User login

Commentary: Treating Chronic Migraine and Providing Temporary Relief, July 2022

Many of our patients with refractory migraine do not respond to first-line acute or preventive treatments, and, almost by definition, first- and second-line treatments have failed in the majority of patients on calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist medications. Three studies this month highlight the efficacy of CGRP monoclonal antibody (mAb) and small-molecule medications in this population specifically.

Most headache specialists are familiar with the "standard" or PREEMPT onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) paradigm used preventively for migraine. This protocol uses 155 units of onabotulinumtoxinA over 31 sites in seven muscle groups. OnabotulinumtoxinA vials typically come in 100 or 200 units, and when preparing onabotulinumtoxinA for patients who are being injected most providers are forced to discard most or all of the remaining 45 units. Anecdotally, some providers do inject the entire 200-unit vial, and the additional injection sites are either given in another standard protocol or in a follow-the-pain manner.

The study by Zandieh and colleagues followed 175 patients with chronic migraine who first received three injections of 150 units of onabotulinumtoxinA, then three injections of 200 units of this agent. The additional 50 units were injected into the temporalis and occipitalis muscles — the standard sites were used, but additional units were injected into each of the sites. The majority of patients experienced primarily frontal pain; the injections were not given in specific areas where more pain was manifesting.

The average number of headache days per month decreased significantly when the onabotulinumtoxinA dose was increased; patients tolerated the medication over the 3-month period as well. In practice, many providers use the additional units of onabotulinumtoxinA. This study argues that there is a minimal risk, and probably a potential significant benefit, when using up to 200 units every 3 months. Providers should, however, be aware that in rare instances, some insurances will only cover a 155-unit injection, and the use of additional units may jeopardize reimbursement for those plans.

Many patients anecdotally will use cold or heat as a treatment for acute migraine pain; however, the topical use of temperature has not been well studied for this purpose. Cold stimulus has, importantly, been known to be a trigger of migraine as well as other headache disorders classified in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD-3), including external cold stimulus headache and "brain freeze" or internal cold stimulus headache. Hsu and colleagues produced a meta-analysis and systematic review on the use of cold for acute treatment of migraine.

Six studies were found to be eligible for this review. The cold stimulus could be placed anywhere on the head, and the studies could have considered its use for any migraine-associated symptom. This includes headache, eye pain, nausea, or vomiting. The interventions used cold somewhat differently, including as ice packing, cooling compression, soaking, and as a rinse. Both randomized and nonrandomized trials were included in the systematic review; however, only randomized controlled trials were used for the meta-analysis.

The primary outcome evaluated by the authors was pain intensity; secondary outcomes were duration of migraine pain as well as associated symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting). The meta-analysis revealed that cold interventions reduce migraine pain by 3.21 points on an analog scale, and this was found to be effective within 30 minutes. At 1-2 hours after the intervention, the effect was not seen to be significant. At 24 hours, the effect of cold intervention was marginal. Cold was not seen to significantly reduce nausea or vomiting at 2 hours after intervention.

Although cold treatments are commonly used by patients, there appears to be benefit only early in the onset of a migraine attack. Headache specialists typically recommend early treatment with a migraine-specific acute medication; however, the medication may take minutes to hours before taking effect. Cold can be recommended to patients during that intervening period, and it may help until the time that their acute medications take effect.

Chronic refractory migraine remains one of the most debilitating neurologic disorders and is a challenge even for the best trained neurologist or headache specialist. There are few headache centers with inpatient headache units around the United States, and those that remain use treatments that most neurologists are not familiar with. Schwenk and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the data of a major academic headache center and revealed impressive outcomes in this very difficult-to-treat population.

This study reviewed the outcomes of 609 consecutive patients admitted to the Thomas Jefferson University inpatient headache unit from 2017 to 2021. These patients all received continuous lidocaine infusions that were titrated according to an internal protocol that balanced daily plasma lidocaine levels, tolerability, and pain relief. Hospital discharge occurred when patients were pain-free for 12-24 hours or had a minimal response after 5 days of treatment. All patients had at least eight severe headaches per month for at least 6 consecutive months and had tried one to seven preventive medications, with the result of either intolerance or ineffectiveness.

The primary outcome was change from baseline to discharge pain level. Patients were admitted with an average score of 7.0 of 10 on admission and were discharged at a score of 1.0 of 10. Secondary outcomes were average pain at post-discharge appointment vs baseline (5.5 vs 7.0), number of monthly headache days at post-discharge appointment (22.5 vs 26.8), and current and average pain levels at the post-discharge appointment, which were both significantly lower as well. The most common adverse effect was nausea; others noted were cardiovascular changes, hallucinations or nightmares, sedation, anxiety, and chest pain.

This is an important retrospective on the effectiveness of an inpatient lidocaine protocol for refractory chronic migraine. When considering this population, especially if multiple lines of preventive and acute medications are not effective, referral to an academic inpatient headache center should definitely be considered. This patient population does not respond effectively to most treatment modalities, and this is cause to give them hope.

Many of our patients with refractory migraine do not respond to first-line acute or preventive treatments, and, almost by definition, first- and second-line treatments have failed in the majority of patients on calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist medications. Three studies this month highlight the efficacy of CGRP monoclonal antibody (mAb) and small-molecule medications in this population specifically.

Most headache specialists are familiar with the "standard" or PREEMPT onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) paradigm used preventively for migraine. This protocol uses 155 units of onabotulinumtoxinA over 31 sites in seven muscle groups. OnabotulinumtoxinA vials typically come in 100 or 200 units, and when preparing onabotulinumtoxinA for patients who are being injected most providers are forced to discard most or all of the remaining 45 units. Anecdotally, some providers do inject the entire 200-unit vial, and the additional injection sites are either given in another standard protocol or in a follow-the-pain manner.

The study by Zandieh and colleagues followed 175 patients with chronic migraine who first received three injections of 150 units of onabotulinumtoxinA, then three injections of 200 units of this agent. The additional 50 units were injected into the temporalis and occipitalis muscles — the standard sites were used, but additional units were injected into each of the sites. The majority of patients experienced primarily frontal pain; the injections were not given in specific areas where more pain was manifesting.

The average number of headache days per month decreased significantly when the onabotulinumtoxinA dose was increased; patients tolerated the medication over the 3-month period as well. In practice, many providers use the additional units of onabotulinumtoxinA. This study argues that there is a minimal risk, and probably a potential significant benefit, when using up to 200 units every 3 months. Providers should, however, be aware that in rare instances, some insurances will only cover a 155-unit injection, and the use of additional units may jeopardize reimbursement for those plans.

Many patients anecdotally will use cold or heat as a treatment for acute migraine pain; however, the topical use of temperature has not been well studied for this purpose. Cold stimulus has, importantly, been known to be a trigger of migraine as well as other headache disorders classified in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD-3), including external cold stimulus headache and "brain freeze" or internal cold stimulus headache. Hsu and colleagues produced a meta-analysis and systematic review on the use of cold for acute treatment of migraine.

Six studies were found to be eligible for this review. The cold stimulus could be placed anywhere on the head, and the studies could have considered its use for any migraine-associated symptom. This includes headache, eye pain, nausea, or vomiting. The interventions used cold somewhat differently, including as ice packing, cooling compression, soaking, and as a rinse. Both randomized and nonrandomized trials were included in the systematic review; however, only randomized controlled trials were used for the meta-analysis.

The primary outcome evaluated by the authors was pain intensity; secondary outcomes were duration of migraine pain as well as associated symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting). The meta-analysis revealed that cold interventions reduce migraine pain by 3.21 points on an analog scale, and this was found to be effective within 30 minutes. At 1-2 hours after the intervention, the effect was not seen to be significant. At 24 hours, the effect of cold intervention was marginal. Cold was not seen to significantly reduce nausea or vomiting at 2 hours after intervention.

Although cold treatments are commonly used by patients, there appears to be benefit only early in the onset of a migraine attack. Headache specialists typically recommend early treatment with a migraine-specific acute medication; however, the medication may take minutes to hours before taking effect. Cold can be recommended to patients during that intervening period, and it may help until the time that their acute medications take effect.

Chronic refractory migraine remains one of the most debilitating neurologic disorders and is a challenge even for the best trained neurologist or headache specialist. There are few headache centers with inpatient headache units around the United States, and those that remain use treatments that most neurologists are not familiar with. Schwenk and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the data of a major academic headache center and revealed impressive outcomes in this very difficult-to-treat population.

This study reviewed the outcomes of 609 consecutive patients admitted to the Thomas Jefferson University inpatient headache unit from 2017 to 2021. These patients all received continuous lidocaine infusions that were titrated according to an internal protocol that balanced daily plasma lidocaine levels, tolerability, and pain relief. Hospital discharge occurred when patients were pain-free for 12-24 hours or had a minimal response after 5 days of treatment. All patients had at least eight severe headaches per month for at least 6 consecutive months and had tried one to seven preventive medications, with the result of either intolerance or ineffectiveness.

The primary outcome was change from baseline to discharge pain level. Patients were admitted with an average score of 7.0 of 10 on admission and were discharged at a score of 1.0 of 10. Secondary outcomes were average pain at post-discharge appointment vs baseline (5.5 vs 7.0), number of monthly headache days at post-discharge appointment (22.5 vs 26.8), and current and average pain levels at the post-discharge appointment, which were both significantly lower as well. The most common adverse effect was nausea; others noted were cardiovascular changes, hallucinations or nightmares, sedation, anxiety, and chest pain.

This is an important retrospective on the effectiveness of an inpatient lidocaine protocol for refractory chronic migraine. When considering this population, especially if multiple lines of preventive and acute medications are not effective, referral to an academic inpatient headache center should definitely be considered. This patient population does not respond effectively to most treatment modalities, and this is cause to give them hope.

Many of our patients with refractory migraine do not respond to first-line acute or preventive treatments, and, almost by definition, first- and second-line treatments have failed in the majority of patients on calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist medications. Three studies this month highlight the efficacy of CGRP monoclonal antibody (mAb) and small-molecule medications in this population specifically.

Most headache specialists are familiar with the "standard" or PREEMPT onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) paradigm used preventively for migraine. This protocol uses 155 units of onabotulinumtoxinA over 31 sites in seven muscle groups. OnabotulinumtoxinA vials typically come in 100 or 200 units, and when preparing onabotulinumtoxinA for patients who are being injected most providers are forced to discard most or all of the remaining 45 units. Anecdotally, some providers do inject the entire 200-unit vial, and the additional injection sites are either given in another standard protocol or in a follow-the-pain manner.

The study by Zandieh and colleagues followed 175 patients with chronic migraine who first received three injections of 150 units of onabotulinumtoxinA, then three injections of 200 units of this agent. The additional 50 units were injected into the temporalis and occipitalis muscles — the standard sites were used, but additional units were injected into each of the sites. The majority of patients experienced primarily frontal pain; the injections were not given in specific areas where more pain was manifesting.

The average number of headache days per month decreased significantly when the onabotulinumtoxinA dose was increased; patients tolerated the medication over the 3-month period as well. In practice, many providers use the additional units of onabotulinumtoxinA. This study argues that there is a minimal risk, and probably a potential significant benefit, when using up to 200 units every 3 months. Providers should, however, be aware that in rare instances, some insurances will only cover a 155-unit injection, and the use of additional units may jeopardize reimbursement for those plans.

Many patients anecdotally will use cold or heat as a treatment for acute migraine pain; however, the topical use of temperature has not been well studied for this purpose. Cold stimulus has, importantly, been known to be a trigger of migraine as well as other headache disorders classified in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD-3), including external cold stimulus headache and "brain freeze" or internal cold stimulus headache. Hsu and colleagues produced a meta-analysis and systematic review on the use of cold for acute treatment of migraine.

Six studies were found to be eligible for this review. The cold stimulus could be placed anywhere on the head, and the studies could have considered its use for any migraine-associated symptom. This includes headache, eye pain, nausea, or vomiting. The interventions used cold somewhat differently, including as ice packing, cooling compression, soaking, and as a rinse. Both randomized and nonrandomized trials were included in the systematic review; however, only randomized controlled trials were used for the meta-analysis.

The primary outcome evaluated by the authors was pain intensity; secondary outcomes were duration of migraine pain as well as associated symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting). The meta-analysis revealed that cold interventions reduce migraine pain by 3.21 points on an analog scale, and this was found to be effective within 30 minutes. At 1-2 hours after the intervention, the effect was not seen to be significant. At 24 hours, the effect of cold intervention was marginal. Cold was not seen to significantly reduce nausea or vomiting at 2 hours after intervention.

Although cold treatments are commonly used by patients, there appears to be benefit only early in the onset of a migraine attack. Headache specialists typically recommend early treatment with a migraine-specific acute medication; however, the medication may take minutes to hours before taking effect. Cold can be recommended to patients during that intervening period, and it may help until the time that their acute medications take effect.

Chronic refractory migraine remains one of the most debilitating neurologic disorders and is a challenge even for the best trained neurologist or headache specialist. There are few headache centers with inpatient headache units around the United States, and those that remain use treatments that most neurologists are not familiar with. Schwenk and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the data of a major academic headache center and revealed impressive outcomes in this very difficult-to-treat population.

This study reviewed the outcomes of 609 consecutive patients admitted to the Thomas Jefferson University inpatient headache unit from 2017 to 2021. These patients all received continuous lidocaine infusions that were titrated according to an internal protocol that balanced daily plasma lidocaine levels, tolerability, and pain relief. Hospital discharge occurred when patients were pain-free for 12-24 hours or had a minimal response after 5 days of treatment. All patients had at least eight severe headaches per month for at least 6 consecutive months and had tried one to seven preventive medications, with the result of either intolerance or ineffectiveness.

The primary outcome was change from baseline to discharge pain level. Patients were admitted with an average score of 7.0 of 10 on admission and were discharged at a score of 1.0 of 10. Secondary outcomes were average pain at post-discharge appointment vs baseline (5.5 vs 7.0), number of monthly headache days at post-discharge appointment (22.5 vs 26.8), and current and average pain levels at the post-discharge appointment, which were both significantly lower as well. The most common adverse effect was nausea; others noted were cardiovascular changes, hallucinations or nightmares, sedation, anxiety, and chest pain.

This is an important retrospective on the effectiveness of an inpatient lidocaine protocol for refractory chronic migraine. When considering this population, especially if multiple lines of preventive and acute medications are not effective, referral to an academic inpatient headache center should definitely be considered. This patient population does not respond effectively to most treatment modalities, and this is cause to give them hope.

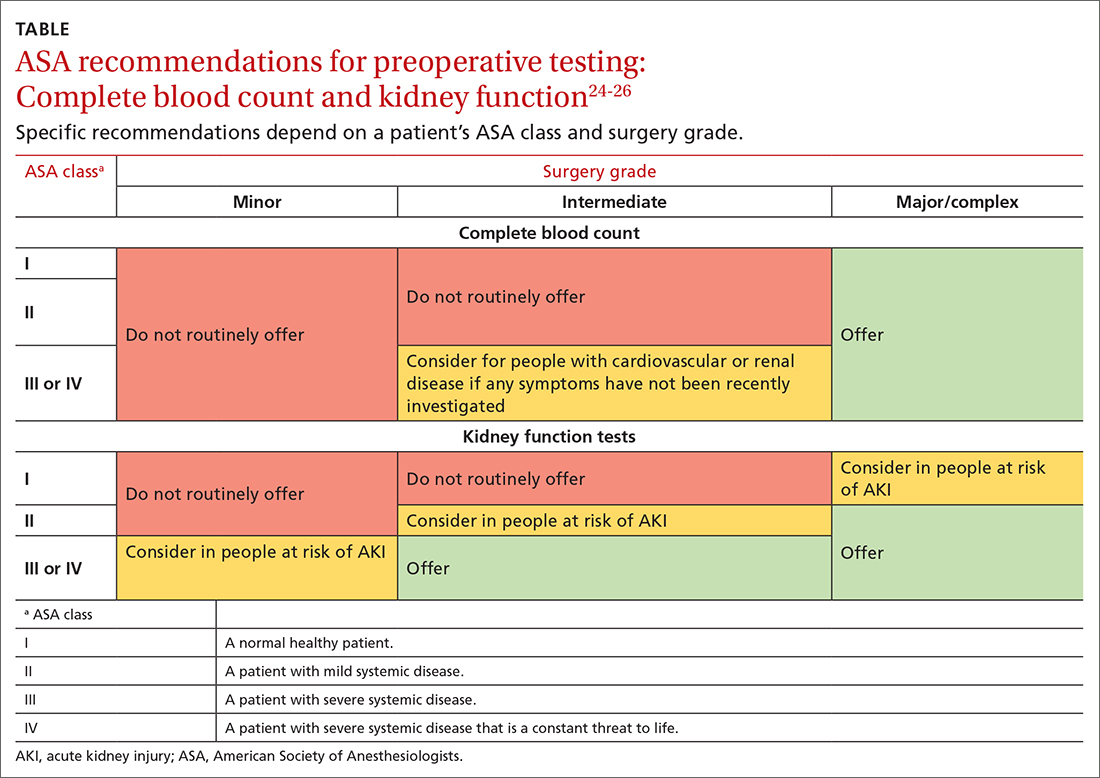

No more injections after one-off gene therapy in hemophilia B

Patients with hemophilia B face a lifelong need for regular factor IX injections.

“Removing the need for hemophilia patients to regularly inject themselves with the missing protein is an important step in improving their quality of life,” lead author Pratima Chowdary, MD, of the Royal Free Hospital, University College London Cancer Institute, commented in a press statement.

The team reported new results with the investigational gene therapy FLT180a in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We found that normal factor IX levels can be achieved in patients with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B with the use of relatively low vector doses of FLT180a,” the authors reported. “In all but one patient, gene therapy led to durable factor IX expression, eliminated the need for factor IX prophylaxis, and eliminated spontaneous bleeding leading to factor IX replacement.”

FLT180a (Freeline Therapeutics) is a liver-directed, adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy designed to normalize levels of the factor IX protein that is needed for coagulation; however, it is produced in dangerously low levels in people with hemophilia B as a result of gene mutations.

Under the current standard of care, patients with hemophilia B require lifelong prophylaxis of regular intravenous injections with recombinant factor IX replacement therapy, and they commonly continue to experience potentially severe joint pain.

While factor-replacement therapies with longer half-lives have emerged, the prophylaxis is still invasive and extremely expensive, with the average price tag in the United States of $397,491 a year for the conventional treatment and an average of $788,861 a year for an extended half-life treatment, according to a 2019 report.

Novel gene therapy

Hemophilia B is a rare and inherited genetic bleeding disorder caused by defects in the gene responsible for factor IX protein, which is needed for blood clotting.

AAV gene therapy delivers a functional copy of this gene directly to patient tissues to compensate for one that is not working properly. It leads to the synthesis of factor IX proteins and a one-time gene therapy infusion can achieve long-lasting effects, the team explained in a press release.

The results they reported come from the phase 1/2 multicenter B-AMAZE open-label trial. It involved 10 patients (all age 18 and older) with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B, defined as having a factor IX level of 2% or less that of normal values.

All patients received one-off gene therapy infusion, at one of four FLT180a doses.

All patients also received immunosuppression to prevent the body from rejecting the vector gene therapy. This consisted of glucocorticoids with or without tacrolimus for a period of ranging from several weeks to several months.

Following the FLT180a infusion, all patients showed dose-dependent increases in factor IX levels. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months (range, 19.1-42.4 months), nearly all the patients (9 of 10) continued to show sustained factor IX activity.

Steady production of factor IX activity started at month 12, with low bleeding frequency that allowed these nine patients to no longer require weekly injections of the protein.

Five of the patients had factor IX levels in the normal range, from 51% to 78%; three patients had lower increases of 23%-43% of the normal range, and one patient who had received the highest dose, had a level that was 260% of normal.

The exception was one patient who required a return to factor IX prophylaxis. He had experienced a failure in the immunosuppression regimen due to a delay in the recognition of an immune response at approximately 22 weeks after treatment, the authors reported.

The therapy was generally well tolerated, with no infusion reactions or discontinuations of infusions. As of the study cutoff, no inhibitors of factor IX were detected.

Of the adverse events, about 10% were determined to be related to the gene therapy. The most common event associated with the gene therapy was increases in liver aminotransferase, which is a concern with AAV gene therapies, the authors commented.

Otherwise, 24% of adverse events were determined to be related to the immunosuppression, and were consistent with the known safety profiles of glucocorticoids and tacrolimus.

Late increases in aminotransferase levels were reported among patients who had received prolonged tacrolimus beyond the tapering of glucocorticoid treatment.

The one serious adverse event that was reported involved an arteriovenous fistula thrombosis, which occurred in the patient who had received the highest dose of gene therapy and who showed the highest factor IX levels.

The current findings, along with data from another recent study involving gene therapy for patients with hemophilia A, emphasized that “immune responses can occur later than previously expected and may coincide with the withdrawal of immunosuppression,” the authors cautioned.

“Consistent best practices for monitoring aminotransferase levels and deciding when ALT increases warrant intervention remain a critical topic for the field,” they noted.

Meanwhile, the patients in this B-AMAZE trial all remain enrolled in a long-term follow-up study to assess the safety and durability of FLT180a over 15 years.

The trial was sponsored by University College London and funded by Freeline Therapeutics. Dr. Chowdary disclosed various relationships with industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with hemophilia B face a lifelong need for regular factor IX injections.

“Removing the need for hemophilia patients to regularly inject themselves with the missing protein is an important step in improving their quality of life,” lead author Pratima Chowdary, MD, of the Royal Free Hospital, University College London Cancer Institute, commented in a press statement.

The team reported new results with the investigational gene therapy FLT180a in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We found that normal factor IX levels can be achieved in patients with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B with the use of relatively low vector doses of FLT180a,” the authors reported. “In all but one patient, gene therapy led to durable factor IX expression, eliminated the need for factor IX prophylaxis, and eliminated spontaneous bleeding leading to factor IX replacement.”

FLT180a (Freeline Therapeutics) is a liver-directed, adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy designed to normalize levels of the factor IX protein that is needed for coagulation; however, it is produced in dangerously low levels in people with hemophilia B as a result of gene mutations.

Under the current standard of care, patients with hemophilia B require lifelong prophylaxis of regular intravenous injections with recombinant factor IX replacement therapy, and they commonly continue to experience potentially severe joint pain.

While factor-replacement therapies with longer half-lives have emerged, the prophylaxis is still invasive and extremely expensive, with the average price tag in the United States of $397,491 a year for the conventional treatment and an average of $788,861 a year for an extended half-life treatment, according to a 2019 report.

Novel gene therapy

Hemophilia B is a rare and inherited genetic bleeding disorder caused by defects in the gene responsible for factor IX protein, which is needed for blood clotting.

AAV gene therapy delivers a functional copy of this gene directly to patient tissues to compensate for one that is not working properly. It leads to the synthesis of factor IX proteins and a one-time gene therapy infusion can achieve long-lasting effects, the team explained in a press release.

The results they reported come from the phase 1/2 multicenter B-AMAZE open-label trial. It involved 10 patients (all age 18 and older) with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B, defined as having a factor IX level of 2% or less that of normal values.

All patients received one-off gene therapy infusion, at one of four FLT180a doses.

All patients also received immunosuppression to prevent the body from rejecting the vector gene therapy. This consisted of glucocorticoids with or without tacrolimus for a period of ranging from several weeks to several months.

Following the FLT180a infusion, all patients showed dose-dependent increases in factor IX levels. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months (range, 19.1-42.4 months), nearly all the patients (9 of 10) continued to show sustained factor IX activity.

Steady production of factor IX activity started at month 12, with low bleeding frequency that allowed these nine patients to no longer require weekly injections of the protein.

Five of the patients had factor IX levels in the normal range, from 51% to 78%; three patients had lower increases of 23%-43% of the normal range, and one patient who had received the highest dose, had a level that was 260% of normal.

The exception was one patient who required a return to factor IX prophylaxis. He had experienced a failure in the immunosuppression regimen due to a delay in the recognition of an immune response at approximately 22 weeks after treatment, the authors reported.

The therapy was generally well tolerated, with no infusion reactions or discontinuations of infusions. As of the study cutoff, no inhibitors of factor IX were detected.

Of the adverse events, about 10% were determined to be related to the gene therapy. The most common event associated with the gene therapy was increases in liver aminotransferase, which is a concern with AAV gene therapies, the authors commented.

Otherwise, 24% of adverse events were determined to be related to the immunosuppression, and were consistent with the known safety profiles of glucocorticoids and tacrolimus.

Late increases in aminotransferase levels were reported among patients who had received prolonged tacrolimus beyond the tapering of glucocorticoid treatment.

The one serious adverse event that was reported involved an arteriovenous fistula thrombosis, which occurred in the patient who had received the highest dose of gene therapy and who showed the highest factor IX levels.

The current findings, along with data from another recent study involving gene therapy for patients with hemophilia A, emphasized that “immune responses can occur later than previously expected and may coincide with the withdrawal of immunosuppression,” the authors cautioned.

“Consistent best practices for monitoring aminotransferase levels and deciding when ALT increases warrant intervention remain a critical topic for the field,” they noted.

Meanwhile, the patients in this B-AMAZE trial all remain enrolled in a long-term follow-up study to assess the safety and durability of FLT180a over 15 years.

The trial was sponsored by University College London and funded by Freeline Therapeutics. Dr. Chowdary disclosed various relationships with industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with hemophilia B face a lifelong need for regular factor IX injections.

“Removing the need for hemophilia patients to regularly inject themselves with the missing protein is an important step in improving their quality of life,” lead author Pratima Chowdary, MD, of the Royal Free Hospital, University College London Cancer Institute, commented in a press statement.

The team reported new results with the investigational gene therapy FLT180a in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“We found that normal factor IX levels can be achieved in patients with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B with the use of relatively low vector doses of FLT180a,” the authors reported. “In all but one patient, gene therapy led to durable factor IX expression, eliminated the need for factor IX prophylaxis, and eliminated spontaneous bleeding leading to factor IX replacement.”

FLT180a (Freeline Therapeutics) is a liver-directed, adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy designed to normalize levels of the factor IX protein that is needed for coagulation; however, it is produced in dangerously low levels in people with hemophilia B as a result of gene mutations.

Under the current standard of care, patients with hemophilia B require lifelong prophylaxis of regular intravenous injections with recombinant factor IX replacement therapy, and they commonly continue to experience potentially severe joint pain.

While factor-replacement therapies with longer half-lives have emerged, the prophylaxis is still invasive and extremely expensive, with the average price tag in the United States of $397,491 a year for the conventional treatment and an average of $788,861 a year for an extended half-life treatment, according to a 2019 report.

Novel gene therapy

Hemophilia B is a rare and inherited genetic bleeding disorder caused by defects in the gene responsible for factor IX protein, which is needed for blood clotting.

AAV gene therapy delivers a functional copy of this gene directly to patient tissues to compensate for one that is not working properly. It leads to the synthesis of factor IX proteins and a one-time gene therapy infusion can achieve long-lasting effects, the team explained in a press release.

The results they reported come from the phase 1/2 multicenter B-AMAZE open-label trial. It involved 10 patients (all age 18 and older) with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B, defined as having a factor IX level of 2% or less that of normal values.

All patients received one-off gene therapy infusion, at one of four FLT180a doses.

All patients also received immunosuppression to prevent the body from rejecting the vector gene therapy. This consisted of glucocorticoids with or without tacrolimus for a period of ranging from several weeks to several months.

Following the FLT180a infusion, all patients showed dose-dependent increases in factor IX levels. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months (range, 19.1-42.4 months), nearly all the patients (9 of 10) continued to show sustained factor IX activity.

Steady production of factor IX activity started at month 12, with low bleeding frequency that allowed these nine patients to no longer require weekly injections of the protein.

Five of the patients had factor IX levels in the normal range, from 51% to 78%; three patients had lower increases of 23%-43% of the normal range, and one patient who had received the highest dose, had a level that was 260% of normal.

The exception was one patient who required a return to factor IX prophylaxis. He had experienced a failure in the immunosuppression regimen due to a delay in the recognition of an immune response at approximately 22 weeks after treatment, the authors reported.

The therapy was generally well tolerated, with no infusion reactions or discontinuations of infusions. As of the study cutoff, no inhibitors of factor IX were detected.

Of the adverse events, about 10% were determined to be related to the gene therapy. The most common event associated with the gene therapy was increases in liver aminotransferase, which is a concern with AAV gene therapies, the authors commented.

Otherwise, 24% of adverse events were determined to be related to the immunosuppression, and were consistent with the known safety profiles of glucocorticoids and tacrolimus.

Late increases in aminotransferase levels were reported among patients who had received prolonged tacrolimus beyond the tapering of glucocorticoid treatment.

The one serious adverse event that was reported involved an arteriovenous fistula thrombosis, which occurred in the patient who had received the highest dose of gene therapy and who showed the highest factor IX levels.

The current findings, along with data from another recent study involving gene therapy for patients with hemophilia A, emphasized that “immune responses can occur later than previously expected and may coincide with the withdrawal of immunosuppression,” the authors cautioned.

“Consistent best practices for monitoring aminotransferase levels and deciding when ALT increases warrant intervention remain a critical topic for the field,” they noted.

Meanwhile, the patients in this B-AMAZE trial all remain enrolled in a long-term follow-up study to assess the safety and durability of FLT180a over 15 years.

The trial was sponsored by University College London and funded by Freeline Therapeutics. Dr. Chowdary disclosed various relationships with industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

In the Quest for Migraine Relief, The Search for Biomarkers Intensifies

The Health Terminology/Ontology Portal (HeTOP), on which the curious can discover information about off-label use, lists 645 medications prescribed for migraine worldwide. Treatments ranging from blood pressure medications to antidepressants, and anticonvulsants to antiepileptics, along with their doses and administrations, are all listed. The number of migraine-indicated medications is 114. Dominated by triptans and topiramate, the list also includes erenumab, the calcitonin gene-related peptide CGRP agonist. The difference in figures between the predominately off label and migraine-approved lists is a good indicator of the struggle that health care providers have had through the years to help their patients.

The idea now is to make that list even longer by finding biomarkers that lead to new therapies.

But first, a conversation about the trigeminal ganglia.

The trigeminal ganglia

The trigeminal ganglia sit on either side of the head, in front of the ears. Their primary role is to receive stimuli and convey it to the brain. The human trigeminal ganglia contain 20,000 to 35,000 neurons and express an array of neuropeptides, including CGRP. Some neuropeptides, like CGRP and pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating peptide 38 (PACAP38) are vasodilators. Others, like substance P, are vasoconstrictors. Edvinsson and Goadsby discussed in 1994 how CGRP was released simultaneously in those with “spontaneous attacks of migraine.”

Over the past 30 years, researchers in our institution and elsewhere have shown repeatedly that migraine develops in individuals who are exposed to certain signaling molecules, namely nitroglycerin, CGRP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), potassium, and PACAP38, among others. Such exposure reinforces the notion that peripheral sensitization of trigeminal sensory neurons brings on headache. The attack could occur due to vasodilation, mast cell degranulation, involvement of the parasympathetic system, or activation of nerve fibers.

Some examples from the literature:

- In our research, results from a small study of patients under spontaneous migraine attack, who underwent a 3-Tesla MRI scan, showed that cortical thickness diminishes in the prefrontal and pericalcarine cortices. The analysis we performed involving individuals with migraine without aura revealed that these patients experience reduced cortical thickness and volume when migraine attacks come on, suggesting that cortical thickness and volume may serve as a potential biomarker.

- A comparison of 20 individuals with chronic migraine and 20 healthy controls by way of 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scans revealed that those with headache appeared to have substantially increased neural connectivity between the hypothalamus and certain brain areas – yet there appeared to be no connectivity irregularities between the hypothalamus and brainstem, which as the authors noted, is the “migraine generator.”

In other words, vasodilation might be a secondary symptom of migraine but likely isn’t its source.

Other migraine makers

Neurochemicals and nucleotides play a role in migraine formation, too:

- Nitric oxide. Can open blood vessels in the head and brain and has been shown to set migraine in motion. It leads to peak headache intensity 5.5 hours after infusion and causes migraine without aura.

- GRP. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptors cause delayed headache, including what qualifies as an induced migraine attack. Researchers also note that similar pathways trigger migraine with and without aura.

- Intracellular cGMP and intracellular cAMP. These 2 cyclic nucleotides are found extensively in the trigeminovascular system and have a role in the pathogenesis of migraine. Studies demonstrate that cGMP levels increase after nitroglycerin administration and cAMP increases after CGRP and PACAP38 exposure.

- Levcromakalim. This potassium channel opener is sensitive to ATP. In a trial published in 2019, researchers showed that modulating potassium channels could cause some headache pain, even in those without migraine. They infused 20 healthy volunteers with levcromakalim; over the next 5-plus hours, the middle meningeal artery of all 20 became and remained dilated. Later research showed that this dilation is linked to substance P.

Identifying migraine types

Diagnosing migraine is 1 step; determining its type is another.

Consider that a person with a posttraumatic headache can have migraine-like symptoms. To find objective separate characteristics, researchers at Mayo Clinic designed a headache classification model using questionnaires, which were then paired with the patient’s MRI data. The questionnaires delved into headache characteristics, sensory hypersensitivities, cognitive functioning, and mood. The system worked well with primary migraine, with 97% accuracy. But with posttraumatic headache, the system was 65% accurate. What proved to differentiate persistent posttraumatic headache were questions regarding decision making and anxiety. These patients had severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, physical issues, and mild brain injury attributed to blasts.

All of which explains why we and others are actively looking for biomarkers.

The biomarkers

A look at clinicaltrials.gov shows that 15 trials are recruiting patients (including us) in the search for biomarkers. One wants to identify a computational algorithm using AI, based on 9 types of markers in hopes of identifying those predictive elements that will respond to CGRP-targeting monoclonal antibodies (mABs). The factors range from the clinical to epigenetic to structural and functional brain imaging. Another registered study is using ocular coherence tomography, among other technologies, to identify photophobia.

Our interests are in identifying CGRP as a definitive biomarker; finding structural and functional cerebral changes, using MRI, in study subjects before and after they are given erenumab. We also want to create a registry for migraine based on the structural and functional MRI findings.

Another significant reason for finding biomarkers is to identify the alteration that accompany progression from episodic to chronic migraine. Pozo-Rosich et al write that these imaging, neurophysiological, and biochemical changes that occur with this progression could be used “for developing chronic migraine biomarkers that might assist with diagnosis, prognosticating individual patient outcomes, and predicting responses to migraine therapies.” And, ultimately, in practicing precision medicine to improve care of patients.

Significant barriers still exist in declaring a molecule is a biomarker. For example, a meta-analysis points to the replication challenge observed in neuroimaging research. Additionally, several genetic variants produce small effect sizes, which also might be impacted by environmental factors. This makes it difficult to map genetic biomarkers. Large prospective studies are needed to bring this area of research out of infancy to a place where treatment response can be clinically assessed. Additionally, while research evaluating provocation biomarkers has already contributed to the treatment landscape, large-scale registry studies may help uncover a predictive biomarker of treatment response. Blood biomarker research still needs a standardized protocol. Imaging-based biomarkers show much potential, but standardized imaging protocols and improved characterization and data integration are necessary going forward.

The patients

The discovery of the CGRPs couldn’t have been more timely.

Those of us who have been treating patients with migraine for years have seen the prevalence of this disease slowly rise. In 2018, the age-adjusted prevalence was 15.9% for all adults in the United States; in 2010, it was 13.2%. Worldwide, in 2019, it was 14%. In 2015, it was 11.6%.

In the past few years, journal articles have appeared regarding the connection between obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and migraine severity. Numerous other comorbidities affect our patients – not just the well-known psychiatric disorders – but also the respiratory, digestive, and central nervous system illnesses.

In other words, many of our patients come to us sicker than in years past.

Some cannot take one or more medications designed for acute migraine attacks due to comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease or related risk factors, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

A large survey of 15,133 people with migraine confirmed the findings on these numerous comorbidities; they reported that they have more insomnia, depression, and anxiety. As the authors point out, identifying these comorbidities can help with accurate diagnosis, treatment and its adherence, and prognosis. The authors also noted that as migraine days increase per month, so do the rates of comorbidities.

But the CGRPs are showing how beneficial they can be. One study assessing medication overuse showed how 60% of the enrolled patients no longer fit that description 6 months after receiving erenumab or galcanezumab. Some patients who contend with episodic migraine showed a complete response after receiving eptinezumab and galcanezumab. They also have helped patients with menstrual migraine and refractory migraine.

But they are not complete responses to these medications, which is an excellent reason to continue viewing, recording, and assessing the migraine brain, for all it can tell us.

The Health Terminology/Ontology Portal (HeTOP), on which the curious can discover information about off-label use, lists 645 medications prescribed for migraine worldwide. Treatments ranging from blood pressure medications to antidepressants, and anticonvulsants to antiepileptics, along with their doses and administrations, are all listed. The number of migraine-indicated medications is 114. Dominated by triptans and topiramate, the list also includes erenumab, the calcitonin gene-related peptide CGRP agonist. The difference in figures between the predominately off label and migraine-approved lists is a good indicator of the struggle that health care providers have had through the years to help their patients.

The idea now is to make that list even longer by finding biomarkers that lead to new therapies.

But first, a conversation about the trigeminal ganglia.

The trigeminal ganglia

The trigeminal ganglia sit on either side of the head, in front of the ears. Their primary role is to receive stimuli and convey it to the brain. The human trigeminal ganglia contain 20,000 to 35,000 neurons and express an array of neuropeptides, including CGRP. Some neuropeptides, like CGRP and pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating peptide 38 (PACAP38) are vasodilators. Others, like substance P, are vasoconstrictors. Edvinsson and Goadsby discussed in 1994 how CGRP was released simultaneously in those with “spontaneous attacks of migraine.”

Over the past 30 years, researchers in our institution and elsewhere have shown repeatedly that migraine develops in individuals who are exposed to certain signaling molecules, namely nitroglycerin, CGRP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), potassium, and PACAP38, among others. Such exposure reinforces the notion that peripheral sensitization of trigeminal sensory neurons brings on headache. The attack could occur due to vasodilation, mast cell degranulation, involvement of the parasympathetic system, or activation of nerve fibers.

Some examples from the literature:

- In our research, results from a small study of patients under spontaneous migraine attack, who underwent a 3-Tesla MRI scan, showed that cortical thickness diminishes in the prefrontal and pericalcarine cortices. The analysis we performed involving individuals with migraine without aura revealed that these patients experience reduced cortical thickness and volume when migraine attacks come on, suggesting that cortical thickness and volume may serve as a potential biomarker.

- A comparison of 20 individuals with chronic migraine and 20 healthy controls by way of 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scans revealed that those with headache appeared to have substantially increased neural connectivity between the hypothalamus and certain brain areas – yet there appeared to be no connectivity irregularities between the hypothalamus and brainstem, which as the authors noted, is the “migraine generator.”

In other words, vasodilation might be a secondary symptom of migraine but likely isn’t its source.

Other migraine makers

Neurochemicals and nucleotides play a role in migraine formation, too:

- Nitric oxide. Can open blood vessels in the head and brain and has been shown to set migraine in motion. It leads to peak headache intensity 5.5 hours after infusion and causes migraine without aura.

- GRP. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptors cause delayed headache, including what qualifies as an induced migraine attack. Researchers also note that similar pathways trigger migraine with and without aura.

- Intracellular cGMP and intracellular cAMP. These 2 cyclic nucleotides are found extensively in the trigeminovascular system and have a role in the pathogenesis of migraine. Studies demonstrate that cGMP levels increase after nitroglycerin administration and cAMP increases after CGRP and PACAP38 exposure.

- Levcromakalim. This potassium channel opener is sensitive to ATP. In a trial published in 2019, researchers showed that modulating potassium channels could cause some headache pain, even in those without migraine. They infused 20 healthy volunteers with levcromakalim; over the next 5-plus hours, the middle meningeal artery of all 20 became and remained dilated. Later research showed that this dilation is linked to substance P.

Identifying migraine types

Diagnosing migraine is 1 step; determining its type is another.

Consider that a person with a posttraumatic headache can have migraine-like symptoms. To find objective separate characteristics, researchers at Mayo Clinic designed a headache classification model using questionnaires, which were then paired with the patient’s MRI data. The questionnaires delved into headache characteristics, sensory hypersensitivities, cognitive functioning, and mood. The system worked well with primary migraine, with 97% accuracy. But with posttraumatic headache, the system was 65% accurate. What proved to differentiate persistent posttraumatic headache were questions regarding decision making and anxiety. These patients had severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, physical issues, and mild brain injury attributed to blasts.

All of which explains why we and others are actively looking for biomarkers.

The biomarkers

A look at clinicaltrials.gov shows that 15 trials are recruiting patients (including us) in the search for biomarkers. One wants to identify a computational algorithm using AI, based on 9 types of markers in hopes of identifying those predictive elements that will respond to CGRP-targeting monoclonal antibodies (mABs). The factors range from the clinical to epigenetic to structural and functional brain imaging. Another registered study is using ocular coherence tomography, among other technologies, to identify photophobia.

Our interests are in identifying CGRP as a definitive biomarker; finding structural and functional cerebral changes, using MRI, in study subjects before and after they are given erenumab. We also want to create a registry for migraine based on the structural and functional MRI findings.

Another significant reason for finding biomarkers is to identify the alteration that accompany progression from episodic to chronic migraine. Pozo-Rosich et al write that these imaging, neurophysiological, and biochemical changes that occur with this progression could be used “for developing chronic migraine biomarkers that might assist with diagnosis, prognosticating individual patient outcomes, and predicting responses to migraine therapies.” And, ultimately, in practicing precision medicine to improve care of patients.

Significant barriers still exist in declaring a molecule is a biomarker. For example, a meta-analysis points to the replication challenge observed in neuroimaging research. Additionally, several genetic variants produce small effect sizes, which also might be impacted by environmental factors. This makes it difficult to map genetic biomarkers. Large prospective studies are needed to bring this area of research out of infancy to a place where treatment response can be clinically assessed. Additionally, while research evaluating provocation biomarkers has already contributed to the treatment landscape, large-scale registry studies may help uncover a predictive biomarker of treatment response. Blood biomarker research still needs a standardized protocol. Imaging-based biomarkers show much potential, but standardized imaging protocols and improved characterization and data integration are necessary going forward.

The patients

The discovery of the CGRPs couldn’t have been more timely.

Those of us who have been treating patients with migraine for years have seen the prevalence of this disease slowly rise. In 2018, the age-adjusted prevalence was 15.9% for all adults in the United States; in 2010, it was 13.2%. Worldwide, in 2019, it was 14%. In 2015, it was 11.6%.

In the past few years, journal articles have appeared regarding the connection between obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and migraine severity. Numerous other comorbidities affect our patients – not just the well-known psychiatric disorders – but also the respiratory, digestive, and central nervous system illnesses.

In other words, many of our patients come to us sicker than in years past.

Some cannot take one or more medications designed for acute migraine attacks due to comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease or related risk factors, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

A large survey of 15,133 people with migraine confirmed the findings on these numerous comorbidities; they reported that they have more insomnia, depression, and anxiety. As the authors point out, identifying these comorbidities can help with accurate diagnosis, treatment and its adherence, and prognosis. The authors also noted that as migraine days increase per month, so do the rates of comorbidities.

But the CGRPs are showing how beneficial they can be. One study assessing medication overuse showed how 60% of the enrolled patients no longer fit that description 6 months after receiving erenumab or galcanezumab. Some patients who contend with episodic migraine showed a complete response after receiving eptinezumab and galcanezumab. They also have helped patients with menstrual migraine and refractory migraine.

But they are not complete responses to these medications, which is an excellent reason to continue viewing, recording, and assessing the migraine brain, for all it can tell us.

The Health Terminology/Ontology Portal (HeTOP), on which the curious can discover information about off-label use, lists 645 medications prescribed for migraine worldwide. Treatments ranging from blood pressure medications to antidepressants, and anticonvulsants to antiepileptics, along with their doses and administrations, are all listed. The number of migraine-indicated medications is 114. Dominated by triptans and topiramate, the list also includes erenumab, the calcitonin gene-related peptide CGRP agonist. The difference in figures between the predominately off label and migraine-approved lists is a good indicator of the struggle that health care providers have had through the years to help their patients.

The idea now is to make that list even longer by finding biomarkers that lead to new therapies.

But first, a conversation about the trigeminal ganglia.

The trigeminal ganglia

The trigeminal ganglia sit on either side of the head, in front of the ears. Their primary role is to receive stimuli and convey it to the brain. The human trigeminal ganglia contain 20,000 to 35,000 neurons and express an array of neuropeptides, including CGRP. Some neuropeptides, like CGRP and pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating peptide 38 (PACAP38) are vasodilators. Others, like substance P, are vasoconstrictors. Edvinsson and Goadsby discussed in 1994 how CGRP was released simultaneously in those with “spontaneous attacks of migraine.”

Over the past 30 years, researchers in our institution and elsewhere have shown repeatedly that migraine develops in individuals who are exposed to certain signaling molecules, namely nitroglycerin, CGRP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), potassium, and PACAP38, among others. Such exposure reinforces the notion that peripheral sensitization of trigeminal sensory neurons brings on headache. The attack could occur due to vasodilation, mast cell degranulation, involvement of the parasympathetic system, or activation of nerve fibers.

Some examples from the literature:

- In our research, results from a small study of patients under spontaneous migraine attack, who underwent a 3-Tesla MRI scan, showed that cortical thickness diminishes in the prefrontal and pericalcarine cortices. The analysis we performed involving individuals with migraine without aura revealed that these patients experience reduced cortical thickness and volume when migraine attacks come on, suggesting that cortical thickness and volume may serve as a potential biomarker.

- A comparison of 20 individuals with chronic migraine and 20 healthy controls by way of 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scans revealed that those with headache appeared to have substantially increased neural connectivity between the hypothalamus and certain brain areas – yet there appeared to be no connectivity irregularities between the hypothalamus and brainstem, which as the authors noted, is the “migraine generator.”

In other words, vasodilation might be a secondary symptom of migraine but likely isn’t its source.

Other migraine makers

Neurochemicals and nucleotides play a role in migraine formation, too:

- Nitric oxide. Can open blood vessels in the head and brain and has been shown to set migraine in motion. It leads to peak headache intensity 5.5 hours after infusion and causes migraine without aura.

- GRP. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptors cause delayed headache, including what qualifies as an induced migraine attack. Researchers also note that similar pathways trigger migraine with and without aura.

- Intracellular cGMP and intracellular cAMP. These 2 cyclic nucleotides are found extensively in the trigeminovascular system and have a role in the pathogenesis of migraine. Studies demonstrate that cGMP levels increase after nitroglycerin administration and cAMP increases after CGRP and PACAP38 exposure.

- Levcromakalim. This potassium channel opener is sensitive to ATP. In a trial published in 2019, researchers showed that modulating potassium channels could cause some headache pain, even in those without migraine. They infused 20 healthy volunteers with levcromakalim; over the next 5-plus hours, the middle meningeal artery of all 20 became and remained dilated. Later research showed that this dilation is linked to substance P.

Identifying migraine types

Diagnosing migraine is 1 step; determining its type is another.

Consider that a person with a posttraumatic headache can have migraine-like symptoms. To find objective separate characteristics, researchers at Mayo Clinic designed a headache classification model using questionnaires, which were then paired with the patient’s MRI data. The questionnaires delved into headache characteristics, sensory hypersensitivities, cognitive functioning, and mood. The system worked well with primary migraine, with 97% accuracy. But with posttraumatic headache, the system was 65% accurate. What proved to differentiate persistent posttraumatic headache were questions regarding decision making and anxiety. These patients had severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, physical issues, and mild brain injury attributed to blasts.

All of which explains why we and others are actively looking for biomarkers.

The biomarkers

A look at clinicaltrials.gov shows that 15 trials are recruiting patients (including us) in the search for biomarkers. One wants to identify a computational algorithm using AI, based on 9 types of markers in hopes of identifying those predictive elements that will respond to CGRP-targeting monoclonal antibodies (mABs). The factors range from the clinical to epigenetic to structural and functional brain imaging. Another registered study is using ocular coherence tomography, among other technologies, to identify photophobia.

Our interests are in identifying CGRP as a definitive biomarker; finding structural and functional cerebral changes, using MRI, in study subjects before and after they are given erenumab. We also want to create a registry for migraine based on the structural and functional MRI findings.

Another significant reason for finding biomarkers is to identify the alteration that accompany progression from episodic to chronic migraine. Pozo-Rosich et al write that these imaging, neurophysiological, and biochemical changes that occur with this progression could be used “for developing chronic migraine biomarkers that might assist with diagnosis, prognosticating individual patient outcomes, and predicting responses to migraine therapies.” And, ultimately, in practicing precision medicine to improve care of patients.

Significant barriers still exist in declaring a molecule is a biomarker. For example, a meta-analysis points to the replication challenge observed in neuroimaging research. Additionally, several genetic variants produce small effect sizes, which also might be impacted by environmental factors. This makes it difficult to map genetic biomarkers. Large prospective studies are needed to bring this area of research out of infancy to a place where treatment response can be clinically assessed. Additionally, while research evaluating provocation biomarkers has already contributed to the treatment landscape, large-scale registry studies may help uncover a predictive biomarker of treatment response. Blood biomarker research still needs a standardized protocol. Imaging-based biomarkers show much potential, but standardized imaging protocols and improved characterization and data integration are necessary going forward.

The patients

The discovery of the CGRPs couldn’t have been more timely.

Those of us who have been treating patients with migraine for years have seen the prevalence of this disease slowly rise. In 2018, the age-adjusted prevalence was 15.9% for all adults in the United States; in 2010, it was 13.2%. Worldwide, in 2019, it was 14%. In 2015, it was 11.6%.

In the past few years, journal articles have appeared regarding the connection between obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and migraine severity. Numerous other comorbidities affect our patients – not just the well-known psychiatric disorders – but also the respiratory, digestive, and central nervous system illnesses.

In other words, many of our patients come to us sicker than in years past.

Some cannot take one or more medications designed for acute migraine attacks due to comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease or related risk factors, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

A large survey of 15,133 people with migraine confirmed the findings on these numerous comorbidities; they reported that they have more insomnia, depression, and anxiety. As the authors point out, identifying these comorbidities can help with accurate diagnosis, treatment and its adherence, and prognosis. The authors also noted that as migraine days increase per month, so do the rates of comorbidities.

But the CGRPs are showing how beneficial they can be. One study assessing medication overuse showed how 60% of the enrolled patients no longer fit that description 6 months after receiving erenumab or galcanezumab. Some patients who contend with episodic migraine showed a complete response after receiving eptinezumab and galcanezumab. They also have helped patients with menstrual migraine and refractory migraine.

But they are not complete responses to these medications, which is an excellent reason to continue viewing, recording, and assessing the migraine brain, for all it can tell us.

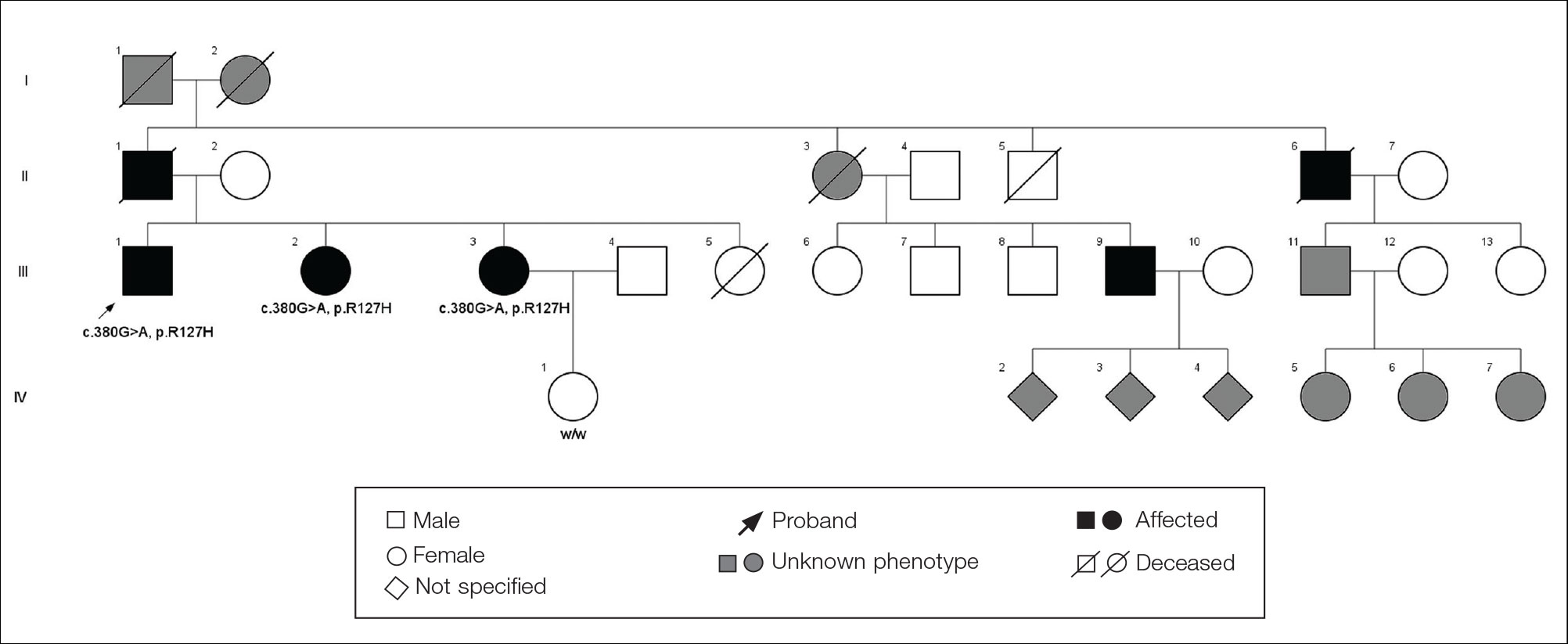

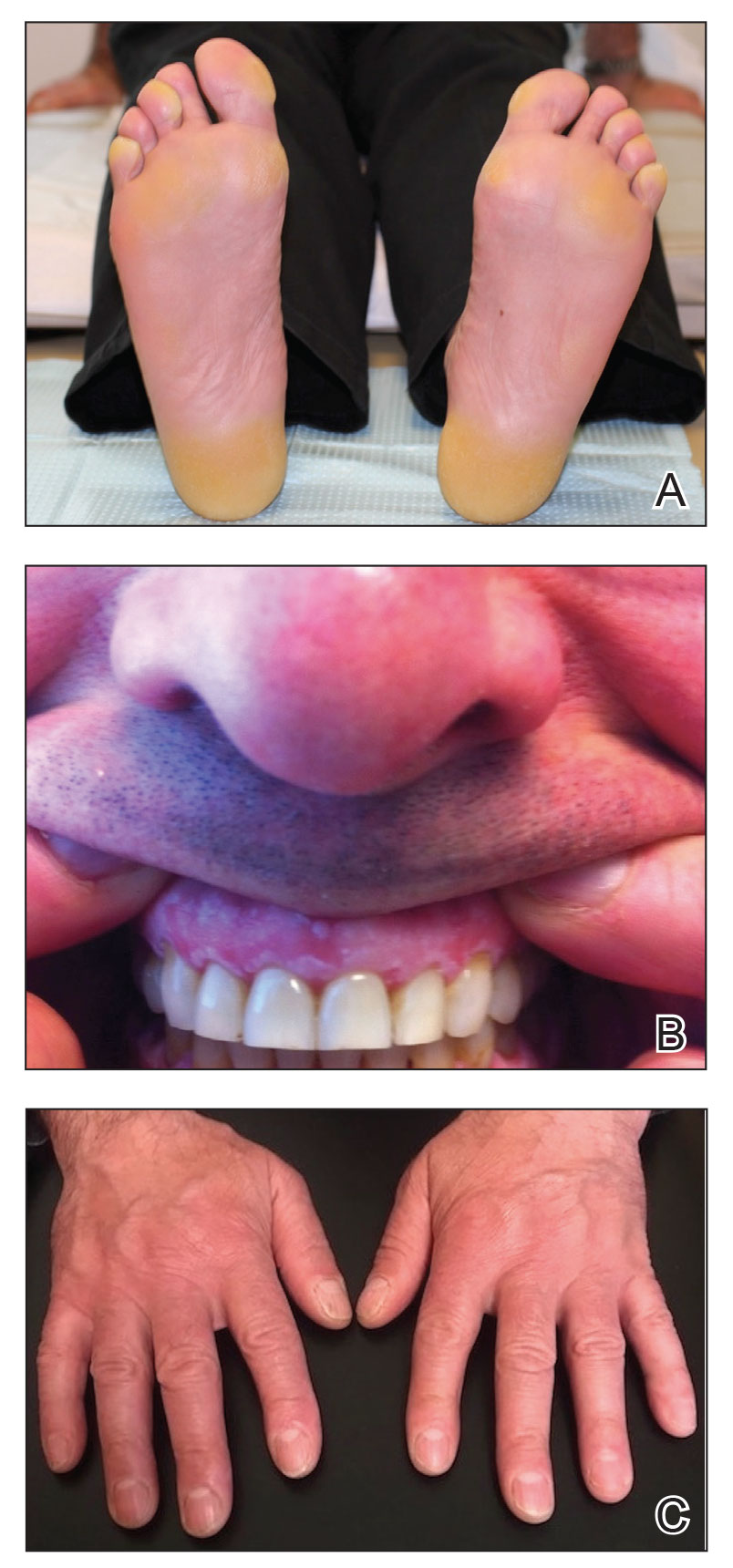

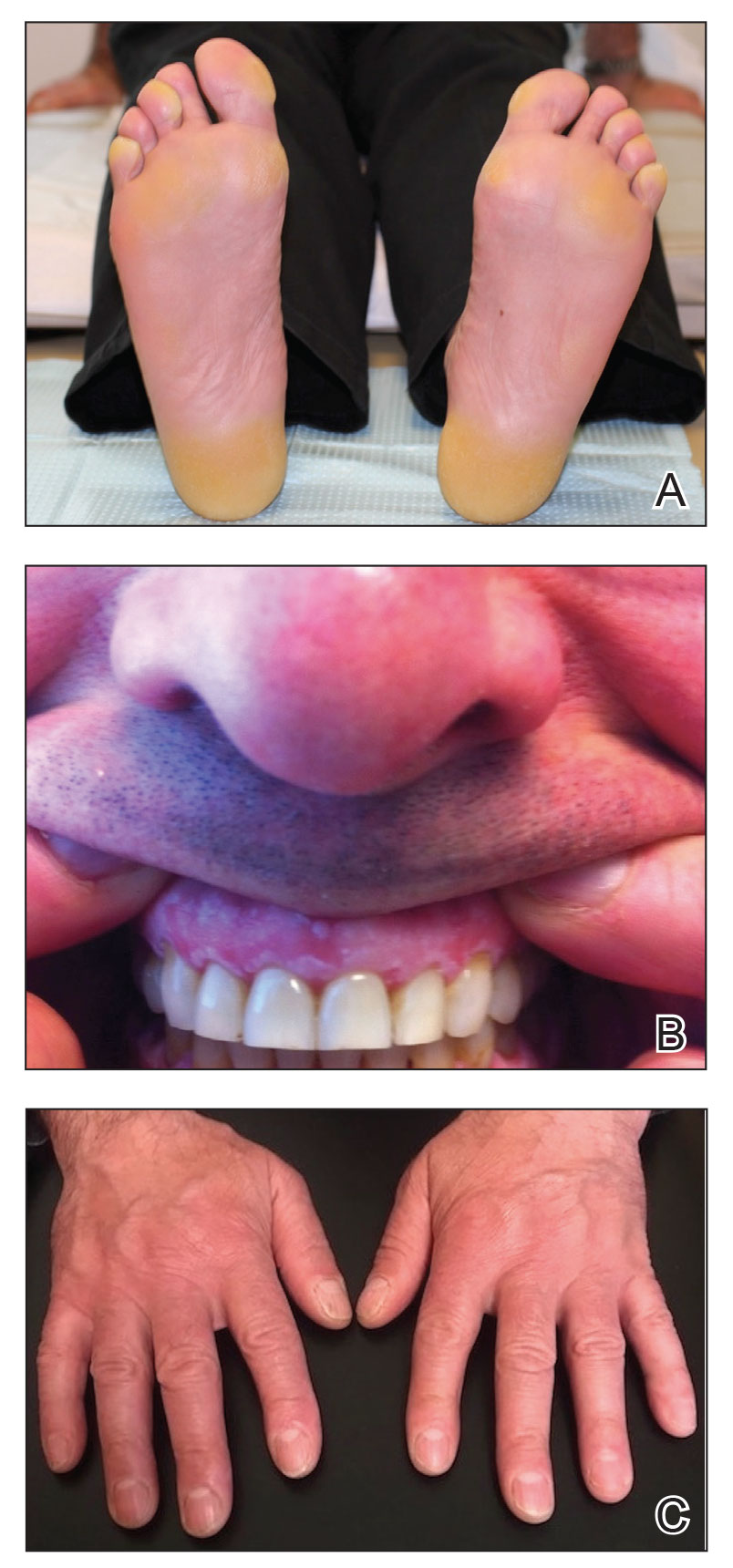

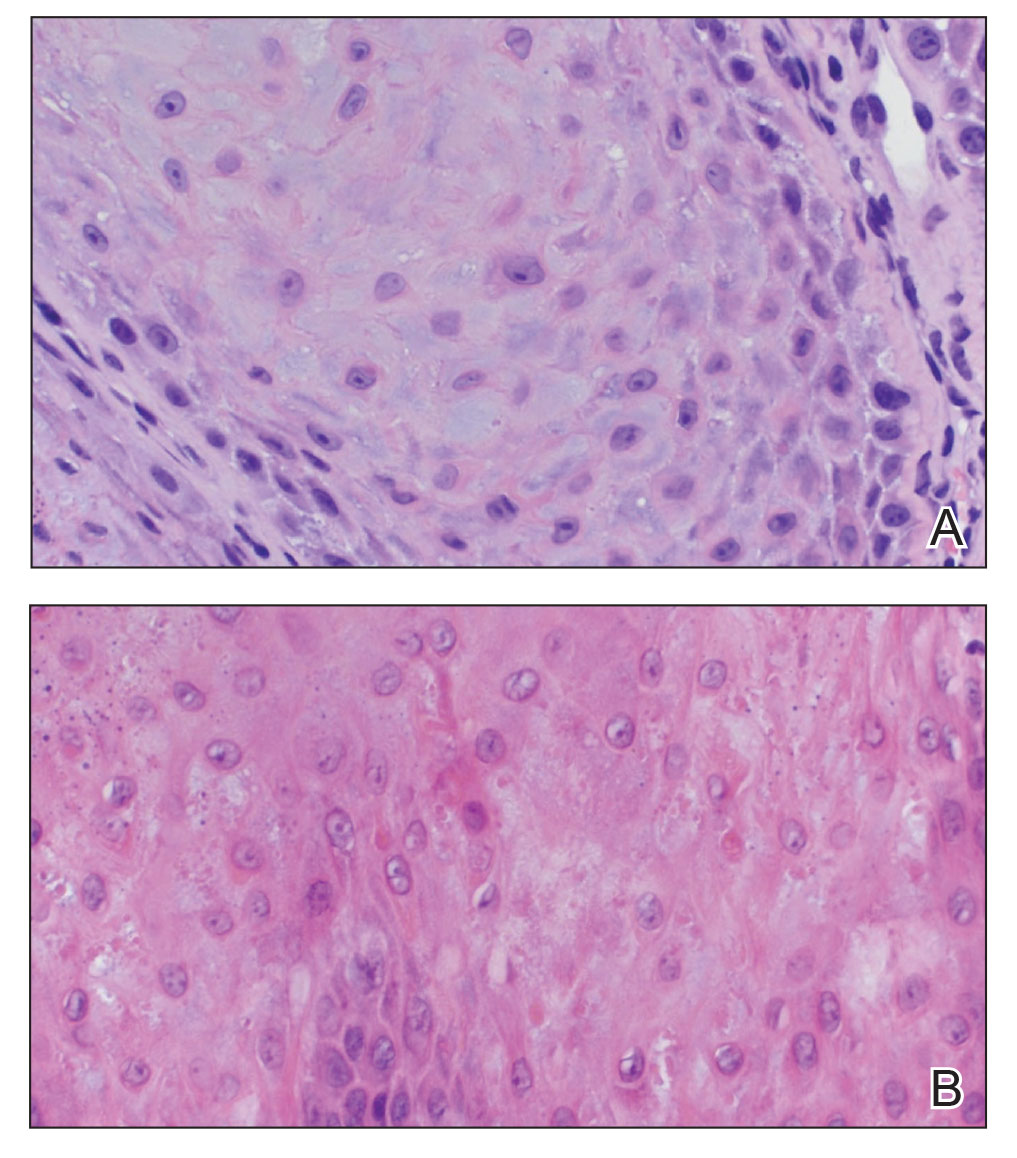

Leg lesions

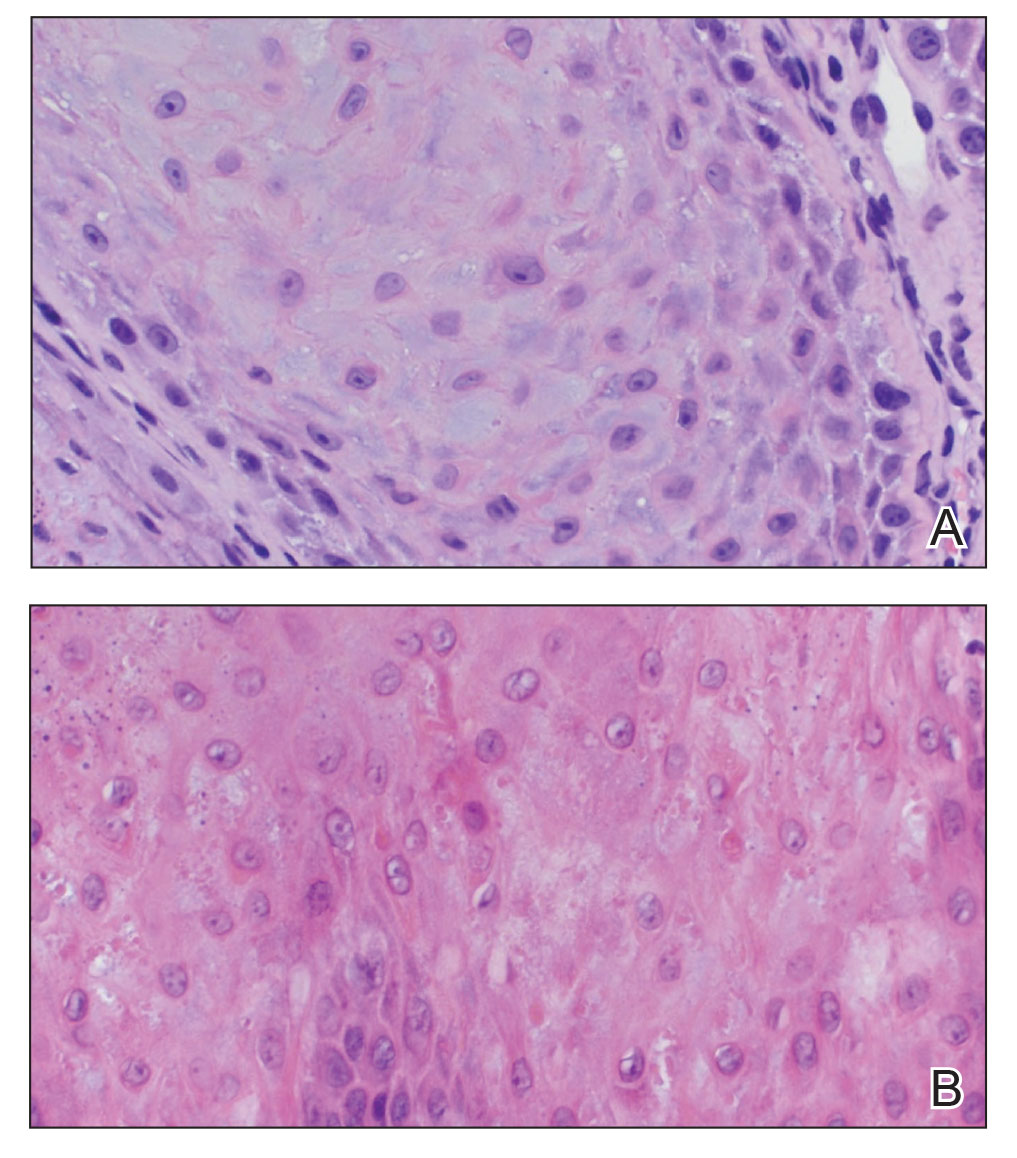

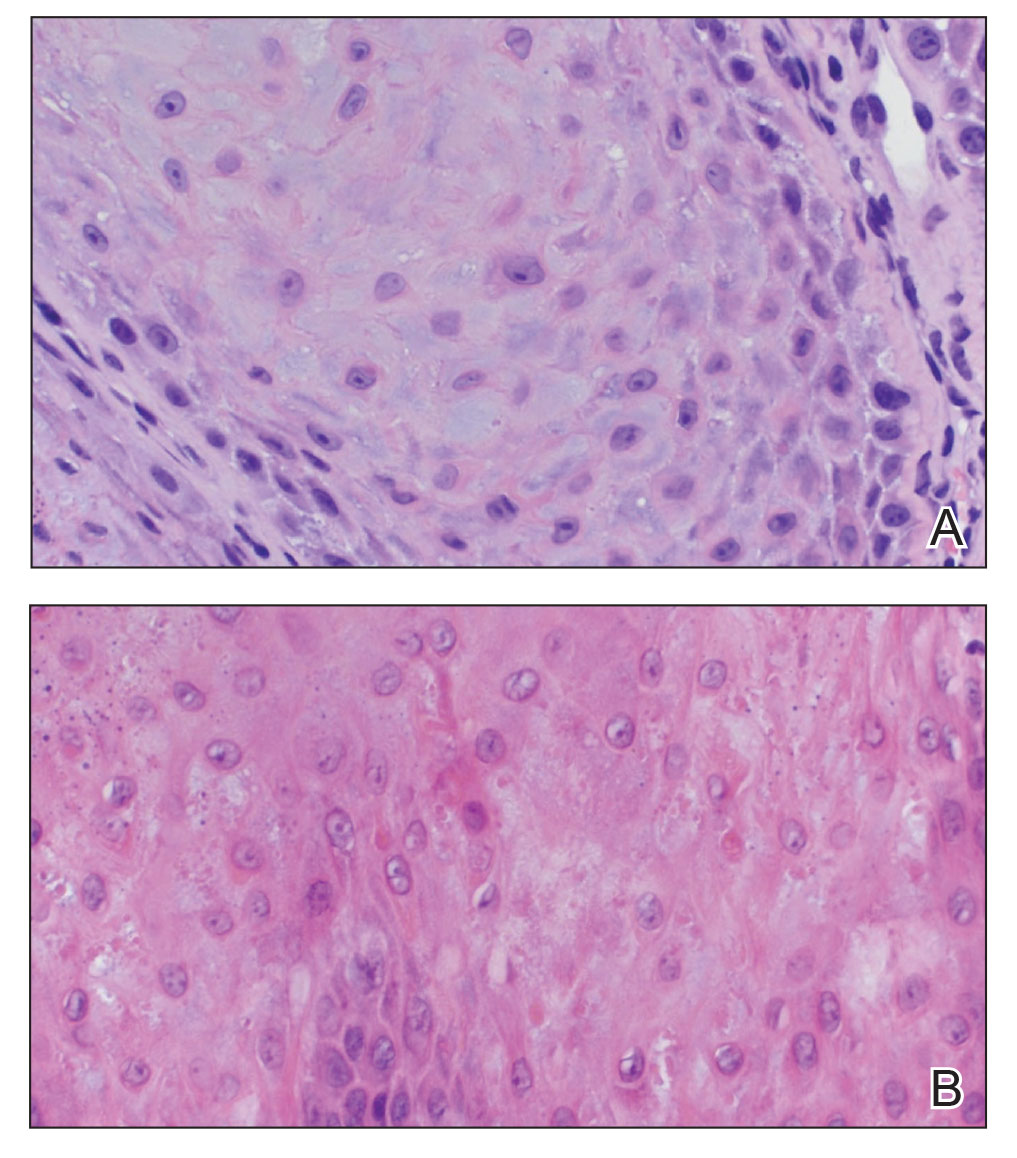

A 4-mm punch biopsy performed on the central portion of a lesion revealed thickening of the epidermis and altered collagen in the dermis consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC).

ARPC is strongly associated with diabetes, renal disease, and malignancy. ARPC manifests as an eruption of intensely pruritic papules to small plaques (with a central plug or firm dry depression) on the trunk, or more commonly, on the extremities. The etiology is unclear but altered collagen from systemic disease, trauma, or cold exposure may trigger collagen elimination.1 Secondary infection may occur due to the intensity of itching. ARPC develops in adulthood; epidemiologic data are lacking and prevalence has not been systematically assessed.2

Treatment approaches are based on small case reports and case series. Common antipruritic therapies, such as topical and intralesional steroids, oral antihistamines, and vitamin-D analogues, have had mixed success. UV therapy is effective for nephrogenic pruritus; case reports suggest it has also been helpful for ARPC. Similarly, keratolytics and topical and systemic retinoids have shown promise. Allopurinol, which reduces free radicals, has also demonstrated its utility.3

This patient was started on topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid and narrowband UV-B phototherapy 3 times weekly with marked improvement in her itching. Lesions decreased in number over 3 months of follow-up but did not completely resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Zhang X, Yang Y, Shao S. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20391. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020391

2. Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00918.x

3. Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating dermatosis - a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:825-842. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13561

A 4-mm punch biopsy performed on the central portion of a lesion revealed thickening of the epidermis and altered collagen in the dermis consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC).

ARPC is strongly associated with diabetes, renal disease, and malignancy. ARPC manifests as an eruption of intensely pruritic papules to small plaques (with a central plug or firm dry depression) on the trunk, or more commonly, on the extremities. The etiology is unclear but altered collagen from systemic disease, trauma, or cold exposure may trigger collagen elimination.1 Secondary infection may occur due to the intensity of itching. ARPC develops in adulthood; epidemiologic data are lacking and prevalence has not been systematically assessed.2

Treatment approaches are based on small case reports and case series. Common antipruritic therapies, such as topical and intralesional steroids, oral antihistamines, and vitamin-D analogues, have had mixed success. UV therapy is effective for nephrogenic pruritus; case reports suggest it has also been helpful for ARPC. Similarly, keratolytics and topical and systemic retinoids have shown promise. Allopurinol, which reduces free radicals, has also demonstrated its utility.3

This patient was started on topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid and narrowband UV-B phototherapy 3 times weekly with marked improvement in her itching. Lesions decreased in number over 3 months of follow-up but did not completely resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A 4-mm punch biopsy performed on the central portion of a lesion revealed thickening of the epidermis and altered collagen in the dermis consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC).

ARPC is strongly associated with diabetes, renal disease, and malignancy. ARPC manifests as an eruption of intensely pruritic papules to small plaques (with a central plug or firm dry depression) on the trunk, or more commonly, on the extremities. The etiology is unclear but altered collagen from systemic disease, trauma, or cold exposure may trigger collagen elimination.1 Secondary infection may occur due to the intensity of itching. ARPC develops in adulthood; epidemiologic data are lacking and prevalence has not been systematically assessed.2

Treatment approaches are based on small case reports and case series. Common antipruritic therapies, such as topical and intralesional steroids, oral antihistamines, and vitamin-D analogues, have had mixed success. UV therapy is effective for nephrogenic pruritus; case reports suggest it has also been helpful for ARPC. Similarly, keratolytics and topical and systemic retinoids have shown promise. Allopurinol, which reduces free radicals, has also demonstrated its utility.3

This patient was started on topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid and narrowband UV-B phototherapy 3 times weekly with marked improvement in her itching. Lesions decreased in number over 3 months of follow-up but did not completely resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Zhang X, Yang Y, Shao S. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20391. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020391

2. Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00918.x

3. Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating dermatosis - a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:825-842. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13561

1. Zhang X, Yang Y, Shao S. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20391. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020391

2. Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00918.x

3. Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating dermatosis - a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:825-842. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13561

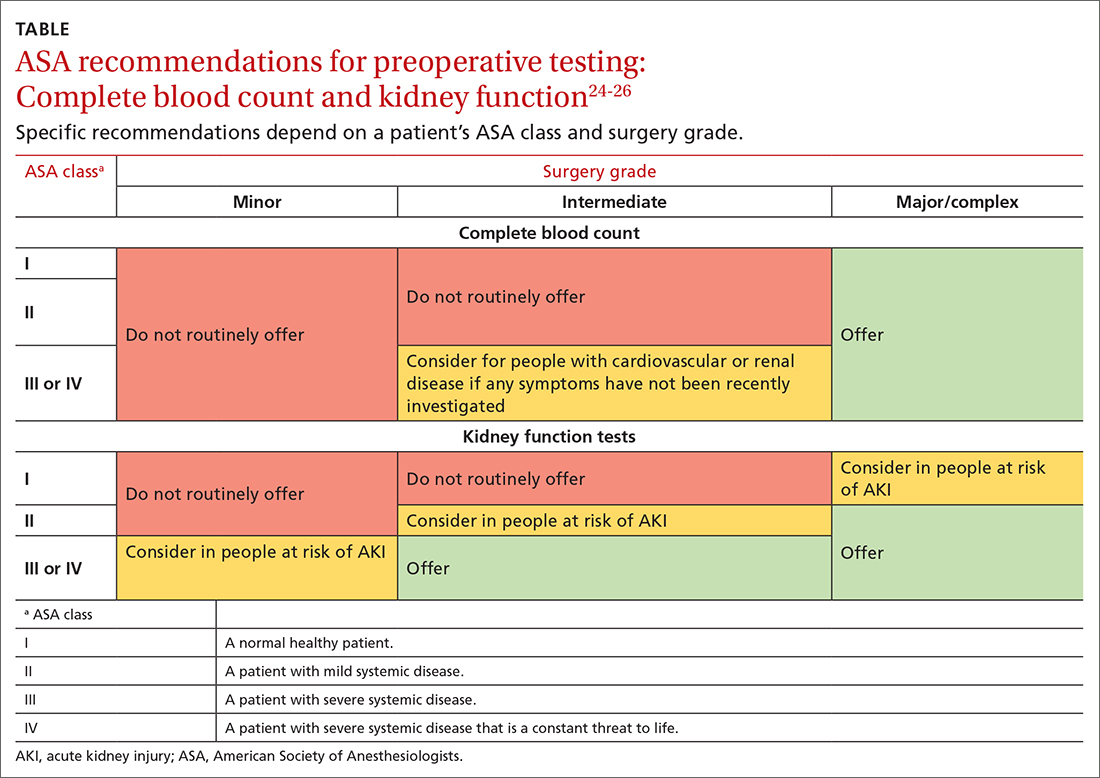

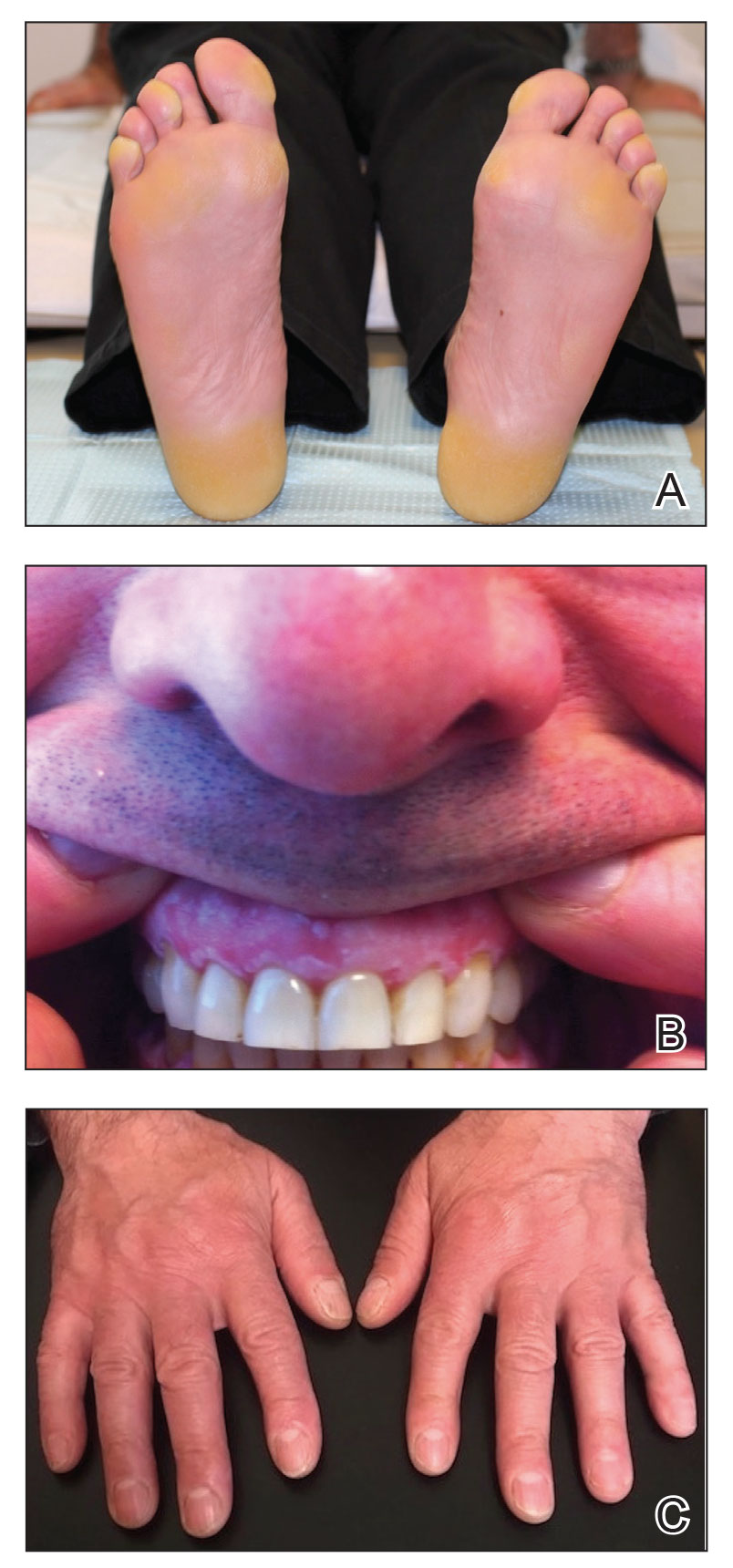

The testing we order should help, not hurt

Ordering and interpreting tests is at the heart of what we do as family physicians. Ordering tests judiciously and interpreting them accurately is not easy. The Choosing Wisely campaign1 has focused our attention on the need to think carefully before ordering tests, whether they be laboratory tests or imaging. Before ordering any test, one should always ask: Is the result of this test going to help me make better decisions about managing this patient?

I would like to highlight and expand on 2 problematic issues Kaminski and Venkat raise in their excellent article on testing in this issue of JFP.2

First, they advise us to know the pretest probability of a disease before we order a test. If we order a test on a patient for whom the probability of disease is very low, a positive result is likely to be a false-positive and mislead us into thinking the patient has the disease when he does not. If we order a test for a patient with a high probability of disease and the result is negative, there is great danger of a false-negative. We might think the patient does not have the disease, but she does.

There is a deeper problem here, however. Primary care physicians are notorious for overestimating disease probability. In a recent study, primary care clinicians overestimated the pretest probability of disease 2- to 10-fold in scenarios involving 4 common diagnoses: breast cancer, coronary artery disease (CAD), pneumonia, and urinary tract infection.3 Even after receiving a negative test result, clinicians still overestimated the chance of disease in all the scenarios. For example, when presented with a 43-year-old premenopausal woman with atypical chest pain and a normal electrocardiogram, clinicians’ average estimate of the probability of CAD was 10%—considerably higher than true estimates of 1% to 4.4%.3

To improve your accuracy in judging pretest probabilities, see the diagnostic test calculators in Essential Evidence Plus (www.essentialevidenceplus.com/).

Secondly, Kaminski and Venkat advise us to try to avoid the testing cascade.2 The associated dangers to patients are considerable. For a cautionary tale, I recommend you read the essay by Michael B. Rothberg, MD, MPH, called “The $50,000 Physical”.4 Dr. Rothberg describes the testing cascade his 85-year-old father experienced, which led to a liver biopsy that nearly killed him from post-biopsy bleeding. Always remember: Testing is a double-edged sword. It can help—or harm—your patients.

1. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. Accessed June 30, 2022. www.choosingwisely.org/

2. Kaminski M, Venkat N. A judicious approach to ordering lab tests. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:245-250. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0444

3. Morgan DJ, Pineles L, Owczarzak J, et al. Accuracy of practitioner estimates of probability of diagnosis before and after testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:747-755. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0269

4. Rothberg MB. The $50 000 physical. JAMA. 2020;323:1682-1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2866

Ordering and interpreting tests is at the heart of what we do as family physicians. Ordering tests judiciously and interpreting them accurately is not easy. The Choosing Wisely campaign1 has focused our attention on the need to think carefully before ordering tests, whether they be laboratory tests or imaging. Before ordering any test, one should always ask: Is the result of this test going to help me make better decisions about managing this patient?

I would like to highlight and expand on 2 problematic issues Kaminski and Venkat raise in their excellent article on testing in this issue of JFP.2

First, they advise us to know the pretest probability of a disease before we order a test. If we order a test on a patient for whom the probability of disease is very low, a positive result is likely to be a false-positive and mislead us into thinking the patient has the disease when he does not. If we order a test for a patient with a high probability of disease and the result is negative, there is great danger of a false-negative. We might think the patient does not have the disease, but she does.

There is a deeper problem here, however. Primary care physicians are notorious for overestimating disease probability. In a recent study, primary care clinicians overestimated the pretest probability of disease 2- to 10-fold in scenarios involving 4 common diagnoses: breast cancer, coronary artery disease (CAD), pneumonia, and urinary tract infection.3 Even after receiving a negative test result, clinicians still overestimated the chance of disease in all the scenarios. For example, when presented with a 43-year-old premenopausal woman with atypical chest pain and a normal electrocardiogram, clinicians’ average estimate of the probability of CAD was 10%—considerably higher than true estimates of 1% to 4.4%.3

To improve your accuracy in judging pretest probabilities, see the diagnostic test calculators in Essential Evidence Plus (www.essentialevidenceplus.com/).

Secondly, Kaminski and Venkat advise us to try to avoid the testing cascade.2 The associated dangers to patients are considerable. For a cautionary tale, I recommend you read the essay by Michael B. Rothberg, MD, MPH, called “The $50,000 Physical”.4 Dr. Rothberg describes the testing cascade his 85-year-old father experienced, which led to a liver biopsy that nearly killed him from post-biopsy bleeding. Always remember: Testing is a double-edged sword. It can help—or harm—your patients.

Ordering and interpreting tests is at the heart of what we do as family physicians. Ordering tests judiciously and interpreting them accurately is not easy. The Choosing Wisely campaign1 has focused our attention on the need to think carefully before ordering tests, whether they be laboratory tests or imaging. Before ordering any test, one should always ask: Is the result of this test going to help me make better decisions about managing this patient?

I would like to highlight and expand on 2 problematic issues Kaminski and Venkat raise in their excellent article on testing in this issue of JFP.2

First, they advise us to know the pretest probability of a disease before we order a test. If we order a test on a patient for whom the probability of disease is very low, a positive result is likely to be a false-positive and mislead us into thinking the patient has the disease when he does not. If we order a test for a patient with a high probability of disease and the result is negative, there is great danger of a false-negative. We might think the patient does not have the disease, but she does.