User login

Concurrent use of DOAC and tamoxifen does not increase hemorrhage risk in BC

Key clinical point: The risk for hemorrhage was not significantly different in patients with breast cancer (BC) aged ≥ 66 years who received direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) concurrently with tamoxifen vs aromatase inhibitors (AI).

Major finding: During a median follow-up of 166 days, the risk for major hemorrhage requiring an emergency department visit or hospitalization (2.5% vs 3.3%; weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.68; 95% CI 0.44-1.06) or any hemorrhage (4.9% vs 4.6%; weighted HR 1.04; 95% CI 0.75-1.43) was not higher with tamoxifen+DOAC compared with AI+DOAC.

Study details: Findings are from a population-based, retrospective cohort study including 4753 patients aged ≥ 66 years with BC who were prescribed tamoxifen or AI concurrently with a DOAC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research and ICES. Some authors declared serving on advisory boards of or receiving grants, personal fees, or travel expenses from several sources.

Source: Wang T-F et al. Hemorrhage risk among patients with breast cancer receiving concurrent direct oral anticoagulants with tamoxifen vs aromatase inhibitors. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219128 (Jun 28). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19128

Key clinical point: The risk for hemorrhage was not significantly different in patients with breast cancer (BC) aged ≥ 66 years who received direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) concurrently with tamoxifen vs aromatase inhibitors (AI).

Major finding: During a median follow-up of 166 days, the risk for major hemorrhage requiring an emergency department visit or hospitalization (2.5% vs 3.3%; weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.68; 95% CI 0.44-1.06) or any hemorrhage (4.9% vs 4.6%; weighted HR 1.04; 95% CI 0.75-1.43) was not higher with tamoxifen+DOAC compared with AI+DOAC.

Study details: Findings are from a population-based, retrospective cohort study including 4753 patients aged ≥ 66 years with BC who were prescribed tamoxifen or AI concurrently with a DOAC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research and ICES. Some authors declared serving on advisory boards of or receiving grants, personal fees, or travel expenses from several sources.

Source: Wang T-F et al. Hemorrhage risk among patients with breast cancer receiving concurrent direct oral anticoagulants with tamoxifen vs aromatase inhibitors. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219128 (Jun 28). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19128

Key clinical point: The risk for hemorrhage was not significantly different in patients with breast cancer (BC) aged ≥ 66 years who received direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) concurrently with tamoxifen vs aromatase inhibitors (AI).

Major finding: During a median follow-up of 166 days, the risk for major hemorrhage requiring an emergency department visit or hospitalization (2.5% vs 3.3%; weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.68; 95% CI 0.44-1.06) or any hemorrhage (4.9% vs 4.6%; weighted HR 1.04; 95% CI 0.75-1.43) was not higher with tamoxifen+DOAC compared with AI+DOAC.

Study details: Findings are from a population-based, retrospective cohort study including 4753 patients aged ≥ 66 years with BC who were prescribed tamoxifen or AI concurrently with a DOAC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research and ICES. Some authors declared serving on advisory boards of or receiving grants, personal fees, or travel expenses from several sources.

Source: Wang T-F et al. Hemorrhage risk among patients with breast cancer receiving concurrent direct oral anticoagulants with tamoxifen vs aromatase inhibitors. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219128 (Jun 28). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19128

DBT lowers risk for advanced BC diagnosis in women with dense breasts and at high risk

Key clinical point: Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) reduced the likelihood of advanced breast cancer (BC) diagnosis compared with digital mammography in women with extremely dense breasts and a high risk for BC.

Major finding: Overall screening outcomes per 1000 examinations were similar with DBT vs digital mammography for interval invasive cancer (difference −0.04; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.06); however, the advanced cancer detection rate was lower in women with extremely dense breasts and a high BC risk (difference −0.53; 95% CI −0.97 to −0.10).

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 504,427 women with no history of BC or mastectomy who underwent 1,003,900 digital mammography screening examinations or 374,002 DBT screening examinations.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, and other sources. Some authors declared receiving grants, consulting fees, or royalties from or serving as consultants or on the editorial board for several sources.

Source: Kerlikowske K et al. Association of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography with risk of interval invasive and advanced breast cancer. JAMA. 2022;327(22):2220–2230 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.7672

Key clinical point: Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) reduced the likelihood of advanced breast cancer (BC) diagnosis compared with digital mammography in women with extremely dense breasts and a high risk for BC.

Major finding: Overall screening outcomes per 1000 examinations were similar with DBT vs digital mammography for interval invasive cancer (difference −0.04; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.06); however, the advanced cancer detection rate was lower in women with extremely dense breasts and a high BC risk (difference −0.53; 95% CI −0.97 to −0.10).

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 504,427 women with no history of BC or mastectomy who underwent 1,003,900 digital mammography screening examinations or 374,002 DBT screening examinations.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, and other sources. Some authors declared receiving grants, consulting fees, or royalties from or serving as consultants or on the editorial board for several sources.

Source: Kerlikowske K et al. Association of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography with risk of interval invasive and advanced breast cancer. JAMA. 2022;327(22):2220–2230 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.7672

Key clinical point: Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) reduced the likelihood of advanced breast cancer (BC) diagnosis compared with digital mammography in women with extremely dense breasts and a high risk for BC.

Major finding: Overall screening outcomes per 1000 examinations were similar with DBT vs digital mammography for interval invasive cancer (difference −0.04; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.06); however, the advanced cancer detection rate was lower in women with extremely dense breasts and a high BC risk (difference −0.53; 95% CI −0.97 to −0.10).

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 504,427 women with no history of BC or mastectomy who underwent 1,003,900 digital mammography screening examinations or 374,002 DBT screening examinations.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, and other sources. Some authors declared receiving grants, consulting fees, or royalties from or serving as consultants or on the editorial board for several sources.

Source: Kerlikowske K et al. Association of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography with risk of interval invasive and advanced breast cancer. JAMA. 2022;327(22):2220–2230 (Jun 14). Doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.7672

HER2-low metastatic BC: Phase 3 establishes trastuzumab deruxtecan as a new standard-of-care

Key clinical point: Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs physician’s choice of chemotherapy reduced the risk for disease progression or death by ~50% in previously treated patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-low metastatic breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs chemotherapy significantly improved the median progression-free survival in the overall cohort of patients (hazard ratio for disease progression/death [HR] 0.50; P < .001), irrespective of the hormone-receptor status (positive: HR 0.51; P < .001, or negative: HR 0.46; 95% CI 0.24-0.89). The incidence of grade ≥3 adverse events was 52.6% with trastuzumab deruxtecan and 67.4% with chemotherapy.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 DESTINY-Breast04 study including 557 patients with HER2-low metastatic BC who were previously treated with 1 or 2 lines of chemotherapy and were randomly assigned to receive trastuzumab deruxtecan or physician’s choice of chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca. Four authors declared being employees or stockholders of Daiichi Sankyo, and the other authors reported ties with various sources, including AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo.

Source: Modi S et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:9-20 (Jun 5). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203690

Key clinical point: Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs physician’s choice of chemotherapy reduced the risk for disease progression or death by ~50% in previously treated patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-low metastatic breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs chemotherapy significantly improved the median progression-free survival in the overall cohort of patients (hazard ratio for disease progression/death [HR] 0.50; P < .001), irrespective of the hormone-receptor status (positive: HR 0.51; P < .001, or negative: HR 0.46; 95% CI 0.24-0.89). The incidence of grade ≥3 adverse events was 52.6% with trastuzumab deruxtecan and 67.4% with chemotherapy.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 DESTINY-Breast04 study including 557 patients with HER2-low metastatic BC who were previously treated with 1 or 2 lines of chemotherapy and were randomly assigned to receive trastuzumab deruxtecan or physician’s choice of chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca. Four authors declared being employees or stockholders of Daiichi Sankyo, and the other authors reported ties with various sources, including AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo.

Source: Modi S et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:9-20 (Jun 5). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203690

Key clinical point: Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs physician’s choice of chemotherapy reduced the risk for disease progression or death by ~50% in previously treated patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-low metastatic breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs chemotherapy significantly improved the median progression-free survival in the overall cohort of patients (hazard ratio for disease progression/death [HR] 0.50; P < .001), irrespective of the hormone-receptor status (positive: HR 0.51; P < .001, or negative: HR 0.46; 95% CI 0.24-0.89). The incidence of grade ≥3 adverse events was 52.6% with trastuzumab deruxtecan and 67.4% with chemotherapy.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 DESTINY-Breast04 study including 557 patients with HER2-low metastatic BC who were previously treated with 1 or 2 lines of chemotherapy and were randomly assigned to receive trastuzumab deruxtecan or physician’s choice of chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca. Four authors declared being employees or stockholders of Daiichi Sankyo, and the other authors reported ties with various sources, including AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo.

Source: Modi S et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:9-20 (Jun 5). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203690

Nonphysician Clinicians in Dermatology Residencies: Cross-sectional Survey on Residency Education

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

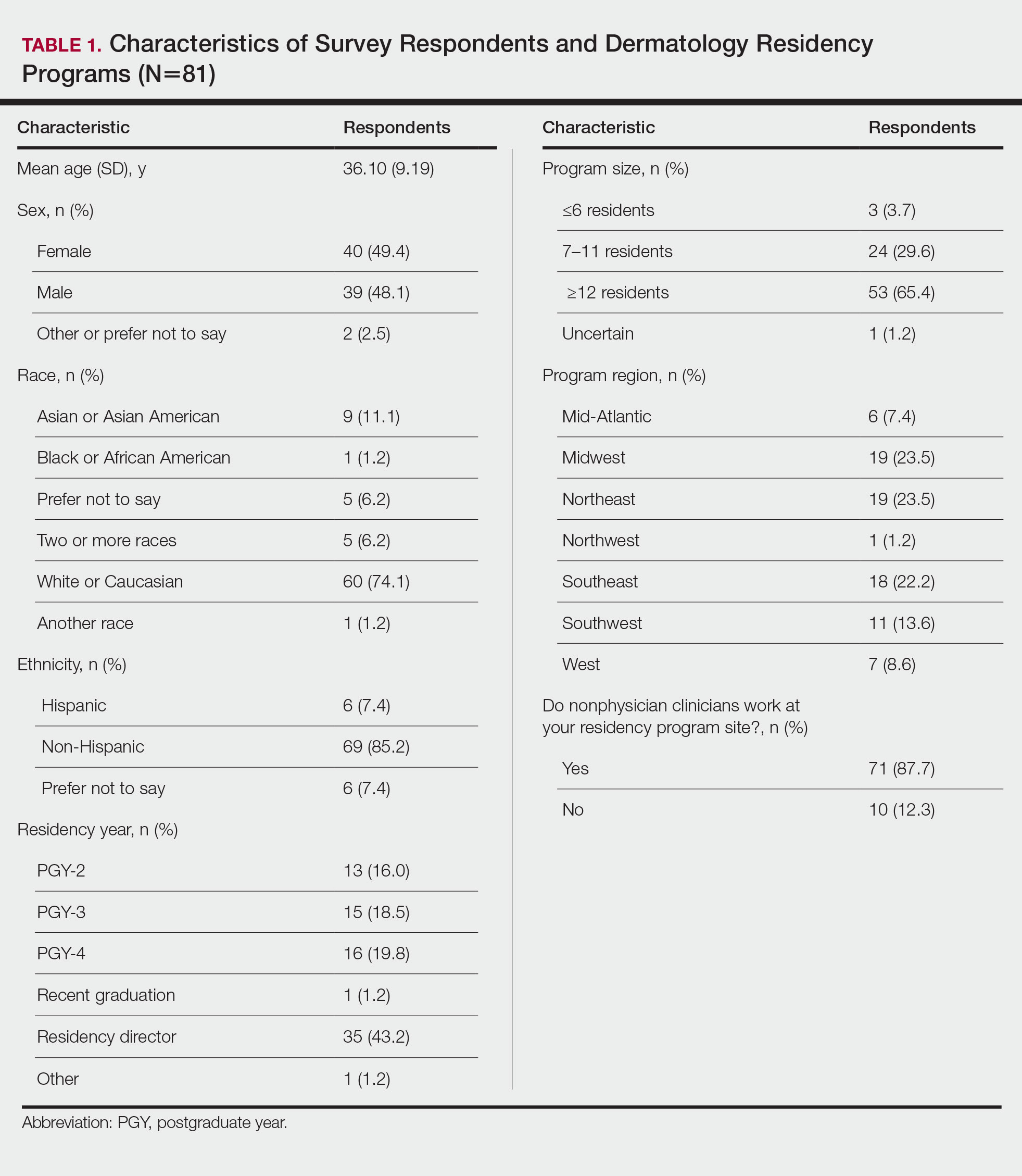

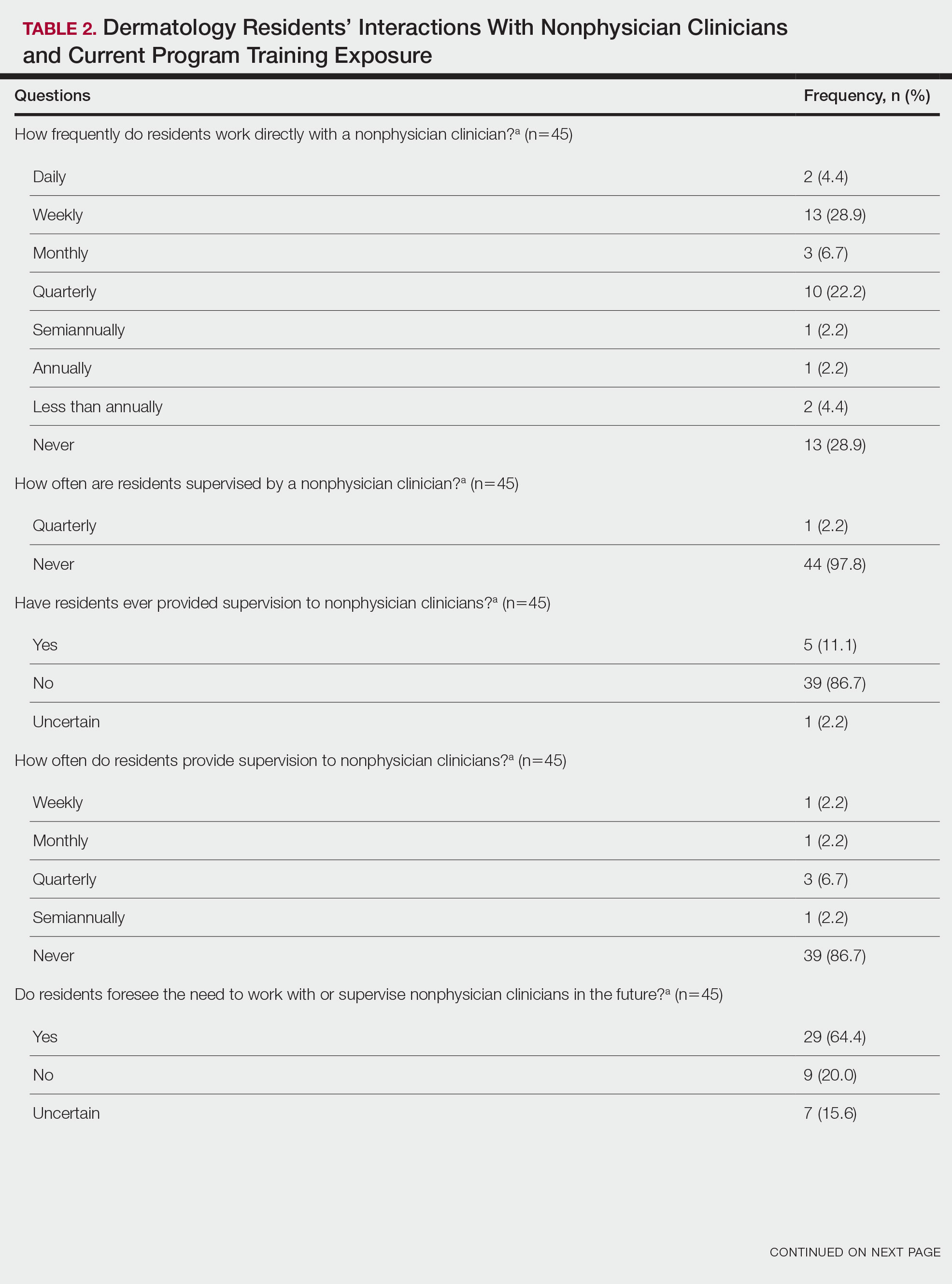

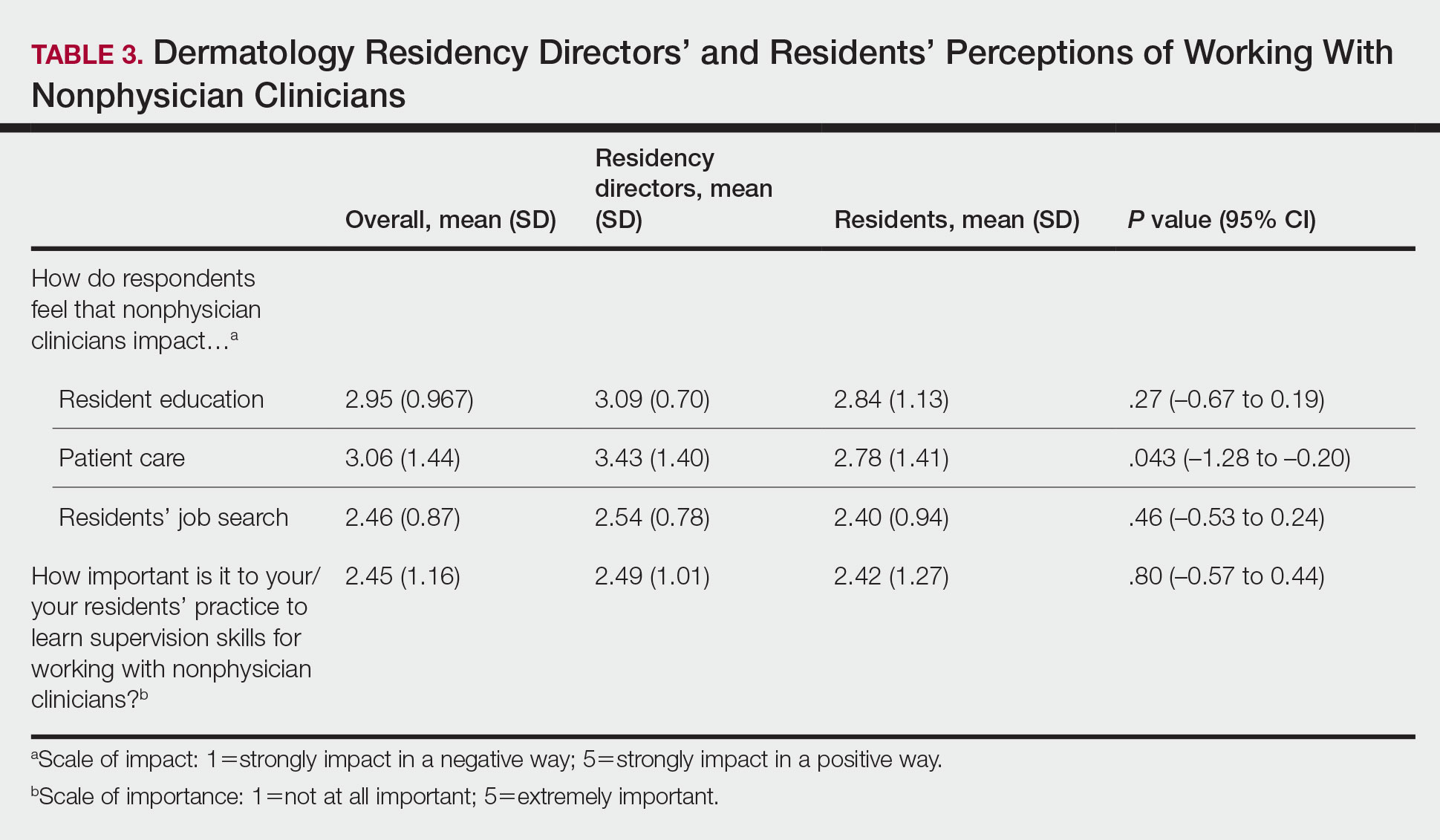

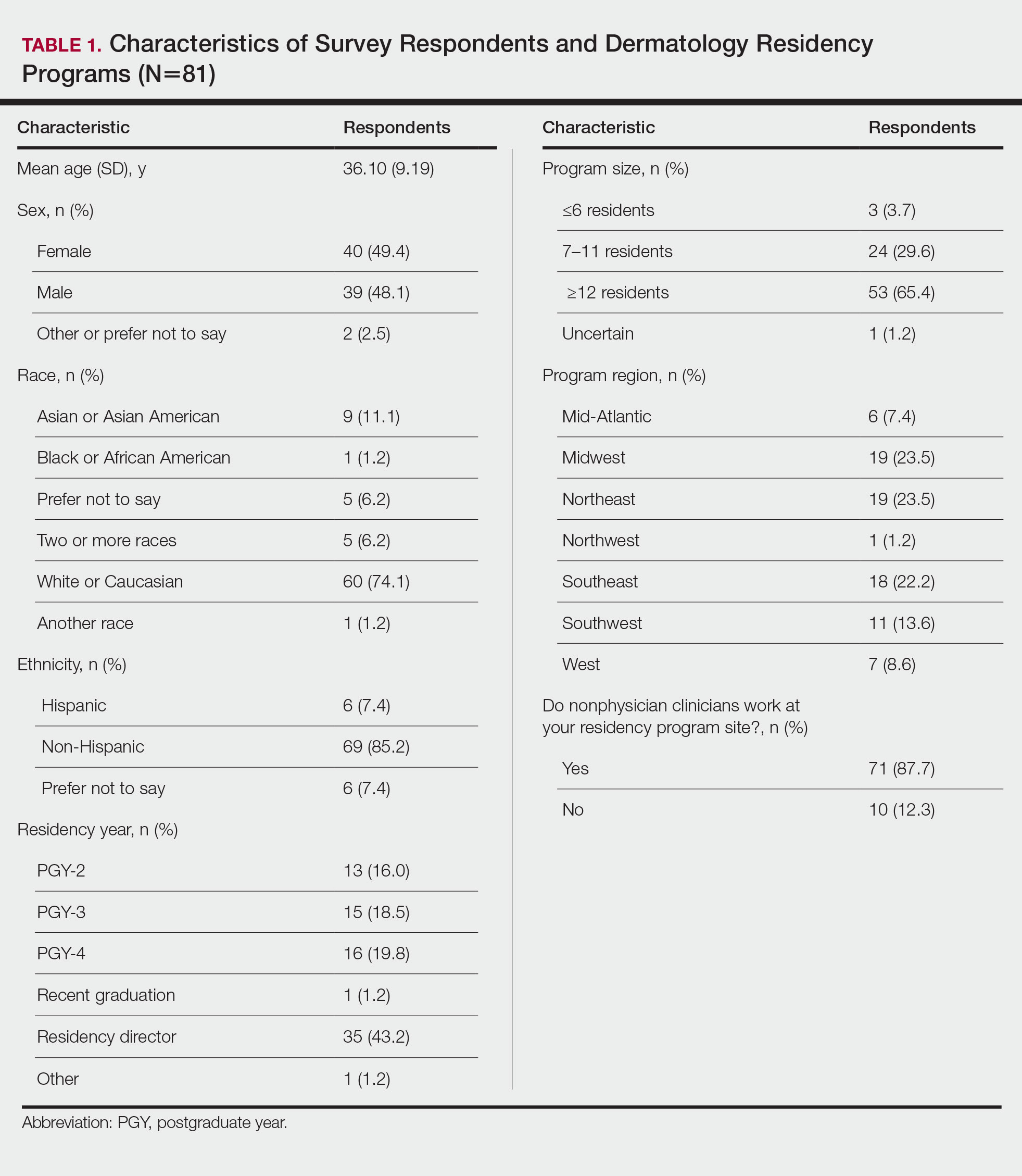

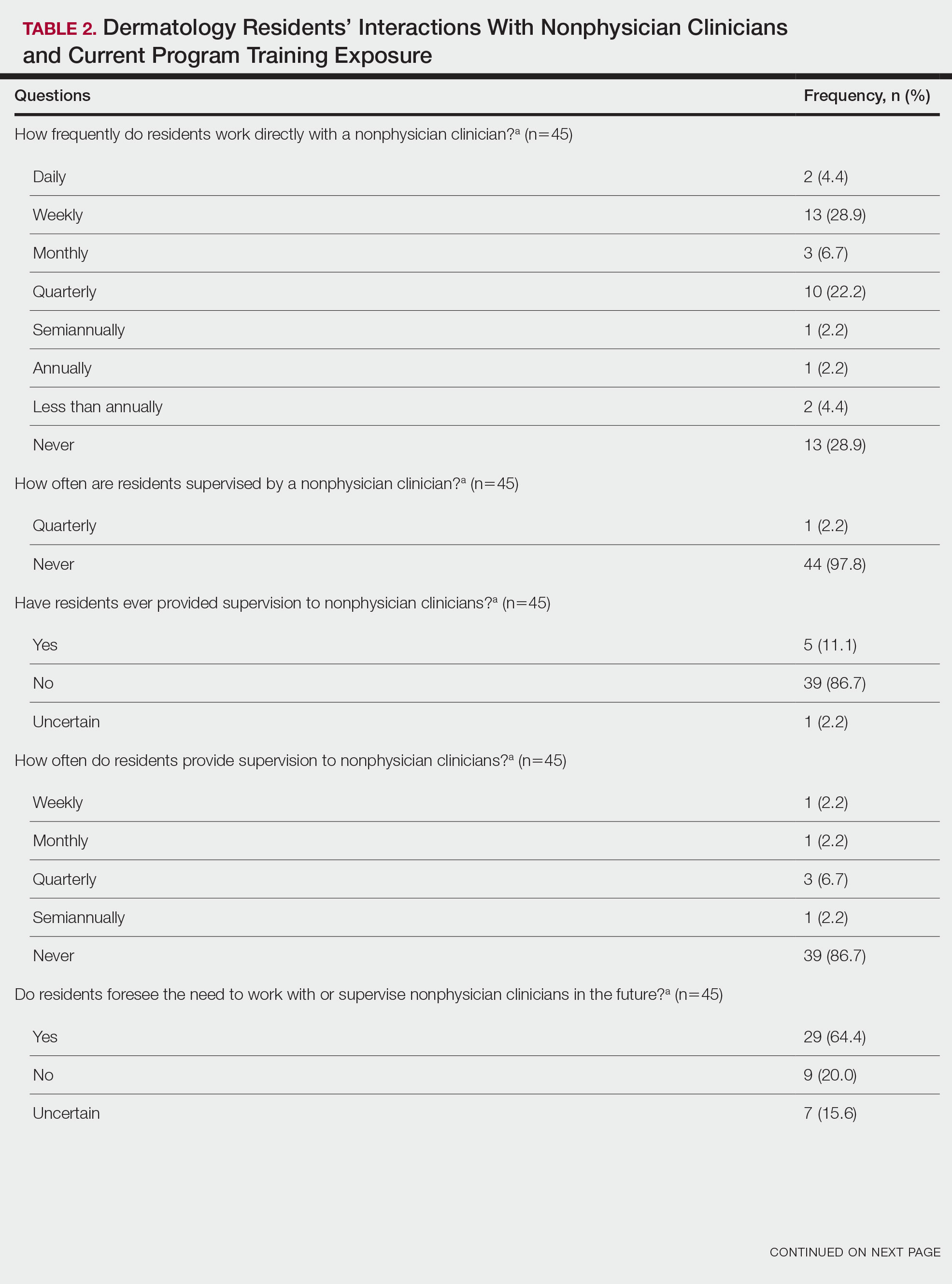

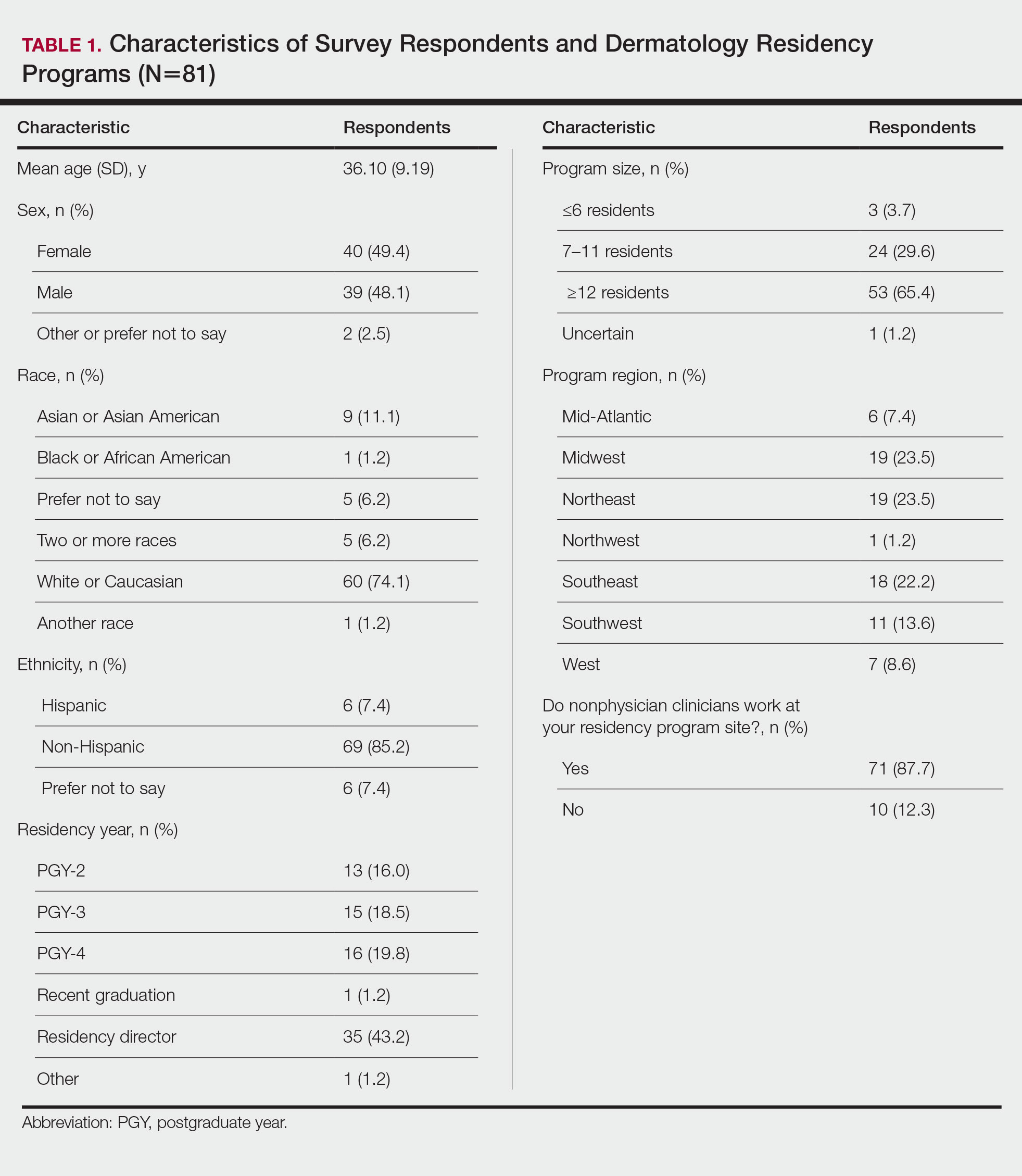

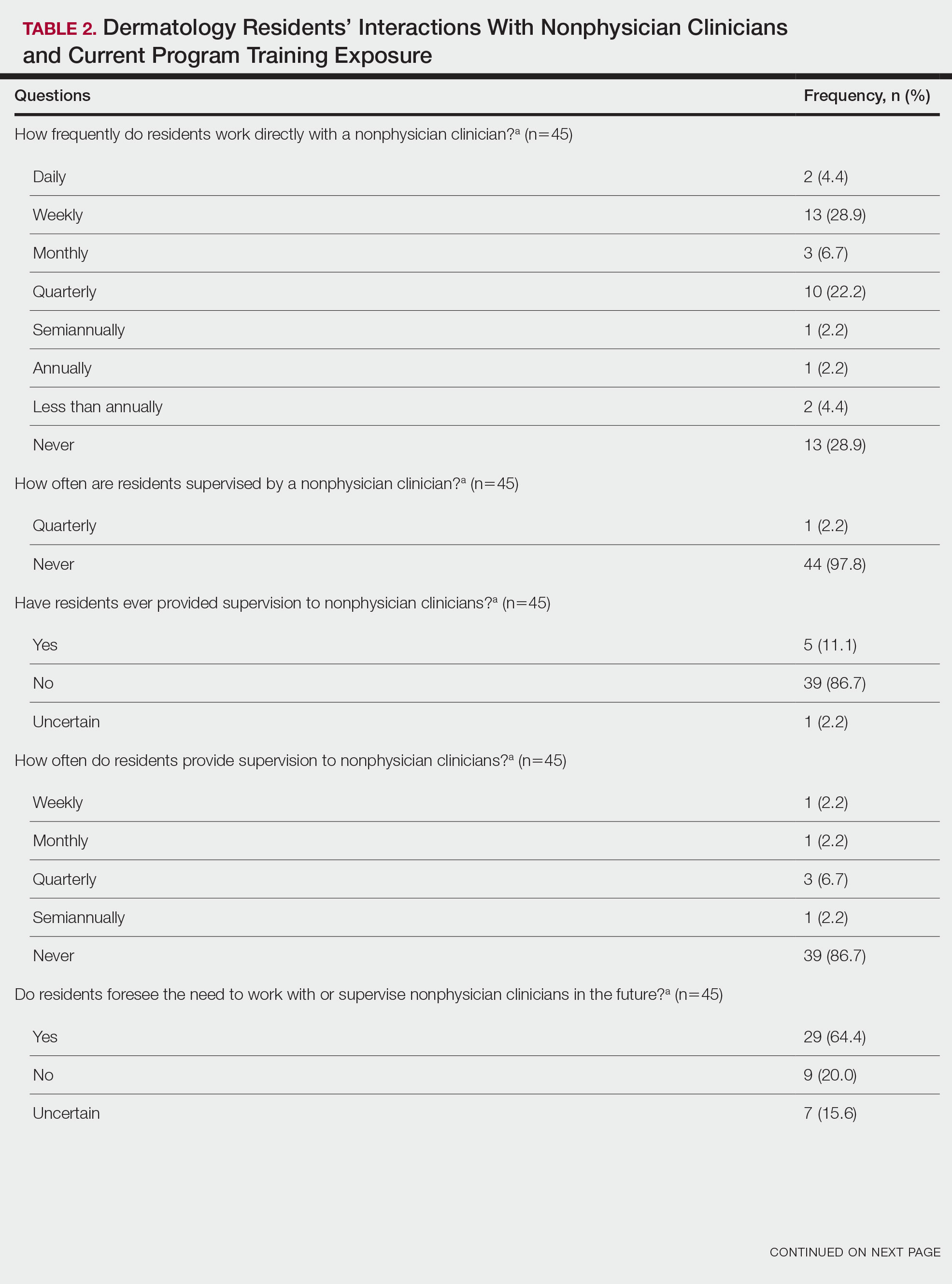

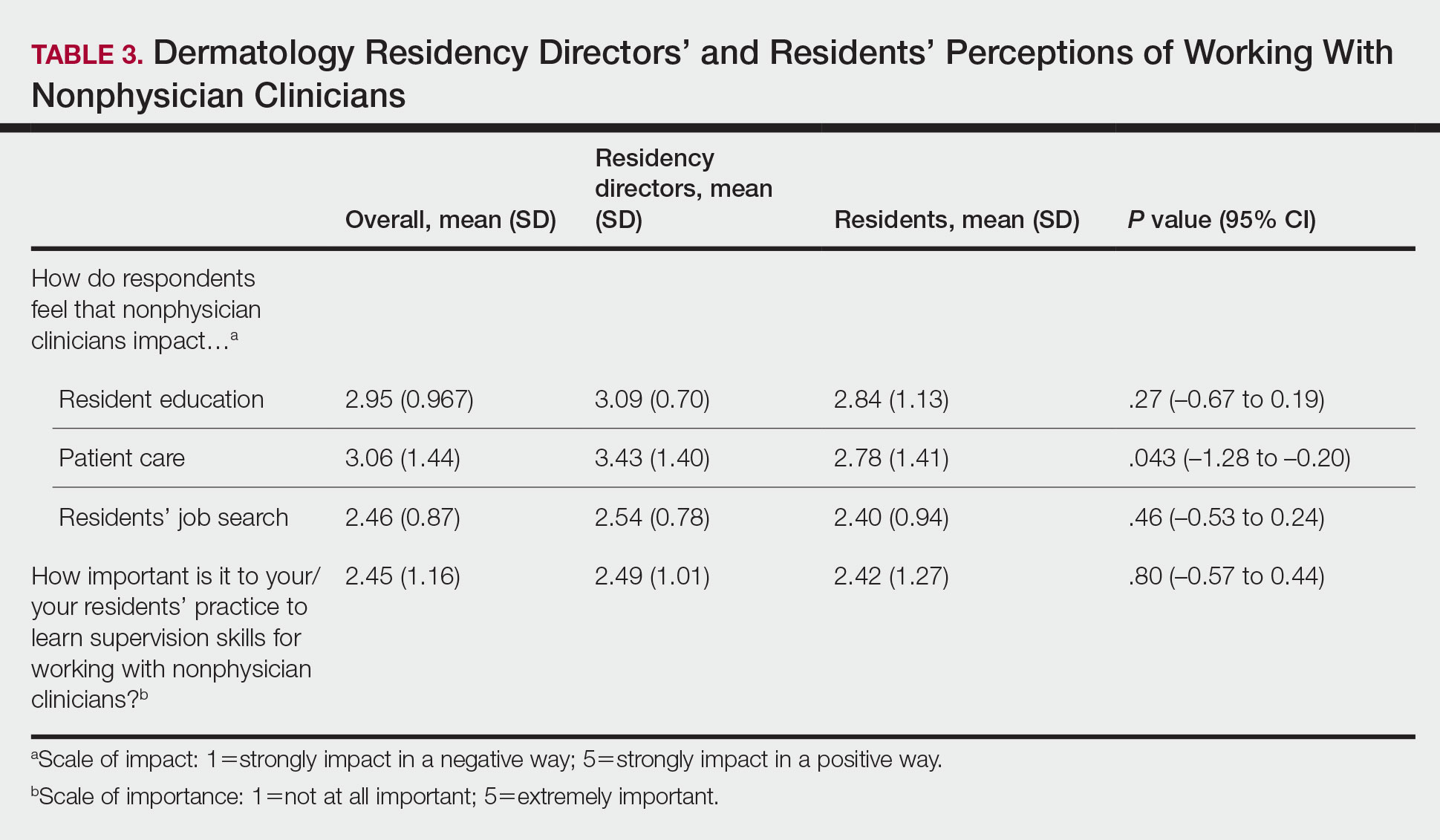

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

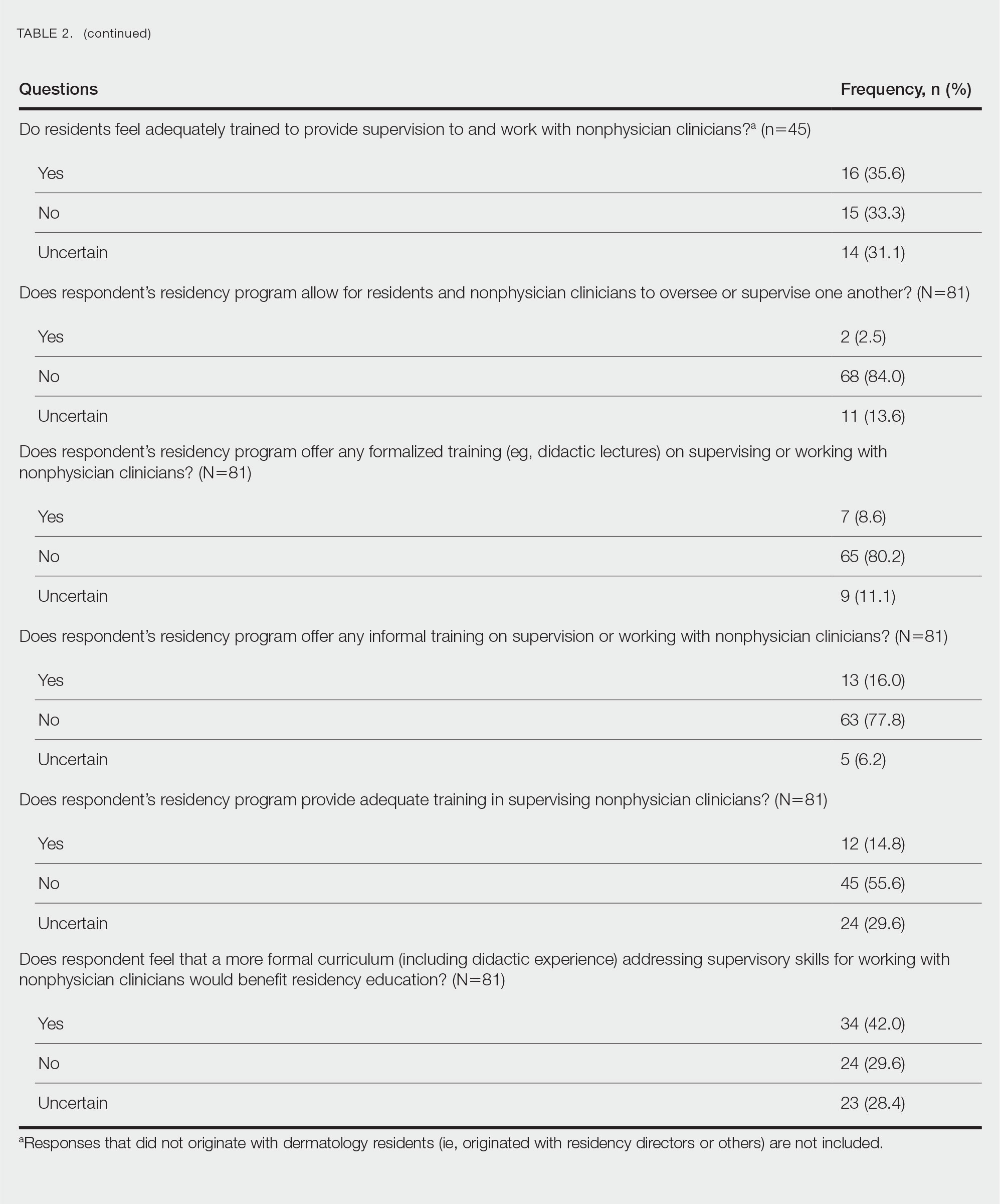

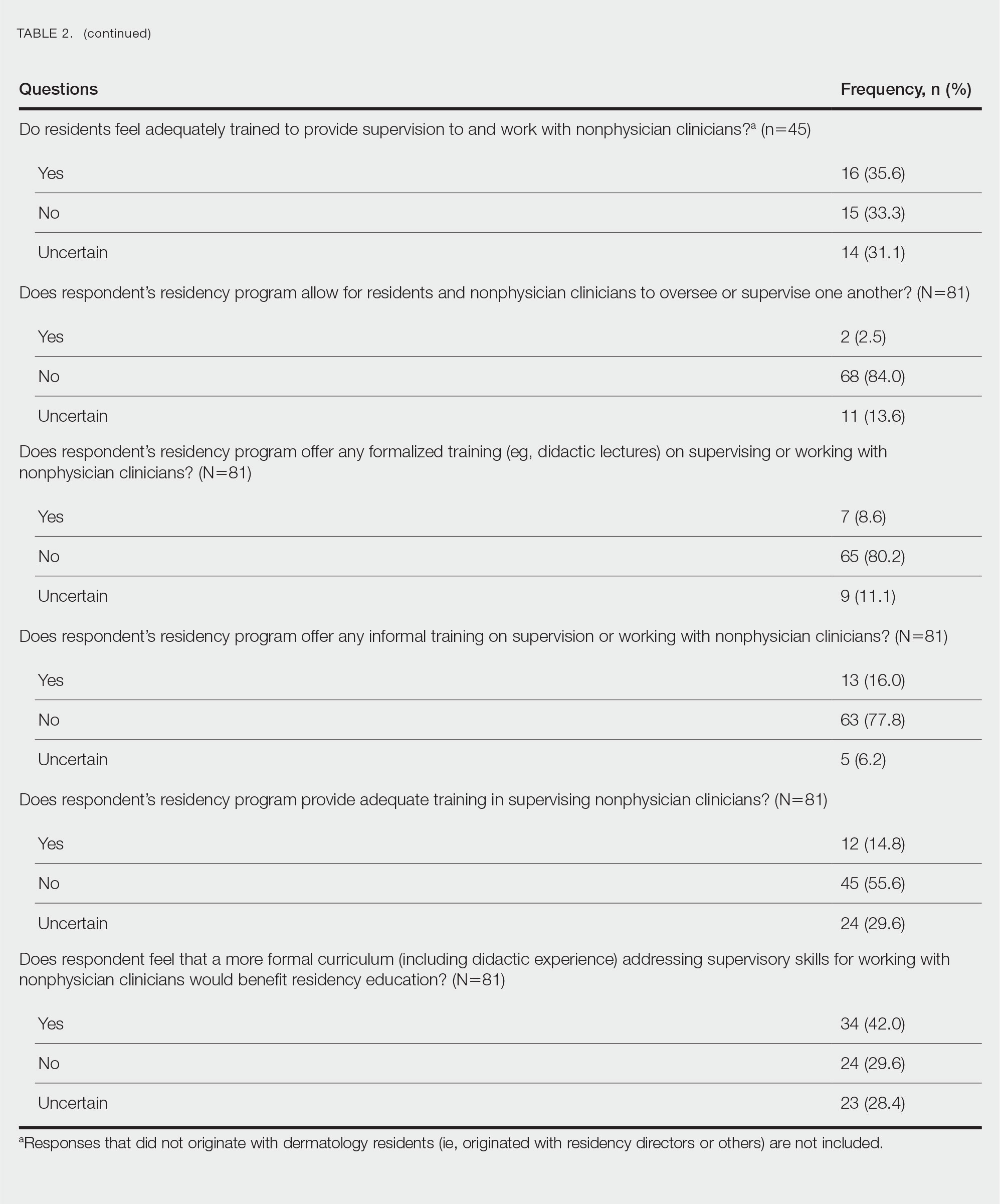

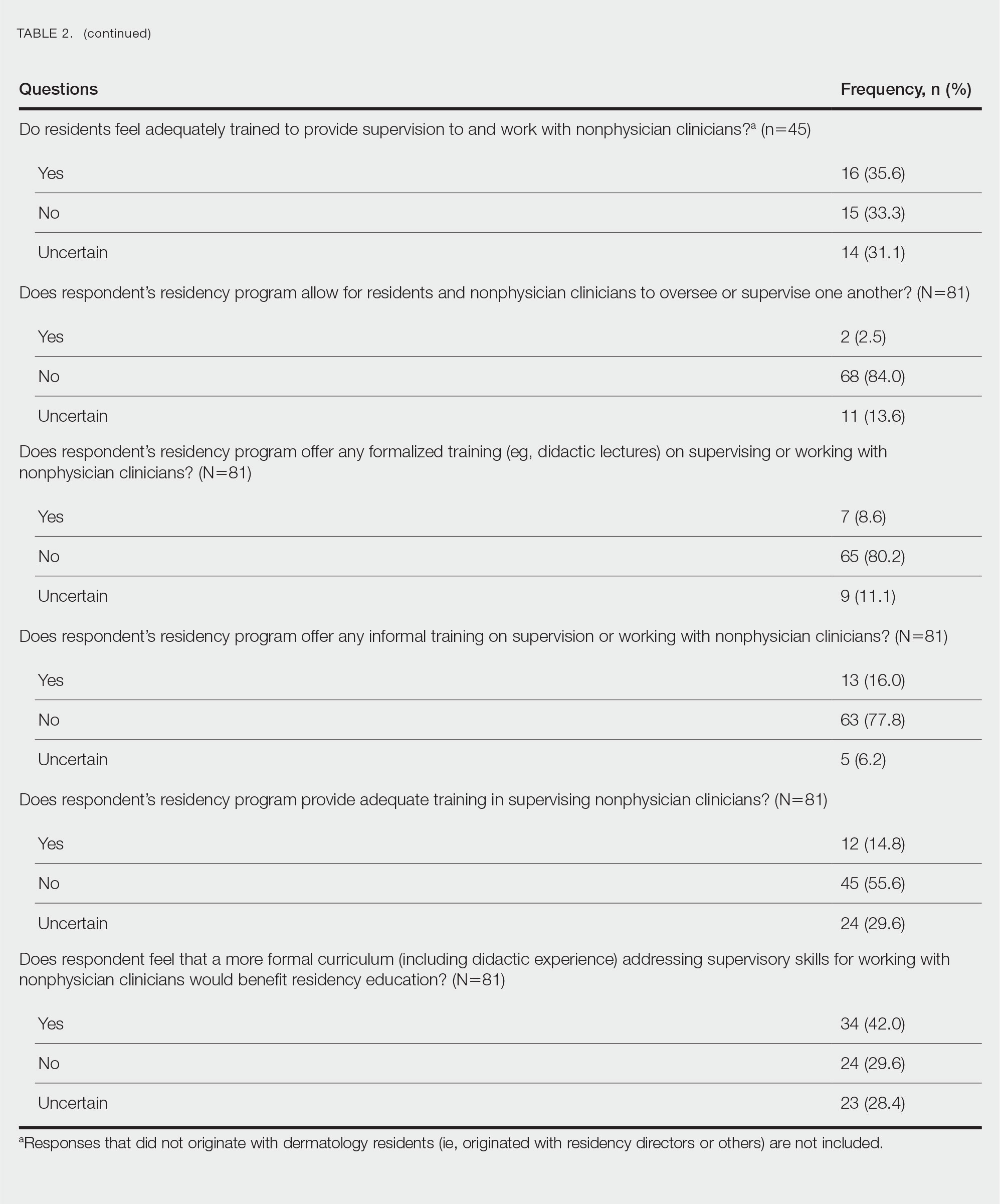

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

Practice Points

- Most dermatology residency programs do not offer training on working with and supervising nonphysician clinicians.

- Dermatology residents think that formal training in supervising nonphysician clinicians would be a beneficial addition to the residency curriculum.

Native American Life Expectancy Dropped Dramatically During Pandemic

During the pandemic, Native Americans’ life expectancy dropped more than in any other racial or ethnic group. Essentially, they lost nearly 5 years. And they already had the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group.

Researchers from the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Urban Institute, and Virginia Commonwealth University compared life expectancy changes during 2019-2021 in the United States and 21 peer countries. The study is the first to estimate such changes in non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian populations. The researchers were taken aback by their findings.

In those 2 years, Americans overall saw a net loss of 2.41 years: Life expectancy declined from 78.85 years in 2019 to 76.98 years in 2020 and 76.44 in 2021. Surprisingly, peer countries not only saw a much smaller loss (0.55 year), but actually had an increase of 0.26 year between 2020 and 2021. The US decline was 8.5 times greater than that of the average decline among 16 other high-income countries during the same period. “It’s like nothing we have seen since World War II,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, one of the coauthors of the study.

The decrease in life expectancy—or, put another way, mortality—was “highly racialized” in the United States, the researchers say. The largest drops in 2020 were among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (4.48 years), Hispanic (3.72 years), non-Hispanic Black (3.20 years), and non-Hispanic Asian (1.83 years) populations. In 2021, the largest decreases were in the non-Hispanic White population. The reasons for the “surprising crossover” in outcomes are not entirely clear, the researchers say, and likely have multiple explanations.

However, the patterns, they note, “reflect a long history of systemic racism” and “inadequacies in how the pandemic was managed in the United States.” In a university news release, study coauthor Ryan Masters, PhD, said, “The US didn’t take COVID seriously to the extent that other countries did, and we paid a horrific price for it, with Black and brown people suffering the most.”

The researchers expected to see a decline among Native Americans, Masters said, because they often lack access to vaccines, quality health care, and transportation. But the magnitude of the drop in life expectancy was “shocking.” He added, “You just don’t see numbers like this in advanced countries in the modern day.”

Noting that the troubling downward trend in life expectancy had been on view even before the pandemic, Masters said, “This isn’t just a COVID problem. There are broader social and economic policies that placed the United States at a disadvantage long before this pandemic. The time to address them is long overdue.”

During the pandemic, Native Americans’ life expectancy dropped more than in any other racial or ethnic group. Essentially, they lost nearly 5 years. And they already had the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group.

Researchers from the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Urban Institute, and Virginia Commonwealth University compared life expectancy changes during 2019-2021 in the United States and 21 peer countries. The study is the first to estimate such changes in non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian populations. The researchers were taken aback by their findings.

In those 2 years, Americans overall saw a net loss of 2.41 years: Life expectancy declined from 78.85 years in 2019 to 76.98 years in 2020 and 76.44 in 2021. Surprisingly, peer countries not only saw a much smaller loss (0.55 year), but actually had an increase of 0.26 year between 2020 and 2021. The US decline was 8.5 times greater than that of the average decline among 16 other high-income countries during the same period. “It’s like nothing we have seen since World War II,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, one of the coauthors of the study.

The decrease in life expectancy—or, put another way, mortality—was “highly racialized” in the United States, the researchers say. The largest drops in 2020 were among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (4.48 years), Hispanic (3.72 years), non-Hispanic Black (3.20 years), and non-Hispanic Asian (1.83 years) populations. In 2021, the largest decreases were in the non-Hispanic White population. The reasons for the “surprising crossover” in outcomes are not entirely clear, the researchers say, and likely have multiple explanations.

However, the patterns, they note, “reflect a long history of systemic racism” and “inadequacies in how the pandemic was managed in the United States.” In a university news release, study coauthor Ryan Masters, PhD, said, “The US didn’t take COVID seriously to the extent that other countries did, and we paid a horrific price for it, with Black and brown people suffering the most.”

The researchers expected to see a decline among Native Americans, Masters said, because they often lack access to vaccines, quality health care, and transportation. But the magnitude of the drop in life expectancy was “shocking.” He added, “You just don’t see numbers like this in advanced countries in the modern day.”

Noting that the troubling downward trend in life expectancy had been on view even before the pandemic, Masters said, “This isn’t just a COVID problem. There are broader social and economic policies that placed the United States at a disadvantage long before this pandemic. The time to address them is long overdue.”

During the pandemic, Native Americans’ life expectancy dropped more than in any other racial or ethnic group. Essentially, they lost nearly 5 years. And they already had the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group.

Researchers from the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Urban Institute, and Virginia Commonwealth University compared life expectancy changes during 2019-2021 in the United States and 21 peer countries. The study is the first to estimate such changes in non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian populations. The researchers were taken aback by their findings.

In those 2 years, Americans overall saw a net loss of 2.41 years: Life expectancy declined from 78.85 years in 2019 to 76.98 years in 2020 and 76.44 in 2021. Surprisingly, peer countries not only saw a much smaller loss (0.55 year), but actually had an increase of 0.26 year between 2020 and 2021. The US decline was 8.5 times greater than that of the average decline among 16 other high-income countries during the same period. “It’s like nothing we have seen since World War II,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, one of the coauthors of the study.

The decrease in life expectancy—or, put another way, mortality—was “highly racialized” in the United States, the researchers say. The largest drops in 2020 were among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (4.48 years), Hispanic (3.72 years), non-Hispanic Black (3.20 years), and non-Hispanic Asian (1.83 years) populations. In 2021, the largest decreases were in the non-Hispanic White population. The reasons for the “surprising crossover” in outcomes are not entirely clear, the researchers say, and likely have multiple explanations.

However, the patterns, they note, “reflect a long history of systemic racism” and “inadequacies in how the pandemic was managed in the United States.” In a university news release, study coauthor Ryan Masters, PhD, said, “The US didn’t take COVID seriously to the extent that other countries did, and we paid a horrific price for it, with Black and brown people suffering the most.”

The researchers expected to see a decline among Native Americans, Masters said, because they often lack access to vaccines, quality health care, and transportation. But the magnitude of the drop in life expectancy was “shocking.” He added, “You just don’t see numbers like this in advanced countries in the modern day.”

Noting that the troubling downward trend in life expectancy had been on view even before the pandemic, Masters said, “This isn’t just a COVID problem. There are broader social and economic policies that placed the United States at a disadvantage long before this pandemic. The time to address them is long overdue.”

Multiple Fingerlike Projections on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

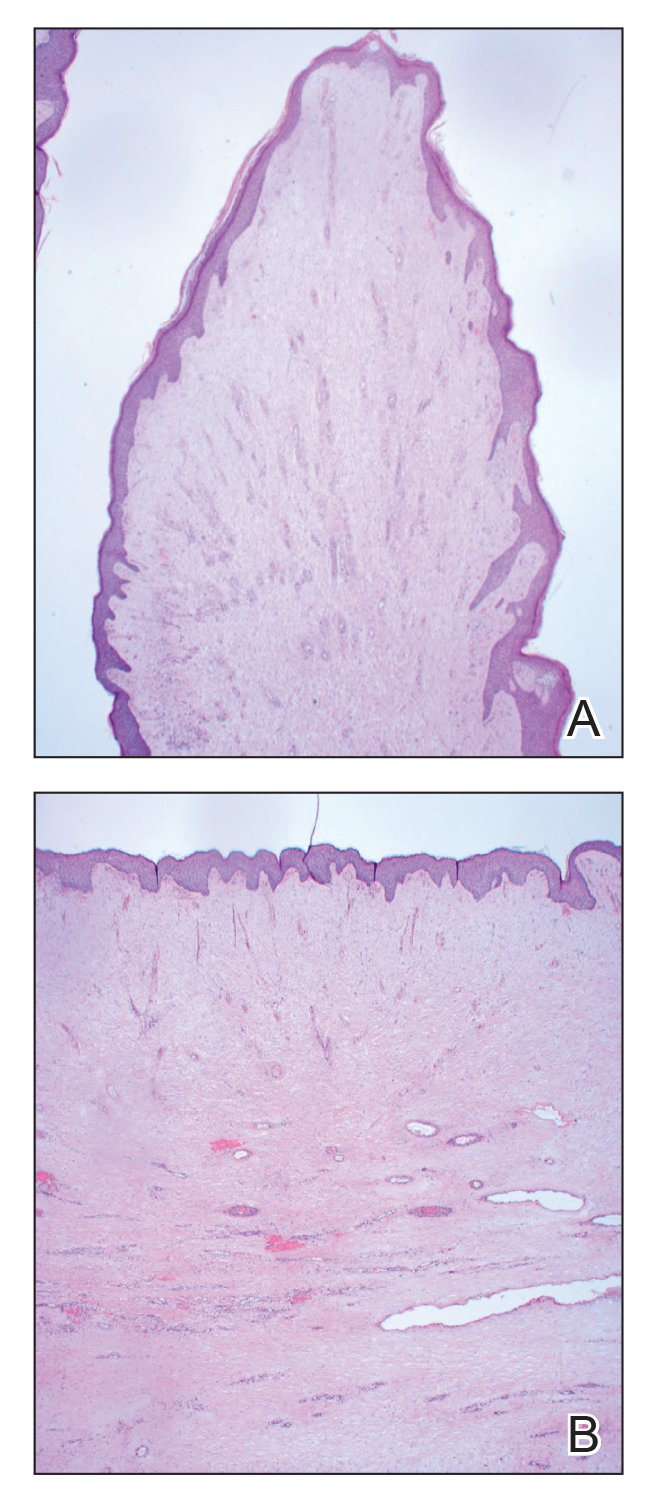

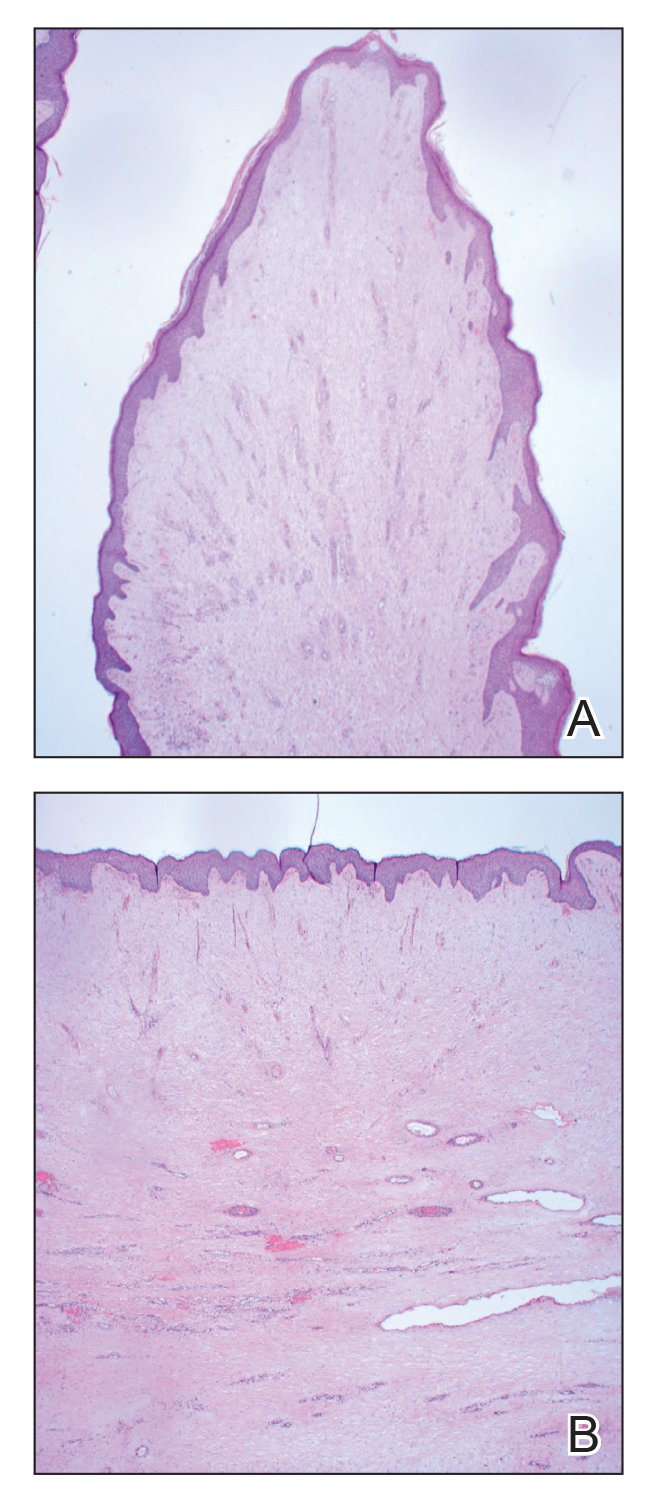

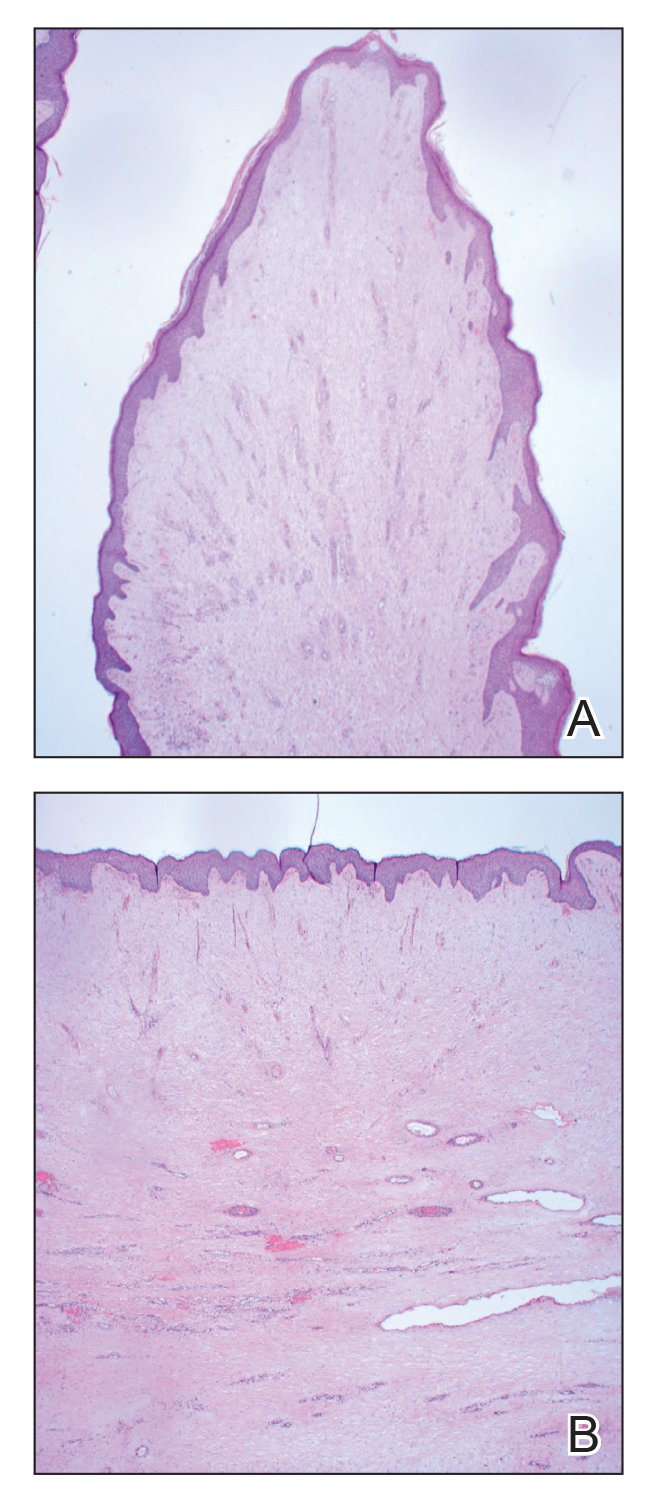

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

A 61-year-old man presented with painful skin growths on the right pretibial region of several months’ duration. The patient reported pain due to friction between the lesions and underlying skin, leading to erosions. His medical history was remarkable for morbid obesity (body mass index of 62), chronic venous stasis, and chronic lymphedema. The patient was followed for wound care of venous stasis ulcers. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple 5- to 30-mm, flesh-colored, fingerlike projections on the right tibial region. A biopsy was obtained and submitted for histopathologic analysis.

SCLC Treatment

Psoriatic Arthritis Medications

A Special Supplement on Hot Topics in Primary Care 2022

Hot Topics in Primary Care 2022 is a resource that explores the newest developments in primary care topics that impact your daily clinical practice.

Click on the link below to access the entire supplement. You can also click on the video panes below to view brief summaries of individual chapters. Titles above the video panes link directly to each article.

- A Paradigm Shift for Asthma Care

- Common Questions on Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Primary Care

- Detecting and Managing ASCVD in Women: A Focus on Statins

- Improving Detection and Management of Anemia in CKD

- OTC Analgesics vs Opioids for Pain Management

- Practical Considerations for Use of Insulin/Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Combinations in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes

- Practical Screening for Islet Autoantibodies: The Time Has Come

- Reducing Thrombotic Risk From Polyvascular Disease in Primary Care

- Strategies to Improve Outcomes in COPD

- The Evolving Landscape of ASCVD Risk Among Patients With HIV

- The New Face of Preadolescent and Adolescent Acne: Beyond the Guidelines

- The Role of Eggs in Healthy Diets

- Update on the Gut Microbiome for the Primary Care Clinician

- Updates in the Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease

- Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 4 continuing medical education (CME) credits. Credit is awarded for successful completion of the evaluation after reading the article. The links can be found within the supplement on the first page of each article where CME credits are offered.

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care 2022

This supplement to The Journal of Family Practice was sponsored by the Primary Care Education Consortium and Primary Care Metabolic Group.

Check out these short video segments, which were prepared by the supplement authors and summarize the individual articles.

The title above each video links to the related article.

A Paradigm Shift for Asthma Care, Njira Lugogo, MD; Neil Skolnik, MD; Yihui Jiang, DO

Common Questions on Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Primary Care, Eden M. Miller, DO

Detecting and Managing ASCVD in Women: A Focus on Statins, Pam Kushner, MD

Improving Detection and Management of Anemia in CKD, Steven Fishbane, MD; Stephen Brunton, MD, FAAFP

OTC Analgesics vs Opioids for Pain Management, Gary M. Ruoff, MD

Practical Screening for Islet Autoantibodies: The Time Has Come, Timothy Reid, MD

Reducing Thrombotic Risk From Polyvascular Disease in Primary Care, Stephen Brunton, MD, FAAFP

Strategies to Improve Outcomes in COPD, Barbara Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP

The Evolving Landscape of ASCVD Risk Among Patients With HIV, Carlos Malvestutto, MD, MPH

The Role of Eggs in Healthy Diets, Maria Luz Fernandez, PhD

Update on the Gut Microbiome for the Primary Care Clinician, Eden M. Miller, DO

Updates in the Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease, Gary Small, MD

Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care, George Bakris, MD

Hot Topics in Primary Care 2022 is a resource that explores the newest developments in primary care topics that impact your daily clinical practice.

Click on the link below to access the entire supplement. You can also click on the video panes below to view brief summaries of individual chapters. Titles above the video panes link directly to each article.

- A Paradigm Shift for Asthma Care

- Common Questions on Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Primary Care

- Detecting and Managing ASCVD in Women: A Focus on Statins

- Improving Detection and Management of Anemia in CKD

- OTC Analgesics vs Opioids for Pain Management

- Practical Considerations for Use of Insulin/Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Combinations in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes

- Practical Screening for Islet Autoantibodies: The Time Has Come

- Reducing Thrombotic Risk From Polyvascular Disease in Primary Care

- Strategies to Improve Outcomes in COPD

- The Evolving Landscape of ASCVD Risk Among Patients With HIV

- The New Face of Preadolescent and Adolescent Acne: Beyond the Guidelines

- The Role of Eggs in Healthy Diets

- Update on the Gut Microbiome for the Primary Care Clinician

- Updates in the Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease

- Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 4 continuing medical education (CME) credits. Credit is awarded for successful completion of the evaluation after reading the article. The links can be found within the supplement on the first page of each article where CME credits are offered.

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care 2022

This supplement to The Journal of Family Practice was sponsored by the Primary Care Education Consortium and Primary Care Metabolic Group.

Check out these short video segments, which were prepared by the supplement authors and summarize the individual articles.

The title above each video links to the related article.

A Paradigm Shift for Asthma Care, Njira Lugogo, MD; Neil Skolnik, MD; Yihui Jiang, DO

Common Questions on Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Primary Care, Eden M. Miller, DO

Detecting and Managing ASCVD in Women: A Focus on Statins, Pam Kushner, MD

Improving Detection and Management of Anemia in CKD, Steven Fishbane, MD; Stephen Brunton, MD, FAAFP

OTC Analgesics vs Opioids for Pain Management, Gary M. Ruoff, MD

Practical Screening for Islet Autoantibodies: The Time Has Come, Timothy Reid, MD

Reducing Thrombotic Risk From Polyvascular Disease in Primary Care, Stephen Brunton, MD, FAAFP

Strategies to Improve Outcomes in COPD, Barbara Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP

The Evolving Landscape of ASCVD Risk Among Patients With HIV, Carlos Malvestutto, MD, MPH

The Role of Eggs in Healthy Diets, Maria Luz Fernandez, PhD

Update on the Gut Microbiome for the Primary Care Clinician, Eden M. Miller, DO

Updates in the Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease, Gary Small, MD

Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care, George Bakris, MD

Hot Topics in Primary Care 2022 is a resource that explores the newest developments in primary care topics that impact your daily clinical practice.

Click on the link below to access the entire supplement. You can also click on the video panes below to view brief summaries of individual chapters. Titles above the video panes link directly to each article.

- A Paradigm Shift for Asthma Care

- Common Questions on Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Primary Care

- Detecting and Managing ASCVD in Women: A Focus on Statins

- Improving Detection and Management of Anemia in CKD

- OTC Analgesics vs Opioids for Pain Management

- Practical Considerations for Use of Insulin/Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Combinations in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes

- Practical Screening for Islet Autoantibodies: The Time Has Come

- Reducing Thrombotic Risk From Polyvascular Disease in Primary Care

- Strategies to Improve Outcomes in COPD

- The Evolving Landscape of ASCVD Risk Among Patients With HIV

- The New Face of Preadolescent and Adolescent Acne: Beyond the Guidelines

- The Role of Eggs in Healthy Diets

- Update on the Gut Microbiome for the Primary Care Clinician

- Updates in the Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease

- Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 4 continuing medical education (CME) credits. Credit is awarded for successful completion of the evaluation after reading the article. The links can be found within the supplement on the first page of each article where CME credits are offered.

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care 2022

This supplement to The Journal of Family Practice was sponsored by the Primary Care Education Consortium and Primary Care Metabolic Group.

Check out these short video segments, which were prepared by the supplement authors and summarize the individual articles.

The title above each video links to the related article.

A Paradigm Shift for Asthma Care, Njira Lugogo, MD; Neil Skolnik, MD; Yihui Jiang, DO

Common Questions on Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Primary Care, Eden M. Miller, DO

Detecting and Managing ASCVD in Women: A Focus on Statins, Pam Kushner, MD

Improving Detection and Management of Anemia in CKD, Steven Fishbane, MD; Stephen Brunton, MD, FAAFP

OTC Analgesics vs Opioids for Pain Management, Gary M. Ruoff, MD

Practical Screening for Islet Autoantibodies: The Time Has Come, Timothy Reid, MD

Reducing Thrombotic Risk From Polyvascular Disease in Primary Care, Stephen Brunton, MD, FAAFP

Strategies to Improve Outcomes in COPD, Barbara Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP

The Evolving Landscape of ASCVD Risk Among Patients With HIV, Carlos Malvestutto, MD, MPH

The Role of Eggs in Healthy Diets, Maria Luz Fernandez, PhD

Update on the Gut Microbiome for the Primary Care Clinician, Eden M. Miller, DO

Updates in the Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease, Gary Small, MD

Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care, George Bakris, MD

The Team Approach to Managing Type 2 Diabetes

Those of us who treat patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) daily have long recognized a disturbing irony: diabetes is a disease whose management requires consistency in approach and constancy in delivery, but it is most prevalent among those whose lives often allow little to no time for either.

In our clinic, many patients with diabetes are struggling, in some way, to incorporate diabetes management into their daily lives. They are juggling multiple jobs and family responsibilities; they are working jobs with inconsistent access to food or refrigeration (such as farming, service industry work, and others); and many—even those with insurance—are struggling to afford their insulin and non insulin medications, insulin administration supplies, and glucose testing equipment.

Studies show how stress deleteriously affects this disease. The body does not deal well with these frequent and persistent stressors; higher cortisol levels result in higher blood glucose levels, increased systemic inflammation, and other drivers of both diabetes and its complications; all have been extensively documented.

What has been frustrating for our clinical community is knowing that since the early 2000s, new diabetes medications and technologies have been available that can make a difference in our patients’ lives, but for various reasons, they have not been well adopted, particularly among patients most likely to benefit from them. Consequently, we have not consistently seen meaningfully reduced glycated hemoglobin (A1c) levels or reduced rates of acute or chronic diabetes complications. Therapeutic inertia exists at the patient, systemic, and physician levels.

Many of the new glucose-lowering medications can also improve cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes with low risk for hypoglycemia and weight gain. Diabetes technologies like insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors (CGM) have been demonstrated in clinical trials to improve A1c and reduce hypoglycemia risk. But the reality is that clinicians are seeing an increasing number of patients with high A1c, with hypoglycemia, with severe hyperglycemia, and with long-term diabetes complications.

If these advancements are supposed to improve health outcomes, why are patient, community, and population health not improving? Why are some patients not receiving the care they need, while others get extra services that do not improve their health and may even harm them?

These advancements also create new questions for clinicians. At what point in the disease course should existing medications be ramped up, ramped down, or changed? Which patient characteristics or comorbidities allow or do not allow these changes? When should we use technologies or when does their burden outweigh their potential benefits? What resources and support systems do our patients need to live well with their disease and how can these be procured?