User login

Honor thy parents? Understanding parricide and associated spree killings

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

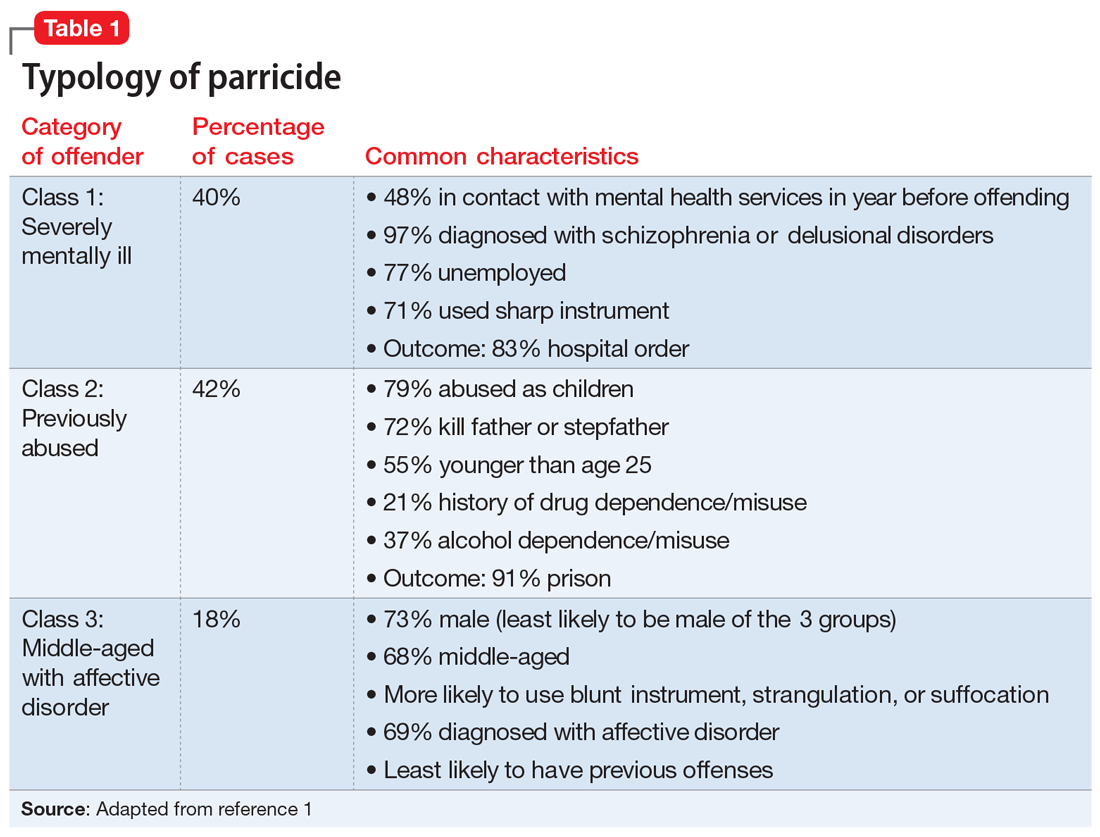

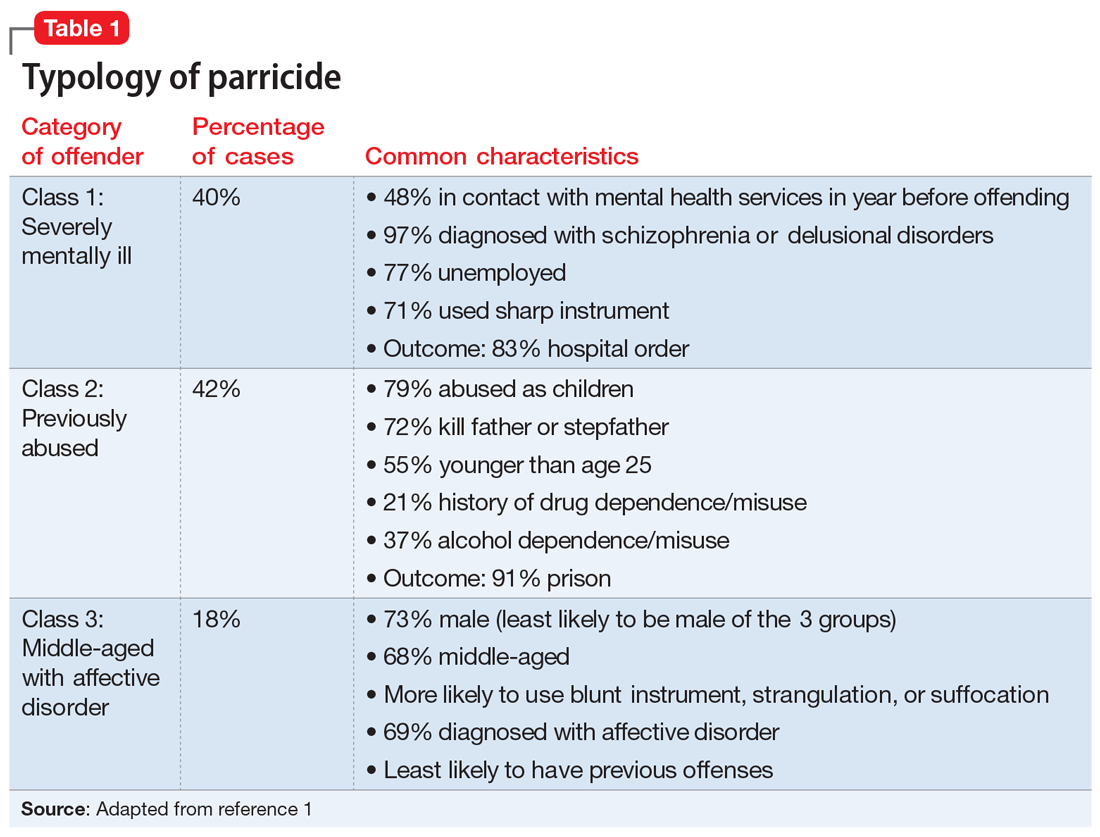

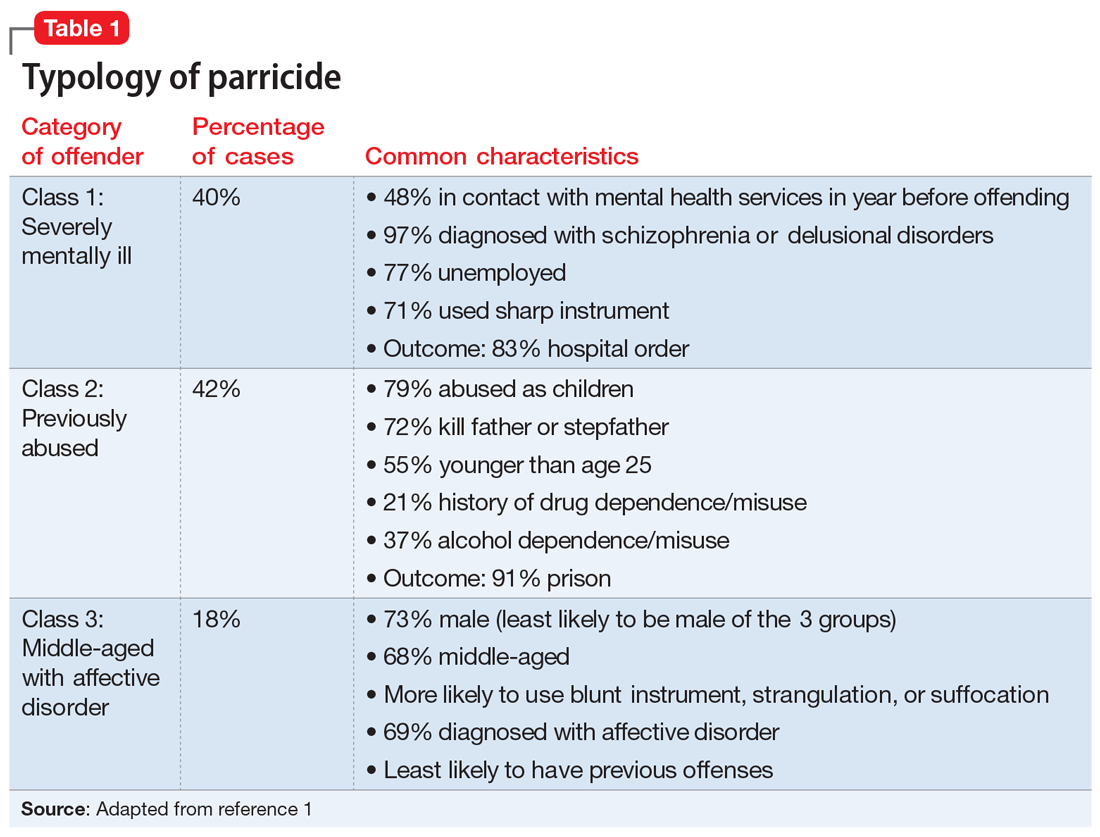

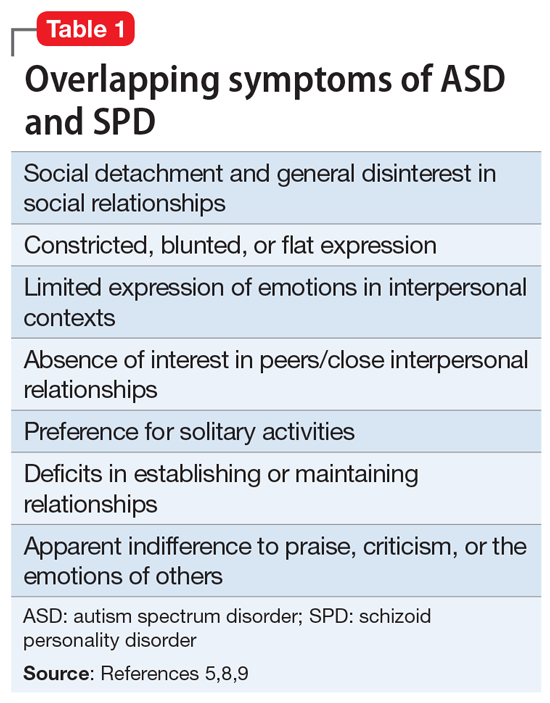

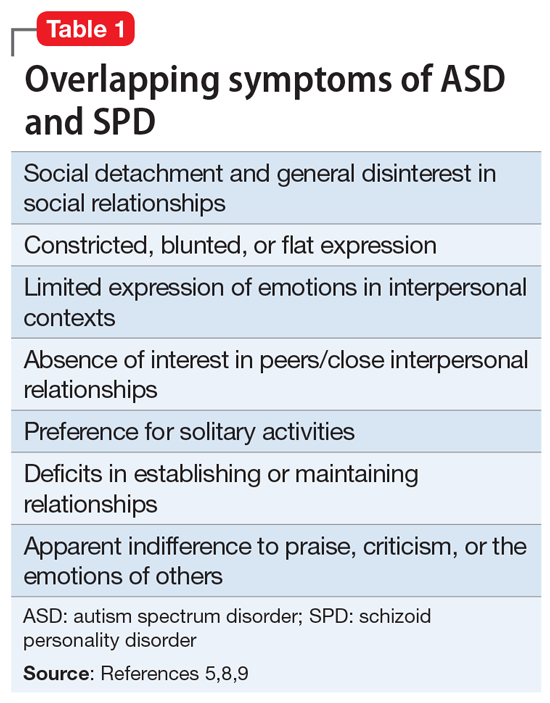

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

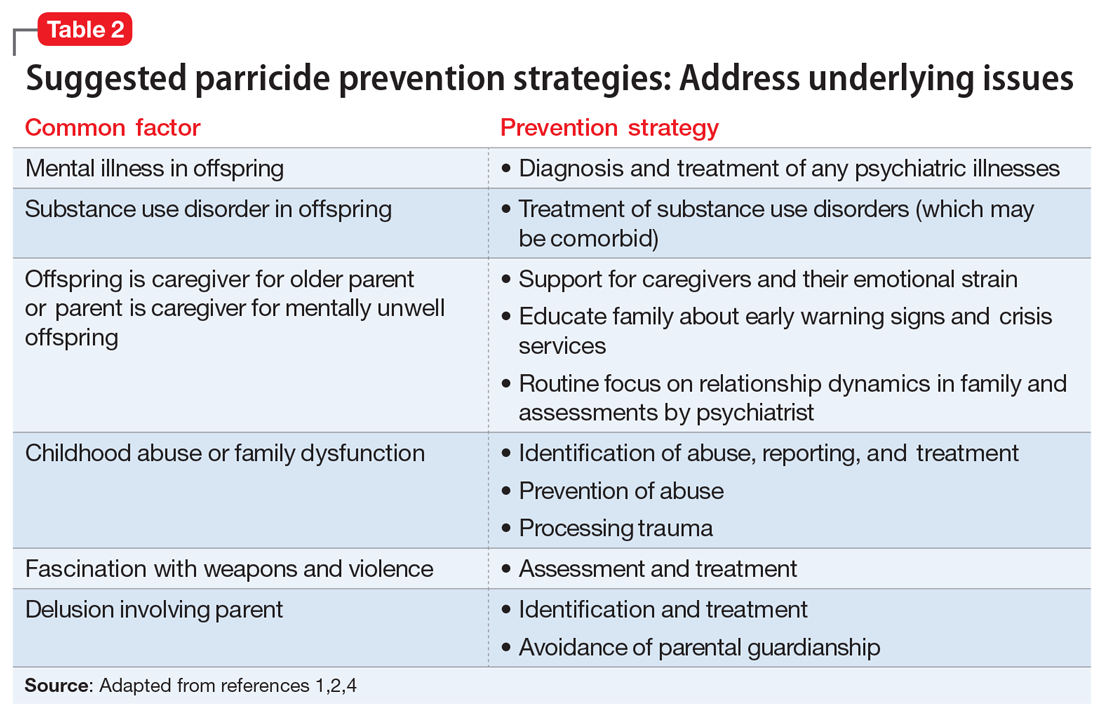

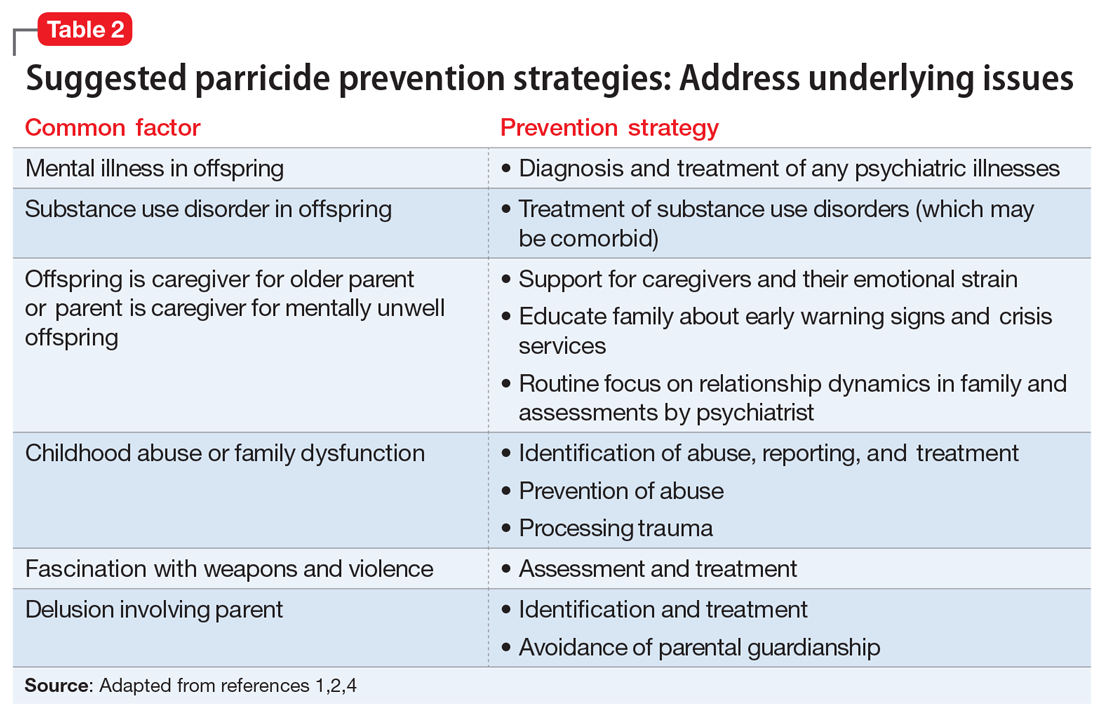

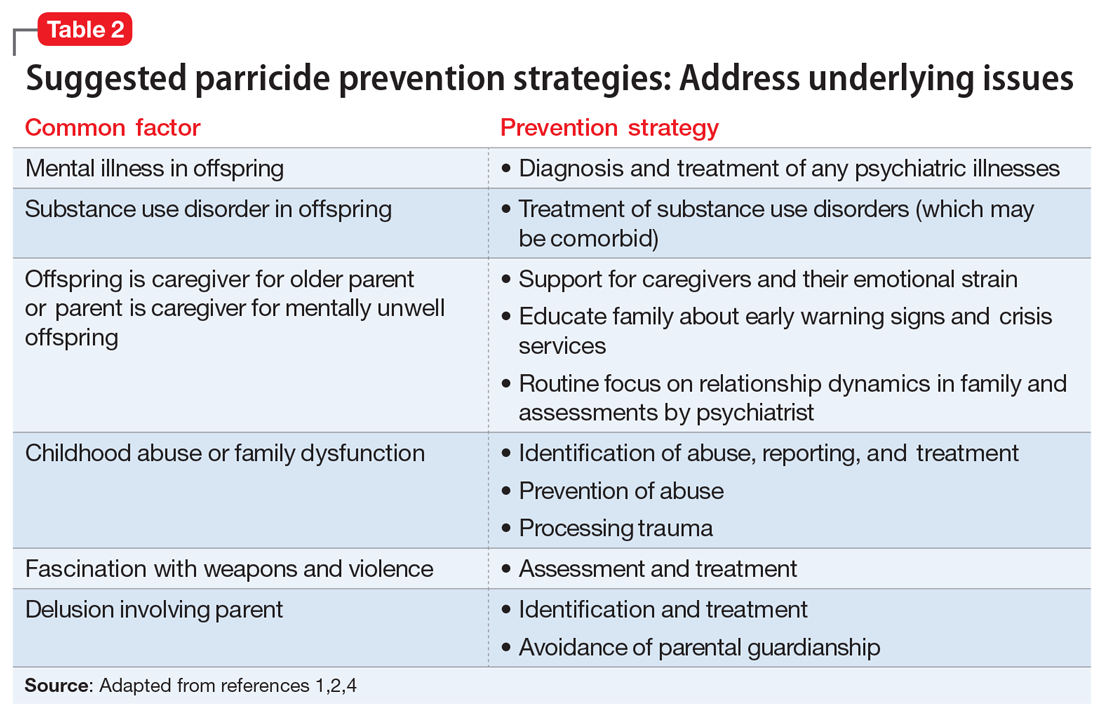

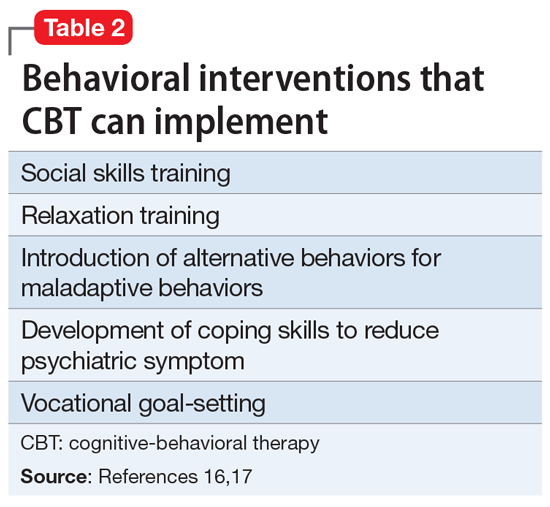

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

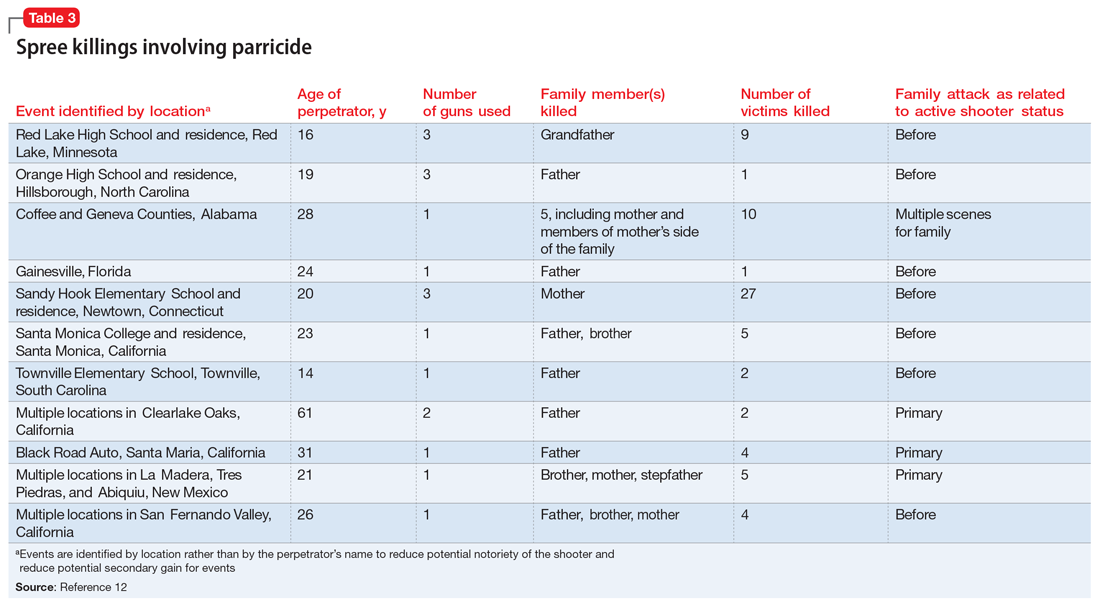

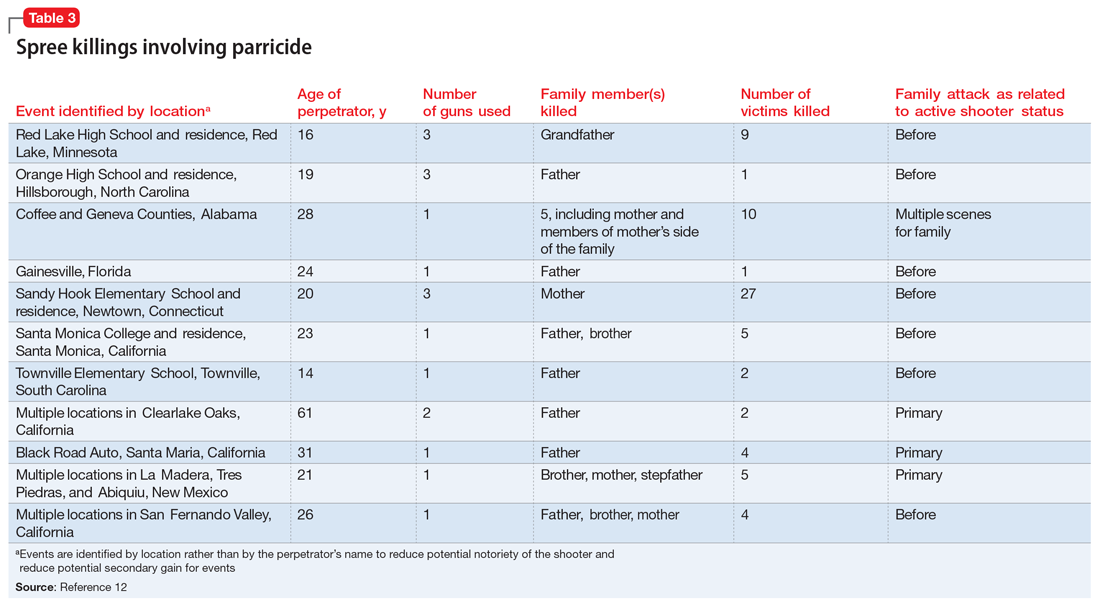

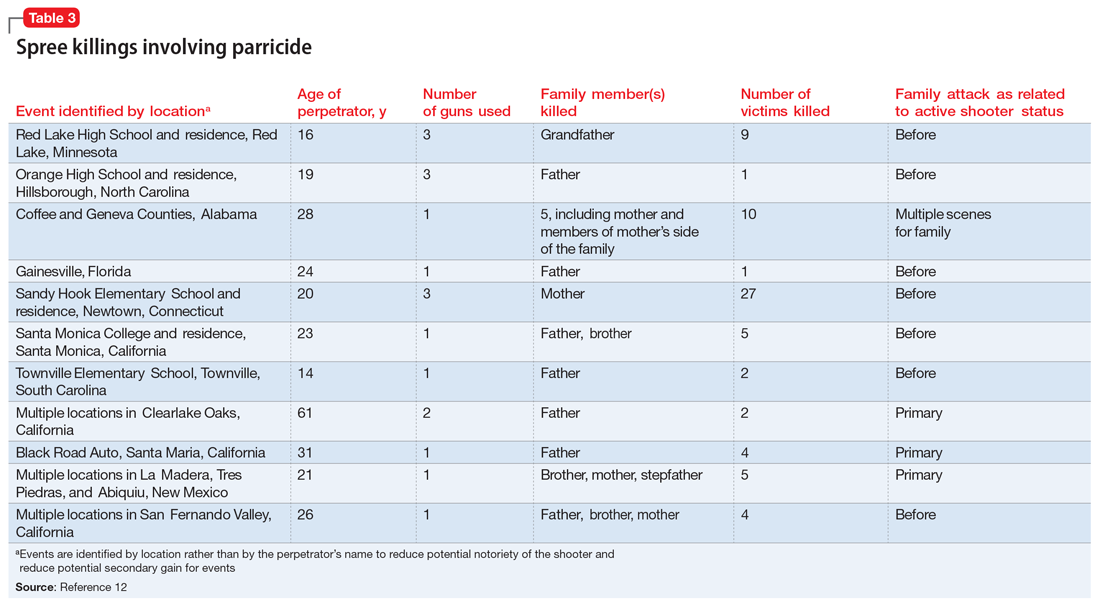

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

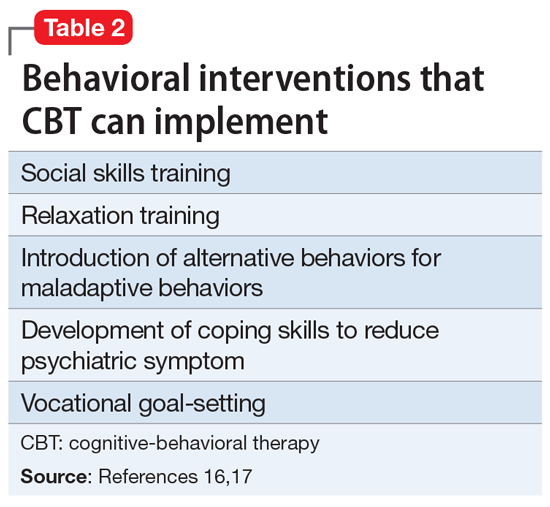

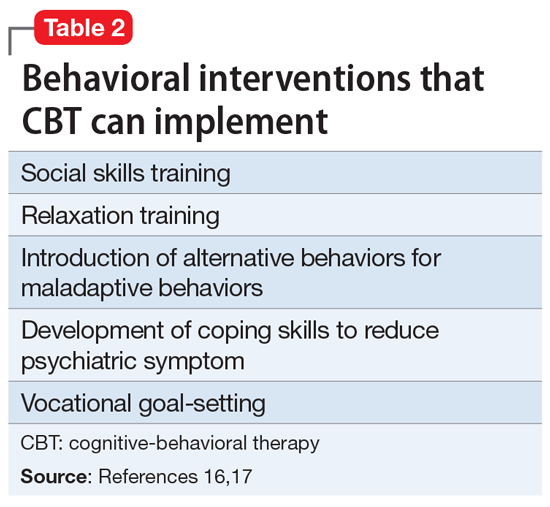

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

Antipsychotic-induced priapism: Mitigating the risk

Mr. J, age 35, is brought to the hospital from prison due to priapism that does not improve with treatment. He says he has had priapism 5 times previously, with the first incidence occurring “years ago” due to trazodone.

Recently, he has been receiving risperidone, which the treatment team believes is the cause of his current priapism. His medical history includes asthma, schizophrenia, hypertension, seizures, and sickle cell trait. Mr. J is experiencing auditory hallucinations, which he describes as “continuous, neutral voices that are annoying.” He would like relief from his auditory hallucinations and is willing to change his antipsychotic, but does not want additional treatment for his priapism. His present medications include risperidone, 1 mg twice a day, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, benztropine, 1 mg twice a day, and phenytoin, 500 mg/d at bedtime.

Priapism is a prolonged, persistent, and often painful erection that occurs without sexual stimulation. Although relatively rare, it can result in potentially serious long-term complications, including impotence and gangrene, and requires immediate evaluation and management.

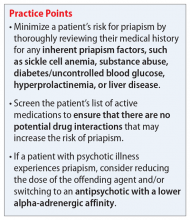

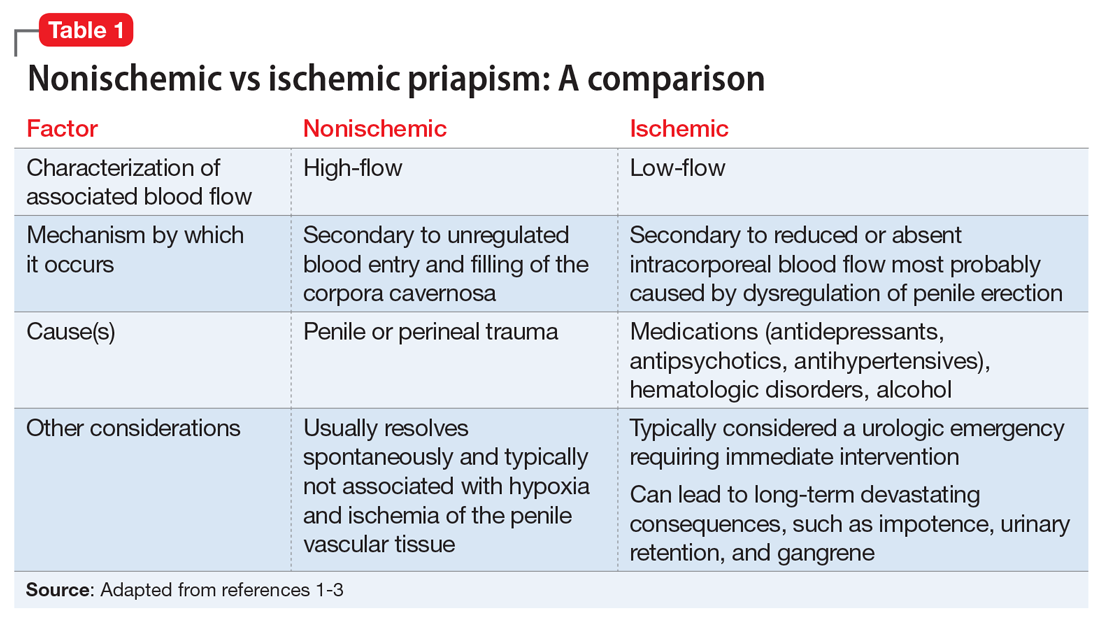

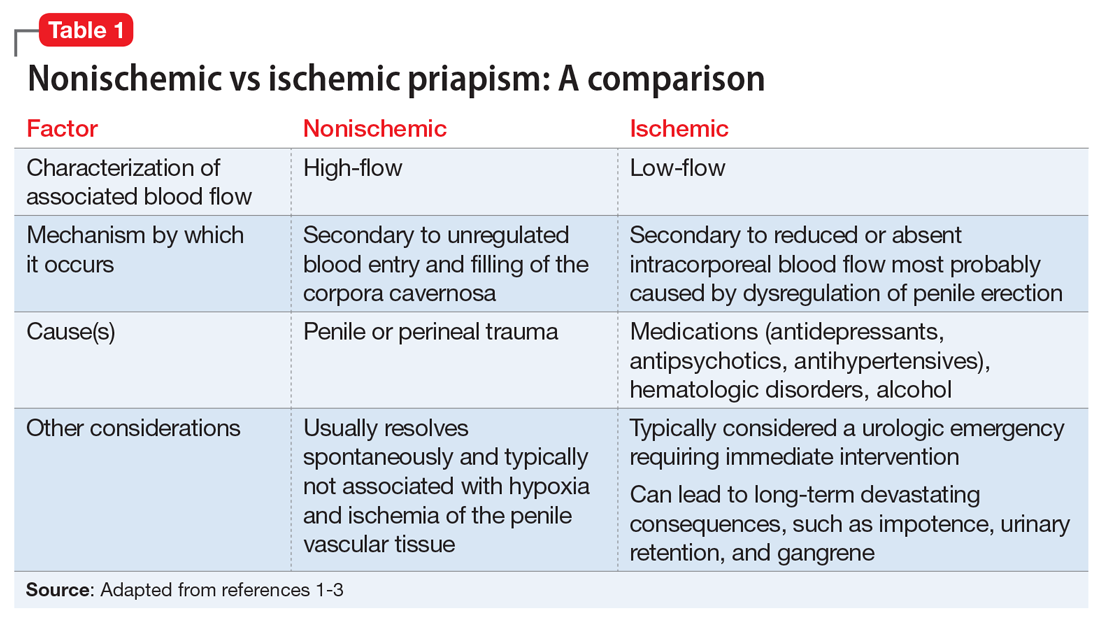

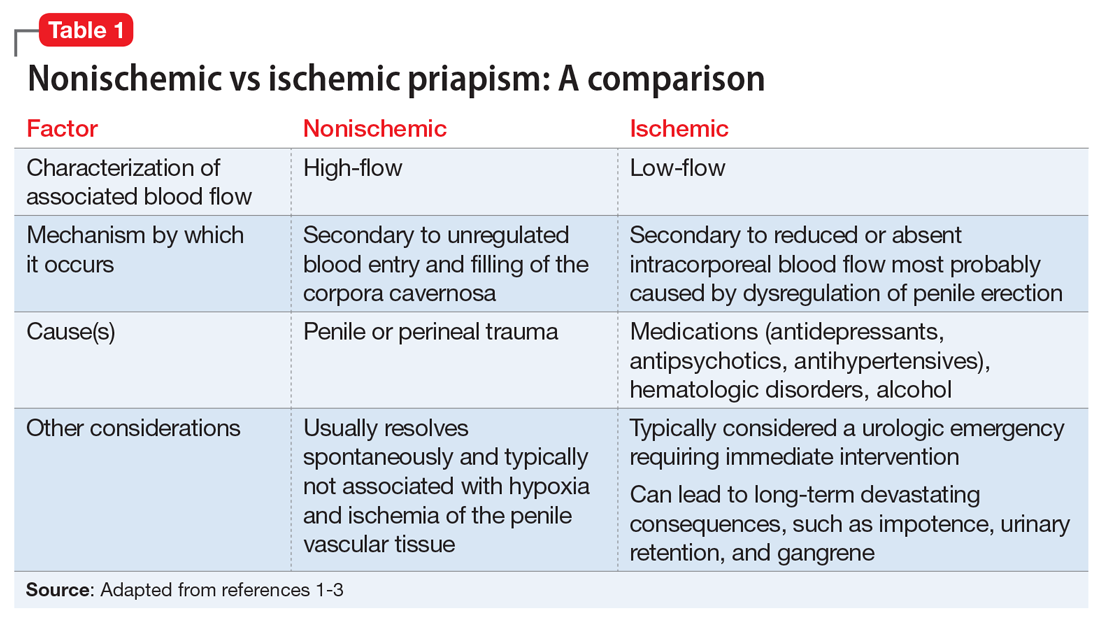

There are 2 types of priapism: nonischemic, or “high-flow,” priapism, and ischemic, or “low-flow,” priapism (Table 1). While nonischemic priapism is typically caused by penile or perineal trauma, ischemic priapism can occur as a result of medications, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antihypertensives, or hematological conditions such as sickle cell disease.1 Other risk factors associated with priapism include substance abuse, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes, and liver disease.4

Antipsychotic-induced priapism

Medication-induced priapism is a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR). Of the medication classes associated with priapism, antipsychotics have the highest incidence and account for approximately 20% of all cases.1

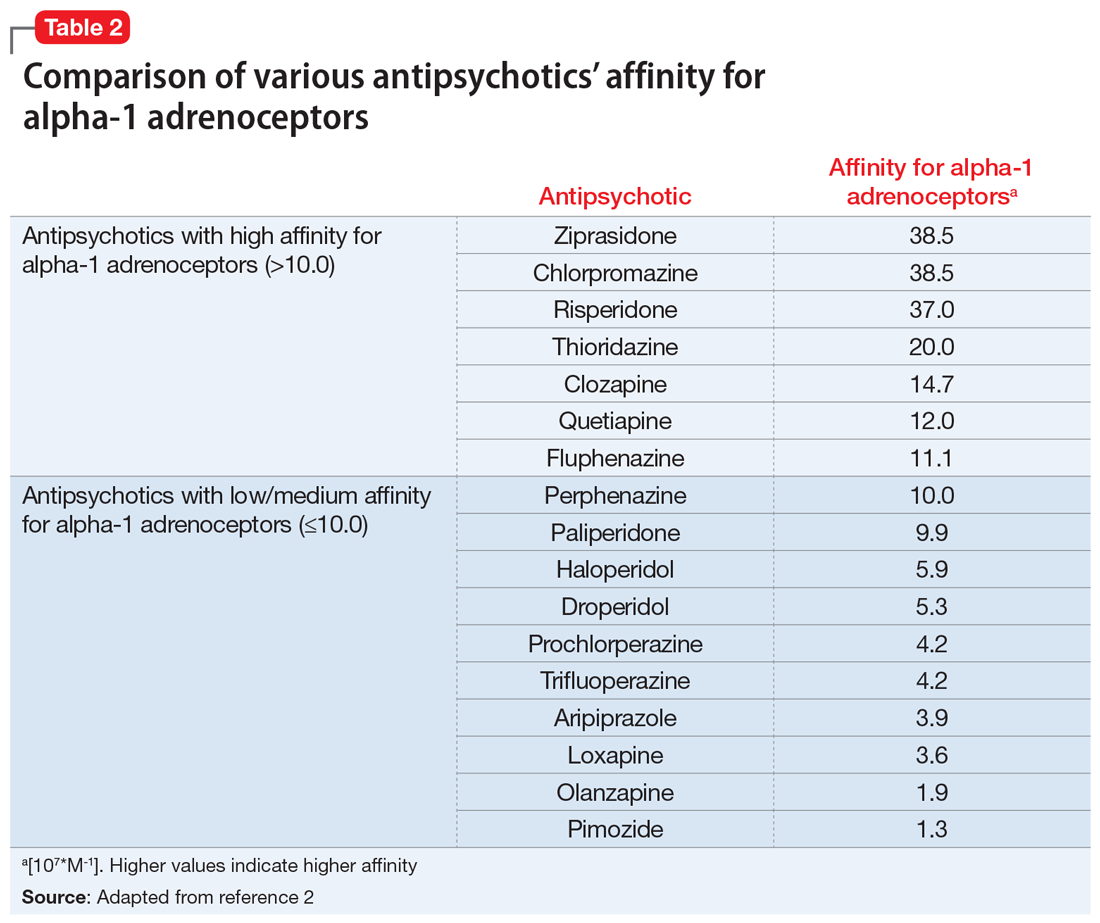

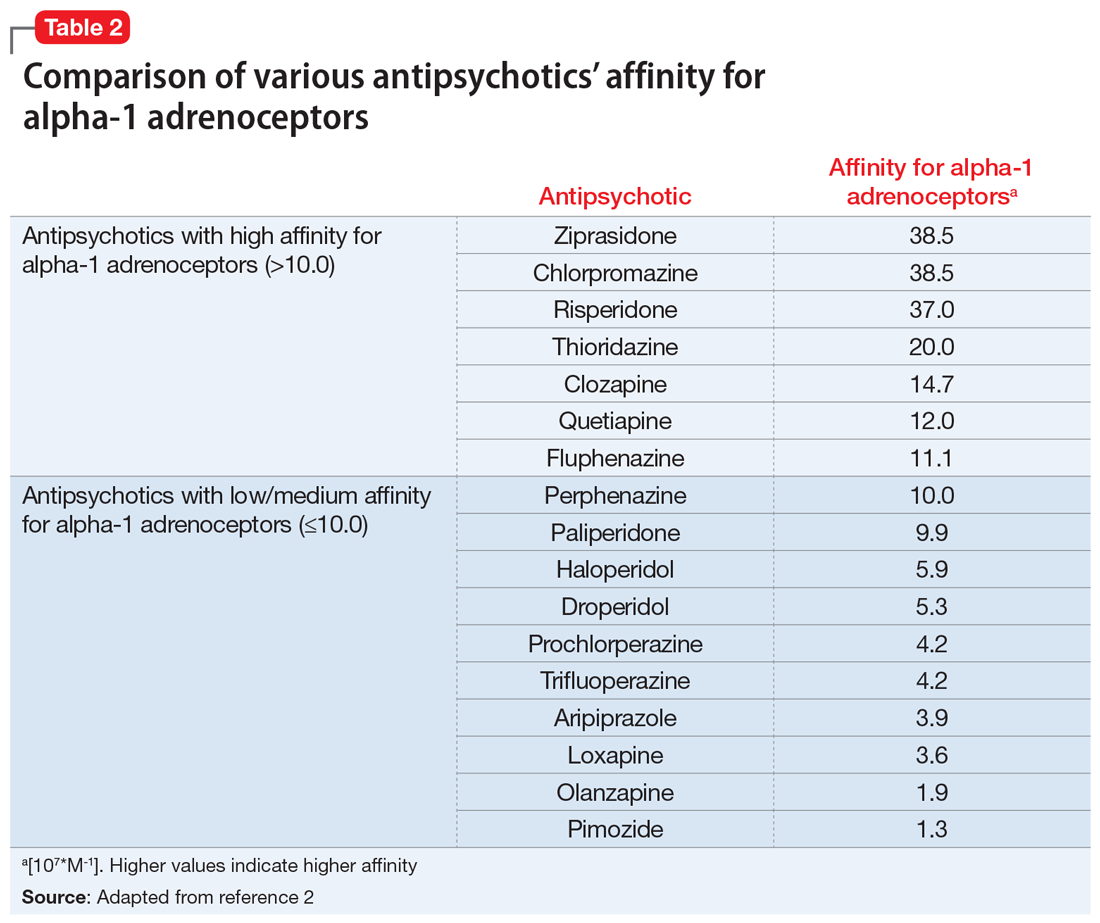

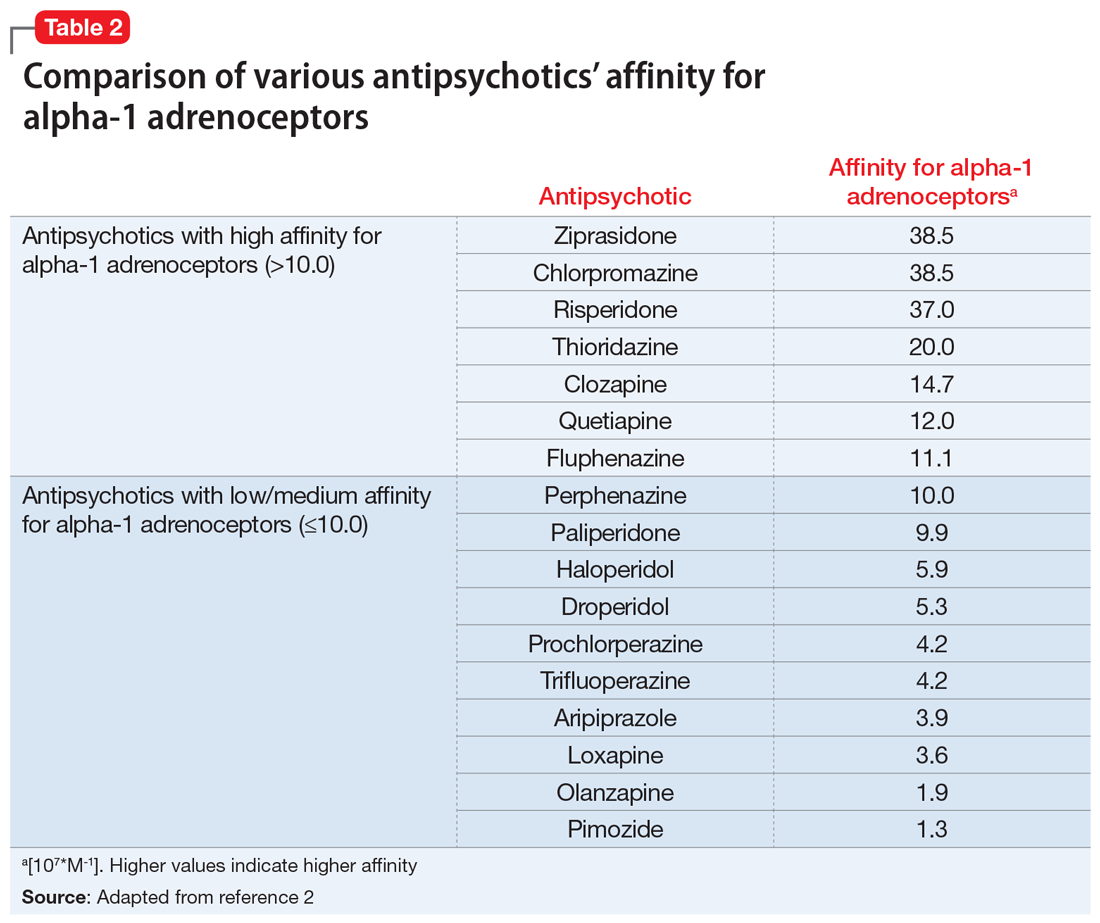

The mechanism of priapism associated with antipsychotics is thought to be related to alpha-1 blockade in the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Although antipsychotics within each class share common characteristics, each agent has a unique profile of receptor affinities. As such, antipsychotics have varying affinities for the alpha-adrenergic receptor (Table 2). Agents such as ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, and risperidone—which have the highest affinity for the alpha-1 adrenoceptors—may be more likely to cause priapism compared with agents with lower affinity, such as olanzapine. Priapism may occur at any time during antipsychotic treatment, and does not appear to be dose-related.

Continue to: Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism...

Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism

Patients who are receiving multiple medications as treatment for chronic medical or psychiatric conditions have an increased likelihood of experiencing drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that lead to adverse effects.

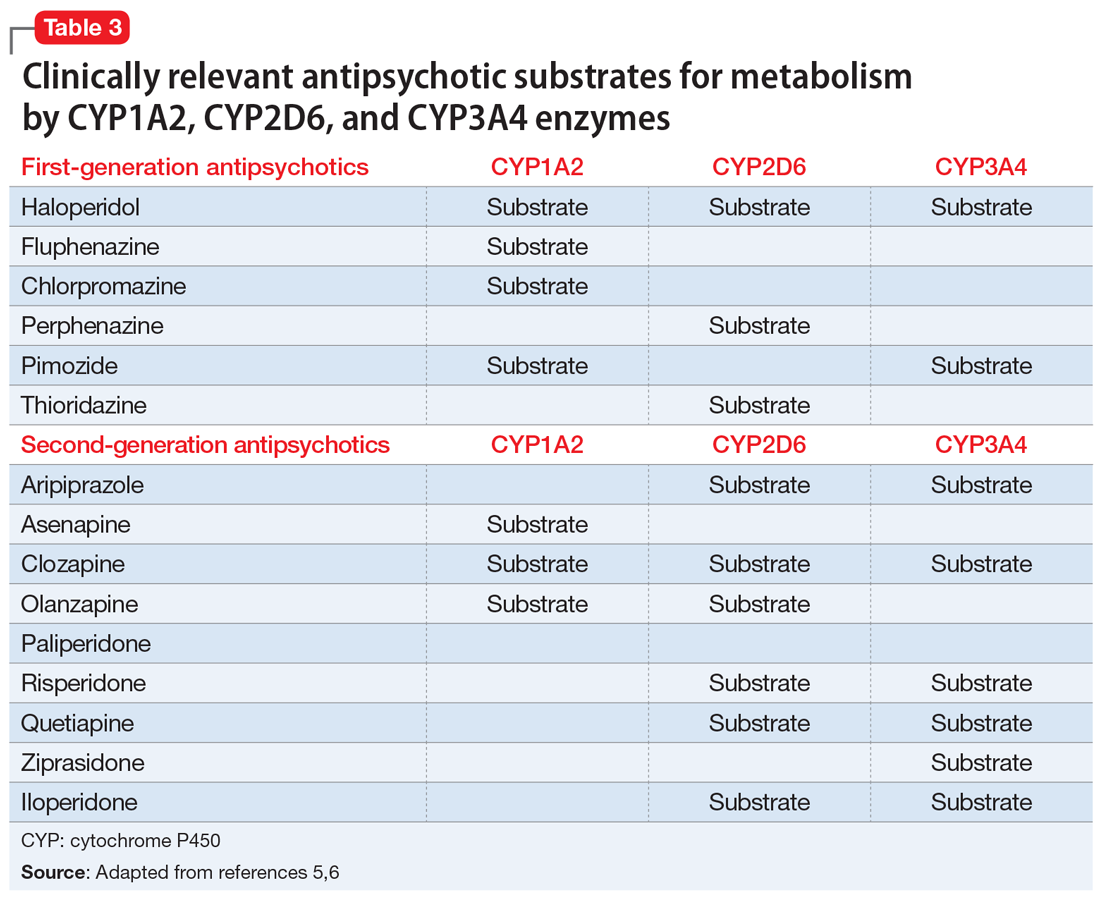

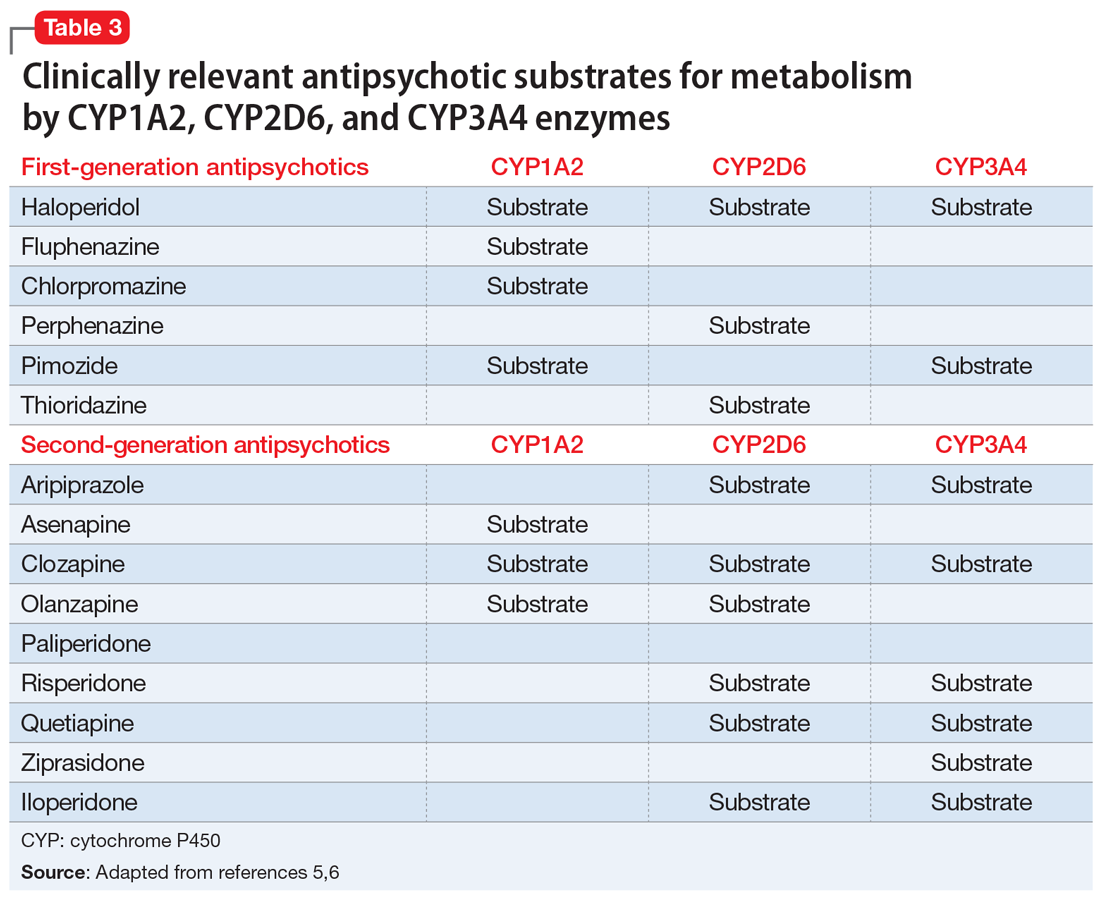

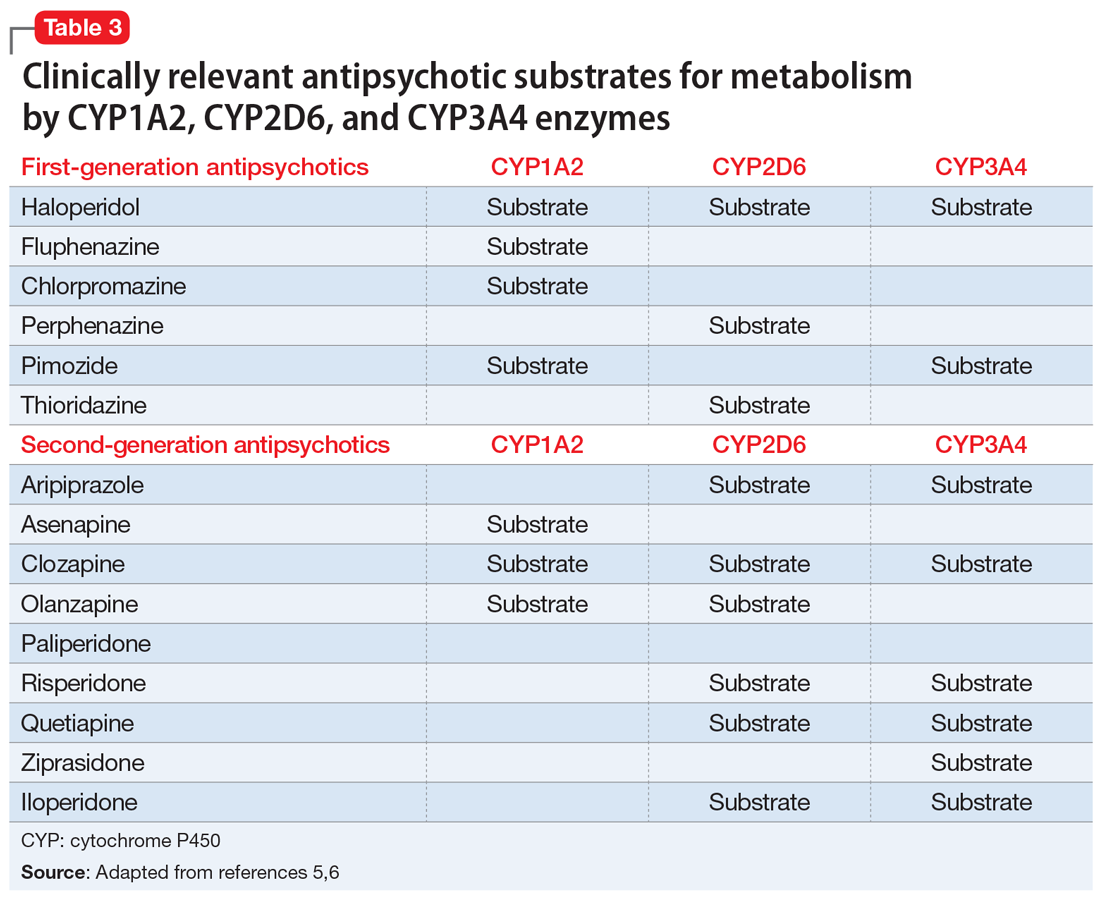

Various case reports have described priapism as a result of DDIs related to antipsychotic agents combined with other psychotropic or nonpsychotropic medications.3 Most of these DDIs have been attributed to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4/5, which are major enzymes implicated in the metabolism of antipsychotics (Table 3).

It is imperative to be vigilant during the concomitant administration of antipsychotics with other medications that may be substrates, inducers, or inhibitors of CYP enzymes, as this could alter the metabolism and kinetics of the antipsychotic and result in ADRs such as priapism. For example, drug interactions exist between strong CYP2D6 inhibitors—such as the antidepressants paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP2D6, such as risperidone, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and perphenazine. This interaction can lead to higher levels of the antipsychotic, which would increase the patient’s risk of experiencing ADRs. Because psychotic illnesses and depression/anxiety often coexist, it is not uncommon for individuals with these conditions to be receiving both an antipsychotic and an antidepressant.

Because there is a high incidence of comorbidities such as HIV and cardiovascular disease among individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians must also be cognizant of any nonpsychotropic medications the patient may be taking. For instance, clinically relevant DDIs exist between protease inhibitors, such as ritonavir, a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor, and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP3A4, such as pimozide, aripiprazole, and quetiapine.

Mitigating the risk of priapism

Although there are associated risk factors for priapism, there are no concrete indicators to predict the onset or development of the condition. The best predictor may be a history of prolonged and painless erections.3

As such, when choosing an antipsychotic, it is critical to screen the patient for the previously mentioned risk factors, including the presence of medications with strong alpha-1 receptor affinity and CYP interactions, especially to minimize the risk of recurrence of priapism in those with prior or similar episodes. Management of patients with priapism due to antipsychotics has involved reducing the dose of the offending agent and/or changing the medication to one with a lower alpha-adrenergic affinity (Table 22).

Similar to most situations, management is patient-specific and depends on several factors, including the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disease, history/severity of priapism and treatment, concurrent medication list, etc. For example, although clozapine is considered to have relatively high affinity for the alpha-1 receptor, it is also the agent of choice for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Risks and benefits must be weighed on a individualized basis. Case reports have described symptom improvement via lowering the dose of clozapine and adding on or switching to an antipsychotic agent with minimal alpha-1 receptor affinity.4

After considering Mr. J’s history, risk factors, and preferences, the treatment team discontinues risperidone and initiates haloperidol, 5 mg twice a day. Soon after, Mr. J no longer experiences priapism.

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. Mol Diag Ther 9. 1998;371-379. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809050-00004

2. Andersohn F, Schmedt N, Weinmann S, et al. Priapism associated with antipsychotics: role of alpha1 adrenoceptor affinity. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):68-71. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c8273d

3. Sood S, James W, Bailon MJ. Priapism associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):9-17.

4. Sinkeviciute I, Kroken RA, Johnsen E. Priapism in antipsychotic drug use: a rare but important side effect. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:496364. doi:10.1155/2012/496364

5. Mora F, Martín JDD, Zubillaga E, et al. CYP450 and its implications in the clinical use of antipsychotic drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2015;5(176):1-10. doi:10.4172/2161-1459.1000176

6. Puangpetch A, Vanwong N, Nuntamool N, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms and their influence on risperidone treatment. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016;9:131-147. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S107772

Mr. J, age 35, is brought to the hospital from prison due to priapism that does not improve with treatment. He says he has had priapism 5 times previously, with the first incidence occurring “years ago” due to trazodone.

Recently, he has been receiving risperidone, which the treatment team believes is the cause of his current priapism. His medical history includes asthma, schizophrenia, hypertension, seizures, and sickle cell trait. Mr. J is experiencing auditory hallucinations, which he describes as “continuous, neutral voices that are annoying.” He would like relief from his auditory hallucinations and is willing to change his antipsychotic, but does not want additional treatment for his priapism. His present medications include risperidone, 1 mg twice a day, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, benztropine, 1 mg twice a day, and phenytoin, 500 mg/d at bedtime.

Priapism is a prolonged, persistent, and often painful erection that occurs without sexual stimulation. Although relatively rare, it can result in potentially serious long-term complications, including impotence and gangrene, and requires immediate evaluation and management.

There are 2 types of priapism: nonischemic, or “high-flow,” priapism, and ischemic, or “low-flow,” priapism (Table 1). While nonischemic priapism is typically caused by penile or perineal trauma, ischemic priapism can occur as a result of medications, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antihypertensives, or hematological conditions such as sickle cell disease.1 Other risk factors associated with priapism include substance abuse, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes, and liver disease.4

Antipsychotic-induced priapism

Medication-induced priapism is a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR). Of the medication classes associated with priapism, antipsychotics have the highest incidence and account for approximately 20% of all cases.1

The mechanism of priapism associated with antipsychotics is thought to be related to alpha-1 blockade in the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Although antipsychotics within each class share common characteristics, each agent has a unique profile of receptor affinities. As such, antipsychotics have varying affinities for the alpha-adrenergic receptor (Table 2). Agents such as ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, and risperidone—which have the highest affinity for the alpha-1 adrenoceptors—may be more likely to cause priapism compared with agents with lower affinity, such as olanzapine. Priapism may occur at any time during antipsychotic treatment, and does not appear to be dose-related.

Continue to: Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism...

Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism

Patients who are receiving multiple medications as treatment for chronic medical or psychiatric conditions have an increased likelihood of experiencing drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that lead to adverse effects.

Various case reports have described priapism as a result of DDIs related to antipsychotic agents combined with other psychotropic or nonpsychotropic medications.3 Most of these DDIs have been attributed to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4/5, which are major enzymes implicated in the metabolism of antipsychotics (Table 3).

It is imperative to be vigilant during the concomitant administration of antipsychotics with other medications that may be substrates, inducers, or inhibitors of CYP enzymes, as this could alter the metabolism and kinetics of the antipsychotic and result in ADRs such as priapism. For example, drug interactions exist between strong CYP2D6 inhibitors—such as the antidepressants paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP2D6, such as risperidone, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and perphenazine. This interaction can lead to higher levels of the antipsychotic, which would increase the patient’s risk of experiencing ADRs. Because psychotic illnesses and depression/anxiety often coexist, it is not uncommon for individuals with these conditions to be receiving both an antipsychotic and an antidepressant.

Because there is a high incidence of comorbidities such as HIV and cardiovascular disease among individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians must also be cognizant of any nonpsychotropic medications the patient may be taking. For instance, clinically relevant DDIs exist between protease inhibitors, such as ritonavir, a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor, and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP3A4, such as pimozide, aripiprazole, and quetiapine.

Mitigating the risk of priapism

Although there are associated risk factors for priapism, there are no concrete indicators to predict the onset or development of the condition. The best predictor may be a history of prolonged and painless erections.3

As such, when choosing an antipsychotic, it is critical to screen the patient for the previously mentioned risk factors, including the presence of medications with strong alpha-1 receptor affinity and CYP interactions, especially to minimize the risk of recurrence of priapism in those with prior or similar episodes. Management of patients with priapism due to antipsychotics has involved reducing the dose of the offending agent and/or changing the medication to one with a lower alpha-adrenergic affinity (Table 22).

Similar to most situations, management is patient-specific and depends on several factors, including the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disease, history/severity of priapism and treatment, concurrent medication list, etc. For example, although clozapine is considered to have relatively high affinity for the alpha-1 receptor, it is also the agent of choice for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Risks and benefits must be weighed on a individualized basis. Case reports have described symptom improvement via lowering the dose of clozapine and adding on or switching to an antipsychotic agent with minimal alpha-1 receptor affinity.4

After considering Mr. J’s history, risk factors, and preferences, the treatment team discontinues risperidone and initiates haloperidol, 5 mg twice a day. Soon after, Mr. J no longer experiences priapism.

Mr. J, age 35, is brought to the hospital from prison due to priapism that does not improve with treatment. He says he has had priapism 5 times previously, with the first incidence occurring “years ago” due to trazodone.

Recently, he has been receiving risperidone, which the treatment team believes is the cause of his current priapism. His medical history includes asthma, schizophrenia, hypertension, seizures, and sickle cell trait. Mr. J is experiencing auditory hallucinations, which he describes as “continuous, neutral voices that are annoying.” He would like relief from his auditory hallucinations and is willing to change his antipsychotic, but does not want additional treatment for his priapism. His present medications include risperidone, 1 mg twice a day, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, benztropine, 1 mg twice a day, and phenytoin, 500 mg/d at bedtime.

Priapism is a prolonged, persistent, and often painful erection that occurs without sexual stimulation. Although relatively rare, it can result in potentially serious long-term complications, including impotence and gangrene, and requires immediate evaluation and management.

There are 2 types of priapism: nonischemic, or “high-flow,” priapism, and ischemic, or “low-flow,” priapism (Table 1). While nonischemic priapism is typically caused by penile or perineal trauma, ischemic priapism can occur as a result of medications, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antihypertensives, or hematological conditions such as sickle cell disease.1 Other risk factors associated with priapism include substance abuse, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes, and liver disease.4

Antipsychotic-induced priapism

Medication-induced priapism is a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR). Of the medication classes associated with priapism, antipsychotics have the highest incidence and account for approximately 20% of all cases.1

The mechanism of priapism associated with antipsychotics is thought to be related to alpha-1 blockade in the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Although antipsychotics within each class share common characteristics, each agent has a unique profile of receptor affinities. As such, antipsychotics have varying affinities for the alpha-adrenergic receptor (Table 2). Agents such as ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, and risperidone—which have the highest affinity for the alpha-1 adrenoceptors—may be more likely to cause priapism compared with agents with lower affinity, such as olanzapine. Priapism may occur at any time during antipsychotic treatment, and does not appear to be dose-related.

Continue to: Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism...

Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism

Patients who are receiving multiple medications as treatment for chronic medical or psychiatric conditions have an increased likelihood of experiencing drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that lead to adverse effects.

Various case reports have described priapism as a result of DDIs related to antipsychotic agents combined with other psychotropic or nonpsychotropic medications.3 Most of these DDIs have been attributed to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4/5, which are major enzymes implicated in the metabolism of antipsychotics (Table 3).

It is imperative to be vigilant during the concomitant administration of antipsychotics with other medications that may be substrates, inducers, or inhibitors of CYP enzymes, as this could alter the metabolism and kinetics of the antipsychotic and result in ADRs such as priapism. For example, drug interactions exist between strong CYP2D6 inhibitors—such as the antidepressants paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP2D6, such as risperidone, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and perphenazine. This interaction can lead to higher levels of the antipsychotic, which would increase the patient’s risk of experiencing ADRs. Because psychotic illnesses and depression/anxiety often coexist, it is not uncommon for individuals with these conditions to be receiving both an antipsychotic and an antidepressant.

Because there is a high incidence of comorbidities such as HIV and cardiovascular disease among individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians must also be cognizant of any nonpsychotropic medications the patient may be taking. For instance, clinically relevant DDIs exist between protease inhibitors, such as ritonavir, a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor, and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP3A4, such as pimozide, aripiprazole, and quetiapine.

Mitigating the risk of priapism

Although there are associated risk factors for priapism, there are no concrete indicators to predict the onset or development of the condition. The best predictor may be a history of prolonged and painless erections.3

As such, when choosing an antipsychotic, it is critical to screen the patient for the previously mentioned risk factors, including the presence of medications with strong alpha-1 receptor affinity and CYP interactions, especially to minimize the risk of recurrence of priapism in those with prior or similar episodes. Management of patients with priapism due to antipsychotics has involved reducing the dose of the offending agent and/or changing the medication to one with a lower alpha-adrenergic affinity (Table 22).

Similar to most situations, management is patient-specific and depends on several factors, including the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disease, history/severity of priapism and treatment, concurrent medication list, etc. For example, although clozapine is considered to have relatively high affinity for the alpha-1 receptor, it is also the agent of choice for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Risks and benefits must be weighed on a individualized basis. Case reports have described symptom improvement via lowering the dose of clozapine and adding on or switching to an antipsychotic agent with minimal alpha-1 receptor affinity.4

After considering Mr. J’s history, risk factors, and preferences, the treatment team discontinues risperidone and initiates haloperidol, 5 mg twice a day. Soon after, Mr. J no longer experiences priapism.

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. Mol Diag Ther 9. 1998;371-379. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809050-00004

2. Andersohn F, Schmedt N, Weinmann S, et al. Priapism associated with antipsychotics: role of alpha1 adrenoceptor affinity. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):68-71. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c8273d

3. Sood S, James W, Bailon MJ. Priapism associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):9-17.

4. Sinkeviciute I, Kroken RA, Johnsen E. Priapism in antipsychotic drug use: a rare but important side effect. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:496364. doi:10.1155/2012/496364

5. Mora F, Martín JDD, Zubillaga E, et al. CYP450 and its implications in the clinical use of antipsychotic drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2015;5(176):1-10. doi:10.4172/2161-1459.1000176

6. Puangpetch A, Vanwong N, Nuntamool N, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms and their influence on risperidone treatment. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016;9:131-147. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S107772

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. Mol Diag Ther 9. 1998;371-379. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809050-00004

2. Andersohn F, Schmedt N, Weinmann S, et al. Priapism associated with antipsychotics: role of alpha1 adrenoceptor affinity. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):68-71. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c8273d

3. Sood S, James W, Bailon MJ. Priapism associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):9-17.

4. Sinkeviciute I, Kroken RA, Johnsen E. Priapism in antipsychotic drug use: a rare but important side effect. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:496364. doi:10.1155/2012/496364

5. Mora F, Martín JDD, Zubillaga E, et al. CYP450 and its implications in the clinical use of antipsychotic drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2015;5(176):1-10. doi:10.4172/2161-1459.1000176

6. Puangpetch A, Vanwong N, Nuntamool N, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms and their influence on risperidone treatment. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016;9:131-147. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S107772

Depressed and awkward: Is it more than that?

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

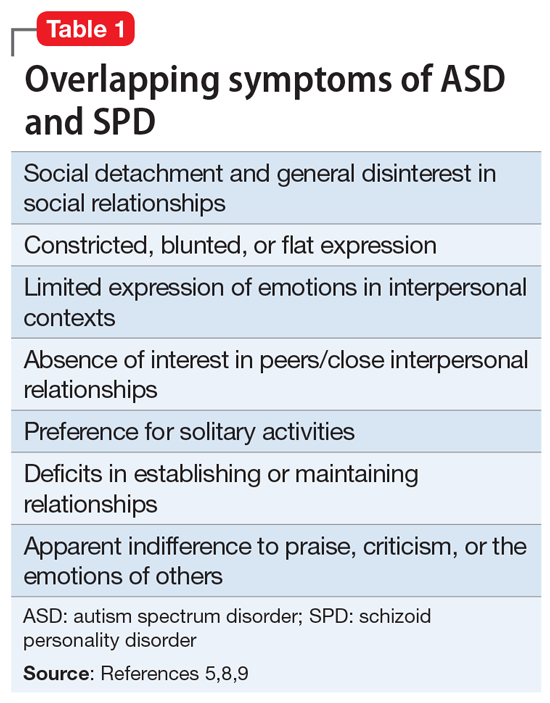

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13

Cognitive ability as measured by IQ has also been found to be a factor in receiving a diagnosis of ASD. In a 2010 secondary analysis of a population-based study of the prevalence of ASD, Giarelli et al14found that girls with cognitive impairments as measured by IQ were less likely to be diagnosed with ASD than boys with cognitive impairment, despite meeting the criteria for ASD. Females tend to exhibit fewer repetitive behaviors than males, and tend to be more likely to show accompanying intellectual disability, which suggests that females with ASD may go unrecognized when they exhibit average intelligence with less impairment of behavior and subtler manifestation of social and communication deficits.15 Consequently, females tend to receive this diagnosis later than males.

Continue to: Treatment...

TREATMENT Adding CBT