User login

Dupilumab Effective in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis and Comorbidities Including Malignancies

Key clinical point: In real-world settings, dupilumab is safe and leads to significant and sustained improvements in the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with malignancies and other comorbidities.

Major finding: At week 52, 64% of patients showed a decrease in disease severity, achieving a Physician Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 compared with a score of 3 or 4 at baseline. No adverse effect on current malignancy or recurrence of prior malignancy was reported with dupilumab use.

Study details: This real-world retrospective study analyzed the data of 155 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with other significant comorbidities like malignancies, who were treated with dupilumab.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Mohannad Abu-Hilal declared serving as an advisor, consultant, or speaker for or receiving grants or honoraria from various sources.

Source: Metko D, Alkofide M, Abu-Hilal M. A real-world study of dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis including patients with malignancy and other medical comorbidities. JAAD Int. 2024;15:5-11 (Jan 15). doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2024.01.002 Source

Key clinical point: In real-world settings, dupilumab is safe and leads to significant and sustained improvements in the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with malignancies and other comorbidities.

Major finding: At week 52, 64% of patients showed a decrease in disease severity, achieving a Physician Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 compared with a score of 3 or 4 at baseline. No adverse effect on current malignancy or recurrence of prior malignancy was reported with dupilumab use.

Study details: This real-world retrospective study analyzed the data of 155 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with other significant comorbidities like malignancies, who were treated with dupilumab.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Mohannad Abu-Hilal declared serving as an advisor, consultant, or speaker for or receiving grants or honoraria from various sources.

Source: Metko D, Alkofide M, Abu-Hilal M. A real-world study of dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis including patients with malignancy and other medical comorbidities. JAAD Int. 2024;15:5-11 (Jan 15). doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2024.01.002 Source

Key clinical point: In real-world settings, dupilumab is safe and leads to significant and sustained improvements in the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with malignancies and other comorbidities.

Major finding: At week 52, 64% of patients showed a decrease in disease severity, achieving a Physician Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 compared with a score of 3 or 4 at baseline. No adverse effect on current malignancy or recurrence of prior malignancy was reported with dupilumab use.

Study details: This real-world retrospective study analyzed the data of 155 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with other significant comorbidities like malignancies, who were treated with dupilumab.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Mohannad Abu-Hilal declared serving as an advisor, consultant, or speaker for or receiving grants or honoraria from various sources.

Source: Metko D, Alkofide M, Abu-Hilal M. A real-world study of dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis including patients with malignancy and other medical comorbidities. JAAD Int. 2024;15:5-11 (Jan 15). doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2024.01.002 Source

Atopic Dermatitis Remission in Children Unaffected by Washing With Water or Cleanser During Summer

Key clinical point: Skin care by washing with water alone is not inferior to washing with a cleanser for the maintenance of remission in children with atopic dermatitis (AD) during the summer.

Major finding: The mean modified Eczema Area and Severity Index scores at 8 ± 4 weeks were similar in children who washed their upper and lower limbs with water and those who used a cleanser (0.00 and 0.15, respectively; P = .74). No difference was observed in the occurrence of skin infection, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, and other secondary outcomes with water vs cleanser use (all P > .05).

Study details: This noninferiority study included 43 children (age < 15 years) with AD having controlled eczema following regular steroid ointment application, who washed the randomly assigned left or right limb with a cleanser and the other limb with water alone.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Maruho Scholarship Donations Support Program, Japan. Osamu Natsume declared receiving grants from several sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Katoh Y, Natsume O, Yasuoka R, et al. Skin care by washing with water is not inferior to washing with a cleanser in children with atopic dermatitis in remission in summer: WASH study. Allergol Int. 2024 (Feb 2). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2024.01.007 Source

Key clinical point: Skin care by washing with water alone is not inferior to washing with a cleanser for the maintenance of remission in children with atopic dermatitis (AD) during the summer.

Major finding: The mean modified Eczema Area and Severity Index scores at 8 ± 4 weeks were similar in children who washed their upper and lower limbs with water and those who used a cleanser (0.00 and 0.15, respectively; P = .74). No difference was observed in the occurrence of skin infection, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, and other secondary outcomes with water vs cleanser use (all P > .05).

Study details: This noninferiority study included 43 children (age < 15 years) with AD having controlled eczema following regular steroid ointment application, who washed the randomly assigned left or right limb with a cleanser and the other limb with water alone.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Maruho Scholarship Donations Support Program, Japan. Osamu Natsume declared receiving grants from several sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Katoh Y, Natsume O, Yasuoka R, et al. Skin care by washing with water is not inferior to washing with a cleanser in children with atopic dermatitis in remission in summer: WASH study. Allergol Int. 2024 (Feb 2). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2024.01.007 Source

Key clinical point: Skin care by washing with water alone is not inferior to washing with a cleanser for the maintenance of remission in children with atopic dermatitis (AD) during the summer.

Major finding: The mean modified Eczema Area and Severity Index scores at 8 ± 4 weeks were similar in children who washed their upper and lower limbs with water and those who used a cleanser (0.00 and 0.15, respectively; P = .74). No difference was observed in the occurrence of skin infection, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, and other secondary outcomes with water vs cleanser use (all P > .05).

Study details: This noninferiority study included 43 children (age < 15 years) with AD having controlled eczema following regular steroid ointment application, who washed the randomly assigned left or right limb with a cleanser and the other limb with water alone.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Maruho Scholarship Donations Support Program, Japan. Osamu Natsume declared receiving grants from several sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Katoh Y, Natsume O, Yasuoka R, et al. Skin care by washing with water is not inferior to washing with a cleanser in children with atopic dermatitis in remission in summer: WASH study. Allergol Int. 2024 (Feb 2). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2024.01.007 Source

Air Quality Index Tied to the Incidence of Atopic Dermatitis

Key clinical point: A significant positive, dose-dependent association was observed between air quality index (AQI) and the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: The participants were classified into four AQI value quantiles (Q), with the mean AQI values from the lowest Q1 to the highest Q4 being 69.0, 78.9, 89.8, and 104.0, respectively. Compared with Q1, the risk for AD increased significantly in Q2 (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.29; 95% CI 1.04-1.65), Q3 (aHR 4.71; 95% CI 3.78-6.04), and Q4 (aHR 13.20; 95% CI 10.86-16.60). An increase of one unit in the AQI value increased the risk for AD by 7%.

Study details: This cohort study included 21,278,938 individuals without AD, with the long-term average AQI value before AD diagnosis being calculated and linked for each of the individuals.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, Republic of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu CY, Wu CY, Li MC, Ho HJ, Ao CK. Association of air quality index (AQI) with incidence of atopic dermatitis in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024 (Feb 1). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.01.058 Source

Key clinical point: A significant positive, dose-dependent association was observed between air quality index (AQI) and the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: The participants were classified into four AQI value quantiles (Q), with the mean AQI values from the lowest Q1 to the highest Q4 being 69.0, 78.9, 89.8, and 104.0, respectively. Compared with Q1, the risk for AD increased significantly in Q2 (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.29; 95% CI 1.04-1.65), Q3 (aHR 4.71; 95% CI 3.78-6.04), and Q4 (aHR 13.20; 95% CI 10.86-16.60). An increase of one unit in the AQI value increased the risk for AD by 7%.

Study details: This cohort study included 21,278,938 individuals without AD, with the long-term average AQI value before AD diagnosis being calculated and linked for each of the individuals.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, Republic of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu CY, Wu CY, Li MC, Ho HJ, Ao CK. Association of air quality index (AQI) with incidence of atopic dermatitis in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024 (Feb 1). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.01.058 Source

Key clinical point: A significant positive, dose-dependent association was observed between air quality index (AQI) and the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: The participants were classified into four AQI value quantiles (Q), with the mean AQI values from the lowest Q1 to the highest Q4 being 69.0, 78.9, 89.8, and 104.0, respectively. Compared with Q1, the risk for AD increased significantly in Q2 (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.29; 95% CI 1.04-1.65), Q3 (aHR 4.71; 95% CI 3.78-6.04), and Q4 (aHR 13.20; 95% CI 10.86-16.60). An increase of one unit in the AQI value increased the risk for AD by 7%.

Study details: This cohort study included 21,278,938 individuals without AD, with the long-term average AQI value before AD diagnosis being calculated and linked for each of the individuals.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, Republic of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu CY, Wu CY, Li MC, Ho HJ, Ao CK. Association of air quality index (AQI) with incidence of atopic dermatitis in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024 (Feb 1). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.01.058 Source

Dupilumab Monotherapy Safe and Effective Against Hand and Foot Atopic Dermatitis

Key clinical point: Dupilumab monotherapy is safe and leads to rapid and significant improvements in disease signs and symptoms in patients with hand and foot (HF) atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, a significantly higher number of patients receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved an HF Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (P = .003) and ≥4-point reduction in HF Peak Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale score (P < .0001), with the difference between groups evident from weeks 4 and 1, respectively. Safety was consistent with the known dupilumab profile.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 LIBERTY-AD-HAFT study, which included 106 adults and 27 adolescents (≥ 12 to < 18 years) with moderate to severe HF AD who were randomized (1:1) to receive dupilumab or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Ten authors declared being employees or shareholders of Sanofi or Regeneron. The remaining authors, except Ewa Sygula, declared serving as investigators, consultants, etc., for or receiving personal fees, grants, honoraria, etc., from Sanofi, Regeneron, or others.

Source: Simpson E, Silverberg JI, Worm M, et al. Dupilumab treatment improves signs, symptoms, quality of life and work productivity in patients with atopic hand and foot dermatitis: Results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024 (Jan 29). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.066 Source

Key clinical point: Dupilumab monotherapy is safe and leads to rapid and significant improvements in disease signs and symptoms in patients with hand and foot (HF) atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, a significantly higher number of patients receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved an HF Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (P = .003) and ≥4-point reduction in HF Peak Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale score (P < .0001), with the difference between groups evident from weeks 4 and 1, respectively. Safety was consistent with the known dupilumab profile.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 LIBERTY-AD-HAFT study, which included 106 adults and 27 adolescents (≥ 12 to < 18 years) with moderate to severe HF AD who were randomized (1:1) to receive dupilumab or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Ten authors declared being employees or shareholders of Sanofi or Regeneron. The remaining authors, except Ewa Sygula, declared serving as investigators, consultants, etc., for or receiving personal fees, grants, honoraria, etc., from Sanofi, Regeneron, or others.

Source: Simpson E, Silverberg JI, Worm M, et al. Dupilumab treatment improves signs, symptoms, quality of life and work productivity in patients with atopic hand and foot dermatitis: Results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024 (Jan 29). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.066 Source

Key clinical point: Dupilumab monotherapy is safe and leads to rapid and significant improvements in disease signs and symptoms in patients with hand and foot (HF) atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, a significantly higher number of patients receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved an HF Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (P = .003) and ≥4-point reduction in HF Peak Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale score (P < .0001), with the difference between groups evident from weeks 4 and 1, respectively. Safety was consistent with the known dupilumab profile.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 LIBERTY-AD-HAFT study, which included 106 adults and 27 adolescents (≥ 12 to < 18 years) with moderate to severe HF AD who were randomized (1:1) to receive dupilumab or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Ten authors declared being employees or shareholders of Sanofi or Regeneron. The remaining authors, except Ewa Sygula, declared serving as investigators, consultants, etc., for or receiving personal fees, grants, honoraria, etc., from Sanofi, Regeneron, or others.

Source: Simpson E, Silverberg JI, Worm M, et al. Dupilumab treatment improves signs, symptoms, quality of life and work productivity in patients with atopic hand and foot dermatitis: Results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024 (Jan 29). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.066 Source

Atopic Dermatitis Increases the Risk for Subsequent Autoimmune Disease

Key clinical point: A significant causal relationship was observed between atopic dermatitis (AD) and autoimmune diseases in children, and this was supported by the presence of shared genetic factors.

Major finding: At a follow-up of 12 years, children with vs without AD had a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; 95% CI 1.23-1.32), particularly psoriasis vulgaris (aHR 2.55; 95% CI 2.25-2.80). Boys were significantly more susceptible to autoimmune diseases than girls (P for interaction = .04). Sixteen shared genes were identified between AD and autoimmune diseases and were associated with comorbidities, such as asthma and bronchiolitis.

Study details: This large-scale cohort study included 39,832 children with AD born between 2002 and 2018, who were matched with 159,328 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Ahn J, Shin S, Lee GC, et al. Unraveling the link between atopic dermatitis and autoimmune diseases in children: Insights from a large-scale cohort study with 15-year follow-up and shared gene ontology analysis. Allergol Int. 2024 (Jan 17). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2023.12.005 Source

Key clinical point: A significant causal relationship was observed between atopic dermatitis (AD) and autoimmune diseases in children, and this was supported by the presence of shared genetic factors.

Major finding: At a follow-up of 12 years, children with vs without AD had a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; 95% CI 1.23-1.32), particularly psoriasis vulgaris (aHR 2.55; 95% CI 2.25-2.80). Boys were significantly more susceptible to autoimmune diseases than girls (P for interaction = .04). Sixteen shared genes were identified between AD and autoimmune diseases and were associated with comorbidities, such as asthma and bronchiolitis.

Study details: This large-scale cohort study included 39,832 children with AD born between 2002 and 2018, who were matched with 159,328 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Ahn J, Shin S, Lee GC, et al. Unraveling the link between atopic dermatitis and autoimmune diseases in children: Insights from a large-scale cohort study with 15-year follow-up and shared gene ontology analysis. Allergol Int. 2024 (Jan 17). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2023.12.005 Source

Key clinical point: A significant causal relationship was observed between atopic dermatitis (AD) and autoimmune diseases in children, and this was supported by the presence of shared genetic factors.

Major finding: At a follow-up of 12 years, children with vs without AD had a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; 95% CI 1.23-1.32), particularly psoriasis vulgaris (aHR 2.55; 95% CI 2.25-2.80). Boys were significantly more susceptible to autoimmune diseases than girls (P for interaction = .04). Sixteen shared genes were identified between AD and autoimmune diseases and were associated with comorbidities, such as asthma and bronchiolitis.

Study details: This large-scale cohort study included 39,832 children with AD born between 2002 and 2018, who were matched with 159,328 children without AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Ahn J, Shin S, Lee GC, et al. Unraveling the link between atopic dermatitis and autoimmune diseases in children: Insights from a large-scale cohort study with 15-year follow-up and shared gene ontology analysis. Allergol Int. 2024 (Jan 17). doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2023.12.005 Source

Alagille Syndrome

In this article Alisha Mavis, MD, discusses the prevalence, diagnosis, challenges, and management of patients with this Alagille Syndrome, as well as the need for a multidisciplinary approach to care.

In this article Alisha Mavis, MD, discusses the prevalence, diagnosis, challenges, and management of patients with this Alagille Syndrome, as well as the need for a multidisciplinary approach to care.

In this article Alisha Mavis, MD, discusses the prevalence, diagnosis, challenges, and management of patients with this Alagille Syndrome, as well as the need for a multidisciplinary approach to care.

An Ethical Analysis of Treatment of an Active-Duty Service Member With Limited Follow-up

For active-duty service members, dermatologic conditions are among the most common presenting concerns, comprising 15% to 75% of wartime outpatient visits.1 In general, there are unique considerations when caring for active-duty service members, including meeting designated active-duty retention and hierarchical standards.2 We present a hypothetical case: An active-duty military patient presents to a new dermatologist for cosmetic enhancement of facial skin dyspigmentation. The patient will be leaving soon for deployment and will not be able to follow up for 9 months. How should the dermatologist treat a patient who cannot follow up for so long?

The therapeutic modalities offered can be impacted by forthcoming deployments3 that may result in delayed time to administer repeat treatments or follow-up. The patient may have high expectations for a single appointment for a condition that requires prolonged treatment courses. Because there often is no reliable mechanism for patients to obtain refills during deployment, any medications prescribed would need to be provided in advance for the entire deployment duration, which often is 6 to 9 months. Additionally, treatment monitoring or modifications are severely limited, especially in the context of treatment nonresponse or adverse reactions. Considering the unique limitations of this patient population, both military and civilian physicians are faced with a need to maximize beneficence and autonomy while balancing nonmaleficence and justice.

One possible option is to decline to treat until the patient can follow up after returning from deployment. However, denying a request for an active treatable indication for which the patient desires treatment compromises patient autonomy and beneficence. Further, treatment should be provided to patients equitably to maintain justice. Although there may be a role for discussing active monitoring with nonintervention with the patient, denying treatment can negatively impact their physical and mental health and may be harmful. However, the patient should know and fully understand the risks and benefits of nonintervention with limited follow-up, including suboptimal outcomes or adverse events.

Another possibility for the management of this case may be conducting a one-time laser or light-based therapy or a one-time superficial- to medium-depth chemical peel before the patient leaves on deployment. Often, a series of laser- or light-based treatments is required to maximize outcomes for dyspigmentation. Without follow-up and with possible deployment to an environment with high UV exposure, the patient may experience disease exacerbation or other adverse effects. Treatment of those adverse effects may be delayed, as further intervention is not possible during deployment. Lower initial laser settings may be safer but may not be highly effective initially. More rigorous treatment upon return from deployment may be considered. Similar to laser therapies, chemical peels usually require several treatments for optimal outcomes. Without follow-up and with potential deployment to remote environments, there is a risk for adverse events that outweighs the minimal benefit of a single treatment. Therefore, either intervention may violate the principle of nonmaleficence.

A more reasonable approach may be initiating topical therapy and following up via telemedicine evaluation. Topical therapy often is the least-invasive approach and carries a reduced risk for adverse effects. Triple-combination therapy with topical retinoids, hydroquinone, and topical steroids is a common first-line approach.4 Because this approach is patient dependent, therapy can be more easily modulated or halted in the context of undesired results. Additionally, if internet connectivity is available, an asynchronous telemedicine approach could be utilized during deployment to monitor and advise changes as necessary, provided the regulatory framework allows for it.5

Although there is no uniformly correct approach in a scenario of limited patient follow-up, the last solution may be most ethically favorable: to begin therapy with milder and safer therapies (topical) and defer higher-intensity regimens until the patient returns from deployment. This allows some treatment initiation to preserve justice, beneficence, and patient autonomy. Associated virtual follow-up via telemedicine also allows avoidance of nonmaleficence in this context.

- Hwang J, Kakimoto C. Teledermatology in the US military: a historic foundation for current and future applications. Cutis. 2018;101:335;337;345.

- Dodd JG, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical concerns in caring for active duty service members who may be seeking dermatologic care outside the military soon. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:445-447. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.001

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment consideration for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019;103:329-332.

- Desai SR. Hyperpigmentation therapy: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:13-17.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00115

For active-duty service members, dermatologic conditions are among the most common presenting concerns, comprising 15% to 75% of wartime outpatient visits.1 In general, there are unique considerations when caring for active-duty service members, including meeting designated active-duty retention and hierarchical standards.2 We present a hypothetical case: An active-duty military patient presents to a new dermatologist for cosmetic enhancement of facial skin dyspigmentation. The patient will be leaving soon for deployment and will not be able to follow up for 9 months. How should the dermatologist treat a patient who cannot follow up for so long?

The therapeutic modalities offered can be impacted by forthcoming deployments3 that may result in delayed time to administer repeat treatments or follow-up. The patient may have high expectations for a single appointment for a condition that requires prolonged treatment courses. Because there often is no reliable mechanism for patients to obtain refills during deployment, any medications prescribed would need to be provided in advance for the entire deployment duration, which often is 6 to 9 months. Additionally, treatment monitoring or modifications are severely limited, especially in the context of treatment nonresponse or adverse reactions. Considering the unique limitations of this patient population, both military and civilian physicians are faced with a need to maximize beneficence and autonomy while balancing nonmaleficence and justice.

One possible option is to decline to treat until the patient can follow up after returning from deployment. However, denying a request for an active treatable indication for which the patient desires treatment compromises patient autonomy and beneficence. Further, treatment should be provided to patients equitably to maintain justice. Although there may be a role for discussing active monitoring with nonintervention with the patient, denying treatment can negatively impact their physical and mental health and may be harmful. However, the patient should know and fully understand the risks and benefits of nonintervention with limited follow-up, including suboptimal outcomes or adverse events.

Another possibility for the management of this case may be conducting a one-time laser or light-based therapy or a one-time superficial- to medium-depth chemical peel before the patient leaves on deployment. Often, a series of laser- or light-based treatments is required to maximize outcomes for dyspigmentation. Without follow-up and with possible deployment to an environment with high UV exposure, the patient may experience disease exacerbation or other adverse effects. Treatment of those adverse effects may be delayed, as further intervention is not possible during deployment. Lower initial laser settings may be safer but may not be highly effective initially. More rigorous treatment upon return from deployment may be considered. Similar to laser therapies, chemical peels usually require several treatments for optimal outcomes. Without follow-up and with potential deployment to remote environments, there is a risk for adverse events that outweighs the minimal benefit of a single treatment. Therefore, either intervention may violate the principle of nonmaleficence.

A more reasonable approach may be initiating topical therapy and following up via telemedicine evaluation. Topical therapy often is the least-invasive approach and carries a reduced risk for adverse effects. Triple-combination therapy with topical retinoids, hydroquinone, and topical steroids is a common first-line approach.4 Because this approach is patient dependent, therapy can be more easily modulated or halted in the context of undesired results. Additionally, if internet connectivity is available, an asynchronous telemedicine approach could be utilized during deployment to monitor and advise changes as necessary, provided the regulatory framework allows for it.5

Although there is no uniformly correct approach in a scenario of limited patient follow-up, the last solution may be most ethically favorable: to begin therapy with milder and safer therapies (topical) and defer higher-intensity regimens until the patient returns from deployment. This allows some treatment initiation to preserve justice, beneficence, and patient autonomy. Associated virtual follow-up via telemedicine also allows avoidance of nonmaleficence in this context.

For active-duty service members, dermatologic conditions are among the most common presenting concerns, comprising 15% to 75% of wartime outpatient visits.1 In general, there are unique considerations when caring for active-duty service members, including meeting designated active-duty retention and hierarchical standards.2 We present a hypothetical case: An active-duty military patient presents to a new dermatologist for cosmetic enhancement of facial skin dyspigmentation. The patient will be leaving soon for deployment and will not be able to follow up for 9 months. How should the dermatologist treat a patient who cannot follow up for so long?

The therapeutic modalities offered can be impacted by forthcoming deployments3 that may result in delayed time to administer repeat treatments or follow-up. The patient may have high expectations for a single appointment for a condition that requires prolonged treatment courses. Because there often is no reliable mechanism for patients to obtain refills during deployment, any medications prescribed would need to be provided in advance for the entire deployment duration, which often is 6 to 9 months. Additionally, treatment monitoring or modifications are severely limited, especially in the context of treatment nonresponse or adverse reactions. Considering the unique limitations of this patient population, both military and civilian physicians are faced with a need to maximize beneficence and autonomy while balancing nonmaleficence and justice.

One possible option is to decline to treat until the patient can follow up after returning from deployment. However, denying a request for an active treatable indication for which the patient desires treatment compromises patient autonomy and beneficence. Further, treatment should be provided to patients equitably to maintain justice. Although there may be a role for discussing active monitoring with nonintervention with the patient, denying treatment can negatively impact their physical and mental health and may be harmful. However, the patient should know and fully understand the risks and benefits of nonintervention with limited follow-up, including suboptimal outcomes or adverse events.

Another possibility for the management of this case may be conducting a one-time laser or light-based therapy or a one-time superficial- to medium-depth chemical peel before the patient leaves on deployment. Often, a series of laser- or light-based treatments is required to maximize outcomes for dyspigmentation. Without follow-up and with possible deployment to an environment with high UV exposure, the patient may experience disease exacerbation or other adverse effects. Treatment of those adverse effects may be delayed, as further intervention is not possible during deployment. Lower initial laser settings may be safer but may not be highly effective initially. More rigorous treatment upon return from deployment may be considered. Similar to laser therapies, chemical peels usually require several treatments for optimal outcomes. Without follow-up and with potential deployment to remote environments, there is a risk for adverse events that outweighs the minimal benefit of a single treatment. Therefore, either intervention may violate the principle of nonmaleficence.

A more reasonable approach may be initiating topical therapy and following up via telemedicine evaluation. Topical therapy often is the least-invasive approach and carries a reduced risk for adverse effects. Triple-combination therapy with topical retinoids, hydroquinone, and topical steroids is a common first-line approach.4 Because this approach is patient dependent, therapy can be more easily modulated or halted in the context of undesired results. Additionally, if internet connectivity is available, an asynchronous telemedicine approach could be utilized during deployment to monitor and advise changes as necessary, provided the regulatory framework allows for it.5

Although there is no uniformly correct approach in a scenario of limited patient follow-up, the last solution may be most ethically favorable: to begin therapy with milder and safer therapies (topical) and defer higher-intensity regimens until the patient returns from deployment. This allows some treatment initiation to preserve justice, beneficence, and patient autonomy. Associated virtual follow-up via telemedicine also allows avoidance of nonmaleficence in this context.

- Hwang J, Kakimoto C. Teledermatology in the US military: a historic foundation for current and future applications. Cutis. 2018;101:335;337;345.

- Dodd JG, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical concerns in caring for active duty service members who may be seeking dermatologic care outside the military soon. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:445-447. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.001

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment consideration for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019;103:329-332.

- Desai SR. Hyperpigmentation therapy: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:13-17.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00115

- Hwang J, Kakimoto C. Teledermatology in the US military: a historic foundation for current and future applications. Cutis. 2018;101:335;337;345.

- Dodd JG, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical concerns in caring for active duty service members who may be seeking dermatologic care outside the military soon. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:445-447. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.07.001

- Burke KR, Larrymore DC, Cho S. Treatment consideration for US military members with skin disease. Cutis. 2019;103:329-332.

- Desai SR. Hyperpigmentation therapy: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:13-17.

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00115

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologic conditions are among the most common concerns reported by active-duty service members.

- The unique considerations of deployments are important for dermatologists to consider in the treatment of skin disease.

Migraine Variants

Nonepidemic Kaposi Sarcoma: A Case of a Rare Epidemiologic Subtype

To the Editor:

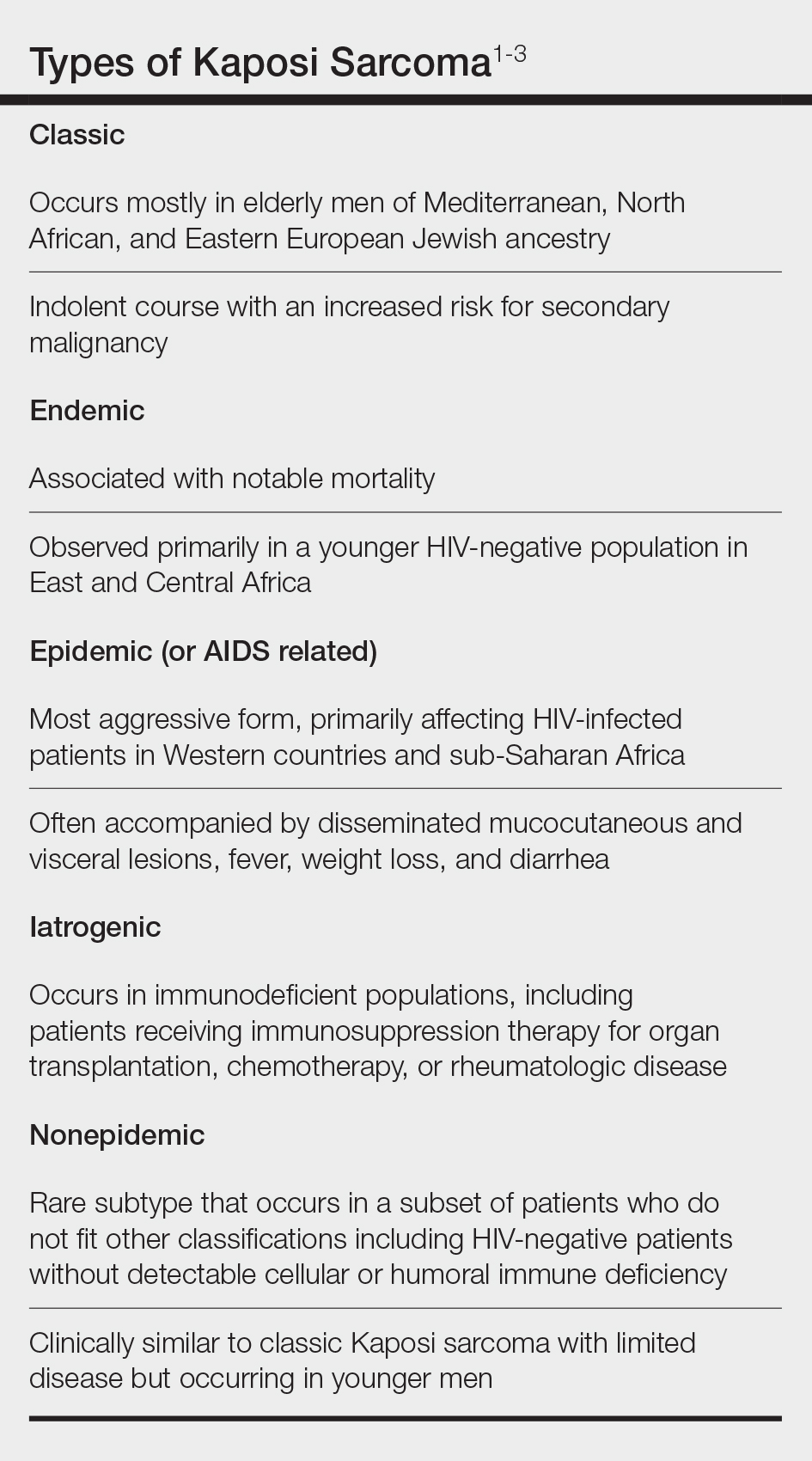

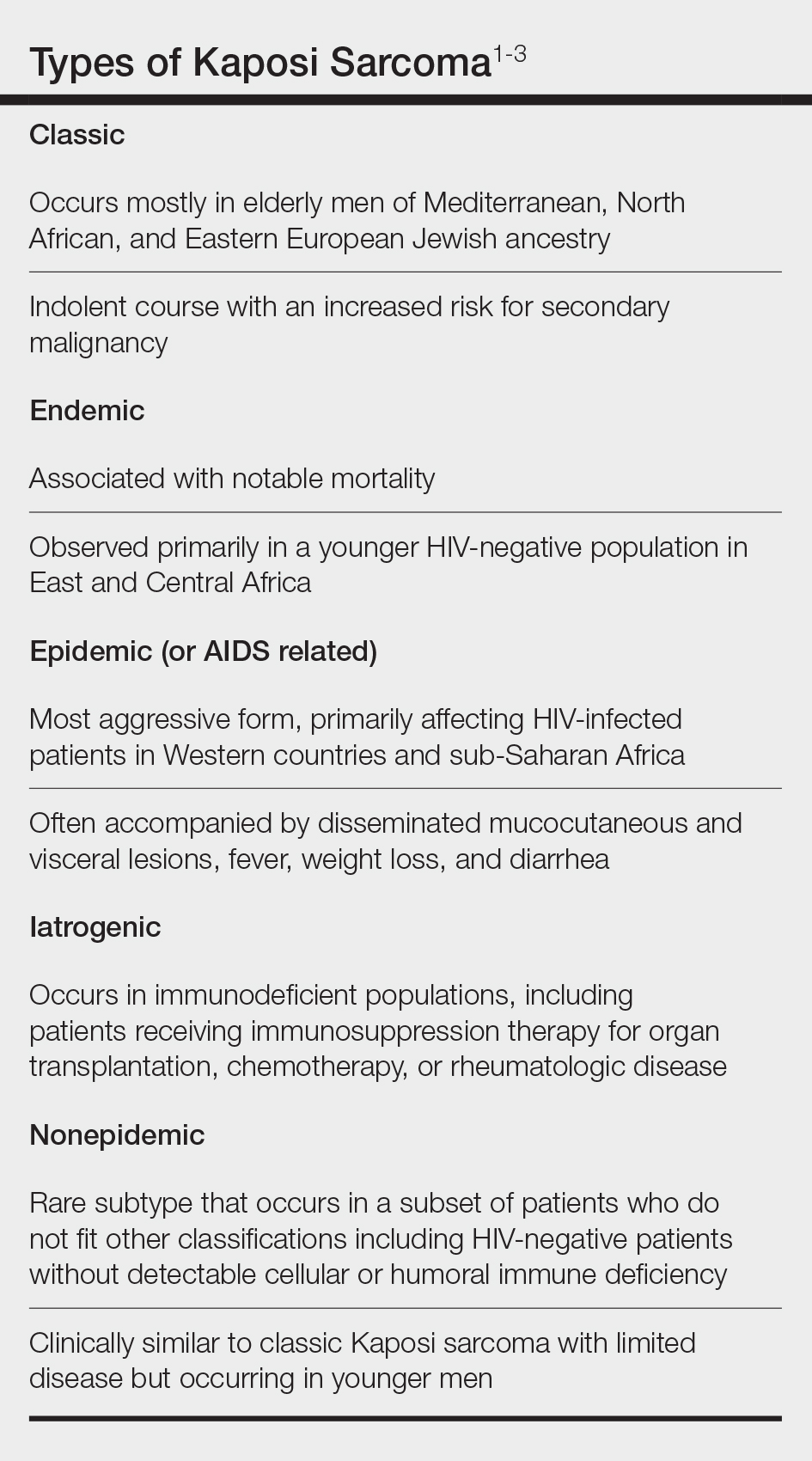

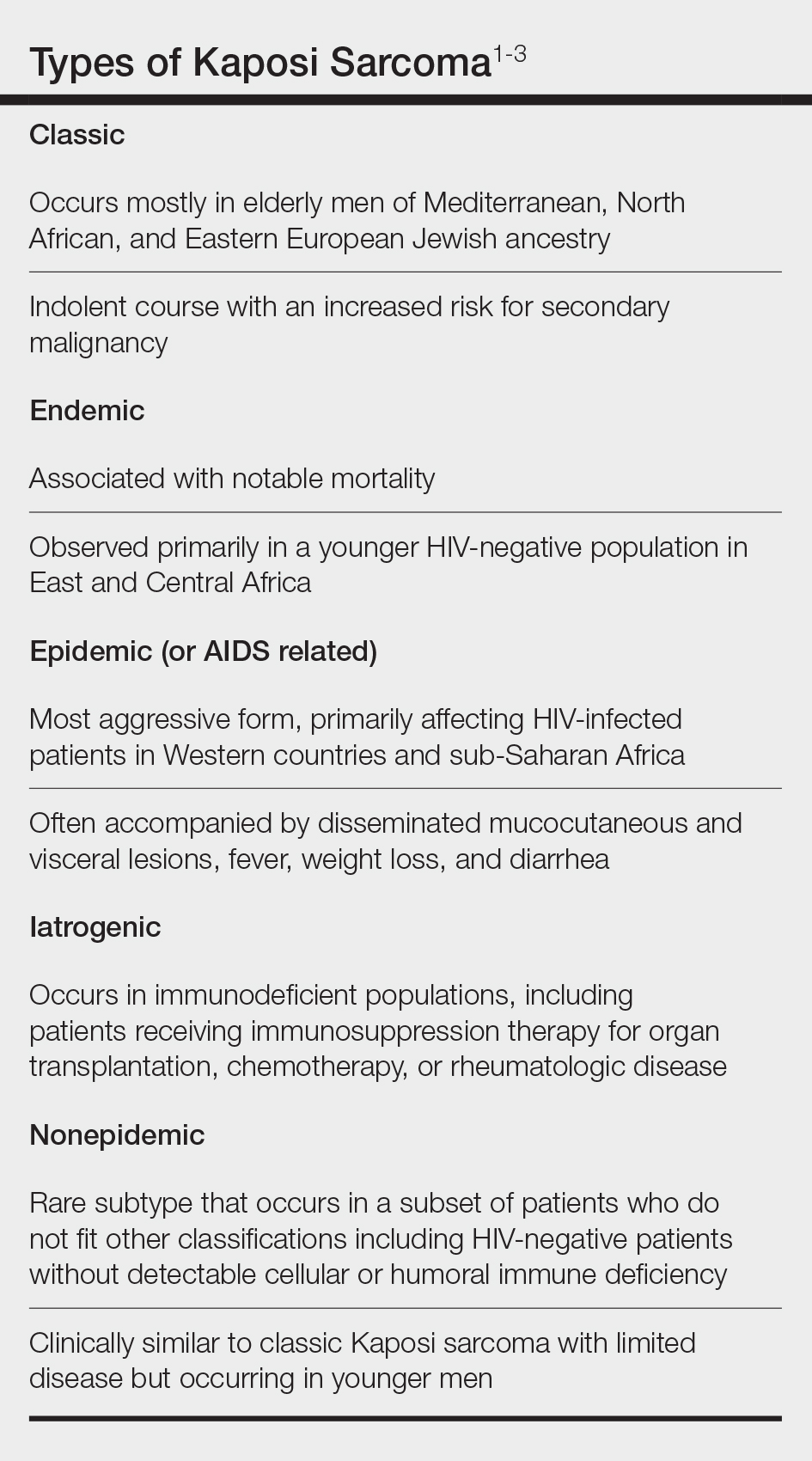

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a rare angioproliferative disorder associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection.1 There are 4 main recognized epidemiologic forms of KS: classic, endemic, epidemic, and iatrogenic (Table). Nonepidemic KS is a recently described rare fifth type of KS that occurs in a subset of patients who do not fit the other classifications—HIV-negative patients without detectable cellular or humoral immune deficiency. This subset has been described as clinically similar to classic KS with limited disease but occurring in younger men.2,3 We describe a case of nonepidemic KS in a Middle Eastern heterosexual immunocompetent man.

A 30-year-old man presented for evaluation of a growth on the nose of 3 months’ duration. The patient reported being otherwise healthy and was not taking long-term medications. He denied a history of malignancy, organ transplant, or immunosuppressive therapy. He was born in Syria and lived in Thailand for several years prior to moving to the United States. HIV testing 6 months prior to presentation was negative. He denied fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, hemoptysis, melena, hematochezia, and intravenous drug use.

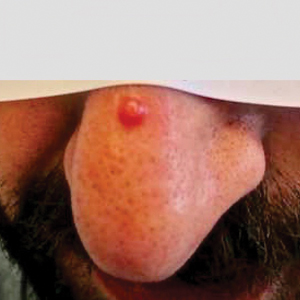

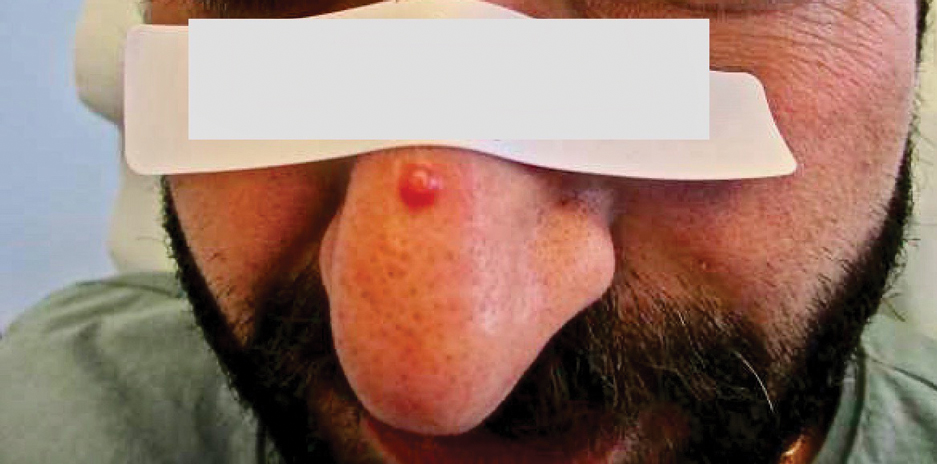

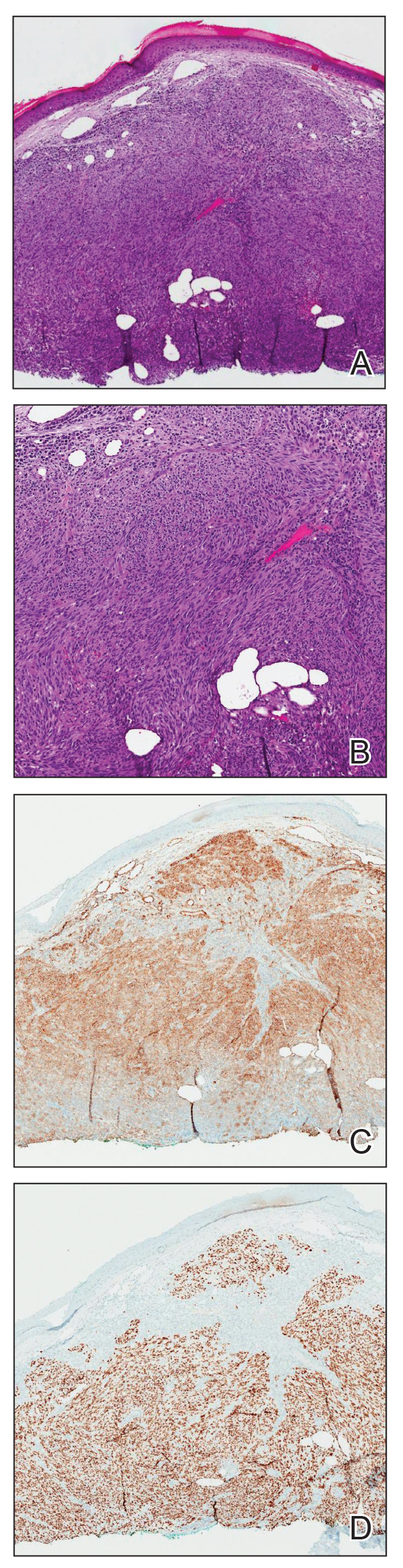

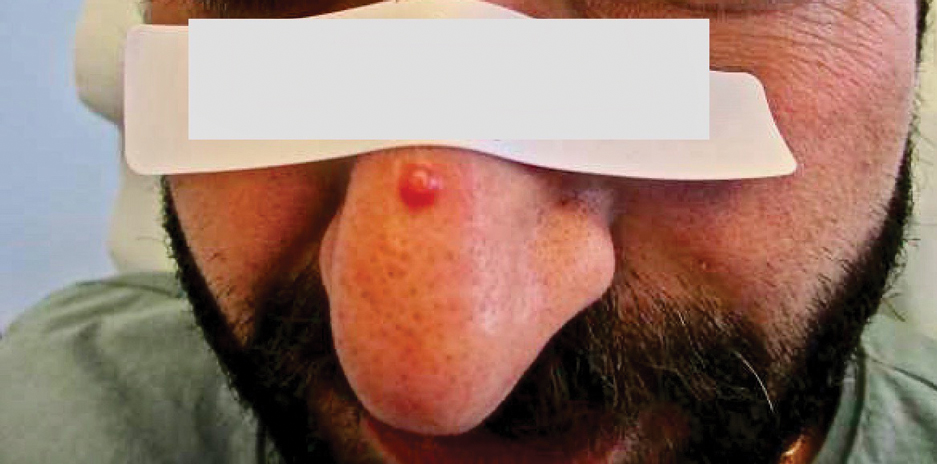

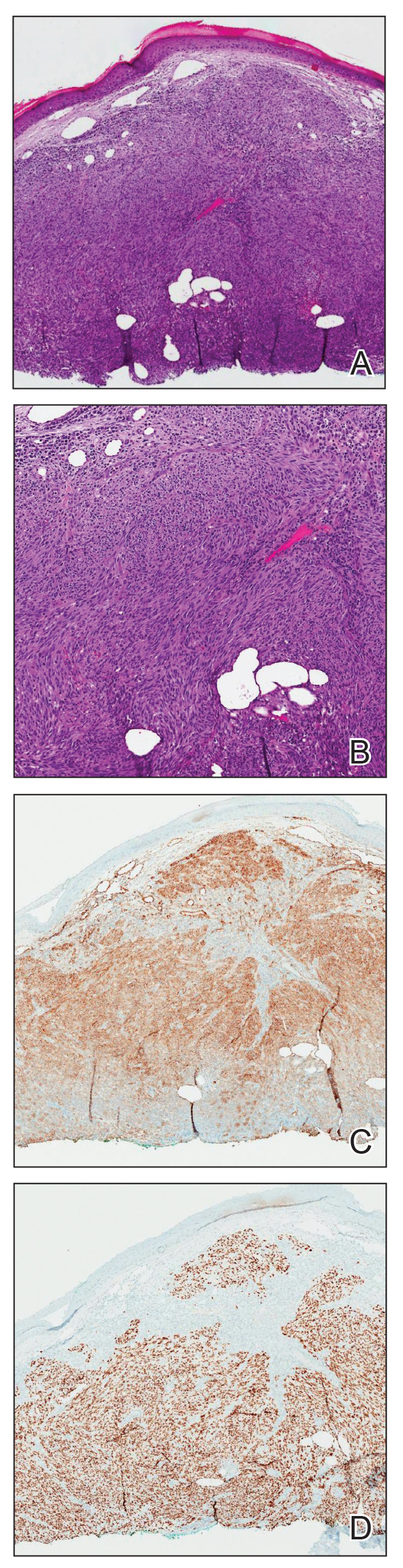

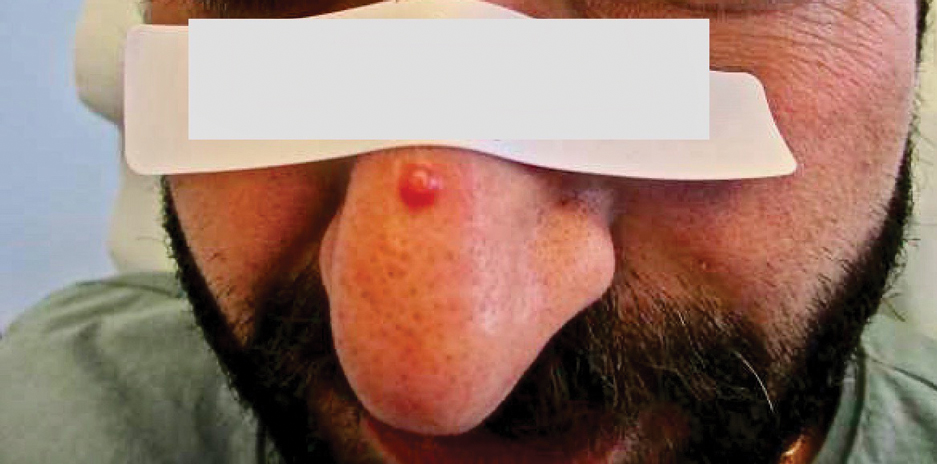

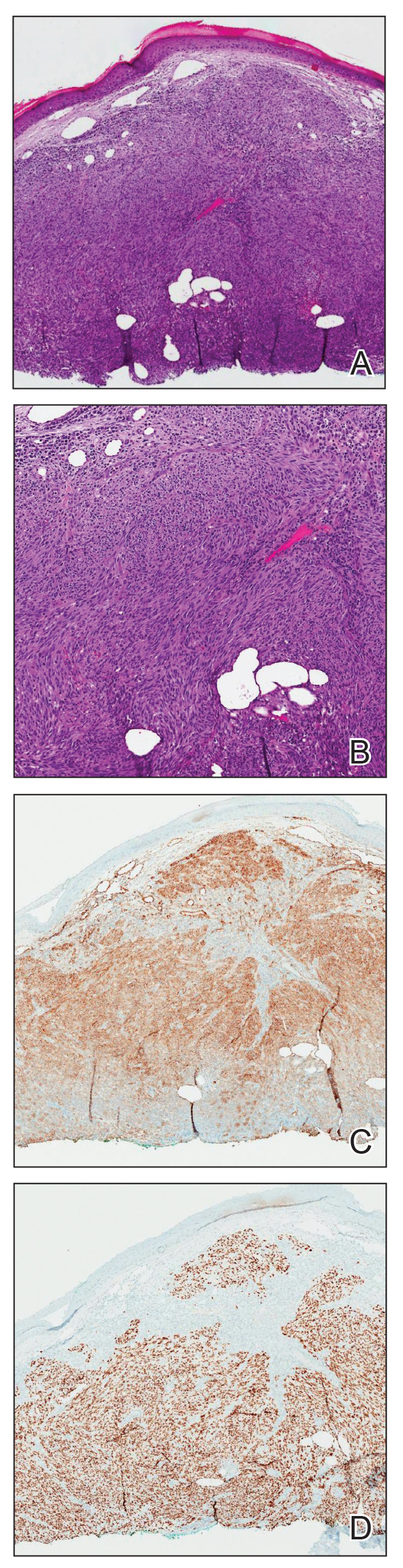

Physical examination revealed a solitary shiny, 7-mm, pink-red papule on the nasal dorsum (Figure 1). No other skin or mucosal lesions were identified. There was no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy. A laboratory workup consisting of serum immunoglobulins and serum protein electrophoresis was unremarkable. Tests for HIV-1 and HIV-2 as well as human T-lymphotropic virus 1 and 2 were negative. The CD4 and CD8 counts were within reference range. Histopathology of a shave biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation arranged in short intersecting fascicles and admixed with plasma cells and occasional mitotic figures. Immunohistochemistry showed that the spindle cells stained positive for CD34, CD31, and HHV-8 (Figure 2). The lesion resolved after treatment with cryotherapy. Repeat HIV testing 3 months later was negative. No recurrence or new lesions were identified at 3-month follow-up.

Similar to the other subtypes of KS, the nonepidemic form is dependent on HHV-8 infection, which is more commonly transmitted via saliva and sexual contact.3,4 After infecting endothelial cells, HHV-8 is believed to activate the mammalian target of rapamycin and nuclear factor κB pathways, resulting in aberrant cellular differentiation and neoangiogenesis through upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.2,4 Similar to what is seen with other herpesviruses, HHV-8 infection typically is lifelong due to the virus’s ability to establish latency within human B cells and endothelial cells as well as undergo sporadic bouts of lytic reactivation during its life cycle.4

Nonepidemic KS resembles other variants clinically, manifesting as erythematous or violaceous, painless, nonblanchable macules, papules, and nodules.1 Early lesions often are asymptomatic and can manifest as pigmented macules or small papules that vary from pale pink to vivid purple. Nodules also can occur and be exophytic and ulcerated with bleeding.1 Secondary lymphoproliferative disorders including Castleman disease and lymphoma have been reported.2,5

In contrast to other types of KS in which pulmonary or gastrointestinal tract lesions can develop with hemoptysis or hematochezia, mucocutaneous and visceral lesions rarely are reported in nonepidemic KS.3 Lymphedema, a feature associated with endemic KS, is notably absent in nonepidemic KS.1,3

The differential diagnosis applicable to all KS subtypes includes other vascular lesions such as angiomatosis and angiosarcoma. Histopathologic analysis is critical to differentiate KS from these conditions; visual diagnosis alone has only an 80% positive predictive value for KS.4 The histopathologic presentation of KS is a vascular proliferation in the dermis accompanied by an increased number of vessels without an endothelial cell lining.4 Spindle cell proliferation also is a common feature and is considered to be the KS tumor cell. Immunostaining for HHV-8 antigen as well as for CD31 and CD34 can be used to confirm the diagnosis.4

The management and prognosis of KS depends on the epidemiologic subtype. Classic and nonepidemic KS generally are indolent with a good prognosis. Periodic follow-up is recommended because of an increased risk for secondary malignancy such as lymphoma. The treatment of epidemic KS is highly active antiretroviral therapy. Similarly, reduction of immunosuppression is warranted for iatrogenic KS. For all types, cutaneous lesions can be treated with local excision, cryosurgery, radiation, chemotherapy, intralesional vincristine, or a topical agent such as imiquimod or alitretinoin.6

- Hinojosa T, Lewis DJ, Liu M, et al. Nonepidemic Kaposi sarcoma: a recently proposed category. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;3:441-443. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.04.012

- Heymann WR. Nonepidemic Kaposi sarcoma: the fifth dimension. Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries. Published October 16, 2019. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-insights-and-inquiries/2019-archive/october/nonepidemic-kaposi-sarcoma

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14080

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:9. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- Vecerek N, Truong A, Turner R, et al. Nonepidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma: an underrecognized subtype in HIV-negative patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(suppl 1):AB247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.1096

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0270-4

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a rare angioproliferative disorder associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection.1 There are 4 main recognized epidemiologic forms of KS: classic, endemic, epidemic, and iatrogenic (Table). Nonepidemic KS is a recently described rare fifth type of KS that occurs in a subset of patients who do not fit the other classifications—HIV-negative patients without detectable cellular or humoral immune deficiency. This subset has been described as clinically similar to classic KS with limited disease but occurring in younger men.2,3 We describe a case of nonepidemic KS in a Middle Eastern heterosexual immunocompetent man.

A 30-year-old man presented for evaluation of a growth on the nose of 3 months’ duration. The patient reported being otherwise healthy and was not taking long-term medications. He denied a history of malignancy, organ transplant, or immunosuppressive therapy. He was born in Syria and lived in Thailand for several years prior to moving to the United States. HIV testing 6 months prior to presentation was negative. He denied fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, hemoptysis, melena, hematochezia, and intravenous drug use.

Physical examination revealed a solitary shiny, 7-mm, pink-red papule on the nasal dorsum (Figure 1). No other skin or mucosal lesions were identified. There was no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy. A laboratory workup consisting of serum immunoglobulins and serum protein electrophoresis was unremarkable. Tests for HIV-1 and HIV-2 as well as human T-lymphotropic virus 1 and 2 were negative. The CD4 and CD8 counts were within reference range. Histopathology of a shave biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation arranged in short intersecting fascicles and admixed with plasma cells and occasional mitotic figures. Immunohistochemistry showed that the spindle cells stained positive for CD34, CD31, and HHV-8 (Figure 2). The lesion resolved after treatment with cryotherapy. Repeat HIV testing 3 months later was negative. No recurrence or new lesions were identified at 3-month follow-up.

Similar to the other subtypes of KS, the nonepidemic form is dependent on HHV-8 infection, which is more commonly transmitted via saliva and sexual contact.3,4 After infecting endothelial cells, HHV-8 is believed to activate the mammalian target of rapamycin and nuclear factor κB pathways, resulting in aberrant cellular differentiation and neoangiogenesis through upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.2,4 Similar to what is seen with other herpesviruses, HHV-8 infection typically is lifelong due to the virus’s ability to establish latency within human B cells and endothelial cells as well as undergo sporadic bouts of lytic reactivation during its life cycle.4

Nonepidemic KS resembles other variants clinically, manifesting as erythematous or violaceous, painless, nonblanchable macules, papules, and nodules.1 Early lesions often are asymptomatic and can manifest as pigmented macules or small papules that vary from pale pink to vivid purple. Nodules also can occur and be exophytic and ulcerated with bleeding.1 Secondary lymphoproliferative disorders including Castleman disease and lymphoma have been reported.2,5

In contrast to other types of KS in which pulmonary or gastrointestinal tract lesions can develop with hemoptysis or hematochezia, mucocutaneous and visceral lesions rarely are reported in nonepidemic KS.3 Lymphedema, a feature associated with endemic KS, is notably absent in nonepidemic KS.1,3

The differential diagnosis applicable to all KS subtypes includes other vascular lesions such as angiomatosis and angiosarcoma. Histopathologic analysis is critical to differentiate KS from these conditions; visual diagnosis alone has only an 80% positive predictive value for KS.4 The histopathologic presentation of KS is a vascular proliferation in the dermis accompanied by an increased number of vessels without an endothelial cell lining.4 Spindle cell proliferation also is a common feature and is considered to be the KS tumor cell. Immunostaining for HHV-8 antigen as well as for CD31 and CD34 can be used to confirm the diagnosis.4

The management and prognosis of KS depends on the epidemiologic subtype. Classic and nonepidemic KS generally are indolent with a good prognosis. Periodic follow-up is recommended because of an increased risk for secondary malignancy such as lymphoma. The treatment of epidemic KS is highly active antiretroviral therapy. Similarly, reduction of immunosuppression is warranted for iatrogenic KS. For all types, cutaneous lesions can be treated with local excision, cryosurgery, radiation, chemotherapy, intralesional vincristine, or a topical agent such as imiquimod or alitretinoin.6

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a rare angioproliferative disorder associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection.1 There are 4 main recognized epidemiologic forms of KS: classic, endemic, epidemic, and iatrogenic (Table). Nonepidemic KS is a recently described rare fifth type of KS that occurs in a subset of patients who do not fit the other classifications—HIV-negative patients without detectable cellular or humoral immune deficiency. This subset has been described as clinically similar to classic KS with limited disease but occurring in younger men.2,3 We describe a case of nonepidemic KS in a Middle Eastern heterosexual immunocompetent man.

A 30-year-old man presented for evaluation of a growth on the nose of 3 months’ duration. The patient reported being otherwise healthy and was not taking long-term medications. He denied a history of malignancy, organ transplant, or immunosuppressive therapy. He was born in Syria and lived in Thailand for several years prior to moving to the United States. HIV testing 6 months prior to presentation was negative. He denied fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, shortness of breath, hemoptysis, melena, hematochezia, and intravenous drug use.

Physical examination revealed a solitary shiny, 7-mm, pink-red papule on the nasal dorsum (Figure 1). No other skin or mucosal lesions were identified. There was no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy. A laboratory workup consisting of serum immunoglobulins and serum protein electrophoresis was unremarkable. Tests for HIV-1 and HIV-2 as well as human T-lymphotropic virus 1 and 2 were negative. The CD4 and CD8 counts were within reference range. Histopathology of a shave biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation arranged in short intersecting fascicles and admixed with plasma cells and occasional mitotic figures. Immunohistochemistry showed that the spindle cells stained positive for CD34, CD31, and HHV-8 (Figure 2). The lesion resolved after treatment with cryotherapy. Repeat HIV testing 3 months later was negative. No recurrence or new lesions were identified at 3-month follow-up.

Similar to the other subtypes of KS, the nonepidemic form is dependent on HHV-8 infection, which is more commonly transmitted via saliva and sexual contact.3,4 After infecting endothelial cells, HHV-8 is believed to activate the mammalian target of rapamycin and nuclear factor κB pathways, resulting in aberrant cellular differentiation and neoangiogenesis through upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.2,4 Similar to what is seen with other herpesviruses, HHV-8 infection typically is lifelong due to the virus’s ability to establish latency within human B cells and endothelial cells as well as undergo sporadic bouts of lytic reactivation during its life cycle.4

Nonepidemic KS resembles other variants clinically, manifesting as erythematous or violaceous, painless, nonblanchable macules, papules, and nodules.1 Early lesions often are asymptomatic and can manifest as pigmented macules or small papules that vary from pale pink to vivid purple. Nodules also can occur and be exophytic and ulcerated with bleeding.1 Secondary lymphoproliferative disorders including Castleman disease and lymphoma have been reported.2,5

In contrast to other types of KS in which pulmonary or gastrointestinal tract lesions can develop with hemoptysis or hematochezia, mucocutaneous and visceral lesions rarely are reported in nonepidemic KS.3 Lymphedema, a feature associated with endemic KS, is notably absent in nonepidemic KS.1,3

The differential diagnosis applicable to all KS subtypes includes other vascular lesions such as angiomatosis and angiosarcoma. Histopathologic analysis is critical to differentiate KS from these conditions; visual diagnosis alone has only an 80% positive predictive value for KS.4 The histopathologic presentation of KS is a vascular proliferation in the dermis accompanied by an increased number of vessels without an endothelial cell lining.4 Spindle cell proliferation also is a common feature and is considered to be the KS tumor cell. Immunostaining for HHV-8 antigen as well as for CD31 and CD34 can be used to confirm the diagnosis.4

The management and prognosis of KS depends on the epidemiologic subtype. Classic and nonepidemic KS generally are indolent with a good prognosis. Periodic follow-up is recommended because of an increased risk for secondary malignancy such as lymphoma. The treatment of epidemic KS is highly active antiretroviral therapy. Similarly, reduction of immunosuppression is warranted for iatrogenic KS. For all types, cutaneous lesions can be treated with local excision, cryosurgery, radiation, chemotherapy, intralesional vincristine, or a topical agent such as imiquimod or alitretinoin.6

- Hinojosa T, Lewis DJ, Liu M, et al. Nonepidemic Kaposi sarcoma: a recently proposed category. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;3:441-443. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.04.012

- Heymann WR. Nonepidemic Kaposi sarcoma: the fifth dimension. Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries. Published October 16, 2019. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-insights-and-inquiries/2019-archive/october/nonepidemic-kaposi-sarcoma

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14080

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:9. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- Vecerek N, Truong A, Turner R, et al. Nonepidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma: an underrecognized subtype in HIV-negative patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(suppl 1):AB247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.1096

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0270-4

- Hinojosa T, Lewis DJ, Liu M, et al. Nonepidemic Kaposi sarcoma: a recently proposed category. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;3:441-443. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.04.012

- Heymann WR. Nonepidemic Kaposi sarcoma: the fifth dimension. Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries. Published October 16, 2019. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-insights-and-inquiries/2019-archive/october/nonepidemic-kaposi-sarcoma

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14080

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:9. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- Vecerek N, Truong A, Turner R, et al. Nonepidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma: an underrecognized subtype in HIV-negative patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(suppl 1):AB247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.1096

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0270-4

Practice Points

- Nonepidemic Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a recently described fifth subtype of the disease that typically occurs in younger men who are HIV-negative without detectable cellular or humoral immune deficiency.

- The cutaneous manifestations of nonepidemic KS are similar to those of classic KS, except that disease extent is limited and the prognosis is favorable in nonepidemic KS.

- Dermatologists should consider KS when a patient presents with clinically representative findings, even in the absence of typical risk factors such as immunosuppression.

Painful Retiform Purpura in a Peritoneal Dialysis Patient

The Diagnosis: Calcific Uremic Arteriolopathy

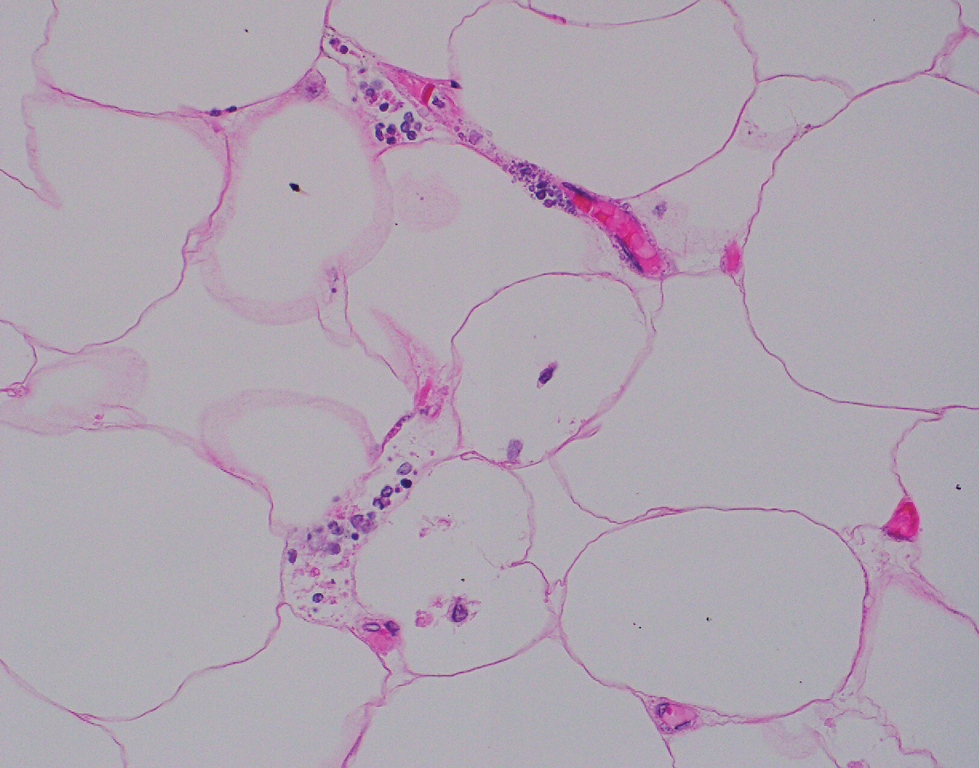

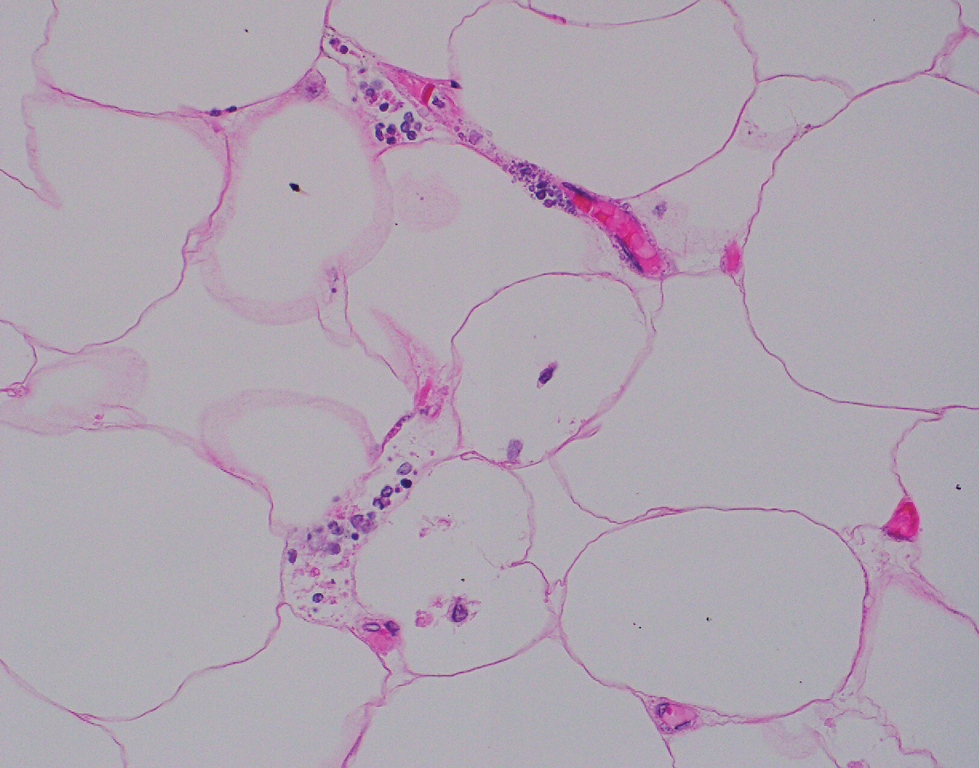

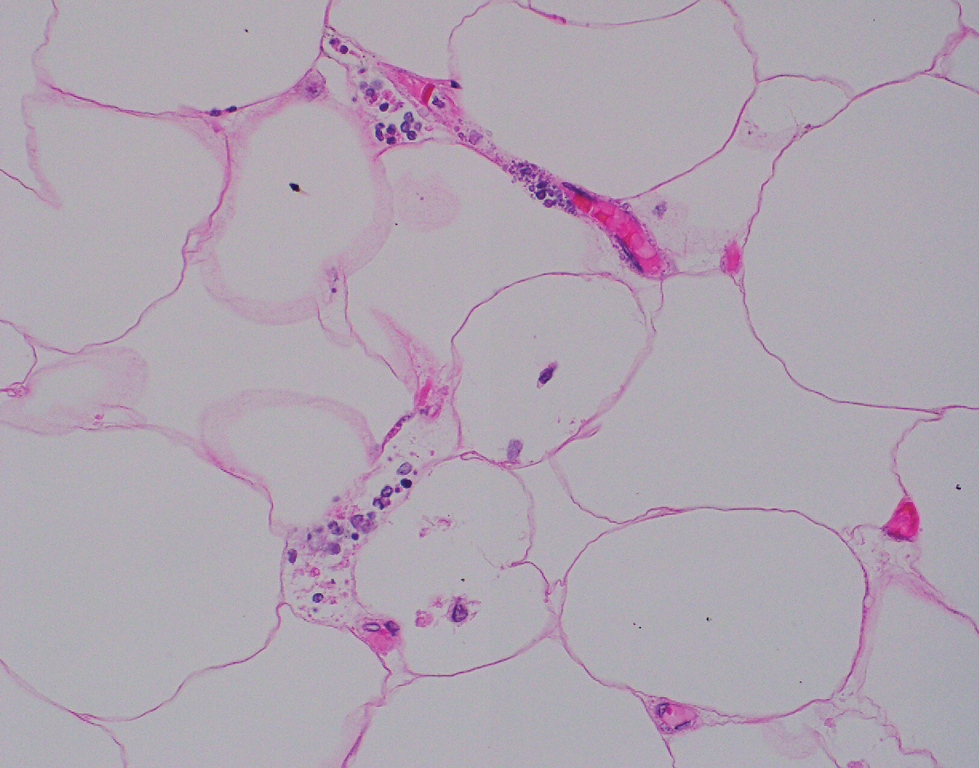

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a right complex renal cyst with peripheral calcification; computed tomography of the head without contrast revealed atherosclerotic changes with calcification of the intracranial arteries, vertebral basilar arteries, and bilateral branches of the ophthalmic artery. Histopathology revealed occlusive vasculopathy with epidermal ischemic changes as well as dermal and subcutaneous vascular congestion and small thrombi. Within the subcutis, there were tiny stippled calcium deposits within very small vascular lumina (Figure). The combination of clinical and histological findings was highly suggestive of calcific uremic arteriolopathy, and the patient was transitioned to hemodialysis against a low-calcium bath to avoid hypercalcemia. Unfortunately, she developed complications related to sepsis and experienced worsening mentation. After a discussion with palliative care, the patient was transitioned to comfort measures and discharged home on hospice 1 week after the biopsy at her family’s request.

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (also known as calciphylaxis) is a rare, life-threatening syndrome of widespread vascular calcification leading to microvascular occlusion within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1 Clinically, it typically manifests as severely painful, purpuric skin lesions that evolve through phases of blistering, ulceration, and ultimately visible skin necrosis.2 The pain likely is a consequence of ischemia and nociceptive activation and often may precede any visibly apparent skin lesions.3 Risk factors associated with the development of this condition include female sex; history of diabetes mellitus, obesity, rapid weight loss, or end-stage renal disease; abnormalities in calcium and phosphorus homeostasis; and vitamin K deficiency.1,3 It is more prevalent in patients on peritoneal dialysis compared to hemodialysis.4

Calciphylaxis is diagnosed with combined clinical and histopathological evidence. Laboratory test abnormalities are not specific for disease; therefore, skin biopsy is the standard confirmatory test, though its practice is contentious due to the risk for nonhealing ulceration and increasing risk for infection.1 Findings suggestive of disease include focal to diffuse calcification (intravascular, extravascular, or perieccrine), superficial fat calcium deposition, mid panniculus calcium deposition, mid panniculus vascular thrombi, and focal to diffuse angioplasia.5 The hallmark feature is diffuse calcification of small capillaries in adipose tissue.6

The mortality rate associated with this disease is high—a 6-month mortality rate of 27% to 43% has been reported from the time of diagnosis7-9—which often is related to subsequent superimposed infections patients acquire from necrotic skin tissue.2 The disease also carries high morbidity, with patients experiencing frequent hospitalizations related to pain, infections, and nonhealing wounds.6 There is no standard treatment, and trials have been limited to small sample sizes. A multidisciplinary treatment approach is essential to maximize outcomes, which includes wound care, risk factor modification, analgesia, and symptomatic management strategies.1,2,6

Some pharmacologic agents have received noteworthy attention in treating calciphylaxis, including sodium thiosulfate (STS), bisphosphonates, and vitamin K supplementation.1 The strongest evidence supporting the use of STS comes from 2 trials involving 53 and 27 dialysis patients, with complete remission in 14 (26%) and 14 (52%) patients, respectively.10,11 However, these trials did not include control groups to compare outcomes, and mortality rates were similarly high among partial responders and nonresponders compared with patients not treated with STS. A 2018 systematic review failed to assess the efficacy of STS alone for the treatment of calciphylaxis but suggested there may be a future role for it, with 251 of 358 patients (70.1%) responding to therapy.12

Erythema ab igne is a cutaneous reaction related to long-term heat exposure, often from electronic devices such as laptops, heating pads, space heaters, or hot-water bottles.13,14 Clinically, this rash appears as an erythematous, purpuric, or hyperpigmented reticular dermatosis that is below the clinical threshold to define a thermal burn.13 Lesions often are seen on the anterior thighs or across the abdomen.15 There usually are no long-term clinical sequelae; however, rare malignant transformation has been documented in cases of atrophy or nonhealing ulceration.16 Treatment is supportive with removal of the offending agent, but hyperpigmentation may persist for months to years.14

Livedo reticularis is a cutaneous pattern of mottled violaceous or hyperpigmented changes that often signifies underlying vascular dermal changes.17 It can be seen in various pathologic states, including vasculitis, autoimmune disease, connective tissue disease, neurologic disease, infection, or malignancy, or it can be drug induced.18 There are no pathognomonic microscopic changes, as the histology will drastically differ based on the etiology. Workup can be extensive; cues to the underlying pathology should be sought based on the patient’s history and concurrent presenting symptoms. Livedo reticularis is the most common dermatologic finding in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome, and workup should include antiphospholipid antibodies (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, anti–beta-2-glycoproteins) as well as lupus testing (eg, antinuclear antibodies, anti– double-stranded DNA).19 Treatment is targeted at the underlying disease process.

Cryoglobulinemia is a disease characterized by abnormal serum immunoglobulins that precipitate at cold temperatures and is further subcategorized by the type of complexes that are deposited.20 Type I represents purely monoclonal cryoglobulins, type III purely polyclonal, and type II a mixed picture. Clinical manifestations arise from excessive deposition of these proteins in the skin, joints, peripheral vasculature, and kidneys leading to purpuric skin lesions, chronic ulceration, arthralgia, and glomerulonephritis. Cutaneous findings may include erythematous to purpuric macular or papular changes with or without the presence of ulceration, infarction, or hemorrhagic crusting.21 Systemic disease often underlies a diagnosis, and further investigation for hepatitis C virus, connective tissue disease, and hematologic malignancies should be considered.20 Treatment is targeted at underlying systemic disease, such as antiviral treatment for hepatitis or chemotherapeutic regimens for hematologic disease.22

Polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic necrotizing vasculitis that typically involves small- to medium-sized arteries. Cutaneous manifestations often include subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, and ulcerations most found on the lower extremities.23 Systemic symptoms including fever, myalgia, arthralgia, and neuropathy often are present. Characteristic histopathology findings include inflammation and destruction of medium-sized arteries at the junctional zone of the dermis and subcutis along with microaneurysms along the vessels.24 Treatment is based on the severity of disease, with localized cutaneous disease often being controlled with topical steroids and anti-inflammatory agents, while more widespread disease requires immunosuppression with systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, or intravenous immunoglobulins.23

- Nigwekar SU, Thadhani R, Brandenburg VM. Calciphylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1704-1714. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1505292

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

- Chang JJ. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32:205-215. doi:10.1097/01 .ASW.0000554443.14002.13

- Zhang Y, Corapi KM, Luongo M, et al. Calciphylaxis in peritoneal dialysis patients: a single center cohort study. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016;9:235-241. doi:10.2147/ijnrd.S115701

- Chen TY, Lehman JS, Gibson LE, et al. Histopathology of calciphylaxis: cohort study with clinical correlations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:795-802. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000824

- Kodumudi V, Jeha GM, Mydlo N, et al. Management of cutaneous calciphylaxis. Adv Ther. 2020;37:4797-4807. doi:10.1007 /s12325-020-01504-w

- Nigwekar SU, Zhao S, Wenger J, et al. A nationally representative study of calcific uremic arteriolopathy risk factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3421-3429. doi:10.1681/asn.2015091065

- McCarthy JT, El-Azhary RA, Patzelt MT, et al. Survival, risk factors, and effect of treatment in 101 patients with calciphylaxis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1384-1394. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.025

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00375.x

- Nigwekar SU, Brunelli SM, Meade D, et al. Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1162-1170. doi:10.2215/cjn.09880912

- Zitt E, König M, Vychytil A, et al. Use of sodium thiosulphate in a multi-interventional setting for the treatment of calciphylaxis in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1232-1240. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfs548

- Peng T, Zhuo L, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of sodium thiosulfate in treating calciphylaxis in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018;23:669-675. doi:10.1111/nep.13081

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Kettelhut EA, Traylor J, Sathe NC, et al. Erythema ab igne. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Knöpfel N, Weibel L. Erythema Ab Igne. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157: 106. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3995

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Rose AE, Sagger V, Boyd KP, et al. Livedo reticularis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20705.

- Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:315-321. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.164493

- Uthman IW, Khamashta MA. Livedo racemosa: a striking dermatological sign for the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2379-2382.

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Cryoglobulinemia: an update in 2019. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86:707-713. doi:10.1016/j .jbspin.2019.01.016

- Cohen SJ, Pittelkow MR, Su WP. Cutaneous manifestations of cryoglobulinemia: clinical and histopathologic study of seventy-two patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25(1, pt 1):21-27. doi:10.1016 /0190-9622(91)70168-2

- Takada S, Shimizu T, Hadano Y, et al. Cryoglobulinemia (review). Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:3-8. doi:10.3892/mmr.2012.861

- Turska M, Parada-Turska J. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. Wiad Lek. 2018;71(1, pt 1):73-77.

- De Virgilio A, Greco A, Magliulo G, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa: a contemporary overview. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:564-570. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.02.015

The Diagnosis: Calcific Uremic Arteriolopathy

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a right complex renal cyst with peripheral calcification; computed tomography of the head without contrast revealed atherosclerotic changes with calcification of the intracranial arteries, vertebral basilar arteries, and bilateral branches of the ophthalmic artery. Histopathology revealed occlusive vasculopathy with epidermal ischemic changes as well as dermal and subcutaneous vascular congestion and small thrombi. Within the subcutis, there were tiny stippled calcium deposits within very small vascular lumina (Figure). The combination of clinical and histological findings was highly suggestive of calcific uremic arteriolopathy, and the patient was transitioned to hemodialysis against a low-calcium bath to avoid hypercalcemia. Unfortunately, she developed complications related to sepsis and experienced worsening mentation. After a discussion with palliative care, the patient was transitioned to comfort measures and discharged home on hospice 1 week after the biopsy at her family’s request.

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (also known as calciphylaxis) is a rare, life-threatening syndrome of widespread vascular calcification leading to microvascular occlusion within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1 Clinically, it typically manifests as severely painful, purpuric skin lesions that evolve through phases of blistering, ulceration, and ultimately visible skin necrosis.2 The pain likely is a consequence of ischemia and nociceptive activation and often may precede any visibly apparent skin lesions.3 Risk factors associated with the development of this condition include female sex; history of diabetes mellitus, obesity, rapid weight loss, or end-stage renal disease; abnormalities in calcium and phosphorus homeostasis; and vitamin K deficiency.1,3 It is more prevalent in patients on peritoneal dialysis compared to hemodialysis.4

Calciphylaxis is diagnosed with combined clinical and histopathological evidence. Laboratory test abnormalities are not specific for disease; therefore, skin biopsy is the standard confirmatory test, though its practice is contentious due to the risk for nonhealing ulceration and increasing risk for infection.1 Findings suggestive of disease include focal to diffuse calcification (intravascular, extravascular, or perieccrine), superficial fat calcium deposition, mid panniculus calcium deposition, mid panniculus vascular thrombi, and focal to diffuse angioplasia.5 The hallmark feature is diffuse calcification of small capillaries in adipose tissue.6

The mortality rate associated with this disease is high—a 6-month mortality rate of 27% to 43% has been reported from the time of diagnosis7-9—which often is related to subsequent superimposed infections patients acquire from necrotic skin tissue.2 The disease also carries high morbidity, with patients experiencing frequent hospitalizations related to pain, infections, and nonhealing wounds.6 There is no standard treatment, and trials have been limited to small sample sizes. A multidisciplinary treatment approach is essential to maximize outcomes, which includes wound care, risk factor modification, analgesia, and symptomatic management strategies.1,2,6

Some pharmacologic agents have received noteworthy attention in treating calciphylaxis, including sodium thiosulfate (STS), bisphosphonates, and vitamin K supplementation.1 The strongest evidence supporting the use of STS comes from 2 trials involving 53 and 27 dialysis patients, with complete remission in 14 (26%) and 14 (52%) patients, respectively.10,11 However, these trials did not include control groups to compare outcomes, and mortality rates were similarly high among partial responders and nonresponders compared with patients not treated with STS. A 2018 systematic review failed to assess the efficacy of STS alone for the treatment of calciphylaxis but suggested there may be a future role for it, with 251 of 358 patients (70.1%) responding to therapy.12

Erythema ab igne is a cutaneous reaction related to long-term heat exposure, often from electronic devices such as laptops, heating pads, space heaters, or hot-water bottles.13,14 Clinically, this rash appears as an erythematous, purpuric, or hyperpigmented reticular dermatosis that is below the clinical threshold to define a thermal burn.13 Lesions often are seen on the anterior thighs or across the abdomen.15 There usually are no long-term clinical sequelae; however, rare malignant transformation has been documented in cases of atrophy or nonhealing ulceration.16 Treatment is supportive with removal of the offending agent, but hyperpigmentation may persist for months to years.14

Livedo reticularis is a cutaneous pattern of mottled violaceous or hyperpigmented changes that often signifies underlying vascular dermal changes.17 It can be seen in various pathologic states, including vasculitis, autoimmune disease, connective tissue disease, neurologic disease, infection, or malignancy, or it can be drug induced.18 There are no pathognomonic microscopic changes, as the histology will drastically differ based on the etiology. Workup can be extensive; cues to the underlying pathology should be sought based on the patient’s history and concurrent presenting symptoms. Livedo reticularis is the most common dermatologic finding in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome, and workup should include antiphospholipid antibodies (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, anti–beta-2-glycoproteins) as well as lupus testing (eg, antinuclear antibodies, anti– double-stranded DNA).19 Treatment is targeted at the underlying disease process.

Cryoglobulinemia is a disease characterized by abnormal serum immunoglobulins that precipitate at cold temperatures and is further subcategorized by the type of complexes that are deposited.20 Type I represents purely monoclonal cryoglobulins, type III purely polyclonal, and type II a mixed picture. Clinical manifestations arise from excessive deposition of these proteins in the skin, joints, peripheral vasculature, and kidneys leading to purpuric skin lesions, chronic ulceration, arthralgia, and glomerulonephritis. Cutaneous findings may include erythematous to purpuric macular or papular changes with or without the presence of ulceration, infarction, or hemorrhagic crusting.21 Systemic disease often underlies a diagnosis, and further investigation for hepatitis C virus, connective tissue disease, and hematologic malignancies should be considered.20 Treatment is targeted at underlying systemic disease, such as antiviral treatment for hepatitis or chemotherapeutic regimens for hematologic disease.22

Polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic necrotizing vasculitis that typically involves small- to medium-sized arteries. Cutaneous manifestations often include subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, and ulcerations most found on the lower extremities.23 Systemic symptoms including fever, myalgia, arthralgia, and neuropathy often are present. Characteristic histopathology findings include inflammation and destruction of medium-sized arteries at the junctional zone of the dermis and subcutis along with microaneurysms along the vessels.24 Treatment is based on the severity of disease, with localized cutaneous disease often being controlled with topical steroids and anti-inflammatory agents, while more widespread disease requires immunosuppression with systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, or intravenous immunoglobulins.23

The Diagnosis: Calcific Uremic Arteriolopathy

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a right complex renal cyst with peripheral calcification; computed tomography of the head without contrast revealed atherosclerotic changes with calcification of the intracranial arteries, vertebral basilar arteries, and bilateral branches of the ophthalmic artery. Histopathology revealed occlusive vasculopathy with epidermal ischemic changes as well as dermal and subcutaneous vascular congestion and small thrombi. Within the subcutis, there were tiny stippled calcium deposits within very small vascular lumina (Figure). The combination of clinical and histological findings was highly suggestive of calcific uremic arteriolopathy, and the patient was transitioned to hemodialysis against a low-calcium bath to avoid hypercalcemia. Unfortunately, she developed complications related to sepsis and experienced worsening mentation. After a discussion with palliative care, the patient was transitioned to comfort measures and discharged home on hospice 1 week after the biopsy at her family’s request.

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (also known as calciphylaxis) is a rare, life-threatening syndrome of widespread vascular calcification leading to microvascular occlusion within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1 Clinically, it typically manifests as severely painful, purpuric skin lesions that evolve through phases of blistering, ulceration, and ultimately visible skin necrosis.2 The pain likely is a consequence of ischemia and nociceptive activation and often may precede any visibly apparent skin lesions.3 Risk factors associated with the development of this condition include female sex; history of diabetes mellitus, obesity, rapid weight loss, or end-stage renal disease; abnormalities in calcium and phosphorus homeostasis; and vitamin K deficiency.1,3 It is more prevalent in patients on peritoneal dialysis compared to hemodialysis.4

Calciphylaxis is diagnosed with combined clinical and histopathological evidence. Laboratory test abnormalities are not specific for disease; therefore, skin biopsy is the standard confirmatory test, though its practice is contentious due to the risk for nonhealing ulceration and increasing risk for infection.1 Findings suggestive of disease include focal to diffuse calcification (intravascular, extravascular, or perieccrine), superficial fat calcium deposition, mid panniculus calcium deposition, mid panniculus vascular thrombi, and focal to diffuse angioplasia.5 The hallmark feature is diffuse calcification of small capillaries in adipose tissue.6

The mortality rate associated with this disease is high—a 6-month mortality rate of 27% to 43% has been reported from the time of diagnosis7-9—which often is related to subsequent superimposed infections patients acquire from necrotic skin tissue.2 The disease also carries high morbidity, with patients experiencing frequent hospitalizations related to pain, infections, and nonhealing wounds.6 There is no standard treatment, and trials have been limited to small sample sizes. A multidisciplinary treatment approach is essential to maximize outcomes, which includes wound care, risk factor modification, analgesia, and symptomatic management strategies.1,2,6

Some pharmacologic agents have received noteworthy attention in treating calciphylaxis, including sodium thiosulfate (STS), bisphosphonates, and vitamin K supplementation.1 The strongest evidence supporting the use of STS comes from 2 trials involving 53 and 27 dialysis patients, with complete remission in 14 (26%) and 14 (52%) patients, respectively.10,11 However, these trials did not include control groups to compare outcomes, and mortality rates were similarly high among partial responders and nonresponders compared with patients not treated with STS. A 2018 systematic review failed to assess the efficacy of STS alone for the treatment of calciphylaxis but suggested there may be a future role for it, with 251 of 358 patients (70.1%) responding to therapy.12

Erythema ab igne is a cutaneous reaction related to long-term heat exposure, often from electronic devices such as laptops, heating pads, space heaters, or hot-water bottles.13,14 Clinically, this rash appears as an erythematous, purpuric, or hyperpigmented reticular dermatosis that is below the clinical threshold to define a thermal burn.13 Lesions often are seen on the anterior thighs or across the abdomen.15 There usually are no long-term clinical sequelae; however, rare malignant transformation has been documented in cases of atrophy or nonhealing ulceration.16 Treatment is supportive with removal of the offending agent, but hyperpigmentation may persist for months to years.14