User login

Migraine Tied to Higher Vascular Dementia Risk

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine had an increased risk for vascular dementia (VaD), with the risk being significantly higher in those with chronic vs episodic migraine.

Major finding: Compared with individuals without migraine, patients with migraine had a 1.21-fold higher risk for VaD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.21; 95% CI 1.17-1.25), with the cumulative incidence of migraine being significantly higher in patients with chronic vs episodic migraine (log-rank P < .001).

Study details: This 10-year retrospective population-based cohort study included 212,836 patients with migraine and 5,863,348 participants without migraine, of whom 3914 (1.8%) and 60,259 (1.0%), respectively, were diagnosed with VaD during the follow-up period.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Research Foundation, Republic of Korea, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Shin H, Ha WS, Kim J, et al. Association between migraine and the risk of vascular dementia: A nationwide longitudinal study in South Korea. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0300379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300379 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine had an increased risk for vascular dementia (VaD), with the risk being significantly higher in those with chronic vs episodic migraine.

Major finding: Compared with individuals without migraine, patients with migraine had a 1.21-fold higher risk for VaD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.21; 95% CI 1.17-1.25), with the cumulative incidence of migraine being significantly higher in patients with chronic vs episodic migraine (log-rank P < .001).

Study details: This 10-year retrospective population-based cohort study included 212,836 patients with migraine and 5,863,348 participants without migraine, of whom 3914 (1.8%) and 60,259 (1.0%), respectively, were diagnosed with VaD during the follow-up period.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Research Foundation, Republic of Korea, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Shin H, Ha WS, Kim J, et al. Association between migraine and the risk of vascular dementia: A nationwide longitudinal study in South Korea. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0300379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300379 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine had an increased risk for vascular dementia (VaD), with the risk being significantly higher in those with chronic vs episodic migraine.

Major finding: Compared with individuals without migraine, patients with migraine had a 1.21-fold higher risk for VaD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.21; 95% CI 1.17-1.25), with the cumulative incidence of migraine being significantly higher in patients with chronic vs episodic migraine (log-rank P < .001).

Study details: This 10-year retrospective population-based cohort study included 212,836 patients with migraine and 5,863,348 participants without migraine, of whom 3914 (1.8%) and 60,259 (1.0%), respectively, were diagnosed with VaD during the follow-up period.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Research Foundation, Republic of Korea, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Shin H, Ha WS, Kim J, et al. Association between migraine and the risk of vascular dementia: A nationwide longitudinal study in South Korea. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0300379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300379 Source

Hypopigmented Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in a Hispanic Infant

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

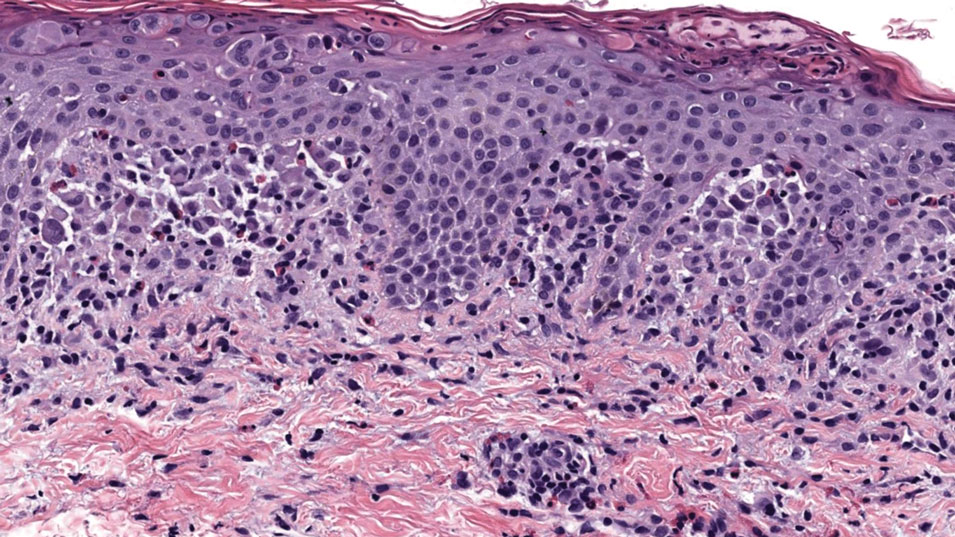

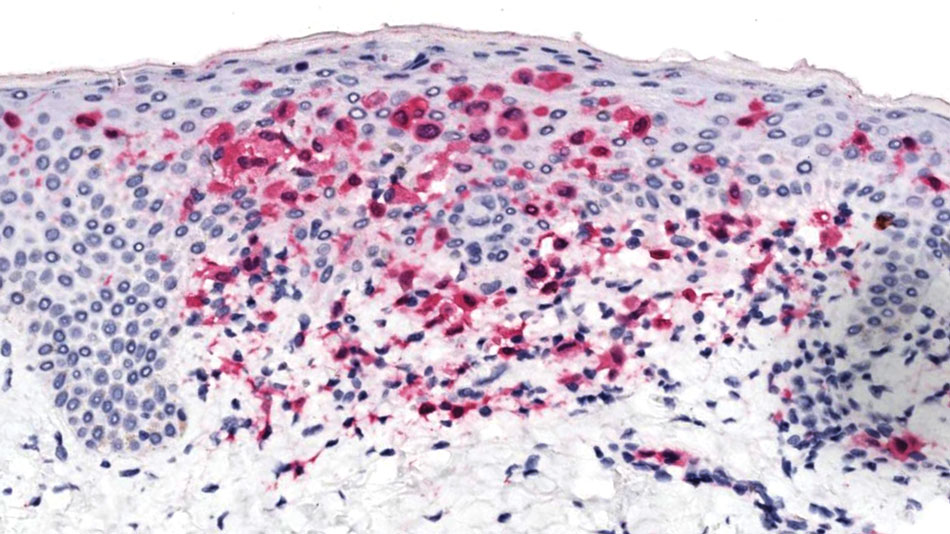

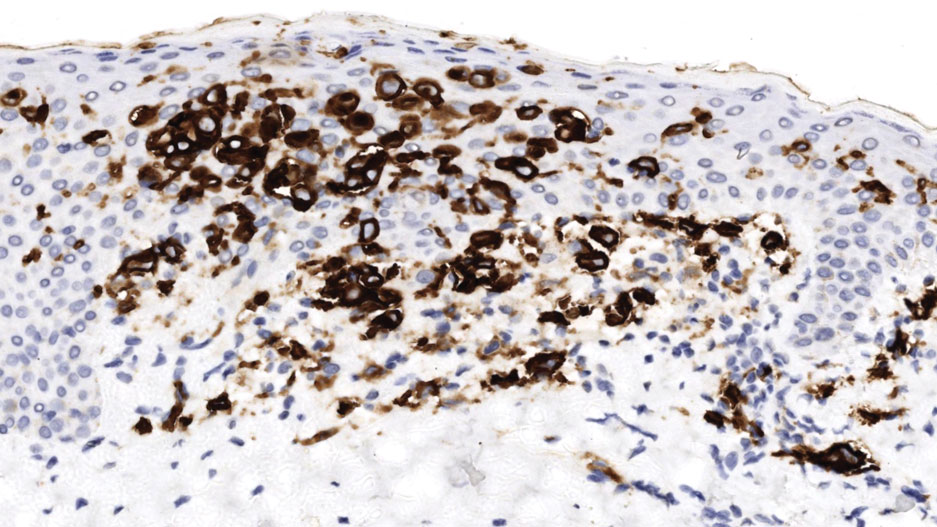

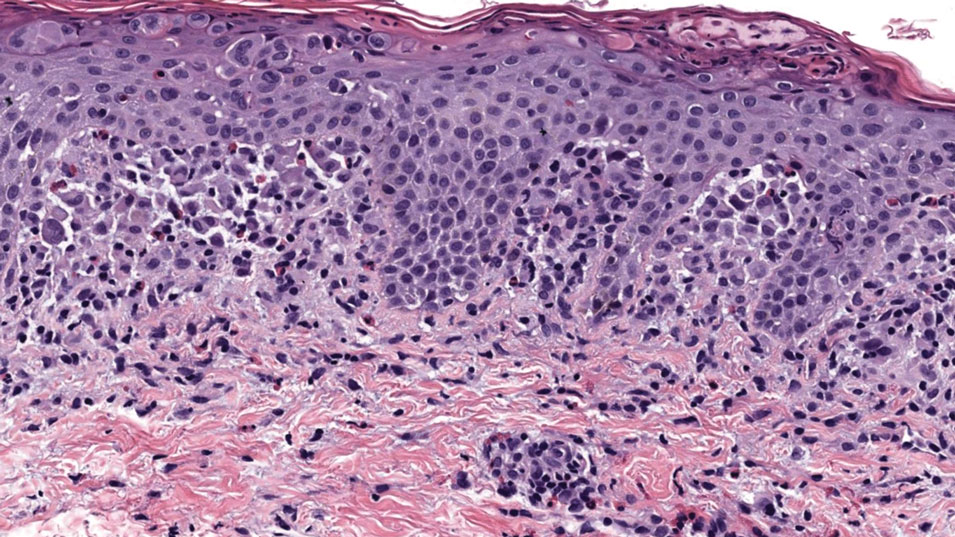

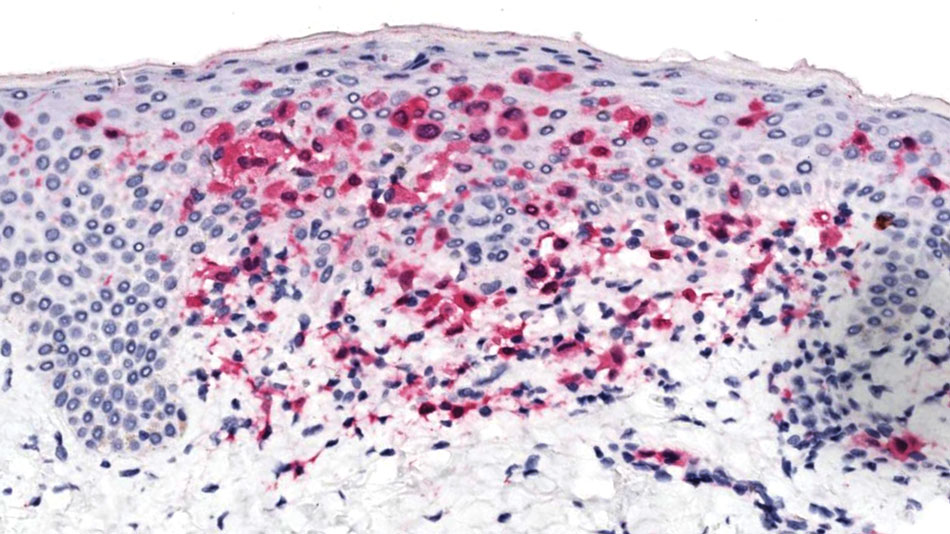

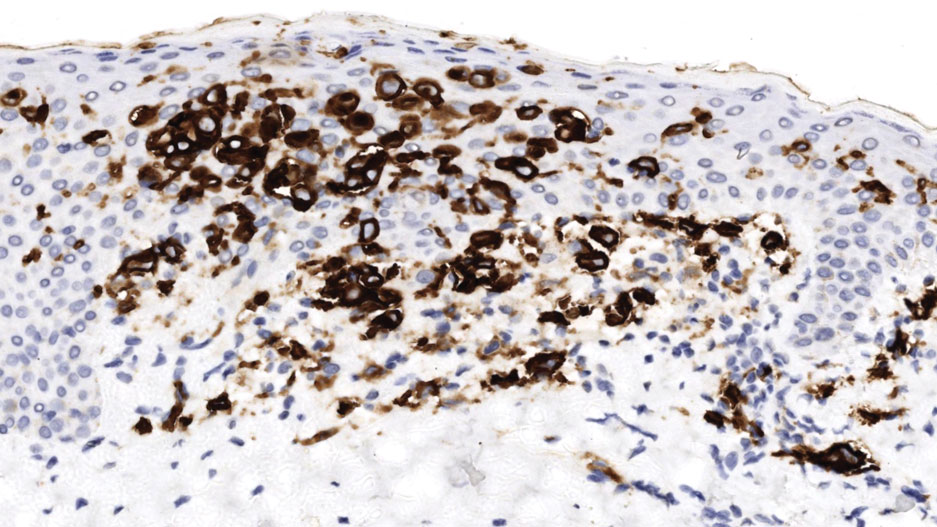

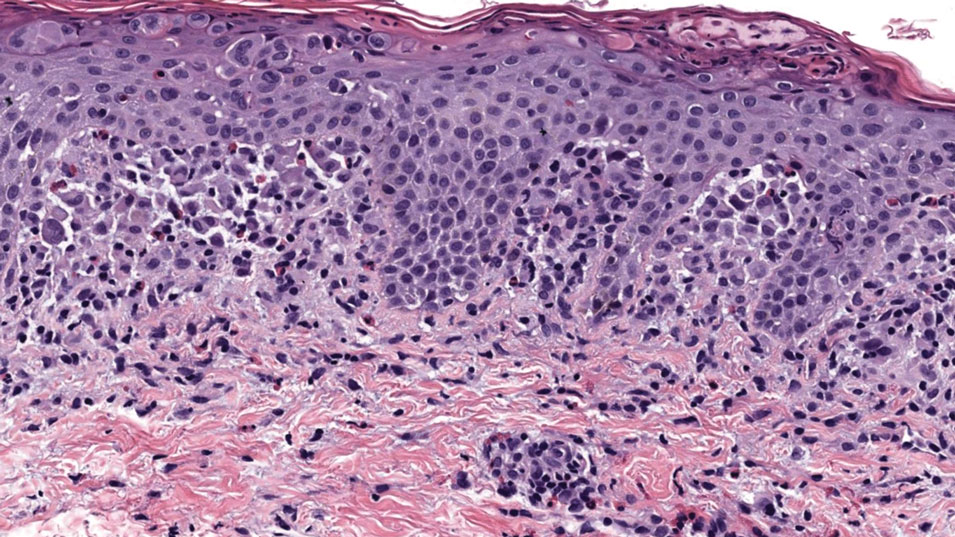

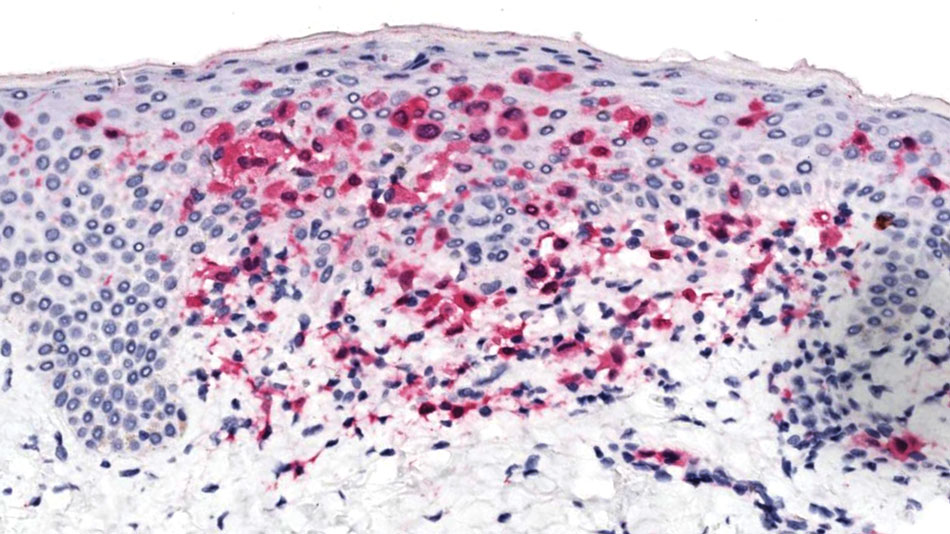

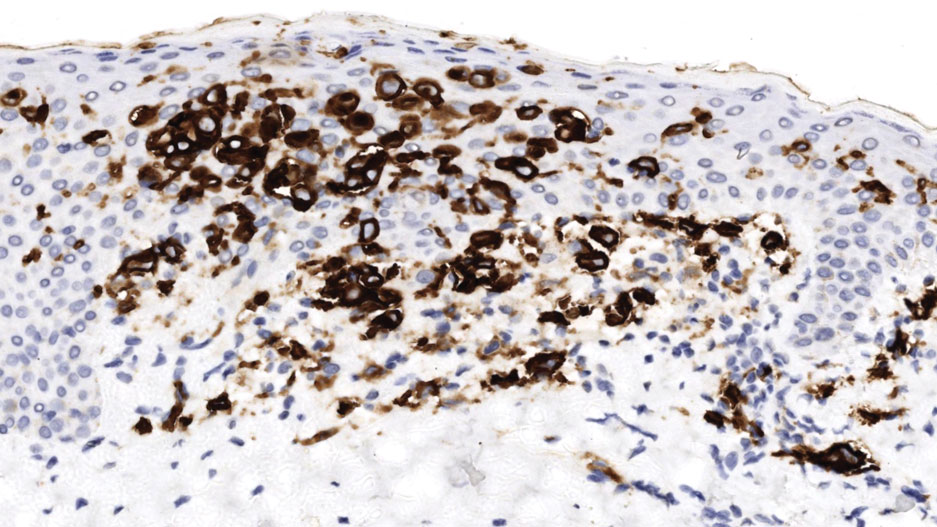

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

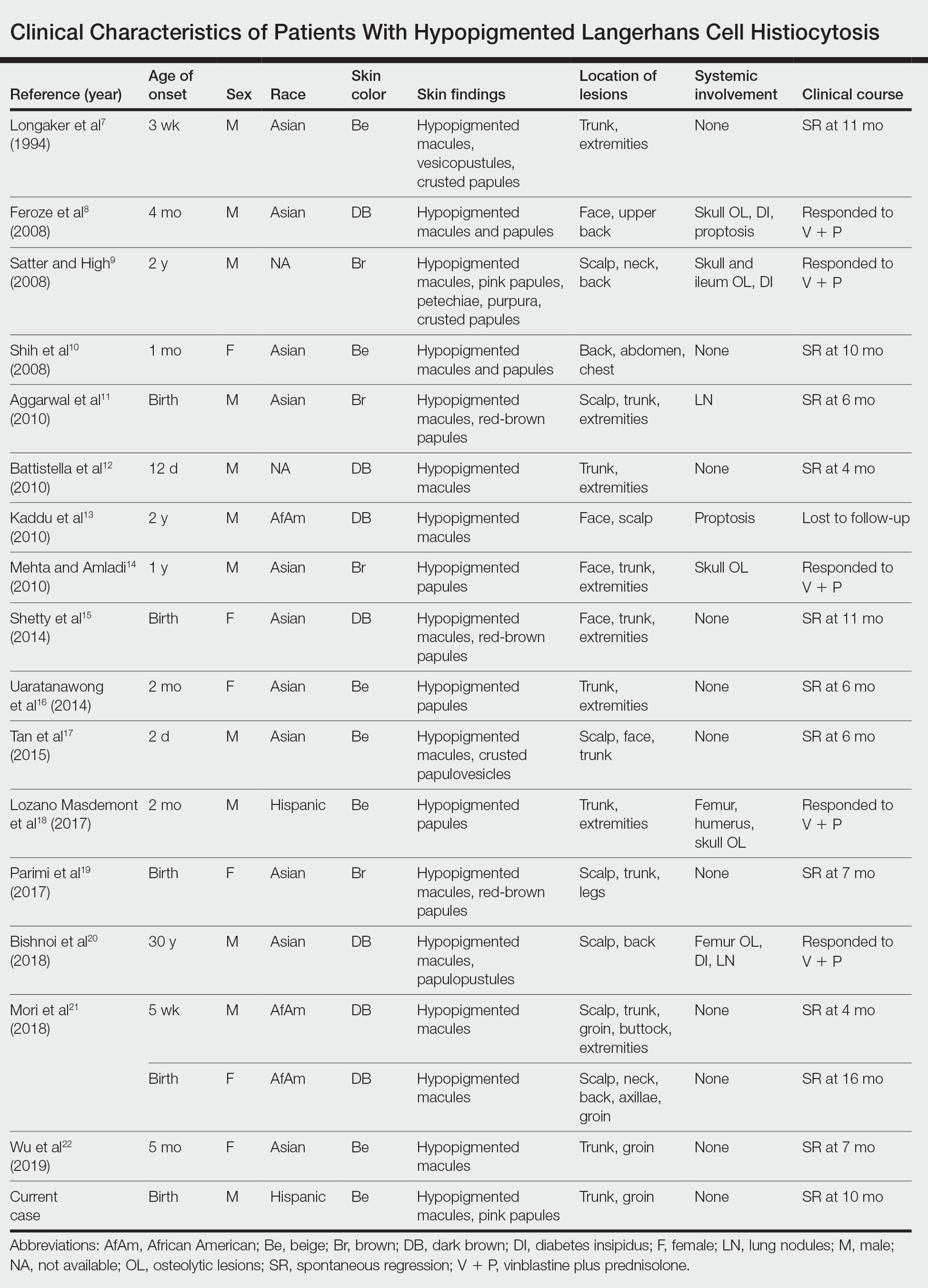

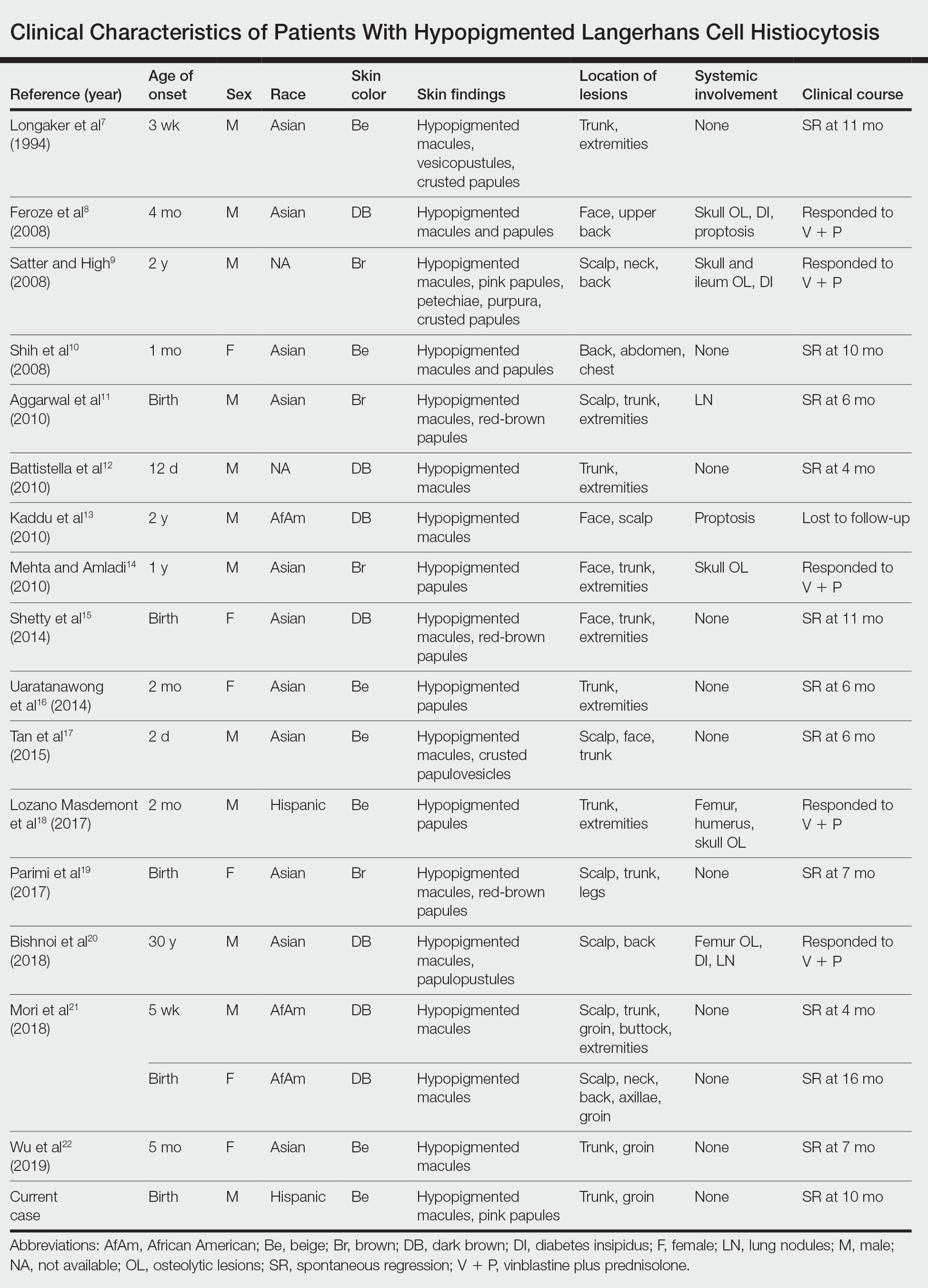

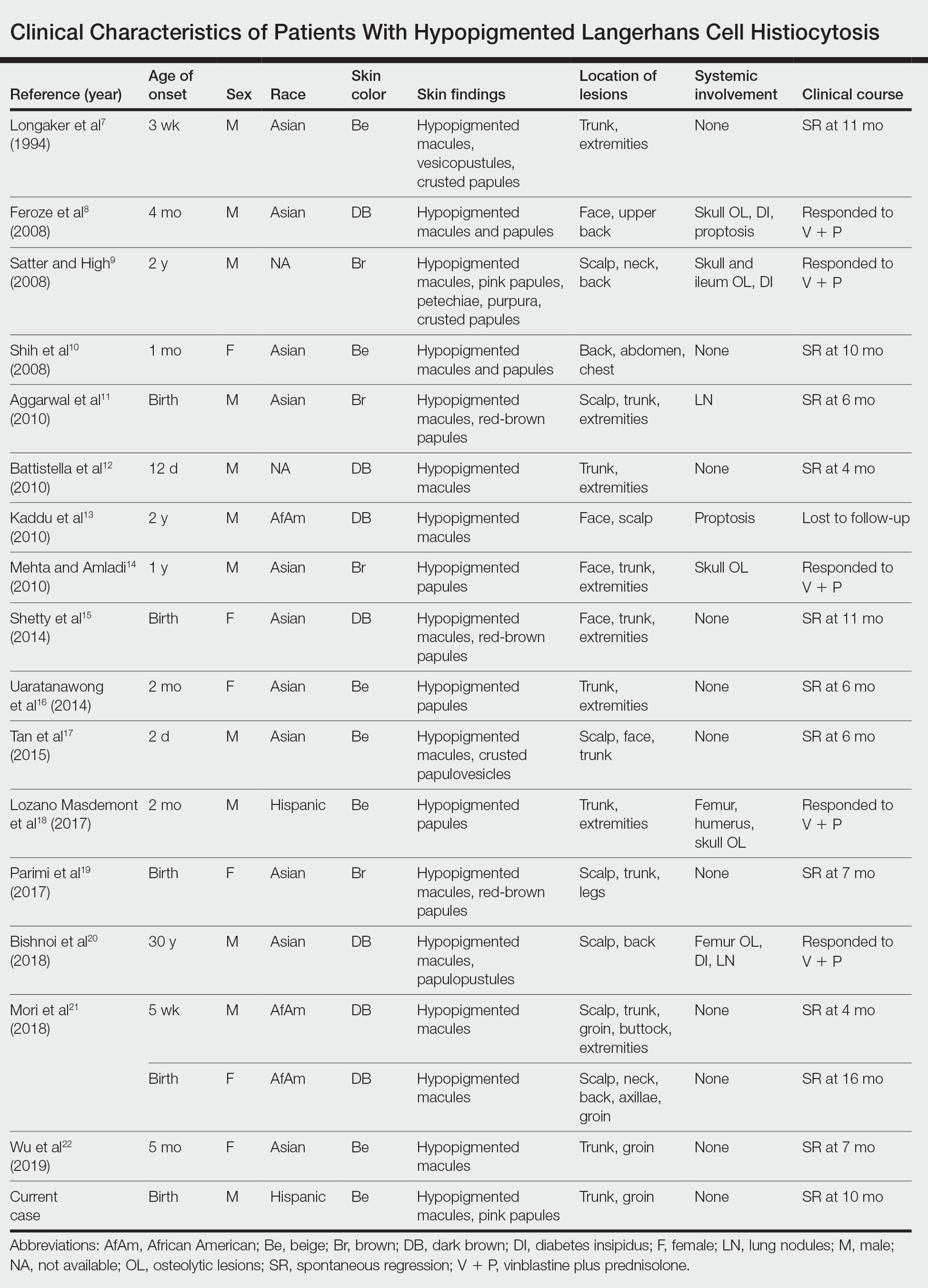

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of the hypopigmented variant of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), which has been reported exclusively in patients with skin of color.

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of hypopigmented macules, which may be the only cutaneous manifestation or may coincide with typical lesions of LCH.

- Hypopigmented cutaneous LCH may be more common in newborns and associated with a better prognosis.

Exploring Skin Pigmentation Adaptation: A Systematic Review on the Vitamin D Adaptation Hypothesis

The risk for developing skin cancer can be somewhat attributed to variations in skin pigmentation. Historically, lighter skin pigmentation has been observed in populations living in higher latitudes and darker pigmentation in populations near the equator. Although skin pigmentation is a conglomeration of genetic and environmental factors, anthropologic studies have demonstrated an association of human skin lightening with historic human migratory patterns.1 It is postulated that migration to latitudes with less UVB light penetration has resulted in a compensatory natural selection of lighter skin types. Furthermore, the driving force behind this migration-associated skin lightening has remained unclear.1

The need for folate metabolism, vitamin D synthesis, and barrier protection, as well as cultural practices, has been postulated as driving factors for skin pigmentation variation. Synthesis of vitamin D is a UV radiation (UVR)–dependent process and has remained a prominent theoretical driver for the basis of evolutionary skin lightening. Vitamin D can be acquired both exogenously or endogenously via dietary supplementation or sunlight; however, historically it has been obtained through UVB exposure primarily. Once UVB is absorbed by the skin, it catalyzes conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which is converted to vitamin D in the kidneys.2,3 It is suggested that lighter skin tones have an advantage over darker skin tones in synthesizing vitamin D at higher latitudes where there is less UVB, thus leading to the adaptation process.1 In this systematic review, we analyzed the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis and assessed the validity of evidence supporting this theory in the literature.

Methods

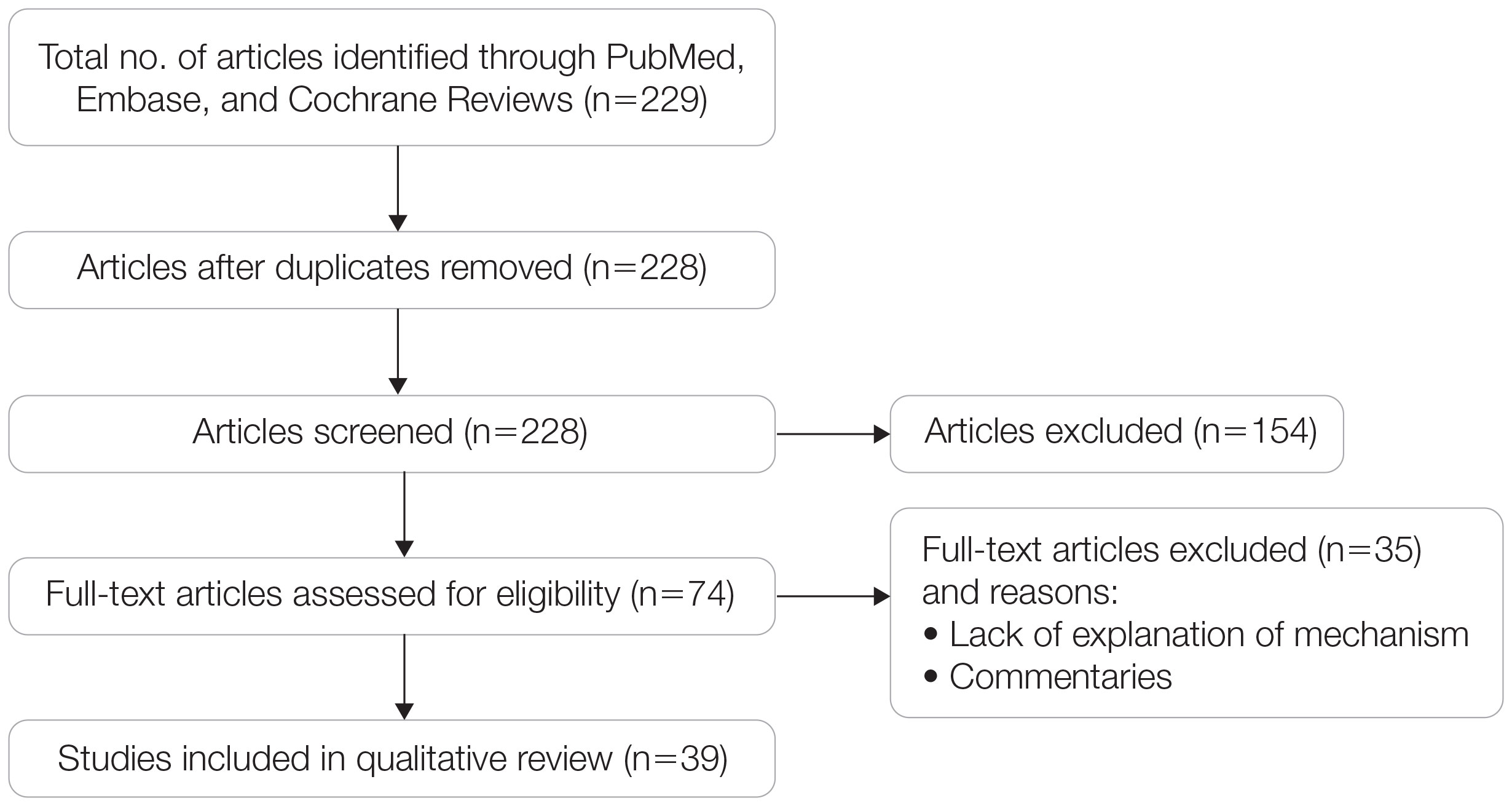

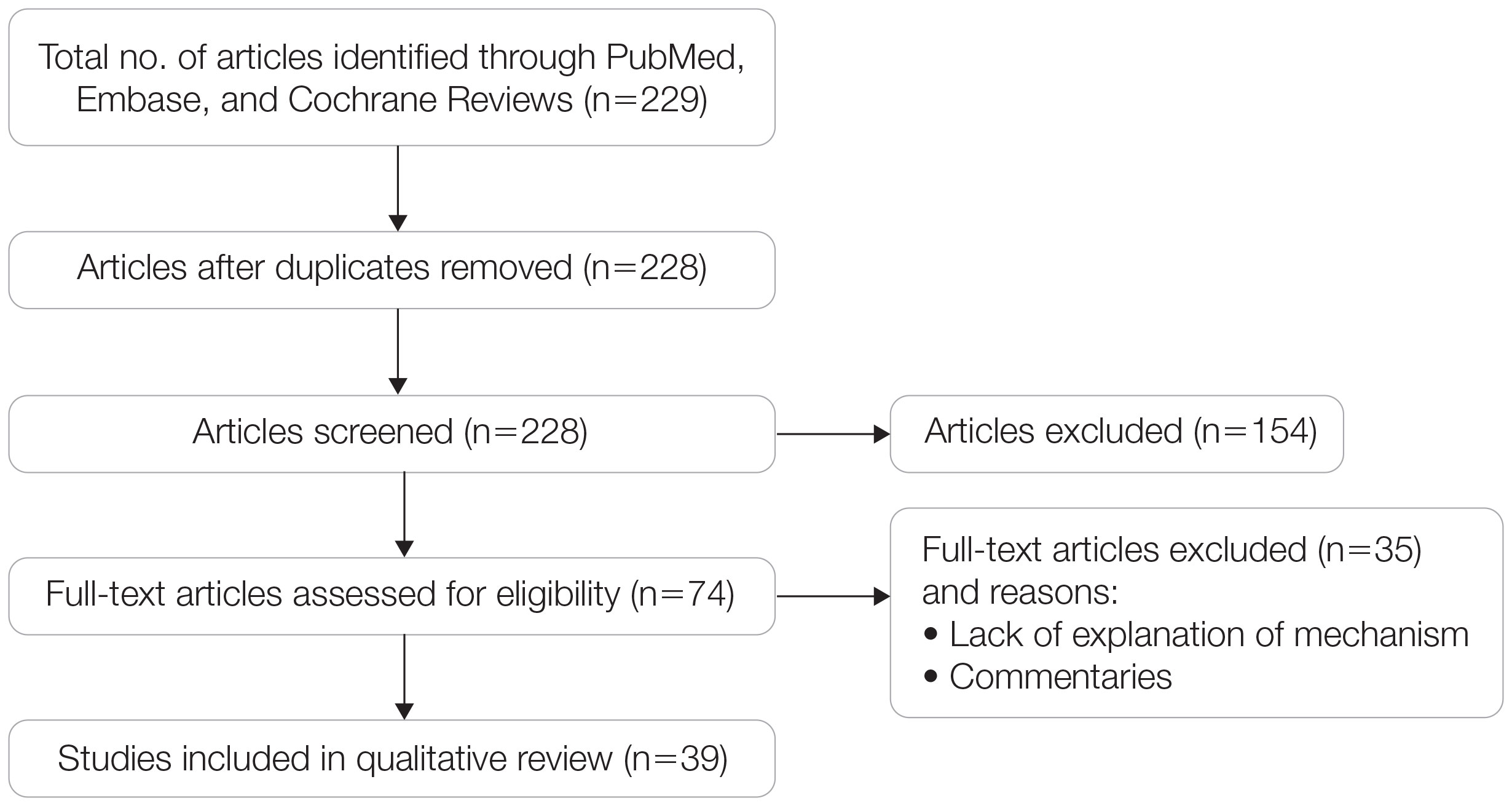

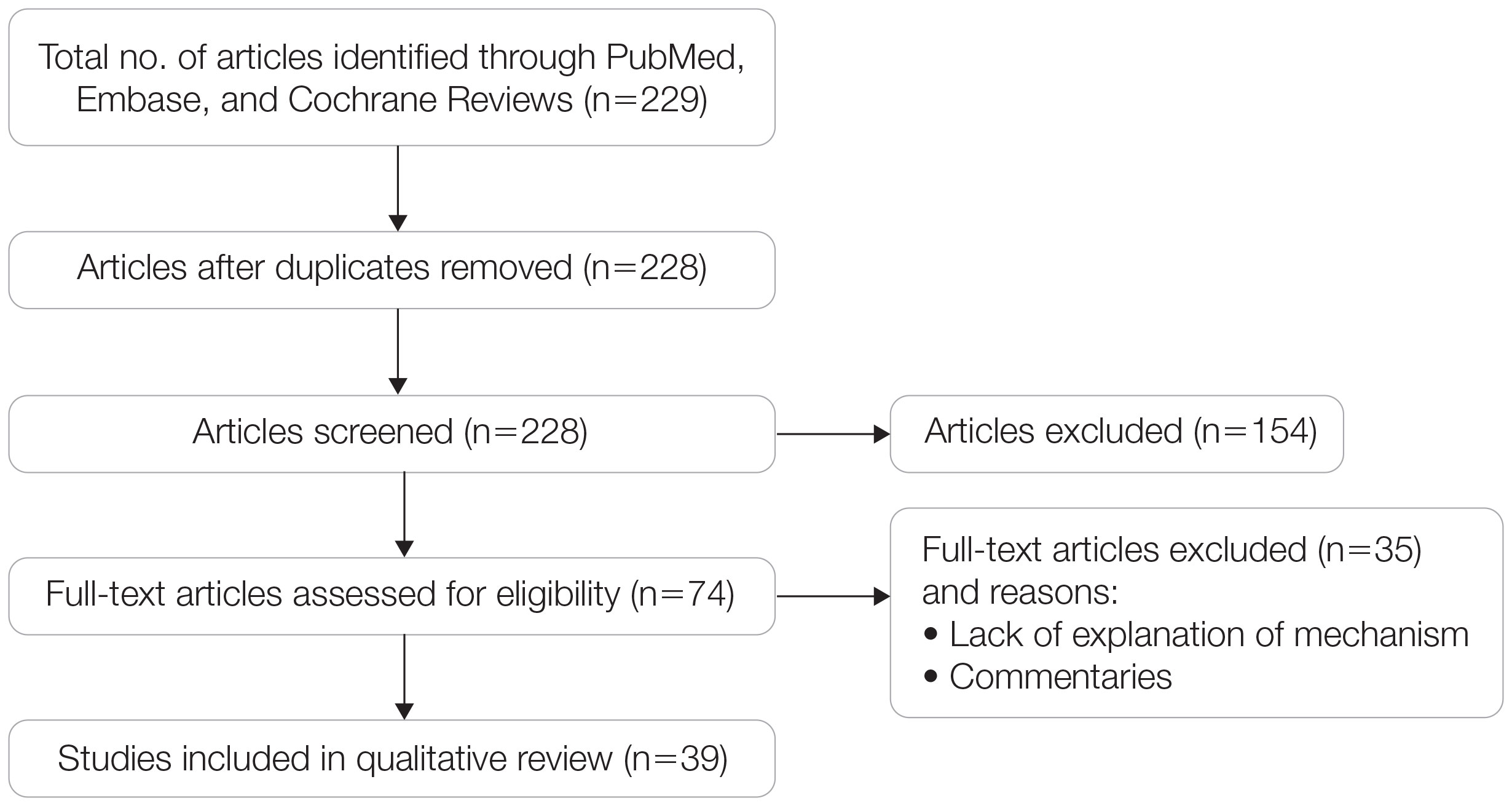

A search of PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Reviews database was conducted using the terms evolution, vitamin D, and skin to generate articles published from 2010 to 2022 that evaluated the influence of UVR-dependent production of vitamin D on skin pigmentation through historical migration patterns (Figure). Studies were excluded during an initial screening of abstracts followed by full-text assessment if they only had abstracts and if articles were inaccessible for review or in the form of case reports and commentaries.

The following data were extracted from each included study: reference citation, affiliated institutions of authors, author specialties, journal name, year of publication, study period, type of article, type of study, mechanism of adaptation, data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver, and data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver. Data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver were recorded from statistically significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotations. Data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver also were recorded from significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotes. The mechanism of adaptation was based on vitamin D synthesis modulation, melanin upregulation, genetic selections, genetic drift, mating patterns, increased vitamin D sensitivity, interbreeding, and diet.

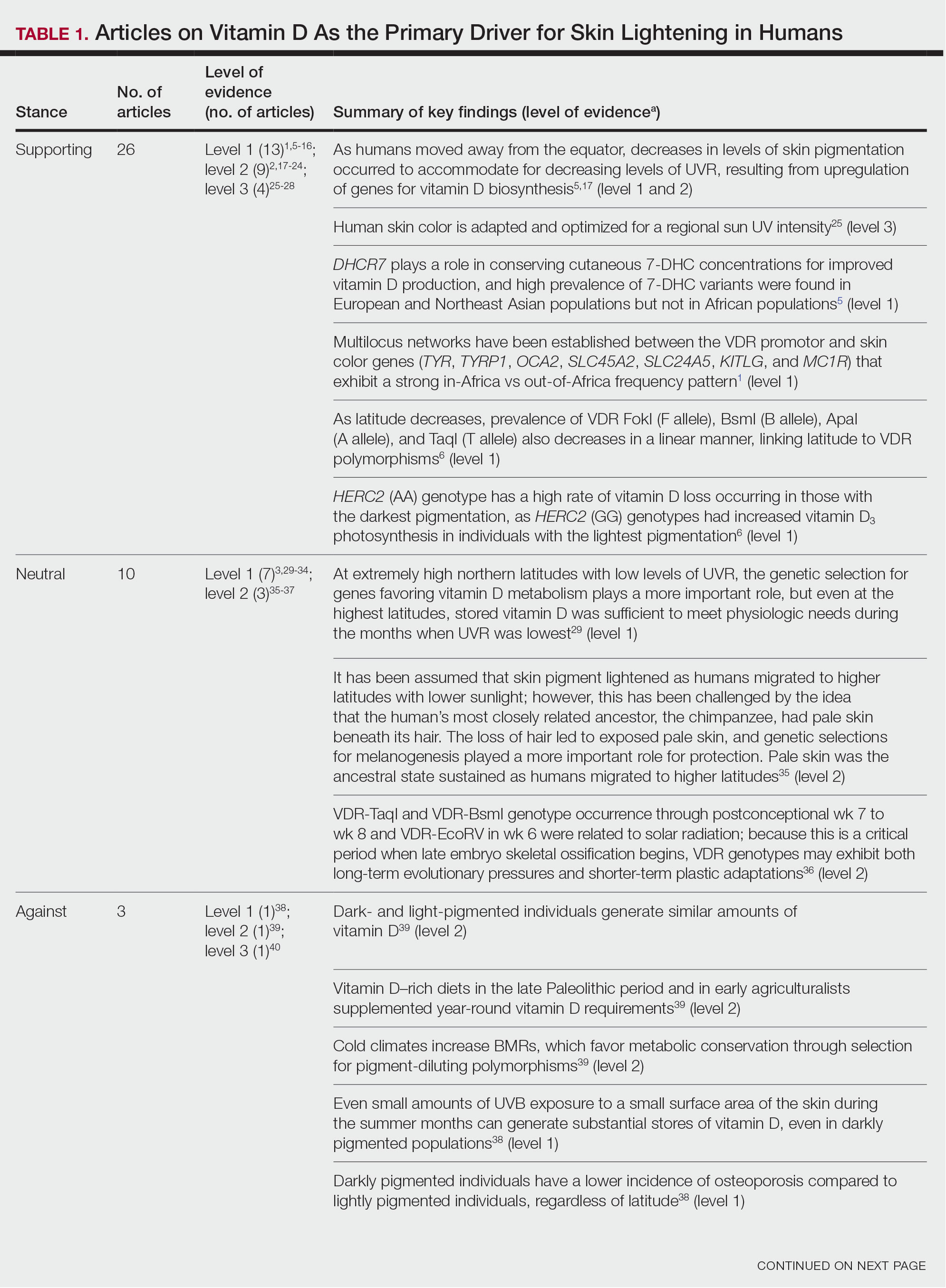

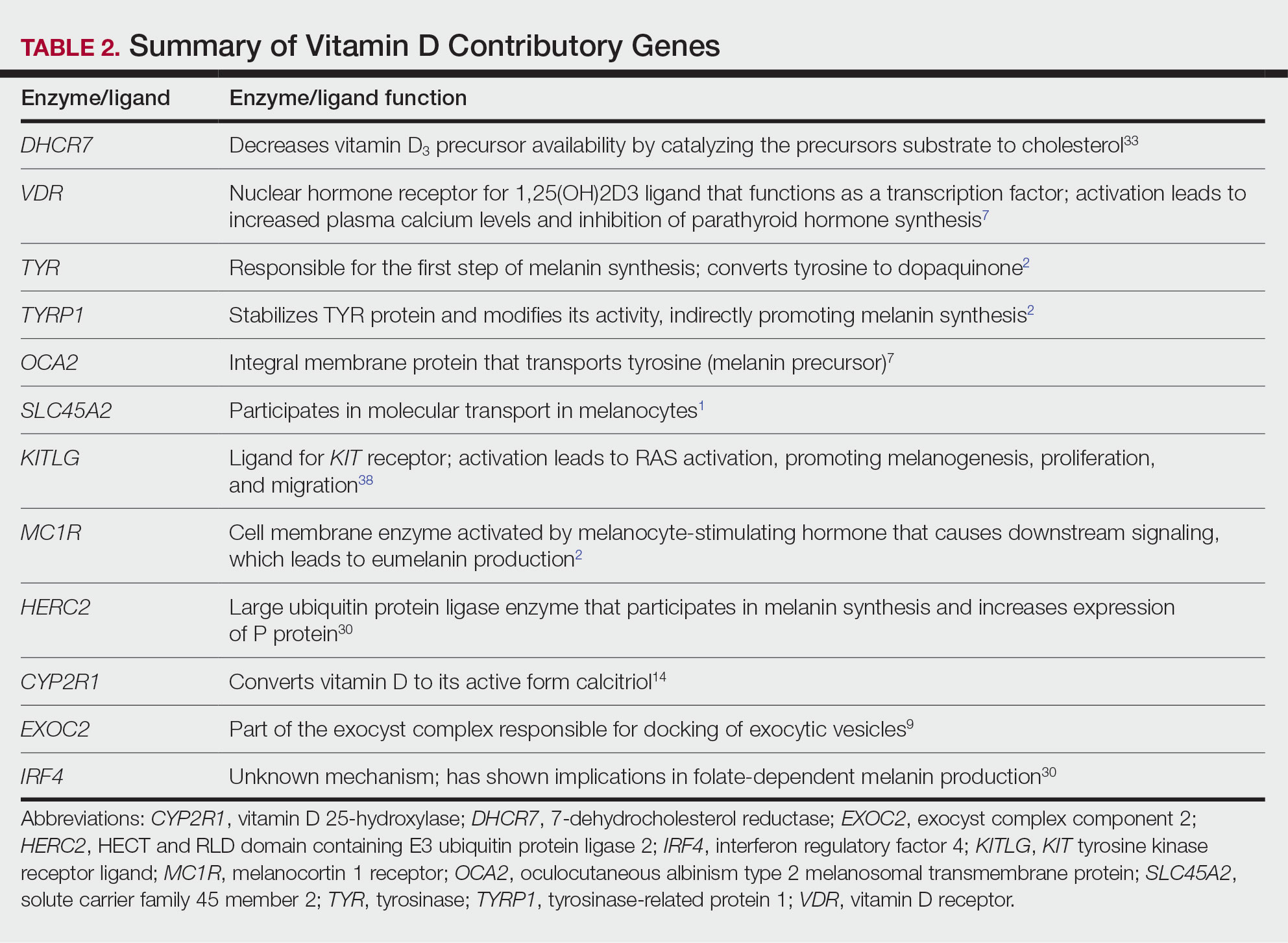

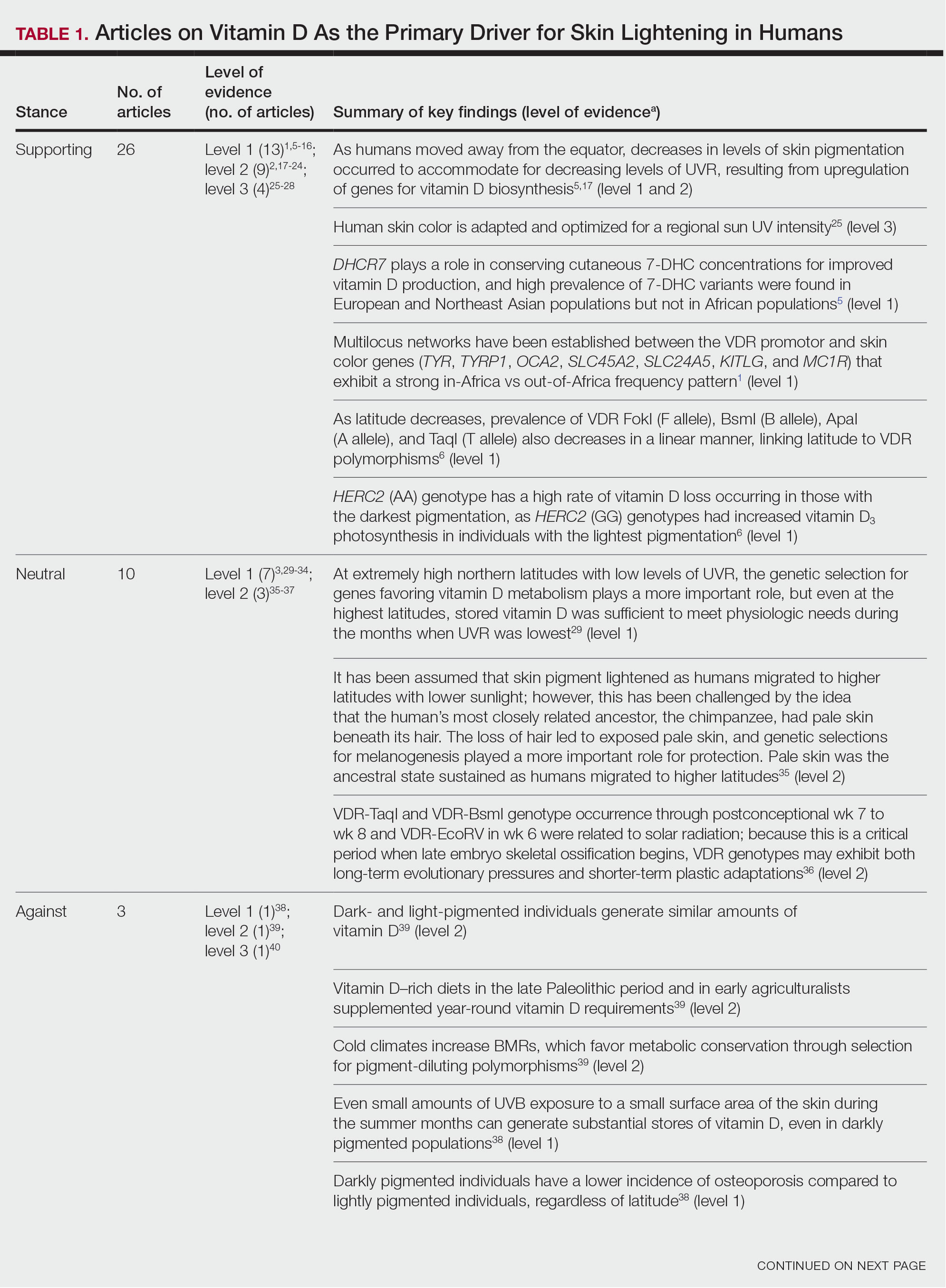

Studies included in the analysis were placed into 1 of 3 categories: supporting, neutral, and against. Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) criteria were used to classify the level of evidence of each article.4 Each article’s level of evidence was then graded (Table 1). The SORT grading levels were based on quality and evidence type: level 1 signified good-quality, patient-oriented evidence; level 2 signified limited-quality, patient-oriented evidence; and level 3 signified other evidence.4

Results

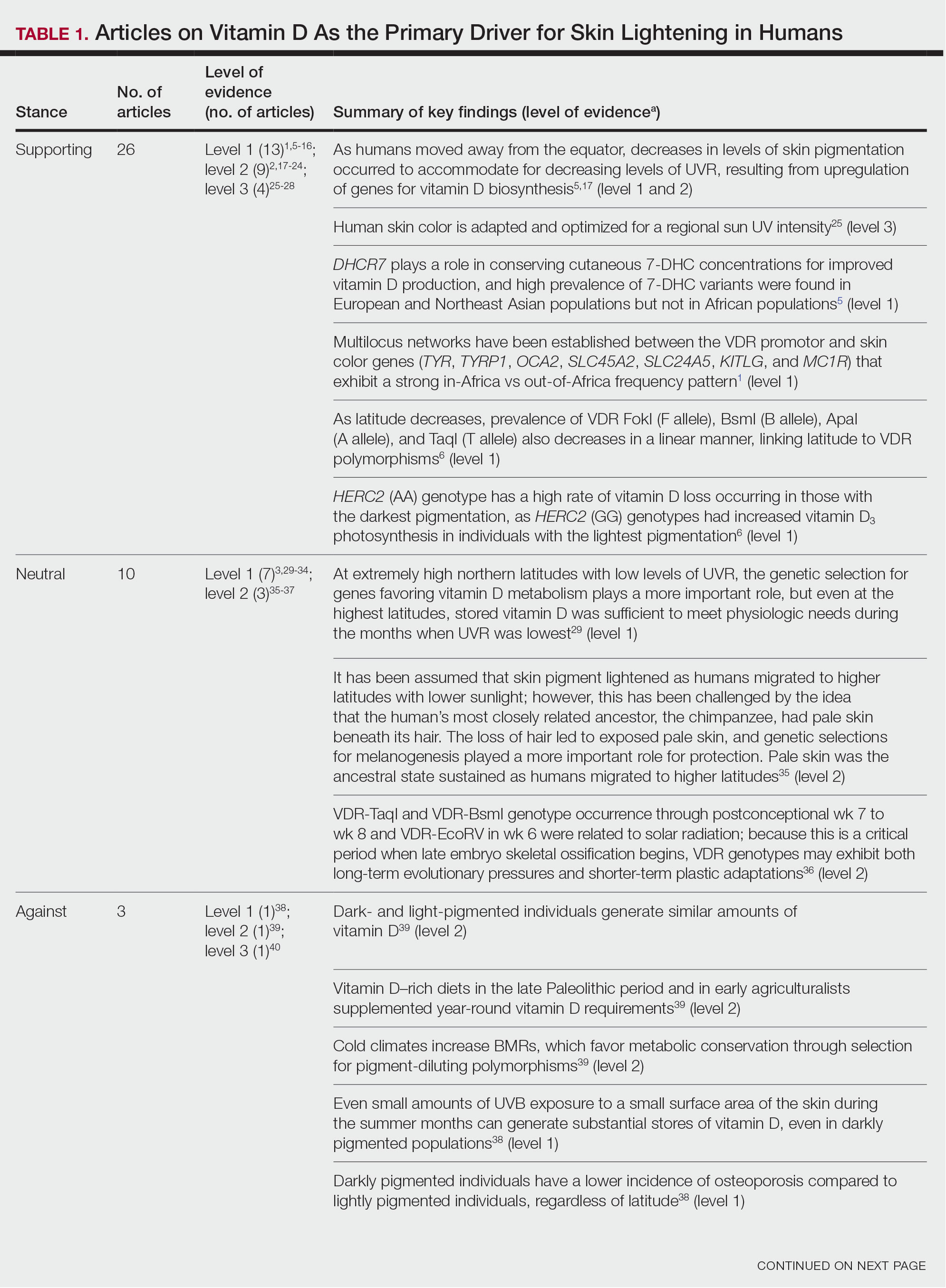

Article Selection—A total of 229 articles were identified for screening, and 39 studies met inclusion criteria.1-3,5-40 Systematic and retrospective reviews were the most common types of studies. Genomic analysis/sequencing/genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were the most common methods of analysis. Of these 39 articles, 26 were classified as supporting the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis, 10 were classified as neutral, and 3 were classified as against (Table 1).

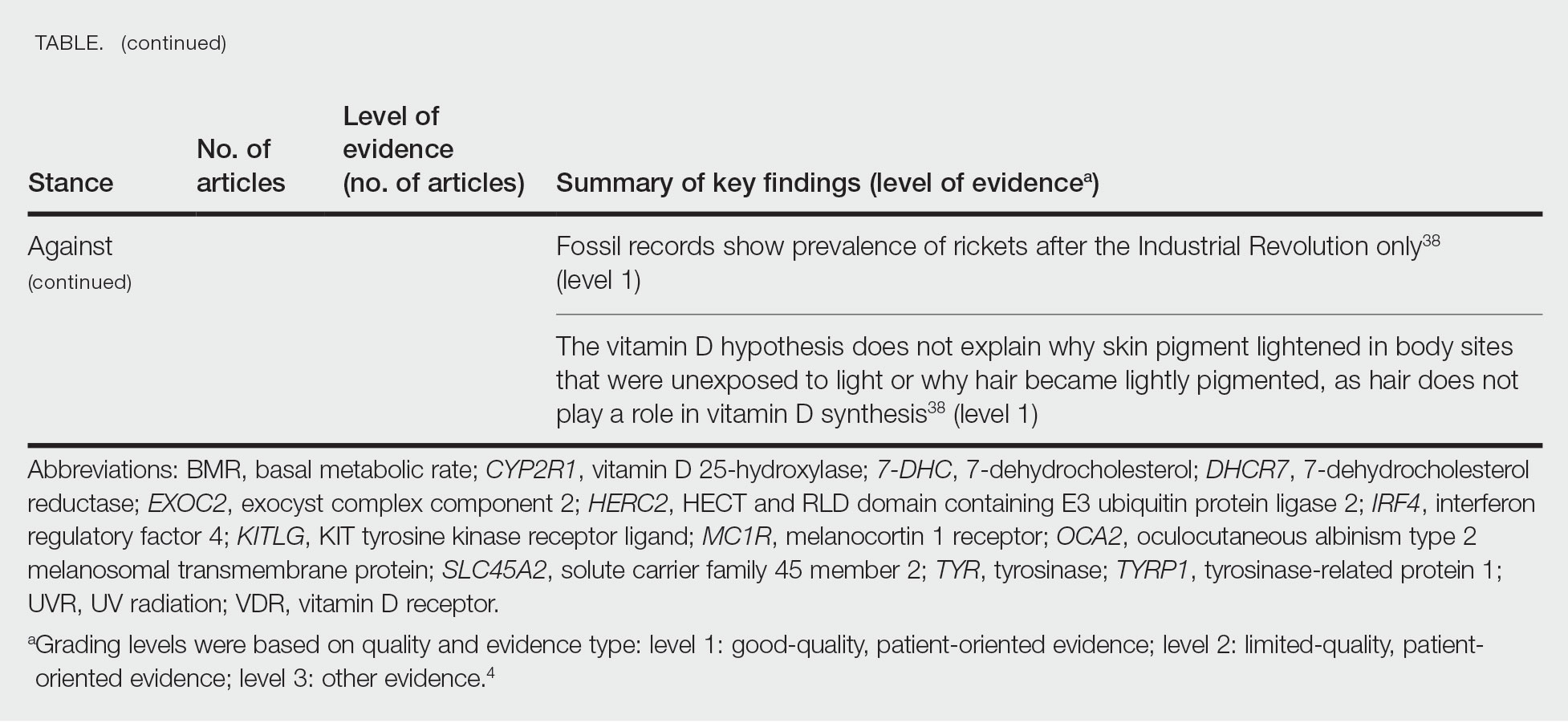

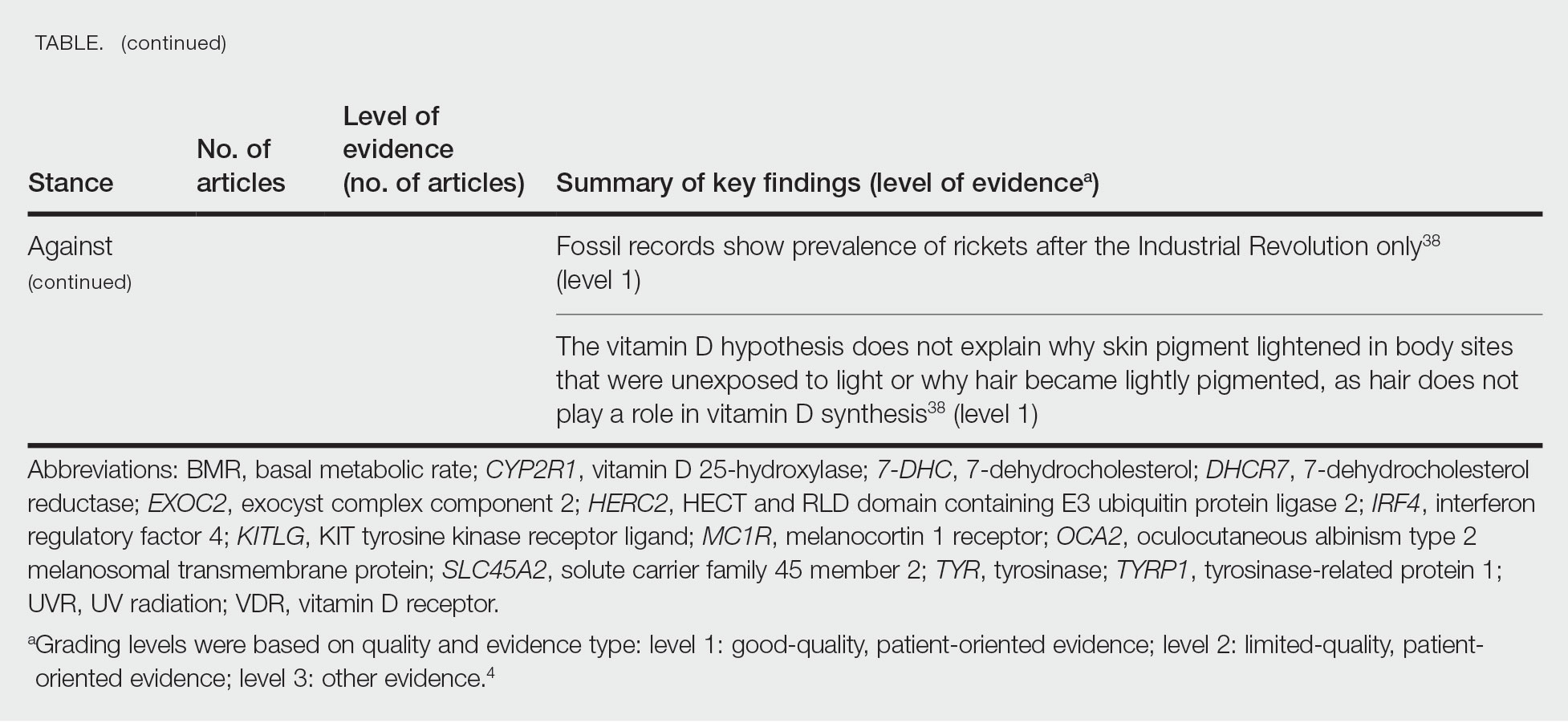

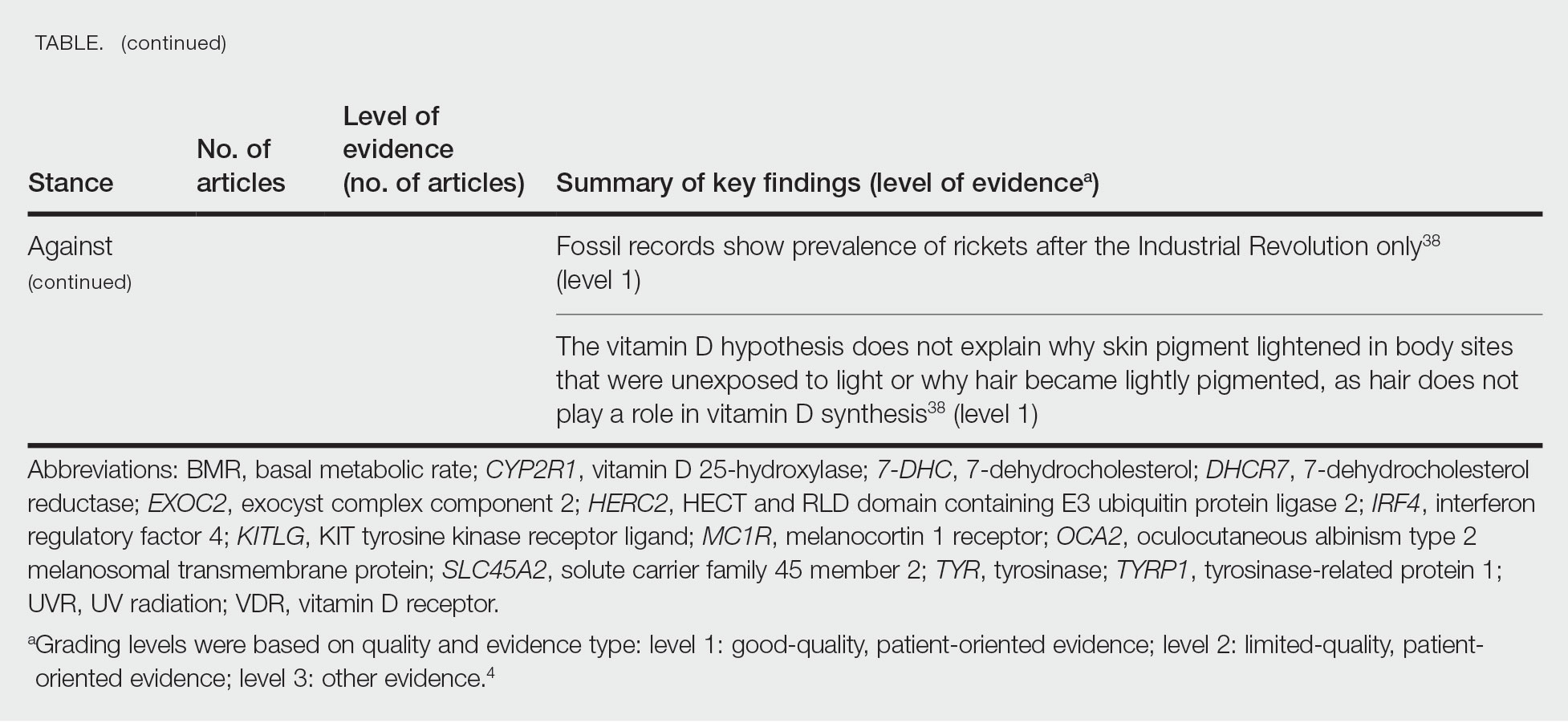

Of the articles classified as supporting the vitamin D hypothesis, 13 articles were level 1 evidence, 9 were level 2, and 4 were level 3. Key findings supporting the vitamin D hypothesis included genetic natural selection favoring vitamin D synthesis genes at higher latitudes with lower UVR and the skin lightening that occurred to protect against vitamin D deficiency (Table 1). Specific genes supporting these findings included 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7), vitamin D receptor (VDR), tyrosinase (TYR), tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1), oculocutaneous albinism type 2 melanosomal transmembrane protein (OCA2), solute carrier family 45 member 2 (SLC45A2), solute carrier family 4 member 5 (SLC24A5), Kit ligand (KITLG), melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), and HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 (HERC2)(Table 2).

Of the articles classified as being against the vitamin D hypothesis, 1 article was level 1 evidence, 1 was level 2, and 1 was level 3. Key findings refuting the vitamin D hypothesis included similar amounts of vitamin D synthesis in contemporary dark- and light-pigmented individuals, vitamin D–rich diets in the late Paleolithic period and in early agriculturalists, and metabolic conservation being the primary driver (Table 1).

Of the articles classified as neutral to the hypothesis, 7 articles were level 1 evidence and 3 were level 2. Key findings of these articles included genetic selection favoring vitamin D synthesis only for populations at extremely northern latitudes, skin lightening that was sustained in northern latitudes from the neighboring human ancestor the chimpanzee, and evidence for long-term evolutionary pressures and short-term plastic adaptations in vitamin D genes (Table 1).

Comment

The importance of appropriate vitamin D levels is hypothesized as a potent driver in skin lightening because the vitamin is essential for many biochemical processes within the human body. Proper calcification of bones requires activated vitamin D to prevent rickets in childhood. Pelvic deformation in women with rickets can obstruct childbirth in primitive medical environments.15 This direct reproductive impairment suggests a strong selective pressure for skin lightening in populations that migrated northward to enhance vitamin D synthesis.

Of the 39 articles that we reviewed, the majority (n=26 [66.7%]) supported the hypothesis that vitamin D synthesis was the main driver behind skin lightening, whereas 3 (7.7%) did not support the hypothesis and 10 (25.6%) were neutral. Other leading theories explaining skin lightening included the idea that enhanced melanogenesis protected against folate degradation; genetic selection for light-skin alleles due to genetic drift; skin lightening being the result of sexual selection; and a combination of factors, including dietary choices, clothing preferences, and skin permeability barriers.

Articles With Supporting Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—As Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa, migration patterns demonstrated the correlation between distance from the equator and skin pigmentation from natural selection. Individuals with darker skin pigment required higher levels of UVR to synthesize vitamin D. According to Beleza et al,1 as humans migrated to areas of higher latitudes with lower levels of UVR, natural selection favored the development of lighter skin to maximize vitamin D production. Vitamin D is linked to calcium metabolism, and its deficiency can lead to bone malformations and poor immune function.35 Several genes affecting melanogenesis and skin pigment have been found to have geospatial patterns that map to different geographic locations of various populations, indicating how human migration patterns out of Africa created this natural selection for skin lightening. The gene KITLG—associated with lighter skin pigmentation—has been found in high frequencies in both European and East Asian populations and is proposed to have increased in frequency after the migration out of Africa. However, the genes TYRP1, SLC24A5, and SLC45A2 were found at high frequencies only in European populations, and this selection occurred 11,000 to 19,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum (15,000–20,000 years ago), demonstrating the selection for European over East Asian characteristics. During this period, seasonal changes increased the risk for vitamin D deficiency and provided an urgency for selection to a lighter skin pigment.1

The migration of H sapiens to northern latitudes prompted the selection of alleles that would increasevitamin D synthesis to counteract the reduced UV exposure. Genetic analysis studies have found key associations between genes encoding for the metabolism of vitamin D and pigmentation. Among this complex network are the essential downstream enzymes in the melanocortin receptor 1 pathway, including TYR and TYRP1. Forty-six of 960 single-nucleotide polymorphisms located in 29 different genes involved in skin pigmentation that were analyzed in a cohort of 2970 individuals were significantly associated with serum vitamin D levels (P<.05). The exocyst complex component 2 (EXOC2), TYR, and TYRP1 gene variants were shown to have the greatest influence on vitamin D status.9 These data reveal how pigment genotypes are predictive of vitamin D levels and the epistatic potential among many genes in this complex network.

Gene variation plays an important role in vitamin D status when comparing genetic polymorphisms in populations in northern latitudes to African populations. Vitamin D3 precursor availability is decreased by 7-DHCR catalyzing the precursors substrate to cholesterol. In a study using GWAS, it was found that “variations in DHCR7 may aid vitamin D production by conserving cutaneous 7-DHC levels. A high prevalence of DHCR7 variants were found in European and Northeast Asian populations but not in African populations, suggesting that selection occurred for these DHCR7 mutations in populations who migrated to more northern latitudes.5 Multilocus networks have been established between the VDR promotor and skin color genes (Table 2) that exhibit a strong in-Africa vs out-of-Africa frequency pattern. It also has been shown that genetic variation (suggesting a long-term evolutionary inclination) and epigenetic modification (indicative of short-term exposure) of VDR lends support to the vitamin D hypothesis. As latitude decreases, prevalence of VDR FokI (F allele), BsmI (B allele), ApaI (A allele), and TaqI (T allele) also decreases in a linear manner, linking latitude to VDR polymorphisms. Plasma vitamin D levels and photoperiod of conception—UV exposure during the periconceptional period—also were extrapolative of VDR methylation in a study involving 80 participants, where these 2 factors accounted for 17% of variance in methylation.6

Other noteworthy genes included HERC2, which has implications in the expression of OCA2 (melanocyte-specific transporter protein), and IRF4, which encodes for an important enzyme in folate-dependent melanin production. In an Australian cross-sectional study that analyzed vitamin D and pigmentation gene polymorphisms in conjunction with plasma vitamin D levels, the most notable rate of vitamin D loss occurred in individuals with the darkest pigmentation HERC2 (AA) genotype.31 In contrast, the lightest pigmentation HERC2 (GG) genotypes had increased vitamin D3 photosynthesis. Interestingly, the lightest interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) TT genotype and the darkest HERC2 AA genotype, rendering the greatest folate loss and largest synthesis of vitamin D3, were not seen in combination in any of the participants.30 In addition to HERC2, derived alleles from pigment-associated genes SLC24A5*A and SLC45A2*G demonstrated greater frequencies in Europeans (>90%) compared to Africans and East Asians, where the allelic frequencies were either rare or absent.1 This evidence delineates not only the complexity but also the strong relationship between skin pigmentation, latitude, and vitamin D status. The GWAS also have supported this concept. In comparing European populations to African populations, there was a 4-fold increase in the frequencies of “derived alleles of the vitamin D transport protein (GC, rs3755967), the 25(OH)D3 synthesizing enzyme (CYP2R1, rs10741657), VDR (rs2228570 (commonly known as FokI polymorphism), rs1544410 (Bsm1), and rs731236 (Taq1) and the VDR target genes CYP24A1 (rs17216707), CD14 (rs2569190), and CARD9 (rs4077515).”32

Articles With Evidence Against the Vitamin D Theory—This review analyzed the level of support for the theory that vitamin D was the main driver for skin lightening. Although most articles supported this theory, there were articles that listed other plausible counterarguments. Jablonski and Chaplin3 suggested that humans living in higher latitudes compensated for increased demand of vitamin D by placing cultural importance on a diet of vitamin D–rich foods and thus would not have experienced decreased vitamin D levels, which we hypothesize were the driver for skin lightening. Elias et al39 argued that initial pigment dilution may have instead served to improve metabolic conservation, as the authors found no evidence of rickets—the sequelae of vitamin D deficiency—in pre–industrial age human fossils. Elias and Williams38 proposed that differences in skin pigment are due to a more intact skin permeability barrier as “a requirement for life in a desiccating terrestrial environment,” which is seen in darker skin tones compared to lighter skin tones and thus can survive better in warmer climates with less risk of infections or dehydration.

Articles With Neutral Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—Greaves41 argued against the idea that skin evolved to become lighter to protect against vitamin D deficiency. They proposed that the chimpanzee, which is the human’s most closely related species, had light skin covered by hair, and the loss of this hair led to exposed pale skin that created a need for increased melanin production for protection from UVR. Greaves41 stated that the MC1R gene (associated with darker pigmentation) was selected for in African populations, and those with pale skin retained their original pigment as they migrated to higher latitudes. Further research has demonstrated that the genetic natural selection for skin pigment is a complex process that involves multiple gene variants found throughout cultures across the globe.

Conclusion

Skin pigmentation has continuously evolved alongside humans. Genetic selection for lighter skin coincides with a favorable selection for genes involved in vitamin D synthesis as humans migrated to northern latitudes, which enabled humans to produce adequate levels of exogenous vitamin D in low-UVR areas and in turn promoted survival. Early humans without access to supplementation or foods rich in vitamin D acquired vitamin D primarily through sunlight. In comparison to modern society, where vitamin D supplementation is accessible and human lifespans are prolonged, lighter skin tone is now a risk factor for malignant cancers of the skin rather than being a protective adaptation. Current sun behavior recommendations conclude that the body’s need for vitamin D is satisfied by UV exposure to the arms, legs, hands, and/or face for only 5 to 30 minutes between 10

The hypothesis that skin lightening primarily was driven by the need for vitamin D can only be partially supported by our review. Studies have shown that there is a corresponding complex network of genes that determines skin pigmentation as well as vitamin D synthesis and conservation. However, there is sufficient evidence that skin lightening is multifactorial in nature, and vitamin D alone may not be the sole driver. The information in this review can be used by health care providers to educate patients on sun protection, given the lesser threat of severe vitamin D deficiency in developed communities today that have access to adequate nutrition and supplementation.

Skin lightening and its coinciding evolutionary drivers are a rather neglected area of research. Due to heterogeneous cohorts and conservative data analysis, GWAS studies run the risk of type II error, yielding a limitation in our data analysis.9 Furthermore, the data regarding specific time frames in evolutionary skin lightening as well as the intensity of gene polymorphisms are limited.1 Further studies are needed to determine the interconnectedness of the current skin-lightening theories to identify other important factors that may play a role in the process. Determining the key event can help us better understand skin-adaptation mechanisms and create a framework for understanding the vital process involved in adaptation, survival, and disease manifestation in different patient populations.

- Beleza S, Santos AM, McEvoy B, et al. The timing of pigmentation lightening in Europeans. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:24-35. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207

- Carlberg C. Nutrigenomics of vitamin D. Nutrients. 2019;11:676. doi:10.3390/nu11030676

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. The roles of vitamin D and cutaneous vitamin D production in human evolution and health. Int J Paleopathol. 2018;23:54-59. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2018.01.005

- Weiss BD. SORT: strength of recommendation taxonomy. Fam Med. 2004;36:141-143.

- Wolf ST, Kenney WL. The vitamin D–folate hypothesis in human vascular health. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiology. 2019;317:R491-R501. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00136.2019

- Lucock M, Jones P, Martin C, et al. Photobiology of vitamins. Nutr Rev. 2018;76:512-525. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuy013

- Hochberg Z, Hochberg I. Evolutionary perspective in rickets and vitamin D. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:306. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00306

- Rossberg W, Saternus R, Wagenpfeil S, et al. Human pigmentation, cutaneous vitamin D synthesis and evolution: variants of genes (SNPs) involved in skin pigmentation are associated with 25(OH)D serum concentration. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:1429-1437.

- Saternus R, Pilz S, Gräber S, et al. A closer look at evolution: variants (SNPs) of genes involved in skin pigmentation, including EXOC2, TYR, TYRP1, and DCT, are associated with 25(OH)D serum concentration. Endocrinology. 2015;156:39-47. doi:10.1210/en.2014-1238

- López S, García Ó, Yurrebaso I, et al. The interplay between natural selection and susceptibility to melanoma on allele 374F of SLC45A2 gene in a south European population. PloS One. 2014;9:E104367. doi:1371/journal.pone.0104367

- Lucock M, Yates Z, Martin C, et al. Vitamin D, folate, and potential early lifecycle environmental origin of significant adult phenotypes. Evol Med Public Health. 2014;2014:69-91. doi:10.1093/emph/eou013

- Hudjashov G, Villems R, Kivisild T. Global patterns of diversity and selection in human tyrosinase gene. PloS One. 2013;8:E74307. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074307

- Khan R, Khan BSR. Diet, disease and pigment variation in humans. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75:363-367. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2010.03.033

- Kuan V, Martineau AR, Griffiths CJ, et al. DHCR7 mutations linked to higher vitamin D status allowed early human migration to northern latitudes. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:144. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-144

- Omenn GS. Evolution and public health. Proc National Acad Sci. 2010;107(suppl 1):1702-1709. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906198106

- Yuen AWC, Jablonski NG. Vitamin D: in the evolution of human skin colour. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74:39-44. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2009.08.007

- Vieth R. Weaker bones and white skin as adaptions to improve anthropological “fitness” for northern environments. Osteoporosis Int. 2020;31:617-624. doi:10.1007/s00198-019-05167-4

- Carlberg C. Vitamin D: a micronutrient regulating genes. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25:1740-1746. doi:10.2174/1381612825666190705193227

- Haddadeen C, Lai C, Cho SY, et al. Variants of the melanocortin‐1 receptor: do they matter clinically? Exp Dermatol. 2015;1:5-9. doi:10.1111/exd.12540

- Yao S, Ambrosone CB. Associations between vitamin D deficiency and risk of aggressive breast cancer in African-American women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;136:337-341. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.09.010

- Jablonski N. The evolution of human skin colouration and its relevance to health in the modern world. J Royal Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;42:58-63. doi:10.4997/jrcpe.2012.114

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc National Acad Sci. 2010;107(suppl 2):8962-8968. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914628107

- Hochberg Z, Templeton AR. Evolutionary perspective in skin color, vitamin D and its receptor. Hormones. 2010;9:307-311. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1281

- Jones P, Lucock M, Veysey M, et al. The vitamin D–folate hypothesis as an evolutionary model for skin pigmentation: an update and integration of current ideas. Nutrients. 2018;10:554. doi:10.3390/nu10050554

- Lindqvist PG, Epstein E, Landin-Olsson M, et al. Women with fair phenotypes seem to confer a survival advantage in a low UV milieu. a nested matched case control study. PloS One. 2020;15:E0228582. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228582

- Holick MF. Shedding new light on the role of the sunshine vitamin D for skin health: the lncRNA–skin cancer connection. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:391-392. doi:10.1111/exd.12386

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Epidermal pigmentation in the human lineage is an adaptation to ultraviolet radiation. J Hum Evol. 2013;65:671-675. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.06.004

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. The evolution of skin pigmentation and hair texture in people of African ancestry. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:113-121. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.11.003

- Jablonski NG. The evolution of human skin pigmentation involved the interactions of genetic, environmental, and cultural variables. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021;34:707-7 doi:10.1111/pcmr.12976

- Lucock MD, Jones PR, Veysey M, et al. Biophysical evidence to support and extend the vitamin D‐folate hypothesis as a paradigm for the evolution of human skin pigmentation. Am J Hum Biol. 2022;34:E23667. doi:10.1002/ajhb.23667

- Missaggia BO, Reales G, Cybis GB, et al. Adaptation and co‐adaptation of skin pigmentation and vitamin D genes in native Americans. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020;184:1060-1077. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31873

- Hanel A, Carlberg C. Skin colour and vitamin D: an update. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:864-875. doi:10.1111/exd.14142

- Hanel A, Carlberg C. Vitamin D and evolution: pharmacologic implications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;173:113595. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2019.07.024

- Flegr J, Sýkorová K, Fiala V, et al. Increased 25(OH)D3 level in redheaded people: could redheadedness be an adaptation to temperate climate? Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:598-609. doi:10.1111/exd.14119

- James WPT, Johnson RJ, Speakman JR, et al. Nutrition and its role in human evolution. J Intern Med. 2019;285:533-549. doi:10.1111/joim.12878

- Lucock M, Jones P, Martin C, et al. Vitamin D: beyond metabolism. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20:310-322. doi:10.1177/2156587215580491

- Jarrett P, Scragg R. Evolution, prehistory and vitamin D. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:646. doi:10.3390/ijerph17020646

- Elias PM, Williams ML. Re-appraisal of current theories for thedevelopment and loss of epidermal pigmentation in hominins and modern humans. J Hum Evol. 2013;64:687-692. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.02.003

- Elias PM, Williams ML. Basis for the gain and subsequent dilution of epidermal pigmentation during human evolution: the barrier and metabolic conservation hypotheses revisited. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2016;161:189-207. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23030

- Williams JD, Jacobson EL, Kim H, et al. Water soluble vitamins, clinical research and future application. Subcell Biochem. 2011;56:181-197. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2199-9_10

- Greaves M. Was skin cancer a selective force for black pigmentation in early hominin evolution [published online February 26, 2014]? Proc Biol Sci. 2014;281:20132955. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2955

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266-281. doi:10.1056/nejmra070553

- Bouillon R. Comparative analysis of nutritional guidelines for vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:466-479. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2017.31

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. US Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2014. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/call-to-action-prevent-skin-cancer.pdf

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al, eds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. National Academies Press; 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56070/

The risk for developing skin cancer can be somewhat attributed to variations in skin pigmentation. Historically, lighter skin pigmentation has been observed in populations living in higher latitudes and darker pigmentation in populations near the equator. Although skin pigmentation is a conglomeration of genetic and environmental factors, anthropologic studies have demonstrated an association of human skin lightening with historic human migratory patterns.1 It is postulated that migration to latitudes with less UVB light penetration has resulted in a compensatory natural selection of lighter skin types. Furthermore, the driving force behind this migration-associated skin lightening has remained unclear.1

The need for folate metabolism, vitamin D synthesis, and barrier protection, as well as cultural practices, has been postulated as driving factors for skin pigmentation variation. Synthesis of vitamin D is a UV radiation (UVR)–dependent process and has remained a prominent theoretical driver for the basis of evolutionary skin lightening. Vitamin D can be acquired both exogenously or endogenously via dietary supplementation or sunlight; however, historically it has been obtained through UVB exposure primarily. Once UVB is absorbed by the skin, it catalyzes conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which is converted to vitamin D in the kidneys.2,3 It is suggested that lighter skin tones have an advantage over darker skin tones in synthesizing vitamin D at higher latitudes where there is less UVB, thus leading to the adaptation process.1 In this systematic review, we analyzed the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis and assessed the validity of evidence supporting this theory in the literature.

Methods

A search of PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Reviews database was conducted using the terms evolution, vitamin D, and skin to generate articles published from 2010 to 2022 that evaluated the influence of UVR-dependent production of vitamin D on skin pigmentation through historical migration patterns (Figure). Studies were excluded during an initial screening of abstracts followed by full-text assessment if they only had abstracts and if articles were inaccessible for review or in the form of case reports and commentaries.

The following data were extracted from each included study: reference citation, affiliated institutions of authors, author specialties, journal name, year of publication, study period, type of article, type of study, mechanism of adaptation, data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver, and data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver. Data concluding or supporting vitamin D as the driver were recorded from statistically significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotations. Data concluding or suggesting against vitamin D as the driver also were recorded from significant results, study conclusions, and direct quotes. The mechanism of adaptation was based on vitamin D synthesis modulation, melanin upregulation, genetic selections, genetic drift, mating patterns, increased vitamin D sensitivity, interbreeding, and diet.

Studies included in the analysis were placed into 1 of 3 categories: supporting, neutral, and against. Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) criteria were used to classify the level of evidence of each article.4 Each article’s level of evidence was then graded (Table 1). The SORT grading levels were based on quality and evidence type: level 1 signified good-quality, patient-oriented evidence; level 2 signified limited-quality, patient-oriented evidence; and level 3 signified other evidence.4

Results

Article Selection—A total of 229 articles were identified for screening, and 39 studies met inclusion criteria.1-3,5-40 Systematic and retrospective reviews were the most common types of studies. Genomic analysis/sequencing/genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were the most common methods of analysis. Of these 39 articles, 26 were classified as supporting the evolutionary vitamin D adaptation hypothesis, 10 were classified as neutral, and 3 were classified as against (Table 1).

Of the articles classified as supporting the vitamin D hypothesis, 13 articles were level 1 evidence, 9 were level 2, and 4 were level 3. Key findings supporting the vitamin D hypothesis included genetic natural selection favoring vitamin D synthesis genes at higher latitudes with lower UVR and the skin lightening that occurred to protect against vitamin D deficiency (Table 1). Specific genes supporting these findings included 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7), vitamin D receptor (VDR), tyrosinase (TYR), tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1), oculocutaneous albinism type 2 melanosomal transmembrane protein (OCA2), solute carrier family 45 member 2 (SLC45A2), solute carrier family 4 member 5 (SLC24A5), Kit ligand (KITLG), melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), and HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 (HERC2)(Table 2).

Of the articles classified as being against the vitamin D hypothesis, 1 article was level 1 evidence, 1 was level 2, and 1 was level 3. Key findings refuting the vitamin D hypothesis included similar amounts of vitamin D synthesis in contemporary dark- and light-pigmented individuals, vitamin D–rich diets in the late Paleolithic period and in early agriculturalists, and metabolic conservation being the primary driver (Table 1).

Of the articles classified as neutral to the hypothesis, 7 articles were level 1 evidence and 3 were level 2. Key findings of these articles included genetic selection favoring vitamin D synthesis only for populations at extremely northern latitudes, skin lightening that was sustained in northern latitudes from the neighboring human ancestor the chimpanzee, and evidence for long-term evolutionary pressures and short-term plastic adaptations in vitamin D genes (Table 1).

Comment

The importance of appropriate vitamin D levels is hypothesized as a potent driver in skin lightening because the vitamin is essential for many biochemical processes within the human body. Proper calcification of bones requires activated vitamin D to prevent rickets in childhood. Pelvic deformation in women with rickets can obstruct childbirth in primitive medical environments.15 This direct reproductive impairment suggests a strong selective pressure for skin lightening in populations that migrated northward to enhance vitamin D synthesis.

Of the 39 articles that we reviewed, the majority (n=26 [66.7%]) supported the hypothesis that vitamin D synthesis was the main driver behind skin lightening, whereas 3 (7.7%) did not support the hypothesis and 10 (25.6%) were neutral. Other leading theories explaining skin lightening included the idea that enhanced melanogenesis protected against folate degradation; genetic selection for light-skin alleles due to genetic drift; skin lightening being the result of sexual selection; and a combination of factors, including dietary choices, clothing preferences, and skin permeability barriers.

Articles With Supporting Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—As Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa, migration patterns demonstrated the correlation between distance from the equator and skin pigmentation from natural selection. Individuals with darker skin pigment required higher levels of UVR to synthesize vitamin D. According to Beleza et al,1 as humans migrated to areas of higher latitudes with lower levels of UVR, natural selection favored the development of lighter skin to maximize vitamin D production. Vitamin D is linked to calcium metabolism, and its deficiency can lead to bone malformations and poor immune function.35 Several genes affecting melanogenesis and skin pigment have been found to have geospatial patterns that map to different geographic locations of various populations, indicating how human migration patterns out of Africa created this natural selection for skin lightening. The gene KITLG—associated with lighter skin pigmentation—has been found in high frequencies in both European and East Asian populations and is proposed to have increased in frequency after the migration out of Africa. However, the genes TYRP1, SLC24A5, and SLC45A2 were found at high frequencies only in European populations, and this selection occurred 11,000 to 19,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum (15,000–20,000 years ago), demonstrating the selection for European over East Asian characteristics. During this period, seasonal changes increased the risk for vitamin D deficiency and provided an urgency for selection to a lighter skin pigment.1

The migration of H sapiens to northern latitudes prompted the selection of alleles that would increasevitamin D synthesis to counteract the reduced UV exposure. Genetic analysis studies have found key associations between genes encoding for the metabolism of vitamin D and pigmentation. Among this complex network are the essential downstream enzymes in the melanocortin receptor 1 pathway, including TYR and TYRP1. Forty-six of 960 single-nucleotide polymorphisms located in 29 different genes involved in skin pigmentation that were analyzed in a cohort of 2970 individuals were significantly associated with serum vitamin D levels (P<.05). The exocyst complex component 2 (EXOC2), TYR, and TYRP1 gene variants were shown to have the greatest influence on vitamin D status.9 These data reveal how pigment genotypes are predictive of vitamin D levels and the epistatic potential among many genes in this complex network.

Gene variation plays an important role in vitamin D status when comparing genetic polymorphisms in populations in northern latitudes to African populations. Vitamin D3 precursor availability is decreased by 7-DHCR catalyzing the precursors substrate to cholesterol. In a study using GWAS, it was found that “variations in DHCR7 may aid vitamin D production by conserving cutaneous 7-DHC levels. A high prevalence of DHCR7 variants were found in European and Northeast Asian populations but not in African populations, suggesting that selection occurred for these DHCR7 mutations in populations who migrated to more northern latitudes.5 Multilocus networks have been established between the VDR promotor and skin color genes (Table 2) that exhibit a strong in-Africa vs out-of-Africa frequency pattern. It also has been shown that genetic variation (suggesting a long-term evolutionary inclination) and epigenetic modification (indicative of short-term exposure) of VDR lends support to the vitamin D hypothesis. As latitude decreases, prevalence of VDR FokI (F allele), BsmI (B allele), ApaI (A allele), and TaqI (T allele) also decreases in a linear manner, linking latitude to VDR polymorphisms. Plasma vitamin D levels and photoperiod of conception—UV exposure during the periconceptional period—also were extrapolative of VDR methylation in a study involving 80 participants, where these 2 factors accounted for 17% of variance in methylation.6

Other noteworthy genes included HERC2, which has implications in the expression of OCA2 (melanocyte-specific transporter protein), and IRF4, which encodes for an important enzyme in folate-dependent melanin production. In an Australian cross-sectional study that analyzed vitamin D and pigmentation gene polymorphisms in conjunction with plasma vitamin D levels, the most notable rate of vitamin D loss occurred in individuals with the darkest pigmentation HERC2 (AA) genotype.31 In contrast, the lightest pigmentation HERC2 (GG) genotypes had increased vitamin D3 photosynthesis. Interestingly, the lightest interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) TT genotype and the darkest HERC2 AA genotype, rendering the greatest folate loss and largest synthesis of vitamin D3, were not seen in combination in any of the participants.30 In addition to HERC2, derived alleles from pigment-associated genes SLC24A5*A and SLC45A2*G demonstrated greater frequencies in Europeans (>90%) compared to Africans and East Asians, where the allelic frequencies were either rare or absent.1 This evidence delineates not only the complexity but also the strong relationship between skin pigmentation, latitude, and vitamin D status. The GWAS also have supported this concept. In comparing European populations to African populations, there was a 4-fold increase in the frequencies of “derived alleles of the vitamin D transport protein (GC, rs3755967), the 25(OH)D3 synthesizing enzyme (CYP2R1, rs10741657), VDR (rs2228570 (commonly known as FokI polymorphism), rs1544410 (Bsm1), and rs731236 (Taq1) and the VDR target genes CYP24A1 (rs17216707), CD14 (rs2569190), and CARD9 (rs4077515).”32

Articles With Evidence Against the Vitamin D Theory—This review analyzed the level of support for the theory that vitamin D was the main driver for skin lightening. Although most articles supported this theory, there were articles that listed other plausible counterarguments. Jablonski and Chaplin3 suggested that humans living in higher latitudes compensated for increased demand of vitamin D by placing cultural importance on a diet of vitamin D–rich foods and thus would not have experienced decreased vitamin D levels, which we hypothesize were the driver for skin lightening. Elias et al39 argued that initial pigment dilution may have instead served to improve metabolic conservation, as the authors found no evidence of rickets—the sequelae of vitamin D deficiency—in pre–industrial age human fossils. Elias and Williams38 proposed that differences in skin pigment are due to a more intact skin permeability barrier as “a requirement for life in a desiccating terrestrial environment,” which is seen in darker skin tones compared to lighter skin tones and thus can survive better in warmer climates with less risk of infections or dehydration.

Articles With Neutral Evidence for the Vitamin D Theory—Greaves41 argued against the idea that skin evolved to become lighter to protect against vitamin D deficiency. They proposed that the chimpanzee, which is the human’s most closely related species, had light skin covered by hair, and the loss of this hair led to exposed pale skin that created a need for increased melanin production for protection from UVR. Greaves41 stated that the MC1R gene (associated with darker pigmentation) was selected for in African populations, and those with pale skin retained their original pigment as they migrated to higher latitudes. Further research has demonstrated that the genetic natural selection for skin pigment is a complex process that involves multiple gene variants found throughout cultures across the globe.

Conclusion

Skin pigmentation has continuously evolved alongside humans. Genetic selection for lighter skin coincides with a favorable selection for genes involved in vitamin D synthesis as humans migrated to northern latitudes, which enabled humans to produce adequate levels of exogenous vitamin D in low-UVR areas and in turn promoted survival. Early humans without access to supplementation or foods rich in vitamin D acquired vitamin D primarily through sunlight. In comparison to modern society, where vitamin D supplementation is accessible and human lifespans are prolonged, lighter skin tone is now a risk factor for malignant cancers of the skin rather than being a protective adaptation. Current sun behavior recommendations conclude that the body’s need for vitamin D is satisfied by UV exposure to the arms, legs, hands, and/or face for only 5 to 30 minutes between 10

The hypothesis that skin lightening primarily was driven by the need for vitamin D can only be partially supported by our review. Studies have shown that there is a corresponding complex network of genes that determines skin pigmentation as well as vitamin D synthesis and conservation. However, there is sufficient evidence that skin lightening is multifactorial in nature, and vitamin D alone may not be the sole driver. The information in this review can be used by health care providers to educate patients on sun protection, given the lesser threat of severe vitamin D deficiency in developed communities today that have access to adequate nutrition and supplementation.

Skin lightening and its coinciding evolutionary drivers are a rather neglected area of research. Due to heterogeneous cohorts and conservative data analysis, GWAS studies run the risk of type II error, yielding a limitation in our data analysis.9 Furthermore, the data regarding specific time frames in evolutionary skin lightening as well as the intensity of gene polymorphisms are limited.1 Further studies are needed to determine the interconnectedness of the current skin-lightening theories to identify other important factors that may play a role in the process. Determining the key event can help us better understand skin-adaptation mechanisms and create a framework for understanding the vital process involved in adaptation, survival, and disease manifestation in different patient populations.

The risk for developing skin cancer can be somewhat attributed to variations in skin pigmentation. Historically, lighter skin pigmentation has been observed in populations living in higher latitudes and darker pigmentation in populations near the equator. Although skin pigmentation is a conglomeration of genetic and environmental factors, anthropologic studies have demonstrated an association of human skin lightening with historic human migratory patterns.1 It is postulated that migration to latitudes with less UVB light penetration has resulted in a compensatory natural selection of lighter skin types. Furthermore, the driving force behind this migration-associated skin lightening has remained unclear.1