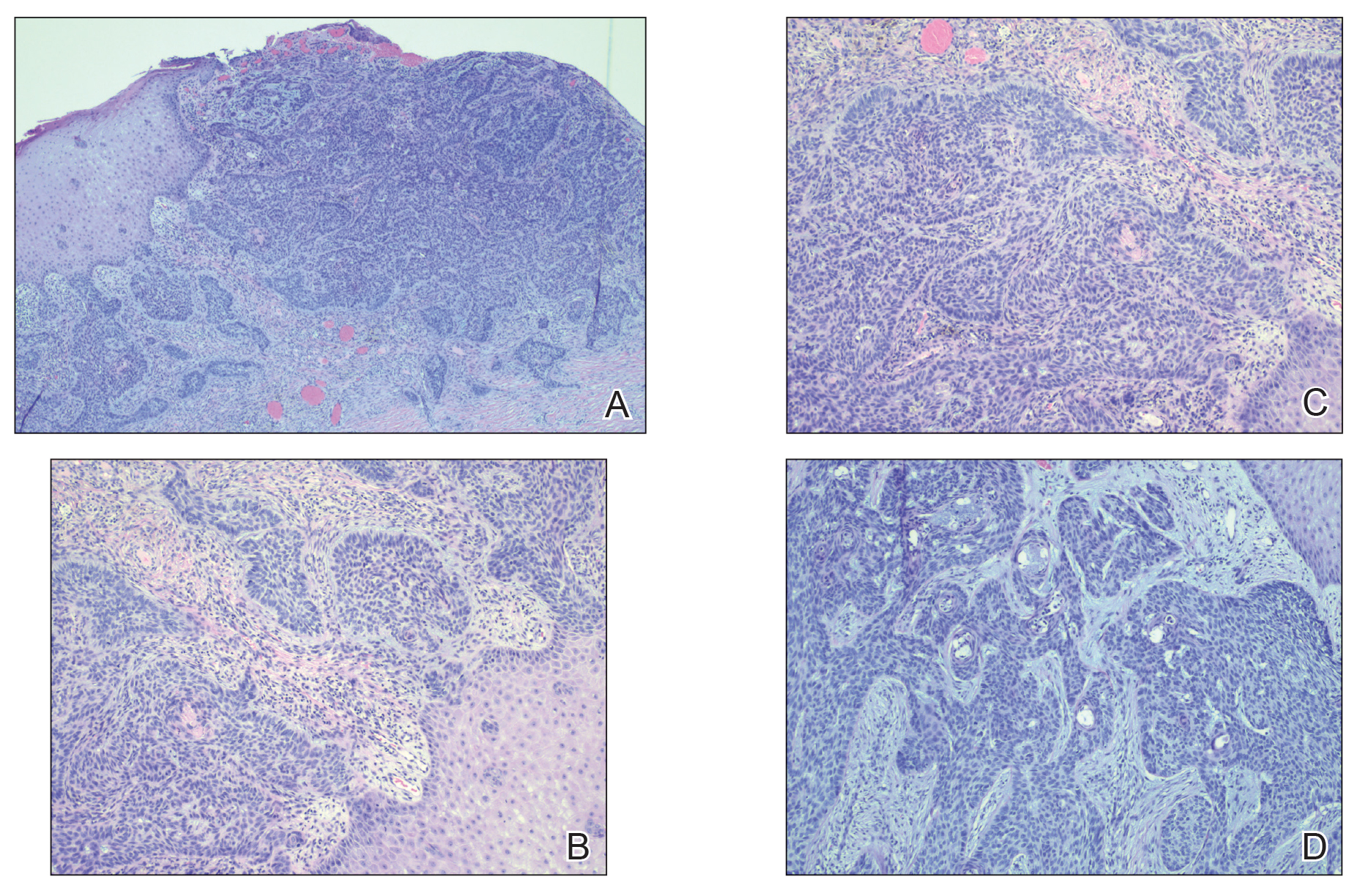

The patient was being followed by the referring dermatologist who initially was concerned for Degos disease based on clinical examination findings, prompting biopsy of a lesion on the back, which revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis, a sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and increased mucin—all highly suspicious for connective tissue disease (Figure 1). An antinuclear antibody test was positive, with a titer of 1:640. The patient was started on prednisone and referred to rheumatology; however, further evaluation by rheumatology for an autoimmune process—including anticardiolipin antibodies—was unremarkable. A few months prior to the current presentation, he also had mildly elevated liver function test results. A colonoscopy was performed, and a biopsy revealed nonspecific colitis. A biopsy of the penile ulcer also was nonspecific, showing only ulceration and acute and chronic inflammation. No epidermal interface change was seen. Results from a Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, Treponema pallidum immunostain, and HSV polymerase chain reaction were negative for fungal organisms, spirochetes, and HSV, respectively. The differential diagnosis included trauma, aphthous ulceration, and Behçet disease. Behçet disease was suspected by the referring dermatologist, and the patient was treated with colchicine, prednisone, pimecrolimus cream, and topical lidocaine; however, the lesions persisted, and he was subsequently referred to our Grand Rounds for further evaluation.

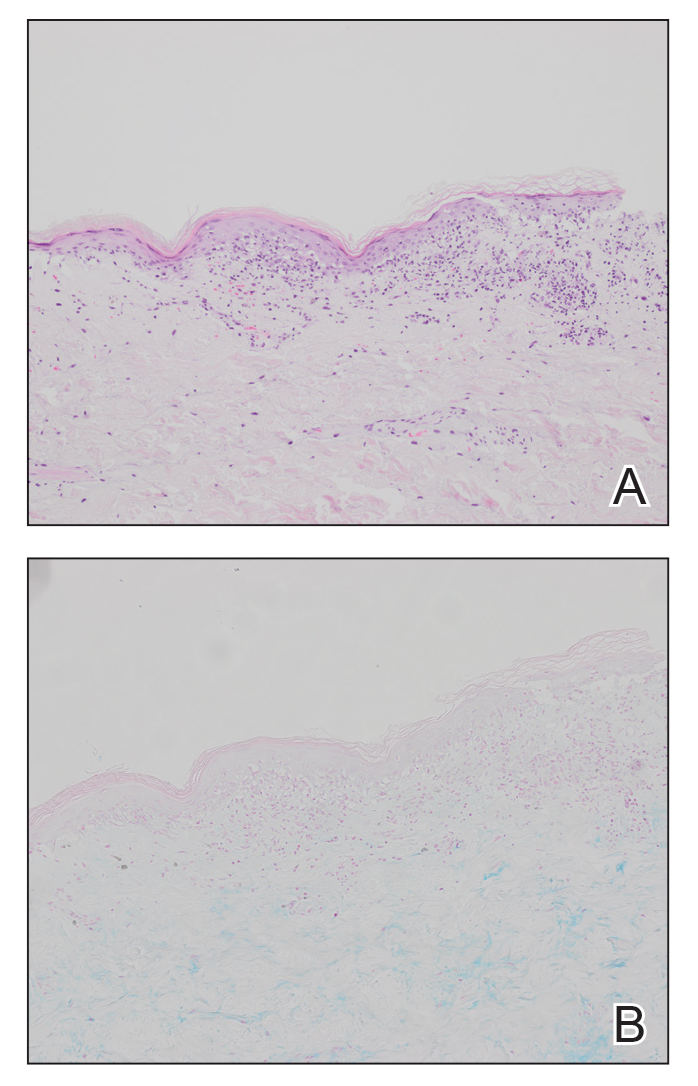

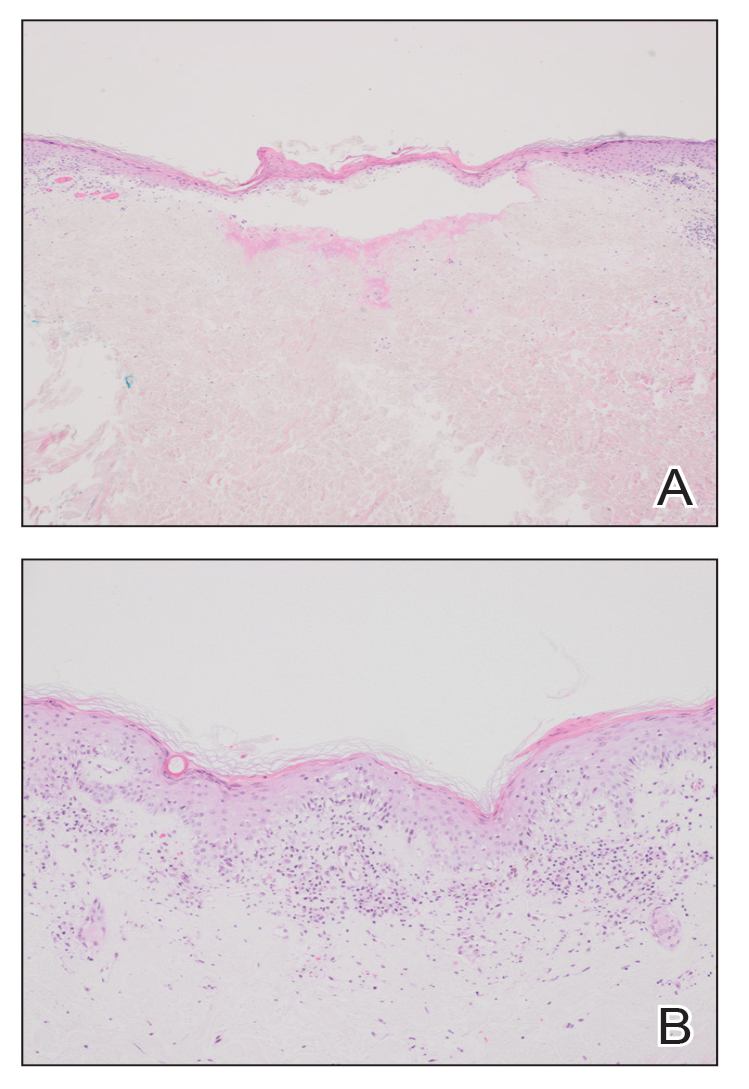

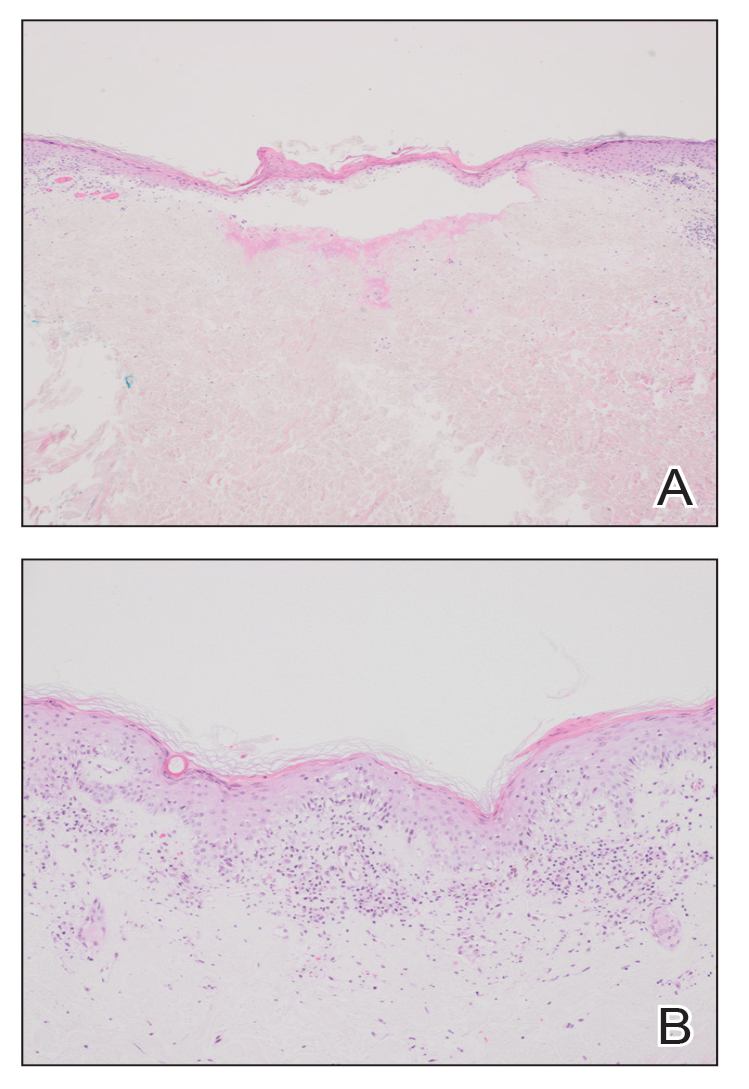

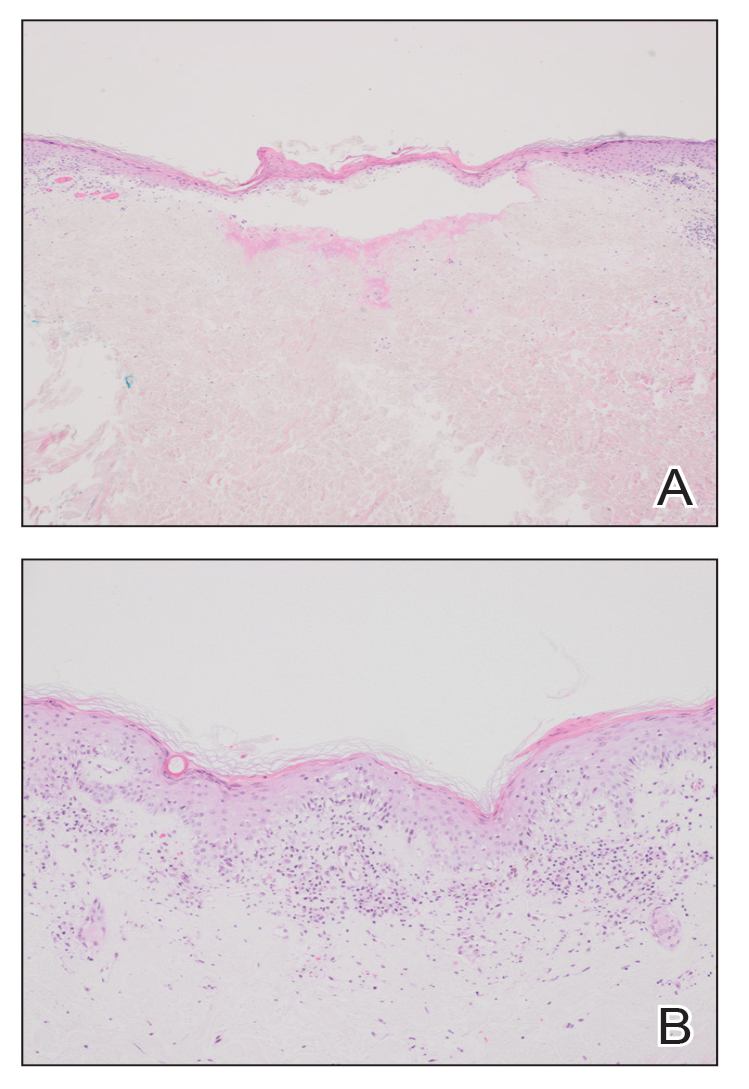

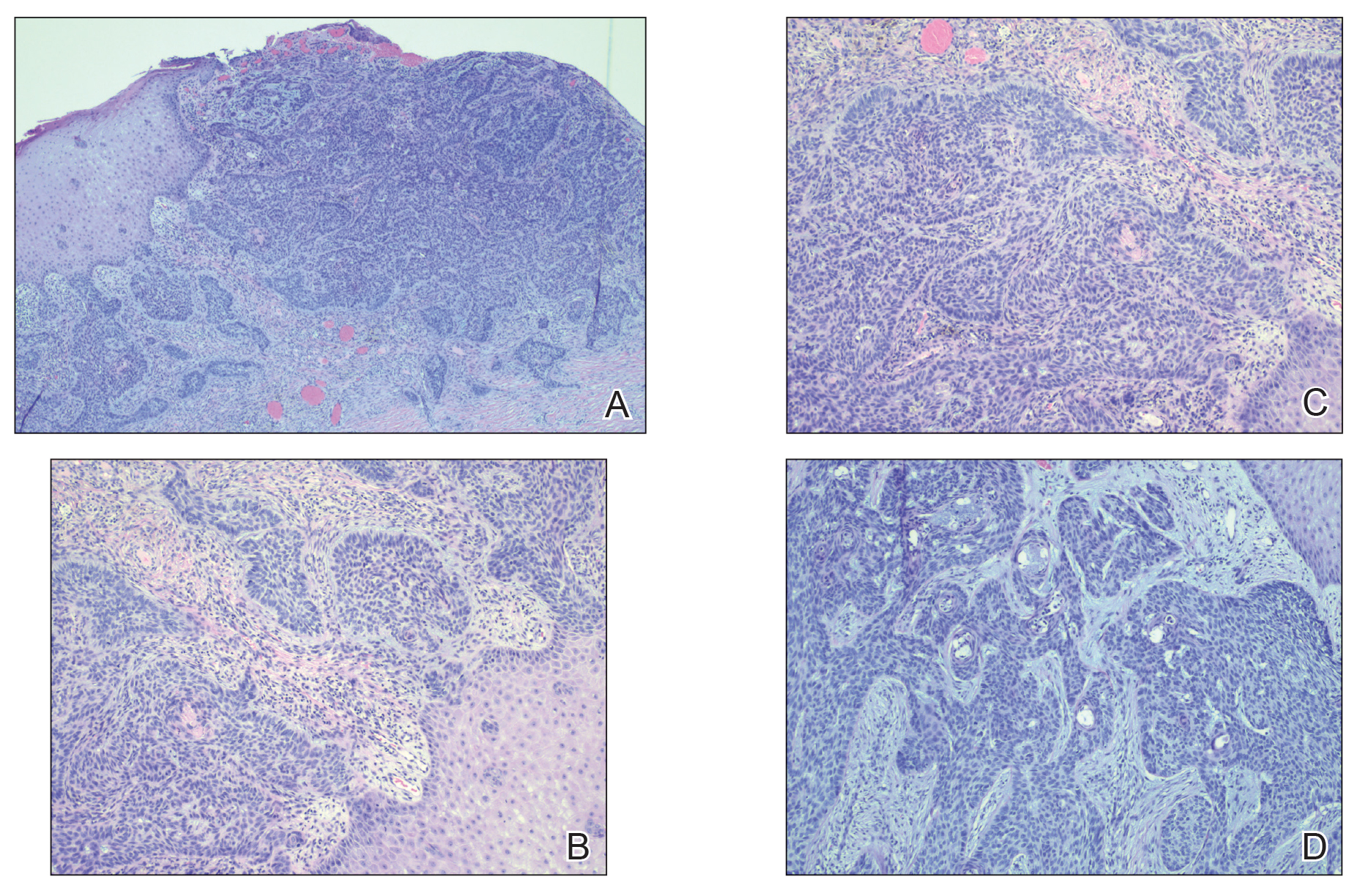

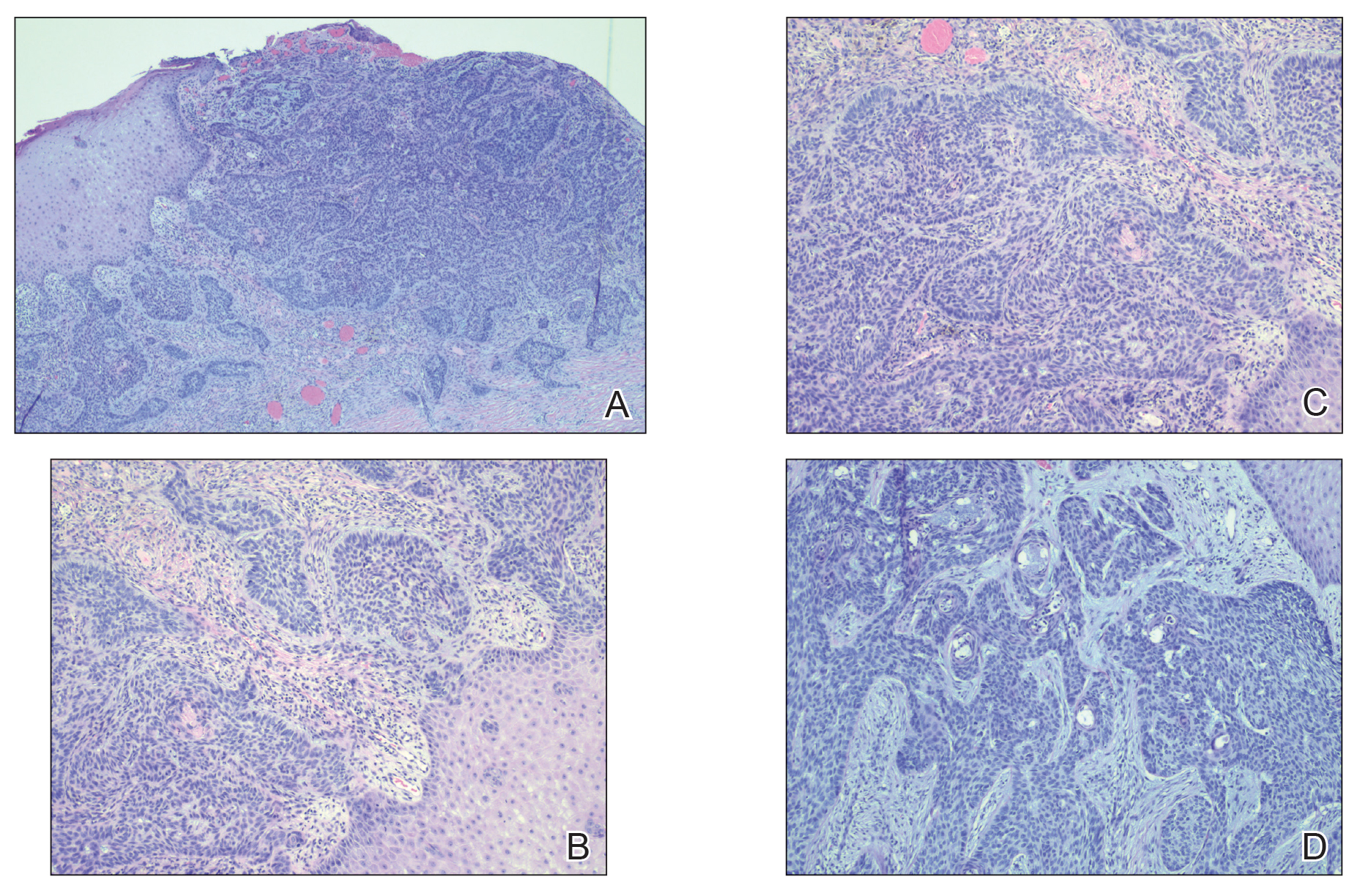

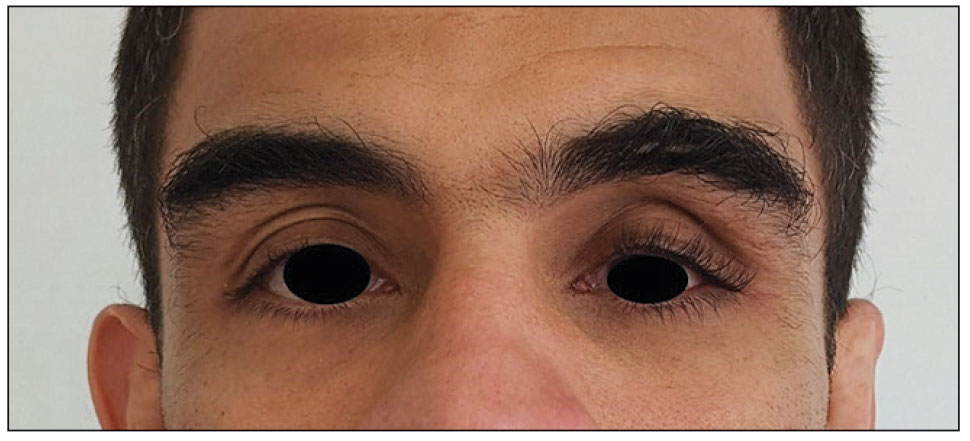

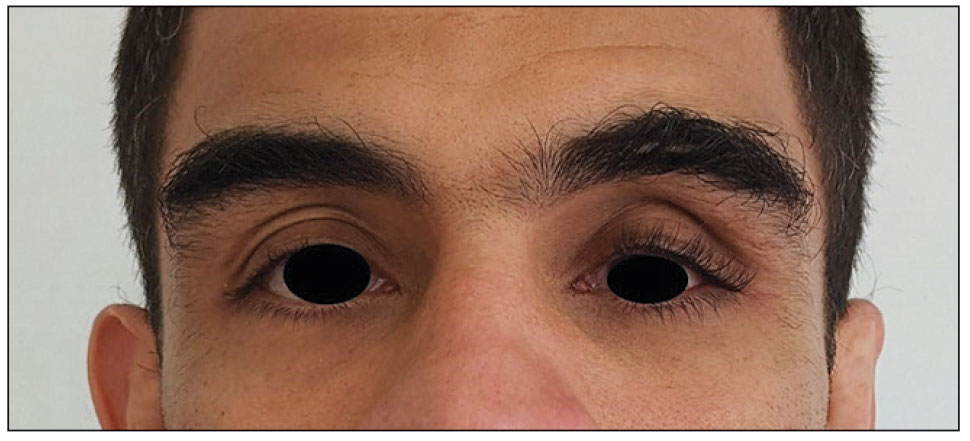

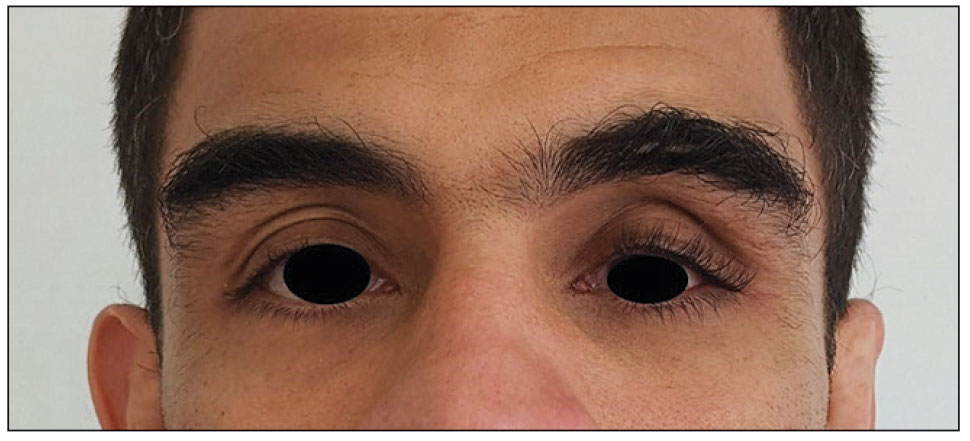

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed several small papules with white atrophic centers and erythematous rims on the trunk and extremities (Figure 2A). An ulceration was noted on the penile shaft (Figure 2B). Further evaluation for Behçet disease, including testing for pathergy and HLA-B51, was negative. Degos disease was strongly suspected clinically, and a repeat biopsy was performed of a lesion on the abdomen, which revealed central epidermal necrosis, atrophy, and parakeratosis with an underlying wedge-shaped dermal infarct surrounded by multiple small occluded dermal vessels, perivascular inflammation, and dermal edema (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was performed using antibodies against IgG, IgA, IgM, fibrinogen, albumin, and C3, which was negative. These findings from direct immunofluorescence and histopathology as well as the clinical presentation were considered compatible with Degos disease. The patient was started on aspirin and pentoxifylline. Pentoxifylline 400 mg twice daily appeared to lessen some of the pain. Pain management specialists started the patient on gabapentin.

Approximately 4 months after the Grand Rounds evaluation, during which time he continued treatment with pentoxifylline, he was admitted to the hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting. His condition acutely declined due to bowel perforation, and he was started on eculizumab 1200 mg every 14 days. Because of an increased risk for meningococcal meningitis while on this medication, he also was given erythromycin 500 mg twice daily prophylactically. He was being followed by hematology for the vasculopathy, and they were planning to monitor for any disease changes with computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 3 months, as well as echocardiogram every 6 months for any development of pericardial or pleural fibrosis. Approximately 1 month later, the patient was admitted to the hospital again but died after 1 week from gastrointestinal complications (approximately 22 months after the onset of the rash).

Degos disease (atrophic papulosis) is a rare small vessel vasculopathy of unknown etiology, but complement-mediated endothelial injury plays a role.1,2 It typically occurs in the fourth decade of life, with a slight female predominance.3,4 The skin lesions are characteristic and described as 5- to 10-mm papules with atrophic white centers and erythematous telangiectatic rims, most commonly on the upper body and typically sparing the head, palms, and soles.1 Penile ulceration is an uncommon cutaneous feature, with only a few cases reported in the literature.5,6 Approximately one-third of patients will have only skin lesions, but two-thirds will develop systemic involvement 1 to 2 years after onset, with the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system most commonly involved. For those with systemic involvement, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 55%, and the most common causes of death are bowel perforation, peritonitis, and stroke.3,4 Because some patients appear to never develop systemic complications, Theodoridis et al4 proposed that the disease be classified as either malignant atrophic papulosis or benign atrophic papulosis to indicate the malignant systemic form and the benign cutaneous form, respectively.

The histopathology of Degos disease changes as the lesions evolve.7 Early lesions show a superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate, possible interface dermatitis, and dermal mucin resembling lupus. The more fully developed lesions show a greater degree of inflammation and interface change as well as lymphocytic vasculitis. This stage also may have epidermal atrophy and early papillary dermal sclerosis resembling lichen sclerosus. The late-stage lesions, clinically observed as papules with atrophic white centers and surrounding erythema, show the classic pathology of wedge-shaped dermal sclerosis and central epidermal atrophy with surrounding hyperkeratosis. Interface dermatitis and dermal mucin can be seen in all stages, though mucin is diminished in the later stage.

Effective treatment options are limited; however, antithrombotics or compounds that facilitate blood perfusion, such as aspirin or pentoxifylline, initially can be used.1 Eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that prevents the cleavage of C5, has been used for salvage therapy,8 as in our case. Treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog that causes arterial vasodilation and inhibition of platelet aggregation, has been reported to improve bowel and cutaneous lesions, functional status, and neurologic symptoms.9

Our case highlights important features of Degos disease. First, it is important for both the clinician and the pathologist to recognize that the histopathology of Degos disease changes as the lesions evolve. In our case, although the lesions were characteristic of Degos disease clinically, the initial biopsy was suspicious for connective tissue disease, which led to an autoimmune evaluation that ultimately was unremarkable. Recognizing that early lesions of Degos disease can resemble connective tissue disease histologically could have prevented this delay in diagnosis. However, Degos disease has been reported in association with autoimmune diseases.10 Second, although penile ulceration is uncommon, it can be a prominent cutaneous manifestation of the disease. Finally, eculizumab and treprostinil are therapeutic options that have shown some efficacy in improving symptoms and cutaneous lesions.8,9

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-10

- Magro CM, Poe JC, Kim C, et al. Degos disease: a C5b-9/interferon-α-mediated endotheliopathy syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:599-610. doi:10.1309/AJCP66QIMFARLZKI

- Hu P, Mao Z, Liu C, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis with motor aphasia and intestinal perforation: a case report and review of published works. J Dermatol. 2018;45:723-726. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14280

- Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115. doi:10.1111/bjd.12642

- Thomson KF, Highet AS. Penile ulceration in fatal malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease). Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1320-1322. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03911.x

- Aydogan K, Alkan G, Karadogan Koran S, et al. Painful penile ulceration in a patient with malignant atrophic papulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:612-616. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01227.x

- Harvell JD, Williford PL, White WL. Benign cutaneous Degos’ disease: a case report with emphasis on histopathology as papules chronologically evolve. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:116-123. doi:10.1097/00000372-200104000-00006

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.015

- Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil—early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:52. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-52

- Burgin S, Stone JH, Shenoy-Bhangle AS, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 18-2014. A 32-year-old man with a rash, myalgia, and weakness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2327-2337. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc1304161

To the Editor:

A 56-year-old man was referred to our Grand Rounds by another dermatologist in our health system for evaluation of a red scaly rash on the trunk that had been present for more than a year. More recently, over the course of approximately 9 months he experienced recurrent painful penile ulcers that lasted for approximately 4 weeks and then self-resolved. He had a medical history of central retinal vein occlusion, primary hyperparathyroidism, and nonspecific colitis. A family history was notable for lung cancer in the patient’s father and myelodysplastic syndrome and breast cancer in his mother; however, there was no family history of a similar rash. A bacterial culture of the penile ulcer was negative. Testing for antibodies against HIV and herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 and 2 was negative. Results of a serum VDRL test were nonreactive, which ruled out syphilis. The patient was treated by the referring dermatologist with azithromycin for possible chancroid without relief.

The patient was being followed by the referring dermatologist who initially was concerned for Degos disease based on clinical examination findings, prompting biopsy of a lesion on the back, which revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis, a sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and increased mucin—all highly suspicious for connective tissue disease (Figure 1). An antinuclear antibody test was positive, with a titer of 1:640. The patient was started on prednisone and referred to rheumatology; however, further evaluation by rheumatology for an autoimmune process—including anticardiolipin antibodies—was unremarkable. A few months prior to the current presentation, he also had mildly elevated liver function test results. A colonoscopy was performed, and a biopsy revealed nonspecific colitis. A biopsy of the penile ulcer also was nonspecific, showing only ulceration and acute and chronic inflammation. No epidermal interface change was seen. Results from a Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, Treponema pallidum immunostain, and HSV polymerase chain reaction were negative for fungal organisms, spirochetes, and HSV, respectively. The differential diagnosis included trauma, aphthous ulceration, and Behçet disease. Behçet disease was suspected by the referring dermatologist, and the patient was treated with colchicine, prednisone, pimecrolimus cream, and topical lidocaine; however, the lesions persisted, and he was subsequently referred to our Grand Rounds for further evaluation.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed several small papules with white atrophic centers and erythematous rims on the trunk and extremities (Figure 2A). An ulceration was noted on the penile shaft (Figure 2B). Further evaluation for Behçet disease, including testing for pathergy and HLA-B51, was negative. Degos disease was strongly suspected clinically, and a repeat biopsy was performed of a lesion on the abdomen, which revealed central epidermal necrosis, atrophy, and parakeratosis with an underlying wedge-shaped dermal infarct surrounded by multiple small occluded dermal vessels, perivascular inflammation, and dermal edema (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was performed using antibodies against IgG, IgA, IgM, fibrinogen, albumin, and C3, which was negative. These findings from direct immunofluorescence and histopathology as well as the clinical presentation were considered compatible with Degos disease. The patient was started on aspirin and pentoxifylline. Pentoxifylline 400 mg twice daily appeared to lessen some of the pain. Pain management specialists started the patient on gabapentin.

Approximately 4 months after the Grand Rounds evaluation, during which time he continued treatment with pentoxifylline, he was admitted to the hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting. His condition acutely declined due to bowel perforation, and he was started on eculizumab 1200 mg every 14 days. Because of an increased risk for meningococcal meningitis while on this medication, he also was given erythromycin 500 mg twice daily prophylactically. He was being followed by hematology for the vasculopathy, and they were planning to monitor for any disease changes with computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 3 months, as well as echocardiogram every 6 months for any development of pericardial or pleural fibrosis. Approximately 1 month later, the patient was admitted to the hospital again but died after 1 week from gastrointestinal complications (approximately 22 months after the onset of the rash).

Degos disease (atrophic papulosis) is a rare small vessel vasculopathy of unknown etiology, but complement-mediated endothelial injury plays a role.1,2 It typically occurs in the fourth decade of life, with a slight female predominance.3,4 The skin lesions are characteristic and described as 5- to 10-mm papules with atrophic white centers and erythematous telangiectatic rims, most commonly on the upper body and typically sparing the head, palms, and soles.1 Penile ulceration is an uncommon cutaneous feature, with only a few cases reported in the literature.5,6 Approximately one-third of patients will have only skin lesions, but two-thirds will develop systemic involvement 1 to 2 years after onset, with the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system most commonly involved. For those with systemic involvement, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 55%, and the most common causes of death are bowel perforation, peritonitis, and stroke.3,4 Because some patients appear to never develop systemic complications, Theodoridis et al4 proposed that the disease be classified as either malignant atrophic papulosis or benign atrophic papulosis to indicate the malignant systemic form and the benign cutaneous form, respectively.

The histopathology of Degos disease changes as the lesions evolve.7 Early lesions show a superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate, possible interface dermatitis, and dermal mucin resembling lupus. The more fully developed lesions show a greater degree of inflammation and interface change as well as lymphocytic vasculitis. This stage also may have epidermal atrophy and early papillary dermal sclerosis resembling lichen sclerosus. The late-stage lesions, clinically observed as papules with atrophic white centers and surrounding erythema, show the classic pathology of wedge-shaped dermal sclerosis and central epidermal atrophy with surrounding hyperkeratosis. Interface dermatitis and dermal mucin can be seen in all stages, though mucin is diminished in the later stage.

Effective treatment options are limited; however, antithrombotics or compounds that facilitate blood perfusion, such as aspirin or pentoxifylline, initially can be used.1 Eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that prevents the cleavage of C5, has been used for salvage therapy,8 as in our case. Treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog that causes arterial vasodilation and inhibition of platelet aggregation, has been reported to improve bowel and cutaneous lesions, functional status, and neurologic symptoms.9

Our case highlights important features of Degos disease. First, it is important for both the clinician and the pathologist to recognize that the histopathology of Degos disease changes as the lesions evolve. In our case, although the lesions were characteristic of Degos disease clinically, the initial biopsy was suspicious for connective tissue disease, which led to an autoimmune evaluation that ultimately was unremarkable. Recognizing that early lesions of Degos disease can resemble connective tissue disease histologically could have prevented this delay in diagnosis. However, Degos disease has been reported in association with autoimmune diseases.10 Second, although penile ulceration is uncommon, it can be a prominent cutaneous manifestation of the disease. Finally, eculizumab and treprostinil are therapeutic options that have shown some efficacy in improving symptoms and cutaneous lesions.8,9

To the Editor:

A 56-year-old man was referred to our Grand Rounds by another dermatologist in our health system for evaluation of a red scaly rash on the trunk that had been present for more than a year. More recently, over the course of approximately 9 months he experienced recurrent painful penile ulcers that lasted for approximately 4 weeks and then self-resolved. He had a medical history of central retinal vein occlusion, primary hyperparathyroidism, and nonspecific colitis. A family history was notable for lung cancer in the patient’s father and myelodysplastic syndrome and breast cancer in his mother; however, there was no family history of a similar rash. A bacterial culture of the penile ulcer was negative. Testing for antibodies against HIV and herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 and 2 was negative. Results of a serum VDRL test were nonreactive, which ruled out syphilis. The patient was treated by the referring dermatologist with azithromycin for possible chancroid without relief.

The patient was being followed by the referring dermatologist who initially was concerned for Degos disease based on clinical examination findings, prompting biopsy of a lesion on the back, which revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis, a sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and increased mucin—all highly suspicious for connective tissue disease (Figure 1). An antinuclear antibody test was positive, with a titer of 1:640. The patient was started on prednisone and referred to rheumatology; however, further evaluation by rheumatology for an autoimmune process—including anticardiolipin antibodies—was unremarkable. A few months prior to the current presentation, he also had mildly elevated liver function test results. A colonoscopy was performed, and a biopsy revealed nonspecific colitis. A biopsy of the penile ulcer also was nonspecific, showing only ulceration and acute and chronic inflammation. No epidermal interface change was seen. Results from a Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, Treponema pallidum immunostain, and HSV polymerase chain reaction were negative for fungal organisms, spirochetes, and HSV, respectively. The differential diagnosis included trauma, aphthous ulceration, and Behçet disease. Behçet disease was suspected by the referring dermatologist, and the patient was treated with colchicine, prednisone, pimecrolimus cream, and topical lidocaine; however, the lesions persisted, and he was subsequently referred to our Grand Rounds for further evaluation.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed several small papules with white atrophic centers and erythematous rims on the trunk and extremities (Figure 2A). An ulceration was noted on the penile shaft (Figure 2B). Further evaluation for Behçet disease, including testing for pathergy and HLA-B51, was negative. Degos disease was strongly suspected clinically, and a repeat biopsy was performed of a lesion on the abdomen, which revealed central epidermal necrosis, atrophy, and parakeratosis with an underlying wedge-shaped dermal infarct surrounded by multiple small occluded dermal vessels, perivascular inflammation, and dermal edema (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was performed using antibodies against IgG, IgA, IgM, fibrinogen, albumin, and C3, which was negative. These findings from direct immunofluorescence and histopathology as well as the clinical presentation were considered compatible with Degos disease. The patient was started on aspirin and pentoxifylline. Pentoxifylline 400 mg twice daily appeared to lessen some of the pain. Pain management specialists started the patient on gabapentin.

Approximately 4 months after the Grand Rounds evaluation, during which time he continued treatment with pentoxifylline, he was admitted to the hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting. His condition acutely declined due to bowel perforation, and he was started on eculizumab 1200 mg every 14 days. Because of an increased risk for meningococcal meningitis while on this medication, he also was given erythromycin 500 mg twice daily prophylactically. He was being followed by hematology for the vasculopathy, and they were planning to monitor for any disease changes with computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 3 months, as well as echocardiogram every 6 months for any development of pericardial or pleural fibrosis. Approximately 1 month later, the patient was admitted to the hospital again but died after 1 week from gastrointestinal complications (approximately 22 months after the onset of the rash).

Degos disease (atrophic papulosis) is a rare small vessel vasculopathy of unknown etiology, but complement-mediated endothelial injury plays a role.1,2 It typically occurs in the fourth decade of life, with a slight female predominance.3,4 The skin lesions are characteristic and described as 5- to 10-mm papules with atrophic white centers and erythematous telangiectatic rims, most commonly on the upper body and typically sparing the head, palms, and soles.1 Penile ulceration is an uncommon cutaneous feature, with only a few cases reported in the literature.5,6 Approximately one-third of patients will have only skin lesions, but two-thirds will develop systemic involvement 1 to 2 years after onset, with the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system most commonly involved. For those with systemic involvement, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 55%, and the most common causes of death are bowel perforation, peritonitis, and stroke.3,4 Because some patients appear to never develop systemic complications, Theodoridis et al4 proposed that the disease be classified as either malignant atrophic papulosis or benign atrophic papulosis to indicate the malignant systemic form and the benign cutaneous form, respectively.

The histopathology of Degos disease changes as the lesions evolve.7 Early lesions show a superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate, possible interface dermatitis, and dermal mucin resembling lupus. The more fully developed lesions show a greater degree of inflammation and interface change as well as lymphocytic vasculitis. This stage also may have epidermal atrophy and early papillary dermal sclerosis resembling lichen sclerosus. The late-stage lesions, clinically observed as papules with atrophic white centers and surrounding erythema, show the classic pathology of wedge-shaped dermal sclerosis and central epidermal atrophy with surrounding hyperkeratosis. Interface dermatitis and dermal mucin can be seen in all stages, though mucin is diminished in the later stage.

Effective treatment options are limited; however, antithrombotics or compounds that facilitate blood perfusion, such as aspirin or pentoxifylline, initially can be used.1 Eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that prevents the cleavage of C5, has been used for salvage therapy,8 as in our case. Treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog that causes arterial vasodilation and inhibition of platelet aggregation, has been reported to improve bowel and cutaneous lesions, functional status, and neurologic symptoms.9

Our case highlights important features of Degos disease. First, it is important for both the clinician and the pathologist to recognize that the histopathology of Degos disease changes as the lesions evolve. In our case, although the lesions were characteristic of Degos disease clinically, the initial biopsy was suspicious for connective tissue disease, which led to an autoimmune evaluation that ultimately was unremarkable. Recognizing that early lesions of Degos disease can resemble connective tissue disease histologically could have prevented this delay in diagnosis. However, Degos disease has been reported in association with autoimmune diseases.10 Second, although penile ulceration is uncommon, it can be a prominent cutaneous manifestation of the disease. Finally, eculizumab and treprostinil are therapeutic options that have shown some efficacy in improving symptoms and cutaneous lesions.8,9

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-10

- Magro CM, Poe JC, Kim C, et al. Degos disease: a C5b-9/interferon-α-mediated endotheliopathy syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:599-610. doi:10.1309/AJCP66QIMFARLZKI

- Hu P, Mao Z, Liu C, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis with motor aphasia and intestinal perforation: a case report and review of published works. J Dermatol. 2018;45:723-726. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14280

- Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115. doi:10.1111/bjd.12642

- Thomson KF, Highet AS. Penile ulceration in fatal malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease). Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1320-1322. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03911.x

- Aydogan K, Alkan G, Karadogan Koran S, et al. Painful penile ulceration in a patient with malignant atrophic papulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:612-616. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01227.x

- Harvell JD, Williford PL, White WL. Benign cutaneous Degos’ disease: a case report with emphasis on histopathology as papules chronologically evolve. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:116-123. doi:10.1097/00000372-200104000-00006

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.015

- Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil—early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:52. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-52

- Burgin S, Stone JH, Shenoy-Bhangle AS, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 18-2014. A 32-year-old man with a rash, myalgia, and weakness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2327-2337. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc1304161

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-10

- Magro CM, Poe JC, Kim C, et al. Degos disease: a C5b-9/interferon-α-mediated endotheliopathy syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:599-610. doi:10.1309/AJCP66QIMFARLZKI

- Hu P, Mao Z, Liu C, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis with motor aphasia and intestinal perforation: a case report and review of published works. J Dermatol. 2018;45:723-726. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14280

- Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115. doi:10.1111/bjd.12642

- Thomson KF, Highet AS. Penile ulceration in fatal malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease). Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1320-1322. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03911.x

- Aydogan K, Alkan G, Karadogan Koran S, et al. Painful penile ulceration in a patient with malignant atrophic papulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:612-616. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01227.x

- Harvell JD, Williford PL, White WL. Benign cutaneous Degos’ disease: a case report with emphasis on histopathology as papules chronologically evolve. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:116-123. doi:10.1097/00000372-200104000-00006

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.015

- Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil—early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:52. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-52

- Burgin S, Stone JH, Shenoy-Bhangle AS, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 18-2014. A 32-year-old man with a rash, myalgia, and weakness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2327-2337. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc1304161

PRACTICE POINTS

- Papules with atrophic white centers and erythematous telangiectatic rims are the characteristic skin lesions found in Degos disease.

- A painful penile ulceration also may occur in Degos disease, though it is uncommon.

- The histopathology of skin lesions changes as the lesions evolve. Early lesions may resemble connective tissue disease. Late lesions show the classic pathology of wedge-shaped dermal sclerosis.

Commentary: Evaluating Recent BC Treatment Trials, May 2024

The class of CDK 4/6 inhibitors represents a significant advance in the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancer. All three CDK 4/6 inhibitors (palbociclib, abemaciclib, and ribociclib) are approved in combination with endocrine therapy in the metastatic setting. As drugs show promise in later-stage disease, they are then often studied in the curative space. Presently, abemaciclib is the only CDK 4/6 inhibitor that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HR-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative, node-positive, high-risk early breast cancer, based on results from the monarchE trial, which demonstrated invasive disease-free survival benefit with the addition of 2 years of abemaciclib to endocrine therapy. At 4 years, the absolute difference in invasive disease-free survival (IDFS) between the groups was 6.4% (85.8% in the abemaciclib + endocrine therapy group vs 79.4% in the endocrine therapy–alone group).[3] In contrast, the PENELOPE-B and PALLAS trials did not show benefit with the addition of palbociclib to endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting.[4,5] The phase 3 NATALEE trial randomly assigned patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer to ribociclib (400 mg daily for 3 weeks followed by 1 week off for 3 years) plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor (NSAI) or an NSAI alone. At the time of prespecified interim analysis, among 5101 patients, ribociclib + NSAI led to a significant improvement in IDFS compared with endocrine therapy alone (3-year IDFS was 90.4% vs 87.1%; hazard ratio 0.75; 95% CI 0.62-0.91; P = .003). It is certainly noteworthy that the trial design, endocrine therapies, and patient populations differed between these adjuvant studies; for example, NATALEE included a lower-risk population, and all patients received an NSAI (in monarchE approximately 30% received tamoxifen). The current results of NATALEE are encouraging; an absolute benefit of 3.3% should be considered and weighed against toxicities and cost, and longer follow-up is needed to further elucidate the role of ribociclib in the adjuvant space.

The meaningful impact of achieving a pathologic complete response (pCR) has been demonstrated in various prior studies. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy informs prognosis and helps tailor adjuvant therapy, the latter of which is particularly relevant for the HER2-positive subtype. Strategies to identify patients who are more likely to achieve pCR and predictors of early responders may aid in improving efficacy outcomes and limiting toxicities. TRAIN-3 is a single-arm, phase 2 study that included 235 and 232 patients with stage II/III HR-/HER2+ and HR+/HER2+ breast cancer, respectively, undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (weekly paclitaxel D1 and D8/carboplatin AUC 6 D1/trastuzumab D1/pertuzumab D1 every 3 weeks for up to nine cycles), and was designed to evaluate radiologic and pathologic response rates and event-free survival. Response was monitored by breast MRI every 3 cycles and lymph node biopsy. Among patients with HR-/HER2+ tumors, 84 (36%; 95% CI 30-43) achieved a radiologic complete response after one to three cycles, of whom the majority (88%; 95% CI 79-94) had pCR. Patients with HR+/HER2+ tumors did not show the same degree of benefit with an MRI-based monitoring strategy; among the 138 patients (59%; 95% CI 53-66) who had a complete radiologic response after one to nine cycles, 73 (53%; 95% CI 44-61) had pCR. Additional imaging-guided modalities being studied to tailor and optimize treatment include [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-PET-CT and volumetric MRI, in the PHERGain and I-SPY trials, respectively.[6,7]

Additional References:

- Giuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al. Effect of axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918-926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470 Source

- Bartels SAL, Donker M, Poncet C, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized controlled EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2159-2165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01565 Source

- Johnston SRD, Toi M, O'Shaughnessy J, et al, on behalf of the monarchE Committee Members. Abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, node-positive, high-risk early breast cancer (monarchE): Results from a preplanned interim analysis of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:77-90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00694-5 Source

- Loibl S, Marmé F, Martin M, et al. Palbociclib for residual high-risk invasive HR-positive and HER2-negative early breast cancer—The Penelope-B trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1518-1530. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03639 Source

- Gnant M, Dueck AC, Frantal S, et al, on behalf of the PALLAS groups and investigators. Adjuvant palbociclib for early breast cancer: The PALLAS trial results (ABCSG-42/AFT-05/BIG-14-03). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:282-293. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02554 Source

- Pérez-García JM, Cortés J, Ruiz-Borrego M, et al, on behalf of the PHERGain trial investigators. 3-year invasive disease-free survival with chemotherapy de-escalation using an 18F-FDG-PET-based, pathological complete response-adapted strategy in HER2-positive early breast cancer (PHERGain): A randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2024;403:1649-1659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00054-0 Source

- Hylton NM, Gatsonis CA, Rosen MA, et al, for the ACRIN 6657 trial team and I-SPY 1 trial investigators. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: Functional tumor volume by MR imaging predicts recurrence-free survival-results from the ACRIN 6657/CALGB 150007 I-SPY 1 trial. Radiology. 2016;279:44-55. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150013 Source

The class of CDK 4/6 inhibitors represents a significant advance in the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancer. All three CDK 4/6 inhibitors (palbociclib, abemaciclib, and ribociclib) are approved in combination with endocrine therapy in the metastatic setting. As drugs show promise in later-stage disease, they are then often studied in the curative space. Presently, abemaciclib is the only CDK 4/6 inhibitor that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HR-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative, node-positive, high-risk early breast cancer, based on results from the monarchE trial, which demonstrated invasive disease-free survival benefit with the addition of 2 years of abemaciclib to endocrine therapy. At 4 years, the absolute difference in invasive disease-free survival (IDFS) between the groups was 6.4% (85.8% in the abemaciclib + endocrine therapy group vs 79.4% in the endocrine therapy–alone group).[3] In contrast, the PENELOPE-B and PALLAS trials did not show benefit with the addition of palbociclib to endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting.[4,5] The phase 3 NATALEE trial randomly assigned patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer to ribociclib (400 mg daily for 3 weeks followed by 1 week off for 3 years) plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor (NSAI) or an NSAI alone. At the time of prespecified interim analysis, among 5101 patients, ribociclib + NSAI led to a significant improvement in IDFS compared with endocrine therapy alone (3-year IDFS was 90.4% vs 87.1%; hazard ratio 0.75; 95% CI 0.62-0.91; P = .003). It is certainly noteworthy that the trial design, endocrine therapies, and patient populations differed between these adjuvant studies; for example, NATALEE included a lower-risk population, and all patients received an NSAI (in monarchE approximately 30% received tamoxifen). The current results of NATALEE are encouraging; an absolute benefit of 3.3% should be considered and weighed against toxicities and cost, and longer follow-up is needed to further elucidate the role of ribociclib in the adjuvant space.

The meaningful impact of achieving a pathologic complete response (pCR) has been demonstrated in various prior studies. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy informs prognosis and helps tailor adjuvant therapy, the latter of which is particularly relevant for the HER2-positive subtype. Strategies to identify patients who are more likely to achieve pCR and predictors of early responders may aid in improving efficacy outcomes and limiting toxicities. TRAIN-3 is a single-arm, phase 2 study that included 235 and 232 patients with stage II/III HR-/HER2+ and HR+/HER2+ breast cancer, respectively, undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (weekly paclitaxel D1 and D8/carboplatin AUC 6 D1/trastuzumab D1/pertuzumab D1 every 3 weeks for up to nine cycles), and was designed to evaluate radiologic and pathologic response rates and event-free survival. Response was monitored by breast MRI every 3 cycles and lymph node biopsy. Among patients with HR-/HER2+ tumors, 84 (36%; 95% CI 30-43) achieved a radiologic complete response after one to three cycles, of whom the majority (88%; 95% CI 79-94) had pCR. Patients with HR+/HER2+ tumors did not show the same degree of benefit with an MRI-based monitoring strategy; among the 138 patients (59%; 95% CI 53-66) who had a complete radiologic response after one to nine cycles, 73 (53%; 95% CI 44-61) had pCR. Additional imaging-guided modalities being studied to tailor and optimize treatment include [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-PET-CT and volumetric MRI, in the PHERGain and I-SPY trials, respectively.[6,7]

Additional References:

- Giuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al. Effect of axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918-926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470 Source

- Bartels SAL, Donker M, Poncet C, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized controlled EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2159-2165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01565 Source

- Johnston SRD, Toi M, O'Shaughnessy J, et al, on behalf of the monarchE Committee Members. Abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, node-positive, high-risk early breast cancer (monarchE): Results from a preplanned interim analysis of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:77-90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00694-5 Source

- Loibl S, Marmé F, Martin M, et al. Palbociclib for residual high-risk invasive HR-positive and HER2-negative early breast cancer—The Penelope-B trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1518-1530. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03639 Source

- Gnant M, Dueck AC, Frantal S, et al, on behalf of the PALLAS groups and investigators. Adjuvant palbociclib for early breast cancer: The PALLAS trial results (ABCSG-42/AFT-05/BIG-14-03). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:282-293. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02554 Source

- Pérez-García JM, Cortés J, Ruiz-Borrego M, et al, on behalf of the PHERGain trial investigators. 3-year invasive disease-free survival with chemotherapy de-escalation using an 18F-FDG-PET-based, pathological complete response-adapted strategy in HER2-positive early breast cancer (PHERGain): A randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2024;403:1649-1659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00054-0 Source

- Hylton NM, Gatsonis CA, Rosen MA, et al, for the ACRIN 6657 trial team and I-SPY 1 trial investigators. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: Functional tumor volume by MR imaging predicts recurrence-free survival-results from the ACRIN 6657/CALGB 150007 I-SPY 1 trial. Radiology. 2016;279:44-55. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150013 Source